Abstract

Metastases to the pancreas (PM), although rare, have been increasingly identified in recent years, especially among high-volume pancreatic centers. They are often asymptomatic and incidentally detected during follow-up examinations, even several years after the treatment of the primary tumor. In this scenario, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as a crucial diagnostic tool for PM, being capable of providing a detailed morphological characterization and safe and effective tissue acquisition for cytohistological examination. The aim of our study was to extensively review the current evidence concerning the role of EUS in the diagnosis of PM, specifically focusing on its morphological features, contrast-enhancement patterns, and tissue acquisition techniques.

1. Introduction

Metastases to the pancreas (PM) are relatively uncommon conditions, representing approximately 2–5% of all pancreatic malignancies in surgical and oncologic series, and up to 15% among autopsy studies [1,2,3]. Given that PM commonly mimics primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in clinical presentation and cross-sectional imaging, a definitive diagnosis is imperative, as management and prognosis differ substantially [4,5,6]. Since its advent [7,8,9], endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has gradually emerged as the cornerstone for the characterization of solid pancreatic lesions, being capable of providing unmatched spatial resolution for pancreatic parenchyma and enabling simultaneous tissue acquisition for cyto-histological diagnosis [10,11].

EUS-guided tissue acquisition (EUS-TA), including fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and fine-needle biopsy (FNB), is essential for the definitive cytohistological diagnosis of PM. Indeed, EUS-TA has been shown to be associated with high diagnostic accuracy rates and negligible adverse event rates for solid pancreatic lesions, including PM [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

In recent years, contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS) has further refined lesion characterization by accurately visualizing microvascular perfusion patterns [19]. Anyway, although CE-EUS enhances diagnostic confidence, tissue confirmation remains mandatory, as contrast patterns may overlap with neuroendocrine tumors and atypical PDAC [20,21].

Accurate diagnosis of PM is crucial, having a direct impact on their subsequent management. For instance, patients with isolated metastases may benefit from surgical resection with long-term survival, while the recognition of disseminated disease prevents unnecessary surgery and guides systemic therapy [22,23,24].

Given the increasing detection of PM in the era of long-term cancer survivorship and the key role played by EUS in this scenario, a comprehensive understanding of EUS morphology, CE-EUS patterns, and tissue-acquisition strategies is essential. Our narrative review aimed to summarize and discuss the current evidence regarding the role of EUS in diagnosing PM, specifically focusing on its morphological features, CE-EUS patterns, tissue acquisition techniques, and their clinical implications.

2. Literature Search

We performed a comprehensive literature search in the PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Embase databases up to September 2025 in order to identify relevant studies investigating the role of EUS in the diagnosis of PM.

The search included combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to pancreas, metastases, EUS, and tissue acquisition techniques.

The medical search strategy used the terms “pancreas,” “pancreatic,” “metastases,” “metastatic,” “secondary tumor,” “solid lesions”, “endoscopic ultrasound,” “endoscopic ultrasonography,” “EUS,” “endosonography,” “fine-needle aspiration,” “fine-needle biopsy,” “FNA,” “FNB,” “contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound,” and “CE-EUS” in various combinations, using the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT. The search was limited to English-language human studies. Additional relevant articles were carefully identified by manual screening of the reference lists of retrieved publications and pertinent reviews. Meeting abstracts, individual case reports, case series (<5 cases), review articles, position papers, editorials, commentaries, and book chapters were excluded from our review.

3. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound in Pancreatic Metastases

A total of 26 studies were included in the final analysis [4,5,10,12,13,14,15,16,20,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. All were retrospective in nature. Three were case series [10,32,36], sixteen were single-center studies [4,5,13,14,15,20,25,27,28,29,30,31,33,35,37,38], and seven were multi-center studies [12,16,22,26,34,39,40]. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics and demographics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological and endoscopic ultrasound features of the included studies. EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; CE-EUS: contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

3.1. Population Characteristics

The median age at diagnosis of PM ranged from 57 to 72 years, with a slight male predominance [4,5,12,13,14,15,16,20,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The largest included studies identified PM in approximately 1–6% of pancreatic masses sampled [5,10,13,14,15,20,26,27,28,30,34,38,39,40]. Most patients were asymptomatic or presented with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, or jaundice [12,14,15,16,25,27,30,35,39]. In several series, over two-thirds of cases were incidentally detected during oncologic follow-up imaging [16,27,30,36]. Notably, a long-time interval between the diagnosis of the primary tumor and the detection of PM, up to 25 years, was reported, especially among patients affected by renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [16,25,26,28]. Interestingly, Betes et al. noted that PM from lung carcinoma had a significantly shorter latency time than those from RCC [14]. Synchronous presentations, in which the PM was discovered concurrently with or shortly after the primary tumor, were observed in 10–30% of cases [15,16,25].

3.2. Primary Tumors

RCC consistently emerged as the predominant source of PM, accounting for 17–65% of cases among the included studies [5,10,15,16,22,25,26,27,28,29,33,36,40]. Other common primaries included lung carcinoma (8–38%), colorectal adenocarcinoma (4–18%), breast carcinoma (4–18%), melanoma (3–14%), and sarcomas or lymphomas (each 1–10%) [4,5,10,12,13,14,15,16,20,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Less common primaries reported include gastric adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate, thyroid, and gynecologic tumors [13,14,15,31,39]. The recent multi-center study by Cui et al. added valuable histopathologic detail, emphasizing the wide spectrum of tumors potentially metastasizing to the pancreas. Indeed, epithelial neoplasms represented 73% of cases, most often RCC, lung adenocarcinoma, and Müllerian-type carcinomas, while non-epithelial metastases originated from hematologic malignancies, sarcomas, and melanoma [34].

3.3. Size, Localization, and Focality

Mean lesion size ranged from 15 to 42 mm, with extremes from a few millimeters to over 13 cm [4,10,12,13,14,15,16,20,25,27,28,30,31,33,34,37,38,39]. Lesions were distributed throughout the gland, with a slight predilection for the pancreatic head (17–83%), followed by the body (9–73%) and the tail (7–27%) [4,5,12,14,15,16,20,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,37,38,39,40]. Multifocality was observed in approximately 10–25% of cases, particularly in RCC metastases [13,25,27,36,39].

3.4. Endoscopic Ultrasound Morphological Features

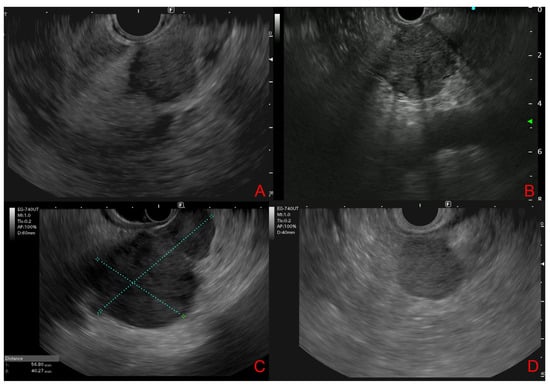

EUS provides a detailed morphological characterization of PM. PM is typically described as well-demarcated, hypoechoic, and homogeneous lesions, often oval or round in shape [4,10,12,15,16,20,22,25,27,30,31,35,37,39]. As compared to PDAC, which is typically irregular and hypoechoic with poorly defined borders, PM exhibits a clearer interface with surrounding parenchyma (marginal hypoechoic zone, MHZ) [31]. While PDAC is mostly hypovascular, PM frequently appears hypervascular [10,15,16,20]. Notably, pancreatic duct dilatation and parenchymal atrophy, hallmarks of PDAC, were uncommon in metastases, even when lesions were located within the head [31,33]. These features, together with well-defined margins, should promptly raise suspicion for a secondary rather than a primary pancreatic tumor. Aversano et al. [15] recently proposed a composite set of EUS features for PM, noting that the combination of hypoechoic echogenicity, hyper or moderate vascularity, oval or roundish shape with well-defined margins, and hardness on elastography was strongly associated with secondary lesions. Nevertheless, they emphasized that EUS morphology alone is insufficient to differentiate PM from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors or some solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, underscoring the final need for histologic confirmation.

EUS morphological features of PM are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound features of pancreatic metastases. (A,B): From renal cell carcinoma (solid, round, well-defined hypoechoic lesions). (C): From hepatocellular carcinoma (bilocular hypoechoic lesion). (D): From Lymphoma (nodular, hypo-isoechoic lesion with a relatively well-defined boundary).

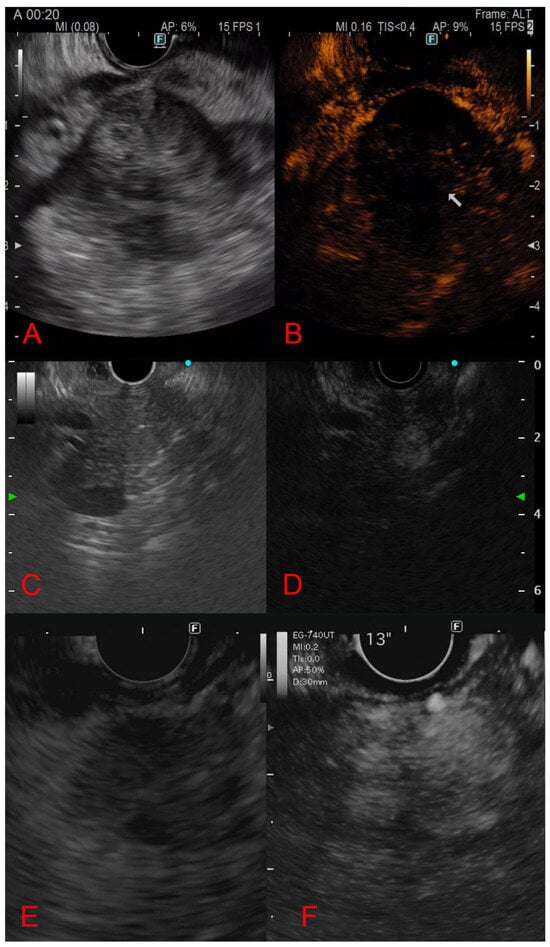

3.5. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound Features

CE-EUS has a well-known added value to the evaluation of pancreatic masses and, consequently, of PM, providing valuable information on their vascularity. Studies assessing CE-EUS in PM reported that the majority of metastatic lesions, especially from RCC, display hyperenhancement in the arterial phase [20,37], followed by rapid washout [20]. This vascular pattern contrasts sharply with the hypoenhancement typically observed in PDAC, which reflects its desmoplastic and hypovascular stroma [20]. In the study from Fusaroli et al. [37], hypervascularity was a consistent feature of RCC metastases, while hypovascular or hypo- or isoenhancing patterns were more common in PM from colorectal or breast carcinoma, concluding that the finding of a hyperenhancing lesion in a patient with a previous cancer history, especially if renal or hematological, should prompt EUS-TA.

The CE-EUS behavior of solid pancreatic lesions is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound behavior of solid pancreatic lesions. (A,B): Adenocarcinoma (hypoechoic lesion with hypo-enhancement). (C,D): Neuroendocrine tumor (hyper-enhancement in arterial phase). (E,F): Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma (arterial hyperenhancement with heterogeneous distribution).

3.6. Diagnostic Yield and Final Diagnostic Method

EUS-TA (EUS-FNA/B) is universally regarded as the cornerstone of diagnosis for PM [12,14,15,25]. Early experience from Fritscher-Ravens et al. [4] reported an EUS-FNA sensitivity of 88% with near-perfect specificity and negligible complication rates. Following single-center and multi-center studies [25,29,30,38,39], there was a confirmed accuracy of 85–92%, with diagnostic material obtained in over 90% of cases. More recent studies [15,16,34] consistently exceed 90–95% diagnostic yield, mainly due to EUS-FNB availability, larger-gauge systems, and improved cell-block preparation. Where described, the median number of needle passes through the lesion ranged from 2 to 3 [15,16,25,27,28,31,33,35,39]. The technical aspects and diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition in the included studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Technical aspects and diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition of the included studies. EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; FNA: fine needle aspiration; CT: computed tomography; US: ultrasound; FNB: fine needle biopsy.

The addition of immunohistochemistry (IHC) is critical to determine the primary origin, especially in patients with prior malignancies or ambiguous morphology [16,34]. In 2025, Cui et al. [34] showed the morphological overlap between PM and PDAC, emphasizing that EUS-FNB specimens are sufficient for extended IHC and even molecular testing, thereby confirming the current shift from cytology to histology-based diagnosis. Currently, EUS-FNB is the preferred modality for EUS-TA in most centers when PM is suspected, as it provides more intact tissue cores, allowing for cell block preparation, immunostaining, and molecular comparison with prior specimens [15,16]. Immunohistochemical markers of the most common malignancies metastasizing to the pancreas are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Immunohistochemical markers of the most common malignancies metastasizing to the pancreas.

3.7. Treatment and Outcomes

Management of PM should be patient-tailored and specifically guided by the primary tumor type, disease burden, and patient performance status in a multidisciplinary approach. Surgery should be considered whenever a potentially curative resection is feasible, particularly in RCC, with a reported good long-term survival after pancreatectomy in several studies [14,22,28,38]. Conversely, non-surgical strategies such as systemic anticancer therapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, or endoscopic palliation are generally applied in disseminated disease [4,15,27]. Prognosis is poor, especially in small-cell lung or breast cancer PM, matching that of the metastatic primary.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Over the past decades, EUS has redefined the diagnostic approach to PM, converting a historically post-surgical or autoptic finding into a clinically feasible diagnosis [1,2]. Although PM currently represents only 1–6% of pancreatic malignancies in large EUS series [5,10,13,14,15,20,26,27,28,30,34,38,39,40], the growing population of long-term cancer survivors has increased their recognition. RCC emerged as the most common primary tumor originating from PM, representing 17–65% of all diagnoses [5,10,15,16,22,25,26,27,28,29,33,36,40]. This evidence has remained stable over time, reflecting the prolonged survival of RCC patients and the tumor’s particular tropism for the pancreatic tissue [41]. Early reports like Fritscher-Ravens et al. [4], Mesa et al. [5], and DeWitt et al. [12] demonstrated the feasibility of EUS-FNA, but subsequent studies have consolidated its role as the first-line diagnostic tool. Large series and multi-center studies have confirmed a diagnostic accuracy exceeding 90%, with negligible complication rates [25,29,30,39,40]. EUS-FNB has been progressively integrated into FNA, enabling more tissue to be sampled and a major feasibility and accuracy of IHC and molecular comparison with the primary tumor. In recent studies by Spadaccini et al. [16] and Cui et al. [34], EUS-FNB provided sufficient tissue for extended immunophenotyping, marking a shift from cytology to histology-based diagnosis. These data align with those from previous literature findings, which have underscored the pivotal role of IHC in confirming the metastatic nature of pancreatic lesions and differentiating them from PDAC, when morphology alone was insufficient [27,40]. Advanced imaging techniques have also provided a significant contribution to the characterization of these lesions. In particular, CE-EUS allowed a real-time functional study, enabling a more accurate assessment of vascularity. Several studies have shown that most PM, especially those from RCC, display hyperenhancement in the arterial phase, contrasting with the hypovascular pattern of PDAC [20,37]. Fusaroli et al. [37] and Teodorescu et al. [20] confirmed that CE-EUS increases diagnostic confidence but cannot replace tissue confirmation, as hypovascular metastases from colorectal or breast carcinoma remain a frequent source of false negatives. EUS also plays a crucial role in differentiating malignant pancreatic lesions like PM and PDAC from benign inflammatory conditions (Table 5). In particular, autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) may present as a focal or nodular mass, either solitary or multiple, closely mimicking PDAC or metastatic lesions on cross-sectional imaging and conventional EUS [42]. No EUS feature alone is pathognomonic for focal AIP or mass-forming chronic pancreatitis (CP). Contrast-enhanced EUS studies have shown that focal AIP and inflammatory masses typically display an isoenhancing or mildly hyperenhancing pattern compared with the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma, in contrast to the hypovascular appearance of PDAC. In this challenging diagnostic setting, the major added value of EUS lies in the possibility of performing EUS-TA, allowing histological assessment and immunostaining to rule out cancer [43,44]. These findings emphasize that the strength of EUS lies not only in morphology but also in its capability to integrate vascular and cytologic information during a single procedure. From a clinical standpoint, EUS-based diagnosis directly influences management strategies. The detection of a secondary tumor in the pancreas rather than a primary pancreatic tumor significantly alters prognosis and treatment [24,45]. A multidisciplinary team approach is crucial for the proper diagnosis and treatment of PM. Endosonographers, radiologists, pathologists, oncologists, and surgeons should deeply cooperate to interpret imaging and histological findings in the context of the patient’s history. Despite the marked progress achieved, current evidence is limited by the retrospective nature of all the included studies, their relatively small sample size, and heterogeneity in reporting. Only a few studies have prospectively compared FNA and FNB or standardized CH-EUS descriptors [20,46,47,48,49].

Table 5.

Differential diagnosis of pancreatic metastases by endoscopic ultrasound features. EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; CE-EUS: contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is also emerging as an ancillary technique in EUS, especially after the introduction of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) technology, which has completely revolutionized image classification. In fact, CNN automatically learns hierarchical features from images, allowing for more accurate and robust classification results and high-performance prediction, allowing real-time lesion characterization, segmentation, and classification [50]. There is a scan of literature evidence about the detection of PM with AI. In particular, Kuwahara T et al. published a retrospective study about the application of CNN using EfficientNetV2-L (22 000 images generated from 933 patients), able to differentiate PDAC from other benign and malignant lesions, including PM, achieving an accuracy of 91.0%, sensitivity of 94%, and specificity of 82% [51].

In conclusion, EUS with EUS-TA currently represents the mainstay for the accurate diagnosis of PM, combining a very high accuracy with minimal morbidity. Furthermore, its combination with CH-EUS and modern EUS-FNB devices allows precision in both macroscopic and microscopic characterization, enabling more tailored therapeutic decisions. Future large multicentric prospective studies should aim to harmonize reporting standards, validate quantitative perfusion and elastographic metrics, and explore molecular profiling from EUS-FNB cores as a platform for personalized oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., A.M. and M.A.; resources, M.R., A.M., M.A., F.P.Z., R.F., D.S. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., A.M., M.A. and F.P.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.R., A.M., M.A., F.P.Z., R.F., D.S., S.C. and L.B.; visualization, M.R., A.M., M.A. and L.B.; supervision, F.R., C.M., R.D.M., G.S., L.B. and G.L.; project administration, A.M. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PM | Metastases to the pancreas |

| EUS | Endoscopic ultrasound |

| PDAC | Primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| EUS-TA | EUS-guided tissue acquisition |

| FNA | Fine-needle aspiration |

| FNB | Fine-needle biopsy |

| CE-EUS | Contrast-enhanced EUS |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| MHZ | Marginal hypoechoic zone |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| MPD | Main pancreatic duct |

| AIP | Autoimmune pancreatitis |

| CP | Chronic pancreatitis |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

References

- Adsay, N.V.; Andea, A.; Basturk, O.; Kilinc, N.; Nassar, H.; Cheng, J.D. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: An Analysis of a Surgical and Autopsy Database and Review of the Literature. Virchows Arch. 2004, 444, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, E.; Shimizu, M.; Itoh, T.; Manabe, T. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: Clinicopathological Study of 103 Autopsy Cases of Japanese Patients. Pathol. Int. 2001, 51, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.; Green, L.; Reddy, V.; Kluskens, L.; Bitterman, P.; Attal, H.; Prinz, R.; Gattuso, P. Pancreatic Masses: A Multi-Institutional Study of 364 Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsies with Histopathologic Correlation. Diagn. Cytopathol. 1998, 19, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritscher-Ravens, A.; Sriram, P.V.J.; Krause, C.; Atay, Z.; Jaeckle, S.; Thonke, F.; Brand, B.; Bohnacker, S.; Soehendra, N. Detection of Pancreatic Metastases by EUS-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001, 53, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, H.; Stelow, E.B.; Stanley, M.W.; Mallery, S.; Lai, R.; Bardales, R.H. Diagnosis of Nonprimary Pancreatic Neoplasms by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2004, 31, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantopoulou, C.; Kolliakou, E.; Karoumpalis, I.; Yarmenitis, S.; Dervenis, C. Metastatic Disease to the Pancreas: An Imaging Challenge. Insights Imaging 2012, 3, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohm, W.D.; Phillip, J.; Hagenmüller, F.; Classen, M. Ultrasonic Tomography by Means of an Ultrasonic Fiberendoscope. Endoscopy 1980, 12, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilmann, P.; Jacobsen, G.K.; Henriksen, F.W.; Hancke, S. Endoscopic Ultrasonography with Guided Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy in Pancreatic Disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1992, 38, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M.J.; Hawes, R.H.; Tao, L.C.; Wiersema, L.M.; Kopecky, K.K.; Rex, D.K.; Kumar, S.; Lehman, G.A. Endoscopic Ultrasonography as an Adjunct to Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology of the Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Tract. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1992, 38, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, L.; Borotto, E.; Cellier, C.; Roseau, G.; Chaussade, S.; Couturier, D.; Paolaggi, J.A. Endosonographic Features of Pancreatic Metastases. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1996, 44, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouw, R.E.; Barret, M.; Biermann, K.; Bisschops, R.; Czakó, L.; Gecse, K.B.; de Hertogh, G.; Hucl, T.; Iacucci, M.; Jansen, M.; et al. Endoscopic Tissue Sampling—Part 1: Upper Gastrointestinal and Hepatopancreatobiliary Tracts. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Jowell, P.; LeBlanc, J.; McHenry, L.; McGreevy, K.; Cramer, H.; Volmar, K.; Sherman, S.; Gress, F. EUS-Guided FNA of Pancreatic Metastases: A Multicenter Experience. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 61, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.L.; Odronic, S.I.; Springer, B.S.; Reynolds, J.P. Solid Tumor Metastases to the Pancreas Diagnosed by FNA: A Single-institution Experience and Review of the Literature. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015, 123, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betés, M.; González Vázquez, S.; Bojórquez, A.; Lozano, M.D.; Echeveste, J.I.; García Albarrán, L.; Muñoz Navas, M.; Súbtil, J.C. Metastatic Tumors in the Pancreas: The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration. Rev. Española De Enfermedades Dig. 2019, 111, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversano, A.; Lissandrini, L.; Macor, D.; Carbone, M.; Cassarano, S.; Marino, M.; Giuffrè, M.; De Pellegrin, A.; Terrosu, G.; Berretti, D. The Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS) in Metastatic Tumors in the Pancreas: 10 Years of Experience from a Single High-Volume Center. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaccini, M.; Conti Bellocchi, M.C.; Mangiavillano, B.; Fantin, A.; Rahal, D.; Manfrin, E.; Gavazzi, F.; Bozzarelli, S.; Crinò, S.F.; Terrin, M.; et al. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: A Multicenter Analysis of Clinicopathological and Endosonographic Features. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Koizumi, K.; Shionoya, K.; Jinushi, R.; Makazu, M.; Nishino, T.; Kimura, K.; Sumida, C.; Kubota, J.; Ichita, C.; et al. Comprehensive Review on Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Tissue Acquisition Techniques for Solid Pancreatic Tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, M.J.; McPhail, M.J.W.; Possamai, L.; Dhar, A.; Vlavianos, P.; Monahan, K.J. EUS-Guided FNA for Diagnosis of Solid Pancreatic Neoplasms: A Meta-Analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 75, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaroli, P.; Napoleon, B.; Gincul, R.; Lefort, C.; Palazzo, L.; Palazzo, M.; Kitano, M.; Minaga, K.; Caletti, G.; Lisotti, A. The Clinical Impact of Ultrasound Contrast Agents in EUS: A Systematic Review According to the Levels of Evidence. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 84, 587–596.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodorescu, C.; Bolboaca, S.D.; Rusu, I.; Pojoga, C.; Seicean, R.; Mosteanu, O.; Sparchez, Z.; Seicean, A. Contrast Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Metastases. Med. Ultrason. 2022, 24, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, M.; Kamata, K.; Imai, H.; Miyata, T.; Yasukawa, S.; Yanagisawa, A.; Kudo, M. Contrast-enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Pancreatobiliary Diseases. Dig. Endosc. 2015, 27, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.; Mitry, E.; Hammel, P.; Sauvanet, A.; Nassif, T.; Palazzo, L.; Malka, D.; Delchier, J.-C.; Buffet, C.; Chaussade, S.; et al. Pancreatic Metastases: A Multicentric Study of 22 Patients. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2004, 28, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, R. Pancreatic Metastases from Renal Cell Carcinoma: The State of the Art. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Edil, B.H.; Cameron, J.L.; Pawlik, T.M.; Herman, J.M.; Gilson, M.M.; Campbell, K.A.; Schulick, R.D.; Ahuja, N.; Wolfgang, C.L. Pancreatic Resection of Isolated Metastases from Nonpancreatic Primary Cancers. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 3199–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hajj, I.I.; LeBlanc, J.K.; Sherman, S.; Al-Haddad, M.A.; Cote, G.A.; McHenry, L.; DeWitt, J.M. Endoscopic Ultrasound–Guided Biopsy of Pancreatic Metastases. Pancreas 2013, 42, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.; Si, Q.; Caraway, N.; Mody, D.; Staerkel, G.; Sneige, N. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas Diagnosed by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration: A 10-year Experience. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2014, 42, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekulic, M.; Amin, K.; Mettler, T.; Miller, L.K.; Mallery, S.; Stewart, J. Pancreatic Involvement by Metastasizing Neoplasms as Determined by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine Needle Aspiration: A Clinicopathologic Characterization. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2017, 45, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, S.L.T.; Yugawa, D.; Chang, K.H.F.; Ena, B.; Tauchi-Nishi, P.S. Metastatic Neoplasms to the Pancreas Diagnosed by Fine-needle Aspiration/Biopsy Cytology: A 15-year Retrospective Analysis. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2017, 45, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Shen, R.; Tonkovich, D.; Li, Z. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Diagnosis of Secondary Tumors Involving Pancreas: An Institution’s Experience. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2018, 7, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq, M.; Bhutani, M.S.; Ross, W.A.; Raju, G.S.; Gong, Y.; Tamm, E.P.; Javle, M.; Wang, X.; Lee, J.H. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography in Evaluation of Metastatic Lesions to the Pancreas. Pancreas 2013, 42, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijioka, S.; Matsuo, K.; Mizuno, N.; Hara, K.; Mekky, M.A.; Vikram, B.; Hosoda, W.; Yatabe, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Kondo, S.; et al. Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound and Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration in Diagnosing Metastasis to the Pancreas: A Tertiary Center Experience. Pancreatology 2011, 11, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Lee, Y.; Rodriguez, T.; Lee, J.; Saif, M.W. Secondary Tumors of the Pancreas: A Case Series. Anticancer. Res. 2012, 32, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M.A.; Bohy, K.; Singal, A.; Xie, C.; Patel, B.; Nelson, M.E.; Bleeker, J.; Askeland, R.; Abdullah, A.; Aloreidi, K.; et al. Metastatic Tumors to the Pancreas: Balancing Clinical Impression with Cytology Findings. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2022, 26, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Amed, M.; Reid, M.D.; Xue, Y. Secondary Pancreatic Tumors in Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy: Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Morphological Diagnostic Challenges. Hum. Pathol. 2025, 161, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béchade, D.; Palazzo, L.; Fabre, M.; Algayres, J.-P. EUS-Guided FNA of Pancreatic Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003, 58, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioakim, K.J.; Sydney, G.I.; Michaelides, C.; Sepsa, A.; Psarras, K.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Salla, C.; Nikas, I.P. Evaluation of Metastases to the Pancreas with Fine Needle Aspiration: A Case Series from a Single Centre with Review of the Literature. Cytopathology 2020, 31, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaroli, P.; D’Ercole, M.C.; De Giorgio, R.; Serrani, M.; Caletti, G. Contrast Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography in the Characterization of Pancreatic Metastases (with Video). Pancreas 2014, 43, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, A.K.; Ustun, B.; Aslanian, H.R.; Ge, X.; Chhieng, D.; Cai, G. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Diagnosis of Secondary Tumors Involving the Pancreas: An Institution’s Experience. Cytojournal 2016, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardengh, J.C.; Lopes, C.V.; Kemp, R.; Venco, F.; de Lima-Filho, E.R.; dos Santos, J.S. Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration in the Suspicion of Pancreatic Metastases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layfield, L.J.; Hirschowitz, S.L.; Adler, D.G. Metastatic Disease to the Pancreas Documented by Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine-needle Aspiration: A Seven-year Experience. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2012, 40, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, F.; Thalhammer, S.; Klimpfinger, M. Tumour Evolution and Seed and Soil Mechanism in Pancreatic Metastases of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacelli, M.; Zaccari, P.; Petrone, M.C.; Della Torre, E.; Lanzillotta, M.; Falconi, M.; Doglioni, C.; Capurso, G.; Arcidiacono, P.G. Differential EUS Findings in Focal Type 1 Autoimmune Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Endosc. Ultrasound 2022, 11, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Cao, X.; Nabi, G.; Zhang, F.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Guo, C. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound for Differential Diagnosis of Autoimmune Pancreatitis: A Meta-Analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2024, 12, E1134–E1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.B.; Cereatti, F.; Drago, A.; Grassia, R. Focal Autoimmune Pancreatitis: A Simple Flow Chart for a Challenging Diagnosis. Ultrasound Int. Open 2020, 06, E67–E75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperti, C.; Pozza, G.; Brazzale, A.R.; Buratin, A.; Moletta, L.; Beltrame, V.; Valmasoni, M. Metastatic Tumors to the Pancreas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Minerva Chir. 2016, 71, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- van Riet, P.A.; Erler, N.S.; Bruno, M.J.; Cahen, D.L. Comparison of Fine-Needle Aspiration and Fine-Needle Biopsy Devices for Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Sampling of Solid Lesions: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, P.; Nassar, A.; Gomez, V.; Raimondo, M.; Woodward, T.A.; Crook, J.E.; Fares, N.S.; Wallace, M.B. Comparison of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy versus Fine-Needle Aspiration for Genomic Profiling and DNA Yield in Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Kamata, K.; Kudo, M. Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Puncture for the Patients with Pancreatic Masses. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itonaga, M.; Kitano, M.; Kojima, F.; Hatamaru, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Tamura, T.; Nuta, J.; Kawaji, Y.; Shimokawa, T.; Tanioka, K.; et al. The Usefulness of EUS-FNA with Contrast-enhanced Harmonic Imaging of Solid Pancreatic Lesions: A Prospective Study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacelli, M.; Lauri, G.; Tabacelia, D.; Tieranu, C.G.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Săftoiu, A. Integrating Artificial Intelligence with Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Early Detection of Bilio-Pancreatic Lesions: Current Advances and Future Prospects. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2025, 74, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, T.; Hara, K.; Mizuno, N.; Haba, S.; Okuno, N.; Kuraishi, Y.; Fumihara, D.; Yanaidani, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Yasuda, T.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Using Deep Learning Analysis of Endoscopic Ultrasonography Images for the Differential Diagnosis of Pancreatic Masses. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.