Abstract

Distinguishing between tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs) and brain tumors in multiple sclerosis (MS) can be challenging. A progressive course is highly common with brain tumors in MS and no single neuroimaging technique is foolproof when distinguishing between the two. We report a case of a 41-year-old female with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis, who had a suspicious lesion within the left frontal hemisphere, without a progressive course. The patient experienced paresthesias primarily to her right hand but remained stable without any functional decline and new neurological symptoms over the four years she was followed. The lesion was followed with brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, positron emission tomography–computed tomography scans, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Together, these scans favored the diagnosis of a TDL, but a low-grade tumor was difficult to rule out. Examination of serial brain MRI scans showed an enlarging lesion in the left middle frontal gyrus involving the deep white matter. Neurosurgery was consulted and an elective left frontal awake craniotomy was performed. Histopathology revealed a grade II astrocytoma. This case emphasizes the importance of thorough and continuous evaluation of atypical MRI lesions in MS and contributes important features to the literature for timely diagnosis and treatment of similar cases.

1. Introduction

The concurrence of glioma and relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) is uncommon. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is diagnosed by clinical and radiological criteria meeting the 2017 McDonald’s Criteria [1]. In patients with tumefactive MS (an atypical variant of MS with large isolated demyelinated plaque), differentiating between tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs) and glioma can be complicated [2]. For instance, some atypical TDLs may resemble gliomas and conversely, early-stage gliomas may mimic MS. This diagnostic dilemma may lead to a delay in diagnosis and could potentially affect the long-term clinical outcomes in such patients. TDLs are usually defined as large (>2 cm) demyelinating lesions with/without mass effect, perilesional edema, or gadolinium enhancement, which could mimic brain tumors radiologically and clinically [2]. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a sensitive technique for depicting demyelinating lesions in MS patients, but when used alone it fails to provide an accurate diagnosis in many cases of atypical TDLs that mimic a tumor. The definitive diagnosis is often made only after a surgical biopsy or resection of the lesion. Clinical suspicion of a brain tumor in MS usually arises if a patient experiences a steady progression of symptoms or neurological deficits in the presence of a TDL. We report a patient without a progressive course, who met clinical and MRI criteria for the diagnosis of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), with one of the lesions initially described as tumefactive (a TDL was deemed more likely than a neoplasm based on brain MRI imaging), which was later found to be a primary diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II). The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this case report.

2. Case Presentation

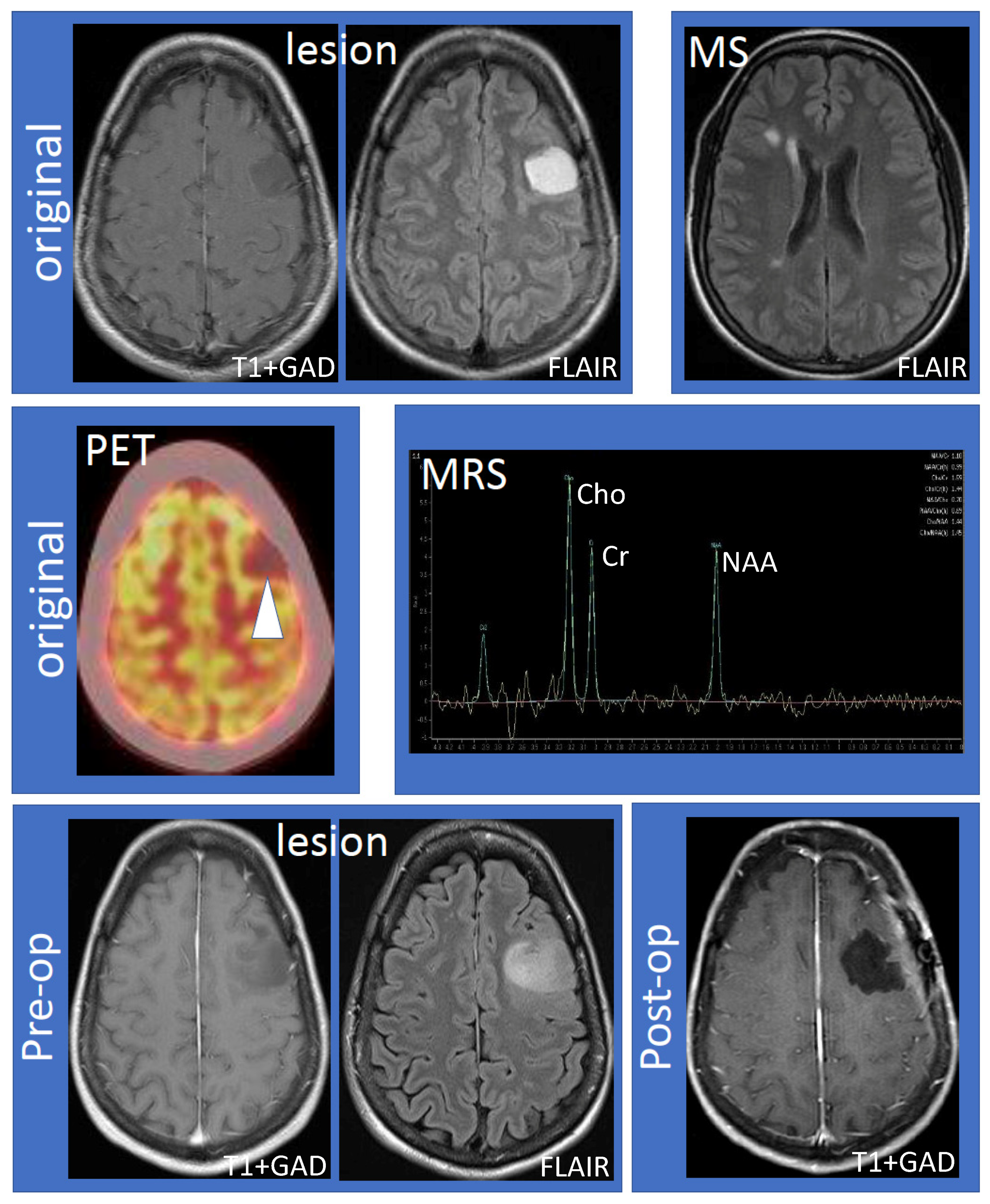

The 41-year-old female (non-smoker with a history of ulcerative colitis and celiac disease) had the onset of her MS 14 years ago, characterized by sensory symptoms of the lateral three fingers of the right hand, which resolved completely over several months. Seven years later, she experienced a second relapse characterized by paresthesias to her right hand, which spread to the medial aspect of her right arm, torso, leg, and toes. Following the second attack, she was diagnosed with RRMS based on MRI and clinical criteria. The initial MRI showed a large lesion (hypointense, non-enhancing on T1; hyperintense on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging) within the left frontal hemisphere involving the cortex and adjacent white matter (Figure 1, top row, “lesion”). Multiple white matter lesions were seen in both cerebral hemispheres compatible with MS (Figure 1, top row, “MS”). Focal hyperintensity was also observed in the right dorsal column of the cervical spinal cord at the C5–6 vertebral body level. Further evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG PET-CT) showed that the lesion was hypometabolic (Figure 1, middle row, “PET”). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) revealed decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA) with an NAA/creatine (Cr) ratio of 1.1 (Figure 1, middle row, “MRS”). The choline (Cho) was elevated, the Chol/Cr ratio was high at 1.59, and the Cho/NAA was 1.44. A significant lactate peak was not demonstrated. Neurosurgical and neuroradiological consultation suggested that the lesion in the left frontal hemisphere was consistent with a TDL in MS. Glatiramer acetate was initiated and the patient remained stable for the next four years without relapse or MRI activity. The patient had an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) of 1.0 since her diagnosis, without any evidence of confirmed disability progression or functional decline. The left frontal hemispheric lesion was followed over four years with serial MRI scans, which showed that the lesion increased in size with a mild mass effect involving the left middle frontal gyrus and underlying white matter (Figure 1, bottom row, “lesion”). There was interval stability of demyelinating plaques in the brain and cervical spinal cord. Neurosurgery was reconsulted and an elective left frontal awake craniotomy with the total resection of the lesion was carried out. Tissue diagnosis revealed primary left frontal diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II), 1p19q non-co-deleted, O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) methylated (46.5%), isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) R132H mutation, and loss of ATRX (alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation X-linked) expression. Post-operatively the patient experienced mild expressive dysphasia and was discharged on a tapering dose of dexamethasone. Following surgery, the patient received radiotherapy (54 Gray in 30 fractions) followed by temozolomide (6-cycle regime) for six months as an adjuvant treatment. She experienced a seizure, which was successfully treated with levetiracetam (750 mg) orally twice daily. She was on glatiramer acetate (20 mg) subcutaneously once daily throughout her course, and her MS remained stable by clinical and MRI criteria. Follow-up MRIs showed no recurrence of the glioma (Figure 1, bottom row, “post-op”) and stable white matter, ovoid, and periventricular lesions consistent with MS.

Figure 1.

Work-up and progression of the left frontal lobe lesion. The top row shows the large, non-enhancing lesion distinct from MS lesions (left to right: T1 following gadolinium administration (T1 + GAD) and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) showing the lesion; FLAIR showing MS lesions). The middle row shows hypometabolism of the lesion using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography imaging and results of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). MRS values are as follows: N-acetylaspartate (NAA)/creatine (Cr) 1.10, NAA/Cr(h) 0.99, choline (Cho)/Cr 1.59, Cho/Cr(h) 1.44, NAA/Cho 0.70, NAA/Cho(h) 0.69, Cho/NAA 1.44, and Cho/NAA(h) 1.45. The bottom row shows that the lesion increased in size compared to the original MRI (“pre-op”) and successful resection of the lesion (“post-op”). Abbreviations: MS: multiple sclerosis; PET: positron emission tomography; MRS: magnetic resonance spectroscopy; Pre-op: pre-operative; Post-op: post-operative.

3. Discussion

Differentiating between TDLs and brain tumors is challenging, particularly in the early stages of brain cancer. In this patient, diagnostic delay likely occurred because she was clinically stable, the lesion occurred in the setting of MS diagnosis (early in disease) and multiple imaging techniques could not adequately distinguish between TDL and early glioma. In addition to standard brain MRI imaging, the patient underwent FDG-PET-CT, which was hypometabolic (favoring TDL), and MRS, which was equivocal (Cho/NAA ratio = 1.44; >1.72 highly correlates with high-grade glioma [3]). The co-occurrence of glioma and MS in the same patient is uncommon, and most of the previously reported cases had high-grade astrocytic tumors that developed after MS diagnosis [4].

TDLs and brain tumors may share several characteristics, including size (>2 cm), gadolinium enhancement pattern, and a predilection for the frontal and parietal lobes. Importantly, several studies have attempted to distinguish between TDLs and brain tumors. For example, a study by Abdoli and Freedman [2] found that in contrast to TDLs, brain tumors in MS more commonly occurred in late or established MS, evolved over a few months, showed symptoms consistent with space-occupying lesions (cortical symptoms, raised intracranial pressure), had mostly a progressive course, and the lesion typically had more mass effect, necrosis, and perilesional edema and contained calcification or hemorrhage. Remarkably, the patient presented in this report had none of these findings.

Considering that there has been no recent review on this topic, we conducted an up-to-date topical review of the cases of gliomas in persons living with MS. A literature search was done on MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus (Elsevier), and Google (internet search) using the following search terms: multiple sclerosis, glioma, tumefactive lesion, brain tumor, astrocytoma, ependymomas, and oligodendroglioma. Case reports or case series reporting gliomas in an individual with MS and published in the English language since 2012 were included. We found 14 articles published in the last eight years (2012–2020) (Table 1). There were 16 patients (seven females, nine males), of which 13 had RRMS and 3 had SPMS. Table 2 presents a brief summary and classification of the glioma cases identified in people living with MS. Fourteen tumors were located in the frontal and parietal lobes. The most commonly reported gliomas were glioblastomas/astrocytomas, followed by oligodendrogliomas. Importantly, in contrast to the patient presented in this report, the vast majority of the cases presented with a progressive course or new neurological symptoms. Unfavorable clinical outcomes were mostly observed in elderly patients with high-grade gliomas who were either in palliative care or had refused interventional procedures. Tumor recurrence was observed in two cases.

Table 1.

Topical review of recently reported cases of gliomas in MS patients.

Table 2.

Summary and classification of the identified glioma cases in patients with MS.

Low-grade glioma in an MS patient may pose a diagnostic dilemma as the MRI findings of low-grade gliomas may be similar to those of TDLs [11]. Table 3 highlights the characteristic features for the differential diagnosis of MS, TDLs, and brain tumors in MS. A high level of clinical suspicion in atypical TDLs is required to differentiate glioma from MS [12]. A stereotactic biopsy and histopathological examination of the lesion aids in making a definitive diagnosis in equivocal cases [19]. It is a reliable procedure and has a diagnostic accuracy of 82–99% [20]. Total resection of the tumor without inflicting additional neurological deficits typically offers better patient outcomes for long-term survival [21].

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of MS, TDLs, and brain tumors in MS.

4. Conclusions

This case report highlights that slow-growing suspicious TDLs in MS patients with a non-progressive course should be carefully monitored by MRI over time to exclude low-grade gliomas. An elective craniotomy (with a total resection of the lesion) followed by radiation and chemotherapy may provide favorable outcomes in patients with concurrent RRMS and low-grade diffuse astrocytoma.

Author Contributions

M.C.L. and C.K. were involved in the clinical management of the patient, the preparation of all the images, and the manuscript writing, review, and editing. A.S. was involved in the manuscript writing, literature review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We have received no external funding. This work is based, in part, on work supported by the Saskatchewan MS Clinic and the office of the Saskatchewan MS Clinical Research Chair, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, SK, Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this case report are available within the article.

Patient’s Perspective on the Treatment

From her initial diagnosis, they had found a rather large “MS lesion” in her left fronto-temporal region. A local neurologist determined that it was a large tumefactive lesion and referred her to the MS clinic for a second opinion. It was on her initial visit to the MS clinic in September 2017 that she heard the news that it might not be an MS lesion, but a low-grade glioma. The team at the clinic activated a referral process that ended with her having a craniotomy to remove the tumor. She is profoundly grateful to the team at the Saskatchewan MS Clinic for how they expedited her care. This team, she can say with wholehearted confidence, saved her life. She is also indebted to her neurosurgeons. Today she is optimistic about her prognosis and the progression of her disease.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the individual living with MS described in this case report for providing her perspective on the treatment she received. We are also grateful to our clinical team at the Saskatchewan MS Clinic, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, SK, Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carroll, W. 2017 Mcdonald MS Diagnostic Criteria: Evidence-Based Revisions. Mult. Scler. J. 2018, 24, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Freedman, M. Neuro-Oncology Dilemma: Tumour or Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesion. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2015, 4, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeguchi, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Abe, K.; Shimizu, S.; Maruyama, T.; Nitta, M.; Abe, K.; Kawamata, T.; Kitagawa, K. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Differentiates Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions from Gliomas. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 26, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Serracino, H.; Damek, D.; Ney, D.; Lillehei, K.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B. Genetic Characterization of Gliomas Arising in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 109, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turatti, M.; Gajofatto, A.; Bianchi, M.; Ferrari, S.; Monaco, S.; Benedetti, M. Benign Course of Tumour-Like Multiple Sclerosis. Report of Five Cases and Literature Review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 324, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, E.; Majd, N.; Morris, J.; Karim, N.; Molano, J.; Colapietro, P.; Curry, R. ED-22 * concurrence of gliomas in patients with multiple sclerosis: Case report and literature review. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 16 (Suppl. 5), v70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvalho, A.; Linhares, P.; Castro, L.; Sá, M. Multiple Sclerosis and Oligodendroglioma: An Exceptional Association. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantero, V.; Balgera, R.; Bianchi, G.; Rossi, G.; Rigamonti, A.; Fiumani, A.; Salmaggi, A. Brainstem Glioblastoma in a Patient with Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 1733–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Wright, R.; Novo, J.; Arvanitis, L.; Stefoski, D.; Koralnik, I. Glioblastoma in Natalizumab-Treated Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantorová, E.; Bittšanský, M.; Sivák, Š.; Baranovičová, E.; Hnilicová, P.; Nosáľ, V.; Čierny, D.; Zeleňák, K.; Brück, W.; Kurča, E. Anaplastic Astrocytoma Mimicking Progressive Multifocal Leucoencephalopathy: A Case Report and Review of The Overlapping Syndromes. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishamchi, F.; Khorvash, F. Coexistence of Multiple Sclerosis and Brain Tumor: An Uncommon Diagnostic Challenge. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myserlis, P.; Stachteas, P.; Dimitriadis, I.; Tsolaki, M. Development of Glioblastoma Multiforme in a Patient with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Austin J. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 4, 1128. [Google Scholar]

- Preziosa, P.; Sangalli, F.; Esposito, F.; Moiola, L.; Martinelli, V.; Falini, A.; Comi, G.; Filippi, M. Clinical Deterioration Due to Co-Occurrence of Multiple Sclerosis and Glioblastoma: Report of Two Cases. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 38, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirani, A.; Wu, G.; Giannini, C.; Cross, A. A Case of Oligodendroglioma and Multiple Sclerosis: Occam’S Razor or Hickam’S Dictum? BMJ Case Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, G.; Al-saffar, Y.; Johnstone, P.; Hatiboglu, M.; Shamikh, A. A Challenging Case of Concurrent Multiple Sclerosis and Anaplastic Astrocytoma. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2019, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirko, A.; Dzyak, L.; Chekha, E.; Malysheva, T.; Romanukha, D. Coexistence of Multiple Sclerosis and Brain Tumours: Case Report and Review. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2020, 19, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, H.; Shirah, B.; Tashkandi, M.; Samkari, A. Concurrence of Multiple Sclerosis, Oligodendroglioma, and Autosomal Recessive Cerebellar Ataxia with Spasticity in The Same Patient: A Challenging Diagnosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 40, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, F.; Cambron, B.; Jacobs, S.; Delrée, P.; Gustin, T. Glioblastoma in a Fingolimod-Treated Multiple Sclerosis Patient: Causal or Coincidental Association? Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 41, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, H.; Jain, K.; Agarwal, A.; Singh, M.; Yadav, S.; Husain, M.; Krishnani, N.; Gupta, R. Characterization of Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions Using MR Imaging and In-Vivo Proton MR Spectroscopy. Mult. Scler. J. 2008, 15, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boviatsis, E.; Kouyialis, A.; Stranjalis, G.; Korfias, S.; Sakas, D. CT-Guided Stereotactic Biopsies of Brain Stem Lesions: Personal Experience and Literature Review. Neurol. Sci. 2003, 24, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, J.; Giannini, C.; Eckel-Passow, J.; Lachance, D.; Parney, I.; Laack, N.; Jenkins, R. Management of Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults—Use of Molecular Diagnostics. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, D.; Lucchinetti, C.; Calabresi, P. Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchinetti, C.; Gavrilova, R.; Metz, I.; Parisi, J.; Scheithauer, B.; Weigand, S.; Thomsen, K.; Mandrekar, J.; Altintas, A.; Erickson, B.; et al. Clinical and Radiographic Spectrum of Pathologically Confirmed Tumefactive Multiple Sclerosis. Brain 2008, 131, 1759–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brain Tumor-Risk Factors. Available online: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/brain-tumor/risk-factors (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Brownlee, W.; Hardy, T.; Fazekas, F.; Miller, D. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: Progress and Challenges. Lancet 2017, 389, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain Tumor-Symptoms and Causes. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/brain-tumor/symptoms-causes/syc-20350084 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- What Distinguishes MS from Its Mimics? Available online: https://www.mdedge.com/multiplesclerosishub/article/113987/multiple-sclerosis/what-distinguishes-ms-its-mimics (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Hardy, T.; Chataway, J. Tumefactive Demyelination: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 84, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantone, D.; Renna, R.; Sbardella, E.; Koudriavtseva, T. Concurrence of Multiple Sclerosis and Brain Tumors. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Preziosa, P.; Banwell, B.; Barkhof, F.; Ciccarelli, O.; Stefano, N. Assessment of Lesions On Magnetic Resonance Imaging In Multiple Sclerosis: Practical Guidelines. Brain 2019, 142, 1858–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajja, B.; Wolinsky, J.; Narayana, P. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy In Multiple Sclerosis. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2009, 19, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriyama, T.; Kataoka, H.; Taoka, T.; Tonomura, Y.; Terashima, M.; Morikawa, M.; Tanizawa, E.; Kawahara, M.; Furiya, Y.; Sugie, K.; et al. Characteristic Neuroimaging in Patients with Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions Exceeding 30 Mm. J. Neuroimaging 2011, 21, e69–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, H.; Shirah, B.; Alassiri, A. Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions: A Comprehensive Review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2017, 14, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).