Abstract

This study aimed to develop and carry out content validation, semantic evaluation, reproducibility, and internal consistency of a checklist designed to verify the sustainability indicators in foodservice. The preliminary version of the checklist was prepared based on the international standards ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 14000, ISO 14001, ISO 14004 and documents from the Sustainable Restaurant Association (SRA) Certification, Green Seal Certifications, and Green Restaurant Association (GRA) certification, in addition to the American Dietetic Association (ADA) position. Thirteen experts in the study topic performed the content validation and semantic evaluation of the checklist (a minimum of 80% agreement among experts and mean value ≥4 on a 5-point Likert scale were needed to keep the item in the instrument). After consensus was reached by the experts’ panel, two different researchers applied the checklist in 20 restaurants (at the same time, in the same place, without communication between them) for the analysis of reproducibility and internal consistency (Federal District, Brazil). The agreement among answers was verified by Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. The final version of the checklist consisted of 76 items, divided into three sections (1. water, energy, and gas supply; 2. menu and food waste; 3. waste reduction, construction materials, chemicals, employees, and social sustainability). The developed checklist was validated concerning the content, approved in the semantic evaluation, reproducible, and with good reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) > 0.9 and alpha > 0.672).

1. Introduction

The high demand for meals away from home and an increasing number of restaurants have expanded meal production. All steps involved in foodservice have a high financial and environmental cost that need to be rethought, especially concerning the environmental factor. This is due to a more substantial amount of discarded waste and the use of various natural resources [1,2,3,4]. Meal production is responsible for 80% of deforestation, 70% of the consumption of fresh water, and 30% of greenhouse gas emissions, being the most significant cause of the planet’s species biodiversity reduction [5]. Worldwide, the foodservice sector is considered the least sustainable among the economic sectors [6].

The Brazil is one of the top ten countries in food waste in the world. About 40 thousand tons of food goes to waste every day in Brazil, which is equivalent to 30% of everything that is produced [7]. Waste has enormous consequences for the environment, because with food waste, there is also water, land, energy, and transportation waste, among other services in the production of a meal [4]. Besides, the United Nations Organization [8] data state that the carbon footprint of food produced and not consumed in the world is estimated at 3.3 gigatons of carbon dioxide. This number puts food waste in third place among the largest CO2 emitters in the world; therefore, reducing waste is a way to mitigate environmental impact. Foodservice companies must be committed not only to the quality of the meals and their profits but also to social responsibility and sustainability [9].

Given the world panorama and the potential shortage of natural resources, the procedures for the production of more sustainable meals have increased the attention and consciousness of the people involved in out-of-home meals. Severe environmental problems, such as global warming, waste, and pollution, have also increased people’s consciousness of the environment and of the need for actions based on sustainability [10].

Regarding the environmental domain of sustainability, the adoption of sustainable practices in foodservice favors their recognition through audits and certifications. In North America and Europe, there are companies such as the Green Restaurants Association (GRA) and the Green Seal that carry out restaurant certifications to stimulate ecological sustainable restaurants [11,12]. In Brazil, a study suggested the use of the international environmental quality system IS0 (International Organization for Standardization) 14000, which sets standards in the development of environmentally sustainable actions [13], and another research suggests the use of Ecoinefficiency evaluation [14]. Although the ISO establishes guidelines for obtaining a certificate, presenting evaluation items, it does not specify “how” these items should be evaluated in foodservice, as well as the cost for the certification, making their use complicated.

For international certifications such as the Sustainable Restaurant Association (SRA), GRA or Green Seal, the evaluation criteria and items are not specific to the Brazilian context and legislations. For example, some items question air pollution through the use of cigarettes in the sector, and this behavior is already prohibited in Brazil. Additionally, these certifications evaluate the use of fluorescent bulbs, but this habit is already prevalent in the country. When the items mention certifications adopted in other countries, like GreenPro for pest control or Bird Friendly for coffee, these items are too specific for other contexts. Besides, some items evaluate the issue of buying organic coffee or "exotic" fruits such as avocado or chocolate and cocoa, and Brazil is a big producer of these foods. Therefore, to our knowledge, there is no particular instrument to access the sustainability in Brazilian foodservice in all of their dimensions [15].

In this sense, the lack of a standard certificate, data collection instrument, laws or governmental policies for foodservice in Brazil makes sustainable restaurants scarce in the country, with little implementation of specific environmental actions. Sustainable restaurant initiatives could be an opportunity to create a competitive advantage, combining sustainability with profitability in the foodservice sector [16,17]. Additionally, sustainable restaurants could be a way to promote cities for tourism purposes.

The activities in foodservice use a large number of natural resources in meal production, impacting on global sustainability and individuals’ health [15]. Therefore the development of a specific instrument is essential for the use in the certification processes and the evaluation of restaurants on sustainability, helping them to implement agroecological strategies. Thus, the objective of our study was to develop and carry out content validation, semantic evaluation, reproducibility, and internal consistency of a checklist designed to verify the sustainability indicators in foodservice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Checklist Development

The checklist was prepared through a literature review and researchers’ experience on the subject. In this sense, we used the International Organization for Standardization ISO 14000 that deals with the environmental quality system; ISO 14004, which guides the development, implementation, improvement, and maintenance of the Environmental Management System (EMS); and ISO 14001, which establishes guidelines for obtaining a quality certificate. The Brazilian Association of Technical Standards prepared all of these documents [18,19].

The Sustainable Restaurant Association (SRA) certifications, which characterize the sustainability policies adopted by foodservice, were also used, as well as the Green Seal Certifications (GSC). The GSC classify the foodservice (Bronze, Silver, or Gold), reconsidering them to change their category every three years until they reach the gold category [12]. Certification by the Green Restaurant Association (GRA) evaluates the restaurant, providing ways to implement environmentally sustainable activities [11].

We also used the American Dietetic Association (ADA) positions on practices for the Conservation of Natural Resources and support for Ecological Sustainability [20]. ADA’s positions aim to stimulate environmental practices to maintain natural resources, reduce the production of waste, and encourage ecological sustainability in food production. It is worth mentioning that all of these materials were extensively studied, and the items that were relevant to the Brazilian context were used for the first version of the checklist, as presented in the Supplementary file (Tables S3 and S4) and Table 1.

Table 1.

Checklist modifications in the content and semantics validation process by experts.

2.2. Content Validation

Content validation is a method to assess the tool quality in evaluating what it intends to measure [21]. We used the Delphi method to perform content validation. It is a technique that seeks a group consensus, determined by experts, on a subject or topic through individual responses [22]. A total of 16 experts with Ph.D./master’s degrees and known experience in instruments’ management in food and/or sustainability services were invited to participate. Thirteen experts agreed to participate in this step and received by email the proceedings to the evaluation of the checklist items. Most of the experts were female (n = 12; 92%), and the mean age was 45.07 ± 11.46 years old. Seven had a Ph.D., three had a post-doc and three had a master’s degree, and all of them are researchers from Brazilian public or private Universities.

The Survey Monkey® tool was used for content validation [23,24]. The questionnaire’s first page was used to guide the checklist evaluation criteria. The experts were guided to evaluate the items regarding the importance of sustainability in restaurants using a 5-point Likert scale from (1) “I totally disagree with the item” to (5) "I fully agree with the item" [23].

The Survey Monkey® platform was also used for experts to provide feedback on the items and the results of the analysis. The content validation process was performed in two rounds. In the first round, experts received the completed version of the checklist elaborated by the researchers of the study. The experts in the second round reassessed the items that were not approved in the first round. After being informed of the opinions of the other experts, they were invited to reassess their previous responses, maintaining or changing their previous answers. This was performed until a consensus was reached among the experts. The thirteen experts agreed to evaluate the instrument in both rounds.

2.3. Semantic Evaluation

The checklist´s semantic evaluation was performed in the Survey Monkey® at the same time as the steps described in Section 2.2. The experts were asked to evaluate each item concerning its clarity and considering their level of understanding of the subject. In this step, we also used the Likert scale from (0) “I did not understand anything” to (5) "I understood perfectly, and I had no doubts". Scores between 0 and 3 indicate a low level of understanding of the item, suggesting the need to reformulate the wording [25].

In cases of insufficient comprehension of the item or inappropriate language, experts were invited to suggest changes. These comments were used to create new versions of the items for further evaluation. Two rounds of semantic assessment were performed. Thirteen experts participated in this process. The researchers analyzed the questionnaire and merged the items that had similar wording or that could obtain the same result when evaluated, as suggested by the experts. Therefore, we sent the instrument’s final version to the experts for their final approval.

2.4. Reproducibility and Internal Consistency

After consensus by the experts’ panel, the reproducibility analysis (essential to determine the reliability of the instrument) [26,27] and the internal consistency (indicating if all parts of a tool evaluate the same features) [28,29] were performed.

The final version of the checklist was applied in 20 restaurants of the Federal District, Brazil, to verify the reproducibility and internal consistency of the instrument. Two different researchers applied the checklist to verify interobserver reproducibility, at the same time, in the same place, without communication between them. The instrument was filled out based on direct observation and questions asked to the dietitians and/or restaurant’s employees. It is worth mentioning that it was applied in different restaurant types (self-service, portioned service, cafeteria, à la carte), evaluating the checklist effectiveness and scope in different modalities. The restaurant’s owners were contacted to receive the invitation to participate in the research. The ones who agreed signed the agreement form.

The checklist reproducibility was tested item by item through the responses of the two independent evaluators, determining the reliability of the instrument by the answers. This phase served to verify possible difficulties with the checklist application. Additionally, we evaluated whether each item would measure actions in the way it was written.

The internal consistency of each item was also analyzed. For this step, the instrument was applied in 20 different restaurants in the Federal District, Brazil, at the same time as the reproducibility.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables (content validation and semantic evaluation) were used as descriptive statistics and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (reproducibility).

All responses were registered in Microsoft Software Excel 97–2003. With the answers of the 13 experts, we calculated the average score to assess the importance and clarity of the items. The rate of experts’ agreement for the items’ importance and clarity was assessed by the Kendall coefficient (W) of agreement (from 0 to 1). W values higher than 0.66 indicate a consensus among experts. Lower W values suggest disagreement among experts [21].

W values ≥0.8 were established for the approval of the item. Additionally, items should have an average of ≥4 for the importance and clarity assessment to be included in the instrument.

The items’ responses agreement was verified by absolute agreement and by Cohen’s kappa coefficient for the interobserver reproducibility test. Additionally, we verified reproducibility using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) (values ≥0.9 indicate good agreement). Regarding internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was used. Values from 0.7 ≤ α < 0.8 are acceptable, 0.8 ≤ α < 0.9 are good, and α ≥ 0.9 are excellent [29]. For all statistical analyses, we used the IBM SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

In this study, a checklist was developed and evaluated to provide a tool to support restaurants with the implementation of sustainability indicators. The final checklist was accurately reviewed, and all items were judged as essential and understandable by the experts (by Kendall’s coefficient ≥ 0.8).

Considering the suggestions made by the experts on content validation, and semantic evaluation, a checklist with 76 items was reached, which was subdivided into three sections (1. water, energy, and gas supply; 2. menu and food waste; 3. waste reduction, construction materials, chemicals, employees, and social sustainability). The first section is related to the practices that the company must adopt as a whole to reduce water, energy, and gas consumption. The second section consisted of items that directly assess food production and food waste. Finally, the third section of the instrument consisted of forms of waste and sustainability actions. Additionally, the organization of three sections with a closed number of items will facilitate the construction of a score and classification of foodservice as sustainable services or not.

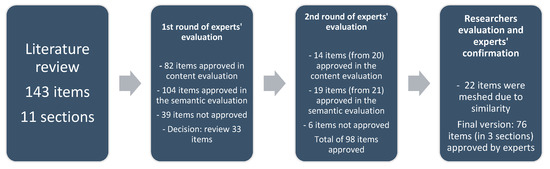

In total, two evaluation steps were necessary until the agreement between experts for the content validation and two rounds for the semantic evaluation. Besides, assessment by researchers and endorsement by experts was carried out, to conclude all contributions and remove items with repeated content. Figure 1 presents the steps of the checklist validation process.

Figure 1.

Summary of the steps of the checklist validation process.

3.1. Content Validation and Semantic Evaluation: First Round

In the 1st round of content validation, 82 items were approved (57.34%) (W values ≥0.8), and the items had a score of ≥4 in the importance assessment. Thus, 20 items (12 for content validation; 8 for content validation and semantic evaluation) without approval were rewritten with the experts’ observations and sent for a second round (Table S1, supplementary file). For semantic evaluation, 104 items (72.72%) were considered comprehensible (score ≥4 on the Likert scale), thus being approved (Table S1, supplementary file).

Despite having been approved in the first round of content validation, items 1.1 and 1.13 on water supply, 2.1, 2.17, and 2.24 on energy information, 4.21 and 4.23 on sustainable food/menu, 5.1 and 5.5 on food waste, 9.2 on employees, and 10.3 and 10.5 on social sustainability were not considered sufficiently clear by experts in the semantic evaluation. Additionally, some experts proposed to remove some items and mention a poor comprehension of the item’s purpose in the checklist regarding sustainability practices in foodservice. Additionally, they judged some items as subjective and/or repetitive. Therefore, the researchers used the information to reformulate the items and resend them to a new assessment of their importance and semantic evaluation. A total of 33 modified items were submitted to the second assessment round (Table 1).

3.2. Content Validation and Semantic Evaluation: Second Round

In the second round, items 1.14, 2.4, 2.18, 2.23, 4.22, 4.24, 7.2, and 8.3 were submitted for content validation and semantic evaluation (Table 1 and Table S3). Items 2.7, 2.12, 4.1, 4.14, 5.3, 5.4, 5.15, 6.10, 6.20, 7.1, 7.3, and 7.5 were evaluated for content validation and items 1.1, 1.13, 2.1, 2.17, 2.24, 4.21, 4.23, 5.1, 5.5, 5.16, 9.2, 10.3, and 10.5 were evaluated for semantic evaluation (Table 1 and Table S3). After the experts’ evaluation, items 4.1, 4.14, 4.24, 6.10, 6.20, and 8.3 (Table 1 and Table S3) were removed from the checklist, because they were considered not relevant by the specialists (average score < 4). The other modified items were approved (judged as relevant and understandable) and maintained in the checklist.

Researchers analyzed the checklist set, merging the items that presented a similar purpose. In this sense, 22 items were merged with similar items: 1.2 and 1.12 for water supply, 2.2, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, 2.10, 2.12, 2.13, and 2.15 for energy, 4.1, 4.11, and 4.18 on healthy food/menu, 5.1, 5.2, 5.11, and 5.13 on food waste, 6.3 on waste reduction, composting, recycling, and disposables, 8.4 on chemicals and pollution reduction, 9.1 on employees, 10.3 on social sustainability, and 11.1 on certification (Table 1, Table 2 and Table S3).

Table 2.

The final version of the checklist that evaluates sustainability in foodservice.

Additionally, researchers performed a new section organization, reducing the 11 sections (with a few numbers of items) to three sections (with a closer and higher number of items). Section 1 is composed of 28 items related to water, energy, and gas supply. Section 2 has 22 items on menu and food waste. Section 3 has 26 items on waste reduction, construction materials, chemicals, employees, and social sustainability. This checklist composition was sent to the experts (third round of evaluation), and all items and sections were approved, composing the final version of the checklist (Table 2).

Table 2 presents a checklist with the changes recommended by the experts for the best comprehension of the stages. All items had an answer type of "Yes / No / Not Applicable", except for the "Identification/information of the restaurant" section, composed by open questions characterizing the restaurant (name, number of meals, owner information).

3.3. Checklist Application in Restaurants—Reproducibility and Internal Consistency

Two different researchers applied the final version of the checklist in 20 restaurants (Federal District, Brazil) to verify interobserver reproducibility and internal consistency (Table S2, supplementary file). The average period of the application was two hours, with the necessary approach to the responsible nutritionist and some employees. The instrument is reproducible, all kappas were significant, the absolute concordances were greater than 90%, and all the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) scores were >0.9 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean score (and standard deviation—SD) and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

The internal consistency of each item by section of the instrument was verified. The internal consistency analysis of the checklist considered the 76 items to build the final version of the checklist. All items of the instrument were approved for internal consistency (Table 4), with alpha coefficient values greater than 0.672 (good internal consistency).

Table 4.

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s’ Alpha).

4. Discussion

The study is the first one to create a checklist to evaluate and develop standards for “green” or sustainable restaurants in Brazil. The results of other studies show that the indicators must assess three sustainable aspects—environmental, social, and economic [15]—which are considered the pillars of sustainability, covering 76 items that were selected and validated by the experts. In the systematic review conducted by Maynard et al. [15], the authors reinforced the importance of assessing the environmental, economic, and social aspects of foodservice to ensure that sustainability is verified in all its pillars. From the instruments used as the base for the Brazilian checklist, only the SRA and the Green Seal presented items from environmental, economic, and social aspects. However, they brought questions more related to legislations from the countries in which they were developed, and some items cannot be applied to Brazilian context.

For the development and validation of an instrument, it is essential to use strict methods [21,30]. In this sense, we used the Delphi technique, since it enables the achievement of a panel of experts performing content validation, facilitating consensus on the opinions of experts [23,31].

The Delphi technique guided the experts’ evaluations, allowing them to interact with the researcher by structured rounds [23,24,32]. The use of the Survey Monkey@ platform allowed the experts to provide quick feedback, which ensures a more organized interaction between researchers and experts. Another crucial point in a checklist validation is the appropriate experts’ selection. It is essential to obtain reliable results based on their experience and knowledge and also the willingness to collaborate with the study. However, the literature does not present a consensus regarding the number of required experts for the validation process [22,26,33,34]. However, in Brazil, Pasquali [35] considers at least six experts as needed to obtain a consensus, allowing variations according to the characteristics of the tool. In our study, thirteen experts participated in the process of checklist validation, which is considered adequate for this purpose.

The checklist has strengths, as it was evaluated by a panel of experts in the area, which were free to comment on what they considered necessary to improve the instrument. Additionally, the semantic validation and evaluation process allowed guaranteeing that the items are clear and understandable [35]. Thus, the checklist was also applied by two evaluators who verified its reproducibility, and it was tested using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). We also analyzed the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha formula, indicating good internal consistency [36]. Therefore, it is a reliable and trustworthy instrument.

In the study by Molina et al. [37], the intraclass correlation coefficient of an instrument for measuring food frequency was used to assess reproducibility and validity. Their results showed that the questionnaire had moderate levels of reproducibility and validity and it can be used to evaluate food-frequency. The study by Costa et al. [38] used the same methodologies to validate a checklist for fish-bearing, and stated that the checklist is valid and reliable to assess their objective of the bearing, thus showing the importance of using reproducibility and internal consistency in the construction and validation of instruments like checklists.

Obtaining a validated checklist to identify the sustainability indicators applied in Brazilian foodservice is an urgent need. In Brazil, sustainability in foodservice is something new and is still little used in recent years [14,15,39]. In a systematic review by Maynard et al. [15], which assessed sustainability indicators in foodservice, only two studies were conducted in Brazil. One study evaluated activities that involved the environmental aspect [40], and the other one evaluated activities that involved the three aspects of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic) [41], reinforcing the scarcity of sustainability studies and activities in the country for the restaurant sector. The lack of rules or defined standards in the resolutions on sustainability is perhaps the most flawed point in our country, as well as studies on the development of instruments on sustainability indicators.

For Raab, Baloglu, and Chen [42], restaurants have the social responsibility to get involved in sustainable practices. Consumers are more worried about sustainability, and they want their restaurants to implement sustainable indicators to become “green”. Jacobs, Singhal, and Subramanian [43] discovered in their study that restaurant managers were hesitant to use sustainable practices due to the lack of evidence that these practices would be recognized and valued by their clients.

Sustainable development is an innovation in restaurants that can be useful to attract consumers to return, as well as attracting tourists and travel agencies’ attention when choosing a place to visit. With the growing environmental awareness, innovation in restaurant services must assume its role as an ecological agent [44]. Some studies already show that customers are willing to spend more money on meals with less environmental impact [45,46,47], and other studies already showed the importance of diners’ awareness about sustainability. This awareness starts with the reduction of food waste, since reducing waste is investing in sustainability [4,48]. Restaurants face difficulties in initiating friendly environmental practices because of the low awareness of practical methods for the sector and fear of higher costs [49]. A practical checklist can help establishments go over each item and start to change non-sustainable procedures.

Sustainable certifications are mostly done by private companies or associations, which ends up being a cost for restaurants to invest in these certifications or even in ISO. This scenario reinforces the importance of building and validating this checklist, which will be a free and easy tool for professionals involved in the production of meals. Additionally, the checklist must address the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social). Sustainable practices need to cover the three points to be complete and to address the most significant number of activities that prioritize the best use of natural resources [15]. In this way, restaurants will be able to become aware of the need to implement safe agroecological practices and will act as future agents of environmental transformation.

In a Brazilian study by Martinelli and Cavalli (2019) [50], which surveyed the relationship between sustainability and healthy eating, the authors stated that sustainable diets are those that generate low environmental impact, contributing to the quality and food safety of individuals. They also reinforced that although many researchers focus only on the environmental aspect, sustainable diets must also involve social and economic aspects, since foods with less environmental impact may not be considered healthy or vice versa. It is worth mentioning that the menu and the sustainable menu are aspects evaluated in this checklist.

These data reinforce the importance of the constructed checklist (Table 2), since it includes the three sustainable dimensions in the form of items that contemplate various aspects for restaurants to be evaluated as agents that promote sustainable development. The instrument went through a rigorous validation process, including the experts’ evaluation, reproducibility, and internal consistency, demonstrating the concern to build a valid and comprehensive method that is used in this critical sector of the economy today. In the study of Wang et al. [6] that also built and validated an instrument for green restaurants, authors developed a checklist based on the need to create a standard for restaurants in Taiwan, and used the collaboration of government, industry, and academic experts. They concluded that the instrument had a significant contribution to establishing a management standard for green restaurants, which is not yet common in Taiwan.

Although there are other available instruments on sustainability, our study brings novelty because it includes the three pillars for evaluation (environment, economy, and social), and it is validated explicitly for foodservice in Brazil according to the country´s legislations. Besides, the use of the Delphi method allows a considerable volume of information, better reflection on the topic, and new suggested ideas by the experts in the field [22,23]. The checklist also becomes attractive due to the use of semantic evaluation, guarantying an adequate comprehension of the items, which is essential for the accurate assessment of sustainability indicators.

The checklist is practical, quick to apply, cheap, and easy to understand. It can be used by nutritionists, dietitians, managers, or owners of foodservice establishments, to classify whether the foodservice is sustainable or not, thus allowing the evaluated places to adapt to more sustainable practices. It can be applied in different foodservices, being an instrument that will be important in the Brazilian scenario, which has a growing sector related to the production of meals. Additionally, the study contributes to the formulation of an instrument capable of evaluating sustainability indicators. It can serve as a guide for the implementation of new sustainable practices in foodservices or even for a future classification of these places, also serving as a marketing strategy to consumers. In this way, restaurants will be able to become aware of the need to implement safe agroecological practices and will act as future agents of environmental transformation.

5. Conclusions

The checklist to verify sustainable indicators in foodservice was validated for content after careful analysis by experts. Items were considered essential and wide-ranging with a Kendall coefficient above 0.8. The instrument presents good internal consistency, and it is reproducible considering the proportion of agreement between professionals when applied in the same foodservice.

It is also important to highlight that the instrument is practical, quick to apply, not extensive, and encompasses the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social). This instrument can help professionals working in foodservices to use and apply sustainability indicators, helping them to create strategies to change behaviors towards the environment.

Further studies are necessary to test the checklist in a more significant number of foodservice so as to evaluate the contribution of implementing and verifying sustainable indicators. Strategies in this area are essential to improve knowledge in this field and encourage changes for more sustainable restaurants.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/10/4076/s1, Table S1. Checklist experts’ evaluation—average scores and Kendall’s coefficient of agreement for the checklist sections; Table S2. Frequency, percentage (%) of answers, percentage of absolute agreement, and value of Cohen’s kappa coefficient of agreement; Table S3. The first version of the checklist that evaluates sustainability in foodservice (English version); Table S4. The first version of the checklist that evaluates sustainability in foodservice (Brazilian-Portuguese version).

Author Contributions

D.d.C.M.: research; methodology; writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. R.P.Z.: data curation; formal analysis; supervision; validation and writing—proofreading and editing. E.Y.N.: statistical analysis. R.B.A.B.: data curation; formal analysis; supervision; validation and writing—proofreading and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Brasilia—DPI/DPG/UnB—Edital 02/2020.

Acknowledgments

To all restaurant owners and nutritionists evaluated in this survey, CAPES, and the University of Brasília DPI/DIRPE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lemaire, A.; Limbourg, S. How can food loss and waste management achieve sustainable development goals? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M. Recycling, recovering and preventing “food waste”: Competing solutions for food systems sustainability in the United States and France. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, E.M.L.; Martins, A.C.; Carvalho, S. Sustentabilidade e geração de resíduos em uma unidade d ealimentação e nutrição da cidade de Goiânia—GO. DEMETRA Aliment. Nutr. Saúde 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A. Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimates of U.S. Dietary Choices and Food Loss. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Chen, S.P.; Lee, Y.C.; Tsai, C.T.S. Developing green management standards for restaurants: An application of green supply chain management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/americas/noticias/ver/pt/c/239394/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- ONU. 2020. Available online: https://nacoesunidas.org/america-latina-e-caribe-respondem-por-20-da-comida-perdida-e-desperdicada-no-mundo/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Llach, J.; Perramon, J.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Joint impact of quality and environmental practices on firm performance in small service businesses: An empirical study of restaurants. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.; Nebioglu, O.; Demirag, M. A Comparative Study For Green Management Practices in Rome and Alanya Restaurants From Managerial Perspectives. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2015. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f238/d4a03b737a834a58ad16ff0749b020188217.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Green Restaurant Association |Sustainability|Certification. Available online: https://www.dinegreen.com/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Green Seal GS-55 GREEN SEAL STANDARD FOR RESTAURANTS AND FOOD SERVICES; 2014. Available online: https://www.greenseal.org/green-seal-standards/gs-55/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Rossi, C.E.; Bussolo, C.; Proença, R.P. ISO 14000 no processo produtivo de refeições: Implantação e avaliação de um sistema de gestão ambiental. Nutr. em Pauta 2010, 8, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg, V.J.; Jahno, V.D. Application of eco-efficiency in the assessment of raw materials consumed by university restaurants in Brazil: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Maynard, D.C.; Vidigal, M.D.; Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Nakano, E.Y.; Botelho, R.B.A. Environmental, Social and Economic Sustainability Indicators Applied to Food Services: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.J.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Y.Y. Green practices in the restaurant industry from an innovation adoption perspective: Evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. hung Confirmation of a measurement model for green supply chain management practices implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABNT. Sistemas de Gestão Ambiental-Requisitos com Orientações para uso Environmental Management Systems-Requirements with Guidance for Use; ABNT: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ABNT ABNT NBR ISO 14004:2005. Available online: https://www.abntcatalogo.com.br/norma.aspx?ID=1555 (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Harmon, A.H.; Gerald, B.L. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food and nutrition professionals can implement practices to conserve natural resources and support ecological sustainability. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lima, T.C.; Gallani, M.C.B.J.; de Freitas, M.I.P. Content validation of an instrument to characterize people over 50 years of age living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2012, 25, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendisch, C. Avaliação da Qualidade de Unidades de Alimentação e Nutrição (UAN) Hospitalares: Construção de um Instrumento; Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Ginani, V.C.; Gandolfi, L.; Pratesi, R.; de Medeiros Nóbrega, Y.K. Content validation and semantic evaluation of a check-list elaborated for the prevention of gluten cross-contamination in food services. Nutrients 2017, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratesi, C.; Häuser, W.; Uenishi, R.; Selleski, N.; Nakano, E.; Gandolfi, L.; Pratesi, R.; Zandonadi, R. Quality of Life of Celiac Patients in Brazil: Questionnaire Translation, Cultural Adaptation and Validation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.A.; Scagliusi, F.; Kawamura De Oliveira Queiroz, G.; Hearst, N.; Cordás, T.A. Cross-cultural adaptation: Translation and Portuguese language content validation of the Tripartite Influence Scale for body dissatisfaction. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.C.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; de Guirardello, E.B.; de Souza, A.C.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; de Guirardello, E.B. Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: Avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiol. e Serviços Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehara, R.; Goto, A.; Kotemori, A.; Mori, N.; Nakamura, A.; Sawada, N.; Ishihara, J.; Takachi, R.; Kawano, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; et al. Validity and Reproducibility of a Self-Administered Food Frequency Questionnaire for the Assessment of Sugar Intake in Middle-Aged Japanese Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780199231881. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolarinwa, O.A. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015, 22, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannarou, L.; Zervas, E. Using Delphi technique to build consensus in practice. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. 2014, 9, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Duprat Ceniccola, G.; Coelho Araújo, W.M.; Akutsu, R. Development of a tool for quality control audits in hospital enteral nutrition. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 29, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, L. Instrumentos Psicológicos: Manual Prático De Elaboração; IBAPP: Brasília, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, L. Psicometria. Rev. da Esc. Enferm. da USP 2009, 43, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auad, L.I.; Ginani, V.C.; Dos Santos Leandro, E.; Stedefeldt, E.; Habu, S.; Nakano, E.Y.; Nunes, A.C.S.; Zandonadi, R.P. Food trucks: Assessment of an evaluation instrument designed for the prevention of foodborne diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, C.L.; Winterstein, A.G. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2008, 65, 2276–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.D.C.B.; Benseñor, I.M.; Cardoso, L.O.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Drehmer, M.; Pereira, T.S.S.; Faria, C.P.; Melere, C.; Manato, L.; Gomes, A.L.C.; et al. Reprodutibilidade e validade relativa do Questionário de Frequência Alimentar do ELSA-Brasil Reproducibility and relative validity of the Food Frequency Questionnaire used in the ELSA-Brasil Reproducibilidad y validez relativa del Cuestionario de Frecuenc. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2013, 29, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.Z.F.; Medina-Papst, J.; de Oliveira Spinosa, R.M.; de Santo, D.L.; Marques, I. Content validity, reliability and construct validity of a checklist for dive roll evaluation. J. Phys. Educ. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatjiathanassiadou, M.; de Souza, S.R.G.; Nogueira, J.P.; de Oliveira, L.M.; Strasburg, V.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Seabra, L.M.J. Environmental Impacts of University Restaurant Menus: A Case Study in Brazil. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivaldini, M.; Pires, S.R.I. Sustainable logistical operations: The case of McDonald’s biodiesel in Brazil. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2016, 23, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, Ê.B.F.; Bezerra, I.W.L.; Seabra, L.M.J.; Silva, G.C.B.; Rolim, P.M. Metodologia de avaliação de cardápio sustentável para serviços de alimentação. HOLOS 2017, 4, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, C.; Baloglu, S.; Chen, Y.S. Restaurant Managers’ Adoption of Sustainable Practices: An Application of Institutional Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.W.; Singhal, V.R.; Subramanian, R. An empirical investigation of environmental performance and the market value of the firm. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chung, Y.-C. Expert Concepts of Sustainable Service Innovation in Restaurants in Taiwan. Sustainability 2016, 8, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Parsa, H.G.; Self, J. The dynamics of green restaurant patronage. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.L.M.; Horng, J.S.; Teng, C.C.; Chiou, W.B.; Yen, C.D. Fueling Green Dining Intention: The Self-Completion Theory Perspective. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S. Sustainability Development in Hospitality: The Effect of Perceived Value on Customers’ Green Restaurant Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.P.; Souza, L.H.R.; De Pinho, S.; De Pinho, L. Impact of a campaign for reducing food waste in a university restaurant. Eng. Sanit. E Ambient. 2019, 24, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, F.; Kandampully, J.; Solnet, D.; Kralj, A. Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Green Restaurants in the US. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, S.S.; Cavalli, S.B. Healthy and sustainable diet: A narrative review of the challenges and perspectives. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 4251–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).