Abstract

Danon Disease (DD) is a rare X-linked autophagic vacuolar myopathy caused by pathogenic variants in the lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP-2) gene. Alternative splicing of the terminal exon 9 leads to the creation of three different isoforms, each with essential roles in regulating autophagy. DD is characterized by cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, cognitive impairment, and retinal disorders, with cardiac involvement being the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Muscle biopsy may reveal signs of vacuolar myopathy, but the diagnosis is typically confirmed through sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of the LAMP-2 gene using peripheral blood. Although few genotype–phenotype correlations have been described, with most being limited to isoform 2B of exon 9, the most significant prognostic indicator remains sex. The disease manifests earlier and with a more severe systemic presentation in males due to their hemizygous status, whereas in females, the typical presentation is late-onset hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, generally without extracardiac involvement. Cases of severely affected women have been described, potentially due to non-random or defective X-inactivation. The less typical and delayed clinical presentation in females can result in incorrect or missed diagnoses. The aim of this narrative review is to summarize the natural history, diagnostic criteria, management strategies, and recent advancements in the understanding of DD in women.

1. Introduction

Danon disease (DD) is a rare X-linked dominant disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP-2) gene [1]. The protein encoded by LAMP-2 plays a crucial role in regulating autophagic processes in multiple tissues and organs [2]. The exact prevalence of DD remains unknown; it is estimated to affect fewer than 1 in 1,000,000 individuals in the general population [3]. Among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the prevalence may reach 1–4% [4,5]. The true prevalence of DD in the female population is unknown and likely underestimated, as reflected in the relative scarcity of cases reported in the literature. As an X-linked disorder, DD typically manifests earlier and with a more severe phenotype in males compared with females [6]. In contrast, females frequently present with a broader clinical spectrum, often with delayed onset and less consistent extracardiac involvement (Graphical Abstract). This phenotypic variability, together with the frequent paucity of systemic manifestations, contributes to diagnostic under-recognition in women. The aim of this narrative review is to summarize the natural history, diagnostic criteria, management strategies, and recent advancements in the understanding of DD in women.

2. Pathophysiology and Molecular Genetics

2.1. The LAMP Family

The LAMP family was first identified in the late 1970s and early 1980s during studies on lysosomal membrane composition, when heavily glycosylated proteins were isolated as major structural components of the organelle. The first members described were LAMP-1 and LAMP-2, followed by LAMP-3 (DC-LAMP) and LAMP-5 (BAD-LAMP), which expanded the family and highlighted their specialized roles across tissues and immune cell subsets [7].

These transmembrane proteins are among the most abundant components of the lysosomal membrane and are characterized by extensive glycosylation. Their heavy glycan coating provides protection from lysosomal hydrolases, while their short cytoplasmic tails mediate interactions with trafficking and signaling molecules. Functionally, LAMP proteins are critical for maintaining lysosomal integrity and autophagic flux, as well as for antigen presentation and overall cellular homeostasis [7,8]. Dysregulation or pathogenic variants of LAMP genes have been implicated in a wide spectrum of diseases, including lysosomal storage disorders, neurodegenerative conditions, immune dysregulation, and tumor progression. Given their central role in cellular metabolism and stress responses, LAMP family proteins are increasingly recognized as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 together constitute approximately 50% of all lysosomal membrane proteins. In vivo studies have demonstrated that mice lacking either LAMP-1 or LAMP-2 can survive into adulthood and remain fertile, whereas the combined knockout of both genes results in embryonic lethality [7]. Mice deficient in LAMP-1 exhibit relatively mild phenotypes with vacuolar accumulation, while LAMP-2 knockout mice develop a more severe phenotype resembling that observed in human Danon disease [8].

Lysosomal dysfunction impairs the cell’s ability to degrade metabolic substrates, leading to their progressive accumulation. This pathological process disrupts cellular physiology through two main mechanisms: (1) the accumulation of glycogen-filled vacuoles contributes to hypertrophy of muscle fibers; and (2) impaired metabolic activity generates an imbalance between energy demand and supply, promoting oxidative stress, cell death, and subsequent replacement fibrosis [9].

2.2. LAMP-2 Pathophysiology

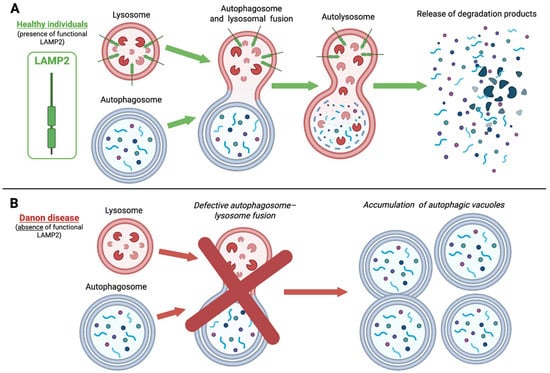

LAMP-2 coats the inner surface of the lysosomal membrane and plays a pivotal role in the cellular recycling process of macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy [10]. Specifically, it mediates the fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes, enabling the delivery of cellular waste to the lysosome for degradation (Figure 1). In addition, LAMP-2 functions as a receptor in chaperone-mediated autophagy, facilitating the translocation of cytosolic proteins into lysosomes for degradation. Danon disease was initially classified as a glycogen storage disorder based on pathological findings; however, LAMP-2 itself lacks enzymatic activity and does not directly regulate glycogen metabolism [7].

Figure 1.

Impaired macroautophagy in Danon Disease due to LAMP2 deficiency. In healthy individuals (A), autophagosomes efficiently fuse with lysosomes-forming autolysosomes-to degrade intracellular components. LAMP2 is essential for normal lysosomal function. In Danon disease (B), the absence of functional LAMP2 impairs this fusion process, leading to defective autophagic clearance and the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, mainly in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. LAMP2, lysosome-associated membrane protein 2. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

The LAMP-2 gene is located on the long arm of the X chromosome (region Xq24), spans nine exons, and encodes a 410-amino-acid protein of 1233 nucleotides. Alternative splicing of exon 9 generates three isoforms—LAMP-2A, LAMP-2B, and LAMP-2C—that differ in their transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, while sharing identical luminal domains. Isoforms 2A and 2C are ubiquitously expressed, whereas LAMP-2B is predominantly expressed in the heart, skeletal muscle, and brain [8]. This tissue-specific expression pattern is consistent with the clinical triad of DD, characterized by cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, and cognitive impairment.

Although the precise disease mechanisms are incompletely understood, studies in animal models and induced pluripotent stem cells derived from affected patients suggest that loss of LAMP-2, particularly LAMP-2B, disrupts macroautophagy and leads to lysosomal dysfunction [11,12,13].

Genetic variations include nonsense and frameshift variants, splice site alterations, and large deletions, most of which lead to complete loss of LAMP-2 protein production [14]. Microdeletions and microduplications have also been described [15,16]. These alterations impair both macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy, resulting in the characteristic accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, mainly in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells [10] (Figure 1).

To date, 129 variants have been classified in ClinVar as Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic (class 4 or 5 according to the American College of Medical Genetics, ACMG), predominantly frameshift, nonsense or splice site variants. Over one-third of cases are caused by de novo genetic changes [17,18,19].

Additionally, 274 variants, mainly missense or small insertions/deletions, are reported as Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS, ACMG class 3) [17].

Although disease penetrance is thought to approach 100% in both sexes, the hemizygous state in males results in earlier onset and more uniform clinical expression, whereas heterozygous females present with delayed and heterogeneous manifestations [17]. This variability is largely attributable to the extent and pattern of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) in somatic cells and the resulting mosaicism of LAMP-2 expression [17,19,20,21,22].

3. Natural History and Clinical Features

3.1. Cardiac Manifestations

Danon disease typically presents with a triad of cardiomyopathy, skeletal muscle weakness, and cognitive impairment, consistent with LAMP-2 distribution [17,18]. Among these features, cardiac involvement is generally the most prominent and clinically significant, whereas skeletal muscle and neurological manifestations exhibit considerable variability in onset and severity [9,17]. Additional systemic manifestations may include retinopathy, gastrointestinal disturbances, and hepatic dysfunction [17,19].

In female patients, the onset of symptoms and major clinical events occurs, on average, approximately 15 years later than in males. Disease expression in women is less predictable, with cardiac manifestations still representing the predominant features, while extracardiac involvement is more variable and often milder. Cardiac manifestations in females typically appear during adolescence or adulthood and progress more gradually compared to males [19,23]. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Main features of Danon Disease and sex-related differences.

While male patients with DD typically develop severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy progressing to end-stage heart failure during the second or third decade of life, females may present with either hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy. In women, disease progression is generally slower, with end-stage heart failure occurring approximately a decade or more later than in males [6,9,17,24]. A recent systematic review reported a possible bimodal incidence pattern of heart failure (HF) in females, with peaks around 17 and 35 years of age [6,25]. Disease onset during infancy is rare and predominantly observed in males due to hemizygosity, although early-onset cases in females have been reported [21,26].

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) remains the most common initial cardiac manifestation in both sexes; however, 30–50% of female patients present with a dilated or hypokinetic nondilated cardiomyopathy phenotype [6,9]. Progressive cardiac involvement in DD leads to chronic myocardial injury, often reflected by persistently elevated circulating troponin levels [6,9]. Over time, the hypertrophic myocardium may become hypokinetic with wall thinning and potential chamber dilation, a process driven by cardiomyocyte death and replacement fibrosis [18]. It remains unclear whether dilated cardiomyopathy in females represents a progression from initial hypertrophy or constitutes an independent disease phenotype [9,27].

In a systematic review by Brambatti et al., which included 146 genetically confirmed DD patients, 38.4% were female (56/146). Clinical manifestations occurred significantly later in females than males [6].

In female patients, the clinical phenotype was predominantly characterized by isolated cardiac involvement, reported in approximately 73% of cases. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was typically diagnosed at a median age of 16 years, with progression to end-stage cardiomyopathy occurring at a median age of 28 years [6]. Although the onset in females is generally later compared to males, the incidence of severe outcomes—including death, heart transplantation (HTx), or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation—did not differ significantly between sexes (36.7% in males vs. 32.1% in females). Nevertheless, such events occurred at a significantly older age in females (median 38 years) than in males (median 21 years; p < 0.001) [6]. Of note, medical therapy was not systematically assessed in the review.

Conversely, in an international registry including 38 patients with Danon disease (DD) who underwent HTx (19 females), Hong et al. reported comparable ages at transplantation between sexes, with a median of 20.2 years across the cohort [28]. Post-transplant outcomes were overall favorable and did not differ significantly between males and females. Interestingly, females required higher doses of prednisone for a longer duration in the post-transplant setting. The authors hypothesized that this could be explained by either (i) the use of a pre-transplant “steroid-sparing regimen” in males to mitigate the risk of myopathy—observed in four male patients but absent in females—or (ii) the higher incidence of acute cellular rejection in females (6 vs. 1 case).

Electrophysiological abnormalities and arrhythmias represent common features of DD in both sexes. Early findings include a short PR interval and the presence of delta waves on surface ECG [17]. Pre-excitation, in the context of Wolf–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome or fasciculoventricular pathways, may represent an early phenotypic expression of the disease. Supraventricular tachycardias, such as atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation, are frequently observed in both males and females. Ventricular arrhythmias are also common [17,23]. These findings are more frequently detected in DD than in other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenocopies [9,19,29]. Although Boucek et al. previously reported WPW syndrome as more prevalent in males (68% vs. 27% in females), a systematic review by Brambatti et al. indicated no statistically significant sex-related differences (48% in males vs. 32% in females; p = 0.084) [6,24]. Similarly, the prevalence of arrhythmias and use of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) did not differ significantly between sexes. Ventricular arrhythmias were reported in 10% of patients overall (10% in males and 3.6% in females) [6]. Importantly, cardiac arrest or sudden arrhythmic death may represent the first clinical manifestation in both males and females [9].

3.2. Extracardiac Manifestations

Although cardiac involvement represents the predominant feature of DD, systemic manifestations also contribute significantly to the clinical spectrum. In female patients, however, extracardiac features occur less frequently and are typically milder compared with males [9,23].

Skeletal myopathy is reported in approximately 51% of patients with Danon disease, with a clear male predominance and preferential involvement of proximal muscle groups [6]. In females, skeletal muscle manifestations are generally mild, consisting of proximal muscle weakness, exercise intolerance, and modest elevations in serum creatine kinase (CK) and transaminases [5,6,13].

Ischemic thromboembolic strokes have been reported in several female patients frequently secondary to intracardiac thrombi in the setting of impaired left ventricular function or atrial fibrillation [6,23,30].

Neurocognitive involvement is also sex-dependent. While at least 80% of affected males present with cognitive impairment or learning difficulties, the reported prevalence in females ranges between 6% and 47% [6,31]. When present, cognitive deficits are generally mild. Psychiatric comorbidities—including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and mood disorders—are more common and severe in males, although they may also occur in female patients [17,31]. A study involving 82 individuals with DD from 36 families reported that mild to moderate learning or cognitive disabilities were present in all affected males and approximately half of affected females [24]. More recently, one study systematically assessed the cognitive and psychiatric characteristics of thirteen participants (five males and eight females) with genetically confirmed LAMP2 mutations characterizing DD [31]. The study confirmed that, when cognitive abilities are evaluated using standardized neuropsychological assessments, most individuals with DD do not exhibit intellectual disability but rather milder cognitive deficits, particularly affecting executive functioning. Moreover, this investigation reported a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, especially anxiety and mood disorders, in both male and female participants: more than two-thirds of the individuals met diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder, and approximately half had two or more comorbid psychiatric conditions. These findings suggest that patients with DD are predisposed to developing depressive and anxiety disorders. Overall, cognitive impairment and psychiatric comorbidities may significantly worsen quality of life in Danon disease, adversely influencing the social, emotional, and functional well-being of both male and female patients. Therefore, within a multidisciplinary framework, both psychiatric and neurological assessments should be recommended for all individuals newly diagnosed with LAMP2 mutations [31].

Ophthalmologic abnormalities, such as pigmentary retinopathy and myopia, have been classically associated with DD. These findings are more frequent in males, but have also been observed in female patients [6,19,32].

These visual deficits are frequently subclinical and may only be detected through specialized ophthalmologic testing [33]. The underlying mechanisms are thought to involve loss of retinal pigment within the retinal epithelium and cone–rod dystrophy [25,34,35]. A recent study provided comprehensive ocular phenotyping in a cohort of patients with Danon disease (10 affected individuals: 3 males and 7 females, plus one asymptomatic female somatic mosaic carrier of a LAMP2 disease-causing variant), underscoring the value of detailed ophthalmologic examination and advanced imaging for identifying LAMP2 variant carriers, including those with very low levels of somatic mosaicism [35]. The findings provide a strong rationale for molecular, genetic, and/or functional investigation in individuals presenting with pigmentary retinopathy, as this feature may represent the sole manifestation of a potentially life-threatening condition such as DD. High-resolution imaging techniques, including spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and fundus autofluorescence, should be regarded as integral components of the multidisciplinary diagnostic approach in families with DD. In this context, detailed ocular examination may serve as a sensitive and rapid screening tool for detecting LAMP2 pathogenic variant carriers, even in cases of somatic mosaicism. Therefore, comprehensive assessment is warranted in all patients with pigmentary retinal dystrophy, given its possible association with a severe underlying genetic disorder [35].

Additional systemic features, including mild hepatomegaly, have occasionally been reported but usually do not represent a major clinical burden in females [17].

The considerable heterogeneity in disease expression among women—likely reflecting variable patterns of X-chromosome inactivation—combined with the generally milder and less frequent extracardiac features, makes the diagnosis of DD in females particularly challenging. In many cases, the condition is identified incidentally during genetic testing for cardiomyopathy (e.g., targeted gene panels or whole-exome sequencing) [17].

4. Diagnosis

4.1. Diagnostic Criteria

Clinical suspicion of Danon disease should be raised in the presence of suggestive family history, characteristic clinical presentation, and supportive imaging findings. The identification of a pathogenic LAMP-2 variants currently represents the cornerstone for diagnosis [17]. This is particularly relevant in female patients, in whom the frequent absence of extracardiac features and the cardiac imaging findings may mimic other forms of cardiomyopathy. When genetic testing is unavailable or yields inconclusive results, skeletal muscle or endomyocardial biopsy may resolve diagnostic uncertainty.

According to the 2023 International Consensus on Differential Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Danon Disease [17], the diagnostic algorithm for female patients is based on the detection of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic LAMP-2 variants in association with at least one objective cardiac manifestation defined as follows:

- LVH, defined as septal or posterior wall thickness ≥ 1.3 cm in adults (≥18 years) or z-score ≥2 in children/adolescents (<18 years);

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%;

- Presence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR);

- Basal ECG alterations, including pre-excitation, repolarization abnormalities, left or right ventricular hypertrophy;

- A positive history of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, atrioventricular block, or sudden cardiac death.

In patients with a LAMP-2 variant of unknown significance, ribonucleic acid (RNA) analysis to evaluate LAMP-2 protein functional deficiency, as determined by either leukocyte flow cytometry or tissue analysis, is required for diagnosis [17].

4.2. Electrocardiography

As in male patients, the ECG of female patients with DD may demonstrate a Wolf–Parkinson–White pattern, characterized by a short PR and a δ wave, in approximately 40% of cases [18].

4.3. Imaging

Transthoracic echocardiography often provides the first indication of cardiomyopathy, typically showing left ventricular hypertrophy. Global left ventricular function may be reduced, along with left ventricular longitudinal strain values with a base-to-apex gradient. Bui et al. also reported an apical sparing pattern resembling that observed in cardiac amyloidosis [36].

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is a key non-invasive imaging tool in patients with DD, providing a comprehensive, multiparametric assessment of cardiac structure and function. Its high spatial resolution enables a detailed myocardial tissue characterization. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) identification, myocardial T2 and T1 mapping, and extracellular volume (ECV) quantification are sensitive techniques for detecting myocardial fibrosis and edema.

The three most relevant case series indicate that male patients with DD usually present with symmetric LVH, either isolated or associated with left ventricular dilatation. In contrast, females more frequently display asymmetric LVH, often combined with right ventricular hypertrophy [37,38,39].

As already stated, female patients with DD may present with either hypertrophic and/or dilated phenotypes [37]. While left ventricle (LV) dilatation in women is frequently interpreted as a late-stage manifestation of LVH, it remains unclear whether it may represent a distinct phenotype.

Previous reports have shown a variable degree of left ventricular dysfunction in females with DD. Wei et al. [39] reported data on 3 women with a mean LVEF of 65%, while Rigolli et al. [37] published data on 7 women with a mean LVEF of 49%, similar to Brambatti et al. [6], while Lotan et al. [18] reported a severely reduced LVEF of 28%. This variability likely reflects differences in disease stage at diagnosis and phenotypic heterogeneity, highlighting the need for larger studies to better characterize the subset of female patients.

Extensive LGE is a consistent hallmark of DD, typically involving the LV free wall with a subendocardial distribution and relative sparing of the mid-basal interventricular septum [37,38]. However, the prevalence of this pattern among female patients varies considerably, from 33% [37] to 100% [40].

Myocardial T1 mapping is used to assess myocardial interstitial space, especially myocardial fibrosis. In the early stages of the disease, T1 values may be reduced due to intracellular glycogen storage, whereas later stages are associated with increased T1 values, reflecting microscopic extracellular fibrosis, as demonstrated in CMR case series [38,39]. T2 mapping, a marker of edema and disease activity, has been reported to be elevated in the LV free wall of affected patients [39]. However, sex-specific data on myocardial mapping parameters in women are currently lacking.

4.4. Skeletal Muscle or Endomyocardial Biopsy

Skeletal myopathy is substantially less common in females compared with males (76% vs. 13%) [6]. Biopsy of skeletal muscle or myocardium is usually reserved for cases in which a LAMP-2 variant of uncertain significance is identified and diagnostic uncertainty persists. Histopathological examination typically reveals muscle fibers containing autophagic vacuoles with abnormal structures and glycogen granules scattered among fascicles [7]. Immunohistochemistry and Western blot consistently demonstrate complete absence of LAMP-2 protein in skeletal and cardiac tissues, regardless of the genetic change. Importantly, since the predominant phenotype in females consists of isolated cardiomyopathy, a normal skeletal muscle biopsy does not exclude a LAMP-2-related cardiomyopathy.

4.5. Laboratory and Genetic Testing

In female patients with DD, elevated troponin and NT-proBNP levels may reflect cardiac involvement. In contrast, laboratory markers of skeletal muscle damage—such as creatine kinase (CK), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)—are altered in only ~16% of women [6], consistent with their limited extracardiac involvement.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the LAMP-2 gene, performed as single-gene analysis, within cardiomyopathy panels, or through whole-exome sequencing, enables diagnosis in approximately 95% of cases. Rare deletions or duplications involving several exons or the entire gene have also been reported, and LAMP-2 deletions may occur within larger Xq24 microdeletion syndromes. Accordingly, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or targeted microarray should be considered to detect the remaining ~5% of cases [41].

Alterations spanning exons 1–8 affect all three LAMP-2 isoforms. Most splice site variants are located in intron 6, while many other variants are private and have been reported only within single families [42].

In cases where only one male in the family is affected, the pathogenic variant may be inherited from a heterozygous mother or may arise de novo. In one study, de novo variants accounted for ~40% of cases [22].

5. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

In Danon disease (DD), prognosis is closely linked to the severity of clinical presentation. This relationship is particularly relevant in female patients, given that genotype–phenotype correlations remain limited and inconsistently defined. Mutations affecting all LAMP2 isoforms, especially those resulting in complete loss of LAMP-2B, are associated with more severe cardiac phenotypes, including early-onset hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy and rapid progression to heart failure. Conversely, few pathogenic variants confined to exon 9B of the LAMP-2B isoform have been associated with milder or atypical clinical phenotypes [9,42,43,44,45,46]

No defined mutational hotspots have been identified, and except for exon 9B, there is no evidence that the location of the variant, such as its position within specific functional domains, correlates with disease severity.

One study analyzed the impact of the type of variant on clinical outcome [42]. For example, bradyarrhythmias requiring pacemaker implantation were observed in 6%, 12%, and 26% of patients with truncating, missense, or splicing variants, respectively. Missense variants were associated with a lower incidence of cardiomyopathy, whereas truncating variants were linked to the earliest symptom onset. In contrast, splicing variants were typically associated with a later disease onset, while missense variants conferred the latest onset overall, with symptom manifestation reported as late as 32 years. These associations appear to apply to both male and female patients.

5.1. Role of X-Chromosome Inactivation (XCI) in Females

In heterozygous females, X-chromosome inactivation is considered a key determinant of clinical variability and prognosis. In cases of random XCI, partial restoration of LAMP-2 expression occurs in skeletal muscle fibers due to nuclear domain overlap, but not in cardiomyocytes, which lack regenerative capacity. This may explain the frequent development of cardiomyopathy without significant skeletal myopathy in female patients [17,19].

A random distribution of XCI has been documented across tissues from different patients [20]. When XCI is skewed toward the mutant allele, most cardiomyocytes lack LAMP-2 expression, leading to earlier onset and more severe cardiomyopathy [19,20,21]. Furthermore, even moderate global reductions in LAMP-2 protein may be clinically significant if XCI is unevenly distributed across myocardial regions [21]. Finally, both somatic and germline mosaicism are likely additional, and often underestimated, contributors to phenotypic variability in females [19,22].

Several studies have evaluated XCI patterns in different tissues. Bottillo et al. [42] performed methylation analysis on DNA from blood leukocytes and cardiac tissue (ventricular and septal samples) of a female patient undergoing heart transplantation, alongside paternal DNA to determine X-chromosome inheritance. The XCI pattern was assessed by cytosine methylation of CpG dinucleotides within the polymorphic Cytosine, Adenine and Guanine (CAG) repeat in the first exon of the androgen receptor (AR) gene, located on the X chromosome. In this patient, the maternally inherited X chromosome carrying the c.453delT LAMP-2 variant showed 62% inactivation in leukocytes, whereas the paternally inherited (wild-type) allele was preferentially inactivated in the left ventricle (56%) and septum (61%). A broader analysis [45] reviewed 13 published DD cases (up to January 2021) with documented XCI status, including the case by Bottillo et al. Results demonstrated marked tissue variability: XCI patterns in urine, hair follicles, buccal swabs, and leukocytes did not reliably reflect those in clinically relevant tissues (heart, skeletal muscle). The study concluded that XCI status in leukocytes—the most accessible tissue in clinical practice—cannot be used as a prognostic marker in DD. Instead, the XCI pattern is highly tissue-specific, which complicates prediction of cardiac disease severity in women with LAMP-2 variants, given the inaccessibility of myocardial tissue for analysis.

Finally, the majority of X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder genes are also subject to XCI [46], leading to phenotypic variability between males and females. Notably, the LAMP-2 gene is included among those that could escape XCI, in line with its X-linked dominant inheritance; for these so-called “escapees”, the neurodevelopmental phenotype tends to be very severe in males and generally milder in symptomatic females [46].

5.2. Additional Genetic and Epigenetic Modifiers

The role of genetic and epigenetic modifiers in determining penetrance and expressivity of monogenic diseases is a “hot topic” in medical genetics. As for DD, there are no specific genetic modifiers yet, but, theoretically, the presence of variants on the other allele of LAMP2 or in other genes involved in autophagy, in lysosomal or mitochondrial function may influence disease expression and severity.

As demonstrated by the X-inactivation phenomenon, methylation and other epigenetic processes can also influence the severity of the disease. Reactivation of the wild-type allele via DNA methylation inhibitors has been shown in patient-derived iPSC models to ameliorate autophagic dysfunction, this may pave the way to future therapeutic approaches [47].

5.3. Influence of Age on Disease Progression

The impact of aging must also be considered. Heterozygous females with skewed XCI often exhibit reduced levels of functional LAMP-2 protein. Over time, this deficiency contributes to progressive myocardial injury [23]. It has been hypothesized that in early life, compensatory mechanisms can partially offset impaired autophagic flux. However, with aging, the gradual accumulation of autophagic vacuoles exceeds cellular compensatory capacity, leading to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, apoptosis, and ultimately cardiomyopathy [48].

5.4. Other Potential Modifiers

Beyond XCI, additional factors may influence phenotype severity in females. Notably, microvascular dysfunction has been proposed as a contributor to cardiac pathology, through mechanisms similar to those described in sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [49].

6. Therapies

At present, there is no disease-specific treatment for Danon disease. According to the most recent international consensus [17], a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, involving cardiologists, neurologists, ophthalmologists, and rehabilitation specialists, in order to address organ-specific manifestations and provide symptom-directed care. From a cardiological perspective, clinical management should primarily focus on heart failure symptoms and progression and ventricular arrhythmias prevention.

6.1. Heart Failure Management

Heart failure in DD may manifest as both heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Although DD patients have not been specifically represented in randomized HF trials, current guidelines recommend applying standard guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) as outlined by the ESC [50] and AHA/ACC [51].

As previously discussed, female patients more frequently present with a dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype compared with males [6], relatively making HFrEF more prevalent among women. Despite optimized medical therapy, many patients progress to advanced HF, requiring mechanical circulatory support (e.g., LVAD) and/or HTx. Current position papers suggest that heart transplant should be considered in patients with severe heart failure symptoms refractory to medical therapy and/or intractable arrhythmias [17,52]. However, systematic data on medical management and outcomes in this population remain limited, underscoring the need for disease-specific studies.

6.2. Arrhythmias

DD patients frequently develop both bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias. Reported rates of arrhythmias and cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) use appear similar in males and females [6]. Common findings include atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrioventricular accessory pathways [53,54].

According to consensus recommendations, catheter ablation should be considered in symptomatic patients whose arrhythmic burden is not adequately controlled with pharmacotherapy [52]. Beta-blockers are generally the first-line therapy for atrial tachyarrhythmias and orthodromic AV reentrant tachycardia, with the added benefit of contributing to HF management [9].

In patients presenting with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, specific scores have been validated to estimate the 5-years risk of sudden cardiac death due to ventricular arrhythmias, for both the adult [55] and pediatric populations [56,57]. None of the cohorts used for validation had a representative DD patient population; therefore, these scores are not directly applicable in this subset of patients.

The Italian Society of Cardiology has proposed considering a lower threshold for ICD implantation in DD patients compared with those with sarcomeric HCM [52]. Specifically, ICD placement should be considered in individuals with severe LV hypertrophy, non-sustained VT, or unexplained syncope. Nevertheless, data on long-term outcomes following this approach are lacking, and no specific recommendations exist for risk stratification in female patients with DD.

6.3. Screening and Follow-Up

Genetic screening is increasingly employed in clinical practice to confirm the diagnosis in probands with suspected DD. Current ESC guidelines on cardiomyopathies [58] recommend that first-degree relatives of carriers of pathogenic or likely pathogenic LAMP-2 variants undergo genetic testing, to enable early identification and management of genotype-positive, phenotype-negative individuals.

Sex-specific surveillance strategies are advised due to differences in age of disease onset. The ACC consensus [17] recommends initiating surveillance at 6 years of age for females and from the first year of life for males. Standard cardiological follow-up should include a comprehensive physical examination, 12-lead ECG and transthoracic echocardiography, which together provide adequate sensitivity to detect early disease manifestations [17]. Cardiac MRI should be considered in cases where echocardiographic findings are inconclusive or when earlier or more detailed characterization of the disease is required.

6.4. Socioeconomic Aspects

Although no dedicated studies have assessed the socioeconomic burden of DD, indirect evidence from other cardiomyopathies and rare X-linked, lysosomal, or metabolic disorders indicates that affected individuals and their families face significant challenges related to the costs of diagnosis and treatment, reduced work capacity, and decreased quality of life [59,60]. The progressive course of cardiac and skeletal myopathy often entails a high degree of dependency and emotional strain for caregivers. Furthermore, access to specialized multidisciplinary care remains uneven across regions. More studies are needed to examine this complex and delicate aspect of Danon Disease.

7. Future Perspectives

7.1. Biomarkers and Artificial Intelligence

Future advances in Danon disease are expected to rely on more precise and non-invasive biomarkers, coupled with the expanding contribution of artificial intelligence (AI).

Reliable markers capable of reflecting disease onset and progression—particularly in asymptomatic young females, who often present a milder and highly variable phenotype—remain a crucial unmet need [61]. Direct assessment of autophagic dysfunction is informative but invasive, thus encouraging research on surrogate circulating biomarkers, including disease-related miRNA signatures. These molecules are stable in plasma and may capture both cardiac and skeletal muscle involvement; however, specific miRNA patterns for Danon disease have yet to be defined, and potential sex-related differences remain to be clarified [62]. Another promising candidate, by analogy with Pompe disease, is the urinary glucose tetrasaccharide (Glc4), which has been reported markedly elevated in at least one Danon patient, suggesting it may reflect altered muscle glycogen metabolism and deserve further validation [63].

Parallel to biomarker discovery, rapid progress in AI-based technologies offers opportunities to improve early detection, risk stratification, and individualized management. Machine learning tools have already shown their ability to identify subtle features of left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG and to detect characteristic cardiomyopathy patterns on echocardiography and CMR [64,65,66]. The integration of AI with next-generation sequencing and multi-omics pipelines is expected to enhance recognition of genotype–phenotype correlations and uncover sex-specific molecular drivers, particularly relevant in female carriers [67,68]. Ultimately, the convergence of advanced bioinformatics, digital pathology, and automated imaging analysis may lead to more accurate and less invasive diagnostic pathways, supporting earlier intervention and tailored follow-up strategies in affected females [67].

7.2. Therapy

Given that DD results from loss-of-function variants in the LAMP-2 gene, gene replacement strategies represent the most promising therapeutic avenue. A recent phase 1 clinical trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of an AAV9-based vector carrying LAMP-2B in seven male patients [10,69]. At baseline, endomyocardial biopsy demonstrated absent LAMP-2B expression. At six months, six of the seven patients exhibited cardiac LAMP-2B expression, with improved myocardial structure documented in five cases. One patient underwent HTx during follow-up due to disease progression.

Although these preliminary findings are encouraging, the trial included only male participants. Consequently, data on gene therapy efficacy and safety in female patients with DD remain unavailable, and future studies are required to clarify potential sex-specific responses. In female patients, as already mentioned, future research may also focus on reactivating the wild-type allele through epigenetic modifications.

8. Limitations

This narrative review may not include all studies available on this complex clinical condition. Nevertheless, it aims to provide a comprehensive and balanced overview of the current state of knowledge. The available data on Danon disease in females are mainly derived from observational studies with small sample sizes; therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution and confirmed in larger cohorts. The existing studies and case reports are heterogeneous, reflecting the rarity of the condition and the variability of its clinical presentations. Furthermore, a more specific review on therapeutic approaches is not feasible, as no dedicated drug trials or targeted treatments have been conducted in this population. Furthermore, a more detailed review of therapeutic approaches is not feasible, as no dedicated drug trials or targeted treatments have been conducted in this population.

9. Conclusions

Danon disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder with a heterogeneous clinical presentation that is profoundly influenced by sex. In women, the disease typically presents later than in men and is mostly dominated by cardiac involvement, particularly dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmic complications, whereas extracardiac features tend to be milder and less frequent. The wide interindividual variability observed in females is largely attributable to differences in X-chromosome inactivation patterns, which complicates genotype–phenotype correlations and limits the prognostic value of genetic and epigenetic analyses performed on extracardiac tissues. Current management remains supportive, focusing on heart failure treatment, arrhythmia prevention, and timely referral for advanced therapies, although standardized risk stratification tools for women are lacking. Emerging approaches such as gene therapy are promising but have so far been tested only in male patients, leaving crucial questions about safety and efficacy in women unanswered. Overall, DD in female patients represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its variable clinical spectrum, unpredictable progression, and lack of disease-specific treatment strategies. Future efforts should focus on longitudinal, sex-stratified studies aimed at clarifying genotype–phenotype relationships, improving prognostic tools, and expanding access to innovative therapies. Only through such targeted research will it be possible to optimize the management and outcomes of this complex and still underrecognized disease in women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.T., F.B., A.B., E.A. and G.N. Methodology: L.T.T., F.B., A.B. and E.A. Validation: M.B., A.G. and F.R. Resources: A.G. and F.R. Writing—original draft preparation: L.T.T., F.B., A.B. and E.A. Writing—review and editing: L.T.T., F.B., A.B., E.A., F.L.G. and A.P. Visualization: F.B., L.T.T., A.B., E.A. and F.L.G. Supervision: A.P. and G.N. Project administration: L.T.T., F.B., A.B., E.A. and F.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics |

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| AFL | atrial flutter |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AR | androgen receptor |

| AST | aspartate transaminase |

| AV | atrioventricular |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CIED | cardiac implantable electronic device |

| CMR | cardiac magnetic resonance |

| DD | Danon Disease |

| DCM | Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| ECV | extracellular volume |

| ESC | Europea Society of Cardiology |

| GDMT | guideline-directed medical therapy |

| HCM | hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HF | heart failure |

| HFpEF | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HTx | heart transplantation |

| ICD | Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator |

| LAMP | lysosome-associated membrane protein |

| LAMP-1 | lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 |

| LAMP-2 | lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| LAMP-2A | isoform 2A of lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| LAMP-2B | isoform 2B of lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| LAMP-2C | isoform 2C of lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| LAMP-3 | lysosome-associated membrane protein 3 |

| LAMP-5 | lysosome-associated membrane protein 5 |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LGE | late gadolinium enhancement |

| LV | left ventricle |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVH | left ventricular hypertrophy |

| MLPA | multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| VF | ventricular fibrillation |

| VT | ventricular tachycardia |

| VUS | Variants of Uncertain Significance |

| WPW | Wolf–Parkinson–White |

| XCI | X-chromosome inactivation |

References

- Takahashi, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Takano, K.; Sudo, A.; Wada, T.; Goto, Y.-I.; Nishino, I.; Saitoh, S. Germline Mosaicism of a Novel Mutation in Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein-2 Deficiency (Danon Disease). Ann. Neurol. 2002, 52, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Guhde, G.; Suter, A.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; Hartmann, D.; Lüllmann-Rauch, R.; Janssen, P.M.L.; Blanz, J.; Von Figura, K.; Saftig, P. Accumulation of Autophagic Vacuoles and Cardiomyopathy LAMP-2-Deficient Mice. Nature 2000, 406, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanet: Danon Disease. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/34587 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Charron, P.; Villard, E.; Sébillon, P.; Laforêt, P.; Maisonobe, T.; Duboscq-Bidot, L.; Romero, N.; Drouin-Garraud, V.; Frébourg, T.; Richard, P.; et al. Danon’s Disease as a Cause of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Survey. Heart 2004, 90, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; McMahon, C.J.; Smith, L.R.; Bersola, J.; Adesina, A.M.; Breinholt, J.P.; Kearney, D.L.; Dreyer, W.J.; Denfield, S.W.; Price, J.F.; et al. Danon Disease as an Underrecognized Cause of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Children. Circulation 2005, 112, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambatti, M.; Caspi, O.; Maolo, A.; Koshi, E.; Greenberg, B.; Taylor, M.R.G.; Adler, E.D. Danon Disease: Gender Differences in Presentation and Outcomes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 286, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugie, K.; Nishino, I. History and Perspective of LAMP-2 Deficiency (Danon Disease). Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskelinen, E.L. Roles of LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 in Lysosome Biogenesis and Autophagy. Mol. Asp. Med. 2006, 27, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, R.S.; Levandowski, C.; Slavov, D.; Graw, S.L.; Allen, L.A.; Adler, E.; Mestroni, L.; Taylor, M.R.G. Danon Disease: Clinical Features, Evaluation, and Management. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2014, 7, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, E.M.; Spencer, M.J. Genetic Medicine for Danon Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.I.; Perry, C.N.; Bauer, M.; Han, S.; Clegg, S.D.; Ouyang, K.; Deacon, D.C.; Spinharney, M.; Panopoulos, A.D.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; et al. Brief Report: Oxidative Stress Mediates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in a Human Model of Danon Disease and Heart Failure. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.I.; Murphy, A.N.; Divakaruni, A.S.; Klos, M.L.; Nelson, B.C.; Gault, E.C.; Rowland, T.J.; Perry, C.N.; Gu, Y.; Dalton, N.D.; et al. Impaired Mitophagy Facilitates Mitochondrial Damage in Danon Disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 108, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Leonard, A.; Knight, W.E.; Beussman, K.M.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Londono, P.; Aune, E.; Trembley, M.A.; Small, E.M.; et al. LAMP-2B Regulates Human Cardiomyocyte Function by Mediating Autophagosome–Lysosome Fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, C.; Jarre, L.; Blasevich, F.; Dassi, P.; Mora, M. Danon Disease: A Novel LAMP2 Mutation Affecting the Pre-MRNA Splicing and Causing Aberrant Transcripts and Partial Protein Expression. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2008, 18, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatta, M.; Yang, Z.; Funke, B.H.; Cripe, L.H.; Vick, G.W.; Mancini-Dinardo, D.; Peña, L.S.; Kanter, R.J.; Wong, B.; Westerfield, B.H.; et al. LAMP2 Microdeletions in Patients with Danon Disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2010, 3, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lines, M.A.; Hewson, S.; Halliday, W.; Sabatini, P.J.B.; Stockley, T.; Dipchand, A.I.; Bowdin, S.; Siriwardena, K. Danon Disease Due to a Novel LAMP2 Microduplication. JIMD Rep. 2014, 14, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.N.; Eshraghian, E.A.; Arad, M.; Argirò, A.; Brambatti, M.; Bui, Q.; Caspi, O.; de Frutos, F.; Greenberg, B.; Ho, C.Y.; et al. International Consensus on Differential Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Danon Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 1628–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, D.; Salazar-Mendiguchía, J.; Mogensen, J.; Rathore, F.; Anastasakis, A.; Kaski, J.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Olivotto, I.; Charron, P.; Biagini, E.; et al. Clinical Profile of Cardiac Involvement in Danon Disease: A Multicenter European Registry. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, E003117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenacchi, G.; Papa, V.; Pegoraro, V.; Marozzo, R.; Fanin, M.; Angelini, C. Review: Danon Disease: Review of Natural History and Recent Advances. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020, 46, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanin, M.; Nascimbeni, A.C.; Fulizio, L.; Spinazzi, M.; Melacini, P.; Angelini, C. Generalized Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein-2 Defect Explains Multisystem Clinical Involvement and Allows Leukocyte Diagnostic Screening in Danon Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg Oldfors, C.; Máthé, G.; Thomson, K.; Tulinius, M.; Karason, K.; Östman-Smith, I.; Oldfors, A. Early Onset Cardiomyopathy in Females with Danon Disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2015, 25, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Zhao, Y.; Ke, H.P.; Liu, W.T.; Du, Z.F.; Zhang, X.N. Detection of Somatic and Germline Mosaicism for the LAMP2 Gene Mutation c.808dupG in a Chinese Family with Danon Disease. Gene 2012, 507, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Sainz, Á.; Salazar-Mendiguchía, J.; García-Álvarez, A.; Campuzano Larrea, O.; López-Garrido, M.Á.; García-Guereta, L.; Fuentes Cañamero, M.E.; Climent Payá, V.; Peña-Peña, M.L.; Zorio-Grima, E.; et al. Clinical Findings and Prognosis of Danon Disease. An Analysis of the Spanish Multicenter Danon Registry. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucek, D.; Jirikowic, J.; Taylor, M. Natural History of Danon Disease. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.N.; Eshraghian, E.; Khedro, T.; Argirò, A.; Attias, J.; Storm, G.; Tsotras, M.; Bloks, T.; Jackson, I.; Ahmad, E.; et al. An International Longitudinal Natural History Study of Patients with Danon Disease: Unique Cardiac Trajectories Identified Based on Sex and Heart Failure Outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, 38394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandaeva, L.; Sonicheva-Paterson, N.; McKenna, W.J.; Savostyanov, K.; Myasnikov, R.; Pushkov, A.; Zhanin, I.; Barskiy, V.; Zharova, O.; Silnova, I.; et al. Clinical Features of Pediatric Danon Disease and the Importance of Early Diagnosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 389, 131189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, F.; Jain, R.; Jan, M.F.; Sulemanjee, N.Z.; Menaria, P.; Kalvin, L.; Bush, M.; Jahangir, A.; Khandheria, B.K.; Tajik, A.J. Malignant Cardiac Phenotypic Expression of Danon Disease (LAMP2 Cardiomyopathy). Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 245, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.N.; Battikha, C.; John, S.; Lin, A.; Bui, Q.M.; Brambatti, M.; Storm, G.; Boynton, K.; Medina-Hernandez, D.; Garcia-Alvarez, A.; et al. Cardiac Transplantation in Danon Disease. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, S.; Herber, J.; Zahka, K.; Boyle, G.J.; Saarel, E.V.; Aziz, P.F. Arrhythmias and Fasciculoventricular Pathways in Patients with Danon Disease: A Single Center Experience. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2019, 30, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugie, K.; Komaki, H.; Eura, N.; Shiota, T.; Onoue, K.; Tsukaguchi, H.; Minami, N.; Ogawa, M.; Kiriyama, T.; Kataoka, H.; et al. A Nationwide Survey on Danon Disease in Japan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardeni, M.; Weisman, O.; Mandel, H.; Weinberger, R.; Quarta, G.; Salazar-Mendiguchía, J.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Lobato-Rodríguez, M.J.; Simon, L.F.; Dov, F.; et al. Psychiatric and Cognitive Characteristics of Individuals with Danon Disease (LAMP2 Gene Mutation). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2017, 173, 2461–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prall, F.R.; Drack, A.; Taylor, M.; Ku, L.; Olson, J.L.; Gregory, D.; Mestroni, L.; Mandava, N. Ophthalmic Manifestations of Danon Disease. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorderet, D.F.; Cottet, S.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Borruat, F.X.; Balmer, A.; Munier, F.L. Retinopathy in Danon Disease. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2007, 125, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, M.; Inoue, T.; Miyai, T.; Obata, R. Retinal Dystrophy Associated with Danon Disease and Pathogenic Mechanism Through LAMP2-Mutated Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 30, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousal, B.; Majer, F.; Vlaskova, H.; Dvorakova, L.; Piherova, L.; Meliska, M.; Langrova, H.; Palecek, T.; Kubanek, M.; Krebsova, A.; et al. Pigmentary Retinopathy Can Indicate the Presence of Pathogenic LAMP2 Variants Even in Somatic Mosaic Carriers with No Additional Signs of Danon Disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.M.; Hong, K.N.; Kraushaar, M.; Ma, G.S.; Brambatti, M.; Kahn, A.M.; Bougault, C.; Boynton, K.; Mestroni, L.; Taylor, M.R.G.; et al. Apical Sparing Strain Pattern in Danon Disease: Insights From a Global Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 2689–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolli, M.; Kahn, A.M.; Brambatti, M.; Contijoch, F.J.; Adler, E.D. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Danon Disease Cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, X. Clinical Manifestations and MRI Features of Danon Disease: A Case Series. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhao, L.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhong, X.; Ye, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, M.; et al. Cardiac Phenotype Characterization at MRI in Patients with Danon Disease: A Retrospective Multicenter Case Series. Radiology 2021, 299, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucifora, G.; Miani, D.; Piccoli, G.; Proclemer, A. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Danon Disease. Cardiology 2012, 121, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.R.; Adler, E.D. Danon Disease. Front. Lysosomal Storage Dis. (LSD) Treat. 2024, 7, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottillo, I.; Giordano, C.; Cerbelli, B.; D’Angelantonio, D.; Lipari, M.; Polidori, T.; Majore, S.; Bertini, E.; D’Amico, A.; Giannarelli, D.; et al. A Novel LAMP2 Mutation Associated with Severe Cardiac Hypertrophy and Microvascular Remodeling in a Female with Danon Disease: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2016, 25, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Kooi, A.J.; Van Langen, I.M.; Aronica, E.; Van Doorn, P.A.; Wokke, J.H.J.; Brusse, E.; Langerhorst, C.T.; Bergin, P.; Dekker, L.R.C.; Lekanne Dit Deprez, R.H.; et al. Extension of the Clinical Spectrum of Danon Disease. Neurology 2008, 70, 1358–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y. Danon Disease Caused by Two Novel Mutations of the LAMP2 Gene: Implications for Two Ends of the Clinical Spectrum. Clin. Neuropathol. 2012, 31, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivitskaya, L.; Vaikhanskaya, T.; Danilenko, N.; Liaudanski, A.; Davydenko, O.; Zhelev, N. New Deletion in LAMP2 Causing Familial Danon Disease. Effect of X-Chromosome Inactivation. Folia Med. 2022, 64, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.A.; Blesson, A.E.; Smith-Hicks, C.L. The Impact of X-Chromosome Inactivation on Phenotypic Expression of X-Linked Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.M.; Mok, P.Y.; Butler, A.W.; Ho, J.C.Y.; Choi, S.W.; Lee, Y.K.; Lai, W.H.; Au, K.W.; Lau, Y.M.; Wong, L.Y.; et al. Amelioration of X-Linked Related Autophagy Failure in Danon Disease with DNA Methylation Inhibitor. Circulation 2016, 134, 1373–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, M.; Zhang, P.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, D.; Wang, R.; et al. Identification and Functional Analysis of a Novel de Novo Missense Mutation Located in the Initiation Codon of LAMP2 Associated with Early Onset Female Danon Disease. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; D’Amati, G.; Basso, C.; Van Rossum, A.; Patten, M.; Emdin, M.; Pinto, Y.; Tomberli, B.; Camici, P.G.; Michels, M. Defining Phenotypes and Disease Progression in Sarcomeric Cardiomyopathies: Contemporary Role of Clinical Investigations. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 105, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Čelutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, E895–E1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongelli, G.; Adorisio, R.; Baggio, C.; Bauce, B.; Biagini, E.; Castelletti, S.; Favilli, S.; Imazio, M.; Lioncino, M.; Merlo, M.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Rare Cardiomyopathies in Adult and Paediatric Patients. A Position Paper of the Italian Society of Cardiology (SIC) and Italian Society of Paediatric Cardiology (SICP). Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 357, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, T.; Sonnenschein, S.; Schmidt, F.P.; Mollnau, H.; Bock, K.; Ocete, B.Q.; Münzel, T.; Theis, C.; Rostock, T. Cardiac Arrhythmias in Patients with Danon Disease. Europace 2017, 19, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darden, D.; Hsu, J.C.; Tzou, W.S.; von Alvensleben, J.C.; Brooks, M.; Hoffmayer, K.S.; Brambatti, M.; Sauer, W.H.; Feld, G.K.; Adler, E. Fasciculoventricular and Atrioventricular Accessory Pathways in Patients with Danon Disease and Preexcitation: A Multicenter Experience. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, C.; Jichi, F.; Pavlou, M.; Monserrat, L.; Anastasakis, A.; Rapezzi, C.; Biagini, E.; Gimeno, J.R.; Limongelli, G.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. A Novel Clinical Risk Prediction Model for Sudden Cardiac Death in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-SCD). Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2010–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, A.; Lafreniere-Roula, M.; Steve Fan, C.P.; Armstrong, K.R.; Dragulescu, A.; Papaz, T.; Manlhiot, C.; Kaufman, B.; Butts, R.J.; Gardin, L.; et al. A Validated Model for Sudden Cardiac Death Risk Prediction in Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2020, 142, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaski, J.P.; Norrish, G.; Ding, T.; Field, E.; Ziółkowska, L.; Olivotto, I.; Limongelli, G.; Anastasakis, A.; Weintraub, R.; Biagini, E.; et al. Development of a Novel Risk Prediction Model for Sudden Cardiac Death in Childhood Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-Kids). JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; De Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Cardiomyopathies. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiethoff, I.; Goversen, B.; Michels, M.; van der Velden, J.; Hiligsmann, M.; Kugener, T.; Evers, S.M.A.A. A Systematic Literature Review of Economic Evaluations and Cost-of-Illness Studies of Inherited Cardiomyopathies. Neth. Heart J. 2023, 31, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, A.; Miller-Hodges, E.; Castriota, F.; Takyar, S.; Howitt, H.; Ayodele, O. A Systematic Literature Review on the Health-Related Quality of Life and Economic Burden of Fabry Disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, P.; Bellenghi, M.; Manzini, V.; Crestini, A.; Pontecorvi, G.; Corbo, M.; Ortona, E.; Carè, A.; Confaloni, A. A Sex Perspective in Neurodegenerative Diseases: MicroRNAs as Possible Peripheral Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Rozas, A.; Fernández-Simón, E.; Lleixà, M.C.; Belmonte, I.; Pedrosa-Hernandez, I.; Montiel-Morillo, E.; Nuñez-Peralta, C.; Llauger Rossello, J.; Segovia, S.; De Luna, N.; et al. Identification of Serum MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers in Pompe Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019, 6, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeraro, M.; Sacchetti, E.; Deodato, F.; Coşkun, T.; Lay, I.; Catesini, G.; Olivieri, G.; Rizzo, C.; Boenzi, S.; Dionisi-Vici, C. A New UHPLC-MS/MS Method for the Screening of Urinary Oligosaccharides Expands the Detection of Storage Disorders. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrascanu, O.S.; Tutunaru, D.; Musat, C.L.; Dragostin, O.M.; Fulga, A.; Nechita, L.; Ciubara, A.B.; Piraianu, A.I.; Stamate, E.; Poalelungi, D.G.; et al. Future Horizons: The Potential Role of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, G.; Wu, L.; Wang, M.; He, X.; Wang, J.R.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Deep Learning Assessment of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Based on Electrocardiogram. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 952089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cau, R.; Pisu, F.; Suri, J.S.; Montisci, R.; Gatti, M.; Mannelli, L.; Gong, X.; Saba, L. Artificial Intelligence in the Differential Diagnosis of Cardiomyopathy Phenotypes. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Johnson, K.W.; Choi, E.; Kaplin, S.; Venner, E.; Murugan, M.; Wang, Z.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Amos, C.I.; Schatz, M.C.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Cardiovascular Genetics. Life 2022, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Sekar, P.K.; Veerabathiran, R. The Future of Artificial Intelligence and Genetic Insights in Precision Cardiovascular Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Cardiol. Discov. 2024, 4, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, B.; Taylor, M.; Adler, E.; Colan, S.; Ricks, D.; Yarabe, P.; Battiprolu, P.; Shah, G.; Patel, K.; Coggins, M.; et al. Phase 1 Study of AAV9.LAMP2B Gene Therapy in Danon Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 392, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).