Abstract

The feasibility of exploiting secondary raw materials from marine food-chains as a source of molecules of nutritional interest, to create high-value food products and to meet nutritional challenges, is described in this report. A reduction in food waste is urgent as many sectors of the food industry damage the environment by depleting resources and by generating waste that must be treated. The project herein described, deals with the recovery of natural molecules, omega-3 fatty acids (EPA, DHA) and of α-tocopherol, from fish processing by-products. This would promote the sustainable development of new food products for human nutrition, as well as nutraceuticals. The growing awareness of increasing omega-3 fatty acids intake, has focused attention on the importance of fish as a natural source of these molecules in the diet. Therefore, a study on the concentration of these bioactive compounds in such matrices, as well as new green methodologies for their recovery, are necessary. This would represent an example of a circular economy process applied to the seafood value chain. Fish processing by-products, so far considered as waste, can hopefully be reutilized as active ingredients into food products of high added-value, thus maximizing the sustainability of fish production.

Keywords:

fishery waste; omega-3 fatty acids; EPA; DHA; α-tocopherol; nutrition; sustainable production 1. Introduction

Food production is increasingly considered to have a strong environmental impact, including in this context, concepts such as the loss of biodiversity, the consumption of fresh water, CO2 production and chemical pollution. These factors, along with the decrease in available land, population growth and food accessibility, have a strong impact on food production and food security [1]. The current food system has also been regarded as the primary cause of the large production of food waste, nutrient loss, the use of potentially dangerous non-natural substances in food products and the application of invasive technologies along the food chain. All these actions strongly contribute to both environment degradation and an irrational food production, which leads to the consumption of unhealthy diets. Gustaffson et al. [2] reported that approximately one-third of the food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted, amounting to 1.3 billion tons per year. It is noteworthy that in 2016, the fish available in the world market coming from catch, fisheries and aquaculture was 171 million tons; of this, 151.2 million was intended for human consumption, showing a record-high annual consumption of 20.3 kg per capita, with a growth average rate of about 1.5% per year [3]. In Italy, the consumption of fish in 2016 was around 31.1 kg per capita with an increase of 4% compared to the previous year [4]. It is interesting to note that possibly more than 50% of fish tissue, depending on the species, is not used as food and considered as a processing waste [5,6]. Depending on the origin of the fish–fishery or aquaculture—and on the species, the environmental sustainability of productions largely varies, with emissions of CO2-eq up to 6.6 kg per kg of fillet [7]. Thus, fish cannot be always considered more sustainable than meat, because the environmental impact of different fish products might be quite variable. Notwithstanding, changing the classical fishing activity to a more sustainable one can bring noticeable advantages, as highlighted in the 2020 Blue Economy Report [8].

Managing future human nutrition, ensuring a healthy diet, while promoting the sustainability of food production, is thus the primary challenge to be faced. The key step to building a new and sustainable food production system is to work towards a more rational exploitation of environmental resources. This objective involves the recovery and recycling of nutrients and molecules of interest from secondary raw materials, at both industrial and domestic levels.

As this commitment can no longer be extended, we must look at secondary raw materials as a resource, in terms of benefits for various productive sectors. Food waste mainly results in losses of nutrients and bioactive molecules (such as lipids, vitamins, polyphenols, antioxidants etc.) that may be re-utilised as active principles for many industrial applications, if recovered from by-products before any degradation process occurs. It should be taken into account that everything is part of “food production”, from the formulation of food products to the production of safer food additives, food colorants, new packaging systems, as well as the formulation of nutraceutics. Seizing these opportunities means aiming for zero losses and, at the same time, working to enhance the environmental sustainability, the production of safer food and, consequently, promoting a healthier life-style. The most immediate consequence of pursuing these objectives is creating new businesses concerning the recovery of nutrients and bioactive molecules from food waste and bio-based products which contain a higher variety of highly marketable compounds.

In this paper, an approach to the valorization of waste from the marine food-chain is described. The case-study reported here was aimed to release high-quality output from “resources” like the wastes and by-products resulting from human activities (fisheries and aquaculture); these resources are potentially useful to the industry for different purposes that can promote future business opportunities and contribute to the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). The authors highlight the importance of the valorization of food waste, looking at options which can minimize the environmental impact of food production [9,10]. The intrinsic added-value of seafood processing waste and by-products, characterized by a high content of organic matter, can be enormous; this value relies on several molecules that can be utilized to develop high-value food-products, nutraceutical, functional foods for specific population segments, as well as for other industrial applications.

2. The Context: Recent Trends and Prospects

The FAO report [3] showed that with the increase in fish processing industry, rising amounts of offal and other by-products are produced. The processing of fish catch in Italy annually produces over 26,500 tons of waste, approximately corresponding to 1.5% of the whole agro-food industry [11]. Fish products represent a good source of protein and micronutrients; indeed, several studies indicate fish consumption as a protective factor in the diet. Seafood processing by-products are characterized by a high intrinsic value for their content in functional molecules, such as proteins, collagen, bioactive peptides, polyunsaturated fatty acids, chitin, fat soluble vitamins [12,13,14,15,16]. Many of these molecules are known to have different healthy properties: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunostimulant, anti-hypertensive, anti-atherosclerotic, cardioprotective [17,18,19,20]. Studies showed also the great importance of omega-3 fatty acids in the early stages of brain and retinal development, with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) being a component of brain nerve synapses [21,22,23]. An inverse relationship between omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer disease has been reported [24]. The consumption of long chain fatty acids, especially omega-3, is associated with a lowered risk in major adverse cardiovascular events [25,26,27]. A direct relationship between the dietary intake or supplementation of both docosahexaenoic (DHA, 22:6 n-3) and eicosapentaenoic (EPA, 20:5 n-3) and a reduced incidence of coronary heart diseases (CHD) has been remarked [18]. The molecular mechanism through which omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) exert their preventive effects includes the shift of lipids from the omega-6 to the omega-3 metabolic pathway and the modulation of genes associated with both lipid catabolism and anabolism [28]. Consequently, omega-3 PUFAs help to maintain the normal levels of systemic biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), such as plasma cholesterol and triglycerides, oxidative stress, and blood pressure. In the last few years there has been renewed attention to an adequate intake of omega-3 fatty acids and to the importance of fish consumption as a natural supplier of these molecules. The consumption of fish is the best way to guarantee the necessary intake of omega-3, corresponding to 250 mg/day of EPA-DHA and 500 mg/day for primary prevention (e.g., CVD, dyslipidemias) [29]. Nevertheless, supplementation with fish oils supplying high levels of both EPA and DHA may be necessary in some cases. The high incidence of CHD in western countries increased the demand in both the dietary and nutraceutical sectors for functional foods and supplements enriched with omega-3, to compensate for nutritional deficiencies or to support physiological processes. Other than the nutritional field, key applications of oil rich in PUFAs, including cosmetics [30] and biotechnological/industrial applications for recovered oil (such as biodiesel), have also been developed [31].

2.1. Aim of the PROBIS Project

Recovery and valorization of agri-food waste, reduction in waste and sustainable use of natural resources. These are the green themes that characterize the PROBIS project “Innovative and sustainable biotechnological processes for the recovery of molecules of nutraceutical interest from waste from the fish supply chain”, the aim of which is to obtain products with high added value for the food, nutraceutical and cosmeceutical sectors. The research group consists of researchers from university (Department of Chemical Engineering Materials and Environment of Sapienza University of Rome) and research institutions (CREA-AN in Rome). The integration of interdisciplinary scientific skills, ranging from chemistry to process engineering, will enable us to achieve the ambitious goal of developing innovative and sustainable biotechnological processes to obtain products of high health value from the waste of the marine food chain.

The case study reported here aims to valorize waste from the fish supply chain, through the extraction and isolation of functional molecules to be used as added-value products in the dietary and nutraceutical sectors.

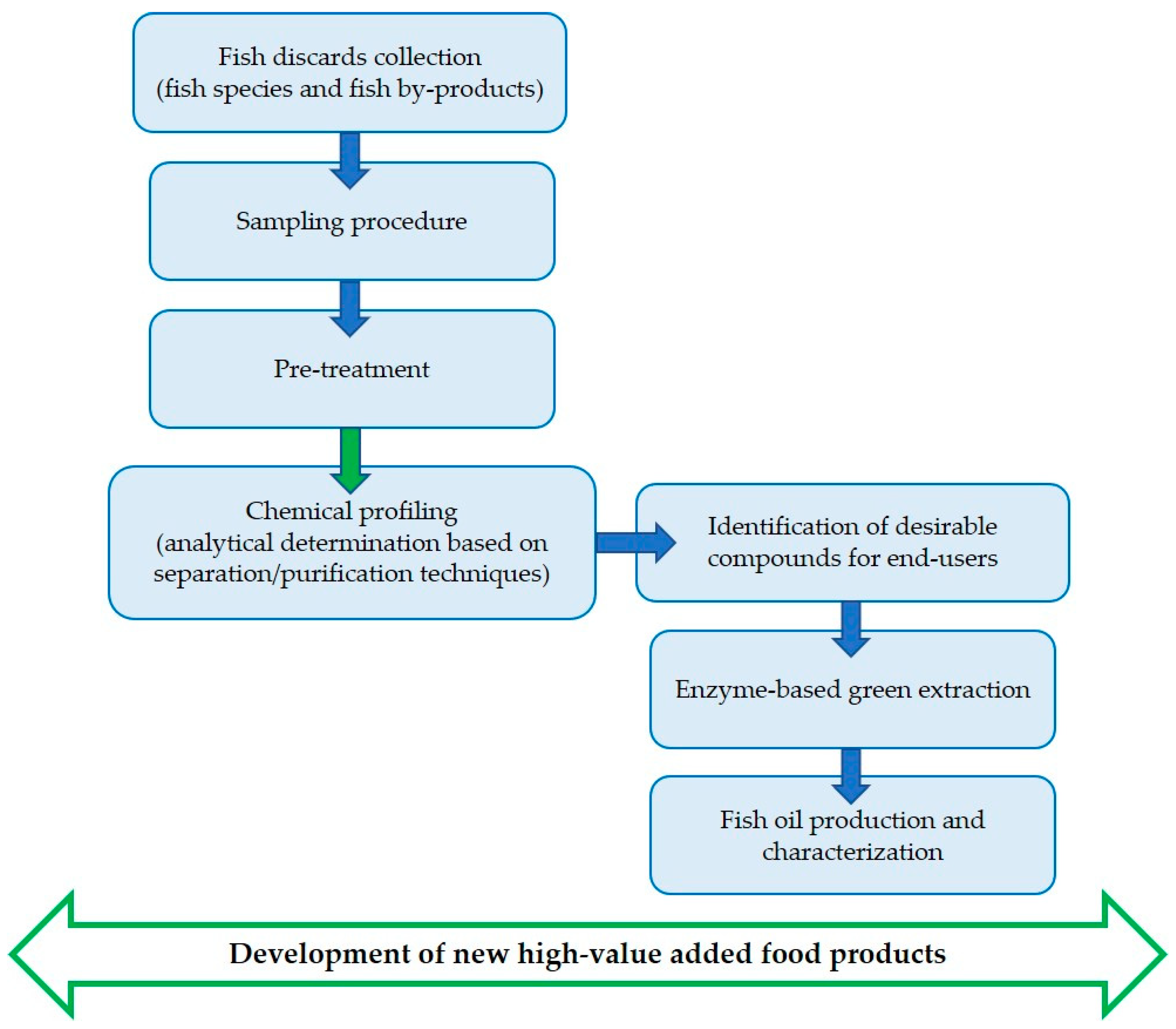

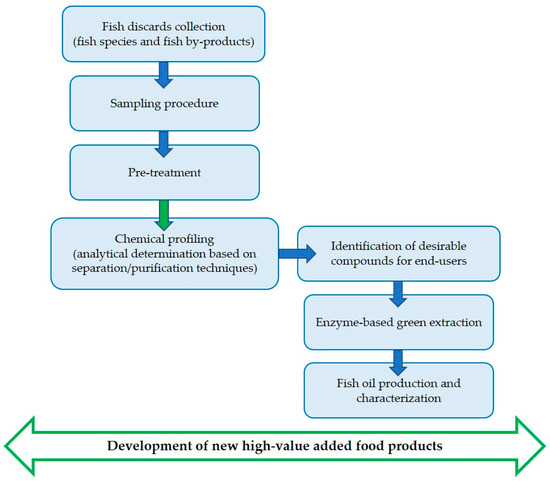

The mentioned study is addressed to exploit fish processing by-products, unsuitable for human consumption but rich in valuable nutrients and healthy bioactive molecules, by recovering omega-3 fatty acids and α-tocopherol (Figure 1). The target molecules identified in these types of secondary raw materials can be utilized for successive applications in various production sectors, such as nutritional, nutraceutical, and other food applications; with this approach, it is possible to fulfill market requirements and to close the virtuous circle of the hemi-life of foods in a contest for a circular economy.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive screening of fish materials adopted in PROBIS project.

2.2. Characterization and Exploitation of By-Products from the Marine Food Chain: Methodologies

In detail, the study is focused on the recovery of fish oil and in particular omega-3 fatty acids (EPA, DHA), as well as their quantitation, alongside fat-soluble vitamins. Nowadays, the global market is lacking high-quality fish oil. Its request from the aquaculture and nutraceutical sectors is increasing, while wild fish catches, necessary to produce fish oil, represent a limited resource. Fish-derived oil is characterized by a high nutritional value, since it contains high quality lipids, namely long-chain fatty acids, such as omega-3. EPA and DHA are the major omega-3 compounds of marine origin [30]. Marine waste was reported as an important source of omega-3 PUFAs and anchovy oil was shown as having the highest EPA and DHA content (about 30%) [32,33,34,35,36].

The fish secondary raw materials utilized in the study are heads, viscera and frames from anchovies and sea breams. Anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) are among the most important commercial fish species landed in the EU, its landings amounting to 127,561 tons (data updated to 2017, source: EUMOFA EU fish market 2019) [3]. In Italy, anchovies are the most abundantly caught species, with landings (39,000 tons in 2017) representing 20% of total fishery landings. The gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) is one of the most commonly farmed fish species in the EU, especially in Mediterranean countries, its overall production amounting to 94,936 tons in 2017. In Italy, where sea bream production comes mainly from aquaculture, its value amounted to 7000 tons in 2017, a number accounting for about 5% of total national aquaculture production (156,000 tons) [3].

The study intended to valorize fish processing by-products through the recovery of fish oil and bioactive compounds (omega-3: EPA, 20:5 n-3 and DHA, 22:6 n-3, fat soluble vitamins) by means of an innovative multistage and green process. The recovered molecules are intended for human consumption in different formulations (meal-food products, dietary supplements); therefore, the extraction processes and the pilot scale plants were designed to pay attention to both ecological and economic sustainability. The innovative green-type extraction of omega-3 fatty acids is thus addressed to reduce the introduction of hazardous substances in food products in order to ensure safety to the end-users.

The proposed process for the integral valorization of secondary raw materials from the seafood-chain was conceived to maximize the recovery of products of interest, while preserving their functional properties avoiding, at the same time, the use of solvents. The process is based on an enzymatic pretreatment of the waste, followed by hydrothermal extraction under mild conditions of the treated material. The enzymatic degradation of the fish matrix provides two major benefits: (a) enhanced release of the oil from the waste material and (b) improved quality and safety of this product. The use of enzymes as pretreatment agents and water as the extraction solvent makes the overall process environmentally friendly and very attractive for food and cosmetic applications.

A critical aspect of the process is the availability of enzymes capable of treating fish wastes originating from different fish parts and species. To this end, a statistical mixture design approach was used. The potential of this method has been demonstrated in a variety of extraction and separation processes, ranging from the recovery of lipids from microalgae [37] to the degradation of lignocellulosic biomass [38] and the extraction of lycopene from tomato processing waste [39]. The first step of this procedure consists of a preliminary screening of potentially suitable enzymes in order to identify the best ones. The selected enzymes are then used to formulate enzyme mixtures with high degradation activity. Since fish waste is very rich in proteins, enzymes with endo- and exo-protease activities were selected as pretreatment agents. They are listed in Table 1, together with their biological source.

Table 1.

Enzymes used in the PROBIS project for preliminary screening of mixture components.

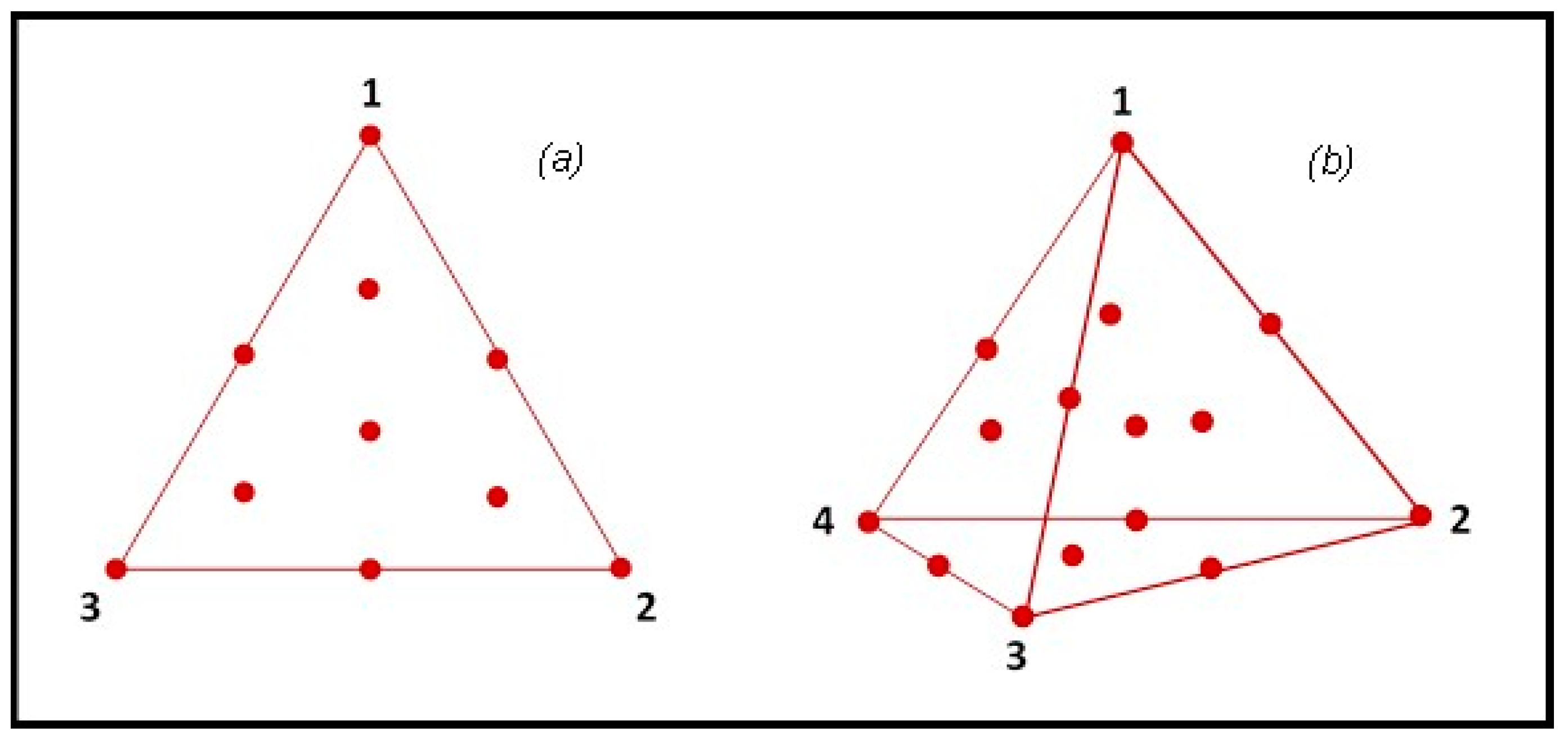

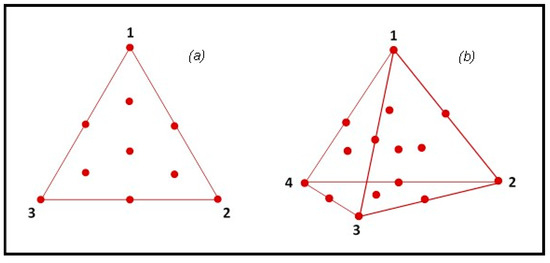

Two augmented simplex centroid designs (ASCDs) were used to formulate three- or four-component enzyme mixtures [40]. Mixture components were selected from those with the highest ranking in screening tests. The first ASCD consisted of a {3,2} simplex lattice design and the second of a {4,3} simplex lattice design (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simplex centroid designs adopted in the PROBIS project for the study of ternary (a) and quaternary (b) enzyme mixtures.

In both designs, the central point and the vertices were replicated, for a total of 17 and 20 runs, respectively. Depending on the response variable (e.g., the yield of oil extraction, the profile of extracted compounds or some specific bioactivities), optimized multienzyme formulations can be obtained by maximization of the variable of interest. The Design-Expert® software (version 7.0, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to plan the experiments and then to analyze the results.

According to the proposed process, the enzymatically treated material is then subjected to pressurized extraction with water. Extraction is carried out at a pressure slightly higher than atmospheric pressure (1.5–3 atm) and a temperature in the range of 120–140 °C for 10–30 min [41]. These conditions allow for efficient extraction of oil from the fish waste and recovery of polar bioactive compounds in the aqueous phase, without consistent degradation of the extracted compounds [42]. As a result, three product fractions are obtained: fish oil, an aqueous phase containing the bioactive polar compounds and a solid residue. Separation of these fractions can be easily achieved by conventional decanters, such as those used in the olive oil industry.

Fish oil can be refined and stabilized through usual oil treatments, while the aqueous phase can be evaporated or lyophilized to obtain the powdered bioactive compounds. Additionally, the solid residue can be exploited, to give a new ingredient of high nutritional value for the food and feed industries.

As for the analytical characterization of fish secondary raw materials, as well as the products obtained from the enzymatic process, two main analytical techniques are proposed: gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for the analysis of the fatty acids profile, and Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) on attenuated total reflectance (ATR) as a non-destructive and rapid technique to characterize the samples. Indeed, the perspective of this integrated approach is to use these two techniques to generate specific data matrices, employed for the application of chemometric methods [43,44,45].

The relationships between the FTIR spectrum data and those from the GC-MS method will be determined using the software TQ Analyst. By implementing the partial least square (PLS) method, a model can be obtained, which relates the quantitative chromatographic results with FTIR spectra. Then, the model can be used to predict the fatty acids concentration in unknown samples.

Total lipids were extracted from fish waste samples according to Bligh and Dyer [46] and the obtained fatty acids were methylated [47]. The relative quantitation of the fatty acid methyl esters was accomplished by GC-MS-FID (7890A Series-Agilent Technologies Santa Clara, CA, USA); a Mega-wax column (30 m × 0.32 mm inner diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness) was used for separation; the identification of target analytes was performed using the NIST08 Mass Spectral Library (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and comparing the retention times with known authentic standards. In this order, the fatty acids methyl ester (FAME) mix C4-C24 (Supelco, Bellofonte PA, USA) was analyzed as a control for qualitative confirmation. Relative quantitation was performed by calculating the percentage of each FAME peak over the total chromatographic areas.

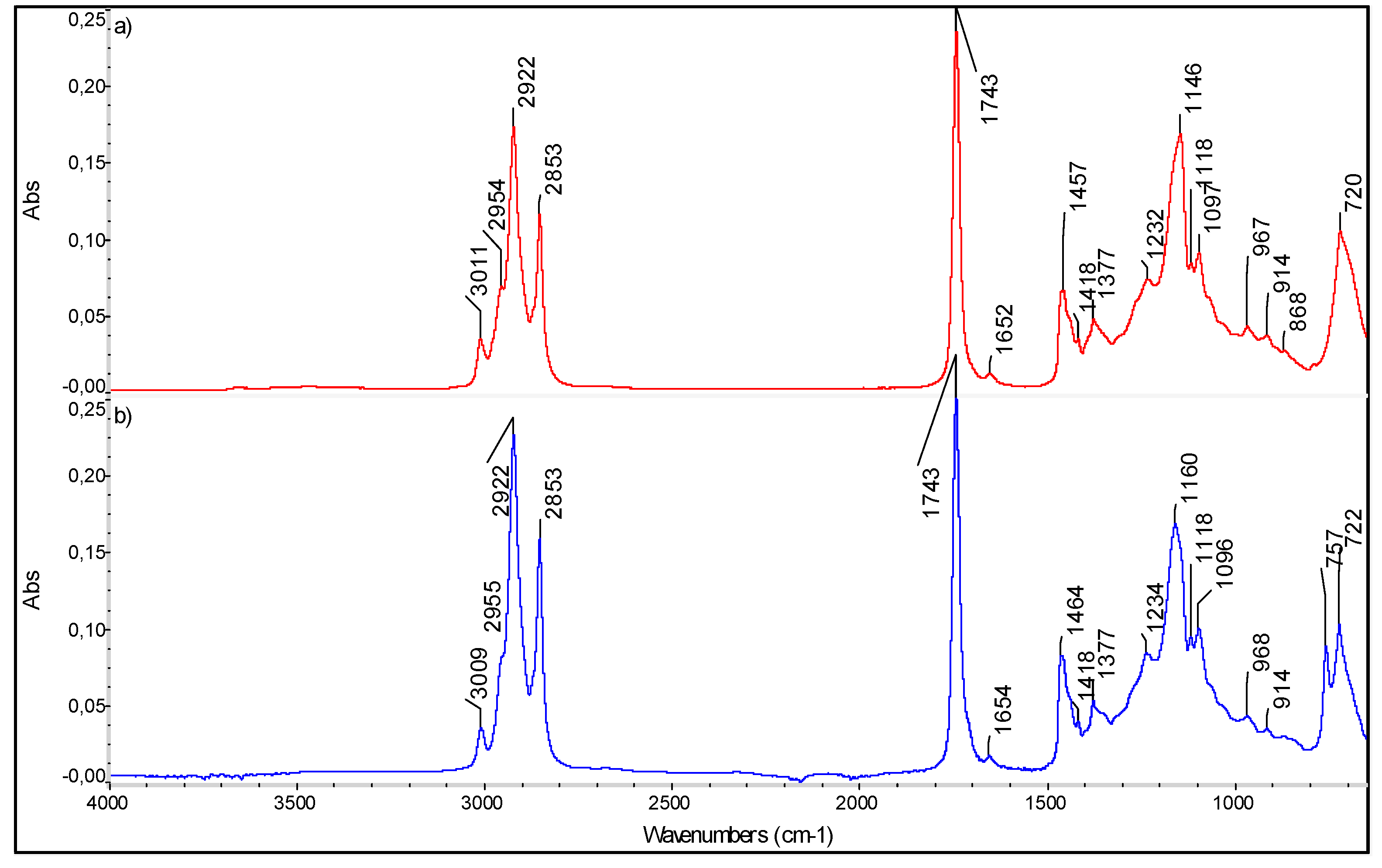

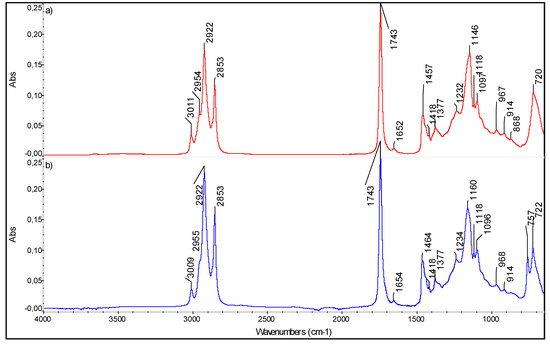

The data obtained from the chromatographic experiments will be used for subsequent calibration in FTIR ATR experiments. The spectra are acquired in the range of 4000–500 cm−1, with 32 scans per sample or background, at a nominal resolution of 4 cm−1 on a Nicolet iS10 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltam, MA, USA). These methodologies are applied to obtain lipid-rich-extracts of sea bream gut oil, reported as a case-study of the PROBIS project (Figure 3). The first step is a qualitative analysis, accomplished by identifying the main functional groups; in fact, FTIR provides a characteristic signature of the chemical substances present in a sample by featuring their molecular vibrations (stretching, bending, and torsions of the chemical bonds). FTIR spectra were analyzed with respect to the spectral band positions and an assignment of the main bands to the major functional groups was carried out by comparing the acquired spectra with the literature.

Figure 3.

FTIR Spectra of (a) unsaturated fatty acids standard mixture (FAPAS Test Material, containing alpha linoleic acid, EPA, DHA, DPA) and (b) sea bream gut oil (preliminary results of the PROBIS project).

In Figure 3, the spectra of (a) unsaturated fatty acids standard mixture (FAPAS Test Material containing alpha linoleic acid, EPA, DHA, DPA) and (b) sea bream gut oil are reported, as preliminary data of the PROBIS project.

In the latter, the relatively high intensity of the band near 3010 cm-1 is indicative of a high concentration of total n-3 PUFAs. As shown in the infrared spectra (Figure 3), the characteristic peaks at positions of 2922 and 2853 and 1464 cm−1 are assigned to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of CH2 groups [48,49]. The characteristic sharp band at 1743 cm−1 is due to the asymmetric stretching of C = O in the carboxyl group [50]. The band at 1652 cm−1 is related to C = C stretching vibration of cis-olefins. The bands at 1464 and 1377 cm−1 are related to bending (scissoring) vibrations of the bonds in aliphatic groups (CH2 and CH3, respectively). The band at 1234 cm−1 is related to symmetric bending vibrations of CH2 groups, whereas the bands at 1160 cm−1 and 1096 cm-1 are due to stretching vibrations of the C–O bond in the ester group. The absorption peak at 722 cm−1 is given by the overlapping peaks of CH2 rocking vibration and the out-of-plane vibration of cis-disubstituted olefins. The FTIR spectra of samples at different concentration were acquired and the fingerprint regions were identified; then, a regression model relating chromatographic and spectral data can be computed; indeed, the intensity of the absorption bands characteristic of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids can be related to their concentration. This analytical approach exploits chemometrics to simplify the entire analysis cycle, avoiding the massive use of solvents and also limiting the number of analyses to be carried out, consequently speeding up the whole process.

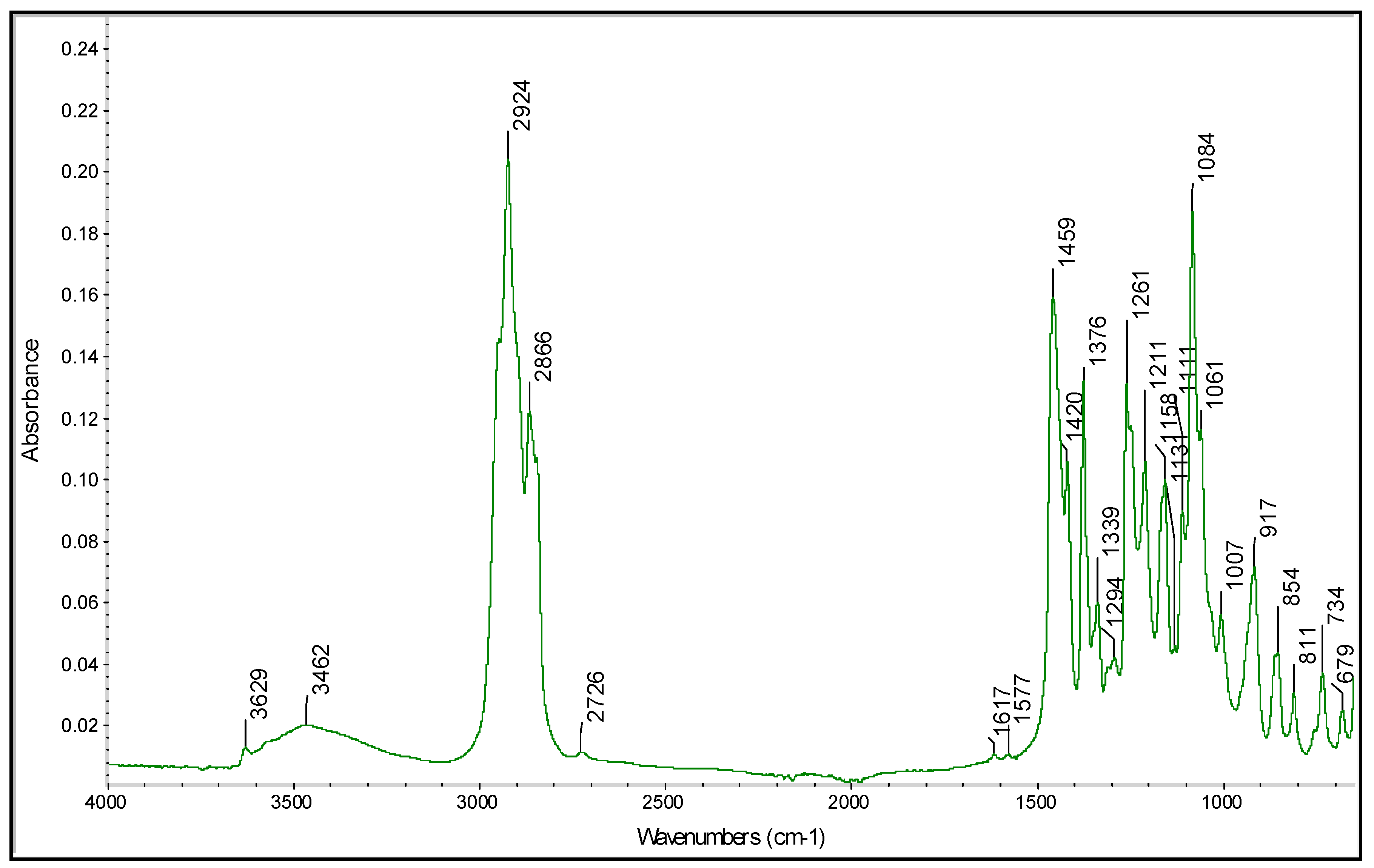

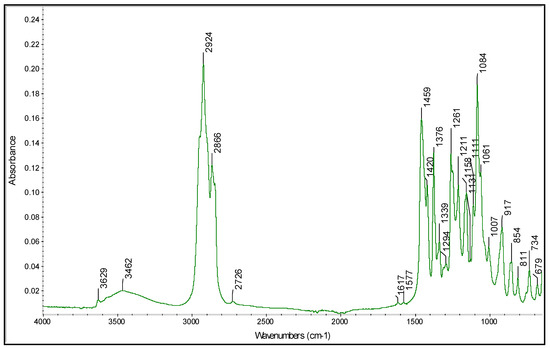

A similar analytical workflow can be proposed to predict the α-tocopherol content in the samples. The FTIR data used in this case correspond to the spectral region characteristic of vitamin E. In particular, as reported in Figure 4, the α-tocopherol spectrum exhibited absorption bands at the following wavelengths: 3462 cm−1 for –OH; 2924 and 2866 cm−1 for the CH2 and CH3 asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations, respectively; 1450 cm−1 for phenyl skeletal and 1460 cm−1 for methyl asymmetric bending; 1376 cm−1 and 1261 cm−1 for methyl and methylene symmetric bending, respectively; 1084 cm−1 for phenyl plane bending; 917 cm−1 for trans = CH2 stretching.

Figure 4.

Spectra of α-tocopherol acquired as preliminary data from the PROBIS project.

These assignments are based upon previous work on α-tocopherol [51,52]. The vitamin E determination will be carried out by LC-MS/MS using a method developed in our laboratories [53]. Then, a calibration model can be designed by analyzing samples containing different amounts of α-tocopherol and correlating the known concentrations to the FTIR spectra. Once again, the model can be computed by applying the PLS algorithm and, after validation, can be used to predict the α-tocopherol content in unknown samples.

3. Conclusions

The overall perspective of the sustainable management of the marine food-chain aims to contribute to the recovery and valorization of secondary raw materials from the fisheries industry. The sustainable production of natural molecules (mainly omega-3 fatty acids) for new products for human nutrition is in line with the growing request for the innovation of food products, dietetic products and the nutraceutical sector.

The main core of the case study reported is the treatment of food waste for the reuse of bioactive molecules and the transformation of discards into high added-value products; however, particular attention is also payed to the development of environmentally friendly protocols to be applied to the raw material. In fact, the cornerstone of the project is to pursue both diet sustainability and environment protection, considering all levels of the production cycle. This goes from the limitation of waste release in the environment, to the development of green-protocols, allowing for the avoidance of using potential polluting chemicals, while obtaining end-products intended for human nutrition.

The pursued approach fosters the development of new value chains, generating new resources and opportunities for the local economic system. The type of waste, the geographical area of the producers (both at the fish catch scale and processing industrial scale) are all factors that contribute positively to the sustainability of the whole recovery process proposed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., and G.L.-B.; R.L., methodology, M.L., A.Z. and G.L.-B.; formal analysis, A.D., B.B.; data curation, A.D., M.L., A.Z., B.B., writing of the original manuscript, G.L.-B., A.Z.; review and editing of the manuscript, M.L., A.D., G.D.L., A.Z., R.L., B.B. and G.L.B.; project administration, G.L.-B.; all authors made a substantial contribution to the work and approved its publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study reported was funded by REGIONE LAZIO (Italy), PROBIS project, Contributo Prot.85-2017-15255.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Premanandh, J. Factors affecting food security and contribution of modern technologies in food sustainability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2707–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e00.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. 2018. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i9540en/I9540EN.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products. The EU Fish Market; Edition Luxembourg; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Li, E.; Irshad, S.; Xiong, Z.; Xiong, H.; Shahbaz, H.M.; Siddique, F. Valorization of fisheries by-products: Challenges and technical concerns to food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.A.; Adnan, M.; Patel, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Sachidanandan, M.; Snoussi, M.; Hadi, S. Fish-Based Bioactives as Potent Nutraceuticals: Exploring the Therapeutic Perspective of Sustainable Food from the Sea. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchspies, B.; Tölle, S.J.; Jungbluth, N. Life Cycle Assessment of High-Sea Fish and Salmon Aquaculture; ESU-services Ltd.: Schaffhausen, Switzerland, 2011; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020 Blue Economy Report: Blue Sectors Contribute to the Recovery and Pave Way for EU Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermeersch, T.; Alvarenga, R.A.F.; Ragaert, P.; Dewulf, J. Environmental sustainability assessment of food valorization options. Res. Cons. Rec. 2014, 87, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, S.M.; Martinez, N.M. Conserving natural resources through food loss reduction: Production and consumption of the food supply chain. Int. Soil Water Cons. Res. 2018, 6, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecocerved. Industria Alimentare e Rifiuti: Anni 2008–2011; Ecocerved: Padova, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Mendis, E. Bioactive compounds from marine processing byproducts—A review. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Kassaveti, A. Fish industry waste: Treatments, environmental impacts, current and potential uses. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, O.; Vaquiro, H.; Solanilla, J.F. Fish viscera protein hydrolysates: Production, potential applications and functional and bioactive properties. Food Chem. 2017, 224, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Sillero, J.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Prentice, C. Peptides from Fish by-product Protein Hydrolysates and Its Functional Properties: An Overview. Mar. Biotechnol. 2018, 20, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Harris, W.S.; Appel, L.J. Fish consumption, fish oil, Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2002, 106, 2747–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R.V.; Mehra, M.R.; Ventura, H.O. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysohoou, C.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Skoumas, J.; Krinos, X.; Yannis, C.; Vassilios, N.; Stefanadis, C. Long-term fish consumption is associated with protection against arrhythmia in healthy persons in a Mediterranean region—The ATTICA study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.; Block, R.; Mousa, S.A. Omega-3 fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health benefits throughout life. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innis, S.M. Dietary omega 3 fatty acids and the developing brain. Brain Res. 2008, 1237, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querques, G.; Forte, R.; Souied, E.H. Retina and Omega-3. J. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 2011, 748361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire, E. Brain health across the lifespan: A systematic review on the role of omega-3 fatty acid supplements. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.L. Omega-3 fatty acids, cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease: A critical review and evaluation of the literature. J. Alzheimer Dis. 2010, 21, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Harris, W.S.; Appel, L.J. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases: New reccomandations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 99–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, W.S.; Poston, W.C.; Haddock, C.K. Tissue n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and risk for coronary heart disease events. Atherosclerosis 2007, 193, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GISSI-HF Investigators. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, A.S.; Brown, T.J.; Brainard, J.S.; Biswas, P.; Thorpe, G.C.; Moore, H.J.; Deane, K.H.; AlAbdulghafoor, F.K.; Summerbell, C.D.; Worthington, H.V.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, H.; Panchal, S.K.; Diwan, V.; Brown, L. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: Effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 50, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion related to the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2815. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2815 (accessed on 28 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M.; Patsioura, A.; Gekas, V. Enzyme kinetics modeling as a tool to optimize food biotechnology applications: A pragmatic approach based on amylolytic enzymes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 55, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Kunisawa, N.; Kojima, T.; Murakami, S. Evaluation of ozone treated fish waste oil as a fuel for transportation. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2004, 37, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroig, O.; Tocher, D.R.; Castro, L.F. Polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism in fish. In Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Metabolism; Burdge, G.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; AOCS: Urbana, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, L.; Volpe, M.; Lucian, M.; Anesi, A.; Manfrini, M.; Guella, G. From Fish Waste to Omega-3 Concentrates in a Biorefinery Concept. Waste Biomass Valor. 2017, 8, 2609–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajafari, S.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Nasrpour, S.; Golmakani, M.T.; Nikaein, F. Comparison of enzymatic hydrolysis and chemical methods for oil extraction from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) waste and its influence onomega 3 fatty acid profile. Int. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 2, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Iberahim, N.I.; Hamzah, Z.; Yin, Y.J.; Sohaimi, K.S.A. Extraction and characterization of Omega-3 fatty acid from catfish using enzymatic hydrolysis technique. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 187, 01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kralovec, J.A.; Zhang, S.C.; Zhan, W.; Barrow, C.J. A review of the progress in enzymatic concentration and microencapsulation of omega-3 rich oil from fish and microbial sources. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A.; Malavasi, V.; Cao, G.; Lavecchia, R. Use of cell wall degrading enzymes to improve the recovery of lipids from Chlorella sorokiniana. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 377, 120325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.E.; Fox, J.M.; Clark, D.S.; Blanch, H.W. A mechanistic model for rational design of optimal cellulase mixtures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 2561–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A. Enhanced lycopene extraction from tomato peels by optimized mixed-polarity solvent mixtures. Molecules 2020, 25, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 530–539. [Google Scholar]

- Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Sarasini, F.; Tirillò, J.; Maffei, G.; Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Kenny, J.M.; Torre, L. Valorization and extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from North African grass: Ampelodesmos mauritanicus (Diss). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, G.; Bracciale, M.P.; Broggi, A.; Zuorro, A.; Santarelli, M.L.; Lavecchia, R. Effect of an enzymatic treatment with cellulase and mannanase on the structural properties of Nannochloropsis microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsvivut, J.; Heraud, P.; Zhang, W.; Kralovec, J.A.; McNaughton, D.; Barrow, C.J. Quantitative determination of fatty acid compositions in micro-encapsulated fish-oil supplements using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, D.; de Araứjo, V.M.; Jarvis, B. Observations on the use of statistical methods in Food Science and Technology. Food Res. Int. 2014, 55, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, M.; Durazzo, A.; Sanchez del Pulgar, J.; Gabrielli, P.; Lombardi-Bocia, G. Determination of fatty acid content in meat and meat products: The FTIR-ATR approach. Food Chem. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, L.D.; Schmitz, A.A. The rapid preparation of fatty acid esters for gas chromatographic analysis. Anal. Chem. 1961, 33, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.M.F.; Brandao, P.R.G.; Peres, A.E.C. The infrared spectra of amine collectors used in the flotation of iron ores. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, L.J. The Infrared Spectra of Complex Molecules; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.B.; Cheng, J.H.; Wen, S.M.; Li, C.X.; Bai, S.J.; Liu, D. A mixed collector system for phosphate flotation. Miner. Eng. 2015, 78, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.D.; Rosa, N.F.; Ferreira, A.E.; Boas, L.V.; Bronze, M.R. Rapid Determination of Alpha-Tocopherol in Vegetable Oils by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Food Anal. Meth. 2009, 2, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Y.B.C.; Ammawath, W.; Mirghani, M.E.S. Analytical, nutritional and clinical methods: Determining α-tocopherol in refined bleached and deodorized palm olein by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Evoli, L.; Tufi, S.; Gabrielli, P.; Lucarini, M.; Lombardi-Boccia, G. Analisi simultanea della vitamina E in campioni alimentari tramite cromatografia liquida-spettrometria di massa. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).