Abstract

The electrification of transport is vital to achieving global climate targets, with electric vehicles (EVs) positioned as a sustainable alternative to fossil fuel–based mobility. However, the scalability of EV adoption hinges on the accessibility, reliability, and user experience of public charging infrastructure. As China leads the world in EV adoption, Shanghai represents a critical case for evaluating user satisfaction in a megacity context where infrastructure density, urban planning, and consumer behavior intersect. Despite significant investments in expanding charging facilities, limited empirical research has examined how users perceive and interact with Shanghai’s public EV charging network. This study addresses that gap through a quantitative, user-centered analysis of responses from 197 EV users using the QUESS-PAC framework (Quantitative User Experience Survey Strategy for Public EV Charging Analysis in Cities). A structured questionnaire assessed satisfaction across multiple dimensions: infrastructure layout, convenience, pricing, ease of use, safety, and lighting. Using SPSS (v28), descriptive analysis and multiple regression were conducted to identify key determinants of satisfaction. The findings indicate low overall user satisfaction, with critical weaknesses in location planning, cost transparency, and interface usability. Regression analysis highlights four significant predictors of satisfaction—layout, ease of use, pricing, and lighting—with charging price emerging as the most influential factor. This study’s unique contribution lies in the development and application of the QUESS-PAC framework, which integrates quantitative UX metrics with behavioral and spatial dimensions to provide a more systematic assessment than prior descriptive studies. It emphasizes the need for integrated planning that combines spatial equity, service design, and behavioral insights. Based on the analysis, policy recommendations are proposed to enhance satisfaction and encourage adoption. These findings offer transferable insights for global cities navigating the electrification of transport.

1. Introduction

The global climate agenda has intensified since the Paris Agreement’s inception, particularly its central goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels [1]. Achieving this threshold necessitates urgent and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—most of which originate from fossil fuel combustion. The transportation sector is responsible for around 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions, while it contributed approximately 27% within the European Union in 2023 [2]. As car ownership rapidly approaches 1.5 billion vehicles globally [3], the environmental burden posed by internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles grows exponentially, worsening air quality and depleting finite petroleum reserves [4].

This environmental urgency is compounded by rising energy insecurity triggered by post-pandemic demand recovery and geopolitical instability [1,5]. Against this dual backdrop of climate pressure and energy crisis, electrification of transportation has emerged as a strategic pathway toward sustainability and energy resilience [6]. Electric vehicles (EVs) offer zero tailpipe emissions, reduced lifecycle carbon intensity when coupled with low-carbon power grids, and lower noise and particulate pollution. However, the pace of EV adoption depends not only on technology and policy but also on accessible, reliable, and user-centric charging infrastructure [7].

China currently leads the global EV transition, accounting for more than 40% of global EV sales in 2020 [8]. Within China, Shanghai—one of the most densely populated and technologically advanced megacities—has become a focal point for large-scale EV deployment. Despite strong policy incentives and rapid deployment of charging stations, a significant mismatch persists between infrastructure growth and user satisfaction, particularly in urban environments [9]. Although several studies have examined EV infrastructure in major Chinese cities, few have explored user experience-based evaluations that systematically quantify satisfaction and behavioral responses to public charging infrastructure in Shanghai [10].

This study addresses this critical gap by investigating the user experience of public EV charging infrastructure in Shanghai through a structured, medium-sample survey. Specifically, it aims to assess the satisfaction levels and behavioral preferences of EV users, identify key infrastructural deficiencies, and propose evidence-based recommendations for optimizing future charging infrastructure planning. The underlying premise is that understanding the real-world needs and frustrations of EV users can enhance both service delivery and policy design ultimately contributing to accelerated and equitable EV adoption.

To achieve this goal, a questionnaire was developed and distributed to Shanghai EV users, focusing on usage behavior, satisfaction with key infrastructure attributes. The data was then analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression modeling to determine the most influential factors affecting user satisfaction. The findings not only inform urban planning and infrastructure development in Shanghai, but also provide transferable insights for other high-density urban markets undergoing similar transitions to sustainable mobility. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature. The research methodology is detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents the experimental results, followed by an in-depth discussion in Section 5. Comparative analysis with existing studies is detailed in Section 6. Section 7 presents the policy recommendations. Finally, Section 8 concludes this study and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The global electric vehicle (EV) market is expanding rapidly, with sales surpassing 14 million in 2023—nearly 18% of all new car sales worldwide. Most EV sales are in just three places—China, Europe, and the United States—which together make up about 90% of the market; China alone is over 60%. If current policies continue, the total number of EVs worldwide could be more than 250 million by 2030 [11].

China’s electric vehicle (EV) revolution has been significantly influenced by an aggressive policy framework, particularly since 2021, national and regional policies enhancing financial subsidies, technological innovation, and infrastructure development [12]. These efforts have translated into a remarkable surge in EV adoption, with battery electric vehicles (BEVs) representing over 37% of total vehicle sales in China as of 2023 [13]. This progress aligns with the nation’s dual carbon targets, aiming for carbon peak by 2030 and neutrality by 2060 [14].

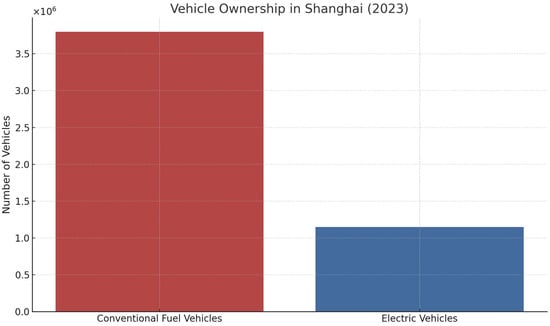

Shanghai has played a pioneering role in this trajectory, leveraging a combination of policy support, pilot programs, and urban innovation. As shown in Figure 1, In 2023, Shanghai had approximately 1.15 million registered electric vehicles, growing at a rate of over 6% year-on-year, compared to 3.8 million internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles [15]. While this is a significant milestone, the dominance of ICEs still presents urban mobility and sustainability challenges. Understanding and addressing user-side constraints remains crucial to accelerating EV uptake.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Conventional vs. Electric Vehicles in Shanghai (2023).

2.1. Public Charging Infrastructure in China and Shanghai

China leads globally in EV charging infrastructure, having deployed over 8.6 million charging units by the end of 2023—a 65% increase from the previous year [16]. Yet, the city’s charger-to-vehicle ratio of 1:2.4, though higher than many emerging markets, remains below global benchmarks. For example, Norway maintains approximately 1:1 charger-to-vehicle ratio, while the EU recommends a maximum 1:10 charger-to-vehicle ratio [11,17]. These comparisons suggest that despite steady growth, the Shanghai’s network remains suboptimal in suburban areas where charger accessibility and redundancy are critical for reliable operation.

The imbalance between vehicle growth and infrastructure provisioning is a major bottleneck, necessitating strategic planning that considers spatial, demographic, and behavioral dimensions.

2.2. User Experience as a Critical Success Factor

A growing body of evidence underscores the pivotal role of user experience (UX) in EV infrastructure adoption. Studies consistently show that limited charger availability, poor signage, slow speeds, and unreliable access significantly deter EV use [18].

Recent UX studies from North America and Europe emphasize that satisfaction with public charging networks depends strongly on reliability, ease of access, intuitive payment systems, and perceived safety [19,20]. Similarly, European assessments show that station design, lighting, and clear signage significantly shape driver comfort and trust [19].

2.3. Factors Influencing Charging Infrastructure Satisfaction

Recent empirical investigations have outlined a constellation of interlinked variables affecting user satisfaction with EV infrastructure. The spatial distribution of charging stations is urban planning that clusters chargers in business centers, transport hubs, and residential zones improves convenience and utilization rates [21]. High footfall areas, such as shopping malls and transit interchanges, have been found to be ideal placement zones, particularly when combined with smart queuing systems and multi-vehicle access.

Equally critical are factors related to safety and comfort. Recent literature reveal that inadequate lighting, security concerns, and isolation during night-time charging contribute to hesitancy—especially among female users. Therefore, integrating CCTV, 24 h lighting, and locating stations near public activity centers has been recommended as best practice [10,22,23,24,25].

Technological usability also affects satisfaction. Charging interfaces should be simple, multilingual, and integrated with mobile platforms to allow for payment flexibility and real-time updates. Rapid-charging capabilities further enhance user perception, particularly for commercial and taxi fleets. Demographic profiling adds further nuance. Younger drivers, frequent commuters, and tech-savvy consumers report higher satisfaction with public infrastructure than older or rural users, who often prefer private or workplace charging. Additionally, income level affects pricing sensitivity—suggesting the need for tiered pricing models and off-peak discounts to ensure equity in access.

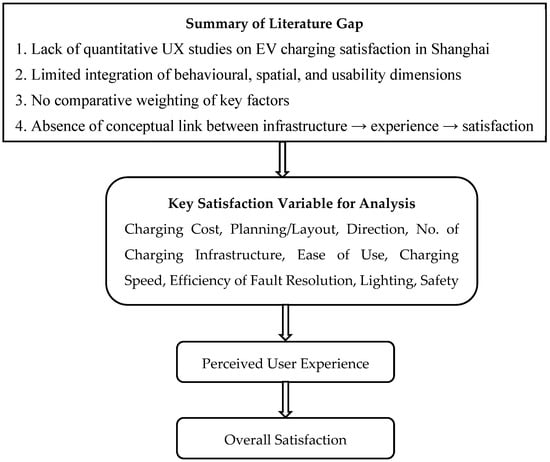

Despite growing interest, there remains a dearth of quantitative UX studies focused on Shanghai, especially those incorporating behavioral metrics and multivariate satisfaction models. This study addresses that gap, offering a localized, data-driven analysis of Shanghai EV users’ infrastructure experience while providing insights generalizable to other rapidly urbanizing regions. Figure 2 shows the summary of literature gap and variable tested in this analysis.

Figure 2.

Summary of literature gap and variable tested in this analysis.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts the QUESS-PAC framework (Quantitative User Experience Survey Strategy for Public EV Charging Analysis in Cities), a structured and replicable methodology for evaluating user satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure as shown in Table 1. The framework is rooted in positivist philosophy and follows a deductive, mono-method quantitative design. The research design is based on the multi-layered framework proposed by [26], widely known as the “research onion,” which allows for systematic consideration of research philosophy, approach, strategy, and data analysis procedures. This section details the methodological framework adopted, including philosophical positioning, sampling procedures, data collection, analysis strategies, ethical safeguards, and research limitations. It integrates theoretical grounding, instrument design, ethical safeguards, and statistical analysis in a coherent research pipeline. The following subsections outline each stage of the methodological process.

3.1. Research Framework Design

This study is epistemologically positioned within the positivist paradigm, which assumes an objective and measurable reality independent of the researcher [27]. Accordingly, a deductive research approach is adopted to test hypotheses derived from prior literature on EV user behaviour and satisfaction. The research strategy is cross-sectional, relying on a one-time survey distributed online. A mono-method quantitative design supports hypothesis testing and generalizability, aligning with the empirical orientation of the research question [26].

3.2. Instrument Development

A structured questionnaire was designed and organized into four key sections:

- Demographic Information;

- Usage Patterns;

- Satisfaction with Infrastructure Attributes (e.g., cost, layout, speed, signage);

- Perceptions of Safety and Value-added Services.

Each item was measured using a five-point Likert scale, widely recognized for capturing attitudinal nuances. To enhance content validity, the questionnaire underwent a pilot test with 15 EV users, and feedback was used to refine question clarity, sequencing, and relevance.

3.3. Conceptualization of User Satisfaction

User satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure is conceptualized as the extent to which users perceive the service environment and technology as meeting their expectations. This conceptualization draws on established frameworks from service quality (SERVQUAL) and technology acceptance (TAM) literature, emphasizing multidimensional influences on user perceptions [28,29].

In this study, satisfaction is examined as a composite construct associated with several interrelated factors:

- Infrastructure layout and accessibility: The spatial distribution and proximity of charging stations relative to users’ daily travel and residential patterns.

- Cost and pricing transparency: Users’ perceptions of affordability, fairness, and clarity in charging fees.

- Safety and environmental reassurance: Features such as lighting, surveillance, and general security that contribute to comfort and perceived reliability.

- Service quality and usability: Operational efficiency, interface clarity, payment convenience, and responsiveness to malfunctions.

By grounding this study in this framework, satisfaction is treated as a reflective measure of user experience across service quality, technological usability, and environmental context, providing a structured basis for empirical investigation.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected over a two-week period (5–20 June 2024) via two widely used digital platforms in China:

- Questionnaire Star, the country’s largest online survey platform;

- WeChat, a social application with integrated distribution and targeting functions.

These platforms were selected to access digitally active EV users in Shanghai. It is acknowledged that this approach may introduce digital divide and self-selection biases, as individuals without regular internet access or lower engagement with digital media could be underrepresented. Therefore, the findings primarily reflect the perspectives of digitally active users and may not be fully generalizable to all EV users.

A total of 228 responses were collected. To ensure data quality, responses were screened using the following criteria:

- Completion time: surveys completed in under one minute were excluded;

- Straight-line answering: responses showing uniform answers across items were removed;

- Duplicated IP addresses: multiple submissions from the same IP were excluded;

- Location: only respondents reporting residence in Shanghai were retained.

After cleaning, 197 valid responses remained, corresponding to an effective response rate of 86%. Appendix A shows the robustness checking. Data cleaning and abnormal value detection is shown in Appendix B.

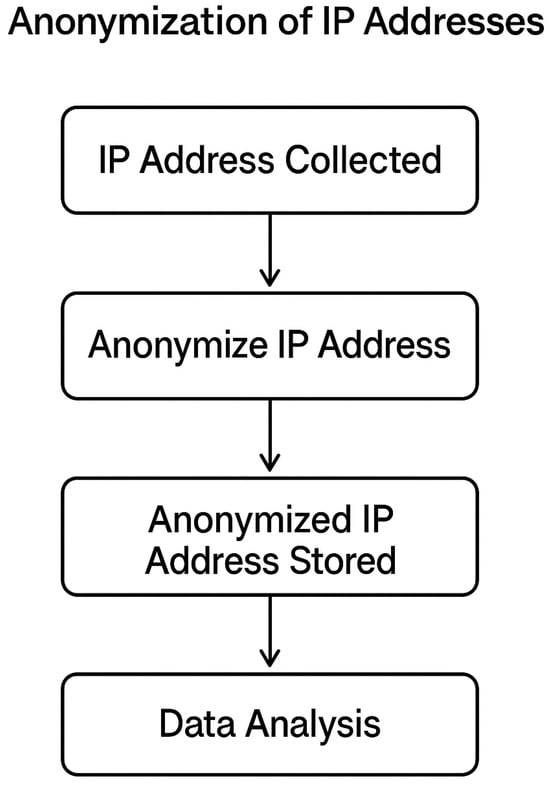

Abnormal value detection was conducted by identifying responses with extreme scores or z-scores exceeding 3 standard deviations from the mean for continuous variables. These procedures are detailed in Appendix B and follow established survey validation practices to reduce the influence of careless or invalid entries. Process followed for anonymization of IP Addresses is shown in Figure A1 in Appendix B.

The survey was conducted over a continuous two-week window to balance the need for timely data collection with achieving adequate sample size and response rates. Selecting a short, contiguous period reduced variation due to policy changes or abrupt infrastructure events and limited recall bias in respondents’ answers. The two-week span intentionally included both weekdays and weekend days to capture typical weekday commuting and weekend trip behaviours. To assess temporal bias, we examined day-of-week response patterns and found no meaningful differences in the key outcome measures; we also recorded time-of-day and controlled for it in regression models. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that a two-week snapshot cannot capture seasonal effects (e.g., weather-related changes in travel behaviour or longer-term infrastructure rollouts), and therefore we treat our findings as representative of the surveyed period rather than of year-round behaviour. Future work should collect data across multiple seasons or adopt a rolling-sample design to quantify and adjust for potential seasonal and longer-term temporal variability.

3.5. Data Preprocessing and Validation

Before analysis, the dataset was checked for:

- Missing values;

- Outliers;

- Response consistency.

Standard protocols for data validation and integrity were applied to ensure reliability and prepare the dataset for statistical modeling.

3.6. Statistical Analysis Strategy

Quantitative analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 28). The analytical process involved two stages:

- Descriptive Statistics—To summarize respondent profiles and satisfaction distributions, measures such as means, standard deviations, and frequency tables were computed.

- Inferential Analysis—Multiple linear regression was used to identify predictors of overall user satisfaction.

- Independent variables included:

- Frequency of use;

- Perceived cost;

- Safety perception;

- Convenience and infrastructure features.

Model diagnostics included R2, Adjusted R2, ANOVA significance tests, and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) scores to check for multicollinearity. This two-layer analysis enabled both summarization and causal exploration, offering insights into key infrastructure factors influencing user sentiment.

3.7. Ethical and Legal Compliance

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Newcastle University Institutional Research Ethics Committee. Participants were provided with an informed consent statement outlining the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation. Data was encrypted, anonymised, and securely stored in accordance with both UK data ethics policy and China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL).

Table 1.

QUESS-PAC framework.

Table 1.

QUESS-PAC framework.

| QUESS-PAC: Quantitative User Experience Survey Strategy for Public EV Charging Analysis in Cities BEGIN QUESS_PAC_Study //1. Define Research Framework SET Research_Philosophy = “Positivism” SET Research_Approach = “Deductive” SET Research_Strategy = “Cross-sectional Online Survey” SET Method_Type = “Mono-method Quantitative” //2. Design Questionnaire INITIALIZE Questionnaire with Sections: - Demographics - Usage_Patterns - Infrastructure_Satisfaction (cost, speed, layout, etc.) - Safety_And_Auxiliary_Perception SET Scale_Type = “5-point Likert” PERFORM Pilot_Test on N_pilot = 15 REFINE Questionnaire based on Pilot_Feedback //3. Data Collection SET Collection_Window = [June 5, 2024 → June 20, 2024] SET Platforms = [“Questionnaire Star”, “WeChat”] DISTRIBUTE Questionnaire via Platforms RECEIVE Responses_Total = 206 FILTER Responses_Valid where: - Time > 1 min - Location = “Shanghai” SET Responses_Final = 197 //4. Data Preprocessing and Validation REMOVE Outliers CHECK Missing_Values VALIDATE Response_Consistency //5. Statistical Analysis LOAD Data into SPSS COMPUTE Descriptive_Statistics: - Means, SD, Frequencies PERFORM Multiple_Linear_Regression: - DV = Overall_Satisfaction - IVs = [Usage_Frequency, Cost_Perception, Safety_Perception, etc.] EVALUATE Model_Fit: - R2, Adjusted R2, p-values - Check Multicollinearity (VIF) //6. Ethical and Legal Compliance OBTAIN Ethics_Approval from “Newcastle University” INFORM Participants via Consent_Form ANONYMIZE Data STORE Data Securely under PIPL_Compliance //7. Document Limitations IDENTIFY Limitations: - Self-report bias - Tech-literacy bias - Short time window RETURN Insights_for_Policy_and_Planning END QUESS_PAC_Study |

4. Experimental Results

This section presents the empirical findings derived from a structured questionnaire administered to electric vehicle (EV) users in Shanghai between 5 June and 20 June 2024. A total of 197 valid responses were analyzed to assess user satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure. The analysis proceeds through three stages: (1) demographic profile of respondents, (2) descriptive statistics on satisfaction indicators, and (3) multiple linear regression analysis to identify key predictors of satisfaction.

4.1. Measurement of Reliability and Validity

To evaluate measurement quality, both reliability and validity tests were conducted. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha values for the four dimensions ranged from 0.74 to 0.86, exceeding the 0.70 threshold, while CR values were all above 0.70, confirming acceptable internal reliability.

Construct validity was examined through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). EFA with principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation produced a four-factor solution consistent with the theoretical model, explaining 68% of total variance. Factor loadings exceeded 0.50 and cross-loadings remained below 0.30.

The CFA results further supported the measurement model. Model fit indices indicated satisfactory fit (χ2/df = 1.95, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05). Convergent validity was confirmed as all Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50. Discriminant validity was established using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, with the square root of AVE values greater than inter-construct correlations.

4.2. Demographic Profile

Table 2 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with male respondents comprising 46.7% and female respondents 43.1%; 10.2% preferred not to disclose their gender. The sample was largely composed of young to middle-aged adults, with the highest proportion falling within the 26–35 age range (29.4%), followed by 18–25 (24.4%) and 36–45 (22.3%).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic data for the participants.

Respondents were geographically diverse, 53.8% resided in suburban areas of Shanghai, while 46.2% lived in urban districts. EV charging frequency was notably high, with 38.6% of users charging daily and 48.7% charging weekly. Residential locations were the most common charging sites (40.6%), followed by workplaces (24.9%) and public venues (19.3%).

Regarding professional background, 70.6% of respondents were office workers, and 14.7% identified as self-employed. Students and retirees represented smaller shares. As for EV tenure, 26.9% had owned or leased an EV for 1–3 years, 23.4% for less than one year, and approximately 49.7% had used EVs for over three years—reflecting a balanced distribution between novice and experienced users.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics of Satisfaction Variables

Descriptive statistics were calculated for 11 key satisfaction variables related to public EV charging infrastructure which is shown in Table 3. It can be observed that overall satisfaction was low, with a mean score of 2.18 (on a 5-point Likert scale), indicating widespread dissatisfaction among respondents.

Table 3.

Data of statistical indicators.

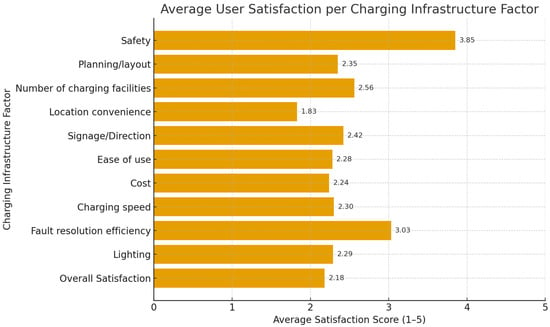

In Figure 3, average user satisfaction for different charging infrastructure factors are shown. The following are the key observations from Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Average User Satisfaction.

- Planning and layout of infrastructure scored a mean of (2.35), suggesting variability in perception depending on location.

- The number of available chargers yielded a slightly higher mean (2.56) likely due to spatial disparities in charger distribution.

- Location convenience had the lowest satisfaction (mean = 1.83), signaling user frustration with charger placement.

- Low satisfaction was also reported for ease of use (mean = 2.28), signage (mean = 2.42), and charging speed (mean = 2.30).

- Interestingly, lighting (mean = 2.29) and cost (mean = 2.24) were seen as insufficient, with substantial variance.

- Notably, fault resolution efficiency (mean = 3.03) and safety (mean = 3.85) received the highest ratings, suggesting diverging experiences across locations or time-of-day use.

These results underscore key weaknesses in the current infrastructure, particularly in placement, usability, and service responsiveness.

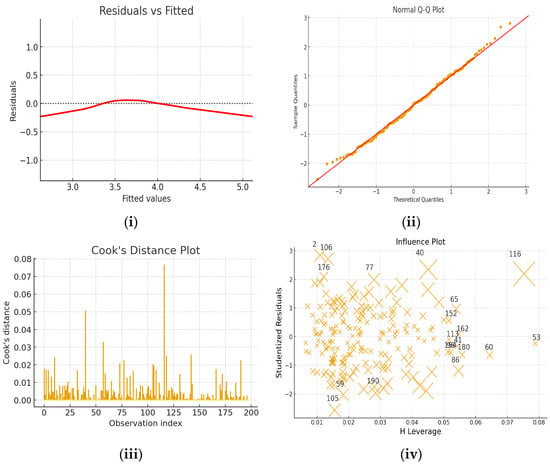

4.4. Regression Model Diagnostics

Prior to interpreting the regression results, diagnostic checks were performed. Multicollinearity was examined using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) scores, which ranged from 1.12 to 1.87, well below the recommended cutoff of 5 (and comfortably below the stricter threshold of 2).

Residual tests indicated that model assumptions were not violated. Normality was assessed via the Shapiro–Wilk test (p = 0.12) suggesting approximate normal distribution of residuals. Homoscedasticity was evaluated using the Breusch–Pagan test (p = 0.29), indicating no significant heteroskedasticity. Together, these results confirm the appropriateness of the regression specification.

A post hoc power analysis for the regression model, indicates that this study had high power (≈0.99) to detect medium to large effect sizes, although smaller effects may remain undetected. Therefore, while the findings provide useful insights into key drivers of user satisfaction, the results should be interpreted cautiously, and future studies could employ larger samples to capture smaller effects and improve generalizability.

4.5. Multiple Regression Linear Analysis

To identify the key drivers influencing user satisfaction with public electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure in Shanghai, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted. The dependent variable was users’ overall satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure. Twelve independent variables were selected based on theoretical and empirical relevance, capturing the multidimensional aspects of user experience: satisfaction with (1) planning and layout, (2) the number of charging facilities, (3) location convenience, (4) signage and instructional clarity, (5) ease of use, (6) charging costs, (7) charging speed, (8) fault resolution efficiency, (9) lighting conditions, (10) safety, (11) availability of payment options, and (12) customer support responsiveness.

A preliminary assessment using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) indicated that the regression model was statistically significant. As shown in Table 4, the model yielded an F-statistic of 19.690 with a corresponding p-value of < 0.001, suggesting that the set of predictors collectively explains a substantial proportion of the variance in user satisfaction. The model’s R2 value was 0.7026, indicating that approximately 70.26% of the variation in satisfaction ratings is accounted for by the selected variables.

Table 4.

ANOVA Summary for Regression Model.

Table 5 presents the standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients predicting user satisfaction with public charging infrastructure. Standardized coefficients (β) provide insight into the relative magnitude of each predictor, while the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) indicate the precision of the estimates. Satisfaction with the planning and layout of charging infrastructure had a significant positive effect on overall user satisfaction (B = 0.265, 95% CI [0.149, 0.381], β = 0.299, p < 0.001), indicating a moderate impact. Similarly, ease of use (B = 0.200, 95% CI [0.086, 0.314], β = 0.218, p < 0.001) and cost (B = 0.283, 95% CI [0.171, 0.395], β = 0.341, p < 0.001) were significant positive predictors, with cost showing the largest standardized effect. Satisfaction with lighting (B = 0.142, 95% CI [0.041, 0.243], β = 0.163, p = 0.008), also contributed positively, albeit to a lesser extent. In contrast, directions/instructions (β = 0.093, p = 0.140), location convenience (β = 0.097, p = 0.119), charging speed (β = 0.082, p = 0.286), number of chargers (β = 0.036, p = 0.596), fault-resolution efficiency (β = −0.013, p = 0.831), and safety (β = −0.025, p = 0.653) were positive or near-zero but not statistically significant at α = 0.05 as shown in Table 5 due to lower variation in responses and lower prioritization of these attributes.

Table 5.

Standardized and Unstandardized Coefficients of Predictors of User Satisfaction.

These results highlight that perceived cost, usability, lighting and planning/layout are the most influential aspects shaping user satisfaction with public charging infrastructure, while other aspects play a smaller or non-significant role. In contrast, variables such as satisfaction with signage clarity, location convenience, safety, fault resolution, and charging speed, while positively correlated, did not achieve statistical significance.

To enhance the interpretability of the regression results, we examined standardized effect sizes and explored their practical implications. Location convenience and charging speed exert the strongest effects on user satisfaction, indicating that improvements in these areas would yield the greatest benefits, while cost sensitivity plays a moderate but meaningful role. Interaction analysis shows that cost sensitivity varies significantly across income groups, with lower-income respondents being more price responsive, whereas age has no significant moderating effect. The non-significance of safety may reflect the high baseline levels of perceived safety in Shanghai and the prevalence of well-lit, monitored charging sites, which reduce variability in user perceptions. In contrast, satisfaction with fault resolution efficiency was relatively higher, although the lower response rate for this item suggests either infrequent encounters with malfunctions or limited awareness about fault resolution. These findings highlight the value of combining statistical interpretation with contextual insights to inform targeted infrastructure planning.

Further, residual Plot to visually assess linearity and homoscedasticity, normal probability plot to examine the normality of residuals, Crook’s Distance Plot, and Influence Plot to identify potential influential observations are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(i) Residual Plot, (ii) Normal Probability Plot, (iii) Crook’s Distance Plot, (iv) Influence Plot.

These findings reveal a nuanced picture of user satisfaction, wherein affordability, intuitive design, and physical layout significantly affect perceptions of public charging quality. Infrastructure developers and policy makers should prioritize these components when planning upgrades and new installations, as optimizing them may yield the highest return in consumer trust and adoption.

4.6. Spatial Usage

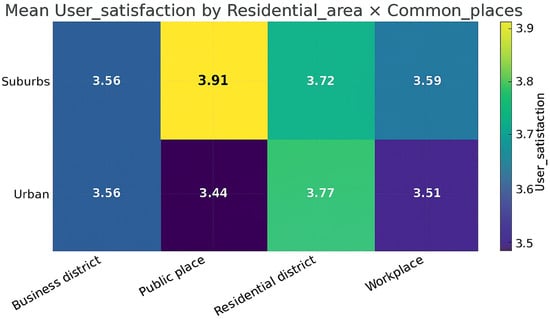

A heat map of Residential area × Commonly used places clarifies how satisfaction varies across settings as shown in Figure 5. Across N = 197 observations, mean overall satisfaction is 3.65/5 (SD ≈ 0.83), with 32.0% of respondents rating ≥ 4. Clear clustering emerges: the highest cell is Suburbs × Public place = 3.91, whereas the lowest is Urban × Public place = 3.44. Collapsing by rows and columns, Suburbs (3.70) exceed Urban (3.59) on average; by place, Residential district (3.74) and Public place (3.67) outperform Business district (3.56) and Workplace (3.55). Taken together, these patterns indicate that context of use is at least as influential as aggregate geography, with public-place charging producing both the best and worst outcomes depending on residential area.

Figure 5.

Heat Map for Spatial Usage.

4.7. Variation in Satisfaction Across Demographics

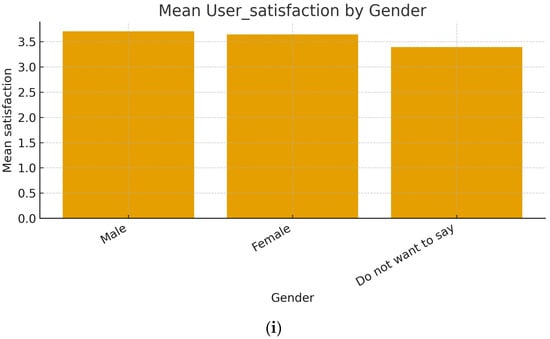

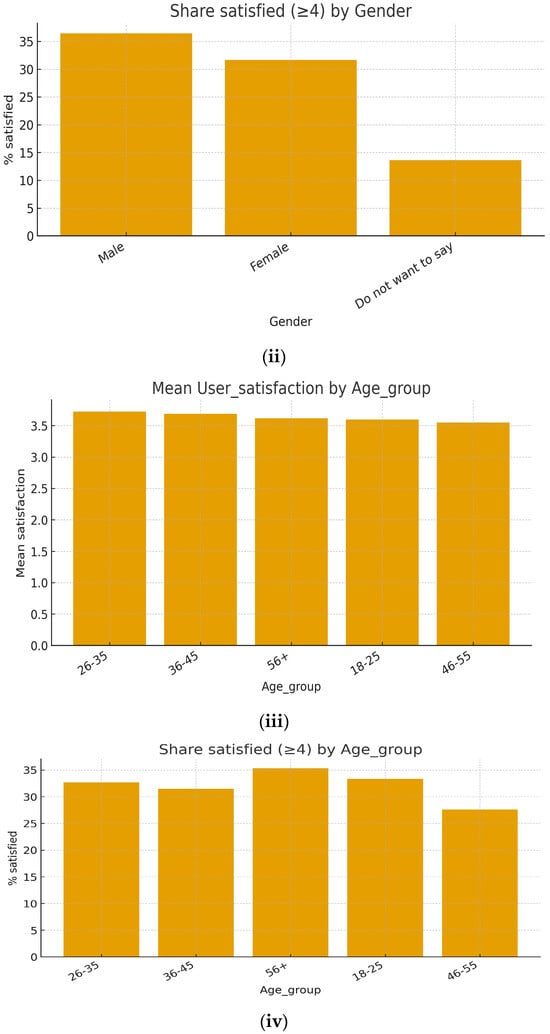

Demographic segmentation as shown in Figure 6i–iv highlights modest but systematic differences in satisfaction. Gender: mean scores are Male 3.70, Female 3.65, and Prefer not to say 3.39; the share satisfied (≥4) follows the same order—36.5%, 31.6%, and 13.6%, respectively. Age group: mean satisfaction ranks 26–35 (3.72) > 36–45 (3.69) > 56+ (3.61) > 18–25 (3.59) > 46–55 (3.55), while shares satisfied are broadly similar (≈27.6–35.3%). Notably, the 56+ group shows a slightly higher proportion satisfied despite a lower mean than the two leading age brackets, suggesting greater polarization among younger respondents.

Figure 6.

(i) Mean User Satisfaction by Gender. (ii) Shared Satisfied (%) by Gender. (iii) Mean User Satisfaction by Age Group. (iv) Shared Satisfied (%) by Age Group.

4.8. Visual Diagnostics of Predictors

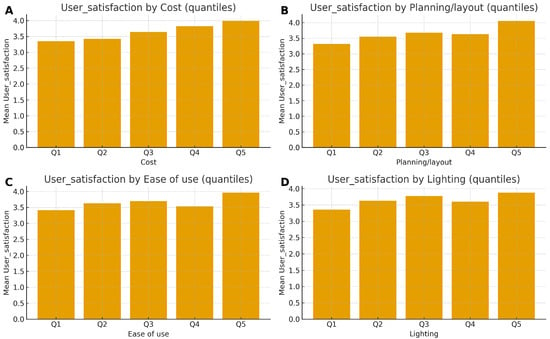

Comparative visualization of significant predictors is shown in Figure 7. Small-multiple panels show mean overall satisfaction by predictor quantiles (Q1–Q5), enabling like-for-like comparison of effect shapes. Cost exhibits a strong, near-monotonic increase across quantiles with no clear plateau through Q5, indicating broad gains as perceived pricing/fairness improves. Planning/layout delivers the largest total uplift but with diminishing returns, the steepest improvements occur when moving from lower to mid quantiles (Q1 → Q3), while gains taper beyond ~Q4. Ease of use rises consistently yet gently concave, suggesting mild tapering at higher quantiles—usability fixes help most at underperforming sites. Lighting shows the shallowest but steady gradient, consistent with a hygiene factor that enhances comfort/safety across the board without large marginal jumps. Overall, the visual patterns triangulate the regression ordering (Cost ≥ Planning/layout > Ease of use > Lighting) and highlight where moving assets from low to mid–high performance bands yields the most efficient satisfaction gains.

Figure 7.

(A) User satisfaction by cost, (B) User satisfaction by planning/layout, (C) User satisfaction by ease of use and (D) User satisfaction by lighting.

5. Discussion

This study examined user satisfaction and preferences regarding public electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure in Shanghai through a user-centered, data-driven approach. Based on survey responses from 197 EV users, this research identified key service features influencing user satisfaction and offered empirical insights for optimizing urban charging networks. The findings provide both theoretical contributions to transport behavior literature and practical implications for policymakers and infrastructure developers.

5.1. Summary of Findings

The analysis shows that overall user satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure in Shanghai is relatively low, with an average score of 2.18 out of 5. The lowest-rated aspect was location convenience, reflecting user perceptions of spatial planning limitations that reduce accessibility and convenience.

The multiple regression analysis indicates that four factors were statistically associated with overall satisfaction: (1) planning and layout, (2) ease of use, (3) cost, and (4) lighting conditions. Among these, cost satisfaction exhibited the strongest statistical association with overall satisfaction, aligning with prior studies that emphasize the role of transparent and fair pricing in shaping user evaluations of EV infrastructure [22]. These results underscore that concerns regarding pricing practices are closely linked with lower reported satisfaction and remain a significant dimension of user evaluation of charging services.

The analysis indicated that dissatisfaction with charging cost was among the strongest associations with overall satisfaction. To provide greater context, this finding has been linked to broader economic considerations. In particular, the perceived burden of charging expenses can be understood relative to average commuting expenditures in Shanghai, where transportation costs represent a non-negligible share of household budgets. This suggests that cost perceptions are not evaluated in isolation but in comparison with daily mobility expenses and the affordability of alternatives.

From a policy and operational perspective, the results point toward the potential relevance of differentiated pricing strategies. Previous studies have emphasized that transparent and competitive pricing is central to user acceptance of charging services [22]. Building on this, strategies such as time-of-use tariffs, location-based adjustments, or membership-based discounts could be explored to better align pricing with user expectations and ability to pay [22]. While this study does not establish causality, the observed associations highlight the salience of economic framing in user satisfaction and suggest directions for further investigation into equitable and transparent charging tariffs.

5.2. Divergences and Contextual Factors

One point of divergence lies in the importance of cost. This study identified cost as a key predictor, with low satisfaction ratings. However, [30] found that pricing concerns were less significant among higher-income users or those receiving employer subsidies. The discrepancy suggests that socioeconomic variables and subsidy schemes influence pricing perceptions, and that Shanghai’s consumer base may include a broader income distribution or face fewer financial incentives. Another inconsistency emerged regarding infrastructure sufficiency. Despite official data indicating a pile-to-vehicle ratio of 1:2.4 user perceptions of quantity varied [15]. This could stem from spatial inequities in infrastructure distribution—urban districts vs. suburbs as well as from subjective interpretations of what constitutes “sufficient” availability based on personal routines.

5.3. Practical Contributions

This research fills a critical knowledge gap by offering quantitative, user-centered insights into EV infrastructure satisfaction within a major Chinese megacity. Shanghai is often seen as a bellwether for EV policy and innovation and these findings can guide improvements in infrastructure planning across other rapidly urbanizing cities. Infrastructure providers and EV manufacturers can leverage the findings to prioritize site accessibility, user interface design, transparent pricing, and environmental safety measures. As EV usage scales, continuous refinement of user experience will be essential to sustaining both public engagement and market growth.

5.4. Theoretical Contributions in Travel Behavior and UX

5.4.1. Constructs and Empirical Anchors

We theorise four UX-linked mechanisms that shape overall satisfaction with public charging in dense megacities, each grounded in our Shanghai estimates (N = 197; 5–20 June 2024; SPSS): pricing salience (β = 0.341, p < 0.001), spatial fit/planning–layout (β = 0.299, p < 0.001), cognitive load reduction/ease of use (β = 0.218, p < 0.001), and environmental reassurance/lighting (β = 0.163, p = 0.008). See Table 4 (F = 19.690; R2 = 0.7026) and Table 5 for coefficients and CIs; model assumptions and VIFs are satisfied (VIF 1.12–1.87).

- Pricing salience = perceived affordability and fairness; the first-order acceptability filter for using public chargers (largest standardized effect).

- Spatial fit (planning/layout) = alignment of site placement, access, and on-site flow with users’ daily activity spaces; narrowing intention–action gaps (significant; also among lowest rated descriptively).

- Cognitive load reduction (ease of use) = interface/payment clarity that reduces errors and abandonment (significant positive predictor).

- Environmental reassurance (lighting) = hygiene factor that stabilises comfort at low cognitive cost, especially at night (smallest but significant β).

5.4.2. Mechanism Schema

We formalise the pathway urban constraints → (pricing salience, spatial fit, UX affordances, reassurance cues) → micro-routines & site choice → overall satisfaction. Visual small-multiples (Figure 7) triangulate shapes: near-monotonic gains for cost; steep Q1→Q3 rise and tapering for planning/layout; gently concave ease-of-use; shallow but steady lighting, consistent with a hygiene role.

5.4.3. Moderators and Heterogeneity (Evidence-Led)

Given Shanghai’s user mix (53.8% suburban; frequent weekly–daily charging), we theorise moderators that condition each mechanism’s strength:

- Income strengthens pricing salience (greater price sensitivity at lower income). Preliminary interaction exploration suggests this pattern. Proposition T1. The cost→satisfaction slope is steeper for lower-income users.

- Residential context (urban vs. suburban) amplifies spatial fit effects due to longer detours and parking constraints. T2. Planning/layout exerts larger effects for suburban residents than urban residents.

- Time pressure/care obligations (proxy via usage patterns) magnifies ease-of-use effects. T3. Ease-of-use benefits users on tighter schedules more strongly.

- Time-of-day moderates lighting; reassurance value rises at night. T4. Lighting’s effect increases under low-illumination use conditions. (Descriptive show wide variance in safety/lighting experience.)

6. Comparative Analysis with Existing Studies

A comparative assessment of the findings from Shanghai with existing empirical research in China and internationally reveals a high degree of convergence in the determinants of EV charging satisfaction and user experience (UX) as shown in Table 6 Despite the modest sample size of the present study (n = 197), the alignment with results from larger and methodologically diverse studies provides strong external validation for the identified predictors—particularly layout planning, usability, pricing transparency, and environmental safety conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison of the Shanghai case study with other cities.

6.1. Comparison with Other Cities in China

The closest methodological parallel is the mixed-methods study by [31], which surveyed 573 EV charging application (EVCA) users across first-tier, new first-tier, and second-tier cities in China. Although Li et al. focus on app-based charging experience rather than physical infrastructure, their identification of six central UX factors such as user-friendliness, payment convenience, information reliability, practical functionality, interactivity, and privacy protection shows strong thematic correspondence with the present study’s finding that ease of use and pricing are among the four most influential predictors of satisfaction in Shanghai. Both studies emphasise that the clarity of cost information and the simplicity of interactions (whether digital or physical) significantly shape users’ perceptions of charging quality.

Broader national assessments also corroborate the findings from Shanghai. Multi-city surveys such as [22,32] report consistent dissatisfaction among Chinese EV users regarding infrastructure accessibility, reliability of charging points, and transparency of pricing structures. These patterns resonate with the low average satisfaction scores observed in the present study and with regression results that highlight layout, cost, and usability as the primary determinants of user satisfaction. The alignment with these large-scale studies suggests that concerns reported by Shanghai users represent broader systemic challenges within China’s rapid EV transition rather than idiosyncratic issues arising from the local context.

At the megacity level, [33] provide a large-scale analysis of EV user sentiment in Beijing through 168,000 crowd-sourced reviews combined with geographically weighted regression (GWR). Their findings show that lighting conditions, perceived safety, and district-level accessibility of chargers are the strongest explanatory factors driving both positive and negative user evaluations. This finding is highly consistent with the results from Shanghai, where lighting emerged as one of the four statistically significant predictors of satisfaction and safety was rated as a major concern among respondents. The parallels between Beijing and Shanghai—China’s two largest EV markets suggest that safety and environmental assurance are central UX issues in high-density urban charging ecosystems, where night-time charging and mixed residential-commercial land uses are common.

6.2. Comparison with Global EV Charging UX Research

The determinants identified in Shanghai also align closely with findings from international literature. Multi-criteria evaluations in Germany emphasise accessibility, user interface clarity, reliability, and pricing transparency as primary drivers of public charging satisfaction [30]. Similarly, the annual J.D. Power EVX Public Charging Satisfaction Studies in the United States identify reliability, ease of use, and payment experience as the strongest influences on driver satisfaction, highlighting sustained dissatisfaction arising from charger downtime, broken connectors, and inconsistent pricing [19].

7. Policy Recommendations

Based on the observed associations in this study, several approaches could be considered to enhance user satisfaction and promote more equitable access to public EV charging infrastructure in Shanghai. While detailed charger location data were not available in this study, the findings highlight spatial, cost, and usability factors that can guide actionable strategies:

- Incentivize off-peak charging through time-of-use tariffs. Differentiated pricing for electricity consumption at different times of day can encourage balanced utilization of charging stations, helping to alleviate congestion during peak hours and improving overall user experience.

- Introduce targeted subsidies for low-income EV users. Given the link between cost perceptions and satisfaction, financial support mechanisms—such as reduced service fees, usage credits, or targeted vouchers—could address affordability concerns among economically vulnerable user groups.

- Promote equitable deployment through public–private partnerships. Collaboration among municipal authorities, state-owned enterprises, and private operators can support strategic placement of charging stations in under-served areas, including suburban and peri-urban neighborhoods, to improve accessibility and reduce spatial inequities in coverage.

- Improve usability and standardize user interfaces. Consistent payment methods, intuitive UI/UX design, and clear operational instructions across operators can reduce complexity, minimize errors, and enhance ease of use.

- Enhance environmental reassurance and perceived safety. While safety was not a statistically significant predictor in this study, proper lighting, well-maintained facilities, and visible security measures were associated with higher satisfaction, particularly in suburban and less-dense areas.

- Integrate supportive technologies and feedback mechanisms. Real-time information on charger availability, mobile app integration, and user feedback channels can empower users, facilitate planning, and enable operators to respond quickly to service issues.

- Increase chargers in mixed-use districts with both commercial and residential demand. Expanding public charging infrastructure in mixed-use districts—areas that combine residential, commercial, and recreational facilities—can substantially enhance both accessibility and utilization rates of EV chargers.

- Urban design integration. Integrating EV charging infrastructure into urban design frameworks ensures that charging stations are not treated as isolated utilities but as functional elements of the built environment. Urban design integration involves aligning charger placement with land-use planning, pedestrian flow, parking layout, lighting, and public amenities to enhance both aesthetic coherence and user convenience.

It is important to note that these recommendations are derived from observed associations rather than causal evidence. Future studies, particularly longitudinal or experimental designs, could incorporate geospatial analyses of charger distribution to directly evaluate how spatial factors influence satisfaction across different urban contexts and user groups.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

8.1. Conclusions

Electric vehicles’ (EVs) adoption depends not only on environmental awareness or policy incentives but also on the perceived quality, accessibility, and usability of charging infrastructure. This study examined user satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure in Shanghai based on 197 valid survey responses. Despite notable progress in expanding the city’s EV ecosystem, the findings indicate generally low levels of satisfaction, with an overall average score of 2.18 out of 5. Regression analysis identified four factors that were statistically associated with overall satisfaction: infrastructure planning and layout, ease of use, cost transparency, and lighting conditions.

Among these, cost-related satisfaction showed the strongest statistical association with overall satisfaction, consistent with concerns over pricing models or perceived value. The lowest-rated aspect was location convenience, reflecting user perceptions that the current distribution of charging stations is not well aligned with everyday travel and residential patterns across urban and suburban areas.

The analysis assists policymakers, infrastructure operators, and manufacturers in refining service delivery and investment priorities. Further, it may be useful to make decisions related to the following aspects:

- Identifying areas where charging stations could be expanded or redistributed to improve accessibility;

- Enhancing usability through interface design and operational flow;

- Improving pricing transparency to reduce dissatisfaction related to perceived costs.

Although rooted in the Shanghai context, these findings provide a reference point for other rapidly urbanizing cities seeking to expand EV charging networks in ways that users perceive as accessible, reliable, and inclusive.

8.2. Limitations and Future Work

While this study provides valuable insights into the user experience of public electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure in Shanghai, there are some limitations: First, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference, limiting the ability to determine the directionality of observed relationships. Second, the sample size (197 respondents), while sufficient for exploratory analysis, may not fully represent all EV user groups in Shanghai. Third, the online-only data collection approach may underrepresent older adults or individuals with lower digital literacy, introducing potential sampling bias. Fourth, the short two-week survey window restricts the ability to capture longitudinal dynamics or seasonal variations in charging behavior.

The comparison between our survey sample and Shanghai’s general population highlights notable differences. The overrepresentation of younger adults and higher-income individuals, along with the higher rate of EV ownership in our sample, may lead to more favorable attitudes toward electric vehicles than those observed in the broader population. These differences should be considered when interpreting the findings, as they may affect the external validity of our study. Given these discrepancies, caution is advised when extrapolating our results to the general population of Shanghai. Future studies should aim for a more demographically balanced sample to enhance external validity. Additionally, employing weighting techniques to adjust for these demographic imbalances could provide more accurate estimates reflective of the city’s population. Although cost concerns emerged as statistically significant predictors of satisfaction, future research using longitudinal surveys, quasi-experiments, and mixed-method approaches is needed to confirm causal relationships. Despite these constraints, the structured QUESS-PAC framework provides a scalable, evidence-based approach for assessing user satisfaction with public EV charging infrastructure. It can be applied or adapted to other urban contexts to generate comparable insights and guide future research with larger, more diverse samples and robust study designs.

For a megacity-scale population such as Shanghai, the ideal sample size for a simple random survey can be approximated using Cochran’s formula. Assuming a 95% confidence level and the conservative proportion p = 0.5, achieving a ±5% margin of error would require a minimum of approximately 384 respondents. In contrast, our sample of 197 users corresponds to an estimated margin of error of approximately ±7% at 95% confidence. While this is higher than the classical statistical benchmark, the present study is exploratory in nature and focuses primarily on identifying the relative influence of key satisfaction determinants rather than producing precise population-level estimates. Moreover, the consistency of our results with findings from larger national and international studies further supports the robustness and validity of the extracted behavioural patterns. The sample size is therefore considered adequate for the regression-based analysis conducted in this research.

Another limitation lies in the exclusive use of quantitative data [34]. While the statistical analysis successfully identified key predictors of satisfaction, it did not capture the nuanced perspectives, emotions, or situational challenges that may influence user experiences. The subjective nature of satisfaction responses, influenced by individual expectations and personal biases, adds variability to the dataset. Furthermore, this study did not investigate potential interaction effects between variables or perform segmentation analysis across demographic groups, which could have revealed differentiated satisfaction drivers for various user segments.

Although cost concerns emerged as statistically significant predictors of satisfaction, future research using longitudinal surveys, quasi-experiments, and mixed-method approaches is needed to confirm causal. Expanding the sample to include a broader demographic—particularly across varying income levels, gender identities, and geographic locations (urban vs. suburban)—would enhance the generalizability of findings. Additionally, longitudinal studies are recommended to monitor changes in satisfaction over time, especially as infrastructure improvements and policy interventions are implemented. Investigating how pricing perceptions, interface usability, and environmental awareness evolve with user experience could inform the next generation of EV infrastructure planning and policy. Also, some in-person interviews can be conducted with the underrepresented population of the survey to validate the findings. This study did not include a spatial or GIS-based accessibility analysis, as detailed geospatial data on the locations of charging stations within the city is currently unavailable. This represents a data limitation that, if addressed in future research, could provide more robust insights into location-related user dissatisfaction. At present, comparable studies examining user satisfaction with charging infrastructure in other megacities using similar methods and indicators are not yet available, which limits the possibility of conducting a quantitative benchmarking analysis. This study therefore represents an important first step toward enabling future cross-city comparisons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and S.D.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., S.D. and S.R.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X., S.R. and S.D.; writing—review and editing, X.X. and S.R.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, S.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Newcastle University on [21 April 2024].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study during the survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available based on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Robustness Check

To ensure the stability of the results, an ordered logit regression was estimated as an alternative to the OLS specification, given the ordinal nature of the satisfaction variable. The results were consistent with the main model: planning/layout, ease of use, cost, and lighting remained statistically significant predictors with the same directional effects. Coefficient magnitudes and significance levels showed only minor variation, confirming robustness.

In addition, bootstrap estimation with 1000 replications produced confidence intervals similar to those in the baseline model, further reinforcing the reliability of the findings.

Appendix B. Data Cleaning and Abnormal Value Detection

This appendix provides a detailed description of the procedures used to ensure data quality prior to analysis.

Appendix B.1. Initial Screening

A total of 228 responses were collected. To remove low-quality or irrelevant entries, the following criteria were applied:

- Completion time: Responses completed in under one minute were excluded to eliminate overly rapid or careless submissions.

- Straight-line answering: Responses exhibiting identical answers across all items were removed, as these patterns indicate low engagement.

- Duplicated IP addresses: Multiple submissions from the same IP were excluded to prevent repeated participation.

- Location verification: Only respondents reporting residence in Shanghai were retained.

After this initial screening, 197 valid responses remained, representing an effective response rate of 86%.

Appendix B.2. Abnormal Value Detection

Abnormal values in continuous survey variables were identified using the following procedures:

- Standard deviation method: Responses with z-scores exceeding ±3 were flagged as outliers.

- Inspection and documentation: Identified extreme values were reviewed to ensure that they did not reflect plausible responses or data entry errors.

All excluded responses and extreme values were documented and are available for replication purposes. These procedures follow established survey validation practices and aim to reduce the influence of careless, invalid, or anomalous entries.

Appendix B.3. Data Anonymization

To comply with privacy regulations and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL):

- IP addresses and any personally identifying information were anonymized.

- All cleaned datasets used for analysis contain no direct identifiers, ensuring respondent confidentiality.

The structured cleaning and abnormal value detection process supports the reliability of the survey data and provides a transparent foundation for the subsequent statistical analyses.

Figure A1.

Flowchart of Anonymization of IP Addresses.

References

- IEA [International Energy Agency]. Global EV Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- EEA [European Environment Agency]. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Hedges & Company. Global Car Ownership Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://hedgescompany.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Kováčiková, K.; Novák, A.; Novák Sedláčková, A.; Kováčiková, M. The Environmental Consequences of Engine Emissions in Air and Road Transport. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. The Energy Transition: Challenges and Opportunities. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Cano, Z.P.; Banham, D.; Ye, S.; Hintennach, A.; Lu, J.; Fowler, M.; Chen, Z. Batteries and fuel cells for emerging electric vehicle markets. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Y. Integrated planning of static and dynamic charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajper, S.Z.; Albrecht, J. Prospects of Electric Vehicles in the Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Daily. China’s Charging Infrastructure Reaches Record Highs. 2024. Available online: https://www.people.cn/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Hardman, S.; Jenn, A.; Tal, G.; Axsen, J.; Beard, G.; Daina, N.; Figenbaum, E.; Jakobsson, N.; Jochem, P.; Kinnear, N.; et al. A review of consumer preferences of and interactions with electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA [International Energy Agency]. Global EV Outlook 2024: Trends in Electric Vehicle Charging. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- ICCT [International Council on Clean Transportation]. China’s New Energy Vehicle Industrial Development Plan for 2021 to 2035. Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/chinas-new-energy-vehicle-industrial-development-plan-for-2021-to-2035/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- AUTOVISTA. BYD Took Control of the 2023 Chinese EV Market 2023. Available online: https://autovista24.autovistagroup.com/news/byd-took-control-of-the-2023-chinese-ev-market (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality China’s Plans and Solutions. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202511/08/content_WS690ee812c6d00ca5f9a076cd.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Shanghai Bureau of Transportation. Annual Vehicle Ownership Report; Urban Transport Bulletin; Shanghai Bureau of Transportation: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Consultancy.asia Report: China Leads the Way in EV Charging Infrastructure Globally. Consultancy Asia. 2024. Available online: https://www.consultancy.asia/news/5674/report-china-leads-the-way-in-charging-infrastructure-globally (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Roland Berger GmbH. EV Charging Index 2024—Deep Dive: Norway. 2024. Available online: https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_pdf/roland_berger_ev_charging_index_deep_dive_norway.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Chi, Y.; Xu, J.-H.; Yuan, Y. Consumers’ Attitudes and Their Effects on Electric Vehicle Sales and Charging Infrastructure Construction: An Empirical Study in China. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.D. Power. U.S. Electric Vehicle Experience (EVX) Public Charging Study; J.D. Power: Troy, MI, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2023-us-electric-vehicle-experience-evx-public-charging-study (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Malarkey, D.; Singh, R.; MacKenzie, D.; U.S. Department of Energy; U.S. Department of Energy; U.S. Department of Energy; Joint Office of Energy and Transportation; ChargeX Consortium; University of Washington; Plug In America; et al. Customer Experience at Public Charging Stations and Its Effects on the Purchase and Use of Electric Vehicles. 2023. Available online: https://inl.gov/content/uploads/2023/07/Customer-Experience-at-Public-Charging-Stations_INLRPT-23-74951_12-12-23_Optimized-1.pdf?__cf_chl_f_tk=2ZsxIn1Z6ZBYy6aUuW7zEZSOwR7iLlJq41CGMbYw7D0-1766672356-1.0.1.1-BStIDx651H39F3peOQ2cXlIh5DOHGFg6ZbtssLNJz00 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Sarda, J.; Patel, N.; Patel, H.; Vaghela, R.; Brahma, B.; Bhoi, A.K.; Barsocchi, P. A Review of the Electric Vehicle Charging Technology, Impact on Grid Integration, Policy Consequences, Challenges and Future Trends. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 5671–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, B. Are Consumers in China’s Major Cities Happy with Charging Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles? Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, R.; Schmidt, T.; Van Heek, J.; Ziefle, M. Fast-Charging Station Here, Please! User Criteria for Electric Vehicle Fast-Charging Locations. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 40, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Sarder, M. Development of a Bayesian Network Model for Optimal Site Selection of Electric Vehicle Charging Station. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 105, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Cheng, X.-b.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.-p. Research on Location and Capacity Optimization Method for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Considering User’s Comprehensive Satisfaction. Energies 2019, 12, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G. Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse Res. 2018, 25, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Technology acceptance model: TAM. In Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption; Al-Suqri, M.N., Al-Aufi, A.S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 1989; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.B.L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fabianek, P.; Madlener, R. Multi-Criteria Assessment of the User Experience at E-Vehicle Charging Stations in Germany. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Ling, W.; Zhao, L.; Pan, Y. Enhancing user experience in Electric Vehicle Charging Applications (EVCA): A comprehensive analysis in the Chinese Context. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 18495–18530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Yang, M. Changes in consumer satisfaction with electric vehicle charging infrastructure: Evidence from two cross-sectional surveys in 2019 and 2023. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, P.; Yao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Z. Enhancing Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Planning with Pre-Trained Language Models and Spatial Analysis: Insights from Beijing User Reviews. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M.; Leng, H.; Ren, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y. Physics-informed deep learning for virtual rail train trajectory following control. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 261, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.