Abstract

Enterococcus alishanensis JNUCC 77 (=BLH10) was isolated from the flowers of Zinnia elegans collected at Ilchul Land, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea. Whole-genome sequencing was conducted to clarify its taxonomic position, genomic composition, and adaptive metabolic potential. The assembled genome comprised five contigs totaling 3.86 Mb, with a G + C content of 35.6% and 100% completeness. Genome-based phylogenomic analyses using the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) confirmed that strain JNUCC 77 belongs to E. alishanensis. Functional annotation revealed enrichment of genes related to transcriptional regulation, carbohydrate metabolism, replication, and DNA repair, suggesting a lifestyle adapted to oxidative and UV-exposed floral habitats rather than pathogenic competitiveness. Genome mining with antiSMASH identified two putative biosynthetic regions associated with terpenoid and isoprenoid metabolism, which are commonly linked to redox regulation and cellular protection. These genomic features indicate that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 has evolved a metal-assisted, redox-regulated survival strategy suitable for floral microenvironments. Given its origin from vibrant flowers and its genomic potential for redox-protective metabolism, this strain represents an attractive microbial resource for future development of nature-inspired postbiotic and cosmeceutical ingredients that align with the clean and eco-friendly image of flower-derived biotechnologies.

1. Introduction

The genus Enterococcus comprises Gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic lactic acid bacteria that inhabit a wide range of ecological niches, including soil, water, plants, and animal hosts [1]. Traditionally known as intestinal commensals or fermentative organisms, several Enterococcus species have gained increasing attention for their functional bioactivities and industrial applicability [2,3]. Many strains produce bacteriocins, exopolysaccharides, and short-chain organic acids with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, supporting their use as probiotic or postbiotic resources in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. Furthermore, Enterococcus-derived extracellular vesicles and surface proteins have been reported to modulate host immune responses and enhance epithelial barrier function, expanding their utility beyond conventional probiotic roles [4,5].

Among the genus Enterococcus, E. alishanensis represents a relatively unexplored but promising species. It was first reported as a novel taxon from plant- and soil-associated environments in Taiwan by Ming Chuan University [6], and the present study provides the second whole-genome report for this species. Despite the growing recognition of Enterococcus as a valuable microbial resource, E. alishanensis remains an emerging subject of investigation with distinctive ecological and metabolic traits. Genomic and functional studies have revealed that E. alishanensis harbors genes related to oxidative stress protection, terpenoid biosynthesis, and metal-ion regulation, suggesting a redox-controlled metabolic system that facilitates survival under oxygen-variable conditions [6].

In general, Enterococcus-derived postbiotics—including organic acids and bacteriocins—have demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, supporting their potential in functional food and cosmeceutical applications such as skin barrier enhancement and redox regulation [7]. Likewise, E. faecium postbiotics exhibit antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities applicable to food preservation and therapeutic use, while heat-killed Enterococcus postbiotics show safety and efficacy in improving gut and skin health. Within this context, E. alishanensis can be regarded as a novel and underexplored member of the genus with considerable potential as a redox-regulating microbial source for future biotechnological utilization [8,9,10].

While the genus Enterococcus is often associated with host-derived niches, plant-associated Enterococcus species remain relatively underexplored. Floral microhabitats, in particular, represent unique ecological systems characterized by high ultraviolet radiation, osmotic fluctuation, diurnal temperature variation, and nutrient limitation. These stresses drive the selection of microorganisms with specialized mechanisms for ROS detoxification, membrane stabilization, and photoprotective metabolite biosynthesis. Consequently, flowers serve as natural bioreactors for discovering stress-tolerant bacteria with valuable biosynthetic capacities, especially for developing antioxidant or UV-protective bioactive compounds [11,12,13].

Jeju Island, located at the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, is a volcanic biosphere designated as a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site. Its geological and ecological diversity—ranging from basaltic soils and mineral-rich volcanic ash to subtropical flora—creates an exceptional reservoir for microbial evolution and biochemical diversification. The island’s high UV index, strong sea winds, and volcanic mineral exposure provide selective pressures that foster the emergence of microorganisms with unique stress adaptation and secondary metabolite production abilities. Thus, Jeju’s floral ecosystems represent a promising frontier for the discovery of novel microorganisms capable of producing redox-active, photoprotective, and biofunctional metabolites relevant to the cosmeceutical and biotechnology sectors [14,15].

In this context, E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 (=BLH10) was isolated from the flowers of Z. elegans. The present study provides a comprehensive genomic analysis of this strain using Illumina NovaSeq sequencing and comparative phylogenomic approaches. Specifically, we aimed to (i) determine its precise taxonomic position using the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS), (ii) evaluate its functional gene composition through COG and EggNOG annotation, and (iii) identify biosynthetic gene clusters associated with terpenoid and isoprenoid metabolism via antiSMASH. Through these genome-based analyses, we inferred potential metabolic features related to floral habitat adaptation and proposed that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 may serve as a non-pathogenic, environmentally resilient, and biofunctional microbial resource with prospective applications in postbiotic and cosmeceutical research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Cultivation

The strain was isolated from the flowers of Z. elegans collected at Ilchul Land, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea (33.382263 N, 126.841856 E) on 4 August 2023. Samples were serially diluted and plated on de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions. Colonies with distinct morphology were purified and preserved as JNUCC 77 (=BLH10) in the Jeju National University Culture Collection (JNUCC).

2.2. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Quality Assessment

Genomic DNA of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 was extracted using a Qiagen Genomic-tip 100/G kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol for Gram-positive bacteria. Whole-genome sequencing was carried out by CJ Bioscience Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (NovaSeq Control Software v1.8 and v1.5 reagent kit) with a paired-end library (350 bp insert size).

Raw reads were quality-checked and adapter-trimmed, and de novo assembly was performed using SPAdes v3.15.3 under default parameters [16]. The resulting assembly comprised five contigs with a total genome size of 3,857,120 bp, an N50 value of 2,616,578 bp, and an average sequencing coverage of approximately 275×.

Genome completeness and contamination were assessed using CheckM v1.2.2, which confirmed 100% bacterial core gene coverage, and ContEst16S analysis, which detected no contamination across the five identical 16S rRNA gene copies (100% identity to E. alishanensis ALS3T) [17,18]. The genome annotation was subsequently performed using Prokka v1.14.6 to identify coding sequences, rRNA, and tRNA genes.

This high-quality draft genome served as the basis for subsequent analyses, including phylogenomic comparison, functional annotation, and secondary metabolite gene cluster prediction.

2.3. Genome-Based Phylogenomic Analysis Using Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS)

Genome-based phylogenomic analysis of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 was conducted using the TYGS to determine its taxonomic position within the genus Enterococcus. The complete genome sequence of strain JNUCC 77 was uploaded to the TYGS platform and compared against all available type strain genomes in the DSMZ database.

Pairwise intergenomic distances were calculated using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) method under formula d5, implemented in the TYGS pipeline. The resulting intergenomic distance matrix was used to infer phylogenetic relationships via the FastME 2.1.6.1 algorithm employing the balanced minimum-evolution approach. Branch support values were computed from 100 pseudo-bootstrap replicates [19,20].

Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values were estimated using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) v3.0, integrated within the TYGS workflow, to assess genomic relatedness. For complementary validation, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) values were calculated using the OrthoANIu algorithm (CJ Bioscience Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) under default parameters [19,21].

All analyses were performed using default settings provided by the TYGS and GGDC servers, and the resulting datasets were used for the construction of a genome-based phylogenomic framework for E. alishanensis JNUCC 77.

2.4. Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) Functional Classification of the Genome

Functional annotation and COG classification of the E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 genome were performed to determine the distribution of genes associated with major metabolic and cellular processes. The annotated coding sequences (CDSs) generated by Prokka v1.14.6 were functionally assigned using EggNOG-mapper v2.1.13 with the eggNOG v6.0 database, through the analytical pipeline of CJ Bioscience Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) [22,23].

Each predicted protein was classified into one of the 22 standard COG functional categories based on its best orthologous match. Genes showing no significant homology to known orthologous groups were categorized as “S: Function unknown” or “X: Not matched to database.” The distribution of CDSs among COG categories was computed and summarized from the processed dataset provided by CJ Bioscience.

This updated orthology-based annotation provided a comprehensive overview of the functional genome architecture of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77, highlighting the major gene groups involved in metabolism, transcriptional regulation, replication, and cellular adaptation.

2.5. Prediction of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

Prediction of secondary metabolite BGCs in E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 was performed using antiSMASH v8.0.4. The annotated genome file produced by Prokka v1.14.6 was used as input in GenBank format. All extended analytical modules were activated, including ClusterFinder, KnownClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, ActiveSiteFinder, and Pfam domain annotation, under the “relaxed” detection strictness setting to ensure comprehensive identification of canonical and cryptic clusters [24,25].

Each predicted cluster was compared with the MIBiG 4.0 reference database to evaluate sequence homology and biosynthetic similarity to experimentally characterized pathways. The gene content, organization, and domain composition of the predicted clusters were manually examined through the antiSMASH integrated visualization tools, which generate gene-level schematic representations of cluster boundaries and predicted biosynthetic domains [26].

This workflow provided a reproducible in silico framework for the identification and characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters within the genome of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genomic Features

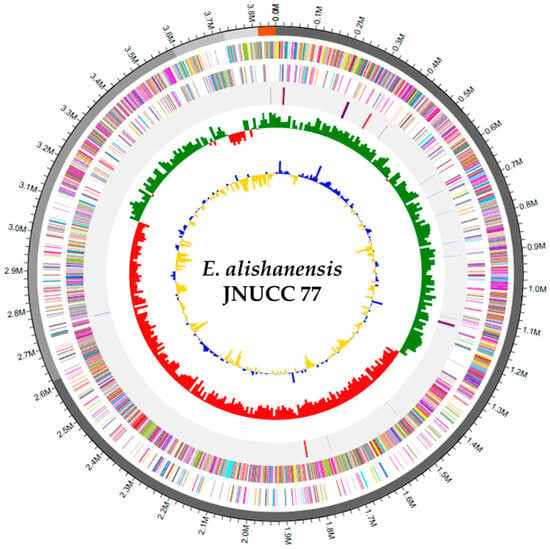

The complete genome of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 was analyzed by CJ Bioscience Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, followed by de novo assembly with SPAdes v3.15.3. The assembled genome consisted of five contigs with a total length of 3,857,120 bp, an N50 value of 2,616,578 bp, and a G + C content of 35.6% (Table 1). The largest contig measured 2,616,578 bp, consistent with a chromosomal architecture without plasmid elements. An overview of the assembled genome structure is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

General Genomic Features of Enterococcus sp. Strain JNUCC 77.

Figure 1.

Circular genome map of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77. The complete genome is visualized with annotated coding sequences on forward (red) and reverse (green) strands, GC skew (yellow/blue), and GC content variation. The map indicates a stable, plasmid-free chromosomal organization with balanced GC distribution.

A total of 3826 predicted genes were annotated, including 3826 protein-coding sequences (CDSs), 64 tRNA genes, and 15 rRNA genes (5S, 16S, and 23S). The average coding sequence length was approximately 909 bp, with a median CDS length of 765 bp. Genome quality control confirmed 100% bacterial core gene coverage and the absence of contamination, validating the high completeness and reliability of the assembly.

Overall, the genomic composition of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 reflects a compact, low-GC-content chromosome typical of the genus Enterococcus. The relatively small genome size and gene repertoire suggest functional streamlining and adaptation to nutrient-variable floral environments, providing a robust foundation for comparative and functional genomic analyses [6].

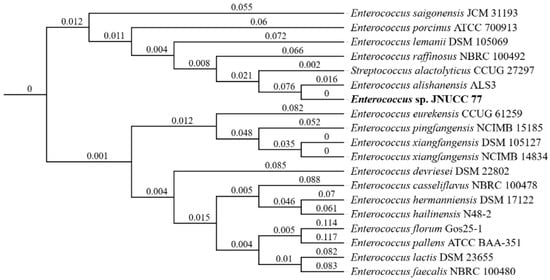

3.2. Genome-Based Phylogenomic Analysis Using TYGS

Genome-based phylogenomic analysis using the TYGS revealed that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 formed a distinct and coherent clade with the type strain E. alishanensis ALS3T, supported by short branch distances and strong bootstrap values (Figure 2). This close phylogenomic relationship clearly distinguishes JNUCC 77 from other Enterococcus species and confirms its affiliation within E. alishanensis.

Figure 2.

Phylogenomic tree of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 and related Enterococcus species based on TYGS analysis. Strain JNUCC 77 clustered closely with E. alishanensis ALS3T, forming a distinct clade supported by low branch distances, confirming its species-level affiliation.

dDDH analysis further substantiated this classification. The dDDH value between strain JNUCC 77 and E. alishanensis ALS3T was 87.9%, exceeding the conventional 70% species delineation threshold, whereas all other Enterococcus and Streptococcus type strains exhibited values below 35% (Table 2). Likewise, OrthoANIu analysis yielded a 99.39% identity between the two strains, with a coverage of approximately 65%, providing additional genomic evidence for species-level congruence (Table 3). Together, these indices demonstrate that strain JNUCC 77 represents a member of E. alishanensis, not a novel taxon.

Table 2.

Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values between E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 and closely related type strains.

Table 3.

OrthoANIu analysis between E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 and reference genomes.

This finding holds particular taxonomic and ecological significance, as E. alishanensis was previously reported only once—from plant- and soil-associated habitats in Taiwan—by Ming Chuan University. The present work thus represents the second complete genome report for this species and the first isolation from a floral microhabitat, expanding the known ecological range of E. alishanensis beyond terrestrial environments. The floral origin of strain JNUCC 77 suggests that E. alishanensis may possess adaptive genomic features enabling survival under UV exposure, osmotic stress, and oxidative conditions characteristic of flower-associated niches [27].

The TYGS-based phylogenomic resolution provides a more reliable taxonomic framework than traditional 16S rRNA gene-based classification, particularly for Enterococcus, where interspecies sequence similarity often exceeds 98%. The high ANI and dDDH values, combined with clear phylogenomic clustering, underscore the stability of species assignment and provide a genomic foundation for subsequent comparative analyses. In this context, the genome of JNUCC 77 not only confirms its taxonomic identity but also contributes to understanding the genetic diversity and ecological plasticity of E. alishanensis, a species increasingly recognized for its potential functional and industrial applications [28,29].

3.3. Functional Genome Composition

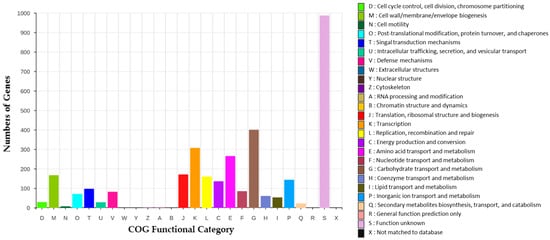

The functional categorization of the E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 genome was performed using the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) database to provide an overview of its metabolic and physiological potential. A total of 3728 coding sequences (CDSs) were assigned to 22 major COG categories, reflecting the broad genetic diversity and adaptive functions of the strain (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

COG functional classification of protein-coding genes in E. alishanensis JNUCC 77. A total of 3728 coding sequences (CDSs) were assigned to 22 major COG categories. The highest number of genes was classified as “S: Function unknown,” followed by categories related to carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, transcription, and energy production, reflecting the strain’s versatile metabolic capacity.

Among the annotated COG categories, the largest proportion of genes (approximately 950 CDSs) was classified under “S: Function unknown”, indicating a substantial pool of hypothetical or uncharacterized proteins that may represent unexplored functional potentials. Genes related to “G: Carbohydrate transport and metabolism” (around 400 CDSs), “E: Amino acid transport and metabolism”, and “K: Transcription” also accounted for significant portions of the genome, suggesting an active metabolic network capable of nutrient assimilation and environmental adaptation [30].

Moderate gene representation was observed in “C: Energy production and conversion”, “F: Nucleotide transport and metabolism”, and “M: Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis”, consistent with the physiological robustness typical of Enterococcus species. The presence of a notable number of genes in “O: Post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones” and “L: Replication, recombination, and repair” categories highlights the strain’s capacity for protein quality control and genomic maintenance, which may contribute to its survival under oxidative or nutrient-variable floral environments [31].

Collectively, the COG-based functional distribution underscores that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 possesses a metabolically flexible and environmentally resilient genomic framework, supporting its adaptation to the floral niche and its potential as a bioactive resource for postbiotic or cosmeceutical applications.

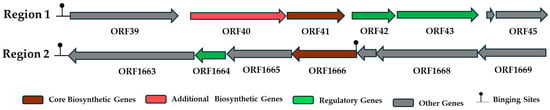

3.4. Genome Mining and Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Analysis

Comprehensive genome mining of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 using antiSMASH v8.0.4 revealed the presence of putative secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters primarily associated with terpenoid biosynthesis, while no bacteriocin-, polyketide-, or nonribosomal peptide synthetase-related loci were detected (Figure 4). The identified clusters indicate that this strain possesses a metabolic system specialized for structural and oxidative resilience rather than antimicrobial compound production. In particular, Region 1 encodes a compact yet functionally rich terpenoid biosynthetic operon containing genes for phytoene/squalene synthase, a phytoene desaturase (CrtI-like enzyme), two metallophosphoesterases, and a two-component response regulator transcription factor. This genomic configuration suggests a metal-assisted, redox-regulated isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in which oxidative desaturation by the CrtI-like enzyme is coupled with metal-dependent phosphate recycling and redox modulation mediated by the dual metallophosphoesterases. The co-occurrence of a response regulator indicates that this cluster is transcriptionally responsive to environmental stimuli such as oxidative or metal-ion stress, enabling E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 to maintain membrane stability and mitigate reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. Such a redox-responsive terpenoid system likely provides an ecological advantage in the UV-intense floral microhabitat of Zinnia elegans from which the strain was isolated [11,32].

Figure 4.

Predicted biosynthetic gene clusters in E. alishanensis JNUCC 77. antiSMASH analysis revealed two regions: Region 1, a terpenoid operon with genes for phytoene/squalene synthase, desaturase, and regulatory elements, indicating a redox-regulated isoprenoid pathway; and Region 2, containing RecN, ArgR, TlyA, and a polyprenyl synthetase-like enzyme, associated with stress adaptation and redox homeostasis.

In addition, Region 2 was identified as a unique gene set containing homologs of DNA repair protein RecN, an arginine repressor (ArgR), a TlyA family RNA methyltransferase, and a polyprenyl synthetase-like enzyme. Although this region does not represent a canonical secondary metabolite cluster, its gene composition suggests a stress-adaptive regulatory module that couples genome maintenance, transcriptional control, and isoprenoid-linked redox adaptation. RecN is a key component of the bacterial DNA repair machinery, facilitating chromosomal stability under oxidative conditions, whereas ArgR functions as a transcriptional regulator linking nitrogen metabolism to cellular redox balance. The presence of the TlyA methyltransferase implies RNA-level protection through rRNA methylation, enhancing translational fidelity during stress, while the adjacent polyprenyl synthetase-like gene contributes to the biosynthesis of membrane-associated isoprenoid lipids involved in cellular protection [33]. Together, these features indicate that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 has evolved a redox–genome stability interface, integrating terpenoid metabolism, phosphate and metal ion homeostasis, and DNA/RNA repair mechanisms to survive under UV- and ROS-rich floral environments. The absence of bacteriocin and other peptide biosynthetic systems further implies that this strain relies on oxidative stress tolerance and metabolic adaptability, rather than antagonistic interactions, as its primary ecological survival strategy.

4. Conclusions

The complete genome of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77, isolated from the flowers of Zinnia elegans in Jeju Island, reveals a well-adapted bacterium specialized for survival in oxidative floral environments. Genome-based analyses confirmed its taxonomic identity with E. alishanensis, characterized by a compact, low-GC genome lacking plasmid elements but enriched with genes for transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and terpenoid metabolism.

The integration of TYGS-based phylogenomic positioning, COG functional classification, and antiSMASH-predicted biosynthetic clusters highlights a unique metabolic organization that emphasizes stress adaptation and membrane stabilization rather than antimicrobial competitiveness. These genomic signatures support the hypothesis that E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 maintains ecological fitness through redox balance, metal-ion regulation, and lipid-associated antioxidant systems.

Overall, E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 represents a non-pathogenic, environmentally resilient, and biotechnologically valuable strain, offering potential for use as a microbial source of postbiotic ingredients, antioxidant peptides, and redox-protective metabolites in health-related and cosmeceutical formulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-G.H.; methodology, K.-A.H., M.N.K. and J.-H.K.; investigation, K.-A.H. and J.-H.K.; resources, K.-A.H.; data curation J.-H.K.; formal analysis, C.-G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-G.H.; writing—review and editing, C.-G.H.; supervision, C.-G.H.; project administration, C.-G.H.; funding acquisition, C.-G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS), Korea, under the “Supporting Project for Boosting a Local Innovation Leading Company (R&D), S3454244” supervised by the Korea Technology and Information Promotion Agency for SMEs (TIPA).

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article. The complete genome sequence of E. alishanensis JNUCC 77 has been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1344846, BioSample accession number SAMN52655648, and GenBank accession number JBSJXU000000000. No additional data are available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ramos, S.; Silva, V.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Enterococci, from Harmless Bacteria to a Pathogen. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, B.; Wityk, P.; Gałęcka, M.; Michalik, M. The Many Faces of Enterococcus spp.-Commensal, Probiotic and Opportunistic Pathogen. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Braïek, O.; Smaoui, S. Enterococci: Between Emerging Pathogens and Potential Probiotics. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5938210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferchichi, M.; Sebei, K.; Boukerb, A.M.; Karray-Bouraoui, N.; Chevalier, S.; Feuilloley, M.G.J.; Connil, N.; Zommiti, M. Enterococcus spp.: Is It a Bad Choice for a Good Use—A Conundrum to Solve? Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnar, A.G.; Kim, G.B. Probiotic potential and safety assessment of bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus faecalis CAUM157. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1563444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H.; Otoguro, M.; Yanagida, F.; Wu, H.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Chen, Y.S. Enterococcus alishanensis sp. nov., a novel lactic acid bacterium isolated from fresh coffee beans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Prajapati, N.; Prajapati, A.; Singh, S.; Joshi, M.; Prajapati, D.; Patani, A.; Sahoo, D.K.; Patel, A. Postbiotic Emissaries: A Comprehensive Review on the Bioprospecting and Production of Bioactive Compounds by Enterococcus Species. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 6769–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyashri, G.; Krishna, G.; Muralidhara Prapulla, S.G. Probiotic attributes, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuromodulatory effects of Enterococcus faecium CFR 3003: In vitro and in vivo evidence. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pristavu, M.C.; Diguță, F.C.; Aldea, A.C.; Badea, F.; Dragoi Cudalbeanu, M.; Ortan, A.; Matei, F. Functional Profiling of Enterococcus and Pediococcus Strains: An In Vitro Study on Probiotic and Postbiotic Properties. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.I.; Shin, H.D.; Lee, Y.; Baek, S.; Moon, E.; Park, Y.B.; Cho, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.J.; Manoharan, R.K. Probiotic and Postbiotic Potentials of Enterococcus faecalis EF-2001: A Safety Assessment. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, R.A.; Rebolleda-Gómez, M.; Butela, K.; Cabo, L.F.; Cullen, N.; Kaufmann, N.; O’Neill, S.; Ashman, T.L. Spatially explicit depiction of a floral epiphytic bacterial community reveals role for environmental filtering within petals. Microbiologyopen 2021, 10, e1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, E.C.; Schaeffer, R.N. The Floral Microbiome and Its Management in Agroecosystems: A Perspective. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9819–9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koza, N.A.; Adedayo, A.A.; Babalola, O.O.; Kappo, A.P. Microorganisms in Plant Growth and Development: Roles in Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Secondary Metabolites Secretion. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.J.; Cha, I.T.; Park, S.J. Revealing the Prokaryotic Microbial Community Structures and their Ecological Potentials in Manjanggul Cave, a Lava Tube on Jeju Island. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.G. Hypochoeris radicata attenuates LPS-induced inflammation by suppressing p38, ERK, and JNK phosphorylation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. EXCLI J. 2014, 13, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Chalita, M.; Ha, S.M.; Na, S.I.; Yoon, S.H.; Chun, J. ContEst16S: An algorithm that identifies contaminated prokaryotic genomes using 16S RNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Desper, R.; Gascuel, O. FastME 2.0: A Comprehensive, Accurate, and Fast Distance-Based Phylogeny Inference Program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2798–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Lim, J.; Kwon, S.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsakhawy, O.K.; Abouelkhair, M.A. Genome Mining Reveals a Sactipeptide Biosynthetic Cluster in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Szenei, J.; Vader, L. Using antiSMASH. Methods Enzymol. 2025, 717, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdouc, M.M.; Blin, K.; Louwen, N.L.L.; Navarro, J.; Loureiro, C.; Bader, C.D.; Bailey, C.B.; Barra, L.; Booth, T.J.; Bozhüyük, K.A.J.; et al. MIBiG 4.0: Advancing biosynthetic gene cluster curation through global collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D678–D690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Xi, X.; Menghe, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z. Comparative genomic analysis of the genus Enterococcus. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 196, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Z.; Shahzad, K.; Ali, H.; Casini, R.; Naveed, K.; Hafeez, A.; El-Ansary, D.O.; Elansary, H.O.; Fiaz, S.; Abaid-Ullah, M.; et al. 16S rRNA gene flow in Enterococcus spp. and SNP analysis: A reliable approach for specie level identification. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2022, 103, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Ye, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, J. Genome sequence-based species classification of Enterobacter cloacae complex: A study among clinical isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0431223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Kwok, L.Y.; Hou, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z. Comparative genomic analysis revealed great plasticity and environmental adaptation of the genomes of Enterococcus faecium. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic and functional paths of lactic acid bacteria in plant foods: Get out of the labyrinth. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, G.A. Genetics of eubacterial carotenoid biosynthesis: A colorful tale. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1997, 51, 629–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).