Abstract

Typically, residents play a role in developing strategies and innovations in tourism. However, few studies have sought to understand the role of Islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan. Previous studies focusing on socio-cultural impacts as perceived by local communities have applied various techniques to explain the relationships between selected variables. Circumstantially, the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique has gained little attention for measuring the religiosity factors affecting the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism. This investigation aims to address such limitations in this area of scientific knowledge by applying Smart PLS-SEM, developing an empirical approach, and implementing Smart-PLS software V-3.2.8. The proposed tourism model predicts the effects of the religiosity level on the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism development. In this study, we examine the relationships among religious commitments, religious practice, and religious belief and the socio-cultural effects of sustainable tourism. Our research identifies influential factors through an extensive literature review on communities’ religiosity and the socio-cultural impacts of developing sustainable tourism. We examine and analyze data based on 508 residents’ responses. The findings reveal an R² value of 0.841, suggesting three exogenous latent constructs, which collectively elucidate 84.10% of the variance in the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism. The findings reveal that religious respondents with a higher religiosity level have a positive attitude towards developing sustainable tourism. These findings are helpful to understand the dynamics of communities’ perceptions, behaviors, quality of life, cultural aspects, and religiosity factors affecting sustainable tourism in Pakistan. This study is novel in the context of Pakistani cultural and social norms, and this study’s implications may provide further direction for researching and developing sustainable tourism in the northern regions of Pakistan.

1. Introduction

In recent years, tourism has gained increasing popularity, and currently it is one of the most important industries in several developing countries [,,,]. Many scholars have investigated and published relevant literature on the subject of sustainable tourism developments and host residents’ behaviors and supportive attitudes in developing tourism in the modern era [,,]. Moreover, several authors have investigated this subject, and a considerable number of studies have examined, modeled, and measured the effect of sustainable tourism development on the host residents’ perceived impacts, perceptions, attitude, and behavior in supporting further sustainable tourism development [,,]. Butler (2006) described the indispensable role that residents and their perceptions play in understanding the development mechanism and process of sustainable tourism [,]. Residents mostly point to the influence of sustainable tourism on their individual and communal living conditions [,]. Though sustainable tourism development appears to be profitable, its environmental impact and the socio-cultural perceptions of local inhabitants may refocus judgments on other issues []. Butler and various scholars have evaluated the relationship between the various processes of sustainable tourism development. Residents’ reactions from different perspectives and these assessments emphasize adverse impacts, such as cultural corruption and capacity problems derived from cross-border movements [,,,]. Tourism development is considered to be a rural development mechanism concerning culture, communities’ attitude, and socioeconomic contributions, generating rural income and employment opportunities, contributing to residents’ services and amenities, and supporting the conservation of cultural resources [].

All over the world, local societies, villages, and rural economies, whether in developing countries or the First World, have faced significant challenges and changes []. Sustainable incomes empower community development and culture and support community development at the grassroots level rather than just focusing on policy. New approaches to community development began between 1950 and 1970; however, there was no actual transfer of powers or resources []. Nevertheless, Phillips and Pittman (2014) remained focused on the economic development of communities and supported communities in innovative and new ways [,]. Tourism helps communities to generate economic opportunities, and it encourages progress and growth in these areas. Concerns associated with local knowledge have increased recently, leading to empowerment, local community participation, and participatory learning, and various approaches and methods have become grassroots-oriented, improving the confidence and skills available to upgrade communities starting at the local level [,]. Since the 1990s, scholars have made a determined effort to understand the income opportunities of rural communities more precisely as they relate to aspirations for rural development; as such, development attracts tourism to these sites. Typically, tourism development influences rural communities, and it makes a positive impact on their livelihoods. Thus, for some researchers, social constructionism theories present culture by reflecting rustic studies as far removed from the core concern of change in the socioeconomic situation of these communities. By focusing on cultural values and developments in the local community, this study adopts a perspective of livelihood based on cultural knowledge, traditions, culture, and sustainable livelihoods of the rural communities as a pragmatic approach. The host communities want to make tourists happy to generate an advantageous image of the destination, which ultimately creates a positive reputation.

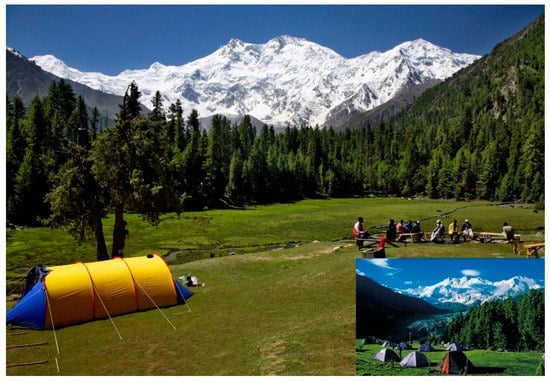

The hosts/local communities ultimately affect visitor satisfaction, which encourages tourists to revisit []. Therefore, measuring the community’s perception of the host society is very important for tourism sustainability in the northern regions of Pakistan. Local community attitudes towards sustainable tourism development vary in developed and underdeveloped countries. In some Islamic countries, the host residents of rural communities display a welcoming approach to domestic and international tourists, and their opinion is more favorable to Muslim tourists as they share similar cultural values. Understanding such perspectives supports sustainable tourism and helps to create positive impacts on local communities. Figure 1 below of the study area presents tourism sites.

Figure 1.

Study area showing Northern areas of Pakistan. K2 is the world’s second highest mountain.

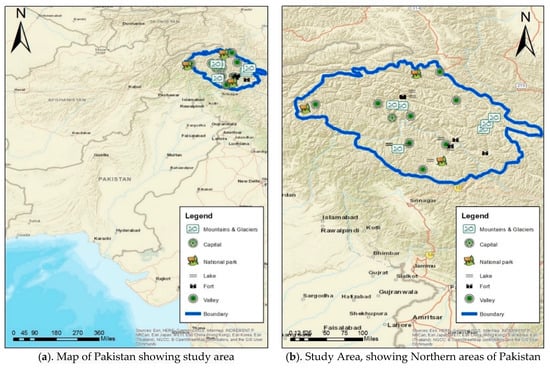

We have enriched the study area by incorporating the geographical identification of the study area Tourism locations by using ArcGIS software (Esri, Redland, CA, USA) to show sample study area points on the map, as shown in Figure 1 above [,].

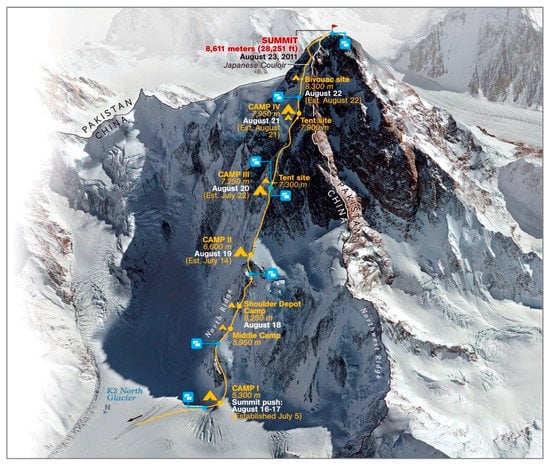

In the context of Pakistani rural areas, host communities’ residents have observed that tourists consume products and services, which creates income opportunities. Tourists in Islamic countries often practice similar religious traditions and share similar views of Islamic philosophy. Therefore, the response of local community residents and the intervention of their local government are different. Sustainable tourism is most likely to be achieved in an environment of natural beauty, where the community residents have a positive reputation, i.e., where both the natural environment and the social climate are perceived to be worthwhile. The natural environment includes animals, plants, and the inhabitants of these areas. The social climate includes social, cultural, and socioeconomic factors. However, it is notable that the human and the natural environments are connected or interlinked, and human activities influence the natural environment by affecting the sustainability of the environment [,]. Therefore, sustainable tourism may have a positive social impact as a human activity, as its effects are evident in the destination areas, and tourists often come into contact with the local environment, culture, and society []. This paradigm is reflected on an international and domestic level in the study area—a beautiful, little-explored valley in Pakistan—where sustainable tourism development policies and implementation need the attention of the government to consider such factors [,,], particularly in the context of the rural areas of northern Pakistan [,,]. The study area includes important mountain ranges that have received attention from domestic and international travelers, who often choose to revisit the destination. Table 1 presents an overview of the sites included in the study area. Figure 2 below shows the study area.

Table 1.

Mountain peaks in the northern areas of Pakistan (height in meters).

Figure 2.

The study area presents Northern areas of Pakistan. K2 is the world’s second highest mountain (Source: Wikipedia).

The study area commands a spectacular view of the Karakoram mountain range, including K2, which is the second highest peak in the world. The natural beauty of the region appeals to many residents and international tourists each year, bringing a considerable amount of foreign currency into the country. Traditional communities are active in the promotion of cultural tourism, which improves economic growth, helps communities to create income opportunities, and provides an increase in local businesses.

Similarly, cultural tourism helps to identify avenues of alternative tourism development that can help to maintain a genuinely enriching environment. Since the first Western tourist group visited this region at the end of the 19th century, more international tourists have begun to travel to the study area every year. The opening of the Karakorum (KKH) Expressway in 1978 promoted the development of new wave tourism. At present, the modern tourism industry in the northern region of Pakistan is now able to entertain four categories of tourists: (1) group tourists (using international travel services); (2) individual tourists (using temporary services); (3) high-altitude climbers and expeditions; and (4) domestic tourism services. Over the past two decades, tourism development has attracted visitors to the beautiful natural valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan, and local communities have supported and encouraged tourists to visit these natural sites and places. The focus of the Pakistani government has been to promote climbing and hiking in the highlands, encouraging foreign exchange trading. Domestic visitors traveling to these areas have increased tremendously in number, including noninstitutional groups and families, especially in the summer. Several Arab tourists are regular travelers to these natural places, enjoying the supportive attitude of the local communities: the cultural and social experiences are remarkable and relatively cheap compared with European trips.

In this study, we focused on the northern part of Pakistan, named Gilgit-Baltistan, and investigated contemporary perspectives on local attitudes [], culture, sustainable tourism development, and the religiosity effect as a conceptual framework for examining the rural tourism development process in the valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan []. Here, we propose a collaborative approach that emphasizes the role of social attitudes and the impact of religiosity, cultural, and other socioeconomic factors on developing sustainable tourism that benefits both tourists and local communities collectively []. We examined the residents’ religious practices and their effect on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism. The residents’ religious beliefs have a positive and significant relationship with the socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural and Social Impacts of Tourism

Previous studies investigating local communities’ support for sustainable tourism development typically relied on sociological and psychological perspectives and assumed that the communities’ residents are not homogeneous individuals, who may or may not be willing to support tourism development []. Moreover, various studies debated the relationships between community residents’ and the socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism []. Earlier studies documented the ongoing phenomena in the countryside, showing declining employment opportunities and local populations, as well as a deterioration of infrastructure and amenities [,,,,]. In this context, scholars recognized sustainable tourism as an advantageous mechanism contributing to local communities [,,]. Sustainable tourism creates opportunities for small, family-oriented businesses [,], which offer tourists cultural experiences and an enjoyable local environment that contributes to local community development [,,]. More precisely and concretely, developing sustainable tourism contributes to rural areas by providing pleasant socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental experiences; it also creates employment and income, adds to local community amenities, and aids in the conservation of cultural resources [,]. This paradigm might depend upon the coexistence of a governance approach, feasibility, a community attitude, cultural enrichment, and an enjoyable environment for tourists in the northern areas of Pakistan [,]. Thus, sustainable tourism development in countryside localities relies upon encouraging policies, governmental and non-governmental collaboration, and streamlining the development practices that could promote local communities’ attitudes, socioeconomic contribution, culture, and the effect of religiosity [,]. The socio-cultural impacts are affected by how local inhabitants perceive sustainable tourism [,]. Local culture also impacts tourism and attracts tourists, and innovations in sustainable tourism, tourists’ cross-cultural vision, virtual visitors, museum and heritage management in the recent digital age, policy on digital tourism and culture, governance and tourism marketing, social media, e-tourism, and emerging technologies are also crucial in developing tourism []. Gursoy (2017) noted that the socio-cultural and socioeconomic impacts of sustainable tourism on local communities are typically not easy to assess, and quantifying tourism development is slow and unglamorous. Swarbrooke (1999) argued that sustainable tourism development has attracted enormous attention recently in countries of the developed and developing world [,].

Tourists’ exposure to local communities’ indigenous cultures, normally disparaged as performances and events, and the tour packages offered should be commercially feasible, attractive, and comprehensible for sustainable tourism to flourish [,]. Prior research suggests that the social and cultural phenomena of sustainable tourism do not present a clear picture, and it is not easy to draw a line between cultural or social marvels or events; various theorists categorize sociocultural and socioeconomic impacts of sustainable tourism in broader context []. Thus, different perceptions of the impact of tourism from various types of inhabitants may provide insight into these natural sites and the degree to which sustainable tourism affects tourists’ destinations. As a result, it is unsurprising that research on local inhabitants’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development continues to be an exciting topic of substantial interest. Further, Hashimoto argued that the culture and mindset of host communities and their perception of sustainable tourism development and travelers vary unceasingly between positive and negative [,,,]. Specht (2014) wrote that the narrative on tourism demonstrates how various inhabitants might not only have different cultures and attitudes, but also that they might have ambivalent or dissimilar attitudes towards sustainable tourism [,]. Tourism development has several socio-cultural benefits and advantages, for instance, the host community’s cultural development, cultural exchange, an improved image for host communities, social change, social amenity improvements, and better public health, education, attitudes, and conservation [,]. Many prior studies inspecting the socio-cultural impact of tourism development have listed several probable positive effects of the tourism industry. Prior studies extensively observed the perception of socio-cultural impact on geographic or socio-demographic influences. However, as stated above, there are no prior studies in the literature that have investigated the effect of residents’ religiosity level on the perceived socio-cultural impacts of tourism development. Table 2 presents some previous studies as given below;

Table 2.

The sustainable management of natural resources.

The natural resources of the country are an essential aspect of development, as they provide raw materials for industry and have become a symbol of national pride. Managing sustainable natural resources refers to long-term land, water, environment, animal, and vegetation management. Figure 3 below of the study area presents tourist destinations.

2.2. The Dimension of Islamic Religiosity: Host Community Perception of the Socio-Cultural Impact of Sustainable Tourism

Tourism development affects communities in many urban destinations, as well as in coastal and rural areas. The socio-cultural implications in these destinations, however, are less well-documented in the literature concerning developing countries []. The development of world civilizations and human history is intertwined with religion, which is one of the main pillars of human societies worldwide []. Faith is a binding force in many human communities, and it describes a code of human ethics that is apparent in culture, societal setup, attitudes, and personal values []. These social values, beliefs, and religious norms determine institutional practices, as well as human behavior. In several Western societies and Asian countries, religion is not only a system of belief; it is also individuals’ recognized faith in all aspects of human life. Religion has a social impact on consumer products and services in various industries, including hospitality and travel. Sociologists view religion as an ideology that applies to humans and members of a community bonded in a harmonious relationship [,]. Religion is among the most critical social and cultural forces and has a significant impact on human behavior []. Religion affects the interaction of people, and it helps individuals of different mindsets to create a better understanding. Social distance theory claims that people with similar social, cultural, and religious values are more vulnerable than other individuals []. Social distance determines the distance or gap between different people, groups, and social systems in human society, and the notion of this distance rests on social class, race, ethnic group, gender, and sexuality. However, it is a fact that social range is higher among dissimilar people or groups, while people with different mindsets mix more efficiently in social gatherings as the degree of intimacy or understanding is more elevated in their personal and social relations. Several earlier studies support social exchange theory, and the literature has suggested that the exchange system helps in evaluating sustainable tourism impacts. However, rare studies have considered host residents’ cultural background.

Other studies focusing on residents’ attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions of the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism identified various relationships. Accordingly, the proposition of research focusing on Islamic religiosity by covering religious belief, practice, and commitment has shown a negative association with socio-cultural impacts. Typically, researchers have assessed religious beliefs by adopting a multidimensional approach. In the literature, Batson, Schoenrade, and Ventis (1993) applied a two-dimensional technique to calculate religious beliefs []. Chang and Downey (2011) also used a two-dimensional method to measure the effects of religiosity, considering individuals beliefs and practices []. One of the two dimensions includes internal and external religious practices, and the second is a visible expression of religious faith, for instance, the study of the Holy Quran, daily prayers, traditions, and rituals. Allport (1951) introduced a theological, ethical position named SCALA by narrating external and internal religious practices as the critical aspects of religious beliefs, and these two dimensions present different motives of religious believers []. Typically, individuals divide their religious structures via a two-dimensional approach to practicing religion: individually and collectively in groups [,]. Scholars have also considered a three-dimensional religious approach that is more appropriate for measuring religiosity among people [,,,,,]. These scholars have agreed that previous studies discussed only two dimensions of religiosity: one dimension is a religious belief and the other is an individual’s spiritual practice [,]. The third dimension of religiosity is different from those as mentioned earlier in the literature, and it denotes an inverse relationship. The third dimension is ‘community’, ‘organization’, ‘experience’, ‘spirituality’, and ‘experimental’ [,,]. In 2009, Tailoring and Begloomed attempted to assess the breadth of the Islamic religion, considering vital Islamic elements such as Islamic texts, the Holy Quran, and the Hadith (the actions and speeches of the Holy Prophet PBUH). They declared that there are four primary dimensions of Islam out of 60, namely religious beliefs, spiritual friendships, religious ceremonies (be kind to others), and spiritual enrichment (womb-to-tomb learning). The most common assessments of religion are the two-dimensional and three-dimensional methods, and there are many differences in the factors defining the dimensions as the elements used in the analyses are also different. Allport (1951) measured an individual’s religiousness based on their motivation [,]. Scholars including Abdullah (2010) have claimed that the Quran and Hadith of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) are crucial elements in measuring Islamic beliefs (faith) and individuals’ Islamic practice [,,].

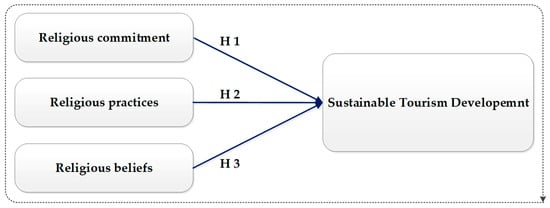

Figure 4 here outlines the conceptual framework of the tourism model used in this research, which presents the effects of Islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism. Since the 1990s, scholars have focused on this area and have made a determined effort to understand whether the financial advantages of rural communities specifically were in line with aspirations for rural development as they attracted sustainable tourism development to such natural places. Thus, tourism development influenced rural communities’ attitudes, which had a positive impact on their livelihoods. Therefore, their approach to a sustainable livelihood has revealed individual skills and the actions required to generate livelihoods. Such livelihoods are sustainable if residents can cope with and recuperate from stresses [], shocks, and pressure and still maintain or enhance their assets and capabilities, balancing a sustainable livelihood (SL) environment, tradition, and the socio-culture impacts of tourism.

Figure 4.

It demonstrates the conceptual framework of the proposed study.

2.3. Conceptual Framework

This study designed a conceptual model and applied Partial Least Square Structural Partial Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), structural equation modeling, to evaluate the effect of residents’ religiosity level on the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism. The PLS-SEM approach is the conventional method for conducting causal predictive analysis to examine both formative and reflective models, and it calculates the relationship among selected variables []; it is a nonparametric technique and it does not require any supposition regarding data distribution. The PLS-SEM is the commonly used technique for multivariate analysis to measure variance-based structural equation models in the fields of social sciences []. In this study, the model contains three groups of exogenous latent constructs, namely factors of religious commitment, religious belief, and religious practice, and one endogenous latent variable, called socio-cultural impacts, with eight observed variables. Figure 4 below displays the conceptual model of this study, and it shows the relationships among the selected variables (endogenous latent constructs and exogenous latent constructs).

2.4. Hypotheses of the Study

Hypothesis 1.

A community’s religious commitment positively affects sustainable tourism development.

Hypothesis 2.

A community’s religious practices positively affect sustainable tourism development.

Hypothesis 3.

A community’s religious beliefs form a positively significant relationship with sustainable tourism development.

3. Methods

Researchers typically use the smart PLS-SEM technique for developing a theory in exploratory research []. The smart PLS-SEM critical applications include confirmatory factor analysis, path analysis, regression models, factor analysis, covariance structure models, and correlation structure models []. Additionally, structural equation modeling (SEM) permits linear relationships analysis between manifest variables and latent constructs. Partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) refers to a multivariate statistical technique for evaluating the measurement model simultaneously, such as the relationship between the study constructs and its conforming indicators with a structural model to indicate relationships between the constructs []. It also can produce available parameter estimates to assess the associations between unobserved variables. Typically, the SEM method allows many relationships to be calculated and tested at once in the single proposed model with many links instead of investigating each relationship individually. This study has analyzed the hypothesized structural model of Figure 4 by using a smart PLS-SEM approach, and it is advantageous over other regression-based methods to evaluate different latent constructs with several manifest variables []. The PLS-SEM research approach is a robust, flexible, and superior tool to build an adequate statistical model, while the PLS-SEM feature helps in achieving the predicted objective [,,]. Wan Afthanorhan [], and Astrachan et al. [] stress that reliable and valid confirmatory factor analysis is well achieved by using PLS-SEM path modeling. Consistent with the above arguments, PLS-SEM is a statistical tool that has been used by several researchers in various research areas in social sciences, including business research []. Moreover, PLS-SEM specifically permits the testing of complex models having multilevel effects; for instance, a mediating role and other complex models’ variables relationships []. This study applied smart PLS -SEM V-3.2.8 for data analysis and to calculate loadings, path coefficients, and weights; the study incorporated the bootstrapping technique to determine significance levels [].

Figure 5 displays the three steps of the data collection procedures. In the first phase, we selected the preliminary Islamic religiosity variables influencing the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development. In the second phase, we designed a pilot study to test and obtain a clear understanding of questionnaire items’ reliability and modified it accordingly. In the third and final step, we executed the survey and received feedback from the respondents.

Figure 5.

The procedure of data collection.

3.1. Preliminary List of Factors

Primarily, we identified over 30 influential factors affecting local perceptions of tourism development; we tested a pilot study by engaging 15 experts in the relevant field whose recommendations were incorporated into the questionnaire before starting the final phase by removing some unsuitable factors concerning the local conditions and the design of this single study. Factors affecting tourism development are shown in Table 3 below;

Table 3.

List of identified influencing factors for sustainable tourism development.

3.2. Designing a Questionnaire

We developed and distributed the revised version of the selected factors of the self-structured survey among the targeted population to receive the required data using a random sampling approach. We informed and trained the respondents about the purpose of this research, and we assured the respondents that all the data elicited is strictly confidential. The questionnaire had two sections on the respondents’ perceptions of tourism development. The survey also obtained the respondents’ general information, such as gender, age, education, profession, and location in the questionnaire’s first section, while its second section addressed the critical and influencing religiosity factors. The study invited respondents from the rural communities of the selected study areas to answer questions on the impact of sustainable tourism on their daily lives. The questionnaire utilized a five-point Likert-scale requiring individuals to rate their agreement levels from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5 (strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, agree = 3, neither agree nor disagree = 4, and strongly agree = 5).

3.3. Size of the Targeted Population Sample

The sample size of the population comprised of 508 valid responses and focused strictly on rural communities in the area of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. The respondents were required to be educated at least to a degree level. The researchers omitted uneducated people as they were hesitant to answer questions during the pilot test, and they were unaware of the survey’s importance. We educated and trained the respondents about the survey’s purpose, and the researchers gave the respondents 14 days to understand and fill out the survey.

3.4. Data Processing of the Questionnaire’s Feedback

After receiving the input from the targeted respondents, the researchers checked and screened all the questionnaires. Based on the completed and accurate responses, the researchers collected 508 adequately filled out surveys and scrutinized them to confirm the data accuracy. This study processed the data received and analyzed it by applying the analytical tool Smart PLS 3.2.8. In the final step, the statistical analysis provided the interpreted results as a useful insight and valuable evidence for the evaluation of the underlying factors. Additionally, 15 experts on rural development who already contributed to the pilot study during screening the crucial elements were invited again to offer their valuable expertise and provide their opinion on the data results.

4. Results

This study measured mean scores (M), standard deviation, excess kurtosis, and skewness, and all items of the scale showed consistent reliability and satisfactory results. Table 4 below shows demographic analysis of the respondents.

Table 4.

Demographic analysis of the respondents.

In Table 4, demographic analysis of the respondents showed that male participants (291) were in the majority (57.28%), while the number of female respondents was 217 (42.72%). The majority of participants (23.43%) came from Gilgit city, and a lower number was from Baltistan (17.91%). The majority of the respondents (51.18%) were within the 20 to 24 age range, whereas the 30 to 34 years age range showed the lowest participation.

Table 5 presents a comprehensive description of the descriptive statistical analysis showing the mean (M), standard deviation (SD) scores, and skewness and kurtosis values. The values of Table 5 revealed that the data presented satisfactory results and showed normal distribution.

Table 5.

Mean (M), std. deviation (SD), kurtosis, and skewness values.

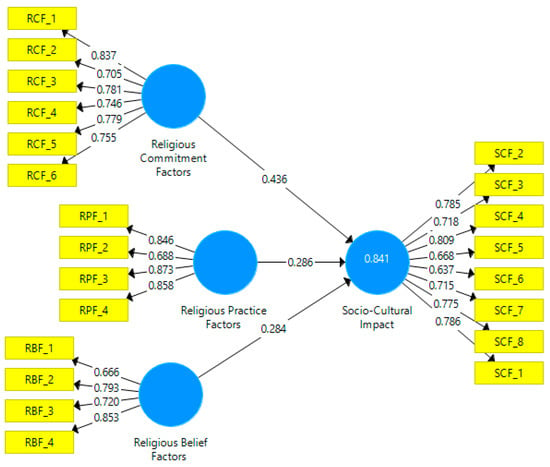

4.1. Evaluation of Outer Measurement Model

This study evaluated the quality and merit of measurement goodness to confirm the validity and reliability of the analysis process output by using the PLS-SEM technique. Based on Hair et al. [], this study assessed individual item reliability, discriminant validity, and the concurrent validity before test hypotheses of the designed model. This study used the smart PLS algorithm to ascertain each item’s reliability and the model’s measurement assessment as indicated in Figure 4. Hence, the indicator reliability examined the outer loadings of each measurement intended to measure a construct []. Composite reliability (CR) is the most common indicator to check the reliability of the internal consistency in the field of social sciences, and we applied this technique in this study []. Here, the composite reliability indicator showed that it was suitable to use PLS-SEM in this study []. Convergent validity presents the validity of constructs that measure how a specific measurement truly measures the construct that was intended to assess/measure, and it displays a positive correlation with other alternative measurements of the same construct. Hence, it shows the degree of correlation among the identical construct measures []. Hair et al. [] recommended a comprehensive research method of average variance extracted (AVE) for verifying the convergent validity for construct levels. The loading values were set to 0.4 according to the recommendations of Hair et al. The AVE value was set to 0.5, whereas the composite reliability must display a value of 0.7 []. Accordingly, in this study, we followed the recommended PLS-SEM method based on the previous literature, which suggested the approach of using repeated indicators of the model. Table 6 below shows that the measurement model’s results are exceeding the recommended values, which indicates that convergence validity is sufficient as presented in Table 6 below (see Figure 6).

Table 6.

The measurement model displays a convergent validity, alpha (α), and reliability.

Figure 6.

Measurement model (PLS-SEM algorithm). Note: Estimations of structural equations model.

4.2. Graphical Representation of Construct Validity and Reliability

Table 7 shows Fornell–Larcker criterion test as given below:

Table 7.

Fornell–Larcker criterion test.

4.3. Inner Structural Model’s Evaluation through Smart PLS

In this study, we evaluated and confirmed the validity and reliability of the measurement model. The next step in the evaluation process describes how to calculate inner structural model outcomes.

4.4. Calculating (R²) Value

Coefficients of determination calculate the variance and overall effect size illustrated in the endogenous constructs for the structural tourism model by calculating the predictive accuracy of the model. The inner path model value was 0.841 for the Islamic religiosity endogenous latent construct. It indicates that the model’s independent constructs significantly explained 84.10% of the variance regarding the perceived socio-cultural impact. The results reveal that the model’s three independent variables caused 84.10% of the change in the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism. Hair et al. [] and Henseler et al. [] explained that R² is considered to be substantial at a value of 0.75, moderate at 0.50, and weak at 0.26, respectively. In this study, a significant value of R² at 0.841 was obtained.

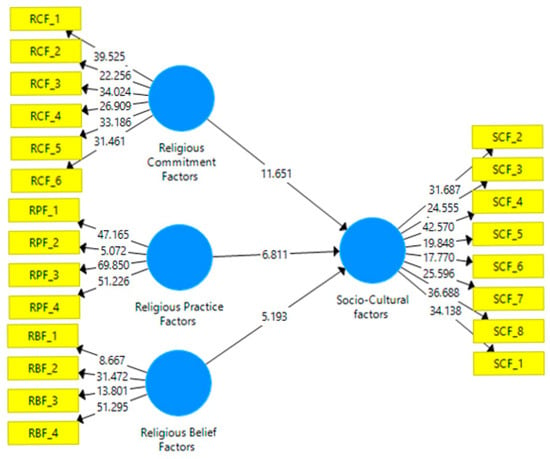

4.5. Path Coefficients and t-Value Estimation

We tested the significance of the proposed hypothesis by calculating the standardized beta (β) value. The value of beta (β) denoted the probable variation of the dependent construct in the study for the unit variation in independent constructs. We calculated the beta (β) value for each path in this hypothesized model. There will be greater and significant substantial effects on the endogenous latent construct if the beta (β) value is also higher and significant. The t-test is a technique to verify the significance level of the beta (β) value. In this study, we used a bootstrapping method to evaluate and assess the significance of the proposed hypothesis as shown in Table 8 [] (see Figure 7).

Table 8.

Results of Hypotheses Testing.

Figure 7.

Structural model (PLS-SEM bootstrapping analysis).

Table 8 reveals the analysis of the structural model. The results reveal that the H1 outcome depicting religious commitment factors showed a positive impact on the overall socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development as perceived by local communities and was statically significant at the 5% level (β = 0.436; t = 11.651; p = 0.000). Thus the results supported Hypothesis 1, which stated, “The community’s religious commitment positively affects the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development.” Hypothesis 2 stated, “A community’s religious practices positively affect the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development.” The finding of Table 8 endorsed positive relationships (β = 0.286, t = 6.811, p < 0.000) and confirmed H2. Finally, Hypothesis 3 stated, “A community’s religious beliefs form a positive relationship with the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism development.” Religious belief factors positively and significantly influence the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development, and the results of this study support H3 as shown Table 8 (β = 0.284, t = 5.193, p < 0.000). Figure 7 below presents the results.

According to Cohen, the (ƒ2) value has a strong effect at 0.35, a moderate effect at 0.15, and a weak effect at 0.02 []. Table 9 presents the values of (ƒ2) calculated through the PLS-SEM technique []. The results, as shown in Table 9, reveal the effect size and the satisfactory relationships between religious commitment (high effect 0.486), religious practice, and religious belief and the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development as perceived by the local communities.

Table 9.

Effect size: Measuring the effect size (ƒ2).

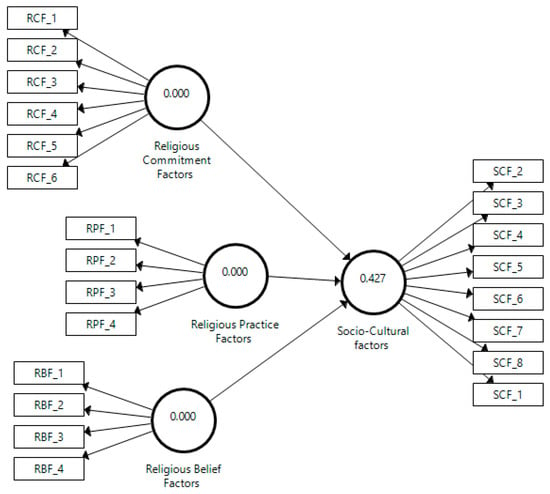

4.6. Model’s Predictive Relevance (Q2)

The predictive relevance (Q2) technique measures the smart PLS path model’s quality, and it is estimated by using the procedure of blindfolding []. In this study, we performed the cross-validated redundancy. The predictive relevance model (Q2) suggests that the proposed model might predict the study’s endogenous latent constructs. The predictive relevance (Q2) values calculated in the smart PLS-SEM must be (>0) greater than zero for the specific endogenous latent construct.

Figure 8 demonstrates the predictive relevance (Q2) for this particular model and shows its value at 0.427, which is higher than its threshold limit. These results support the predictive relevance of the path model, which is suitable for the endogenous constructs.

Figure 8.

The model’s predictive relevance (Q2).

4.7. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR)

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is an index of the average of the standardized residuals between the hypothesized and observed covariance matrices []. It is the measurement of a projected and estimated designed model fit []. If the SRMR value is equal or less than 0.08 it indicates satisfactory performance, a good fit, and that the study model is acceptable. The results show an SRMR value of 0.073, which is a good fit for the model, as shown in Table 10. The Chi-Square (χ2) value is 1665.878, and NFI shows the value of 0.772 in Table 10 [].

Table 10.

Model fit summary.

5. Discussion

Tourists’ spiritual, emotional, or physical needs determine their motivation for traveling []. Devesa, Laguna, and Palacios (2010) specified that visitors’ determinant and satisfaction levels are the motivational source for tourism []. From a tourists point of view, tourism is a response of travelers to felt needs and acquired values within their particular spatial, temporal, social, and monetary parameters []. Once their values and requirements are applied to the tourism scenario, tourists’ motivations for traveling constitute an essential parameter of their formation of expectations []. Tourists’ expectations determine their perception of the performance of services and products in addition to their opinions on their travel experiences. Travelers’ motivation subsequently influences their satisfaction []. Through our research, we attempted to recognize the major religious, socio-cultural, and economic impacts on local communities caused by sustainable tourism development in Pakistan. In this study, we applied the smart PLS-SEM method, and via a comprehensive analysis of the structural and measurement, model and results affirmed both models. We implemented an advanced technique using PLS-SEM software V-3.2.8, which is a commonly used multivariate analysis approach to calculate and assess the variance-based structural equations models by performing a statistical analysis []. It can test the relationships of a selected model’s latent and manifest variables simultaneously. We selected this technique because of its assessment ability concerning the psychometric properties of each latent construct, determining which the most important construct is and how it affects the socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism. The residents’ demographic profile indicated that the respondents were mostly male (291 = 57.28%; Female = 217, 42.72%). The findings of this study recognized the positive relationship of residents’ religiosity on sustainable tourism development in Pakistan, and the study results supported the proposed hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 stated that religious commitment factors revealed a positively impact (β = 0.436, t = 11.651, p = 0.000) on the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development. Hypothesis 2 claimed that community’s religious practices had a positively significant impact on developing sustainable tourism development. The results of this study confirmed Hypothesis 2 (β = 0.286, t = 6.811, p < 0.000), and the findings presented in Table 8 endorsed these positive relationships. In this study, Hypothesis 3 stated that residents’ religious beliefs positively affect the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development, and the results confirmed H3 as indicated (β = 0.284, t = 5.193, p < 0.000). The results revealed that R² = 0.841, showing three exogenous latent constructs that jointly explained 84.10% of the variance related to the socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism development. The result regarding predictive relevance revealed that Q2 = 0.427, which confirmed that the PLS path model’s quality is satisfactory concerning endogenous constructs. The results reveal that the entire proposed hypothesis is positive and statistically significant regarding acceptance. The findings show that the residents’ religiosity level (religious commitment, practices, and beliefs) affected the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development. This study establishes new empirical findings on sustainable tourism development. In this study, we examined the implications of local culture, heritage, and socioeconomic and socio-cultural effects on local inhabitants. Tourism destinations can promote marketing campaigns to attract religious tourists, and these such strategies can improve sustainable tourism development. Sustainable tourism can also create opportunities for small, family-oriented businesses [,].

Typically, Gilgit-Baltistan’s tumultuous past faces the left traces and enriches the domestic socio-cultural impacts, the gastronomy, and architecture; all these aspects are relevant factors that encourage the global tourists to visit these areas physically. However, previous studies evidence that heritage prevails in the rural northern regions as it usually better preserves heritages against external impacts, and the global tourists might avail the probable opportunity to experience the scenic beauty and original heritage time to time []. Scholars have highlighted the essential features that residents and their perceptions play to understand the development mechanism and process of sustainable tourism development [,]. Typically, residents influence sustainable tourism on their individual and collective living conditions [,]. Tourism development characteristically is perceived as an indispensable development opening for the local community in the view of the Government of Pakistan and the regional Government of Gilgit-Baltistan. The previous literature supports the primary purpose of this work as tourism destinations have become indispensable elements, and it has become increasingly essential in developing both economic and cultural factors to attract global tourists. Usually, tourism development is the source of development openings for the host communities because of its associated vital advantages such as building new parks, recreational opportunities in the areas, job opportunities, better health facilities, education, improved infrastructure, and residents’ better living standard. The results of this specific research also confirmed the findings of earlier surveys showing that developing sustainable tourism leads to cultural and natural environment protection and it increases the economic prosperity and job opportunities [,,,,,].

Sustainable tourism development in the destination typically generates an additional income for local administration budgets that utilized and invests for developing future tourism marketing strategies and conservation of the sustainable tourism attractions by guaranteeing the sustainability of tourist areas. The findings of this proposed research are consistent and in line with earlier research studies [,,]. According to the factual reality of residents, they perceive tourism development as playing an indispensable role credibly for social and economic benefits, and it is the common finding in the geographical areas. Because the host communities feel very proud to preserve their cultural heritage as it is amongst one of the global oldest civilizations. Concerning social problems, factors reporting the dimensions revealed positive feedback from the local communities, showing that residents with stronger religious beliefs perceived no damage: sustainable tourism development would not cause social problems in their regions. The results showed that more religiosity among local communities led to the perception that sustainable tourism development would be beneficial. The findings are similar to the results Harrill, (2004), Cavus and Tanrisevdi research [,,].

The results supported the many researchers who support three main aspects of religiosity. It was interestingly essential to note that scholars have stated that Islamic religiosity for believers based on the Quran and Hadith (belief and practice) []. The results showed that religious beliefs and religious commitment were very high among local people, and this religiosity showed association with the welcoming behavior of local people [,,,]. This finding of the present study is consistent with the previous finding of Hassan (2007), who found the same result in his research [,]. Richerson and Christiansen (2013, p. 23) and Lewens (2015, p. 147) claimed that past regional culture acclaims religion and explains the observations [,]. There are several natural sites, vibrant local cultures and UNESCO World Heritage Sites and Pakistan hope to develop sustainable tourism []. In this study, we identified three key dimensions of religiosity: religious belief, religious commitment, religious practice, and these findings are consistent with those of preceding studies, suggesting the existence of these two fundamental dimensions of individuals’ religiosity [,]. This study is novel and valuable, and it addresses monitoring and managing culturally, socially, and economically improved livelihoods and better health services, resulting from religiosity and socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism development, and it delivers original insights on the interaction between the religiosity of residents and tourism development.

6. Conclusions

This study was designed to examine the effect of Islamic religiosity of local Pakistani residents on socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism development in the northern regions of Pakistan, and it offers an insight into the local communities’ support for sustainable tourism development. In this study, we summarized some critical investigations in the literature (Table 2). These studies used various methodologies to examine the effects of different factors on the socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism. This study proposed an original method to explore and analyze the selected key constructs of religiosity on socio-cultural implications for sustainable tourism. The main contribution of this research, from a theoretical perspective, is the analysis of the residents’ socio-cultural impacts supporting tourism development, especially religiosity-related factors. Overall, northern Pakistani residents’ perceived socio-cultural impacts positively affect sustainable tourism development, and they showed their support and inclination for future sustainable tourism development in their regions. Among the socio-cultural impacts, the analysis of the residents’ religiosity revealed that tourism development leads to a greater acceptance of sustainable tourism in these areas. Moreover, this is the first study to investigate the effects of such religiosity-related factors on the perceived socio-cultural impact of tourism development in the Pakistani cultural context. The proposed tourism model of this research offers the most effective determinant of perceived socio-cultural benefits. The results of this study reveal that religious belief, religious commitment, and the spiritual practices of local communities show a significant and positive effect on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism by Pakistani residents. It indicates that the residents’ greater religiosity level showed a positive relationship with socio-cultural and economic effects.

Thus, Islamic religiosity influences the perception of residents regarding tourism development, and local communities understand that sustainable tourism development, infrastructure factors, and cultural activities play significant roles in community development. Tourism improves the community image and brings better facilities, health services, quality of life, education, improved infrastructure, and economic growth. This result confirms the statements of Butler and Suntikul (2017) and Raj and Griffin (2017), which explain that Islamic religiosity supports the development of the tourism industry [,]. The findings revealed that independent constructs of this tourism model explained 84.10% of the variance regarding the perceived socio-cultural impact and showed that three independent variables of the model caused 84.10% of the change in the socio-cultural effects caused by sustainable tourism. The findings indicate that residents’ communities are not merely limited to economic advantages; however, it also proved the non-monetary advantages of sustainable tourism development. The residents of these northern Pakistani areas are Muslims, and the findings were consistent with the those of prior studies and in line with the study of Hassan [], and in terms religiosity level, the residents have a firm commitment to their religion. By providing training and educating host communities residents with required skills, knowledge, and information, these residents can be trained and prepared to understand the advantages of tourism development. In response, they will actively be involved in tourism development and support the tourism industry naturally [].

Most foreign tourists come from Muslim countries and they share similar religious values and culture. Social exchange theory may also explain observations that residents accept or tolerate people who are closer to their social standing and resemble them culturally. Additionally, local communities’ have a positive perception of developing sustainable tourism in these rural areas with beautiful natural sites in Pakistan. Several scholars have conducted numerous studies on socio-cultural impacts, and social exchange theory has also explained this life cycle concept in tourism areas [,,]. As for the contextual and theoretical contribution of this innovative work to scientific knowledge, it is the first such work to be conducted in the context of Pakistan, examining residents’ religiosity level and the effect of religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of tourism development. In this study, we explored the effects of residents’ religiosity and their perceptions related to the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development [,,], as well as social distance theory [,,], and have supported sustainable tourism development since its earliest stages [,,].

6.1. Limitations and Recommendation

Concerning the empirical and hypothesized constraints of this study, we have presented theories supporting tourism development solely from the perspective of socio-cultural impacts. This tourism model’s findings were not identified and determined in the literature, and the results of this case study cannot be generalized to other Pakistani areas or other Muslim societies. This research study expands the body of knowledge regarding the residents’ religiosity level, and understanding socio-cultural impacts are vital for sustainable tourism development. The findings of this research might be of considerable interest to sustainable tourism development policy-makers, the tourism industry, and the developers to influence more sustainable policies and strategies in line with the preferences of local communities. This study recommends that future research studies should attempt to assess the relationship between individuals’ religiosity and the socio-cultural impacts on sustainable tourism development with large sample sizes in other regions of Pakistan. Ultimately, other Muslims societies, such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Iran, and Indonesia, are also sites of significant ethnic and cultural importance, historically significant and natural beauty, and improving our understanding of religiosity and socio-cultural impacts in developing sustainable tourism in these areas is important.

6.2. Implications

The results of this research have refined the theoretical basis to explain the interplay of socio-cultural factors that influence the host residents’ reaction to supporting tourism development. Additionally, these results have contributed to the existing body of scientific knowledge by developing, testing, and refining a tourism model that explained 84.10% of the variance in the host communities’ residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. Overall, this research expanded the existing body of scientific knowledge from a socio-cultural point of view to include the perspective of residents’ religiosity level as a factor supporting sustainable tourism development. The proposed tourism model, constructs, and measurement approach might be applicable in different regions of Pakistan and other tourism destinations, particularly in other Islamic countries and community-based sustainable tourism development projects. In this research, we utilized several underpinning theories, such as social exchange theory, self-determination theory, attachment theory, social representation theory, and social distance theory. Accordingly, the results of this research could support the suitability of the use of such theories. The tested tourism model showed that residents’ religiosity, community attachment, and knowledge on sustainable tourism development affects the local community’s support for sustainable tourism development. Considering this context, tourism policy-makers, practitioners, and developers might examine the behavior of residents to support tourism development in certain destinations []. The implications of these findings may provide significant advantages not only to academic researchers, but they might also provide benefits to other industries, such as service practitioners, tourism planners, and managers.

Planning a sustainable tourism destination, it requires a deep understanding of all involved stakeholders preferences, and the host communities []. The support of host residents is necessary as the hospitable, friendly host residents play the leading role in tourists’ destination satisfaction and it imrpoves the success of tourism development projects []. In the same context, findings showed that residents’ support for sustainable tourism development projects have parallel relationships with residents’ religiosity level and perceived socio-cultural impacts. Residents’ higher positive perceptions of the socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development support in their living areas. The findings of this study might assist policy-makers and practitioners in predicting host communities attitude, and preferences toward tourism development []. Policy makers, tourism developers, and tourism planners should pay attention to have the actual knowledge as well as an understanding of local communities, the dynamics of the influential factors, and how local communities residents perceive it before launching new tourism projects []. Having proper information about the tourism destinations, specific preferences, and the demographic profiles of destination residents is exceptionally beneficial for future planning, particularly in the destination places that are new for tourism development projects [,,].

Author Contributions

J.A. (Jaffar Abbas) has conceptualized the idea, completed Introduction, Literature, Discussion, Conclusion and edited the original manuscript, J.A. (Jaffar Aman) conceptualized the idea, drafted methodology and analysis section, S.B. collected data, S.M. provided resource, and helped resource. M.N. has reviewed the edited manuscript and provided resource.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support for APC from College of Management, Shenzhen University, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to MDPI professional language editing services to ensure that English grammar is free of mistakes for this manuscript. Jinzu Ling and Li Ben-qian supervised the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are well informed about the study’s objectives, provided consent, and have declared that they have no competing interest.

References

- Thyne, M.; Watkins, L.; Yoshida, M. Resident perceptions of tourism: The role of social distance. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Tasci, A.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Maruyama, N.U.; Hollas, C.R.; Aleshinloye, K.D. Residents’ attitude towards domestic tourists explained by contact, emotional solidarity and social distance. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya, E.; Teye, V.; Sönmez, S. Understanding Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in the Central Region of Ghana. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Müller, D.K.; Saarinen, J. Nordic Tourism: Issues and Cases; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.S. Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modeling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic Perspectives in Destination Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. The Tourism Area Life Cycle; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W.; Hall, C.M.; Jenkins, J. Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Suntikul, W. Tourism and Political Change; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tzfadia, E. Abusing Multiculturalism: The Politics of Recognition and Land Allocation in Israel. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2008, 26, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzi, S.M.; Mohd, R.S.; Zurinawati, M.; Sukyadi, D.; Mohd, H.M.H.; Suryadi, K.; Purnawarman, P. Heritage, Culture and Society: Research Agenda and Best Practices in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Almuhrzi, H.; Alriyami, H.; Scott, N. Tourism in the Arab World: An Industry Perspective; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, N.; Jafari, J.; Cai, L.A. Tourism in the Muslim World; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Simpson, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Sievänen, T.; Pröbstl, U. European Forest Recreation and Tourism: A Handbook; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Karpen, I.; Farrelly, F. Tourism Ethnocentrism and Its Effects on Tourist and Resident Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.T. Roots for Radicals: Organizing for Power, Action, and Justice; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.; Pittman, R. An Introduction to Community Development; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, S.; McGrath, B.; Phillips, R. The Routledge Handbook of Community Development: Perspectives from Around the Globe; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.T. Human Behavior in the Social Environment: Mezzo and Macro Contexts; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castelloe, P.; Watson, T.; White, C. Participatory Change. J. Community Pract. 2002, 10, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H.A. A conceptual framework of tourism social entrepreneurship for sustainable community development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwansyah, E. Geographic Information System (GIS) Using IDRISI Software: Application in Coastal Management; Geoinforma: Depok, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Asghari, F.B.; Mohammadi, A.A.; Dehghani, M.H.; Yousefi, M. Data on assessment of groundwater quality with application of ArcGIS in Zanjan, Iran. Data Brief 2018, 18, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchumnong, A. Development of a sustainable tourist destination based on the creative economy: A case study of Klong Kone Mangrove Community, Thailand. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, K.; Harun, N.Z.; Mansor, M. Place Meaning of the Historic Square as Tourism Attraction and Community Leisure Space. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Sasaki, N.; Jourdain, D.; Kim, S.M.; Shivakoti, P.G. Local livelihood under different governances of tourism development in China—A case study of Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Exploring Community Tourism in China: The Case of Nanshan Cultural Tourism Zone. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyim, P. Tourism Collaborative Governance and Rural Community Development in Finland: The Case of Vuonislahti. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.M.; Aslam, M.; Othman, N. Sustainable Tourism in the Global South: Communities, Environments and Management; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haralambides, T.H. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN GREECE: The Royal National Foundation and the Activities of its Central Committee for Community Development. Community Dev. J. 1966, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, P.; Kaplan, A. Foregrounding practice—Reaching for a responsive and ecological approach to community development: A conversational inquiry into the dialogical and developmental frameworks of community development. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Will sustainable tourism research be sustainable in the future? An opinion piece. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; González, M.; Caballero, R. A dynamic sustainable tourism evaluation using multiple benchmarks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D.; Vieregge, M. Residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A factor-cluster approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, K.S.; Black, R.; Cottrell, S. Sustainable Tourism and the Millennium Development Goals; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Rural Policy Reviews The New Rural Paradigm Policies and Governance: Policies and Governance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. Contradictions of Rural Tourism Initiatives in Rural Development Contexts: Finnish Rural Tourism Strategy Case Study. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyim, P. Tourism and rural development in western China: A case from Turpan. Community Dev. J. 2016, 51, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and Sustainable Development: Exploring the Theoretical Divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y. Rural tourism development in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, F.; Marais, M. Rural communities, the natural environment and development—Some challenges, some successes. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S. Sustainable Tourism in Island Destinations; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Family business in tourism: State of the Art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fursova, J. The ‘business of community development’ and the right to the city: Reflections on the neoliberalization processes in urban community development. Community Dev. J. 2016, 53, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.H. Nordic tourism: Issues and cases. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtudiner, Z.E.; Klein, G.; Kantor, J. How religiosity affects the attitudes of communities towards tourism in a sacred city: The case of Jerusalem. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J.L. Developing and Testing a Tourism Impact Scale. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. Tourism Marketing: On Both Sides of the Counter; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Katsoni, V.; Stratigea, A. Tourism and Culture in the Age of Innovation: Second International Conference IACuDiT, Athens 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D. Routledge Handbook of Hospitality Marketing; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, D.L.S.G.; Richards, G. Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2013; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, A. Being Ourselves to You: The Global Display of Cultures: By Nick Stanley. Middlesex University Press (Central Books, 99 Wallis Road, London, E9 5LN, UK) 1998, 211 pp (figures, photos, references, index) £14.95 Pbk. ISBN: 1-898253-16-1. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D.J. Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Specht, J. Architectural Tourism: Building for Urban Travel Destinations; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.P.E.; Murphy, A.E. Strategic Management for Tourism Communities: Bridging the Gaps; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Hashimoto, A. Chapter 9—Food tourism in the Niagara Region: The development of a nouvelle cuisine. In Food Tourism Around The World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 158–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, A. Tea and Tourism: Tourists, Traditions, and Transformations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H.P. The economic significance of tourism within the European community. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.S.; Pizam, A.; Mansfeld, Y. Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Hall, D. Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D. Natural Area Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sroypetch, S. The mutual gaze: Host and guest perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of backpacker tourism: A case study of the Yasawa Islands, Fiji. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2016, 5, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L. Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D.J. Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Musa, G. The relationship between Islamic religiosity and residents’ perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, S.; Swarbrooke, J. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, J.; Aman, J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Impact of Social Media on Learning Behavior for Sustainable Education: Evidence of Students from Selected Universities in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, P.; Courtney, P. Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordern, J. Religion and culture. Medicine 2016, 44, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, L. More religious, less dogmatic: Toward a general framework for gender differences in religion. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 75, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, A.G.B.; Seo, Y.; Buchanan-Oliver, M. Religion as a field of transcultural practices in multicultural marketplaces. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.; Robertson, R. Studying religion today: Controversiality and ‘objectivity’ in the sociology of religion. Religion 1991, 21, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. The uses and abuses of ‘secular religion’: Jules Monnerot’s path from communism to fascism. Hist. Eur. Ideas 2011, 37, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Altinay, L.; Kenebayeva, A. Religiosity and entrepreneurship behaviours. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 67, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Schoenrade, P.; Ventis, W.L. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.; Downey, C.A. Handbook of Race and Development in Mental Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Individual and His Religion, a Psychology Interpretation; Constable: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, H.M.; Hays, J.C.; Flint, E.P.; Koenig, H.G.; Blazer, D.G. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,851 older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000, 55, M400–M405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M. Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.J.; Chatters, L.M.; Levin, J. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social, Psychological, and Health Perspectives; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bilekli, I.; Inozu, M. Mental contamination: The effects of religiosity. J. Behav. Ther. Exper. Psychiatry 2018, 58, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion and Mental Health: Research and Clinical Applications; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, D.; Rosta, G. Religion and Modernity: An International Comparison; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin, D.H.; Koenig, H.G. Handbook of Religion and Mental Health; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mcfadden, S.H.; Brennan, M. New Directions in the Study of Late Life Religiousness and Spirituality; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallahmi, B. Psychological Perspectives on Religion and Religiosity; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B. The Statesman’s Yearbook 2006: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arjomand, S.A. The Political Dimensions of Religion; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Leganger-Krogstad, H. The Religious Dimension of Intercultural Education: Contributions to a Contextual Understanding; Lit: Münster, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.G.; Smither, J.W.; DeBode, J. The Effects of Religiosity on Ethical Judgments. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z. Black Mecca: The African Muslims of Harlem; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, I.E.; Sukabdi, Z.A. Is there peace within Islamic fundamentalists? When Islamic fundamentalism moderates the effect of meta-belief of friendship on positive perceptions and trust toward outgroup. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.Z.; Konje, J.C. Ethical and religious dilemmas of modern reproductive choices and the Islamic perspective. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 232, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aqeel, M.; Abbas, J.; Shaher, B.; Jaffar, A.; Sundas, J.; Zhang, W. The moderating role of social support for marital adjustment, depression, anxiety, and stress: Evidence from Pakistani working and nonworking women. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 244, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-mora, A.; Leal, A.; Roldán, J.L. Relationships between the EFQM model criteria: A study in Spanish universities. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2005, 16, 741–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, K.A.G.D.S. ICIE 2016 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship: ICIE2016; Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited: England, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for Building and Testing Behavioral Causal Theory: When to Choose It and How to Use It. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2014, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Afthanorhan, W.M.A.B. A Comparison Of Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Covariance Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) for Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. Technol. 2013, 2, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, C.B.; Patel, V.K.; Wanzenried, G. A comparative study of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for theory development in family firm research. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N.; Belhassen, Y. Drugs and risk-taking in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Pendergast, D.; Leggat, P. Tourism in Turbulent Times; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, H. Tourism and Violence; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imbaya, B.O.; Nthiga, R.W.; Sitati, N.W.; Lenaiyasa, P. Capacity building for inclusive growth in community-based tourism initiatives in Kenya. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N. Strategic Infrastructure Development for Economic Growth and Social Change; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]