Impediments to Sustaining South Korea’s Economic Development: Pathologies of Cooperation in Intra-Team Dynamics of Technology Commercialization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Model Development

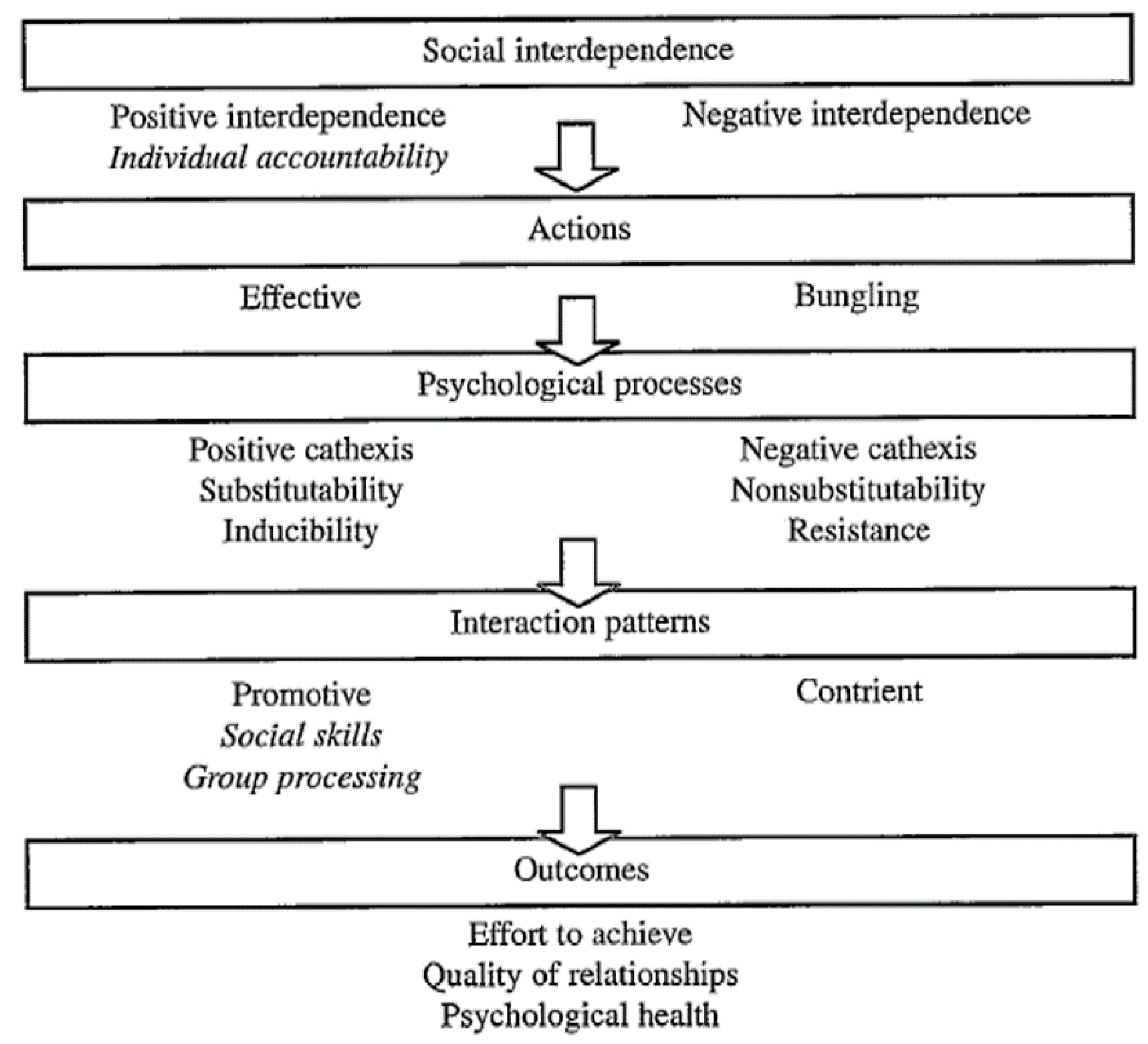

2.1. Social Interdependence Theory

2.1.1. Cathexis

2.1.2. Substitutability

2.1.3. Inducibility

2.2. Issues of Top-Down Approaches in Technology Commercialization Teams

2.2.1. Power Influence

2.2.2. Goal Multiplicity

2.2.3. Group-Based Rewards

2.3. Cooperation and Team Project Performance

2.4. Research Model

3. Research Methods and Data Collection

3.1. Methods and Measurments

3.2. Data Collection

4. Model Testing, Analysis and Findings

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Testing the Structural Model

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Implications and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

| (1) Strongly Disagree | (2) Fairly Disagree | (3) Somewhat Disagree | (4) Neutral | (5) Somewhat Agree | (6) Fairly Agree | (7) Strongly Agree | |

| Power-Influence—Intra-Team Power-Influence of the Leader/Manager | |||||||

| My boss/manager | |||||||

| tells me what to do and how to do it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| gives me detailed instructions on how things should be done | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| checks and/or criticizes my work regularly | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Multiplicity of Goals | |||||||

| Considering the goals of my team members and myself: | |||||||

| As a member of my team, I know exactly what I am expected to work on | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I have some personal goals (learning, rewards, relationships etc.) besides my team goals | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| When I do better on personal goals my team’s goal achievement improves | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Group-Based Rewards (Size/Frequency, Type, Allocation Methods) | |||||||

| Considering the distribution rewards for my team and myself | |||||||

| There are enough rewards for all team members | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| My efforts are rewarded appropriately | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| My efforts are rewarded timely | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Substitutability (Intra-team) | |||||||

| Considering the work behaviour (willingness/potential to substitute) of my team members (most of them) | |||||||

| I complete the assigned tasks very well | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I work extra for my team members to achieve our team goals | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| My team project still achieves its goals even if some of us are not working well | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Cathexis | |||||||

| Thinking about the relationships and cohesion between your team members, respond to the following statements: | |||||||

| Considering the inter-personal interactions of my team | |||||||

| Some of my best friends are on this team | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| For me, this team is the most important social group I belong to | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Inducibility—Inducibility refers to the willingness and openness to influence and be influenced by other’s opinions and actions. Please answer the following statements pertaining to inside team members: | |||||||

| I have frequent open discussions with my team members about our work | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| We choose the best course of action after deliberations | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| We generally accept good proposals from the experts amongst us | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Cooperative Interactions/Behavior | |||||||

| I try to comply with work rules and policies | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I try to implement policies and directives even when unobserved by others. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I fulfil my job responsibilities | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I complete the projects adequately | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I give my best at work | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I try to help my supervisor | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I put in extra effort | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| I lend an extra hand to others | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Team Project Performance | |||||||

| My team | |||||||

| members are motivated to have the team succeed. | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| successfully achieved most of our assigned targets or meet timelines (if projects are on-going) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| did better than most other teams in achieving assigned targets (or timelines) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| achievements were beyond the assigned targets | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Most of our organizational projects successfully achieved their targets (or timelines) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

References

- Freeman, C. Technology, Policy, and Economic Performance: Lessons from Japan; Pinter: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B.-Å. (Ed.) National Innovation Systems: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning; Printer: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Bae, Z.-T.; Choi, D.-K. Technology development processes: A model for a developing country with a global perspective. R D Manag. 1988, 18, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. Imitation to Innovation: The Dynamics of Korea’s Technological Learning; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, E.F. The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, J.-Y.; Hameed, T.; Ji, I. Catch-up in ICT standards: Policy, implementation and standards-setting in South Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, B.; Lim, Y. A comparative study of managerial features between public and private R&D organizations in Korea: Managerial and policy implications for public R&D organizations. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 1999, 17, 281–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.U. Promoting Technology Commercialization of Universities and Government-Funded Research Institutes; Science and Technology Policy Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2013; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Van Noorden, R. South Korea stretches lead in research investment. Nature 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, T.; von Staden, P.; Kwon, K.-S. Sustainable economic growth and the adaptability of a national system of innovation: A socio-cognitive explanation for South Korea’s mired technology transfer and commercialization process. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Jones, R.S. Sustaining High Growth through Innovation; OECD: Paris, France, 2005; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, J.-Y. Transition: From Catch-Up to Post Catch-Up. Asian J. Tech. Innov. 2016, 24 (Suppl. 1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, M.L.; Schumacker, R.E.; Gregg, M.; Howard, P.W.; Gable, R.A.; Zigmond, N. How Are They Now? Longer Term Effects of eCoaching through Online Bug-in-Ear Technology. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2014, 37, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S. Technological change and industrialization in the Asian newly industrializing economies: Achievements and challenges. In Technology, Learning and Innovation: Experiences of Newly Industrializing Countries; Kim, L., Nelson, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.; Pavitt, K. Technological Accumulation and Industrial Growth: Contrasts between Developed and Developing Countries. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1993, 2, 157–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R. The Co-evolution of Technology, Industrial Structure, and Supporting Institutions. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1994, 3, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edquist, C. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, B. Technology transfer and public policy: A review of research and theory. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 627–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, S.; Latham, S.; Kijewski, V. Individual choice or institutional practice: Which guides the technology transfer decision-making process? Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 1261–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, K.J.; Galavan, R.J.; Brusoni, S. Cognition and Innovation; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegl, M.; Gemuenden, H.G. Teamwork quality and the success of innovative projects: A theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; George, G.; Maltarich, M. Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’kane, C.; Mangematin, V.; Geoghegan, W.; Fitzgerald, C. University technology transfer offices: The search for identity to build legitimacy. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozeman, B.; Dietz, J.S.; Gaughan, M. Scientific and technical human capital: An alternative model for research evaluation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2001, 22, 716–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. New developments in social interdependence theory. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2005, 131, 285–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Chen, N.Y.; Huang, X.; Xu, D. Developing cooperative teams to support individual performance and well-being in a call center in China. Group Decis. Negot. 2014, 23, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A.; Hirst, G. Cooperation and teamwork for innovation. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2003; pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, C.K. Cooperative outcome interdependence, task reflexivity, and team effectiveness: A motivated information processing perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, M. An experimental study of the effects of co-operation and competition upon group process. Hum. Relat. 1949, 2, 199–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Andrews, I.R.; Struthers, J.T. Leadership influence: Goal interdependence and power. J. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 132, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A.; Atwater, L.E.; Link, A.N. Toward a model of the effective transfer of scientific knowledge from academicians to practitioners: Qualitative evidence from the commercialization of university technologies. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2004, 21, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, B.; Henrekson, M. Bottom-up versus top-down policies towards the commercialization of university intellectual property. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 639–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, B.H.; Eachus, H.T. Cooperation and competition in means-interdependent triads. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombag, H.F. Cooperation and competition in means-interdependent triads: A replication. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 4, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, D.S.; Kim, W.D. The evolutionary responses of Korean government research institutes in a changing national innovation system. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2005, 10, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.-S. Evolution of Universities and Government Policy: The case of South Korea. Asian J. Innov. Policy 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Mah, J.S. R&D policies of Korea and their implications for developing countries. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2013, 18, 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J. Public Policy 1986, 6, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandholtz, K.W. Making standards stick: A theory of coupled vs. decoupled compliance. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, A.; Gey, R.; Pretorius, A.; Günther, L. Decoupling from standards—Process management and technical innovation in software development organisations. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1350012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Boyne, G.A.; Walker, R.M. Dimensions of publicness and organizational performance: A review of the evidence. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 21, i301–i319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H.G.; Bozeman, B. Comparing public and private organizations: Empirical research and the power of the a priori. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2000, 10, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShon, R.P.; Kozlowski, S.W.; Schmidt, A.M.; Milner, K.R.; Wiechmann, D. A multiple-goal, multilevel model of feedback effects on the regulation of individual and team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 1035–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleingeld, A.; van Mierlo, H.; Arends, L. The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slocum Jr, J.W.; Cron, W.L.; Brown, S.P. The effect of goal conflict on performance. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2002, 9, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; King, L.A. Conflict among personal strivings: Immediate and long-term implications for psychological and physical well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J.R.; House, R.J.; Lirtzman, S.I. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G.; Backoff, R.W.; Levine, C.H. Comparing public and private organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 1976, 36, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatteo, J.S.; Eby, L.T.; Sundstrom, E. Team-based rewards: Current empirical evidence. Res. Organ. Behav. 1998, 20, 141–183. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, C.; Hunt, S.D. Salesperson cooperation: The influence of relational, task, organizational, and personal factors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M. Equity, equality, and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, G.S. The distribution of rewards and resources in groups and organizations. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 9, 91–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tjosvold, D. Cooperative and competitive goal approach to conflict: Accomplishments and challenges. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 47, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D. The dynamics of interdependence in organizations. Hum. Relat. 1986, 39, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauer, J.M.; Harackiewicz, J.M. The effects of cooperation and competition on intrinsic motivation and performance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageman, R. Interdependence and group effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M.A.; Magner, N.R. Confirmatory factor analysis of the styles of handling interpersonal conflict: First-order factor model and its invariance across groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, H.G. Public agencies and private firms: Incentive structures, goals, and individual roles. Adm. Soc. 1983, 15, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Stanne, M.B.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Does competition enhance or inhibit motor performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R.; Earley, P.C.; Van Dyne, L. Complex interdependence in task-performing groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Interpersonal attraction, social identification and psychological group formation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 15, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Widmeyer, W.N.; Brawley, L.R. The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. J. Sport Psychol. 1985, 7, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. Identity and cooperative behavior in groups. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2001, 4, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageman, R.; Hackman, J.R.; Lehman, E. Team diagnostic survey: Development of an instrument. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2005, 41, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.H.; Lee, H.C.; Yi, H.-C.; Jung, K.H.; Jung, K.H.; Chŏng, K.-H. Korean Management: Global Strategy and Cultural Transformation; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1997; Volume 81. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Billig, M.G.; Bundy, R.P.; Flament, C. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 1, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Brown, R.J.; Tajfel, H. Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 9, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, T.-K. Somehow Korean: Adolescent Psychology of Korean People; Joongang Books: Seoul, Korea, 2015. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Healing a Wary, Self-Cultivating Society through Education; Korea Development Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.-Y. The Relational Psychology of Korean People; Salim: Paju, Korea, 2007. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Choung, J.-Y.; Hwang, H.-R.; Choi, J.K. Post catch-up system transition failure: The case of ICT technology development in Korea. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2016, 24, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoshi, E.; Chang, E. Diversity management and the effects on employees’ organizational commitment: Evidence from Japan and Korea. J. World Bus. 2009, 44, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Hui, C.; Law, K. The leadership relationship in Hong Kong: Power, interdependence, and controversy. In Progress in Asian Social Psychology; Leung, K., Ed.; Wiley: Singapore, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Count | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 96 |

| Female | 19 | |

| Education | Bachelor | 23 |

| Master | 37 | |

| Doctorate | 51 | |

| Others/Not Mentioned | 4 | |

| Profession/Role | Tech. Transfer Professional | 38 |

| Scientist or Engineer | 55 | |

| Business Manager/Owner | 17 | |

| Ministry or Gov. Official | 1 | |

| Not mentioned | 4 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATIT (Cathexis Intra-Team) | 0.778 | 0.663 | 0.853 |

| COOP (Cooperative Behavior) | 0.935 | 0.692 | 0.947 |

| GBRIT (Group Based Rewards) | 0.902 | 0.835 | 0.938 |

| IND (Inducibility) | 0.766 | 0.686 | 0.867 |

| MGIT (Multiplicity of Goals) | 0.743 | 0.662 | 0.854 |

| PIIT (Power Influence) | 0.851 | 0.762 | 0.905 |

| ProjPerf (Project Performance) | 0.881 | 0.680 | 0.913 |

| SUB (Substitutability) | 0.747 | 0.664 | 0.854 |

| CATIT | COOP | GBRIT | IND | MGIT | PIIT | ProjPer | SUB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CATIT | 0.814 | |||||||

| COOP | −0.057 | 0.832 | ||||||

| GBRIT | 0.163 | 0.179 | 0.914 | |||||

| IND | −0.202 | 0.572 | 0.324 | 0.828 | ||||

| MGIT | −0.138 | 0.670 | 0.211 | 0.606 | 0.813 | |||

| PIIT | 0.140 | 0.101 | 0.427 | 0.251 | 0.101 | 0.873 | ||

| ProjPer | −0.146 | 0.431 | 0.312 | 0.677 | 0.488 | 0.279 | 0.824 | |

| SUB | −0.021 | 0.558 | 0.016 | 0.496 | 0.499 | −0.016 | 0.466 | 0.815 |

| Paths | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Power Influence > Resistance | H1 | Supported |

| Goal Multiplicity > Non-Substitutability | H2b | Supported |

| Goal Multiplicity > Resistance | H2b | Supported |

| Group Based Rewards > Substitutability | H3a | Not Supported |

| Group Based Rewards > Positive Cathexis | H3b | Not Supported |

| Group Based Rewards > Inducibility | H3c | Supported |

| Substitutability > Cooperation | H4 | Supported |

| Positive Cathexis > Cooperation | H5 | Not Supported |

| Inducibility > Cooperation | H6 | Supported |

| Cooperation > Team Project Performance | H7 | Supported |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hameed, T.; von Staden, P.; Kwon, K.-S. Impediments to Sustaining South Korea’s Economic Development: Pathologies of Cooperation in Intra-Team Dynamics of Technology Commercialization. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113040

Hameed T, von Staden P, Kwon K-S. Impediments to Sustaining South Korea’s Economic Development: Pathologies of Cooperation in Intra-Team Dynamics of Technology Commercialization. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113040

Chicago/Turabian StyleHameed, Tahir, Peter von Staden, and Ki-Seok Kwon. 2019. "Impediments to Sustaining South Korea’s Economic Development: Pathologies of Cooperation in Intra-Team Dynamics of Technology Commercialization" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113040

APA StyleHameed, T., von Staden, P., & Kwon, K.-S. (2019). Impediments to Sustaining South Korea’s Economic Development: Pathologies of Cooperation in Intra-Team Dynamics of Technology Commercialization. Sustainability, 11(11), 3040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113040