Abstract

With the rapid advancement of intelligent technologies in electric vehicles, various control technologies and algorithms are emerging. Most existing research, however, is limited to simulations of single modules such as suspension, braking, and battery management, lacking comprehensive modeling and simulation for the entire vehicle system, which impedes the integrated development and verification of advanced intelligent technologies. Therefore, this article focuses on the vehicle control system of electric vehicles. It first analyzes the overall scheme and clarifies the core functions of system operation control, fault detection, and storage. Subsequently, a data acquisition simulation platform for the vehicle control system is established based on MATLAB/Simulink, creating simulation modules for accelerator pedal, braking pedal, key position, and gear signal, forming a complete vehicle simulation platform. For the established simulation platform, specific electric vehicle model parameters are set, and under the QC/T759 urban driving conditions, simulations of the electric vehicle’s operation are conducted to obtain relevant signals such as vehicle speed, accelerator pedal, and braking pedal, verifying the feasibility of the vehicle control system. Finally, a hardware platform for the entire vehicle power system is built, and based on the PCAN-Explorer5 software, the connection and debugging of the vehicle controller, battery management system, and motor control unit are achieved to obtain the status parameters of each system and debug the vehicle control system, laying the foundation for the actual operation of the pure electric SUV. Through the simulation of the electric vehicle’s control system, the R&D cycle is greatly shortened, development costs are reduced, and a foundation is established for the actual vehicle debugging of electric vehicles.

1. Introduction

As the world’s largest automobile producer and seller, China has achieved international parity technological standards in the new energy vehicle (NEV) sector and boasts abundant industrial chain resources and market advantages [1]. At the policy level, the China NEV Industry Development Report (2024) [2] has clearly set the NEV sale target for 2025 at 15.5 million units, supported by incentive measures such as purchase tax reduction and exemption, to continuously drive the high-speed development of the industry. Market data shows that NEV sales reached 12.943 million units from January to October 2025, a year-on-year increase of 32.7%. Among them, the penetration rate exceeded 50% for the first time in October, hitting 51.6%. Battery electric passenger vehicles performed particularly prominently: 13 models achieved sales of over 100,000 units from January to September, with leading models taking the top sale positions, and the market as a whole maintained a strong growth momentum [3].

The vehicle control system is the core component of electric vehicles, performing functions including operational control, fault detection, diagnosis, and storage. In the event of a fault, the system can promptly execute corresponding fault handling and logging operations, thereby safeguarding both passenger safety and vehicle operational integrity. In structural design, such as in the design of the car’s exterior [4], the dynamic performance, smoothness, and handling stability of the vehicle are detected, and feedback is provided from the vehicle control platform regarding the parts of the vehicle structure that need optimization [5]. In terms of electronic control, various control algorithms are applied to the motor and battery, but simulation verification is only conducted on the motor and battery themselves, without undergoing vehicle-level control simulation verification [6]. Therefore, within the vehicle control platform, the current and voltage of the battery system are monitored in different driving environments, combined with the operational status of the battery pack, to optimize the design of the electric vehicle battery management system [7].

Furthermore, as the trend of electrification and intelligence in electric vehicles accelerates, smart control strategies such as assisted driving, automatic obstacle avoidance, and regenerative braking [8,9,10,11] are increasingly applied in vehicles. The design of the overall vehicle control platform is becoming increasingly important for developing new intelligent control strategies. Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADASs) have developed to the L2–L3 stage and are currently in a phase of rapid growth [12]. According to a market share report titled “2022 Autonomous Driving Development Platform Market Share” released by the International Data Corporation (IDC) on 28 April 2023, the market size of autonomous driving platforms in China reached CNY 8,112,000 in 2022, with a growth rate of 106%. This intelligent control strategy employs a hierarchical controller, which manages the upper-level algorithmic logic control and the lower-level execution control. The targets of the lower-level control primarily include the brake pedal and throttle opening, corresponding to vehicle braking and acceleration control [13]. Nevertheless, most existing studies focus on the simulation and optimization of a single subsystem, lacking an integrated modeling and hardware verification platform for vehicle-level control systems. In addition, most simulation research remains at the software level without deep coupling with real hardware platforms, making it difficult to pre-verify the performance of control algorithms in actual vehicles.

To achieve this goal, the vehicle control system is modeled based on MATLAB/Simulink 2022B, and simulation analysis is conducted under the QC/T759 urban operating condition with real vehicle parameters, which significantly shortens the development cycle of the electric vehicle control system and provides a reusable technical foundation for the vehicle-level integration of intelligent control algorithms.

2. Overall Solution for Electric Vehicle Control System

Currently, there are two types of vehicle control solutions for electric vehicles: centralized control and distributed control [14]. The distributed control system adopts modular management, where each sub-control system independently monitors its operational status and generates corresponding control data according to its predefined control strategy. It then transmits the necessary shared communication data to the vehicle control system via the CAN (Control Area Network) bus [15]. The vehicle control system integrates the information data from the sub-control systems to uniformly control the operation of the vehicle [16]. The information exchange among all sub-control systems reduces the probability of operational failures and is beneficial for the research and development work of sub-control systems; thus, it has increasingly attracted attention.

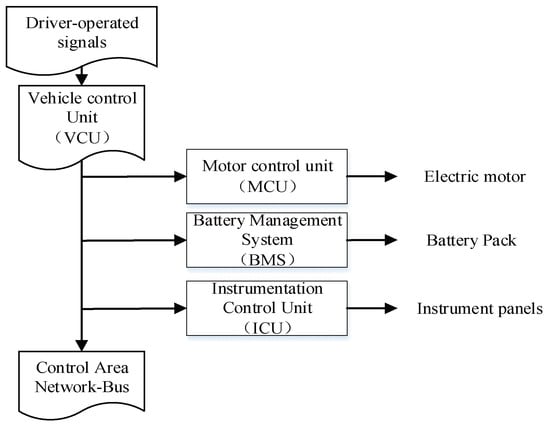

This article focuses on the distributed electric vehicle whole control system, as shown in the overall scheme Figure 1. By collecting driver operation signals and analyzing control strategies, control instructions are obtained [17]. These are then transmitted via the CAN bus to the Motor Control Unit (MCU), battery management system (BMS), and Instrument Cluster Modular (ICU). The MCU and BMS are responsible for monitoring and managing the power motor and power battery pack, each becoming an independent subsystem, while the ICU displays the basic operational status information of the vehicle.

Figure 1.

Vehicle distributed control system.

As the central coordinator, the VCU first parses the driver’s operational intentions such as accelerator/brake pedal opening and gear position and converts them into basic power demand or braking request. Subsequently, the VCU synthesizes information including battery status from the BMS, motor status from the MCU and vehicle status and imposes a series of constraints and arbitration mechanisms. For instance, when the state of charge (SOC) of the power battery is too low or its temperature is excessively high, the VCU will restrict the motor torque request to prioritize battery safety; when receiving accelerator and braking signals simultaneously, it will prioritize responding to the braking request to ensure vehicle safety. Ultimately, the VCU sends the feasible target torque or power commands, which have undergone coordination and constraint processing, to the MCU and transmits the necessary status information to the BMS and ICU.

To develop this distributed vehicle control system efficiently and reliably, first, based on the aforementioned overall scheme, the control system model is built and an offline simulation is conducted in the MATLAB/Simulink environment to verify the feasibility and performance of the control strategy. Subsequently, the verified control algorithm is deployed to the hardware prototype platform to form a hardware test environment. Finally, the PCAN-Explorer5 software is used for the online debugging and data monitoring of the hardware platform, completing the closed-loop verification from the model to physical prototype. The following text will elaborate on the work of these three stages in sequence.

3. Construction and Simulation of Vehicle Control System

Based on the overall scheme of the distributed control system determined in Section 2, the MATLAB/Simulink 2022B tool serves as a development platform based on model design, allowing for the establishment of a complete system model according to the development task. It validates the system design through simulation methods, thus reducing design costs and shortening the development cycle [18,19]. In MATLAB/Simulink 2022B, the modeling of the data acquisition platform for the vehicle control system and various signal simulation platforms is implemented.

3.1. Vehicle Control System Data Acquisition Platform

The vehicle control system mainly manages and controls the control information of each component [13]. According to the collected state information of each component, through the comprehensive analysis of the vehicle control system, the execution command is transmitted to the bottom layer for control [20].

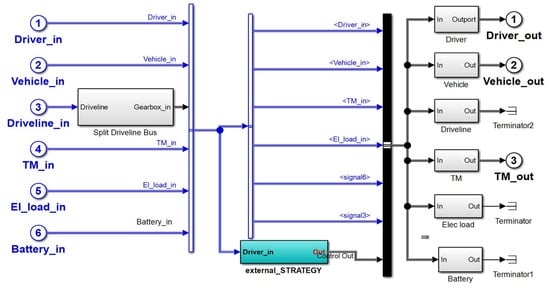

The data acquisition platform for the vehicle control system is shown in Figure 2. It collects signals including driver inputs, the current vehicle state, transmission system signals, and the status of the motor and battery. The vehicle control system analyzes these data and signals to obtain the correct instructions and transmits them to each sub-control system to complete the final work. The cyan module in the figure is the external energy management strategy module.

Figure 2.

Data acquisition platform of vehicle control system.

3.2. Accelerator Pedal Signal Acquisition Platform

The acquisition and processing of the accelerator pedal signal is a critical input for the entire vehicle, directly impacting driving safety. In order to prevent the vehicle control system from making errors in the acquisition of the accelerator pedal signal, the high and low signals are usually collected to improve the redundancy of the system and reduce the error rate of the system. Thus, the reliability of the accelerator pedal signal will be enhanced [21,22].

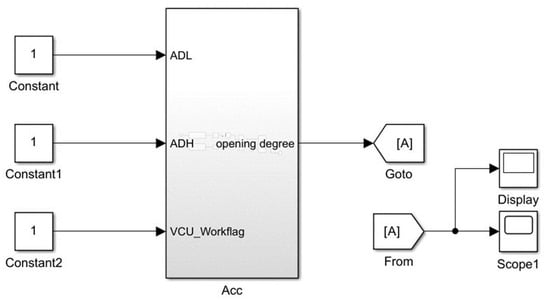

The accelerator pedal signal acquisition platform is shown in Figure 3. ADH and ADL stand for high signal and low signal, respectively. VCU_WorkFlag denotes the working state of the whole vehicle control system, where 1 describes the working state and 0 indicates the sleeping state.

Figure 3.

Accelerator pedal signal acquisition platform.

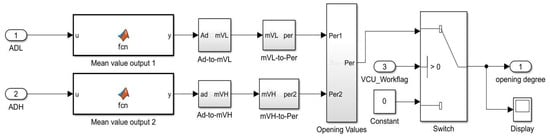

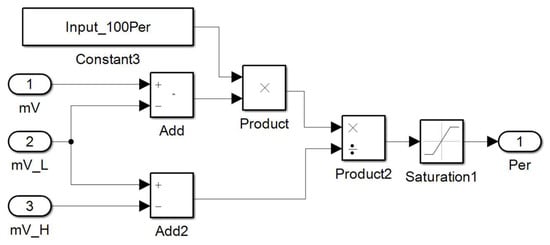

The intermediate frame (Acc) in Figure 3 is the corresponding accelerator pedal voltage value opening degree calculation algorithm, and the specific structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Accelerator pedal voltage value opening calculation.

Firstly, the collected ADH and ADL signal values are average filtered, and the filtered data is analyzed. The collected signal value is converted into a voltage value, which can be described as

where AD is the analog signal collected by the pedal sensor, and mV is the pedal voltage value.

Then, the accelerator pedal sensor voltage value is converted into the accelerator pedal opening degree, and the accelerator pedal opening degree function is shown as

where θ(k) is the accelerator pedal opening; V(k) is the accelerator pedal signal acquisition value; Vmax is the maximum effective value of the accelerator pedal signal, which is 4.5 V; and Vmin is the minimum effective value of the accelerator pedal signal, which is 0.5 V. It corresponds to the effective range of the output voltage of the accelerator pedal sensor. To suppress signal noise, a moving average filter is adopted, with a window size of 10 sampling points and a sampling frequency of 100 Hz.

The simulation module is established and shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Accelerator pedal opening function.

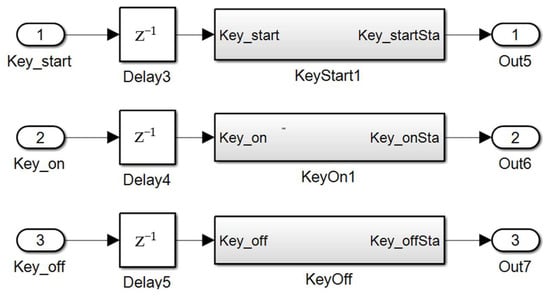

Finally, the pedal opening value calculated from the ADH and ADL signals is averaged and the data type is converted. And the final result is transmitted to the vehicle control system, thereby realizing the driver’s intention to operate the vehicle. These accelerator pedal signal value modules are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Accelerator pedal signal value calculation.

3.3. Brake Pedal Signal Acquisition Platform

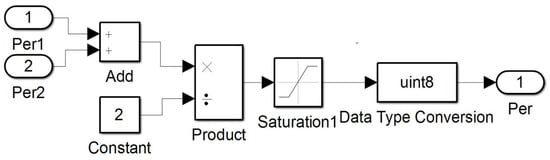

The vehicle control system collects the switch value of the brake pedal; that is, braking is defined as 1, and non-braking is defined as 0. When the driver needs to stop or encounters an emergency, the vehicle control system makes appropriate adjustments to the driving speed based on the collected brake pedal signals to ensure driving safety.

Given that the signal obtained from the brake pedal is a binary (switching) value while the signal derived from the accelerator pedal is an analog value, this distinction highlights the differing nature of data representation in automotive control systems. To reduce the error rate of the brake pedal, the brake pedal signal must be filtered. As shown in Figure 7, the brake pedal signal acquisition platform is established.

Figure 7.

Brake pedal signal acquisition platform.

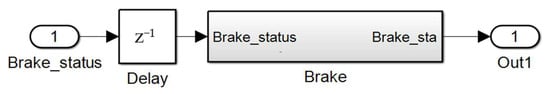

3.4. Key Position Signal Acquisition Platform

In order to prevent the electrical equipment from powering up at the same time, which may cause the power battery to overload instantly, the vehicle key position should change progressively. There are three key positions of OFF, ON and START in electric vehicles. Among them, OFF indicates that all electrical equipment except for the anti-theft system has been turned off. ON denotes that the entire vehicle is powered by a low-voltage battery and enters self-check mode. Electrical equipment, such as the radio, dashboard, and indoor lights, is working properly. START indicates that the entire vehicle is powered by high voltage, and equipment such as air conditioning and fuel pumps are operating normally. The driver’s choice of the key gear determines the switching of the vehicle’s working mode. To ensure the accuracy of signal acquisition by the vehicle control system and the normal operation of the vehicle, it is necessary to filter key signals to obtain continuous, accurate and stable signals. The key signal acquisition platform is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Key signal acquisition platform.

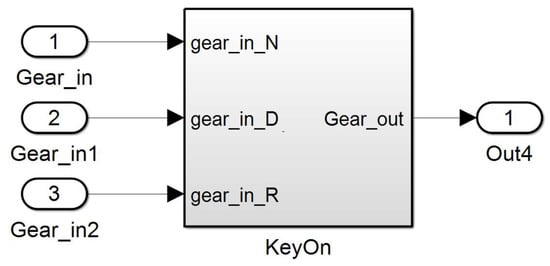

3.5. Gear Signal Acquisition Platform

Electric vehicles have three gears, forward (D), neutral (N), and reverse (R). By selecting the appropriate gear, the driver changes the operation mode and realizes the control of the vehicle. To ensure the validity of the driver’s operation intention, the vehicle control system only accepts one valid signal from the gear signal after the strategy analysis process and comprehensively controls the vehicle based on this signal. In addition, it is necessary to filter the gear signal so that it can be continuously and stably output, thereby ensuring the safety of the vehicle. The gear signal acquisition platform is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Gear signal acquisition platform.

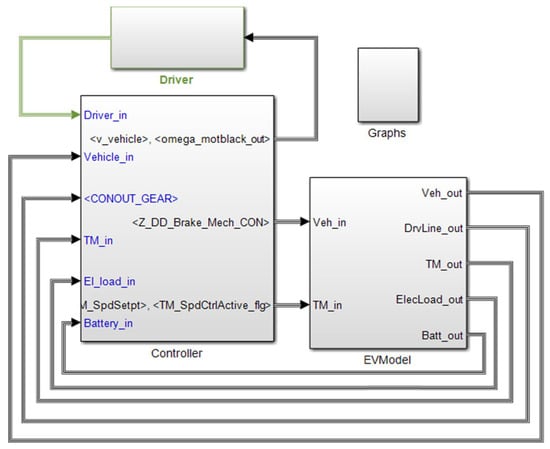

3.6. Vehicle Simulation Platform

The vehicle simulation platform mainly includes the driver information input module (driver), the control system module (controller), and the whole vehicle component module (EV Model). The controller module employs a speed-tracking PID algorithm. It computes the required accelerator or brake pedal command in real time by minimizing the error between the target speed (from the QC/T759 profile) and the actual simulated vehicle speed. To monitor the internal state of the system, all key signals are configured as global signals or shared through data storage. The Graphs monitoring module in the upper right corner of the platform tracks these signals and plots customized data acquisition graphs in real time for subsequent analysis. The specific model architecture is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Vehicle model simulation platform.

The EV Model is established based on vehicle longitudinal dynamics, and its motion equation can be expressed as

where is the driving force; is the vehicle mass; and is the vehicle acceleration. The rolling resistance coefficient = 0.015, the air resistance coefficient = 0.32, and the air density = 1.225 kg/m3.

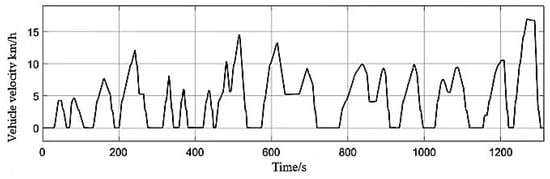

3.7. Simulation Result Analysis

Based on the simulation model, the overall parameters of the electric vehicle are input, with the specific data shown in Table 1. To verify the system performance, the urban driving cycle specified in the Chinese industry standard QC/T759-2006 [23] was selected for simulation testing.

Table 1.

Vehicle design parameters.

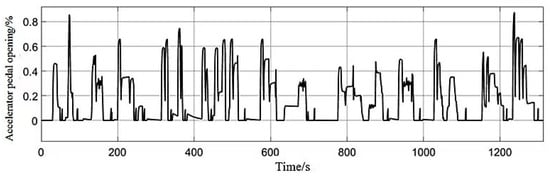

In the simulation, the speed–time sequence of the QC/T759 urban driving cycle is input into the controller module as the target vehicle speed. The controller calculates the accelerator or brake pedal opening command in real time via the PID algorithm based on the deviation between the target vehicle speed and the actual feedback speed, so as to drive the vehicle model to operate. The simulation step size is set to a fixed value of 0.01 s, and the total duration covers the complete operating cycle. Through the Graphs monitoring module in the platform, the time-domain data of key parameters such as vehicle speed and pedal opening are recorded and exported in real time for subsequent analysis.

Table 1 shows that electric vehicles are primarily used in urban settings, targeting the daily commuting population. Therefore, Chinese QC/T759 urban road cycle conditions are simulated. This driving cycle simulates the driving characteristics of typical urban roads in China and is commonly used for the performance evaluation of domestic new energy vehicles. Compared with internationally adopted driving cycles such as NEDC and WLTP, it is more consistent with the actual urban traffic environment in China. Therefore, the adoption of this driving cycle for simulation can effectively verify the adaptability and accuracy of the control system in urban commuting scenarios. The maximum speed of this driving cycle is 15 km/h with a relatively low average speed, which can effectively simulate typical driving scenarios such as frequent starts and stops and low-speed car following in downtown areas of large Chinese cities or traffic-congested road sections, and constitutes a stringent test for the transient response of the control system. This standard applies to urban buses and passenger cars, and vehicle performance tests can be conducted on chassis dynamometers and test roads. The “operation cycle” specifies the driving speed profile of the designated vehicle, with a time step of 1 s, described using a time–speed chart. The data structure of the QC/T759 conditions is partially illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data structure composition of QC/T759 working condition.

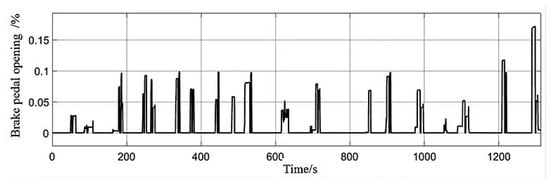

The vehicle parameters and the data pertaining to the QC/T759 operating conditions were input, resulting in simulation outcomes that reflect the electric vehicle’s speed, accelerator pedal position, and brake pedal engagement, as illustrated in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 11.

Vehicle velocity–time course.

Figure 12.

Accelerator pedal opening–time course.

Figure 13.

Brake pedal opening–time course.

The vehicle’s power performance was verified, as well as the acceleration control and braking control; the vehicle speed increases with the opening of the accelerator pedal and decreases with the opening of the brake pedal. Three peaks appeared within 0–200 s, corresponding to three peaks in the accelerator pedal opening. At 200 s, the speed rapidly decreases, corresponding to the rapid operation of the braking system before 200 s. If the accelerator pedal opening remains unchanged, such as at 650 s, the control system still ensures that the vehicle maintains a constant speed.

Comparing Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, the following conclusions can be drawn. When the opening of the accelerator pedal is at its peak, the corresponding vehicle speed will also change synchronously. When the opening of the brake pedal is at its peak, the vehicle speed slowly decreases as well.

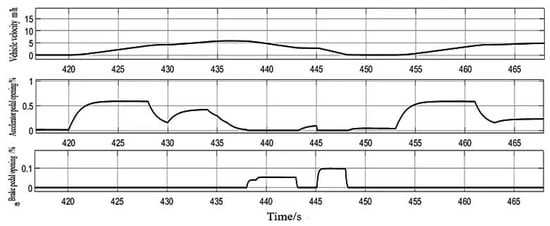

To facilitate a detailed analysis of the dynamic response characteristics of the control system under a typical driving cycle (encompassing start-up, acceleration, cruising, deceleration and restart), this study extracts a representative time window of 420–465 s from the QC/T759 driving cycle for an in-depth analysis. The variation trends of vehicle speed, accelerator pedal and brake pedal signals during this period are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Vehicle velocity, acceleration, and braking–time course.

As can be seen in Figure 14, the accelerator pedal opening is zero before 420 s when the vehicle is standing still. As the accelerator pedal opening curve rises, the speed curve also rises. Within 425 s, the driver releases the accelerator pedal, and the speed is still in a slow rising stage. The driver encountered an emergency at 437 s, and the accelerator pedal was released and the brake pedal was stepped down at the same time so that the speed decreased slowly, indicating that the simulation results were in line with the actual situation. In summary, the simulation results of the accelerator pedal and brake pedal signal acquisition and processing strategy are correct.

4. The Construction and Analysis of the Vehicle Power Hardware Platform

Existing test platforms for the research and development of electric vehicle control systems are often plagued by shortcomings such as single function and insufficient flexibility. Most of them are independent test benches for specific subsystems, lacking a vehicle-level electrical and communication integrated verification environment; the hardware connections are fixed, making it difficult to rapidly reconfigure to adapt to the testing requirements of different vehicle architectures or control strategies.

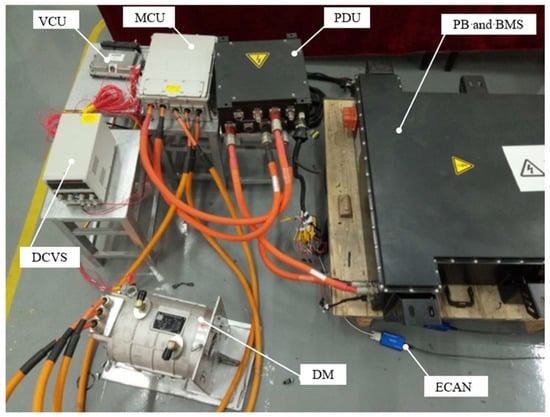

To address the above problems, this study builds a vehicle powertrain hardware platform as shown in Figure 15 based on the concepts of modularization, reconfigurability and high visibility.

Figure 15.

Physical connections of the vehicle components.

The hardware platform constructed in this study is a bench-level integrated test platform, which differs from a complete hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) test system in several key aspects. In a standard HIL architecture, the real-time simulation model and the actual hardware controller run simultaneously, forming a closed-loop test environment that includes simulated sensor feedback and actuator commands. In contrast, the platform proposed in this paper mainly focuses on the functional integration and communication debugging of physical vehicle components, without integrating the real-time simulated vehicle dynamics or powertrain model into the closed loop. During hardware testing, the controlled object model does not run in real time in Simulink; the system operates in an open-loop configuration, i.e., command signals are injected via PCAN-Explorer5, and the hardware responses are monitored and recorded. This method is intended to verify the communication protocols, control logic and interoperability between hardware components prior to HIL testing or vehicle-level testing.

4.1. Components of the Power System and Their Connections

Based on the overall parameters of the electric vehicle shown in Table 1, the vehicle power hardware platform was constructed, and connections between various components were established. The hardware platform includes the Vehicle Control Unit (VCU), power battery (PB), Drive Motor (DM), Motor Control Unit (MCU), Power Distribution Unit (PDU), Direct Current Voltage Stabilizer (DCVS), Enhanced Controller Area Network (ECAN), and associated wirings, as shown in Figure 15. Table 3 below presents the specifications of key hardware components.

Table 3.

Specifications of key hardware components.

The VCU (Figure 16) performs the comprehensive management of various components, collects the accelerator pedal position signal, brake pedal signal, and signals from other components for appropriate assessment, and then makes appropriate judgments to control the actions of the subordinate control units, thereby realizing the corresponding functions [22]. At the same time, the VCU can also manage and schedule the operating status of the entire vehicle via the CAN bus.

Figure 16.

VCU.

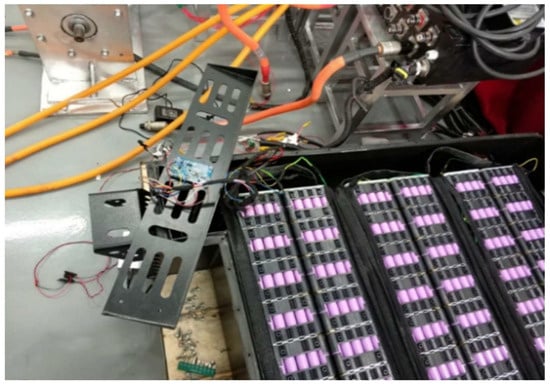

The power battery (PB) uses a nickel–cobalt–manganese lithium-ion battery pack, with a maximum voltage of 403.2 V and a maximum output current of 229.78 A. The BMS monitors and manages the state data of the PB and transmits the collected data to the VCU, achieving the optimal management of the vehicle’s energy, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Power pack and battery management system.

The Drive Motor (DM) is a permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) with the following specifications: a peak power of 60 kW, a peak torque of 210 N·m, a nominal voltage of 225 V, and a maximum rotational speed of 10,000 rpm.

Figure 18 shows that the Motor Control Unit (MCU) receives commands from the VCU to convert the electrical energy stored in the PB into the electrical energy required by the DM, ensuring stable power output and controlling the operating status of the electric vehicle, including startup, forward and reverse speed, and climbing force [24].

Figure 18.

Motor Control Unit (MCU).

The Power Distribution Unit (PDU) manages the high-voltage distribution of the power battery (PB) while ensuring the safety of all electrical equipment in the vehicle and preventing issues such as overcurrent, overvoltage, and overheating.

The Direct Current Voltage Stabilizer (DCVS) supplies 12 V power, which provides energy to various control units.

As depicted in Figure 19, the Enhanced Controller Area Network (ECAN) serves as a bridge for vehicle debugging, directly connecting to the computer. It is used to send and receive CAN bus data and to perform the maintenance and management of the bus system.

Figure 19.

Enhanced Controller Area Network (ECAN).

4.2. Joint Debugging of Vehicle Components

For the power hardware platform established in Figure 15, the PCAN-Explorer5 software is used to set up an online debugging system for tuning the vehicle’s power system, recording and analyzing relevant data, and controlling the overall vehicle operation [21]. PCAN-Explorer5 is a CAN bus data monitoring and analysis software launched by the German company PEAK-System (Dresden, Germany). Its core functions include receiving and sending CAN bus messages and filtering and recording bus data, and it also supports importing dbc files, allowing raw CAN messages to be parsed into easily understandable physical quantity data. It is widely used in fields that rely on CAN bus, such as automotive (including electric vehicles) and industrial control, to assist in debugging control systems, validating data, and other tasks [25].

4.2.1. Online Debugging Interface

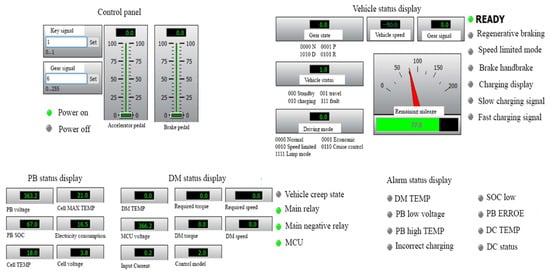

Based on the PCAN-Explorer5 software, Figure 20 provides a control data display interface designed for the entire vehicle, which displays the parameters of the hardware platform. The main data displayed is as follows.

Figure 20.

Parameter display after successful power-up of the whole vehicle.

- Control Panel: Simulates the driver’s operations for the vehicle. The control panel visually represents vehicle operations such as Power On, Power Off, Accelerator Pedal, Brake Pedal, Key Signal, and Gear Signal [26].

- Vehicle Status Display: Functions similarly to the vehicle’s instrument display system; it includes parameters such as Vehicle Driving Mode, Vehicle Speed, Gear Signal, and Remaining Mileage.

- Power Battery (PB) Status Display: Displays key metrics such as PB Voltage, PB State of Charge (SOC), Cell Voltage, Cell Temperature, Maximum Cell Temperature, and Electricity Consumption.

- Drive Motor (DM) Status Display: Includes critical data such as DM Speed, DM Torque, DM Temperature, Required Speed, Required Torque, MCU Voltage, Input Current, and Control Mode.

- Alarm Status Display: The alarm status displays some important fault parameters, including Vehicle Creep State, Main Relay, Main Negative Relay, MCU Temperature Alarm, DM Temperature Alarm, PB Low-Voltage Alarm, PB High-Temperature Alarm, Incorrect Charging Alarm, SOC Low Alarm, PB ERROR Alarm, DC Temperature Alarm, and DC Status Alarm.

4.2.2. Debugging Measured Parameters

The simulation of driver operations includes different driving phases such as forward driving, braking and deceleration, and reverse driving. During the simulation, the Vehicle Control Unit (VCU) collects status information from other components, providing a clearer understanding of how the data evolves throughout the simulation process.

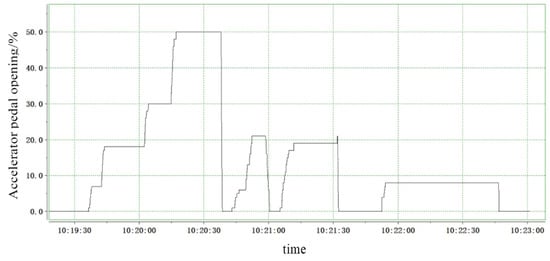

- Accelerator Pedal Position Value

In this hardware platform, there is no physical accelerator pedal; thus, the VCU cannot receive voltage signals from a pedal displacement sensor. Instead, the accelerator pedal signal value is directly input into PCAN-Explorer5. The accelerator pedal position value changes over time, as shown in Figure 21, and its variation exhibits a step-like pattern.

Figure 21.

Instantaneous accelerator pedal position.

- 2.

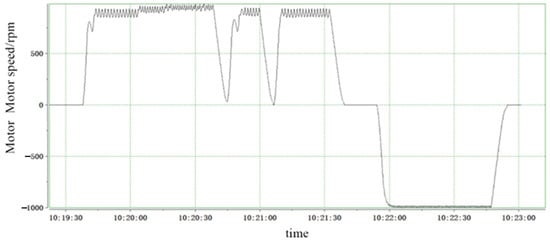

- Motor Speed

During the simulation, the variation in motor speed is analyzed to assess the vehicle’s motion state. The complete simulation results of motor speed over time are illustrated in Figure 22 and are divided into three phases. In the initial phase, the motor speed is zero. Subsequently, upon receiving the accelerator pedal signal value, the VCU issues a forward command to the MCU, which causes the motor speed to instantly increase and stabilize at a certain level. During reverse operation, the motor rotates in the opposite direction.

Figure 22.

Instantaneous motor speed.

- 3.

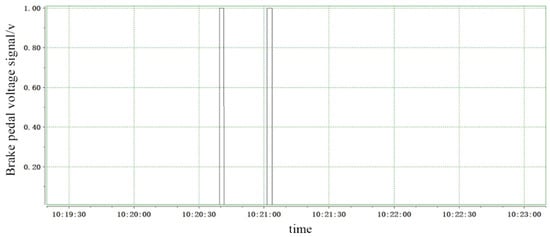

- Brake Pedal Voltage Signal

The status of the brake pedal signal is collected, where pressing the brake pedal corresponds to a value of 1 and releasing it corresponds to a value of 0. The relationship between the brake pedal voltage signal and time is illustrated in Figure 23. During the forward rotation of the motor, there are two situations where the speed will decrease. At these moments, the brake pedal signal is recorded as 1, used to simulate the vehicle’s response to emergency situations through braking.

Figure 23.

Instantaneous brake pedal voltage signal.

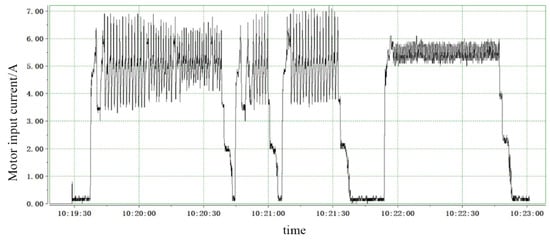

- 4.

- Motor Input Current

The motor input current is illustrated in Figure 24. Initially, since the power battery does not supply power to the motor, the input current is equal to the external steady-state current during the low-voltage power-up phase of the vehicle. Then, a steep curve appears due to a sudden change in the accelerator pedal signal value. The motor requires a significant amount of current for instantaneous rotation. As the motor speed reaches its maximum, the input current stabilizes. During reverse operation, the current fluctuations are more frequent and compact. This fluctuation is primarily attributed to a mismatch between the commanded accelerator pedal position and the resulting motor speed response curve during the design phase of the vehicle control system [27].

Figure 24.

Instantaneous motor input current.

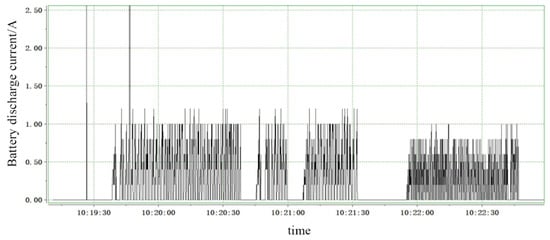

- 5.

- Battery Discharge Current

The battery discharge current is depicted in Figure 25. In the initial phase, there is a sudden spike in the signal value, indicating the successful power-up of the vehicle, where the battery experiences an instantaneous discharge current [28,29]. The subsequent blank time period corresponds to the waiting state for the driver’s operational signal input, during which there is no discharge current from the battery. Aside from the initial spike in current at the beginning, another sudden change in current is observed during normal motor operation. This is primarily due to a rapid increase in the accelerator pedal signal, prompting the battery management system (BMS) to receive acceleration commands from the vehicle controller. Consequently, with the motor operating under no load conditions, the discharge current value experiences a sudden increase.

Figure 25.

Instantaneous battery discharge current.

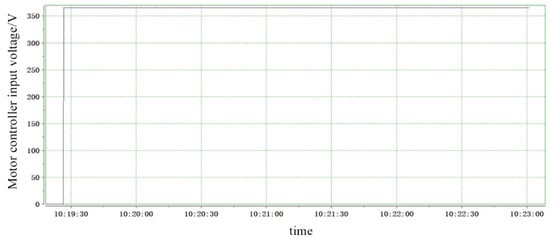

- 6.

- VCU Input Voltage

As shown in Figure 26, the voltage signal of the Motor Control Unit (MCU) is only displayed during the operation of the motor. Throughout the entire simulation debugging process, the input voltage of the Vehicle Control Unit (VCU) corresponds to the discharge voltage of the battery and remains relatively constant.

Figure 26.

Input voltage of motor controller.

The online debugging of the hardware platform enabled the simulation of various vehicle operational states and the analysis of measured data. The results demonstrate that the vehicle controller can respond to a change in the pedal position promptly and can effectively manage the parameters of the motor and the battery, so as to facilitate the driver in controlling the vehicle.

5. Conclusions

Current research on EV intelligent technology often focuses on single modules, lacking full-vehicle system-level modeling and validation. To address this limitation, this paper conducted modeling and simulation research on an EV control system using the MATLAB/Simulink platform. During the modeling process, key tasks included the construction of collection modules and processing algorithm design for accelerator pedal signals, brake pedal signals, key position signals, and gear position signals. By integrating various signal processing units, the overall vehicle control strategy module, and subsystem interaction logic, a completely functional vehicle simulation platform was established. To validate system performance, parameters of a specific pure electric SUV model were selected, and simulation tests were conducted under the QC/T 759-2006 urban road cycle conditions. By collecting data such as vehicle speed variation curves, pedal signal response characteristics, gear switching logic, and fault simulation feedback, the dynamic response and control accuracy of the whole vehicle control system in different driving scenarios were thoroughly analyzed. The results showed that the constructed model could accurately replicate the vehicle operating state, confirming the feasibility and accuracy of the whole vehicle control system. To further support real vehicle applications, a vehicle power hardware platform was established, and CAN bus communication connections and collaborative debugging between the Vehicle Control Unit (VCU), battery management system (BMS), and Motor Control Unit (MCU) were achieved using PCAN-Explorer5 software. The core verification of this study lies in the successful implementation of the complete R&D chain of model simulation–hardware-in-the-loop–integrated debugging. Specifically, the control logic verified in the simulation model is directly applied to the VCU of the hardware platform; the communication protocols defined in the simulation are strictly implemented and verified during hardware debugging; and the dynamic system response observed on the hardware platform is consistent with the trend of the simulation results. This consistency verification demonstrates that most control logic and system integration issues can be identified and resolved in advance through high-fidelity preliminary simulation. Compared to data-driven intelligent strategies with high model dependence [30], this study focuses on the reliability, real-time performance and engineering implementability of the control system architecture, laying a solid system-level foundation for the subsequent integration of advanced algorithms. The vehicle control system model and hardware platform developed in this study not only effectively shorten the development cycle of new energy vehicles and cut costs but also provide a standardized foundation for the integration and validation of advanced intelligent control technologies, laying solid technical support for the mass production and safe operation of pure electric SUVs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.; methodology, S.W. and J.X.; software, S.Z. and Y.G.; formal analysis, J.X. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Major Science and Technology project (BG2024011) and Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Multi-energy Integration and Flexible Power Generation Technology project (MEIP202506).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, X.B.; Lv, C.M. Study on the development process of China’s new energy vehicles: From scientific research breakthroughs to industrial breakthroughs. Emerg. Sci. Technol. Trends 2025, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- China Automotive Technology and Research Center; Nissan (China) Investment Co., Ltd.; Dongfeng Motor Corporation. China New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Report (2024); Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CNR Online. Delivering Excellent Results in the “14th Five-Year Plan”: China’s Auto Industry Moves to the “Second Half”. Available online: http://www.cnr.cn/2013qcpd/yc/20251028/t20251028_527410073.shtml (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Liu, W.T.; Xia, Z.T. Optimization path analysis of low aerodynamic drag and integrated cooling design for electric vehicle exterior. Spec. Purp. Veh. 2025, 4, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. Control and optimization design of pure electric vehicle power system. Mot. Veh. Maint. Repair 2024, 11, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Makrygiorgou, J.J.; Alexandridis, A.T. Power electronic control design for stable EV motor and battery operation during a route. Energies 2019, 12, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Cheng, D.Q.; Yang, F.; Fu, Y. Adaptive particle swarm optimization-support vector machine for power battery self-discharge diagnosis. J. Automot. Eng. 2024, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.W.; Li, S.H.; Ren, J. Study on dynamic characteristics of multi-vehicle-bridge coupled system for intelligent driving electric vehicles. Acta Mech. Sin. 2022, 54, 2627–2639. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Liu, D.; Lu, X.; Xu, J. ECO driving control for intelligent electric vehicle with real-time energy. Electronics 2021, 10, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, L.; Cai, X.; Zheng, T. Personalized collision avoidance control for intelligent vehicles based on driving characteristics. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Pi, D. Intelligent vehicle driving decisions and longitudinal–lateral trajectory planning considering road surface state mutation. Actuators 2025, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, B.; Zhou, H.; He, J. Impact and revolution on law on road traffic safety by autonomous driving technology in China. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2023, 51, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, H. An adaptive cruise control strategy for intelligent vehicles based on hierarchical control. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.L.; Yan, W.M.; Guo, J.M. Design of vehicle controller for hybrid electric vehicles. J. Harbin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Wang, L.F.; Liao, C.L.; Ji, L.; Xu, D.P.; Dong, F.Y. Research on collaborative and orderly control of electric vehicles and distributed power sources. Trans. China Electro-Tech. Soc. 2015, 14, 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.P.; Que, T.L. Development and research of electric vehicle control system based on model design. Autom. Instrum. 2017, 32, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.D.; Yin, H.T.; Dong, L.Y.; Li, J.Y. Design of a pure electric vehicle control system based on Simulink. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2020, 20, 2885–2891. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D.T.; Chen, S.J.; Hu, M.H.; Wei, H.B. Power drive control strategy of pure electric vehicle based on driver intention recognition. Automot. Eng. 2015, 1, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C. Design and Application of Electric Vehicle Simulation Model Based on Matlab/Simulink. Master’s Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (School of Engineering Management and Information Technology), Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.H.; Fan, J.W.; Tan, G.X. Modeling and simulation of hybrid electric vehicle based on Matlab/Simulink. Comput. Mod. 2014, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L. Research on design of whole vehicle control system based on Simulink for pure electric vehicle. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2022, 20, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; He, H. Design of power supply for whole vehicle controller based on TC377 microcontroller. Tract. Farm Mach. 2024, 51, 72–74+86. [Google Scholar]

- QC/T 759-2006; City Driving Cycle for Vehicle Testing. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Tao, F.F.; Lu, J.W. Analysis of test verification for fault diagnosis and handling system based on VCU. Intern. Combust. Engine Spare Parts 2024, 17, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.Y.; Ji, S.B.; Wei, J.H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.P.; Jiang, Y. Design of whole vehicle controller for pure electric loader. Intern. Combust. Engine Power Plant 2024, 41, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.L.; Huang, Z. Research on hardware-in-the-loop technology modeling for the whole vehicle controller of a pure electric vehicle. Intern. Combust. Engine Parts 2023, 14, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Du, F.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G. Energy recovery based on pedal situation for regenerative braking system of electric vehicle. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2020, 58, 144–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lei, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, X. An optimal slip ratio-based revised regenerative braking control strategy of range-extended electric vehicle. Energies 2020, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M. Research on Whole Vehicle Controller and Control Strategy for Pure Electric Vehicle. Master’s Thesis, Harbin University of Science and Technology, Harbin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.X.; He, H.W.; Peng, J.K.; Chen, W.; Wu, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, J. A comparative study of deep reinforcement learning based energy management strategy for hybrid electric vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.