Abstract

This research is a contribution to the sustainable assessment of industrial heritage. The study analyzes the sustainability of some industrial elements after the cessation of activity as well as their tourist definition. The research includes a bibliographic review, a study of different sustainability thematic groups, and establishes certain analysis criteria in each group, adjusted to the characteristics of each selected case study. The results obtained permit a qualitative assessment of industrial heritage in terms of sustainability and its interpretation as a tourist resource in an increasingly diversified cultural offer. Special emphasis is placed on territory, landscape, environment, architecture, and tourism-related issues as the main interpretative keys that provide a new perspective on industrial heritage through an easy-to-apply analysis that contrasts operationally with other heritage environments.

1. Introduction

Factories and mining areas reclaimed for tourism are one of the most visible and recent facets of new cultural trends. Their interest lies in the fact that this kind of tourism differs greatly from other standardized forms of mass tourism. On one hand, mining and industrial heritage tourism has generated new and competitive products within the framework of an increasingly complex diversification, applying interesting projects in which the emphasis is placed on some relevant, almost unavoidable aspects: the prominence of the territorial framework; the local population’s participation; and effective management based on rational and sustainable principles of the new use of existing resources. On the other hand, this tourism is set in a context of social change and a new global productive model in which only a commitment to new, coherent, and quality cultural and tourist products can achieve success and general recognition. In this sense, the challenges of tourism management are important because it is necessary to create new strategies to address environmental concerns, crisis management (such as the current one arising from the COVID-19 virus pandemic), and cultural development plans aimed at promoting a process of tourism management of heritage appropriate to its own characteristics [1].

Cultural tourism started growing as a mass phenomenon at the end of the 20th century and prompted people to begin regarding heritage as a legacy, but tied not so much to the aesthetics as to the broad inheritance handed down by a local community in a given space [2]. This change in concept was the result of the progressive evolution of ideas in the field of protecting the components inherited from the past and the cultural landscape concept. Although the origins of the term “cultural landscape” are to be found in some late 19th century French and German geographers such as Ratzel, Schlütter, or Vidal de la Blache, the current meaning appears at the beginning of the 20th century with the Berkeley School and, especially, with the figure of Carl Sauer [3,4]. This was when the cultural landscape was defined just as it is interpreted today as a result of the continuous action of a social group over time on a specific natural landscape [5].

The legacy of these authors was readopted in the last third of the 20th century, implicitly by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), when the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage was held in Paris from October to November 1972, and explicitly in 1992, with the UNESCO Guidelines for the implementation of the aforementioned Convention. It was then that the concept of cultural landscape was defined for the first time, in Article 1, as a set of cultural property representing the works of man and nature. Another later reference, in relation to landscape as a result of the interaction between society and nature, comes from the European Landscape Convention, held in Florence in 2000.

The cultural importance of the landscapes associated with industrial and mining sites can be seen from the fact that some of them have been declared as World Heritage Sites: in 1978, the salt mine of Wieliczka, near the Polish city of Krakow, was protected with this category, as was the factory town of New Lanark, in Scotland in 2001. These are just two significant examples of a long list of sites with maximum protection that extends throughout most industrialized countries with representative examples of the different phases of historical industrialization. This shows that, over time, industrial and mining activities ended up being considered as a key factor in the capacity to shape cultural landscapes. However, industrial heritage is a category still under-represented on the World Heritage List. Only around 6% of all cultural heritage and 4.5% of the entire list represent industrial sites. Of a total of 1121 places included in the list in 2019, only 50 were industrial. In addition, there is a strong geographical decompensation: most of the industrial sites recognized as world heritage are in Europe and North America. Although most authors acknowledge the increase in registration by industrial sites in recent decades, it is considered necessary to increase and diversify the UNESCO World Heritage List with more heritage sites of industrialization [6,7,8,9].

The scientific study of industrial heritage developed almost in tandem with its protection. The investigations began in England, France, and Germany due to their strong industrialization. The first objectives of analysis and interpretation were the most significant industries of the 19th century, an example of the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. Later, studies focused on other cases and were extended to the rest of the industrialization phases. Finally, the aesthetic and cultural interpretation of industrial and mining landscapes, and recreational recovery as places for tourism, are the main focus of attention currently and the most prominent research objective [10,11,12].

The landscape of industrial areas is unique and the product of a complex network of buildings and structures, the remains of which require very specific treatment after the industrial activities have ceased. The acknowledgement of their worth, especially in relation to early industrialization, gave rise to the current interest in the industrial landscape in the first few decades of the 20th century as well as in the industrial artifacts of the past and the possibilities for the recovery of large productive containers [13]. In 1939, the first cotton industry museum was opened in Styal (Cheshire) and in 1934, the Ironbridge, a 1779 iron bridge over the River Severn in Shropshire, England, was included in the catalogue of listed buildings. It has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1986 and receives around half a million visitors a year.

From 1970, concern for industrial conservation and its enhancement became widespread, coinciding with the oil crisis, deindustrialization, the reconversion of the means of production, and austerity urbanism. Combined with all this was the evocative and nostalgic feeling caused by the legacy of the industrial revolution due to the accumulation of collective feelings in the industrial territories.

From the end of the 1980s and the start of the 1990s, the focus was on the need to steer tourism toward its most sustainable form as a means of guaranteeing the future of resources and the cultural and natural environment. The World Charter for Sustainable Tourism of 1995 stressed that tourism should become a driving force for local economies and contribute to the participation of local communities as an inexcusable part of the responsible management of tourist destinations. This idea was subsequently taken up at the World Summit on Sustainable Tourism in 2015.

In 2015, the global objectives for sustainable development were also adopted in the framework of the UN Agenda 2030. Using a multidisciplinary approach, 17 different goals were agreed, each with a specific number of targets. Goal 11 refers to sustainable cities and communities and its targets include increasing efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage. In this context, the most recent protection of industrial heritage and its consideration as a cultural legacy of great importance must be understood.

Over the last two decades, there have been many discussions on restoration and introducing new activities into old factories and mines. In some cases, it has been argued that the kind of tourism generated around old industrial areas is compatible with the basic principles of sustainable development [14,15]. These authors highlight social, economic, and environmental benefits as being the most significant aspects of new industrial heritage tourism. However, other authors insist on the difficulties that exist for the permanent generation of wealth and employment, above all when they are in rural areas, due to the complexity ensuing from the involvement of very different players with disparate and opposing interests [16].

In other cases, authors insist on the idea that industrial and mining landscapes are a non-renewable resource that must be conserved and protected due to their high technical and cultural values; and, in a certain sense, this involves reusing the wide range of properties associated with this heritage using sustainable criteria [17,18,19]. Regarding industrial heritage as an element of identity and cohesion of local communities in which the collective memory plays a fundamental role has become a powerful basis for promoting new tourism uses applied through projects that respect the strictest sustainable management and usage criteria [20,21,22].

The fact that there is such a great diversity of specific forms of tourism and very general and imprecise definitions of sustainable development means that some authors believe that the concept of tourism sustainability has been applied too generously [23]. In some cases, all small-scale tourism has been deemed sustainable (as is the case with industrial heritage), but even in these cases, one must delve deeper into the conceptualization of sustainability and the use of indicators to analyze the real situation and future effects. It is very important to pay attention to the economic, ecological, and environmental perspective as well as to the long-term viability of tourism projects [24]. In other cases, sustainable tourism has been understood only as a sustainable form of tourism, with no other considerations compatible with the concept of sustainable development.

The sustainable valuation of industrial heritage requires analyzing in some detail the spatial and architectural compatibility with other uses, selecting activities that cause the least damage to heritage. This is the only way to guarantee that industrial heritage is an element of sustainable development. This intervention strategy is currently the most important, since the previous stage of acceptance of industrial heritage as a cultural heritage has been overcome [25,26,27,28].

Many scientific contributions are related to the role of heritage in sustainable development. Most of them consider that the conservation and enhancement of cultural heritage is an investment. In other words, economic criteria are applied, not necessarily linked to the landscape, tourism, the environment, the built legacy, etc. There is, therefore, an imbalance between the different dimensions referring to sustainability [29,30,31].

Sustainability is a multidimensional reality, whose objectives can only be achieved with global strategies that exceed the strict economic profitability of the interventions and take into account non-monetary values [32,33,34].

In any case, building reuse, the environmental improvement of the territory, rational tourist uses, and the creation of locally based projects and businesses are undoubtedly part of the approach to sustainability. In this general context, industrial heritage has become a real opportunity to relaunch new options for tourist and cultural reuse [35,36,37,38,39,40].

It has taken quite some time for industrial heritage to be regarded as a basic element of landscapes and territorial culture [41]. If one considers the different spaces as unique and unrepeatable social products, using our industrial legacy for tourism purposes allows for the longed-for preservation of the constant confluence of the signs of identity and the uniqueness that so characterize local communities [42,43,44]. It is part of a recent trend that gives a lot of relevance to the local scale compared to the global scale, although it is necessary to note that not as a counterpoint, but as an interrelation between both spatial scales [5].

The objectives of this research are related to each other and are divided into several hierarchical levels: first, the main objective was to assess the level of sustainability of some existing examples of industrial and mining heritage in Spain, considering that they are tourism benchmarks. Directly linked to this main objective are other secondary, albeit no less important objectives: (i) to interpret sustainability as the process by which the protection of available environmental, economic, and architectural resources is improved to promote more coherent social progress in local communities; (ii) to establish different thematic groups and qualitative analysis indicators; and (iii) to assess the case studies from a geographical point of view in which the territory is a transversal criterion that takes on a fundamental role in relation to sustainability.

The sites analyzed are distributed throughout several regions of the country, in different locations, and always with distinctive features. They are all united by the fact that they form part of the Spanish list of the main elements of industrial heritage, with very interesting new tourist-use experiences [45]. The places are as follows (Figure 1): Industrial colonies on the river Llobregat (Catalonia), industrial colonies on the rivers Ter and Freser (Catalonia), Andorra mining area (Aragon), Sabero Ironworks (Castile and Leon), Madrid slaughterhouse (Madrid), Almadén mining area (Castile-La Mancha), and Rio Tinto mining area (Andalusia).

Figure 1.

Location of the cases analyzed in Spain. 1. Industrial colonies on the river Llobregat; 2. Industrial colonies on the rivers Ter and Freser; 3. Andorra mining area; 4. Sabero Ironworks; 5. Madrid slaughterhouse; 6. Almadén mining area; 7. Rio Tinto mining area. Source: Own elaboration.

2. Methods

Industrial heritage is a broad concept related to the work culture, which includes a series of elements linked to the activities of extraction, transformation, transportation, distribution, and management generated by the economic system of the Industrial Revolution.

These elements are integrated into a given landscape and are defined by a series of architectures, techniques, and practices. Industrial heritage has a multidisciplinary methodology, characterized by the study and revaluation of material and intangible remains as historical evidence of production processes. The various aspects integrated into the concept of industrial heritage require differentiated analysis perspectives because of its various characteristics.

The immersion in the information provided through the review of the scientific literature has made it possible to adapt the information to the characteristics of the object of study in the selected cases. It is a method based on the interpretation of the observation and on the comparison of contents obtained from different sources. A special emphasis has been placed on environmental, landscape (understood the industrial landscape as social construction), architectural, and tourist aspects.

The method is variably adapted to the processes and actors involved in sustainability. Each case studied has its own characteristics, so reality must be interpreted in a concrete way from different elements and relationships. In principle, the representativeness of the study is not the most relevant issue. Although it will not always be possible to generalize the research results in other places, there is the advantage of being able to contrast and expand these results with those obtained in other cases in different geographical contexts.

The interpretation carried out in this research is of a geographical nature and represents a concrete, but significant, perspective of the multidisciplinary approach to such a broad field of study. Special importance has been given to the territorial insertion of the selected elements, their configuration as landmarks of spatial planning and the adaptation of their built features to the current demands for spatial planning. The existence of very different elements, with attributes that are difficult to repeat, requires a specific analysis of cases. This does not prevent the obtaining of general conclusions on the results achieved and the consideration of industrial heritage as an object of territorial desire due to the possibilities offered for landscape and volumetric integration and new uses.

The qualitative and comparative method has aimed to achieve the “interpretation” of a reality related to industrial heritage, rather than prediction. The choice for a qualitative methodology is not accidental or arbitrary and is the result of a deliberate process of searching for understanding and not so much for explanation. The strategy followed has been of an interpretive nature based on the processes existing in each case study, in unique and well-defined territorial contexts. The use of case studies, based on representative examples of industrial heritage, has been widely applied in other research with the aim of providing information on the importance of this heritage, especially relative to the potential for the sustainable development of recovery projects [46].

The qualitative research model applied in the article assumes the main aspects of a scientific structure as they have been exposed by various authors [47,48,49]. It starts from the establishment of hierarchical research objectives at several different levels. These objectives focus the study in a general way and represent the previous step to the necessary review of the scientific literature. The bibliographic review, as recommended by some authors [50], has been carried out in different phases as the research progressed: at first, review of publications on sustainability, tourism, and industrial heritage; subsequently, review of the publications on the selected cases. Two different phases, but necessarily linked to each other.

As already mentioned, the research model has applied a qualitative method based on description, evaluation, and comparison, as well as on trends of change. These aspects have been referred to a series of case studies, selected with sufficiently justified criteria of relevance.

The selection of case studies is a fundamental part of qualitative research [51]. It was decided to follow the representativeness criterion and to choose those examples considered most significant, in terms of both sustainability and recovery and new tourist use. There was a total of seven cases distributed throughout several different regions. Three cases are old mining areas and the other four are elements and factory complexes. The outstanding feature in all of them is the new use projects and the sustainability-related measures applied. Therefore, the study encompasses different places, landscapes, and experiences that provide a perspective that to date has hardly been analyzed for industrial heritage purposes.

Two main criteria were followed in selecting and identifying the case studies: first, intrinsic criteria, which refer to the element’s importance regarding other elements of the same kind. In this case, particular importance is attached to the singularity, representativeness, and integrity of the element. Second, heritage criteria, that is, criteria regarding its historical and social value within a given period and society, its technological or artistic value, and its relationship with the surrounding territory. This last heritage criterion is of undoubted geographical relevance and was of great analytical interest in this research.

Extensive field work has been conducted with exploratory tours on the different sites, making it possible to detect evidences and realities about the research objectives. This task was carried out in different phases between March and October 2019. Direct information was obtained from observation, the preparation of notes, and interviews with some of the managers of the places visited. In this stage, the previous knowledge of each specific site was applied, the results of the projects were verified, some deficiencies, in the form of imbalances, were detected and some possible solutions were identified. For each case analyzed, a field sheet was prepared, with different information records. The photographs were also a documentary sample of great value.

Apart from the bibliography, cartography has also been used to a large extent as a documentary source, together with certain press reports and digital archives. It was also necessary to consult certain plans such as the National Industrial Heritage Plan (PNPI in Spanish; the PNPI was first drafted in 2000 and subsequently revised in 2011, in line with the needs that had been identified, before being partially updated in 2016. Currently, work continues updating the Plan, adding information, documenting assets and expanding the List of Industrial Properties), conservation plans, deindustrialized territory organization plans, environmental and architectural recovery projects, new use project plans, or tourist statistics. This task has provided relevant information.

The method has focused on the characteristics of the projects and their environmental and territorial dimension. The referred Spanish PNPI considers that industrial heritage leaves deep marks on the territory and is an active resource that promotes local and regional sustainable development schemes. One of the key ideas of the document is that the elements of industrial heritage are not isolated items of property, but instead are integrated in their territorial context. This interpretation represents a new, updated, and integrated reading of industrialization’s legacy, of undoubted geographical connotations in the general framework of what one could called territorial culture. The territory, and its aesthetic impacts in the form of landscape, remains longer than the objects and the society that generates them as well as their technical procedures.

This is why restoration and intervention projects must not forget about territory-related aspects. Industrial heritage-related sustainability also involves the original elements maintaining their narrative vitality and formal specificity by integrating the characteristics of the places where they are located. Restoring material remains has become a driving force for economic development in many territories hard hit by factory closures and unemployment. The experience gleaned in those projects shows that one always needs to consider a series of intervention strategies to achieve success and the unavoidable objective of sustainability.

A large part of the method has involved preselecting a series of industrial heritage-related thematic sustainability groups. These groups are a sort of principal study guide about the following: territorial and landscape sustainability (TlS); environmental sustainability (EnS); architectural sustainability (ArS); and tourist and economic sustainability (TeS). In turn, these groups are broken down into a few main criteria for analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Groups and main analysis criteria.

The analysis criteria that have been chosen, in line with the qualitative approach of the method, are not capable of measurement nor are they defined in an operational manner. These criteria allow for the incorporation of new ones at any time and, furthermore, are easy to apply in different patrimonial or spatial contexts.

Each selected site will be analyzed in terms of the most appropriate sustainability cluster according to the characteristics of each case. The assessment possibilities differ due to the variable nature of the examples, but this does not prevent us from stating that all the sites selected offer broad and complementary possibilities of sustainability-based interpretation. As already above-mentioned, the intense observation of the place of each case has provided a description of facts, elements, and interactions between industrial heritage, territory, and society. The case studies necessarily represent a process of obtaining individualized information, framed in a general context of analysis and interpretation in which each case is a fundamental element. This has allowed and facilitated the subsequent obtaining of conclusions and the discussion of results.

3. Results

The heritage of industrialization has been the backbone and driving force in many places. This legacy and the associated cultural landscape must feature as key aspects of territorial planning. This is the first thematic group covered by the research: territorial and landscape sustainability (TIS).

Many factories, located in Catalonia’s hinterland to benefit from the advantages of being far away far from the convulsive social and union demands of Barcelona during the 19th century, represent an extraordinary example of historical industrialization related to the textile sector. This model of industrial implantation radically modified the previous pre-industrial landscape and created factory towns as alternative establishments to the traditional agricultural ones. This is a complex fact in which using water as an alternative to using coal, and the countryside’s low wages, social peace, legal incentives for the occupation of sparsely populated territories, etc. came into play. The main builders of this dense network of factory towns were the local manufacturers, driven by the profits of a booming textile sector, while the public administrations were hardly involved at all. As a result, what one might call industrial fiefdoms emerged, bringing old medieval memories of workers submitting to business and religious power. Indeed, the two most important parts of any colony, apart from the factory, were the owner’s residence (called the “master’s tower”) and the neo-Romanesque or neo-Gothic church [32,52,53].

Industrial sites sprung up from the 1940s onwards as enclaves of activity, housing, and associated services. The building of the colonies and factories not only boosted the economy of the riverside municipalities located in the basins of the rivers Llobregat, Ter, and Freser, but also of other nearby municipalities. The development continued until the textile sector was hit by a crisis in the 1990s. The textile crisis of the second half of the 20th century and the emergence of a thriving tertiary sector ended up turning the colonies into almost exclusively residential centers. However, in all cases, a heritage of great cultural value associated with historical industrialization has been preserved [54].

The most striking feature of the Catalan textile colonies is not precisely their architectural or urban quality, nor the fact that they function differently from the worker colonies in other parts of Spain and Europe, but rather their abundance, density, and formal homogeneity (Figure 2). These three main features make the colonies a unique phenomenon that defines extensive areas and landscapes in Catalonia’s hinterland [55]. This is why Llobregat’s industrial colonies feature on the PNPI’s List of Industrial Properties and, together with the Ter–Freser’s colonies, are one of the main heritage tourist attractions in Catalonia’s hinterland.

Figure 2.

El Prat industrial colony (Barcelona). Source: Own elaboration.

These residential and industrial complexes are urban sites and as such have been subject to territorial planning under the planning instrument known as the “urban master plan” (PDU in Spanish). In the case of the industrial colonies on the Llobregat River (province of Barcelona), the plan was approved in 2007 and affects a total of nine municipalities. The PDU for the Ter and Freser Rivers (provinces of Gerona and Barcelona, respectively) was approved in 2010, with very similar characteristics to the previous one, and in this case affected twenty municipalities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Territorial and landscape planning characteristics.

The two PDUs were drawn up to resolve the major imbalances existing in their respective areas of intervention. The nature of this urban planning tool, on a scale halfway between urban and territorial planning and a well-defined unitary geographic area, make it a fundamental tool for understanding the river-industrial landscape in an integrated manner and regulating each working-class town in detail [56,57].

The two PDUs have led to a comprehensive territorial and landscape planning approach, providing a coherent and unitary perspective to the space defined in the respective plans. From the territorial viewpoint, both PDUs have managed to protect urban-industrial heritage sites and natural river environments. The general, sustainability-based criteria applied have improved the natural spaces, the urban structure of the colonies, and the communication routes connecting the colonies and their respective municipalities. From a heritage perspective, the plans have comprehensively protected the industrial heritage of the industrialization-related cultural landscape and colonies, with actions to consolidate the old factories [58].

Both PDUs understand that tourism is a key tool in projecting the territory as a single unit. The sustainable revaluation of tourist resources has been one of the main objectives pursued by the planning. This objective can now be considered to have been achieved because both heritage axes issues are one of the most important cultural and natural resources in the interior of Catalonia’s hinterland. The historical uniqueness of this dispersed, linear industrialization has managed to attract a significant number of annual visitors, favored by its proximity to the city of Barcelona, and to disseminate the values associated with an industrial location that marked the economic and social development of many municipalities and counties for one and a half centuries.

In any case, there is still no intense tourist promotion of the industrial colonies and associated textile factories. The creation of conditioned spaces for visits is insufficient. The general objectives of intervention have prioritized communication infrastructures, social facilities, and urban consolidation of the neighborhoods. These aspects are very important for territorial and landscape sustainability, but the specific characteristics of these former production spaces make both the promotion of tourism and the intelligent management of resources unavoidable factors.

The Llobregat and Ter–Freser PDUs are two excellent examples of the scope that the development of industrial heritage and related spaces should have, with integrated and pragmatic proposals from the territorial, landscape, and urban point of view. Both plans have managed to organize a complex environment affected from the start by numerous shortcomings such as rundown factory buildings, unoccupied dwellings, abandoned spaces, and environmentally deteriorated riverbanks. There has been little public involvement, because most of the land and buildings are privately owned. Above all, the public authorities’ role has been to oversee and protect private operators’ investments, aimed at resolving each colony’s structural deficits.

The complete restoration of the environment and the renaturation of the landscape are the main criteria for analysis in the second thematic group: environmental sustainability (EnS). The impact on large areas, especially mining areas, as a result of the intense mining of natural resources, is a large-scale environmental problem. The mining areas of Andorra (Aragon) and Almadén (Castile-La Mancha) are two examples of the environmental damage caused by prolonged mining. In both cases, mining left deep and lasting marks that were hardly compatible with the criteria of environmental and aesthetic sustainability.

To start with, the situation was very chaotic, marked by environmental degradation and the predominance of large sinkholes, artificial hills made of slag deposits and surplus rocks, steep slopes, mounds of richly colored earth, and the absence of vegetation. This desolating panorama entailed approving large-scale environmental restoration projects capable of creating new landscapes and environments of aesthetic and environmental quality, applying the strictest sustainability criteria. The impacts of the past, and the features of what one could call “black landscapes”, have created opportunities for the future through environmental engineering operations that have called for large doses of technical wisdom and economic solvency.

In the Andorra mining area, coal mining dates to the 18th century, although it took a long time to develop due to its distance from the main consumers. The building of the railway and the connection with Zaragoza in the 20th century boosted mineral production and local industrialization. Open-pit mining began in 1981 at the Alloza mine, and steadily replaced the previous underground mining. Production increased and costs were reduced, with environmental impacts on a previously unknown scale. The European regulations approved from 1990 onwards to streamline the coal mining industry triggered a decline in mining in the region and the last mines were closed in 2012.

Before it closed in 2012, the mine’s owner, ENDESA, had already begun its environmental restoration, working in phases as mining operations progressed and mining-free areas were freed up. The aim was to strike a balance between using the remaining coal and restoring the environment sustainably. The restoration work was carried out on a group of four open-cast mines and a surface area of 865 ha. The environmental objective was to minimize, as far as possible, the artificial and poorly integrated aesthetics of the slag heaps in the surrounding landscape. A decision was made to use the newly created areas in new ways by planting cereal crops, fruit trees, olive trees and vineyards as well as other tree and shrub species. In addition, 38 ha of wetlands were created in the abandoned mine shafts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Environmental characteristics.

One of the key features of the restored area is that there is an environmental interpretation center that explains the work that used to be done in the old mines. All along the seven-kilometer guided tour are several viewpoints from which to contemplate the scope and the result of the rehabilitation work carried out. It is one of the best examples of combining environmental restoration and tourism in Spain and a point of reference in Europe. The visits present more modest data than in other industrial heritage sites, but they express a continuous increase that has gone from 3250 in 2009 to 3400 in 2012, and slightly above 4000 in 2019.

Another example of landscape renaturation after a mine closed is Almadén, a mine that was the world’s largest cinnabar deposit. Open since Roman times, the mine’s heyday came in the 16th century when quicksilver became essential for amalgamating the huge amounts of silver brought from America. After declining in the 17th century, mining production increased again during the 18th and 19th centuries, with levels of production peaking in the mid-20th century. The mine finally closed in 2003. The mining complex’s heritage value led to it being protected as a Site of Cultural Interest in 1992. In 2007, the mines were declared as a Historic Site by the regional government of Castile-La Mancha and in 2012, they were included on the UNESCO World Heritage list. The total area currently protected is 104 ha. According to the information provided by the technical managers of the mining park, the number of tourists in recent years has gone from 12,182 in 2012 to 10,500 in 2014 and 15,013 in 2018.

The idea of turning the area into one of the country’s top cultural and tourist sites is why it had to be regenerated in order to reduce the environmental impacts. The enormous quantities of tailings from mining operations and the slag from metallurgical processes built up over time in the San Teodoro slag heap, which occupied an area of nearly 10 ha and was a size equivalent to 3.5 million tons of hazardous materials, due to its high mercury content. In 2004, the authorities drew up the renaturation project and decided to encapsulate the slag heap to ensure it remained stable and waterproof. At the same time, they decided to make the existing slopes gentler so that the slag heap’s artificial forms would be more in harmony with the area’s natural slopes, reducing the initial slope of 36° to the current 25° (Figure 3). The land cover has been restored to merge the structures better into the landscape using autochthonous, fast-growing species to reduce erosion as soon as possible.

Figure 3.

Waste rock of the Almadén mining area in the rehabilitation phase (2007). Source: Paisajes Españoles.

The environmental restoration of Andorra and Almadén mining areas have been more important than the conservation of their respective constructed heritage. The main goals have been to renaturalize the landscape and create new post-industrial scenarios that appeal to visitors. The restoration work has been on a very large scale, especially in the Andorra mining area, where the mines were opencast. The regeneration dynamics have been technically and scientifically very rigorous and has provided environmental certainty by mitigating the profound alterations to the natural environment.

The architectures and built elements form part of the third thematic group: architectural sustainability (ArS). Old factories offer great opportunities for restoring them for new uses. Their solid materials and structures, the open spaces or the excellent lighting conditions and formal layout are advantages recognized by any restoration project [59]. Industrial architecture is functional, rational, and adaptable, features that outweigh any aesthetic virtue when it comes to reutilizing its spaces. However, cultural and historical values also matter because they represent the testimony of a productive and technical past.

On account of the large variety of industrial constructions, selective conservation following cultural, architectural, or practical interest-based criteria was required. Reusing these buildings avoids unnecessary demolition and demolition costs, reduces material and energy consumption, preserves the memory of the places, and revitalizes the city or rural spaces by using them in a different way to their original purpose [60]. These are basic principles of industrial heritage-related sustainability that must be assessed as large-scale recycling.

Any course of action must underscore the productive origin of the building and reinforce the architectural features, which include ties to a landscape, a territory, and a social environment. In this respect, there are two outstandingly important examples of sustainable conservation of industrial architecture: Madrid’s municipal slaughterhouse and the San Blas Ironworks in Sabero (province of Leon).

Madrid’s old slaughterhouse is a very interesting group of buildings designed in an aesthetically uniform manner and an excellent example of the city’s industrial architecture. It was designed in 1908 in the neo-Mudejar style, so characteristic of the period, on a 16-hectare plot of land in a then unpopulated area of the city. The building works lasted from 1910 to 1925 and the facilities remained in use until 1996.

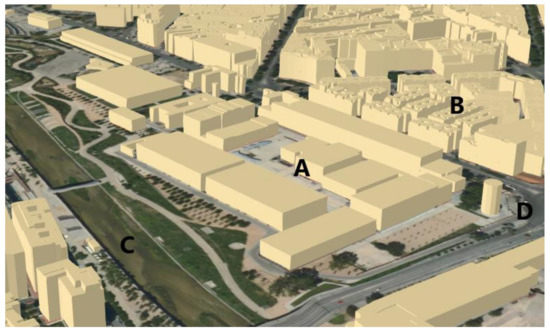

All the buildings were grouped in five sectors: production, management and administration, livestock market, slaughterhouse, and sanitation section, following a pattern of isolated pavilions separated by streets and presided over by the administration building (known as the Casa del Reloj) as the main axis of the ensemble. The complex is characterized by constructive utilitarianism, but without renouncing the almost handcrafted beauty provided using traditional and indigenous materials such as bricks and tiles. Furthermore, the combination of all this with some modern features such as rationality, simplicity, and functionality, heralded the architectural renovation of the 1920s (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Main façade of the Madrid slaughterhouse. Project by the architect Luis Bellido. Source: Official College of Architects of Madrid (COAM).

Madrid’s 1997 General Urban Development Plan (PGOU) included the old slaughterhouse in the catalogue of protected buildings, and this affected its whole perimeter and the entire set of buildings. The Plan classified it as a space for collective services, under the unique amenities’ category. In 2002, the City Council passed the Special Plan for intervention, architectural adaptation, and urban-environmental control of uses, with the idea of creating a large cultural venue in the city. The most important objectives of the Plan were the following: consolidation and restructuring of the buildings; distribution of the building meters; remodeling of free spaces; adoption of general criteria, based on the quality of the intervention; and preservation of a group of unique buildings in a historic industrialization area in Madrid, subject to strong speculative pressures. The new cultural space, known as Matadero Madrid, was finally opened in 2007. The restoration respected the original, structural, and morphological constructive characteristics, and the different cultural uses have been adapted to the existing spaces (Table 4) (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Architectural intervention characteristics.

Figure 5.

Madrid slaughterhouse: (A) Buildings of the old slaughterhouse; (B) Pico del Pañuelo Workers’ Colony; (C) Manzanares river; (D) Legazpi Square. Source: Geoportal of the Madrid City Council and own elaboration.

Opposite the slaughterhouse is the Pico del Pañuelo workers’ colony, a neighborhood of very similar houses built between 1927 and 1930 for the workers of the slaughterhouse’ workers. It is an excellent example of an urban industrial colony functionally and spatially linked to the large slaughterhouse complex. It is a planned neighborhood of 74 four-story multi-family buildings with more than 1500 homes for rent and good hygienic conditions for the predominant criteria of the time. Five different types of buildings were designed on the block to provide a solution to the arrangement of the triangular plot.

The powerful architectural image that the slaughterhouse still transmits as an industrial element is not projected sufficiently on the surrounding urban space. This space was strongly specialized in industrial activity. It is necessary, therefore, to recover the role played by this urban function, which has been intensively developed over decades, and present it as a factor to stimulate and promote landscape and culture.

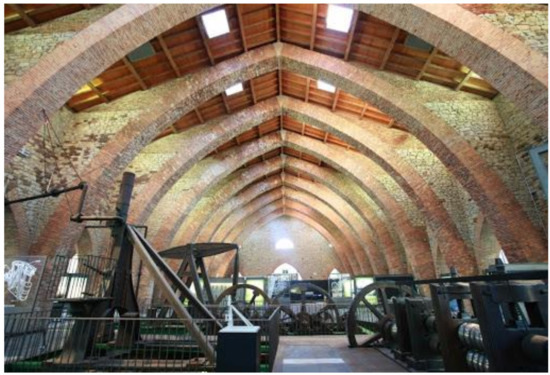

The San Blas Ironworks, in the town of Sabero in Leon, was an early steelworks built in 1846. The following year, the first blast furnace began operating and the second in 1854. These two blast furnaces were the first coking coal furnaces in Spain, and there were also several steam engines for rolling iron. This initiative is surprising because it is in a very hard-to-reach area close to the Cantabrian Mountains. A group of entrepreneurs got together and, with the large amount of mineral resources, managed to embark on an innovative industrial project, yet one that was very limited in time. The iron and steel activities came to an end in 1862 due to the transportation difficulties and the lack of financial resources. Mining operations in the region continued until the mines were finally closed in 1991.

The forge and laminating building consist of a large central nave held up by pointed arches of medieval inspiration and two lateral naves with semi-circular arches. The dimensions create an open space in which the main features are its constructive and aesthetic characteristics (Figure 6). This workshop now houses an iron and steel industry and mining museum that was opened in 2008, after it was restored, and significant parts of its original function were recovered. The Castile and Leon regional government had it restored to provide a cultural and tourist resource in an area that has been hit very hard by the mining industry crisis. The restoration work focused on the main building as a point of reference, and on the territory as a general framework for the development of mining in the Sabero Valley [61]. Architecture and territory are the interpretative keys to the region’s tourist and economic revival, based on the culture of industrialization and its national projection as a heritage destination. According to information provided by the museum managers, the number of tourists has registered a constant increase in recent years, going from 20,642 in 2012 to 31,882 in 2015, and 37,118 in 2019.

Figure 6.

San Blas Ironworks. Source: City Council of Sabero (León).

It is necessary to promote the use of new information and communication technologies (ICT) to more intensely promote the cultural values and the tourist possibilities of this element of the Spanish industrial heritage. Some fundamental objectives have to be achieved: configure the place as a smart tourist destination and create a website with more digital resources to provide more information to the visitor: a smart event calendar log, availability of weather information, access to multilingual information, possibility of using mobile applications, access to PDF digital leaflets, or 3D models from photographs, etc. The results could offer a more innovative profile of the place and connect visitors, visited spaces, and available resources in a more intense way. The interaction of these three factors with the surrounding territory (of importance in the case of Sabero) would promote a new competitive digital capacity and would give a more intelligent tourist projection of the place. It is also important to highlight that local authorities, in the opinion of the experts and managers consulted, should become more involved in promoting the destination and provide the necessary financial means to increase digital processes.

Promoting industrial heritage for tourist purposes is one of the best reuse options. Many museums, interpretation centers, cultural parks, and ecomuseums have been set up. Industrial heritage is an important cultural resource in many areas far from traditional tourist destinations, and as such offers certain local development opportunities. Money has to be invested not only in the physical restoration of buildings or the renaturation of the natural environment, but also in promoting a set of synergies that create collaborative organizational structures; involve the local business fabric; interact with the local community; and build a technological model for promoting tourism based on intelligent information [38]. This is what is known as industrial heritage tourism and, as a thematic analysis group, as tourism and economic sustainability (TeS).

The Rio Tinto heritage, in the province of Huelva, represents the historical evolution of one of Europe’s most important mining sites. The subsoil has been mined non-stop for more than 5000 years, giving rise to a unique cultural landscape and a profoundly transformation of the natural environment. Mining operations peaked from 1873 onwards, when a British consortium bought the mines and introduced large-scale mining. The result was the emergence of open-cast mines, piles of tailings in large slag heaps, workshops, chimneys, planned workers’ quarters, residential areas for British managers, mining railways, etc. In 1954, the mines were bought back by the Spanish state, and then closed in 2001 as they had become unprofitable (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Rio Tinto mining area. Source: Own elaboration.

The heritage value of the buildings and the transformed landscape led to the area being protected in 2005 as a Site of Cultural Interest, in the Historic Site category. In 2007, this category was revised under the new Andalusian Historic Heritage Law and it became a Heritage Zone [20]. Promoting tourism was another course of action for regional and local administrations with the goal of boosting the area’s economy, which was hard hit by unemployment after the mines closed. The main tourist attraction emerged in 1992 when the Rio Tinto Mining Park was opened. Ever since, the number of visitors has grown from year to year, and it has become Spain’s top industrial heritage tourist destination: 11,366 visitors in 1992; 42,138 in 2002; 62,092 in 2012; and 96,975 in 2019. The data has been provided by the managers of the Rio Tinto Mining Park.

The opening of the Rio Tinto Mining Park has boosted tourism and created a new source of employment in several phases. The first phase involved restoring the different elements and assets that can be visited, and the Rio Tinto Foundation—created in 1987 at the proposal of the company that owned the mines at the time (Rio Tinto Minera, S.A.) as a cultural foundation for the conservation of heritage and the environment. Its objectives also included the economic promotion of the area with the creation of the Mining Park for tourism purposes—played an active part in this by organizing several professional training programs, facilitating the creation of an indeterminate number of jobs, and bringing significant social value to the project. The second phase was to adapt the Mining Park’s main elements and sites for tourists: the mining museum, house no. 21 of the Bella Vista neighborhood, the tourist railway. and the Peña del Hierro mine.

The museum is now located in a building that used to be a mining hospital. It was opened in 1927 and stayed open until 1983. Formally, it has Victorian features due to the influence of the British architect in charge of the project. The museum was inaugurated in 1992 with a total surface area of 2340 m2, of which 1690 m2 has been given over to the permanent exhibition area.

In 2005, house no. 21 of Bella Vista was opened to the public. This district became home to the British technicians after Rio Tinto Co. Ltd. bought the mines in 1873. This house, together with the rest of the district, was built in 1883. Ever since it was bought in 1996 by the Rio Tinto Foundation, it has been refurbished to turn it into a tourist attraction due to the interest represented by its original Victorian architecture and the furniture of the time. The total exhibition surface is 540 m2. In 2009, a working-class home in the San Carlos district was opened to the public, providing a new interpretation area that contrasts with the previous one.

The tourist railway runs through a sector of the mining basin and uses the original route that served to transport the ore from Rio Tinto to the port of Huelva. It was opened in 1875 and stayed open until 1984. Reusing it for tourism entailed restoring the rolling stock (several steam, diesel, and electric locomotives as well as wagons) and the railway infrastructure (tracks, signs, stations, and unstaffed stations). After all the restoration work was completed, the Park opened to tourists in 1994.

The last stop for visitors is the Peña del Hierro mine. Restoration work began in 1996 with the general cleaning of the site, removal of debris, adaptation of access roads, and design of the tour route with all the necessary safety guarantees. In 2004, the mine was finally opened for tourism.

These actions represent a benchmark of industrial heritage sustainability in Spain, because they have guaranteed the success of a major tourist venture in which the digital techniques used to manage and promote the site have played a decisive role. Websites are always an important publicity medium. The Mining Park’s website is attractively designed and features a wide range of different content, although for the moment only in Spanish, even though 20% of its visitors are foreigners. It offers different information links and several multimedia tools, yet lacks relevant aspects such as a smart event calendar, weather information, mobile device apps, and the possibility of writing online reviews. Further digital content should be added to promote tourism even more and so guarantee its cultural projection (Table 5, Figure 8).

Table 5.

Tourist and economic intervention characteristics.

Figure 8.

Rio Tinto mining area. Source: Google Earth.

When interviewed, the Mining Park’s managers agreed that the technology available today offered great opportunities to promote and enhance tourist destinations. They saw applying technology as a good management measure, although they also pointed out that it was sometimes complex and costly in economic terms. They received little help or cooperation from the different public administrations, and technological advancements were very limited or took too long, even though the Mining Park had a specific strategy to boost smart tourism.

The investments made for the patrimonial recovery in the mining area have been numerous. It has been possible to achieve a very powerful tourist image in the specific field of industrial heritage, with important visitor numbers (although with quite a margin of increase). However, the initial prospects for local job creation (as in the mining areas of Almadén and Andorra) have not been fully achieved.

An important source of employment could be the general application of information and communication technologies for the management and promotion of industrial heritage tourism at the local level. According to the managers consulted, the current technological scenario offers interesting opportunities to configure a fully intelligent tourist destination. They consider that new technologies provide greater efficiency and reduce costs in the tourist destination, but they also comment that there is not an adequate level of digital collaboration with the different public administrations and between them and private companies. Collaboration is essential to promote the destination as a place of industrial heritage and increase job opportunities in the municipality.

The results generated by mining tourism are insufficient. Complementary tourism infrastructure and accommodation facilities are few and far between, as are catering establishments. The private sector has failed to back the Rio Tinto Foundation’s tourism initiative and has been quite unenterprising in developing tourist support services. Anyhow, tourism-based endogenous development activities do not always meet expectations, even with the help of some European funding programs. It is by no means easy to revert the prolonged decline, as shown by the steady demographic decline of nearly 40% between 1991 and 2019. There are approximately 300 direct and indirect tourism-related jobs, a significant figure if one considers the region’s high unemployment rate, yet far more jobs could have been created. Efforts have been made to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of an enormous item of heritage, yet what was needed was a more ambitious investment program capable of overcoming the economic deterioration and serious environmental problems after decades of neglect [62].

As a result of these flaws/shortcomings, the project to set up a geopark—a territory with an exceptional geological heritage, which is the main basis for carrying out a sustainable development strategy based on protection, dissemination and tourism—in the area, which was submitted in 2010, failed to pass the European Geoparks Network application process. It failed for several main reasons: first, the River Tinto’s river basin still has serious environmental pollution problems due to the presence of heavy minerals, derived from natural processes and the closed-down mines, and water toxicity issues, and second, the area has no specific management body independent of the promoting entities (regional government of Andalusia and Rio Tinto Foundation). These reasons clash with the required levels of environmental, tourist, and economic sustainability that the future geopark should have.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Industrial heritage tourism is an example of a tourist activity that is balanced in the local economy and society. The applied model of heritage conservation, responsible use of resources, and territorial dynamization generates a few conflicts in destinations. This is also influenced by the low tourism carrying capacity. Industrial heritage tourism, therefore, is a very appropriate bet in relation to the objectives of sustainability.

This research focuses on seven specific cases from Spain. They are representative of the resilience and sustainability of industrial heritage. Although they correspond to territories with their own competences in matters of cultural heritage, with different regulations for evaluation and application, they present similar patterns of compliance with the objectives of sustainability, new use, and spatial planning.

The use of a series of simple and direct variables, grouped into different thematic blocks associated with the sustainability of industrial heritage, confirms that it constitutes a valid and easily applicable model. It is a model focused on the main qualitative aspects of sustainability in heritage environments of industrialization. Therefore, it can be applied in other different heritage places and reach an adequate level of characterization and interpretation.

The aspects analyzed in this research on industrial heritage tourism are general in themselves and respond to objectives and challenges shared by other tourism sectors. It should also be noted that they are applicable to other economic activities because they contribute to building a more rational, resilient, and sustainable scenario in relation to the environment and the use of resources, regardless of the origin and characteristics of the resources.

The interpretation of the information allows us to achieve the following conclusions: (a) The case studies present an adequate level of sustainability in relation to the conservation of the landscape and the available resources; (b) Architectures play an important role as identity landmarks within the territory; (c) The sustainable recovery of buildings and the environment is an indispensable attraction as a resource for tourism; (d) Sustainability is an initial intervention strategy for projects and a hallmark for local communities; and (e) Tourism promotion is based on the construction of a technological model that allows intelligent information.

The case studies are relatively recent tourism interventions in which strict sustainability criteria have been applied through inclusive and sustainable proposals and rational and responsible management models. In any case, some imbalances or deficiencies can be pointed out below, which must necessarily be considered: (a) The projects present a high specialization that delve into sustainability in a concrete way, according to the characteristics of the place and the existing resources; (b) Except for some specific cases (Rio Tinto and Almadén, for example), the places are not intensely promoted as cultural destinations, nor do they affect the value of the environment as a cultural landscape of industrialization; (c) As in the case of Madrid’s old slaughterhouse, the image of industrial heritage is not projected enough to structure and energize the territory; (d) Information and communication technologies are present in the management and promotion of destinations, but there is still a wide margin for greater technological implementation (as in the case of the Sabero Ironworks), and achieving the consideration of fully intelligent destinations; (e) Tourism carrying capacity continues to be excessively low in some cases (e.g., industrial colonies on the rivers Llobregat, Ter, and Freser, Andorra mining area), which reduces the possibilities for economic revitalization and innovation; and (f) The absence of collaborative networks between the cases analyzed prevents sharing experiences and solutions to global remains.

All these reasons allow for the comment that sustainability can be improved by adopting a series of additional measures. They are as follows: (a) Pursue new opportunities for the future and promote creative and imaginative initiatives to create recognized quality tourism; (b) Further reinforce the cultural image of industrial heritage destinations as a measure to maintain the collective identity of local communities; (c) Intensively coordinate the action of the different agents involved, both public and private, to guarantee the continued success of the destinations and the promotion of community participation; (d) Increase the role of public administrations, especially at the regional and state level, and coordination with local entities; (e) Increase the management and digital promotion of destinations, promoting the interaction with tourists through information and communication technologies; (f) Reinforce shared experiences between destinations, in order to guarantee a better future for sustainable industrial heritage tourism; and (g) Promote places as fundamental elements of the planning of the territory in which they are located, or the applied measures of a cultural, environmental, and socioeconomic nature.

The article analyzes, from a qualitative method, a subject of great geographic relevance: the relationship between industrial heritage and sustainability. The information obtained from different sources was interpreted and results were obtained from the observation and comparison of contents. The fact of being a descriptive and interpretive study, based on the contextualization of the data, limits, in a sense, the general application of results. The legacy of industrialization is very broad and any study on this subject requires narrowing down a part of reality by selecting case studies. The selected cases have been established according to criteria that pursue, in any case, territorial and thematic representation. They are small-scale cases that represent themselves, whose operational results are difficult to transfer to other places. This is a significant limitation, but it does not prevent us from recognizing the value of the results achieved and their contribution to the general knowledge of the sustainable use of industrial heritage.

The analysis model can be transferred to other cases in Spain or other countries in Europe. National laws are harmonized in relation to strict compliance with the protection, rehabilitation, use, and management of heritage. This is what the real planning of heritage and its resources, historical values and built and human environments means on a tangible and intangible level [63]. It is the approach that some authors call “adaptive reuse”, with different decision criteria within the framework of economically profitable alternatives [64]. It can be said that there are no borders in this thematic field. The interventions present very similar models of landscape, architectural, and social rationality based on medium- and long-term strategic orientations. Not by chance, the World Heritage Committee declared in 2002 that heritage is an instrument for the sustainable development of all societies [65].

Industrial heritage, as cultural heritage, must play a fundamental role in tourism development and territorial cohesion. Its conservation and responsible use provide ample opportunities for the construction of resilient and sustainable spaces. Aspects such as those analyzed in this research (territory, landscape, environment, architecture, tourism, and economy) are basic thematic axes for setting the old mines and industries in the general context of sustainability. Proof of the interest that industrial heritage arouses in this regard is the organization of some events such as the International Conference on Industrial Heritage INCUNA 2017, held in the Spanish city of Gijón, where the result of this Conference was the publication of the book entitled Industrial Heritage in the Context of Sustainability (Editorial CICEES, Gijón, Spain, p. 516).

The use and recycling of industrial buildings (processes that seek to convert the remains of abandoned buildings into new spaces adapted to later uses) are a sustainable practice per se that checks the uncontrolled destruction of numerous heritage remains over decades. Architectural treatment of industrial heritage is complex due to the inherent magnitude and complexity, the territorial, landscape, social, and economic challenges that must be handled and, last but not least, due to the specific nature of the production-related buildings and areas.

As mentioned earlier, production architectures are milestones and points of references of landscapes. The rounded forms, the volume effects, and the solid materials provide outstanding advantages for reuse. In addition, they are functional and adaptable structures, and are both aesthetically and technically highly representative as a reminder of an industrial past.

The projects have set the intervention proposals in the framework of the existing constructions. The Matadero in Madrid is a fine example of great industrial architecture, but there are many more inside and outside Spain. The aim has been to fully preserve the cultural values of the built elements within the landscape and to interpret them in their urban and territorial context [55]. In any case, not everything built can be preserved and used by tourism due to the material abundance of industrial property. The solution is selective restoration, with territorial planning and landscape integration criteria playing a key role [61].

The renaturation of former production areas is another sustainable practice, particularly significant for the general objective of introducing tourist uses into mining areas. Mining operations create environmentally degraded spaces that survive after the mines close. Now, they must be restored under current legislation, with far-reaching measures and the emergence of new landscapes with strict environmental sustainability criteria. All the results are spectacular, as has been seen in the Almadén and Andorra mining areas, due to the magnitude of the areas affected and the technical complexity required.

Little research has been conducted into industrial heritage tourism in relation to sustainable development [5,21]. Obtaining more resilient and inclusive environments necessarily involves searching for sustainable economic alternatives and the appropriate use of heritage resources [17]. Industrialization heritage facilitates higher levels of local development, and strengthens planning to increase economic, social, and environmental ties [66]. Integrating industrial heritage in sustainable development programs is very important for two main reasons or objectives: the efficient use of resources by tourism and the generation of local employment [16,18]. Whatever the case, reusing industrial heritage to create new jobs can be hampered unless it comes with a serious investment promotion and stimulation program.

The sustainable and resilient assessment model of industrial heritage is necessarily linked to the achievement of an enough level of financing for rehabilitation and new use programs. In many cases, it is difficult to achieve this due to the lack of public or private investors including the owners of the conserved elements. Only increasing awareness of the value that industrial heritage represents as a whole, fundamentally through its most prominent elements, can generate the necessary investments that allow the implementation of projects, adopt sustainable management and promotion measures, disseminate the values associated with the inheritance of industrialization, and the necessary extensive local population participation in decision-making.

This heritage is sufficiently important to be considered as a resource capable of promoting specialized tourism that falls in line with sustainable management guidelines [67,68]. There is an unquestionable economic side to new tourist uses, but they must not be interpreted independently of social considerations, because industrial heritage reinforces a place’s identity and the collective imagination. This explains why, in most cases, reuse begins with the efforts of the population and local authorities to ensure that resources are preserved actively and used sustainably [60,69].

The studies carried out to date show that industrialization heritage transcends exclusively cultural aesthetic or testimonial aspects [10,11]. This cross-cutting heritage serves to shape the territory where it is located, both from a spatial and temporal point of view [19,70]. That is why industrial heritage must be regarded comprehensively, going beyond purely iconic-related ideas, as has occurred in past decades, and think more profoundly about the elements and planned uses so that this heritage can be tied into the processes of building resilient territories.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Research Challenges R&D&i Project entitled “Vulnerability, resilience, and strategies for the reuse of heritage in deindustrialized spaces”. Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, 2018 call. Reference: RTI2018-095014-B-I00. Lead Researcher: Paz Benito del Pozo, University of León.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Luca, D. Sustainable Cultural Heritage Planning and Management of Overtourism in Art Cities: Lessons from Atlas World Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J. ¿Paisajes culturales, consecuencia de la postmodernidad? In Proceedings of the II Seminari Internacional Sobre Paisatge, Barcelona, Spain, 21–23 October 2004; Consorci Universitat Internacional Menéndez Pelayo de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.R.H.; Biger, G. (Eds.) Ideology and Landscape in Historical Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, N. El lugar del paisaje en la Geografía moderna. Estud. Geográficos 2010, 71, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, C.J. Sostenibilidad y turismo en los paisajes culturales de la industrialización. Arbor. Cienc. Pensam. Y Cult. 2017, 193, a400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Merode, E.; Smeets, R.; Westrik, C. (Eds.) Linking Universal and Local Values: Managing a Sustainable Future for World Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sttot, P. Industrial Heritage and the World Heritage Convention. In Industrial Heritage Re-tooled. The TICCIH guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Douet, J., Ed.; Carnegie Publishing Ltd./The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH): Lancaster, UK, 2012; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Oevermann, H.; Mieg, H.A. (Eds.) Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation: Clash of Discourses; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cossons, N. Why preserve the Industrial Heritage? In Industrial Heritage Re-tooled. The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Douet, J., Ed.; Carnegie Publishing Ltd./The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH): Lancaster, UK, 2012; pp. 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, H. What does the Industrial Revolution signify? In Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled. The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Douet, J., Ed.; Carnegie Publishing Ltd./The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH): Lancaster, UK, 2012; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. Industrial Heritage: A Nexus for Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, I. Identifying industrial landscapes. In Industrial Heritage Re-tooled. The TICCIH guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Douet, J., Ed.; Carnegie Publishing Ltd./The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH): Lancaster, UK, 2012; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and Sustainable Development. Exploring the Theoretical Divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. Exploring the sustainability of mining heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Palacios, A.J.; Hidalgo, C. La valorización turística del patrimonio minero en entornos rurales desfavorecidos. Actores y experiencias. Cuad. De Tur. 2008, 22, 231–260. [Google Scholar]

- Vahí, A. Patrimonio industrial como recurso para un turismo sostenible: La cuenca del Guadalfeo (Granada). Cuad. Geográficos 2010, 46, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, A.M.; López, T.J.; Millán, G. El turismo industrial minero como motor de desarrollo en áreas geográficas en declive. Un estudio de caso. Estud. Y Perspect. 2010, 19, 382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, P.; Alonso, P. Industrial heritage and place identity in Spain: From monuments to landscapes. Geogr. Rev. 2012, 102, 446–464. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.J. Environmental Recovery of Abandoned Mining Areas in Spain: Sustainability and New Landscapes in Some Case Studies. J. Sustain. Res. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, C.J. Landscape as Digital Content and a Smart Tourism Resource in the Mining Area of Cartagena-La Unión (Spain). Land 2020, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccossis, H. Tourism and sustainability: Perspectives and implications. In Sustainable Tourism? European Experiences; Priestley, G.K., Edwards, J.A., Coccossis, H., Eds.; CAB International: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Claver, J.; García-Domínguez, A.; Sebastián, M.A. Multicriteria Decision Tool for Sustainable Reuse of Industrial Heritage into Its Urban and Social Environment. Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, M.N.; Petrović, M. Changes in Traditional Activities of Industrial Area toward Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver, J.; García-Domínguez, A.; Sebastián, M.A. Decision-Making Methodologies for Reuse of Industrial Assets. Complexity 2018, 2018, 4070496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Exploring Critical Variables that Affect the Policy Risk Level of Industrial Heritage Projects in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, L. Toward a Smart Sustainable Development of Port Cities/Areas: The Role of the Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misirlisoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, C.; Lazzari, G.; Rubino, I. Values, Memory, and the Role of Exploratory Methods for Policy-Design Processes and the Sustainable Redevelopment of Waterfront Contexts: The Case of Officine Piaggio (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrud, S.; Ready, R.C. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Applying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments, and Artifacts; Edwar Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grazuleviciute, I. Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 3, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A.; Llurdés, J.A. Mines and quarries. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 41–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Munday, M. Blaenavon and United Nations World Heritage Site Status: Is Conservation of Industrial Heritage a Road to Local Economic Development? Reg. Stud. 2001, 35, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial heritage tourism and regional restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambron, P. Patrimoine Industriel et Développement Local; Éditions Jean Delaville: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, L.; Parra, C. Paisajes culturales: El parque patrimonial como instrumento de revalorización y revitalización del territorio. Teoría 2004, 13, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, P. Territorio, paisaje y herencia industrial: Debates y acciones en el contexto europeo. Doc. D’Anàlisi Geogràfica 2012, 58, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. A life cycle model of industrial heritage development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.J. Application of Digital Techniques in Industrial Heritage Areas and Building Efficient Management Models: Some Case Studies in Spain. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.J. El patrimonio industrial en España: Análisis turístico y significado territorial de algunos proyectos de recuperación. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2010, 53, 239–266. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A.; Leask, A.; Reid, E. Engaging residents as stakeholders of the visitor attraction. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, M.P.; Cueto, G.J. 100 Elementos del Patrimonio Industrial en España; Editorial CICEES/Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de España: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic, M.; Drobnjak, B.; Kuletin Culafic, I. The Possibilities of Preservation, Regeneration and Presentation of Industrial Heritage: The Case of Old Mint “A.D.” on Belgrade Riverfront. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.J. Methods of Social Research; Harcourt College Publishers: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walliman, N. Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]