Abstract

Introduction: Clinical variability within families harbouring disease-causing genetic variants hampers clinical care and risk stratification. We studied a multigenerational family presenting with sinus bradycardia and long QT syndrome type 2 (LQTS2). The family harboured a pathogenic variant in KCNH2, which co-segregated with the observed LQTS2. We studied the genetic cause of the high occurrence of sinus bradycardia in this family. Methods: Clinical data was collected, including heart rate, QT-interval, symptoms, and echocardiographic parameters. QTc was calculated using the Bazett and the Fridericia formula. Sanger sequencing of HCN4 was performed, followed by segregation analysis of the identified variant with sinus bradycardia. The biophysiological consequences of two variants, KCNH2-p.L69P (c.206T>C) and HCN4-p.R666W (c.1996C>T), were assessed by patch-clamp experiments. Therefore, a heterologous model was generated by transfection of HEK293A or CHO-k1 cells, respectively. Results: Sanger sequencing of HCN4 identified HCN4-p.R666W (c.1996C>T), which has a stronger segregation with the observed sinus bradycardia than KCNH2-p.L69P. Patch-clamp experiments revealed that KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W lead to a decrease in the corresponding current densities, which explains the LQTS and sinus bradycardia observed in the patients. Carriers of both genetic variants have a more severe LQTS2 phenotype, reflected in longer QT and higher incidence of syncope. Conclusions: We identified two (likely) pathogenic variants, KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W, co-segregating with LQTS2 and sinus bradycardia, respectively. Patients carrying both variants showed a more severe phenotype. These findings highlight the importance of additional genetic testing when discordant features are present, thereby enabling more accurate diagnosis, risk prediction, and management.

1. Introduction

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiac disorder characterized by prolongation of the QT-interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG) and increased risk of sudden cardiac death. QT-interval prolongation reflects delayed ventricular repolarization, which can lead to Torsades de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmia [1] and ventricular fibrillation (VF). LQTS affects approximately 1 in 2000 individuals [2] and can be inherited, typically due to rare pathogenic variants in distinct ion channel genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A) [3,4]. LQTS type 2 (LQTS2) is caused by loss-of-function variants in KCNH2, which encodes the pore-forming subunit of the rapid delayed rectifier K+ channel (KV11.1). This channel carries the rapid delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr), a key component of ventricular repolarization [5]. Impaired IKr due to pathogenic variants in KCNH2 delays the ventricular action potential and predisposes to life-threatening arrhythmias such as TdP and VF [6].

Because the ion channels involved in LQTS are also expressed in the sinoatrial node, LQTS-related pathogenic variants may also influence heart rate (HR) [7,8]. While sinus bradycardia has been reported in some LQTS subtypes, its association with LQTS2 has been limited to a few sporadic cases [9]. In contrast, rare pathogenic variants in HCN4, which encode the main contributor to the pacemaker (funny) current (If), are a well-established cause of sinus bradycardia [10,11,12,13].

HCN4 is activated at hyperpolarized voltages and plays a critical role in diastolic depolarization of pacemaker cells [14]. If is primarily present in the sinoatrial node, but also in the atrioventricular node, His bundle, and bundle branches [15]. Its function is modulated by intracellular cAMP, and depends on the coordinated interaction between the HCN domain, the voltage-sensing domain, and the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (CNBD) [16,17].

Autosomal dominant arrhythmia syndromes, e.g., catecholaminergic polymorphic tachycardia (CPVT), Brugada syndrome, and LQTS, often exhibit reduced penetrance and variable expressivity [18]. Accordingly, the clinical presentation of LQTS may vary widely and be influenced by multiple factors, including electrolyte imbalance, drugs, sex, age, and heart rate [1,19,20]. Lower heart rates may increase the likelihood of arrhythmic events in LQTS2, and patients with coexisting bradycardia may have a more severe clinical phenotype [21]. In addition, genotype–phenotype correlations play a major role in determining clinical manifestations and risk. For example, LQT1 is typically triggered by exercise or emotional stress, LQT2 by sudden auditory stimuli, and LQT3 by rest or sleep. These genotype-specific triggers, together with differences in QT dynamics and arrhythmic risk, are important for individual risk stratification and therapeutic management [1].

In this study, we describe a large multigenerational family with variable severity of LQTS2. Reassessment of the clinical data revealed the presence of an additional, distinct phenotype, sinus bradycardia, in a subset of individuals, which made treatment with beta-blockers particularly challenging. Although a pathogenic KCNH2 variant (p.L69P) co-segregated with the LQTS2 phenotype, it did not explain the bradycardia. This observation prompted further genetic testing, which revealed an additional variant in HCN4 (p.R666W) that segregated with sinus bradycardia.

We describe the clinical and electrophysiological effects of these two variants, including their cumulative impact on disease severity. Our study illustrates the importance of critical evaluation of the concordance between the expected phenotype based on the found genetic variant and the phenotype found in patients. When the clinical presentation deviates from what is expected based on the known variant, further genetic testing can uncover additional genetic variants with direct implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Assessment

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Amsterdam UMC and is in compliance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All medical data and DNA samples were analyzed after receiving informed consent of the patients, according to research protocols (VUmc_2020_4231 and W20_226 #20.260). All patients genetically related to the index patient are included; no exclusion criteria were applied.

2.2. ECG Analysis

ECG tracings were enlarged to facilitate manual analysis. QT duration (lead II or V5) was corrected for heart rate using Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT/√RR) or Fridericia’s formula (QTc = QT/RR0.33), where RR is the interval (in seconds), measured from the onset of a QRS complex to the onset of the following QRS complex. End of the T-wave was determined using the tangent method, defined as the intersection of a tangent to the steepest slope of the last limb of the T-wave and the isoelectric baseline (defined as the voltage at QRS onset). U-waves were excluded, and biphasic T-waves were included.

2.3. Genetic Analysis KCNH2

The KCNH2-p.L69P (c.206T>C) variant was identified during clinical genetic testing at Amsterdam UMC and is classified as pathogenic according to ACMG guidelines [22]. The variant was initially detected in the index patient following next-generation sequencing of a comprehensive LQTS gene panel. This was followed by cascade screening of family members, who underwent genetic testing for the KCNH2-p.L69P variant after clinical and genetic counselling.

2.4. Genetic Analysis HCN4

All HCN4 exons were sequenced in family member IV-14. In total, two variants were identified: one synonymous variant (c.3600A>G, p.P1200=) and one missense variant (c.1996C>T; p.R666W), located in exon 7. Based on ACMG guidelines, the p.R666W variant was classified as likely pathogenic and potentially responsible for sinus bradycardia in the family [22]. Segregation analysis of this variant was subsequently performed in the family. Genotyping for the HCN4-p.R666W (c.1996C>T) variant was carried out using PCR followed by Sanger Sequencing. Primer sequences are provided in the Supplementary Table S1. Both forward and reverse strands were sequenced using the BDT sequencing kit, and data were analyzed with CodonCode Aligner v6.0.

2.5. Calculation of eLOD Scores

We calculated estimated LOD scores (eLODs) according to the established framework provided by the ClinGen Gene Curation working group, version 11 [23]. For the calculation, affected patients were identified according to the following criteria: QT prolongation was defined as a QTc of >450 ms in males and >460 ms in females, or a QTc of >420 ms in males and >430 ms in females, combined with an abnormal T wave morphology. Bradycardia was defined as a HR of ≤50 bpm. Detailed prescription of the calculations are available in the Supplementary Materials.

2.6. Plasmid Acquisition and Cell Culture

2.6.1. KCNH2-p.L69P

The KCNH2-c.206T>C (p.L69P) variant was introduced into a wild-type pCGI-KCNH2-GFP-ires plasmid. Cell transfection with this plasmid results in the bicistronic expression of the KCNH2 channel and the GFP reporter. The KCNH2-L69P-GFP-ires construct was created by mutagenesis using the Quickchange-XL-site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent, Cat. #200517). Successful insertion of the variant was assessed by fragment sequencing. The primers used for mutagenesis and sequencing are available in the Supplementary Table S2.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293A) cells were transfected with the wild-type KCNH2-GFP-ires (WT) and/or KCNH2-L69P-GFP-ires (L69P) construct. Transfection with the variant was performed to mimic a homozygous (L69P-Hm) or heterozygous (L69P-Hz) expression. For heterozygous expression, the cells were transfected with WT- and L69P-plasmid in a 1:1 ratio. For all transfections, a total of 2 µg plasmid was used. As a control, cells were transfected with the empty GFP-IRES construct.

Transfection was performed in 6-well plates with a 70–80% cell confluency. The Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

2.6.2. HCN4-p.R666W

The sequence containing the c.1996C>T (p.R666W) variant was synthesized by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and subcloned into the wild-type HCN4-GFP-ires plasmid (WT). Correct insertion of the variant was confirmed by sequencing. Prior to transfection, CHO-k1 cells were cultured to a 70–80% confluency, in a 6-wells plate. Cells were transfected with a total of 2 μg DNA of the WT or HCN4-R666W-GFP-IRES (R666W) mutant plasmid. Transfection was performed with the Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (ThermoFisher) according to manufacturer’s guidelines.

CHO-k1 cells were used since they can sustain the hyperpolarizing voltages applied during the electrophysiological studies. These protocols have been optimized and published before [11].

2.7. Electrophysiological Measurements

Electrophysiological measurements were performed 36–48 h post-transfection on cells exhibiting green fluorescence. A small amount of cell suspension was placed in a cell chamber on an inverted microscope (Nikon, Eclipse Ti and Diaphot (Amsterdam, The Netherlands)) and cells were super fused with modified Tyrode solution (36 ± 1 °C) containing (mmol/L): 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 5.5 glucose, and 5.0 HEPES; pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). KCNH2 and HCN4 currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Patch pipettes were pulled from boroscilicate glass (TW100F-3, World Precision Instruments Germany Gmb, Friedberg, Germany) using a custom-made pipette puller. Voltage control, data acquisition, and analysis were realized with custom software [24]. Signals were low-pass filtered with a cutoff of 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Cell membrane capacitance (Cm) was determined [24]. Cm and series resistance were compensated for ≥80%. Data was collected from at least 3 transfections. The output is corrected for liquid junction potential.

Electrophysiological properties of KCNH2 and HCN4 were measured using patch-clamp, according to previously published methods which are described in the Supplementary Materials [11,25,26,27].

2.8. Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was carried out with Graphpad Prism v.10. Normality and equal variance assumptions were tested with the D’agostino Pearson and the Levene median test, respectively. Significance between current voltage (I–V) curves was tested using the two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA, followed by the Bonferonni post hoc test. Other parameters were tested using the unpaired t-test or, if normality and/or equal variance tests failed, the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test was performed. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Analysis

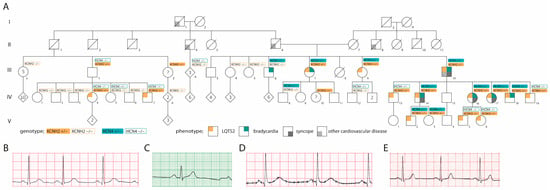

This study describes a large multigenerational family with a clear LQTS2 phenotype, in which several members were additionally found to have significant sinus bradycardia upon further clinical evaluation. Among 14 adults who tested positive for the KCNH2-p.L69P variant, 11 were diagnosed with LQTS2. One individual had a normal QTc, and two family members declined clinical evaluation. In addition, four children (aged 4–10 years) carried the KCNH2-p.L69P variant; one of them had a normal QTc, while the others showed QTc prolongation. The KCNH2-p.L69P variant and LQTS2 co-segregated throughout the family (Figure 1, Table S3).

Figure 1.

Pedigree and ECGs. (A) Pedigree, (B) ECG of patient carrying only KCNH2-p.L69P, (C) ECG of patient carrying only HCN4-p.R666W, (D) ECG of patient carrying both KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W, (E) ECG of healthy family member. “?” indicates a patient with unknown phenotype.

Eight out of nine adults carrying the HCN4-p.R666W variant exhibited (borderline) bradycardia. Two children (aged 4–10 years) also tested positive for the variant but had normal heart rates. In total, seven adults and two children were double heterozygous for both KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W. Notably, the HCN4-p.R666W variant and associated bradycardia segregated only among the direct relatives and descendants of the index patient (III-10). There was a trend toward a higher incidence of syncope in individuals carrying both variants compared to those with the KCNH2 variant alone (Figure 1, Table S3).

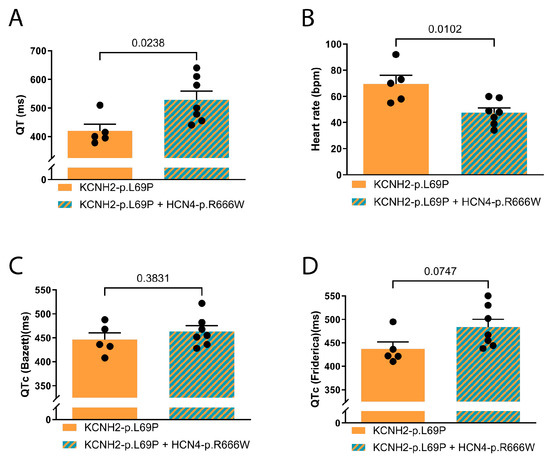

Statistical analysis showed that adult carriers of both KCNH2 and HCN4 variants had significantly longer QT intervals (uncorrected) and lower heart rates than carriers of the KCNH2 variant alone. In addition, the patients have a higher syncope incidence. The patients carrying only the KCNH2 variant did not experience syncope. In contrast, four out of nine patients carrying both the KCNH2 and HCN4 variants did experience syncope (Figure 2A,B, Table S4). One patient (IV-16) received a pacemaker after recurrent syncope.

Figure 2.

ECG parameters of adult family members. (A) QT in ms, (B) heart rate in beats per minute (bpm), (C) QT corrected with Bazett’s formula, (D) QT corrected according to Fridericia’s method. Statistics by t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Although Bazett’s formula is most commonly used in clinical practice, multiple studies suggest that Fridericia’s formula provides a more accurate QT correction in patients with sinus bradycardia. To reflect both clinical practice and physiological accuracy, we report QTc using both Bazett’s and Fridericia’s formulas (Figure 2C,D, Table S4). The difference in QTc using Fridericia showed a tendency of longer QTc in double carriers (p = 0.07) (Figure 2D, Table S4). The difference in QTc between double and single variant carriers was more pronounced with Fridericia’s correction than Bazett’s, consistent with the known better performance of Fridericia’s formula at lower heart rates. The use of Bazett’s correction in this setting may lead to QTc underestimation.

Beyond sinus bradycardia, (likely)pathogenic HCN4 variants have been associated with structural cardiac abnormalities. Echocardiography was performed in eight HCN4-p.R666W carriers, none of whom showed overt structural changes.

3.2. Genetic Testing

The index patient (III-10) presented with QTc prolongation and sinus bradycardia. Genetic evaluation using a comprehensive LQTS gene panel revealed a heterozygous KCNH2 variant at coding position 206 concerning a thymine to cysteine substitution (c.206T>C, rs199473665, MAF unknown) and resulting in a leucine to proline substitution at residue 69 (p.L69P). According to AMCG guidelines, this variant is classified as likely pathogenic [22]. Following the genetic diagnosis, family members were referred for clinical evaluation, genetic counselling, and if desired, genetic testing for the KCNH2-p.L69P variant. In total, 26 family members were tested, of whom 18 were found to carry the variant. The KCNH2-p.L69P variant co-segregated with LQTS phenotype (eLOD-score; 3.9). Although there was a suggestive trend toward co-segregation with sinus bradycardia, the eLOD score did not reach significance (eLOD-score;1.2).

Given the presence of sinus bradycardia in several family members and the limited association with KCNH2, sequencing of HCN4, a gene strongly linked to sinus bradycardia, was performed in the second son of the index patient (IV-14). This analysis identified a heterozygous nucleotide substitution at coding position c.1996C>T, resulting in an arginine to tryptophan change at residue 666 (p.R666W; rs199943122, MAF < 0.01). This residue lies within the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (CNBD) and is highly conserved across species. Based on ACMG guidelines, the variant is classified as likely pathogenic [22]. A total of 22 family members were tested for the HCN4-p.R666W variant, and 11 were found to carry it. Although causality could not be conclusively established, the segregation with sinus bradycardia was suggestive (eLOD score: 1.8). In total, nine family members were double heterozygous for both KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W.

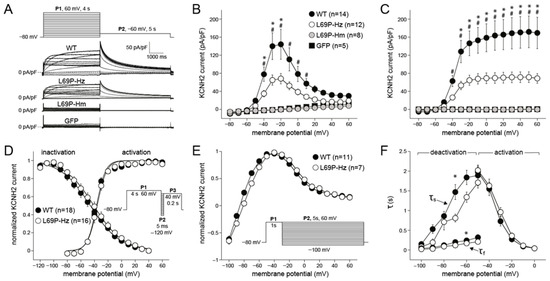

3.3. Functional Studies KCNH2-p.L69P

IKr was measured in HEK-293A cells transfected with wild-type KCNH2 (WT), KCNH2-p.L69P mimicking a homozygous (L69P-Hm) or heterozygous (L69P-Hz) expression, or an empty vector leading to expression of only GFP (GFP). This enabled the assessment of the biophysical properties of the KCNH2-encoded channels, including current density, activation, deactivation, and inactivation.

Figure 3A shows representative examples of the currents measured in the different groups elicited by a two-step voltage clamp protocol (inset). Typical steady-state and tail of IKr were activated in WT and L69P-Hz, with a significantly lower current density in L69P-Hz compared to WT cells (Figure 3B,C). For example, there was a 53% reduction in steady-state current (WT: 144 ± 32 pA/pF vs. L69P-Hz: 68 ± 11 pA/pF) after a depolarizing step to −20 mV. Typical IKr was virtually absent in L69P-Hm and GFP cells, suggesting that no functional channels are generated. Furthermore, there were no significant changes in V1/2 and k of activation, deactivation, or inactivation characteristics (Figure 3D–F). A detailed description is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of WT and L69P KCNH2 currents. (A) Representative examples of currents elicited by a two-step voltage clamp protocol (inset). P1 activated steady-state KCNH2 current in WT and L69P-Hz but not in L69P-Hm and GFP. IN WT and L69P-Hz, the current magnitude progressively increased and then decreased with voltage according to voltage-dependent inactivation. P2 elicited KCNH2 tail currents in WT and L69P-Hz; their peak is due to fast recovery from inactivation secondary to repolarization. The subsequent current decline is due to deactivation. (B,C) The average current densities of steady-state (B) and tail (C) currents. (D) The voltage-dependency of (in)activation in WT and L69P-Hz. The inset shows the 3-step protocol to determine the voltage dependency of inactivation. V1/2 and k did not differ significantly between WT and L69P-Hz. (E) Deactivation characteristics were determined using a two-step protocol. P1 activated steady-state KCNH2 current. P2 served to elicit KCNH2 tail currents at various potentials. At the more positive repolarizing voltages, KCNH2 currents showed inward rectification, and the current amplitude was relatively constant. With repolarizing steps to more negative voltages, the KCNH2 currents recovered from inactivation to reach a peak value around −40 mV. KCNH2 currents reversed in sign close to the equilibrium potential of K+, EK. The deactivation current–voltage (I–V) relationship was determined from the peak of the deactivating tail current during P2 and was not significantly different between WT and L69P-Hz. (F) Average (de)activation time constant of WT and L69P-Hz. * WT vs. L69P-Hz p ≤ 0.05, # WT vs. L69P-Hm p ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Thus, this functional study shows that when homozygous expression is mimicked, the mutation KCNH2-p.L69P leads to a complete loss of functional channels at the membrane. Co-expression of the mutated channel with the wild-type channel, mimicking heterozygous expression, leads to a significant reduction of IKr current density compared to wild-type.

In summary, the p.L69P variant led to a reduction in IKr current density without markedly altering the Ikr gating properties. This confirms that KCNH2-p.L69P is a loss-of-function variant, resulting in decreased IKr. As a result, the expected delay in ventricular repolarization is reflected as QTc prolongation on the ECG, consistent with the clinical observations in carriers of this variant described in our study.

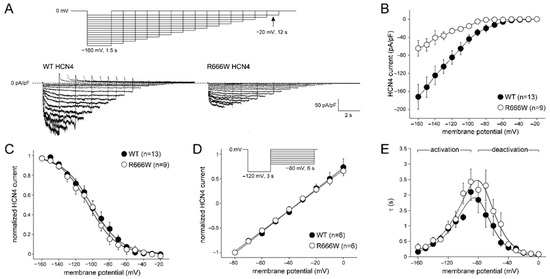

3.4. Functional Studies HCN4-p.R666W

HCN4 currents were measured in CHO-k1 cells transfected with wild-type HNC4 (WT) or HCN4-p.R666W. This enabled the assessment of biophysical properties of the HCN4 channels, consisting of current density, activation, deactivation, and reversal potential.

Figure 4A shows representative examples of WT and R666W HCN4 currents activated by hyperpolarizing voltage clamp steps (inset). Current density was significantly lower in cells expressing the mutant compared to WT HCN4 (p = 0.005, RM-ANOVA). For example, at −160 mV, current density of HCN4-R666W was −64 ± 16 pA/pF compared to HCN4-WT of −172 ± 24 pA/pF (Figure 4B), a reduction of 63%. Furthermore, there were no significant changes in V1/2 and k of activation, reversal potential, and speed of deactivation and inactivation (Figure 4C–E). A detailed description is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of WT and R666W HCN4 currents. (A) Typical HCN4 currents upon hyperpolarization voltage clamp steps (inset) in WT and R666W transfected cells. (B) The average HCN4 current density in R666W was significantly smaller compared to WT. (C) The voltage dependency of activation in WT and R666W was overlapping. Solid lines show the Boltzmann fit through the average data. (D) Reversal potential and deactivation characteristics were determined using a two-step protocol (inset). The first pulse activated the HCN4 current. The second pulse served to elicit HCN4 tail currents at various potentials. The I–V relationship was determined from the peak of the deactivating tail current during P2 and was not significantly different between normalized WT and R666W. (E) Average (de)activation time constants of WT and R666W. The solid lines are fits to the data according to τ = 1/[A1 × exp(−Vm/B1) + A2 × exp(Vm/B2)], where τ is the time constant of (de)activation, Vm is the membrane potential, and A1, A2, B1, and B2 are fitting parameters [28]. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

In summary, the R666W variant led to a reduced HCN4 current density without significantly altering gating properties. This indicates that HCN4-p.R666W is a loss-of-function variant, resulting in decreased If. The consequent slowing of action potential generation in pacemaker cells may lead to reduced heart rates, consistent with the sinus bradycardia observed in carriers of this variant in our study.

4. Discussion

We here describe a family with double heterozygosity for likely pathogenic variants in KCNH2 and HCN4, presenting with LQTS2 and sinus bradycardia. Carriers of both variants had longer QT intervals and a higher risk of syncope than carriers of only KCNH2-p.L69P. Patch-clamp analysis revealed reduced current densities of Ikr and If due to the KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W variants, respectively, with limited changes in gating properties, which explains both the LQTS2 and sinus bradycardia observed in the patients.

4.1. Treatment

Patients with LQTS2 are commonly treated with β-blockers, although their efficacy varies between agents [29,30]. In this family, treatment required individual tailoring due to the coexisting HCN4-p.R666W variant. In carriers with a low baseline heart rate, β-blockers caused marked sinus bradycardia with symptoms such as dizziness, syncope, and fatigue. The benefit of anti-adrenergic therapy in LQTS patients with sinus bradycardia remains uncertain compared with the broader LQTS population. While β-blockers are highly effective in preventing cardiac events in LQTS1 [31], their protective effect appears less consistent in LQTS2 and may depend on the specific agent used.

4.2. The Impact of Double Heterozygosity for HNC4-R666W and KCNH2-L69P

Pathogenic variants in HCN4 are linked to rhythm disorders and structural changes in the heart. The clinical spectrum of HCN4 variants includes sinus bradycardia, sinus node dysfunction with tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome, and ventricular arrhythmias [32,33,34,35]. More recently, multiple reports demonstrated a link between HCN4 variants and morphological abnormalities, including left ventricular non-compaction and dilatation of the ascending aorta [11,12]. Non-compaction cardiomyopathy has also been reported in a family with LQTS2 [36]. However, in the family reported here, no structural abnormalities were observed.

In this study it was not possible to compare carriers to non-carriers, due to the limited data of non-carriers. Nonetheless, this study does present important data on single and double carriers. The co-occurrence of the HCN4 and KCNH2 variant in patients has clinical implications, as double carriers tended to have a more prolonged QTc and seemed to be more symptomatic.

The more severe LQT2 phenotype in the double mutation carriers is likely related to the lower heart rates in this group. Additionally, If affects ventricular repolarization slightly, with a longer action potential duration by decreased If current [33]. Since HCN4 is predominantly expressed in the cardiac conduction system, the effect of a reduction in If current density on ventricular repolarization, and thus QTc, might be limited. However, it may be more pronounced in KCNH2 variant carriers due to the reduced repolarization reserve [37].

QTc duration prolongation is a well-recognized risk factor for the occurrence of cardiac events in patients with LQTS [38,39]. Risk of cardiac events increases with increasing QTc duration [38]. Genotype-positive LQTS patients with higher QTc values have a higher risk of cardiac events compared to those with QTc intervals within the normal range [40]. This relation is especially remarkable in patients with LQTS2 [40]. Therefore, a more stringent clinical follow-up of double carriers (in KCNH2 and HCN4) is warranted. In patients with LQTS2 and concomitant sinus bradycardia, management and follow-up should be individualized, as bradycardia-related symptoms may overlap with those of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, complicating clinical assessment. Closer surveillance, including frequent ambulatory ECG monitoring, is essential to a timely initiate or adjust β-blocker therapy and to evaluate the need for pacemaker implantation. In addition, the identification of two likely pathogenic variants within one family warrants accurate genetic counselling and cascade testing, as well as tailored cardiological screening recommendations, such as regular Holter monitoring to detect brady and/or tachyarrhythmias and exercise testing to assess chronotropic competence.

4.3. Previous Report of KCNH2-L69P and Other Variants in the PAS-Domain

Functional studies on the KCNH2-p.L69P variant have been previously described by Jenewein et al. [41]. Our results are in line with those in this previous report. However, Jenewein et al. did not present data on cells transfected with the mutated and WT channel in a 1:1 ratio to reflect the heterozygous state that occurs in patients. We chose to also reflect this in our experiments by transfecting the mutated and WT channel in a 1:1 ratio and showed a significant loss-of-function in a model mimicking heterozygous expression.

The KCNH2-p.L69P variant is located in the PAS domain of the channel. Variants in this domain often result in trafficking defects, thereby causing reduced currents. This is established by an impaired thermostability of the PAS-domain and its interaction with other channel domains [42]. A recent study performed a high throughput assay for trafficking defects. This showed that the L69P variant results in a complete loss of trafficking [43]). In addition, automated patch-clamp studies confirmed that the variant causes a loss-of-function. However, the effect size observed for the heterozygous expression model in this study was larger than that observed by us [43].

The KCNH2-p.L69P variant has only been previously described in one patient, namely a 35-year-old woman who presented with dizziness and syncope. The ECG showed a QTc of 478 ms, as well as TdP. Unfortunately, information about other family members is lacking, thereby limiting the evidence for causality of the variant.

Reports of other variants in the PAS domain show a wide range of clinical presentations, from mild QTc prolongation with occasional syncope to markedly prolonged QTc and multiple cases of sudden cardiac death within a single family. The underlying pathogenic variants in KCNH2 either impair channel trafficking (reducing current density) or alter channel kinetics [44,45,46].

4.4. Previous Reports of Variants in HCN4 CNBD-Domain

The HCN4-p.R666W variant has not been assessed before. Based on carriers having mild bradycardia and an incomplete penetrance of the phenotype, we predict the variant to not be dominant negative. Therefore, we performed the patch-clamp measurements on cells only expressing mutant or wild-type channel. With this method, we do collect the data required to conclude on the variants’ pathogenicity.

Another amino acid change affecting the same codon has been described, namely p.R666Q [47]. This variant led to a reduction in current density and channel conductance. Furthermore, the variant was not found to affect the cAMP sensitivity. Follow-up experiments showed that the variant leads to increased degradation of the channel [47].

Other pathogenic variants in HCN4 have been reviewed before [13,48]. Some of these studies have assessed the cAMP sensitivity of channels with variants in the CNBD (p.L573X, p.E695X, p.S672R), resulting in contradicting outcomes due to differences in applied models [32,49,50]. One study also performed in vivo experiments. The p.L573X variant results in a truncated c-terminus and a deletion of the CNBD. Patch-clamp experiments on transfected COS-7 cells showed an insensitivity of the channel to cAMP [34]. The complementary mice exhibited a reduced heart rate, but the capability of heart rate adaptation was preserved [51,52].

Despite possible differences in disease mechanism, the p.L573X, p.E695X, and p.S672R variants are all linked to sinus bradycardia [32,34,49]. This is in line with the association we found between the HCN4-p.R666W variant and sinus bradycardia in our family. In addition to reports of sinus bradycardia, there have been reports of cardiac structural changes reported in several families with other variants in HCN4, including non-compaction cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse (myxoid), and aortic dilatation [11,12,53]. Eight carriers of HCN4-p.R666W within our family had an echocardiography; structural changes were not observed in these patients.

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

In our study we functionally assessed the effects of KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W. Hereby, we could determine their effect on the IKr and If, respectively. While this enabled us to determine their pathogenicity, these experimental models are not fit to assess the effect of combined expression of KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W on cellular electrophysiology. However, our results could be used in follow-up experiments, such as in silico modelling, to predict the effect of KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W co-expression on the action potential.

4.6. Conclusions

We presented a family with double heterozygosity for KCNH2-p.L69P and HCN4-p.R666W, leading to LQTS2 and bradycardia, respectively. The coexistence of these two genetic variants contributes significantly to the observed clinical variability. Our data indicate that patients carrying both variants have a more severe LQTS2 phenotype. The presence of the HCN4 variant and associated sinus bradycardia should be carefully considered when selecting appropriate therapy. This highlights the importance of comprehensive phenotyping and coordinated clinical genetic testing within families. Functional studies of both variants support their pathogenic role.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cardiogenetics15040031/s1, including materials & methods and results, Table S1: primer sequences for PCR and sanger sequencing; Table S2: primer sequences for PCR and sanger sequencing; Table S3: clinical data; Table S4: average ECG parameters per group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.S.C., A.S.A. and E.M.L.; methodology: J.S.C., A.S.A. and E.M.L. investigation: J.S.C., A.S.A., F.T., K.A., A.V.P., S.N.v.d.C., O.N., C.P., L.B. and A.O.V.; formal analysis: J.S.C., A.S.A., F.T. and A.O.V.; writing—original draft preparation: J.S.C.; writing—review and editing: J.S.C., A.S.A., F.T., K.A., A.V.P., S.N.v.d.C., O.N., C.P., L.B., A.O.V. and E.M.L.; funding acquisition: E.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Research Council: NWO Talent Scheme VIDI-91718361 (E.M.L.) and the Amsterdam UMC funding scheme (J.S.C., E.M.L.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Amsterdam UMC and is in compliance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

All medical data and DNA samples were analyzed after receiving informed consent of the patients, according to research protocols (VUmc_2020_4231 and W20_226 # 20.260).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients and their relatives for participating in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wilde, A.A.M.; Amin, A.S.; Postema, P.G. Diagnosis, management and therapeutic strategies for congenital long QT syndrome. Heart 2022, 108, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.J.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; Crotti, L.; Pedrazzini, M.; Besana, A.; Bosi, G.; Gabbarini, F.; Goulene, K.; Insolia, R.; Mannarino, S.; et al. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2009, 120, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsheshet, A.; Dotsenko, O.; Goldenberg, I. Genotype-specific risk stratification and management of patients with long QT syndrome. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013, 18, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.; Novelli, V.; Amin, A.S.; Abiusi, E.; Care, M.; Nannenberg, E.A.; Feilotter, H.; Amenta, S.; Mazza, D.; Bikker, H.; et al. An International, Multicentered, Evidence-Based Reappraisal of Genes Reported to Cause Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Circulation 2020, 141, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, J.I.; Perry, M.D.; Perrin, M.J.; Mann, S.A.; Ke, Y.; Hill, A.P. hERG K+ channels: Structure, function, and clinical significance. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1393–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.R.; Winbo, A.; Abrams, D.; Vohra, J.; Wilde, A.A. Channelopathies That Lead to Sudden Cardiac Death: Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Heart Lung Circ. 2019, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, N.J.; Greener, I.D.; Tellez, J.O.; Inada, S.; Musa, H.; Molenaar, P.; DiFrancesco, D.; Baruscotti, M.; Longhi, R.; Anderson, R.H.; et al. Molecular architecture of the human sinus node insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation 2009, 119, 1562–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Xue, J.; Geng, L.; Zhou, L.; Lv, B.; Zeng, Q.; Xiong, K.; Zhou, H.; Xie, D.; Zhang, F.; et al. Cellular and molecular landscape of mammalian sinoatrial node revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilders, R.; Verkerk, A.O. Long QT Syndrome and Sinus Bradycardia—A Mini Review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, D. Funny channel gene mutations associated with arrhythmias. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4117–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, A.; Vermeer, A.M.C.; Lodder, E.M.; Barc, J.; Verkerk, A.O.; Postma, A.V.; Van Der Bilt, I.A.C.; Baars, M.J.H.; Van Haelst, P.L.; Caliskan, K.; et al. HCN4 mutations in multiple families with bradycardia and left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, A.M.C.; Lodder, E.M.; Thomas, D.; Duijkers, F.A.M.; Marcelis, C.; Van Gorselen, E.O.F.; Fortner, P.; Buss, S.J.; Mereles, D.; Katus, H.A.; et al. Dilation of the Aorta Ascendens Forms Part of the Clinical Spectrum of HCN4 Mutations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2313–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R. Pacemaker activity of the human sinoatrial node: An update on the effects of mutations in hcn4 on the hyperpolarization-activated current. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 3071–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, D. Pacemaker mechanisms in cardiac tissue. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1993, 55, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copier, J.S.; Verkerk, A.O.; Lodder, E.M. HCN4 in the atrioventricular node. Heart Rhythm 2025, 22, 2160–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porro, A.; Saponaro, A.; Gasparri, F.; Bauer, D.; Gross, C.; Pisoni, M.; Abbandonato, G.; Hamacher, K.; Santoro, B.; Thiel, G.; et al. The HCN domain couples voltage gating and cAMP response in hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. eLife 2019, 8, e49672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponaro, A.; Bauer, D.; Giese, M.H.; Swuec, P.; Porro, A.; Gasparri, F.; Sharifzadeh, A.S.; Chaves-Sanjuan, A.; Alberio, L.; Parisi, G.; et al. Gating movements and ion permeation in HCN4 pacemaker channels. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2929–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, A.A.; Behr, E.R. Genetic testing for inherited cardiac disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, P.J.; Ackerman, M.J.; Antzelevitch, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Borggrefe, M.; Cuneo, B.F.; Wilde, A.A.M. Inherited cardiac arrhythmias. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Bian, X.; Lv, J. From genes to clinical management: A comprehensive review of long QT syndrome pathogenesis and treatment. Heart Rhythm O2 2024, 5, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.J.; Priori, S.G.; Spazzolini, C.; Moss, A.J.; Vincent, G.M.; Napolitano, C.; Denjoy, I.; Guicheney, P.; Breithardt, G.; Keating, M.T.; et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: Gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001, 103, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinGen. Gene Disease Validity Curation Process. Standard Operating Procedure 2024, Version 11. Available online: https://clinicalgenome.org/docs/gene-disease-validity-standard-operating-procedures-version-11/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R. Injection of IK1 through dynamic clamp can make all the difference in patch-clamp studies on hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1326160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezzina, C.R.; Verkerk, A.O.; Busjahn, A.; Jeron, A.; Erdmann, J.; Koopmann, T.T.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; Wilders, R.; Mannens, M.M.A.M.; Tan, H.L.; et al. A common polymorphism in KCNH2 (HERG) hastens cardiac repolarization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R.; Schulze-Bahr, E.; Beekman, L.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; Bertrand, J.; Eckardt, L.; Lin, D.; Borggrefe, M.; Breithardt, G.; et al. Role of sequence variations in the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG, KCNH2) in the Brugada syndrome. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 68, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R. Human Sinoatrial Node Pacemaker Activity: Role of the Slow Component of the Delayed Rectifier K+ Current, IKs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Bourier, J.; Boukens, B.J.; Brouwer, I.A.; Wilders, R.; Coronel, R. Dietary fish oil reduces pacemaker current and heart rate in rabbit. Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chockalingam, P.; Crotti, L.; Girardengo, G.; Johnson, J.N.; Harris, K.M.; van der Heijden, J.F.; Hauer, R.N.; Beckmann, B.M.; Spazzolini, C.; Rordorf, R.; et al. Not all beta-blockers are equal in the management of long QT syndrome types 1 and 2: Higher recurrence of events under metoprolol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.J.; Zareba, W.; Hall, W.J.; Schwartz, P.J.; Crampton, R.S.; Benhorin, J.; Vincent, G.M.; Locati, E.H.; Priori, S.G.; Napolitano, C.; et al. Effectiveness and limitations of beta-blocker therapy in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2000, 101, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, J.I.; Lee, K.N.; Shim, J.; Ahn, H.S.; Kim, Y.H. Effectiveness of beta-blockers depending on the genotype of congenital long-QT syndrome: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, R.; Baruscotti, M.; Gnecchi-Ruscone, T.; DiFrancesco, D. Familial Sinus Bradycardia Associated with a Mutation in the Cardiac Pacemaker Channel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, K.; Hirano, Y.; Higashiuesato, Y.; Aizawa, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Inagaki, N.; Tana, T.; Ohya, Y.; Takishita, S.; Muratani, H.; et al. Role of HCN4 channel in preventing ventricular arrhythmia. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 54, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Bahr, E.; Neu, A.; Friederich, P.; Kaupp, U.B.; Breithardt, G.; Pongs, O.; Isbrandt, D. Pacemaker channel dysfunction in a patient with sinus node disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhme, N.; Schweizer, P.A.; Thomas, D.; Becker, R.; Schroter, J.; Barends, T.R.; Schlichting, I.; Draguhn, A.; Bruehl, C.; Katus, H.A.; et al. Altered HCN4 channel C-linker interaction is associated with familial tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiffa, T.; Tessitore, A.; Leoni, L.; Reffo, E.; Chicco, D.; D’Agata Mottolese, B.; Rubinato, E.; Girotto, G.; Lenarduzzi, S.; Barbi, E.; et al. Long QT syndrome and left ventricular non-compaction in a family with KCNH2 mutation: A case report. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 970240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, N.; Ortega, F.; Verkerk, A.O.; Mengarelli, I.; Krogh-Madsen, T.; Christini, D.J.; Coronel, R.; Vigmond, E.J. Validation of quantitative measure of repolarization reserve as a novel marker of drug induced proarrhythmia. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 145, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priori, S.G.; Schwartz, P.J.; Napolitano, C.; Bloise, R.; Ronchetti, E.; Grillo, M.; Vicentini, A.; Spazzolini, C.; Nastoli, J.; Bottelli, G.; et al. Risk stratification in the long-QT syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1866–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, A.J.; Moss, A.J.; McNitt, S.; Peterson, D.R.; Zareba, W.; Robinson, J.L.; Qi, M.; Goldenberg, I.; Hobbs, J.B.; Ackerman, M.J.; et al. Long QT syndrome in adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, I.; Horr, S.; Moss, A.J.; Lopes, C.M.; Barsheshet, A.; McNitt, S.; Zareba, W.; Andrews, M.L.; Robinson, J.L.; Locati, E.H.; et al. Risk for life-threatening cardiac events in patients with genotype-confirmed long-QT syndrome and normal-range corrected QT intervals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenewein, T.; Kanner, S.A.; Bauer, D.; Hertel, B.; Colecraft, H.M.; Moroni, A.; Thiel, G.; Kauferstein, S. The mutation L69P in the PAS domain of the hERG potassium channel results in LQTS by trafficking deficiency. Channels 2020, 14, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Ng, C.A.; Hunter, M.J.; Mann, S.A.; Heide, J.; Hill, A.P.; Vandenberg, J.I. Trafficking defects in PAS domain mutant Kv11.1 channels: Roles of reduced domain stability and altered domain-domain interactions. Biochem. J. 2013, 454, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.A.; Ullah, R.; Farr, J.; Hill, A.P.; Kozek, K.A.; Vanags, L.R.; Mitchell, D.W.; Kroncke, B.M.; Vandenberg, J.I. A massively parallel assay accurately discriminates between functionally normal and abnormal variants in a hotspot domain of KCNH2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Gao, M.; Fang, S.; Zheng, R.; Peng, D.; Luo, Q.; Yu, B. L51P, a novel mutation in the PAS domain of hERG channel, confers long QT syndrome by impairing channel activation. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 8040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grilo, L.S.; Schläpfer, J.; Fellmann, F.; Abriel, H. Patient with Syncope and LQTS carrying a mutation in the PAS domain of the hERG1 channel. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2011, 16, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossenbacker, T.; Mubagwa, K.; Jongbloed, R.J.; Vereecke, J.; Devriendt, K.; Gewillig, M.; Carmeliet, E.; Collen, D.; Heidbüchel, H.; Carmeliet, P. Novel mutation in the Per-Arnt-Sim domain of KCNH2 causes a malignant form of long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2005, 111, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, T.; Huang, Z.; Huang, J.; Geng, Z.; Cui, B.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Channel HCN4 mutation R666Q associated with sporadic arrhythmia decreases channel electrophysiological function and increases protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennis, K.; Biel, M.; Fenske, S.; Wahl-Schott, C. Paradigm shift: New concepts for HCN4 function in cardiac pacemaking. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2022, 474, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, P.A.; Duhme, N.; Thomas, D.; Becker, R.; Zehelein, J.; Draguhn, A.; Bruehl, C.; Katus, H.A.; Koenen, M. cAMP sensitivity of HCN pacemaker channels determines basal heart rate but is not critical for autonomic rate control. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2010, 3, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Marni, F.; Wu, S.; Su, Z.; Musayev, F.; Shrestha, S.; Xie, C.; Gao, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, L. Local and global interpretations of a disease-causing mutation near the ligand entry path in hyperpolarization-activated cAMP-gated channel. Structure 2012, 20, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alig, J.; Marger, L.; Mesirca, P.; Ehmke, H.; Mangoni, M.E.; Isbrandt, D. Control of heart rate by cAMP sensitivity of HCN channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12189–12194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidaud, I.; Chong, A.C.Y.; Carcouet, A.; Waard, S.D.; Charpentier, F.; Ronjat, M.; Waard, M.D.; Isbrandt, D.; Wickman, K.; Vincent, A.; et al. Inhibition of G protein-gated K+ channels by tertiapin-Q rescues sinus node dysfunction and atrioventricular conduction in mouse models of primary bradycardia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, P.A.; Schröter, J.; Greiner, S.; Haas, J.; Yampolsky, P.; Mereles, D.; Buss, S.J.; Seyler, C.; Bruehl, C.; Draguhn, A.; et al. The Symptom Complex of Familial Sinus Node Dysfunction and Myocardial Noncompaction Is Associated with Mutations in the HCN4 Channel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).