Abstract

Background/Objectives: Adolescence is a sensitive period of development marked by significant changes. The quality of life (QoL) of adolescents with atopic dermatitis (AD) can be substantially impacted by the disease. The chronic nature of AD is particularly significant: due to recurring (relapsing) skin lesions, adolescents are likely exposed to greater stress and depressive symptoms than those experiencing transient or one-time symptoms. Aesthetic and functional AD skin lesions during adolescence lead to reduced happiness, high stress and depression. Methods: In this review, we wanted to present the current knowledge on mental health, psychological features and psychiatric comorbidity of adolescents with AD, based on the previous studies/research on this topic presented in the PubMed database. Results: Previous studies have confirmed that sleep disturbances, behavioral disorders, internalizing profiles, depression and anxiety, stress symptoms and suicidality represent the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities and psychological features in adolescents with AD. According to research data, adolescents with AD also reported a tendency toward feelings of sadness and hopelessness, and even suicidal thoughts and attempts. The relationship between sleep disturbances, psychiatric disorders, and suicidality in adolescents with AD is complex and multifaceted. Conclusions: Adequate social competencies are essential for healthy mental development, as their impairments may be associated with psychological alterations or psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence that potentially persist into adulthood. These findings highlight the need for continuous psychological evaluation and the implementation of intervention programs from an early age. Psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, accompanied by psychopharmaceuticals, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (when indicated), seem to be the most beneficial treatment options in AD patients who have the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities: depression and anxiety.

1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) often poses a significant burden for both sufferers and society due to the chronic and relapsing nature of the disease, which has been increasing in prevalence. According to the research literature, AD is a highly prevalent chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects both adults and adolescents [1]. It impacts approximately 5% to over 20% of children, although prevalence rates vary across countries and regions [2]. Most cases of AD begin before the age of five [2]. Beyond infancy, persistent AD is seen in approximately half of those diagnosed early in life, although AD can also develop in adulthood, accounting for about 25% of adult cases.

The most common manifestations of AD include eczematous skin lesions (acute or chronic), accompanied by itching, which consequently leads to sleep disturbances. Regarding age-specific clinical features of AD, based on Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria, presentation differs between children and adults. For instance, in infants and children, the disease commonly manifests as facial and extensor lesions, while in adults, it is characterized by flexural lichenification or linearity. In addition, concomitant/associated psychological conditions, such as depression, anxiety and sleep disorders, are also frequently observed [3]. Typically, AD runs a chronic and relapsing course. In most children with early-onset AD, the disease resolves by late childhood, though it may persist into adolescence and adulthood [2]. According to one extensive study, 20% of childhood cases had persistent disease eight years post-diagnosis, and up to 5% remained affected 20 years after diagnosis [4]. The age of onset was a key factor associated with AD persistence, as were sex (being female) and severity and duration of the disease.

It is well established that adolescents can also suffer from AD. The number of adolescents diagnosed with AD is gradually increasing, even as many aspects of etiology and treatment approaches remain unclear, classifying AD as a multidisciplinary disease [5,6,7]. Adolescence is a developmental period marked by the transition from childhood to adulthood (typically spanning ages 13–20), during which puberty and significant mental and emotional growth occur. During this phase, autonomy, personality, self-esteem, trust, intellectual abilities and learning capacities develop, which is very important for patients who suffer from AD, because AD can affect self-esteem and other related psychological features.

Although AD primarily manifests on the skin, its impact may extend to other systems, such as the central nervous system and psychological well-being [8]. Depression—either in full syndromal form or, more often, at the subsyndromal level—anxiety and suicidality represent the three most frequent psychiatric comorbidities in patients with AD whether they are children, adolescents or adults [9,10,11]. Adolescence is a particularly sensitive period of development, marked by numerous changes, which warrants special attention to this age group. The quality of life (QoL) of adolescents is significantly affected by the disease, depending not only on disease severity but also on other factors. The co-occurrence of psychiatric symptoms or disorders is the most significant comorbidity—among various other comorbidities—which is an additional factor associated with decreased QoL in adolescents with AD. By nature, AD is a chronic disease, and it has garnered increasing attention in recent decades. However, the burden of AD extends beyond physical symptoms, encompassing psychosocial effects on the individual [12,13,14,15]. Suicide is an issue particular to this sensitive age group regardless—teens face various challenging tasks in this formative period while still having an insufficiently stable personality—while in adolescents with AD, the risk of suicidal ideation, plans or even attempts is increased. Therefore, it is essential to consider the clinical, economic and human burden of AD in both adults and adolescents [3].

2. Materials and Methods

In this review we wanted to present current knowledge on the mental health, psychological features and psychiatric comorbidity of adolescents with AD, obtained/based on the previous studies on this topic. Thus, we analyzed data from studies found in the PubMed medical database. The search was performed in December 2024, and it yielded 20 research studies (Table 1) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. To identify relevant publications, we conducted a systematic search for English-language articles featuring the keywords “atopic dermatitis” or “eczema”, “adolescent”, and “mental health” within their titles or abstracts. The search was further refined by applying publication year filters (2000–2024) and age-specific filters, targeting studies involving children (birth–18 years) and adolescents (13–18 years). Subsequently, we manually reviewed the references of selected articles to identify additional studies not captured through the electronic search. To ensure the focus remained on adolescent populations, we excluded articles exclusively addressing children without adolescent data. Furthermore, non-research articles were removed from the final article list.

Table 1.

Data from studies on the mental health, psychological features and psychiatric comorbidity of adolescents with AD.

3. Results

According to the obtained results, there are various studies from all over the world that have been conducted on adolescent patients with AD, and which have analyzed mental health, psychological features and psychiatric comorbidity (Table 1) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

4. Discussion

4.1. Sleep Disturbances, Internalizing Profiles, Depression and Anxiety, Stress and Suicidality as the Most Prominent Psychological Traits and Psychiatric Comorbidities of Adolescents with AD

Many dermatological patients also suffered from psychiatric comorbidities [7,37,38,39]. This was even more significant for adolescents who undergo a period of life characterized by rapid changes and personal development. Adolescents face the challenge of adapting to their changing bodies, which can trigger increased stress and a reduced sense of happiness, as repeated and chronic inflammatory skin reactions cause visible and functional changes [38]. When individuals, including adolescents, experience negative social and psychological changes, this can lead to depression and anxiety and/or this can be associated with sleep disturbances, specific behavioral patterns, or in the most serious cases, even with suicidality [39]. Previous studies have confirmed that: sleep disturbances, behavioral disorders, internalizing profiles, depression and anxiety, stress symptoms and suicidality represent the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities and psychological traits in adolescents with AD.

Adolescents with AD have been found to experience more frequent sleep disturbances (primarily due to associated itching), including shorter sleep duration compared to non-atopic adolescents. Disrupted sleep negatively impacts adolescents’ neurocognitive functions and emotional health, increasing the risk of developing mental disorders. Sleep disturbances in AD are particularly notable in those with moderate-to-severe AD [31]. According to research on children, those with active AD report poorer sleep quality. Children with more severe active disease had worse sleep quality, while even children with mild AD experienced sleep disturbances more frequently [40]. Similarly, studies in adults confirm a higher prevalence of fatigue, insomnia and daytime sleepiness among AD patients [41,42].

A study conducted in Brazil predominantly focused on behavioral disorders in adolescents with AD. It found, in this patient population, a predominance of internalizing profiles with anxiety and depression as two of the most common symptoms within it. Oppositional, aggressive behaviors associated with a less present externalizing profile, seem to be more prevalent in a specific subpopulation of adolescents with AD—those with more pronounced, moderate/severe AD [31].

Depression (either in full syndromal form or, more frequently, at the subsyndromal level) and anxiety present significant psychiatric comorbidities in adolescents with AD, as high rates of depression and anxiety are noted in numerous studies [10,19,29,31,43]. One of those studies particularly stressed that adolescents with AD reported not only a high prevalence of depressive symptoms but also a tendency toward feelings of sadness and hopelessness and even suicidal thoughts and attempts [19].

The relationship between sleep disturbances, psychiatric disorders, and suicidality in adolescents with AD is complex and multifaceted. A study by Brazilian authors found high rates of sleep disturbances (60%) and anxiety/depression (25%) but also social problems (32%) in children and adolescents with AD [44]. One study highlighted not only sleep problems but also emphasized concomitant emotional reactivity (mood changes, feelings of panic, worry and emotional vulnerability), cognitive difficulties (worry, rigidity, obsession) and antisocial behaviors (such as peer violence, social exclusion, isolation, discrimination and stigmatization), as well as an increased risk of anxiety and depression as significant, bidirectionally associated components of psychiatric comorbidity in adolescents with AD [45].

In a Korean study of children and adolescents aged 12–18 years, adolescents with AD perceived themselves as unhappy, stressed, depressed and dissatisfied with their sleep quality when compared with adolescents without AD [25]. High levels of psychological stress (59.1%), depression (27.8%) and even suicidal thoughts (13.9%) were found in this specific population. This was especially true of male adolescents with AD, who experienced more pronounced subjective feelings of dissatisfaction/unhappiness (e.g., due to sleep disturbances), implicating the importance of subjective perception of experienced stress. Several studies have confirmed that patients with AD have a high prevalence of sleep disorders, depression, and anxiety but also reduced QoL in the adult, child and adolescent populations [7,19,31,42,46,47,48].

When considering and analyzing psychological factors in patients with AD, gender differences are also noted. Female adolescents were found to be more than twice as likely to report stress and depressive symptoms compared to male adolescents [7]. This aligns with earlier observations that women with AD more often experience high psychological stress, anxiety and depression than men, possibly due to greater concern for their physical appearance, which can have a stronger psychological impact on them [48]. In addition, female adolescents experience new hormonal changes (e.g., menstruation), and symptoms of AD tend to worsen in the premenstrual or ovulatory phase, suggesting that these physiological hormonal differences between the genders may explain significant variations in stress and depression symptoms [7].

The chronic nature of AD is particularly significant. Adolescents with recurring (relapsing) skin lesions are more likely to experience stress and depressive symptoms than those with transient or one-time symptoms [7]. Regarding psychological stress in AD patients, an earlier study reported that 46% of adolescents with high stress levels, and 21% with moderate stress levels, suffer from AD. However, it is important to recognize that stress can be both a cause and a consequence of AD [39,49]. Thus, managing stress levels in adolescents with AD could be crucial for improving patients’ mental health [7]. Other factors, such as socioeconomic status, also influence the condition of patients with AD. Adolescents with AD from low socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to exhibit high psychological stress and depressive symptoms compared to adolescents from middle and high socio-economic backgrounds. Several studies have reported that low socio-economic status is associated with higher stress levels (and elevated cortisol) and a higher incidence of additional dermatoses [50]. Adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds are also less aware of AD manifestations and often delay diagnosis or have limited access to medical care (diagnosis and treatment) [29].

The severity of AD has a notable impact on psychological status over time. A 10-year follow-up study involving 11,181 children showed an increase in the percentage of depression over time (6% at age 10, 21.6% at age 18) and more frequent symptoms of depression and an internalizing profile in patients with severe AD [29,31]. However, some factors may influence the assessment of behavioral disorders based on the severity of AD, such as comorbid asthma in those with mild AD. It is important to note that adequate social competence is essential for healthy mental development, as its impairment may be associated with psychological disorders in childhood and adolescence and potentially persist into adulthood [31,51,52].

4.2. Functioning and Quality of Life, Behavioral Disorders, Attention Disturbances/ADHD and Suicidal Ideations of Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis

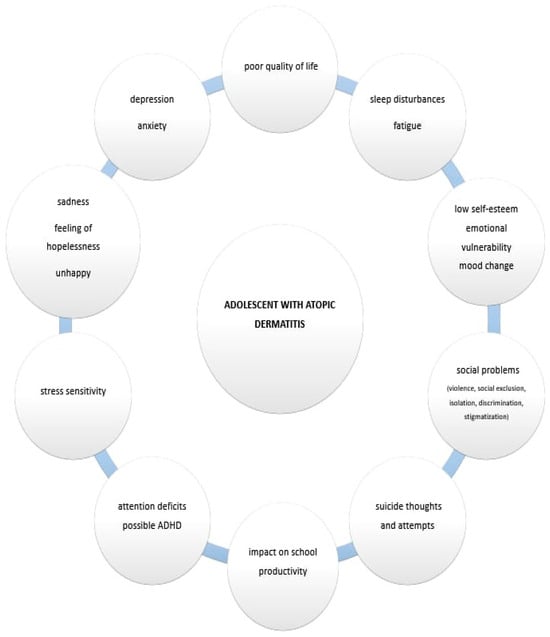

How well an individual functions day-to-day at school/work, socially and with family generally reflects an individual’s well-being. A recent study has documented significant disruptions in AD patients’ QoL such as school or work absences due to AD [53]. Frequent exacerbations and worsening of the disease negatively impact school productivity [54]. Additionally, in one international study, 32% of participants reported that AD affected their school or work life, and 14% of adult participants stated that AD hindered career advancement [54]. Furthermore, AD is strongly associated with more pronounced emotional disturbances, behavioral issues, hyperactivity symptoms and inattention, which often impact social relationships [55]. Adolescents with AD also report greater challenges in peer relationships [27,45]. Figure 1 shows the various aspects of AD in adolescents.

Figure 1.

The various aspects of AD in adolescents.

Aesthetic and functional skin lesions due to AD during adolescence lead to reduced happiness, high stress and depression [38]. Previous research has shown that patients/adolescents with AD may struggle with establishing a healthy body image and may experience negative social and psychological consequences [39]. Children and adolescents with AD often exhibit reduced social competence, particularly in activities such as play [31,56]. The previously mentioned study from Brazil revealed impaired social competence in children with AD compared to controls and a significant impact on their daily activities (median: AD 2.5 versus control 5.0). It also reported a higher prevalence of internalizing profiles (median 22.0 versus 12.0), somatic problems (median 5.0 versus 2.0), anxiety/depression (9.0 versus 5.0) and aggressive behavior (18.0 versus 11.0) [31].

Behavioral disorders are relatively common in children and adolescents with AD. One study on 915 adolescents with atopic diseases (mean age 13.3 years) using self-reports and parental assessments found a link between atopic diseases and adolescents’ peer relationship problems [55,57]. Thus, AD was associated with more frequent emotional problems, behavioral issues and hyperactivity/inattention in younger children, likely due to accompanying itching that causes restlessness and inappropriate behaviors. However, AD symptoms often improve during adolescence. In a study of 100 AD patients (mean age 11 ± 3 years), borderline findings or deviations were observed for factors such as overall social competence (75%), internalization (57%), externalization (27%) and aggressive behavior (18%) [31]. Patients with moderate/severe AD had a higher prevalence of aggressive behavior (27.9% versus 10.5%) and sleep disorders (32.6% versus 15.8%) when compared to those with mild AD. Children on immunosuppressive/immunobiological treatments demonstrated lower rates of normal social competence (53% versus 83%). These factors are linked to a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, stress, suicidal thoughts and suicidal behavior among adolescents with AD [19,24,45]. The severity of AD is important, as moderate/severe cases are more associated with mental disorders (e.g., sleep problems and emotional reactivity) than mild cases, indicating a need for appropriate treatment to address both physical and mental health [44,45].

Attention deficits and possible ADHD are also concerns in these younger patients. Patients with moderate-to-severe AD often experience chronic intense itching and sleep disturbances, which, according to parents and teachers, may lead to attention problems [35]. In one study of 44 participants (mean age 15 years), AD significantly affected sleep, QoL and comorbid anxiety and depression symptoms [35]. Atypical sensory profiles were also reported: sensory hypersensitivity (38.6%), sensory avoidance (50%) and low registration (hyposensitivity, 36.4%) [35]. In adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD without a formal ADHD diagnosis, no significant attention issues were observed compared to similar peers [35]. However, research shows that children with AD report inattention symptoms and a higher prevalence of ADHD-like symptoms. Severe AD in preschool children has been linked to poor sleep and attention dysregulation [58,59,60]. Also, behavioral disorders are prevalent among children and adolescents with AD, primarily internalizing profiles like anxiety and depression [31]. Depression, it should be noted, can lead to suicidal ideation. In a large study involving 72,435 children and adolescents, a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms was observed in AD patients when compared with controls (37.0% versus 30.5%) [19].

Suicidal ideation is particularly pronounced in adolescents. Recent studies have shown a higher prevalence of suicidal thoughts (44%) and suicide attempts (36%) in adolescents with AD when compared to those without AD, highlighting the need for targeted attention around this issue [61]. One study noted that 8% of patients reported suicidal thoughts, unrelated to AD severity [31]. A meta-analysis of six studies on adults and children with AD revealed associations between AD and suicidal ideation, planning (8.0%), and attempts (6.1%) [10].

However, the research published to date shows that most conducted studies are cross-sectional or web surveys. Their results and data lack specific facts, including no clarifications of causal relationships between psychological factors/traits or psychiatric disorders and disease (AD) features. Since most of the studies are cross-sectional, it remains unclear whether AD presents a risk factor for coexisting mental disorders and whether mental disorders and AD share the same underlying pathophysiological mechanisms or if mental disorders exacerbate AD. Thus. further studies are needed for conclusive findings.

4.3. Mental Health and Psychological Factors in Relationship to Immune Factors, Neuromediators, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Gut–Skin–Brain Interactions in Atopic Dermatitis

According to the research literature, generally, an association between psychological factors and systemic inflammation exists, including the pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α). For example, various cytokines and inflammatory mediators play a very important role in depression, a common psychiatric comorbidity in AD patients [62]. Certain features (e.g., fatigue) are characteristics of both disorders—somatic (AD) and psychiatric (depression). The activation of the cytokine network could contribute to the development of depressive disorders/symptoms and sick behavior in patients with AD. This is known as the “cytokine hypothesis of depression”, which emphasizes that depressive symptoms/disorders are regulated by central behavioral and neuroendocrine mechanisms involving neuropathways and various cytokines. According to research data, in patients with somatic diseases (e.g., dermatosis) who have not previously suffered from psychiatric disorders, pro-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) may cause true major depressive disorders (coexisting with somatic symptoms).

As is known, there is an association between immune factors/the immune system and the CNS, which involves the influence of neuroendocrine factors on immune cells [62,63]. Thus, it needs to be emphasized that AD, ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are characterized by similar pathomechanisms, which include inflammation, genetics and changes in the microbiome [64,65]. There are several hypotheses that show similarities/associations between AD and neurodevelopmental disorders. In AD, mast-cell-driven vasoactive mediators might increase blood–brain barrier permeability. Consequently, pro-inflammatory cytokines may pass through the blood–brain barrier, causing potential focal brain inflammation and leading to aberrations in synaptic plasticity. This could subsequently be associated with the occurrence of behavioral conditions like ASD and ADHD [65,66,67]. Thus, neuroinflammation is important for AD because it can modify the metabolism of neurotransmitters. Also, genetic factors, like dysregulated DNA methylation, are very important in both AD and ADHD. In addition, in AD patients, changes in the gut microbiome (gut dysbiosis) may disrupt the gut–brain axis, and could thus contribute to brain dysfunction] [68,69,70].

Also very important is the adequate functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) axis and the production of hormones that belong to this axis. An increase in stress-triggered endogenous cortisol production predominantly triggers a Th2 cell response, which contributes to allergic conditions such as AD. As is known, cortisol is a crucial stress hormone that may affect cytokines and their activities. For example, cortisol triggers the release of IL-4, which stimulates plasma cells/B cells to produce IgE. In the long term, the effect is that HPA hyperresponsiveness to stress switches to hyporesponsiveness [62]. It is important to mention that hormones that belong to the HPA axis are also usually produced in skin structures (keratinocates, fibroblasts, etc.) and participate in the inflammation of local sites in the skin (peripheral HPA axis). These hormones are related to Th1 i Th2 cells and their products, which may be related to stress duration. Chronic stress leads to a higher Th1 response associated with chronic corticosteroid secretions and IL-10/IL-18 effects, while acute stress causes a changed Th1 response, involving acute corticosteroid secretion and cytokine IL-12/IL-18 effects.

For psychological traits/psychiatric symptoms accompanying AD, it is also important to consider neuroendocrine-mediated communication in the skin–gut axis, which includes the participation of neuropeptides. Thus, psychiatric disorders and psychological traits like depression and anxiety, along with the stress response, may be related to gut microbiota [70]. According to the literature, neuropeptides can stimulate keratinocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1α, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ, etc.) and thus enhance cell migration and antigen expression, influence the presentation of antigens (through Langerhans cells), induce mast cell degranulation with the release of mediators (like histamine) and trigger blood mononuclears to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, which could trigger inflammatory dermatoses like AD [70,71,72]. Concerning psychological/mental stress in relation to the gut, stress can accelerate excessive intestinal microorganism growth, increase intestinal permeability and destroy the intestinal mucosal immune barrier, as well as stimulate the nervous system to release neuropeptides [70]. Also, gut microbiota secretes different metabolites and some of them are hormone-like compounds (like short-chain fatty acids and cortisol) and neurotransmitters (gamma-amino butyric acid, 5-hydroxytryptamine, dopamine and tryptophan), which can penetrate into the blood, after what they act on distant skin [69,70,73].

Finally, according to “the cytokine hypothesis of depression”, in patients/adolescents with comorbid AD and depressive disorder, pro-inflammatory cytokines could trigger behavioral abnormalities, while stimulation of the immune system may be associated with and/or underline other depressive symptoms [62]. Such an observation could have an implication for AD treatment, which is accompanied by the fact that serotonin agonists and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) improve the clinical picture of AD and decrease pruritus (although the precise mechanisms are not yet known). It is assumed that the anti-pruritic effect of SSRIs is related to certain mechanisms in the CNS. According to current research results, SSRIs (such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, etc.), may improve pruritus, which is a very important therapeutic goal for patients with AD [62].

4.4. Coping with Atopic Dermatitis, Positive Measures/Activities and Related Treatment Possibilities

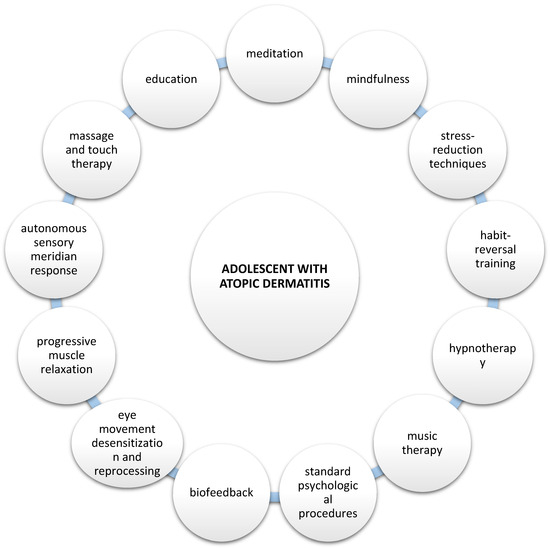

According to current global guidelines, the treatment of patients with AD should consider the psychological aspects, which are an important component of the disease and are included in treatment recommendations. In addition to standard dermatological treatment, various approaches have been attempted to help patients. Several additional methods have proven beneficial in more comprehensive treatments of patients, including meditation and mindfulness, stress-reduction techniques, habit-reversal training, hypnotherapy, music therapy, massage therapy and standard psychological procedures such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Figure 2) [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84].

Figure 2.

Potential psychological approaches to adolescents who suffer from AD.

Continuous psychological observation/follow-up should be conducted, and greater attention should be paid to the psychological changes and/or psychiatric comorbidities, for these patients, especially adolescents with AD [76,77,78]. Medical staff play a crucial role in managing AD patients, including adolescents, through specialized consultations in dermatology clinics. Particular attention should be focused on preventing and promoting mental health in these chronic patients, such as adolescents with AD, recognizing the signs and symptoms of mental disorders, implementing self-help strategies and encouraging healthy lifestyle habits, such as promoting quality sleep and physical activity. In some settings, special programs, including “atopy schools”, are available, which involve education on various aspects of the disease [76,77,78]. Ongoing and continuous support focused on mental health can have a significant impact on adolescents with AD and should be implemented from an early age. The goal of such beneficial intervention is to help adolescents develop skills to cope with the disease and daily stressors, succeed academically, experience satisfaction and feel a sense of community and belonging.

Additionally, an interesting observation from data in the literature indicates that participating in physical activity helps adolescents with AD reduce their psychological stress. Thus, according to other research results, adolescents with AD who are engaged in regular physical activity showed a 30% lower risk of stress compared to those who did not participate [7,79]. This may be because physical activity aids in the reabsorption of cortisol—which is released in significant amounts during a stress response—and helps produce and activate endorphins, which directly affect the brain. Several previous studies have also shown that physical activity contributes to the mental health of patients with allergic diseases such as AD, asthma and allergic rhinitis [80]. However, physical activity may delay the healing of skin lesions in AD patients and accompanying sweat can cause itching, potentially worsening symptoms [81]. Therefore, future studies should provide more information on how to promote physical activity without exacerbating AD symptoms.

Behavioral interventions, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy, seem to be potentially beneficial for patients with AD—with or without a psychiatric comorbidity [82,83,84]. Although most research has included adults with AD, some proposed interventions seem to be suitable for younger age populations, such as adolescents with AD. Cognitive behavioral therapy, either therapist delivered or internet delivered, appears to be efficacious for reducing symptoms of AD as well as accompanying psychiatric symptoms, such as depression or sleep problems [84].

Other beneficial psychological interventions, such as autogenic training and/or biofeedback, could be complementary interventions for adolescents with AD with or without psychiatric comorbidity.

5. Conclusions

Overall, these data indicate that in adolescents with AD, the disease negatively impacts their mental health and disrupts their psychological state, thereby affecting their QoL (e.g., via sleep disorders, issues with emotional status and mental health, as well as problems with social functioning, etc.). These findings highlight the need for a psychological approach and the introduction of intervention programs from an early age, such as mental health assessments and professional supervision following diagnosis. Current research results emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the comprehensive care of patients with AD, which would include mental health professionals. Promoting support for adolescents with AD is particularly important and should be one of the priorities in the prevention of adverse repercussions of AD on mental health, such as the increased risk of suicide attempts. Finally, appropriate and complementary treatment (dermatological and psychological/psychiatric) of patients with AD, significantly improves their QoL as well as treatment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.-M.; methodology, validation, and investigation, L.L.-M., D.B., L.D. and L.Z.; resources and data curation, E.B., L.D. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, D.B., R.T., E.B., L.D. and M.V.; supervision, L.L.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in PubMed or available in other sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AASP | Adult/Adolescent Sensory Profile; |

| AD | atopic dermatitis; |

| ADD/ADHD | attention deficit (hyperactivity) disorder; |

| AHRQ | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; |

| BSA | body surface area; |

| CBCL 6-18 | Child Behavior Checklist 6-18; |

| CI | confidence interval; |

| CIS | Columbia Impairment Scale; |

| CPT-3 | Continuous Performance Test, Third Edition; |

| CRHC | Finnish Health Register for Health Care; |

| EASI | Eczema Area Severity Index; |

| GMDS | Griffiths Mental Development Scales; |

| IQ | intelligence quotient; |

| ISAAC | International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; |

| KYRBS | Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey; |

| KYRBWS-VIII | Eighth Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey; |

| MDI | mental disorder with impairment; |

| MH | mental health; |

| N | number; |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; |

| OR | odds ratio; |

| PP-NRS | Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale; |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrumentation System; |

| QOL | quality of life; |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; |

| SD | standard deviation; |

| ToMMo | Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization; |

| US | United States; |

| WASI | Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; |

| WISC | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; |

| WPPSI | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. |

References

- Laughter, M.R.; Maymone, M.B.C.; Mashayekhi, S.; Arents, B.W.M.; Karimkhani, C.; Langan, S.M.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Flohr, C. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: Lessons from the global burden of disease study 1990–2017. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Howe, W. Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema): Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/atopic-dermatitis-eczema-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis/print (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Fasseeh, A.N.; Elezbawy, B.; Korra, N.; Tannira, M.; Dalle, H.; Aderian, S.; Abaza, S.; Kaló, Z. Burden of atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.P.; Chao, L.X.; Simpson, E.L.; Silverberg, J.I. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, F.; Santi, F.; Cioppa, V.; Orsini, C.; Lazzeri, L.; Cartocci, A.; Rubegni, P. Meeting the needs of patients with atopic dermatitis: A multidisciplinary approach. Dermatitis 2022, 33, S141–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, M.; Di Mauro, G.; Rotunno, R.; Giancristoforo, S.; De Ranieri, C.; Carlevaris, C.M.; Verga, M.C.; Dello Iacono, I. Pruritus in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: A multidisciplinary approach-summary document from an Italian expert group. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Prochnow, T.; Chang, J.; Kim, S.J. Health-related behaviors and psychological status of adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis: The 2019 Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieber, T.; Paller, A.S.; Kabashima, K.; Feely, M.; Rueda, M.J.; Ross Terres, J.A.; Wollenberg, A. Atopic dermatitis: Pathomechanisms and lessons learned from novel systemic therapeutic options. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1432–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.S.; Oh, Y.; Rand, K.L.; Wu, W.; Cyders, M.A.; Kroenke, K.; Stewart, J.C. Measurement invariance of the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screener in U.S. adults across sex, race/ethnicity, and education level: NHANES 2005–2016. Depress Anxiety 2019, 36, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønnstad, A.T.; Halling-Overgaard, A.S.; Hamann, C.R.; Skov, L.; Egeberg, A.; Thyssen, J.P. Association of atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, M.J.; Essex, M.J.; Paletz, E.M.; Vanness, E.R.; Infante, M.; Rogers, G.M.; Gern, J.E. Depression, anxiety, and dermatologic quality of life in adolescents with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.; Dreher, M.; Weeß, H.G.; Staubach, P. Sleep disturbance in patients with urticaria and atopic dermatitis: An underestimated burden. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.J.; Uddin, M.J.; Saha, S.K.; Darmstadt, G.L. Prevalence and psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in Bangladeshi children and families. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marron, S.E.; Cebrian-Rodriguez, J.; Alcalde-Herrero, V.M.; Garcia-Latasa de Aranibar, F.J.; Tomas-Aragones, L. Psychosocial impact of atopic dermatitis in adults: A qualitative study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 111, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Ferček, I.; Pondeljak, N.; Lazić-Mosler, E.; Gašić, A. Atopic dermatitis severity, patient perception of the disease, and personality characteristics: How are they related to quality of life? Life 2021, 11, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghmaie, P.; Koudelka, C.W.; Simpson, E.L. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.M.; Cho, J.J.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. The relationship between suicidal behaviors and atopic dermatitis in Korean adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Haimes, E.M.; Diaz, K.I.; Haimes, B.A.; Ehrenreich-May, J. Anxiety and atopic disease: Comorbidity in a youth mental health setting. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, A. Association of atopic dermatitis with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Korea: The 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniyoshi, Y.; Kikuya, M.; Miyashita, M.; Yamanaka, C.; Ishikuro, M.; Obara, T.; Metoki, H.; Nakaya, N.; Nagami, F.; Tomita, H.; et al. Severity of eczema and mental health problems in Japanese schoolchildren: The ToMMo Child Health Study. Allergol. Int. 2018, 67, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.D.; Sol, I.S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Jung, Y.C.; Sohn, M.H.; Kim, K.W. Korean youth with comorbid allergic disease and obesity show heightened psychological distress. J. Pediatr. 2019, 206, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.Y.; Smith, B.; Silverberg, J.I. Atopic dermatitis and hospitalization for mental health disorders in the United States. Dermatitis 2019, 30, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Takeshita, J.; Shin, D.B.; Gelfand, J.M. Mental health impairment among children with atopic dermatitis: A United States population-based cross-sectional study of the 2013–2017 National Health Interview Survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyung, Y.; Choi, M.H.; Jeon, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, S.H. Association of atopic dermatitis with suicide risk among 788,411 adolescents: A Korean cross-sectional study. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 125, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyung, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, S.H. Health-related behaviors and mental health states of South Korean adolescents with atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.; Silverberg, J.I. Predictors and age-dependent pattern of psychologic problems in childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2021, 38, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W.; Vogel, M.; Prenzel, F.; Genuneit, J.; Jurkutat, A.; Hilbert, C.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Atopic diseases in children and adolescents are associated with behavioural difficulties. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, A.B.; Cheng, B.T.; Tilley, C.C.; Begolka, W.S.; Carle, A.C.; Forrest, C.B.; Zee, P.C.; Paller, A.S.; Griffith, J.W. Sleep disturbance in school-aged children with atopic dermatitis: Prevalence and severity in a cross-sectional sample. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 3120–3129.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.; Wan, J.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Ramirez, F.D.; Lee, Y.; McCulloch, C.E.; Langan, S.M.; Abuabara, K. Association of atopic dermatitis and mental health outcomes across childhood: A longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.T.; Fishbein, A.B.; Silverberg, J.I. Mental health symptoms and functional impairment in children with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis 2021, 32, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, M.M.; Vaz, F.P.C.; Roque, R.M.S.D.A.; Mallozi, M.C.; Solé, D.; Wandalsen, G.F. Behavioral disorders in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockler, P.G.; Hooper, S.R.; Abuabara, K.; Ma, E.Z.; Radtke, S.; Bao, A.; Kim, E.; Musci, R.J.; Kartawira, K.; Wan, J. Atopic dermatitis, cognitive function and psychiatric comorbidities across early childhood and adolescence in a population-based UK birth cohort. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 190, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.C.; Wang, S.H.; Wang, C.X.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.H.; Li, X. Epidemiology of mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis: An analysis of global trends from 1998 to 2022. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paller, A.S.; Rangel, S.M.; Chamlin, S.L.; Hajek, A.; Phan, S.; Hogeling, M.; Castelo-Soccio, L.; Lara-Corrales, I.; Arkin, L.; Lawley, L.P.; et al. Pediatric dermatology research alliance. stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Barnum, S.; Jaeger, J.; Shao, L.; Ozturk, Z.E.; Korotzer, A. Attentiveness and mental health in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis without ADHD. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco Sequeiros, A.; Sinikumpu, S.P.; Jokelainen, J.; Huilaja, L. Psychiatric comorbidities of childhood-onset atopic dermatitis in relation to eczema severity: A register-based study among 28,000 subjects in Finland. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2024, 104, 40790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekzad, F.; Arbabi, M.; Mohtasham, N.; Toosi, P.; Jaberian, M.; Mohajer, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Roodsari, M.R.; Nasiri, S. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C. The factors affecting the life satisfaction of adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Stud. Korean Youth 2015, 26, 111–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schut, C.; Weik, U.; Tews, N.; Gieler, U.; Deinzer, R.; Kupfer, J. Psychophysiological effects of stress management in patients with atopic dermatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2013, 93, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, F.D.; Chen, S.; Langan, S.M.; Prather, A.A.; McCulloch, C.E.; Kidd, S.A.; Cabana, M.D.; Chren, M.M.; Abuabara, K. Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e190025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Garg, N.K.; Paller, A.S.; Fishbein, A.B.; Zee, P.C. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: A US population-based study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešlić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Vrtarić, A.; Bešlić, A.; Škrinjar, I.; Hanžek, M.; Crnković, D.; Artuković, M. Melatonin in dermatologic allergic diseases and other skin conditions: Current trends and reports. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.R.; Radtke, S.; Wan, J. Symptoms of cognitive impairment among children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Muzzolon, M.; Canato, M.; Muzzolon, S.B.; Lima, M.N.; Carvalho, V.O. Dermatite atopica e transtornos mentais: Associacao em relacao a gravidade da doenca. Rev. Bras. Neurol. Psiquiatr. 2021, 25, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.; Garcia, M.J.; Freitas, A.; Silva, H. Impact of atopic dermatitis on the mental health of adolescents—Literature review. Med. Sci. Forum. 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Schonmann, Y.; Mansfield, K.E.; Hayes, J.F.; Abuabara, K.; Roberts, A.; Smeeth, L.; Langan, S.M. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: A population-based cohort study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kage, P.; Simon, J.; Treudler, R. Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidities. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2020, 18, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, S.; Jabeen, M.; Singh, S.; Verma, R. Gender differences in depression and anxiety among atopic dermatitis patients. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.A.; Park, E.C.; Lee, M.; Yoo, K.B.; Park, S. Does stress increase the risk of atopic dermatitis in adolescents? results of the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS-VI). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, M.; Joubert, G.; Ehrlich, R.; Nelson, H.; Poyser, M.A.; Puterman, A.; Weinberg, E.G. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema symptoms in young adolescents. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2004, 15, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Su, J. Association between emotional distress and atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, S0022-202X(25)00365-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, K.B.; Obradović, J.; Long, J.D.; Masten, A.S. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Dev. 2016, 79, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.; Blaiss, M.S. The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018, 39, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuberbier, T.; Orlow, S.J.; Paller, A.S.; Taïeb, A.; Allen, R.; Hernanz-Hermosa, J.M.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Cox, M.; Langeraar, J.; Simon, J.C. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBovidge, J.S.; Schneider, L.C. Depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis: Recognizing and addressing mental health burden. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes Neto, P.T.; Weber, M.B.; Fortes, S.D.; Cestari, T.F.; Escobar, G.F.; Mazotti, N.; Barzenski, B.; da Silva, L.T.; Soirefmann, M.; Pratti, C. Evaluation of emotional and behavioral symptoms in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Rev. Psiquiatr. Rio Gd. Sul. 2005, 27, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Narayan, R.V.; Mohta, A.; Deoghare, S. Adolescent atopic dermatitis: An overlooked challenge. Ind. J. Paediatr. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, L.; Cices, A.; Fishbein, A.B.; Paller, A.S. Neurocognitive function in moderate-severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: A case-control study. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.J.; Chen, A.W.; Luo, X.Y.; Wang, H. Increased attention deficit/hyperactivity and oppositional defiance symptoms of 6-12 years old Chinese children with atopic dermatitis. Medicine 2020, 99, e20801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.Y.; Nili, A.; Blackwell, C.K.; Ogbuefi, N.; Cummings, P.; Lai, J.S.; Griffith, J.W.; Paller, A.S.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Fishbein, A.B. Parent report of sleep health and attention regulation in a cross-sectional study of infants and preschool-aged children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2022, 39, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, J.K.; Wu, K.K.; Bui, T.L.; Armstrong, A.W. Association between atopic dermatitis and suicidality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L. Psychoneuroimmune aspects of atopic dermatitis. In PsychoNeuroImmunology; Rezaei, N., Yazdanpanah, N., Eds.; Integrated Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, I.; Ilie, M.A.; Draghici, C.; Voiculescu, V.M.; Căruntu, C.; Boda, D.; Zurac, S. The impact of lifestyle factors on evolution of atopic dermatitis: An alternative approach. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Lu, J.W.; Wang, J.H.; Loh, C.H.; Chen, T.L. Associations of atopic dermatitis with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatology 2024, 240, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, A.; Su, J.C. The psychology of atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Patel, A.B.; Doyle, R. Atopic diseases and inflammation of the brain in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.L.; Stiernborg, M.; Skott, E.; Söderström, Ĺ.; Giacobini, M.; Lavebratt, C. Proinflammatory mediators and their associations with medication and comorbid traits in children and adults with ADHD. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 41, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paller, A.S.; Kong, H.H.; Seed, P.; Naik, S.; Scharschmidt, T.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Luger, T.; Irvine, A.D. The microbiome in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmajaya, A.C.; Lusida, M.I.; Soetjipto; Setiawati, Y. Systematic review of gut microbiota and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Zhang, X.E.; Feng, H.; Yan, B.; Bai, Y.; Liu, S.; He, Y. Microbial perspective on the skin-gut axis and atopic dermatitis. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20220782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, R.A.; Handjiski, B.; Blois, S.M.; Hagen, E.; Paus, R.; Arck, P.C. Stress-induced neurogenic inflammation in murine skin skews dendritic cells towards maturation and migration: Key role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1/leukocyte function-associated antigen interactions. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 173, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.C.; Fantozzi, R. The role of histamine in neurogenic inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Stilling, R.M.; Kennedy, P.J.; Stanton, C.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Minireview: Gut microbiota: The neglected endocrine organ. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, S.; Watanabe, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Imai, T.; Aida, R.; Germer, C.; Tamagawa-Mineoka, R.; Shimizu, R.; Hickman, S.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Efficacy of integrated online mindfulness and self-compassion training for adults with atopic dermatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oska, C.; Nakamura, M. Alternative psychotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of eczema. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2721–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, S.C.; LeBovidge, J.S.; Timmons, K.G.; Schneider, L.C. A Review of multidisciplinary interventions in atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 1156–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Barac, E.; Tomašević, R.; Parać, E.; Zanze, L.; Ljevar, A.; Dolački, L.; Štrajtenberger, M. Atopic dermatitis-related problems in daily life, goals of therapy and deciding factors for systemic therapy: A review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Potočnjak, I.; Cindrić, T.; Ilić, I.; Lovrić, I.; Skalicki, L.; Bešlić, I.; Pondeljak, N. Atopic dermatitis: Disease features, therapeutic options, and a multidisciplinary approach. Life 2023, 13, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Koo, J.; Lim, S.K. Associations between stress and physical activity in Korean adolescents with atopic dermatitis based on the 2018–2019 Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dougherty, M.; Hearst, M.O.; Syed, M.; Kurzer, M.S.; Schmitz, K.H. Life events, perceived stress and depressive symptoms in a physical activity intervention with young adult women. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murota, H.; Yamaga, K.; Ono, E.; Murayama, N.; Yokozeki, H.; Katayama, I. Why does sweat lead to the development of itch in atopic dermatitis? Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D.; Ljótsson, B.; Lönndahl, L.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E.; Bradley, M.; Lindefors, N.; Kraepelien, M. A Digital self-help intervention for atopic dermatitis: Analysis of secondary outcomes from a feasibility study. JMIR Dermatol. 2023, 6, e42360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisapogu, A.; Ojinna, B.T.; Choday, S.; Kampa, P.; Ravi, N.; Sherpa, M.L.; Agrawal, H.; Alfonso, M. A Molecular basis approach of eczema and its link to depression and related neuropsychiatric outcomes: A review. Cureus 2022, 14, e32639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman-Lagerlöf, E.; Fust, J.; Axelsson, E.; Bonnert, M.; Lalouni, M.; Molander, O.; Agrell, P.; Bergman, A.; Lindefors, N.; Bradley, M. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for atopic dermatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).