Abstract

Background/Objectives: It is recommended that patients with cirrhosis receive endoscopic screening for esophageal varices because of portal hypertension. However, patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) do not routinely undergo endoscopic examinations. Nevertheless, although bile acids may increase the incidence rate of colon polyps by inducing colonic epithelium cell damage, only a few studies have discussed colonic findings in PBC patients, which are believed to be related to cholestasis. The issues regarding PBC patients’ endoscopic characteristics are still unclear. Methods: This retrospective study was conducted at the Tri-Service General Hospital, Taiwan, and comprised data from patients aged >20 years diagnosed with primary biliary cholangitis between January 2000 and December 2018 after approval from the institutional review board. In these PBC patients, endoscopic findings were recorded, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy. Conclusions: In the PBC group, only 28 patients received EGD examinations. Among the 28 PBC patients who underwent EGD, 13 (46.4%) had EV, and there were no varices in the control group (p < 0.05). Patients with PBC also presented a higher incidence rate of colon polyps (50% vs. 14%; p < 0.001). The findings regarding the higher risks of esophageal varices and colon polyps support the rationale for endoscopic examination in PBC patients.

1. Introduction

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)—formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis—is an autoimmune disease of the liver. PBC is a chronic immune-driven injury to the small bile ducts that, with time, can eventually lead to biliary fibrosis and, finally, cirrhosis. It is characterized by biochemical and immunological markers of cholestasis and serum antimitochondrial autoantibodies (AMAs), and without adequate treatment, associated progressive chronic cholestasis will eventually develop into cirrhosis of the liver [1,2]. The early initiation of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the first-line drug treatment used to prevent the histologic features of PBC and significantly reduces progression to cirrhosis [3].

Effective biliary secretion is essential to maintaining hepatic detoxification and intestinal digestive function. Cholestasis is the impairment of bile formation and/or bile flow. Patients with cholestasis can be asymptomatic or manifest with fatigue, pruritus, right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort, and jaundice. With a diagnosis of PBC, aggressive treatment to improve bile duct inflammation is important to avoid late complications. Even when patients receive UDCA treatment, it can remain a progressive disease, with a risk of developing end-stage complications. Thus, additional treatments should be considered.

Patients with cirrhosis are recommended to receive endoscopic screening for esophageal varices and portal hypertension [4]. However, endoscopy results for patients with PBC are rarely reported because they do not routinely undergo endoscopic screening. Furthermore, although bile acids have a relationship with increased colon polyps by inducing colonic epithelium cell damage [5,6], only a few studies have discussed colonic findings in PBC patients. The issues regarding PBC patients’ endoscopic characteristics are still unclear. Recently, we published a study clarifying the increased risk of colon polyps and colon cancer in PBC patients. However, there were limitations in this population-based study, and further studies should be undertaken to address this issue.

Our study aims to evaluate esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy findings in PBC patients, which are believed to be related to cholestasis.

2. Materials and Methods

This study involved a 19-year retrospective observation conducted at the Tri-Service General Hospital, Taiwan. It comprised data from patients aged >20 years diagnosed with primary biliary cholangitis between January 2000 and December 2018 after approval from the institutional review board. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH IRB No. C202005015, approval date: 30 January 2020).

PBC diagnosis was made according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guideline of 2018. At least two of the following criteria had to be met to be labeled as PBC-positive: an elevation in alkaline phosphatase levels, the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies, or evidence of histology. Other PBC-specific autoantibodies, including sp100 and gp210, could also be used for diagnosis if AMA results were negative. The diagnosis was confirmed using medical records.

Patients in the control group were randomly selected from our health examination center using a gender ratio similar to that of the PBC group. Those excluded had a history of alcohol consumption, smoking, age < 20 years, or malignancy. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease and familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded.

Demographic characteristics (age, gender, hepatic comorbidities) and extra-hepatic autoimmune disorders were recorded (autoimmune thrombocytopenia, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), thyroid disorder, Sicca syndrome, and Raynaud’s disease). We gathered this data by reviewing medical histories.

Endoscopic findings were recorded for each patient who received endoscopic examinations, including EGD and colonoscopy. All endoscopic examinations were performed by endoscopists with a formal record. Esophageal varices, peptic ulcers, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), colon polyps, and pathological reports were all investigated. The severity of GERD was determined using the reflux esophagitis classification. GERD Gr. A is defined as a mucosal break no longer than 5 mm without extending between the tops of two mucosal folds. GERD Gr. B is defined as a mucosal break longer than 5 mm without extending between the tops of two mucosal folds. GERD Gr. C is defined as one or more mucosal breaks that are continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds involving less than 75% of the circumference. GERD Gr. D is defined as one or more mucosal breaks that are continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds involving more than 75% of the circumference. F1, F2, and F3 define the forms of varices according to the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension (JRSPH) classification criteria. F1 refers to small varices, meaning minimally elevated veins above the esophageal mucosal surface. F2 refers to medium varices, meaning torturous veins occupying <33% of the esophageal lumen. F3 refers to large varices, meaning torturous veins occupying >33% of the esophageal lumen.

Laboratory data were gathered for each subject related to the Child–Pugh (C-P) cirrhosis classification and extrahepatic autoimmune diseases. Laboratory findings included aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin levels. The severity of cirrhosis was based on the C-P classification and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores. C-P classification divides patients into three categories: A indicates good hepatic function, B indicates moderately impaired hepatic function, and C indicates advanced hepatic dysfunction. The scoring system used five clinical and laboratory markers to categorize patients: serum bilirubin, serum albumin, ascites, neurological disorder, and prothrombin time. Classification A is defined as a score of 5–6, classification B is a score of 7–9, and classification C is a score of 10–15. MELD scores of 6 (less sick) to 40 (grave) were recorded based on 3 objective variables (serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and institutional normalized ratio) to predict survival in patients with portal hypertension complications. MELD score I is <9, MELD score II is 10–19, MELD score III is 20–29, MELD score IV is 30–39, and MELD score V is ≥40.

All statistical analyses were performed using Graph-Pad Prism 7.0. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using Student’s unpaired t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the categorical variables, the Chi-squared test was used to clarify the difference.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Control and PBC Patients

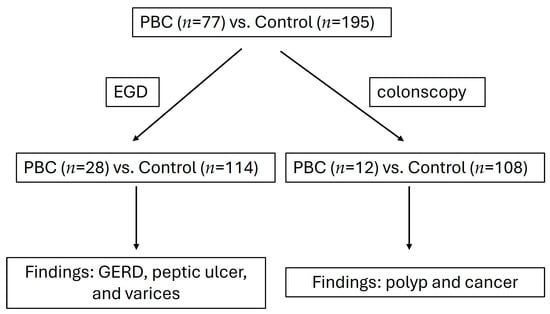

We collected and analyzed EGD and colonoscopy findings from PBC patients (n = 77) and the control group (n = 195) (Figure 1). In total, 28 PBC patients and 114 control patients underwent EGD. In total, 12 PBC patients and 108 patients received colonoscopies. Previous studies report that PBC mainly develops in middle-aged women, which accords with our patients’ characteristics (Table 1). Among the 75 patients with PBC, women aged 40–60 accounted for 24% (18/75), and those aged more than years accounted for 57.3% (43/75). Patients with PBC showed a higher percentage of cirrhosis than patients in the control group. In total, 7 cirrhotic PBC patients were diagnosed with Child A, 13 patients were diagnosed with Child B, and 9 patients were diagnosed with Child C. In total, 37.6% of PBC patients developed cirrhosis. We diagnosed HBV infection based on positive hepatitis B antigen (HBs-Ag) results and HCV infection based on the presence of the HCV virus. Female patients with PBC had the highest incidence of HCV infection.

Furthermore, extra-liver autoimmune disorders were more common in PBC patients. In the study population, 17 PBC patients (22.6%) had extrahepatic autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune thyroid diseases (2 patients, 2.6%), Sjögren syndrome (8 patients, 10.6%), systemic lupus erythematosus (2 patients, 2.6%), and Sicca syndrome (3 patients, 3.9%). By contrast, only 0.5% of the control group had extrahepatic autoimmune diseases. Sjögren’s syndrome was the most common autoimmune comorbidity for both female and male patients with PBC (Table 1).

3.2. Esophagogastroduodenoscopic Findings

In total, 28 patients received EGD examinations in the PBC group, and 114 received EGD examinations in the control group. Among the 28 PBC patients who underwent EGD, 13 (46.4%) had esophageal varices. F1 esophageal varices predominated at 36% (10/28). Two PBC patients presented with F2 EV, and one patient had F3 EV. Six patients had GV, and one patient with PBC was noted to have a higher incidence rate of peptic ulcers, especially duodenal ulcers, demonstrating a significant difference. There was no difference in the GERD incidence rates between the two groups (Table 2).

3.3. Colonoscopy Findings

Patients with PBC presented a higher incidence rate of colon polyps than those in the control group (50% vs. 14%; p < 0.001). There was no difference in polyp locations between the two groups. Cecum intubation was achieved for all PBC and control patients. Pathology diagnosis showed no adenocarcinoma in our study patients. Tubular adenoma was the most frequent finding, especially low-grade dysplasia (Table 3).

3.4. Indications for Esophagogastroduodenoscopic Examination

In total, eight PBC patients underwent EGD because of symptoms indicating GERD, seven because of epigastric pain, five because of anemia, five patients because of dyspepsia, and three because of a positive family history. There was no significant difference in indications (Table 4).

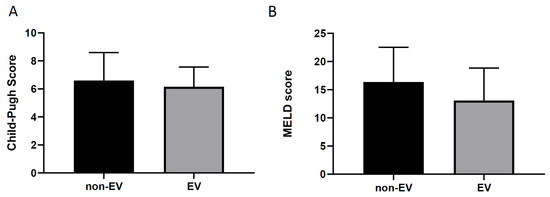

3.5. Severity of Cirrhosis in Variceal Bleeding

Of the 28 PBC patients who received EGD examinations, those with esophageal varices (EVs) showed no difference in age compared with the non-EV group. EVs were not rare in PBC patients, but those with EV did not show higher Child–Pugh or MELD scores (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Study design flowchart.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of control and PBC patients. PBC, primary biliary cholangitis. HBV, hepatitis B virus. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of control and PBC patients. PBC, primary biliary cholangitis. HBV, hepatitis B virus. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

| Control (195) | PBC (77) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (128) | Male (67) | Female (64) | Male (13) | |

| Average (yrs) | 51.67 | 45.9 | 64.6 ± 1.78 | 46.6 ± 5.6 |

| Cirrhotic PBC | ||||

| -Child A | 0 | 0 | 6 (7.79%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| -Child B (%) | 0 | 0 | 12 (15.6%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| -Child C (%) | 0 | 0 | 7 (9%) | 2 (2.6%) |

| Non-cirrhotic PBC (%) | 0 | 0 | 39 (50.6%) | 9(11.7%) |

| HBV (%) | 8 (4.1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| HCV (%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 | 7 (9%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Non-BC (%) | 117 (60%) | 65 (33.3%) | 55 (71.4%) | 11(14.3%) |

| Extra-liver autoimmune disorder | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 7 (12.1%) | 0 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome (%) | ||||

| Autoimmune thrombocytopenia (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3%) | 0 |

| Raynaud’s disease (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3%) | 0 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.6%) | 0 |

| Sicca syndrome (%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.9%) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3%) |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3%) | 0 |

| Total (%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 15 (19.5%) | 2 (2.6%) |

Table 2.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopic findings. EVs, esophageal varices. GVs, gastric varices. GERD, gastro-esophageal reflux disease. * p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopic findings. EVs, esophageal varices. GVs, gastric varices. GERD, gastro-esophageal reflux disease. * p < 0.05.

| Control | PBC | |

|---|---|---|

| Total EGD (n) | 114 | 28 |

| EV F1 (n,%) | 0 | 10 (36%) * |

| EV F2 (n,%) | 0 | 2 (7%) |

| EV F3 (n,%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

| GV (n,%) | 0 | 6 (21%) * |

| GERD (B, C, D) (n,%) | 6 (5.2%) | 2 (7%) |

| Gastric ulcer (n,%) | 6 (5.2%) | 5 (18%) |

| Duodenal ulcer (n,%) | 1 (0.8%) | 8 (29%) * |

| Gastritis (n,%) | 40 (35.1%) | 23 (82%) |

| Bulbitis (n,%) | 5 (4.3%) | 9 (32%) |

Table 3.

Colonoscopic findings. * p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Colonoscopic findings. * p < 0.05.

| Control | PBC | |

|---|---|---|

| Total colon (n) | 64 | 12 |

| Polyp number | ||

| 0 | 55 (86%) | 6 (50%) * |

| ≥1 | 9 (14%) | 6 (50%) * |

| Average polyp number (confidence intervals) | 0.16 (0.05–0.25) | 0.75 * (0.2–1.3) |

| Tubular adenoma with mild dysplasia | 4 | 2 |

| Tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia | 1 | 1 |

| Tubular adenoma with moderate dysplasia | 1 | 0 |

| Villous tubular adenoma with moderate dysplasia | 0 | 1 |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 2 | 2 |

| Chronic colitis | 1 | 0 |

Table 4.

Indications for esophagogastroduodenoscopic examination.

Table 4.

Indications for esophagogastroduodenoscopic examination.

| Patient Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Acid reflux | 8 | 28.6 |

| Epigastric pain | 7 | 25 |

| Anemia | 5 | 17.8 |

| Dyspepsia | 5 | 17.8 |

| Family history of GI tract malignancy | 3 | 10.7 |

Figure 2.

Cirrhotic conditions in PBC patients. (A): EVs, esophageal varices. (B): EVs, esophageal varices.

4. Discussion

Previous studies in the literature have investigated the association between bile acids and colon polyps. PBC is a cholestasis disease believed to lead to epithelium damage, eventually progressing to pathological and structural changes [7,8,9]. Nevertheless, few data are available as to the prevalence of colonic polyps in PBC patients. This includes EGD findings. In this study, we present the EGD and colonoscopy endoscopic results for PBC patients. In our previous population-based retrospective cohort study conducted in Taiwan, PBC patients were noted to have a higher incidence rate for the development of colon polyps and benign neoplasms compared with the general population. To obtain more information on this issue, we conducted this retrospective study. The strength of our research is in filling the gaps in current PBC endoscopic data.

The EGD findings showed a higher prevalence of EVs, gastric varices (GVs), and duodenal ulcers in PBC patients. The EV prevalence in our research was consistent with a previous study conducted in Taiwan in 1990, which found esophageal varices at the late stages of liver cirrhosis in 13 out of 30 consecutive patients diagnosed with PBC (43%) [10]. A similar prevalence of gastro-esophageal varices in PBC patients has been reported in Western countries [11,12]. Nevertheless, in Taiwan, viral hepatitis infection is the most common cause of liver cirrhosis leading to gastro-esophageal varices. Although research on the prevalence of gastro-esophageal varices is lacking compared with virus-related cirrhosis and PBC patients, the literature shows significantly higher EV prevalence in patients with hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis [13]. The difference may be explained by the extent of liver and biliary tract involvement, but this is an unconfirmed hypothesis that requires more exploration.

In our study, PBC patients more often had duodenal ulcers and gastritis. In 1995, a Taiwan cross-sectional study reported a 9.5% prevalence of duodenal ulcers in cirrhotic patients, significantly higher than 4.0% in healthy controls [14]. The results meet our expectations. Given these findings, the severity of cirrhosis, the presence of H. pylori, and portal hypertension do not seem to play an important role in the increased incidence of duodenal ulcers. Peptic ulcers may be the result of other factors, such as reduced prostaglandins, decreased gastric acid secretion, elevated serum gastrin, impaired mucus secretion, a reduction in the potential difference in the gastric mucosa, and portal hypertensive gastropathy. In our study, we also found no difference in the severity of cirrhosis between the EV and non-EV groups. Therefore, this research provided new insights into endoscopic examination for PBC patients in screening EVs, GVs, and duodenal ulcers.

Our colonoscopy results showed more colon polyps in PBC patients. The prevalence of colorectal polyps in asymptomatic people in Taiwan ranges from 16.3% to 27.4% [15,16], although there is limited data on the prevalence of colon polyps in PBC patients. Previous studies show that cholecystectomy is a risk factor in colon cancer development [17,18]. In PBC, the continuous secretion of bile acids caused by cholecystectomy may share the same pathway. The relationship between the prevalence of colon polyps and cholestasis has been widely discussed, and some contradictory results have been reported [19,20,21]. However, the mechanism has not been fully explained. Our previous study identified a higher incidence of colon polyps and colon cancer in the PBC group [22]. The pathogenetic mechanism governing the higher risk of colon polyps in PBC may result from cholestasis. Excess bile acids are regarded as potential risk factors for colon cancer [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In the same vein, a comprehensive analysis of bile acid profiles enrolled 65 treatment-naïve patients with PBC and 109 healthy controls, showing a significant elevation in total serum bile acid levels in the treatment-naïve PBC patients; this may be the reason why the prevalence of colon lesions was higher in the PBC group [31]. UDCA was the first and only drug approved for the treatment of PBC until 2016, when obeticholic acid (OCA) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration. OCA activates the Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) and inhibits hepatic bile production, possibly altering the microbiota and bile acids in the gastrointestinal tract. Used with UDCA, this may have different impacts on the colon epithelium. Further studies should be conducted to investigate these changes [32,33,34,35,36]. Because of the small sample size of PBC patients receiving colonoscopy in this study, our findings should be regarded as a pilot observation, and the sample size should be expanded to clarify this issue.

In preventing colon cancer, screening is usually performed with fecal testing for occult blood and endoscopic examinations involving sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Endoscopic screening may lower the risk of developing colon cancer by 25%. Given that most colorectal cancers develop from benign polyps that can be detected and removed via endoscopy, PBC patients should receive colonoscopy examinations because of their higher prevalence of colon polyps. These findings may also apply to other cholestatic diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or hepatitis virus-related malignancy. However, more studies should be performed to clarify this issue. The clinical guidelines for colorectal cancer screening in Taiwan strongly recommend the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) as the primary colorectal cancer screening tool, as it has been found to reduce the associated mortality rate by 10%. Indeed, Italian data shows that FIT screening can reduce the mortality rate of colorectal cancer by up to 22%. Thus, we should also consider applying the FIT to PBC patients.

A Mendelian randomization study identified a significant association, suggesting that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly Crohn’s disease, is a risk factor for developing PBC. Although this is known to be a risk factor for colon cancer, no patient was diagnosed with IBD in our study. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and malignancy were also not found in the study groups. Thus, we observed that PBC patients have a higher incidence rate of colon polyps, which may be due to the disease itself.

In the 28 patients who received EGD, despite the higher prevalence rate of duodenal ulcers, anemia was not the leading reason for PBC patients to receive EGD. PBC patients received EGD because of GERD symptoms and epigastric pain. There were no gastric malignancies identified during EGD. According to their medical records, not every patient who received an EGD had undergone a CLO test (a commercial trade name—Campylobacter-Like Organism), one of the rapid urease tests used to check for Helicobacter Pylori infection. Regardless, no positive CLO test results were noted. Thus, cholestasis seems not to be a risk factor for Helicobacter Pylori infection. Of the 28 PBC patients who received EGD, 47% had EVs (F1, 36%; F2, 7%; F3, 4%), and only 17.8% of these received EGD because of anemia. This finding suggests that anemia is not necessarily an indication for EGD in PBC patients.

About two-thirds of cirrhotic patients may develop esophageal varices, and this emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis. Given the advancement in medical treatments for the chronic management of portal hypertension (e.g., propranolol or nadolol) and the development of rubber band ligation for esophageal variceal obliteration, cirrhotic patients should receive EGD screening. In our findings, only 36.3% of PBC patients at our hospital received EGD examination, in whom EV and GV incidence rates were high (47% for EVs and 21% for GVs). Interestingly, PBC patients in the EV and non-EV groups showed no significant differences in cirrhotic severity according to the Child–Pugh and MELD scores (Figure 2). Thus, routine EGD screening for all newly diagnosed PBC patients should be performed. Primary prophylactic use of non-selective beta-blockers and endoscopic management should be considered. However, due to the retrospective design and limited sample size of this study, more research should be performed to clarify this issue. The effectiveness of primary screening in PBC patients has not been elucidated; to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to point out this issue.

PBC exhibits a variety of autoimmune features; Sjögren’s syndrome is the most common disorder, with a prevalence rate of 25% [37]. In our study, Sjögren’s syndrome accounted for about 12.1% of the PBC group, which was higher than for the control group. However, the prevalence is not as high as the results. This may be due to racial differences. HCV infection in PBC patients occurs at about 5.4% [38,39]. In our study, we found a similar condition. Floreani et al. found that HCV infections in patients with PBC may increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and highlighted the importance of HCV eradication. In our study, many patients also received anti-HCV treatments. With the advancements in anti-HCV treatments, the incidence rate will decrease [40]. Given the higher prevalence rates of HBV and HCV in Asia, this may lead to different issues in hepatitis virus-infected PBC patients.

Due to the beneficial effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonism in PBC pathogenetic disease, as highlighted by the effective use of fibrates, related studies are under investigation [41]. Several meta-analyses have consistently illustrated that PPAR agonists have significant biochemical benefits in UDCA-inadequate PBC, confirming their roles as disease-modifying agents. Unlike UDCA, PPAR agonists will not increase the number of bile salts in the digestive tract, and this may have different physiological effects on the colon epithelium.

However, this study is limited, as it was based on retrospective data and small study numbers. The main limitations are a lack of data and endoscopic findings obtained from a single center. Baseline laboratory and endoscopic data was assessed retrospectively, which may introduce bias. Moreover, not all patients with PBC received endoscopic examinations, and this may have led to the results being underestimated. Given the absence of daily data, a further limitation of this study was our inability to accurately measure illness severity, instead relying on severity markers collected during endoscopy.

Our study was also non-randomized and retrospective; thus, unexpected bias may exist. We tried to compare PBC patients with the general population, with patients in the control group selected from our health examination center. In our hospital, many civilians and staff may come to our health examination center for regular checkups, meaning that they may be present in the general population. Thus, some selection bias may exist. Furthermore, most PBC patients are only considered after excluding endemic viral hepatitis B and C. This often leads to HCV/HBV-infected PBC patients being diagnosed after HBV/HCV diagnosis and treatment. Thus, a future prospective clinical trial with a larger population is necessary to establish the relationship between PBC, EGD, and colonoscopy results.

5. Conclusions

The PBC patients in our study had higher incidence rates for EVs (grade F1), GVs, and duodenal ulcers upon EGD. More colon polyps were also seen in these patients’ colonoscopic results. However, given the small sample size, further studies should be performed to justify the rationale of endoscopic examinations for PBC patients.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.-W.C. and P.-T.C.; software, P.-T.C.; validation, H.-W.C. and P.-T.C.; formal analysis, P.-T.C.; investigation, H.-W.C.; resources, Y.-J.L.; data curation, H.-W.C. and P.-T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-W.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.-J.L.; visualization, P.-T.C.; supervision, Y.-J.L.; project administration, Y.-J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH IRB No. C202005015, approval date: 30 January 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved the application for signature exemption on the ICF. Assessed as low risk, this protocol is subject to follow-up review annually. The Board is organized and operated in compliance with International Conference on Harmonization (ICH)/WHO Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and applicable laws and regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the content of this study and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBC | Primary biliary cholangitis |

| MELD | Model for End-Stage Liver Disease |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| EGD | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| EVs | Esophageal varices |

| GVs | Gastric varices |

References

- Kaplan, M.M.; Gershwin, M.E. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 353, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strassburg, C.P.; Manns, M.P. Autoimmune tests in primary biliary cirrhosis. Baillieres Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2000, 14, 585–599. [Google Scholar]

- Poupon, R.E.; Lindor, K.D.; Parés, A.; Chazouillères, O.; Poupon, R.; Heathcote, E.J. Combined analysis of the effect of treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid on histologic progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2003, 39, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalak, M.; Lake, J.; Mattek, N.; Eisen, G.; Lieberman, D.; Zaman, A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: Data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 65, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitahata, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoshida, O.; Tokumoto, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Furukawa, S.; Kumagi, T.; Hirooka, M.; Takeshita, E.; Abe, M.; et al. Ileal mucosa-associated microbiota overgrowth associated with pathogenesis of primary biliary cholangitis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, B.S.; Wynder, E.L. Metabolic epidemiology of colon cancer. Fecal bile acids and neutral sterols in colon cancer patients and patients with adenomatous polyps. Cancer 1977, 39, 2533–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajouz, H.; Mukherji, D.; Shamseddine, A. Secondary bile acids: An underrecognized cause of colon cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S.K.; Choudhury, A.; Kumar, A.; Mahmud, N.; Lee, G.H.; Tan, S.-S.; Thanapirom, K.; Arora, V.; Nakayama, N.; Li, J.; et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Ung, T.T.; Kim, N.H.; Jung, Y.D. Role of bile acids in colon carcinogenesis. World J. Clin. Cases 2018, 6, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.; Lee, S.D.; Huang, Y.S.; Wu, J.C.; Tsai, Y.T.; Tsay, S.H.; Lo, K.J. Primary biliary cirrhosis in Taiwan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1990, 5, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C.; Zein, C.O.; Gomez, J.; Soldevila–Pico, C.; Firpi, R.; Morelli, G.; Nelson, D. Prevalence and predictors of esophageal varices in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanwala, I.; McMeekin, P.; Walters, R.; Mells, G.; Alexander, G.; Newton, J.; Shah, H.; Coltescu, C.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hudson, M.; et al. A validated clinical tool for the prediction of varices in PBC: The Newcastle Varices in PBC Score. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.D.; Zhu, Q.H.; Huang, Z.M.; Chen, X.R.; Jiang, Z.C.; Xu, S.H.; Jin, K. Predictors of esophageal varices in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis: A retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.S.; Lin, H.C.; Lee, F.Y.; Hou, M.C.; Lee, S.D. Prevalence of duodenal ulcer in cirrhotic patients and its relation to Helicobacter pylori and portal hypertension. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 1995, 56, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.W.; Hsu, P.I.; Chuang, H.Y.; Tu, M.S.; Mar, G.Y.; King, T.M.; Wang, J.H.; Hsu, C.W.; Chang, C.H.; Chen, H.C. Prevalence and risk factors of asymptomatic colorectal polyps in Taiwan. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 985205. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.H.; Wu, M.C.; Peng, Y.; Wu, M.S. Prevalence of advanced colonic polyps in asymptomatic Chinese. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 4731–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Jeng, W.J.; Hsu, C.M.; Kuo, C.J.; Su, M.Y.; Chiu, C.T. Gallbladder Polyps Are Associated with Proximal Colon Polyps. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2019, 2019, 9832482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, B.; Luo, L.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P. Cholecystectomy promotes colon carcinogenesis by activating the Wnt signaling pathway by increasing the deoxycholic acid level. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 71, Correction in Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.J.; Jin, E.H.; Lim, J.H.; Shin, C.M.; Kim, N.; Han, K.; Lee, D.H. Increased Risk of Cancer after Cholecystectomy: A Nationwide Cohort Study in Korea including 123,295 Patients. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.C.; Hu, Y.W.; Hu, L.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Chien, S.H.; Shen, C.C.; Yeh, C.M.; Chen, C.C.; Lin, H.C.; Yen, S.H.; et al. Risk of cancer in patients with cholecystitis: A nationwide population-based study. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönau, J.; Wester, A.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Hagström, H. Risk of cancer and subsequent mortality in primary biliary cholangitis: A population-based cohort study of 3052 patients. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023, 2, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.T.; Chien, W.C.; Chung, C.H.; Chen, P.J.; Huang, T.Y.; Chen, H.W. Risk of colon polyps and colorectal cancer in primary biliary cholangitis, a population-based retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, T.; Stepien, M.; López-Nogueroles, M.; Damms-Machado, A.; Sookthai, D.; Johnson, T.; Roca, M.; Hüsing, A.; Maldonado, S.G.; Cross, A.J.; et al. Prediagnostic plasma bile acid levels and colon cancer risk: A prospective study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Qu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, N.; Chen, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Lv, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Serum total bile acids in relation to gastrointestinal cancer risk: A retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 859716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocvirk, S.; O’kEefe, S.J. Influence of bile acids on colorectal cancer risk: Potential mechanisms mediated by diet-gut microbiota interactions. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2017, 6, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Chen, H. Detection and analysis of serum bile acid profile in patients with colonic polyps. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, C.M.; Bernstein, C.; Dvorak, K.; Bernstein, H. Hydrophobic bile acids, genomic instability, Darwinian selection, and colon carcinogenesis. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2008, 1, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, G.; Liu Don Shi, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, M.; Huang, X.; Lin, H. Quantitative Detection of 15 Serum Bile Acid Metabolic Products by LC/MS/MS in the Diagnosis of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202200720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Wang, T.; Shen, Y.; Xi, X.; Yang, L. Underestimated Male prevalence of primary biliary cholangitis in China: Results of a 16-yr cohort study involving 769 patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Seto, W.K.; Fung, J.; Lai, C.L.; Yuen, M.F. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cholangitis in the Chinese: A territory-based study in Hong Kong between 2000 and 2015. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2017, 8, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wei, Y.; Xiong, A.; Li, Y.; Guan, H.; Wang, Q.; Miao, Q.; Bian, Z.; Xiao, X.; Lian, M.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of serum and fecal bile acid profiles and interaction with gut microbiota in primary biliary cholangitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizsoltani, A.; Niknam, B.; Taghizadeh-Teymorloei, M.; Ghoodjani, E.; Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Alizadeh, E. Therapeutic implications of obeticholic acid, a farnesoid X receptor agonist, in the treatment of liver fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 189, 118249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samur, S.; Klebanoff, M.; Banken, R.; Pratt, D.S.; Chapman, R.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Loos, A.M.; Corey, K.; Hur, C.; Chhatwal, J. Long-term clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of obeticholic acid for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Price, R.R.; Watson, M.A.; McKee, D.D.; Moore, L.B.; Galardi, C.; Wilson, J.G.; Lewis, M.C.; Roth, M.E.; et al. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, C.D.; Simbrunner, B.; Baumgartner, M.; Campbell, C.; Reiberger, T.; Trauner, M. Bile acid metabolism and signalling in liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwong, E.K.; Puri, P. Gut microbiome changes in Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease & alcoholic liver disease. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, E.F.; James, O.F.; Jones, D.E. Patterns of autoimmunity in primary biliary cirrhosis patients and their families: A population-based cohort study. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housset, C.; Hirschauer, C.; Degos, F. False positive anti-HCV in biliary cirrhosis. Lancet 1991, 114, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Huang, H.H.; Lai, C.H.; Shih, Y.L.; Chang, W.K.; Hsieh, T.Y.; Chu, H.C. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Ann. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topi, S.; Gaxhja, E.; Charitos, I.A.; Collela, M.; Santacroce, L. Hepatitis C Virus: History and Current Knowledge. Gastroenterol. Insights 2024, 15, 676–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedian, B.; Babajani, N.; Bagheri, T.; Shirmard, F.O.; Pourfaraji, S.M. Efficacy and safety of PPAR agonists in primary biliary cholangitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.