Abstract

Universities have become more entrepreneurial organisations in the past decades. However, the entrepreneurial competences needed for driving societal change have not been largely discussed in research literature. This paper sought to examine entrepreneurial staff competencies in the context of universities of applied sciences. A single case study from Finland, Tampere University of Applied Science, was selected. As the case institution has systematically developed an entrepreneurial strategy, the aim was to examine how entrepreneurial thinking and actions at individual and organisational levels were realised. The quantitative study involved 17 supervisors and 39 employees, and the survey took place in the Spring of 2020. The results indicate that the entrepreneurial strategy has been successfully implemented. Although both supervisors and employees evaluate themselves and the organisation to be entrepreneurial, internal communication should be further developed. Especially the provision of constructive feedback to support self-efficacy and self-esteem should be highlighted. As previous studies have stressed the challenges of integrating entrepreneurial behaviour in a ‘traditional’ academic context, these results provide insights for universities aiming to implement an entrepreneurial strategy, stressing psychological factors in the development of entrepreneurial competencies. Furthermore, we introduce a new theoretical approach to the discussion on the entrepreneurial university based on entrepreneurial competences.

1. Introduction: Towards Entrepreneurial Organisation

Over the past decade, there has been a clear shift towards strengthening organisational culture through entrepreneurial competencies. The overarching aim to reinforce these competencies reflects the many recent socio-economic and politic changes in the society: In all sectors, new solutions for promoting innovation and creativity, aligned with social and economic well-being, are constantly been sought out [1,2]. However, investments in new knowledge do not automatically lead into increased competitiveness and growth, but the focus should be on commercialization and encouraging entrepreneurship [3], especially by strengthening the transition from ‘latent’ to ‘emergent’ entrepreneurship. In the latter, the entrepreneur has the needed strategic and managerial capacity to pursue change by turning knowledge spillovers into economic growth [4]. According to Chandler and Jansen [5] these entrepreneurial competencies are indeed fundamental for different kinds of organisations, so that they can perform and succeed well. In the context of corporate entrepreneurship, the development of an entrepreneurial organisation has been defined as a process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organisation, together create a new organisation or investigate renewal or innovation within that organisation [6]. In practice, as argued by Bosman, Grard, and Roegiers [7], an individual, competence-based approach supporting entrepreneurship has become the most common structure for (staff) training programs and courses, e.g., in the field of entrepreneurial behaviour.

In parallel to the emergence of research literature focusing on entrepreneurial competencies, a lot has been written about universities’ entrepreneurial and societal missions as well as their increasingly emphasised role in innovation systems. Hitherto, the academic literature has addressed the phenomenon through a myriad of overlapping concepts, including ‘entrepreneurial university’ [8], ‘engaged university’, see, e.g., [7,8], and the university ‘third mission’, see, e.g., [9,10], all of which widely refer to a range of different activities beyond education and research. These new roles played by universities have been increasingly articulated in higher education policies [11], which strengthen the university’ role in the knowledge economy [12]. While many reform agendas have been created to support efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability within higher education institutions, e.g., by developing demand-based interdisciplinary research with businesses and industry partners [13], the entrepreneurial competencies needed for carrying out such initiatives has been less discussed in the context of higher education studies. Yet previous studies have indicated that reinforcing entrepreneurship education as well as entrepreneurial attitudes within the academic communities can be beneficial for producing highly skilled future entrepreneurs, allowing higher education systems to make a contribution to regional and national development [14].

It is obvious that both organisational and individual capacities to cope with uncertainty are increasingly important also in the higher education sector, especially in the time of the COVID-19 crises, which has challenged everyday operations of the higher education sector. Entrepreneurial capacities have been associated with organisational and individual abilities to cope in an uncertain and complex environment [15] in the context of entrepreneurial university [8]. As some scholars have even argued, that ‘entrepreneurialism’ can only be linked to individuals instead of organisations [16], and our paper seeks to generate in-depth knowledge on the entrepreneurial competencies needed for organisational change in the context of higher education institutions. Through a quantitative analysis based on a staff survey conducted in the Tampere University of Applied Sciences, we produce new insights on the different competence areas effectively driving change towards an entrepreneurial organisation.

The paper is structured as follows: Firstly, in the literature review, we summarise the shift towards entrepreneurial universities since the late 1990s, after which we present the chosen framework for assessing entrepreneurial competencies. Secondly, we provide an overview on the case study and a discussion on the methods. Thirdly, we present the results from the questionnaire. Lastly, we discuss on the key findings and make suggestions for further research.

2. Entrepreneurial Competencies Driving Organisational Change

2.1. From Entrepreneurial Universities to Entrepreneurial Competencies

It has been argued that ‘entrepreneurial activity’ can have a positive impact, not only to economic growth, but also to wealth and productivity [17]. Since the late 1990, the debate on the rise and impact of entrepreneurialism have been on the increase, also in regard to public organisations such as universities. In Clark’s original conceptualisation of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ [8], ‘entrepreneurialism’ refers primarily to higher education institutions’ internal dynamics and strategies [18]. The concept has been described as a framework for understanding organisational changes as ‘dynamic, continuous, and incremental processes’ based on collegial entrepreneurialism rather than direct top-down initiatives and/or management strategies [18]. However, the entrepreneurial university also underlines the commitment of the universities’ personnel, being that reinforcing entrepreneurship demands ‘department ownership’ [8]. This can lead to the development of ‘enterprise culture’, which is open to change, as well as both creation and exploitation of innovations among students and staff members [14].

Overall, the research literature discussing entrepreneurship underlines that raising entrepreneurial efficacies will also raise perceptions of venture and entrepreneurial intentions in general [19]. Additionally, according to Wilson, Kickul, and Marlino [20] self-efficacy may play an important role in shaping and/or limiting perceived career options. Moreover, Neto et al. [21] found out in their study that self-efficacy actually predicts entrepreneurial behaviour of individuals. Thus, self-efficacy plays a key role in organisations’ development, although it has been more associated with individual learning. As an example, Bandura [22] explains that students’ beliefs about their efficacy regulate their learning, motivation, and mastering accomplishments. Moreover, teachers’ beliefs about their personal efficacy and capacity to motivate and promote learning can affect the types of learning environments they create in practice for their students, as well as the level of academic progress they can accomplish in cooperation with their students. Furthermore, faculties’ and schools’ institutional beliefs about their collective instructional efficacy can contribute significantly to the schools’ academic achievements and entrepreneurial activities as ‘institutional determinants’ increasing student entrepreneurship [14]. According to Borba [23,24], students and staff with high self-esteem and self-efficacy usually perform well, and they can better promote the development of their organisation towards goal-orientated actions, wider success, and collaborations.

Being so, we conclude that self-efficacy is not only an individual process, but it can be understood as a phenomenon formulated both through individuals and groups. Thus, self-efficacy, as a shared resource driving individual and organisational entrepreneurial competencies, is also our starting point for measuring the entrepreneurial organisation from the staff’s perspective. In the following section, we present the framework for assessing entrepreneurial competencies within the context of higher education.

2.2. Framework for Assessing Entrepreneurial Competencies

According to Seikkula-Leino [25], the ground of entrepreneurial learning and behaviour involves a range of individual different competencies, such as: (1) Trust and respect, (2) each person is unique, (3) open interaction, (4) approaching goals and new opportunities, (5) competence and success oriented behaviour, (6) and working life, networks, and development. Seikkula-Leino’s approach builds on Borba’s [23,24] psychological and educational work focused on the development of self-esteem and self-empowerment, which can also be formed through group activities supporting staff self-esteem and self-efficacy—see also [22,26,27]—as well as through experiential learning, see, e.g., [28]. These elements, in combination, are also inherent in entrepreneurship research, e.g., through opportunity creation on both individual and organisational levels, see, e.g., [29,30].

Building on Seikkula-Leino’s [25] and Ruskovaara et al.’s [31] previous work, we have chosen the following framework to assess entrepreneurial competencies (see Table 1) in the context of higher education. These entrepreneurial competencies form the theoretical basis of the research and designing of the survey, which was conducted for finding out how these entrepreneurial competencies are reflected in the thinking and everyday functions of both managers and employees within the chosen case university.

Table 1.

Description of entrepreneurial competencies driving organisational change.

3. Case Study Overview

The Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) actively conduct collaborative RDI activities with a range of different stakeholders, but these external linkages tend to be more often results of bottom-up initiatives rather than institutional bridging mechanisms (e.g., [32]). However, the Finnish UASs are considered to be significant promoters of innovation, particularly through their group-based and networked learning environments [33]. A strong entrepreneurial competence base of the UAS staff members could further reinforce the establishment of linkages with external partners and other collaborative initiatives [14]

The chosen case institution, namely the Tampere University of Applied Sciences (TAMK), is one of the biggest UASs in Finland, with well-established working life connections and a strategic aim to develop towards entrepreneurial organisation. It is a multidisciplinary UAS with 13,000 students and about 800 staff members, offering a range of BA and MA degree programmes in health and wellbeing, business studies, and technology. It’s mission statement underlines the importance of developing collaboration with external partners and higher education’s societal role: ‘Our strong orientation towards working life ensures the best learning possibilities for our students. Furthermore, we are involved in research, development and innovation which specifically target the development needs of working life.’ TAMK is also part of the newly established Tampere Higher Education Community, following the merger of the former University of Tampere and Tampere University of Technology in 2019, thus it represents a unique case in the Finnish UAS scene.

3.1. Research Design, Questions, and Target Group

Previous studies imply that the development of an entrepreneurial culture is not straightforward in an academic context [34]. This is argued, in particular, in the previous studies of Seikkula-Leino et al. [35,36] and Devici and Seikkula-Leino [37], discussing how entrepreneurship has been integrated into teachers’ education. These studies underline that especially the development of entrepreneurial competencies and skills among the higher education staff members is not uncomplicated. These findings provided a profitable starting point for our study, allowing us to build on existing viewpoints related to entrepreneurial competencies in the context of higher education. Thus, we wanted to further investigate how different staff members working in a university perceive entrepreneurialism within the organisation, and how it could be reinforced while also examining individual employees’ assessments of their entrepreneurial capacities. Furthermore, the entrepreneurial competencies of the supervisors were studies through both staff’s evaluations and their own assessments.

It has been argued that the first step towards driving (organisational) change successfully is to ensure that the employees themselves have assimilated the strategic reform [35,36,37], thus we decided to limit our research to the academic personnel. The research questions of this study are the following:

- 1.

- How are the entrepreneurial competencies assessed in a (higher education) organisation?

- 1.1

- How do the employees evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation?

- 1.2.

- How do the supervisors evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation?

- 1.3.

- Are there any differences between the employees’ and supervisors’ evaluations of their organization’s entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.

- How do personnel self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.1.

- How do the employees self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.2.

- How do the supervisors self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.3.

- Are there any differences between the employees’ and the supervisors’ self-evaluations of the entrepreneurial competencies?

- 3.

- How are the entrepreneurial activities of the supervisors visible in the organisation?

- 3.1.

- How do the employees evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their supervisors?

- 3.2.

- How do the employees’ evaluations of the supervisors’ entrepreneurial competencies accord with the supervisors’ self-evaluations of their entrepreneurial competencies?

As we explained above, the target group of the study includes different staff members working in higher education institutions (HEI). TAMK provided an interesting case HEI, as it has a strategic aim to strengthen entrepreneurial skills and competencies. Overall, the case study provided a suitable platform for investigating how these organisational goals can be detected in individual staff members’ attitudes and beliefs. As Cohen, Manion, and Morrison [38] argue, the generalisability of such single experiments (e.g., case and pilot studies) can be extended through replication or multiple experiment strategies, allowing case studies to contribute to the development of a growing pool of data for eventually achieving a wider generalisability. Thus, the results obtained from our pilot study contribute to ‘analytic’ rather than ‘statistical’ generalisation to build on further studies.

The survey was conducted in Spring 2020 by sending the questionnaire to 198 respondents working at Tampere University of Applied Sciences by email. This specific group of staff member has been actively or, to some extent, actively involved in the development of an entrepreneurial organisation in TAMK. Altogether, 56 of the responses were received from 17 supervisors and 39 employees. In total, our response rate in this random sampling is about 29%, which can be considered reasonably good in this kind of quantitative research setting.

3.2. Assessment Tools and the Data Analysis

In our previous studies, the assessment tools have been successfully used in the corporate world (e.g., Wihuri Group, Property Management Association, Raisio, pharmacies etc.) between 2012–2015. These individual studies confirm the reliability of the assessment tools; as an example, Cronbach’s alpha levels varied in different categories between 0.67–0.96, which can be interpreted as ‘satisfactory’ [39]. Minor changes were made to the metrics to increase its usability in the context of higher educational institutions; the assessment tools utilised in this study are based on Seikkula-Leino’s [25] approach on entrepreneurial behaviour presented in the previous section. In addition, the SKILLOON student assessment tools, based on similar theoretical approach, were utilised in the development of the tools for this study. SKILLOON (www.skilloon.com), is an official education concept of Education Finland supported by the Finnish National Board of Education. SKILLOON involved assessment tools, entrepreneurial activities, and student mentoring programmes. SKILLOON is created in research cooperation with schools and universities, and it is used for education and research purposes.

The assessment tool targeted to personnel, the SKILLOON staff assessment survey, had four different assessment tools, each of which included six sets of research questions. The first assessment tool was targeted to both employees and supervisors, and it contained an evaluation of the different (entrepreneurial characteristics) of the organisation. The second and third assessment tool focused on self-assessment of the employers and the supervisors, and finally, the fourth assessment tool was targeted to employers, who assessed the employers. Each of these four sections contained between five to seven questions of claims. The respondents specified their level of agreement or disagreement on a symmetric agree/disagree scale between 1–10, whereas 1 meant that the respondent fully disagrees with the claim, and 10 that the respondent fully agrees. Each competence area forms an individual summation notation, by calculating each respondents’ mean for each set of questions.

In order to assess the quality and representativeness of the data, we inspected the pattern and frequencies of missing values. One respondent was excluded from the analysis in the supervisors’ self-evaluation section due to non-response. In addition, three respondents (employees) lacked an answer to one question in different sections, and these were treated as missing values in the analysis. The examples of survey questions and claims are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

The examples of SKILLOON staff assessment tools and claims.

4. Results

In this section, we present the key results from each of the four assessment tools of the survey.

4.1. How Are the Entrepreneurial Competencies Assessed in A (Higher Education) Organisation?

4.1.1. How Do the Employees Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

The sum variables were formed from the responses of 39 employees. The averages of the sum variables in every assessment tool are quite high, as we can see from Table 3. The highest average is in assessment tool ‘Trust and respect within the working community’ and the lowest average is in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. Only the lowest average in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’ is slightly smaller than in other assessment tools. This could be explained by the fact that in this assessment tool, one of the questions was reversed—there might be people that haven’t noticed this. On the other hand, there is a reversed question also in assessment tool ‘Open interaction’, but there was no visible deviation within the results. Overall, the employees considered their organisation to be rather entrepreneurial.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the organisation, n = 56.

4.1.2. How Do the Supervisors Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

The sum variables were formed from the responses of 17 supervisors. The highest average is in assessment tool ‘Working life, networks, development’ and the lowest average is in assessment tool ‘Each person is unique’. The averages of every six sum variables were high and they were all at the same level. This can be verified from Table 3. In general, the supervisors highly evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation.

4.1.3. Are There Any Differences between the Employees’ and the Supervisors’ Evaluations of the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

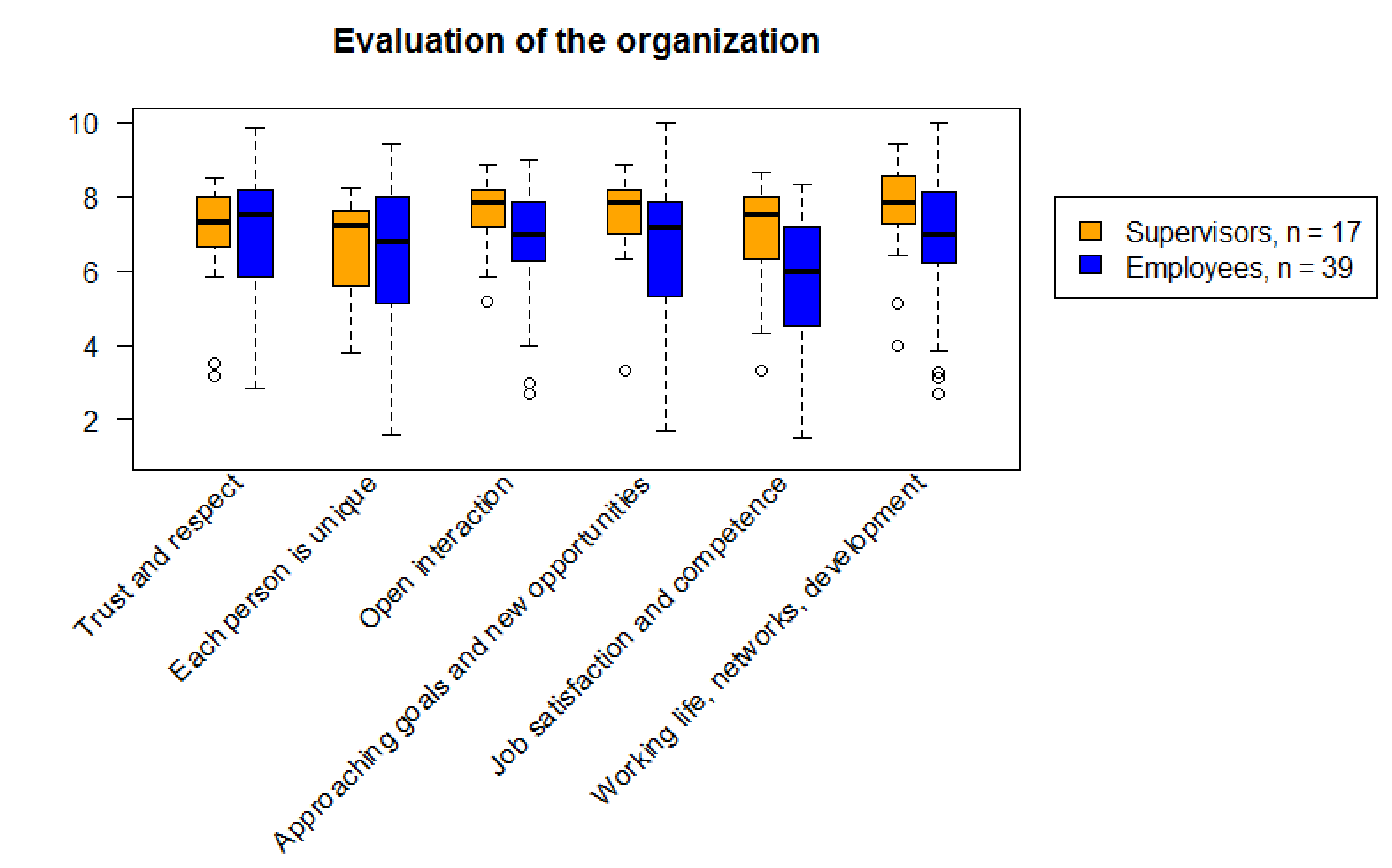

Even though the averages of supervisors are slightly higher than the averages of employees in each assessment tool (Table 3), the boxplots in Figure 1 indicate that there is more dispersion in the responses of employees. Moreover, the employees have more extreme responses. In these boxplots, the orange and blue colours are for supervisors and employees, respectively. This could be explained by the fact that there were significantly more employees (n = 39) than supervisors (n = 17) among the respondents. Both the highest and the lowest averages of supervisors and employees are in different assessment tools. It was examined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) whether there were differences between the responses of supervisors and employees. The p-values in each assessment tool are in Table 3. Thus, based on these p-values, there was a statistically significant difference in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’ between the answers of supervisors and the answers of employees: The supervisors evaluate the entrepreneurial competences in this assessment tool significantly higher than the employees.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the organisation by each competency area, n = 56.

Altogether, the personnel’s perception on the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation is quite good, and there are no significant differences between the means of assessments of supervisors and the means of assessments of employees, except in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. However, in this assessment tool, the supervisors evaluate the competencies of their organisation to be higher than the employees.

4.2. How Do the Personnel Evaluate Their Own Entrepreneurial Competencies?

4.2.1. How Do the Employees Self-Evaluate Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

The sum variables were formed from the answers of 39 employees. The averages in every assessment tool are very high as we can see from Table 4. The highest average is in assessment tool ‘Open interaction’, and the lowest average is in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. In general, the employees evaluate themselves to be very entrepreneurial.

Table 4.

Self-evaluation, n = 55.

4.2.2. How Do the Supervisors Self-Evaluate Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

The sum variables were formed from the responses of 16 supervisors, since one respondent among the supervisors did not answer any questions of the last two assessment tools. The averages are high or very high in all assessment tools, as we can see from Table 4. The highest average is in assessment tool ‘Trust and respect within the working community’, and the lowest average is in assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. The supervisors evaluate themselves to be very entrepreneurial.

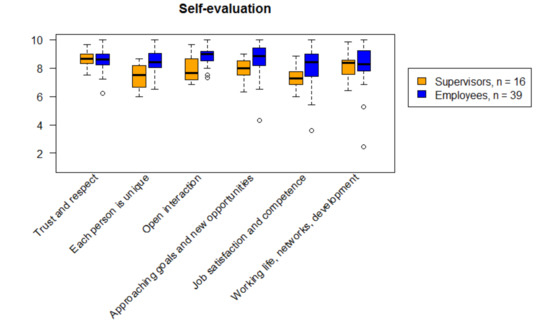

4.2.3. Are There Any Differences between the Employees’ and the Supervisors’ Self-Evaluations of the Entrepreneurial Competencies?

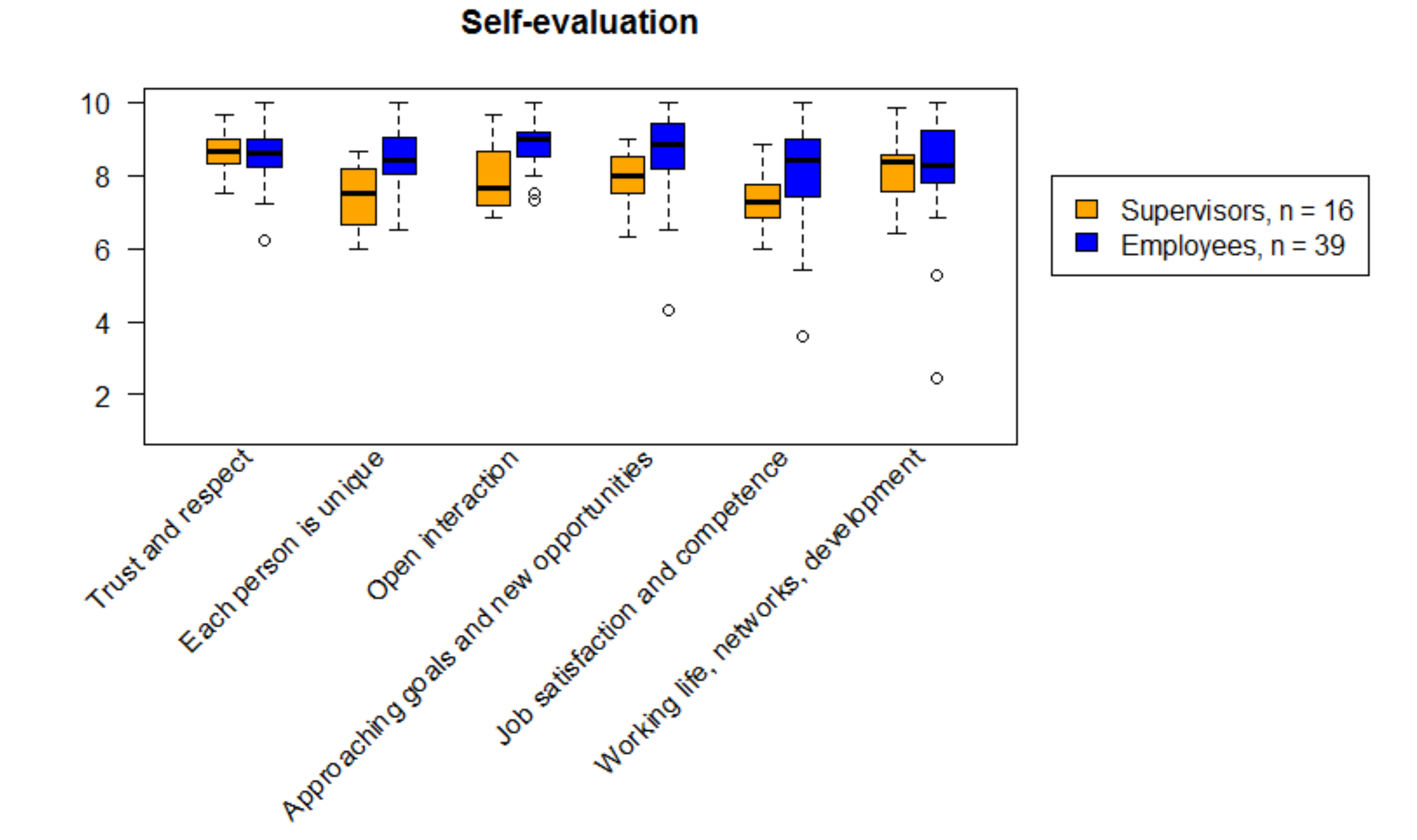

Based on these results, we conclude that both the supervisors and the employees evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies to be rather high. Considering the assessment tool ‘Trust and respect within the working community’, the supervisors seem to evaluate themselves higher than the employees based on the means. In all other assessment tools, the employees have higher means. The highest average of employees and the highest average of supervisors are in different assessment tools. On the other hand, the lowest average of employees and the lowest average of supervisors are in the same assessment tool ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. It was examined by analysis of variance whether there were differences between the means of supervisors’ answers and the means of employees’ answers in how they evaluate themselves. The differences are statistically significant in competency areas ‘Each person is unique’, ‘Open collaboration’, ‘Approaching goals and new opportunities’, and ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. In each of these competence areas, the TAMK’s employees seem to evaluate themselves higher than supervisors. The boxplots in Figure 2 also suggest the same conclusion obtained using statistical methods. By comparing Table 3 and Table 4, we can conclude that the personnel evaluate their individual entrepreneurial competencies to be higher than the collective capacities of the organization. This applies to every assessment tool.

Figure 2.

Self-evaluation by each competency area, n = 55.

4.3. How Are the Entrepreneurial Activities of the Supervisors Visible in the Organisation?

The supervisors’ self-evaluation and the employees’ assessment of the supervisors are both above average with overall means 7.89 and 6.34, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that TAMK has a good entrepreneurial competence in particular amongst its supervisors.

4.3.1. How Do the Employees Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Supervisors?

As summarised in Table 5, the employees evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their supervisors quite highly, with averages ranging from 5.97 to 7.14. The employees agree most in ‘Trust and respect within the working community’ and disagree most in ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. Both the maximum mean, 7.14, and the maximum median, 7.50, is in ‘Trust and respect within the working community’, and the lowest mean is in ‘Job satisfaction and competence’. Therefore, these assessment tools should be examined in more detail.

Table 5.

Employees evaluate supervisors, n = 39.

In the assessment tool ‘Trust and respect within the working community’, question 1. ‘As an employee I think that the management is reliable (e.g., keeps its promises)’ has a rather low dispersion, and the average of the question is 7.95, and the median is 8.0, which is a very good result. Thus, it can be concluded that the employees most often agree that the management is reliable. In ‘Job satisfaction and competence’, question 4. ‘As an employee I think that the management clearly states what is good in my work and what could be improved’ has the lowest score, a mean of 5.28, and median 5.00. The content of the question is worth paying attention to in the further development of the organisation.

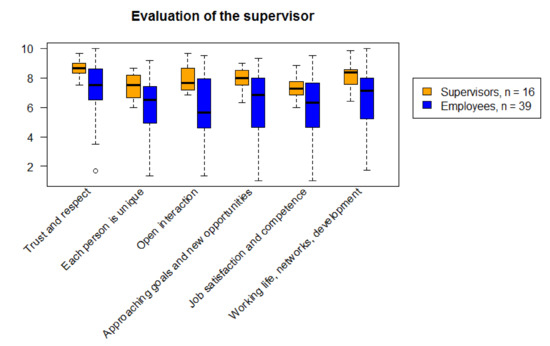

4.3.2. How Do the Employees’ Evaluations of the Supervisors’ Entrepreneurial Competencies Accord with the Supervisors’ Self-Evaluations of Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

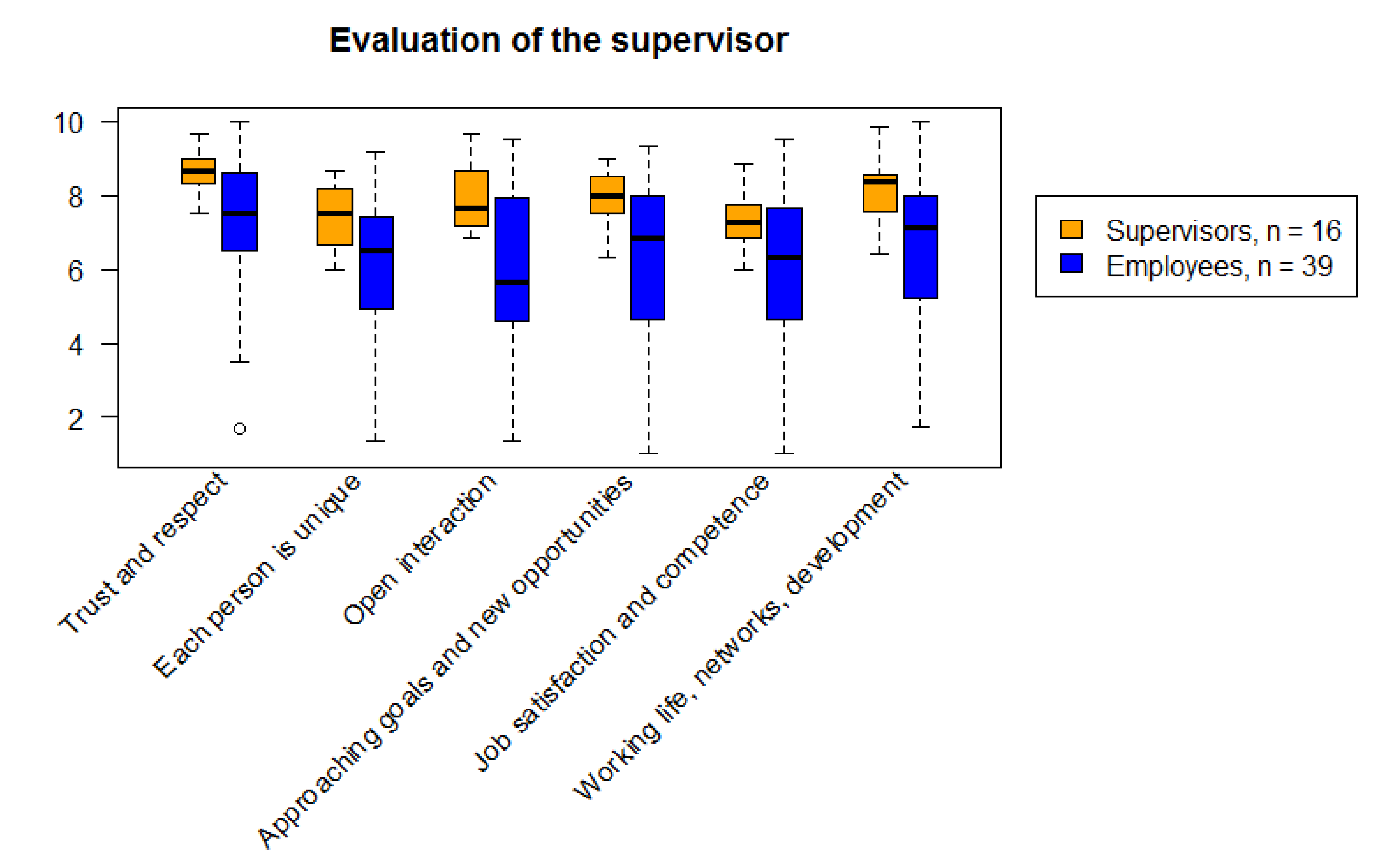

Supervisors evaluate their own entrepreneurial competencies to be higher compared to the employees’ assessment on the entrepreneurial competencies of the supervisors. This can be seen in each of the assessment tools (Figure 3). Once again, the employees’ responses are more dispersed, which may be due to the fact that there are significantly more employees (n = 39) than supervisors (n = 16) among the respondents. One supervisor lacked responses to self-evaluations assessment tools 5 and 6, reducing n to 16.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the supervisor by each competency area, n = 55.

Otherwise, the results of sections ‘Employees evaluation of supervisors’ and ‘Supervisors self-evaluation’ are parallel in all the competence areas. The responses summarised in Table 6 indicates that ‘Trust and respect within the working community’ has the highest mean in both self-evaluation and evaluation of the supervisors, 8.63 and 7.14, respectively, while ‘Job satisfaction and competence’ has the lowest, 7.28 and 5.97, respectively.

Table 6.

Comparison of the supervisors’ self-evaluation and employees evaluating supervisors, n = 55.

Because of unequal variances and unbalanced data, the comparison of the two respondent groups’ means was done using Welch’s f-test. The differences in group means are statistically significant (see Table 6). Although in some sum variables the group means differed a lot, all are above 5.5, which can be considered a rather good result. But it should be noted that the average differences in the groups are at their highest 1.84 (‘Open interaction’), which is a big deviation and may need some further examination. However, this can be partly explained by the different group sizes of the respondents, and perhaps the data is somewhat biased if, for example, more satisfied supervisors and less satisfied employees have responded to the survey.

When examining assessment tool ‘Open interaction’ question by question, it can be seen that the results are parallel, but the average responses of employees are, on average, almost two points lower than those of supervisors in questions 2–6. It can be concluded that supervisors and employees have different views on how well management invests in open interaction within the organisation. Also, the supervisors evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies in open interaction to be much higher than the employees do.

4.4. Consistency of the Assessment Tools

Internal consistency of the assessment tools was measured with Cronbach’s alpha. These assessment tools have been used a lot, and they have been developed along the way. Furthermore, as presented before, they have been proven to work well in assessing entrepreneurial competencies in the context of private organisations. Table 7 indicates that all the alphas are good or excellent, ranging from 0.60 to 0.95, except in ‘Employees self-evaluation’, which is a new section. In assessment tools ‘1. Trust and respect within the working community’, the alpha is 0.47, and in ‘3. Open interaction’, the alpha is 0.52. However, considering that there are only 39 observations and that this section is in use for the first time, the alphas are sufficient for using the tool. This implies, that there are two questions within the two assessment tools that need to be reformulated for further use. There is also a new assessment tool ‘Working life, networks, development’, but it works very well, the alphas being between 0.79 and 0.95. Overall, there are a total of about 120 statements in all of our research metrics. Therefore, we do not consider this to compromise the results of the study, as only a few statements are not completely ideal. However, further examination of the tool is still needed.

Table 7.

Measuring the consistency of the assessment tools by Cronbach’s alpha.

Overall, we assess that the reliability and validity of the assessment tools are on a sufficient level for responding to the set research questions [39]. The phenomenon has been examined through a multidisciplinary approach, and with a range of different assessment tools and two different respondent groups. However, there is still room for further development of the assessment tools and research design, both of which are discussed in the following section together with the obtained results.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper, our aim was to investigate how entrepreneurial thinking and actions on both the individual and organisational levels were realized in practice after the case university’s strategy reform. Our approach enabled analysing what kind of entrepreneurial competences are needed in the context of higher education to drive organisational change, which can have also a significant socio-economic impact in the long-term. Overall, the results obtained from our pilot study are positive in regard to the activities of the organisation and the individuals, both of which were estimated to be entrepreneurial. In regard to previous studies [34,35,36,37], it can be estimated that Tampere University of Applied Sciences has succeeded in implementing an efficient entrepreneurship strategy across the board, although there are also areas in which further development is needed.

The results indicate that the supervisors tend to estimate their entrepreneurial competencies higher than the employees. This implies, that the entrepreneurial strategies of the organisation are well communicated to different management levels, while the employees are less engaged and equipped to contribute to transformative change towards entrepreneurial organisation to support entrepreneurial attitudes within the university community [14]. However, as previous studies on the ‘entrepreneurial university’ have argued, top-down initiatives or organisational strategies alone are not sufficient for drivers of organisational change, but collegial entrepreneurialism should be supported through collegial entrepreneurialism [18]. The literature has also emphasized the role of the universities’ personnel [8] in creating an ‘enterprise culture’. Being so, identifying and further development of the entrepreneurial competencies among staff members would facilitate higher education institutions’ path towards entrepreneurial organisations. As a practical recommendation, more attention could be paid to interaction and personal feedback of the employees. This is also likely to provide valuable feedback to the HR of organizations and the development of targeted management training programmes with an aim to equip the managers with new skills for providing constructive feedback, which supports open communication and raise further discussion on the organisational goals. Undoubtedly, the development of an entrepreneurial organisation also emphasises psychological starting points for meeting people, and thus also for strengthening the self-efficacy of individuals [26,27].

On the other hand, the number of participants in the pilot study is limited. The question also arises as to whether those persons who, in principle, have been more oriented towards entrepreneurialism, have responded to the survey. That is why, in the future, even more extensive organisational measurements are required to assess the entrepreneurial capacities effectively. Admittedly, qualitative research integration would also have the potential to generate a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. Similar measurements, also in different sectors and societal contexts, would provide more in-depth information on the extent to which entrepreneurialism appears as a contextual feature. Based on this knowledge, it would be possible to create even more customised development models or training programmes targeted for the development of an entrepreneurial organisation (e.g., management training and HR development).

Previous studies imply that the entrepreneurial culture is not given in the academic context [34,35,36], and thus future research is still needed in the area. Moreover, many studies aim to investigate the entrepreneurial culture within particular target groups (e.g., teachers) representing a part of the university personnel, although a more holistic view to the development of positive attitude towards entrepreneurial capacities can also increase student entrepreneurship [14] Being so, our research is even ground-breaking in the sense that we have not found any previous studies with a similar starting point—namely, identifying both employees’ and supervisors’ perceptions of their personal and their organisation’s entrepreneurial capacities and exploring these aspects simultaneously.

As a part of the survey, employees also evaluated their supervisors. To that extent, our different assessment tools provide unique information on the phenomenon. The tools themselves triangulate [38] the manifestation of entrepreneurialism in an organisation through a variety of ways, even though our metrics provide only quantitative information. Furthermore, our tools are also based on an interdisciplinary premise integrating entrepreneurship, psychology, and behavioural science research, which contributes to the knowledge base of entrepreneurship research by ‘borrowing’ theoretical approaches from other research fields [40]. In this way, we have triangulated the phenomenon based on academic discussion within different disciplines, such as higher education studies.

In the future, we will also emphasise organisational development based on the Seikkula-Leino’s competency model [25]. With these indicators, we will be able to study further, e.g., the effectiveness of different national and institutional development programmes. We estimate that our organisational development concept based on previous studies on entrepreneurial competencies (SKILLOON tool) could potentially contribute to the development of different entrepreneurial organisations and entrepreneurial culture, which is permissive, appreciative, and supports feelings of success and self-efficacy in all levels of the organisation. Furthermore, this approach can help to create a wider understanding of the theoretical basis of entrepreneurial organisation and its culture by identifying the elements that support effective managerial and strategic capacities to transform knowledge into entrepreneurial activity [3]. This type of culture does not only create a basis for entrepreneurial activity, but, at the same time, it promotes the wellbeing of management and employees, creating a solid foundation for building a sustainable organisational culture whilst also supporting student entrepreneurship [14]. Developing such a culture would contribute to the ability to operate more stably and in a more agile manner in a global and rapidly changing environment. It would also indirectly contribute to the strengthening of a sustainable society, in which people solve the challenges ahead and even find new and unpredictable innovative openings for the development of quality of life—allowing us to put into practice the latest global strategies driving entrepreneurship within the society (see, e.g., [1,2]).

6. Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated for this study will not be made publicly available because of the sensitive nature of the questions. All study participants were assured that the data will remain confidential and will not be shared. Therefore, all requests concerning the access to the dataset should be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.-L. and M.S.; methodology, J.S.-L.; software, J.S.-L.; validation, J.S.-L.; formal analysis, J.S.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.-L. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S.-L. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lackeus, M.; Lundqvist, M.; Middleton, K.W.; Inden, J. The Entrepreneurial Employee in Public and Private Sector. What, Why, How; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2020 Global Report, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2020.

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Resolving the Knowledge Paradox: Knowledge-Spillover Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Belitski, M.; Audretsch, D. From Latent to Emergent Entrepreneurship: the Knowledfe Spilloever Construction Circle. J. Technol. Transfer 2020, 45, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; Jansen, E. The Founder’s Self-Assessed Competence and Venture Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1992, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfring, T. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Venturing, ISEN International Studies in Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, C.; Grard, F.-M.; Roegiers, R. Quel Avenir pour les Compétences? De Boeck: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, C.; Hirth, M. A History of Change in the Third Mission of Higher Education: The Evolution of One-way Service to Interactive Engagement. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2005, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zomer, A.; Benneworth, P.; Boer, H.F. The Rise of the University’s Third Mission. In Reform of Higher Education in Europe; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vorley, T.; Nelles, J. Building Entrepreneurial Architectures: A Conceptual Interpretation of the Third Mission. Policy Futur. Educ. 2009, 7, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, B.; Maharajh, R.; Schmoch, U. New Activities of Universities in Transfer and Extension: Multiple Requirements and Manifold Solutions. Sci. Public Policy 2009, 36, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Ranga, M.; Benner, M.; Guaranys, L.; Maculan, A.-M.; Kneller, R. Pathways to the Entrepreneurial University: Towards a Global Convergence. Sci. Public Policy 2008, 35, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S.; Guerrero, M.; Noguera, M.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Institutional Determinants of Student Employer Entrepreneurs at Catalan Universities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, B.; Hannon, P. Towards Entpreneurial University? Int. J. Entrep. Educ. 2006, 4, 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, I. Living in an ‘Entrepreneurial’ University. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 2004, 9, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N. Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth: What do We Know and What so We Still Need to Know? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, G.; Stensaker, B. Bringing Organisations and Systems Back Together: Extending Clark’s Entrepreneurial University. High. Educ. Q. 2017, 71, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Hsu, D.; Powell, B.C. Self-efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intentions, and Gender: Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Longitudinally. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, R.; Rodrigues, V.; Stewart, D.; Xiao, A.; Snyder, J. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Behaviour among K-12 Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 72, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M. A K-8 Self-Esteem, Curriculum for Improving Student Achievement, Behavior and School Climate; Jalmar Press: Torrance, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Borba, M. Staff Esteem Builders: The Administrator’s Bible for Enhancing Self-Esteem; Jalmar Press: Torrance, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seikkula-Leino, J. (submitted): Developing Theory and Practice for Entrepreneurial Learning—Focus on Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Adolescents. In Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewoord Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credits, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskovaara, E.; Rytkölä, T.; Seikkula-Leino, J.; Pihkala, T. Building a Measurement Tool for Entrepreneurship Education: A Participatory Development Approach. In Entrepreneurship Research in Europe Series; Edwaerd Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maassen, P.; Spaapen, J.; Kallioinen, O.; Keränen, P.; Penttinen, M.; Wiedenhofer, R.; Kajaste, M. Evaluation of Research, Development and Innovation Activities of Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences; The Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council: Helsinki, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen, J. Innovation Pedagogy for Universities of Applied Sciences. Creative Educ. 2011, 2, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ilonen, S. Entrepreneurial Learning in Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education; Painosalama: Turku, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seikkula-Leino, J.; Satuvuori, T.; Ruskovaara, E.; Hannula, H. How do Finnish Teacher Educators Implement Entrepreneurship Education? Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikkula-Leino, J.; Ruskovaara, E.; Hannula, H.; Saarivirta, T. Facing the Changing Demands of Europe: Integrating Entrepreneurship Education in Finnish Teacher Training Curricula. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 11, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, I.; Seikkula-Leino, J. A Review of Entrepreneurship Education in Teacher Education. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2018, 15, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landström, H.; Harirchi, G.; Astrom, F. Entrepreneurship: Exploring the knowledge base. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).