Abstract

Societies comprise multiple cultures, meaning that different cultural perceptions exist and that intercultural sensitivity is seen as an indicator of successful intercultural relations. The aim of this research is to establish the intercultural sensitivity levels of teachers in two multicultural cities. The sample consists of 190 teachers in primary education in the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and 174 primary teachers of Malaga and Granada, which makes a total sample of 364 teachers. The scale used in this research is an abridged version of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale: relational engagement, regard for cultural diversity, relational certainty, relational satisfaction, and relational carefulness. The scale has been validated on many occasions in the abridged and unabridged versions. The results show that teachers in Melilla and Ceuta show high levels of cultural sensitivity. There are significant differences depending on the variables analysed and depending on the context. Interaction enjoyment and interaction attentiveness have the highest levels for teachers in this research.

1. Introduction

A simple definition of culture is the way of life of a society. However, culture is a concept with many intricacies, such as belief systems, knowledge, art, the rules people live by, habits, and abilities derived from communities [1]. Lifestyle is influenced by cultural belief systems, behavioural patterns, values, and attitudes, although classical definitions understand culture as “an acquired and transmitted pattern of shared meaning, feeling, and behaviour that constitutes a distinctive human group” [2]. In most investigations, culture is defined as “those customary beliefs and values that ethnic, religious, and social groups transmit fairly unchanged from generation to generation” [3].

Societies comprising diverse cultures involve multiple cultural perceptions that merge and diverge because of cultural differences, and these are influenced by factors such as race, age, education, gender, ethnic attributes, and history [4]. In trying to talk about the same concept, some scholars use intercultural sensitivity in place of intercultural competence and vice versa. Nevertheless, the prerequisite skill for intercultural competence is intercultural sensitivity [5]. This is another way of saying that the epitome of intercultural knowledge and sensitivity, behaviourally speaking, is intercultural competence [6].

Intercultural sensitivity can be defined as a forerunner in attitude to successful intercultural relations and a predictor of cultural adequacy [7]. Intercultural sensitivity can be defined as the quality that affects intercultural communications where the people are willing to grasp, accept, and appreciate cultural differences [8,9,10] or to try to define cultural sensitivity as being able to accommodate worldviews that are focused on ethnicity and deal with differences in culture [11,12].

A recent study analysed two leading frameworks in the literature, Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) and Cultural Intelligence (CI). Using a sample of undergraduate students, the results show that personality traits work as antecedents for both frameworks and that when predicting behavioural adaptation, the fine-grained competencies outperform the broad operationalization of general competence [13].

In Spain, intercultural sensitivity and life satisfaction in native and immigrant students were analysed [14]. The results show that social self-concept is the main predictor of intercultural sensitivity in immigrant students, whereas emotional empathy, teachers’ perception of help, and social self-concept are the main predictors for native students. Family and emotional self-concept are the main predictors of satisfaction with life in immigrant students, and family and academic, social, and physical self-concept are that for native students.

An important piece of research in the United States concluded that religious affiliation and the number of times travelled outside the United States were significant predictors of intercultural sensitivity [15]. As a microcosm of society, a plurality of cultures can be found in classrooms. This must be attended to, and for this, teacher training is essential. Smith and Jones’s work presents different attitudes of the educational community on intercultural education and offers guidelines on the ideal teacher training, proposing a tool to collect information to measure the sensitivity of the teaching staff. They also raise the possibility of permanent teacher training, with strong intercultural competence [16].

Other researchers [17] have also worked on the intercultural training of secondary-education teachers, giving orientations to put into practice and emphasizing the need to work on the emotional, attitudinal, and ethical dimensions of teachers to be able to ensure the necessary sensitivity and commitment to cultural diversity. There is no doubt that training and cultural experiences have a positive effect on young people, increasing their ability to adapt [18]. This is where teachers play a key role as educators of competent adults in a diverse society [19].

Various pedagogical methodologies have been studied extensively to promote the inclusion of migrant and refugee children in the school system of their host country [20]. Nevertheless, to a lesser extent, the multicultural skills that teachers possess have been analyzed, especially in purely multicultural contexts. This is still one of the key factors that every teacher must possess [21].

For this research, we decided to use the definition of intercultural sensitivity proposed by Chen and Starosta [22]. The authors emphasized the differences between the idea of intercultural adequacy and potency, and this counters confusion in understanding the concept of intercultural sensitivity and gives a more comprehensive theoretical model to gauge this ideology [23,24].

In line with the advancement of establishing the concept of intercultural development, efforts have been continuously made to create self-report tools to gauge a concept like intercultural sensitivity inventory [25] and intercultural development inventory [5]. These are just the well-known ones. Although these scales measure similar constructs to each other, they have a large number of items. Current teaching staff are subject to large administrative tasks [26,27]. The use of a simpler scale to fulfil the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) is justified due to its large potential for collecting information. Nonetheless, it was only the ISS that suited our construct by pointing out five constituents that explain the intercultural sensitivity of an individual (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A visual representation of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) construct.

The study of teachers’ attitudes towards intercultural phenomena is not new, but there are certain deficiencies in the available studies [28,29]. The main problem with these investigations is that they focus on measuring communication skills or abilities [30]. Researchers analyse how participants are able to communicate with and relate to different people. The contribution of this research is justified from two important perspectives. On the one hand, the study was directed at intercultural sensitivity as a measurable phenomenon; on the other hand, the study developed two multicultural contexts in which cultures and values coexist.

The aim of this study is to analyze the intercultural sensitivity of primary-school teachers in Ceuta and Melilla, two autonomous cities on the north coast of North Africa, where different cultures coexist due to the geographical situation. Moreover, these autonomous cities are compared with two other cities of Spain, Malaga and Granada, where a natural cultural coexistence is lower.

High values of intercultural sensitivity are important when we travel and are exposed to other cultures. However, the values obtained in daily life are much more important and even more so when the context is multicultural and subject to change over short periods. Teachers have the responsibility to provide students with skills and to help them to develop empathy towards others and to respect their differences [31]. In order to transmit these skills and values to our students, we must first establish whether teachers possess them. It is a basic factor that allows us to develop a correct “cultural pedagogy” [32].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Two hundred and thirty-six teachers of primary and secondary education in the multicultural cities of Ceuta and Melilla participated in the study. They were 27–61 years old with a mean age of 35, and 57.89% were male while 42.10% were female. A sample of 81 teachers from Malaga and 93 from Granada was also collected in order to compare different contexts with different cultural relationships. The study was carried out during the first trimester of the school year (2018–2019). It is the first time that a study of these characteristics has been carried out in border and multicultural cities, so the results cannot be compared with those of previous studies.

In relation to cultural origin, three major groups stand out: European, Berber (cultural group of Riffian origin, Islamic religion and Tamazight mother tongue), and others (teachers whose mother/father are from Europe and mother/father are Berber, as well as Jews and Romani Gypsies). The variables used during the investigation are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the participants.

Nine teachers were eliminated from the sample, as they did not finish all the responses, thus making a final sample size of 190 for the multicultural context and 174 for the non-multicultural context. Participants completed the survey under the supervision of the researchers.

2.2. Instruments

An original ISS was created and validated in 2000 [22]. The original construct was validated and found to have the same dimensions as those presented by the original authors in other research papers [33,34]. The ISS originally had 24 items and 5 subscales with a Likert scale of 5 points. Included in the subscale is relational engagement, regard for cultural diversity, relational certainty, relational satisfaction, and relational carefulness.

For this research we used a more recent modified and validated version of the ISS [35]; this version was reduced to 15 items without losing its construct validity. According to the author, scores expected from the scale are between 15 and 75 (Appendix A). Higher scores indicated a higher level of intercultural sensitivity. The alpha value of the scale was better than the original scale. Different sociodemographic variables were collected in order to make comparisons between the different groups.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive, inferential, and multivariate statistics with SPSS 23 and AMOS 23 software. The samples used for comparison do not meet the classic requirements of parametric tests—normality (data have a normal distribution), homogeneity of variances (groups have the same variance), and independence (whether there is independence between two variables or attributes) [36,37].

Nonparametric statistics are used with the aim of providing data robustness [38]. In addition, in cases where the differences are significant, the effect sizes are calculated through Cohen’s d. This allows us to know the strength of the differences and not just to describe them in terms of magnitude [39].

Two kinds of nonparametric tests are carried out. The Mann–Whitney U test allows us to compare two independent groups and does not need a specific distribution [40]. Moreover, it is considered as a nonparametric version of the Student’s t-test. To compare more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis H test is used. It is an extended version of the Mann–Whitney U test [40]. Moreover, it is considered a nonparametric version of analysis of variance (ANOVA). To know how and between which groups the differences shown by the H test are found, it is necessary to study the comparisons individually through the Mann–Whitney U test for each possible pair [41]. The latest versions of SPSS simplify this process, showing visually the differences and values obtained by different groups.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Analysis

Different analyses were carried out to determine the validity of the model—in this case, Cronbach’s alpha (α), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Extracted Variance (AVE). The results obtained show reliability indices considered acceptable, obtaining for the total of the scale an α value of 0.92. Likewise, there are no problems of convergent validity: AVE > 0.5. The results of the reliability analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity indices.

3.2. Descriptive Analyses

As shown in Table 3, the values obtained were higher than the average values of each dimension (7.5) and the total scale (37.15). The highest values were obtained for interaction enjoyment (12.12 ± 3.24) and interaction attentiveness (13.31 ± 2.34). On the other hand, respect of cultural differences had the lowest value (9.13 ± 3.27).

Table 3.

Descriptive analysis of each dimension.

3.3. Inferential Analyses

The first inferential analyses were carried out on the populations of Ceuta and Melilla in line with the main objective of the research. In analysing the results in terms of gender (Table 4), only interaction enjoyment showed a significant difference (Z = –2421; p = 0.047). Although these differences were significant, the effect size (d = 0.035) indicates that the strengths of these are not great. In this case, women obtain a higher mean rank (MR = 49.21) value than men (MR = 41.30).

Table 4.

Mann–Whitney U test for different dimensions according to gender.

On the other hand, depending on the age, the results showed (Table 5) significant differences in three dimensions: interaction engagement (Z = −1.323; p = 0.002; d = 0.019), respect of cultural differences (Z = −2.113; p = 0.000; d = 0.031), and interaction enjoyment (Z = –3.258; p = 0.032; d = 0.048). The effect sizes were low for the first two and intermediate for the last one. Participants under 30 showed the best results (MR = 33.86; MR = 31.02; and MR = 33.02).

Table 5.

Mann–Whitney U test for different dimensions according to age.

Differences in the values obtained were checked according to the religions of the teachers involved in the experience (Christian and Muslim). The data revealed (Table 6) significant differences in interaction engagement (Z = −2.453; p = 0.012; d = 0.36) and interaction enjoyment (Z = −1.557; p = 0.022; d = 0.22). The effect sizes were low for the first two and intermediate for the last one. Participants identified that Muslim values were associated with the best results (MR = 29.16; MR = 59.80).

Table 6.

Mann–Whitney U test for different dimensions according to religion.

Participants were asked to identify with an ethno-cultural origin (Table 7), mostly with the European group or with the Berber group. Both groups coincide practically with the Christian and Muslim religious groups, respectively.

Table 7.

Mann–Whitney U test for different dimensions according to culture.

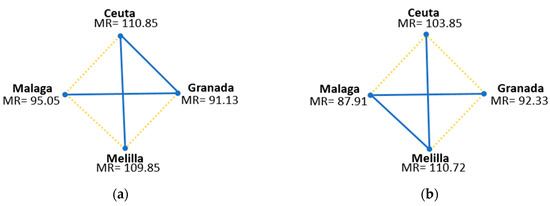

Finally, we compared the results with other contexts in Spain. To check whether the multicultural context influenced the scores obtained, it was necessary to make a comparison between different cities. In this case, a nonparametric test, Kruskal-Wallis H test, was used to analyse the differences between Ceuta and Melilla (Spanish border cities with a multicultural context) and Granada and Malaga, two Spanish cities without a significant coexistence of cultures or migratory pressure. A Kruskal-Wallis H test showed (Table 8) that there was a statistically significant difference with respect to the cultural differences between the different cities in different contexts, χ2(2) = 31.236, p = 0.003, and interaction attentiveness χ2(2) = 12.250, p = 0.005.

Table 8.

Kruskal–Wallis H test according to different cities (and contexts).

To simplify the interpretation of the results, we used a visual analysis of the mean ranks provided by the analysis software (Figure 2), where the yellow broken lines represent the existence of a significant relationship. It is observed that the significant differences found in the previous analysis focused on very different cities. Among the cities considered multicultural (Ceuta and Melilla), no significant differences were found in any of the two factors. The same was shown for the two cities located in a completely different context (Malaga and Granada). The differences for respect of cultural differences were between Melilla (MR = 109.85) and Granada (MR = 91.13), and Ceuta (MR = 110.85) and Malaga (MR = 95.05). For the interaction attentiveness dimension, the differences were found in Ceuta (MR = 103.85) and Malaga (MR = 87.91), Ceuta (MR = 103.85) and Granada (MR = 92.33), and Melilla (MR = 110.72) and Granada (MR = 92.33). These results indicate that the context is a variable that influences these dimensions significantly.

Figure 2.

Visual analyses of the statistically significant differences. (a) A mean rank analysis of respect of cultural differences dimension. (b) A mean rank analysis of interaction attentiveness dimension.

4. Discussion

Intercultural sensitivity is not an instinctive or universal aspect of human behavior. Nowadays, the development of intercultural sensitivity represents a great challenge for educational systems where different cultures coexist [43].

The results obtained show high values of cultural sensitivity among teachers in both cities. Similar results have been obtained in other investigations [29,44]. Within the educational system, teachers obtaining these results are a positive phenomenon. They are responsible for applying and developing the future competences and cultural responsibility of their students [20,45].

Although some significant differences are found depending on the variables analysed, the strength of these differences are low and these cannot be considered as relevant differences. Teachers appear to be open to knowing and relating to people of other cultures—a greater predisposition than has been observed in people of different ages who have experienced a migratory process [46,47].

It has been found in this research that the highest values appear in interaction enjoyment and interaction attentiveness, which means that teachers feel encouraged about interactions with other cultures and think that this interaction is useful. Although, as has been proven, just having an intercultural experience is not a guarantee of improvement in intercultural competence [48].

Although it has been observed in this research that, between the considered multicultural cities (Ceuta and Melilla because of the geographical situation) no significant differences were found in two factors, differences in respect of cultural differences exist between Melilla and Granada, and Ceuta and Malaga. Further, regarding interaction attentiveness, differences are found between Ceuta and Malaga and moreover between Ceuta and Granada, and Melilla and Granada. Thus, the results seem to indicate that context can influence those dimensions [49,50].

The differences found in these cities are mainly due to two phenomena. First, the natural context in which most of these teachers have grown up, where they have been exposed to this type of relationship since childhood, and during their training [51,52]. Second, the specific training they have done. This training has been proven to have positive effects on intercultural relations [53,54].

5. Conclusions

It has been shown in this work that intercultural sensitivity is not an instinctive or universal aspect of human behaviour and that it is a challenge for educational systems to accommodate people from different cultures. It was found that teachers in Melilla and Ceuta show high levels of intercultural sensitivity, which can be very helpful for teaching sensitivity to their students in a natural way. This fact shows that context and training can be two important points in the development of high levels of intercultural sensitivity.

Teachers are open to meeting people from other cultures and getting to know them too. This is considered highly positive; as such, knowledge and interaction can bring about new relations among cultures. Interaction enjoyment and interaction attentiveness happened to have the highest levels among the teachers of this research, and these dimensions can be very useful in fostering interaction among cultures. However, these dimensions themselves do not guarantee intercultural competence, and it is recommended here to work on fostering and learning this competence, working on the rest of the dimensions to create an intercultural competence with a combination of all of them.

6. Limitations and Future Research

The present study has limitations and elicits suggestions for future studies. The first limitation focuses on the number of variables analysed, although they could be considered sufficient for a preliminary study. For future research, it is advisable to explore other variables. Future research could involve more complex designs or longitudinal studies with different samples to study the change of results over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.P.-G.; data curation, A.S.-R.; investigation, A.S.-R.; methodology, A.S.-R. and M.E.P.-G.; supervision, M.E.P.-G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Version of ISS used in this research.

Table A1.

Version of ISS used in this research.

| Dimension | Nº | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction engagement | 1 | I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures. |

| 2 | I often give positive responses to my culturally different counterpart during our interacting. | |

| 3 | I avoid those situations where I will have to deal with culturally distinct persons. | |

| Respect of cultural differences | 4 | I do not like to be with people from different cultures. |

| 5 | I would not accept the opinions of people from different cultures. | |

| 6 | I think people from other cultures are narrow-minded. | |

| Interaction confidence | 7 | I am pretty sure of myself in interacting with people from different cultures. |

| 8 | I feel confident when interacting with people from different cultures. | |

| 9 | I can be as sociable as I want to be when interacting with people from different cultures. | |

| Interaction enjoyment | 10 | I often feel useless when interacting with people from different cultures. |

| 11 | I get upset easily when interacting with people from different cultures. | |

| 12 | I often get discouraged when I am with people from different cultures. | |

| Interaction attentiveness | 13 | I am very observant when interacting with people from different cultures. |

| 14 | I am sensitive to my culturally distinct counterpart’s subtle meanings during our interaction. | |

| 15 | I try to obtain as much information as I can when interacting with people from different cultures. |

References

- Göl, İ.; Erkin, Ö. Association between cultural intelligence and cultural sensitivity in nursing students: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Collegian 2018, in press. S1322769618303238. [Google Scholar]

- Ayman, R.; Korabik, K. Leadership: Why gender and culture matter. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, P.W.; Kim, M.M.; Clinton-Sherrod, A.M.; Yaros, A.; Richmond, A.N.; Jackson, M.; Corbie-Smith, G. What is the role of culture, diversity, and community engagement in transdisciplinary translational science? Transl. Behav. Med. 2016, 6, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, M.R.; Bennett, M.J.; Wiseman, R. Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The Intercultural Development Inventory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2003, 27, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.Y.; Rangsipaht, S.; Thaipakdee, S. Measuring intercultural sensitivity: A comparative study of ethnic Chinese and Thai Nationals. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2015, 34, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler, L.; Sussman, N.M.; Kachur, E. Assessing changes in intercultural sensitivity among physician trainees using the intercultural development inventory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2003, 27, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-Y. A Comparative Perspective of Intercultural Sensitivity Between College Students and Multinational Employees in China. Multicult. Perspect. 2006, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, I.; Kuusisto, E.; Kuusisto, A. Developing teachers’ intercultural sensitivity: Case study on a pilot course in Finnish teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 59, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, E.; Kuusisto, A.; Rissanen, I.; Holm, K.; Tirri, K. Finnish teachers’ and students’ intercultural sensitivity. J. Relig. Educ. 2015, 63, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M. Toward Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity. In Education for the Intercultural Experience; Paige, R.M., Ed.; Intercultural Press: Yarmouth, ME, USA, 1993; pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Helal, F. Discourse and Intercultural Academic Rhetoric. Open J. Mod. Linguist. 2013, 03, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, O.E. Multicultural competence: an empirical comparison of intercultural sensitivity and cultural intelligence. Eur. J Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micó-Cebrián, P.; Cava, M.-J.; Buelga, S. Sensibilidad intercultural y satisfacción con la vida en alumnado autóctono e inmigrante. Educar 2019, 55, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.R.; Mwavita, M. Evaluating the international dimension in an undergraduate curriculum by assessing students’ intercultural sensitivity. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 59, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, O.; Berríos, L.; Buxarrais, M.R. La sensibilidad del profesorado hacia el modelo de educación intercultural: Necesidades, situación actual y propuesta de un instrumento de medida. Estud. Pedagógicos Valdivia 2013, 39, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordán, J.A. Formación intercultural del profesorado de secundaria. ESE Estud. Sobre Educ. 2007, 12, 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Working in the classroom with migrant and refugee students: the practices and needs of Italian primary and middle school teachers. Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 2019, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, U.P.; Roopnarine, J.L. (Eds.) Childhood and Adolescence: Cross-Cultural Perspectives and Applications, 2nd ed.; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4408-3223-9. [Google Scholar]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Social Sustainability and Professional Development: Assessing a Training Course on Intercultural Education for In-Service Teachers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmon, M.A. Six Key Factors for Changing Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes/Beliefs about Diversity. Educ. Stud. 2005, 38, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, L.C. The development and validation of the intercultural communication sensitivity scale. Hum. Commun. 2000, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwari, A.Q.; Abdul Wahab, M.N. Study of the relationship between intercultural sensitivity and intercultural communication competence among international postgraduate students: A case study at University Malaysia Pahang. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamam, E.; Krauss, S.E. Ethnic-related diversity engagement differences in intercultural sensitivity among Malaysian undergraduate students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Brislin, R. The measurement of intercultural sensitivity using the concepts of individualism and collectivism. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1992, 16, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Senécal, C.; Guay, F.; Marsh, H.; Dowson, M. The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST). J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers-Rubio, R.; Mas-Ruiz, F.J.; Casado-Díaz, A.B. University Efficiency: Complementariness versus Trade-off between Teaching, Research and Administrative Activities: Analysing University Efficiency: Evidence from Spain. High. Educ. Q. 2010, 64, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hus, V.; Hegediš, P.J. Future Primary School Teachers Attitudes toward Intercultural and Bilingual Education in Primary Schools. Creat. Educ. 2018, 09, 2939–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, C.Y.M.; Grossman, D.L. The intercultural sensitivity of student teachers in three cities. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2009, 39, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P. Problematising Intercultural Communication Competence in the Pluricultural Classroom: Chinese Students in a New Zealand University. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2006, 6, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y.; Roddin, R.; Awang, H. What Students Need, and What Teacher Did: The Impact of Teacher’s Teaching Approaches to the Development of Students’ Generic Competences. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 204, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.A. Empathy, Teacher Dispositions, and Preparation for Culturally Responsive Pedagogy. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulduk, S.; Tosun, A.; Ardıç, E. Measurement Properties of Turkish Intercultural Sensitivity Scale Among Nursing Students. Turk. Klin. J Med Ethics 2011, 19, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, A.J.; Kamhawi, R.; Fishwick, P.; Henderson, J. New media environments’ comparative effects upon intercultural sensitivity: A five-dimensional analysis. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2013, 37, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, M. Validation of the short form of the intercultural sensitivity scale (ISS-15). Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2016, 55, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J. Statistical power of non-parametric tests: a quick guide for designing sampling strategies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacre, M.; Lakens, D.; Leys, C. Why Psychologists Should by Default Use Welch’s t-test Instead of Student’s t-test. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 30, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás Sábado, J. Fundamentos de Bioestadística y Análisis de Datos para Enfermería; Universidad Autónoma de Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Servei de Publicacions: Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-490-2581-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 4–91. ISBN 978-0-470-47921-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertagová, E.; Ostertag, O.; Kováč, J. Methodology and Application of the Kruskal-Wallis Test. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 611, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 10–32. ISBN 978-0-12-179060-8. [Google Scholar]

- Westrick, J.M.; Yuen, C.Y.M. The Intercultural Sensitivity of Secondary Teachers in Hong Kong: A Comparative Study with Implications for Professional Development. Intercult. Educ. 2007, 18, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtseven, N.; Sertel, A. Intercultural Sensitivity in Today’s Global Classes: Teacher Candidates’ Perceptions. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2015, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tarman, I.; Tarman, B. Developing effective multicultural practices: A case study of exploring a teacher’s understanding and practices. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2011, 4, 578–598. [Google Scholar]

- González López, A.; Ramírez López, M.P. La sensibilidad intercultural en relación con las actitudes de aculturación y prejuicio en inmigrantes y sociedad de acogida. Un estudio de caso. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2016, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Dasli, M. Towards an Understanding of Integration amongst Hospitality and Tourism Students using Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2010, 9, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, Y.; Lundgren, K.; Pynes, P. Impact of short-term study abroad program: Inservice teachers’ development of intercultural competence and pedagogical beliefs. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnum, M.E.W.; Grossmann, I.; Kitayama, S.; Nisbett, R.E. The Origin of Cultural Differences in Cognition: The Social Orientation Hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamam, E. Examining Chen and Starosta’s Model of Intercultural Sensitivity in a Multiracial Collectivistic Country. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2010, 39, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, S. Cultures in Contact: Studies in Cross-Cultural Interaction; Elsevier Science: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4831-8964-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, O.; Rubin, D.L. Intergroup Contact Exercises as a Tool for Mitigating Undergraduates’ Attitudes Toward Nonnative English-Speaking Teaching Assistants. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 2012, 23, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Littrell, L.N.; Salas, E. A Review of Cross-Cultural Training: Best Practices, Guidelines, and Research Needs. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Kabongo, J.D. Cross-cultural training and expatriate adjustment: A study of western expatriates in Nigeria. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).