Abstract

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and biofilm-associated infections represent a major global health concern, particularly in the context of medical devices such as catheters, tubing, and blood sampling devices. Biofilms, responsible for up to 85% of human infections, confer a high level of microbial resistance and compromise device performance and patient safety. In this study, the antibiofilm potential of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) essential oil was investigated through an in vitro assay. GC–MS analysis revealed eugenol (72.77%) as the predominant compound, accompanied by β-caryophyllene (14.72%) and carvacrol (2.09%). The essential oil exhibited notable antimicrobial activity, producing inhibition zones of 30.5 ± 4.5 mm against Staphylococcus aureus, 24.5 ± 0.5 mm against Micrococcus luteus, 16.0 ± 2.0 mm against Escherichia coli, 13.0 ± 1.0 mm against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 23.5 ± 1.5 mm against Candida albicans, and 24.0 ± 2.0 mm against C. glabrata. A marked reduction in biofilm biomass observed on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) surfaces. The application of clove essential oil as a coating for PVC-based medical devices remains a future possibility that requires formulation and in vivo testing. This strategy is proposed as potentially eco-safe, although environmental toxicity and biocompatibility have not yet been evaluated. It could contribute to the prevention of biofilm formation in arterial sampling systems and other healthcare-related materials, thereby enhancing device safety and longevity.

1. Introduction

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens represent a major global health challenge, highlighting the urgent need for novel antimicrobial agents that are both effective and safe for human use. Their pathogenicity relies on multiple virulence mechanisms such as surface hydrophobicity, hemolysin production, and, most critically, biofilm formation, which together enhance tissue invasion and enable immune system evasion [1]. Biofilm formation typically proceeds through distinct stages, beginning with microbial adhesion to a surface, followed by maturation into a structured community encased in an extracellular polymeric matrix, and culminating in cell dispersion that enables colonization of new sites. While bacterial and fungal biofilms share this general architecture, fungal biofilms, such as those formed by Candida species, are often thicker, with a more complex hyphal network and higher resistance to antifungal agents. These mechanisms are particularly problematic in healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), which remain a central concern in modern medicine. Device-associated infections account for 50–70% of all HAIs and are strongly linked to biofilm development on artificial surfaces [2]. Indeed, biofilms are estimated to play a role in up to 85% of human infections [3]. By embedding microorganisms within a protective matrix, they confer resistance up to 1000-fold higher than planktonic forms, thereby limiting the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy and complicating disinfection strategies. In light of these limitations, attention has increasingly turned toward natural alternatives such as essential oils (EOs). Defined by the European Pharmacopoeia as complex mixtures obtained by distillation or mechanical processes from plant material, EOs are rich in volatile secondary metabolites that display broad-spectrum antimicrobial, antiviral, and antifungal activities [4]. Unlike conventional antibiotics that generally act on a single target, EOs exert multifactorial effects, disrupting several cellular processes simultaneously. This polypharmacological action substantially reduces the likelihood of resistance development [5,6]. Among the most promising EOs, clove oil (Syzygium aromaticum) has received particular interest due to its high content of eugenol (70–95%), a phenolic compound with well-documented antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties. Eugenol was found to inhibit biofilm formation against clinically relevant pathogens such as Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and to inhibit quorum sensing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [7]. Its multi-target mechanism is reinforced by synergistic contributions from other oil constituents, including β-caryophyllene, eugenol acetate, and various monoterpenes, which further enhance its bioactivity [8]. Nevertheless, a critical limitation of current research lies in the variability of EO chemical composition, influenced by botanical origin, plant part used, cultivation conditions, and extraction techniques. This heterogeneity contributes to discrepancies across studies and complicates reproducibility. Moreover, although the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of clove oil and eugenol are well established, their effects on inert medical materials such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a material widely used in hospital devices, remain poorly explored. Direct comparative assessments across Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and yeasts under identical experimental conditions are also still scarce. To bridge this gap, the present study investigates the antibiofilm potential of clove essential oil through an in vitro approach on PVC surfaces colonized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli, C. albicans, and C. glabrata. The antibacterial and antifungal properties of clove essential oil are largely attributed to its major constituent, eugenol, whose structure and reactivity underpin its bioactivity [9]. Chemically, eugenol is a phenolic compound with an aromatic ring substituted by a hydroxyl group and an allyl chain, conferring both hydrophobic and reactive properties that promote membrane penetration.

Unlike conventional antibiotics that target a single cellular process, eugenol exerts a multifactorial mechanism of action. Its lipophilic nature enables it to integrate into microbial membranes, leading to structural disorganization, ion leakage, loss of membrane potential, and metabolic collapse, resulting in cell death. Ribeiro et al. demonstrated a rapid membrane disintegration of Staphylococcus aureus exposed to eugenol, with ATP leakage and global metabolic disruption [10]. Similarly, Chen et al. observed membrane rupture in Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to carbapenems, associated with increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) [11].

In addition, eugenol interferes with quorum sensing, the bacterial communication system regulating biofilm formation. A study published in Frontiers in Pharmacology demonstrated that eugenol inhibited quorum-sensing signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, preventing the formation of mature biofilms [12]. Eugenol also weakens the extracellular polymeric matrix, reducing exopolysaccharide synthesis, extracellular DNA accumulation, and matrix protein content [11,12]. Furthermore, eugenol-based nanoemulsions have been shown to reduce extracellular polymer production and interfere with bacterial signaling in Listeria monocytogenes, confirming its multi-target antibiofilm activity [13].

Touati et al. synthesized these findings in a comprehensive review, highlighting that essential oils, including eugenol, act through multiple pathways, primarily via biofilm matrix destabilization [14]. At higher concentrations, eugenol induces oxidative stress by generating ROS, leading to DNA and protein oxidation, organelle dysfunction, and cell cycle arrest in pathogenic yeasts [15].

A promising strategy to combat bacterial infections focuses on targeting bacterial ultra-structures or metabolites essential for pathogenicity. These include secretion systems, specialized membrane components, siderophores, and quorum-sensing molecules. By disrupting these targets, bacterial virulence can be reduced without killing the bacteria, minimizing selective pressure for resistance and complementing traditional antibiotic therapies [16].

Antibiotic resistance has emerged as a major global health problem, particularly in Gram-negative bacteria, which often harbor multiple resistance mechanisms that render most major drug classes ineffective. Novel approaches are urgently needed, yet the development of entirely new agents faces significant challenges. A potential solution is to adapt existing antibiotics by chemically linking them to siderophores—iron-chelating molecules that exploit bacteria’s innate need for iron. This “Trojan Horse” approach allows the antibiotic to gain entry into the bacterial cell, potentially overcoming resistance, curent developments and applications of this strategy are increasingly being explored [17]. For instance, the review published by Ribeiro et al. details how polymer-based nanomaterials optimize targeted drug delivery and maintains effective antimicrobial concentrations, thus opening new perspectives for controlling biofilms and multidrug-resistant bacteria [18]. In continuity with earlier studies working on incorporation of clove essential oil or its major component, eugenol, on PVC surfaces and reduce microbial adhesion [19,20], this study aims to evaluate the antibiofilm potential of clove essential oil emulsions when in contact with PVC surfaces, as a preliminary step toward the development of functional coatings for medical devices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Extraction of Essential Oil

Dried flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) were purchased from a local herbalist in Oujda-Morocco, clove plants are locally cultivated in Oujda-Morocco as well. Essential oil was extracted by hydrodistillation using a modified Clevenger-type apparatus. Approximately 100 g of clove buds were placed in a round-bottom flask containing 1 L of distilled water. The hydro distillation process was carried out for three hours under gentle boiling. The obtained essential oil was separated from the aqueous phase, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and stored in amber glass vials, tightly sealed, protected from light, and kept at 4 °C until use.

The extraction yield was calculated as a percentage (v/w) relative to the initial dry weight (at 25 ± 2 °C, with a relative humidity of approximately 50–55%) of plant material. To prevent alteration of volatile constituents, all manipulations were performed at room temperature in an environment protected from direct light.

2.2. Identification of Volatile Compounds by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

A gas chromatograph coupled with a mass spectrometer was used to identify and separate the compounds of the Syzygium aromaticum essential oil. The specific system used was a Shimadzu GC with a QP2010 MS (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The capillary column utilized was a BPX25 (SGE Analytical Science, Victoria, Australia), which was coated with 95% dimethyl diphenylpolysiloxane. This column had a length of 30 m, an internal diameter of 0.25 mm, and a film thickness of 0.25 μm. Pure helium with a purity of 99.99% was used as the carrier gas, and it maintained a constant flow rate of 3 mL per minute. The experimental conditions were as follows: the injection temperature, ion source temperature, and interface temperature were all set at 250 °C. The column oven remained at a temperature of 50 °C for 1 min at the beginning. The sample components were ionized by electron impact (EI) at 70 eV. The mass of the ions was analyzed within the range of 40–300 m/z. The essential oil samples were introduced into the chamber at a volume of 1 µL and diluted with an appropriate solvent. Then, 1 μL of the prepared essential oil was injected into the system using the split mode, with a split ratio of 90:1. Three evaluations were conducted for each sample to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results. The identification of the compounds in the EO was accomplished by comparing their retention times and mass spectra with standards and references available in the NIST database. Finally, the Laboratory Solutions software (v2.5) was employed to collect and analyze the data.

2.3. Antioxidant Activity Protocol

The antioxidant potential of EO was assessed using two complementary methods: Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) and the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay. In both tests, ascorbic acid served as the reference antioxidant. All concentrations were analyzed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

For the DPPH assay, a methanolic DPPH solution was prepared at a concentration of 0.1 mM. EO samples were tested at concentrations of 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, and 1 mg/mL. Each reaction mixture was prepared by combining 2.5 mL of DPPH solution with 0.5 mL of the EO sample at the desired concentration. After incubation in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, absorbance was measured at 517 nm against a blank [21,22]. Ascorbic acid was included as the positive control [23]. The total antioxidant capacity of EO was determined using the phosphor-molybdenum methodology as described in reference [24,25]. According to this technique, the sample extract/standard solution was mixed with a reagent solution containing 0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate. The mixture was then incubated at 95 °C for 90 min and subsequently cooled to room temperature. The absorbance of the resultant solution was measured at 695 nm, and the results were expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents using a standard curve established with ascorbic acid [26]. A blank solution, containing all reagents except the test sample, was included in the experiments, which were performed in triplicate to ensure precision and repeatability of the results.

2.4. Tested Microorganisms

A panel of microorganisms representative of the species most frequently involved in medical device-associated infections was selected to evaluate the antibiofilm activity of clove essential oil. The panel included: Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC® 6538PTM, Micrococcus luteus 14110), Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli ATCC® 10536TM and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC® 15442TM) and yeasts (Candida albicans and Candida glabrata). The strains were maintained at the Bioresources, Biotechnology, Ethnopharmacology and health Laboratory of the Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed Premier University, Oujda.

Bacteria were cultured in Mueller-Hinton broth at 37 °C for 18 to 24 h, while yeasts were incubated in Sabouraud broth (Biokar Diagnostics, Paris, France) at 25 °C for 24 h. After incubation, cell suspensions were adjusted to an optical density of 0.5 on the McFarland scale, corresponding to approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL.

These microbial suspensions were subsequently used for biofilm formation, inhibition, and eradication assays. All manipulations were carried out under strict aseptic conditions. Each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and reliability of the results.

- -

- Staphylococcus aureus ATCC® 6538PTM

- -

- Escherichia coli ATCC® 10536TM

- -

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC® 15442TM

- -

- Micrococcus luteus 14110

- -

- Candida albicans

- -

- Candida glabrata

The antimicrobial activity of the EO was assessed using a modified version of Joshi et al.’s method [27]. Our study involved evaluating the inhibitory effects of the EO on various microbial strains obtained from the Laboratory of Microbial Biotechnology at the Mohamed First University in Oujda, Morrocco. The microbial strains tested included two Gram-positive bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Micrococcus luteus (LB 14110) as well as two Gram-negative bacteria; Escherichia Coli (ATCC 10536), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 15442). Additionally, Candida glabrata and Candida albicans were also included in the protocol. For the bacteria, Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) was used as the growth medium, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. On the other hand, potato dextrose agar (PDA) was used for the yeast strains, which were incubated at 25 °C for 48 h. By conducting the experiments under these conditions, we were able to identify the efficacy of the EO in inhibiting the growth of the tested microorganisms. Prior to the EO assays, the concentrations of the bacterial and fungal strains were standardized. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to approximately 106 cells/mL, based on optical density measurements at 600 nm performed with a UV–visible spectrophotometer. To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the EO, the well diffusion method described by Joshi et al. [27] was employed. 100 µL of EO per well for test. As a negative control, DMSO was used. Additionally, as positive controls for bacterial and Yeasts strains, respectively, gentamicin and cycloheximide (both obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used. Petri dishes remained at 4 °C for 15–30 min then are incubated in an oven 18 h. The estimate of the antibacterial activity is achieved by measuring the clear zones (halos) in mm which form around the wells using a caliper. A product is considered active if the diameter of the inhibition zone is greater than 8 mm.

2.4.1. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

To evaluate the antibacterial potential of clove essential oil, its minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using the broth microdilution technique in sterile 96-well microplates. The procedure was carried out according to the methods described by Remmal et al. [28] and Yahyaoui et al. [29]. Serial two-fold dilutions of the EO (16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625, 0.0315, 0.0156% v/v) were prepared in Mueller–Hinton broth supplemented with 0.15% agar to ensure homogeneous dispersion of the oil with a final volume of 200 µL per well [30]. Each well was inoculated with a standardized bacterial suspension adjusted to approximately 106 CFU/mL.

The microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under static conditions. Subsequently, 15 μL of resazurin solution (0.015%) was added to each well as a colorimetric growth indicator, and the plates were further incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The MIC was defined as the lowest EO concentration that prevented the resazurin color shift from blue to pink, thus indicating complete inhibition of microbial growth. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the results.

2.4.2. Biofilm Formation and Disruption Assay

- -

- Mature Biofilm Disruption Test.

The following step was designed to evaluate the ability of clove essential oil to disrupt pre-formed and stabilized biofilms on abiotic surfaces. The protocol was adapted from the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, M26-A) and the methodology described by Douichi et al. [31].

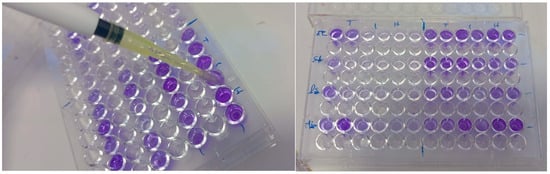

Microbial strains were inoculated into sterile 96-well (Figure 1) flat-bottom microtiter plates (Nunc™, Thermo Scientific™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), each well containing 100 μL of a standardized microbial suspension prepared in media optimized for adhesion: Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) supplemented with 1% glucose for bacterial strains, Sabouraud broth supplemented with 1% glucose for yeast strains. The plates were incubated under static conditions for 24 h at 37 °C (or 30 °C for yeasts) to allow stable biofilm formation. Following incubation, wells were gently washed three times with sterile distilled water to remove non-adherent planktonic cells, leaving only the established biofilm attached to the well surface.

Figure 1.

Biofilm formation assay in 96-well microplates (T: Without EO, H: With EO).

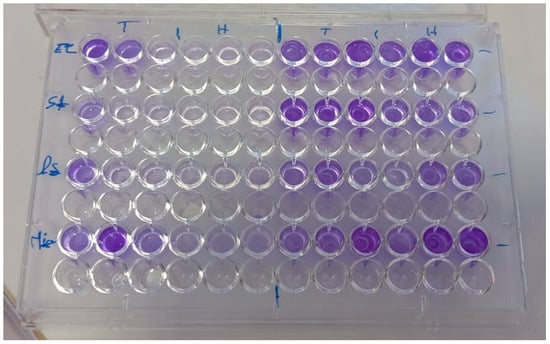

After the removal of planktonic cells, 100 μL of clove essential oil, diluted in 1% Tween 80 (to ensure homogeneity), was added at concentrations ranging from 0.125% to 2% (v/v) in fresh medium [32]. The plates were then incubated again for 24 h under the same conditions. Following incubation, the wells were gently washed with sterile distilled water to remove residual compounds, and the remaining biofilm biomass was quantified using crystal violet staining (Figure 2), as described in standard protocols [32].

Figure 2.

Treatment of pre-formed biofilms with clove essential oil and quantification by crystal violet staining (T: Without EO, H: With EO).

Absorbance measurements at 570 nm, obtained after crystal violet staining, were used to evaluate the ability of clove essential oil to inhibit biofilm formation in different microbial strains.

- -

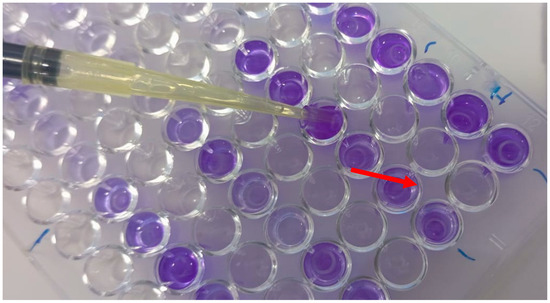

- Assessment of Biofilm Formation on PVC Microplates (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Biofilm formation assay on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coupons placed in 96-well microplates and stained with crystal violet for biomass quantification. The arrow indicates the position of the PVC coupon placed at the bottom of each well. After incubation with microbial suspensions and treatment with various concentrations of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil, residual biofilm biomass was visualized by 1% crystal violet staining. The intensity of the purple coloration reflects the density of the adherent biofilm on the PVC surface, with lighter wells corresponding to greater antibiofilm activity of the essential oil.

Figure 3. Biofilm formation assay on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coupons placed in 96-well microplates and stained with crystal violet for biomass quantification. The arrow indicates the position of the PVC coupon placed at the bottom of each well. After incubation with microbial suspensions and treatment with various concentrations of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil, residual biofilm biomass was visualized by 1% crystal violet staining. The intensity of the purple coloration reflects the density of the adherent biofilm on the PVC surface, with lighter wells corresponding to greater antibiofilm activity of the essential oil.

Twelve-hour cultures of each strain were grown in TSB and then transferred into 10 mL of fresh TSB, mixed, and dispensed (100 µL per well, approximately 108 CFU/mL) into 96-well microplates made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) (Thermo Lab Systems, Helsinki, Finland, Cat. No. 95096), as described by Djordjevic et al. [33] Eight wells contained sterile TSB as negative controls, and eight wells were inoculated with the test strain, serving as positive controls.

The duplicate plates were incubated at 37 °C for bacteria and 25 °C for yeasts for 24 and 48 h, respectively. The essential oil was added to each well at different concentrations together with the standardized microbial suspension prior to incubation, in order to evaluate its effect on biofilm formation. Control wells containing only the culture medium without essential oil were used as negative controls. After incubation, wells were washed five times with 150 µL of distilled water to remove loosely attached cells. Following washing, PVC coupons remained in the original wells and plates were air-dried for 45 min. Coupons were then stained in situ with 150 µL of 1% crystal violet in water for 45 min. A second series of five washes with distilled water was performed to remove excess dye. Subsequently, 200 µL of 95% ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the stain. Then, 100 µL from each well was transferred to a corresponding well of a new microtiter plate, and absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The absorbance of the control wells (TSB) was determined and subtracted from that of the inoculated wells to quantify biofilm formation. The inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

2.5. Antibiofilm Effect of Clove Essential Oil on PVC Surfaces

To evaluate the antibiofilm efficacy of clove essential oil on materials representative of medical devices, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coupons were used as the experimental substrate. This polymer is commonly found in invasive devices (tubing, catheters, probes) and provides a surface conducive to biofilm formation, particularly in hospital settings.

PVC coupons (1.0 × 1.0 × 0.1 cm) were manually cut, washed with soapy water, rinsed with sterile distilled water, and then immersed in 70% ethanol for 30 min before air-drying under a sterile hood. The preparation method was adapted from Kunicka-Styczyńska et al. [34]. Each coupon was placed at the bottom of a well in a 96-well microplate containing 1 mL of a standardized microbial suspension (1 × 108 CFU/mL) of one of the tested strains (see above) prepared in MH (for Bacteria) and Sabouraud (for yeast). Plates were incubated at 37 °C/25 °C for 24 h under static conditions to allow initial biofilm formation.

Following this phase, coupons were gently washed with sterile PBS to remove planktonic cells. Different concentrations of clove essential oil (0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%) were then applied to determine the minimal biofilm inhibitory concentration on PVC (MIC-biofilm-PVC), following a procedure analogous to microtiter plate assays.

Coupons were re-incubated at 37 °C/25 °C for 24 h, washed three times with PBS, fixed at 60 °C for 1 h, and then stained with 0.4% crystal violet for 15 min. After rinsing, each coupon was transferred to a new, clean 96-well plate for dye extraction. The retained dye was solubilized in 200 µL of 95% ethanol, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Positive controls (0.2% chlorhexidine treatment) and negative controls (untreated biofilm, solvent-only treatment) were included to validate the results. The MIC-biofilm-PVC was defined as the lowest concentration of essential oil, reducing biofilm density by more than 50% compared to the negative control, all experiments were performed in triplicate.

This approach allowed for a more physiologically relevant assessment of the antibiofilm activity of clove essential oil on solid surfaces, mimicking real-world exposure conditions of medical devices in clinical settings (Figure 3).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine significant differences between the clove essential oil and the control treatments. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GC Analysis of Essential Oil Components Syzygium aromaticum

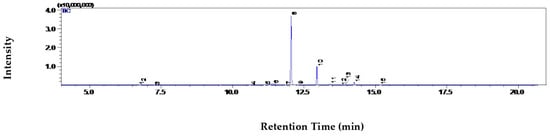

The extraction yield of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil was 7.8 ± 0.2% (v/w), and was found to contain 15 constituents (Table 1) (Figure 4), composed of 15 identified constituents, which together represent the entire chemical profile of the oil. This sample was predominantly composed of eugenol (72.77%), a phenolic compound widely recognized for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, and the major bioactive constituent of clove oil, widely recognized for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties. Other notable components included caryophyllene (16.58%), a sesquiterpene with anti-inflammatory potential, and carvacrol (2.09%), a monoterpenoid known for its antimicrobial effects. Minor compounds such as thymol (0.68%) and chavicol (0.46%) were also detected, suggesting possible chemotaxonomic affinities with aromatic plants from the Lamiaceae family (e.g., thyme or basil).

Table 1.

GC–MS analysis of the chemical compounds of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil.

Figure 4.

GC–MS chromatogram of S. aromaticum essential oil.

In a recent study conducted in Saudi Arabia, Abdelmuhsin et al., reported a more complex chemical profile, identifying 21 compounds in S. aromaticum essential oil by GC–MS analysis. The major constituents in their sample were eugenol (58.86%), caryophyllene (14.72%), phenol (9.60%), humulene (3.62%), and eugenyl acetate (3.13%), and confirming eugenol as the dominant component but also highlighting regional variability in secondary metabolite composition [35].

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

In this study, the antioxidant potential of clove EO (Syzygium aromaticum) was assessed using both the DPPH radical scavenging assay and the Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) test, with ascorbic acid serving as the reference standard (Table 2). The clove oil exhibited moderate antioxidant activity, with an IC50 value of 3.259 ± 0.035 mg/mL, indicating a substantial, but not maximal, ability to neutralize free radicals. This activity is primarily attributed to eugenol, the main bioactive phenolic compound in clove oil, known for its strong hydrogen-donating and radical-stabilizing properties, although other minor constituents may also contribute to the overall effect.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of the essential oils studied using the DPPH and TAC assays.

These results are consistent with previous findings by Chaieb et al. [36] who reported that the antioxidant capacity of clove oil can vary depending on the plant’s geographical origin and chemical composition, while eugenol consistently remains its dominant constituent. Such variations underline the influence of environmental and extraction factors on the oil’s bioactivity.

Although clove oil did not exhibit the highest antioxidant performance among the samples tested, its relatively low IC50 value confirms a notable free-radical scavenging potential, making it a promising candidate for natural antioxidant applications in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food preservation formulations. These results thus highlight the important role of eugenol as a key contributor to the overall antioxidant efficacy of clove essential oil, while acknowledging the possible synergistic effects of other compounds present.

3.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The determination of the MIC is a crucial step in assessing the potential applications of essential oils in health, agriculture, and the agri-food sector. A key aspect of this evaluation lies in establishing both the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) parameters that are essential for gauging their effectiveness as antibacterial agents.

The results presented in Table 3 clearly demonstrate the significant inhibitory activity of clove essential oil against all tested bacterial strains, including Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Micrococcus luteus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Table 3). These findings suggest that clove essential oil (Syzygium aromaticum) exhibits promising antibacterial activity across a broad spectrum of pathogenic microorganisms, highlighting its potential as a natural agent in the fight against antibiotic-resistant infections.

Table 3.

Inhibitory effect (inhibition zone in mm and MIC in %) of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil on reference microbial strains.

Our experimental results, showing the progressive increase in absorbance in wells, indicated a dose-dependent antibiofilm response, with inhibition decreasing at lower concentrations. These observations align with those of El Abed et al. who reported that eugenol exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm, with up to >90% reduction at higher-doses [37], and with Biernasiuk et al. [38] who observed complete inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm at 0.2%, associated with structural disorganization under electron microscopy. Similarly, Kim et al. demonstrated optimal inhibition of E. coli O157:H7 biofilm at 0.005% (v/v), beyond which the effect declined [7].

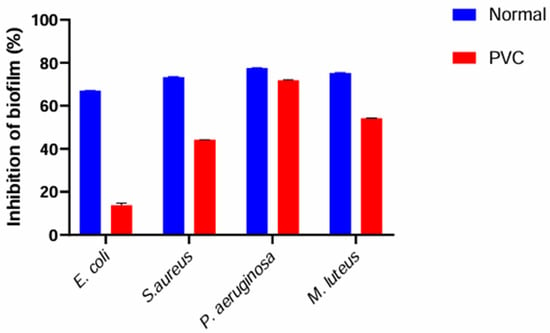

3.4. Assessment of Biofilm Formation and Disruption Assay

In this experiment, the concentrations used correspond to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) previously determined for each bacterial strain. These MIC-based doses were applied to evaluate the antibiofilm activity of the essential oil under standardized and comparable inhibitory conditions. These results demonstrate a significant reduction in biofilm biomass under certain conditions, indicating a clear dose-dependent inhibitory effect of the essential oil on biofilm formation (Figure 5). The lowest absorbance values, such as those recorded in wells, reflect strong inhibition of both cell adhesion and extracellular matrix production, which are key steps in biofilm development. Among the tested strains, E. coli showed the highest susceptibility to the essential oil, showing minimal biofilm formation even at low EO concentrations (0.05%). P. aeruginosa demonstrated an intermediate response, retaining partial biofilm activity at 0.016% EO, suggesting a moderate level of tolerance. In contrast, M. luteus was the least affected, maintaining a high mean absorbance value (0.697) at 0.5% EO, which reflects a pronounced resistance to the antibiofilm activity of the essential oil.

Figure 5.

Quantification of biofilm biomass by crystal violet staining in 96-well microplates (OD 595 nm) after exposure to increasing concentrations of clove EO (Normal: Control, PVC: Test on PVC).

Taken together, these results confirm the antibiofilm potential of clove essential oil, while highlighting a clear strain-dependent gradient of susceptibility, ranging from highly sensitive (E. coli) to strongly resistant (M. luteus).

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the preliminary antibiofilm potential of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) essential oil, primarily attributed to its high eugenol content, against the specific bacterial and yeast strains evaluated in this work. The observed inhibitory effect on biofilm formation in microtiter plate assays provides initial evidence supporting its potential for surface-coating applications. However, these results are limited to the tested strains and do not include assessments of toxicity, allergenicity, long-term stability, or biocompatibility under clinical conditions. Extrapolation to medical devices, including PVC tubing or sensors used arterial sampling devices remains speculative and requires further investigation. Future studies should focus on in vivo evaluation, toxicological assessments, formulation development for coatings, and testing in more complex or clinically relevant models to confirm safety and efficacy. In parallel, evaluating the antibiofilm activity of pure eugenol will be essential to determine its specific contribution as the principal active component.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M. and M.I.Y.; methodology, I.M. and M.I.Y.; validation, I.M. and M.I.Y.; formal analysis, I.M. and M.I.Y.; investigation, I.M. and M.I.Y.; resources, A.A. and A.D. and B.H.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M. and A.A. and A.D.; supervision, A.A., B.H. and H.B.; project administration, I.M. and B.H. and H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the technical support provided by the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care at Mohammed VI University Hospital, Oujda, Morocco, and the Microbiology Laboratory of the Faculty of Sciences of Oujda (FSO) for their valuable assistance during the experimental procedures. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) for language refinement and formatting purposes. The author reviewed and edited all generated content and takes full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jafri, H.; Ahmad, I. In Vitro Efficacy of Clove Oil and Eugenol against Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus mutans on Hydrophobicity, Hemolysin Production and Biofilms and their Synergy with Antibiotics. Adv. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.M.; Teixeira-Santos, R.; Mergulhão, F.J.M.; Gomes, L.C. The Use of Probiotics to Fight Biofilms in Medical Devices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuță, D.C.; Limban, C.; Chiriță, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Costea, T.; Ioniță, P.; Nicolau, I.; Zarafu, I. Contribution of Essential Oils to the Fight against Microbial Biofilms—A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Essential Oils (Monograph 01/2021:2098); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pulingam, T.; Parumasivam, T.; Gazzali, A.M.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Chee, J.Y.; Lakshmanan, M.; Chin, C.F.; Sudesh, K. Antimicrobial resistance: Prevalence, economic burden, mechanisms of resistance and strategies to overcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 170, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyfa, A.; Kunicka-Styczyńska, A.; Molska, M.; Gruska, R.M.; Baryga, A. Clove, Cinnamon, and Peppermint Essential Oils as Antibiofilm Agents Against Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. Molecules 2025, 30, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; Gwon, G.; Kim, S.-I.; Park, J.G.; Lee, J. Essential Oils and Eugenols Inhibit Biofilm Formation and the Virulence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassolé, I.H.N.; Juliani, H.R. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules 2012, 17, 3989–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Nandi, S.; Basu, T. Nano-antibacterials using medicinal plant components: An overview. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 768739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.A.N.; dos Santos, G.A.; dos Santos, C.T.; Soares, D.C.F.; Saraiva, M.F.; Leal, D.H.S.; Sachs, D. Eugenol as a promising antibiofilm and anti-quorum sensing agent: A systematic review. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 196, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T. From quorum sensing inhibition to antimicrobial defense: The dual role of eugenol-gold nanoparticles against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 247, 114415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariati, A.; Noei, M.; Askarinia, M.; Khoshbayan, A.; Farahani, A.; Chegini, Z. Inhibitory effect of natural compounds on quorum sensing system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A helpful promise for managing biofilm community. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1350391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Xue, J.; Luo, Y.; Upadhyay, A. Eugenol nanoemulsion reduces Listeria monocytogenes biofilm by modulating motility, quorum sensing, and biofilm architecture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1272373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, A.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T. Essential oils for biofilm control: Mechanisms, synergies, and translational challenges in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahina, Z.; Dahms, T.E.S. A comparative review of eugenol and citral anticandidal mechanisms: Partners in crimes against fungi. Molecules 2024, 29, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeddine, Z.; Ghssein, G. Towards new antibiotics classes targeting bacterial metallophores. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillotson, G.S. Trojan Horse Antibiotics–A Novel Way to Circumvent Gram-Negative Bacterial Resistance? Infect. Dis. Res. Treat. 2016, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.R.M.; Teixeira, M.O.; Marinho, E.; Silva, A.F.G.; Costa, S.P.G.; Felgueiras, H.P. Polymer-Based Nanomaterials Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. In Nanotechnology Based Strategies for Combating Antimicrobial Resistance; Wani, M.Y., Wani, I.A., Rai, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M.; Tamer, T.M.; El Monem, A.; Elmoaty, S.A.; El Fatah, M.A.; Saad, G.R. Development of PVC membranes with clove oil as plasticizer for blood bag applications. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicka-Styczyńska, A.; Tyfa, A.; Laskowski, D.; Plucińska, A.; Rajkowska, K.; Kowal, K. Clove Oil (Syzygium aromaticum L.) Activity against Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris Biofilm on Technical Surfaces. Molecules 2020, 25, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, P.; Pineda, M.; Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: Specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 269, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Chandrashekar, K.S.; Pai, K.S.R.; Setty, M.M.; Devkar, R.A.; Reddy, N.D.; Shoja, M.H. Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of extract and fractions of Nardostachys jatamansi DC in breast carcinoma. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taibi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Ouahhoud, S.; Loukili, E.H.; Ou-Yahya, D.; Ouahabi, S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Noman, O.M.; Addi, M.; Bellaouchi, R.; et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity of Ptychotis verticillata essential oil: Towards novel breast cancer therapeutics. Life 2023, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbouzidi, A.; Taibi, M.; Ouassou, H.; Ouahhoud, S.; Ou-Yahia, D.; Loukili, E.H.; Aherkou, M.; Mansouri, F.; Bencheikh, N.; Laaraj, S.; et al. Exploring the multi-faceted potential of carob (Ceratonia siliqua var. Rahma) leaves from Morocco: Polyphenols profile, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Dalli, M.; Azizi, S.-E.; Aherkou, M.; Taibi, M.; El Guerrouj, B.; Addi, M.; Gseyra, N. Phytochemical, antioxidant, and anticancer assessments of Atriplex halimus extracts: In silico and in vitro studies. Sci. Afr. 2023, 22, e01959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, S.G.; Tusevski, O.; Maury, S.; Delaunay, A.; Joseph, C.; Hagège, D. Effects of polysaccharide elicitors on secondary metabolite production and antioxidant response in Hypericum perforatum L. shoot cultures. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 609649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Kumar, V.; Chandra, B.; Kandpal, N. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil of Senecio graciliflorus. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmal, A.; Bouchikhi, T.; Rhayour, K.; Ettayebi, M.; Tantaoui-Elaraki, A. Improved method for the determination of antimicrobial activity of essential oils in agar medium. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1993, 5, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaoui, M.I.; Bentouhami, N.E.; Moumnassi, S.; Elbouzidi, A.; Taibi, M.; Berraaouan, D.; Bellaouchi, R.; Jaouadi, B.; Abousalham, A.; Saalaoui, E.; et al. Effect of xylooligosaccharides on the metabolic activity of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum S61: Production of bioactive metabolites with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Bacteria 2025, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, M.; El Hachlafi, N.; Fadil, M.; Benkhaira, N.; Jeddi, S.; Benziane Ouaritini, Z.; Fikri-Benbrahim, K. Combination of Chemically-Characterized Essential Oils from Eucalyptus polybractea, Ormenis mixta, and Lavandula burnatii: Optimization of a New Complete Antibacterial Formulation Using Simplex-Centroid Mixture Design. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 2023, 5593350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diouchi, J.; Marinković, J.; Nemoda, M.; El Rhaffari, L.; Toure, B.; Ghoul, S. In Vitro Methods for Assessing the Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Properties of Essential Oils as Potential Root Canal Irrigants—A Simplified Description of the Technical Steps. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogman, M.E.; Vuorela, P.M.; Fallarero, A. Combining biofilm matrix measurements with biomass and viability assays in susceptibility assessments of antimicrobials against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, D.; Wiedmann, M.; McLandsborough, L.A. Microtiter plate assay for assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2950–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicka-Styczyńska, A.; Sikora, M.; Kalemba, D. Antibiofilm activity of selected essential oils and their major components. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmuhsin, A.; Elhadi Sulieman, A.M.; Salih, Z.A.; Al-Azmi, M.; Alanaizi, N.A.; Goniem, A.E.; Alam, M.J. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) Pods: Revealing Their Antioxidant Potential via GC–MS Analysis and Computational Insights. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, K.; Hajlaoui, H.; Zmantar, T.; Nakbi, A.; Rouabhia, M.; Kacem, M.; Bakhrouf, A. The Chemical composition and biological activity of clove essential oil, Eugenia caryophyllata (Syzigium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): A short review. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Abed, S.; Houari, A.; Latrache, H.; Remmal, A.; Koraichi, S.I. In vitro activity of Four Common Essential Oil Components Against Biofilm-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Res. J. Microbiol. 2011, 6, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernasiuk, A.; Baj, T.; Malm, A. Clove essential oil and its main constituent, eugenol, as potential natural antifungals against Candida spp. alone or in combination with other antimycotics. Molecules 2023, 28, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).