Abstract

Vacant and/or abandoned properties exist in every city regardless of whether they are growing or shrinking, and the properties are not always a bad thing, and all underutilized land does not have to be developed. Some types of vacant land are unused but can be productive. Some may have natural resource value for inhabitants and provide green space such as parks space or green infrastructure. Once a city has too much vacant land, it may reflect a long cycle of depopulation and economic downturn. So, a lot of vacant lots is of concern in shrinking cities to change them into a valued commodity. In contrast, insufficient vacant land might hinder future growth and development. Since the vacant land can be a potential opportunity or threat to spur economic development, it is critical to understand vacancy pattern and its drivers and create appropriate policies for each city. By doing so, it would be possible to find the most effective land supply usage for cities having different characteristics and patterns of vacancy. Therefore, this study compares the pattern primary factors of vacancy of a growing city, Fort Worth and shrinking city, Chicago and evaluate whether each city has established planning policies for reducing negative effects and increasing efficient usages. The findings show that transportation and physical factors are strong determinants of the vacancy in a shrinking city, while socioeconomic conditions tend to influence more powerful on increasing vacant properties in a growing city. Furthermore, the outcomes of plan evaluation indicate that the vacancy pattern and its primary factors are grasped and handled firmly in Fort Worth.

1. Introduction

Today, the world is steadily becoming more urban as a growing number of people move to cities and a large number of structures was built in the areas. While only two percent of the world’s population lived in cities in 1800, the urban population is expected to reach 60 percent in 2030. However, the trend of urbanization is not distributed evenly, as not every city absorbs the rapid urbanization. While rapid population growth and urbanization has been a serious issue in developing cities, many former manufacturing industrial cities in developed countries have experienced serious depopulation, job loss, and economic decline in recent decades. Since vacant properties can be a critical theme to measure a collapse of economy and depopulation, the shrinking cities have been concerned for why some cities are declining more than others, and how the vacant properties in the shrinking cities can be regenerated effectively. Of course, vacant properties exist in growing cities as well. In growing cities, vacant properties can be increased at urban fringes for future growth in population and size to improve the scale of economies and urban services by a large scale of annexation. Despite these different characteristics, however, most cities regardless of whether they are growing or shrinking have pursued growth-oriented development strategies due, partially, to their inability to accurately predict future urban growth/decline patterns and establish proper vacancy related policies [1].

In this regard, this study reviews the potential role of the comprehensive plan—That describes the future developments of the communities—in reducing the vacancy issues in a growing city, Fort Worth and a shrinking city, Chicago as follow-up research. In precedent researches, three studies were conducted to (1) predict future possible vacancy scenarios for City of Fort Worth, Texas (which represents a growing city) [2] and (2) predicting City of Chicago, Illinois (a shrinking city) using Land Transformation Model [3] and (3) identifying the principal causal mechanisms affecting vacancy trends by quantifying determinants of vacancy [4]. These three previous studies found that the primary vacancy determinants are different between a shrinking city and a growing city. While market conditions and economic statuses such as housing value, unemployment rate, and income are the most influential variables affecting vacant land transformation in Fort Worth, transportation systems and physical conditions such as proximity to highway and year structure was built play a larger role in Chicago. However, how well the planning interventions and policies contribute to ease the vacant issues was limited. The outcome of this study is expected to set up the right direction in future plans for the reduction of urban vacancy and its consequences.

Understanding local urban issues precisely and suggesting suitable planning policies is an important role of planners and decision-makers. To understand whether planning mechanisms have been sufficiently implemented in practice, this study suggests a newly developed plan evaluation protocol based on the future possible vacancy scenarios.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Growing Cities and Shrinking Cities

While the term about urban growth has been widely discussed, the definitions, measurements, and symptoms have been categorized quite differently, depending on the time, space and communities. Thus, it is difficult to identify both growing and shrinking cities with a single general concept.

A growing city is often recognized as a city experiencing rapid population and economic growth and increase in neighborhood quality [3,5,6,7]. Generally, since growing economies induce with increasing the demand and supply of both works and consumers, the economic growth is strongly associated with population growth. Therefore, most planning and economic literature define a growing city as a city experiencing population and employment growth for a certain time period, while shrinking cities as the opposite.

The population is also the most popular tool in defining and identifying the shrinking city. Schilling and Logan (2008) defined a shrinking city as older industrial city losing population more than 25% over the last 40 years, and the Shrinking Cities International Research Network (SCIRN) also defined shrinking cities as an urban area with more than 10,000 residents that have experienced depopulation for more than two years and the consequential economic crisis [8,9]. Among cities in the U.S. with populations of at least 50,000, the list of the 10 fastest shrinking and growing cities between 2014 and 2016 was announced by the U.S Census Bureau. The Census Bureau noted that the fastest shrinking cities were scattered around the Midwest and South, while the fastest growing cities were predominately in Texas. This report also identifies the urban growth trends between 2000 and 2010 with population growth by cities with more than 250,000 population. Among 62 cities having at least 250,000 population in 2000 in the U.S., Fort Worth recorded the largest population growth, 206,512 people for a decade, while Detroit and Chicago lost over 200,000 people Chicago between 2000 and 2010.

Depopulation itself would not be an issue to a city, or an indicator of unhealthiness of a city [10], if a city is planned right, but negative consequences such as a reduction of tax revenue, a decrease of urban vitality, or an increase of vacant homes [11,12].

2.2. Vacant Land

Every city makes efforts to promote economic growth using a number of resources. Among those resources, land plays an important role, especially vacant land [13]. However, there is a multitude of ways to define and measure vacant properties; it can be defined by the situation, municipality, function of the parcel, and/or duration of vacancy (see Table 1). Sometimes, only urban properties deemed difficult to develop are considered as vacant land, while abandoned or brownfields parcels including industrial, commercial or residential sites/buildings are also designated as vacant land in some cases. Furthermore, open space with particular natural resource value such as park and farm sites are also included as the vacancy in some studies.

Table 1.

Definition and Description of Vacant Land in Previous Literature.

The National Vacant Properties Campaign (NVPC) defines vacant properties if one or both of the following characteristics was met: “The site poses a threat to public”, and/or “the owners or managers neglect the fundamental duties of property ownership (e.g., they fail to pay taxes or utility bills, default on mortgages, or carry liens against the property.)” [14] p. 1. Based on the literature, vacant land includes not only underperforming or empty properties but also neglected and abandoned residential, commercial and industrial buildings/properties that have been beyond repair over a year to threaten a public safety. The latter vacant properties would be a concern for planners, particularly in shrinking cities.

The depopulation could be occurred by different sorts of causes such as suburbanization, the demographic cliff, natural hazard, or inner-city decline and suburbanization, which eventually resulted in an increase of unoccupied vacant homes and structures. These abandoned structures would be a concern of shrinking cities with less capacity to reuse these abandoned properties than growing cities. Aesthetic quality and properties around these abandoned structures might decrease. Increased crime and arson would harm the whole community. The outmigration of neighbors could sabotage the capital of community. Government, community members, and planners had added great efforts to tackle the urban vacancy. Some cities, like Detroit, have attempted to bring big enterprise to the downtown as an anchor for urban regeneration. But this kind of effort cannot always be successful, especially in small shrinking cities with fewer resources. Rather, cities took the simple and temporary approaches such as demolition, refurbishment, or a conversion to community garden, while waiting the city would get sufficient capacity to regenerate the whole area. After then, policy and government-driven interventions were found. Chicago established Cook County Land Bank and attempted to redevelop and remodel vacant homes through Neighborhood Stabilization Program [15]. UK also collects vacant property data to identify and manage the vacant houses efficiently [16]. Japan and Korea enacted Vacant Housing Law in 2015 and 2018 respectively, which remediate annoyances of urban vacancy lawfully [17]. As a part of regeneration efforts, cities attempted to respond to vacant housing issues and the planning interventions have been evolved from temporary and community-based solutions to policies and laws.

2.3. Plan Evaluation

Development management is the deliberated and integrated government program designing to achieve broad public interest goals by controlling the type, quality, scale, rate, sequence or timing of development [18,19,20]. As low-density suburban developments were spread out around most cities during the postwar era, uncontrolled and wasteful consumption of land and resources by single-use development became a problem. Meanwhile, the needs of reasonable development management have also arisen across communities, regions, and states to address the issues directly and growth management programs were developed to achieve orderly urban growth, preservation of green space and natural resources, and efficient transportation systems [19].

In this sense, planning can also play an important role in guiding land use and development in areas having a high risk of vacancy issue. However, despite many policies and strategic plans that have been put in place for inner-city revitalization, conventional market-based redevelopment policies aggravate market dysfunction, chronic decay, and disinvestment due to the lack of understanding of each city’s situation [9,13]. Thus, it is critical to find different causes and effects of the vacancy in each city and suggest appropriate policies.

Previous literature is in rich to evaluate the contents of comprehensive plans. In particular, rational basis of plans, called factual basis, goals and objectives, and planning tools and strategies are the most frequently examined items of plan documents [21]. The items for evaluation under each category can be retrieved from previous studies and a city or community could get a ‘plan score card’ based on these evaluation items. Heim LaFrombois, Park and Yurcaba [11] examined the planning strategies for pro-growth, maintenance, and smart decline with 33 planning tools. Berke and Conroy [15] assessed 30 comprehensive plans’ policies and strategies to reveal whether they sufficiently support the key principles of sustainable development. By using their newly developed coding scheme, which scales from 0–2, they could readily score the level of existing policy achievements. Particularly, this evaluation coding protocol has been widely employed and applied in assessing various fields of local/regional plans. Godschalk et al. [22] expanded the previous three plan components approach into five by including inter-organizational coordination and implementation elements. Using this expanded method, several studies measured the degree and quality of local plans in diverse fields, such as ecosystem management, coastal zone land use planning capacity, and drought preparedness [23,24,25]. Kim et al. [17] adopted five plan components, including policies and implementation tools, in order to evaluate whether rapidly growing municipalities in US substantially incorporate the concepts of green infrastructure planning. Rather than assessing the quality of the plan itself, some studies attempted to examine the implementation effects of a plan. Laurian et al. [26,27] discerned how land development permitting processes followed the existing development policies of a plan in New Zealand by adopting a conformance-based method. Berke et al. [28] examined the networks of local plans toward hazards vulnerability and climate change by adopting a newly developed resilience scorecard and found that the contents of local plans were likely to be inconsistent and vulnerable areas to flood did not sufficiently create mitigation strategies/policies. As discussed above, previous plan assessments are imperfect because of self-selected criteria. However, they could guide local governments in ways that mediate facing challenges and quality of life by multiple jurisdictions [29,30].

3. Literature Gaps and Research Objective

Even though many studies on the vacant land were conducted over the last fifty years and explained the relationship between vacancy and urban shrinkage, existing research has the following limitations.

First, most studies have focused on physical and economic aspects such as depopulation and unemployment rate as the primary factors for a growing amount of vacant properties. However, the problem of population loss is not about size itself, but about who is leaving and who is staying. While some studies examine how socioeconomic status has influence on vacancy in a declining city, only a small number of existing studies attempt to explain the relationships between a mix of physical, economic, and social characteristics and vacant land. While most of the studies describe the demographic trends of a region, it is difficult to find any literature on assessing the statistical significance of those factors. Based on the literature, 18 different driving factors are identified as the principal causal mechanisms contributing to vacant urban land, not only physical but also socio-economic and environmental characteristics.

Second, some studies have also recognized the seriousness of vacancy issues and analyzed the spatial pattern of vacant land to suggest better solutions. However, since they only focus on historical vacancy pattern trends, it is questionable if the policies and strategies work in the future. Although there are three studies to predict future possible vacancy scenarios [3,4,31], they fail to explain how the prediction outputs can be applied in real urban planning systems. Thus, this research evaluates how well comprehensive plans have reflected the vacancy issue in vulnerable areas of both growing and shrinking cities.

Third, a local comprehensive plan has been employed from various prior studies as an effective measure to assess a community’s long-range visions and preparedness for future developments. Starting from early 1990s, many previous studies assessed diverse topics, including natural hazards [32,33,34,35], affordable housing [36], green infrastructure [37], land use pattern [38], new urbanism [39], sustainable development [21,40], smart growth [41], and urban sprawl [42]. These studies, however, have mostly adopted the content analysis method that was generally relying on Kasier et al.’s plan evaluation approach [43]. In addition, the fields of previous plan evaluation lacked on assessing issues related to shrinking cities and vacant lots. While evaluating the quality of plan can provide insightful lessons to local planners and decision-makers, it is more critical for us to understand whether planning mechanisms have been sufficiently and successfully implemented in practice. This study attempts to examine the plan implementation effect by employing a newly developed plan evaluation protocol.

4. Methods

4.1. Selection of Cities

For the first part of the research, the city of Fort Worth, TX and the city of Chicago, IL were selected as study areas to compare how well vacancy related policies have been created and adopted in vulnerable areas between a growing city and a shrinking city. As mentioned above, Fort Worth is one of the fastest growing cities, while the city of Chicago has suffered severe depopulation and economic crisis, losing over 920,000 people from its peak year.

The U.S. Census Bureau indicates that the population of the city increased by 206,512 persons (+37%) between 2000 and 2010 becoming the fastest growing large city with more than 250,000 population (see Table 2). The rapid population growth is forecasted to continue considering the immigration and domestic migration enhanced by a strong economy. In contrast, Chicago will lose more than 1 million people between 1950 and 2020, which only two municipalities worldwide have experienced, London and Detroit [4,44]. In spite of Chicago’s depopulation rate, decline related issues in the city have been relatively overlooked compared to other shrinking cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Baltimore. Thus, Fort Worth and Chicago are selected as examples of growing and shrinking cities (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 10 Growing Cities with more than 250,000 Population from 2000 to 2010. Top 10 Shrinking Cities with more than 250,000 Population from 1980 to 2010.

4.2. Variable Influence in Two Types of Cities

To evaluate the vacancy related plan quality, the variable influence output from our previous research was utilized [4]. Using 2000–2010 input data, two statistical results (PCM and Kappa) were calculated by dropping one variable for each city, Fort Worth and Chicago, and then, the differences in variable influences were compared between those two cities.

Different input factors that contribute to vacant land increase were selected due to the data capabilities of each city. While 18 rasterized variables were utilized for the City of Chicago, Fort Worth used 16 input factors, excluding mobile home rates, crime rates, and vehicle availability. Table 3 displays the variable influence (highest to lowest) by city and the difference in the influence between these two cities. In Chicago, transportation physical variables such as proximity to highway, vehicle accessibility and median year structure built are powerful determinants of vacancy, while personal wealth and socioeconomic variables such as housing value, unemployment rate, race, and household income have a stronger influence on the model than other factors in Fort Worth. This indicates that creating transportation and accessibility-related policies might be effective methods in dealing with vacancy issues in a shrinking city, and policies to reduce social and racial segregation can be an alternative in a growing city.

Table 3.

Difference of Variable Influence between Fort Worth and Chicago.

4.3. Comprehensive Plan Evaluation by Planning District

To demonstrate how well a comprehensive plan has considered the driving factors of vacancy and created appropriate policies, we begin to identify planning districts. Since most local plan policies are coordinated by planning districts such as residential neighborhoods, downtowns, and commercial corridors, the geographic districts are relevant units of analysis to examine each plan’s quality [28,45]. Using GIS software, the planning districts are intersected, and the variable data are recalculated to identify which districts are socially and physically vulnerable (high poverty rate, low income, and educational attainment, high rates of building deterioration, high risk of vacancy, etc.). Then, we select the most vulnerable districts and the wealthiest districts to evaluate how well the comprehensive plans support the vulnerable districts to reduce vacancy issues.

Since a comprehensive plan is a process and tool used to guide communities’ future land use decisions, seeking to balance development pressure with preservation for long-term economic health and quality of life, it includes all land in its regulatory jurisdiction and also consider all physical developments of the community [30]. Thus, we evaluate each community’s comprehensive plan to determine the extent to which local policies contribute to reducing vacancy and vulnerability by districts, following well-established plan content analysis procedures [46]. First, each vacancy related policy is classified by planning districts if the policy reduces/increases the vulnerability and obtains +1/−1 score. Next, we sum scores to create an index score by variables. Higher total scores indicate that the community creates more policies aimed at reducing vacancy, while zero scores indicate that there are no vacancy related policies by a variable within a district. Table 4 shows an example of how plan policies are classified and scored. Since proper and effective planning policies for reinvestment and revitalization of central cities would contribute to slow down sprawl and solve the depopulation and vacancy issues, the outcomes of this study would provide a strong guidance by quantifying the quality of the planning process and the strength of its implementation.

Table 4.

An Example of Plan Policy Method, Fort Worth, TX.

5. Results

5.1. Vacancy Related Plan Evaluation

Based on the results of quantifying the effect of each factor through model performance in Section 4.2, we evaluate comprehensive plans to determine how well the primary factors contributing to vacancy are reflected existing plans in both growing and shrinking city. A local comprehensive plan is composed of two parts: (1) analysis of existing conditions and trends and (2) goals, objectives and policies. Since “existing conditions and trends” provides a foundation and basis for the formulation of “goals, objectives, and policies” by indicating the current status and problems of the local community, both “existing conditions” and “goals” sections should be reviewed.

This section consists of three processes: (1) regenerating socioeconomic status, and vacancy trends in current and future (2020) in each city by planning districts using a tool, Geospatial Modeling Environment (GME), (2) finding one(or two) of the most socially and physically vulnerable planning districts, and one(or two) of the wealthiest and healthiest communities, (3) evaluating comprehensive plans to determine how well their plans take into account current vacancy related problems by comparing wealthy-occupied and vulnerable-vacant communities of each city considering the variable influence outputs.

The results indicate that the cities place a greater emphasis on economic revitalization in vulnerable districts than in healthier communities in both growing and shrinking cities. Fort Worth has 123 policies/strategies which are associated with vacant properties. Among them, 63 policies cover South East, one of the most vulnerable districts in Fort Worth, that aim to revitalize the economy and reduce vacant properties. Also, 50 of the policies in South East closely correspond to neighborhood market conditions and socioeconomic statuses such as stabilization of property value and job markets which are stronger predictors of vacant land in the City of Fort Worth. Therefore, Fort Worth recognizes the vacancy issue in socially and physically vulnerable districts and provide diverse policies and strategies to revitalize these areas and reduce vacant properties.

In contrast, the City of Chicago does not have a city-level comprehensive plan. Rather, they have a comprehensive regional plan for the Chicago metropolitan area including 7 counties and 284 communities. Since the plan could not be evaluated at the neighborhood level, we reviewed the plan to determine how well it considers the vacancy issue at a city level. The variable influence test suggests that transportation system and physical condition are the most influential variables affecting vacancy transformation in Chicago while most personal wealth related variables have marginal influence predicting vacancy in the city. However, the results show that the city makes a greater effort to improve socioeconomic status than mobility and physical characteristics. Among 65 vacancy-related policies of the regional comprehensive plan, nineteen policies strived to improve the public transit system, highway system and physical condition of structures while thirty-nine policies targeted socioeconomic status, aiming to increase income and educational attainment and decrease the unemployment rate and poverty. Therefore, to overcome the chronic vacancy issue in Chicago, they would need to highlight policies to improve mobility and physical conditions of structures.

5.1.1. The City of Fort Worth

The Fort Worth 2017 comprehensive plan contains guidance for making decisions about growth and development relating to 22 functional sectors, including land use, housing, transportation, infrastructure, conservation, recreation and open spaces, and capital improvement. The comprehensive plan describes future development patterns and population projections for the city and protects natural and cultural resources for present and future generations. Among the 22 subsections of the plan, 12 different sections dealing with vacancy issues were reviewed: land use, housing, capital improvements, financial incentives, parks and community services, critical facilities (libraries, police services, fire, and fire and emergency services), economic development and transportation (See Table 5).

Table 5.

City of Fort Worth 2017 Comprehensive Plan Chapters & Vacancy-Related Topics.

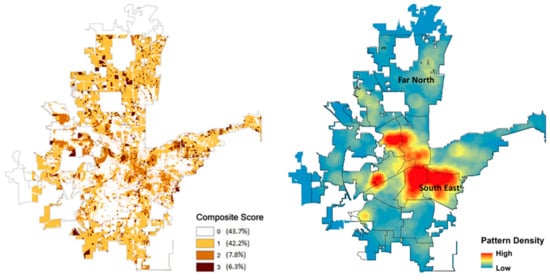

Since the City of Fort Worth has been divided into 16 districts for planning purposes, the current socio-economic and vacancy status of each district were regenerated based on the districts using a tool, GME. Considering the analytical outputs of physical, social, and economic circumstances of the neighborhoods, Far North (FN), one of the highest risks of vacancy and socially vulnerable district and South East (SE), one of the lowest risk of vacancy and wealthy district were selected among the 16 planning districts to evaluate how well the comprehensive plan reflects the vacancy issues in the vulnerable district. The poverty rate in the SE (31%) is about six times higher than FN (5%), the median household income ($28,374) is three times lower ($83,367), the unemployment rate (14%) is three times higher (5%), and the crime rate per 100,000 people (814) is twice as high (429). Consequently, these indicators show that South East district needs careful and specific planning policies to reduce vacancy rate, improving economic outcomes and developing safe communities (See Figure 1, Table 6, and Table A1 and Table A2).

Figure 1.

Prediction Composite Score and Pattern Density Map by District in Fort Worth, TX.

Table 6.

2010 Socioeconomic Status of Four Selected Planning District (Fort Worth).

The variable influence outputs indicate marketing conditions and economic variables such as housing value, unemployment rate, ethnicity, and income have a greater influence on vacant land transition than most other factors. On the other hand, industry quotient (secondary and service industry), poverty and age of buildings did not seem to be strongly influential when predicting for vacant land in the City of Fort Worth. Thus, the basic policy direction on vacant land in the city should focus on socio-economic and industrial conditions such as improving economic opportunities and conditions and reducing racial segregation.

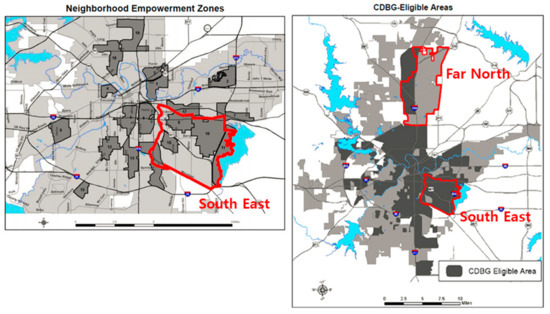

Table 7 displays the number of vacancy-related policies by variables in their order of influence from high to low. It indicates that the comprehensive plan of the city provides 123 vacancy related policies/strategies, and among them, 63 (or 51%) policies were created for South East where is one of the most vulnerable districts in Fort Worth, and 41 of 63 policies were associated with economic growth or quality of life such as reducing the unemployment rate, poverty, and increasing income. Especially, in order to improve the local environment and revitalize the economy of socially and economically vulnerable districts, Fort Worth adopted diverse housing policies and development incentives programs to increase the supply of quality housing and expand homeownership opportunities. For example, through Neighborhood Empowerment Zones (NEZs) program and Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funds, local development activities were planned for low to moderate income households such as affordable housing and infrastructure development within South East district (See Figure 2).

Table 7.

The Number of Vacancy-related Policies/Strategies of Two Selected Districts (Fort Worth). (Sorted in order of greater to smaller variable influences).

Figure 2.

An Example of Spatial Indicators: 19 Neighborhood Empowerment Zones (NEZs) * and Census Tract-based Community Development Block Grant (CDBG)-Eligible Areas **.

* Neighborhood Empowerment Zones (NEZs): An area to revitalize the central city through development incentives: promote (1) the development and rehabilitation of affordable housing within the zone; (2) an increase in economic development within the zone; and (3) an increase in the quality of social services, education, or public safety provided to residents of the zone. 20 NEZs have been designated by the City Council [47] p. 226.

** CDBG Eligible Area: Census tract in which fifty-one percent (51%) or more of the residents in that census tract have low to moderate incomes as defined by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development ([47] p. 214).

5.1.2. The City of Chicago

GO TO 2040 is the long-range comprehensive regional plan for the Chicago metropolitan region that includes 7 counties and 284 communities by Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) which is the official regional planning organization for the northeastern Illinois counties. Based on the region’s existing challenges and opportunists, the comprehensive plan contains 12 functional sectors including land use, housing, parks, and open space, sustainable local food, capital improvements, governance, and transportation. Among those 12 high-priority sections, 7 chapters are reviewed which are associated with vacant properties: land use, housing, parks, and open space, sustainable local food, education, workforce development, and transportation (See Table 8). Since Chicago only provides a larger scale regional plan, they do not contain enough specific spatial indicators for the City of Chicago. Thus, although the city of Chicago has been divided into seventy-seven districts for planning purpose, we are only able to evaluate the comprehensive plan without considering specific districts of Chicago.

Table 8.

City of Chicago 2040 Comprehensive Plan (Go To 2040).

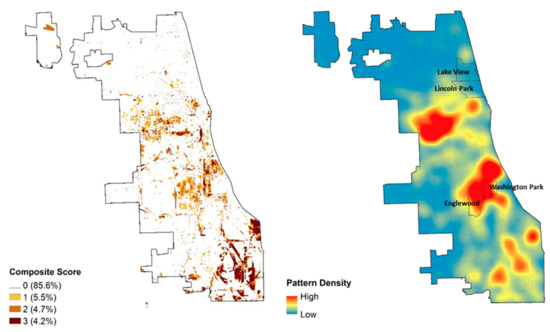

Figure 3 indicates that there is a higher risk of a vacancy in neighborhoods surrounding the downtown area and the industrial communities in the Southeast region. Especially, the 2020 scenarios predicted that 69% of Englewood and 41% of Washington Park might have a probability of future vacancy, while only 3% of Lake View and 4.7% of Lincoln Park were predicted to become vacant in 2020. Moreover, looking at the long-term (over 24 months) vacancy rate by districts, the average long-term vacancy rate between 2010 and 2014 in Englewood (9.2%) and Washington Park (7.1%) were higher than Lake View (1.3%) and Lincoln Park (1.5%). The socioeconomic status of each district also shows how Englewood and Washington Park are socially and physically vulnerable compared to Lake View and Lincoln Park. Over 98% of the population in Englewood and Washington Park were African American in 2010, while Lake View and Lincoln Park had less than 5%. Both income and housing value of those vulnerable districts are less than 30% of the wealthy neighborhoods. Furthermore, the poverty rate (43%) is about four times higher (11%), the unemployment rate (22%) is four times higher (5%), and the crime rate per 100,000 people (11,662) is twice as high (5151). Under the circumstances, Englewood and Washington Park need careful and specific planning policies for reducing vacancy rate, improving economic outcomes and providing a safe community (See Table 9 and Table A3 and Table A4).

Figure 3.

Prediction Composite Score and Pattern Density Map by District in Chicago, IL.

Table 9.

2010 Socioeconomic Status of Four Selected Planning District (Chicago).

As mentioned above, however, since the regional plan of the Chicago metropolitan area does not provide specific policies for each district of Chicago city, it was not able to evaluate the comprehensive plan at the neighborhood level. Therefore, a broad evaluation of the entire city was conducted without considering spatial indicators. Table 10 displays the number of policies which are associated with vacancy by plan category.

Table 10.

The Number of Vacancy-related Policies/Strategies of Chicago. (Sorted in order of greater to smaller variable influences).

The variable influence test in Section 5.1 indicates that mobility and public transportation, housing condition, and crime seemed to have a stronger influence on increasing/decreasing vacant land, while some economic variables such as unemployment rate and income are influential, but only marginally when predicting for vacant land of Chicago. Thus, the basic policy direction on the vacant land of the city should be focused on improving transportation networks and promoting the rehabilitation of older housing stock to increase housing values and reduce crimes for Chicago.

Due to the recent economic downturn, metropolitan Chicago faces fiscal pressures, damaging quality of life and created various policies and strategies to revitalize the economy. The result of plan evaluation indicates that workforce development is recognized as one of the most important factors to revitalize their economy. Among 65 vacancy-related policies, 27 policies were obtained from “Improve education and workforce development” section which addresses the high-quality labor force and reducing differences between racial groups in terms of income, educational attainment and many other measures. Furthermore, 19 policies are suggested to improve the public transit system and highway systems focusing investments on maintenance and modernization.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This research seeks to use a newly developed plan evaluation tool by predicting future outcomes of vacancy. Based on quantifying the effect of each factor on model performance in the previous study, each city’s comprehensive plan was evaluated to determine how well the primary factors of urban vacancy contributing to vacancy are reflected in policies in vulnerable districts compared to wealthy districts in shrinking and growing cities.

To summarize findings from analyses, this research reveals some interesting trends. First, while socioeconomic status related variables such as ethnicity, income and unemployment rate are stronger predictors of vacancy in Fort Worth, transportation and physical status related variables including proximity to highway and vehicle accessibility show a stronger influence on increasing vacant land in Chicago. Second, both cities have attempted to understand the causes and impacts of vacancy issues and suggested diverse planning policies. The plan evaluation outcomes indicate that Fort Worth has diagnosed the vacancy issue and its causes in socially vulnerable planning districts and established various vacancy related planning policies. Although Chicago might have a thorough grasp of the problem, the city doesn’t seem to have transportation and/or physical status related planning policies at planning district level. Thus, Chicago might need more specific and cause-based planning policies to revitalize vulnerable districts.

Overall, this study strived to quantify the influence of each driving factors and provide initial solutions that can be utilized in future projects. This study has not only supported methodological frameworks to predict future vacancy pattern and quantify the influence of each factor but has also explored theoretical and practical connections between planning and policy implementation.

Although this study provides a greater opportunity to create policies considering future spatial pattern trends, some limitations remain that should be furthered in the future study. First, since this study only dealt with two cities, Fort Worth and Chicago, the relatively small sample size may not be able to generalize conclusions with statistical power to all municipalities. Therefore, the study area needs to be extended to other communities facing rapid growth in population/size and/or experiencing serious deindustrialization and depopulation.

Second, in terms of evaluating vacancy-related plan quality by districts, while Fort Worth provides a city-level comprehensive plan, Chicago has a regional comprehensive plan for the Chicago metropolitan region that includes 7 counties. Since the regional plan does not provide specific policies or strategies by planning district in the city of Chicago, it is difficult to determine how well the existing policies consider the socially and physically vulnerable neighborhoods.

Lastly, the comprehensive plan is a tool used to guide overall future land use decisions, evaluating only the comprehensive plan may not be comprehensive enough to understand a city’s vacancy-related policies. If cities have small area programs or plans regarding depopulation or vacant properties such as central area revitalization plans, parks, and open space plans and transportation plans, it may useful to include these in future studies.

This is only a starting point for understanding the overall vacant land transformation. Further research is needed to extend study areas, define key terminologies, collect better data and provide more applicable policy implications.

Author Contributions

J.L. outlined the methodology, conducted the analysis, pre-processed data and wrote the manuscript. Y.P. substantially contributed to the design of the study, key suggestions for improving the methods and editing the manuscript. H.W.K. performed the analysis and interpreted the results.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea grand number [NRF-2018R1C1B50310512].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

2020 Future Vacancy and 2010–2014 Long-term (24+ months) Vacancy by Planning District (Fort Worth).

Table A1.

2020 Future Vacancy and 2010–2014 Long-term (24+ months) Vacancy by Planning District (Fort Worth).

| District | 2020 Predicted Composite Score | Long-Term (24+ months) Vacancy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Arlington Heights | 18.6% | 17.3% | 3.7% | 39.7% | 3.5% | 4.7% | 6.1% | 6.2% | 5.6% |

| Downtown | 36.2% | 17.5% | 2.6% | 56.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 2.0% | 1.8% | 2.3% |

| Eastside | 41.8% | 7.4% | 8.5% | 57.7% | 1.3% | 2.2% | 3.4% | 3.9% | 3.6% |

| Far North | 30.4% | 19.8% | 6.0% | 56.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Far Northwest | 60.4% | 3.9% | 8.3% | 72.6% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Far South | 63.3% | 5.5% | 4.6% | 73.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| Far Southwest | 70.2% | 0.4% | 7.9% | 78.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Far West | 36.3% | 16.9% | 5.8% | 59.1% | 0.3% | 1.4% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 1.8% |

| Northeast | 35.1% | 11.1% | 6.1% | 52.4% | 2.8% | 3.0% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 3.5% |

| Northside | 27.4% | 17.9% | 6.8% | 52.0% | 3.6% | 4.8% | 5.6% | 5.8% | 5.4% |

| South East | 65.2% | 2.4% | 9.8% | 77.4% | 4.1% | 5.4% | 6.8% | 7.4% | 6.9% |

| Southside | 25.4% | 19.2% | 5.8% | 50.4% | 4.6% | 5.7% | 6.9% | 6.7% | 6.2% |

| Sycamore | 51.3% | 4.0% | 4.5% | 59.9% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 2.1% | 2.2% | 2.3% |

| TCU West Cliff | 23.0% | 7.5% | 1.9% | 32.4% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 1.9% | 1.5% |

| Wedgwood | 28.8% | 4.8% | 4.2% | 37.7% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 0.8% |

| Western Hills-Ridglea | 22.1% | 4.2% | 3.3% | 29.6% | 3.6% | 5.1% | 6.4% | 6.4% | 6.5% |

| Fort Worth (City) | 44.8% | 8.4% | 6.7% | 60.0% | 1.5% | 2.4% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.0% |

Table A2.

2010 Socio-economic Status by Planning District (Fort Worth).

Table A2.

2010 Socio-economic Status by Planning District (Fort Worth).

| District | Race 1 | Education 2 | Unemploy. | Income 3 | Vacancy | Value 4 | Poverty | Ownership | Mobile Home | Crime 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arlington Heights | 12.6% | 17.6% | 6.8% | $47,415 | 12.4% | $166,191 | 16.6% | 49.5% | 0.1% | 1644 |

| Downtown | 24.4% | 17.7% | 5.3% | $51,196 | 16.7% | $236,800 | 21.0% | 13.8% | 1.1% | 3774 |

| Eastside | 33.8% | 18.0% | 9.6% | $46,268 | 13.2% | $119,948 | 15.8% | 44.6% | 1.6% | 4643 |

| Far North | 8.8% | 6.9% | 5.2% | $83,367 | 4.8% | $164,606 | 4.8% | 74.2% | 2.4% | 3358 |

| Far Northwest | 7.8% | 10.6% | 8.1% | $71,811 | 8.7% | $144,348 | 7.1% | 74.8% | 1.7% | 4065 |

| Far South | 26.9% | 10.9% | 5.5% | $65,559 | 9.0% | $125,163 | 9.6% | 73.4% | 3.9% | 4482 |

| Far Southwest | 20.6% | 6.7% | 4.6% | $95,884 | 5.6% | $189,249 | 3.8% | 85.8% | 0.6% | 1729 |

| Far West | 9.6% | 14.4% | 6.5% | $59,124 | 7.2% | $102,276 | 9.2% | 60.9% | 1.4% | 3602 |

| Northeast | 9.1% | 50.7% | 9.9% | $33,836 | 10.9% | $73,534 | 25.5% | 56.5% | 0.5% | 5913 |

| Northside | 3.2% | 53.7% | 9.4% | $199,857 | 14.2% | $72,133 | 27.1% | 48.9% | 3.8% | 6036 |

| South East | 36.9% | 42.8% | 14.0% | $28,374 | 14.3% | $52,551 | 31.2% | 52.0% | 6.6% | 6368 |

| Southside | 16.8% | 44.6% | 12.7% | $29,268 | 14.8% | $75,547 | 37.7% | 43.9% | 0.5% | 5634 |

| Sycamore | 28.5% | 31.3% | 10.6% | $40,120 | 12.0% | $82,577 | 26.4% | 53.1% | 3.9% | 5566 |

| TCU West Cliff | 3.4% | 7.0% | 5.9% | $60,563 | 9.7% | $282,905 | 14.5% | 46.6% | 0.6% | 1644 |

| Wedgwood | 22.1% | 9.6% | 6.0% | $55,048 | 9.3% | $144,063 | 10.8% | 49.3% | 0.2% | 3645 |

| Western Hills-Ridglea | 12.5% | 18.1% | 9.2% | $39,795 | 16.3% | $138,401 | 19.5% | 34.0% | 0.3% | 3732 |

| Fort Worth (City) | 18.7% | 21.9% | 8.2% | $61,436 | 11.0% | $131,854 | 17.4% | 53.2% | 1.8% | 4111 |

Race 1: African American %, Education 2: Less than high-school graduate %, Income 3: Median household income, Value 4: Median house value, Crime 5: Crime/100,000 pop.

Table A3.

2020 Future vacancy and 2010–2014 long-term (24+ months) Vacancy by Planning District (Chicago).

Table A3.

2020 Future vacancy and 2010–2014 long-term (24+ months) Vacancy by Planning District (Chicago).

| District | 2020 Predicted Composite Score | Long-term (24+ Months) Vacancy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Albany Park | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 1.8% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 2.1% | 2.6% |

| Archer Heights | 3.7% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 4.6% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.7% |

| Armour Square | 2.8% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 9.1% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 1.0% |

| Ashburn | 4.0% | 5.7% | 0.0% | 9.6% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.2% |

| Auburn Gresham | 7.2% | 5.9% | 0.0% | 13.1% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 3.2% | 3.9% | 4.1% |

| Austin | 34.8% | 13.3% | 3.0% | 51.0% | 2.6% | 2.3% | 2.8% | 3.2% | 3.1% |

| Avalon Park | 1.6% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 2.9% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 2.5% | 2.8% | 3.3% |

| Avondale | 1.9% | 1.5% | 0.1% | 3.5% | 3.2% | 2.1% | 1.7% | 2.3% | 2.2% |

| Belmont Cragin | 0.9% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 1.9% |

| Beverly | 0.3% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 1.2% |

| Bridgeport | 7.1% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 10.3% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.6% |

| Brighton Park | 4.2% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 5.3% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 1.7% |

| Burnside | 2.9% | 4.4% | 0.0% | 7.2% | 3.9% | 4.4% | 5.1% | 4.9% | 5.2% |

| Calumet Heights | 4.4% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 8.4% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 2.5% | 3.0% | 2.9% |

| Chatham | 9.1% | 3.3% | 0.0% | 12.4% | 3.2% | 3.3% | 4.8% | 4.5% | 4.8% |

| Chicago Lawn | 4.3% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 7.5% | 2.9% | 3.5% | 4.3% | 4.1% | 4.3% |

| Clearing | 2.1% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 3.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 1.3% | 1.1% |

| Douglas | 9.0% | 6.6% | 6.1% | 21.7% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| Dunning | 3.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 7.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.8% |

| East Garfield Park | 20.5% | 16.1% | 0.0% | 36.6% | 3.9% | 3.5% | 4.1% | 4.4% | 5.3% |

| East Side | 5.8% | 5.9% | 0.0% | 11.7% | 2.8% | 3.1% | 3.6% | 3.4% | 3.1% |

| Edgewater | 0.0% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 0.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.8% | 1.7% |

| Edison Park | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 1.3% |

| Englewood | 55.4% | 13.6% | 0.0% | 69.0% | 8.6% | 9.3% | 9.8% | 10.1% | 8.4% |

| Forest Glen | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Fuller Park | 8.4% | 2.7% | 1.9% | 13.0% | 10.4% | 7.4% | 5.0% | 6.2% | 8.0% |

| Gage Park | 1.6% | 2.3% | 0.0% | 3.9% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.7% | 2.0% | 1.7% |

| Garfield Ridge | 1.9% | 8.5% | 0.0% | 10.4% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.9% |

| Grand Boulevard | 23.2% | 25.1% | 14.6% | 62.9% | 5.3% | 6.2% | 7.2% | 5.5% | 4.4% |

| Greater Grand Crossing | 12.6% | 3.9% | 0.0% | 16.5% | 4.5% | 5.0% | 6.0% | 6.1% | 5.8% |

| Hegewisch | 14.3% | 27.1% | 0.0% | 41.4% | 1.9% | 2.2% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.9% |

| Hermosa | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 2.4% | 2.6% | 2.1% |

| Humboldt Park | 23.2% | 13.2% | 3.2% | 39.6% | 4.3% | 3.8% | 4.2% | 4.8% | 4.3% |

| Hyde Park | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 2.2% | 2.4% | 3.2% | 2.5% | 1.4% |

| Irving Park | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 2.1% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.9% | 1.9% |

| Jefferson Park | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.3% |

| Kenwood | 6.7% | 5.1% | 0.7% | 12.5% | 3.3% | 3.0% | 3.6% | 2.6% | 1.9% |

| Lake View | 2.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 1.4% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 1.4% |

| Lincoln Park | 1.8% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 4.7% | 2.1% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.5% |

| Lincoln Square | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.3% |

| Logan Square | 8.1% | 5.4% | 0.3% | 13.8% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.7% |

| Loop | 3.0% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 4.9% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 3.4% | 2.5% | 1.1% |

| Lower West Side | 6.6% | 8.6% | 0.0% | 15.2% | 2.8% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 2.8% | 3.4% |

| McKinley Park | 0.7% | 2.4% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Montclare | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.2% | 1.3% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.9% |

| Morgan Park | 3.3% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 6.7% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 2.5% | 2.7% |

| Mount Greenwood | 0.3% | 4.4% | 0.0% | 4.7% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| Near North Side | 14.0% | 14.7% | 0.0% | 28.7% | 1.6% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Near South Side | 10.8% | 8.8% | 0.0% | 19.7% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 2.1% | 2.5% | 1.7% |

| Near West Side | 30.6% | 38.7% | 0.0% | 69.3% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.3% |

| New City | 38.8% | 36.1% | 0.0% | 74.9% | 6.0% | 4.7% | 5.8% | 6.7% | 8.0% |

| North Center | 1.3% | 2.7% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 3.2% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 1.7% |

| North Lawndale | 36.0% | 16.3% | 0.0% | 52.3% | 3.9% | 3.3% | 4.0% | 4.9% | 5.4% |

| North Park | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Norwood Park | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% |

| Oakland | 7.0% | 7.8% | 3.7% | 18.5% | 3.7% | 4.2% | 5.1% | 3.3% | 1.5% |

| O’Hare | 1.9% | 18.7% | 0.0% | 20.6% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.0% |

| Portage Park | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 1.8% |

| Pullman | 5.5% | 7.8% | 0.0% | 13.3% | 4.5% | 3.6% | 5.5% | 5.4% | 5.8% |

| Riverdale | 16.2% | 11.2% | 0.0% | 27.4% | 28.3% | 25.0% | 23.0% | 23.2% | 25.3% |

| Rogers Park | 0.3% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 1.9% | 3.2% | 2.1% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 2.2% |

| Roseland | 13.6% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 14.9% | 4.1% | 3.9% | 4.4% | 4.3% | 5.4% |

| South Chicago | 15.7% | 7.3% | 0.0% | 23.0% | 7.4% | 8.2% | 9.3% | 9.0% | 9.6% |

| South Deering | 28.6% | 45.2% | 0.0% | 73.8% | 1.9% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 3.5% | 4.0% |

| South Lawndale | 14.4% | 15.2% | 0.0% | 29.7% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 2.2% |

| South Shore | 4.7% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 8.7% | 6.1% | 7.5% | 6.0% | 5.1% | 5.5% |

| Uptown | 0.6% | 2.7% | 0.0% | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.3% | 1.8% | 1.5% |

| Washington Heights | 3.1% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 6.9% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.7% |

| Washington Park | 16.5% | 11.8% | 13.1% | 41.3% | 6.4% | 6.4% | 8.6% | 8.5% | 5.7% |

| West Elsdon | 0.0% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 1.4% |

| West Englewood | 37.7% | 22.0% | 0.0% | 59.7% | 5.7% | 5.8% | 6.9% | 7.8% | 8.3% |

| West Garfield Park | 21.4% | 6.7% | 2.1% | 30.3% | 4.6% | 4.1% | 4.0% | 4.3% | 4.6% |

| West Lawn | 3.4% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 6.4% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.1% |

| West Pullman | 15.5% | 14.5% | 0.0% | 30.0% | 4.7% | 5.1% | 5.6% | 5.9% | 6.6% |

| West Ridge | 0.6% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.5% |

| West Town | 5.1% | 10.0% | 1.5% | 16.6% | 2.3% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 2.8% | 2.2% |

| Woodlawn | 15.1% | 9.9% | 3.4% | 28.3% | 5.1% | 5.7% | 7.3% | 6.8% | 6.4% |

| Chicago | 5.5% | 4.7% | 4.2% | 14.4% | 2.5% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.8% | 2.7% |

Table A4.

2010 Socio-economic Status by Planning District (Chicago).

Table A4.

2010 Socio-economic Status by Planning District (Chicago).

| District | Race 1 | Education 2 | Unemploy. | Income 3 | Vacancy | Value 4 | Poverty | Ownership | Mobile Home | Crime 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albany Park | 3.8% | 34.9% | 9.0% | $46,865 | 8.7% | $328,123 | 19.6% | 38.3% | 0.2% | 2287 |

| Archer Heights | 1.1% | 36.4% | 14.2% | $44,171 | 12.1% | $259,372 | 12.4% | 64.6% | 0.7% | 4483 |

| Armour Square | 11.2% | 37.5% | 11.6% | $29,430 | 9.9% | $244,607 | 30.1% | 37.1% | 1.3% | 4590 |

| Ashburn | 50.8% | 18.3% | 8.8% | $62,205 | 4.2% | $203,099 | 10.8% | 88.7% | 0.1% | 3070 |

| Auburn Gresham | 98.6% | 19.5% | 24.2% | $35,003 | 14.4% | $162,760 | 27.6% | 50.4% | 0.0% | 6932 |

| Austin | 86.6% | 25.0% | 21.0% | $34,275 | 15.6% | $227,455 | 27.7% | 40.9% | 0.1% | 7070 |

| Avalon Park | 97% | 13.3% | 16.6% | $44,682 | 8.3% | $170,101 | 19.4% | 70.0% | 0.0% | 7439 |

| Avondale | 3.4% | 25.7% | 9.3% | $46,982 | 10.5% | $343,544 | 15.7% | 46.3% | 0.2% | 4071 |

| Belmont Cragin | 5.7% | 37.0% | 11.5% | $43,390 | 8.4% | $302,504 | 20.5% | 50.5% | 0.4% | 3899 |

| Beverly | 33.4% | 5.1% | 7.8% | $87,173 | 5.6% | $322,293 | 4.2% | 82.2% | 0.2% | 2468 |

| Bridgeport | 1.4% | 26.1% | 11.7% | $43,054 | 14.7% | $293,381 | 18.4% | 49.6% | 0.3% | 2940 |

| Brighton Park | 1.0% | 48.2% | 11.2% | $39,726 | 13.4% | $222,120 | 23.8% | 47.1% | 0.3% | 2935 |

| Burnside | 97.8% | 18.6% | 23.4% | $31,391 | 8.2% | $141,400 | 31.5% | 55.9% | 0.7% | 4983 |

| Calumet Heights | 96.1% | 11.2% | 17.2% | $55,840 | 7.2% | $194,811 | 14.6% | 75.9% | 0.4% | 6814 |

| Chatham | 97.7% | 13.7% | 19.0% | $35,059 | 15.2% | $179,384 | 24.5% | 37.1% | 0.1% | 9105 |

| Chicago Lawn | 55.8% | 31.6% | 11.9% | $39,273 | 17.7% | $178,183 | 24.7% | 47.3% | 0.2% | 7163 |

| Clearing | 1.5% | 18.5% | 9.6% | $54,622 | 6.7% | $241,552 | 6.4% | 75.2% | 0.1% | 1858 |

| Douglas | 76.3% | 16.9% | 16.7% | $40,042 | 19.1% | $177,867 | 27.5% | 20.7% | 0.0% | 5250 |

| Dunning | 1.2% | 18.0% | 8.6% | $61,757 | 4.8% | $298,414 | 7.7% | 78.6% | 0.3% | 1782 |

| East Garfield Park | 92.2% | 26.2% | 16.4% | $25,010 | 25.8% | $237,982 | 41.6% | 29.2% | 0.0% | 10,813 |

| East Side | 2.5% | 35.5% | 14.5% | $41,596 | 9.9% | $154,254 | 20.7% | 71.4% | 0.0% | 2348 |

| Edgewater | 14.1% | 9.1% | 8.9% | $47,803 | 9.3% | $311,524 | 16.4% | 39.4% | 0.1% | 2917 |

| Edison Park | 0.0% | 8.4% | 7.7% | $79,646 | 5.3% | $363,559 | 4.4% | 81.9% | 0.3% | 679 |

| Englewood | 98.7% | 29.4% | 21.3% | $21,138 | 26.6% | $135,587 | 45.1% | 31.8% | 0.5% | 11,289 |

| Forest Glen | 1.9% | 6.3% | 5.5% | $90,735 | 4.3% | $462,245 | 5.8% | 86.3% | 0.0% | 1505 |

| Fuller Park | 94.8% | 33.7% | 40.0% | $16,204 | 30.4% | $120,961 | 46.6% | 34.9% | 4.6% | 13,628 |

| Gage Park | 4.9% | 54.1% | 14.0% | $38,709 | 11.4% | $212,705 | 20.7% | 57.7% | 0.5% | 3709 |

| Garfield Ridge | 8.9% | 19.4% | 8.1% | $61,664 | 7.9% | $244,987 | 9.1% | 83.4% | 0.3% | 2353 |

| Grand Boulevard | 94.7% | 19.4% | 20.6% | $32,922 | 20.3% | $301,460 | 31.0% | 28.6% | 0.1% | 6842 |

| Greater Grand Crossing | 98.0% | 17.9% | 18.9% | $30,033 | 19.3% | $162,509 | 31.4% | 37.6% | 0.3% | 9059 |

| Hegewisch | 8.7% | 17.9% | 9.6% | $50,292 | 8.9% | $160,088 | 13.1% | 76.0% | 6.8% | 2594 |

| Hermosa | 1.9% | 41.9% | 12.9% | $42,676 | 12.2% | $316,207 | 19.9% | 46.3% | 0.6% | 3441 |

| Humboldt Park | 43.6% | 36.8% | 12.3% | $30,142 | 17.7% | $253,712 | 32.7% | 34.3% | 0.2% | 6458 |

| Hyde Park | 33.9% | 5.3% | 6.9% | $46,918 | 16.1% | $293,951 | 21.2% | 38.5% | 0.0% | 4676 |

| Irving Park | 3.8% | 34.9% | 9.0% | $46,865 | 8.7% | $328,123 | 19.6% | 38.3% | 0.2% | 2287 |

| Jefferson Park | 1.1% | 36.4% | 14.2% | $44,171 | 12.1% | $259,372 | 12.4% | 64.6% | 0.7% | 4483 |

| Kenwood | 11.2% | 37.5% | 11.6% | $29,430 | 9.9% | $244,607 | 30.1% | 37.1% | 1.3% | 4590 |

| Lake View | 50.8% | 18.3% | 8.8% | $62,205 | 4.2% | $203,099 | 10.8% | 88.7% | 0.1% | 3070 |

| Lincoln Park | 98.6% | 19.5% | 24.2% | $35,003 | 14.4% | $162,760 | 27.6% | 50.4% | 0.0% | 6932 |

| Lincoln Square | 4.9% | 12.5% | 6.8% | $58,210 | 10.2% | $375,125 | 11.5% | 41.2% | 0.0% | 2887 |

| Logan Square | 7.5% | 18.5% | 7.5% | $51,993 | 10.3% | $405,750 | 21.3% | 38.0% | 0.2% | 5247 |

| Loop | 10.5% | 3.4% | 4.2% | $81,068 | 22.4% | $387,971 | 12.3% | 50.1% | 0.2% | 22,568 |

| Lower West Side | 3.0% | 44.3% | 13.0% | $34,328 | 18.3% | $285,993 | 29.0% | 30.3% | 0.0% | 3518 |

| Mckinley Park | 1.3% | 31.8% | 11.9% | $42,206 | 11.5% | $256,521 | 15.5% | 58.5% | 0.0% | 3821 |

| Montclare | 4.7% | 28.4% | 10.8% | $48,463 | 8.0% | $302,504 | 11.6% | 62.4% | 0.6% | 2968 |

| Morgan Park | 65.5% | 10.9% | 14.9% | $53,805 | 12.8% | $201,701 | 14.1% | 75.4% | 0.2% | 4730 |

| Mount Greenwood | 5.4% | 4.5% | 6.9% | $82,743 | 4.8% | $253,442 | 2.5% | 88.2% | 0.0% | 1335 |

| Near North Side | 13.2% | 3.8% | 5.6% | $73,348 | 17.6% | $459,946 | 15.1% | 47.5% | 0.1% | 9173 |

| Near South Side | 35.5% | 7.1% | 5.7% | $76,205 | 13.6% | $388,066 | 11.8% | 53.8% | 0.1% | 5454 |

| Near West Side | 35.7% | 11.2% | 10.7% | $61,064 | 12.2% | $352,069 | 27.5% | 41.7% | 0.1% | 9788 |

| New City | 31.6% | 42.4% | 17.4% | $34,613 | 23.3% | $195,803 | 33.9% | 42.5% | 0.5% | 5908 |

| North Center | 3.0% | 5.4% | 4.5% | $84,015 | 11.3% | $545,334 | 7.2% | 52.9% | 0.0% | 3054 |

| North Lawndale | 92.5% | 30.4% | 18.5% | $26,165 | 26.6% | $209,021 | 42.4% | 26.4% | 0.4% | 9406 |

| North Park | 2.7% | 18.2% | 7.5% | $53,889 | 6.7% | $374,113 | 11.4% | 56.2% | 0.8% | 2854 |

| Norwood Park | 0.5% | 13.6% | 7.4% | $66,555 | 3.9% | $353,104 | 5.9% | 77.4% | 0.2% | 1376 |

| Oakland | 93.9% | 17.6% | 26.6% | $21,506 | 10.2% | $366,031 | 34.1% | 22.5% | 0.0% | 5776 |

| O’Hare | 1.1% | 11.4% | 4.9% | $50,462 | 9.1% | $225,346 | 9.7% | 49.3% | 0.1% | 4423 |

| Portage Park | 2.2% | 18.7% | 10.6% | $52,277 | 9.5% | $324,694 | 14.6% | 57.1% | 0.2% | 2575 |

| Pullman | 84.5% | 15.6% | 21.0% | $37,144 | 12.2% | $138,865 | 23.9% | 48.8% | 0.0% | 5684 |

| Riverdale | 97.7% | 24.6% | 26.4% | $13,795 | 39.9% | $97,709 | 60% | 15.7% | 0.0% | 6709 |

| Rogers Park | 30.4% | 18.4% | 7.3% | $41,374 | 15.8% | $254,681 | 26.1% | 31.0% | 0.1% | 3673 |

| Roseland | 98.0% | 17.4% | 17.8% | $40,847 | 12.9% | $148,513 | 23.4% | 59.6% | 0.2% | 7915 |

| South Chicago | 73.9% | 28.2% | 17.7% | $32,057 | 21.5% | $149,574 | 31.0% | 41.2% | 0.0% | 7720 |

| South Deering | 59.7% | 21.9% | 11.8% | $38,482 | 11.2% | $120,362 | 27.0% | 68.2% | 0.0% | 6280 |

| South Lawndale | 14.7% | 58.7% | 11.5% | $34,014 | 22.3% | $223,179 | 29.5% | 37.6% | 0.0% | 3117 |

| South Shore | 96.9% | 14.9% | 17.7% | $28,783 | 23.3% | $205,114 | 31.8% | 23.1% | 0.1% | 8863 |

| Uptown | 20.2% | 13.9% | 7.9% | $39,028 | 9.0% | $304,175 | 26.9% | 29.6% | 0.0% | 3673 |

| Washington Heights | 96.9% | 15.6% | 18.3% | $43,559 | 9.9% | $155,628 | 19.3% | 69.5% | 0.2% | 5813 |

| Washington Park | 98.1% | 28.3% | 23.2% | $24,001 | 30.7% | $176,320 | 41.6% | 21.6% | 0.5% | 12,035 |

| West Elsdon | 2.4% | 39.6% | 13.5% | $50,348 | 7.7% | $232,108 | 11.8% | 77.0% | 0.1% | 3122 |

| West Englewood | 96.3% | 30.3% | 34.7% | $27,412 | 24.3% | $117,392 | 41.4% | 46.6% | 0.1% | 10,148 |

| West Garfield Park | 97.7% | 26.2% | 25.2% | $24,676 | 26.5% | $229,365 | 39.9% | 27.5% | 0.1% | 9051 |

| West Lawn | 3.4% | 33.4% | 7.8% | $47,413 | 6.3% | $218,347 | 18.6% | 77.8% | 0.4% | 3710 |

| West Pullman | 94.8% | 22.6% | 17.0% | $38,399 | 16.3% | $134,032 | 25.8% | 64.5% | 0.0% | 6745 |

| West Ridge | 10.6% | 19.6% | 7.9% | $49,447 | 10.8% | $285,661 | 17.5% | 52.9% | 0.2% | 2638 |

| West Town | 9.8% | 13.4% | 6.0% | $63,470 | 12.2% | $422,685 | 17.6% | 40.4% | 0.2% | 7019 |

| Woodlawn | 89.0% | 17.9% | 17.3% | $28,475 | 27.6% | $228,166 | 28.8% | 27.5% | 0.0% | 8797 |

| Chicago | 34.3% | 20.8% | 11.2% | $48,648 | 13.7% | $292,604 | 21.0% | 48.1% | 0.3% | 5314 |

Race 1: African American %, Education 2: Less than high-school graduate %, Income 3: Median household income, Value 4: Median house value, Crime 5: Crime/100,000 pop.

References

- Park, Y.; LaFrombois, M.E.H. Planning for growth in depopulating cities: An analysis of population projections and population change in depopulating and populating US cities. Cities 2019, 90, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.; Lee, J.; Berke, P. Using the land transformation model to forecast vacant land. J. Land Use Sci. 2016, 11, 450–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Newman, G. Forecasting urban vacancy dynamics in a shrinking city: A land transformation model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Newman, G.; Park, Y. A Comparison of vacancy dynamics between growing and shrinking cities using the land transformation model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giffinger, R.; Haindlmaier, G.; Kramar, H. The role of rankings in growing city competition. Urban Res. Pract. 2010, 3, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, V. Growing city, shrinking hinterland: Land acquisition, transition and conflict in peri-urban Gurgaon, India. Environ. Urban. 2009, 2, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, R. Planning by design landscape architectural scenarios for a rapidly growing city. J. Landsc. Archit. 2008, 3, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B.; Pallagst, K.; Schwarz, T.; Popper, F.J. Planning shrinking cities. Prog. Plan. 2009, 72, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, J.; Logan, J. Greening the rust belt: A green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B.; Németh, J. The bounds of smart decline: A foundational theory for planning shrinking cities. Hous. Policy Debate 2011, 21, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim LaFrombois, M.E.; Park, Y.; Yurcaba, D. How US shrinking cities plan for change: Comparing population projections and planning strategies in depopulating US cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Newman, G.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, Y.; Lee, J. Neighborhood decline and mixed land uses: Mitigating housing abandonment in shrinking cities. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.; Bowman, A. Vacant land as opportunity and challenge. In Recycling the City: The Use and Reuse of Urban Land; Lincoln Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, M.; Chen, D.; Leonard, J.; Mueller Levy, L.; Little, C.; McCann, B.; Moravec, A.; Schilling, J.; Snyder, K. Vacant Properties: The True Cost to Communities; National Vacant Properties Campaign: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y. Population, Shrinking Cities, and Urban Regeneration in the U.S. Architecture 2018, 62, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, C.; Cocks, M. Housing vacancy and the shrinking city: Trends and policies in the UK and the city of Liverpool. Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, P. Preparing our housing for the transition to a post-baby boom world: Reflections on Japan’s 26 May 2015 Vacant Housing Law. Cityscape 2015, 17, 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, P.; Kaiser, E.J. Urban Land Use Planning; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk, D.R. Smart growth efforts around the nation. Pop. Gov. 2000, 66, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A.C.; Duncan, J.B. Growth Management Principles and Practices; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, P.R.; Conroy, M.M. Are we planning for sustainable development? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.; Beatley, T.; Berke, P.; Brower, D.; Kaiser, E.J. Natural Hazard Mitigation: Recasting Disaster Policy and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, S.D.; Highfield, W.; Carrasco, V. Measuring the collective planning capabilities of local jurisdictions to manage ecological systems in southern Florida. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tang, Z. Planning for drought-resilient communities: An evaluation of local comprehensive plans in the fastest growing counties in the US. Cities 2013, 32, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z. Evaluating local coastal zone land use planning capacities in California. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2008, 51, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurian, L.; Crawford, J.; Day, M.; Kouwenhoven, P.; Mason, G.; Ericksen, N.; Beattie, L. Evaluating the outcomes of plans: Theory, practice, and methodology. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2010, 37, 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurian, L.; Day, M.; Berke, P.; Ericksen, N.; Backhurst, M.; Crawford, J.; Dixon, J. Evaluating plan implementation: A conformance-based methodology. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Newman, G.; Lee, J.; Combs, T.; Kolosna, C.; Salvesen, D. Evaluation of networks of plans and vulnerability to hazards and climate change: A resilience scorecard. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Spurlock, D.; Hess, G.; Band, L. Local comprehensive plan quality and regional ecosystem protection: The case of the Jordan Lake watershed, North Carolina, USA. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.D. Attempting City–County consolidation in the Heartland: A personal account. Plan. Environ. Law 2010, 62, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.D.; Bowman, A.O.M.; Jung Lee, R.; Kim, B. A current inventory of vacant urban land in America. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R. Enhancing plan quality: Evaluating the role of state planning mandates for natural hazard mitigation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1996, 39, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.D. Are we learning to make better plans? A longitudinal analysis of plan quality associated with natural hazards. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2003, 23, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Have state comprehensive planning mandates reduced insured losses from natural disasters? Nat. Hazards Rev. 2005, 6, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Lindell, M.K.; Prater, C.S.; Brody, S.D. Measuring tsunami planning capacity on US Pacific coast. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2008, 9, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, C. How plan mandates work: Affordable housing in Illinois. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 73, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Tran, T. An evaluation of local comprehensive plans toward sustainable green infrastructure in US. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, T.J.; Jones, H.R. The Urban General Plan; Chandler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Cowley, J.S.; Gough, M.Z. Evaluating new urbanist plans in post-Katrina Mississippi. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R. Does sustainable development offer a new direction for planning? Challenges for the twenty-first century. J. Plan. Lit. 2002, 17, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E.; Knaap, G. Legalizing smart growth: An empirical study of land use regulation in Illinois. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2003, 22, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.D.; Carrasco, V.; Highfield, W.E. Measuring the adoption of local sprawl: Reduction planning policies in Florida. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 25, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, E.J.; Godschalk, D.R.; Chapin, F.S. Urban Land Use Planning; University of Illinois Press Urbana: Champaign, IL, USA, 1995; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K.R. Commentary. From the new urban politics to the ‘new’metropolitan politics. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 2661–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R.; Quiring, S.M.; Olivera, F.; Horney, J.A. Addressing Challenges to Building Resilience Through Interdisciplinary Research and Engagement. Risk Anal. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, W.; Stevens, M. Plan quality evaluation 1994–2012: Growth and contributions, limitations, and new directions. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Fort Worth. CompreComprehensive Plan; City of Fort Worth: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).