Abstract

Automated driving technologies have the capability to significantly increase road safety by decreasing accidents and increasing travel efficiency. This research presents a decision-making strategy for automated vehicles that models both lane changing and double lane changing maneuvers and is supported by a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) algorithm. To capture realistic driving challenges, a highway driving scenario was designed using the professional multi-body simulation tool IPG Carmaker software, version 11 with realistic weather simulations to include aspects of rainy weather by incorporating vehicles with explicitly reduced tire–road friction while the ego vehicle is attempting to safely and perform efficient maneuvers in highway and merged merges. The hierarchical control system both creates an operational structure for planning and decision-making processes in highway maneuvers and articulates between higher-level driving decisions and lower-level autonomous motion control processes. As a result, a Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) agent was created as the DRL approach to achieving decision-making in adverse driving conditions, which was built in MATLAB version 2021, designed, and tested. The study thoroughly explains both the Duel-DDPG and standard Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithms, and we provide a direct performance comparative analysis. The discussion continues with simulation experiments of traffic complexity with uncertainty relating to weather conditions, which demonstrate the effectiveness of the Duel-DDPG algorithm.

1. Introduction

The Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered automated vehicles, categorized under SAE levels 3, levels 4, and levels 5, are increasingly being adopted due to their potential to decrease traffic collisions and increase road effectiveness [1,2]. These levels of automation range from conditionally automated driving (Level 3), where the system handles most driving tasks under specific conditions, to fully automated driving (Level 5), where human intervention is entirely unnecessary. Achieving a fully automated system requires the seamless integration of four core functional modules: environment perception, behavioral decision-making, path planning, and control execution [3]. The environment perception module is responsible for interpreting the environment through various sensors such as LIDAR, radar, and cameras. Decision making involves selecting the optimal driving behavior based on perceived information, while planning determines the specific trajectory to execute these decisions. Finally, the control module ensures accurate actuation of steering, throttle, and braking to follow the planned path. Although considerable progress has been achieved in each of these modules individually, additional research is still required to overcome challenges posed by complicated and unpredictable traffic scenarios. Automated vehicles must operate in highly dynamic environments that involve interactions with human-driven vehicles, pedestrians, and varying road conditions. These vehicles are expected to continuously perform maneuvers that depend heavily on precise acceleration and steering control to maintain stability and passenger comfort. Consequently, significant effort has focused on developing robust and reliable decision-making protocols for autonomous vehicle systems. For example, Hole et al. [4] applied the Monte Carlo–driven search techniques to formulate decision-making approaches within a Markov decision process (MDP) with partial observability, comparing their results with neural network-based policies. Their study explored optimized lane-changing strategies designed to maximize limited road capacity and reduce vehicle conflicts. Likewise, in [5], researchers investigated decision-making methods for autonomous highway exits, showing through 6000 stochastic simulations that their proposed controller significantly improved the success rate of exit maneuvers.

The Reinforcement learning (RL) approaches, notably Deep reinforcement learning (DRL), have emerged as powerful tools for handling the complexities of decision making in automated driving [6]. The DRL techniques are most appropriate for addressing intricate sequential decision problems where the system must learn policies directly from interactions with the environment. In the autonomous driving field, many studies have explored DRL-based solutions. For instance, Duan et al. [7] proposed a tiered RL framework to learn decision policies without relying on pre-labelled driving data, thereby reducing the need for costly manual explanation. Other studies [8] applied DRL methods to challenges such as collision avoidance and path tracking, demonstrating improved control performance compared to traditional RL-based and rule-based approaches. Additionally, researcher in [9,10] expanded the focus of DRL beyond safety and fuel-efficient path planning, primarily utilizing the Deep Q-learning (DQL) procedure, which has proven efficient at achieving multiple, often conflicting, driving goals. In [11], the authors introduced a motion planning approach based on DRL for autonomous highway driving, particularly targeting complex tasks such as merging onto highways, navigating two-lane roads, and performing lane change maneuvers. Their method employed a fully integrated learning system by the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) method with carefully designed reward mechanisms, aiming to balance safety, efficiency, and comfort on highways. Building on this concept, the present study applies the Dueling Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) approach to handle long-duration highway navigation tasks, including lane keeping, single lane changes, and double lane changes. A notable strength of the Duel-DDPG algorithm is its capability to manage continuous action spaces, allowing detailed control of vehicle steering, speed, and braking. Such continuous control is essential for smooth, safe, and comfortable highway driving, particularly under dynamic and uncertain traffic conditions. By employing an actor–critic structure, Duel-DDPG enables autonomous vehicles to produce continuous control signals that support natural and effective decision-making in complex traffic scenarios [12].

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has been widely studied for making decisions in autonomous driving because it can learn complex policies by interacting with changing environments. Early research showed that applying reinforcement learning to driving tasks like lane keeping and car-following was possible using value-based and policy-gradient methods [13]. With the rise of deep neural networks, DRL methods such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and actor-critic architectures have been effectively used in highway driving scenarios that involve lane changing and merging [14,15]. Deterministic policy gradient methods, especially Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), have drawn attention for continuous control tasks in autonomous driving because they can manage continuous action spaces [16]. Enhancements to DDPG, like Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) and dueling architectures, have improved training stability and performance in complex traffic situations [17]. Several studies have looked into multi-agent highway scenarios, where the interactions among nearby vehicles greatly influence decision-making performance [18]. Safety is a significant concern in DRL-based autonomous driving. Previous research has addressed safety-aware reinforcement learning through reward shaping, constraint-based learning, and shielded policies to lower the risk of collisions [19,20]. However, many of these methods depend on simplified traffic or environmental assumptions. Environmental uncertainty, such as bad weather, has received less attention, with most studies presuming ideal sensing and unchanging road conditions [21]. Additionally, many existing studies treat autonomous driving as a fully observable Markov Decision Process (MDP), even though real-world driving environments are typically partially observable. Recent research has introduced Partially Observable MDP (POMDP) formulations using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or memory-based architectures to tackle hidden states and temporal dependencies [22,23]. While these approaches show promise, they are often tested in scenarios with limited traffic complexity or without considering environmental uncertainty.

In contrast to prior work, this study integrates multi-agent highway maneuvers with adverse weather-induced uncertainty in a unified evaluation framework, providing a more comprehensive assessment of decision-making robustness and safety. By leveraging a Duel-DDPG-based architecture under challenging traffic and environmental conditions, the proposed approach addresses a gap in the literature where complex maneuvers and weather uncertainty are rarely considered jointly.

This study contributes two main innovations to enhance the safety and efficiency of highway automated driving under realistic conditions:

- Development of a robust and efficient decision-making policy for executing highway driving maneuvers, including lane keeping and double lane changing, using the Duel-DDPG algorithm to ensure safe and responsive vehicle behavior.

- Integration of realistic traffic conditions within the IPG Carmaker simulation platform, enabling comprehensive testing of lane keeping and lane changing maneuvers under diverse, high-fidelity driving traffic and uncertainty environments.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the vehicle dynamics modeling, and the application of the Duel-DDPG method for making decisions. Section 3 presents an evaluation of the simulation results based on the proposed strategy, while Section 4 concludes the study strategy.

2. Methods

This section describes the highway driving test environment, featuring the autonomous ego vehicle (AEV) and surrounding traffic participants. Moreover, it explains the AEV dynamics and introduces the benchmark models employed for maneuvering vehicles within the IPG CarMaker simulation platform. The DRL method integrates Reinforcement Learning (RL) with Deep Learning to effectively manage complicated, multidimensional state and action spaces In RL, an agent is trained to engage with a scenario via observing its current state (s), performing actions (a), receiving rewards (r), and moving to subsequent states (s’), all aimed at maximizing the total accumulated reward. This process is represented as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) characterized by (S, A, R, T, γ) where γ, ranging from 0 to 1 (excluding 1), is the discount factor. In DRL, neural networks serve to approximate value functions and policies. There are three main categories of methods:

- Value-based methods, like the DQN algorithm, approximate the value of states or state-action pairs.

- Policy-based methods, such as REINFORCE and PPO algorithms, learn the policy directly.

- Actor-Critic methods, including DDPG and TD3, combine both approaches by employing two networks, including an actor network for policy decisions and a critic network for evaluating values.

2.1. Simulation Environment

This section describes the testing environment for the highway driving assessment, featuring the autonomous ego vehicle (AEV) and surrounding traffic participants. Additionally, it outlines the AEV dynamics and introduces the reference models applied in driving maneuvers within the IPG CarMaker simulation platform. The vehicle dynamics framework uttilized in this study is according to the professional multi-body IPG-CarMaker software version 11, as described in [24].

2.2. Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) Algorithm

Machine learning (ML), a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), focuses on improving computational algorithms through data-driven approaches. ML techniques are generally divided into three categories: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning (RL). In RL, an autonomous agent interacts with an environment and learns to accomplish tasks by aiming to maximize a reward function. When the agent takes favorable actions during its interactions, it receives positive feedback, while incorrect actions result in penalties or negative rewards. Supervised learning, in essence, relies on training with labeled examples provided by experts. However, because assigning precise labels to interactions is often challenging, this method is generally unsuitable for addressing interactive problem scenarios. Unsupervised learning focuses on uncovering hidden patterns or structures within unlabeled data. While this approach is valuable for identifying organization within collected datasets, it lacks the ability to optimize a reward function, which is the central goal of reinforcement learning (RL) [25]. Certain reinforcement learning (RL) tasks involve environments with an extremely large number of possible states and actions. In such cases, artificial neural networks (ANNs) are employed as function approximators, and this integration of ANNs into RL is referred to as deep reinforcement learning (DRL). RL applications are commonly formulated as Markov decision processes (MDPs), which serve as mathematical models for decision-making scenarios where outcomes depend both on probabilistic events and the agent’s choices. This framework is widely applied in RL as well as in operations research.

The fundamental elements that constitute a Markov decision process (MDP) are outlined below:

States (S): In an MDP, states denote the complete set of possible situations or conditions describing the environment. Depending on the specific problem, these states may be defined in either a discreet or continuous manner.

Actions (A): At every state within a Markov Decision Process (MDP), the decision-making entity has a set of possible actions to choose from. These actions correspond to the different options or decisions that can be executed at that particular state.

Transition Probabilities (P): The transition probabilities define the chances of moving from one state to another following a specific action. That is to say, they describe the probability distribution over possible subsequent states based on the current state–action pair.

Rewards (R): Each state–action pair is linked to a reward that reflects the direct gain or loss resulting from executing that action in the given state. These rewards can take positive values (benefits) or negative values (penalties) and could be defined in either a deterministic or probabilistic manner.

Policy (π): A policy specifies how states are mapped to actions, describing the strategy an agent follows when selecting actions at each state. In reinforcement learning, the goal of most algorithms is to determine an optimal policy that maximizes the expected total reward over time.

Value Function (Q): The value function represents the expected total reward that can be obtained by following a particular policy or by executing a particular action at a certain state. It serves as a measure for assessing the effectiveness of different policies or actions.

MDPs adhere to the Markov property, meaning that the next state depends only on the current state and action, rather than on the sequence of preceding states and actions. This property simplifies the representation and analysis of decision-making problems and enables the use of a range of solution methods, including dynamic programming, Monte Carlo approaches, and temporal-difference learning. Markov decision processes provide a structured framework for analyzing decision-making under uncertainty and are extensively applied in fields including autonomous systems, robotics, game theory, etc.

The anticipated discounted reward Rt at time step t can be expressed as:

Here, γ is the discount factor, ranging between 0 and 1. The parameter t represents a finite time step, depending on the problem context. The policy π(a∣s) defines the probability of selecting action a in state s. The function Vπ(s), known as the value function, signifies the expected return when following policy π starting from state s and is given by:

is an action-value function as follows:

The iterative Bellman equation is fulfilled:

Not all reinforcement learning problems can be represented as MDPs. In cases where the state S is only partially observable or cannot be directly measured from the environment, the problem can be expressed as a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP). One approach to address this is to augment current observations with past information or prior knowledge, effectively transforming the problem into an MDP. The primary goal of a reinforcement learning algorithm remains to learn a policy that maximizes the anticipated return. The Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm [24] is a reinforcement learning method that integrates aspects of both value-based and policy-based approaches. It is especially effective for tackling reinforcement learning problems involving continuous action spaces.

The DDPG employs an actor–critic architecture consisting of two primary networks:

Actor network is responsible for learning the policy function, which maps states to actions. Its goal is to optimize the expected reward by selecting actions directly according to the current state. Also, the Critic network is tasked with learning the value function, which estimates the anticipated cumulative reward of following a given policy. It serves to assess the quality of the actions selected by the actor network. Additionally, the DDPG is an off-policy algorithm, which means it learns from experiences stored in a replay buffer rather than strictly following the current policy. It is also model-free, requiring no prior knowledge of the environment’s dynamics. Unlike algorithms tailored for discrete action spaces, DDPG is specifically designed for continuous action spaces, making it suitable for a variety of applications, such as robotics and control tasks.

A mean-squared Bellman error (MSBE) is expressed as:

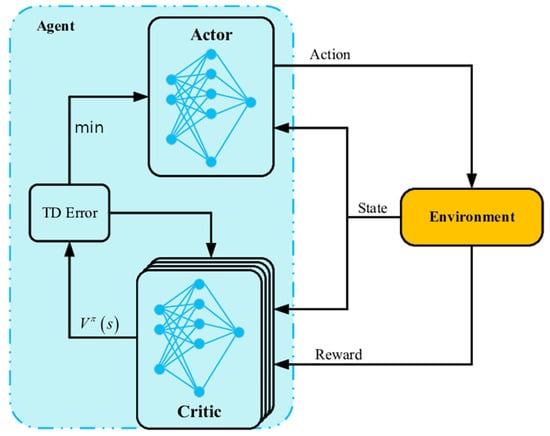

The DDPG algorithm integrates aspects of both policy gradient approach and Q-learning. The actor network is updated via policy gradient techniques to optimize the expected reward directly, whereas the critic network is trained using Q-learning to estimate the value of state–action pairs. Furthermore, the DDPG employs target networks to enhance training stability. These networks are copies of the main actor and critic networks and are updated more slowly than the primary networks. The algorithm also uses an experience replay memory for storing and sampling previous experiences (as illustrated in Figure 1), which helps decorrelate the data and improves sample efficiency.

Figure 1.

Duel-DDPG Network Architecture for Highway Decision-Making (Reprinted from Ref. [26]).

The reward function is defined as follows:

In this context, θ represents the steering angle, a denotes longitudinal acceleration, and the collision variable equals 1 when drelative = 0, with M being a constant. Using this formulation, the agent is trained within a highway strategy to navigate and reach the highway exit. The Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, a deep reinforcement learning method, combines Q-learning with deep neural networks for approximating the best action-value function in continuous states. DQN learns to directly map states to actions from raw sensory data, often images, which allows it to manage high-dimensional inputs. The algorithm employs experience replay and a target network to stabilize training and reduce over fitting: experiences are stored in a replay buffer and randomly sampled, while the target network is periodically updated with the weights from the main Q-network. Through iterative gradient descent updates, the DQN minimizes the temporal-difference error between predicted and target Q-values, eventually learning a policy that optimizes total rewards within the environment.

The Duel-DDPG algorithm is an off-policy actor–critic approach developed for continuous action spaces. It employs an actor network, μ(s∣θμ), to select actions, and a critic network, Q(s,a∣θQ), to assess the value of state–action pairs.

The critic is trained using the Bellman equation as follows:

where the target value is:

and Q’, μ’ are target networks. The actor network is updated by optimizing the expected value of the return. Q-value:

L (θQ) = E s, a, r, s’ [(Q(s, a| θQ) − y)2]

y = r + γ Q’ (s’, μ ’(s’) | θQ’)

∇θμ J ≈ Es [∇a Q (s, a| θQ) ∇θμ μ (s | θμ)]

The Duel-DDPG algorithm incorporates the dueling network architecture into the critic component of DDPG. Rather than directly estimating the Q-value function Q(s,a), the critic network is designed to separately estimate the state-value function V(s) and the advantage function A(s,a).

The critic network then computes as following equation:

By decomposing the Q-value into separate components, Duel-DDPG improves generalization across different actions in continuous control tasks and helps stabilize the learning process, especially in settings with sparse or noisy rewards.

The Duel-DDPG algorithm framework is defined as follows (Algorithm 1):

| Algorithm 1. Duel-DDPG algorithm framework |

| Initial Q function parameters φ and policy parameters θ |

| Here is a paraphrased version of that line: |

| Initialize the target network parameters to match |

| those of the primary network.

|

| Agent: Observe state (s) and select action (a) Execute a in the environment Observe reward (r) and next state () Store B (s, a, r, (D). Randomly sample batch of transitions, B (s, a, r, ) from D Compute targets: |

| Where |

| Update Q—function by one step of gradient descent

|

| Where |

| Update policy by one step of gradient ascent |

| Update target networks with |

| End |

The Duel-DDPG algorithm strategy to make decisions for autonomous vehicles are as follows:

The parameters of the neural networks for the Q-function Q (s, a) and the policy function are initialized. Then, the parameters of the main neural network are set equal to those of the target neural network in both the actor and critic components of the Duel-DDPG algorithm. At this stage, the agent—an autonomous vehicle—begins decision-making within its environment. The agent observes the initial state, makes a decision, and determines an action. The chosen action is executed within the environment, after which the agent receives a reward corresponding to the executed action and transitions to a new state. The tuple consisting of the initial state, executed action, received reward, and subsequent state is stored in the replay buffer. The stored experiences in the buffer are then used to compute the ideal and target values. Based on the derived equations, the ideal value is calculated. Using gradient descent and minimizing the defined loss function, the critic component of the Duel-DDPG algorithm is updated to maximize the Q-function. In parallel, gradient methods are applied to update the actor component so that the policy adopted by the autonomous vehicle is optimized. Then, the weights of the target network are updated based on those of the main network. This occurs in both the critic and actor parts of the Duel-DDPG algorithm, as described by the corresponding update equations. The innovation in the Duel-DDPG algorithm is particularly evident in the newly introduced instructions and equations, which enhance learning performance and allow the algorithm behavior to more closely resemble human decision-making. Finally, the details of the agent state, action, and the designed reward function used to provide feedback for each action will be explained.

2.3. State

In RL algorithms, the state refers to the condition or situation that the agent (the autonomous vehicle) encounters at each moment. In this research, the agent’s states are defined as the speed of the autonomous vehicle (Vego and its relative distance (drel) to surrounding vehicles.

States: {Vego, drel}

2.4. Action

In RL algorithms, an action is any movement or decision taken by the agent (the autonomous vehicle) within its environment. In this study, the agent actions are the steering wheel angle (θ) and the longitudinal acceleration (ax) of the autonomous vehicle. The operational ranges for these actions are as follows:

Θ = [−0.26, 0.26] rad and ax = [−3, 2] m/s2

2.5. Reward Function

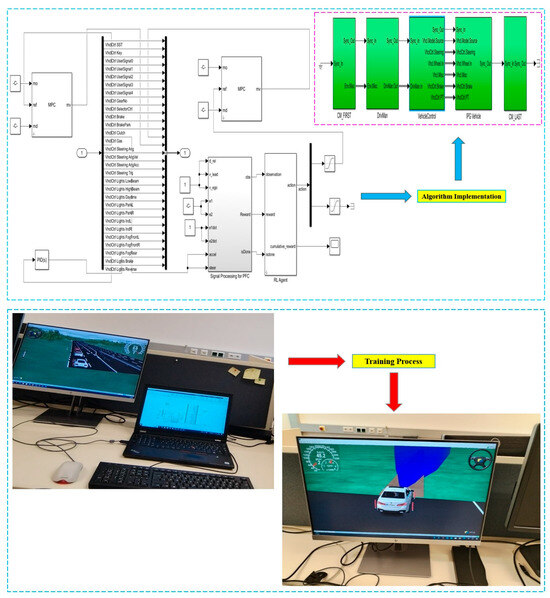

The reward function determines the feedback for every action taken by the agent (with hyper-parameters as Table 1) in a given state. If the action leads to maximizing the Q-function, a positive reward is assigned; otherwise, a negative reward is given. In this study, the reward function is defined as (6). According to the first term in Equation (6), the steering angle is considered an action in the autonomous vehicle’s decision-making system. The inclusion of the steering angle in the reward function aims to prevent abrupt and severe steering changes, which can lead to vehicle instability and reduced safety. Therefore, penalizing the steering angle promotes more stable and natural steering behavior. Conversely, excluding the steering angle from the reward function results in increased fluctuations and abrupt maneuvers, since the system would no longer penalize drastic steering changes that ultimately cause collisions, as represented in the third term of Equation (6). Furthermore, in this thesis, lateral and side distances are not explicitly included as independent parameters in the reward function. However, these factors are implicitly controlled through the vehicle lane position and its distance to surrounding obstacles, which are detected by simulated sensors. According to the second term in Equation (6), the effect of the vehicle longitudinal speed is controlled via longitudinal acceleration. Longitudinal acceleration directly influences speed changes, and its inclusion aims to enable smoother and safer control of the vehicle in highway environments. Thus, the direct use of longitudinal acceleration in the reward function provides indirect control of longitudinal speed and direct control of acceleration through the second term of Equation (6). By applying Equation (6) and utilizing the newly proposed Duel-DDPG algorithm in the CarMaker simulator, as shown in Figure 2, the agent -autonomous vehicle- has been trained and learned accordingly.

Table 1.

Hyper parameters.

Figure 2.

Duel DDPG Algorithm Training Process.

3. Results and Discussion

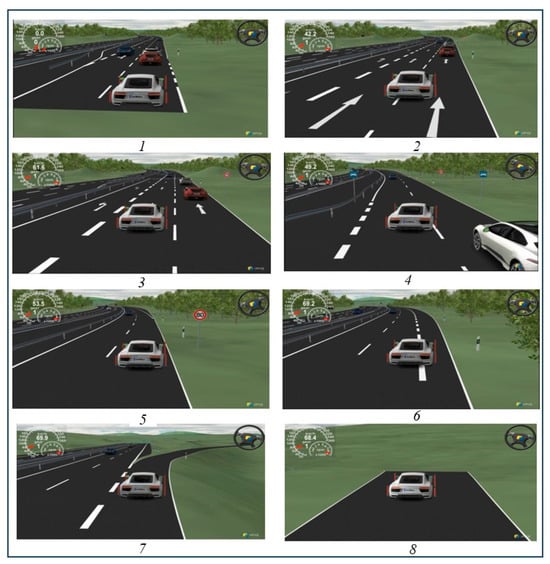

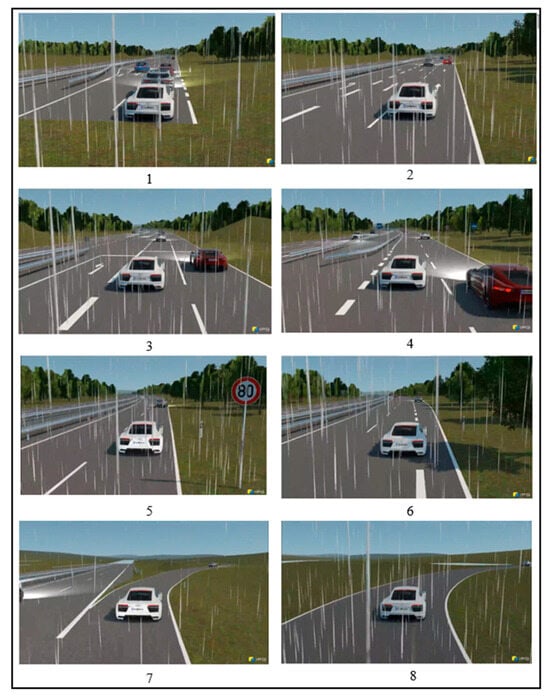

In this scenario, the autonomous vehicle performs maneuvers such as lane changes, and double lane changes within a complex highway environment, aiming to successfully navigate highway exits. The objective is to evaluate the capability of the Duel-DDPG algorithm in safely and efficiently overcoming dynamic obstacles and executing maneuvers to exit the highway, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simulated Scenario in the IPG Carmaker Simulator. (1: preparing for lane change, 2: executing lane change, 3: preparing for double lane change, 4: executing double lane change, 5: executing double lane change, 6: executing double lane change, 7: executing lane keeping, 8: executing lane keeping).

As illustrated in Figure 3, the scenario has been implemented in the IPG-Carmaker simulator. In this scenario, the vehicle is traveling at a speed of 70 k/h and, given the relatively complex traffic environment it encounters, it navigates through the traffic by executing maneuvers such as lane changes, and double lane changes. Ultimately, the ego vehicle safely exits the highway. In this scenario, the Duel-DDPG algorithm successfully performed lane changes, double lane changes, and lane-keeping maneuvers efficiently and safely, without any collisions with other vehicles, ultimately exiting the highway. Afterward, an analysis of the lateral acceleration, longitudinal velocity, and yaw rate graphs of the autonomous vehicle equipped with both the Duel-DDPG and the DDPG algorithms will be presented.

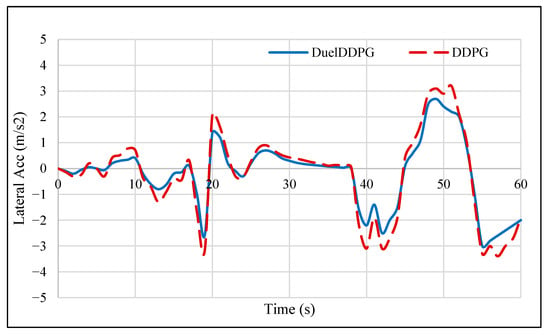

As shown in Figure 4, in this complex scenario, the average lateral acceleration under the Duel-DDPG algorithm was 0.4 m/s2, compared to 0.9 m/s2 for the DDPG algorithm. Additionally, the standard deviation of lateral acceleration was lower for Duel-DDPG, indicating superior vehicle control during maneuvers. Actually, the reduction in lateral acceleration achieved by the Duel-DDPG algorithm has had a direct positive impact on vehicle stability and safety. This improvement, especially evident during lane changes and sudden maneuvers, has minimized unwanted deviations and enhanced lateral control performance. Furthermore, the Duel critic network within the Duel-DDPG algorithm, by decomposing the Q-value function, has been able to select better policies for controlling the vehicle’s lateral movements. This optimization has resulted in reduced lateral acceleration, thereby improving control precision and vehicle handling. The results demonstrate that in the second modeled scenario, the Duel-DDPG algorithm, through more precise control and lower lateral acceleration, guided the ego vehicle with smoother and more stable movements. This reflects the algorithm superior capability to handle complex road conditions. In other words, the Duel-DDPG reduction in lateral acceleration facilitates more accurate and stable vehicle motion. Beyond enhancing safety, this improvement reduces oscillations and undesired lateral motions, thereby increasing passenger comfort an effect particularly significant under challenging road conditions.

Figure 4.

Lateral Acceleration of the Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) Algorithms.

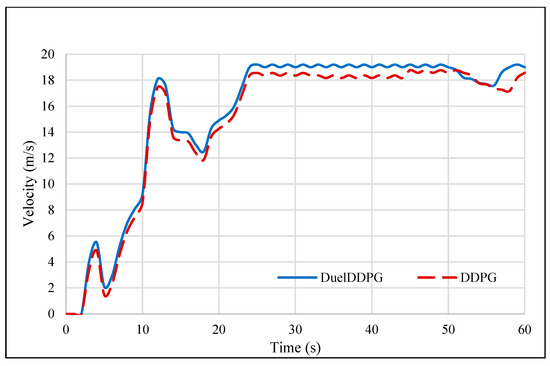

As illustrated in Figure 5, the autonomous vehicle equipped with the Duel-DDPG algorithm, adapting to the heavy traffic environment it encounters, travels at the maximum set speed of 19.4 m/s (70 k/h) in a traffic-free setting. It completes this scenario more efficiently and effectively compared to the DDPG algorithm, ultimately exiting the highway successfully.

Figure 5.

Longitudinal Velocity of the Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) Algorithms.

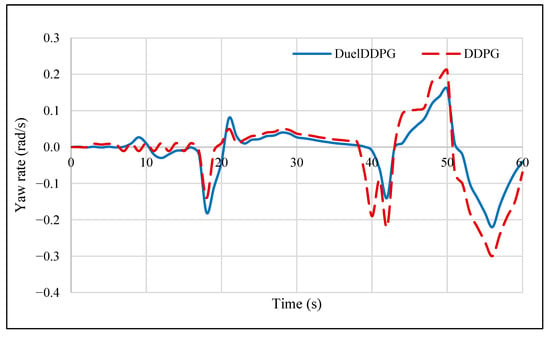

As shown in Figure 6, the Duel-DDPG algorithm effectively controls the yaw rate in the heavy traffic scenario. This demonstrates the superiority and capability of the algorithm in maintaining stability and executing precise maneuvers. Additionally, it reflects better alignment of decision-making with actual road conditions and vehicle dynamics.

Figure 6.

Yaw rate of the Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) Algorithms.

Simulation results indicate that the average longitudinal acceleration under the Duel-DDPG algorithm is 1.1 m/s2, compared to 0.7 m/s2 for the DDPG algorithm. Furthermore, the standard deviation of acceleration in Duel-DDPG is lower, indicating greater system stability. In this scenario, the Duel-DDPG method reacts more quickly than the DDPG algorithm and provides more appropriate longitudinal acceleration. This allows the autonomous vehicle to reach and safely exit the highway at a higher speed. Moreover, the duel architecture within the Duel-DDPG algorithm enhances decision-making for longitudinal acceleration by decomposing the value function into state value and advantage components. This enables the algorithm to select better policies, resulting in increased acceleration and reduced time to reach desired speeds under this scenario. Also, the results show that despite the complex traffic, Duel-DDPG exhibits less fluctuation in longitudinal acceleration due to its duel critic network. This increased stability of the ego allows vehicle to operate more safely in high-risk situations and critical decision points. The improvement in longitudinal acceleration under Duel-DDPG, compared to DDPG, indicates that this algorithm performs better not only in complex decision-making but also in key operational parameters such as longitudinal acceleration even in heavy traffic conditions. Based on the analysis, the autonomous vehicle equipped with Duel-DDPG successfully reduces its speed in the presence of heavy traffic ahead, continues lane-keeping maneuvers, and when encountering a clear lane, adjusts its speed to the maximum set value of 70 km/h. Ultimately, it exits the highway safely and without collision while completing the maneuver. Furthermore, in this scenario, the Duel-DDPG algorithm effectively regulates speed despite the complex traffic environment, performing lane changes, and double lane changes maneuvers. When encountering a free lane, it adjusts speed to the maximum limit of 70 k/h, and safely exits the highway and successfully completing the maneuver.

Considering Uncertainty

In this scenario, an autonomous vehicle performs maneuvers such as lane changes, double lane changes, and lane keeping within a highway environment characterized by moderately heavy traffic, with the objective of exiting the highway. The aim is to evaluate the capability of the Duel-DDPG algorithm in safely and efficiently navigating through moving obstacles in relatively dense traffic while executing maneuvers to successfully exit the highway (as illustrated in Figure 6).

Uncertainty is a crucial factor in real-world driving and can significantly impact vehicle decision-making and control. Factors contributing to uncertainty include road conditions such as rainfall, changes in vehicle weight due to additional load, and similar circumstances. In this study, to more precisely evaluate the performance of the Duel-DDPG algorithm in decision-making, uncertainty conditions have been incorporated into the Carmaker simulator as outlined below unpredictable environment. To account for these uncertainties, environment conditions in the Carmaker simulator have been configured as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Environment Condition Parameters in the Carmaker Simulator.

In addition to the weather conditions listed in the above table, a 10% uncertainty in vehicle weight has also been incorporated into the simulations.

This research presents a controlled simulation environment with simplified abstracted weather and sensors. This enables analysis of the approach and provisional evidence to be evaluated reproducibly. Though the models do not portray all the uncertainties of the real world, such as extreme noise, interference, and abrupt changes to the environment, focus can be placed on the behavior of the decision maker with well-defined parameters. Considerations of safety, through reward shaping, aims the learning towards the desired behaviors that incorporate safety and provides a method of policy guidance through the learning approach. In addition, state representation, as well as reward mechanism of the DRL framework, is geared towards learning efficiency and performance. This enhances the ability to learn and effectively train the policy, while state representation and complex driving scenarios highlight the areas that future extensions may aim towards.

As shown in Figure 7, the scenario has been implemented in the Carmaker simulator. In this scenario, the vehicle travels at a speed of 70 k/h and, faced with a relatively complex traffic environment, performs maneuvers such as lane changes, double lane changes, and lane keeping to navigate through traffic in rainy road conditions, ultimately approaching and exiting the highway. In this scenario, the Duel-DDPG algorithm successfully executed lane changes, double lane changes, and lane keeping maneuvers safely and efficiently without collisions, despite the rainy weather and a 10% uncertainty in the autonomous vehicle weight, ultimately exiting the highway. Subsequent, an analysis of the longitudinal acceleration and velocity profiles of the autonomous vehicle under the Duel-DDPG algorithm in the presence of uncertainty is presented, and these results are compared with those under normal conditions.

Figure 7.

Lane keeping and lane changing maneuvers performed by the autonomous vehicle in a highway environment under uncertainty conditions. (1: preparing for lane change, 2: executing lane change, 3: preparing for double lane change, 4: executing double lane change, 5: executing double lane change, 6: executing double lane change, 7: executing lane keeping, 8: executing lane keeping).

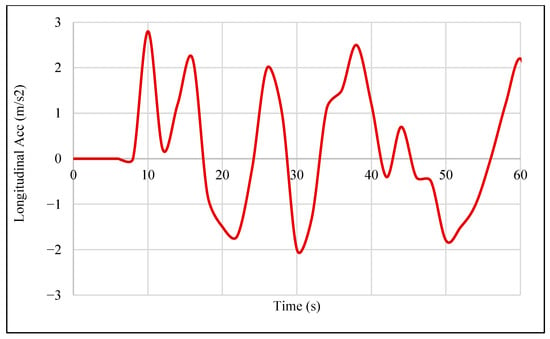

Figure 8 illustrates the longitudinal acceleration of the autonomous vehicle under uncertainty which represents a complex environment. Subsequently, the longitudinal acceleration during decision-making by the Duel-DDPG algorithm in the second scenario is analyzed and compared under normal and rainy conditions with uncertainty. Table 3 displays a comparison of the longitudinal acceleration of the Duel-DDPG algorithm in the second scenario under normal and rainy conditions, considering the presence of uncertainty.

Figure 8.

Longitudinal acceleration of the Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) algorithm under uncertainty conditions.

Table 3.

Comparison of longitudinal acceleration in the Scenario under normal and uncertainty (rainy) conditions.

As shown in Figure 8, the range of longitudinal acceleration is slightly narrower under rainy conditions. This indicates that the autonomous vehicle, even in complex traffic and rainy weather, tends to accelerate without its performance being significantly affected by slipping or reduced road friction. This reflects the vehicle adequate control freedom for both braking and acceleration in rainy conditions. In other words, the reduced acceleration range under rainy conditions in the simulated Scenario suggests an increased sensitivity of the autonomous vehicle to sudden speed changes. Furthermore, as presented in Table 2, the mean acceleration under normal conditions is somewhat higher than that in rainy conditions, indicating limitations on acceleration during rain in the complex scenario. The standard deviation in rainy conditions is close to that of normal conditions, demonstrating that the autonomous vehicle equipped with the Duel-DDPG algorithm maintains acceptable stability in acceleration changes under both normal and rainy scenarios.

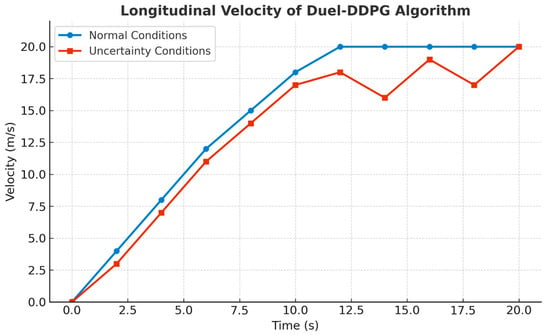

As shown in Figure 9, the longitudinal velocity profile of the autonomous vehicle exhibits oscillatory behavior under rainy weather conditions compared to its relatively smooth trajectory under normal dry conditions. These oscillations can primarily be attributed to transient variations in road surface characteristics, such as the presence of small puddles, localized water films, or micro-slippery patches that intermittently alter the effective tire–road friction coefficient. When the vehicle wheels encounter such surface irregularities, minor disturbances in traction arise, causing slight but abrupt changes in the available longitudinal force. Due to this topic, the vehicle decision-making system engages in continuous monitoring and corrective action to maintain stability and safety. Specifically, the Duel-DDPG algorithm—serving as the core of the decision-making architecture—leverages its reinforcement learning framework to anticipate upcoming environmental conditions based on recent sensor inputs and accumulated experience. It evaluates the likelihood of reduced friction along the predicted driving path and proactively adjusts the throttle and brake control signals. This results in rapid modulation of vehicle acceleration, producing short-term fluctuations in velocity as the system strives to prevent loss of traction and sustain longitudinal control. While these fluctuations may appear as undesirable oscillations from a superficial perspective, they actually reflect the adaptive nature of the control policy. The Duel-DDPG agent continuously updates its internal value estimations of different driving actions under varying surface conditions, enabling it to dynamically balance the trade-off between maintaining speed stability and avoiding potential skidding or slippage. Such proactive adjustments are particularly crucial in adverse weather, where the margin for error is significantly reduced and rapid reaction times are essential to ensure safe operation. Furthermore, the ability of the Duel-DDPG algorithm to respond quickly to environmental perturbations underscores its robustness and generalization capability. By dynamically adapting its control strategy to the reduced and uncertain friction environment, the system demonstrates resilience and maintains operational safety without requiring explicit rule-based programming for every possible condition. Also, the observed velocity oscillations serve as empirical evidence of the algorithm capability to perceive, interpret, and react to complex real-world disturbances—thereby showcasing the intelligence, flexibility, and reliability of the decision-making framework in challenging driving scenarios.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal velocity of the Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (Duel-DDPG) algorithm under normal and uncertainty conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study focuses on the uncertainty that DRL Highway models may face when selecting actions in the presence of adverse driving conditions. The author proposes for the first time an evaluation framework that integrates multiple traffic maneuvers (lane-change and double lane-change) and both adverse weather (reduced visibility and brake distance increment due to rain) conditions. The author argues that this framework provides a more comprehensive examination of joint traffic and environmental uncertainty complexity than the frameworks present in the relevant literature. Within this framework, a Duel-DDPG-based control architecture is assessed and exhibits, across a range of traffic densities and weather conditions, improved convergence, robustness, and safety compared to traditional DDPG methods. These findings suggest that the proposed framework is effective in evaluating safety-critical autonomous driving decision-making. The work is framed around controlled simulation-based experiments in the IPG CarMaker environment, which systematically and repetitively evaluates decision-making performance in various traffic and weather scenarios. While real-world deployment is not addressed in this work, the computational requirements and simulation-based design provide a practical foundation for future extensions. Ongoing and future research will focus on hardware-in-the-loop experimentation and validation using real-world highway datasets collected under varying environmental conditions to further assess applicability beyond simulation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.R.; Software, A.R. and A.E.; Validation, A.R. and S.A.; Formal analysis, S.A.; Investigation, A.R.; Resources, A.R.; Data curation, S.A. and A.E.; Writing—original draft, A.R.; Writing—review and editing, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DuelDDPG | Duel Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

References

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Shammah, S.; Shashua, A. Safe, Multi-Agent, Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.03295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, B.R.; Sobh, I.; Talpaert, V.; Mannion, P.; Al Sallab, A.A.; Yogamani, S.; Perez, P. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 4909–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL Sallab, A.; Abdou, M.; Perot, E.; Yogamani, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning framework for Autonomous Driving. Electron. Imaging 2017, 29, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuefler, A.; Morton, J.; Wheeler, T.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Imitating Driver Behavior with Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2017; pp. 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh, D.; Sastry, S.S.; Seshia, S.A.; Dragan, A.D. Planning for Autonomous Cars that Leverage Effects on Human Actions. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 18–22 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizehvandi, A.; Azadi, S.; Eichberger, A. Decision-Making Policy for Autonomous Vehicles on Highways Using Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) Method. Automation 2024, 5, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, J.; Lv, N.; Li, S. An Intelligent Path Planning Scheme of Autonomous Vehicles Platoon Using Deep Reinforcement Learning on Network Edge. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 99059–99069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Coskun, S.; Pang, H.; Cui, Y.; Xi, J. Energy management strategies for hybrid electric vehicles: Review, classification, comparison, and outlook. Energies 2020, 13, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Schneider, J.; Dolan, J. Behavior Planning at Urban Intersections through Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.04697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizehvandi, A.; Azadi, S.; Eichberger, A. Performance Comparison of Duel-DDPG and DDPG Algorithms in the Decision-Making Phase of Autonomous Vehicles. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2025, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizehvandi, A.; Azadi, S. Design of a Path-Following Controller for Autonomous Vehicles Using an Optimized Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Method. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2024, 21, 11682–11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AVL. Global Vehicle Benchmarking and Technology Scouting. Available online: https://www.avl.com/en-us/engineering/vehicle-engineering/vehicle-development/global-vehicle-benchmarking-and-technology-scouting (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizehvandi, A.; Azadi, S. Developing a controller for an adaptive cruise control (ACC) system: Utilizing deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approach. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transport. 2024, 125, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Shammah, S.; Shashua, A. On a formal model of safe and scalable self-driving cars. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.06374. [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Shou, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1786–1791. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.; Fernández, F. A comprehensive survey on safe reinforcement learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2025, 16, 1437–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Alshiekh, M.; Bloem, R.; Ehlers, R.; Könighofer, B.; Niekum, S.; Puggelli, A. Safe reinforcement learning via shielding. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 2669–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Hawke, J.; Janz, D.; Mazur, P.; Reda, D.; Allen, J.-M.; Lam, V.-D.; Bewley, A.; Shah, A. Learning to Drive in a Day. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 8248–8254. [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht, M.; Stone, P. Deep Recurrent Q-Learning for Partially Observable MDPs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Fall Symposium on Sequential Decision Making for Intelligent Agents (AAAI-SDMIA15), Arlington, VA, USA, 12–14 November 2015; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Igl, M.; Zintgraf, L.; Le, T.A.; Wood, F.; Whiteson, S. Deep variational reinforcement learning for POMDPs. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rizehvandi, A.; Azadi, S.; Eichberger, A. Enhancing Highway Driving: High Automated Vehicle Decision Making in a Complex Multi-Body Simulation Environment. Modelling 2024, 5, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qu, D.; Song, H.; Dai, S. A Hierarchical Framework of Decision Making and Trajectory Tracking Control for Autonomous Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H.T.H.; Hoan, T.N.K.; Thanh, P.D.; Koo, I. Hybrid NOMA/OMA-Based Dynamic Power Allocation Scheme Using Deep Reinforcement Learning in 5G Networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.