Abstract

The current recession has caused a large number of companies to reevaluate their valuable resources and ways to preserve and invest those resources. Given the relevance of employees as key stakeholders, developing a socially responsible orientation in human resource management for taking care of workers and their needs must be an essential process for business success. This study, based on stakeholder theory and a social integrative approach, examines the main drivers and barriers in the implementation of socially responsible actions in human resource management. The research uses a quantitative analysis based on questionnaires responded to by 85 human resource managers from large Spanish companies. We conclude that there are two significant drivers of socially responsible actions in human resource management (HRM): access to public subsidies and the improvement of the working environment. The main significant barriers highlighted by human resource managers are conflicts in decisions with boards and/or management teams and the lack of employees’ acceptance. The professional implications of the research are discussed at the end of the paper.

1. Introduction

The benefits of introducing corporate social responsibility (CSR) in management models and firm strategies have been a relevant issue examined in the past decade [1,2]. Several works have highlighted how CSR can increase organizational performance [3,4] through generating a sense of belonging and commitment among stakeholders [5,6]. Notwithstanding positive evidence regarding CSR benefits for employees [7], some companies still do not trust the value of developing socially responsible initiatives. Despite some academics who provide evidence of the importance of CSR as a strategic partner for human resource management (HRM) [8], it is necessary to examine in greater detail what factors reinforce or diminish this link. This manuscript addresses this question. Specifically, we intend to shed light on the main drivers and barriers for human resource managers in the introduction of a socially responsible orientation in HRM. First, it is necessary to understand what the terms “driver” and “barrier” mean in this manuscript. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a driver is considered “something that makes other things progress, develop, or grow stronger”, while a barrier can be defined as “anything used or acting to block something happening”.

The theoretical framework is supported by the stakeholder theory developed by Freeman [9], with special attention to the premises of Greenwood and Anderson [10], Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite [11], and Barrena-Martinez et al. [12], who identify employees as one of the most important stakeholder groups in the development of socially responsible actions in HRM. The manuscript acts as a theoretical complement to the foundations of the social integrative approach, which considers that the integration of the social demands of workers can improve their well-being and motivation, as well as add overall stakeholder value. The study considers the perceptions of human resource managers to be a main promoter of socially responsible behavior and practices in a company, focusing on the barriers and drivers they perceive in the implementation of socially responsible HRM. Our research results show that the drivers that have a significant effect on the degree of introduction of CSR into HRM are potential improvements in the working environment and access to public subsidies. The main significant barriers to the development of socially responsible behavior are potential conflicts in decisions with board/management teams and the lack of employee acceptance. Our conclusions and discussion of the research are provided at the end of the paper.

2. Human Resource Management and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Bridge through Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory is considered to be one of the main supports for explaining the benefits and integration of CSR actions in business management [13,14,15]. In all definitions, the fundamentals of this theory emphasize the importance of stakeholders in the course and success of CSR business activities. The definition proposed by the European Commission in its Renewed Social Responsibility Strategy, commonly accepted at the European level, defines CSR as “a process aimed at integrating social, environmental and ethical concerns, respect for human rights and consumer concerns in its business operations and its basic strategy, in order to: (1) maximize the creation of value for its owners, stakeholders and society in the broad sense; and to (2) identify, prevent and mitigate their potential adverse consequences on the environment” [16] (p. 7). In other words, the introduction of socially responsible elements in the daily management of companies legitimizes the companies’ activities vis-à-vis the groups with which they interact: shareholders, partners, suppliers, customers, public institutions, nongovernmental organizations, employees, and society in general [17,18].

However, given the multitude of stakeholders involved in organizational activities, authors such as Freeman [9], Goodpaster [19], and Clarkson [20] note the need for organizations to differentiate and prioritize among their stakeholders. Based on links with a company, these authors differentiate two kinds of stakeholders: (i) primary groups, those that have a formal contract with the organization and are essential for its proper functioning (owners, shareholders, employees, unions, customers, suppliers, etc.), and (ii) secondary groups, those who, although not directly involved in the economic activities of a company, can exercise a significant influence on its activity (citizens, competitors, local community, government, public administrations, etc.) [20] (p. 11). In this manuscript, according to this classification, employees are considered primary stakeholders for an HRM function that integrates a CSR orientation.

Goodpaster [19], Donaldson and Preston [21], and Fassin [22], among others, reveal the existence of different approaches that explain the behavior of companies in relation to their stakeholders. Goodpaster [19] distinguishes between two relevant approaches in the interpretation of stakeholder theory: (1) the strategic perspective, in which stakeholders are considered to be an instrument or vehicle for achieving the general objective of shareholders, and (2) the multi-fiduciary perspective, in which companies establish a relationship of quality and commitment with the company’s interest groups that goes beyond the economic exchanges that take place among these parties. Along this line, Boatright [23] and Freeman [24] advocate the integration of both approaches (strategic and multifiduciary) because they emphasize that all stakeholders are equally important and are needed for achieving maximum value for companies. On the other hand, Donaldson and Preston [21] propose the existence of three approaches through which the relations of a company and the relevant interest groups can be defined. Firstly, the descriptive approach is aimed at explaining that companies are set up and defined by a broad range of interest groups that must be taken into account, and that cooperation among all of them is necessary for achieving better organizational results. Secondly, the instrumental approach considers the stakeholder to be an instrument for achieving the company’s traditional objectives: profitability, stability, and growth. Finally, there is the normative approach, the support of which resides in how the management and satisfaction of the interests of the stakeholders must be the company’s unique objective, placing the achievement of economic profits in the background.

Although these theories have been widely considered in the literature as support for understanding CSR, there are discrepancies and conflicts among them, and it is necessary to examine what approach is most suitable in the integration of CSR into HRM for the benefit of employees and the generation of value for the company. Nowadays, the integration of CSR into the HRM function is one of the greatest challenges that human resource managers are facing. A wide range of factors such as technological advancement, the internationalization of companies, and legislative labor improvements have significantly contributed to the progress and update of the personnel management function, and CSR is a new paradigm demanded by society that can increase the value of HRM [25]. The link between CSR and HRM has recently been examined by Voegtlin and Greenwood [26], classifying these contributions into three main theoretical perspectives and providing a coherent conceptual bridge among topics (p. 189). Firstly, the instrumental perspective is based on the premise that the involvement of workers in CSR is instrumental for achieving greater economic outcomes for the organization. This perspective considers the basics of the economic theory of the firm, focusing its analysis on the “hard” HRM approach, profit maximization and, basically, how CSR and HRM can reinforce each other to improve a firm’s financial performance. Secondly, the social integrative approach explores how CSR and HRM can reinforce each other to create social benefit for the firm and its stakeholders. This approach is based on the relationship between CSR and the “soft” HRM view, examining how the integration of the social demands of workers can improve their well-being and motivation as well as overall stakeholder value. Finally, the political-CSR approach addresses the power of corporations in society and the concomitant responsibilities this power implies. This perspective considers the relevance of institutions in CSR and HRM.

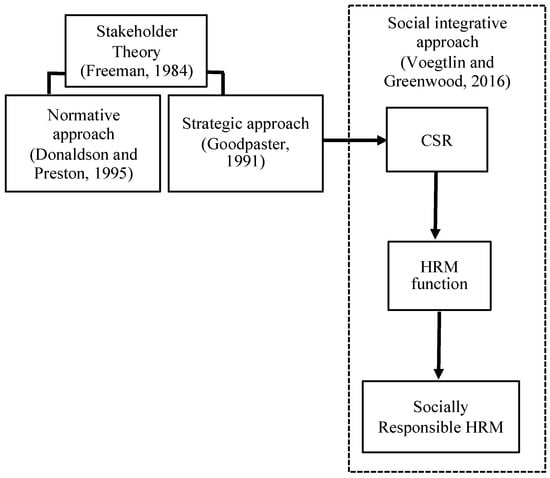

The social integrative perspective is closer to the approach taken in the current research, being a perfect theoretical complement to and evolution from a CSR stakeholder perspective to a socially responsible human resource management (SR-HRM) perspective (Figure 1). This approach considers employees as the main stakeholders, trying to create value for them through SR-HRM. SR-HRM can be defined as a new field of research that integrates the principles and values of CSR into the HRM function as a strategic partner. The value of SR-HRM models and the integration of CSR into HRM present different benefits across industries, organizational areas, and countries. For instance, Syed [27] reports: benefits for supply chain management for Zara (Spain) derived from a responsible approach toward workers reflected in occupational health and safety policy; benefits in HRM from better diversity management of employee recruitment for Peugeot (France), ensuring that the workforce comprises a “balance between the generations”; and the enhancement of employability and job market flexibility for Deutsche Bank (Germany), an essential process for restructuring the company.

Figure 1.

From traditional stakeholder’s approaches to SR-HRM models. Source: own elaboration.

In our interpretation, companies carry out socially responsible HRM by providing a consistent integration of CSR into the HRM function aimed at engaging and satisfying employees through social rewards that go beyond the strictly economic and legal, focusing on the well-being of workers and their families. Based on Figure 1, this paper aims to analyze the drivers and barriers that human resource managers find in the implementation of socially responsible HRM activities.

Authors like Sweeney [28,29] and Laudal [30] have classified several drivers and barriers for generic CSR activities. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no literature that examines drivers and barriers in SR-HRM. Thus, this paper will contribute to the literature by examining this area.

Drivers and Barriers in the Implementation of Social Responsibility Actions in HRM

The contributions of Sweeney [28,29] and Laudal [30] are a turning point in the identification of barriers and drivers in implementing social responsibility actions and serve as a framework for this manuscript. According to Sweeney [29] (p. 520), who conducted an analysis of large, small, and medium-size (SME) Irish companies, while large firms believe SMEs experience barriers such as perception and resource limitations, such as financial, human, and time constraints, in reality the only barrier noted by SMEs was that of financial constraint. The study carried out by Laudal [29] shows that at the stage of growth and internationalization, there are basically three main barriers and five drivers involved in the adoption of socially responsible behaviors by SMEs. The main barriers identified by Laudal [28] are: (i) cost/benefit analysis (the company’s ability to invest and monetize these actions); (ii) the risk of external control by certain stakeholders; and (iii) the risk of internal control by primary stakeholders. Laudal also identified some main drivers: (i) the sensitivity to local stakeholders (perceiving the company’s reputation as a conditioning factor); (ii) the geographical expansion of the company; (iii) the conformity or possibility of following leading companies; (iv) sensitivity to public perceptions (reputation); and (v) the removal of government regulation (understood as a condition for achieving greater autonomy and a license for operation for the company).

Although the barriers and drivers discussed above shed light on the identification of the situation in Ireland, it would be very interesting to know whether these studies could be replicated in Spain with similar or different results. This manuscript takes into account the identification of drivers and barriers found by Sweeney [28,29] and Laudal [30] in order to conduct a study of large Spanish companies. Sweeny combined a qualitative and quantitative study and mixed large companies and SMEs, while Laudal only reports evidence regarding SME drivers and barriers. This study aims to analyze the main drivers and barriers for CSR activities in large Spanish companies in the HRM department. This contribution will provide different results when compared with the results of Sweeney and Laudal, which only consider generic CSR activities. The study also incorporates new items related to potential drivers and barriers for human resource managers.

Although SMEs form a great percentage of effective companies (99.88%) in Spain, according to the European Commission’s Annual Report on SMEs [31] (p. 99), there has been a decrease in their contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) of 7%, and to gross fixed capital (GFCF) of 34%. Both aspects negatively affect the competitiveness of Spanish SMEs compared to European companies of the same size. This progressive loss of SMEs’ competitiveness puts the focus on the role that large Spanish companies must play in this economic crisis, as it is the protagonist not only for progressive internationalization but also for the adoption of more responsible and sustainable behavior. Additionally, these circumstances are reflected in the increase of verified CSR reports, with Spain being a statistical leader in reporting at the European level [32]. Based on the importance of developing indicators that measure socially responsible behavior in large Spanish companies, this paper aims to identify the determinants of CSR activities in the area of human resources in large Spanish companies. Two hypotheses are proposed that should allow us to identify the main drivers and barriers in the implementation of CSR in the field of HRM:

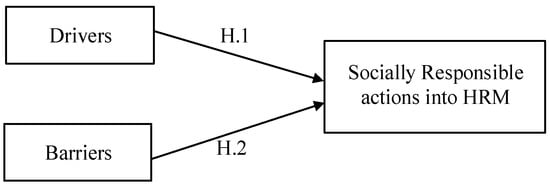

Hypothesis 1.

There are drivers that can significantly affect the extent to which large Spanish companies incorporate socially responsible actions into their human resource management.

Hypothesis 2.

There are barriers that can significantly affect the extent to which large Spanish companies incorporate socially responsible actions into their human resource management.

The methodology of the study is shown below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model and research hypotheses. Source: own elaboration.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

The sample of companies was selected using the SABI database (Sistema de Analisis de Balances Ibericos) based on three search filters: (i) companies established in Spain; (ii) active companies; and (iii) large companies. This filter determined a total population of 315 companies, from which a total of 85 observations were obtained. This represents a 27% share of the total sample and a sampling error of 9.09%.

The decision to carry out the study of Spanish companies is aimed at understanding the landscape of CSR in Spain in the field of human resource management. Professional reports in the field of CSR elaborated by Foretica [33,34] argue that in recent years Spain has been experiencing a consolidation and progressive understanding of the concept of a company’s social responsibility. The filter of active companies was used to eliminate inactive organizations, thus avoiding the error of increasing the size of the population and not obtaining answers from those companies. The study was carried out in large Spanish companies because these companies usually have a department or person in charge of the HRM function and processes (recruitment, planning, evaluation, etc.).

Human resource managers were identified as the most appropriate people to answer the questionnaire given their level of knowledge and understanding of the design and implementation of their organization’s HR policies and practices.

3.2. Measures

The items classified as barriers and drivers of responsible actions in the area of human resources were adapted from Sweeney’s questionnaire [29] and sent to the HRM department, requesting responses using a seven-point Likert scale (Appendix A). Among the main drivers when implementing responsible behavior in the area of human resources, we identified eight specific drivers, leaving open a ninth field called “others” in order to incorporate aspects not considered earlier. The drivers are: (i) improving employee welfare and satisfaction; (ii) improving the working environment among employees; (iii) enhancing employee performance; (iv) motivating and retaining existing employees; (v) attracting new candidates to the company; (vi) accessing public subsidies; (vii) maintaining and/or enhancing the reputation of the company; (viii) meeting pressures of market competitiveness; and (ix) other.

With regard to the barriers, seven items were identified, leaving an item called “other” for collecting other possible limitations, and containing two items not included by Sweeney [29] to provide a better contextualization of the study and research aim—the fifth item, “by decision of the human resource manager” and the sixth item, “for the current crisis period”. The barriers are: (i) lack of time; (ii) lack of resources; (iii) company size; (iv) board/management decisions; (v) human resource manager decisions; (vi) period of crisis/recession; (vii) lack of acceptance/response by workers; and (viii) other.

The SR-HRM is measured as the extent to which the company incorporates CSR activities—actions that integrate in a balanced way the ethical, social, human, and labor concerns of stakeholders—into HRM. This variable was pretested in interviews with a sample of 10 human resource managers in order to ensure their understanding and validity.

Furthermore, certain control variables were measured to provide a more realistic approximation of the sample profile.

The first control variable, the scope of the company, was included in the study because, as Quintás et al. [35,36] point out, this can make it possible to delimit the geographical space of the company’s exchange of goods and services, an aspect that can affect the resources of the company and, more specifically, its human capital management.

The measurement of scope of operations was made following the scale proposed by Quintás et al. [36] through a categorical variable measured with three response alternatives (1 = local scope, 2 = national scope, 3 = international scope). We included a fourth category (4 = European scope) following the theoretical recommendations of Brewster et al. [37], who underline the differences between the European and international environments and how this context can affect the HRM function.

The second control variable used in the study was the activity sector, highlighted by several authors in the literature as a determining factor in the analysis of the HRM function on the company’s results [38,39]. In order to define the main economic activity of each company, the Classification of National Economic Activities in Spain [40] was consulted. This measurement was made using three categories (1 = companies belonging to the primary sector, 2 = secondary sector, 3 = tertiary sector).

Finally, the size of the firm was considered the third control variable, understood as the number of total employees in the company [41]. Four categories were established for this measurement: (i) 251–500 employees; (ii) 501–750 employees; (iii) 751–1000 employees; and (iv) more than 1000 employees.

Table 1 shows that a large percentage of companies belong to the tertiary sector (60%), and a smaller proportion to the secondary (37.6%) and primary sectors (2.4%), respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis: Control variables (sample = 85).

With respect to the scope of operations, a high percentage of companies operate at the international level (62.4%), which, although the study was conducted in Spain, registered a smaller percentage at the local (16.5%), national (16.5%), and European levels (4.7%).

Ultimately, in relation to corporate size, most companies in the sample had a number of employees ranging from 251 to 500 (58.8%). Those firms with more than 1000 employees represent 21.2% of the companies in the study. Finally, those with numbers of workers between 501 and 750 represent 12.9% of the companies in the study and those between 751 and 1000 represent 7.1%.

The dependent variable of the study was the degree of incorporating CSR into HRM. Since it was an experimental variable, a seven-point Likert scale (1 = minimum, 7 = maximum) was used, being expressed as, “Indicate the extent to which the company incorporates CSR (ethical, social, human, and labor concerns) into HRM”.

4. Results

In order to understand the characteristics of the sample, a descriptive analysis of the data was carried out. The mean values and the standard deviation are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of dependent and independent variables (N = 85).

The degree of application of responsible management among the 85 companies indicates a good average (5.682). It was found that the drivers most valued by human resource managers are the effect that will generate improvement of employee performance (5.952), welfare and employee satisfaction (5.870), working environment (5.788), motivation of employees (5.729), the possibility of attracting new candidates (5.152), and the reputation related to these actions (5.058). The lowest values were meeting the pressures of the market (3.705) and accessing public subsidies (2.658). These results indicate a real concern among human resource managers for providing excellent and responsible results from the implementation of socially responsible practices in HRM.

The highest barriers to introducing responsible behavior in the area of human resources were lack of time (3.623) and resources (3.517) as well as the size of the company (3.141). The lowest values within the barriers to responsible human resource management were the conflict generated by the decisions with the management of the company (2.623) and the decision of the human resource managers themselves (2.141). This indicates that introducing a socially responsible orientation in HRM is a real challenge for HR managers, but probably they do not have the time or the resources to pursue this orientation.

In order to analyze whether barriers and drivers could affect the application of responsible behavior in the management of human resources, two models were developed. The software used for the analysis was the SPSS 21.0. The dependent variable is the degree of CSR introduced into HRM and the independent variables are the drivers and barriers for CSR activities. In order to test whether the barriers and drivers could affect the implementation of responsible management in human resource policies, we conducted two regression analyses.

The first regression analysis includes the degree of responsible management in human resource policies as a dependent variable and all the drivers as independent variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the linear regressions according to research hypothesis assumptions.

The regression analysis of Table 3 reports the existence of two significant drivers to explain the degree of implementation of responsible management in human resource policies: the improvement of working environment (p-value < 0.01) and the access to public subsidies (p-value < 0.05). A percentage of 27.9% in the adjusted R2 indicates an appropriate fit of the model.

The second regression analysis includes the barriers as independent variables (Table 4) to explain the inclusion of CSR into HRM.

Table 4.

Results of the linear regressions according to research hypothesis assumptions.

The regression analysis of Table 4 reports three significant relationships that can explain the degree of implementation of responsible management in human resource policies: the scope of operations of the company (p-value < 0.01); the board management decisions (p-value < 0.05), with a negative coefficient (this means for every unit increase in the independent variable, we expect a 0.226 unit decrease in dependent variable degree of CSR into HRM, holding all other variables constant); and the lack of employee acceptance (p-value < 0.05). A percentage of 23% in the adjusted R2 indicates an appropriate fit of the model.

The results of both regression analyses allow us to test the model’s two research hypotheses, shedding light on the Spanish drivers and barriers in the process of incorporating socially responsible behavior in the area of human resources.

5. Discussion

Our results provide academic and professional evidence of the existence of two significant drivers at work when large Spanish companies integrate CSR in the HRM area: the establishment of a good work environment and access to public subsidies. This finding empirically reinforces an important trend in the literature focused on analyzing how stakeholders’ perceptions of the ethical, social, and environmental activities undertaken by a company can generate forms of behavior in workers who are thereby likely to contribute more effort to their tasks and duties [17,30]. From an HRM perspective, the creation of a solid and positive work environment is essential for obtaining better individual and collective results from employees, hence the relevance of this result. These outcomes add value to arguments about the causes of corporate social responsibility unlike other studies, which have only analyzed the relationship or direct effects of CSR on performance variables. The “working environment” was one of the drivers most valued by managers, something that was tested through the regression analysis. This result is coherent with the social integrative approach highlighted in the conceptual model.

In contrast, the second significant driver, “access to public subsidies”, received one of the lowest scores according to its mean in the descriptive analysis (see Table 2). The negative sign in the regression analysis can be interpreted to mean that the consideration of subsidies in the implementation of CSR-HRM is not the main concern of human resource managers. In other words, the data show that companies that view subsidies as more important tend to have a lower degree of CSR implementation. This result is in accord with the social integrative approach, which emphasizes social benefits for employees. The result suggests that CSR in HRM is not driven by focusing only on the economic advantages of subsidies, but rather that CSR is driven with the goal of behaving responsibly with stakeholders, and specifically with employees, which goes beyond strictly economic and legal aspects.

The results allow us to test the first hypothesis about the existence of significant drivers in the implementation of socially responsible human resource management, with the improvement of the working environment being the essential driver in the introduction of SR-HRM.

Regarding the barriers to integration of CSR in HRM, the empirical results show that the decisions made by a company’s board of directors are a limiting factor in the adoption of social responsibility actions in human resource management. The critical success factors for the implementation of CSR should include a global vision of this business philosophy, and top management must share a commitment to that philosophy. It is possible that, in the long term, these social strategies will achieve the proposed improvement objectives. In this sense, it could be said that the conflict in the board regarding management decisions is not an important barrier to introducing a socially responsible orientation in HRM. The interpretation could be that the lowest relevance given to conflicted board management team decisions provides higher possibilities for introducing socially responsible HRM.

On the other hand, the results show that the barrier termed “lack of employee acceptance” is significant in the adoption of responsible management in human resources. In the descriptive analysis (Table 2), human resource managers scored this item lower (2.83) in relation to the others, not considering it to be a decisive barrier. This result needs to be examined and justified. In the field of human resource management literature, this dichotomy can be explained as a problem of perceptions regarding “intended” human resource practices desired by the company and “perceived” human resource practices as seen by employees [42,43]. The human resource manager could understand that socially responsible behavior should be implemented by the company with the purpose of improving employees’ working conditions, well-being, and satisfaction. Hence, managers do not consider the item “lack of employee acceptance” relevant in their initial assessment because the objective of SR-HRM is implicitly to satisfy the needs and working conditions of employees. Regarding the significant effect, human resource managers could be worried about what the employees’ real perceptions are regarding human resource management implementation. This means that it is necessary to have a correspondence or fit between “intended responsible management”, which comprises the ideals and desires of the company regarding socially responsible human resource management, and the real perception of responsible management. If the employees do not perceive socially responsible management with the same strength as human resource managers and board directors, this effort and investment cannot produce better results.

Regarding the significant role of scope of operations in the identification of barriers, this interpretation means that the greater the geographical scope in which companies operate, the greater the institutional pressures received by managers in the implementation of socially responsible actions for HRM. The literature suggests that institutional isomorphism can exert considerable pressure on multinationals (MNEs) to adopt CSR activities in order to achieve legitimacy in the eyes of the different stakeholders [44]. Legitimacy can be achieved by conforming to the laws in the environment in which the company operates according to coercive isomorphism, in accord with moral compliance, through normative isomorphism, and by adopting a common frame of practices adapted to specific situations via mimetic isomorphism [45]. The combination of these isomorphism strategies in the specific field of HRM must consider local stakeholders such as employees, trade unions, etc., but also take into account global stakeholders like financiers to maintain an adequate balance.

Additionally, the previous result supports the second hypothesis regarding the existence of significant barriers in the implementation of SR-HRM.

Our findings provide a different contribution than the studies of Sweeny and Laudal. In this manuscript, the scope of operations plays a significant role in the process of introducing a socially responsible orientation in HRM. Sweeney identifies the size of the company measured as the number of employees in SMEs in Ireland as an important variable in the implementation of CSR strategies. In our study, large companies show no significant differences in the implementation of SR-HRM. Sweeney’s research considers size differences between micro, small, and medium firms regarding CSR implementation and formalization. Consequently, the findings of our study in large companies do not contradict Sweeney’s results.

On the other hand, Laudal identifies a great number of significant drivers and barriers in MNEs in Norway. None of the drivers and barriers identified by Laudal are significant in this study. An interpretation of our results should be that the central area in this study is the human resource management department, and the human resource manager is the sample of the study and has specific goals and perceptions that differ from the CEO’s interests. Moreover, the framework of multinationals is greater and includes a large number of variables engaged in the interpretation and examination of CSR phenomena.

6. Conclusions

This research seeks to analyze the conditioning factors in the implementation of SR-HRM in large Spanish companies. The social integrative approach and stakeholder theory frame the employee as the central target for socially responsible HRM implementation. The significant drivers and barriers extracted from the analysis are in accord with the foundations of both approaches. The idea of improving the working environment is one of the most important drivers identified by managers and is clearly identified as a social benefit.

The article also contributes to the understanding that the human resource manager must play a key role in comprehending and disseminating social responsibility actions. Human resource managers are the strategic partners in the implementation of socially responsible actions. They must collaborate and convince the board of directors of the company that the investment in SR-HRM can produce better results in the company’s performance mainly through social benefits, as the social integrative approach suggests. One of the main barriers identified in the analysis is the potential conflict with the decisions of the board and/or the firm’s management team. Hence, practitioners must design effective communication strategies to support SR-HRM vis-à-vis a company’s directors and management.

The dependent variable of the study’s integration of CSR into HRM actions is one of the newest contributions, which is translated in the SR-HRM implementation. This variable has been tested by human resource managers and could be replicated in other international studies.

Although this study is exploratory, and potentially biased by the opinions of human resource managers, it has an innovative character due to the consideration of large Spanish companies. It is necessary to analyze in depth the reasons for adopting SR-HRM, taking into account the implications for the improvement and promotion of these actions by private and public institutions.

In the future, it would be very interesting to generate an interview-based qualitative study of large, medium, and small companies aimed at learning managers’ and employees’ opinions on the design and implementation of socially responsible policies in the area of human resources. The participation of more than one respondent could also verify the foundations of stakeholder theory, trying to compare the results by categories (employees vs. employers).

Although some Spanish drivers and barriers have been tested here, this paper has great value for human resource managers and chief executive officers of companies in establishing new paths in the design and implementation of socially responsible human resource policies and practices. Human resource managers must consider the mismatch between their perceptions regarding intended socially responsible human resource management and the implemented SR-HRM practices as perceived by employees. The consideration of employees’ perceptions in quantitative studies should add a significant check on whether the SR-HRM process is implemented correctly and could produce richer results for organizations in terms of their employee’s performance.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to curating and analyzing the data and writing the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Consejeria de Innovacion, Ciencia y Empresa (Junta de Andalucia-Spain) [grant number SEJ-1618].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire of the Study

Considering that responsible management voluntarily integrates ethical, social, labor, and human factors in managing the activities of the company and in its relations with its stakeholders (employees, shareholders, suppliers, customers, etc.), please answer the following questions:

1. Indicate the extent to which each of the following drivers works in favor of adoption of responsible management in human resources:

| Drivers of CSR in HRM (Items) | Minimum | Maximum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Improving employee welfare and satisfaction | |||||||

| Improving the working environment among employees | |||||||

| Motivating and retaining existing employees | |||||||

| Attracting new workers to the company | |||||||

| Accessing public subsidies | |||||||

| Maintaining and/or enhancing the reputation of the company | |||||||

| Meet pressures of market competitiveness | |||||||

| Other (Please specify). |

2. Indicate the extent to which each of the following barriers works against adoption of responsible management in human resources:

| Barriers of CSR in HRM (Items) | Minimum | Maximum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Lack of time | |||||||

| Lack of resources | |||||||

| Company size | |||||||

| Board management decision | |||||||

| Decision of the human resource manager | |||||||

| Period of crisis/recession | |||||||

| Lack of employee acceptance/response of workers | |||||||

| Other (Please specify). |

3. Indicate the extent to which the company incorporates CSR activities (actions that integrate in a balanced way the ethical, social, human, and labor concerns of stakeholders) into HRM:

Minimum 1  2

2  3

3  4

4  5

5  6

6  7

7  Maximum

Maximum

2

2  3

3  4

4  5

5  6

6  7

7  Maximum

MaximumReferences

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Socially responsible human resource policies and practices: Academic and professional validation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasolomou-Doukakis, I.; Krambia-Kapardis, M.; Katsioloudes, M. Corporate social responsibility: The way forward? Maybe not! A preliminary study in Cyprus. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2015, 17, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre Torres, O.; Enciso, M.I. Is socially responsible investment useful in Mexico? A multi-factor and ex-ante review. Contad. Adm. 2017, 62, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, K.H.; Li, D.X. The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S.; Mariappanadar, S. Health harm of work from the sustainable HRM perspective: Scale development and validation. Int. J. Manpower 2016, 37, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T.N.; McGuire, D. Human resource development and society: Human resource development’s role in embedding corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics in organizations. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2010, 12, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.; Anderson, E. I used to be an employee but now I am a stakeholder: Implications of labeling employees as stakeholders. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2009, 47, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buciuniene, I.; Kazlauskaite, R. The linkage between HRM, CSR and performance outcomes. Balt. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Research proposal on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and strategic human resource management. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 10, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandoña, A. The stakeholder theory and the common good. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.; Rupp, D.; Williams, C.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Renewed EU Strategy 2011–2014 for Corporate Social Responsibility. Brussels. 25 October 2011. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/com/com_com(2011)0681_/com_com(2011)0681_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, K.E. Business ethics and stakeholder analysis. Bus. Ethics Q. 1991, 1, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y. The stakeholder model refined. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatright, J.R. Fiduciary duties and the shareholder-management relation: Or, what’s so special about shareholders? Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Towards a configuration of socially responsible human resource management policies and practices: Findings from an academic consensus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, J.; Kramar, R. Integration of CSR with HRM: What Can We Learn from Best Practice Organisations in the European Union; CSRM–Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Management: St Lucia, Australia, 2008; pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, L. Corporate social responsibility in Ireland: Barriers and opportunities experienced by SMEs when undertaking CSR. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. A Study of Current Practice of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and an Examination of the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance Using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM); Dublin Institute of Technology: Dublin, Ireland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laudal, T. Drivers and barriers of CSR and the size and internationalization of firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Annual Report on European SMEs 2014/2015. SMEs Start Hiring again. Final Report. November 2015. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7c9fbfe0-e044-11e5-8fea-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Bonsón, E.; Bednárová, M. CSR reporting practices of Eurozone companies. Rev. Contabilidad 2015, 18, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretica. Corporate Social Responsibility in Spain Sustainable Companies, Competitive Economy. 2011. Available online: http://www.foretica.org/executive_summary_csr_in_spain.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Foretica. Report about the CSR State in Spain 2015. Available online: http://foretica.org/informe_foretica_2015.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Quintás, M.A.; Vázquez, X.H.; García, J.M.; Caballero, G. Geographical amplitude in the international generation of technology: Present situation and business determinants. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás, M.A.; Vázquez, X.H.; García, J.M.; Caballero, G. International generation of technology: An assessment of its intensity, motives and facilitators. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2009, 21, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, C.; Mayrhofer, W.; Morley, M. Human Resource Management in Europe-Evidence of Convergence? Butterworth-Heineman: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoutsoura, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance; Haas School of Business: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; Available online: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/111799p2 (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A. Human resource configurations, intellectual capital, and organizational performance. J. Manag. Issues 2004, 48, 337–360. [Google Scholar]

- Classification of National Economic Activities, REAL DECRETO 475/2007, 13 April, Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas CNAE 2009. Available online: http://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/clasificaciones/cnae09/cnae_2009_rd.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2017).

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilji, S.E.; Wang, X. ‘Intended’ and ‘implemented’ HRM: The missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Beddewela, E.; Fairbrass, J. Seeking legitimacy through CSR: Institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Di Maggio, P.J. The New Institutionalism in Organisational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).