Abstract

Kuwait faces a significant public health challenge from obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), conditions known to disrupt the natural balance of oral bacteria. This imbalance, or dysbiosis, can promote gum disease and may worsen metabolic health. While the intragastric balloon (IGB) is a common, less invasive weight-loss procedure, its specific effect on the community of bacteria in saliva remains unclear, especially for high-risk groups. The objective of this study was to investigate changes in the salivary microbiota of obese prediabetic patients following IGB placement. We recruited 20 obese patients (11 female, 9 male; average age 31.5) from a clinic in Kuwait. Saliva samples were collected just before IGB (Allurion™) insertion and again 6 weeks after that. Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we identified the bacterial species present and used bioinformatic tools to analyze diversity and abundance. Our analysis revealed that the overall diversity and structure of the salivary microbial community remained stable after the procedure. However, we detected notable changes in specific types of bacteria. The relative abundance of several genera, including Veillonella, Porphyromonas, and Fusobacterium, shifted significantly. At the species level, Porphyromonas pasteri and Haemophilus parainfluenzae became less abundant, while certain Veillonella and Streptococcus species increased in number after the IGB was placed. In conclusion, for obese prediabetic patients in Kuwait, the salivary microbiome demonstrates remarkable stability in the weeks following IGB surgery. The procedure did not drastically alter the overall ecosystem, but it did trigger specific, subtle changes in certain bacterial populations. This suggests the oral microbiota is resilient, adapting to the new physiological conditions without a major upheaval.

1. Introduction

Obesity and diabetes are significant public health concerns in Kuwait, with rising prevalence rates due to lifestyle factors, dietary habits, and genetic predisposition. Approximately 45.36% of adults in Kuwait are affected by obesity, leading to an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, which poses a major burden on the healthcare system [1,2]. In addition, almost 25.5% of adults aged 25–70 in Kuwait had diabetes, according to the International Diabetes Federation. These conditions not only increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, and certain cancers but also place a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide. The pathophysiology of both obesity and T2DM is increasingly understood to involve chronic low-grade inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, processes in which the human microbiota—particularly the gut and oral microbiomes—play a pivotal role [3,4,5].

Recent research has highlighted the bidirectional relationship between metabolic diseases and the oral microbiome. Individuals with obesity and T2DM often exhibit oral dysbiosis, characterized by reduced microbial diversity and a shift toward pathogenic taxa, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia, alongside a reduction in commensal genera like Streptococcus and Rothia [6,7,8]. These microbial alterations are associated with increased risk of periodontal disease and may further exacerbate systemic inflammation and glycemic dysregulation, suggesting that the oral microbiome is both a marker and a potential mediator of metabolic disease progression [6,9,10]. Notably, studies have shown that the oral microbiota in T2DM and obese patients is less diverse and more pathogenic compared to healthy controls, with specific reductions in Actinobacteria and increases in disease-associated genera [8,11,12]. Dietary patterns, such as high intake of sugary snacks and low consumption of fish and nuts, further modulate the oral microbiome, potentially compounding metabolic risk [13].

Bariatric surgery remains one of the most effective interventions for sustainable weight loss and improvement of metabolic parameters in individuals with obesity and T2DM [1,14,15]. Among the various surgical options, the intragastric balloon (IGB) procedure has emerged as a minimally invasive, FDA-approved therapy for adults with a body mass index (BMI) between 30 and 40 kg/m2 who have not achieved adequate weight loss through lifestyle modification alone [12]. IGB therapy induces weight loss by occupying gastric volume and promoting early satiety, typically resulting in 7–15% total body weight loss over a six-month period, with concurrent improvements in blood glucose, blood pressure, and lipid profiles [16]. However, long-term maintenance of these benefits is contingent upon sustained behavioral and dietary changes, as weight regain is common after balloon removal [16].

The impact of bariatric surgery on the gut microbiota has been well documented, with evidence showing significant shifts in microbial composition and function that contribute to metabolic improvements [1,12,17]. More recently, attention has turned to the oral microbiome, with studies indicating that bariatric procedures—including IGB—can also induce changes in oral microbial communities [11,18]. These changes may be driven by alterations in diet, immune function, and systemic inflammation following surgery. In a recent study, while shift toward a healthier oral microbiome post-surgery was seen, an increase in certain opportunistic pathogen species was also evident, highlighting the complexity and individual variability of these responses [18]. For example, reductions in periodontal pathogens and increases in beneficial taxa such as Streptococcus salivarius and Veillonella spp. have been observed following weight loss interventions, suggesting potential oral health benefits. Conversely, some patients may experience increased levels of Streptococcus mutans or Candida species, underscoring the need for careful monitoring.

Despite these advances, there is a dearth of knowledge on the effects of IGB therapy on the salivary microbiota, particularly in populations with high rates of obesity and T2DM. Understanding these changes is critical, as the oral microbiome may serve as both a biomarker and a modifiable target for interventions aimed at improving both oral and systemic health [6,9,10]. This is especially relevant in regions such as Kuwait, where the burden of obesity and diabetes is among the highest globally. The aim of this study was to characterize the salivary microbiota in obese patients with diabetes undergoing intragastric balloon therapy, both before and after the procedure, to elucidate potential microbial shifts and their implications for oral and systemic health.

2. Materials and Methods

In this pilot study, 22 patients visiting “The Clinic”, a private medical center, for intragastric balloon placement were recruited, of whom 2 were lost to follow-up.

Obese prediabetic patients between the ages of 20 and 60 years were recruited for the study. Smokers, patients with systemic diseases other than diabetes (e.g., Sjögren syndrome, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic syndrome), patients who used antibiotics during the last 6 months, and patients with removable oral appliances (such as orthodontic braces and prostheses) were excluded from the study.

Upon inclusion into the research, each patient’s age, gender, blood pressure, waist circumference, BMI, and HbA1c levels were recorded.

Saliva samples were collected from each patient under the supervision of a bariatric surgeon. Approximately 2 mL of saliva was collected by spitting method from each patient into a sterile 15 mL tube. As a standard practice, the patients were instructed not to eat solid food for at least 8 h and no liquids for at least 2 h before the surgery. However, they were asked to do routine oral hygiene on the day of the surgery. The first sample was taken before the placement of the intragastric balloon (baseline), and a second sample was taken six weeks later (follow-up). All patients received the same balloon brand (Alluri-on™, Natick, MA, USA), which was placed by the same surgeon, and followed an identical diet supervised by the same dietician. The balloons were removed six months after placement. Regarding oral hygiene, patients received instructions from three dental students at least two weeks before their arrival for the bariatric balloon surgery.

2.1. DNA Isolation and Next-Generation Sequencing

ZymoBIOMICS®-96 MagBead DNA Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to extract DNA from samples as per manufacturer’s instructions, and extracted DNA was prepared for targeted sequencing with the Quick-16S Plus NGS Library Prep Kit (V1–V3) (Cat No. D6440-PS1, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) targeting V1–V3 region of 16S rRNA sequences. The sequencing library was prepared using an innovative library preparation process in which PCR reactions were performed in real-time PCR machines to control cycles and therefore limit PCR chimera formation. The final PCR products were quantified with qPCR fluorescence readings and pooled together based on equal molarity. The final pooled library was cleaned up with the Select-a-Size DNA Clean & Concentrator™ (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), then quantified with TapeStation® (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Qubit® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, WA, USA). The final library was sequenced on Illumina® NextSeq 2000™ with a p1 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) reagent kit (600 cycles). The sequencing was performed with 25% PhiX spike-in.

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis of Sequence Data

Raw 16S V1V3 amplicon sequences obtained from Zymo Research were quality-filtered, denoised, pair-end merged, and chimera removed with the DADA2 tool (version 1.12.1) [19]. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) generated by DADA2 were subjected to species-level taxonomy assignment against the FOMC Reference Sequence Set (https://microbiome.forsyth.org/ftp/refseq, accessed on 15 January 2025) that consists of 1015 full-length 16S rRNA sequences from HOMD V15.22, 356 from MOMD V5.1, and 22,126 from NCBI, making up a total of 23,497 sequences. Species-level taxonomy assignment algorithm is available at https://microbiome.forsyth.org/algorithm.php (accessed on 15 January 2025). Altogether, these sequences represent a total of 17,035 oral and non-oral microbial species. Species-level read count tables were imported using R’s “phyloseq” package (version 1.28.0) for downstream analyses. Alpha diversity was calculated in 3 measurements: (1) number of species (observed), (2) Shannon index, and (3) Simpson index using “phyloseq” package’s “plotrichness” function [20]. Alpha diversity significance tests were evaluated with QIIME2 (version 2020.11) “alpha-group-significance” function [21]. Beta diversity NMDS plots were generated with the “ordinate” function in “phyloseq,” and beta diversity significance tests were evaluated with QIIME2 “beta-group-significance” function [21]. The FOMC analysis pipeline software version information is available at https://microbiome.forsyth.org/software.php. (Accessed on 21 August 2025)

3. Statistics

The differences in the relative abundances of taxa between baseline and follow-up samples were determined using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test, since the data was not normally distributed as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test and histograms. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with statistical software (SPSS V.22, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results

The mean age of patients who participated in this study was 31.5 years. 11 of the participants were females, and 9 were males. The median BMI of the patients was 32.5 (26.3–47.9), while for HbA1c, the median value was 5.2 (4.0–6.0).

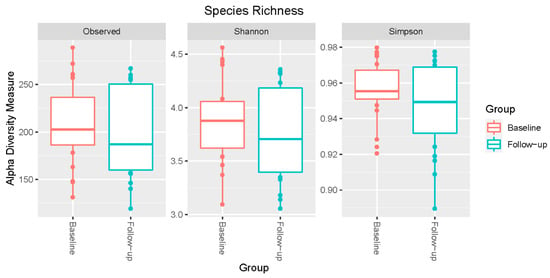

Figure 1 shows alpha diversity index for all samples. Mean diversity index values from observed Shannon (baseline = 5.62, follow-up = 5.49) or Simpson (baseline = 0.956, follow-up = 0.948) analyses did not show differences between the baseline and follow-up groups (p > 0.05). ANOSIM analysis yielded an R-value of 0.007, suggesting that the microbiota composition between the two groups did not differ.

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity analysis of the salivary microbiota of patients undergoing intragastric balloon surgery. Microbial alpha diversity measures between baseline and follow-up time points were compared. Box plots illustrate the distributions for three metrics: Observed (left), Shannon index (middle), and Simpson index (right).

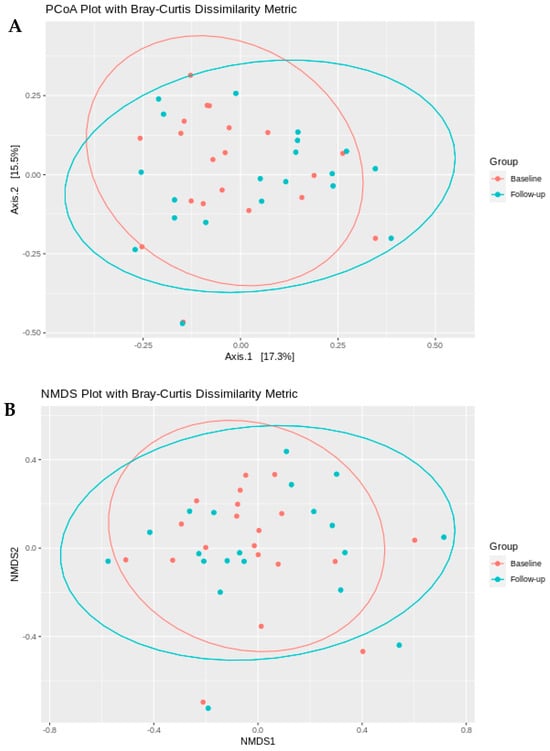

The principal coordinate analysis based on Bray–Curtis Dissimilarity metric of all species did not separate the two groups, baseline, and follow-up (Figure 2A). The first two principal coordinates explained 17.3% and 15.5% of the variation (p > 0.05). Similarly, the Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) did not reveal any significant segregation of the subjects between baseline and follow-up groups (Figure 2B)

Figure 2.

Microbial community beta diversity between baseline and follow-up time points. (A) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and (B) non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination plots based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metrics. Samples from the baseline group are shown in red, and samples from the follow-up group are shown in blue. Points represent individual samples, with closer proximity indicating greater similarity in microbial community composition.

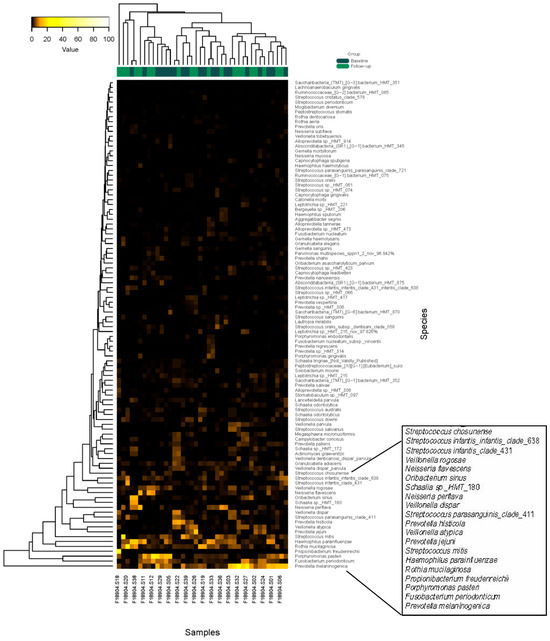

The heatmap from the microbiota analysis (Figure 3) illustrates the relative abundance of various bacterial species across different samples. The rows represent different bacterial species, while the columns correspond to individual samples. The color intensity indicates the abundance levels, with darker shades typically representing higher abundance. Key observations, as visualized on the lower side of the heatmap with higher color intensity, include the presence of P. melaninogenica, F. periodonticum, P. pasteri, H. parainfluenzae, S. mitis and a few Veillonella species. Several Streptococcus species, such as Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus sanguinis, showed varying levels of abundance across samples. Prevotella species, including Prevotella oris and Prevotella nigrescens, also appear to be prominent in certain samples. Additionally, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Veillonella parvula are notable for their presence, suggesting their potential role in the microbiota composition. The heatmap provides a comprehensive overview of the microbial community structure, highlighting both common and less abundant species, which could be crucial for understanding the ecological dynamics and potential functional roles within the microbiota.

Figure 3.

Heat map of the microbiota data. Two-way clustering was used for the analysis.

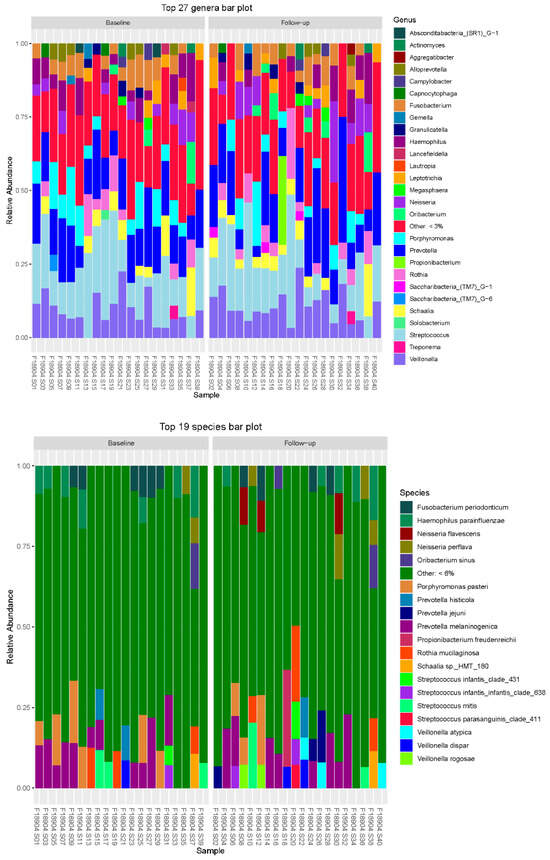

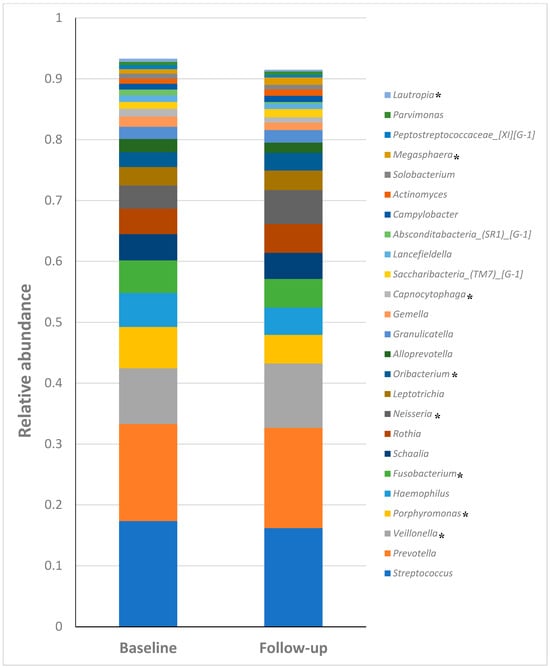

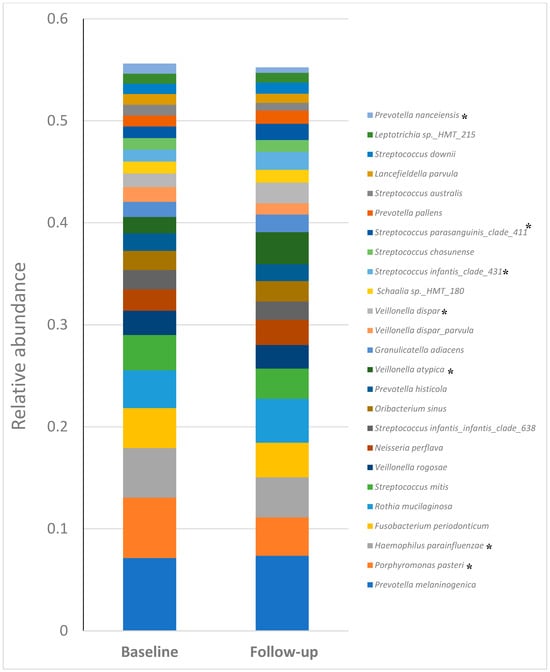

Figure 4 represents genera and species distribution for each subject at baseline and follow-up. The bar chart from the microbiota analysis study illustrates the relative abundance of the top 27 bacterial genera (Figure 5) and the top 19 bacterial species across different samples in the baseline and follow-up groups, as seen in Figure 6. Each bar represents a sample, with colored segments indicating the relative abundance of each genus.

Figure 4.

Genera and species distribution for each subject at baseline and follow-up.

Figure 5.

Relative abundances of the top 25 most predominant genera. * p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Relative abundances of the top 25 most predominant species. * p < 0.05.

The prominent presence of Streptococcus and Prevotella, which are among the most abundant genera across many samples, is seen in Figure 5. Fusobacterium and Veillonella also show significant representation, highlighting their potential importance in the microbial community. Other notable genera include Neisseria, Haemophilus, and Actinomyces, which are consistently present but in varying abundances. The “Other” category, representing genera with less than 3% abundance, underscores the diversity of the microbial community. This bar chart provides a comprehensive overview of the dominant genera and their distribution, offering insights into the microbial composition and potential changes between baseline and follow-up samples.

At the species level, Fusobacterium periodonticum and Haemophilus parainfluenzae are found across multiple samples. Streptococcus species, such as Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus infantis, also show significant abundance. Prevotella species, including Prevotella melaninogenica and Prevotella histicola, are notably present, indicating their potential role in the microbiota. Veillonella species, such as Veillonella atypica and Veillonella dispar, are also well-represented. The “Other” category, representing species with less than 6% abundance, underscores the diversity of the microbial community. This bar chart provides a clear visual representation of the dominant species and their distribution, highlighting the microbial composition and potential shifts between baseline and follow-up samples.

Of the 25 most predominant bacterial genera found in both baseline and follow-up groups, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Veillonella, Porphyromonas, Haemophilus and Fusobacterium were the most abundant genera. The genera Veillonella (0.09 vs. 0.105), Porphyromonas (0.068 vs. 0.046), Fusobacterium (0.053 vs. 0.04), Neisseria (0.03 vs. 0.055), Oribacterium (0.024 vs. 0.03), Capnocytophaga (0.012 vs. 0.008), Megasphaera (0.007 vs. 0.012) and Lautropia (0.005 vs. 0.002) showed significant (p < 0.05) differences in relative abundance between baseline and follow-up groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relative abundances of genera and species with significant differences between baseline and follow-up.

At the species level, P. melaninogenica, P. pasteri, H. parainfluenzae, F. periodonticum, R. mucilaginosa, S. mitis, and V. rogosae were the most abundant. Among the top 25 species, P. pasteri (0.06 vs. 0.037), H. parainfluenzae (0.048 vs. 0.039), V. atypica (0.015 vs. 0.034), V. dispar (0.01 vs. 0.021), S. infantis clade 431 (0.01 vs. 0.017), S. parasanguinis (0.011 vs. 0.016) and P. nanceiensis (0.009 vs. 0.005) exhibited significant (p < 0.05) differences between the baseline and the follow-up groups (Table 1).

5. Discussion

The present study found that the salivary microbiota of obese patients undergoing intragastric balloon surgery exhibited high compositional stability, with no remarkable overall changes between baseline and six-week follow-up samples. Although overall microbial diversity, as measured by alpha diversity indices (observed, Shannon, and Simpson), remained consistent [22], specific genera and species displayed significant shifts in relative abundance. The lack of change in alpha diversity contrasts with studies linking more invasive bariatric procedures to ecological disruption but aligns with recent local findings showing no difference in diversity across body mass categories [23]. This suggests the less invasive balloon surgery does not induce profound microbial restructuring and may reflect population-specific traits, as the obesity–microbiome relationship varies across ethnicities [24,25,26,27].

This overall stability is supported by PCoA and NMDS analyses showing minimal, non-significant variation, reinforcing that the salivary microbial community maintains temporal resilience absent major physiological shifts [28,29]. The prominence of typical oral taxa such as Prevotella melaninogenica, Fusobacterium periodonticum, and various Streptococcus and Veillonella species in heatmap analysis underscores this core stability [30]. Notably, the consistent presence of species like Fusobacterium nucleatum and Veillonella parvula, linked to periodontal and metabolic dysbiosis [31,32], suggests a baseline ecological state in obese individuals that remains balanced post-intervention, supporting the ecological resilience hypothesis [33,34].

Bar chart analysis confirmed the dominance of core genera like Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Veillonella [35], while revealing significant, subtle shifts in the relative abundance of genera such as Veillonella, Porphyromonas, and Fusobacterium. These minor fluctuations may represent adaptive responses to altered gastric volume and nutrient delivery [36,37]. Conversely, decreases in species like Porphyromonas pasteri and Haemophilus parainfluenzae [38] might reflect a reduction in inflammation-associated taxa following surgery [39]. This pattern of specific taxonomic adjustments within a stable community framework aligns with a dynamic stability model [33], indicating the procedure induces subtle ecological recalibration rather than transformative change, differing from more invasive surgeries that alter host metabolism more drastically [40,41]. The increased abundance of certain Streptococcus species post-surgery may indicate a competitive advantage under new gastric conditions [42]. Further, increase in the abundance of Veillonella and other species may have implications in caries, periodontitis, halitosis and oral inflammation. Future research employing functional metagenomics is needed to link these structural insights to metabolic pathways and clinical outcomes, addressing the specific health challenges in this population [43,44,45,46].

This study acknowledges several limitations. Although recent data indicate an adult obesity prevalence of 45% in Kuwait, the present investigation was designed as a pilot study to obtain preliminary insights into this salient research area. A comprehensive research proposal aimed at analyzing a larger cohort is currently under development at our institute. Additionally, the follow-up period of 6 weeks may be insufficient to detect measurable shifts in microbiota composition. This constraint was primarily due to the standard clinical follow-up schedule for bariatric surgery patients, which typically occurs immediately after six weeks postoperatively. Confounding factors, including oral hygiene, periodontal status, and diet, were not adjusted for in the present analysis. These are critical variables that can significantly influence the salivary microbiota [47]. Another key limitation of this study is the absence of a control group without intragastric balloon placement. Such a control would have enabled the differentiation of intervention-specific effects from background temporal variations in the gut microbiota, thereby allowing a more precise attribution of observed effect sizes to the balloon procedure.

In conclusion, despite limitations such as a small sample size and short follow-up period, the results depict a highly stable salivary microbial community among obese patients undergoing intragastric balloon surgery in Kuwait, with minor compositional adjustments reflecting ecological resilience and homeostasis. The subtle shifts in taxa like Porphyromonas and Veillonella suggest potential ecological niches influenced by the surgery’s impact on digestion and weight loss. These findings underscore the importance of integrating oral health into multidisciplinary bariatric care, advocating for the implementation of post-operative dental follow-up protocols. Such protocols would enable dentists to provide targeted preventive care by monitoring for inflammation and reinforcing hygiene, thus supporting overall patient health. Integrating these findings with functional microbiome data could further enhance our understanding of microbiota dynamics in obesity management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.D.M., N.A.A., and MK.; data curation, M.K.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, R.A.D.M. and N.A.A.; data curation, M.K.; methodology, R.A.D.M., N.A.A. and A.R.; writing, A.R.; original draft, R.A.D.M. and N.A.A.; review and editing, R.A.D.M., N.A.A., A.R. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by Kuwait University’s Health Sciences Centre Ethics Committee on 15 November 2023 with Ref No. 485. The principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki were closely followed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

The article includes the original contributions made in this study. The corresponding author can be contacted with any further questions.

Acknowledgments

We express our profound gratitude to bariatric surgeon Mohammad Jamal, dentists, and patients who took part in this research. Their collaboration was essential to the study’s success and efficient functioning. We also thank Krishna Girija and Febine Mathew for their excellent technical help and support throughout the study. The study was conducted at the Oral Microbiology Research Laboratory, Kuwait University (SRUL 01/14).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alkandari, A.; Alarouj, M.; Elkum, N.; Sharma, P.; Devarajan, S.; Abu-Farha, M.; Al-Mulla, F.; Tuomilehto, J.; Bennakhi, A. Adult Diabetes and Prediabetes Prevalence in Kuwait: Data from the Cross-Sectional Kuwait Diabetes Epidemiology Program. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haifi, A.R.; Al-Awadhi, B.A.; Al-Dashti, Y.A.; Aljazzaf, B.H.; Allafi, A.R.; Al-Mannai, M.A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents and the perception of body weight by parents or friends. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Cai, Q.; Steinwandel, M.; Hargreaves, M.K.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Blot, W.J.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Association of oral microbiome with type 2 diabetes risk. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e228046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, T.C.; Carlos, I.Z.; Duque, C.; Caiaffa, K.S.; Arthur, R.A. Interplay Among the Oral Microbiome, Oral Cavity Conditions, the Host Immune Response, Diabetes Mellitus, and Its Associated-Risk Factors-An Overview. Front Oral Health 2021, 2, 697428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, B.; Al-Marzooq, F.; Saad, H.; Benzina, D.; Al Kawas, S. Dysbiosis of the Subgingival Microbiome and Relation to Periodontal Disease in Association with Obesity and Overweight. Nutrients 2023, 15, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeb, A.T.M.; Al-Rubeaan, K.A.; Aldosary, K.; Raja, G.U.; Mani, B.; Abouelhoda, M.; Tayeb, H.T. Relative reduction of biological and phylogenetic diversity of the oral microbiota of diabetes and prediabetes patients. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, S.; Swain, J.; Woodman, G.; Edmundowicz, S.; Hassanein, T.; Shayani, V.; Fang, J.C.; Noar, M.; Eid, G.; English, W.J.; et al. Randomized sham-controlled trial of a 6-month swallowable gas-filled intragastric balloon system for weight loss. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2018, 14, 1876–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Davitkov, P.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Saumoy, M.; Murad, M.H. AGA Institute Technical Review on Intragastric Balloons in the Management of Obesity. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1811–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courcoulas, A.P.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Eaton, L.; Robinson, J.; Woodman, G.; Fusco, M.; Shayani, V.; Billy, H.; Pambianco, D.; Gostout, C. Intragastric balloon as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.B.; Ou, A.; Schulman, A.R.; Thompson, C.C. The impact of intragastric balloons on obesity-related co-morbidities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Bilal, M.; Kim, M.C.; Cohen, J. The clinical and metabolic effects of intragastric balloon on morbid obesity and its related comorbidities. Clin. Endosc. 2021, 54, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastis, S.N.; François, E.; Devière, J.; Hittelet, A.; Mehdi, A.I.; Barea, M.; Dumonceau, J.M. Intragastric balloon for weight loss: Results in 100 individuals followed for at least 2.5 years. Endoscopy 2009, 41, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Nasher, A.T.; Idris, A.M.; Chen, T. Robust species taxonomy assignment algorithm for 16S rRNA NGS reads: Application to oral carcinoma samples. J. Oral Microbiol. 2015, 7, 28934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Author Correction: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaderi, H.; Ramakodi, M.P.; Nizam, R.; Jacob, S.; Devarajan, S.; Eaaswarkhanth, M.; Al-Mulla, F. Salivary Microbiome Diversity in Kuwaiti Adolescents with Varied Body Mass Index-A Pilot Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.C.; Lagstrom, S.; Ellonen, P.; de Vos, W.M.; Eriksson, J.G.; Weiderpass, E.; Rounge, T.B. Gender-Specific Associations Between Saliva Microbiota and Body Size. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chi, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.; Deng, X. Characterization of the salivary microbiome in people with obesity. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Shapiro, J.A.; Church, T.R.; Miller, G.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Yuen, E.; Friedlander, C.; Hayes, R.B.; Ahn, J. A taxonomic signature of obesity in a large study of American adults. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, M.A.; Schloss, P.D. Looking for a Signal in the Noise: Revisiting Obesity and the Microbiome. MBio 2016, 7, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislawski, M.A.; Dabelea, D.; Lange, L.A.; Wagner, B.D.; Lozupone, C.A. Gut microbiota phenotypes of obesity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belstrom, D.; Holmstrup, P.; Bardow, A.; Kokaras, A.; Fiehn, N.E.; Paster, B.J. Temporal Stability of the Salivary Microbiota in Oral Health. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, W.; Takeshita, T.; Shibata, Y.; Matsuo, K.; Eshima, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Yamashita, Y. Compositional stability of a salivary bacterial population against supragingival microbiota shift following periodontal therapy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.; Yu, W.H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzunkova, M.; Liptak, R.; Vlkova, B.; Gardlik, R.; Cierny, M.; Moya, A.; Celec, P. Salivary microbiome composition changes after bariatric surgery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum: A commensal-turned pathogen. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Manoil, D.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Kotsakis, G.A. Veillonellae: Beyond Bridging Species in Oral Biofilm Ecology. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 774115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shade, A.; Peter, H.; Allison, S.D.; Baho, D.L.; Berga, M.; Burgmann, H.; Huber, D.H.; Langenheder, S.; Lennon, J.T.; Martiny, J.B.; et al. Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, K.; Raes, J. Microbial interactions: From networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, J.A.; Paster, B.J.; Stokes, L.N.; Olsen, I.; Dewhirst, F.E. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5721–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revest, M.; Egmann, G.; Cattoir, V.; Tattevin, P. HACEK endocarditis: State-of-the-art. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Lamont, R.J. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: The polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2012, 27, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggard, M.A.; Shugarman, L.R.; Suttorp, M.; Maglione, M.; Sugerman, H.J.; Livingston, E.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Li, Z.; Mojica, W.A.; Hilton, L.; et al. Meta-analysis: Surgical treatment of obesity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.K.; Tremaroli, V.; Clemmensen, C.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Myronovych, A.; Karns, R.; Wilson-Perez, H.E.; Sandoval, D.A.; Kohli, R.; Backhed, F.; et al. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature 2014, 509, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, M.; Chapple, I.L.; Hannig, M.; Marsh, P.D.; Meuric, V.; Pedersen, A.M.; Tonetti, M.S.; Wade, W.G.; Zaura, E. The oral microbiome—An update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.A.; Morgan, X.C.; Segata, N.; Waldron, L.; Reyes, J.; Earl, A.M.; Giannoukos, G.; Boylan, M.R.; Ciulla, D.; Gevers, D.; et al. Relating the metatranscriptome and metagenome of the human gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2329–E2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguoma, V.M.; Coffee, N.T.; Alsharrah, S.; Abu-Farha, M.; Al-Refaei, F.H.; Al-Mulla, F.; Daniel, M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity, and associations with socio-demographic factors in Kuwait. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślebioda, Z.; Rangé, H.; Strózik-Wieczorek, M.; Wyganowska, M.L. Potential Shifts in the Oral Microbiome Induced by Bariatric Surgery—A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dame-Teixeira, N.; de Lima, A.K.A.; Do, T.; Stefani, C.M. Meta-Analysis Using NGS Data: The Veillonella Species in Dental Caries. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 770917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ning, J.; Wu, L.; Jian, L.; Wu, H.; Cheng, X. Veillonella parvula promotes root caries development through interactions with Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, S.; Kolenbrander, P.E. Central role of the early colonizer Veillonella sp. in establishing multispecies biofilm communities with initial, middle, and late colonizers of enamel. J Bacteriol. 2010, 12, 2965–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, Y.; Takeshita, T. The oral microbiome and human health. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 59, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belstrøm, D. The salivary microbiota in health and disease. J. Oral Microbiol. 2020, 12, 1723975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.