Abstract

Ecovillages aim to foster community around sustainable practices and encourage low-impact lifestyles. This article explores the strategies employed by two ecovillages to scale up their practices through physical expansion and the consequence for the maintenance of said practices. The ecovillages under study are Hurdal in Norway and Findhorn in Scotland. The study employed a multi-method approach: document study, participant observation, and interviews with ecovillage residents. The ecovillages applied different strategies to gain access to economic resources for expansion. Hurdal ecovillage sold its land to a private developer while Findhorn chose a different path: raising funds within the community, accessing public funds, and adopting low-cost building designs. The study finds that collaborating with investors and developers results in expensive housing that excludes low-income individuals and attracts well-off house buyers with mainstream values. Both ecovillages dropped introductory courses that aimed to equip new members with the necessary skills for shared practices and establish a common ground. These two consequences led to a weakening of competences for shared practices as private property took precedence. Prioritizing affordable infrastructure and accessing local (community and public) financial resources opens up paths for expansion that can maintain the necessary skills and meaning for community living.

1. Introduction

We are in a critical decade where we must change our prevailing economic system towards one with a lower impact on the environment. Local-level/community initiatives play an important role in this endeavor by promoting sustainable lifestyles. In this article, I focus on how these initiatives attempt to scale up their practices by the physical expansion of their infrastructure. I will follow Shove and colleague’s [] interpretation of social practice theory and examine the development paths of two ecovillages as case studies.

The interrelated environmental, social, and economic problems we face today are closely linked with the current neoliberal economic paradigm and its resource-intensive systems of production and consumption [,]. This paradigm perpetuates itself through resource-intensive habits and daily social practices []. Studies indicate that up to 40% of carbon emissions originate from everyday energy use and transportation habits []. Popular policy tools employed to mitigate the environmental impact of private consumption are price incentives (taxes and subsidies), information campaigns, and positive reinforcements, among others. Many of these tools have their roots in ‘cognitive centered, rational, individualist conceptualization of consumption’ [] (p. 22).

Traditionally, the consumer/individual has occupied a central place in both academic and policy endeavors to understand the drivers of private consumption. Some examples of theories with this perspective are rational choice theory in mainstream economics, bounded rationality in behavioral economics, the attitude–behavior model in environmental studies, and the theory of planned behavior in social psychology [,]. These approaches have been criticized for focusing on individualized decision-making processes and disregarding the facilitating/constraining influences of social and material structure on human behavior [,,].

More recent explorations of the drivers of private consumption and habits have emphasized the role of social structures (norms, rules, meanings) and material/technology on human behavior [,,,]. Giddens [,] is credited for shifting the focus from the individual to routinized social practices that characterize private consumption and lifestyle patterns. The lifestyle of an individual includes ‘the routines incorporated into habits of dress, eating, modes of acting and favored milieu for encountering others’ [] (p. 81). Sustainable consumption researchers have studied lifestyle domains (energy, hygiene, transport) using social practice theory to illuminate how practices in these domains are established, how they persist, and the potential for a transition to sustainability [,,,,,,].

Since it pays attention to ‘social relations, the particularities of place (culture), and the influence of technology and materiality’ [] (p. 23), social practice theory has been useful in conceptualizing the emergence/consolidation of sustainable lifestyles in local-level initiatives such as ecovillages [,,,].

The Global Ecovillage Network defines an ecovillage as ‘a rural or urban community that is consciously designed through locally owned, participatory processes in all four dimensions of sustainability (social, culture, ecology, and economy) to regenerate their social and natural environments’ []. Scholars of social innovation refer to ecovillages and other community-based initiatives as ‘niches’ where people explore ‘new ways of doing, organizing, framing, and knowing’ that leads to changing social relations and practices [] (p. 197).

Previous studies have used social practice theory to show how ecovillages reconfigure daily practices to establish new norms [] and achieve significant energy and resource savings []. In this article, I study how the two ecovillages under study—Hurdal ecovillage in Norway and Findhorn ecovillage in Scotland—attempted to scale up their practices through physical expansion and the consequences for maintaining these practices. The research question that will guide this study is: how does the choice of developing the infrastructure needed for a sustainable lifestyle promote/limit the development of the necessary competence and meaning for such a lifestyle?

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 lays out the theoretical perspectives most relevant for answering the research question above. Section 3 presents the research methods. Section 4 describes the study sites, their history, and their transformation to their present form. Section 5 presents the research findings/results. Section 6 will discuss the implication for theory and practice. Section 7 concludes the article.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

The ethos of capitalism remains unchallenged despite criticism that it is causing climate breakdown, environmental degradation, and social and economic vulnerability [,,]. Wilhite [] identifies the main features of capitalism as the quest for unlimited economic growth buttressed by individual ownership, consumerism, indebtedness, and high speed of product turnover (extraction, consumption, and disposal). The growth imperative of capitalism drives the tenets of business, private lives, and national economic plans. Financed by loans and debts, corporations and businesses are motivated to pursue unlimited growth and generate profits for shareholders, often at the expense of labor or the environment []. Similarly, private lives have become accustomed to energy-intensive comfort levels in the Western world [,,]. For example, recent research published in Nature shows how resource intensive lifestyles centered around choice, convenience, and comfort drive the global biophysical resource use [,].

This prevailing economic system leaves its imprint on values and norms and reproduces itself in everyday practices []. Wilhite [] argues that the ‘seeds of growth and accumulation’ are embedded ‘in an interlocking set of narratives, materialities, and incentives’ of many everyday practices (p. 24). These practices are further entrenched by formal codes and regulations that guide and lock lifestyles in unsustainable paths (ibid). Community-level initiatives are credited for promoting low impact lifestyles and negotiating with regulations that entrench unsustainable practices [,,]. Social practice theories are well-suited to study how this process unfolds by focusing on the materials, norms, values, and competences that constitute everyday practices.

2.1. Social Practice Theory

Scholars of social practice theory trace its origins to the philosopher Wittgenstein [] and sociologists Bourdieu and Giddens, among others [,,,]. Hal Wilhite [] discusses the contributions of scholars such as Thomas Veblen, James Dewey, William James, Marcel Mauss, and Pierre Bourdieu in applying the lens of ‘habits’ to theorize about social practices and patterns. Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory [,] is credited for overcoming the so-called agent–structure dilemma in sociology by shifting the focus to the interaction between the two through the enactment of social practices []. This approach negates individual-focused approaches that put sole emphasis on the agent and his/her decision-making processes. It defies the belief that sustainable practices are solely the result of ‘green beliefs’, commitments, and individuals’ actions [] (p. 395).

Earlier formulations of practice theory emphasized the role of habits, (tacit and discursive) knowledge, rules, routines, and paid less attention to material foundations of practices []. More recently, the impact of materials in shaping and reinforcing resource-intensive routines and practices have gained ground [,,]. In this latter approach, lifestyles consist of ‘inconspicuous’ routines, habits, and practices that people take to be normal and are intimately bound up with the material and technological infrastructures of modern life [] (p. 395). The physical structures and technologies of everyday life, coupled with the social significance of our actions, entrench the patterns of daily life. Consequently, practice theories have been useful in explaining path dependencies of consumption practices [,,].

Due to its robustness, social practice theory has found applications in diverse fields (such as social theory, discourse theory, and theory of science) []. This has led to many interpretations and operationalizations of the theory and no unified theoretical approach [,]. For example, some scholars have followed Bourdieu’s work and emphasized ‘habitus’ (that is, knowledge, experience, perceptions, expressions, and actions) and embodied knowledge (body and mind interactions), in elucidating the processes that result in entrenched practices [,]. Others have emphasized the role of infrastructures, norms, and resources as constitutive elements of practices [,,]. Despite the emphasis scholars put on different constitutive elements of practices, what unifies the different approaches is their analytical focus on the elements’ interconnection and co-evolution.

Practice is broadly defined as ‘a routinized type of behavior which consists of several elements, interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion, and motivational knowledge’ [] (p. 249). In this article, I will follow Shove and colleague’s [] interpretation of social practice theory to address the research question raised in Section 1. Shove et al. [] present three elements of a social practice that help sustain it as an entity and a performance over space and time: materials, competences, and meanings. Materials include ‘technologies, tangible physical entities and the stuff of which objects are made’, competences include ‘skill, know-how, and technique’, and meanings include ‘symbolic meanings, ideas, and aspirations’ [] (p. 14). They make the case that practices emerge, persist, and disappear as connections between these elements are made, sustained, and broken, respectively (ibid).

The co-evolution of elements of practices leads to the reinvention of old practices and the diffusion of new ones []. Shove et al. [] describe how elements of a practice travel across time and space. The practices themselves, however, do not travel and are ‘localized’ and adapted to the new site of enactment with its agents, institutions, culture, and norm (p. 39). Materials can most often be transported across space and time. Competences depend on past experiences and typically migrate between space and time primarily through practitioners (individuals). Meanings spread more easily as they do not require past experience or prior knowledge.

Practices do not usually change in isolation; they often co-evolve with other practices. Practices can either compete or collaborate with each other. When they compete for the same elements (materials, meanings and competence), some practices may displace others. However, when elements collaborate, that is, when they effectively draw on similar materials, meanings, and competence, they form connections and turn into what social practice theorists call bundles []. When such connections become stronger, and practices depend and draw on each other, they form complexes (ibid). Once the connections between practices strengthen, these practices become dominant and form the patterns of everyday life.

Communities and networks play an important role in developing and propagating new practices or limiting their diffusion. New and sustainable practices are more easily adapted if they are part of a practice shared with others []. For example, in their study of transportation practices in two neighborhoods in Edmonton, Canada, Kennedy, Krahn and Krogman [] show that sustainable transport practices (such as cycling, walking, and using public transportation) are easily adopted in neighborhoods where such practices are prevalent and where the physical infrastructure is adapted for these practices. However, when people move to areas where unsustainable value systems are prevalent, mainstream norms of transportation (the use of private cars) take precedence.

Access to resources may either limit or encourage participation in sustainable practices. This could be access to the materialities, competence, and meaning of a practice for it to take root in a new place or among a new social group. The design of homes, neighborhoods, cities, and regions can engender or discourage sustainable practices [,,,]. Housing is one important materiality that entrenches the unsustainable lifestyles that are prevalent in modern societies. Wilhite [] asserts that the growth in house sizes and the associated emergence of energy and material intensive practices related to the modern house exemplifies how the habits and practices of capitalistic lifestyles have entered everyday life. House sizes have increased in both absolute and per capita terms across all OECD countries over the past decades. While family sizes have declined (40–50% of dwellings had only one person living in them in 2010 []), the idea of sharing house space with extended family members or others has practically disappeared, leading to the increase in absolute and per capita use of energy for heating and housekeeping activities [].

The marketization of house provision has led to the consideration of housing as a ‘reliable financial investment’ [] (p. 126). It changed ‘the status of housing from being regarded as an engine for social improvement to being a consumer good like any other’ [] (p. 128). Consequently, housing and land prices have increased significantly in many urban areas, making these areas inaccessible for people with lower incomes. Investing in vacation homes has also become more popular []. Sheard [] shows how vacation homes are often located in peripheral areas with lower standards of living and result in negative consequences for the local population by raising the cost of local housing and hurting the local labor and product markets. His study also shows that policy responses such as requiring homeowners to reside in these houses have dampened some of the negative impacts.

2.2. Ecovillages as ‘Communities of Practice’

Communities of practice are ‘groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise. …People in communities of practice share their experiences and knowledge in free-flowing, creative ways that foster new approaches to problems’ [] (p. 139). Communities of practice foster ‘social learning’ by providing environments where people can engage in, learn, and reproduce new practices and skills [].

Ecovillages are inspired by diverse and at times overlapping movements such as intentional communities in the global North, the Kibbutz movement in Israel, the hippie and commune movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the feminist and eco-feminist movements, and green movements among others [,]. There is no universally agreed-upon definition of ecovillages []. One of the pioneers of the Global Ecovillage Network, Robert Gilman [] (p. 10) characterizes ecovillages as ‘full-featured settlement[s] in which human activities are harmlessly integrated into the natural world in a way that is supportive of healthy human development and can be successfully continued into the indefinite future’.

Ecovillages are perceived as grassroots innovations and communities of practice for sustainable living [,,]. They encourage ways of living that go against the typical capitalistic lifestyle by promoting sharing economies and slower lifestyles where the emphasis is on strengthening social networks and lowering environmental footprint [,,,,,]. Many aim to be economically self-sufficient and experiment with forms of self-governance [,,]. These alternative practices can be seen as a paradigm shift from the mainstream, bringing about a change in ways of thinking and acting.

There are a few studies that have documented how sustainable collective practices emerge and become established in ecovillages. Roysen and Mertens [] studied how new sustainable practices emerged and became normalized in an ecovillage in Brazil. They focused on two social practice complexes: ‘community care’ (which involves maintaining common spaces in the community, cooking shared meals, composting waste…etc.) and car sharing [] (p. 3). They showed how ecovillagers developed meanings, acquired competences, and put together materials that would help them reproduce and normalize these practices. In this process, they also generate new ideas for other innovative social practices that reduce their environmental impact and help improve their local economy.

Boyer [] followed a similar path and used social practice theory to study how residents in Dancing Rabbit ecovillage (in Missouri, USA) significantly lowered their environmental impact to less than 10% of the average American citizen. They achieved this by ‘transitioning away from the exclusive ownership of capital goods, investing in skills that facilitate the collective management of resources and eliminating waste by taking advantage of locally available resources’ [] (p. 1). They eschewed the exclusive (individual) ownership of motorized vehicles, the use of fossil fuels for purposes such as powering vehicles, heating and cooling of physical spaces, and required the exclusive use of renewable energy on their premises among others. He found that their investment in social competence (of interpersonal communication and conflict–resolution skills) contributed to their success in lowering material and energy consumption.

Pickerill [] emphasizes the important role of the buildings of an ecovillage. Ecovillage buildings often symbolize an ecovillage’s aims, principles, and doctrine. They structure its functions and practices and set opportunities or constraints for the type of activities that can be performed in the ecovillage. Scholars that have studied eco-buildings in ecovillages and eco-communities raise their concern that property prices are increasing in these communities as the ideal of a close-knit, rural life close to nature enters the mainstream [,]. Similarly, Mason [] takes issue with the heavy emphasis eco-communities put on environmental sustainability at the expense of social justice. Barring these criticisms, scholars call for more research on the impact of ecovillage buildings and infrastructure on sustainable practices [,,].

This article will aim to contribute to this research gap by focusing on the endeavors of two ecovillages to build new houses and infrastructure and scale up their practices. I will pay attention to the effect this has on the (elements of) sustainable social practices. The analysis will be at the level of complexes of social practices, as opposed to individual practices.

3. Research Methods

Data Collection and Research Methods

Data for the study were gathered from the two ecovillages through participant observation, document study, and interviews with ecovillage residents. In Findhorn ecovillage, Scotland, I participated in an ‘experience week’ program that the ecovillage runs as a deep dive into ecovillage living in March/April 2019. The experience week was led by two long-term residents of the ecovillage. This program is mandatory for all that want to settle in the ecovillage and recommended for researchers that want to study the ecovillage. During this week, participants take part in workshops/group activities, visit and chat with pioneer ecovillage members in their homes, tour the ecovillage’s projects and volunteer in one of three work departments: the common kitchens, the community gardens, or community care activities. In the evenings, participants take part in group activities that the ecovillage uses to facilitate communication and community building among its members. I volunteered in the common kitchen at Cluny Hill College—a 19th century building that houses about 40 community members.

I kept detailed notes during this week of participant observation. In the evenings or when we had breaks from the organized activities, I used the opportunity to talk to residents, volunteers, and employees about their experiences of living in the ecovillage. Volunteering in the community kitchen also provided ample opportunity to talk to different community members whom I was assisting on a daily basis. Volunteers in the kitchens worked under two community members that gave them tasks. These community members rotate on a daily basis. Therefore, I got the opportunity to meet and work with different community members in the kitchen during the experience week. Meal- and tea-breaks afforded an opportunity to mingle with the wider community and learn about the challenges and opportunities of living in an intentional community. These discussions often revealed rich information regarding how sustainable social practices unfolded in the ecovillage.

Due to resource restrictions, I was not able to conduct a separate and more extended research stay in Findhorn. However, I have complemented the insights I gained from the experience week with an in-depth study of annual reports, websites, blogs, social media sites, research articles, books about and from Findhorn, brochures, and other documents produced by the Foundation. Findhorn has a relatively richer documentation regarding its history, ethos, current and past practices, and its visions for the future as opposed to the younger Hurdal ecovillage. To fill gaps and clarify ambiguities in these documents, I conducted interviews digitally with key informants with deep knowledge regarding the evolution of the ecovillage (this part of the study coincided with COVID-19 lockdowns around the globe). These interviews also helped to triangulate the information I gathered from documents. In total, I got the opportunity to engage in extended conversations with 14 members of Findhorn community (through home visits, as facilitators of the experience week program, digital interviews, or through their presentations to participants of experience week). The digital interviews with four long term members lasted between 1–1.5 h.

Hurdal ecovillage is in Norway, and therefore, more accessible to me. As a result, I was able to visit the ecovillage multiple times in the period May 2018–July 2019 and conduct participant observation and semi-structured interviews. I participated in a 2-day workshop the ecovillage organized for its residents and interested outsiders to discuss the challenges and advantages the ecovillage faces and chart future paths. There were 20 participants in this workshop, and only two (including me) were outsiders. In total, I gathered information from 15 ecovillage residents. I have also used other sources to complement my field study such as academic articles, master’s theses, newspaper articles, blogs, and a documentary film about the ecovillage. The developer that was a central actor in the ecovillage’s expansion declined to take part in the study. To fill this gap, I interviewed residents that worked closely with the developer and studied publicly available business letters, presentations and reports. Interviews in Hurdal ecovillage typically lasted 1–1.5 h.

The questions that guided the interviews in the ecovillages were (1) the motivations for moving to the ecovillage, (2) the values that guide the ecovillage, (3) the type of shared/sustainable practices prevalent in the ecovillage, (4) the advantages and challenges of living and/or running a business in the ecovillage, and (5) the main challenges that the ecovillage is currently facing. I adapted these questions to fit the particularities of each ecovillage. Follow-up questions helped explore new topics revealed during the interview and that I did not anticipate at the start of the field study.

The Norwegian Center for Research Data approved the study design, including interview guides and the data storage and analysis plans. I informed the study participants about the purpose of the study and how the gathered data would be stored and analyzed at the start of the interviews. When interviews were recorded, I asked the respondents for their consent and guaranteed them anonymity. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed in the software Nvivo 12 Pro [].

I conducted content and thematic analysis on interviews, documents, and participant observation notes []. Descriptive coding captured new themes arising from interviews and documents while concept codes identified themes corresponding to the theoretical discussions elaborated in Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4 example, the elements of social practice following Shove et al. []. Where possible, I presented and discussed preliminary results with study participants (this was possible for Hurdal ecovillage).

4. The Ecovillages: Findhorn and Hurdal

Findhorn and Hurdal have several decades of experience with ecovillage living. Findhorn is almost 60 years old and a strong actor in the ecovillage movement. It is a founding member of the Global Ecovillage Network and was recognized in 1998 as UN-Habitat Best Practice for holistic and sustainable living []. Hurdal is over 20 years old and was founded with an inspiration from Findhorn. It has about 150 inhabitants today []. These two ecovillages collaborate, inspire, and support each other. This fact makes them good cases to illustrate how grassroots innovations replicate each other and scale up their practices in their respective communities. Both ecovillages have good working relationships with their local authorities and have influenced local planning processes in several instances.

4.1. Findhorn Ecovillage—History and Recent Expansion

Findhorn Foundation community is located in the North-East of Scotland and has approximately 400 residents []. It was founded in 1962 by three adults (a couple, their friend, and the couple’s three children) who moved into a caravan and worked to sustain themselves by producing most of their own food and providing for the rest of their needs from unemployment benefits and child support []. The central features of their spiritual practice are tuning in to intuitions/inspirations and connecting with what they called ‘nature spirits’ (through meditations) to find guidance on how to tend to their gardens. Their spiritual and environmental values attracted other similarly inclined individuals which tended to be single and able-bodied and could engage in a full day’s hard work []. The community eventually expanded and became demographically diverse with members in different age groups and family situations.

The community’s development can be roughly divided into three broad phases in relation to physical/infrastructural development. The early phase stretches from the 1960s to 1980s. This is a phase of significant transformation from a small spiritual community struggling to find a solid footing to one of physical and economic expansion []. In 1972, the community established Findhorn Foundation as an educational charity []. In the following decade, the Foundation set up educational facilities and accommodation at four locations: The Park Ecovillage (popularly referred to as The Park), Cluny Hill College, and two retreat houses (on the Isle of Iona and the Isle of Erraid) [].

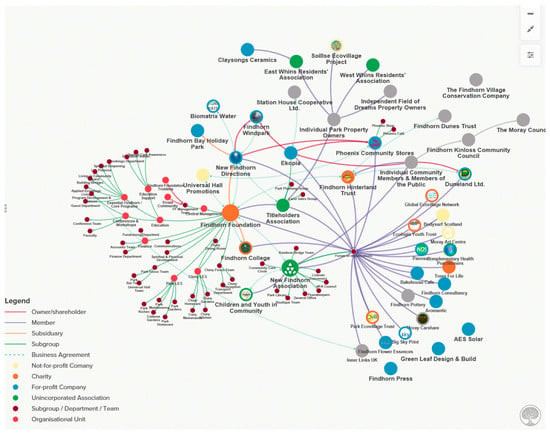

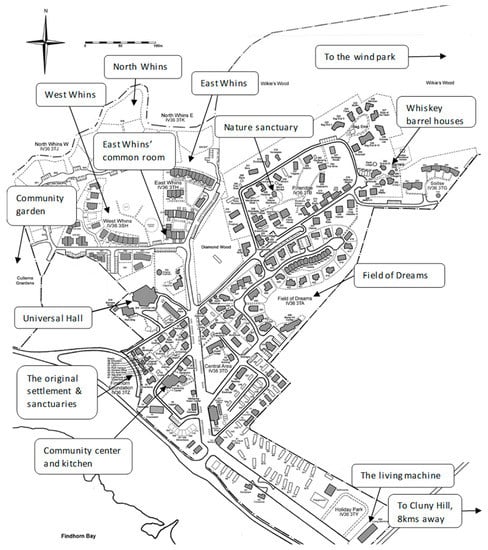

The Park and Cluny Hill facilities occupy prominent status in the community. The Park is the initial settlement near Findhorn village and hosts several community businesses, the community center, privately owned eco-houses, and residential buildings for Foundation co-workers. Some examples of the more than 40 businesses established in affiliation with Findhorn community are Findhorn Foundation College (a tertiary education institution), New Findhorn Directions Ltd. (a trading subsidiary of the Foundation), Moray Steiner School (supported by the Foundation), Trees for Life (a nature conservation organization), Living Technologies (an organization that builds biological sewage treatment plants and restores lakes), Earthshare (an organic agricultural co-operative), Ekopia Social Investments Ltd. (a cooperative that serves as a ‘community bank’, runs the community’s local currency, funds social enterprises like the community’s Phoenix Cafe and finances affordable housing projects) among others. These businesses belong to an umbrella organization, New Findhorn Association, which gives them access to the Foundation’s facilities such as the Community Center and other benefits [] (see Figure A1 in Appendix A for an organizational map of the Findhorn community. Cluny Hill also hosts courses and retreats and houses about 40 Foundation co-workers []. At its busiest, Cluny Hill can accommodate up to 150 guests and residents []. The foundation acquired these properties either through gifts and charities or it bought/leased them with resources generated through fundraising or from educational activities [].

In the early days, all community members were part of the Foundation (ibid). With time, different forms of memberships evolved to accommodate an increase in interest from the outside world. Full-time and associate members go through a three-month-long orientation program and volunteer in one of the Foundation’s work departments. The orientation program includes the introductory ‘Experience Week’, a series of spiritual and self-development programs, spending a week at a community retreat, and once-a-week meetings. Participants in these programs learn the core principles of the community and gain skills for community living and working with community projects. Full members receive a small stipend and in-kind transfers in the form of free meals, accommodation and energy provision [,]. Non-residential foundation workers receive a minimum pay of GBP 9/h. [].

Many of the community organizations were founded by associate members ‘allowing the foundation to focus on what it considers its core business, which is education’ [] (p. 371). The flexibility in types of membership attracted individuals with different sets of skills: environmentalists, engineers, people with background in finance and organizational management among others. More recently, with the expansion of the community through housing developments, people could join the community as property owners or tenants without going through the formal process.

The second phase of development is the period from the 1980s–2000s, where the ecovillage concept gained prominence. The impetus to establish an ecovillage came about after Findhorn hosted the conference, ‘Towards a Planetary Village’, in the early 1980s []. The concept ‘planetary village’ (a village whose social and environmental principles have global perspectives) can be seen as a precedent to the ‘ecovillage’ concept. Inspired by this conference, central individuals galvanized the community to raise funds and buy the land the Foundation occupied, reducing costs and providing revenue sources for the Foundation.

This expansion of the physical premises and accompanying economic activities resulted in economic gains. The Findhorn Foundation surpassed a total revenue of GBP 1 million in the early 1980s []. Educational activities have increased significantly since the early days resulting in more than doubling of income in recent years [,]. However, the community also has significant labor and infrastructural costs and therefore, resources are often tight [,].

In 1995, a group of Foundation members established the company, Ecovillage Ltd., to buy an adjacent land and set up eco-friendly buildings []. Ecovillage Ltd. raised funds by selling shares to community members and plots to people that wanted to build eco-houses []. About 30 private houses were completed in an area they called Field of Dreams in the early 2000s []. With time, these houses became much more expensive than the rest of the ecovillage, with average prices of around GBP 318,000 in 2019 and a peak of GBP 385,000 in 2013 []. The earlier, more experimental Whiskey Barrel houses that the Findhorn community is known for cost about half of the price of the higher quality, timber-frame houses in Field of Dreams at GBP 165,000 [].

The last phase of physical infrastructure expansion took place in the early 2000s. A neighboring land came up for sale and a community organization, Duneland Ltd., was set up to acquire this piece of land and build new houses []. Duneland raised money by selling shares to community members and outsiders and promising priority access to future developments. It successfully bought 292 acres of woodland, dune, and marram grass landscape (ibid). Duneland made several decisions that emphasize its role as a social enterprise: it converted 95% of the acquired land as a nature reserve (in cooperation with Findhorn village) and implemented a financial policy of capped dividends for its shareholders []. Duneland will also cease its activities after developing the land it acquired (ibid).

Duneland conducted two community consultations in 2004 and 2006 and created a development plan which included a mix of educational, community, commercial, and eco-friendly residential buildings []. The plan was granted permission by the Moray Council in 2008. The construction of houses was planned in three phases in the area called the Whins: 1. East Whins, 2. West Whins and 3. North Whins []. East Whins was planned as a cohousing cluster with 25 two- and three-bedroom units (70 sqm and 105 sqm, respectively) []. Phase one was expected to pay for the infrastructure and to honor shareholders’ investments []. Half of the cluster was reserved for shareholders as part of the commitment made to them by Duneland Ltd. [].

Phase one faced some serious challenges. Duneland had severely underestimated the costs of constructing new houses. Consequently, it incurred a debt of half a million pounds []. In addition, a construction company went bankrupt without completing its tasks and a local company had to finish the construction []. This was a period of a steep learning curve for Duneland.

After completion (in 2014), the market price of the units in East Whins became quite high compared to local incomes, ranging between GBP 160,000 and GBP 238,000 []. Although Duneland hoped more community members would utilize their priority access to the housing units, there were a number of single retirees (some living abroad) that acquired the new housing units []. To avoid the houses from being used as vacation homes, Duneland required that the units should be occupied nine months of the year []. However, some fulfilled this requirement by renting out their units.

Lack of affordable housing for community members was a persistent problem. The Foundation observed that young people—Especially young families—Left Findhorn Ecovillage for lack of a ‘suitable’ home and more Foundation coworkers commute to the Ecovillage from the nearby town of Forres and Findhorn village, with vehicle running costs adding strain on minimum wage earners []. In order to alleviate this problem, the community established a cooperative—Park Ecovillage Trust (PET)—to serve as a delivery agent for affordable units []. PET has over the years overseen the acquisition and distribution of affordable units in the Wins by raising funds from Ekopia—a cooperative that serves as a ‘community bank’, local authorities, and in collaboration with Duneland [].

Duneland chose a terrace design for East Whins to use land sparingly and reduce built-up areas. The design also reduces building costs and uses energy efficiently. All houses are fitted with solar panels for hot water and they get their electricity from the wind park. The houses are connected to the biological sewage treatment plant that the Foundation manages []. The layout of East Whins supports co-housing principles of shared/collective facilities with shared common room, laundry, bike shed and communal garden areas (in addition to small private gardens). The management of the natural area is guided by permaculture principles. Ground floor flats are designed to cater for the elderly and physically impaired. Other considerations that went into designing the housing units are linking important sites, such as the community gardens and the Universal Hall for cultural activities, from the original site at the Park with the new developments [].

Learning from East Whins, Duneland set up the West Whins project to ensure its financial viability. It hired an experienced contractor and included low-risk elements such as self-build plots for people interested in building their own homes in consultation on house design and ecological footprint with Duneland and Findhorn community []. PET also oversaw the building of six affordable housing units (ibid). The funding strategy for the affordable housing units prioritized borrowing within the community (through Ekopia Ltd. and private loans) and a grant from the Scottish Rural Housing Fund. Construction was finalized in 2017, and PET made the six single-bedroom flats in West Whins available as eco-friendly and affordable rented units for community members and employees working in the Park (ibid). West Whins was financially successful and enabled Duneland to pay down its debt.

Duneland built a common house for West Whins that included common facilities like laundry, a meeting room and a room for guests of residents. However, as the focus in this project was the financial viability and the community aspect received less attention, there were disagreements regarding the use and relevance of the common facilities []. Consequently, the house was put up for sale at the time of this study.

The final phase of development is in North Whins with a possibility for 38 one- and two-bedroom houses and commercial units designed as a terrace []. There is no plan to set up a common house with shared facilities []. Government grants for eight affordable units have been secured and construction will start as soon as the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Scotland is lifted [,]. Duneland has the ambition of finally being able to repay the investments of shareholders and possibly some dividends after the completion of North Whins.

4.2. Hurdal Ecovillage—History and Recent Expansion

Hurdal ecovillage is located 80 kms north of the capital city of Norway, Oslo, and was established in the late 1990s by a group of individuals that had a vision of starting a small community around ecological farming and spirituality []. Central individuals among the early pioneers in Hurdal spent their formative years in Findhorn and returned to Hurdal with the aim of establishing a similar community []. They established a cooperative called Kilden økosamfunn—or Kilden eco-community—with a member size of somewhere between 50 and 60 individuals and started searching for a suitable location within an hour of the capital for a few years []. They visited several locations that fulfilled the conditions of having good agricultural land and being close to Oslo.

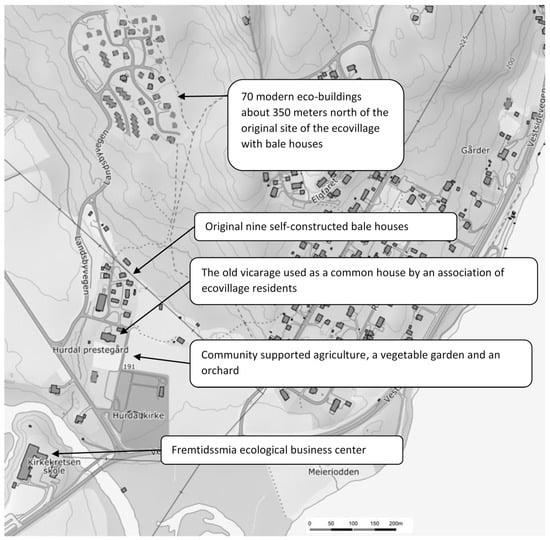

They eventually found an ideal location—a former priest’s farm owned by a willing and eager municipality in Hurdal, an hour outside of Oslo. A group of about 10 individuals, some with small children, from Kilden økosamfunn decided to settle in Hurdal municipality and established a cooperative called Hurdalsjøen Økologiske Landsby SA. This decision meant that the Kilden eco-community split into two. The other group continued with their search, but it appears that this other group did not establish any other ecovillage and may have disbanded. They signed a letter of intent (LoI) with the municipality and rented the farm in 2002 []. The members of the cooperative had equal shares and decisions were made through consensus. They built nine houses in traditional ecological fashion with clay, straw, and wood in the period 2002–2003 (ibid). Although, these houses did not meet the Planning and Building regulations, the municipality allowed them to stand temporarily until more modern housing could be built [,]. The dispensation from the Building and Planning Regulations was extended several times and these houses were used as residence for seven years. When the ecovillage finally got built, the inhabitants of these houses moved into the new houses. The old traditional houses are still standing at the time of this writing and are used to house volunteers and temporary visitors.

In this early period, it was common to share living space until new members could find a footing in the community and have their own housing [,]. New members had to go through an introduction course and a trial period of 6 months. After the trial period, they could pay a deposit to own a share in the cooperative and then a monthly payment to cover common expenses []. They envisioned that everyone would build their own house but soon realized that this was unrealistic. Some of the traditional houses they built had construction problems and they did not have the necessary legal and economic expertise for other forms of expansion (ibid).

The cooperative bought the farm from the municipality in 2004 and decided to collaborate with Gaia architects—A firm working on sustainable design—To develop zoning plans for the development of the ecovillage []. This plan was unanimously approved by the municipality which paved the way for the cooperative to buy the farm in 2006 [].

Architects and investors saw the potential in this new venture. The cooperative’s members looked for actors with the financial capacity and legal know-how to relieve them of the economic burden they were carrying from their attempts at building an ecovillage on their own []. The company Vitrina (later Filago) offered to buy out members of the cooperative and take over the responsibility of developing Hurdal ecovillage. The farm was sold to Vitrina in 2012.

The decision to sell the farm to an investor was not unanimous []. Some members left the cooperative because they felt that they were straying away from a locally anchored, bottom-up process of building the ecovillage. Those that remained argued that expanding an ecovillage through self-built houses required considerable time, energy, financial resources, and expert knowledge, which they did not have (ibid). They saw a legally binding recruitment of new residents for future (modern) houses with prospectus as the most efficient and secure option.

Filago (earlier Vitrina) adopted an innovative business concept when they took over responsibility for developing the ecovillage []. Their business concept, which they termed ‘living and lifestyle concept’, was to set up eco-communities of different sizes where social and environmental values were central []. They founded their business on the stated goal of balancing ‘the triple bottom line of sustainability: people, planet and profit’ []. They aimed to realize this vision through building eco-houses and collaborating with municipalities, residents and the local business community (ibid). Filago aimed to set up the infrastructure for social life (for example, common houses, gardens, greenhouses) but the residents were responsible for creating activities []. The ‘products’ they promoted to potential customers include ecovillages with 50 or more housing units, eco-hamlets with 20–50 housing units, and eco-yards of 5–20 housing units among others []. Hurdal ecovillage was marketed as the physical manifestation of Filago’s business concept and as such received funding from state enterprises, for example, from Enova—the state-owned funding agency for innovative and environment-focused projects [], banks (for example, Husbanken provided affordable mortgage loans to residents) and crowdfunding agencies.

The houses were constructed with four fundamental principles: natural indoor ventilation (using small, sensor-operated valves on walls that are breathable), environmental considerations (for example, using non-toxic building materials), energy efficiency (including use of solar energy), and modern comfort [,]. With these considerations in mind, different sizes of module-based buildings, called shelters, were designed. The houses were smaller in size than the average Norwegian home for energy and cost efficiency [].

Filago planned to develop Hurdal ecovillage in five housing clusters (ibid). The first cluster was developed in two stages. Construction of the first group of houses began in 2013 and was completed in 2014/2015, and the second group was finalized in 2016. The original plan included a common house for the residents to use for social and economic activities. However, the cost of the first group of houses exceeded the budget and therefore, Filago abandoned the plan of building a common house and instead built the second group of houses on the plot to generate extra income []. All in all, 70 houses were built and sold in the open market []. The prices ranged between USD 220,000 and 435,000 in current exchange rates.

Some cooperative members expressed concern early on that these prices were too high and needed large mortgages, implying that ecovillage life would be exclusive to those with good economic resources []. Others countered that although the prices were high, there would be substantial savings in the long run through the production of solar energy, by adopting ‘simpler lifestyles’ advocated in ecovillages, and other initiatives like establishing an information center for visitors (ibid).

Filago bought and upgraded a neighboring old school as space for businesses and cultural activities. The new center was named Fremtidssmia økologiske næringssenter—Fremtidssmia ecological business center or simply referred to as Fremtidssmia. Initially, some ecovillagers received discounted rental prices from Filago and made use of this space to host cultural activities and courses. However, when the rental prices went up to market levels, it became prohibitively expensive for the fledgling businesses. As a result, many small businesses run out of peoples’ homes []. Some of these businesses include beekeeping and bee products, producing soaps and detergents, running courses and workshops such as yoga courses, and different therapies (ibid).

Residents started initiatives where they could share and exchange resources: sharing circles for clothes, household tools, garden produce, and other goods. Some of these activities take place in the old vicarage that a group of residents rent. They also established a carpooling scheme for ecovillage residents using social media. An association assigns work duties in the ecovillage’s organic farm and started a composting initiative to support the farm. Association members cover some of their own needs with the produce from the farm and they organize workshops that focus on food production. Members collaborate with farmers in the municipality to create a local brand and market the region’s food products [].

There was a growing discontent among the residents with some of the houses as they were experiencing technical problems []. Some houses experienced leakages and structural damage. The wireless smart technology that regulated lighting, window shades, ventilation valves, and electric outlets did not function well []. Although the technology was billed as energy and cost effective, its instability made it lose favor with the residents. In addition, some residents are concerned about radiation from the wireless technology. Consequently, some opted to change to an old-fashioned but stable cable-based technology at extra costs [].

Subcontractors of the developer who would have been legally bound to fix the problems went out of business and made it difficult for Filago to fix these problems. These complications broke down the trust between the developer and the residents []. There were rising tensions between the residents and the developer, and between different groups within the ecovillage.

These problems had an economic toll on the developer. In early 2018, their financial security became uncertain []. The prevailing tension and conflict in the ecovillage and unresolved technical problems in the houses hindered further sales of shelters []. A year later, Filago was declared bankrupt by the tax authorities. The firm owed its investors, including national and international corporate finance organizations, banks and crowdfunding agencies, and tax authorities over USD 40 million [,,]. The bankruptcy exposed the ecovillage to uncertain futures. The banks, insurance companies and creditors will determine to what extent the ecovillage will remain intact with its properties, such as Fremtidssmia, plots for future development, and agricultural land []. Many ask themselves ‘will we continue as an ecovillage?’ (ibid). At the same time, some see this situation as an opportunity to reinvigorate the drive to gain more control of the ecovillage’s future development. However, with the extensive debt that the ecovillage currently carries, they are dependent on finding an investor that can take over the financial burden (ibid).

5. Results—Connecting Material Expansion to Values and Competence

5.1. Material Expansion and Values

5.1.1. Findhorn Ecovillage

Throughout its history, Findhorn has experimented with co-existence and community living. The values that drive sustainable practices in Findhorn community were initially informed by the founders’ spiritual practice that focuses on inner listening, co-creation with nature and love in action. Spaces such as Cluny Hill College have served as a collective where residents have shared a large communal kitchen, spacious living room areas and laundry facilities since the 1970s. The community center at the Park serves lunches and dinners to community members (see Figure A2 in Appendix A for an overview of common facilities at the Park). The common garden provides some garden produce to the community and serves as a site of therapeutic work for troubled youth from the Moray area. These sharing practices have, historically, contributed to lowering the community’s impact on the environment: a 2006 study of the community’s ecological footprint found that the community had half the footprint of the average UK resident, primarily because of Cluny Hill that houses so many residents with shared facilities [].

The values espoused in the spiritual guidance of the founders have inspired many of the organizations and infrastructural projects in the community. They have guided the organization of social life in the community, informed social practices such as self-sufficiency in food and energy provision and inspired the building of physical structures. As one long-term Foundation member involved in several of the community organizations stated:

Spirituality is the community glue that keeps people together. […] the ecovillage is … an expansion of the spiritual side of it. So, it made sense for the community to build up the wind park. […] It ultimately is about how to take that and make it into ‘love in action’ which is the cohousing or what you experience in the Foundation (FH07).

The Findhorn Foundation built a strong foundation by weaving together values/meaning, material expansion, and competence. The interweaving of values and competence happened through educational courses and workshops. The competences cultivated by these activities are, among others, taking seriously the impulses and inspiration that arise within through attunement and ‘deep inner listening’ and manifesting these ideas into reality (i.e., ‘love in action’) by working with nature (i.e., ‘co-creation with nature’) [,]. Attunement is one of the first practices new members get introduced to and it is one way the community perpetuates the values and practices of the community. Typically, people would sit/stand in circles, hold hands for a few minutes in silence to turn the attention inward, reflect on the issue at hand and take note of ideas/inspiration/concerns that may arise before sharing with the group. This practice is conducted at the start of duties in work departments and before managerial teams make decisions after all other considerations are evaluated []. These values inspired many key individuals to utilize their particular skill sets and prior experiences and initiate different projects with diverse goals: self-sufficiency in terms of energy, building eco-houses, natural conservation projects, infrastructural maintenance, building affordable homes for members, etc. These activities serve several goals: they provide empowerment through self-sufficiency; they reduce the community’s environmental footprint and they build community. A longtime community member that was involved in many of the early projects sees it as a ‘learning process’:

We could have taken a very different approach. Again, if I go back to ‘Towards a planetary village’ conference, we could have said ‘Look, we don’t want to do any of this stuff. It’s a huge distraction. Nobody is interested in digging ditches and looking after roads. You know? We want to read books about the Buddha and inform ourselves [about] life. Perhaps, we could have done that. But we didn’t. The big advantage is that it forces us to work together. It’s very difficult to see the Park becoming a kind of suburban place that used to be a community. Because people have to work together whether they like it or not. The electricity supply, the water supply bla bla bla, all of these things, even if we choose not to pay much attention to it, you have to pay for it and you have to, by some mechanism, engage in it. And so, it’s kind of part of the curricula, if you like. It’s part of a learning process even if it’s not very economically efficient or not the most economically efficient thing (FH02).

5.1.2. Hurdal Ecovillage

The founders of Kilden eco-community were inspired by the spiritual values of Findhorn community and wanted to manifest it in their own community [,]. They aimed to utilize ecological building materials and adopt circular processes in food production and waste processing. The pioneers envisioned treating water resources with care: collecting rainwater, implementing biological treatment of wastewater and protection of ground water quality. They viewed development of an integrated energy system with renewable energy sources as an important aspect of an ecovillage. They aspired to reduce consumption and live simpler lives to protect the environment and to contribute to intra- and inter-generational equity.

They envisioned a local economy that can be adapted to support the community and financial systems that can encourage the circulation of money locally. They advocated for a sharing circle where individuals can share and exchange artefacts and services and a value-based education system that includes permaculture and meditation courses. Seasonal celebrations and cultural diversity were envisioned to foster interconnectedness with other human beings and nature [].

The wish to expand the ecovillage a decade later required some fundamental changes to the idealistic view espoused by the pioneers in Kilden eco-community []. They had to find a workable common ground with the local municipality’s zoning and planning rules, building codes, and the already existing infrastructure [] (see Figure A3 in Appendix A for a map of Hurdal ecovillage). The decision to opt for a developer-led expansion of the ecovillage meant that the introductory courses and trial periods of the early days had to be abandoned. Several residents saw this as a negotiation between the idealist origins of the ecovillage and the capitalist world it tries to engage with. A pioneer involved from the early stages of this process describes it as follows:

I have also gradually come to a kind of demanding position because when you... start to involve companies and banks and eventually also investors, it becomes, in a way... I have to build a lot of bridges [between] a commercial capitalist world and… an idealistic world which is where I come from. And then you try to find a balance and then you have to create enthusiasm for it and constantly try to keep a momentum. And that has in a way been my life for maybe 20 years (HL14).

In trying to appeal to a broad base of potential buyers, Filago referenced sustainability—mainly in the form of eco-houses—and social life in broad terms. Different buyers had their own expectations of what an ecovillage is. For some, it represented a possibility to be close to nature, for others it represented a possibility to raise children in a community, and yet for others, it represented a possibility to explore spirituality in a community of like-minded people. These motivations did not always align well with each other.

The lack of a clear identity for the ecovillage resulted in some residents feeling that the ecovillage did not reflect their convictions or identity. For example, one resident explained that she moved to the ecovillage to pursue her deep convictions about food self-sufficiency and living a simple life. However, there was no longer a place for her vision of a low-tech, simpler form of an ecovillage in Hurdal any longer.

I mean, there’s a difference between people here, but I do not live in this house because I think the house is so nice. I came to the ecovillage to live down there [in the straw-bale houses] and I could have stayed there. For me, the house here does not represent me, I do not want smart house solutions, I would have liked a compost toilet, I would have liked to have had all those things, but it was in a way… [the ecovillage] became a package, so either you bought the house here, or not (HL08).

5.2. Material Expansion and Competence

5.2.1. Findhorn Ecovillage

As elaborated in Section 4.1, the Foundation has always operated with small economic margins which led to the ambition of physical expansion to bring in more people and generate economic activity. With the construction of new houses by Ecovillage Ltd. and Duneland Ltd., the strict adherence to introductory programs for new members was relaxed. Without an introduction to the ethos of the community, new owners and renters do not start from a common vision, nor do they gain skills for community living. An additional problem is the turnover of tenants that disturbs the flow of social life. Consequently, these new clusters experienced conflicts around the use of common facilities. An East Whins resident lamented the fragmentation that this caused the community:

East Whins is a cohousing...and that would indicate that these 25 units … should have more in common than just anyone... these 25 should be more jellying together than the other 200 [in the wider Findhorn community]. And we don’t. […] And if you have a conflict and you spend a lot of time solving that conflict and then that person moves away because they are a tenant, that’s ok because the next one that comes in, you hope, may be different. But when you have moving parts all the time, then you are like in a spinning machine. … So, in my numerical mind, we’re 37 adults who are owners in 25 units, of those 37 adults, maybe 13 or 14 are here at any given moment in time. And that’s an important figure because it’s the adults in the cohousing, that make it jell (FH05).

In many of the units there are two individuals that neighbors have to relate to: the owner and tenant. The owner is expected to be a part of the infrastructural decisions concerning the units while the tenant is the one that has to engage socially with other residents. Managing the dynamics described above requires a certain level of competence. Residents developed solutions to improve the situation by organizing meetings and working through difficulties. There are two examples of solutions they found that improves the dynamics in East Whins. The first is that they assigned one resident to be responsible for social activities in the community. The other solution is the separation of property ownership from the social life in the cluster to ensure tenants could fully participate in daily decisions and activities.

I think we have done pretty well here; in that we separated the ownership from the social. That’s something we did 2 years ago. … We have owners who’re not here and we have residents who are not owners. … Two years ago, we formed a company limited by guarantee and all owners are members. … That company looks after the financial viability and our commonly owned facilities. … This is East Whins Cohousing Company. Ever since 2013, we have operated … with sociocracy. So, when we formed the company, we just made it more clear to people that the company is for the owners and the sociocratic circles, that is for everyone who lives here. If it’s a 6-week tenant or a 6-year tenant, everyone should be involved in [the sociocratic] circles... [for] the day to day running. And they run the budget that has been applied by them but approved by the company. So, this makes the safe running [of the cohousing] possible…(FH05).

The adoption of sociocracy—A decentralized decision-making system []—is similar with the practices of the larger Findhorn community. This is an area where we see an alignment of competences between the smaller community of East Whins and the larger Findhorn Foundation. Through this decision-making system, information flow and coordination with other community organizations becomes easier and facilitates transfer of skills and competences.

East Whins residents have also successfully started a food composting initiative led by one resident. This resident attended an educational presentation organized by PET and felt inspired to initiate a composting initiative for East Whins residents. A community leader working in PET describes how the process unfolded:

We had a presentation about Drawdown. Probably the first one was 5 years ago which I believe PET actually facilitated and sponsored. […] Evelyn became aware of the role that food waste played in the global footprint and how […] composting of food waste […] will have a huge impact if it is taken up on a larger scale. So, she felt inspired to take that up locally by buying what she calls... I think they’re called hot boxes. And hot boxes are simply super insulated composting bins that are capable of accelerating the decomposition of food waste. So, […] she transfers the compost on to a nearby garden which she also tends in East Whins right in the corner, in front of what’s called the sunshine room in East Whins. So, there she’s got a nice little self-contained community facility she’s inviting anybody with food waste to contribute and quite a number of people do. … I believe she now has something like eight of these hot bins; processes quite a lot of food of her own accord. Now, those are for … home owners or tenants because the Foundation also does something similar with its food waste on a much greater scale (FH14).

West Whins had a different developmental trajectory. As mentioned earlier, to avoid the financial troubles Duneland faced after East Whins, they prioritized the financial and infrastructural side of the project. However, the community aspect of it was neglected. A common house was built in the cluster to foster ‘community bond’ through the management of the collective facility. To recall, West Whins is composed of two housing types: self-built and affordable units. The more affluent owners of self-built houses were less interested in the common house that came with the cluster as it requires time and effort to maintain and manage. A key informant with knowledge of how the process unfolded stated it as follows:

[I]n glib terms, the bigger the person’s house, the less interest they had in a common facility with a washing machine in it. They got four bedrooms and two washing machines. What the hell do they need a common facility for? Whereas, you know, people in affordable housing were much more attached to it. So, as an experiment that didn’t work either and the place is now up for sale. […] May be, in 10 years’ time, people will be complaining bitterly about the fact that there are no more of these facilities (FH02).

Learning from the two earlier projects, Duneland decided not to build a common house in North Whins. Instead, they left a plot of land open for future development should this be interesting for residents. This decision and the quote above indicate that community leaders see a value in a common physical venue to foster community and nurture skills for shared practices.

To summarize, there are three groups of residents in the Findhorn community: Foundation members/co-workers, home owners, and tenants. The Foundation’s members gain a wide array of skills that align with the spiritual values of the community. They engage in different work departments such as the gardens, the kitchens or community care or they run community organizations as associate members. Working with practical tasks such as energy generation, growing food or biological treatment of waste gives them the skills needed for a low-impact community life. The social competences they build through attunements, community building exercises and communal living (for full-time members) help them improve communication and conflict resolution skills.

Newer residents in the Whins are not required to attend orientation programs. However, as the quotes above show, East Whins residents managed to develop new skills and institutions of social organization such as separating ownership from social activities. Their food composting initiative shows how meaning travelled from PET—an affiliate of Findhorn Foundation—to residents that started their own successful food composting system. A carbon footprint study conducted by PET found that close to 70% of residents compost food waste while 88% compost garden waste []. The report credits the East Whins initiative for the high rate of food composting among East Whins residents.

The move away from including a common house and common facilities in West and North Whins reduces opportunities for developing the necessary skills for sustainable living—interacting with each other to create room for new ideas and initiatives, communication and conflict resolution skills to work on common projects, establishing local businesses that could reduce commuting, and the like. However, West Whins is still a young community and North Whins is not yet built. Therefore, it will be interesting to see how the situation develops a few years down the road.

5.2.2. Hurdal Ecovillage

In Hurdal, longtime residents of the ecovillage lament the loss of the introductory courses of the early days. In addition to creating a common ground in terms of values and meaning, the introductory courses imparted competence for a life in community. The course aimed to give a balanced view of what it means to live in a close-knit community by incorporating the type of challenges that might arise and ways of solving them. This nuanced view of ecovillage life was replaced by a romanticized and marketable image to facilitate a quick sale of houses. A longtime resident describes this change of perspective during the different phases of development as follows:

…I liked [the introductory course] very much. […] Because you got a lot out of the course. When you come here and buy a house, you are told about all the nice things, but the course also had a lot of focus on the challenges of living together in a social community. You have to be willing to undergo personal development, you will get to know other aspects of yourself that you may not know, so I think it was an incredibly good presentation of all the challenges that also follow with living in community: there will be quarrels, there will be dishes flying through the air, there will be, yes, it can be very close, very, very scary, too. … Many ecovillages have such admission requirements and things like that. So, it is in a way quite common, but it was stopped here because … I feel we are in the interface between the idealistic and the economic world. And here, a lot of the idealism has been lost to economy. Here … there is a developer and the houses should be sold and when you are going to sell something, you have to present it as heaven on earth so that everyone comes to buy it, and what happens afterwards, you don’t give it much thought (HL08).

The developers marketed an ecovillage where social life could unfold while engaging in sustainable and social activities. However, as the economy of the project became tight, they decided against building a common house where these social events could unfold, and residents could informally develop the skills to communicate with and learn about each other. Residents lacked an avenue where they could negotiate the ecovillage’s identity and its purpose through the everyday, spontaneous meetings and discussions that would arise in such a place. One resident explains how sorely missed such infrastructure is:

[We] lack informal meeting places that may actually help us discover that we can resolve these conflicts or contradictions. That we may realize that we actually do not have very different interests. Because I think maybe we attribute to others some qualities that they do not necessarily have. I think maybe people would recognize they have much in common (HL01).

Another resident expresses the lack of such skills to resolve conflicts and find a common ground:

Yeah, so there it is... a lot of things to learn …. there is the personal, the interpersonal, which is, how you talk to all these people when you are not used to talking to others... and talk to people who strongly disagree with yourself. […] [T]here must somehow be [training in] modern conflict management … and communication and different communication platforms. These are the two things that could have made it go faster, so that one could understand each other faster and better (HL02).

Communication and conflict resolution skills are important as they form the basis of social practices that characterize ecovillages. Complexes of practices such as sharing circles, carpooling systems, growing own food and the like draw on similar competences of being able to communicate and work with each other. The protracted conflicts caused by the structural problems of the houses, the lack of trust towards the developer, and the lack of consensus regarding the social organization and identity of the ecovillage means that residents do not have the opportunity to develop these skills and establish a thriving local economy.

The business center, Fremtidssmia, was initially planned to be a place where ecovillage businesses could be established. However, with the level of investment that went into upgrading it, the costs became prohibitive. Many residents express their hesitation to establish their businesses in Fremtidssmia for fear of not being able to afford the rent. Others have to find jobs in larger cities such as Oslo. A resident describes the resilience of residents starting their businesses in their homes while others commute long distances as follows:

People are producing things. We are producing honey. And now there are some guys producing jød—or mead, almost like beer but with honey—it is a Viking beverage. A lot of people are producing kombucha […] and exchange in different ways. Some people are producing soaps and detergents. These are mainly running out of people’s homes because the rent has been so high up there. That’s been the situation because they spent so much money restoring this place so the rent went up. That kind of put a lead on the entrepreneurship, I think. […] Now many people are commuting and it takes a lot of time and some people are not able to get jobs. They’ll want to go to Oslo to work so, it’s a difficult situation for some people (HL11).

To summarize, the physical expansion in Hurdal ecovillage took the form of high standard, expensive housing and the business center—Fremtidssmia. The costs of building eco-houses exceeded the budget and resulted in significant losses, possibly due to limited competence in the economics of building eco-houses. Ecovillage introductory courses were abandoned in the marketization of the ecovillage and with this decision, competence building for community living were down prioritized. The resulting lack of consensus regarding the identity and vision of the ecovillage meant that there were increasing tensions and conflict as residents were starting to establish common activities and businesses. Technical problems with the houses exacerbated this problem. The decision to abandon a common house in order to build more homes means there was limited opportunity to build social competence that could help them start common projects or engage in sharing and collaborative consumption that decreases environmental impact. The high cost of rentals in Fremtidssmia dampened the possibility for establishing a strong local economy with a diversity of businesses that can utilize local products or generate innovative ideas.

As the developer was going through its own financial crisis, the ecovillagers were setting up meetings and workshops to come to a consensus on common values and identity. They started the process to establish an umbrella organization with a wide enough mandate that will encompass all ecovillagers. They were organizing courses on sociocracy as they believe it to be a suitable governance system. They committed to reinvigorate social activities (such as a regular communal dinner, children’s activities… etc.) to try to rebuild trust and repair community bonds. They were setting up an initiative to bring together residents with business ideas to create a common platform for all ecovillage businesses. They hoped that these initiatives would help them rebound from the extended period of uncertainty and insecurity they experienced in the previous year.

6. Discussion

Ecovillages are important community-level experiments in alternative and sustainable lifestyles. Wilhite [] (p. 108) maintains ‘[the ecovillage concept] combines the goals of minimal environmental intrusion, social inclusion and collective decision making. It challenges the capitalist fundaments of private ownership and individual accumulation’. Typically, ecovillages implement one or more of the following mechanisms to achieve this: collaborative housing, for example, communes and cohousing, a local economy and local currency, connection to nature, a strong social fabric, and collaborative forms of consumption such as clothing swaps, toy sharing, shared workspaces, ride sharing, food co-ops, time banks, bartering, local exchange trading systems and the like (ibid).

The ecovillages under study in this paper have experimented with several of the above-mentioned practices (for example, collaborative housing, local currency, collaborative consumption, ride sharing, clothing swaps and the like). These practices fit the definition of complexes as they draw on similar materials, meanings and competence. This article aims to examine how the expansion of these ecovillages affected the elements that are necessary to maintain these complexes of practices. By following Shove et al. [] approach to social practice theory, the article poses the research question: how does the choice of developing the infrastructure needed for a sustainable lifestyle promote/limit the development of the necessary competence and meaning for such a lifestyle?

Findhorn ecovillage is the source of the meaning and competence for the development of the ecovillages. Findhorn’s founders grounded their core values on their spirituality and developed relevant competences for self-sustenance. The competences they developed were tuning in to one’s inspiration and intuition and to work towards that ‘calling’ in a dedicated manner. This has resonated with people from around the world that flocked to the far-flung community in Northern Scotland. These newcomers brought with them prior experiences with spirituality, construction know-how, environmental expertise, and organizational work among others. As Seyfang and Haxeltine [] (p. 32) observed in their studies of grassroots innovations, individuals with innovative ideas were given a ‘protective space’ in Findhorn to develop these ideas. When their ideas generated good economic returns as in the Field of Dreams project, the Foundation benefits by diversifying its sources of revenue through service provision such as energy and infrastructure, gaining access to resources such as land or spreading risk. This will again help it to continue with its core work of education and spirituality.

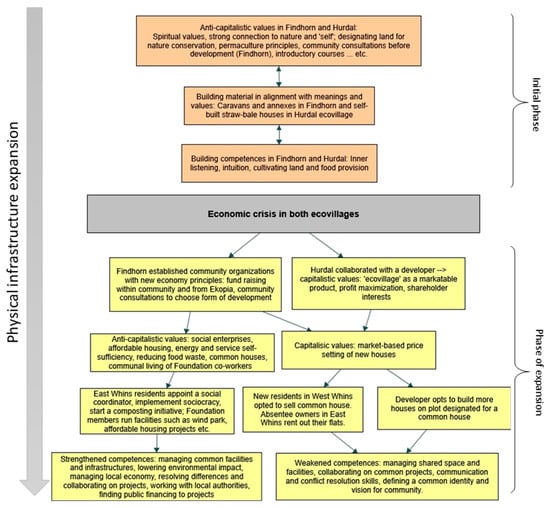

In the early phases of their development, both Findhorn and Hurdal ecovillages had similar paths (see Figure 1 below). Both started out with clearly developed ‘meanings’ and value orientation that revolved around spirituality and deep connection to and working with nature. Both places started with simple and traditional housing as the ‘material’ basis for living out their principles. In Findhorn, this took the form of caravans and annexes while in Hurdal, it took the form of straw-bale buildings. Both started acquiring ‘competence’ on food provisioning and building technologies. However, they soon started facing economic problems and began to experiment with different economic models. Here, Findhorn benefited from its larger community of practitioners with diverse backgrounds that could raise funds from within the community and from the community’s extensive network. Hurdal, however, had to find investors that could take over the economic burden. From here onwards, the experiences of the two ecovillages started to diverge.

Figure 1.

The path of expansion of Hurdal and Findhorn ecovillages and the impact on the elements of sustainable practices.