Abstract

Culture plays an important role in implementing sustainability principles and approaching sustainable development goals across different countries. This paper aims to analyse the relationship between the value created by culture and the implementation of sustainable development goals of countries. The majority of attention in this research is devoted to composing and calculating the integrated cultural value index, which provides clear linkages between value created by culture and sustainable development goals. An expert survey was conducted, during which experts had to assess indicators by ranking them according to importance. There have been 14 indicators included in total to calculate the integrated cultural value index. The values created by culture in the selected Baltic States have been determined by calculating the weight coefficient of each indicator and providing a composite cultural value index. Statistical data analysis unquestionably confirms that cultural input when implementing sustainable development goals is significant, because there exists a very strong positive relationship between the cultural value index and achieved sustainable development goals in all three case studies.

1. Introduction

The issues of sustainable development have been analysed since the second half of XXth century, but the concept was formed and adopted by 178 world countries less than 30 years ago, i.e., in 1992, at the UN conference in Rio de Janeiro. This global concept describes sustainable development as such that would assure the satisfaction of the needs of the present generation without limiting the possibilities of satisfying the needs of the future generations. Sustainable development is composed of three elements: Economic environment, social environment, and quality of the environment. Even though the concept is not new, its implementation is revised. The UN adopted the resolution Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development for 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) (Annex 1) in 2015 that is based on five principles: People, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) are composed of not only development trends (17 SDGs), but of 169 target and indicator systems as well.

Culture and its various components started to play a more important role recently when assessing sustainable development. However, the cultural component is included only in a fragmented way in 17 SDGs: Its individual components are mentioned in four targets and two indicators of goals:

- Goal 4, target 7: By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development;

- Goal 8, target 9: By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products;

- Goal 11, target 4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage (indicator: National and municipal expenditure spent on the preservation of cultural heritage);

- Goal 12, target b: Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products;

- Goal 16, evaluation indicators: Primary government expenditures as a proportion of original approved budget, by sector (Lithuania’s national sustainable development indicators: The implementation of government budget expenditure plan for leisure, culture, and religion);

- Lithuania’s national sustainable development indicators: 17 goals evaluation indicators: The numbers of international agreements in the areas of education, culture, youth, science, technology, sport (encompassing all or parts of areas, including education).

The variety of cultural expressions, culture as a component of education, cultural heritage, and local culture are mentioned among the distinguished goals. However, even these generalised concepts of culture are mentioned in a wider context; for example, cultural heritage is mentioned together with nature (natural heritage), limiting this to cultural heritage protection, without mentioning updating or actualisation [1,2,3,4,5].

Such involvement of cultural components into SDGs has caused many discussions. In order to draw attention to the importance of culture for the understanding of sustainable development goals, an international campaign was implemented titled “The Future We Want Includes Culture” in 2013–2015, during which international arts organisations prepared a manifesto, a declaration on the inclusion of culture in the 2030 Agenda, a proposal of possible indicators for measuring the cultural aspects of the SDGs, and an assessment of the final 2030 Agenda. Correspondingly, Culture in the Sustainable Development Goals: A Guide for Local Action named in what way aspects of culture are related to all 17 SDGs and why it is necessary for a successful SDG implementation, providing examples of cases when culture contributed to reducing poverty, reducing inequality, etc.

The scientists [6,7,8,9,10,11,12] stress that culture provides an important input into functionalizing city and community, acknowledges that community vitality and life quality are determined by the involvement in cultural activities, and cultural value forms society’s lifestyle and thus can determine its changes that are necessary to assure sustainable development. Culture helps to create vivid cities and communities where people can live, work, and play an important role when contributing to social and economic welfare [13,14]. Thus, the integration of culture into the process of sustainable development not only determines the success of the process itself, but also contributes to the improvement of the quality of life in society. Most studies dealing with the role of culture in promoting sustainable development are oriented toward incorporating culture in sustainable development policies [15,16,17].

Dessein et al. [18] presented a study where culture was analysed in three aspects: (1) Culture as one of the components of sustainable development; (2) as a mediator between economic, social, and environmental areas; and (3) as the basis for sustainable development. UNESCO (2019) indicates that the role of culture is recognised in many SDGs, for example qualitative education, sustainable cities, environment, economic growth, sustainable consumption and production, peaceful and inclusive society, gender equality, etc.

There is a need to explore the possible cultural impact on sustainable development without being limited to those SDGs where culture is mentioned in one way or another, as other studies in this field do not address this issue. Thus, the paper aims to close the gap and aims to define the relationship between the value created by culture and the implementation of sustainable development goals. The most attention in this research is devoted to composing and calculating the integrated cultural value index.

The reminder of the paper is structured in the following way: Section 2 provides literature review and conceptualises the cultural dimension in the sustainable development understanding; Section 3 presents methodology for assessment of linkages between value created by culture and progress in sustainable development of the country; Section 4 presents empirical study for assessment of the cultural input when implementing sustainable development goals in selected three Baltic States; Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Culture as Sustainable Development Pillars, Conceptualisation

Nowadays, sustainable development is discussed more as the evaluation of macro processes, focusing on solving issues of global economic development, regional, and sustainable community problems and insufficiently evaluating sustainable development at the micro level of social processes. Insufficient attention is devoted to the cultural aspect of sustainable development, or in other words, lack of attention is provided to the evaluation of cultural impact on sustainable development [19,20,21,22,23]. Thus, the cognitive paradigm of sustainable development is very important nowadays, the essence of which is described by society’s education and teaching, ethnic, and cultural relations between a human being and the world that creates an excellent tool for achieving the overall progress. The overall progress should be consistent with the human race’s surrounding environment in a new context that values the cultural paradigm [24]. This context has traditional frameworks for sustainable development, defined by the three main dimensions of sustainable development.

Sustainable development encompasses three main dimensions: Economic, environmental, and social. The economic dimension of sustainable development describes such development that creates conditions for long-term stable economic growth. Environmental refers to using natural resources but at the same time leaving a sufficient amount for future generations. The social dimension of sustainability requires satisfying the main needs of a person, creating an overall qualitative life, including the ability to meet the cultural needs of the individual [25,26].

Recently, culture and its various components have been playing a bigger role when evaluating sustainable development at the national and international level [27,28,29,30]. However, the place of culture in the process of sustainable development and value created by culture has not been sufficiently acknowledged [27]. In the UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies, Mexico City, 1982, it was stressed that a cultural approach to development is necessary, and it should be based on the acknowledgement of local identity and participation at the local level.

Sustainable development has to be acknowledged as a multidimensional process of development, encompassing complex, comprehensive, and multidimensional development as difficult, based on acknowledgement of local identity and participation on a local level, where members of the community have to share economic, social, and environmental efforts. Moreover, as the world is encountering economic, social, and environmental challenges, creativity, knowledge, variety, and beauty are an unavoidable basis in a dialogue for peace and progress, because these values are, in essence, related to human development and freedom. The aspect of cultural sustainability creates strong relations with the other three aspects of sustainable development and is compatible with each of them [31,32,33].

Environmental, social, and economic sustainability models that are used at present assess culture as an important aspect; however, there still is a lack of understanding on how culture is specifically related to sustainable development. Culture could be integrated into the concept of sustainable development in three roles [28]:

- Supportive and self-promoting role (characterised as culture in sustainable development), which simply and unquestionably expands conventional sustainable development discourse by adding culture as a more or less self-standing fourth dimension. Culture is related, but independent from its separate environmental, social, and economic aspects. Figure 1. Presents the concept of supportive and self-promoting role of culture.

Figure 1. Culture as an independent pillar of sustainable development [18].

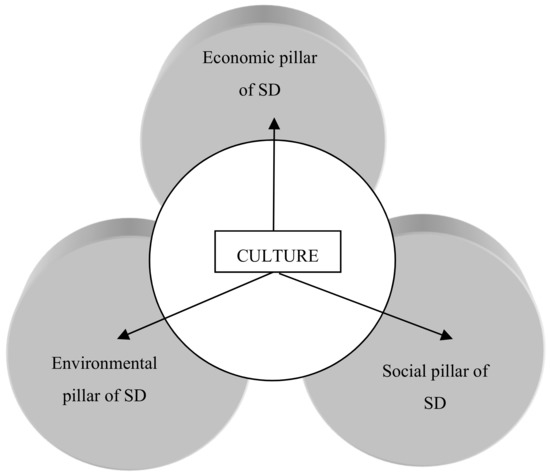

Figure 1. Culture as an independent pillar of sustainable development [18]. - The second role is described as culture for sustainable development, which offers to assess culture as a more influential force that can operate beyond the boundaries of sustainable development. This role moves culture into framing, contextualising, and mediating mode; one that can balance all three of the existing pillars and guide the process of sustainable development between economic, social, and ecological pressures by forming a variety of needs that arise from cultural goals and actions. Figure 2 provides the concept of culture for sustainable development.

Figure 2. Culture for sustainable development [18].

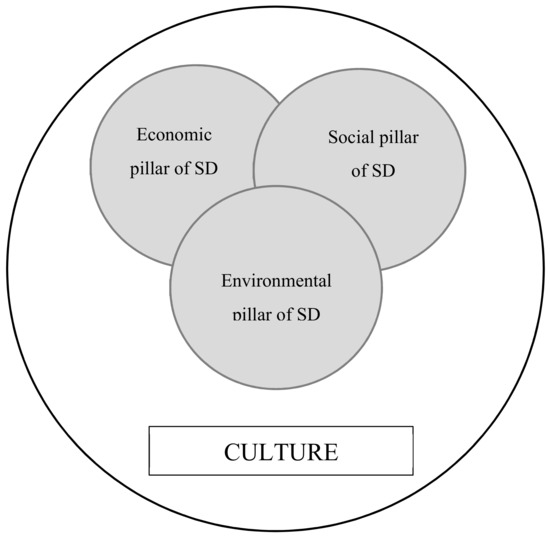

Figure 2. Culture for sustainable development [18]. - This role describes culture as sustainable development, where culture is seen as the essential foundation and structure for achieving the aims of sustainable development. When recognising culture as the root of all human decisions and actions and even a new paradigm in sustainable development thinking, culture and sustainability become mutually intertwined, whereas economic, social, and environmental dimensions differ, because they do not have such a close connection. Figure 3 presents the concept of culture as sustainable development.

Figure 3. Culture and sustainable development.

Figure 3. Culture and sustainable development.

The conceptualisation of culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development together with environmental, social, and economic pillars is based on the already established, simple, and practical approach. Such an approach has its threats, because culture could be viewed in a limited way as art or as a cultural-creative sector [29]. In such a way, the definition of culture is narrowed. It should be noted that this concept allows understanding culture qualitatively as well as quantitatively. However, the role of the fourth dimension provides more opportunities. This allows connecting culture to the concept of sustainable development. The introduction of culture as the fourth dimension of sustainable development allows defining the sustainable development characteristics of the art and culture sector. Cultural values could be employed in forming policy, implementing strategies of sustainable development, applying in art and culture organisations, and business companies in practice. Artistic and creative values could be used, for example, when establishing criteria related to the sustainability assessment of a particular policy, organisation, or company, establishing criteria based on which it is possible to assess cultural input in sustainable development through the creation of a product or image.

The second conceptualisation model (Figure 2) is wider and encompasses more. In this case, there is an opportunity to encompass a variety of human values, certain subjective meanings that include people’s attitudes and lifestyles, to assess cultural differences. Culture could be in the role of “balancer” that aims to balance contradictory needs of people, communities, and representatives of different cultures. Culture could be a mediator connecting various, usually different, aspects of sustainable development. The fact that this concept was properly used only partially explains the reluctant process of sustainable development.

The concept of culture as sustainable development that was presented in Figure 3 allows for creating a common approach to environmental, economic, and social sustainability as one including cultural life in certain situations and places. Evolutionary culture or eco-cultural civilisation encompasses understanding and acknowledgement of the human place in the world, recognising that humans are an inseparable part of the more-than-human world [29]. The most important of all is the understanding that all human action is interrelated and when these actions appear depends on the situation and circumstances. Such perception of culture allows creating new values or a new way of life, even realising utopian visions of sustainable society. Culture becomes the matrix for a particular way of life [30] and more than an analytical tool: Culture in this approach refers to a worldview, a cultural system guided by intentions, motivations, ethical, and moral choices, rooted in values that drive individual and collective actions [29,30].

Depending on the circumstances and aims, all three roles of culture are important; everything depends on the context. The presented roles are not an evolutionary path that should be followed, but in this system of three roles, certain tendencies, dynamics, and trajectories could be noticed. Policies become more diverse and multi-layered; thus, a broader understanding of sustainable development is needed and more dialogue and interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary communication is required. Having evaluated the results of previous studies [27,28,29,30], it is obvious that after the conceptualization of culture as an equal pillar of sustainable development, the definition of culture becomes broader, which requires a systematic approach, including aspects from both natural and human worlds.

2.2. Sustainable Development Goals and Culture

The contemporary society experiences transformation into a new sustainable, saving society in order to provide opportunities for humankind of a safer, healthier, and richer world with continuous teaching and learning, new knowledge, values, rules, and the need to know, understand, act meaningfully, and responsibly [31]. The resolution “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, adopted by the UN General Assembly and signed by the President of the Republic of Lithuania and 192 Heads of States, officially came into force at the beginning of 2016 by offering sustainable development goals for the governmental authorities. This is the result of thorough and comprehensive three-year negotiations that included international, national, and regional players from intergovernmental, governmental, regional institutions, private and public sectors, and civil society. These goals are important on the global and national level and combine global as well as national actions aiming for a more sustainable world. The 2030 Agenda is much more ambitious than the Millennium Development Goals and encompasses more issues; it should be implemented by developing and developed countries. The Agenda identified 17 sustainable development goals that are based on the success of Millennium Development Goals, including the following priorities: Climate action, economic inequality, innovations, responsible consumption, peace and justice, and others. In order to implement these goals, there was composed a system of 99 indicators that, in essence, can differ from the UN composed system of indicators of sustainable development [32].

None of the sustainable development goals are directly oriented to culture, i.e., the concept of culture is not directly included in the definitions. Regardless, some aspects should be taken into consideration, because relations between sustainable development goals and culture are obvious (Table 1). Cultural services, according UIS, 2009 UNESCO, Framework for Cultural Statistics, aimed at satisfying cultural interests or needs. They do not represent cultural material goods in themselves but facilitate their production and distribution.

Table 1.

Sustainable development goals and role of culture.

As it can be seen from Table 1, the fourth sustainable development goal aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education that can be realised by acquiring new knowledge that would encourage sustainable development. This would require applying the existing and potential education measures, encouraging public citizenship and cultural diversity accessibility, and evaluating cultural input to sustainable development.

Another sustainable development goal that should promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth is oriented towards the formation of overall state development policy that aims to create a sustainable economy, which is only possible when supporting productive activities, using innovations, employing personal and group creativity, and activities related to it.

The ninth and tenth goals are related to the implementation of sustainable tourism concept. Sustainable tourism encourages the creation of resilient infrastructure, promotion of inclusive and sustainable industrialization, fostering possibilities for creation, and implementation of innovations, not only in the main cities, and planning the assessment of local cultural elements while creating necessary monitoring measures.

The 11th sustainable development goal, in which the main aim is to make cities inclusive, safe, and sustainable, is especially important from the cultural perspective. The achievement of this aim could be implemented by creating and implementing programmes and strategies that directly obliges countries to protect cultural and natural heritage.

Thus, successful implementation of sustainable development objectives requires not only economic, social, and environmental aspects (components), but also to determine and assess the value created by culture in the overall economic growth process of a country.

3. Research Methodology

Culture is a very difficult phenomenon of society and its life requiring complex cognition as well as the object of cognition, characterised by a wide variety of features [33]. It contributes to human welfare, social cohesion, and inclusion. Cultural and creative sectors are the engine of economic growth, job creation, and external trading. Thus, in analysing the impact of value created by culture on approaching the sustainable development goals, it is necessary to assess the value created by culture for country’s economy.

When aiming to evaluate the value create by culture in a complex way, economic and non-economic evaluation methods could be applied. Reference [34] states that in order to gather and evaluate information on cultural input to economic growth, the methods of structural analysis that are related to such indicators as gross domestic product, value added, employment, expenditure of households, etc., could be employed [34]. According to the author, most states (including Lithuania) use the production or value chain approach for the assessment; structural analysis could be supplemented by assessing cultural sector’s branches by various aspects, i.e., conducting statistical analysis of enterprises or expert review of individual branches, etc. Cultural and creative industries are assessed by employing integrated indicators (European Creativity Index, Creative Economy Index, Global Creativity Index, Hong Kong Creativity Index, etc.).

Recently, a lot of attention has been devoted to non-economic assessment methods, especially for the application of value-based approaches (the value-based approach (VBA) study [35] stress that this method distinguishes and assesses short-term and long-term qualitative impact, which can be created by culture. The interaction between economic, social, and cultural processes is regarded, at the same time assessing various values related to these processes and respecting goals that were determined in advance. Contrary to traditional production assessment methods, this method clearly employs shareholder approaches to the qualitative impact of different values.

First, when determining implementation interrelations between the value created by culture and sustainable development goals, the analysed territorial units have been defined in this research. The main territorial units that are compared with each other, according to the selected indicators, are the three Baltic States: Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. The three Baltic States have been chosen because similar economic growth, demographic, and employment perspectives were observed; moreover, even though each has national identity, the cultural policy goals of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia are similar. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have experience working together in the area of cultural policy, especially when creating creative industries. The first attempt of policy makers from three countries was made in 2006. From that point, experts and cultural policy makers have shared good experiences in the areas of cultural industries and common culture creation and form united positions in the European Union. The three Baltic States as well refer to culture and creativity involvement in strategy “Europe 2020” and its initiatives.

Table 2 presents Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia’s goals when formulating cultural policy.

Table 2.

Cultural policy goals in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

As it can be seen in Table 2, the goals of cultural policy in all three Baltic States are similar but reflect each country’s identity that depends on historical and socio-economic context of each country. It is not difficult to notice that in all three Baltic States, the importance of active respondents’ involvement and participation in cultural life is stressed. It is noted in Lithuanian strategy papers that it is important to develop information society, ensure society’s participation in cultural life, and cultural consumption. One of the goals in Latvia is to improve the availability of cultural territories and cultural services, and the involvement of community members in cultural processes is stressed as well. Estonian strategy papers identify most cultural policy goals that aim to create conditions for the creators and viewers in all countries to use cultural measures, improve possibilities of people with special needs to participate in cultural life, as well as to involve professional associations in the decision-making processes in the cultural area, support the creative and cultural industry as a part of knowledge economy, etc.

The documents regulating cultural sector’s activities in the Baltic States are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Documents regulating cultural sector’s activities in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia

As it can be seen in Table 3, most of the documents regulating cultural sector’s activities are in Lithuania. The goals of cultural policy that have been determined by countries are included in the strategy plans of the Ministry of Culture and correspond to cultural goals provided by the Council of Europe: Promotion of identity, diversity, supporting creativity, and participation in cultural country.

Table 2 and Table 3 present country-specific cultural policy objectives and documents governing the cultural sector. It is noted that the objectives of cultural policy are defined in detail in Estonia, but the number of institutions regulating cultural activities is the lowest in this country. The study found that it is in Estonia that most people work in the field of culture and that the cultural enterprises of this country generate the highest gross added value. This suggests that the efficiency of the cultural sector is not directly dependent on the number of institutions regulating the sector but depends on the detailed objectives of sustainable development.

The assessment of the impact of value created by culture involves four stages. First, the general tendencies of the selected indicators, which show the value created by culture for country’s economy, were described. The general tendencies of the selected indicators help explain why culture is important for achieving the 1st, 8th, and 12th sustainable development goals. For example, the eighth sustainable development goal is “Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all”, so the data on cultural employment are important. Cultural (and creative) sectors can become the areas of inclusive, sustainable, and decent employment.

In the second stage, indicators are selected to set the composite culture value index. In order to calculate cultural value index, there has been 14 indicators integrated in total (there were selected indicators indicating the value created by culture for country’s economy) to the initial list of indicators, covering the analysed period of 2015–2017. The states were assessed and grouped according to the selected indicators that were analysed; the survey of experts was conducted according to the composed expert assessment questionnaire. The experts were asked about their professional qualifications and professional experience. Experts assessed the presented indicators to calculate an integrated cultural value index. The obtained expert answers were analysed based on the average of response significance. Each indicator weight coefficient () is calculated with the following equation:

where is a statistical average and is a sum of statistical averages.

Lithuanian experts were surveyed. The main criteria for the choice of experts are qualification and professional experience. Expert survey was conducted by sending a questionnaire via email. The survey invitations were sent to 14 persons, but only 10 agreed to complete the questionnaire. The experts were selected regarding their qualifications (scientific research and professional activities related to sustainable development, cultural policy, sustainable development and cultural researches, assessment of sustainability, etc.) and experience (average work experience of respondents is more than 24 years).

In the third stage, having chosen the assessment indicators, a composite index was completed, which assessed value created by culture in Lithuania, and the following situation is compared with other Baltic states. The equation of composite cultural value index is the following:

where is indicator’s weight (importance) and z is min–max index that is calculated with the equation:

where is actual value of the indicator; and are minimum and maximum values of the indicator.

First, the min–max index, which assesses country’s situation comparing to the other countries that reflect the worst and the best situations, is calculated. The actual value of the indicator is the meaning of a particular indicator of a particular country (selected indicators of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia). The meaning of a country with the minimum indicator is closer to 0, and the maximum is closer to 1. The maximum (the best) means high value created by the culture, and minimum (the worst) represents low value created by the culture.

Finally, in the fourth stage, the statistical dependence of the cultural value index (IKKV) from sustainable development goals index (SDG index) was analysed. In order to verify the strength of the interdependence, the correlation–regression analysis was used. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel and Statistica software.

4. Discussion of Results

4.1. The Value Created by Culture for Country’s Economy

Culture contributes to the creation of gross value added. The gross value added, created in the cultural sector of EU Member States, grew on average by 2.4% per year in 2011–2015; it amounted to 199,012.3 million EUR or 2.83% of country’s gross value added in 2015 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cultural enterprises, value added, and turnover in European Union (28 countries), in 2015.

Only in Cyprus (3.52%) and the United Kingdom (4.21%), the gross value added, created in the cultural sector, exceeded the EU average (2.8%) in 2015. The United Kingdom that has exclusive share of 4.2% creates 30% of gross value added created by EU cultural enterprises. However, the value added created by cultural enterprises was much smaller than the EU average in Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, and Slovakia (less than 2%) [36]. In EU28, almost one-third (31%) of value added is created by publishing, 21% by programming and broadcasting, and 20% by film, video, and television programme creation, sound recording, and music publishing activities.

According to Eurostat (2019) data, the turnover of cultural sector (the total value of market sales of goods and services) amounted to 475 million Euros, composing 1.7% of the total turnover of the non-financial business economy. The highest turnover was recorded in Cyprus (3.2%), which could be related to the growth of computer games publishing. In Croatia, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (among countries with available data), the turnover of the cultural sector also exceeded EU28 average (1.74%). In the United Kingdom, which had 8.2% of all EU cultural enterprises in 2015, the turnover amounted to 25% of EU cultural enterprises turnover. The lowest turnover of cultural sector was recorded in Slovakia (0.8%) (Table 4).

The only Member States that have more than 150,000 cultural enterprises are France and Italy, \ each having 15% of all EU cultural enterprises. Together with Germany (130,000 enterprises) and the United Kingdom (100,000), these four countries had almost half of all EU cultural enterprises. Cultural enterprises represented a significant share in Sweden (7.6%), the Netherlands (7.3%), Belgium, and Slovenia (6.5% each) [36].

The number of cultural enterprises in seven EU States (from 24 countries with available data) in 2010–2015 were stable (the number of enterprises changed on average by 1% per year) [36]. In the other 14 Member States, the number of cultural enterprises rose by more than 1% a year, with an increase over 10% in the Netherlands, Latvia, and Lithuania (10.9% and 14.1%, respectively).

There were working 8.7 million people, i.e., 3.8% of total employment, in EU28 cultural sector in 2017. The number or employment in the cultural sector in 2012–2017 was not high but stable. There were 544,000 jobs (+ 6.7%) more in the cultural sector in 2017 than in 2012, and the annual growth rate was 1.3% [36]. However, relative growth was not noticed. The employment in cultural sector was 3.8% in 2017, the same as in 2012. This means that employment in cultural sector grew at the same speed as the total employment.

In order to compare the indicators of employment in the cultural sector in different EU28 States, min–max indexes (Table 5) were calculated, which showed that the highest level of employment in the cultural sector during the analysed year was recorded in Estonia (even though the Estonian level of employment in the cultural sector reduced on average by 0.4% a year).

Table 5.

Cultural employment (% of total employment) in European Union (28 countries).

The lowest level of employment in the cultural sector in 2013–2017 was recorded in Romania (even though the level of employment in the cultural sector in 2013–2017 increased on average by 3.4% a year) (Table 5). The level of employment in the cultural sector in 14 EU28 Member States was higher than the EU average in 2013 and 2017. When evaluating the changes in the level of employment in the cultural sector, it has been noticed that the evolution of the share of cultural employment in the total employment varied among the EU Member States between 2013 and 2017. Even though there has been observed a slight increase or stagnation in the number of employment in the cultural sector in most of the countries, there has been noticed a slight decline in other states (Luxembourg, Denmark, Ireland, Germany, Austria, Estonia, the Netherlands, Greece, Hungary, Finland, Slovenia, and Lithuania).

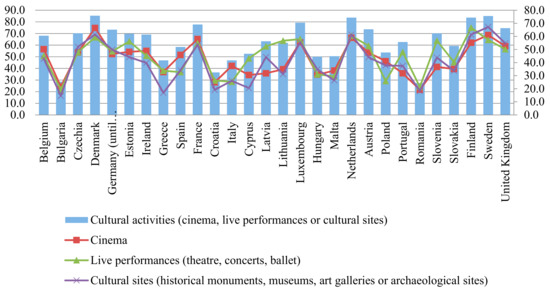

Not only economic indicators described in the Table 4 and Table 5 were able to assess the value created by culture. Possibilities to participate in cultural activities have a significant impact on human life quality, contribute to welfare, and help them to integrate into society. Each member of society, depending on priorities, chooses in which cultural activities to participate. Some prefer to read book or newspapers; others prefer to go to the cinema, theatre, other cultural objects, or events. Statistical data show that 64% of 16 and older persons from all EU28 had been to the cinema, a live performance, or a cultural site in last 12 months. However, most of the residents went to the cinema (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cultural participation. Source: Compiled by the authors based on Eurostat. (2019) Statistics explained. Culture statistics [36].

Most (45.9%) EU28 citizens had been to the cinema, a slightly smaller share 42.8% attended live performances, and the same share visited cultural sites (Figure 4). However, in different EU28 States, the preferences of residents differ. Going to the cinema is mostly preferred in Denmark (66.5%), Sweden (61.1%), and the Netherlands (59.0%). A rather smaller share of residents went to cinema in Romania (19.3%), Bulgaria (21.7%), and Croatia (24.9%). Attending live performances was the most popular activity in 13 of EU28 Member States (Finland (66.7%), the Netherlands (60.5%), Denmark (59.3%), Luxembourg (57.9%), Sweden (57.3%), Slovenia (56.8%), Lithuania (56.7%), and other states). Visiting cultural sites was the least common activity. This cultural activity was very popular in Sweden (67.2%), and not so popular in Bulgaria (14.6%), Greece (16.9%), and Romania (18.3%). Thus, the differences in attending cultural activities are apparent, and these differences are determined by the development level of the state, population income, age, education, availability, and accessibility of cultural objects.

4.2. The Assessment of the Value Created by Culture in the Baltic States

Summing up the opinion of experts, it highlighted that when ranking indicators to calculate the integrated cultural value index, the experts attributed the maximum weight to the gross value added (% of the country’s gross value added) and the average expenditure of households on cultural goods and services (EUR), the weight coefficient of both indicators is 0.0868, and the minimum value (0.0566) was given to two indicators related to export, i.e., cultural goods export (thousand EUR) and share of cultural goods export (% of the country’s total export) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Expert opinion on the significance of indicators to calculate the integrated cultural value index

As it can be seen in Table 6, the import of cultural goods and the number of cinema viewers (per capita), weight coefficient of which is 0.0604, seemed to be not so significant for the experts. However, “the number of residents that participated in any cultural activities in the last 12 months (%)” seemed significant for the experts (0.0830). Other indicators that were named as significant by the experts are the number of persons employed in the cultural field in comparison to the total number of persons employed (%), expenditure for leisure, culture, and religion (% of the GDP), and the number of economic operators in the cultural area (% of all economic operators). Their weight coefficients are 0.0830, 0.0792, and 0.0755, respectively.

When assessing the value created by culture in the Baltic States, first, the min–max meanings were calculated (Table 7).

Table 7.

Standardized values of indicators chosen for the research.

When analysing the min–max meanings (Table 7) in the selected countries, it is clearly seen that the highest number of persons employed in the cultural field was in Estonia, in comparison to the total number of persons employed, %. Comparing 2017 to 2015, the number of persons employed in the cultural field increased by 0.2 percentage points; moreover, the number of such persons in Estonia was the highest in comparison to the other EU Member States; the percentage of people employed in culture in 2017 varied from 1.6% in Romania to 5.5% in Estonia. In EU Member States, “in 2017 around 8.7 million people in the EU were working in a cultural sector or occupation, that is, 3.8% of the total number of people in employment”(With regard to economic sectors, cultural employment relates to activities such as: ‘creative, arts and entertainment activities’, ‘libraries, archives, museums and other cultural activities’, ‘publishing of books, periodicals and other publishing activities’, ‘printing’, ‘programming and broadcasting activities’, ‘motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities’, or ‘specialised design activities’ [34].).

Estonian cultural enterprises in comparison to other selected Baltic States composed the biggest gross value added (% of the country’s gross value added), that was 0.2 percentage points higher than in Latvia and 0.3 percentage points higher than in Lithuania. Estonia had the highest economic operators’ turnover of the cultural field and the number of persons participating in cultural activities (number of theatre viewers, number of museum visitors, number of library readers, number of cinema viewers). Another indicator confirms the fact that Estonian residents tend to participate in various cultural activities: According to 2015 data, 72.1% of residents participated in cultural activities at least once over the last 12 months, whereas the share of such residents in Latvia amounted to 66.9% during the analysed year, and only 63.8% of Lithuanian residents participated in cultural activities at least once over the last 12 months.

However, it is interesting that in Estonia, the mean consumption expenditure of private households on cultural goods and services (PPS) during the investigated period was by 0.69% lower than in Latvia and 11.8% lower than in Lithuania. This allows one to assume that the residents of all three Baltic States tend to participate in cultural activities; however, as the average wage after taxes remain to be lower in Lithuania than in Estonia and Latvia, this forces Lithuanians devote a larger part of it in order to satisfy leisure needs.

The data provided in Table 8 reveals that the best position, according to the indicators selected for this research, is occupied by Estonia (first place). The second and the third places go to Latvia (index of 0.3792) and Lithuania (0.1979).

Table 8.

The distribution of Baltic States according to the value created by culture

As it can be seen in Table 8, Estonia and Latvia occupy the worst position according to two indicators. Estonia has the lowest import of cultural goods by product, thousand Euro (i6), and mean consumption expenditure of private households on cultural goods and services, PPS (i9); Latvia has lower values than other Baltic States in cultural enterprises, % of the total economy (i2), and library users per 1000 population (i13) (3rd position); whereas the situation in Lithuania is much worse, as this country occupies third position according to the most indicators selected for the research. Lithuania has a much lower number of persons employed in the cultural field (in comparison to Estonia, Lithuania had by 1.7 percentage points less of such persons in 2017 than Estonia). The main reason for this is small wages of persons employed in the sector (in 2017, the average wage in this sector was by 200 Euros smaller than the average national wage). Even though the number of economic operators in the Lithuanian cultural sector is the highest, the enterprises working in this area create the lowest added value among the Baltic States due to not very favourable business conditions. This allows to state that Lithuanian cultural value is still poorly acknowledged and usually ignored.

However, the statistical data analysis reveals that cultural input when implementing sustainable development goals is unquestionable. Therefore, each country’s achievements in the implementation of SDGs are also important. The achievements of each country are shown by the SDG index. The global SDG Index score and scores by goal can be interpreted as the percentage of achievement. The difference between 100 and countries’ scores is therefore the distance in percentage that needs to be completed to achieving the SDGs and goals [37].

Estonia is in first place, according to the implementation of sustainable development goals. In 2017, its SDG index value was 78.6. Concerning cultural value index, Latvia occupies the second position (index value 75.2) and Lithuania the third place (SDG index 73.6). When aiming to achieve sustainable development goals, the Baltic Statesm as well as the other EU28 States, implemented changes in education, healthcare, energy, and other areas. Figure 5 presents the achievement of the Baltic States when trying to implement individual goals of SDG.

Figure 5.

Average performance by sustainable development goals (SDG) in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Source: SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2018. Global Responsibilities implementing the goals. 2018 (Access through internet: https://sdgindex.org/reports/sdg-index-and-dashboards-2018/).

As it could be seen in Figure 5, all three Baltic States implemented sustainable development goals 1, 4, 6, 8, and 13 relatively well. This reveals that the strategies created in countries and implementing measures help to reduce the number of persons joining the poverty ranks, assuring quality education and encouraging lifelong learning, ensuring access to water and sanitation, etc. Estonia and Latvia encounter larger difficulties when implementing SDGs 2, 9, and 17. Lithuania did relatively well in implementing sustainable development goals 1, 4, 7, 8, 11, 13, and 15, but encounter difficulties when implementing SDGs 2, 3, 5, 9, 10, 12, 14, and 17. Even though this country is fighting extreme poverty, implementing reforms in healthcare and education areas, the results achieved in other areas are not satisfying. The measure of relative strength (correlation coefficient) helps to determine which cultural input reflecting indicators have the biggest impact on the implementation of sustainable development goals. When evaluating the relative strength between SDG index and indicators reflecting cultural value, the correlation coefficients have been calculated (Table 9).

Table 9.

Results of the study of the dependence of the SDG index and indicators reflecting the value created by culture

The correlation coefficients provided in Table 9 reveal that there exists a strong and very strong relation between SDG index and almost all indicators allowing to assess value created by culture. However, the relation is statistically significant (p < 0.05) only between SDG index and three indicators: Cultural employment, participation in any cultural or sport activities in the last 12 months, and museums visitors. Thus, the implementation of sustainable development goals is influenced more by the involvement of each country’s residents in cultural activities, i.e., persons employed in the cultural area and persons participating in various cultural activities. A significant role is played by the formed cultural policy, decisions made by the government, and their implementation.

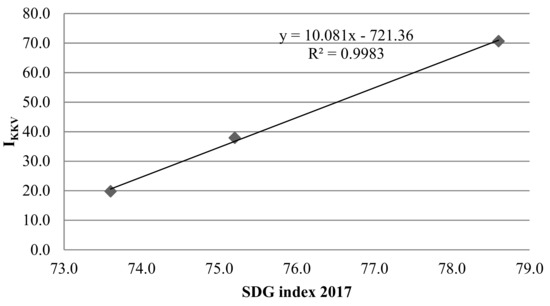

When analysing the statistical dependence of the cultural value index (IKKV) from the sustainable development goals index (SDG index), there has been determined a strong interrelation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The interdependence of the cultural value index and the sustainable development goals index. Source: Created by the authors

A conclusion could be made from the presented data in Figure 5 that there exists a very strong positive relation (correlation coefficient r = 0.9992) between IKKV and SDG indexes. The determination coefficient (R = 0.9983) reveals that 99.83% of achievement when implementing sustainable development goals could be explained by a large input of value created by culture. The relation is statistically significant, because p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

The sustainability assessment models, recently employed in scientific literature, that encompasses three sustainable development dimensions (economic, social, and environmental) asses cultural impact and created value only by a small part and do not provide a holistic approach to the place of culture, as an element of sustainable development, within the context of overall sustainable development. A thorough analysis of scientific literature allows concluding that culture could be integrated into sustainable development assessment methods in three ways: Culture as an independent pillar of sustainable development, culture as a powerful driving force of sustainable development, and culture as the basis for sustainable development.

The conceptualization of culture as the fourth component of sustainable development requires a systematic approach using three possible models, which allows for the integration of culture by broadening its definition. This requires a broader understanding of sustainable development and ongoing interdisciplinary cooperation.

The sustainable development goals determined by The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development do not directly reflect the impact of culture on the assurance of successful sustainable development process, but it should be noticed that indicators that were used for the implementation of individual goals are directly related to the impact of value created by culture in the process of creating added value. The analysis conducted on EU28 cultural indicators allows one to state that the value created by culture could be determined not only with economic indicators.

In order to calculate integrated cultural value index, the survey of experts was conducted according to the composed expert assessment questionnaire. The experts attributed the maximum weight to the gross value added and average expenditure of households on cultural goods and services.

During the conducted research, it has been determined that Estonia had the biggest number of persons employed in the cultural area during the investigated period. Estonian cultural enterprises, in comparison to other selected Baltic States, composed the biggest gross value added (% of the country’s gross value added), which was 0.2 percentage points higher than in Latvia and 0.3 percentage points higher than in Lithuania. The residents of all three Baltic States tend to participate in cultural activities; however, as the average wage after taxes remain to be lower in Lithuania than in Estonia and Latvia, this forces Lithuanians devote a larger part of it in order to satisfy leisure needs.

Statistical data analysis unquestionably confirms that cultural input when implementing sustainable development goals is significant, because there exists a very strong positive relation between the cultural value index and sustainable development goals (correlation coefficient r = 0.9992).

All three Baltic States successfully create creative industries, share positive experiences, and stress the importance of active involvement and participation of residents in cultural life. Lithuanian strategy papers note how important it is to develop information society, ensure society’s participation in cultural life, and cultural consumption.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchi, D. The Cultural Dimension of Sustainability. In Sustainability: A New Frontier for the Arts and Culture; Kagan, S., Kirchberg, V., Eds.; Verlag für Akademische Schriften: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; pp. 26–58. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, S.-C.; Marcotullio, P.J.; Piracha, A.L. Approaches to Cultural Indicators. In Urban Crisis; Nadarajah, M., Yamamoto, A.T., Eds.; UNU Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Developmentreport; Report Prepared for Commonwealth Secretariat; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.R.; Fan, P.; Chen, J. Incorporating culture into sustainable development: A cultural sustainability index framework for green buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; Jeannotte, M.S. Introduction: Culture and Sustainable Communities. Cult. Local Gov. 2011, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubadji, A.; Pelzel, F. Culture based development: Measuring an invisible resource using the PLS-PM method. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2015, 42, 1050–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.O. Information Management and Organisational Performance: A Review of Literature. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, M.; Yamamoto, A.T. (Eds.) Urban Crisis: Culture and the Sustainability of Cities; UNU Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, K.K.; DeVereaux, C. A theoretical framework for sustaining culture: Culturally sustainable entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagoeva-Yarkova, Y. The Role of Local Cultural Institutions for Local Sustainable Development. The case-study of Bulgaria. Trakia J. Sci. 2012, 10, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M. Culture as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development. An Investigation into the Process of Cultural Content Digitisation in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anheier, H.K.; Isar, Y.R.; Hoelscher, M. Cultural Policy and Governance in a New Metropolitan Age; The Cultures and Globalization Series; Sage: London, UK, 2012; Volume 5, pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, A. Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific; ANU E Press/Asia Pacific Press: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannotte, M.S.; Andrew, C. Operational Guidelines for Incorporating Culture into Sustainable Development Policies: A Canadian Perspective; Report Prepared for Department of Canadian Heritage; Canadian Heritage: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, I.; Bilinska-Reformat, K.; Grzesiak, M. Sustainable Activity of Cultural Service Consumers of Social Media Users-Influence on the Brand Capital of Cultural Institutions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Soini, K.; Fairclough, G.; Horlings, L. Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development; Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P.H.; Lin, C.T. How Should National Museums Create Competitive Advantage Following Changes in the Global Economic Environment? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciute, I. Cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Developing a New Instrument for Assessing Acceptance of Change. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Assessing workplace relational civility (WRC) with a new multidimensional “mirror” measure. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W. Evaluation of Sustainable Development: A Social Science Approach. In Sustainable Development in Europe: Concepts, Evaluation and Applications; Cornwall: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Perello-Marín, M.; Ribes-Giner, G.; Pantoja Díaz, O. Education for Sustainable Development in Environmental University Programmes: A Co-Creation Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, E.V.; Veretennikova, A.Y.; Kozinskaya, K.M. Formal Institutional Environment Influence on Social Entrepreneurship in Developed Countries. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2019, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Ciufo, B.; Nijkamp, P. A systemic framework for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. ‘Mexico City Declaration on Cultural Policies’, quoted in UNESCO. In Change in Continuity. Concepts and Tools for a Cultural Approach to Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2000; p. 25. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001216/121608EB.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse of cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning, Cultural Development Network (Vic.); Common Ground: Libraries, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horlings, L.G. The Worldview and Symbolic Dimension in Territorialisation: How Human Values Play a Role in a Dutch Neighbourhood. In Cultural Sustainability and Regional Development: Theories and Practices of Territorialisation; Dessein, J., Battaglini, E., Horlings, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chakori, S. Building a Sustainable Society: The Necessity to Change the Term ‘Consumer’. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt- Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Durand-Delacre, D.; Teksoz, K. SDG Index and Dashboards—Global Report; Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN): New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural Sustainability. In A Handbook of Cultural Economics; Towse, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-1-84064-338-2. [Google Scholar]

- Balta Portoles, J.; Dragićevic Šešić, M. Cultural rights and their contribution to sustainable development: Implications for cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregždaitė, R. The Modelling of Cultural and Creative Industries Assessment in EU Member States. Ph.D. Thesis, MRU, Vilnius, Lithuanian, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Statistics Explained. Culture Statistics—Cultural Enterprises. Prieiga per Internet. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Culture_statistics_-_cultural_enterprises#SBS_data.C2.A0:_number_of_cultural_enterprises.2C_value_added_and_turnover? (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- SDG Index and Dashboards Report. Global Responsibilities Implementing the Goals. 2018. Available online: https://sdgindex.org/reports/sdg-index-and-dashboards-2018 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).