Abstract

Background: Covering the defects around the calcaneus is still a largely debatable subject. In the classical view, the defects at the level of the foot can be treated only by a free flap. In a modern approach, it has been observed that for small or moderate foot defects, a local flap can be used. Methodology: In this case series, we have retrospectively selected the patients who were admitted to the orthopedic department for a calcaneal fracture and who presented soft-tissue complications during the treatment. The patients have been selected from the past five years if they have undergone reconstructive surgery with a local or regional flap. Results: By applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we found that out of 79 patients who have been admitted to the orthopedic department, only two patients met the criteria. Two flaps have been used to treat the defects that developed at the level of the calcaneus after traumatic injury of the foot. The reverse-flow sural flap, as a tunneled flap, had a good evolution, without vascular suffering of the flap. On the other hand, for defects at the medial level of the calcaneus, we have used the dorsalis pedis flap. The healing was fast, and the patient presented no complications at the level of the donor site. Conclusions: Both flaps presented a good evolution. We try to emphasize through this article that soft tissue defects around the non-weight-bearing area of the heel can also be treated through a non-microsurgical option. These two options can help the ortho-plastic team to manage difficult cases by avoiding a free flap or a split-thickness skin graft.

1. Introduction

Calcaneal fracture incidence is about 11.5 per 100,000 people or about 50–60% of the tarsal bone fracture (according to data from the USA and UK) [1,2]. Calcaneus fracture can be approached through a lateral incision (90% of the time), minimally invasive (for simple fractures), or a medial incision. In a multi-fragmentary, displaced, or malangulated fracture, AO recommends the lateral approach and open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). Simple fractures (two fragments only or intraarticular fracture—depression type) can be managed through a minimally invasive approach. The medial approach remains only for the sustentacular fracture of the calcaneus body [3]. Wound necrosis is the most important complication following ORIF, with an incidence ranging between 2% and 27%. The lateral approach is the most used approach, with an incidence of approximately 15% wound complications, especially at the level of the apex of the raised flap [3,4]. The lateral calcaneal artery vascularizes the skin surrounding the area of the approach. Identifying the approximate position of this perforator artery has improved the lateral calcaneal approach. It has been observed that prolonging the incision through the posterior area of the lateral malleolus has been associated with a higher incidence of wound complications, probably because of the iatrogenic lesion of this perforator artery [5]. The key to avoiding this local complication is to cut the skin at the border between thin and thick skin and dissect the flap under the fascia so that the vessels are surely contained in the flap.

Lower limb reconstruction has been a debated subject regarding the covering of the soft tissue defect. In the classical view, the defects at the level of the foot can be treated most of the time by a free flap [6,7]. In a modern approach, it has been observed that for small or moderate defects of the foot, in the reconstructive armamentarium, local fasciocutaneous flaps can also be found [8,9]. In high-energy trauma, the risk of soft tissue defects is high. In the exception of open fractures, which are not the subject of the article, there are two ways through which a defect may develop at the level of the wound. First of all, the necrosis of the soft tissues around the fracture can appear even if they have viable vascularization, but the dissection following the approach incision does not take into consideration the plan of the vessels, separating them from the adjacent tissues. The second situation is represented by the moment when the traumatic energy is high, the microvascularization may be impaired, and slowly the soft tissue is going to become necrotic, independently of the operative technique. Crush injuries can lead to local necrosis because of the vascular lesion, which appears at the level of microcirculation. To prevent infection, debridement is mandatory at the level of the wound until healthy tissue is reached [10,11].

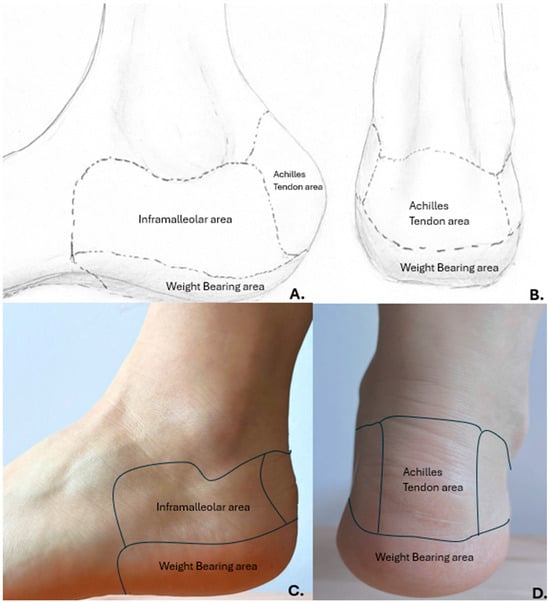

In the defects of the heel, multiple flaps have been researched. Some of the most commonly used are medial plantar artery island pedicle flap, reverse sural flap, free flaps (latissimus dorsi, anterolateral thigh perforator flaps, etc.) [12,13]. The defects at this level are difficult to treat because the area has a spherical shape and necessitates a flap with thick skin and good vascularization [14]. The area of the defect may be in the weight-bearing part of the heel or the non-weight-bearing part. It is important to mention that the non-weight-bearing area of the heel is still very important, and it necessitates the same amount of care as the other one because it is the part that supports the footwear. As the literature regarding the regional heel anatomy is scarce, we have proposed a method of describing the areas of the heel. Figure 1. It is described already that the boundary between the weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing area is the line of change between the thick epidermis and the thin and softer epidermis. Furthermore, the non-weight-bearing areas can be divided into areas under the malleoli (lateral and medial) and the dorsal part of the heel (the Achilles Tendon insertion). This way of dividing the non-weight-bearing part of the heel is based on the frequency of appearance of the pressure sores. The area of Achilles Tendon insertion is more prone to bed sores compared to the areas beneath the malleoli [15]. Another reason to divide the non-weight-bearing area of the heel in this particular way is the distribution of the arterial supply and perforators. The surface beneath the medial malleolus is vascularized through branches of the calcaneal branch of the posterior tibial artery. A few branches of the anterior medial malleolar branch of the anterior tibial artery may also provide the vascularization for this area. On the other side, the calcaneal branch of the peroneal artery is the main source of vascularization of the area beneath the lateral malleolus. Furthermore, a few branches of the anterior lateral malleolar branch of the anterior tibial artery may also provide vascularization for this area [16].

Figure 1.

Proposed anatomical division of the non-weight-bearing area of the heel. (A,B) personal drawing Dr. Necula B.R.; (C,D) human anatomic example.

Level 1 trauma centers have to overcome overcrowding in the Emergency Department (ED). One reason for the overwhelming situation is the lower performance of the lower-level centers and the territorial emergency network [17]. The crowding at the level of the ED has been shown to reduce the quality of the treatment of the traumatized patients by increasing the waiting time from presentation to damage-controlled resuscitation and also by delaying the specialized treatment [18]. Our hospital is a designated Level 2 Trauma center corresponding to an area of about 500,000 inhabitants. As in many Level 2 Trauma centers around the globe, our center is equipped to handle a wide range of injuries. Unfortunately, like other Level 2 Trauma centers, the microsurgical team is not available, and more complex cases must be transferred to a more specialized center.

The purpose of this paper is to present the possibility of managing trauma of the calcaneus in ortho-plastic teams successfully without the availability of microsurgery equipment.

2. Methodology

In this case, we have been retrospectively selecting the patients who have been admitted to the Orthopedic and Traumatology department of Brasov Clinical Emergency Hospital (Level 2 Trauma center) following an acute trauma with fracture of the calcaneus bone. The period of the search was between 2019 and February 2025.

The patients have been selected based on the following inclusion criteria: 1. Fracture of the calcaneus bone; 2. Associated soft tissue defect at the level of the non-weight-bearing area of the heel (as described previously in Figure 1); 3. Treatment by the orthoplastic team; 4. Covering the defect through the usage of local and regional pedicled flaps; 5. Follow-up of at least 6 months.

The exclusion criteria have been: 1. Patients transferred to the Level I trauma center; 2. Patients are treated by direct suture, secondary suture, or split-thickness skin graft.

The follow-up visits have been planned at 2, 4, 6, 8 weeks, 3, and 6 months after discharging the patient.

The team has been composed of 3 senior Orthopedic surgeons and 2 senior plastic surgeons. The patients have been initially admitted to the Orthopedic department, where the team has been made. The treatment has been decided by both teams.

3. Results

By applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we have found 79 patients who have been admitted to the orthopedic department for a calcaneus fracture. Out of these patients, only 5 patients developed skin necrosis at the level of the heel. Three patients presented skin necrosis at the level of the junction between the area of the posterior part of the heel and the area beneath the lateral malleoli during admission to the hospital. Out of these cases, two of them were treated conservatively, and another one was treated by using the split-thickness skin graft (STSG). The other two patients had a complex evolution and necessitated further reconstructive surgery.

Because of the patients’ progress, there were only two cases suitable for the article; we have decided to present them as follows. The percentage of local complications is similar to that described in the literature. The treatment method chosen to cover the defects led us to present the cases.

3.1. Case 1

A 38-year-old male without any other comorbidities presents to the hospital following a fall (approximately 2.5 m in height). The patient complained about the pain at the level of both heels. Locally, we have identified important edema of the right foot and moderate edema of the left, spontaneous and palpatory pain at the level of both heels, and the impossibility of weight bearing. By performing X-rays and CT scans of both distal lower limbs, we have made the primary diagnosis: Bilateral calcaneal fracture, highly comminuted on the right side (Müller/AO/OTA: 82-C3) with moderate displacement and no comminution or displacement on the left side (Müller/AO/OTA: 82-A2). Figure 2. Because of the important edema, the surgery has been postponed for 7 days, during which the patient received thromboprophylaxis, pain killers, and local therapy (elevation of the limbs, local cryotherapy) while having a bilateral cast immobilization.

Figure 2.

X-rays on the day of presentation in the Emergency Room (A), right calcaneus. (B) left calcaneus.

Local evolution was good, the edema diminished, and the conditions improved so that the patient was suitable for surgery. The right calcaneal fracture has been treated by ORIF with a calcaneal plate and screws and an additional autogenous bone graft harvested from the level of the right iliac crest through a lateral approach. Figure 3. For the left calcaneal fracture, the treatment has been non-surgical using immobilization with non-weight bearing for 6–8 weeks. The patient is discharged because of the early good local and general evolution.

Figure 3.

X-rays after ORIF of the right calcaneus fracture.

At the 2-week follow-up visit, we observed that the tegument and soft tissue around the wound presented moderate edema and skin with signs of suffering. As the lesion that appeared seems to have the potential to heal without any problem, the first therapeutic option has been expectation and local treatment. Unfortunately, at 5 weeks postoperatively, the area of suffering evolves to skin necrosis, and the patient has been admitted for specialized treatment. The necrotic area has been completely debrided, leading to a soft tissue defect of 3 cm × 4 cm inferior to the lateral malleoli, with no exposed osteosynthesis materials. No infection has been detected at the level of the defect. The first option of treatment was negative pressure wound therapy in order to obtain proper granulation tissue and eventually cover the defect with a split-thickness skin graft. In evolution, the wound did not have satisfactory granulation tissue after 2 weeks of therapy. Every week, the patient was checked by the plastic surgery department doctors to identify the moment for surgery as soon as possible.

At 7 weeks postoperatively, the patient has been admitted to the plastic surgery department. The X-rays showed the radiological union of both calcaneal fractures. The soft tissue defect did not extend, and no screws or plate have been exposed. Serial bacterial culture swabs have been collected, and the results showed no infection at the level of the wound. The wound bed presents a friable granulation tissue. The wound bed presents a friable granulation tissue. Two options of treatment have been prepared: the reverse flow sural flap and the dorsalis pedis flap. Figure 4. While measuring, we have observed that the RSf would need a wider space to turn around the ankle, and it may kink at the level of the distal part of the pedicle. After thorough preoperative planning, the DPf was chosen. The defect at the donor point was covered by using STSG. DPf has been designed as an island flap and has been tunneled under the Extensor Digiti longus tendons in order not to diminish the amplitude of tendon movement. Figure 5 and Figure 6. In the same procedure, the plate and screws have been removed after observing the development of callus at the level of the fracture site (confirming the imaging diagnostic performed preoperatively). Postoperatively, the cast immobilization has been kept for another 2 weeks to prevent movement at the level of the STSG.

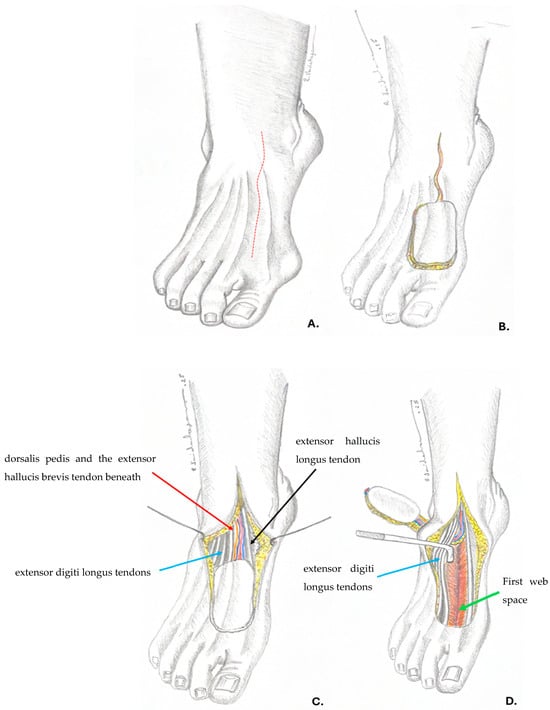

Figure 4.

Preoperative view. (A) planning for reverse sural flap. (B,C) planning for the dorsalis pedis flap. In the last picture, the defect can be observed.

Figure 5.

(A) preoperative planning, the anatomical position of the dorsalis pedis artery (red dotted line). (B) flap design and incision, prolonging the incision above the pedicle for further dissection. (C) the dissected flap; red arrow—dorsalis pedis and the extensor hallucis brevis tendon beneath; blue arrow—extensor digiti longus tendons; black arrow—extensor hallucis longus tendon. (D) creating the tunnel and moving the flap to the defect under the extensor digiti longus tendons (blue arrow); green arrow—first web space.—Drawings by Dr. Vaidahazan R. (personal collection).

Figure 6.

Intraoperative view of the dissected flap.

At the level of the donor site, we have identified a slower wound healing, but no reintervention was needed. At the 2-week follow-up meeting, we observed that 90% of the STSG had healed. At the 4-week follow-up meeting, the donor site had healed completely. The patient started to walk with partial weight bearing after 9 weeks from the ORIF. At 11 weeks, the patient was walking with full weight bearing. The postoperative evolution was good. Figure 7. The recipient site presented no complications, and the patient returned to his normal life and job 12 weeks after the flap was performed, without limitations.

Figure 7.

10 weeks Follow-up aspect; red arrow—final position of the flap.

3.2. Case 2

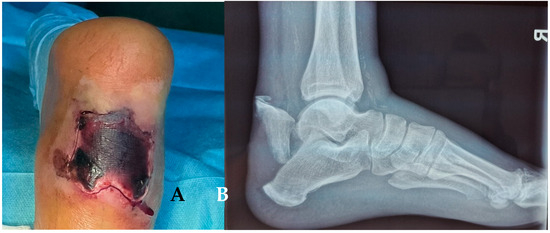

A 72-year-old male patient presents in the emergency room complaining of pain at the level of the right calcaneus, which started 3 weeks before when the patient sustained a fall from a ladder. The mechanism of the trauma was a combination of contusion at the level of the insertion of the Achilles Tendon and traction mixed with dorsiflexion of the foot. The pain was neglected, but at the level of the injury, the skin color started to change. The patient presented with an area of 5 cm × 5 cm of necrosis, acute pain in the dorsal aspect of the calcaneus, and the impossibility of full weight bearing and walking. The X-ray shows a calcaneal fracture (Müller/AO/OTA classification: 82-A1). Figure 8. The soft tissue area covering the calcaneal tuberosity presented this alteration of vascularization because of the fracture fragment attached to the Achilles tendon, which was pulled backwards and upward, generating pressure on the soft tissue from the inside.

Figure 8.

(A) Necrosis of the soft tissue covering the fracture site, 3 weeks after fracture. (B) X-ray of the ankle.

The patient was admitted to the orthopedic department, and the ortho-plastic team decided on the proper method of treatment. The team opted for a fix-and-flap approach because the necrotic soft tissue was the only covering the fracture fragment, and after the exclusion of the necrotic area, the osteosynthesis material would be exposed.

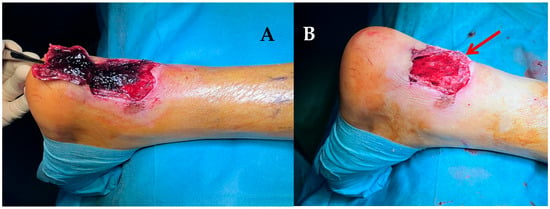

After debridement of the necrotic area, the soft tissue defect was about 6 cm × 7 cm. Figure 9. The fracture was reduced and fixed through the ORIF method with two canulated screws. Figure 10.

Figure 9.

(A) debridement of the necrotic area. (B) final soft-tissue defect. The bone fragment can be seen (red arrow) protruding through the defect.

Figure 10.

X-ray view after ORIF.

The soft tissue defect was treated with a local reverse sural flap. The pedicle of the flap was 4 cm wide. The flap was dissected, and the pedicle was dissected, and the flap was pivoted to the defect through a tunnel under the skin. The tunnel was performed in the supra-fascial plane, 9 cm long and 5 cm wide. The donor site was covered with STSG. Postoperatively, there was no concern regarding the blood flow to the flap. Figure 11.

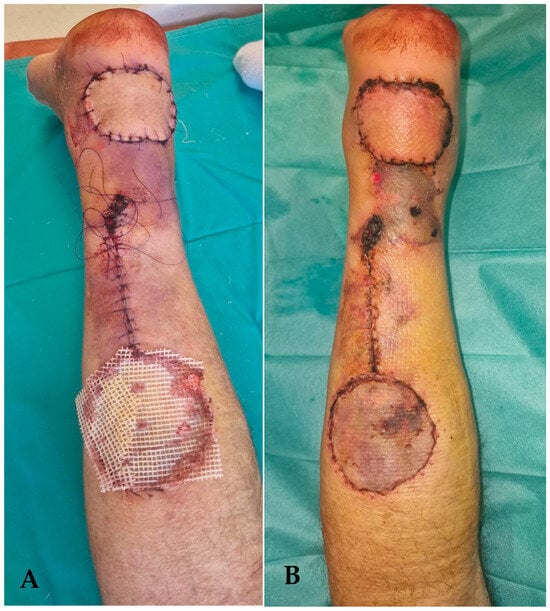

Figure 11.

Intraoperative design of the flap.

Unexpectedly, 2 weeks after surgery, a superficial necrosis of the skin area developed over the pedicle flap (5 cm × 5 cm), with a marginal area of necrosis (1 cm × 0.5 cm). Because it was superficial, it was treated only with local dressings. Although usually the flap is affected by vascular insufficiency, in our case, the complication developed at the level of the skin over the tunnel. It appeared around 10 days after the fix and flap surgery, and the area healed under conservative treatment in about 2 weeks. Figure 12.

Figure 12.

(A) follow-up picture at 4 days postoperatively. The area above the tunnel has a modified color, signaling the local suffering. (B) 2 weeks follow-up picture. The area of superficial necrosis over the tunnel can be shown.

In the follow-up period, the fracture showed signs of healing and callus formation. The patient presented twice with a skin rash, which was treated with local ointments by the dermatology department. Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Skin eruption at the level of the flap.

The 4 weeks after the surgery. Slowly, the position was changed from equine to functional. He began full weight-bearing at 12 weeks after the surgery, after obtaining the bone union (X-ray evaluation).

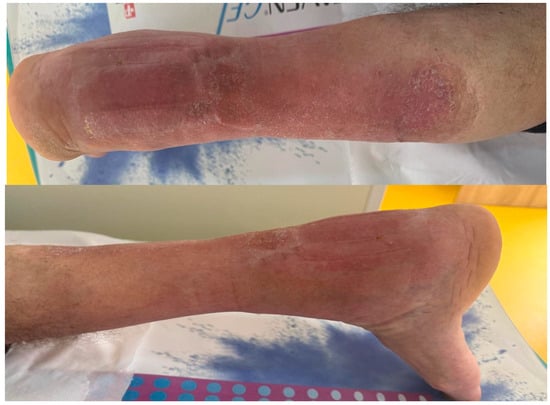

After 12 months of follow-up, there was little to no functional deficit. The range of motion between the 2 feet is comparable, and there is no pain or instability at the level of the ankle. Figure 14. The walking gait is similar between the 2 feet. At 12 months postoperatively, the screws have been extracted.

Figure 14.

Follow-up picture at 12 months.

4. Discussion

In the latest studies of reconstruction options for the weight-bearing soft tissue defects located at the level of the heel, most of the authors opt for using a free flap, the majority choosing the Anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap [19,20,21,22]. On the other hand, more and more options for local flaps have been described for the non-weight-bearing area. The popularity of these options seems to increase, as an alternative to more demanding (time, resources, and technique) options, such as free flaps. The propeller flap is slowly becoming a popular option to cover the defects around the heel and malleoli [23,24,25].

The flaps based on the perforator artery can have many designs, from advancement flaps to propeller flaps. With good preoperative planning, ultrasonography, or arteriography, the surgeons can identify more perforator arteries to base their flaps in order to cover the defects around the heel [26]. One option can be the perforators of the lateral calcaneal artery, on which propeller flaps and advancement flaps can be raised to cover defects around the lateral malleoli or posterior part of the calcaneus [27]. Another perforator artery has been described emerging from the posterior tibial artery. Based on this, a propeller flap can be designed [25]. The peroneal flap may give many perforators, and each of them can be used to create a propeller flap, which will cover a defect distally to the emergent perforator artery [28,29]. The perforator-based flaps can be designed to cover small defects around the non-weight-bearing region of the heel, but also larger defects, up to 24 cm × 10 cm [28].

Other pedicled flaps (island flaps) are also useful to treat the non-weight-bearing area. Among those, the most cited ones are the medial plantar island flap and the distal pedicled sural flap [30,31].

The reverse-flow sural flap (RSf) has been described in small cohort studies as a proper method of covering the defects around the heel after a calcaneus fracture. Daar et al. in the systematic review of 43 papers and 479 patients for whom a reverse sural flap has been used to treat the defects around the foot. They have observed that about 40% of the reverse-flow sural flaps have been used to cover the defects at the level of the heel. The review states that this is the most common location of the defect around the foot where this type of flap has been used [32]. This flap has proved to be easy to dissect and can cover the defect without vascular anastomosis. Furthermore, it has a low rate of complications [30,31,32]. In an impressive systematic review of over 80 papers that described the usage of the reverse sural flap in defects around the lower leg, ankle, and foot, Sanjib Tripathee et al. have concluded that complete flap loss appeared in only 2.5% of all the flaps performed [33].

Based on the branches emerging from the dorsal artery of the foot, a neurovascular fasciocutaneous flap can be generated. The dorsalis pedis flap (DPf) is very versatile. It has been used to cover the defects at the level of the foot or lower limb, and as a free flap for the hand and even lips [34,35,36,37]. In most cases, the dorsalis pedis flap has proved to be a suitable flap for covering defects by free transfer because of the long pedicle and large vessel caliber. The donor site morbidity is always discussed. The results of the research present low rates of complications at the level of the donor site, but the aesthetic aspect is presented as being poor [34,36,37].

One of the most common complications of RSf is the venous congestion of the flap, sometimes in combination with partial necrosis of the distal part of the flap. The necrosis of the distal part of the flap has been treated by debridement and local dressings, suggesting that only the superficial part of the flap was affected [30,38,39,40]. The proposed method to avoid venous congestion and partial flap necrosis was to make the pedicle wider, keeping more veins in the soft tissue [40]. Moreover, it has been proposed that the flap should not be transferred through a skin tunnel in order to avoid venous congestion [39]. We have chosen to transfer the flap through the tunnel in order to reduce the incision and the bulkiness of the flap, eventually improving the aesthetic aspect.

Although we have tunneled the flap, there was no issue with the venous congestion, but rather with the skin above the tunnel. The area became necrotic, but it was only the superficial layers of the skin, and the evolution was good using local dressings. In a large systematic review, Tripathee et al., in 2022, described that the most common complication in over 2592 RSfs has been a partial loss of the flap (7.85%) [33]. In the systematic review, there is no report of the necrosis of the roof of the tunnel through which the flap was transferred. The dimensions of the flap island and of the pedicle provided the perfect balance between the blood necessity, blood supply, and blood drainage. Moreover, the dissection of the tunnel was sufficiently wide so that the tunnel did not compress the pedicle. We suggest that the particularity of the case is the only complication presented, a complication not cited elsewhere in the literature. The biggest disadvantage of the RSf is the lack of sensitivity. As we have presented in the introduction, the area around the heel does not matter whether it is a weight-bearing area or a non-weight-bearing area; it is under constant stress because of the footwear and the pressure points. We consider that the lack of sensitivity presents a big risk of pressure sores and plantar ulcers. Nonetheless, RSf is a classical flap, very versatile, which cannot be abandoned from the reconstructive armamentarium because it has a long pedicle, and it can be harvested as a large flap. In this way, it can be easily transferred around the distal lower limb and allows a good reconstructive technique without the necessity of microsurgery.

The RSf has great advantages, such as short operative time, no need for microsurgery skills or instruments, wide rotation angle, and relatively low donor side morbidity [31]. Although it has a good rotation angle, when dealing with defects under the lateral malleoli, we believe that the pedicle is too bulky and deforms the ankle, raising further problems for the patient. This is the reason why, for the first case, we searched for an alternative.

The DPf is rarely studied in covering the defects at the level of the foot, as a local pedicled flap. Only a few case series are available in the literature [41]. The most common problem is donor site morbidity [42]. The advantage of the flap that we can highlight is the fact that it can be used as a neurovascular flap and keep the sensation around the heel. The disadvantage, as observed in the studies cited above, is that the donor area needs to be grafted (rarely can it be directly closed) and needs proper time to heal before using shoes again and returning to work [41,42,43].

The biggest disadvantage of the DPf is the donor site morbidity. The aesthetic aspect of the donor site after the STSG may be unsightly, especially because of the three-dimensional shape of the defect. Moreover, the function of the hallux may be lowered because of the STSG contraction or adhesion to the soft tissues. These complications must be part of the preoperative consent of the patient.

Edie Benedito Caetano et al. concluded that the DPf is only recommended in special conditions, such as second toe transfers, particularly because of the cosmetically unacceptable aspect of the donor site [36]. Samson et al. recommend that DPf should be used only as a last resort, as the donor site morbidity is important compared to other reconstructive options [44]. As we have respected the suggestion of the article written by Samson et al., the aesthetic aspect was acceptable, and there was no limitation of the function because of the STSG. We consider that the donor site morbidity is not so important as long as it does not necessitate a longer period to heal, it does not bring functional issues in the area, and the cosmetic aspect is acceptable (as the defect at the donor site was maintained as small as possible). As McCraw et al., we also recommend managing the donor site with great caution and closing it with great attention to avoid further damage, which may imply delayed healing [45]. Balancing the advantages of the DPf and the disadvantages of this flap, we have observed that it may be useful to use it as a local islanded flap because of the sensitivity of the flap. Using DPf in the non-weight-bearing area can prevent the appearance of bed sores, while the usage of the DPf in the weight-bearing area may prevent the development of plantar ulcers.

As it is difficult to assess both cases by the same scores, we consider that both had a good evolution because both patients returned to their normal life not later than 3 months after the first surgery. Furthermore, in both cases, bone union has been obtained, and we have clinically observed a normal range of motion of the ankle without pain.

We consider that the pedicled flaps will slowly advance, being more often used. It is a matter of time until suitable perforator arteries are extensively described and identified in order to create a local option for a flap to cover a small to medium defect. This paper is the foundation of a larger study on how to manage the difficult cases with defects around the foot, heel, and ankle.

5. Conclusions

The calcaneal fractures associated with soft tissue defects are a great burden on the healthcare system, being just one type of fracture that can lead to an overcrowded Level I trauma center. We try to emphasize through this article that soft tissue defects around the non-weight-bearing area of the heel can also be treated through a non-microsurgical option. The Reverse sural flap is an old, versatile option, used in this type of defect, while the dorsalis pedis flap is rarely cited to be used and presents a greater advantage of being innervated. These two options can help the ortho-plastic team to manage difficult cases by avoiding a free flap or a split-thickness skin graft.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.N. and R.V.; methodology, C.G.C.; resources, B.-R.N.; data curation, R.D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, B.-R.N.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, F.L.S.; supervision, F.L.S.; project administration, F.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it is a retrospective study. The ethical committee stated that the two cases presented during the retrospective study do not necessitate further approval, as the cases have not been recruited before the intervention.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RSf | Reverse-flow sural flap |

| DPf | Dorsalis pedis flap |

| ORIF | Open Reduction Internal Fixation |

References

- Davis, D.; Seaman, T.J.; Newton, E.J. Calcaneus Fractures; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, R.L.; Dean, C.; Pauly, K.R.; Wu, V. Calcaneus fractures, UpToDate, Mar 2025. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/calcaneus-fractures/print (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Buckley, R.; Sands, A. All Approaches to the Calcaneous, AO Surgery Reference. 2017. Available online: https://surgeryreference.aofoundation.org/orthopedic-trauma/adult-trauma/calcaneous/approach/all-approaches (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Watson, T.S. Soft Tissue Complications Following Calcaneal Fractures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007, 12, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khedr, A.; Reda, W.; Elkalyoby, A.S.; Abdelazeem, A. Skin and Wound Complications after Calcaneal Fracture Fixation. Orthoplastic Surg. Orthop. Care Int. J. 2018, 2, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Shaw, W. Reconstruction of foot injuries. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1983, 13, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMugaren, F.M.; Pak, C.J.; Suh, H.P.; Hong, J.P. Best Local Flaps for Lower Extremity Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2020, 8, e2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, G.G. Utility of Both Muscle and Fascia Flaps in Severe Lower Extremity Trauma. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2000, 48, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, G.G. Evidence-Based Medicine Lower Extremity Acute Trauma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, N.D.; Kovach, S.J., III; Levin, L.S. An Evidence-Based Approach to Lower Extremity Acute Trauma. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 127, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S. Crush Injuries and the Crush Syndrome. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2011, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, D.; Chaturvedi, G.; Manal, K.; Rao, C.V.P.; Michael, L.; Reena, M. Reconstruction of Heel Soft Tissue Defects: An Algorithm Based on Our Experience. World J. Plast. Surg. 2021, 10, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Dai, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Niu, K. The Treatment Experience of Different Types of Flaps for Repairing Soft Tissue Defects of the Heel. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 8445–8453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zheng, J.; Dong, Z. Reverse sural flap with an adipofascial extension for reconstruction of soft tissue defects with dead spaces in the heel and ankle. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2016, 42, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Management of heel pressure ulcers. In The Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in Primary and Secondary Care; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2014; pp. 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.W.; Attinger, C.E. Angiosomes and wound care in the diabetic foot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2010, 15, 439–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartini, M.; Carbone, A.; Demartini, A.; Giribone, L.; Oliva, M. Overcrowding in Emergency Department: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions—A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Robinson, R.D.; Duane, T.M.; Kirby, J.J.; Lyell, C.; Buca, S.; Gandhi, R. Role of ED crowding relative to trauma quality care in a Level 1 Trauma Center. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellamuthu, A.; Jayaraman, S.K.; Ramesh, B.A. Outcome Analysis Comparing Muscle and Fasciocutaneous Free Flaps for Heel Reconstruction: Meta-Analysis and Case Series. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2023, 56, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarya, A.H.; Tsai, K.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, S.-H.; Do, N.K.; Anggelia, M.R.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H. Free tissue transfers for reconstruction of weight-bearing heel defects: Flap selection, ulceration management, and contour revisions. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.-M.; Du, W.; Qing, L.-M.; Zhou, Z.-B.; Wu, P.-F.; Yu, F.; Pan, D.; Xiao, Y.-B.; Pang, X.-Y.; Liu, R.; et al. Reconstructive surgery for foot and ankle defects in pediatric patients: Comparison between anterolateral thigh perforator flaps and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps. Injury 2019, 50, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidung, D.; Fikatas, P.; Mandal, P.; Berns, M.D.; Barth, A.A.; Billner, M.; Megas, I.-F.; Reichert, B. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Foot Defects: A Case Series with Long-Term Follow-Up. Healthcare 2022, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Kafury, P.; Reyes-Arceo, F.; Lizardo, C.; Reina, F.; Zuluaga, M. Use of Propeller Flaps for the Reconstruction of Defects around the Ankle. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. Open 2023, 8, e38–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitonjam, M.; Khan, M.M.; Krishna, D.; Cheruvu, V.P.R.; Minz, R. Reconstruction of Foot and Ankle Defects: A Prospective Analysis of Functional and Aesthetic Outcomes. Cureus 2023, 15, e40946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepniewski, A.; Bingoel, A.S.; Jäckle, K.; Lehmann, W.; Felmerer, G. Two propeller flaps in a distal lower leg with bilateral defects as a single-stage procedure: A case report. JPRAS Open 2025, 44, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, M.; Cabrera, R.; Siu, A.; Altamirano, R.; Gutierrez, S. Perforator Propeller Flaps for the Coverage of Middle and Distal Leg Soft-tissue Defects. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, T.; Liza, J.; Karthikeyan, A.; Madhurbootheswaran, S.; Sugumar, M.; Sridharan, M. Lateral Calcaneal Artery Perforator/Propeller Flap in the Reconstruction of Posterior Heel Soft Tissue Defects. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2024, 58, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Lyu, Q.; Fan, X.; Shi, Y.; He, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y. Transplanted low-set perforating branch propeller flap of fibular artery for repairing calcaneal soft tissue defects. Chin. J. Trauma 2024, 12, 793–798. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Liao, H.; Li, J. Double-pedicle propeller flap for reconstruction of the foot and ankle: Anatomical study and clinical applications. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 4775–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clivatti, G.M.; Nascimento, B.B.D.; Ribeiro, R.D.A.; Milcheski, D.A.; Ayres, A.M.; Gemperli, R. Reverse Sural Flap For Lower Limb Reconstruction. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2022, 30, e248774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiadis, I.A.; Tsiampa, V.A.; Galanakos, S.P.; Georgakopoulos, G.D.; Gerostathopoulos, N.E.; Ionac, M.; Jiga, L.P.; Polyzois, V.D. The reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap for the treatment of traumatic, infectious or diabetic foot and ankle wounds: A retrospective review of 16 patients. Diabet. Foot Ankle 2011, 2, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daar, D.A.; Abdou, S.A.; David, J.A.; Kirby, D.J.; Wilson, S.C.; Saadeh, P.B. Revisiting the Reverse Sural Artery Flap in Distal Lower Extremity Reconstruction A Systematic Review and Risk Analysis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 84, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathee, S.; Basnet, S.J.; Lamichhane, A.; Hariani, L. How Safe Is Reverse Sural Flap?: A Systematic Review. Eplasty 2022, 3, e18. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.; Zhou, L.; Yang, S.; Xiao, B. Surgical Technique: Repair of Forefoot Skin and Soft Tissue Defects Using a Lateral Tarsal Flap With a Reverse Dorsalis Pedis Artery Pedicle: A Retrospective Study of 11 Patients. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 471, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Yin, G.; Hou, C.; Zhao, L.; Lin, H. Repair of a lateral malleolus defect with a composite pedicled second metatarsal flap. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 5291–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, S.A.; de Carvalho, B.L.F.; Andrade, A.C.; Caetano, M.B.F.; Vieira, L.A.; Caetano, E.B. Dorsalis pedis neurovascular flap, our experience. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2023, 31, e267572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciudad, P.; Maruccia, M.; Sapountzis, S.; Chen, H. Simultaneous reconstruction of the oral commissure, lip and buccal mucosa with microvascular transfer of combined first–second toe web and dorsalis pedis flap. Int. Wound J. 2014, 13, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qattan, M.M. A modified technique for harvesting the reverse sural artery flap from the upper part of the leg: Inclusion of a gastrocnemius muscle “cuff” around the sural pedicle. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2001, 47, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, S.; Aköz, T.; Akan, M. Soft-tissue reconstruction of the foot with distally based neurocutaneous flaps in diabetic patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2002, 48, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffer, B.S.; Timothy, A.S.; Matthew, J.C.; Paul, S.C.; David, L.B. The Reverse Superficial Sural Artery Flap Revisited for Complex Lower Extremity and Foot Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2015, 3, e519. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, V.; Singh, R.K. Dorsalis Pedis Artery-based Flap to Cover Nonhealing Wounds Over the Tendo Achillis—A Case Series. J. Orthop. Trauma Rehabil. 2017, 22, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ghelani, N.B.; Shah, A.; Patel, D.V.; Tomar, J.; Rajgor, D. Use of dorsalis pedis artery flap in coverage of distal lower leg defects. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 2995–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, M.; Mahendru, S.; Somia, N.; Pacifico, M.D. The dorsalis pedis fascial flap. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2009, 25, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, M.C.; Morris, S.F.; Tweed, A.E. Dorsalis pedis flap donor site: Acceptable or not? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraw, J.B.; Furlow, L.T., Jr. The dorsalis pedis arterialized flap. A clinical study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1975, 55, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).