Abstract

Staphylococcus spp. are potential pathogens classified into more than 50 species, frequently presenting antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to several drugs. The present study aimed to identify the Staphylococcus species and their AMR in staphylococci isolated from healthy companion animals (pets) in southern Brazil. A total of 78 presumptive Staphylococcus sp. isolates (from 48 dogs and 30 cats) were obtained in a period of five years (2018–2022). All isolates were analyzed by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight (MALDI-ToF) and tested with a panel of antimicrobials frequently used in pet treatment in Brazil. The results demonstrated that 68 isolates were identified as Staphylococcus spp., including 26 (38.2%) classified as coagulase-positive staphylococci (CoPS) and 42 (61.8%) as coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). CoPS included S. pseudintermedius (n = 20; 29.4%), S. aureus (n = 3; 4.4%), and S. schleiferi (n = 2; 2.9%), while CoNS were S. equorum (n = 12; 17.6%), S. felis (n = 7; 10.3%), S. sciuri (n = 8; 11.8%), S. simulans (n = 4; 5.9%), S. epidermidis (n = 1; 1.5%), S. haemolyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), S. saprophyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), and S. xylosus (n = 1; 1.5%). The remaining eight isolates were identified as Staphylococcus spp. AMR analyses demonstrated that 17 (25%) isolates presented susceptibility to all tested drugs, and 51 (75%) to one or more antimicrobials. Twenty-four (35.6%) isolates were multidrug resistant (MDR), and 13 (19.1%) were methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS). S. pseudintermedius was the CoPS most frequently with AMR, including nine (45%) MDR and four (20%) MRS, while S. equorum was the predominant CoNS with AMR, highlighting nine (75%) MDR and four (33.3%) MRS. The Staphylococcus species diversity identified here highlights the importance of studying the microorganisms circulating in healthy companion animals and their characteristics concerning pathogenicity and AMR.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus spp. form a genus belonging to the family Staphylococcaceae and are characterized as Gram-positive, non-motile, cocci-shaped bacteria usually arranged in clusters as “grape-like” when visualized under a microscope. One of the main biochemical characteristics of this bacterial genus is the synthesis of the enzyme catalase, which degrades hydrogen peroxide [1]. Taxonomically, it is classified into 89 recognized species and 30 subspecies, presenting different levels of pathogenicity and living in the high-diversity environments of animal hosts [2]. The different Staphylococcus species are usually divided into two main groups according to the ability to clot blood: coagulase-positive staphylococci (CoPS) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). CoPS are considered more virulent pathogens as blood clotting protects the bacteria from the host’s immune defenses [3]. They are also frequently associated with more serious infections in mammals [4]. CoPS species include S. aureus and the five members of the S. intermedius group (SIG): S. intermedius, S. pseudintermedius, S. delphini, S. cornubiensis, and S. ursi [5,6,7,8,9]. On the other hand, CoNS species comprise a large and expanding group of generally non-pathogenic bacteria, with more than 50 species and at least 20 subspecies [9].

Overall, CoPS and CoNS were already detected in the normal skin and mucous microbiotas of mammals [10]. Notably, pathogenic and commensal staphylococci can coexist in different animal tissues with other microorganisms, with some species more adapted to specific hosts. For example, S. pseudintermedius, S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and S. sciuri are frequently detected in dogs [11,12,13], while S. felis, S. pseudintermedius, and S. schleiferi are detected in cats [14,15]. In addition, CoPS have been observed in skin lesions, abscesses, and other internal body parts (nose, mouth, perineum–rectum, groin) of both dogs and cats [12].

S. aureus has generally been considered the most concerning pathogenic species in domestic animals because it carries important virulence factors [16]. S. aureus has also been associated with human community-acquired and nosocomial infections, causing serious and even fatal infections [17,18]. However, other potentially pathogenic Staphylococcus spp. (highlighting S. pseudintermedius and S. felis) have already been detected in pets, associated with pyoderma, otitis media, postoperative wounds, and infections in the urinary tract [19,20,21,22].

The increasing use of drugs in veterinary medicine of companion animals has contributed to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Staphylococcus spp. [23]. Many staphylococci species have acquired AMR to a large extent of antimicrobials over time due to the selective pressure from the excessive and inappropriate use of antimicrobials in both veterinary and human medicine. Consequently, antibacterial treatment options have become more limited, making infections difficult to treat, especially those caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococcus (MRS) [24]. MRS isolates are also usually resistant to several other classes of antimicrobials and present a multidrug resistance (MDR) profile [25,26]. The identification of MRS and MDR in Staphylococcus isolated from animals is necessary for continued monitoring of the spread and control of AMR strains [27].

In Brazil, few studies have investigated Staphylococcus spp. from the microbiota of companion animals (highlighting dogs and cats) [22,28,29,30]. The present study aimed to determine the diversity of the Staphylococcus species and to evaluate the AMR in a sample of healthy dogs and cats from southern Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Population

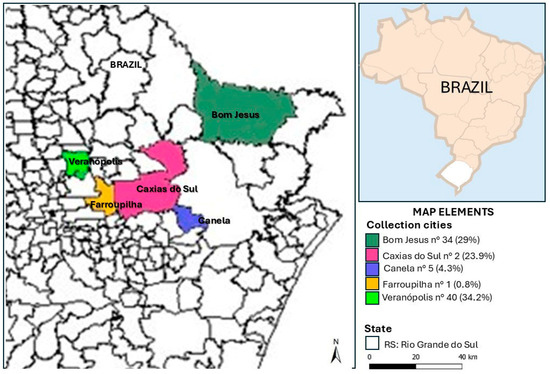

This study was performed with a convenience sampling of 117 different healthy animals (80 dogs and 37 cats) treated in routine check-ups or neutering procedures in five different cities (Caxias do Sul, Canela, Farroupilha, Bom Jesus, and Veranópolis) of southern Brazil in the period from November 2018 to August 2022 (Figure 1). The samples were collected mainly from males (70 dogs and 34 cats), but there were also samples from females (10 dogs and 3 cats). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA) of the University of Caxias do Saul (UCS) under the number 21/2018. Samples for bacteria isolation were collected using swabs previously moistened with sterile saline solution and passed over the mouth, skin, eyes, ears, rectum, and nose (intranasal). The swabs were maintained in Stuart transport medium (Absorve®, Jiangsu Rongye, Yangzhou, China) for no more than 24 h before cultivation.

Figure 1.

Locations and the respective number of collections carried out between 2018 and 2022.

2.2. Bacteriological Culture and Staphylococci Isolation

The culture was performed by streaking the swabs on Blood Agar Base plates (Acumedia®, Lansing, MI, EUA) and incubating at 37 °C for 24 h as the routine procedure of the laboratory. Suspected Staphylococcus spp. isolates were evaluated for macroscopic (colony morphology on blood agar) and microscopic (Gram staining) characteristics. Briefly, the first isolated colonies were seeded to obtain pure cultures. Flat colonies with a cream to slightly grayish color and smooth, regular edges were selected for further evaluation. In the microscopic analysis, only isolates that presented spherical or ovoid Gram-positive cells, with small variation in the diameter of the cocci in some isolates, in a typical staphylococcal arrangement (bunch of grapes), diplococci (cocci grouped in pairs), tetrads (groups of four cocci), and micrococci (isolated cocci) were selected to be used.

All these isolates were tested for catalase activity with 35% of Hydrogen Peroxide (Neon®, Suzano, SP, Brazil) and coagulation reaction with rabbit plasma (Newprow®, Pinhais, PR, Brazil). The catalase test was performed on sterilized microscope slides by adding half of a colony of the isolate to a drop of hydrogen peroxide and classifying catalase-positive bacteria as those exhibiting bubbling. The coagulase test was performed with a bacterial cell suspension obtained after inoculating half of a colony in 0.5 mL of Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, Himedia®, Mumbai, India) and incubating at 37 °C for eight hours. Then, 0.2 mL of each cell suspension was added to a sterilized test tube with 0.5 mL of rabbit plasma, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The tubes were evaluated after 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h of incubation, gently tilted to the side, classifying them as coagulase-positive (clotting) or coagulase-negative (not clotting). All isolates were classified as catalase-positive and catalase-negative, as well as CoPS and CoNS. The isolates were also maintained on BHI agar supplemented with 30% glycerol at −20 °C for further analysis.

2.3. Bacterial Species Identification by MALDI-ToF

The bacterial isolates presumptively identified as Staphylococcus spp. were further identified by MALDI-ToF (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption and Ionization Time-of-Flight). The microbiological preparation included the cultivation of bacteria on blood agar culture medium up to 24h (fresh culture), followed by protein extraction. A typical colony was transferred to a tube with 0.3 mL of water and homogenized until the solution became cloudy, followed by the addition of 900 µL of absolute ethanol. These tubes were centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rotations per minute (rpm); the supernatant was removed, and 50 µL of 70% formic acid was added and mixed with the pellet. After 30 min, 50 µL of acetonitrile was added, mixed, and centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant with the protein extract was pipetted (1 µL) onto a spot of a 96-well polished steel plate (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). Finally, 1 μL of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid matrix solution in 50% acetonitrile–2.5% trifluoroacetic acid was overlaid in each well and air-dried at room temperature (25 °C). The spectrum profiles of isolates were obtained using a mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany) with default identification standard settings. Bacteria were identified by analyzing their unique protein profile spectra according to previously described methods [31]. Standard Bruker interpretative criteria were applied, and scores ≥ 2.0 were considered to identify all strains [32] (Table S1).

2.4. AMR Testing

All isolates were tested against a panel of 16 antimicrobials frequently used in human/veterinary medicine using the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method following CLSI guidelines (M100 and VET01 2020) to evaluate breakpoints. The following antimicrobials were included in the analysis: penicillin 10 µg (PEN), oxacillin 1 µg (OXA), cefoxitin 30 µg (CFX), azithromycin 15 µg (AZM), erythromycin 15 µg (ERY), rifampin 5 µg (RIF), gentamicin 10 µg (GEN), chloramphenicol 30 µg (CHL), ciprofloxacin 5 µg (CIP), orbifloxacin 5 µg (ORB), doxycycline 30 µg (DOX), tetracycline 30 µg (TET), sulfazotrim 25 µg (SUT), clindamycin 2 µg (DA), nitrofurantoin 300 µg (NFT), and linezolid 30 µg (LZD). The results were recorded as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to the diameter of the inhibition zone. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as non-susceptibility to at least three agents from three or more different antimicrobial categories [33]. Classification for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (MRS) and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus (MSS) was defined by antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for cefoxitin and oxacillin, according to previously published criteria for specific Staphylococcus species [34].

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Staphylococci Species

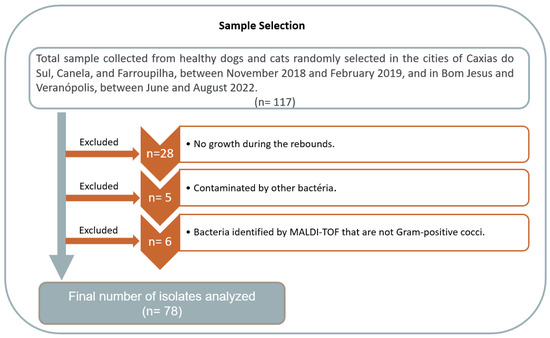

Of the 117 isolates detected as Staphylococcus spp. by classical bacteriological analysis, 39 were missed in the recovery of the cultures and the analytical procedures (Figure 2). Therefore, the final number of presumptively Staphylococcus spp. isolates analyzed by all procedures were 78, including 48 (61.5%) from dogs and 30 (38.5%) from cats. The biochemical analyses demonstrated that 71 (91%) isolates were catalase-positive and 7 (9%) were catalase-negative, while 33 (42.3%) isolates were coagulase-positive and 45 (57.7%) were coagulase-negative.

Figure 2.

Description of the samples selected for this study.

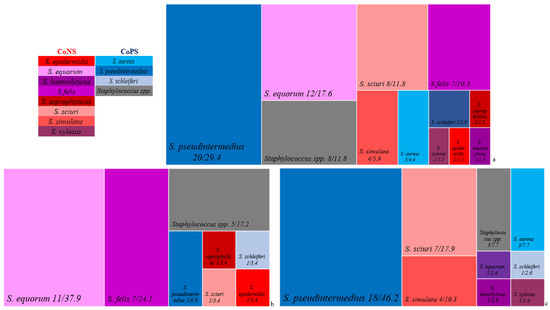

The results obtained by MALDI-ToF showed that 68 isolates (87.2%) were Staphylococcus spp., including 11 different species: S. pseudintermedius (n = 20; 29.4%), S. equorum (n = 12; 17.6%), S. sciuri (n = 8; 11.8%), S. felis (n = 7; 10.3%), S. simulans (n = 4; 5.9%), S. aureus (n = 3; 4.4%), S. schleiferi (n = 2; 2.9%), S. epidermidis (n = 1; 1.5%), S. haemolyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), S. saprophyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), and S. xylosus (n = 1; 1.5%). Furthermore, eight (11.8%) isolates could only be detected as Staphylococcus spp., without an assertive identification of the species (Table 1 and Figure 3a). In the remaining ten isolates, four other genera/species were identified in six isolates: Aerococcus viridans (n = 2; 2.6%), Enterococcus faecalis (n = 2; 2.6%), Macrococcus spp. (n = 1; 1.3%), and Rothia nasimurium (n = 1; 1.3%). It was not possible to identify the genus and species in four (5.1%) isolates.

Table 1.

Staphylococcus species identified by MALDI-ToF.

Figure 3.

Treemapping presenting the 11 species identified by MALDI-ToF in all Staphylococcus isolates (a), as well as in these same genus isolates from cats (b) and dogs (c). The red palette represents the species identified in the CoNS group, and the blue palette represents the species found in the CoPS group. Gray represents Staphylococcus spp. isolates.

Seven different Staphylococcus species were identified in the cat samples: S. equorum (n = 11; 37.9%), S. felis (n = 7; 24.1%), S. pseudintermedius (n = 2; 6.9%), S. epidermidis (n = 1; 3.4%), S. saprophyticus (n = 1; 3.4%), S. schleiferi (n = 1; 3.4%), and S. sciuri (n = 1; 3.4%) (Figure 3b). Eight different Staphylococcus species were identified in the dog samples: S. pseudintermedius (n = 18; 46.2%), S. sciuri (n = 7; 17.9%), S. simulans (n = 4; 10.3%), S. aureus (n = 3; 7.7%), S. equorum (n = 1; 2.6%), S. haemolyticus (n = 1; 2.6%), S. schleiferi (n = 1; 2.6%), and S. xylosus (n = 1; 2.6%) (Figure 3c).

In addition, the MALDI-ToF results were compared with the previous bacteriological results, highlighting catalase and coagulase reactions. The catalase test results among the Staphylococcus species (n = 68) showed that 64 were positive, including nineteen S. pseudintermedius, twelve S. equorum, eight S. sciuri, five S. felis, four S. simulans, three S. aureus, two S. schleiferi, one S. haemolyticus, one S. saprophyticus, one S. xylosus, and eight Staphylococcus spp. But there were also four catalase-negative isolates, including two S. felis, one S. epidermidis, and one S. pseudintermedius.

The coagulase test results allowed us to classify the 68 Staphylococcus spp. into CoPS and CoNS. The first group comprised the species S. pseudintermedius (n = 20; 29.4%), S. aureus (n = 3; 4.4%), S. schleiferi (n = 2; 2.9%), and Staphylococcus spp. (n = 1; 1.8%). The CoNs group included S. equorum (n = 12; 17.6%), S. sciuri (n = 8; 11.8%), S. felis (n = 7; 10.3%), S. simulans (n = 4; 5.9%), S. haemolyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), S. epidermidis (n = 1; 1.5%), S. saprophyticus (n = 1; 1.5%), S. xylosus (n = 1; 1.5%), and Staphylococcus spp. (n = 7; 10.3%).

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

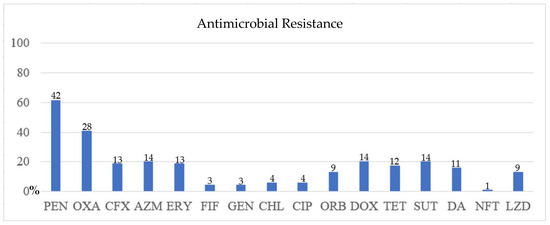

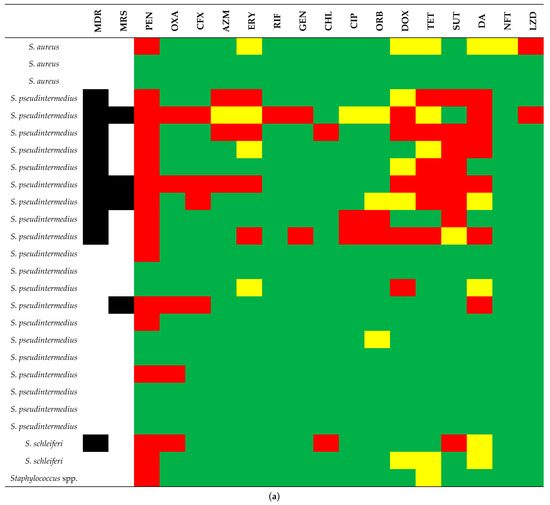

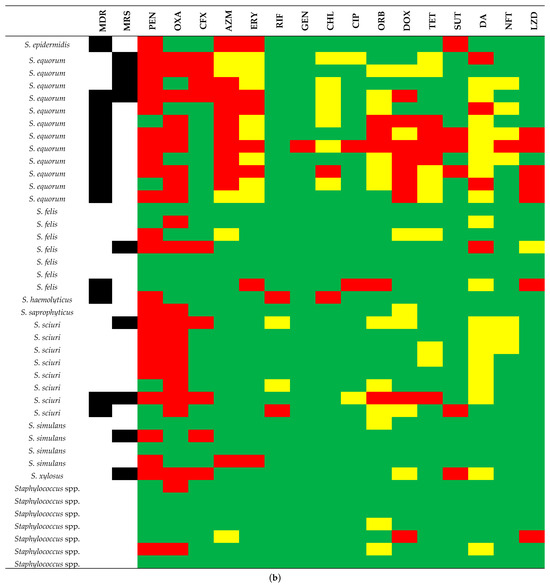

Seventeen (25%) Staphylococcus spp. isolates showed susceptibility to all the tested antimicrobials, while 51 (75%) had resistance to one to twelve antimicrobials (mean = 3 and median = 3). Furthermore, 42 (61.8%) were resistant to PEN, 28 (41.2%) to OXA, and 14 (20.6%) to SUT, AZM, and DOX. Resistance to the other antimicrobials was below 20%. Intermediate resistance to 12 antimicrobials was also observed (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Susceptibility test result of the 68 isolates. The Y-axis represents the percentage of isolates resistant to the antimicrobial on the X-axis. PEN = penicillin; OXA = oxacillin; CFX = cefoxitin; AZM = azithromycin; ERY = erythromycin; RIF = rifampin; GEN = gentamycin; CHL = chloramphenicol; CIP = ciprofloxacin; ORB = orbifloxacin; DOX = doxycycline; TET = tetracycline; SUT = sulfazotrim; DA = clindamycin; NFT = nitrofurantoin; LZD = linezolid; NA = not applicable. The isolate number that shows resistance to the antimicrobial is at the top of the bar.

Figure 5.

Susceptibility test result profile of the 26 CoPS (coagulase-positive staphylococci). (a) and 42 CoNS (coagulase-negative staphylococci), (b) in comparison to Staphylococcus species. Green, yellow, and red squares mean susceptibility, intermediate resistance, and resistance, respectively. Black squares mean MDR (multidrug resistance) and MRS (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus). Antimicrobial abbreviations: PEN = penicillin; OXA= oxacillin; CFX = cefoxitin; AZM = azithromycin; ERY = erythromycin; RIF = rifampin; GEN = gentamycin; CHL = chloramphenicol; CIP = ciprofloxacin; ORB = orbifloxacin; DOX = doxycycline; TET = tetracycline; SUT = sulfazotrim; DA = clindamycin; NFT = nitrofurantoin; LZD = linezolid; NA = not applicable.

Moreover, 24 (35.3%) isolates were classified as MDR, showing resistance from three (n = 14) to eight (n = 1) classes (mean = 2.6 and median = 2), and 13 (19.1%) were MRS. The most frequently observed MDR patterns were beta-lactams + macrolides + tetracyclines, beta-lactams + tetracyclines + sulfonamides, and beta-lactams + lincosamides + macrolides + tetracyclines + sulfonamides.

In the CoPS group (n = 26), there were 8 (30.8%) isolates susceptible to all the tested antimicrobials and 18 (69.2%) resistant to one to nine drugs (mean = 2.6 and median = 1.5). In a comparative analysis between the three CoPS species, SIG S. pseudintermedius was the most frequent (n = 20; 77%), including 6 isolates with susceptibility to all the antimicrobials and 14 with resistance to one to nine drugs (mean = 3.1; median = 2.5). Also, this species had nine MDR isolates and four MRS, while S. schleiferi showed one MDR isolate. S. aureus did not present MDR and MRS profiles (Figure 5a).

In the CoNS group (n = 42), susceptibility testing analysis demonstrated that the isolates showed resistance to between no (n = 9) and 12 (n = 1) antimicrobials (mean = 2.8 and median = 2.5); 25 (59.5%) isolates were resistant to PEN, and 23 (54.8%) isolates were resistant to OXA. Resistance to the other antimicrobials tested was less than 27%. In a comparative analysis between the eight CoNS species, S. equorum was the most frequent at 12 (28.6%), with resistance ranging from 3 (n = 2) to 12 (n = 1) of the 16 antimicrobials tested (mean = 5.4; median = 4.5), and PEN, OXA, and AZM presented a higher frequency of resistance (83.3%, 75%, and 75%, respectively). Followed by S. sciuri at eight (19%), with resistance ranging from one (n = 1) to six (n = 1) antimicrobials (mean = 2.6; median = 2), OXA and PEN presented a higher frequency of resistance (100% and 75%, respectively). Seven S. felis (16.7%) had resistance ranging from no (n = 3) to four (n = 2) antimicrobials (mean = 1.4; median = 1), none showing high frequency. Four S. simulans (9.5%) had resistance ranging from no (n = 2) to three (n = 1) antimicrobials (mean = 1; median = 1), none showing high frequency. Finally, seven Staphylococcus spp. (16.7%) had resistance ranging from no (n = 4) to two (n = 2) antimicrobials (mean = 0.7; median = 0), none showing high frequency (Figure 5b).

S. equorum showed nine (75%) isolates with an MDR profile and four (33.3%) MRS, S. sciuri showed two (25%) isolates with an MDR profile and two (25%) MRS, S. felis showed one (14.3%) isolate with an MDR profile and one (14.3%) MRS, and S. simulans showed one (25%) isolate with an MRS profile and none MDR (Figure 5b).

4. Discussion

The animal skin microbiota comprises a diverse range of microorganisms inhabiting the tissue. This microbial community plays a crucial role in skin health, acting as a protective barrier and influencing an animal’s immune response. The microbiota composition of each animal species and even of individual animals is influenced by several factors, such as diet, habits, climate, and environment, among others [35,36]. In the veterinary medicine of companion animals, previous studies have already been carried out to characterize the microbial populations of skin microbiota, contributing to a better understanding of situations of normality (health) and imbalance, which can result in infections by pathogenic or even opportunistic microorganisms [37].

In the present study, eleven different Staphylococcus spp. were found on the skin of apparently healthy dogs and cats, predominantly isolated from the skin of the evaluated animals. Other Staphylococcus spp. are probably present there, since some bacteria of this genus could not be identified by the MALDI-ToF method at the species level. The number of Staphylococcus spp. or even other similar bacteria present in the microbiota on the skin of these animals is probably even higher, as reported in other studies on healthy and diseased animals worldwide [37,38,39]. In Brazil, previous studies detected eight species in dogs, including S. pseudintermedius, S. delphini, S. schleiferi, S. aureus, S. capitis, S. epidermidis, S. warneri, and S. simulans, identified on the skin and also other tissues (ear, urogenital tract, surgical wounds, etc.) [28,40]. Notably, S. pseudintermedius was the most prevalent staphylococci detected here, with 20 isolates (29.4%), including 18 from dogs. A similar result was observed in a previous study, which isolated Staphylococcus from rectal and axillary samples [41]. Other studies highlighted S. pseudintermedius as a pathogenic bacterium in pets and also detected it in humans [42].

Staphylococcus spp. are frequently considered a concerning bacterial genus on the skin of healthy dogs and cats. However, commensal and pathogenic Staphylococcus species have already been demonstrated to be present on this tissue in healthy animals [43,44,45,46]. In dogs, they are associated with pyoderma, otitis externa and media, cystitis, and other systemic and respiratory infections [20,47]. Notably, three species (S. pseudintermedius, S. aureus, and S. schleiferi) have been more commonly associated with prosthetic infections, wound infections, postsurgical infections, bacteremia, and endocarditis, also in humans [48]. The occurrence of these bacteria has also been a concern in veterinary care settings, as they can cause nosocomial infections. A previous study identified 10 Staphylococcus spp. (S. pseudintermedius, S. haemolyticus, S. epidermidis, S. schleiferi, S. capitis, S. sciuri, S. warneri, S. lutrae, S. xylosus, and S. hominis) in different sampling sites (superficial surgical site, surgical site infection, surgeon, and environment) in an operating room. S. pseudintermedius was more frequently found in surgical sites, whereas CoNS were predominant in samples from surgeons and the environment [32].

In an attempt to separate pathogenic and commensal Staphylococcus spp., the coagulase test has been routinely performed in the laboratory. CoPS have been considered the most concerning bacteria for animal health. However, there are some isolates with confusing coagulation profiles, such as S. schleiferi [20]. In this study, the two isolates from this species tested positive for the coagulase test, which can be interpreted as S. schleiferi subsp. coagulans. The other subspecies, S. schleiferi subsp. schleiferi, can show a positive result on the slide (agglutination factor) but tests negative in the tube coagulase test [49]. Both subspecies are important pathogens for dogs [50].

CoNS have also been long regarded as harmless colonizers; however, their involvement in infections and their potential to cause serious conditions, such as endocarditis and sepsis, were already recognized [51]. Among the eight CoNS species identified in this study, S. equorum and S. felis were the most prevalent, both mostly isolated from cats. These species were also reported in other studies that detected an even higher number of species, such as S. warneri, S. succinus, S. capitis, S. hominis, S. cohnii, S. vitulinus, S. arlettae, S. pettenkoferi, S. fleurettii, S. nepalensis, S. lentus, S. lutetiensis, and S. muscae [10,52]. In Brazil, a previous study on dogs admitted to hospitals demonstrated six CoNS species: S. haemolyticus, S. felis, S. epidermidis, S. simulans, S. saprophyticus, S. equorum, S. hominis, and S. devriesei [41]. These studies highlight the considerable diversity of Staphylococcus spp. with different metabolic characteristics (such as coagulase and catalase) present in the microbiota of companion animals.

In studies evaluating the microbiota of healthy animals, S. felis was predominantly isolated from cats, along with other species, such as S. epidermidis, S. simulans, and S. haemolyticus [10,38]. Additionally, S. haemolyticus, S. xylosus, S. capitis, S. gallinarum, S. lentus, and S. equorum were detected in feline samples [10]. The same occurs with S. equorum, isolated predominantly from felines, but also in canines [10,41]. S. sciuri, S. simulans, and S. haemolyticus have been isolated from dogs and are part of the cutaneous, nasal, and oral microbiota of healthy dogs [53]. They are also known to be causative agents of infections [54]. S. chromogenes, S. intermedius, and S. xylosus have been isolated only from canines, and S. saprophyticus has been isolated only from felines. Similar findings were reported in a previous study [11].

It is noteworthy that other non-Staphylococcus Gram-positive bacteria (n = 10) were identified by MALDI-ToF here. Six isolates could be properly classified as bacteria already detected in the microbiota of companion animals: Aerococcus viridans has been isolated from the oral cavity of stray dogs and cats; Enterococcus spp. is commonly isolated from dog skin [55,56,57]; Macrococcus caseolyticus and other Macrococcus species are also found in the skin microbiota of canines and felines [58]; and Rothia nasimurium is also a commensal microorganism in dogs. The other four isolates did not present valid identification results. This misidentification of other bacteria as Staphylococcus spp. emphasizes the need for improved bacterial species identification techniques. Traditional methods based on macroscopic colony evaluation, morphology, staining, and basic biochemical tests have been widely used in routine laboratories and are likely to report erroneous laboratory results for Gram-positive bacteria. In addition, a high diversity of enzymatic activities among Staphylococcus (highlighting catalase and coagulase profiles) can further complicate the correct identification of the bacterial genus/species [59,60]. Most veterinary laboratories still rely on classical methods for the identification and classification of bacteria, such as morphological analysis, staining techniques, and biochemical testing. The growing use of modern techniques, such as MALDI-ToF, will certainly improve bacterial identification in veterinary medicine routine [61,62].

Regarding AMR, the patterns varied considerably within both CoPS and CoNS, with 65.4% of CoPS isolates showing resistance to PEN, while resistance to other antimicrobials remained below 31%. S. pseudintermedius was the most concerning CoPS species, with 45% (9/20) of the isolates with MDR, while S. aureus did not present MDR. Reports of S. pseudintermedius isolated from dogs and cats also demonstrated high MDR rates (63.3 to 89.2%) [28,45]. Although S. aureus is often cited as an important and resistant pathogen in human infections [63], dogs and cats are not typically colonized by this species. Instead, they may form transient associations with strains acquired from their owners, which can lead to opportunistic infections [39,64].

CoPS isolates are historically associated with pathogenic potential and clinical relevance, making their identification and characterization essential [65]. Among them, S. pseudintermedius and S. schleiferi can exhibit methicillin resistance through the production of another penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a), similarly to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Interestingly, only four (15.4%) CoPS isolates in this study were MRS, a notably lower rate compared to previous reports [20,66]. These differences may reflect variations in sampling sources, geographic distribution, and antimicrobial usage practices across animal populations. In addition, CoNS are also resistant to different antimicrobials (highlighting methicillin), acting as reservoirs of AMR [50]. In this study, S. equorum strains exhibited the most concerning profile, with 75% classified as MDR and 33.3% as MRS. Similar patterns have been reported elsewhere [56,67]. These findings highlight the increasing concern over CoNS as opportunistic pathogens due to their growing resistance and potential for horizontal gene transfer [52]. However, it is important to highlight that intrinsic variations may have occurred in the disk diffusion test for the isolates tested here, due to a resistance that is inherent to the microorganism or to a specific biological or genetic characteristic that may be difficult to detect using the traditional disk diffusion method.

Finally, this study brings scientific insights into the diversity of staphylococci in domestic animals, reinforcing the existence of several species specific to the two domestic animal species studied (dogs and cats). It also presents important antimicrobial resistance data for managing infections in these animals and even their owners. However, it is necessary to highlight some important limitations. First, a limited number of isolates were sampled from clinically healthy animals, which may not reflect the full spectrum of Staphylococcus spp. diversity and resistance profiles in diseased dogs and cats. Furthermore, it was a pilot study using convenience sampling, without statistical calculation of the number of samples needed for a more definitive estimate of the frequency of bacterial species or even more definitive information about AMR in these bacteria. More detailed analyses of AMR, using minimum inhibitory concentrations and more up-to-date resistance data, such as those recently published for fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol, should be the focus of future, more robust studies. Also, in-depth genetic analyses, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS), were not performed, which could provide insights into the genetic relatedness, virulence factors, presence of genes for AMR, and sequence types of the isolates. Future studies should include broader sampling and genetic analyses to better characterize the strains and understand their epidemiological and clinical significance.

5. Conclusions

Eleven different Staphylococcus species were detected by MALDI-ToF in the microbiota of healthy dogs and cats from southern Brazil. Assertive identification of Staphylococcus spp. in animals is necessary to understand the epidemiology of this potential pathogen and to detect more concerning species, such as S. pseudintermedius and S. aureus. Furthermore, this study demonstrated isolates with high AMR, including resistance to methicillin and an MDR profile. AMR assessment studies are needed to help in the control and treatment of staphylococcal infections and prevent the spread of these bacteria in veterinary clinical settings and in the community within a One Health context.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microbiolres16110231/s1, Table S1. MALDI-TOF results of the 78 isolates showing the top 10 matches.

Author Contributions

L.d.S., conceptualization and design of the study; sample collection; methodology; formal analysis; review and approval of the final manuscript; T.S.L., methodology; data analysis; and review and approval of the final manuscript; G.B., sample collection; formal analysis; review and approval of the final manuscript; A.d.B.M., formal analysis; data collection; review and approval of the final manuscript; L.d.M.R., validation; funding acquisition; review and approval of the final manuscript; D.K., validation; review and approval of the final manuscript; A.F.S., supervision; review and approval of the final manuscript; V.R.L., conceptualization and design of the study; sample collection; methodology; formal analysis; review and approval of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS). L.d.S., T.S.L, G.B. and A.d.B.M. were financed in part by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES—Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil—Finance Code 001. D.K. and V.R.L. were financially supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development from Brazil (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico [CNPq]; process numbers 350153/2025-6 and 303647/2023-0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA) of the University of Caxias do Saul (UCS) on 5 December 2018, under the number 21/2018 and renewed for data collection until 2022.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Diéssy Kipper and Vagner Ricardo Lunge are affiliated with Simbios Biotecnologia. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wolska-Gębarzewska, M.; Międzobrodzki, J.; Kosecka-Strojek, M. Current types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) in clinically relevant coagulase-negative staphylococcal (CoNS) species. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 50, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, A.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loof, T.G.; Goldmann, O.; Naudin, C.; Mörgelin, M.; Neumann, Y.; Pils, M.C.; Foster, S.J.; Medina, E.; Herwald, H. Staphylococcus aureus-induced clotting of plasma is an immune evasion mechanism for persistence within the fibrin network. Microbiology 2015, 161, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platenik, M.O.; Archer, L.; Kher, L.; Santoro, D. Prevalence of mecA, mecC and Panton-Valentine-Leukocidin Genes in Clinical Isolates of Coagulase Positive Staphylococci from Dermatological Canine Patients. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Kamata, S.; Hiramatsu, K. Reclassification of phenotypically identified staphylococcus intermedius strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.K.; Lee, J.; Bendall, R.; Zhang, L.; Sunde, M.; Schau Slettemeås, J.; Gaze, W.; Page, A.J.; Vos, M. Staphylococcus cornubiensis sp. nov., a member of the Staphylococcus intermedius Group (SIG). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 3404–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreten, V.; Kania, S.A.; Bemis, D. Staphylococcus ursi sp. nov., a new member of the ‘Staphylococcus intermedius group’ isolated from healthy black bears. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 4637–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.C.; Burnham, C.D.; Westblade, L.F. From canines to humans: Clinical importance of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.; Both, A.; Weißelberg, S.; Heilmann, C.; Rohde, H. Emergence of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.C.; Worthing, K.A.; Ward, M.P.; Norris, J.M. Commensal Staphylococci Including Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Dogs and Cats in Remote New South Wales, Australia. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 79, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; García, P.; Miles, J.; Isla, D.; Yáñez, C.; Santibáñez, R.; Núñez, A.; Flores-Yáñez, C.; Del Río, C.; Cuadra, F. Isolation and Identification of Staphylococcus Species Obtained from Healthy Companion Animals and Humans. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczak, M.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Gamian, A.; Rypuła, K.; Bierowiec, K. Colonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus species in healthy and sick pets: Prevalence and risk factors. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, F.P.; De Martino, L. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius: Epidemiological changes, antibiotic resistance, and alternative therapeutic strategies. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 3505–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.C.; Choi, J.H.; Boby, N.; Kim, S.J.; Song, H.J.; Park, H.S.; Gil, M.C.; Yoon, S.S.; Lim, S.K. Prevalence of Bacterial Species in Skin, Urine, Diarrheal Stool, and Respiratory Samples in Cats. Pathogens 2022, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sips, G.J.; van Dijk, M.A.M.; van Westreenen, M.; van der Graaf-van Bloois, L.; Duim, B.; Broens, E.M. Evidence of cat-to-human transmission of Staphylococcus felis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 001661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V. Staphylococci, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Humans: What Are Their Relations? Pathogens 2024, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M. Staphylococci in the human microbiome: The role of host and interbacterial interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 53, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellis, K.L.; Dissanayake, O.M.; Harrison, E.M.; Aggarwal, D. Community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreaks in areas of low prevalence. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Simón, C.; Ceballos, S.; Ortega, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C.; Gómez-Sanz, E. S. pseudintermedius and S. aureus lineages with transmission ability circulate as causative agents of infections in pets for years. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunder, D.A.; Cain, C.L.; O’Shea, K.; Cole, S.D.; Rankin, S.C. Genotypic relatedness and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus schleiferi in clinical samples from dogs in different geographic regions of the United States. Vet. Dermatol. 2015, 26, 406-e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, F.P.; Meroni, G.; Fiorito, F.; De Martino, L.; Martino, P.A. Occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of canine Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains isolated from two different Italian university veterinary hospitals. Vet. Ital. 2020, 56, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, G.M.; Saggin, B.F.; de Carli, S.; da Silva, M.E.R.J.; da Costa, M.M.; Brenig, B.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; Cardoso, M.R.I.; Siqueira, F.M. Virulent potential of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs. Acta Trop. 2023, 242, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneschi, A.; Bardhi, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A. The Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Veterinary Medicine, a Complex Phenomenon: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, A.; Lloyd, D.H. What has changed in canine pyoderma? A narrative review. Vet. J. 2018, 235, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; de Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, S.P.; de Almeida, J.B.; Andrade, Y.M.F.S.; Silva, L.S.C.D.; Chamon, R.C.; Santos, K.R.N.D.; Marques, L.M. Molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospital and community environments in northeastern Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 23, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.A.; Helbig, K.J. The Complex Diseases of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Canines: Where to Next? Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, F.M.; Santana, J.A.; Silva, B.A.; Xavier, R.G.C.; Bonisson, C.T.; Câmara, J.L.S.; Rennó, M.C.; Cunha, J.L.R.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Lobato, F.C.F.; et al. Occurrence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. in diseased dogs in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.M.; de Moraes Assumpção, Y.; Paletta, A.C.C.; Aguiar, L.; Guimarães, L.; da Silva, I.T.; Côrtes, M.F.; Botelho, A.M.N.; Jaeger, L.H.; Ferreira, R.F.; et al. Investigation of antimicrobial susceptibility and genetic diversity among Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs in Rio de Janeiro. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, T.G.V.; Santana, J.A.; Claudino, M.M.S.; Pereira, S.T.; Xavier, R.G.C.; do Amarante, V.S.; de Castro, Y.G.; Dorneles, E.M.S.; Aburjaile, F.F.; de Carvalho, V.A.; et al. Occurrence, genetic diversity, and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. in hospitalized and non-hospitalized cats in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Chon, J.W.; Jeong, H.W.; Song, K.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Bae, D.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.H. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Enterococcus isolates using MALDI-TOF MS and VITEK 2. AMB Express 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possa de Menezes, M.; Vedovelli Cardozo, M.; Pereira, N.; Bugov, M.; Verbisck, N.V.; Castro, V.; Figueiredo de Castro Nassar, A.; Castro Moraes, P. Genotypic profile of Staphylococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., and E. coli colonizing dogs, surgeons, and environment during the intraoperative period: A cross-sectional study in a veterinary teaching hospital in Brazil. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 244–253, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosseau, C.; Romano-Bertrand, S.; Duplan, H.; Lucas, O.; Ingrassia, I.; Pigasse, C.; Roques, C.; Jumas-Bilak, E. Proteobacteria from the human skin microbiota: Species-level diversity and hypotheses. One Health 2016, 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, K.C.; Giuliano, E.A.; Busi, S.B.; Reinero, C.R.; Ericsson, A.C. Evaluation of Healthy Canine Conjunctival, Periocular Haired Skin, and Nasal Microbiota Compared to Conjunctival Culture. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierowiec, K.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Rypuła, K.; Gamian, A. Prevalence of Staphylococcus Species Colonization in Healthy and Sick Cats. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 4360525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, M.F.; Zakaria, Z.; Cheng, C.H.; Ahmad, N.I. Prevalence and multidrug-resistant profile of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs, cats, and pet owners in Malaysia. Vet. World 2023, 16, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Domínguez, M.S.; Carvajal, H.D.; Calle-Echeverri, D.A.; Chinchilla-Cárdenas, D. Molecular Detection and Characterization of the mecA and nuc Genes From Staphylococcus Species (S. aureus, S. pseudintermedius, and S. schleiferi) Isolated From Dogs Suffering Superficial Pyoderma and Their Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, J.A.; Paraguassu, A.O.; Santana, R.S.T.; Xavier, R.G.C.; Freitas, P.M.C.; Aburjaile, F.F.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; Brenig, B.; Bojesen, A.M.; Silva, R.O.S. Risk Factors, Genetic Diversity, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus spp. Isolates in Dogs Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit of a Veterinary Hospital. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L.; Teixeira, I.M.; da Silva, I.T.; Antunes, M.; Pesset, C.; Fonseca, C.; Santos, A.L.; Côrtes, M.F.; Penna, B. Epidemiologic case investigation on the zoonotic transmission of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius among dogs and their owners. J. Infect. Public. Health 2023, 1, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsman, S.; Meler, E.; Mikkelsen, D.; Mallyon, J.; Yao, H.; Magalhães, R.J.S.; Gibson, J.S. Nasal microbiota profiles in shelter dogs with dermatological conditions carrying methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus species. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.N.; Zarazaga, M.; Campaña-Burguet, A.; Eguizábal, P.; Lozano, C.; Torres, C. Nasal Staphylococcus aureus and S. pseudintermedius carriage in healthy dogs and cats: A systematic review of their antibiotic resistance, virulence and genetic lineages of zoonotic relevance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 3368–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, E.A.; Nizami, T.A.; Islam, M.S.; Sarker, S.; Rahman, H.; Hoque, A.; Rahman, M. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence profiling of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from cats, Bangladesh. Vet. Q. 2024, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromfield, J.I.; Zaugg, J.; Straw, R.C.; Cathie, J.; Krueger, A.; Sinha, D.; Chandra, J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Frazer, I.H. Characterization of the skin microbiome in normal and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma affected cats and dogs. mSphere 2024, 9, e0055523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, B.; Varges, R.; Martins, G.M.; Martins, R.R.; Lilenbaum, W. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of staphylococci isolated from canine pyoderma in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewid, A.H.; Kania, A.S. Distinguishing characteristics of Staphylococcus schleiferi and Staphylococcus coagulans of human and canine origin. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainhart, W.; Yarbrough, M.L.; Burnham, C.A. The Brief Case: Staphylococcus intermedius Group-Look What the Dog Dragged In. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00839-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, C.L.; Morris, D.O.; O’Shea, K.; Rankin, S.C. Genotypic relatedness and phenotypic characterization of Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies in clinical samples from dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 72, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štempelová, L.; Kubašová, I.; Bujňáková, D.; Kačírová, J.; Farbáková, J.; Maďar, M.; Karahutová, L.; Strompfová, V. Distribution and Characterization of Staphylococci Isolated from Healthy Canine Skin. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2022, 49, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.M.; Williams, N.J.; Pinchbeck, G.; Corless, C.E.; Shaw, S.; McEwan, N.; Dawson, S.; Nuttall, T. Antimicrobial resistance and characterisation of staphylococci isolated from healthy Labrador retrievers in the United Kingdom. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanović, S.; Dimitrijević, V.; Vuković, D.; Dakić, I.; Savić, B.; Svabic-Vlahović, M. Staphylococcus sciuri as a part of skin, nasal and oral flora in healthy dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 82, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chah, K.F.; Gómez-Sanz, E.; Nwanta, J.A.; Asadu, B.; Agbo, I.C.; Lozano, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C. Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from healthy dogs in Nsukka, Nigeria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fonticoba, R.; Ferrer, L.; Francino, O.; Cuscó, A. The microbiota of the surface, dermis and subcutaneous tissue of dog skin. Anim. Microbiome 2020, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, K.; Nalbone, L.; Giarratana, F. Aerococcus viridans and Public Health: Oral Carriage and Antimicrobial Resistance in Stray Dogs and Cats in Algeria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2023, 29, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Grecellé, C.Z.; Frazzon, A.P.G.; Streck, A.F.; Kipper, D.; Fonseca, A.S.K.; Ikuta, N.; Lunge, V.R. Multidrug-Resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis Isolated from Dogs and Cats in Southern Brazil. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeli Brawand, S.; Cotting, K.; Gómez-Sanz, E.; Collaud, A.; Thomann, A.; Brodard, I.; Rodriguez-Campos, S.; Strauss, C.; Perreten, V. Macrococcus canis sp. nov., a skin bacterium associated with infections in dogs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemis, D.A.; Bryant, M.J.; Reed, P.P.; Brahmbhatt, R.A.; Kania, S.A. Synergistic hemolysis between β-lysin-producing Staphylococcus species and Rothia nasimurium in primary cultures of clinical specimens obtained from dogs. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2014, 26, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi-Bafghi, M. Characterization of the Rothia spp. and their role in human clinical infections. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 93, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croxatto, A.; Prod’hom, G.; Greub, G. Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Ver. 2012, 36, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, M.L.; Júnior, M.A.B.; de Almeida, V.M.; Pereira, W.V.S. MALDI-TOF as a tool for microbiological monitoring in areas considered aseptic. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonello, R.M.; Riccardi, N. How we deal with Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA, MRSA) central nervous system infections. Front. Biosci. 2022, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, A.F.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; Penadés, J.R. Staphylococcus aureus in Animals. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, A.C.; Yebra, G.; Gong, X.; Goncheva, M.I.; Wee, B.A.; MacFadyen, A.C.; Muehlbauer, L.F.; Alves, J.; Cartwright, R.A.; Paterson, G.K.; et al. Evolutionary and Functional Analysis of Coagulase Positivity among the Staphylococci. mSphere 2021, 6, e0038121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.C.; Barbosa, L.N.; da Silva, G.R.; Otutumi, L.K.; Zaniolo, M.M.; Dos Santos, M.C.; de Paula Ferreira, L.R.; Gonçalves, D.D.; de Almeida Martins, L. Pet dogs as reservoir of oxacillin and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 143, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, M.; Joshi, P.R.; Paudel, S.; Acharya, M.; Rijal, K.R.; Ghimire, P.; Banjara, M.R. Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase Negative Staphylococci and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern from Healthy Dogs and Their Owners from Kathmandu Valley. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).