Abstract

The new coronavirus caught governments all over the world completely unaware, which led to a set of different and sometimes not quite articulated responses, leading to some undesirable results. The present investigation is based on three objectives: to assess the conditions “before” and “during” the combat and the expected consequences “after” the outbreak, by having as reference the Portuguese case; to offer a framework of the input factors to crisis management in the pandemic context; and to contribute to the crisis management literature, in the public sector from a perspective of collaborative and multi-level governance. This research is inductive and follows a quantitative approach, with the proposal and testing of a crisis management COVID-19 structural model. The Portuguese case presented in this paper suggests a robust and valid crisis management model. This model may be well translated for other countries with cultural proximity to the Portuguese culture, for instance, Portuguese speaking countries such as Brazil, or geographical proximity to Portugal such as, for instance, Spain. The authors, nevertheless, advise readers to exert some restraint on the extrapolation of the results, as governance systems and traditions can vary a good deal from country to country. Future studies should focus on the importance of coordination as one of the most important areas in crisis management, narrowing the scope of analysis from the broad, macro understanding of the research problem presented on this paper.

1. A New Reality Offered by the Old Virus

The fast dissemination of COVID-19 caught governments unprepared, which led to different responses, sometimes not very articulated with each other. The countries embraced several measures, such as school closure, border closure, population agglomerations forbidden at public spaces, information dissemination regarding the need for a regular hand hygiene, social distancing no less than 2 m, and prophylactic confinement [1], among other measures. The idea that policymakers should focus on the effectiveness of the response by planning, strategic, and coordinated alignment, instead of a reactive nature, and even a precipitated nature, led to different levels of response quality for the communities. Analyzing different indicators, from other parts of the world, the discrepancies become clear. The physiological structure of the virus has been explored [2], and worldwide efforts have been made in the search for a vaccine to fight the virus. Meanwhile, scientific evidence must be the basis for government decisions [3].

The current pandemic crisis elevates a demanding government response, thereby, by having the Portuguese case as reference [4], this paper has three macro objectives: to assess what conditions existed in the moments “before” the pandemic, the conditions offered “during” the combat, and the expected consequences “after” the outbreak; to offer an aggregating framework of the contributory factors to crisis management in the pandemic context; and to contribute to the crisis management literature in the public sector from a perspective of collaborative and multilevel governance with a valid structural model on crisis management. Following these objectives and considering the three macro moments in a crisis-management operation, an analysis was developed in the following phases: (a) pre-crisis phase; (b) crisis phase; and (c) post-crisis phase.

2. The Importance of Multi-Level Governance on the Crisis Management

In the study of European policy formulation, multi-level governance has awakened attention within researchers. The European political activity has an institutional complexity, and even national policymaking has its intricacies. Therefore, multi-level governance has been used to provide a simple idea on pluralism and on stakeholders—individuals and institutions—both internal and external, and participation in several political levels, from supranational to subnational (regional) or local [5]. Multi-level governance implies concepts of commitment and influence—theoretically, there is no superior level of activity, therefore, it exists as a mutual dependency between the supranational and the subnational through the policy making process.

The literature on multi-level governance has multiplied since its first reference in a scientific paper [6]. The term emerged as a vertical arrangement and a way of conveying the involvement between national and international authority levels [5]. According to a European vision of the multi-level governance process, it can be defined as a continuous negotiation system between governments. These governments are in several territorial levels, where authority is dispersed along the administrative levels, vertically, and it is also dispersed horizontally between different influential scopes (non-governmental actors, markets, and civil society). The subsidiarity principle is in its basis; therefore, decisions are not only centered in one power level and inappropriate policies implemented at territorial and institutional level are avoided. This implies the share of responsibilities between the different levels of power and the stakeholder’s participation in the public policy cycle.

The Cohesion Policy has enhanced the emergence of new political arenas, public policies management, and the creation of intermediate government structures. These new political arenas are a synonym of public engagement from regional actors [7]. Thereby, multi-level governance needs to face two challenges: on the one hand, the need to promote vertical rearticulation within intergovernmental relations; on the other hand, relations with civil society and private sector actors reconfigured horizontally, based on the desire for a closer relationship.

Multi-level governance has been widely used for analyzing institutional arrangements, aiming at the implementation of structural funds in the Cohesion Policy. It has revealed different formal and informal rules at the national and supranational level. Considering the government’s functional and administrative capacity, the coordination focus and partnership in several phases of the policymaking process implies pluralistic interactions at distinct institutional levels. The goal is to govern united [5]. However, national studies have revealed a persistent governance based on central control, quite related with divergent subnational practices—local government has shown itself incapacitated and with fragmentation challenges. It is fundamental to highlight that these issues may lead to a centralized and omnipotent state, and the subsidiary principle tends to disappear in this type of situation, especially when governments begin to implement undemocratic solutions that damage social bonds. The regionalization process, from where the differentiation was triggered, leads to administrative governmental capacities very diversified in several governmental arenas [8,9].

Therefore, it is crucial to also approach the theme of regional governance regarding the implications on fragmentation of authority, vertically and horizontally, on local decisions. This fragmentation may implicate an eventual disconnection and asynchronicity in the decision-making process, especially in moments of crisis. It causes major problems in the process of coordination between the different stakeholders (both internal and external), and in the face of a sufficiently serious crisis this fragmentation may bring harmful consequences.

In the literature, concerning the theme of regional governance, there has been a warm debate between supporters of local government mergers, in order to provide a more efficient public service, and support of the autonomy and self-determination of local government autonomy, aiming to ensure democracy. Local systems presented themselves as fragmented and polycentric, with different decision-making centers, so governance bodies are demanding to establish rules to reinforce and sustain a solid decision-making process. The democracy protection is in the center of the process of decentralization from center governments to the local governments; although, as mentioned above, this process of decentralization brought problems of fragmentation to local realities [10].

In this respect, Institutional Collective Action (ICA) dilemmas urge local government to inferior with results when this fragmentation of authority is conducted. Several European countries have been choosing between two paths: on one hand, the merge of local governments to pursue the rise of capacity, economies of scale, and more efficiency in the results; on the other hand, local governments, more fragmentated, aiming at democracy, legitimacy, and responsiveness [10].

Intermunicipal cooperation it is very recent in this warm debate. Tavares and Feiock approached and deepened the framework of the Institutional Collective Action (ICA) for the European context, which is composed of two dimensions to comprehend international cooperation [10]:

- The type of urban integration mechanism: imposed authority, delegated authority, contracts, or social embeddedness.

- The degree of institutional scope: narrow, intermediate, or complex.

Collaboration in local realities depends on upper level rules; therefore, the national legal framework presents implications in this type of situation. National legislation that “facilitates self-organizing regional governance reduces collaboration risk” [10] (p. 7). Vertical intergovernmental relations found their roots in history and democracy, as a result of excessive centralization in the past, thereby, local agents struggle with the interference of central power. In other cases, countries with business–professional ties are more able to overcome and enhance the Institutional Collective Action dilemmas with the benefit of self-organizing mechanisms.

Moreover, in the panorama of crises that we are living in, some studies also advocate the importance of the citizens’ contributions for local government to engage in collaboration in the context of Institutional Collective Action [11,12,13].

The citizens’ role in emergency planning is considered an important key to local communities in order to minimize the negative consequences of disasters, by promoting knowledge regarding local conditions, and the fact that knowledge and awareness influence local decisions [11].

Overall, the literature underline that a previous and solid collaboration, based in effective preparation with agendas of mitigation, beyond administrative and political boundaries, can provide an effective response. Although fragmentation of authority disturbs the intergovernmental collaboration and the planning efforts, this is a challenge that governments must embrace to respond and recover from natural disaster such as the one we are living, in order to avoid harmful consequences and adverse effects [11].

Multi-Level Governance Dimensions

Given its transversal academic expansion, multi-level governance started to enter into the language of political decision-makers. In Europe there are a wide range of governance typologies (Table 1) [14];

Table 1.

Governance typologies applied in Europe.

To achieve the defined goals with the implementation of a decentralized processes, rooted in a multi-level governance, it is important to highlight how decisive the coordination model followed by the Institutional coordination is in essential crisis management and in the scenario offered by the current pandemic crisis. This institutional coordination allows for the maximization of efforts and alignment in each country. The World Health Organization, as crisis management maximum authority in the current crisis due the new coronavirus—COVID-19—serves as a starting point for the updated dissemination of information on the pandemic’s progress, and shares good practices to be adopted by all of us. This coordination aims to diminish the impacts on countries. It is up to each country—with their undeniable centrality—to elaborate specific norms to apply. These must be created within the legislative framework and be based on the country’s distinctive characteristics, for more extension and effectiveness on civil society. Thereby, a crisis management factor must be addressed from a multi-level perspective (Table 2):

Table 2.

Crisis management factors from a multi-level perspective.

3. Governance Capacity on Crisis Management in the Public Sector

Any political effective implementation requires a collaborative network basis. Only in this way will it be possible to deal with constant social mutations, lack of resources, and increasing organizational empowerment and its resulting interdependence [15]. To handle public bureaucracies to adapt to a crisis is a demanding task. It will only be possible with an efficient electronic governmental structure basis, such as the case of the Singapore governance system [16]. The process beyond a quality service provision in times of crisis is demanding and time-consuming. Although, if well-articulated and planned between all stakeholders (both internal and external), it will allow one to face crisis difficulties in a more prepared way [16].

In a crisis scenario, it is expected from leaders to reduce uncertainty and to provide an objective and clear report of what is happening, why it is happening, and what needs to be done.

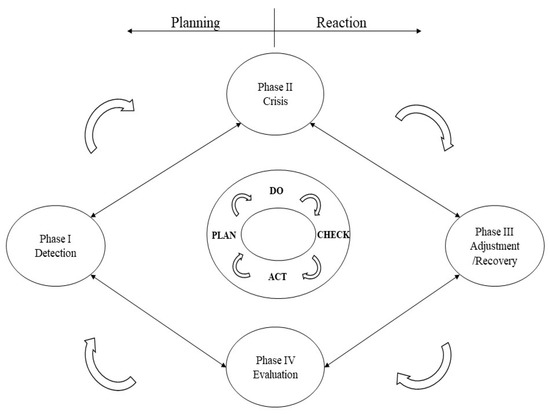

In 2003, the use of information technologies by the Singapore state was fundamental in the SARS combat. The available technological infrastructure accelerated the basis for crisis management—in technical terms, and over the years, in the development of the government’s electronic infrastructure increasing collaboration, coordination, and information technologies shared knowledge between governmental agencies [16]. It is also important to clear up the crisis definition. Burnett [17], thereafter Mitroff, Shrivastava, and Udwadia [18], presented the following definition: a crisis consists of a disturbance, which all the system is physically affected by, that threatens its foundations, its purpose of being, and its existential core. The macro phases in crisis management are close to the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle [19]. The cycle phases are phase I—detection; phase II—crisis; phase III—adjustment; phase IV—evaluation/improvement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phases of the crisis management process. Source: elaborated by the authors, adapted from [18].

The above phases demonstrate a crisis management process with its intrinsic dynamism. Practically speaking, it is not possible to divide—objectively—each one of the phases. Although, the theoretical framework developed for this paper allows a better deepening and understanding of each phase’s operation. It also enables practical comprehension improvement for implementation on the ground. Phase I deals with the crisis finding. This is the moment where every previous crisis combat mechanism must be applied on the ground—within its preventive dimension—and these mechanisms are rooted in a previous strategic plan. The core crisis appears in Phase II. Variables that were not anticipated by the previous planning may surge in this phase. Stakeholders’ (both internal and external) support is decisive to provide an effective and assertive response. It is also decisive for the right coordination between stakeholders (both internal and external) and intervention levels. In phase III and IV we reached the post-crisis scenario, therefore, the review of some issues is needed, namely: the need to evaluate what was done, how it was done, which resources were used, the initial planning followed in the action, if the planning requires adjustments for future situations, and to evaluate opportunities for future improvement. This cycle can be used as a valuable instrument in strategic planning, since allows for the supervision and monitoring from the status quo. In Portugal, this type of assessing has already been used, particularly in the public sector, with contingency plans, that are updated regularly, based in the needed adjustments and according to the coordination of the National Health Authorities.

4. Strategic Planning as an Instrument in the Service of Preventive Governance

In the public sector, strategic planning has its principal focus on strategic formulation [20]. Bryson [21], in his seminal book about strategic planning in the public sector and non-profit organizations, presents the strategic planning as a set of concepts, processes, and tools for shaping “what is an organization (or another entity), what is doing, and why”. The aim is to promote strategic thinking, actuation, and continuous learning in the long-term. The strategic planning adopts a global approach, combining futurist thinking, objective analysis, values, targets, objectives, and priority evaluation, in order to map a future direction and action to ensure vitality, effectiveness, and the capacity to assign public value to the community. However, action plan formulation or strategic planning process efforts have not always got a clear or objective extension in their concrete results [22]. According to the work of Hatry [22] the efforts of public bodies, which are used for strategic planning, are not considerable because the minimal criteria are not complied (e.g., desirable results identified and strategic development to reach them). Considered an orthodox practice in the public sector over the last 25 years [20], the strategic planning processes have a critical role these days, since governmental agents must anticipate and manage changes [20]. They also need to address new questions or situations. Our recent pandemic panorama is an example of the strategic position needed. For this strategic position, public bodies must design different scenarios based on today’s uncertainties and tendencies, acknowledging a considerable range for a wide set of possible solutions to implement in the future. The emergence of a new pandemic wave is unclear. Therefore, the authorities should start right away gathering information to design future scenarios. By doing this, if we face the worst predictions, governments will be better prepared, and able to provide an effective response.

Crisis management plans are an essential part of adequate crisis management. In Portugal, most of the crisis management plans are the responsibility of the Civil Protection Authority [23] the public service responsible for protection and relief operations. However, and arguably as happens all over the world, most crisis management plans are almost exclusively formal plans and often cannot be adapted to rapidly changing situations or “black swan” events, such as the Portuguese 2017 wild forest fire debacle, which is a recent reminder: 114 deaths, hundreds injured, more than 1300 residences destroyed, roughly 550 businesses and hundreds of jobs affected and losses that approach a billion euros; all in a few days as a result of two separate events.

5. Method

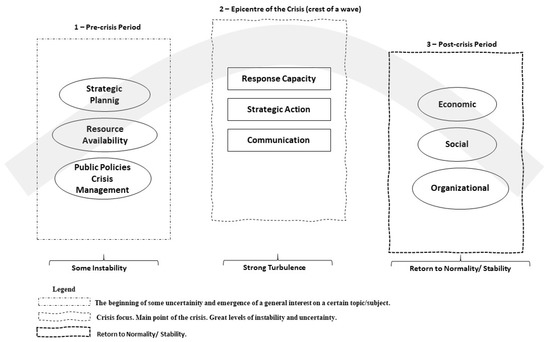

After presenting the three main bibliographic elements of this study, below is presented the initial design for the crisis management model, based on the literature review (Figure 2). The Wave Model (Figure 2) aims to schematize how the evolution of crisis management occurs—such as the one we are facing. In the pre-crisis period, we intended to evaluate the presence of the initial base conditions for facing a crisis. In this phase, the following dimensions were considered: strategic planning, resource availability, and public policies of crisis management. At the crest of the wave is where the epicenter of the crisis is located, in which resources are applied, actions implemented, and all crisis combat mechanisms are used—these mechanisms and actions are an output from the strategic planning and public policies formulation from the pre-crises phase, allowing for efficiency of the crisis management. Thereunder, the analyzed dimensions were, namely: governmental response capacity, strategic action by governmental bodies, and the quality of the information transmitted and its ways of communication. Lastly, in a post-crisis scenario, we aimed to assess the pandemic crisis impact in three large dimensions, namely: economic, social, and organizational.

Figure 2.

Initial theoretical model—Wave Model. Source: elaborated by the authors.

5.1. Data Treatment

The present research follows an inductive approach, since it is a study that collects data in order to validate the proposed survey, indicators, and the specific structural model, to allow for replication in other governmental realities. This research is quantitative, and the data were collected through a questionnaire [24]. The data collection instrument was formed with 15 categorical variables and with 47 indicators—scale variables (Table 3), quantified using Likert scales (in ascending order of valorization, all points are numbered, successively from 1 to 10). The questionnaire was applied online, between 26 March 2020 and 3 April 2020. A sample of 1256 was gathered, from which 773 (61.5%) are from the female gender, and 477 (38%) are from the male gender (From the total mentioned, six (0.5%) findings were blank). In total, 55 (4.4%) of the respondents are from the Alentejo region, 26 (2.1%) are from the Algarve region, 571 (45.5%) are from the metropolitan area of Lisbon, 460 (36.6%) are from the Centre, 114 (9.1%) are from the North, 20 (1.6%) are from the Autonomous Region of Madeira, and 5 (0.4%) are from the Autonomous Region of the Azores.

Table 3.

Crisis management: COVID-19 structural model items.

In terms of level of education, the following distribution was observed: 53 (4.2%) had with up to 9 years of schooling, 381 (30.3%) with among 10 and 12 years of schooling, 544 (43.3%) with graduation course, 234 (18.6%) with a master degree, and 37 (2.9%) with a doctorate. From the total mentioned, 298 (23.7%) respondents adhered to quarantine, interrupting their labor activity, 738 (58.8%), have also adhered to the quarantine, but they still continued to work from home, and 195 (15.5%) have not adhered to the quarantine.

5.2. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)

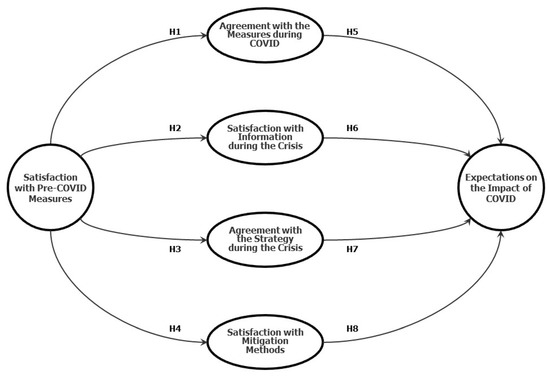

Data analysis was performed using the SPAD software, version 6.5. Structural equation analysis, also known as SEM methodology or PLS Path Modelling was performed to create the structural model. The use of this approach allows for the study of latent variables and their causal interrelations. Therefore, we intend to test the established hypothesis of Table 4. The crisis management: COVID-19 structural model was inspired in the proposed wave model. This structural model (Figure 3) is anchored in 6 dimensions (latent variables) with 47 indicators (scale variables) (Table 3). The analysis model is established by the set of causal relationships between the latent variables and the indicators—each of the interactions gives rise to a hypothesis tested in this research (H1 to H8) (Figure 3). The structural model presents 59032 data points.

Table 4.

Established hypothesis to validate.

Figure 3.

Crisis management: COVID-19 structural model. Source: elaborated by the authors.

6. Discussion of Results

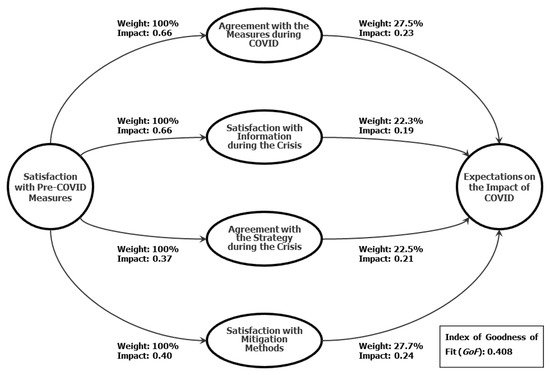

The proposed theoretical model (Figure 3) is effective (Figure 4) and validated (Table 5) with a Goodness of Fit index (GoF) of 0.408. From the obtained results, Table 5 presents the results of the averages, obtained in the evaluations of the latent variables through the analysis of the structural equation. The established hypotheses (Table 4) are validated, revealing the existence of dynamic relationships in the “before” moments, “during” the combat, and the expected consequences “after” the pandemic (Figure 4). Thereby, as shown in Figure 4, it was observed that: the dimension Agreement with the Measures during COVID suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Pre-COVID Measures (H1); the dimension Satisfaction with Information during the Crisis suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Pre-COVID Measures (H2); the dimension Agreement with the Strategy during the Crisis suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Pre-COVID Measures (H3); the dimension Satisfaction with Mitigation Methods suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Pre-COVID Measures (H4); the dimension Expectations on the Impact of COVID suffers direct impact of the dimension Agreement with the Measures during the Crisis (H5); the dimension Expectations on the Impact of COVID suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Information during the Crisis (H6); the dimension Expectations on the Impact of COVID suffers direct impact of the dimension Agreement with the Strategy during the Crisis (H7); and the dimension Expectations on the Impact of COVID suffers direct impact of the dimension Satisfaction with Mitigation Methods (H8).

Figure 4.

Crisis management: COVID-19 structural model. Source: elaborated by the authors.

Table 5.

Evaluation of the Structural Model.

7. Conclusions

The pandemic crisis we are facing calls for an urgent response from communities. The governmental demand is high; however, the scenario is complex and uncertain. An effective response requires interinstitutional and intergovernmental coordination [25,26] since each decision is implemented by a multiplicity of agents, who are at different hierarchical levels [4] and embrace different organizational values [27,28,29,30,31]. This research aimed to present a consistent framework—within its input’s factors—for crisis management in pandemic outbreaks. Thereby, this study sought to contribute to the crisis management literature in the public sector based on concepts as multi-level and collaborative governance. The importance of multi-level governance in responding to the pandemic crisis and the strategic planning as an instrument besides a preventive governance were approached. Through the crisis management: COVID-19 structural model, based on the Portuguese response to the new coronavirus, it was possible to assess the conditions and dynamic relationships in the “before” moments, “during” the combat, and the expected consequences “after” the pandemic, by the tested hypotheses. The Portuguese case presented in this paper suggests a robust and valid crisis management model. This model may be well translated for other countries with cultural proximity to the Portuguese culture, for instance Portuguese speaking countries such as Brazil, or geographical proximity to Portugal as, for instance, Spain. The authors, nevertheless, advise readers to exert some restraint on the extrapolation of the results, as governance systems and traditions can vary a good deal from country to country. This model has an extensive utility, since it can be implemented in future crises, and it is also possible to implement the proposed model in a greater variety of public service areas. Future studies should also focus on the importance of coordination as one of the most important areas in crisis management, narrowing the scope of analysis from the broad, macro understanding of the research problem presented on this paper. Another improvement future studies should consider is the distinction between internal and external stakeholders in order to better understand any emerging differences in the model regarding these two categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.A.R.C. and I.d.O.M.; methodology, P.M.A.R.C.; software, P.M.A.R.C., I.d.O.M., S.P.M.P. and I.S.; validation, P.M.A.R.C., I.d.O.M., S.P.M.P. and I.S.; formal analysis, P.M.A.R.C. and S.P.M.P.; investigation, P.M.A.R.C. and I.d.O.M.; resources, P.M.A.R.C., I.d.O.M., S.P.M.P. and I.S.; data curation, P.M.A.R.C., I.d.O.M., S.P.M.P. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.A.R.C., I.d.O.M. and S.P.M.P.; writing—review and editing, P.M.A.R.C. and S.P.M.P.; visualization, P.M.A.R.C.; supervision, P.M.A.R.C.; project administration, P.M.A.R.C.; funding acquisition, P.M.A.R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Unit funded by Portuguese National Funds through FCTFundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia under project UID/00713/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hale, T.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19 (Version 7.0). Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper. 2020. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/variation-government-responses-covid-19 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Losifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Penny, M. Transmission dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak and effectiveness of government interventions: A data-driven analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Mendes, I.O.; Pereira, S.P.M.; Subtil, I. The Combat against COVID-19 in Portugal: How State Measures and Data Availability Reinforce Some Organizational Values and Contribute to the Sustainability of the National Health System. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, P. Twenty years of multi-level governance: “Where Does It Come From? What Is It? Where Is It Going?”. J. Eur. Public Policy 2013, 20, 817–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G. Structural Policy and Multilevel Governance in the EC. In The State of the European Community; Cafruny, A., Rosenthal, G., Eds.; Lynne Rienner: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 391–440. [Google Scholar]

- Piattoni, S. Cohesion policy, multilevel governance and democracy. In Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU; Piattoni, S., Polverari, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thielemann, E.R. Institutional limits of a ‘europe with the regions’: EC state-aid control meets German federalism. J. Eur. Public Policy 1999, 6, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, A.; Eberlein, B. The Europeanization of regional policies: Patterns of multi-level governance. J. Eur. Public Policy 2000, 7, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.F.; Feiock, R.C. Applying an Institutional Collective Action Framework to Investigate Intermunicipal Cooperation in Europe. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, S.A.; Jung, K.; Li, X. Grass-Root Organisations, Intergovernmental Collaboration, and Emergency Preparedness: An Institutional Collective Action Approach. Local Gov. Stud. 2015, 41, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayilov, O.; Andrew, S.A. Effect of Natural Disasters on Local Economies: Forecasting Sales Tax Revenue after Hurricane Ike. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2016, 15, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Siebeneck, L.; Arlikatti, S.; Andrew, S.A. Using provincial baseline indicators to model geographic variations of disaster resilience in Thailand. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 955–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, K.; Bulkeley, H. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2013—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.L.; Pan, G.; Devadoss, P.R. E-Government Capabilities and Crisis Management: Lessons from Combating SARS in Singapore. MIS Q. Exec. 2005, 4, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.J. A strategic approach to managing crises. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroff, I.I.; Shrivastava, P.; Udwadia, F.E. Effective crisis management. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1987, 1, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, R. Foundation and History of the PDSA Cycle. Associates in Process Improvement-Detroit (USA). 2009, pp. 2–9. Available online: https://docplayer.net/21908816-Foundation-and-history-of-the-pdsa-cycle.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Poister, T.H. The future of strategic planning in the public sector: Linking strategic management and performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hatry, H. Performance Measurement: Fashions and Fallacies. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2002, 25, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Protection Authority. Available online: http://www.prociv.pt/en-us/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Mendes, I.O.; Pereira, S.P.M.; Subtil, I. Impacto do COVID-19. Available online: https://rebrand.ly/v84pog1 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Mendes, I.O.; Bilhim, J.A.F. Collaboration Networks as a Factor of Innovation in the Implementation of Public Policies. A Theoretical Framework Based on the New Public Governance. Lex Hum. 2019, 11, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Mendes, I.O.; Bilhim, J.A.F. The Importance of Collaboration and Cooperation as an Enabler of New Governance at the Local Level: A Comparative Analysis. Lex Hum. 2019, 11, 110–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bilhim, J.F.A.; Correia, P.M.A.R. Differences in perceptions of organizational values of candidates for top management positions in the State’s Central Administration. Sociologia 2016, 31, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Bilhim, J.F.A. Differences in perceptions of organizational values of public managers in Portugal. Braz. J. Public Adm. 2017, 51, 987–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, P.; Mendes, I.; Freire, A. The Importance of Organizational Values in Public Administration: A Case Study Based on the Workers’ of a Higher Education Institution Perception. Rev. Clad Reforma Y Democr. 2019, 73, 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, P.M.A.R.; Pereira, J.N. Perceptions of organizational values in the Portuguese Armed Forces: Proposal for a theoretical-methodological model. Public Sci. Policies 2018, 4, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.; Pereira, J. The recent history of research on public values as told by google scholar: Publications in portuguese and spanish in the 20th and 21st centuries. Rev. Simbiótica 2017, 4, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).