Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle biopsy (FNB) is one of the techniques applied for sampling subepithelial lesions (SELs) of the gastrointestinal tract. Elastography and contrast-enhanced evaluation could permit identification of different patterns among areas of the lesions, depending on their consistence and the presence of vital cells or necrosis. Targeting a specific area when performing FNB in the case of large lesions could potentially permit an increase in accuracy and reduce the need for re-sampling. A 61-year-old woman was admitted reporting severe abdominal pain. The patient underwent cholecystectomy many years ago. She had no known family history of gastrointestinal, hepatic, biliary, or pancreatic disease. Laboratory tests were normal. A computed tomography scan showed a large lesion between the stomach and the pancreatic body, suspected to originate from the gastric wall. An endoscopic view showed a large bulging into the gastric lumen and EUS identified a lesion originating from the muscular layer of the gastric wall. Elastography and contrast-enhanced EUS identified two different areas, one softer with lower enhancement (A) and the other harder with higher enhancement after contrast injection (B). FNB was performed targeting both the areas, sending samples for separate histological evaluation. Histology showed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), finding differences in amount of necrotic and neoplastic cells between the two areas. EUS-FNB guided by elastography and/or contrast-enhanced EUS could identify differences within large SELs, allowing targeting of areas more likely to collect diagnostic samples.

1. Introduction

Advanced techniques were developed in the field of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with the main purpose of improving the characterization of lesions that can be found during the examination (pancreatic cysts, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, biliary system tumors, hepatocellular carcinoma, metastasis, gastric subepithelial lesion [SEL], etc.) [1,2]. Currently, in clinical practice, contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography (CE-EUS), contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography (CH-EUS), and endoscopic ultrasound elastography (E-EUS) can be added to standard EUS examination [3]. These techniques permit morphological evaluation of lesions, focusing on specific findings to predict the diagnosis and even to target a better area for guiding the needle for fine-needle biopsy (FNB). Indeed, EUS tissue acquisition (TA) through FNB is an effective technique to obtain a diagnosis, even in the context of SELs [4]. In fact, SELs pose a diagnostic challenge because of intralesional heterogeneity, where viable tumor and necrotic regions may coexist. This heterogeneity may reduce the yield of standard biopsy approaches, so the use of complementary tools could permit identification of a specific area for acquiring larger and better samples during EUS-FNB. Consequently, an understanding of the application of CE-EUS, CH-EUS, and E-EUS for sampling could increase the diagnostic accuracy of large SELs. Herein, we present a case of a large subepithelial gastric lesion following the CARE guidelines for case reporting [5], and through a literature review of these techniques, we discuss the EUS findings and tool application for guiding EUS-TA. This case highlights the diagnostic value of advanced EUS modalities (CE-EUS and E-EUS) in revealing intralesional heterogeneity within a gastric SEL.

2. Case Presentation Section

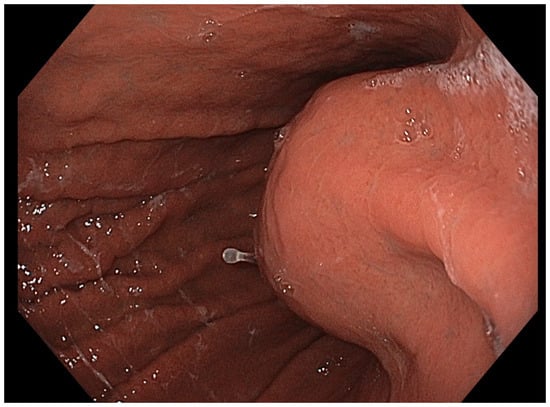

A 61-year-old woman in otherwise good health was admitted to our institute reporting severe abdominal pain. The patient underwent cholecystectomy many years ago. He had no known family history of gastrointestinal, hepatic, biliary, or pancreatic disease. Laboratory tests were normal at admission, and even neoplastic markers were negative. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) scan showed a large (37 × 34 mm) lesion at the gastric body, next to the pancreatic body, suspected to originate from the gastric wall. Specifically, the CT scan findings of the lesion showed regular margins with a small central necrotic area and post-contrast enhancement. A direct endoscopic view showed a large bulging into the gastric lumen with a normal overlying mucosa (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic image demonstrating a well-circumscribed, smooth bulge in the gastric wall with intact and normal-appearing mucosa, consistent with a gastric subepithelial lesion.

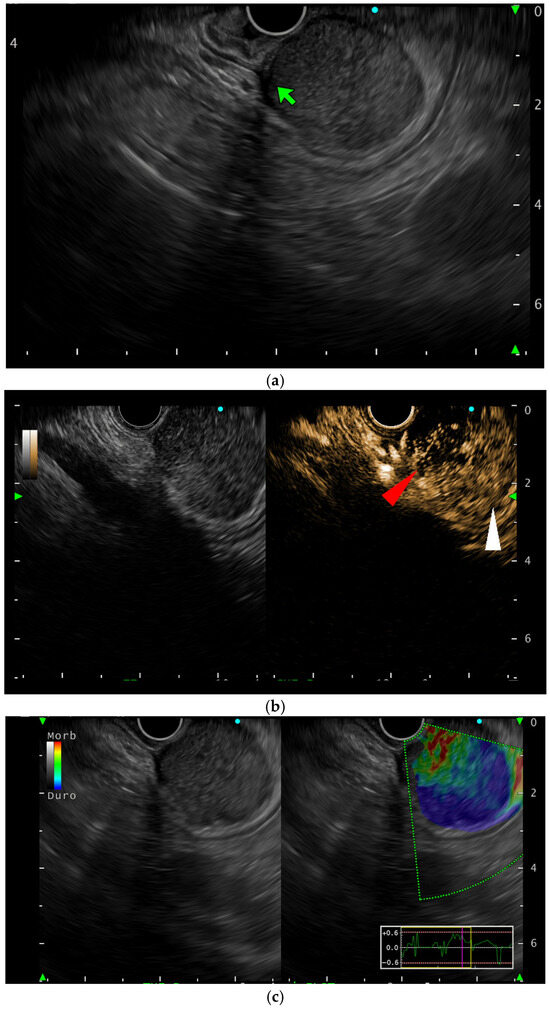

EUS was performed to evaluate the origin of the lesion, which arose from the muscular layer (4th) of the gastric wall (Figure 2a). Moreover, the lesion appeared hypoechoic and heterogeneous, with regular borders. It exhibited a heterogeneous contrast enhancement pattern after injection of ultrasonographic contrast dye (SonoVue): a hypoenhancing region (area A) and a hyperenhancing region (area B) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

EUS view of the lesion: (a) B-mode showing the lesion originating from the 4th layer (green arrow); (b) contrast-enhanced view showing the two different areas (area A: red arrow; area B: white arrow); (c) elastography showing the two different areas: area B is blue (stiff) while area A is green (soft).

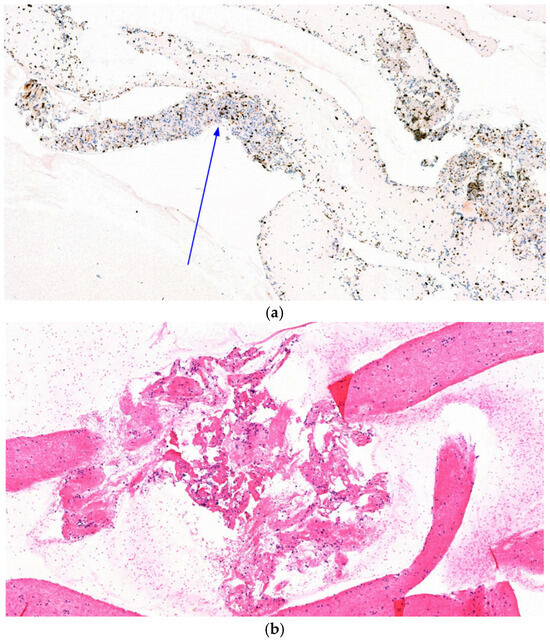

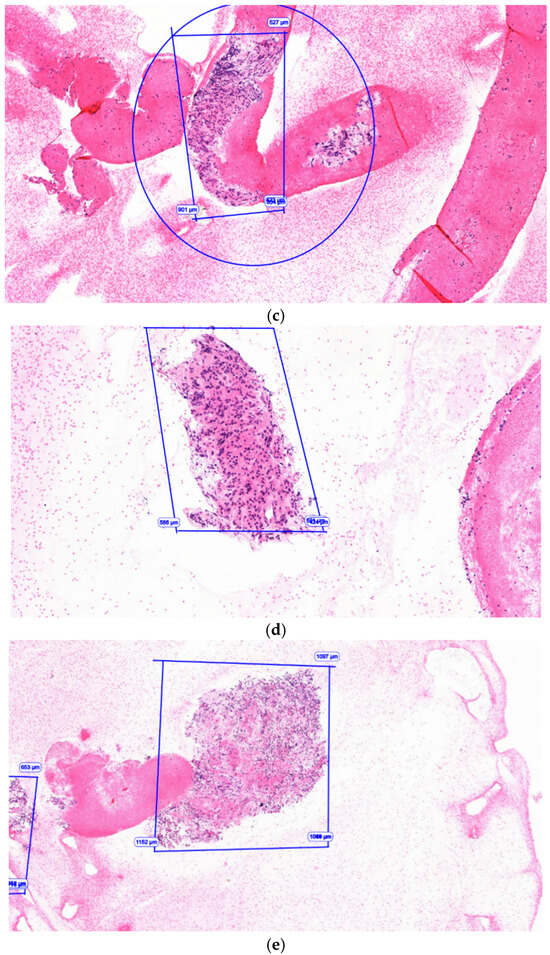

E-EUS confirmed different stiffness between the two areas; elastography and contrast-enhanced EUS revealed two distinct regions: a firm, hyperenhancing area (B) and a softer, hypoenhancing area (A) (Figure 2c). FNB was performed, targeting both the areas through the use of a Franseen-tip needle (22 gauge) with the guidance of CE-EUS and E-EUS, introducing the needle once for each targeted area, and samples were sent separately for histological evaluation. Both samples were of high-quality according to the pathologist evaluation, showing an immunohistochemistry positive for DOG1, CD34, and CD117, and the final diagnosis was consistent with a mixed-type gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) according to WHO 2019 classification. However, the Ki-67 labeling index exceeded 6% (Figure 3a), a value that some studies associate with higher recurrence risk, suggesting a potentially underestimated malignant potential. More specifically, the histology of area A revealed a spindle cell neoplasm with interlacing fascicles and focal epithelioid features, as well as a single necrotic area (Figure 3b). On the other hand, area B showed a similar neoplastic proliferation, again with mixed spindle and epithelioid morphology, but with more extensive necrotic areas (Figure 3c). Therefore, the marked difference in enhancement and stiffness between area A (hypoenhancing, soft) and area B (hyperenhancing, stiff) corresponded histologically to areas with differing degrees of necrosis and regressive changes (Figure 3d,e). The patient was sent to the abdominal surgeons to undergo gastric resection.

Figure 3.

Histology examination: (a) Ki-67-positive cells (arrow); (b) area A: spindle cell histology in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. H&E. 100×; (c) area A: regressive and necrotic changes in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). 100×; (d) area B: epithelioid area in a gastric GIST. 100×. H&E. (e) Large necrotic area in sample B. H&E. 100×.

3. Discussion

EUS examination include a wide armamentarium of advanced tools permitting identification of deep findings for more precise characterization of a lesion, especially SELs, which are more precisely differentiated through the use of EUS. GISTs are the most commonly identified SEL in the upper GI tract. Approximately 80% of GI mesenchymal tumors are GISTs, and approximately 10% to 30% of GISTs are malignant [6]. No specific EUS findings of the lesion are predictive for malignancy, but size is the only consistently definitive predictive factor [7,8]. Moreover, CE-EUS and E-EUS are two techniques permitting an increase in the accuracy of the EUS findings in characterizing the type of lesion. CE-EUS is based on the principle of contrast microbubbles, which are small spheres of gas encapsulated in a lipid membrane, reflecting ultrasound waves differently than the surrounding tissues. The resonance of the microbubbles at specific ultrasound frequencies results in a signal amplification effect that enhances the visibility of the tissues and structures being examined [9]. CE-EUS could distinguish between GISTs and benign SELs, with a sensitivity, specificity, and AUROC of 89%, 82%, and 0.89, respectively, and it also represents a useful tool to predict the malignant potential of GISTs with a sensitivity, specificity, and AUROC curve of 96%, 53%, and 0.92, respectively [10]. Another study evaluating 54 patients with SELs, 40 of which were GISTs, showed better diagnostic performance of CH-EUS vs. B-mode EUS alone in differentiating GISTs from leiomyoma and also in risk stratification of GISTs, even if they do not consider TA. In addition, in the setting of high-grade GISTs, CH-EUS showed an improvement in diagnostic accuracy [11]; that is why we scheduled CE-EUS from the beginning, and the irregular pattern of the enhancement permitted us to suspect malignancy. In addition, comparison of CE-EUS for tissue sampling and conventional EUS-TA for the diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions showed a similar diagnostic sensitivity between the two techniques, concluding that CE-EUS-guided TA does not need to be used routinely [12]; nonetheless, the differences in the enhancement of the contrast were very clear, and we performed needle passes in both lesions to have a higher probability of accurate diagnosis. Data evaluating CE-EUS-guided FNB vs. standard EUS-FNB showed the need for fewer needle passes in CE-EUS-guided FNB compared to the standard EUS-FNB group in the context of an equal diagnostic accuracy rate [13]. The lack of significant differences in the reduction in needle passes and side effects was also confirmed in a meta-analysis including seven studies. Authors reported 90.9% of diagnoses made by CE-EUS compared to 88.3% by conventional EUS (p = 0.14), and moreover, the diagnosis was made through a single step in 70.9% of CE-EUS and in 65.3% of EUS (p = 0.24) [14]. The differences seen in the lesion through CE-EUS in our case were also confirmed in E-EUS, which analyses tissue stiffness, giving the operator a real-time image of the lesion represented with a spectrum of different colors (from blue/hard tissue to red/soft tissue), which could also follow specific classification systems [15]. Our lesion, indeed, had a soft (green) area (area A) and a stiff (blue) area (area B). In a review including studies published in the last five years, authors currently consider EUS-TA mandatory, but they underline how the use of CH-EUS and E-EUS can be helpful in diagnosis and prognostic assessment, especially for SELs [16]. Actually, according to the recent technical review published by the European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE), there is not enough evidence to recommend E-EUS use to target tissue for EUS-sampling, even if it can be a useful tool for tissue characterization [17]. The use of E-EUS for targeting lesions through FNA was not superior to B-mode EUS-FNA in TA for histologic samples of pancreatic lesions, but it was not studied in large SELs, which still remains unexplored. However, the authors suggest there could be different results from its association with TA using fine-needle biopsy (FNB) [18], as performed in our case. Later, Ohno et al. evaluated the role of E-EUS-guided FNB in the histological diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions. Unfortunately, the authors found that E-EUS may reflect tissue composition in pancreatic tumors, but it cannot affect the quality nor quantity of the tissue obtained [19]. No data are available about targeting extrapancreatic lesions through E-EUS, nor with FNA or with FNB, so our case is among the first in the literature evaluating its usefulness in targeting SELs. Our case showed unexpected findings due to the presence of a higher percentage of necrotic tissue in the sample from area B, which we expected to be mainly composed of neoplastic cells compared to area A according to the CE-EUS and E-EUS, while area A was composed of neoplastic cells in the majority of the sample. One explanation could be the higher percentage of inflammatory tissue in the hyperenhanced area (area B), which leads to the production of more necrotic tissue. Limitations of our case include the lack of histology after surgery, as the patient belonged to another institute and has not yet undergone surgery. In addition, we should consider the fact that FNB samples only a minimal part of the area of interest, making it limited in representing the lesion or a specific area of it.

4. Conclusions

Currently, EUS-FNB remains the gold standard of TA for SELs, even if no recommendations are available regarding the use of CE-EUS and E-EUS as useful tools to better guide the needle passes during FNB. Specific data are lacking in a setting of gastric SELs. Therefore, our case shows slight differences in samples when the needle is guided by the abovementioned techniques, suggesting that further studies could identify specific applications of CE-EUS and E-EUS in the context of large SELs. These findings also underscore how EUS-guided evaluation can non-invasively suggest variations in tumor biology within the same lesion.

Author Contributions

G.E.M.R.: manuscript writing, design, analyses, supervision, methodology, and image provision; S.R.: writing, image provision, and comments; M.C.S.: writing and comments; L.M.: writing and comments; M.T.: writing and comments; E.D.: writing and comments; N.B.: writing and comments; G.I.: writing and comments; G.R. (Gabriele Rancatore): writing and comments; M.G.: writing and comments; D.L.: writing and comments; G.R. (Giuseppe Rizzo): writing and comments; M.P.: writing and comments; D.Q.: writing and comments; P.M. writing and comments; I.T.: supervision, methodology, comments, and data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical review and approval were waived for the single case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guilabert, L.; Nikolìc, S.; de-Madaria, E.; Vanella, G.; Capurso, G.; Tacelli, M.; Maida, M.; Vladut, C.; Knoph, C.S.; Quintini, D.; et al. Endoscopic ultrasound for pancreatic cystic lesions: A narrative review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2025, 12, e001893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, S.; Guilabert, L.; Vanella, G.; Vladut, C.; La Mattina, G.; Infantino, G.; D’Amore, E.; Knoph, C.S.; Rizzo, G.E.M. Endoscopic Ultrasound as a Diagnostic Tool for the Mediastinum and Thorax. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, M.I.; Seicean, A.; Pojoga, C.; Hagiu, C.; Seicean, R.; Sparchez, Z. Contrast-enhanced guided endoscopic ultrasound procedures. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Tamura, T.; Kawaji, Y.; Tamura, T.; Itonaga, M.; Ashida, R.; Shimokawa, T.; Kojima, F.; Hayata, K.; et al. Value of image enhancement of endoscopic ultrasound for diagnosis of gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. DEN Open 2025, 5, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.; CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013201554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.; Sarlomo-Rikala, M.; Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum. Pathol. 1999, 30, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.H.; Park, D.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, C.W.; Heo, J.; Song, G.A. Is it possible to differentiate gastric GISTs from gastric leiomyomas by EUS? World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 3376–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, M.; Tominaga, K.; Sugimori, S.; Machida, H.; Okazaki, H.; Yamagami, H.; Tanigawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Watanabe, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. Internal hypoechoic feature by EUS as a possible predictive marker for the enlargement potential of gastric GI stromal tumors. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 75, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Kudo, M. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound. Dig. Endosc. 2014, 26, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.Y.; Tao, K.G.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wu, K.M.; Shi, J.; Zeng, X.; Lin, Y. Value of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography in differentiating between gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A meta-analysis. J. Dig. Dis. 2019, 20, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefort, C.; Gupta, V.; Lisotti, A.; Palazzo, L.; Fusaroli, P.; Pujol, B.; Gincul, R.; Fumex, F.; Palazzo, M.; Napoléon, B. Diagnosis of gastric submucosal tumors and estimation of malignant risk of GIST by endoscopic ultrasound. Comparison between B mode and contrast-harmonic mode. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.R.; Jeong, S.-H.; Kang, H.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Cho, J.H. Comparison of contrast-enhanced versus conventional EUS-guided FNA/fine-needle biopsy in diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Chen, M.-J. Is contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy better than conventional fine needle biopsy? A retrospective study in a medical center. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 6138–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposto, G.; Massimiani, G.; Galasso, L.; Santini, P.; Borriello, R.; Mignini, I.; Ainora, M.E.; Nicoletti, A.; Zileri Dal Verme, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. Endoscopic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Fine-Needle Aspiration or Biopsy for the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Solid Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, M.; Hookey, L.; Bories, E.; Pesenti, C.; Monges, G.; Delpero, J. Endoscopic Ultrasound Elastography: The First Step towards Virtual Biopsy? Preliminary Results in 49 Patients. Endoscopy 2006, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanese, M.; Spadaccini, M.; Facciorusso, A.; Franchellucci, G.; Colombo, M.; Andreozzi, M.; Ramai, D.; Massimi, D.; De Sire, R.; Alfarone, L.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound and Gastric Sub-Epithelial Lesions: Ultrasonographic Features, Tissue Acquisition Strategies, and Therapeutic Management. Medicina 2024, 60, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facciorusso, A.; Arvanitakis, M.; Crinò, S.F.; Fabbri, C.; Fornelli, A.; Leeds, J.; Archibugi, L.; Carrara, S.; Dhar, J.; Gkolfakis, P.; et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue sampling: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical and Technology Review. Endoscopy 2025, 57, 390–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiu, M.; Sparchez, Z.; Rusu, I.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Seicean, R.; Pojoga, C.; Seicean, A. Direct Comparison of Elastography Endoscopic Ultrasound Fine-Needle Aspiration and B-Mode Endoscopic Ultrasound Fine-Needle Aspiration in Diagnosing Solid Pancreatic Lesions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, E.; Kawashima, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Iida, T.; Nishio, R.; Uetsuki, K.; Yashika, J.; Yamada, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; et al. The role of EUS elastography-guided fine needle biopsy in the histological diagnosis of solid pancreatic lesions: A prospective exploratory study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.