Abstract

Inappropriate use of antibiotics can stimulate antimicrobial resistance, since bacteria are capable of circumventing pharmacological action through various resistance mechanisms. Recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in the use of antimicrobials. This is an analytical, quantitative, and retrospective study on bacterial resistance and mortality in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients from 2017 to 2022. This study analyzed sociodemographic aspects, clinical, and laboratory parameters in patients admitted to the ICU. A total of 221 medical records of patients with multidrug-resistant bacteria in the ICU were included, with an outcome of 95 discharges (42.98%) and 126 deaths (53.01%). An increase in the prevalence of bacterial resistance in the ICU was identified during the Pandemic period, when compared to the Pre-Pandemic period. It was identified that the increase in bacterial resistance of some pathogens was associated with death. It was also observed that age was a factor for an increased risk of mortality in the ICU, no matter the sex of the patient. Importance of careful analysis in the use of antimicrobials, as well as in the care of ICU patients and in the surveillance of bacterial infections by health professionals.

1. Introduction

Bacterial infections have long been a global concern and are present across diverse healthcare settings, contributing to imbalances in the normal microbiota and in host defense mechanisms. Various microorganisms are responsible for these infections and may develop mechanisms that inhibit the action of available antibiotics, leading to a growing burden of bacterial resistance and increased mortality [1].

Antimicrobial resistance refers to the ability of microorganisms to withstand the inhibitory and bactericidal effects of one or more classes of antimicrobial agents. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon, including the bacterial population’s capacity to adapt under selective pressure, as well as clinical conditions directly associated with healthcare environments and therapeutic procedures [2]. According to Silva and Nogueira (2021) [3], the indiscriminate use of medications, regardless of the presence of infectious agents, also plays a major role, representing an imminent public health risk due to bacterial adaptability and the development of resistance mechanisms. This scenario can lead to infections caused by pan-resistant bacteria and result in increased hospital admissions, prolonged length of stay, and higher mortality.

The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks antimicrobial resistance among the ten leading global threats to health [4]. In hospital settings, this resistance has become one of the greatest challenges for healthcare professionals, representing a serious public health issue due to its substantial economic and social impact [5]. Given the severity of these infections and their repercussions on patient outcomes, there has been continuous growth in guidelines and interventions aimed at optimizing antimicrobial protocols in Intensive Care Units (ICUs). These measures seek to ensure appropriate antibiotic use, reduce excessive prescribing, and strengthen infection prevention and control strategies [4].

Within hospitals, ICUs are highly specialized and complex environments designed to care for critically ill patients who require intensive monitoring and advanced medical support. Frequent invasive procedures, the use of specific medications, and the high circulation of healthcare professionals increase the risk of cross-contamination and exposure to circulating bacterial strains. This scenario demands robust measures to mitigate pathogen transmission and strategies to minimize the emergence and spread of bacterial resistance between ICU beds. According to the Brazilian Society for Microbiology, approximately 700,000 deaths occur annually due to infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, with projections suggesting this number may reach 10 million per year by 2050 [4].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the absence of well-defined protocols, plus limited knowledge about effective treatments in the early stages, contributed to the progression of many patients to severe respiratory infections. Challenges in selecting appropriate therapies led to a significant increase in the use of multiple medications to alleviate viral symptoms. Consequently, practices lacking adequate scientific basis became widespread, promoting inappropriate antimicrobial use and amplifying the risk of resistance development [6]. Beyond COVID-specific protocols, clinical data indicate that 30% of COVID-19 patients acquired secondary infections due to prolonged mechanical ventilation, extended ICU stays, and complex antibiotic regimens—factors that fostered increased antimicrobial utilization in hospital environments [7].

Golli et al. (2025) [8] reported a statistically significant rise in antibiotic resistance rates (p < 0.05) and in the proportion of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative strains isolated from blood cultures in the post-COVID period. These findings reflect the excessive and often inappropriate use of antibiotics during the pandemic in attempts to prevent complications associated with SARS-CoV-2, ultimately favoring the selection and spread of multidrug-resistant strains. Such evidence reinforces the urgency of adopting more judicious therapeutic practices, aligned with established rational prescribing protocols.

In this regard, Vicentini et al. (2024) [9] emphasize the importance of robust, well-structured, and coordinated antimicrobial stewardship programs at regional and hospital levels to mitigate the impacts of indiscriminate antibiotic use on patient outcomes. Complementarily, Lakbar et al. (2020) [10] found that antibiotic de-escalation rates were significantly lower among COVID-19 patients compared to a pre-pandemic control group (27.6% vs. 52.2%; p < 0.001), without an associated increase in hospital or ICU mortality. Similarly, Vidaur et al. (2024) [11] showed that the implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program during the pandemic contributed to reducing the prevalence of potentially resistant pathogens. They also indicated that the severity of clinical presentation at admission was a more relevant risk factor for bacterial co-infection when compared to the irregular use of antibiotics.

In this context, bacterial resistance directly affects patient recovery and is particularly critical in ICUs, where it may be associated with increased mortality risk. Thus, assessing the impact of inappropriate antimicrobial use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and its association with bacterial resistance in ICUs, is essential. Strengthening surveillance of bacterial resistance, especially in intensive care settings, can improve clinical processes, enhance patient management, and inform health policies aimed at reducing adverse outcomes in critical care environments [12].

Accordingly, we sought to assess and compare the prevalence of bacterial resistance reported in the ICU before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as its association with clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This analytical, quantitative, and retrospective study evaluated the prevalence of bacterial resistance reported to the Hospital Infection Control Service (HICS) among patients admitted to the Adult General ICU and the COVID-19 ICU, as well as their clinical outcomes, from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2022—a period (2022) that was recognized by the WHO as the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were obtained from medical records of a medium-sized, high-complexity hospital located in the northwestern region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. The hospital has 210 beds, including 10 Adult ICU beds, and which, during the pandemic (2020–2021), expanded its capacity to 20 ICU beds dedicated exclusively to patients with COVID-19. The study was conducted in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the Brazilian National Health Council and approved by the UNIJUÍ Ethics Committee (CAAE: 69416623.3.0000.5350; approval no. 6.101.715; 2023).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: all medical records of patients with documented bacterial resistance reported to HICS, aged ≥ 18 years, of both sexes, with complete clinical and laboratory data, and containing ICU laboratory culture tests, bacterial identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Exclusion criteria: medical records of patients with bacterial infection but without resistance reported to HICS; incomplete records; records outside the study period; or records lacking culture, bacterial identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Medical records of patients older than 95 years were excluded, as well.

After patient selection, individuals were stratified into discharge and death groups over the study period.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Data Collection and Definitions

Data were obtained from the Hospital Infection Control Service (HICS). Clinical and laboratory parameters of patients with cultures showing bacterial growth were evaluated. Using HICS reports, medical record numbers were identified and subsequently used to collect sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data.

- -

- Sociodemographic aspects: age and sex. Age was recorded as a continuous numeric variable in completed years.

- -

- Clinical parameters: presence of pre-existing diseases (Diabetes Mellitus; cardiovascular diseases; kidney diseases; respiratory diseases; systemic arterial hypertension; and malignant neoplasms) and health-related habits. ICU length of stay was recorded as the total number of days each patient remained in an ICU bed, measured from admission until discharge or transfer to another hospital unit.

- -

- Laboratory parameters: description of sites and/or types of specimens collected, including oral swab; rectal swab; urine; tracheal aspirate; bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL); sputum; general cultures; and blood culture. For the culture category, the following materials were included: abdominal abscess; abscess; stool; gangrene; ascitic fluid; bile fluid; abdominal cavity fluid; cerebrospinal fluid; catheter tip; surgical wound secretion; abdominal wall secretion; purulent abdominal secretion; peritoneal secretion; endometrial fragment; and subcutaneous tissue.

2.3.2. Bacterial Strains Included in the Study and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Bacterial isolation and identification included the following: Acinetobacter baumannii; Acinetobacter iwoffi; Burkholderia cepacia; Clostridium difficile; Enterobacter aerogenes; Enterobacter aerogenes (CESP); Enterobacter aerogenes (ESBL); Enterobacter aerogenes (KPC); Enterobacter cloacae (CESP); Enterococcus sp.; Escherichia coli; Escherichia coli (ESBL); Escherichia coli (KPC); Klebsiella oxytoca; Klebsiella ozaenae (ESBL); Klebsiella aerogenes (ESBL); Klebsiella aerogenes (KPC); Klebsiella pneumoniae; Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL); Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPC); Nontuberculous mycobacteria; Morganella morganii (CESP); Morganella morganii; Proteus mirabilis; Proteus mirabilis (ESBL); Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Serratia marcescens (CESP); Staphylococcus sp.; Staphylococcus aureus; coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (MRSA); Streptococcus sp.; group B Streptococcus; beta-hemolytic Streptococcus; Streptococcus pneumoniae; group A Streptococcus; and viridans group Streptococci.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

After reviewing each medical record and confirming eligibility, data were organized in a spreadsheet, stratifying patients by outcome (hospital discharge or in-hospital death), year, and ICU type. Based on this stratification by year and ICU type, summary tables were prepared to illustrate sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics, highlighting key information and providing an overview of the results.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and frequencies, and compared using Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney test after assessing distribution normality. Categorical variables were expressed as counts/totals and frequencies, and compared using Fisher’s exact test. For intergroup comparisons of means, Student’s t test was applied for parametric analyses, and the Mann–Whitney test for nonparametric analyses. Frequency comparisons were performed using Fisher’s exact test. Analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism®10. Results were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

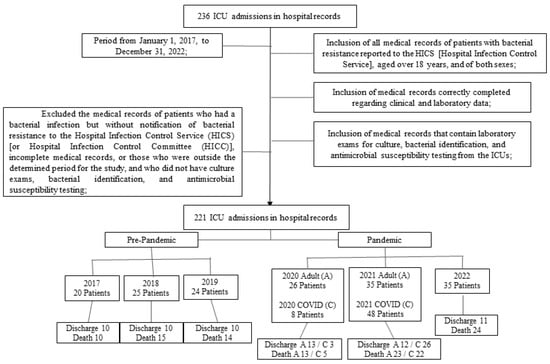

In total, 236 medical records of patients admitted to ICUs were collected between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022. After verification and review, 221 records were included in the study; of these, 165 were from the Adult ICU and 56 from the COVID ICU. When stratifying patients, the final total was 221 patients, with outcomes as follows: 95 discharges (42.98%) and 126 deaths (53.01%). Based on these groups, results were organized into clinical, sociodemographic, and laboratory parameters, according to site of infection, etiologic agents, and antimicrobial resistance profile, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population.

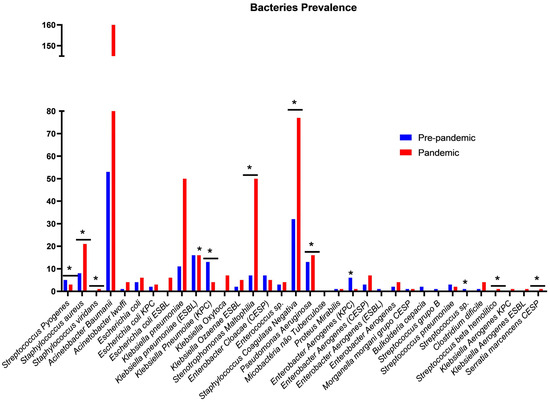

In Figure 2, substantial changes in the prevalence of different bacteria can be observed between the pre-pandemic (blue) and pandemic (red) periods. A marked increase in several microorganisms is evident during the pandemic period, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL, KPC, and CESP groups), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp., suggesting that the pandemic influenced the broader dissemination of multidrug-resistant strains. This pattern may be associated with increased antimicrobial use, prolonged ICU hospitalizations, healthcare system overload, and the intensified use of invasive devices in critically ill patients.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pre-pandemic and pandemic periods in ICUs. Ijuí, RS, Brazil, 2024. Legend: Assessment of the prevalence of resistance to microorganisms during the study period. Chi-square test performed using the GraphPad Prism®; * standardized residual < −2 or >2, indicating a deviation from the expected frequency.

In contrast, pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, Enterococcus faecalis, and certain species of Streptococcus showed stability or reduction over the same period, indicating a heterogeneous impact of the pandemic across bacterial species.

Statistically significant differences in prevalence were identified between the periods analyzed, particularly among clinically relevant microorganisms frequently associated with ICU settings and increased mortality. Overall, the findings highlight marked shifts in the microbiological profile between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, characterized by an increase in multidrug-resistant bacteria and changes in the distribution of pathogens critical to patient safety.

3.1. Clinical and Sociodemographic Parameters

Data on period/year, sex, age, outcome, and ICU type are presented in Table 1. Over the entire study period, patients with a death outcome were older (64.56 ± 13.26 years) than those who were discharged (54.47 ± 15.06; p = 0.001). Similarly, in year-by-year assessments in the Adult ICUs, age contributed to the death outcome in 2018, 2020, and 2021.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU patients stratified by age, sex, and outcome group (Discharge and Death). Ijuí, RS, Brazil, 2024. (n = 221).

When analyzing outcome stratified by sex, older age was associated with death (both in males and females), in the analysis of the total study period (p = 0.001) and in the years 2018 (p = 0.045), 2020 (Adult ICU, p = 0.020), 2021 (Adult ICU, p = 0.014), and 2022 (p = 0.041). When analyzing sex alone, we found no association with ICU mortality over the entire study, except in the Adult ICU in 2020, where an association was observed (p = 0.047).

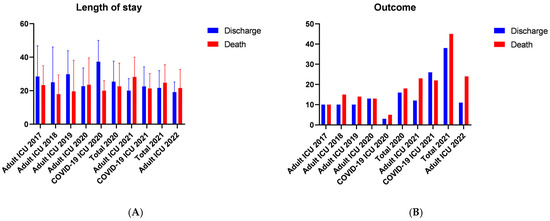

Regarding length of stay (Table 2 and Figure 3), over the total study period there were no significant differences in length of stay between patients who were discharged compared with those who died (p = 0.303). However, when analyzing by year and ICU type, patients who died had a shorter length of stay in 2019 (p = 0.012) and in the COVID ICU in 2020 (p = 0.017). Conversely, in 2021 in the Adult ICU, patients who died had a longer length of stay (p = 0.038) compared with those who were discharged.

Table 2.

Length of stay (days) and outcomes (discharge and death), stratified by outcome. Ijuí, RS, Brazil, 2024. (n = 221).

Figure 3.

Temporal Analysis of Length of Stay and Mortality in the ICU. Ijuí, RS, Brazil, 2024. (A) the mean ICU length of stay comparing patients who were discharged with those who died, and (B) the corresponding outcomes in the same cohorts (discharge versus death). Legend: Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as percentage (number), using Fisher’s exact test. For between-group analyses (Discharge vs. Death), Student’s t test was used (length of stay × mortality), p < 0.05. Graphical representation of the results shown in Table 2.

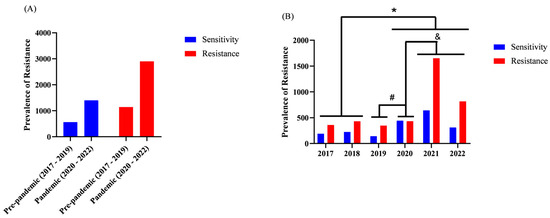

3.2. Laboratory Parameters

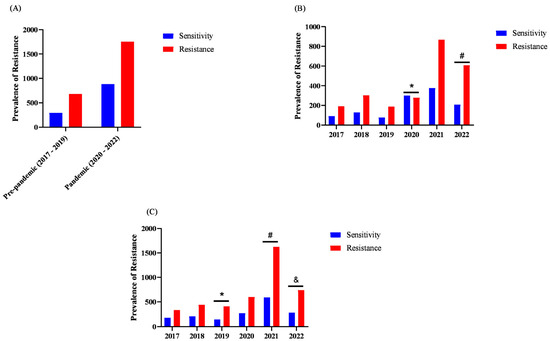

In the analysis of antimicrobial resistance profiles in the ICU, we found no significant differences in the prevalence of resistance (p = 0.8069) between the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) and the Pandemic period (2020–2022). The prevalence of bacterial resistance in the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) was 67.14%, whereas in the Pandemic period (2020–2022) it was 67.47%. Similarly, antimicrobial susceptibility prevalence was 32.86% in the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) and 32.53% in the Pandemic period (2020–2022), as shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Total resistance and susceptibility over time in the ICUs and annual prevalence of bacterial resistance. Ijuí, RS, Brazil, 2024. (n = 221). Legend: The y-axis represents the absolute number of resistant bacterial isolates identified within each analyzed category. Counts may exceed the total number of participants because a single patient may contribute multiple clinical isolates, resulting in more than one resistance record. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism®. (A) Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the prevalence of resistance before and after the pandemic period (Resistant vs. Susceptible). (B) Fisher’s exact test was used to compare prevalence across the different years analyzed in the study. * p < 0.05 between 2017, 2018 vs. 2020, 2021, 2022; # p < 0.05 between 2019 vs. 2020; & p < 0.05 between 2020 vs. 2021, 2022.

Although no significant difference was observed in the period-based analysis (Pre-pandemic vs. Pandemic), in the year-by-year analysis we identified that in 2020, 2021, and 2022 the prevalence of bacterial resistance was higher than in 2017 and 2018. In addition, in 2020 both resistance and susceptibility prevalence were higher than in 2019, as depicted in Figure 4B.

When assessing the association between the prevalence of bacterial resistance and mortality, we did not find an association between resistance and ICU mortality (p = 0.0602), as shown in Figure 5A. In the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019), the prevalence of bacterial resistance among patients with death outcome was 69.85%, whereas in the Pandemic period it was 66.49%. Likewise, susceptibility prevalence in the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) was 30.15%, whereas in the Pandemic period it was 33.51%.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of bacterial resistance among deaths over time in ICUs (n = 221). Legend: The y-axis represents the absolute number of resistant bacterial isolates in each analyzed category. This value may exceed the total number of participants because a single patient may contribute multiple clinical isolates, leading to more than one resistance record. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism®. (A) Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the prevalence before and after the pandemic period (Resistant vs. Susceptible). (B) Fisher’s exact test was used to compare prevalence across the different years analyzed in the study, * p < 0.05 between 2020 vs. 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022; # p < 0.05 between 2022 vs. 2021, 2017. (C) Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze antibiotic resistance across the different years included in the study, * p < 0.05 between 2019 vs. 2017, 2018; # p < 0.05 between 2021 vs. 2018, 2020; & p < 0.05 between 2022 vs. 2017.

When evaluating the prevalence of bacterial resistance by year only among patients who died (Figure 5B), we found that in 2022 there was a higher prevalence of bacterial resistance among death outcomes. Conversely, in 2020 we observed a higher prevalence of susceptibility among patients who died. Furthermore, we compared years regarding the prevalence of bacterial resistance by antimicrobial (Figure 5C). In this analysis, we identified that the prevalence of resistance by antimicrobial in 2019 was higher than in 2017 and 2018. In 2021, the prevalence of resistance by antimicrobial was higher than in 2017, 2018, and 2020. In 2022, the prevalence of resistance was higher than in 2017.

Among the main limitations of this study, the retrospective design stands out, as it is subject to minor inconsistencies inherent to institutional records. Conducting the study in a single hospital may limit the generalizability of the findings. The reduced sample size in certain stratifications (by year, ICU type, or microorganism) may also constrain the analytical power. The absence of detailed data on individual antimicrobial use prevents direct assessment of its relationship with resistance patterns. Potential biases related to clinical severity, which was not uniformly characterized, should also be considered. Furthermore, structural and operational changes during the pandemic may have influenced the observed infection and resistance profiles, affecting the interpretation of the results.

4. Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has intensified globally in recent years. Now, it represents one of the greatest challenges to medical care, particularly in critical care environments. Current evidence shows that, in 2021, an estimated 4.71 million deaths were associated with AMR—1.14 million of them directly attributable—largely driven by increasing carbapenem resistance and a higher burden among elderly patients [13]. The inappropriate and excessive use of antimicrobials across clinical, community, and agricultural settings has accelerated the selection and spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii, which remain highly prevalent in surveillance systems worldwide [14].

In response, the WHO recommends strengthened antimicrobial stewardship, enhanced infection prevention strategies, and robust global surveillance systems, including GLASS. During pandemic periods such as COVID-19, the rapid escalation of empirical antimicrobial prescribing, prolonged ICU stays, and overwhelmed healthcare systems further intensified selective pressure, contributing to the emergence of resistant strains and worsening clinical outcomes [13]. Therefore, integrating prevention, rapid diagnostic strategies, and rational antimicrobial use becomes essential to mitigate the impact of AMR, especially during public health emergencies that exacerbate the risk of resistant infections in ICUs.

In our study, a total of 221 ICU patients were evaluated, of whom 42.98% were discharged and 53.01% died. These findings are consistent with Pontes et al. (2021) [15], who, over a 128-day pandemic period, reported 86 deaths, resulting in a mortality rate of 12.8%. Our results encompass all ICUs and a broader timeframe, which explains a higher overall death rate. When assessing a longer pandemic interval, patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, including various variants, often required mechanical ventilation, vascular access, urinary catheters, and other invasive devices to support clinical management. The high number and variety of interventions, though essential for treatment, frequently increase the risk of bacterial infections, whose resistance patterns confer greater mortality risk [16].

Regarding sociodemographic aspects, we observed a predominance of male admissions (59.27%) during the study period, which aligns with other research on ICU patient profiles in the pandemic, such as Sodré et al. (2023), Ranzani et al. (2021), and Peixoto et al. (2022) [17,18,19], who reported male predominance of 95%, 56%, and 52.16%, respectively. Conversely, Silva et al. (2023) and Rocha et al. (2023) [20,21] found a predominance of females. Although we did not identify an association between sex and mortality across the entire study period, except in the Adult ICU in 2020 (p = 0.047), it is frequently noted that men engage less in preventive healthcare, including routine examinations, thereby neglecting the control of certain risk conditions [22]. Men’s low and delayed adherence to primary care services, combined with scarce health policies and limited specialization in men’s health in urgent care units, poses challenges for reframing male healthcare stereotypes [23].

Unlike sex, age showed a strong association with mortality, as patients who died were older. Kruger (2021) [24] demonstrated a significant association between advanced age and higher mortality, corroborating our results. Castro et al. (2021) [25] reported that the most frequent ICU admission occurs among those aged 71–80 years, and that 60% of ICU beds are occupied by patients over 65, which significantly contributes to death outcomes. Moreover, when stratifying outcomes by sex, both older men and women presented higher mortality risk across all study periods, indicating that age was an independent risk factor.

Our findings showed that age contributed to death both overall and in the year-by-year analyses (2018, 2020, and 2021 in Adult ICUs). Advanced age also increases the risk of severe infections, conferring greater vulnerability to infections, complications, and severe clinical presentations, often necessitating hospitalization and intensive care. Poor baseline health status diminishes host defenses, increasing susceptibility to pathogenic microorganisms, favoring infectious processes, and elevating morbidity and mortality [26]. Santos et al. (2021) [27] analyzed ICU COVID-19 mortality and found higher death incidence among individuals over 65 years with comorbidities.

With respect to length of stay, we observed that patients with shorter ICU stays in 2019 and in the COVID ICU in 2020 had higher numbers of deaths. ICU length of stay can vary substantially by ICU type and patient clinical profile. In more severe cases, ICU stay may be shorter due to rapid deterioration. In this context, Figueiredo et al. (2020) [26] reported that the interval between admission and death among older adults ranged from 7 to 9 days, supporting the notion that greater age and severity are associated with higher risk of death and shorter stays. Similarly, Liu et al. (2020) [28] found fewer days of hospitalization among older patients (70 years).

Kilinc (2025) [29] reports that multidrug-resistant pathogens, particularly Acinetobacter baumannii, MRSA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, are strongly associated with prolonged ICU stays and higher mortality rates. In the study, patients with infections caused by multidrug-resistant microorganisms had significantly longer ICU lengths of stay (p < 0.05), as well as an increased risk of death. Infections due to A. baumannii showed the strongest association with mortality (HR: 4.6; p < 0.001), followed by MRSA (HR: 3.5; p = 0.005) and P. aeruginosa (HR: 2.8; p = 0.01).

Conversely, prolonged ICU stays increase the risk of complications and infections, which predispose to death but with longer hospitalization times. Prolonged ICU stay can create a vicious cycle: case severity requires invasive procedures and antimicrobial use, which in turn raises the risk of infections by multidrug-resistant bacteria, further prolonging hospitalization and worsening clinical status. Patient heterogeneity, comorbidities and immunosuppression directly influence infection risk. Additionally, ICU type, with differing procedural intensity and patient density, contributes to variability in rates [30,31].

Studies conducted in hospital populations demonstrate that patients who develop secondary infections exhibit substantially prolonged ICU stays, frequently ranging from 15 to 20 days. This is associated with an increased risk of mortality, particularly when multidrug-resistant pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are involved [32,33]. Moreover, investigations carried out during the pandemic indicate that the average ICU length of stay among patients with COVID-19 who develop secondary bacterial infections may exceed 17 days, resulting in greater cumulative antimicrobial exposure and a higher incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia [34,35].

Analyzing ICU antimicrobial resistance profiles, we found no increase in overall resistance prevalence in the Pre-pandemic period (2017–2019) compared with the Pandemic period (2020–2022). However, on a year-by-year basis, resistance prevalence increased significantly in 2020, 2021, and 2022 compared with 2017 and 2018. When comparing resistance prevalence by antimicrobial, resistance in 2019 exceeded 2017 and 2018; in 2021, resistance surpassed 2017, 2018, and 2020; and in 2022 it was higher than in 2017.

The increased prevalence of resistance after 2020 is directly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, which overwhelmed healthcare systems globally. In Brazil, the creation of COVID-19-specific ICUs in 2020 revealed a marked increase in infections by multidrug-resistant bacteria in these patients. Prolonged hospital stays in environments conducive to microorganism transmission heightened the risk of coinfections and worsened prognosis [36]. Moreover, dysregulated immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection, characterized by exacerbated inflammation and immunosuppression, predispose critically ill patients to bacterial colonization. Bacterial infections in ICU patients with COVID-19 substantially aggravate the clinical course, increasing mortality [37,38].

During the pandemic, there was increased antimicrobial prescribing for presumed secondary infections in COVID-19 patients, with macrolides frequently used in outpatient settings, potentially contributing to rising resistance [36]. In ICUs, our results show that older and immunocompromised individuals were more susceptible to infections driven by imbalance between the immune system and infectious agents, thereby increasing mortality. Studies indicate that secondary bacterial infections contributed to 50% of deaths among COVID-19 patients in 2020 [37,38,39].

Mota, Oliveira, and Souto (2018) [40] observed that about 30% of nosocomial infections occur in ICUs and are associated with multidrug-resistant organisms (resistant to three or more antimicrobial classes), also linking them to worse ICU outcomes. Post-pandemic studies [37,38,39,40] similarly demonstrate increased resistance during the pandemic, in line with our findings. Given the increased prevalence of resistance, enhanced control and surveillance by hospital teams is essential to reduce and prevent microorganism dissemination in ICUs.

When evaluating the association between bacterial resistance prevalence and mortality, we found no overall association in the ICU. However, when analyzing yearly prevalence in death outcomes only, we observed greater resistance prevalence in 2022 among those who died. Additionally, from 2017 to 2022, we demonstrated increased resistance in Acinetobacter iwoffi, Enterobacter cloacae (CESP), Enterococcus sp., Enterobacter aerogenes (CESP), and Klebsiella oxytoca, with resistance (p < 0.001) associated with death.

As previously discussed, inappropriate and excessive antimicrobial use is the primary driver of this alarming scenario, and pandemic practices likely contributed to rising resistance. Epidemiological reports indicate increased incidence of superinfections caused by ESKAPE bacteria (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter sp.), particularly carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales, which exhibit resistance to carbapenems and other broad-spectrum agents, posing a major challenge for treating nosocomial infections. Moreover, global estimates suggest that antimicrobial resistance accounts for approximately five million deaths annually [41,42].

Naue et al. (2021) [43] reported higher prevalence of ESBL-producing (Extended-spectrum β-lactamase) Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Acinetobacter baumannii in ICUs, as well as increased resistance profiles during the COVID-19 pandemic. In another study, 7.2% of COVID-19 patients developed secondary infections, indicating high prevalence of bacterial infections with elevated resistance and mortality, especially in ICUs [44]. Similarly, Polly et al. (2021) [45] described rising global prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates and increased mortality associated with these multidrug-resistant pathogens. The same authors also reported higher prevalence of multidrug-resistant infections due to carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, with these increases linked to higher mortality and longer hospital stays among COVID-19 patients [44]. These results underscore the importance of implementing rigorous infection control measures to prevent microorganism dissemination.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of health systems in the face of increasing infections by multidrug-resistant bacteria, driven by inappropriate use of invasive devices and lapses in hygiene measures. Neglect of basic prevention practices, such as hand hygiene and proper PPE use, combined with indiscriminate medication use, resulted in an 86% increase in infections by multidrug-resistant bacteria during the pandemic, overburdening health systems and increasing mortality [46].

This context fosters greater antibiotic prescribing, heightening the risk of selecting resistant microbiota, a serious contemporary problem with complex and severe consequences. An integrative review showed antibiotic use in approximately 62.4% of COVID-19 cases, even with limited evidence of bacterial infection [47]. Difficulty distinguishing virus-driven inflammation from bacterial infection in severely ill patients, especially those on mechanical ventilation, promoted the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, contributing to rising resistance [38]. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of bacterial infections in COVID-19 patients is essential to avoid inappropriate antibiotic use and consequent resistance increases. Our results highlight the importance of implementing appropriate diagnostic and treatment protocols to optimize clinical outcomes, monitor bacterial resistance, and improve outcomes for ICU patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive six-year longitudinal analysis of bacterial resistance patterns in ICUs, spanning both the pre-pandemic and COVID-19 pandemic periods. By integrating clinical, sociodemographic, microbiological, and outcome data across different ICU types, the study offers a robust assessment of how large-scale epidemiological events may reshape antimicrobial resistance dynamics in high-complexity settings.

Our findings demonstrate a notable increase in the prevalence of resistant pathogens during the pandemic period, with specific microorganisms showing significant associations with ICU mortality. Moreover, age emerged as an independent predictor of death, regardless of sex, reinforcing the multifactorial nature of adverse outcomes in critical care. These results underscore the need for strengthened antimicrobial stewardship, reinforced infection prevention strategies, and continuous microbiological surveillance to mitigate the impact of resistance and improve patient outcomes in intensive care environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.P. and M.N.F.; methodology, G.A.P., R.d.S.M. and M.N.F.; software, L.M.S. and M.M.S.; validation, G.A.P. and M.N.F.; formal analysis, V.A.d.O. and P.B.G.F.; investigation, G.A.P. and M.N.F. resources, M.N.F.; data curation, L.M.S. and M.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.F.; writing—review and editing, M.S.L. and T.G.H.; visualization, G.A.P. and M.N.F.; supervision, M.N.F.; project administration, M.N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the Brazilian National Health Council and approved by the UNIJUÍ Ethics Committee (CAAE: 69416623.3.0000.5350; approval no. 6.101.715; 6 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Individual patient consent was not required for this retrospective analysis of clinical data, in accordance with the guidelines of the UNIJUÍ Ethics Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during this retrospective investigation is not publicly available due to institutional policies and ethical restrictions related to patient confidentiality. However, de-identified data may be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and following authorization from the UNIJUÍ Ethics Committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ICU—Intensive Care Unit; WHO—World Health Organization; COVID-19—Coronavírus Disease 19; SARS-CoV-2—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome - Coronavirus-2; HICS—Hospital Infection Control Service; Adult ICU—Adult Intensive Care Unit; COVID-19 ICU—COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit; BAL—Bronchoalveolar Lavage; CESP—Citrobacter–Enterobacter–Serratia–Providencia; ESBL—Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase; KPC—Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenems; MRSA—Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus; AMR—Antimicrobial Resistance; ESKAPE—Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa e Enterobacter sp.

References

- Dias, M.L.S.; Molinaro, C.G.S.; Aragão, L.C.M.; de Lima, E.M.; Correal, J.C.D. Análise comparativa da resistência bacteriana de microrganismos causadores de bacteremia em pacientes críticos nos períodos pré-pandemia e COVID-19 em um hospital terciário privado de Rio de Janeiro. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, G.B.; Trevisan, M. O uso indevido de antibióticos e o eminente risco de resistência bacteriana. Rev. Artigos. Com 2021, 30, e7902. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.O.; Nogueira, J.M. Uso indiscriminado de antibióticos durante a pandemia: O aumento da resistência bacteriana pós-COVID-19. RBACRevista Bras. Análises Clin. 2021, 53, 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Santana, E.S.; da Silva Assunção, E.; Assunção, R.C.L.; dos Santos Tobias, D.F.; de Souza Borges, A.; de Paula, E.; Névoa, A.C.d.L.; de Queiroz, I.M.S. Resistência bacteriana em ambientes hospitalares: Principais causas e impactos na saúde. Stud. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 5, e10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedade Brasileira de Microbiologia (SBM). A ameaça das super Bactérias. Rev. Microb. Foco. 2017, 8, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco Nascimento, Q.H.; de Oliveira Rezende, G. Resistência bacteriana aos antibióticos na pandemia COVID-19. Rev. Foco 2024, 17, e6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.B.G. Uso de Antibióticos 48h Antes do Óbito em Pacientes Internados em Unidades de Terapia Intensiva em Pacientes de COVID-19. 2023. Available online: https://repositorio.bahiana.edu.br/home (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Golli, A.L.; Popa, S.G.; Ghenea, A.E.; Turcu, F.L. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Antibiotic Resistance of Gram-Negative Pathogens Causing Bloodstream Infections in an Intensive Care Unit. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentini, C.; Corcione, S.; Lo Moro, G.; Mara, A.; De Rosa, F.G.; Zotti, C.M.; Collaborating Group “Unità Prevenzione Rischio Infettivo (UPRI), Regione Piemonte”. Impact of COVID-19 on antimicrobial stewardship activities in Italy: A region-wide assessment. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakbar, I.; Delamarre, L.; Curtel, F.; Duclos, G.; Bezulier, K.; Gragueb-Chatti, I.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Forel, J.M.; Leone, M. Antimicrobial Stewardship during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Retrospective Analysis of Antibiotic Prescriptions in the ICU across COVID-19 Waves. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaur, L.; Eguibar, I.; Olazabal, A.; Aseguinolaza, M.; Leizaola, O.; Guridi, A.; Iglesias, M.T.; Rello, J. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship in organisms causing nosocomial infection among COVID-19 critically ill adults. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 119, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, A.C.; Kaefer, F.; Pereira, D.K.S. A A resistência bacteriana à antimicrobianos na pandemia da COVID-19: Bacterial resistance to antimicrobials the COVID-19 pandemic. Extensão Foco 2023, 11, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226.

- Pulingam, T.; Parumasivam, T.; Gazzali, A.M.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Chee, J.Y.; Lakshmanan, M.; Chin, C.F.; Sudesh, K. Antimicrobial resistance: Prevalence, economic burden, mechanisms of resistance and strategies to overcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 170, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, L.; Danski, M.T.R.; Piubello, S.M.N.; Pereira, J.D.F.G.; Jantsch, L.B.; Costa, L.B.; de Oliveira dos Santos, J.; Arrué, A.M. Perfil clínico e fatores associados ao óbito de pacientes COVID-19 nos primeiros meses da pandemia. Esc. Anna Nery 2021, 26, e20210203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmann, V.F.; Junior, A.M.; Moroni, J.G.; Moreira, J.P.S.; Orlando, B.L.B.; de Oliveira, C.S.; Giancursi, T.S.; Coltri, L.F. Perfil de resistência de bactérias gram positivas isoladas em culturas de pacientes com iras internados por COVID-19 grave em UTI. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodré, M.M.D.C.; dos Santos, U.R.; Santana, M.E.V.; Santana, N.P.S.; Guzmán, J.L.D.; Povoas Filho, H.P.; Conceição, A.O.; da Mata, C.P.S.M.; Romano, C.C.; de Carvalho, L.D. Parâmetros Clínicos e Epidemiológicos na Covid-19 e sua Correlação com Óbito em Pacientes Atendidos em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva (UTI). Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzani, O.T.; Bastos, L.S.; Gelli, J.G.M.; Marchesi, J.F.; Baião, F.; Hamacher, S.; Bozza, F.A. Characterisation of the first 250000 hospital admissions for COVID-19 in Brazil: A retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021, 9, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.C.; Dos Santos, A. Análise do tempo de internação e desfecho das internações por COVID-19 na população idosa. In Livro de Actas, 1° Congresso Internacional de Longevidade Gegop, Politicas Publicas Sobre Envejecimiento; UFV, Instituto de Políticas Públicas e Desenvolvimento Sustentável: Viçosa, Brazil, 2022; Volume 1, p. 92. ISBN 978-85-66148-54-1. Available online: https://cch.ufv.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Livro-de-Atas-Congresso-Internacional-Longevidade_Gegop_compressed.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Silva Gde, S.S.; Valente, M.M.Q.P.V.; Monteiro, M.A.C.M.; Lima, G.K.L.; Farias AÉllen, A.F.; Studart, R.M.B.S. Fatores Intervenientes no Tempo de Internação Hospitalar de Pacientes com COVID-19. Rev. Enferm. Atual. Derme 2023, 97, E023084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.M.; Menezes, A.C.; Cardoso, C.S.; Seixas, A.F.A.M.; Mendes, M.S. Características clínicas e fatores associados à internação hospitalar entre pacientes com COVID-19 atendidos pelo serviço de teleassistência do município de divinópolis, minas gerais. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.V.D.; Pereira, A.K.A.D.M.; Barreto, F.A.; Oliveira, M.K.F.D.; Bessa, M.M.; Freitas, R.J.M.D. Percepções do homem sobre a assistência na atenção primária à saúde. Rev. Enferm. UFSM 2021, 11, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Pereira, M.V.; da Fonseca Rodrigues, F.B.; de Mesquita Silva, D.K.; Junior, G.C.L.; de Carvalho Guimarães, J.P.; Meireles, D.R.; Castro, J.B.; Dantas, I.P.; Sales, E.S.; Sales, L.C.C.L.; et al. Percepções Sobre o Desafio do Cuidado à Saúde Masculina na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Estud. Avançados Sobre Saúde Nat. 2023, 1–14. Available online: https://www.periodicojs.com.br/index.php/easn/article/view/1903/1685 (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Kruger, A.R.; Saute, A.A.B.Q.; da Veiga Vier, C.; Kreutz, D.N.M.; Morgan, M.I.M.; da Rosa Miltersteiner, D.; Marrone, L.C.P. A relação entre a idade e o aumento do risco de óbito com COVID-19 em UTI de hospital universitário. Rev. Iniciação Científica Ulbra 2021, 1–4. Available online: http://www.periodicos.ulbra.br/index.php/ic/article/viewFile/7013/4421 (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Castro, M.L.M.D.; Almeida, F.D.A.D.C.; Amorim, E.H.; Carvalh, A.I.L.C.D.; Costa, C.C.D.; Cruz, R.A.D.O. Perfil de pacientes de uma unidade de terapia intensiva de adultos de um município paraibano. Enfermería Actual Costa Rica 2021, 40, 12–26. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/enfermeria/n40/1409-4568-enfermeria-40-42910.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M. Espectro clínico da COVID-19 em idosos: Revisão integrativa da literatura. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 68173–68186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.A.; Mateus, S.R.M.; Silva, M.F.d.O.; Figueiredo, P.T.d.S.; Campolino, R.G. Perfil epidemiológico da mortalidade de pacientes internados por COVID-19 na unidade de terapia intensiva de um hospital universitário/Epidemiological profile of mortality of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in the intensive care unit of a university hospital. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 45981–45992. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, F.; Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Feng, C. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci. China. Life Sci. 2020, 63, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, M. Antibiotic Resistance and Mortality in ICU Patients: A Retrospective Analysis of First Culture Growth Results. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberoi, A.; McCready-Vangi, A.; Grice, E.A. The wound microbiota: Microbial mechanisms of impaired wound healing and infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.A.; de Araújo Vilar, K.T.; Silva, F.R.A.; Valini, T.G.M.; dos Santos Guedes, B.L.C.; da Silva, J.E.L.; de Souza Barbosa, A.T.; de Lima Franco, R.T.; de Carvalho Marques, M.L.F.; de França, S.M. A segurança do paciente e os impactos da resistência bacteriana na atenção hospitalar. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2023, 23, e13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçmaz, B.; Keske, Ş.; Sişman, U.; Ateş, S.T.; Güldan, M.; Beşli, Y.; Palaoğlu, E.; Çakar, N.; Ergönül, V. COVID-19 associated bacterial infections in intensive care: Incidence, risk factors and outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferliçolak, L.; Sarıcaoğlu, E.M.; Bilbay, B.; Altıntaş, N.D.; Yörük, F. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in COVID-19 Patients: Microbiology and Antibiotic Resistance Patterns. 2023. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36912408/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Costa, R.L.; da Cruz Lamas, C.; Simvoulidis, L.F.N.; Espanha, C.A.; Moreira, L.P.M.; Bonancim, R.A.B.; Weber, J.V.L.A.; Ramos, M.R.F.; de Freitas Silva, E.C.; de Oliveira, L.P.; et al. Secondary Infections in Patients with COVID-19 Admitted to Intensive Care Units. 2022. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rimtsp/a/d554tBSCFK6Hzmmq7LsFnWf/?format=html&lang=en (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Pintea-Simon, I.A.; Bancu, L.; Mare, A.D.; Ciurea, C.N.; Toma, F.; Brukner, M.C.; Văsieșiu, A.M.; Man, A. Secondary bacterial infections in critically ill COVID-19 patients in a temporary ICU: Prevalence and antibiotic resistance. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo Souto, X. COVID-19: Aspectos gerais e implicações globais. Recital—Rev. Educ. Ciência Tecnol. Almenara/MG 2020, 2, 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Díaz, A.; López Berrio, S.; Román Herrera, E.D.L.C. Resistencia antimicrobiana: Una problemática agravada por la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev. Inf. Científica 2024, 1–4. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/ric/v103/1028-9933-ric-103-e4512.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- da Silva, K.M.R.; de Araújo Oliveira, R.M.; de Oliveira Araújo, A.J.R.; de Paula, C.C.C.; da Silva Tavares, P.; de Souza Santana, F.; de Sousa Marinho, A.L.; Melo, D.T.; Velôso, D.S.; do Nascimento Vieira, J.F.P.; et al. Implications of antibiotic use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e20210715684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.M.C.M. Impacto da COVID-19 no Perfil de Resistência aos Antibióticos de Isolados Microbiológicos de um Serviço de Medicina Intensiva. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. Available online: https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/entities/publication/784bf5e6-a22c-4253-bb4b-6c854ed96774 (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Mota, F.S.; Oliveira, H.A.D.; Souto, R.C.F. Perfil e prevalência de resistência aos antimicrobianos de bactérias Gram-negativas isoladas de pacientes de uma unidade de terapia intensiva. RBAC 2018, 50, 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo BLde, A.; de Souza, D.Q.; Martins, G.L.; Peixoto, H.G.R.; Correa, J.L.G.; Pires, L.M.T.; Werneck, L.A.; de Assis, P.A.; Freire PEde, J.; Nunes, T.C. O impacto da resistência antimicrobiana bacteriana no manejo da sepse neonatal. Braz. J. 2023, 9, 25645–25655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Cantón, R. COVID-19: Impact on prescribing and antimicrobial resistance. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2021, 34, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naue, C.R.; Leite, M.I.M.; Colombo, A.; Silva, C.F. Prevalência e perfil de sensibilidade antimicrobiana de bactérias isoladas de pacientes internados em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva de um hospital universitário do Sertão de Pernambuco. Semin. Ciências Biológicas Saúde 2021, 42, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Meira, F.; Cózar-Llistó, A.; Dueñas, G.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; Garcia-Pouton, N.; Chumbita, M.; Cardozo, C.; Hernandez-Meneses, M.; Alonso-Navarro, R.; et al. Real-life use of remdesivir in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2021, 34, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, M.; de Almeida, B.L.; Lennon, R.P.; Cortês, M.F.; Costa, S.F.; Guimarães, T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of multidrug resistant bacterial infections in an acute care hospital in Brazil. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.A.; Machado, G.S.; Tavares, J.V.A.; Rocha, M.J.d.a.; Rabelo, P.W.L. Impacto da pandemia de COVID-19 na ocorrência de resistência bacteriana frente aos antimicrobianos-revisão integrativa: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the occurrence of bacterial resistance to antimicrobials-integrative review. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 54080–54099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisini, A.; Boni, S.; Vacca, E.B.; Bobbio, N.; Del Puente, F.; Feasi, M.; Prinapori, R.; Lattuada, M.; Sartini, M.; Cristina, M.L.; et al. Impacto da pandemia de COVID-19 na epidemiologia da resistência aos antibióticos em uma unidade de terapia intensiva (UTI): A experiência de um centro italiano do noroeste. Antibióticos 2023, 12, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.