Abstract

The global shift toward sustainable transport electric vehicles (EVs) is at the core of decarbonization efforts. While advanced economies have achieved their rapid adoption through strong policies and incentives, emerging markets face structural and behavioral barriers. This study investigates the paradox in Morocco, whereby a significant automotive capacity contrasts with a minimal domestic BEV market share of 0.6%, despite 143% growth from a small base, using a four-dimensional framework encompassing financial, infrastructural and energy, policy and institutional, and behavioral–social factors. The research integrates a literature review, a survey (n = 522), and secondary data on charging infrastructure and EV sales. Findings reveal a strong value–action gap: 69% of respondents acknowledged EVs’ environmental benefits yet only 1.1% owned one and 42% had considered buying. The high upfront costs of EVs influenced over 70% of participants, and a significant association was confirmed between charging availability and purchase intent (χ2 = 34.80, p < 0.05). Urban-centric charging, fragmented governance, and skepticism persist as barriers. The study concludes that industrial strength alone cannot ensure adoption without targeted incentives, equitable infrastructure, and cultural shifts in ownership perception, offering key insights for policymakers in emerging economies pursuing sustainable mobility.

1. Introduction

1.1. Global EV Imperative

The transportation sector is a key candidate for decarbonization efforts in the power sector, accounting for nearly a quarter of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. In an attempt to mitigate its environmental impact, governments are prioritizing the electrification of mobility infrastructure. Amid this transition, electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a promising solution, offering improved urban air quality as well as lower lifecycle emissions if powered with renewable energy [2,3].

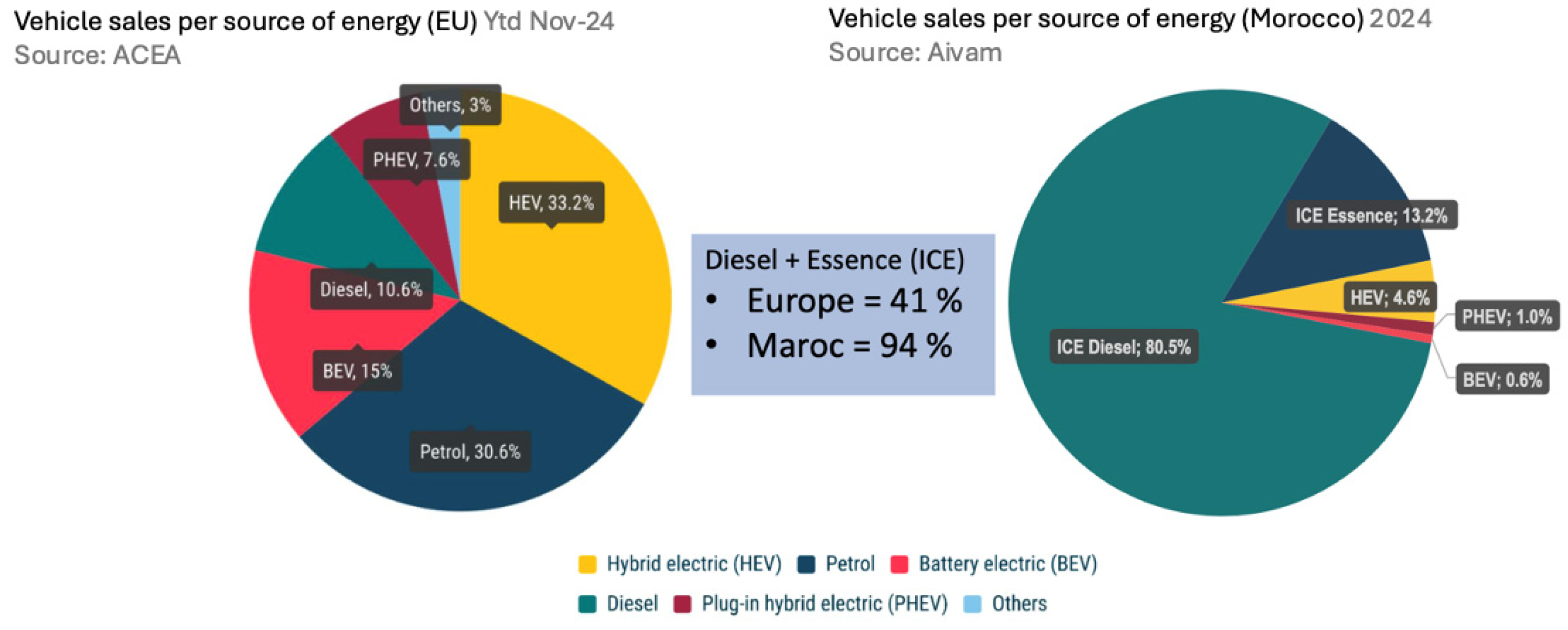

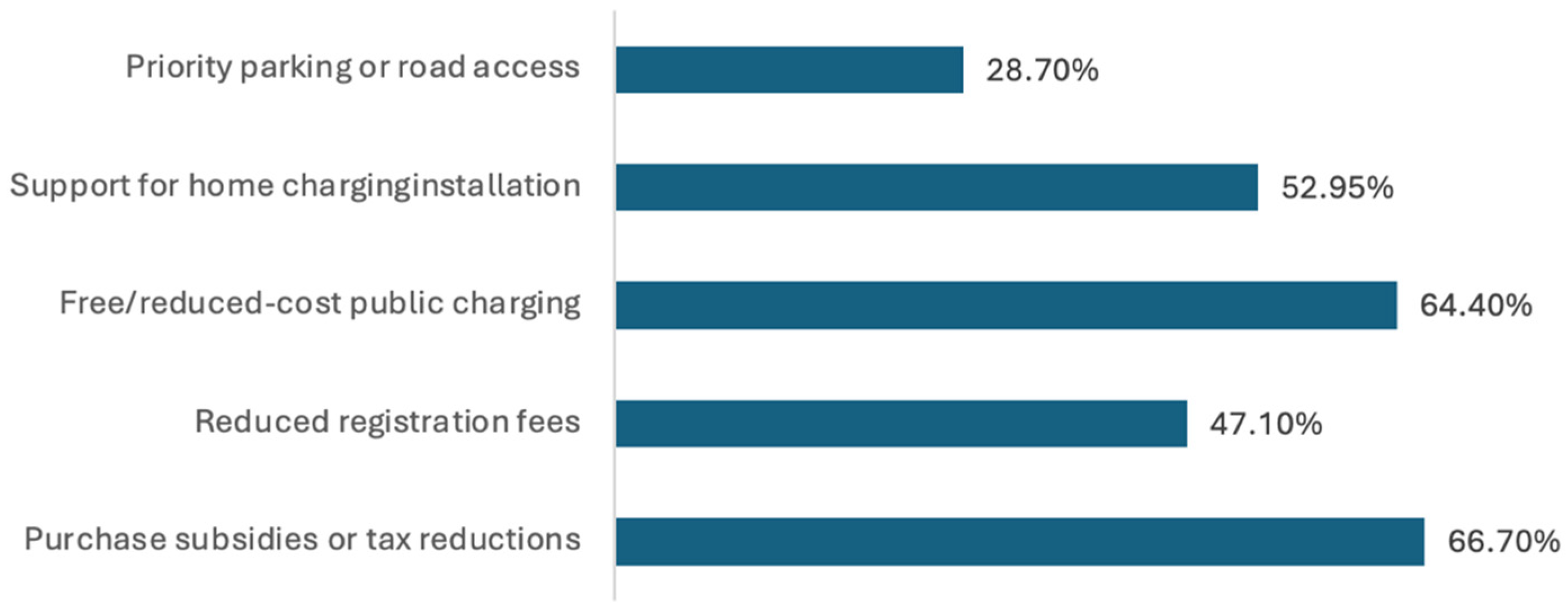

However, a stark divide is evident in the global adoption of this technology. As illustrated in Figure 1, developed economies are rapidly transitioning to electrified powertrains, while emerging economies like Morocco remain dominated by internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles [4].

Figure 1.

Divergence in powertrain adoption between Europe and Morocco [4].

Recent analyses in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region highlight a consistent pattern of barriers. In Egypt, adoption is restrained by high upfront costs, charging infrastructure deficits and accelerated battery degradation in extreme climates [5]. Similarly, in Jordan, economic constraints, insufficient charging networks, and consumer skepticism are identified as critical impediments [6]. This regional context underscores the need for technological solutions to be integrated within nuanced socio-economic and infrastructural ecosystems, a challenge that this study investigates through the specific case of Morocco.

1.2. Morocco’s Automotive Paradox

To fully contextualize the adoption paradox, it is essential to understand the structure of Morocco’s automotive market. The new market, while significant at 176,401 units in 2024, including 157,139 passenger vehicles (VP) and 19,262 utilities (VUL) [4], is highly concentrated both geographically and by brand. The Casablanca region alone accounted for 41.1% of national VP sales, with the top ten brands, led by Dacia, Renault, Hyundai, Peugeot, Volkswagen, capturing 77.6% of the market [4]. Furthermore, this new car market is overshadowed by the scale of the used car sector, which saw approximately 600,000 transactions in 2019 alone [7]. This demonstrates that for the vast majority of Moroccan households, second-hand vehicles are the primary means of acquiring mobility. This trend is further supported by the sales composition of new cars: fleet purchases from rental companies constitute 35% of the VP sales, indicating the private new car is a subset of a larger used vehicle ecosystem. The transport landscape is diverse; alongside cars, over 1.4 million motorbikes were in circulation as of 2020 [7]. The two-wheeler segment is cheap—a new gasoline scooter can be acquired for as little as 8000 MAD—establishing them as a crucial mode for urban commuting. However, given that road transport is the largest producer of GHG emissions in the sector and passenger cars remain dominant for family and intercity travel, they represent the critical segment for a systemic mobility transition.

Emerging economies are critical to the success of the global EV transition. Countries like Morocco, with a rapidly urbanizing population, rising energy consumption requirements, and decreasing air quality, are both vulnerable to environmental degradation and essential to promoting global sustainable goals [8]. Morocco particularly presents a compelling case study due to its significant production–adoption paradox. Despite notable progress in automotive manufacturing, EV adoption remains constrained. This can be attributed to several interrelated challenges, including a lack of charging infrastructure, high initial costs, insufficient legislative incentives, and limited citizen knowledge. These obstacles are firmly embedded within the socio-economic and policy environment; understanding them is required in order to create a context-specific implementation plan.

Over the past five years, Morocco has built industrial momentum on the supply side. It has established itself as an African automotive leader, with export revenues of more than $8 billion [9], and a yearly production capacity of 700,000 vehicles, expected to reach 1 million by the end of the year [10]. This industrial ambition extends directly to EVs; according to Ryad Mezzour, Minister of Industry, its local production capacity is 40,000 EVs per year with a target of 107,000 units annually, constituting a 53% capacity expansion [11]. This will further strengthen Morocco’s position as an export hub for manufacturers such as Renault, Peugeot, Yazaki, Stellantis, and others [10].

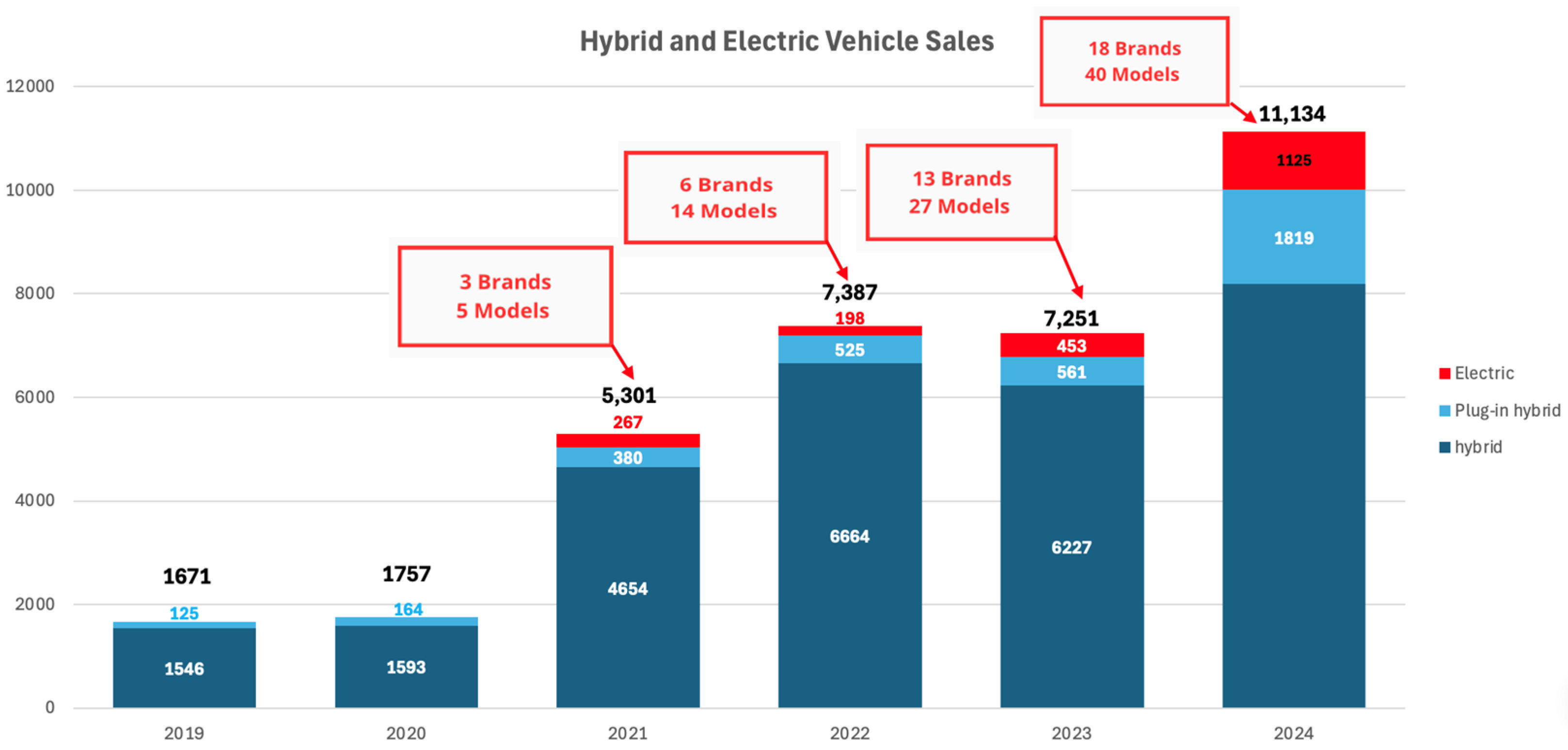

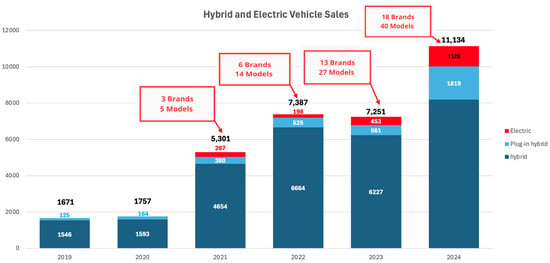

EV sales increased to 11,023 units in 2024 compared to the 7251 units in 2023, representing a 52.02% year-on-year improvement [12]. This growth was supported by major strategic investments. The first milestone was reached in June 2025 with the inauguration of the COBCO manufacturing plant in Jorf Lasfar, which is Morocco’s first facility dedicated to producing lithium-ion battery materials, established to strengthen the local EV value chain [13]. This project was followed by strategic ventures that highlight Morocco’s global ambitions. In a landmark deal, South Korea’s LG Chem partnered with China’s Huayou Group to construct an LFP cathode material plant in Morocco for mass production by 2026, with an annual capacity of 50,000 metric tons, sufficient to supply batteries for 500,000 EVs. This investment targets the North American Market to leverage Morocco’s free trade agreement with the United States to qualify for subsidies under the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) [14].

Domestically, the Moroccan CDG Group partnered with the Chinese European Gotion High Tech in November 2024 to construct a gigafactory for EV battery production. In parallel, the Chinese auto battery manufacturers, Hailiang and Shinzoom, have selected Kenitra to be the desired location for a copper anode and energy storage system production plant. The project’s first phase entails an investment of 13 billion MAD for a 20 GWh capacity of lithium-ion battery cells and packs [15].

Critically, these initiatives are aligned with a national industrial strategy designed to leverage Morocco’s natural sources. The OCP Group, renowned as a global phosphate leader, launched a green investment strategy back in December 2022 with the explicit objective of producing 30,000 tons of intermediate products for lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries by 2027 [16]. This alignment is strategic since it will allow COBCO, Gotion High Tech, and LG CHEM to operate within a domestic EV battery value chain, lining upstream phosphate processing at OCP with midstream battery and cell production, and finally downstream automobile assembly.

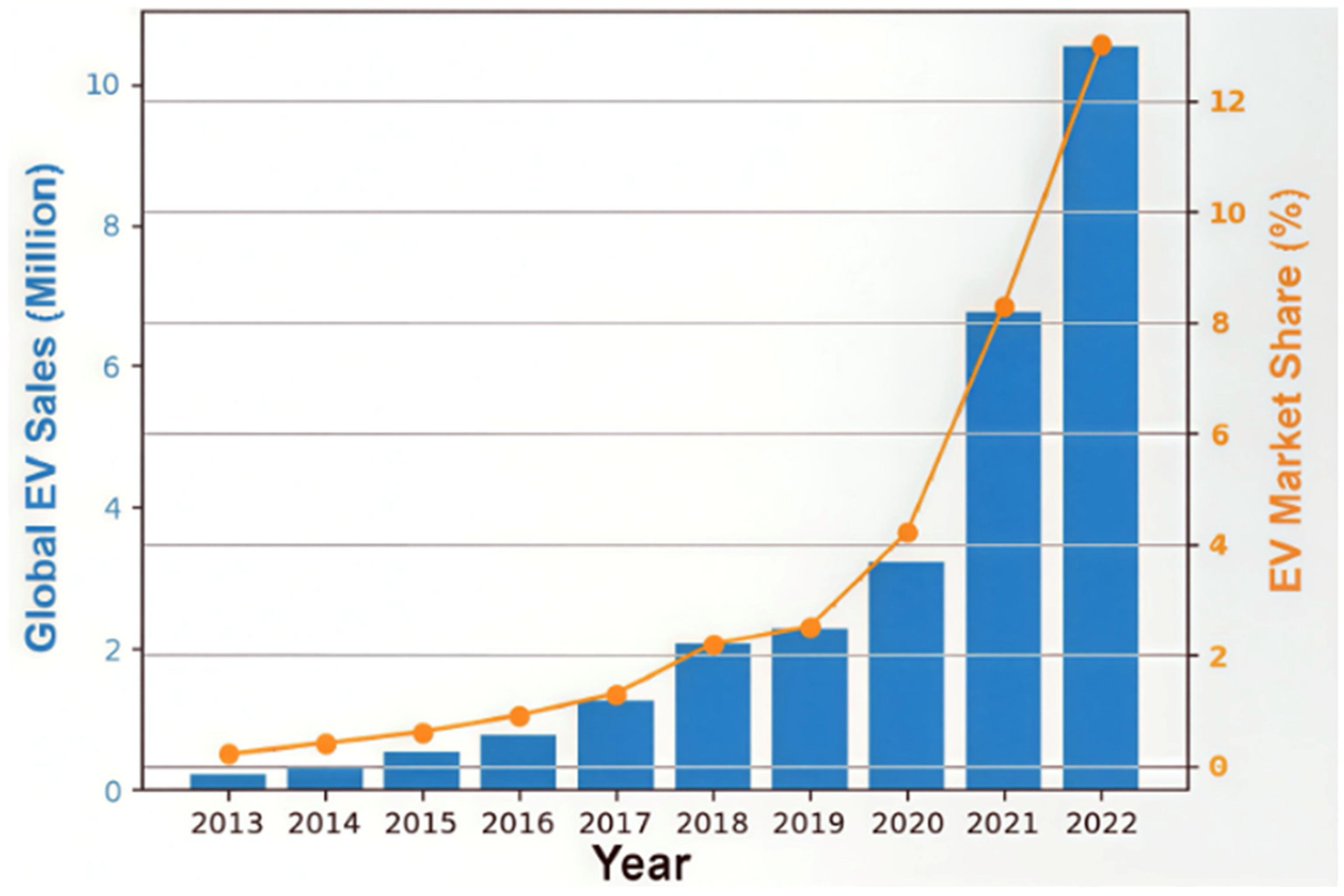

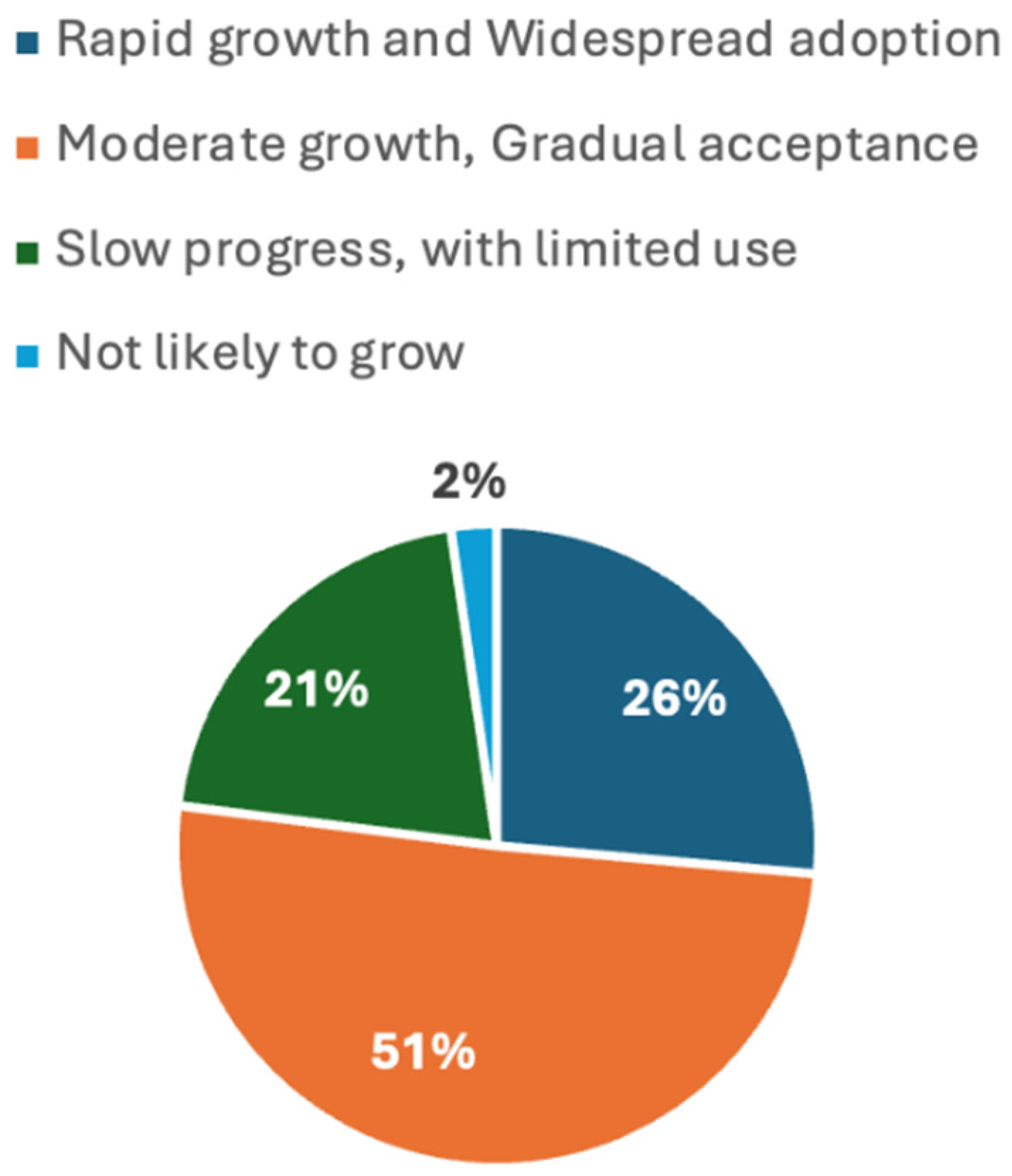

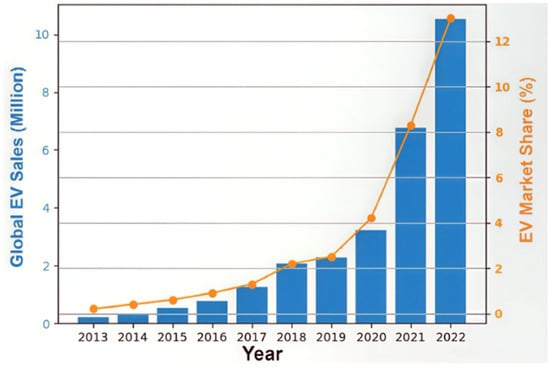

This aggressive industrial ambition stands in contrast to domestic market realities, creating a production–adoption paradox. While global EV sales have followed a characteristic exponential growth curve (Figure 2), Morocco’s domestic trajectory remains stubbornly linear.

Figure 2.

Global EV market penetration [17].

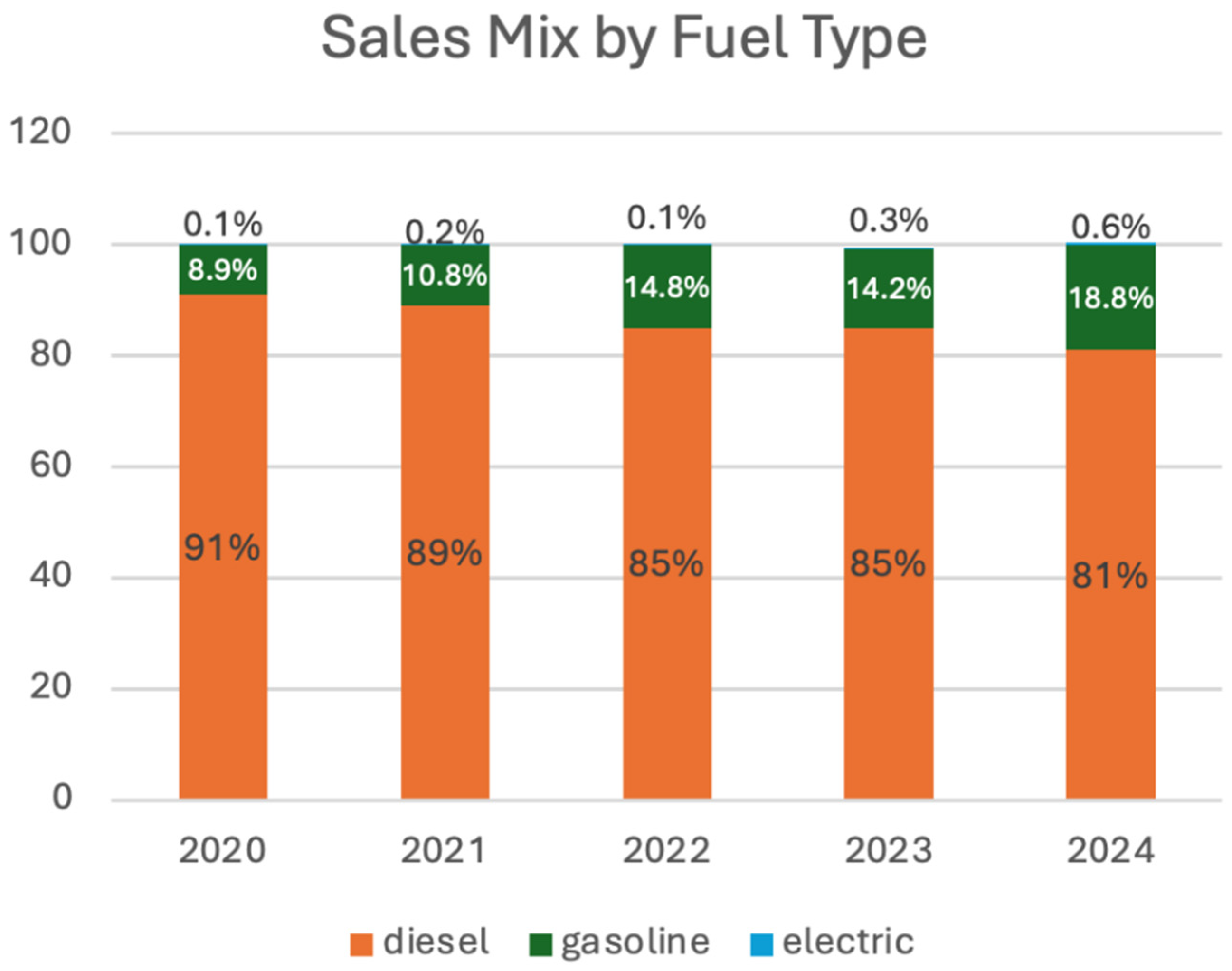

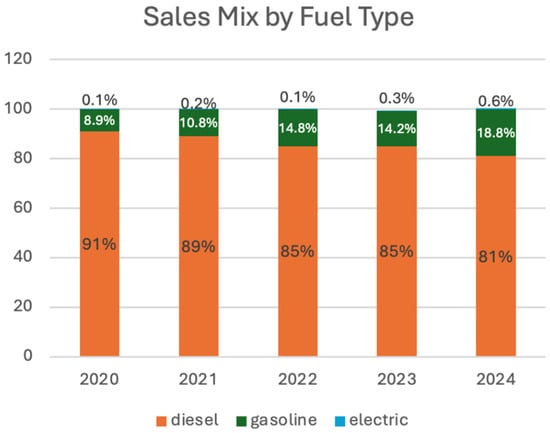

The depth of the adoption challenge is visible in two areas: the composition of new car sales and the overall vehicle fleet. The market share of new Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) remains critically low. As shown in Figure 3, despite a 143% year-on-year increase, only 1.125 fully electric units were sold in 2024, representing merely 0.6% of the 176,401 new vehicles sold in 2024 [4].

Figure 3.

Sales mix by fuel type in Morocco [4].

This marginal share of BEVs in new sales is reflected in the overall vehicle fleet, with a lower penetration rate. Figure 4 illustrates the market’s overwhelming reliance on ICEs, which dominated 99.77% of the total fleet in 2023 compared to the 0.04% of BEVs and 0.19% of HEVs [18].

Figure 4.

Morocco’s share of sales per type of engine [4].

This adoption crisis stems from several structural barriers within Morocco’s socio-economic and policy environment. The affordability gap presents a primary challenge: the most affordable EV in Morocco is the Dacia Spring. Priced at 215,000 MAD [19], approximately twice the cost of comparable combustion vehicles, this single model constitutes 40% of all 2024 BEV sales [4]. In parallel, the market is evolving with recent entry of competitive Chinese brands. BYD, a global leader in EV sales, has officially entered the Moroccan market and is directly competing in the premium segment. Their initial sales of 120 BEVs indicate that its market entry has yet to overcome the fundamental barriers of price and infrastructure [4].

Simultaneously, the infrastructural gap persists. Morocco has only approximately 1000 public charging stations in urban areas. While plans are underway to install an additional 1500 units around Rabat, Casablanca, and Tangier by 2026 [11], this urban-focused strategy risks creating geographical disparities, and hindering nationwide adoption.

Although the literature has extensively documented generic barriers to EV adoption in emerging economies [20,21,22], a critical methodological gap remains. Existing research often relies on theoretical models or macro-analyses, with few integrating empirical consumer data with region-specific infrastructural and socio-economic indicators to produce a multi-dimensional adoption profile [23,24]. This has resulted in a fragmented understanding that fails to capture the systemic nature of adoption barriers.

Regional studies [5,6] effectively outline region-specific challenges, but they typically do not combine qualitative consumer surveys with holistic analyses of the national industrial strategy and policy landscape. In the Moroccan context, existing research has either focused on industrial and export capabilities [9,10,11] or has provided high-level policy analyses [23]. These streams of research have progressed in isolation, collectively neglecting the demand-side consumer adoption dimension. Consequently, the specific mechanisms through which financial, infrastructural, and policy barriers manifest at the consumer level and interact to suppress adoption are not well understood. It is this neglected demand-side dimension that this study targets.

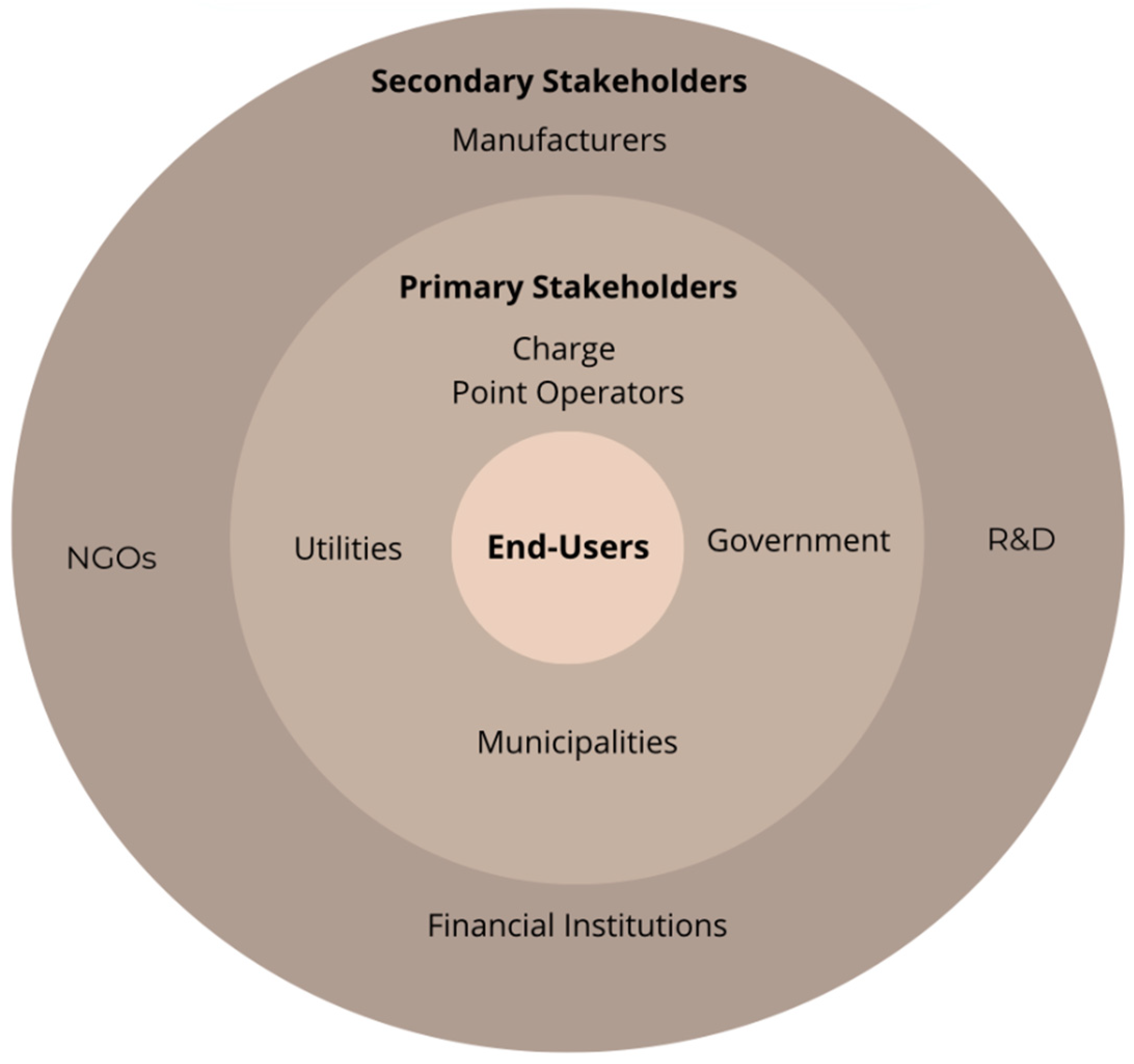

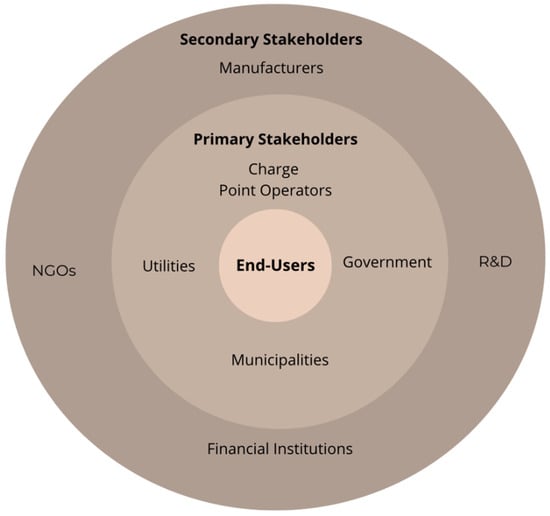

The following stakeholder analysis conceptualizes the consequence of this academic gap: a systemic over-reliance on a supply-push model that is fundamentally disconnected from the end user.

1.3. Stakeholders in Morocco’s EV Transition

The challenge of EV integration is that it is governed by a multi-stakeholder complex ecosystem. However, this ecosystem operates on a supply-push model, where primary and secondary stakeholders are actively pushing the technology into the market through industrial policy investment and new model offerings. As shown in Figure 5, the success of every stakeholder is entirely contingent upon the end user’s decision to adopt. This structure reveals a critical misalignment between supply-side strategy and demand-side reality.

Figure 5.

Stakeholder map of EV transition.

The actors in this model can be categorized as follows:

- Primary stakeholders: Entities that are directly impacted by daily EV operations and infrastructure deployment. This group includes national governments responsible for setting fiscal incentives and regulatory policy, regulators and municipalities planning grid integration and charging standards utilities, charge point operators managing the physical infrastructure, the energy flow, and the pricing of public charging networks, and ultimately EV users whose adoption determines market success [17].

- Secondary stakeholders: Entities that are indirectly involved but have interests in outcomes of the transition. This group includes vehicle manufacturers and battery industries responsible for determining the local value chain and relying on market uptake for ROI, financial institutions whose role is to devise leasing and credit scheme to improve affordability, NGOs and community groups advocating for equitable access, environmental benefits, and public awareness, and, lastly, environmental and research institutions who run R&D, and provide lifecycle analyses and sustainability metrics [17].

Therefore, this paper argues that end-user understanding is the central challenge of this transition. The stakeholder map highlights the points of friction between the market’s push and the consumer’s pull; thus, it addresses the decisive determinant of the national EV strategy. The subsequent analysis of consumer barriers provides a critical test of the viability of the current supply-push approach.

1.4. Theoretical Framework

To address this gap, this study develops an analytical framework grounded in, but extending, established theoretical models. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) offer valuable micro-level insights into perceived usefulness, ease of use, attitudes, and behavioral controls [25,26]. However, they often take for granted the stable infrastructural and institutional contexts of developed countries. Conversely, the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) provides a macro view of sociotechnical transitions but has been applied fragmentally in Morocco, failing to connect the interplay between niche-level consumer behavior (EVs), sociotechnical regimes (established ICE automotive and energy systems) and landscape pressures (global decarbonization) [27]. Transitions are not just technological shifts, but fundamentally multi-dimensional struggles enacted by multiple social groups, from policymakers and firms to consumers and social movements within a context of rules and institutions [27].

To address the distinct complexities of emerging economies like Morocco, the paper proposes a four-dimensional framework that extends these established models by explicitly incorporating structural and institutional dimensions critical to emerging economies, which are often taken for granted. The identified framework categorizes barriers into the following four themes:

- Economic and Financial Barriers: Extending the cost benefit within TAM and TPB by addressing the affordability gap and financing constraints to forecast directly the influence on the perceived behavioral control and outcome beliefs in low- to middle-income contexts.

- Infrastructural and Energy Constraints: Discussing the role of technological readiness and accessibility, which are latent variables in traditional models, and primary determinants of perceived behavioral control within TPB and ease of use with TAM in emerging economies.

- Policy and Institutional Gaps: Considering the contribution of fragmented governance, regulatory uncertainty, and implementation capacity, thereby introducing a macro-institutional layer that influences subjective norms through government signaling and perceived control through incentive structure in sociotechnical analysis.

- Behavioral, Psychological, and Social Factors: Basing TPB and Diffusion theory in Morocco’s particular socio-cultural context by exploring risk perception, attitudes, and subjective norms regarding the social status of ICEs and environmental consciousness amidst economic constraints.

This framework pairs survey-based consumer perceptions with secondary data on EV registrations, charger density, income levels, thus offering a contextually grounded yet transferable analytical model. This approach examines interactions between structural contexts and individual agency, and diagnoses how infrastructural deficits and policy ecosystems amplify economic barriers and adoption resistance, in order to trace the future EV adoption trajectory.

1.5. Literature Review

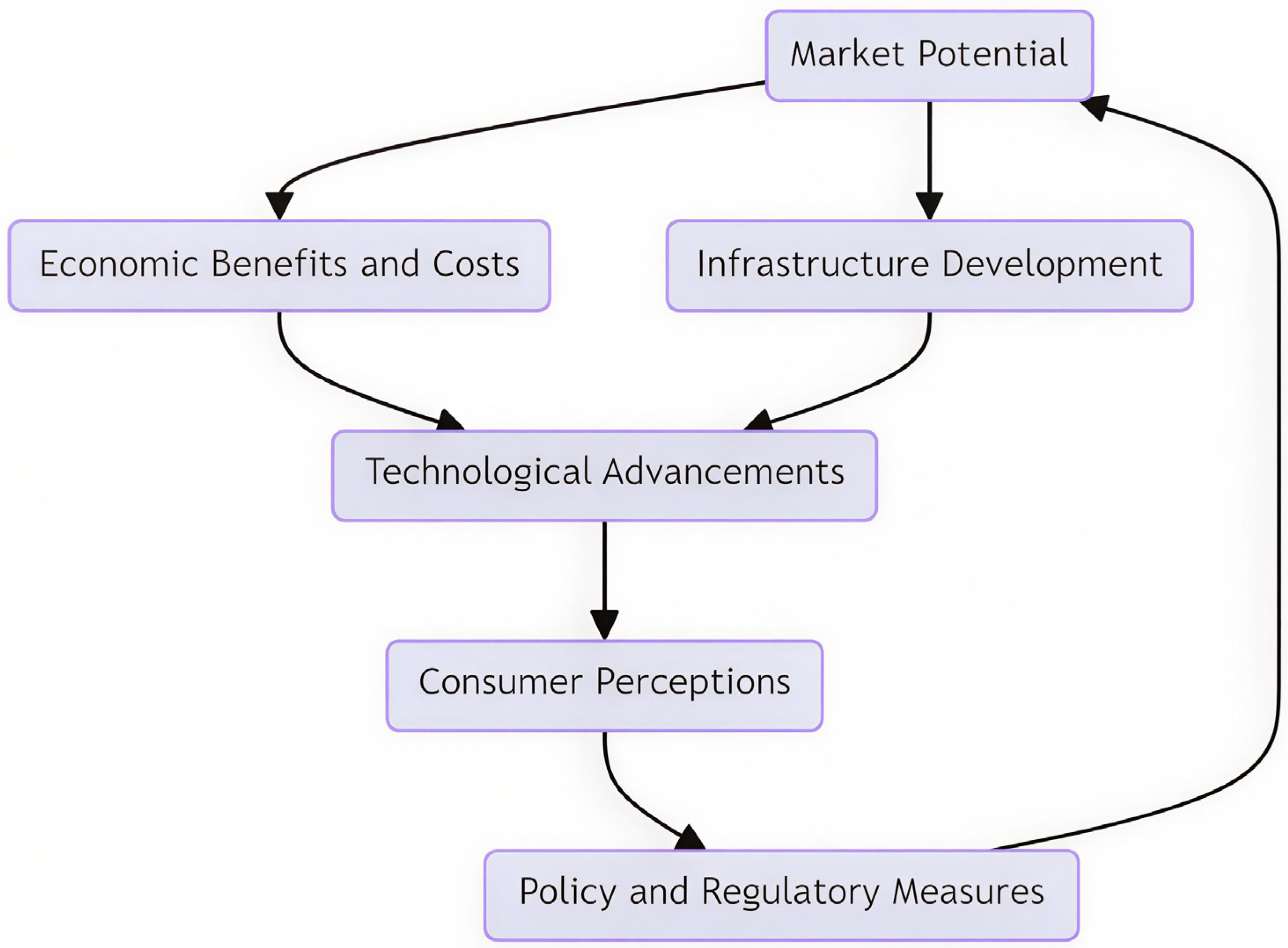

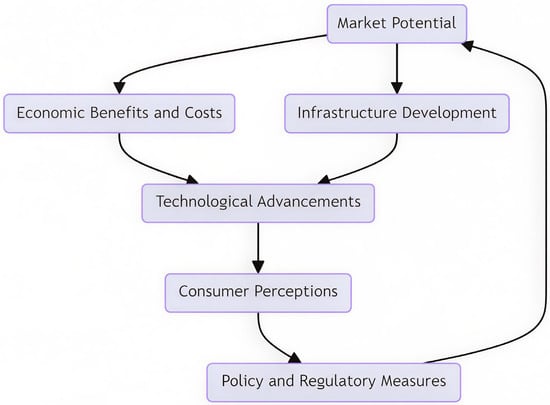

Despite the global momentum, EV adoption remains slow in emerging economies. Developed countries have advanced rapidly, driven by policy incentives, robust charging infrastructures, government subdivides, and strong public support; in contrast, emerging economies face distinct context-specific challenges that impede large scale deployment. The subsequent sections draw on these insights to inform a four-dimensional analysis of EV adoption barriers, including economic, infrastructural, governmental, and behavioral dimensions. These four dimensions form interconnected factors that shape EV adoption in Morocco, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Conceptual framework of interconnected factors influencing EV adoption [6].

1.5.1. Economic and Financial Barriers

While the literature rightly points out high upfront costs as one of the economic obstacles to EV adoption [20], this challenge is particularly systemic across emerging economies. In Egypt, the high purchase price is the dominant barrier across all customer segments, exacerbated by a lack of direct purchase subsidies [5]. The situation in Jordan mirrors this, where economic feasibility remains a primary concern for both consumers and businesses [6]. The case of Morocco reveals a significant market failure and a misalignment with global EV narratives. The discourse of long-term savings [20] is irrelevant to the majority of the population, for whom the initial capital investment is simply beyond the means, positioning EV as luxury commodities and raising serious questions.

EVs generally have a higher purchase cost than that of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), often costing twice as much, which becomes a turn-off to consumers who care about their money [20]. In Morocco, the affordability gap is increased by a lack of financial incentives and an increasing inflation rate. Morocco’s market dynamics provide a clear manifestation of this challenge. The dominance of a single low-cost model confirms consumers’ prioritization of upfront cost above all else. Indeed, they have a manufacturer who recognized this constraint; the success of Dacia Spring demonstrates that demand is concentrated at most accessible price point. In parallel, new entrants, like BYD, have introduced more affordable models. Notably, the Seagull, priced at 199,900 MAD [28], deliberately undercutting the Dacia Spring (215,000 MAD). However, the fundamental barrier remains. The barrier is not relative to the cost between EV models, but the absolute cost threshold, which lies beyond the reach of the average Moroccan consumer.

This price sensitivity is linked to battery cost, which accounts for a significant portion of an EV’s price and fuels concerns regarding long-term depreciation and non-existent second-hand markets [21]. Furthermore, the sector is currently unable to explore the economies of scale in emerging markets due to delayed adoption, making affordability barriers more difficult [21]. Consequently, potential adopters, who typically prioritize capital expenditure over total cost of ownership [20], perceive EVs as financial risks.

Therefore, the economic challenge is the fundamentally misaligned value proposition rather than a lack of policy effort. While fiscal incentives and infrastructure investments are necessary, they are still insufficient to change this reality. Overcoming this requires a strategic intervention that adapts its narrative to address the Moroccan crisis in case EV transition continues and even worsens existing socio-economic disparities.

1.5.2. Infrastructure and Energy Constraints

The infrastructural and energy dimension highlights a fundamental prerequisite for adoption, which is to critically inform the consumer about the ‘ease of use’ factor in TAM, constituting a core component of the ‘sociotechnical regime’ in transition theory. The severity of this regional infrastructural gap is evident. Egypt’s charger density stands at 0.5 per 10,000 km2, creating vast charging deserts [5], while Jordan’s plans for expansion are still evolving [6]. This contextualizes Morocco’s own challenge of approximately 1000 urban public chargers and highlights the risk of creating two-tier mobility systems.

The literature mentions the lack of extensive charging infrastructure as a barrier that impedes EV usability and leads to the continued range anxiety among potential end users [22]. Morocco’s approach reveals a strategic myopia, one that could worsen both spatial and social inequalities. With only 1000 chargers concentrated along the Tangier–Agadir highway, rural and peri-urban areas face very low coverage. The scale of the deficit is underscored by the national target of 25,800 stations by 2030 [23]. This disparity in infrastructure discourages EV use outside of major cities and creates a two-tier mobility system where electric mobility is the privilege of the connected urban elite, while the majority of the population remains locked into the ICE regime.

Morocco’s charging infrastructure faces energy and technical limitations. EV charging systems are classified into three levels. Although Level 1 is affordable and suitable for household use, it cannot be used for long-distance travel since the battery takes a long time to recharge. Level 2 is more suited to offices and commercial zones due to its medium charging pace. Level 3’s DC rapid charging enables speedy charging within 20 min but comes with heavy installation and grid strengthening expenditures [29]. Consequently, widespread Level 3 DC deployment is expensive, while the slower Levels 1 and 2 are often incompatible, as apartment living is common and home charging is not a universal option.

Beyond the physical infrastructure, integrating EVs into the national grid presents a challenge. Uncoordinated charging risks overloading unstable networks. While smart charging systems and Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) systems can balance demand and create a financial incentive via energy arbitrage [30,31], they remain theoretical in Morocco due to limited implementation capacity.

Morocco’s energy challenges lie in the grid’s current composition. Although installed renewable capacity is significant, at 42% of total capacity in 2020 and projected to be 52% by 2030, thermal sources from coal, and fuel oil and gas still dominated by 77.8% in 2023, compared to the 20.5% from wind and solar [32]. Consequently, the grid lacks the flexibility and capacity to absorb the extra load from mass EV charging [18]. Previous reinforcement efforts [33] are insufficient to support the massive electrification of transport sector.

While renewable energy-powered EV charging stations represent a sustainable ideal, their grid integration is hindered by the intermittency of renewables [34], and a lack of energy storage systems. Without substantial investment in smart grids, this infrastructure deficit will persist as a key barrier to EV adoption. Ultimately, Morocco’s strategy has yet to address the transformation of the entire energy systems to support mobility equitably and reliably.

1.5.3. Policy and Institutional Gaps

Policy fragmentation is a recurring theme in the MENA region. Patterns of Fragmented governance are not unique to Morocco but reflect broader regional challenges. In Egypt, policies still lack clarity and show slow implementation, resulting in raised market uncertainty [5]. Similarly, the Jordanian context calls for more integrated frameworks to overcome institutional inertia [6]. This pattern underscores that fragmentation, a known challenge in contemporary policy gap analysis [23], signals a strategic ambiguity. In Morocco, this contradiction is embodied in the form of aggressive industrial EV ambitions and automobile manufacturing juxtaposed with a laissez-faire, reluctant approach to stimulating domestic adoption.

Policy frameworks are means to accelerating EV adoption, particularly where economic and infrastructural readiness is underdeveloped. Globally, effective policies fall into two categories: demand-oriented policies, such as subsidies, charging infrastructure, and non-financial incentives, and supply-oriented policies introducing the ZEV mandates for fleet [35] and R&D incentives to catalyze local manufacturing and diversify model availability. Currently, Morocco remains constrained to micro-EV models such as Citroen AMI, Fiat Topolino, and Opel Rocks-e, alongside localized initiatives such as the ‘iSmart’ charging stations project launched by the Green Energy Park in Benguerir [23].

The country has made some preliminary moves to promote EV adoption by providing fiscal incentives such as a reduction in VAT, excise duties at a reduced concentration (2.5%), and an exemption of luxury and road taxes. Nonetheless, when compared to comprehensive policies such as those utilized in Norway, where generous EV subsidies are combined with significant fossil fuel taxes in an attempt to achieve a 22% EV market share, these attempts remain disconnected and fragmented, far removed from major EV markets in emerging economies [22]. The regulatory system is still decentralized, without unified rules regarding charging systems and integrating vehicles.

The creation of a centralized governance system is crucial, suggesting a national commission as a body where all the involved parties coordinate their efforts, including public, industrial, and academic stakeholders. Although Morocco is pushing for tighter emission regulations following Euro 6 emission standards, long-term policy alignment with EV targets aiming for 30 per cent EV market share in government fleets is aggressive and still needs policy adjustment [23]. A lack of formalized rules to charge service and interoperability is yet more evidence of barriers to EV adoption in Morocco.

The fragmented governance structure surrounding EV policymaking and execution is the other major obstacle. The Ministry of Energy Transition, the Ministry of Transportation, AMEE (Moroccan Agency for Energy Efficiency), and local municipalities are among the ministries and entities currently involved in EV-related initiatives in Morocco. A lack of a national EV strategy or central authority results in disorganized work, disparities in standards, and unnecessary resource utilization. In contrast to other nations who have EV task committees or national coordination, Morocco has taken numerous separate steps that lack long-term rationality [23]. A cross-sectoral approach bringing together the efforts of the consumer base, infrastructure, financing, and policy in one cohesive endeavor is a much-needed reform.

Thus, the policy barrier is rooted in a lack of political alignment of industrial ambitions with consumer reality. The uncoordinated ministries are logical outcomes of a system that has not yet made EV adoption a genuine national priority, failing to bridge between a supply-push industrial model and a non-existent customer pull.

1.5.4. Behavioral, Psychological, and Social Factors

Beyond structural issues, consumer perception is key. In Egypt, low public awareness and skepticism about EV performance are significant hurdles, especially in rural areas [5]. Jordania studies similarly point to the role of social norms and environmental awareness in shaping adoption intentions [6]. This establishes a regional background of behavioral barriers against which Morocco’s own value–action gap can be analyzed.

Behavioral studies often treat range anxiety and status perception as universal psychological traits [17,25]. In Morocco, these are not innate consumer attributes but rational responses to a deficient ecosystem. Range anxiety is a direct consequence of sparse charging infrastructure and the perception of ICE as status symbols is a rational assessment where EV ownership introduces more uncertainty than prestige.

Cultural and social contexts further sustain existing adoption restrictions. Across emerging economies, social barriers include consumer awareness, perceived risk, trust in technology, peer influence, and cultural attributes toward green mobility [36,37]. For instance, EVs in Morocco are generally perceived as environmentally functional rather than aspirational, limiting their social appeal relative to ICE vehicles [38]. Early adopters tend to be more environmentally conscious and of a higher income, but EV ownership does not yet confer status signaling, which influences peer behavior and social acceptance.

Psychological factors also influence adoption. Concerns regarding battery safety, degradation, and low resale value reduce willingness to adopt EVs [36]. A recently identified phenomenon, Charging Point Trauma, has emerged from poor user experiences with operability, payment, and availability [39]. Additionally, low environmental knowledge and limited familiarity with EV technology exacerbate risk aversion, while less tech-savy consumers show resistance to behavioral changes [37].

Several theoretical frameworks explain these dynamics. Notably, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) posits that intentions are shaped by both personal attributes and perceived social norms [40]. Similarly, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) highlights perceived usefulness and ease of use as determinants of adoption, which are further influenced by social networks, including peers, family, and opinion leaders [25,40]. When influential actors express mistrust, these cues amplify doubt and hinder adoption. Frameworks like Individual–Community–Institutional Acceptance and Socio-Political–Community–Market Acceptance further emphasize the need for alignment between personal motivations, community norms, and supportive institutions to facilitate EV uptake.

Practical behavioral barriers include upfront cost, range anxiety, long charging durations, and lack of firsthand EV experience [17,18,25,41]. Trust in technology is particularly prominent: consumers are unlikely to adopt EVs unless they perceive their reliability, safety, and long-term value [36,39]. Demonstration projects, peer advocacy, and mass awareness campaigns can help build trust, reduce perceived risk, and reinforce positive social norms.

Evidence from countries with high levels of EV adoption such as Norway, China, and the United States confirms the importance of behavioral interventions alongside infrastructure and incentives [25]. Consumer education, test-driving initiatives, and visibly early adoption enhance confidence and normalize EV ownership. In Morocco, initiatives that combine public awareness campaigns, low-cost pilot projects, and transparent communication of long-term cost benefits could similarly increase adoption by shifting perceptions and building social trust.

Overall, behavioral and social barriers are not solely individual-level limitations but are often exogenous outcomes of wider infrastructural and institutional deficiencies. Policies attempting to change hearts and minds through awareness campaigns without fixing structural problems, are likely to have limited impact. A holistic approach that combines infrastructure, economic incentives, and culturally sensitive behavioral interventions is therefore essential for a socially inclusive EV transition.

Based on the literature reviewed above, Table 1 summarizes the key barriers to EV adoption across four themes, namely economic, infrastructural, policy, and behavioral dimensions. The themes identified in the literature review informed the design of the survey administered to current and potential Moroccan EV users, to ensure that the questions reflect empirically established barriers and enablers.

Table 1.

Summary of EV adoption barriers from the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study adopts a mixed-method exploratory design, combining primary survey data, systematic literature review, and secondary data augmentation. The integration of multiple data sources enables triangulation, as shown in Table 2 below, between consumer perceptions, documented barriers in the literature, and structural realities in Morocco’s EV ecosystem.

Table 2.

Triangulation of evidence of EV adoption barriers.

The specific methodological choices are justified as follows:

- The systematic literature review provided the theoretical foundation by (i) identifying established barrier categories from global and regional studies, (ii) informing the development of our four-dimensional analytical framework, and (iii) ensuring our research builds upon existing scholarship while addressing Morocco-specific gaps.

- The primary survey captured the end-user perspective by (i) quantifying consumer perceptions and purchase intentions, (ii) measuring the prevalence and relative importance of different barriers, (iii) analyzing interactions between economic infrastructural, and behavioral factors, and (iv) identifying consumer segments for targeted policy interventions.

- The secondary data analysis contextualized the findings within Morocco’s macro-environment by (i) providing objective metrics of EV market penetration and infrastructure deployment, (ii) substantiating the production–adoption paradox through industrial and trade data, and (iii) validating survey finding against actual national adoption patterns.

The power of this design lies in the active integration of these components; the survey quantifies consumer concern over systemic barriers, while the secondary data validates these perceptions against objective national strategies. This methodology moves beyond listing barriers to explain their systemic integration, offering a robust evidence base for understanding Morocco’s production–adoption paradox.

2.2. Primary Data Collection

An online questionnaire was distributed to a purposive sample of Moroccan residents presumed to have higher technological literacy and environmental awareness (e.g., university students, early-career professionals, and faculty). A total of 522 valid responses were collected between March and September 2025. It is important to note that this sampling approach, while strategic, limits the generalizability of the results to the entire Moroccan population, as it is skewed toward urban and educated demographics. The survey included four thematic sections: (1) demographics and mobility behavior, (2) EV awareness and perceptions, (3) charging infrastructure experience, and (4) policy expectations. Closed-ended questions used Likert scales (1–5), and open-ended questions allowed elaboration.

2.3. Data Analysis

The choice of statistical tests was guided by the nature of our research questions and data. The primary goal of this exploratory analysis was to identify and measure significant associations between categorial demographic and perpetual variables, and purchase intent Chi-squared tests of independence, complemented by Cramér’s V to measure effect size, are the standard and most interpretable methods for this purpose. While regression models can provide predictive insights, they require larger sample sizes and normally distributed data to produce stable and reliable coefficients. Our study’s focus was on establishing the foundational bivariate relationships between key barriers and consumer intent. Future research would be well-suited to build upon these findings with complex multivariate models.

2.3.1. Reliability Assessment

To evaluate the internal consistency of the survey scales, a reliability analysis was conducted. For the two-item infrastructural perception scale comprising station availability and availability importance, a Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated. The coefficient was negative (α = −0.190), which in the case of a two-item measure reflects the correlation rather than the scale reliability [44]. The negative value demonstrates an inverse relationship: respondents who perceived charging infrastructure as scarce assigned greater importance to station availability in their purchase decisions, whereas those who perceived infrastructure as sufficient attributed lower importance. This pattern aligns with consumer behavior and provides evidence that the survey captured coherent and interpretable responses. As the items do not form a unidimensional score, they were analyzed separately in subsequent analysis.

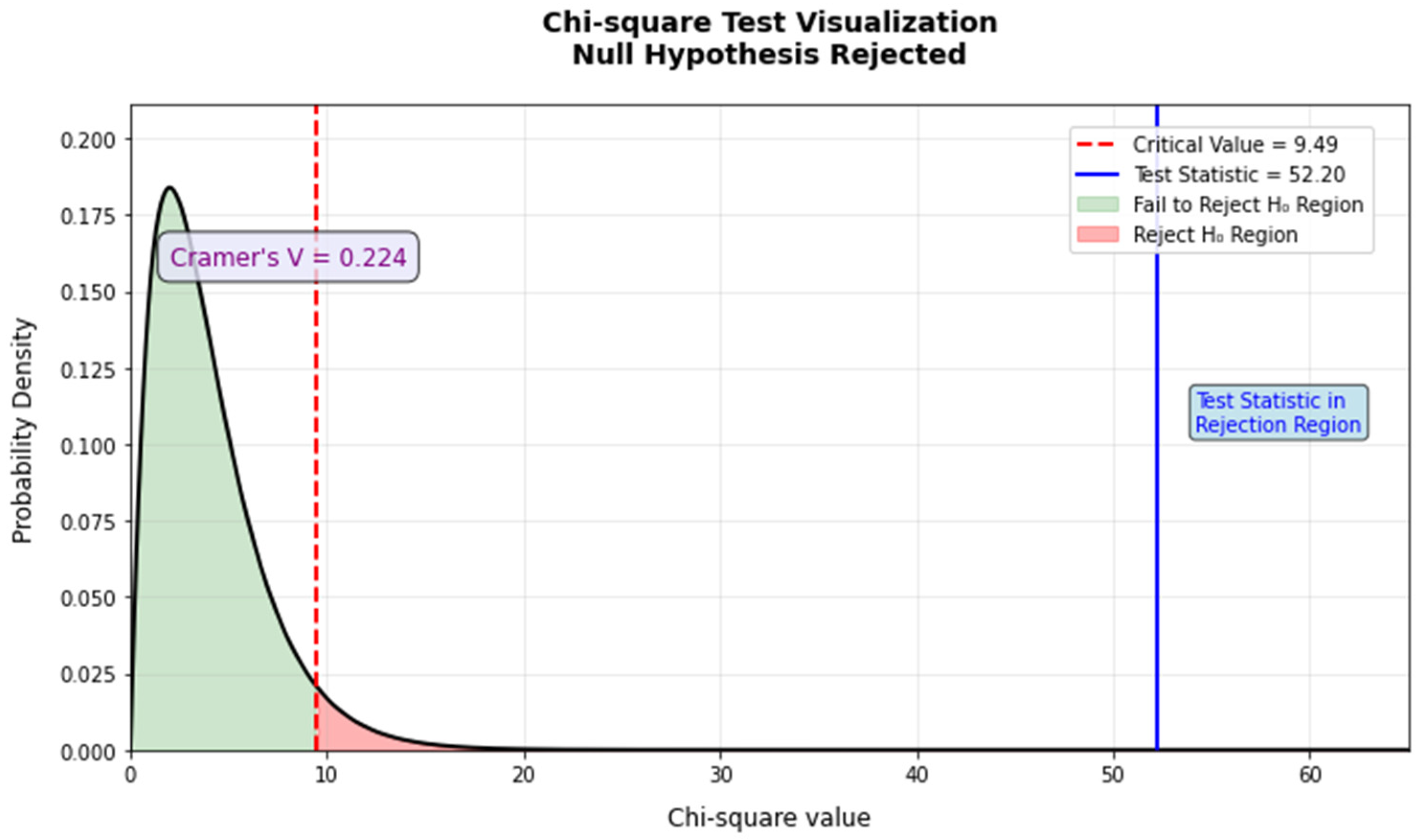

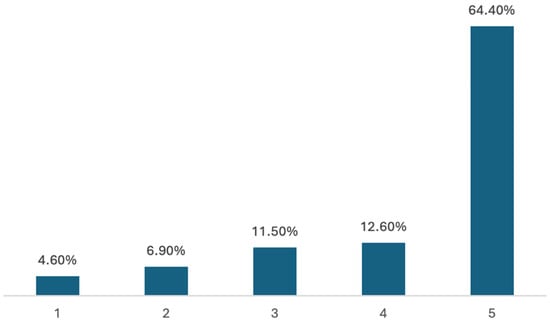

2.3.2. Barrier Interaction Analysis

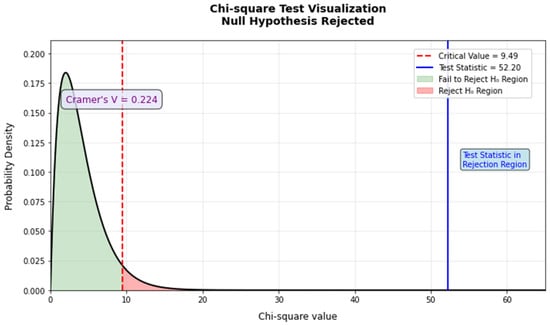

Respondents reported multiple simultaneous barriers to EV adoption, with an average of three barriers per person, with 64.4% identified three or more, indicating that adoption challenges are multifaceted rather than singular. To examine the compounding effect of multiple barriers, Cramer’s V analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between economic concerns (purchase cost) and infrastructural concerns (charging infrastructure). The analysis revealed a statistically significant association between two primary barriers (χ2 (4) = 52.21, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.224) (Figure 7). However, this analysis relied on dichotomized variables for clarity, which may oversimplify nuanced consumer perceptions and mask important threshold effects or subtle gradations in barrier intensity.

Figure 7.

Chi-squared test visualization of the relationship between station availability and intent to purchase.

As shown in Table 3, this effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.224) (Figure 7) indicates a moderate association, meaning that economic and infrastructural barriers frequently co-occur, with 51% respondents (Table 3) reporting both high-cost sensitivity and high infrastructural concern simultaneously. This clustering effect is reflected in the progressive decline of purchase intent. When we analyzed purchase intent within each subgroup of Table 3, purchase intent was 70% among respondents with no major barriers (n = 60) and declined to 51.11% among those facing both economic and financial constraints (n = 270).

Table 3.

Contingency table of economic vs. infrastructure barriers.

2.3.3. Descriptive Analysis

Quantitative survey data was analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize demographic profiles, purchase intentions, and perceptions on charging infrastructure. To test relationships between key variables, Chi-squared tests of independence were employed. For each test, the null hypothesis (H0) stated that there was no association between the two variables; the alternative hypothesis (H1) stated otherwise.

The strength of any significant associations was measured using Cramér’s V, interpreted as follows: <0.10 = negligible, 0.10–0.30 = weak, 0.30–0.50 = moderate, and >0.50 = strong.

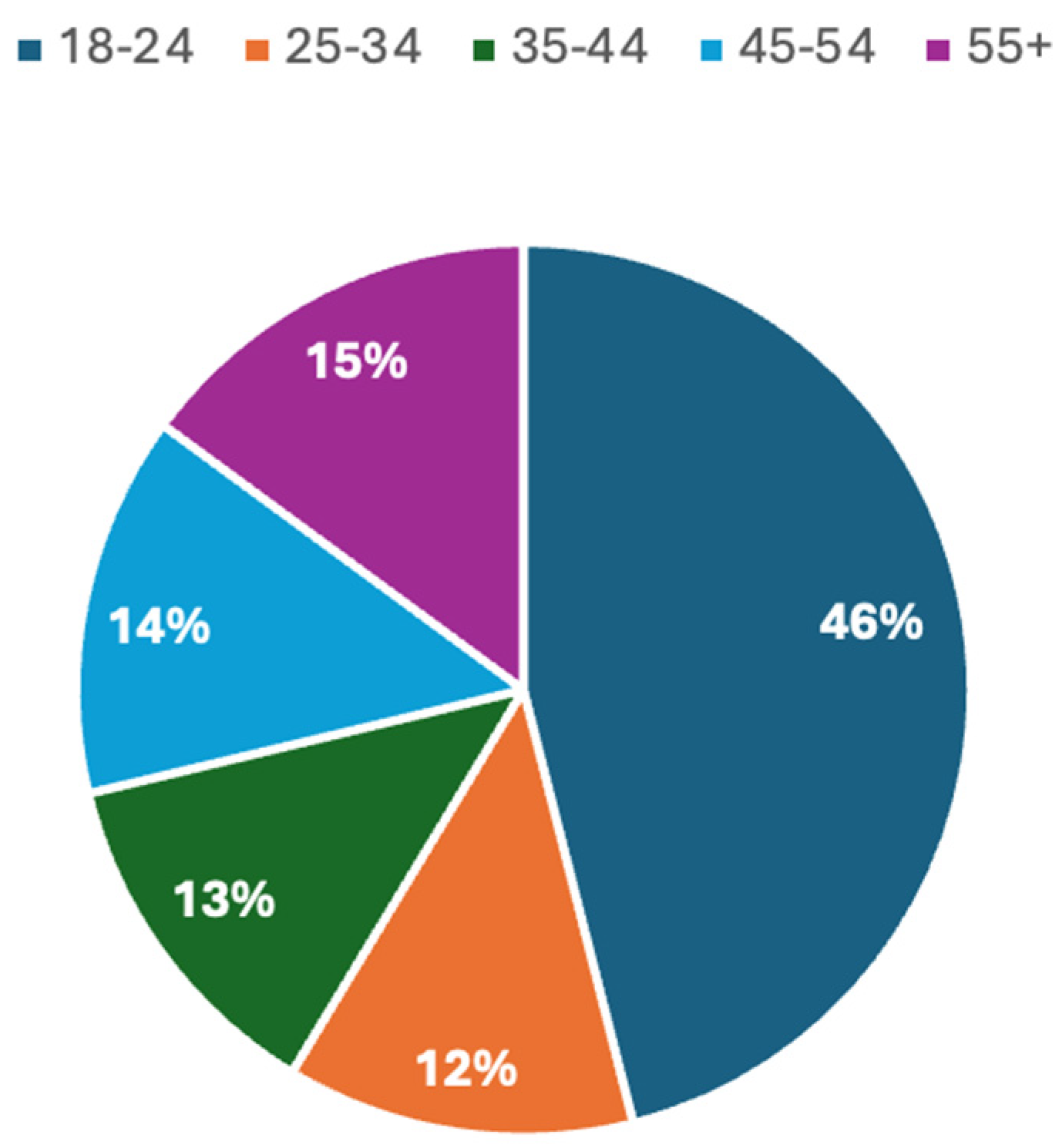

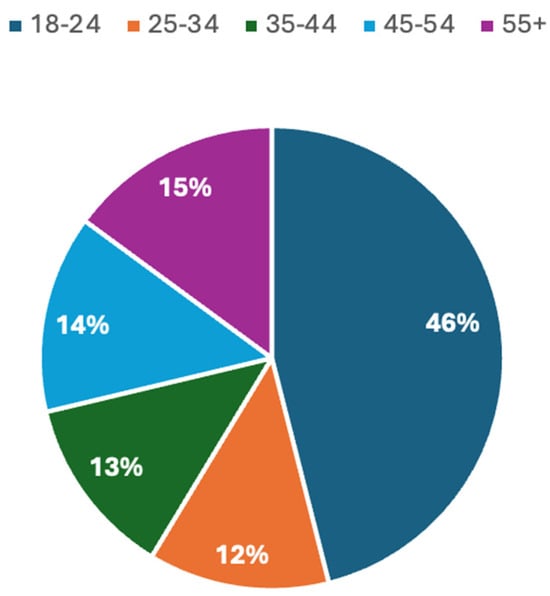

The sample consisted of 522 respondents, with 18–24 years being the largest age group (45.97%), followed by above 55 years (14.94%) and 45–54 years (13.79%) (Figure 8). Respondents aged between 25–34 and 35–44 each represented (12.64%) of the sample (Figure 8). The survey skewed toward younger participants under 25. While this limits demographic breadth, this cohort is of critical strategic importance as they represent a core segment of first-time car buyers and future promoters whose adoption is essential for achieving early market growth.

Figure 8.

Age distribution of survey respondents.

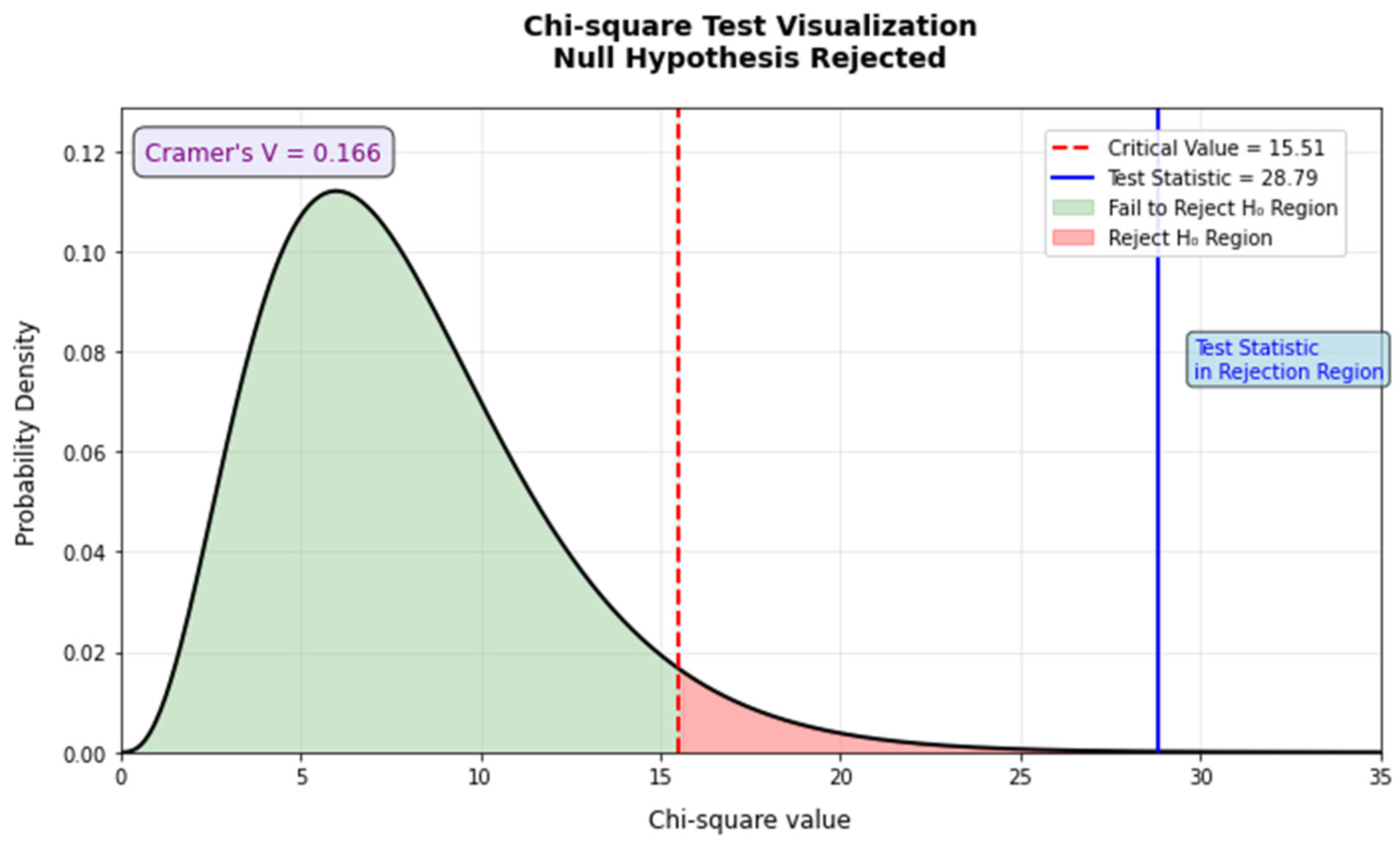

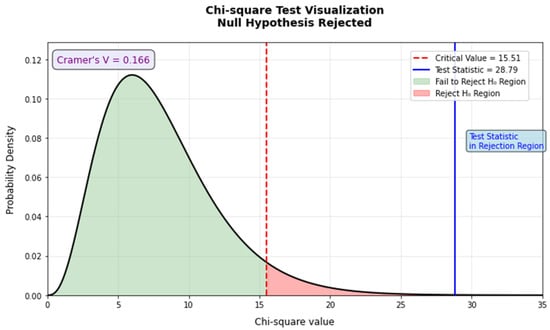

A statistically significant but weak association was found between age group and intent to purchase (χ2 (8) = 28.79, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.166). Younger respondents (18–34) expressed stronger intents to purchase compared to older groups (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Chi-squared test visualization of the relationship between age group and intent to purchase.

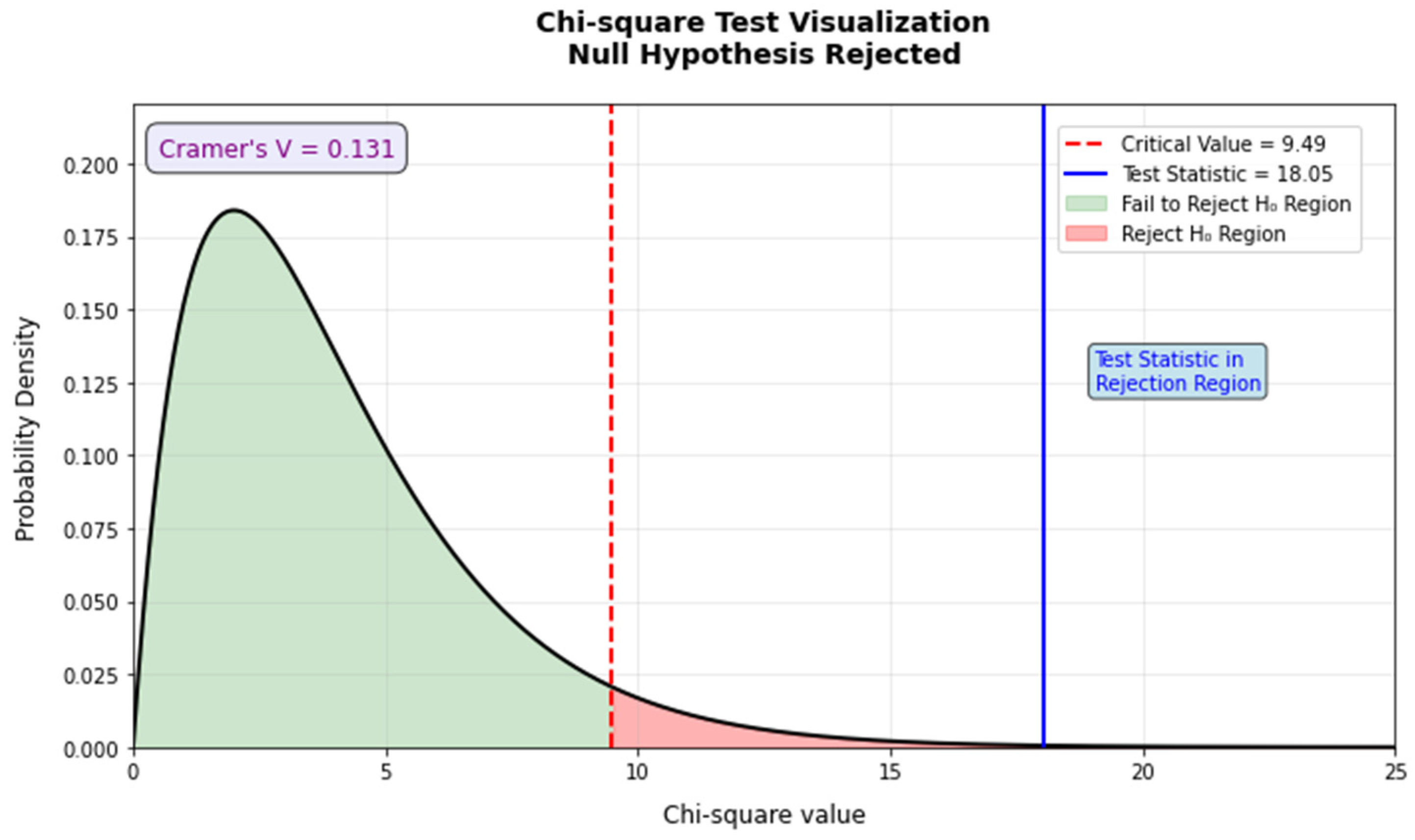

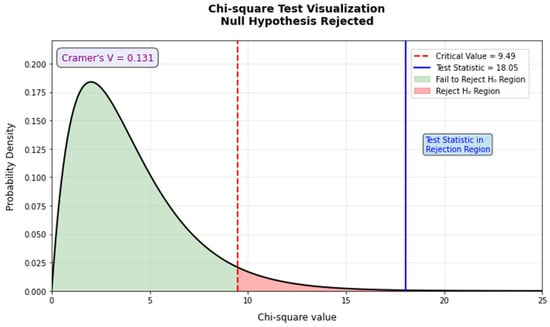

Similarly, the perceived importance of availability showed significant yet weak association with intent to purchase (χ2 (4) = 18.05, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.131). Participants who considered availability as highly important showed higher purchase intent (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Chi-squared test visualization of the relationship between availability importance and purchase intent.

The strongest association yet weakest was between reported station availability and purchase intent (χ2 (4) = 52.21, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.224). Respondents reporting high station availability were more likely to purchase (Figure 7).

In each case, the null hypothesis was rejected, suggesting that demographic and infrastructural factors strongly influence adoption intent.

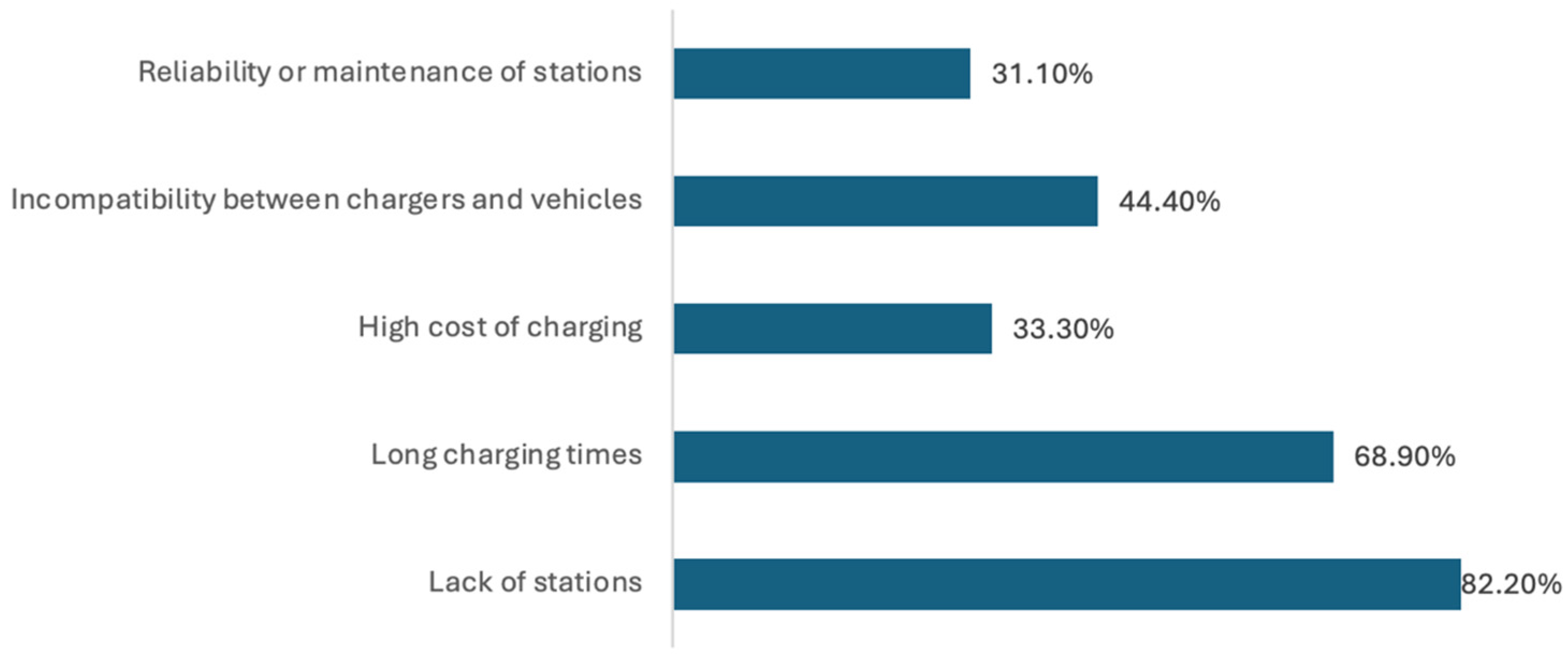

Qualitative responses were thematically coded and compared to literature-derived barrier categories. The most frequently reported issue was the lack of charging stations, especially in remote areas, with participants citing long queues, non-functioning stations, and extended travel distances to access chargers. Economic barriers were also emphasized, including the high cost of EVs and the absence of clear plans to expand charging services. Respondents further highlighted technical limitations, including long charging times, limited range, and incomplete technology. A smaller number raised concerns regarding the environmental footprint of battery production and disposal, arguing that EVs may not be as sustainable as promised. Finally, safety- and support-related challenges were noted, including the risks posed by quiet vehicles to pedestrians and the lack of competent mechanics trained to service EVs.

Finally, the study focused on perceived barriers and purchase intent rather than actual adoption behavior. This reliance on self-reported data may not fully capture unconscious bias or social desirability effects, particularly regarding environmental attitudes and purchase intentions. The high purchase intent observed in our sample, while valuable for understanding early adopter psychology, should be interpreted as ambition rather than projected behavior.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Factors Influencing Purchase Intent

The relationship between key demographics and perceptual factors, and EV purchase intent was rigorously tested using Chi-squared analyses. The findings revealed a nuanced picture of the factors associated with adoption intent in Morocco.

A statistically significant, albeit weak, association was found between age group and purchase intent (χ2 (8) = 28.79, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.166). As illustrated in Figure 9, younger generations are often early adopters of sustainable technology [30,31]. However, the weak effect size indicates that while age is a correlating factor, it alone is a limited predictor of adoption intent within the Moroccan context. The youth factor is insufficient to drive market transformation on its own; optimistic projections based solely on demographic shifts may be overstated unless concurrent structural barriers are addressed.

The analysis further revealed a significant yet weak association between the importance placed on charging availability and purchase intent (χ2 (4) = 18.05, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.131) (Figure 10). This finding aligns with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), where perceived ease of use is a precursor to adoption [25]. Participants who had actively considered infrastructure as a critical factor were more likely to intend to purchase. This can be interpreted as a conditional readiness; a segment of the market is psychologically prepared but awaits tangible ecosystem development before committing.

Most notably, the strongest observed association with purchase intent was for the variable measuring perceived station availability (χ2 (4) = 52.21, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.224) (Figure 7). This result powerfully operationalizes the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [26]; the perceived lack of infrastructure directly erodes perceived behavioral control, making the act of owning an EV seem impractical, regardless of one’s attitudes or intentions. This finding challenges a purely attitudinal approach to promoting EVs and underscores a fundamental sociotechnical principle: technological niches (EVs) cannot diffuse without significant regime level changes (infrastructure) [27]. The effect size for this perceptual variable was substantially stronger than for demographic factors, highlighting that in a constrained environment, systemic feasibility can be a more powerful driver of intent than individual characteristics.

This analysis moves the discussion beyond identifying barriers to quantifying their relative influence on consumer psychology. Morocco’s value–action gap is not primarily a failure of consumer motivation but a rational response to a deficient ecosystem. While demographics and awareness set the stage, the perceived reality of the infrastructural landscape acts as a decisive gatekeeper. This empirically validates the need for the study’s multi-dimensional framework, confirming that infrastructural and institutional dimensions are not merely contextual but are primary determinants that actively suppress the potential latent in behavioral and economic dimensions.

3.2. Demographic and Transport Behavior

The demographic profile of respondents skews heavily toward younger age groups, with over 80% aged between 18 and 34 (Figure 8). This reflects a digitally connected, environmentally conscious segment that may be more receptive to technological innovation. This aligns with global patterns where younger individuals demonstrate a greater willingness to adopt EVs [30,31].

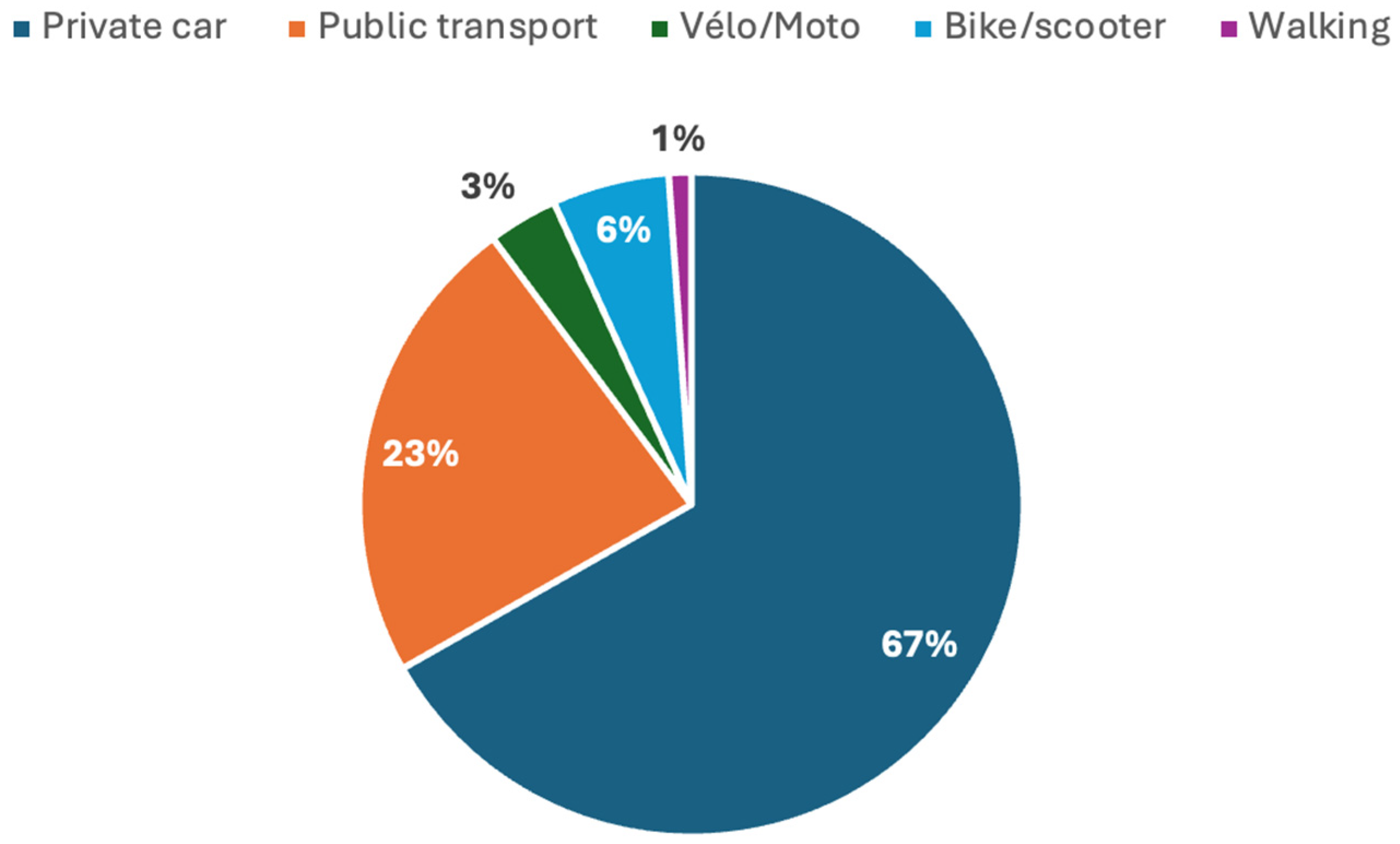

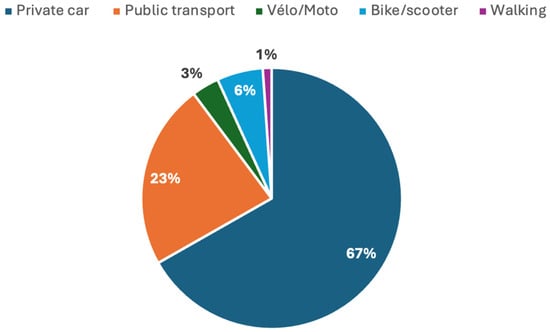

However, despite this openness, actual EV ownership among respondents is unrealized. This is evidenced by a profound value–action gap, where 43.5% of respondents had seriously considered purchasing an EV yet only 1.1% owned one. This gap cannot be explained by a lack of mobility need, as respondents rely either on personal vehicles, taxis, or motorcycles for daily commuting (Figure 11). Instead, it reveals that their mode choice is dictated by ‘cost efficiency and convenience’, a rational response to an EV value proposition that currently fails on both counts. They are not resistant to EVs; rather, they are rational consumers for whom the current economic and infrastructural context is optional and a high-risk decision.

Figure 11.

Distribution of respondents’ primary mode of transportation.

Consumer vehicle preferences further illuminate the adoption challenge. The Moroccan market is dominated by the small city cars ‘Citadines’ and ‘SUVs’ which together constituted 76.2% of new VP sales in 2024 [4]. Moroccan consumers have a tendency for practicality affordability and a degree of social status associated with larger body types. The success of the Dacia Spring, which captured 40% of the tiny BEV market, demonstrates that demand exists at the most accessible price point, but it remains an outlier in market geared towards ICE Citadines and SUVs. This preference aligns with our attitudinal segmentation; ‘Conditional Adopters’, the largest segment, prioritize cost leadership and practicality, values currently best met by the established ICE market.

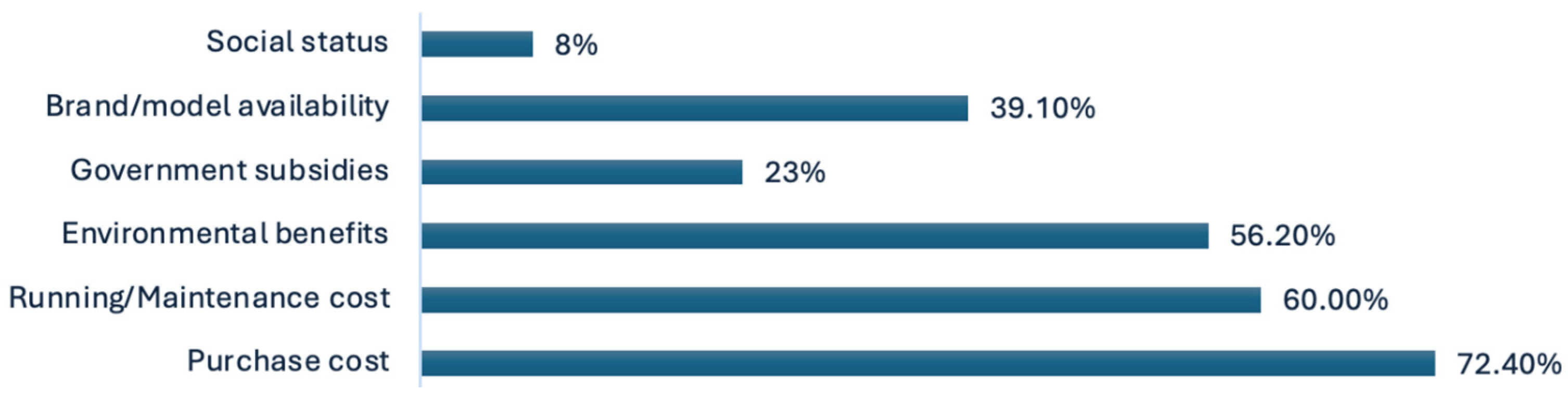

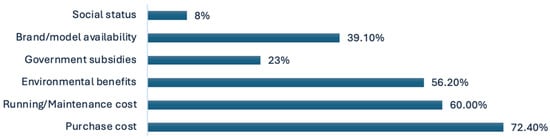

3.3. Perceptions of Economic Barriers and Benefits

The data indicates that cost remains the single most significant deterrent. Over 70% of participants stated that high upfront prices dissuade them from considering EVs (Figure 12). This data point represents a significant market failure: long-term savings are rendered irrelevant when the initial capital is beyond an average Moroccan consumer. The price gap between ICEVs and EVs is seen as unjustifiable in a country where average income levels are low and access to vehicle loans remains restricted. EVs may offer long-term fuel savings and lower maintenance costs; however, the majority focuses on short-term affordability.

Figure 12.

Factors influencing electric vehicle purchase decisions.

The survey’s finding that cost is the paramount barrier is substantiated by a detailed total cost of ownership (TCO) analysis and the structure of the vehicle market. When comparing vehicles on a like-for-like basis, the most affordable new BEV is priced nearly twice as high as a comparable new economy car. This disparity is exacerbated over the vehicle’s lifetime, with TCO studies indicating BEVs carry a 55% higher lifetime cost, driven by high purchase price and accelerated depreciation, at approximately 15.5% annually for BEVs vs. 13.2% for ICEVs [42]. This financial reality is decisive in a market where used car sales dominate, and the used EV segment is virtually negligible. A snapshot from a major online marketplace, AVITO, reveals approximately 290 EV listings including BEVS. Examples from those listings include a 2025 Dacia Spring at 230,000 MAD and a BYD Seal at 320,000 MAD. For a median-income household, this financial reality positions even the most basic EV as a luxury good. A middle-income professional, such as a teacher earning 6000–8000 MAD/month, could afford a home valued at approximately 212,797 MAD. When housing stretches budgets, secondary assets purchase like vehicles must be highly cost-conscious. The choice of reliable ICE and a used EV is therefore not just technological, but it is a choice between mobility and financial stability, confirming that EV value proposition has yet to penetrate the critical second-hand sector.

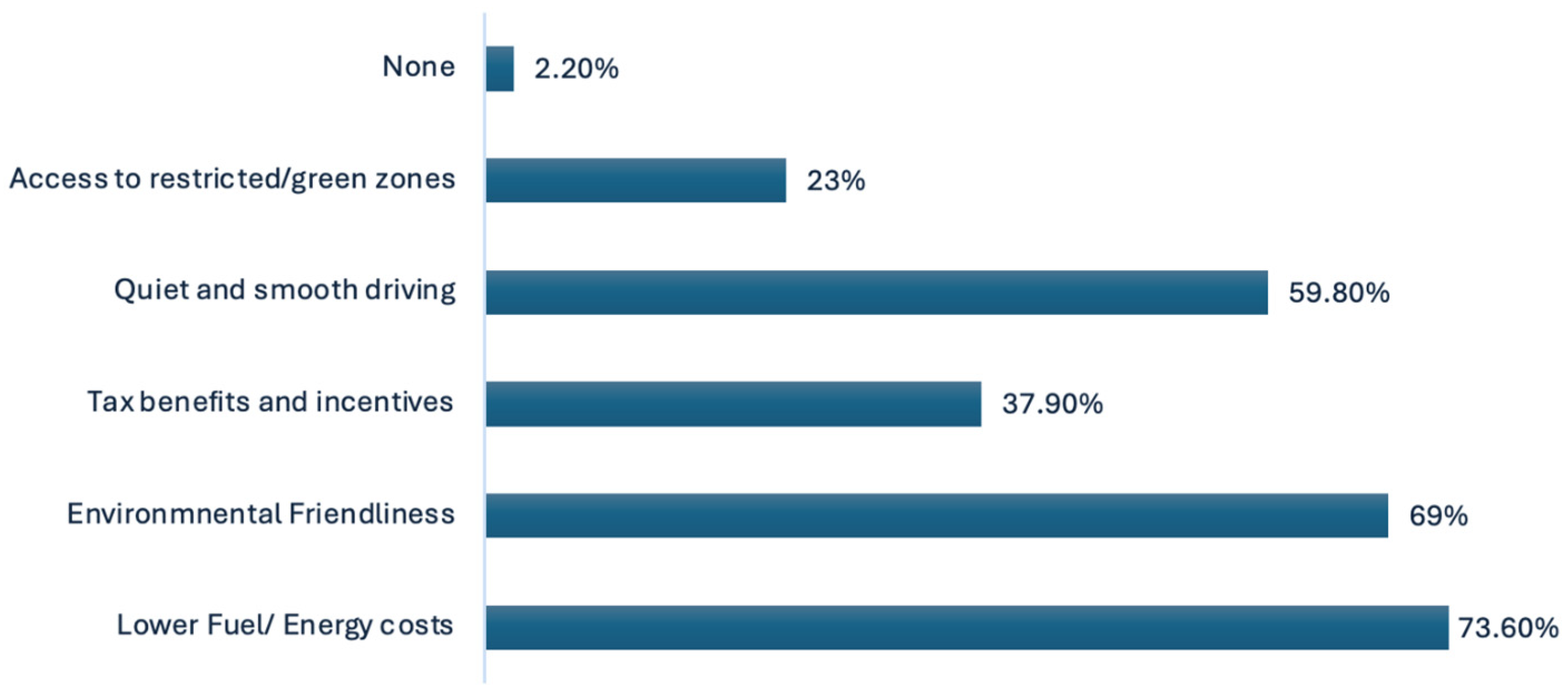

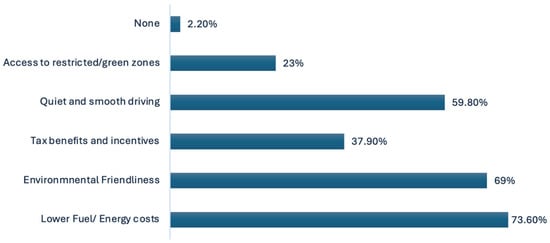

Environmental advantages, such as reduced emissions, better air quality, and lower fuel dependency, were generally recognized by most respondents (Figure 13), though this understanding was overshadowed by the immediate financial constraints. Notably, some respondents expressed doubts about the environmental legitimacy of EVs due to battery recycling issues and the ecological impact of lithium extraction, with some believing the ecological damage from battery production outweighed the operational benefits. This skepticism, though a minority view, highlights the importance of transparent lifecycle assessments and consumer education.

Figure 13.

Perceived advantages of EV ownership.

3.4. Perceptions of Infrastructural Barriers and Preferences

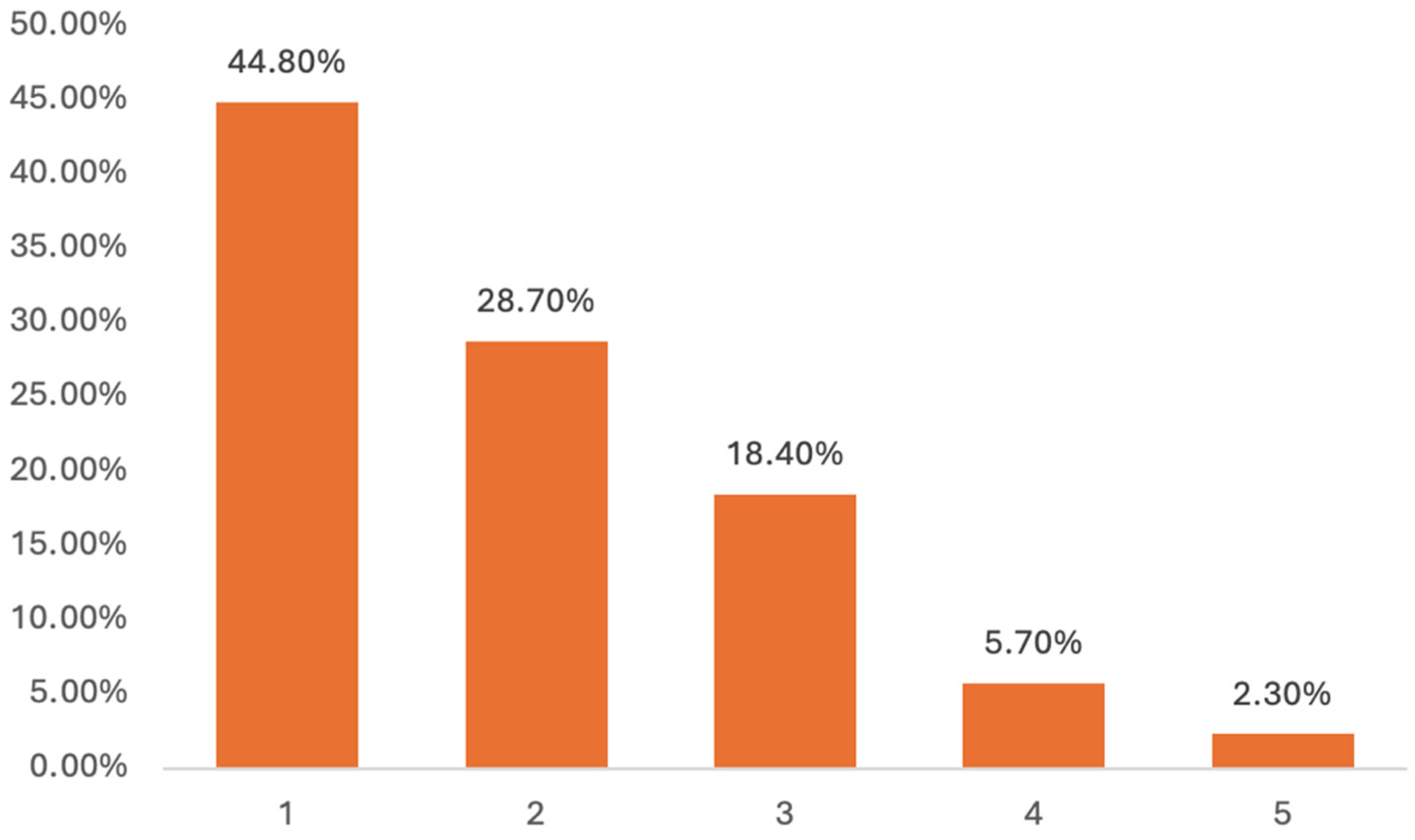

Infrastructural inadequacy emerged as another primary barrier to adoption. An overwhelming majority views Morocco’s charging infrastructure as either “insufficient” or “poorly distributed” (Figure 14), indicating a social equity and a geographic problem. Respondents in peri-urban and rural areas reported near-total inaccessibility. This geographic disparity risks creating a two-tiered system where electric mobility is for the privileged and connected elite.

Figure 14.

Rate the availability of public EV charging stations in Morocco.

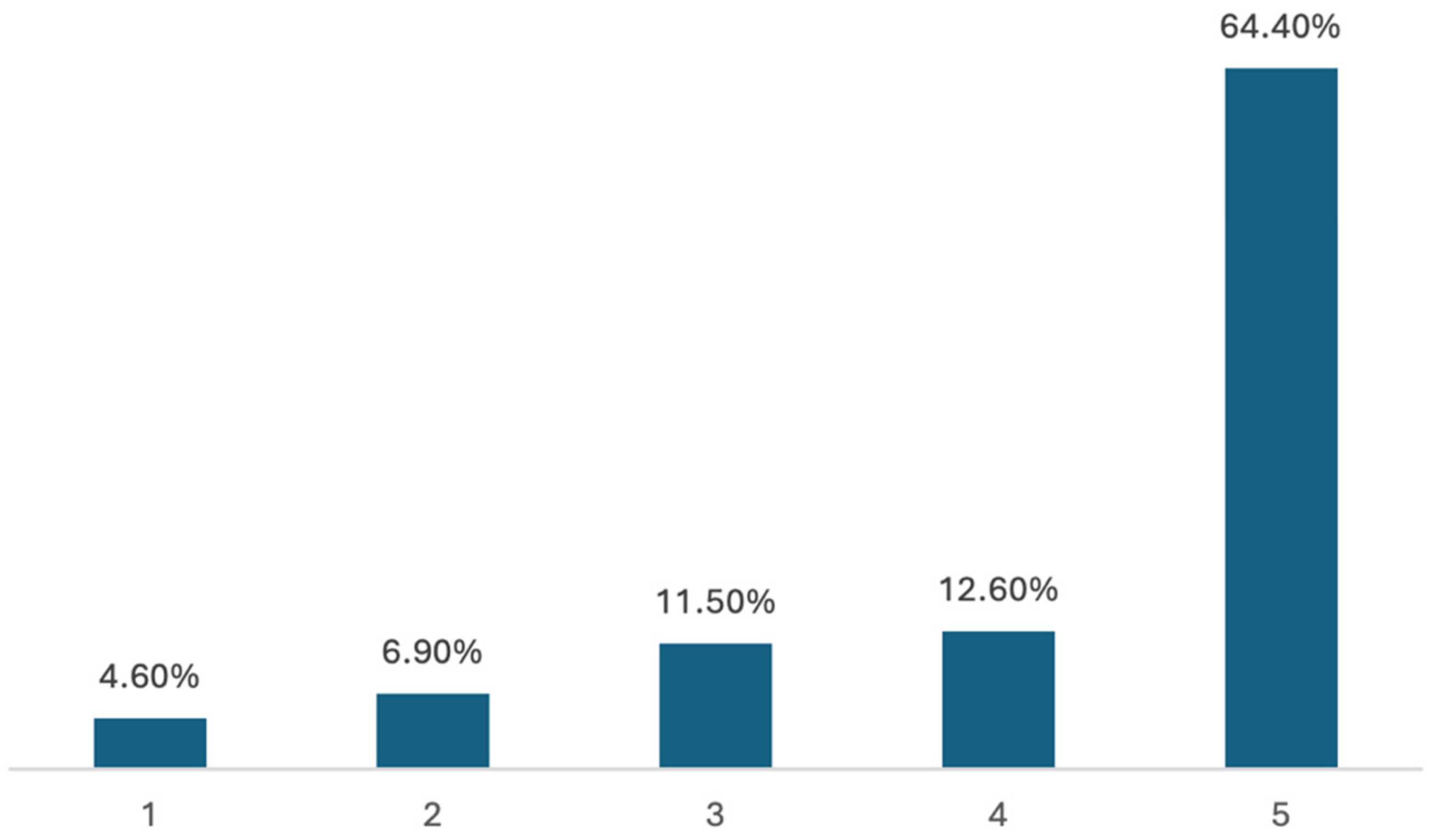

Consequently, as Figure 15 demonstrates, the availability of charging infrastructure is not just a preference but a critical precondition to adoption for most respondents. Statistical analysis confirms a significant, but weak association between perceived station availability and purchase intent (χ2 (4) = 52.21, p < 0.05, Cramér’s V = 0.224) (Figure 9), indicating that infrastructural perceptions are a powerful driver of consumer behavior. These infrastructural deficits severely undermine perceived behavioral control, making adoption an impractical choice for most consumers regardless of their environmental attitudes.

Figure 15.

Importance of charging station availability to EV purchase decision.

While there is a strong expressed interest in home charging solutions, this interest is tempered by concerns about installation complexity, costs, and compatibility with existing residential electrical systems. The feasibility is particularly uncertain among apartment dwellers. This barrier is significant given Morocco’s urban housing landscape, where a high homeownership rate of 66.4% in urban areas includes apartment buildings without dedicated parking or garages [43]. For the 25.7% constituting tenants [43], installing a private charging point is often legally and logistically impractical. This constraint undermines EV value proposition, forcing potential adopters to depend entirely on a public network, perceived as insufficient. Consequently, the operational convenience and cost-saving benefit of overnight charging remains inaccessible to a large segment of the urban population.

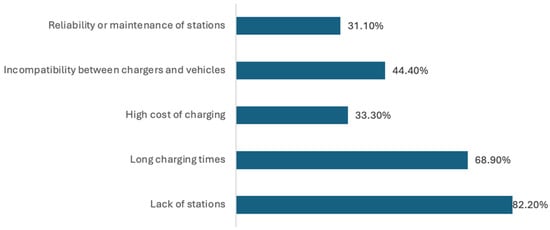

Other issues revolved around cost, time, and reliability of charging points. As illustrated in Figure 16, these concerns undermine the ease-of-use pillar of the Technology Acceptance Model and complete the picture of a complex and undependable ecosystem.

Figure 16.

Concerns regarding the charging infrastructure.

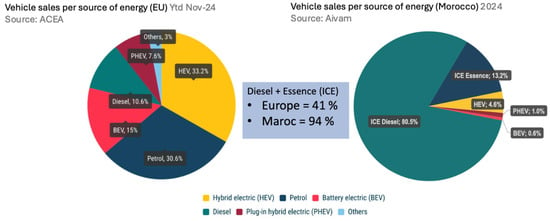

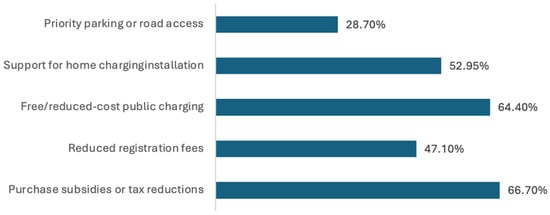

3.5. Policy Expectation and Social Influences

Governmental support was recognized as essential for the growth of EV adoption. Respondents favored financial interventions, identifying purchase subsidies and tax incentives as most effective (Figure 17), followed by investment in free charging and public awareness campaigns. These findings shed light on the public’s unawareness of existing incentives. This gap indicates a breakdown not only in policy implementation but also in communication strategies. Participants called for more transparency, clearer eligibility criteria for incentives, and a user-friendly platform for accessing EV-related information.

Figure 17.

Government incentives encouraging EV adoption.

There was also broad support for transitioning public fleets to EVs, as respondents believed this would increase the visibility, legitimacy, and trust in the technology. Such moves would demonstrate government commitment and lead by example.

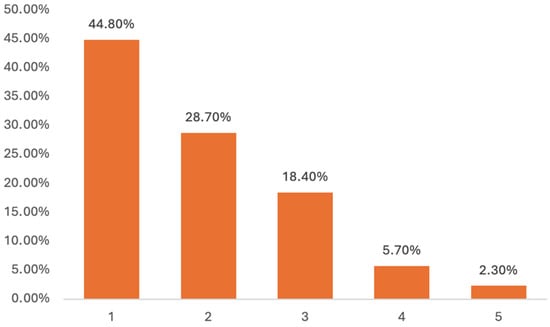

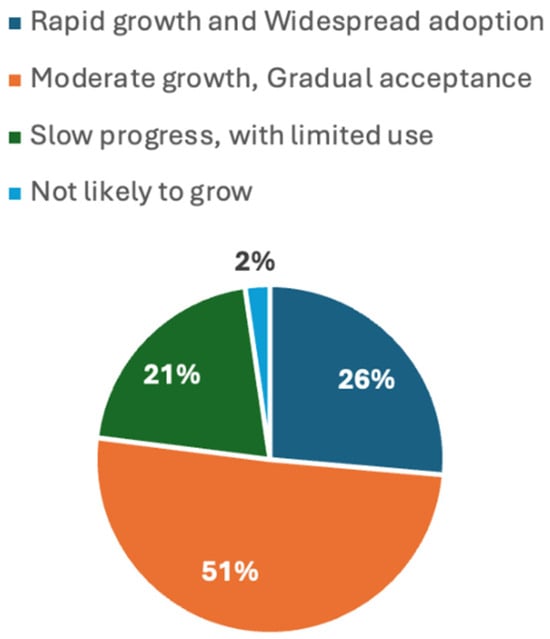

This cautious optimism is tempered by realistic expectations. Most respondents foresee slow to moderate EV adoption over the next decades in Morocco, with gradual acceptance rather than rapid (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Expected growth of EVs in Morocco over the next decade.

This tempered outlook and split decision on recommending EV reflects symptoms of weak social proof and an established lack of trust. Many participants expressed cautious support, conditional on the affordability and availability of infrastructure. Others were hesitant due to a lack of real-world knowledge, mistrust in the longevity of EVs, or concerns over battery fires and resale value. ICEs hold a persistent status in society and are perceived as aspirational symbols. This contrasts with a utilitarian perception of EVs and reveals a socio-cultural barrier that top-down strategies and supply-push models failed to address.

3.6. Response Bias and Contradiction

Response bias was observed in the survey data; a segment of respondents who expressed no personal interest in purchasing an EV were likely to recommend one to others. This apparent contradiction can be attributed to several factors:

- Social Desirability Bias [45]: Respondents may have felt pressured to endorse EVs as the correct or socially responsible choice by the end of the survey, even if their personal circumstances or beliefs did not align with adoption. This reflects their environmental awareness without their financial commitment.

- The Value–Action Gap: This refers to the gap between one’s expressed beliefs and actual behaviors especially in sustainable contexts [46]. These respondents perceive the abstract benefit of EVs for others but not their practical application for themselves.

This bias is not an artifact of the survey; it is reflected in national market reality. The AVIAM 2024 study provides macro-level validation: while 42% of respondents considered purchasing, the actual national BEV adoption rate remained at 0.6%. This significant disparity between intention and action at both the micro (survey) and the macro (national sales) levels demonstrates that positive sentiment regarding the technology undermines its widespread adoption due to persistent structural and psychological barriers. Consequently, the survey data should be interpreted with caution, as responses reflect ambition rather than projected behavior.

3.7. Outlook and Recommendations Based on Attitudinal Segmentation

Participants fell broadly into three segments:

- Enthusiasts (approx. 20%): These participants were highly motivated by environmental values and long-term cost benefits, and would adopt EVs if prices dropped or subsidies increased.

- Conditional Adopters (approx. 50%): These participants were open to the idea but constrained by cost, infrastructure, and perceived risks. They were likely to convert if barriers are addressed.

- Resistant Skeptics (approx. 30%): These participants were unlikely to adopt in the near term due to mistrust, status perception, or misinformation.

Understanding these user profiles is key to designing differentiated outreach campaigns. While “enthusiasts” can be leveraged as early adopters and brand ambassadors, “conditional adopters” represent the bulk of the latent market and should be the primary target of short- to medium-term policies. For the “resistant skeptics”, consistent education, community engagement, and exposure to successful EV users may help reduce doubts over time.

3.8. Implications for Policymakers and Industry

The results confirm that Morocco’s EV transition cannot rely solely on infrastructure development or industrial growth. Adoption will require holistic interventions, including the following:

- Introduce targeted subsidy reform: The government should pioneer EV purchase tax credits aimed at middle-income consumers, a high-impact lever that is proven internationally but not yet embedded in Morocco’s climate finance strategy [47].

- Scale Green Loans and Guarantee Schemes: Morocco should aggressively deploy finance and de-risk tools. Tamwilcom’s Green Invest program, which financed only seven projects for 26.4 million MAD in 2023 [48], has untapped potential for expansion toward EV buyers and charging infrastructure SMEs. Similarly, the EVCAT guarantee instrument [47,48] should be explicitly extended to cover EV purchase loans to stimulate broader market participation.

- Mobilize Green Capital for Charging infrastructure: Morocco’s sovereign Green Bond Framework under AMMC [49], already used in seven successful issuances, provides an established mechanism to finance a national charging network, giving the priority to underserved and peripheral regions to ensure special equity and support long-term demand growth.

- Mandate EV readiness regulations for residential and commercial buildings: Led by AMEE, EV-ready standards for residential and commercial buildings would prevent costly future retrofits while advancing the sustainable construction objectives of the National Sustainable Development Strategy (SNDD).

- Establish a Carbon Price Signal: To improve the cost-competitiveness of EVs over ICEs, Morocco should initiate preparatory studies on carbon taxation or the cap-and-trade system in the transport sector [47].

- Implement a National ‘E-Mobility’ Awareness Strategy: Morocco should launch a coordinated national awareness campaign under the SNDD [50] to reshape consumer perceptions, clarify the total cost of EV ownership, and build trust. Demonstration projects, such as electrifying government fleets or test-driving initiatives, would increase public familiarity and confidence.

A synchronized approach involving government, industry, energy providers, and civil society is essential to bridge the awareness–action gap and ensure a socially inclusive EV transition.

4. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence of the multifaced barriers inhibiting EV adoption in Morocco, contextualizing the production–adoption paradox within a broader sociotechnical framework. The analysis confirms that Morocco’s linear domestic adoption stems from a convergence of financial, infrastructural, behavioral, and institutional impediments. These findings situate Morocco within a growing narrative observed in emerging economies: technological availability and export-oriented industrial success do not automatically translate into domestic market transformation.

The paper reinforces the complexity of EV adoption in emerging economies. Technological solutions must be integrated within nuanced social, economic, and infrastructural ecosystems. Morocco’s case exemplifies the production–adoption paradox, having an advanced automotive manufacturing base and an ambitious renewable energy agenda while struggling with negligible domestic EV adoption. The misalignment between the national production capacity and consumer demand highlights both structural and behavioral challenges. EV manufacturing is scaling up due to foreign investment and export potential, yet domestic uptake is limited by high costs, insufficient infrastructure, and consumer skepticism. This divergence between the global trend and local uptake is directly explained by the barriers identified in our survey.

Our findings reveal that while Morocco shares common barrier themes with its regional peers, its specific context creates a uniquely pronounced adoption crisis. The dominance of high upfront costs and infrastructural deficits aligns with challenges documented in Egypt [5] and Jordan [6]. However, Morocco’s situation is distinguished by its production–adoption paradox. Unlike these nations, Morocco possesses a robust, globally integrated automotive manufacturing base complemented by landmark investments in the EV battery value chain [13,14,15]. This creates a critical divergence: the country is a documented supply-side success story existing in parallel with a profound demand-side failure. This contrast underscores a vital lesson for emerging economies: industrial policy and foreign direct investment, while crucial for economic development, are insufficient catalysts for domestic market transformation without parallel, targeted demand-side interventions.

The case of Norway as global leader in electric vehicle adoption, despite having no major car industry of its own, highlights a crucial lesson for Morocco. Norway’s success, where over 80% of new cars are electric, was achieved not by manufacturing vehicles but by creating irresistible conditions for consumers. For decades, the government has applied a consistent and appealing package of financial incentives, notably exemption from heavy taxes [6,51], which has made EVs a rational and appealing choice. This strategy, focused entirely on stimulating demand, has proven effective not through organic market growth, but through deliberate and sustained policy intervention. Morocco’s situation has always focused on becoming a manufacturer hub, and it has successfully built a supply-push model for export. It has relied on organic market growth while neglecting the consumer incentives needed to create demand-pull at home. This contrast reveals that a strong automotive industry does not automatically create a domestic market for electric cars; thus, this success will continue in isolation from its adoption crisis.

Furthermore, our statistical analysis adds a novel, quantitative approach to this comparative study. The findings perceived infrastructure availability as a stronger corelate of purchase intent than demographic factors like age, a claim that challenges assumptions formed in studies in wealthier nations, where a basic level of infrastructure is taken for granted. Morocco’s case demonstrates that systemic feasibility outweighs individual predisposition. Therefore, prioritizing policy interventions in similar emerging economies may be a more powerful initial lever than demographic targeted marketing.

Our results extend the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to contexts defined by resource constraints in emerging economies. While TPB applications in developed countries often treat ‘perceived behavioral control’ as a function of individual self-efficacy or knowledge [26], our study demonstrates that in Morocco, perception is a rational assessment of external systemic failures. The moderate association between infrastructure availability and purchase intent provides quantitative evidence that control is not an internal psychological state, but a reflection of objective ecosystem readiness. This reframes the construct for emerging economies, as ‘perceived behavioral control’ shifts from being a question of ‘Can I, as an individual, use this technology?’ to a judgment of ‘Is the surrounding system reliable and accessible enough for me to depend on it?’.

The Multi-level Perspective (MLP) provides the essential macro-framework for understanding sociotechnical transitions. Our study illuminates the specific frictions preventing a transition in Morocco. The country exhibits strong landscape pressures and a flourishing niche EV innovation. Yet, the sociotechnical regime of ICE transport remains powerfully locked in. Our four-dimensional framework diagnoses this stagnation: high EV costs uphold the regime’s economic advantage, while sparse infrastructure and fragmented governance block the EV niche from gaining necessary traction. This reveals a critical policy insight: a successful transition requires active reconfiguration of the regime itself by dismantling key consumer barriers, not merely nurturing innovations or relying on external pressures [27].

The statistical analysis of survey responses further confirms the systemic view. The weak strength of the observed associations (Cramér’s V ranging from 0.131 to 0.224) is itself a meaningful finding. It underscores that the decision to adopt EVs in Morocco is not dominated by any single demographic or perceptual factor in isolation. Instead, adoption intent appears to be a function of a complex constellation of overlapping barriers. This supports our central thesis that the production–adoption paradox is a system-level failure, where no one intervention will be a silver bullet. The low effect sizes suggest that stimulating demand will require coordinated strategy that simultaneously addresses financial, infrastructural, and social barriers.

Survey participants expressed a high degree of environmental awareness, yet this rarely translated into action due to the financial burden of EV ownership and limited public trust in the technology. These insights echo findings from India, South Africa, and Southeast Asia, where affordability and access dominate the list of adoption barriers [28,34,37].

Cost remains the most significant hurdle in Morocco. The high upfront price of EVs relative to average income levels discourages potential buyers, despite their long-term savings from reduced fuel and maintenance expenses. Without targeted subsidies, low-interest financing, or price reform strategies, mass adoption will remain aspirational. Equally pressing is the inadequacy of charging infrastructure, which is geographically skewed toward urban centers. This concentration reinforces range anxiety and marginalizes rural and peri-urban populations. Infrastructure development must be regionally inclusive and accompanied by regulatory support for residential charging stations, particularly in multi-unit dwellings.

Beyond infrastructure and economics, cultural perceptions and social norms play an underappreciated role. ICE vehicles are still regarded as status symbols in Morocco, while EVs are viewed with suspicion or considered utilitarian. Similar dynamics have been observed in Eastern Europe and parts of Asia, where EVs lack aspirational appeal [23,37]. This requires a cultural shift, possibly driven by targeted marketing, public campaigns, and the visible adoption of EVs in government fleets. Elevating the symbolic value of EVs could accelerate normalization.

Policy fragmentation remains another critical constraint. Survey data revealed limited public knowledge of existing incentives, suggesting both weak communication and fragmented governance. Unlike countries with centralized EV policies, Morocco lacks an integrated strategy or coordinating body. Institutional alignment and the formation of a national EV task force could improve policy coherence, infrastructure planning, and public engagement.

The segmentation of survey respondents into enthusiasts, conditional adopters, and skeptics provides a practical framework for targeting interventions. Enthusiasts are early adopters who can serve as role models. Conditional adopters are the critical mass who need tangible support, such as infrastructure expansion, affordability programs, and awareness efforts. Skeptics highlight the underlying socio-psychological resistance, calling for long-term trust-building measures. Trust must be cultivated through transparency, test-driving initiatives, peer recommendations, and community-led demonstration projects.

Ultimately, single-point interventions are insufficient. Morocco’s EV transition requires a holistic, multi-sectoral strategy that addresses affordability, accessibility, social acceptance, and institutional readiness. Policymakers should link EV goals with the broader sustainability agenda, ensure equitable infrastructure development, and engage civil society in designing and delivering solutions. The findings point toward a broader lesson: technical readiness is necessary but not sufficient; fostering a favorable ecosystem through integrated, inclusive, and participatory approaches is essential to accelerating EV adoption in emerging economies.

Limitations and Future Research

The findings of this study must be interpreted within the broader context of its methodological scope. The primary data, while offering valuable insights into a strategically important segment of digitally literate, potential early adopters, is not fully representative of all socio-economic groups in Morocco due to its urban and educated skew. Future research should therefore expand sampling to include rural and lower-income population to validate and generalize these findings.

Furthermore, the pairwise analysis of barriers, while revealing significant interactions, did not explore higher-order combinations between barriers simultaneously due to sample size constraints. The quantitative results are to be seen as inferences highlighting areas of friction, rather than providing generalized and definitive truths. Future research could extend to more complex statistical models to understand the compounded effects of multiple barriers.

Finally, the survey methodology was limited in its ability to capture the nuanced social and cultural perceptions underlying adoption. The data suggests a utilitarian stigma associated with EVs in Morocco. This contrasts with their status symbol image in markets like the U.S. and China, a difference likely influenced by the types of EV available locally. Further research should qualitatively examine Moroccan consumer behavior in great depth to gain nuanced insights into the roots of this resistance, including the complex social meaning, brand perceptions, and the low signaling status associated with vehicle ownership.

5. Conclusions

Morocco’s EV ecosystem contains a compound structural and behavioral trap. Its key challenges are structural, including EVs’ high cost, a credibility gap, and insufficient infrastructure. In contrast, adoption in industrialized countries is often slowed by established legacy systems. Although environmental awareness is high, the topic has yet to gain widespread adoption, particularly among younger generations. Consumer behavior, as advocated by the literature, is heavily impacted by cost-effectiveness and convenience aspects; hence, environmental ideals are typically substituted.

5.1. Economic and Industrial Measures

High upfront costs and limited financing remain the strongest deterrents. This entails implementing narrowly targeted subsidies and flexible financing schemes for the low- and middle-income populations. As evidenced by programs such as India’s Production-Linked Incentives (PLI), cost barriers may ultimately require industrial policy intervention. Encouraging domestic assembly or localized battery production could reduce import dependency, lower prices, strengthen Morocco’s automotive value chain, and boost employment.

5.2. Infrastructure and Energy System Measures

Charging infrastructure remains urban-centric and insufficient. Its rapid deployment along rural areas as well as highways is essential. In remote regions, off-grid or hybrid solar-powered charging stations could support electrification while leveraging Morocco’s renewable energy potential. Strengthening grid stability and coordinating infrastructure responsibilities across agencies would address fragmentation and accelerate rollout.

5.3. Behavioral and Social Measures

The persistent value–action gap reflects cultural, psychological, and status-related barriers. Skepticism towards technology, the low symbolic value of EVs, and familiarity with ICE vehicles shape consumer choices. To shift these perceptions, Morocco should encourage experiential programs such as EV-sharing pilots, test-drive campaigns, and national public education initiatives. These measures can foster confidence, normalize EV usage, and reduce anxieties regarding range and reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and H.E.A.; methodology, S.M. and H.E.A.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M., H.E.A. and S.A.-M.; formal analysis, S.M. and H.E.A.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M., H.E.A. and S.A.-M.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, H.E.A. and S.A.-M.; and project administration, H.E.A. and S.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved an anonymous, minimal-risk survey that did not collect personal, identifiable, or sensitive data. The research was conducted in full accordance with Moroccan Law No. 09-08 governing the protection of personal data, under which such studies are exempt from formal ethics committee declaration or authorization.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| CDG | Caisse de Dépôt et de Gestion (Moroccan state-owned investment group) |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle |

| IRA | Inflation Reduction Act (U.S Legislation) |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| OCP | Office Chérifien des Phosphates |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Strategies for Affordable and Fair Clean Energy Transitions; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Li, P.; Xia, Z.; Wu, R.; Cheng, Y. Life cycle carbon footprint of electric vehicles in different countries: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 122063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Gou, Z.; Gui, X. How electric vehicles benefit urban air quality improvement: A study in Wuhan. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association des Importateurs de Véhicles au Maroc. Performances du Marché Automobile au Maroc en 2024; AIVAM: Casablanca, Morocco, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, H.; De Santis, M.; Bayoumi, E.H.E. Electric Vehicle Adoption in Egypt: A Review of Feasibility, Challenges, and Policy Directions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samawi, G.A.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Jreissat, M.; Kandas, A. Advancing Sustainable Development in Jordan: A Business and Economic Analysis of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the Transportation Sector. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Transport Forum. Decarbonising Morocco’s Transport System Charting the Way Forward; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prakhar, P.; Jaiswal, R.; Gupta, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Electric vehicles in transition: Opportunities, challenges, and research agenda—A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amachraa, A. Driving the Dream: Morocco’s Rise in the Global Automotive Industry; Policy Center for the New South: Rabat, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kasraoui, S. Morocco to Increase Electric Vehicle Production Capacity by 53% in 2025; MWN: Rabat, Morocco, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- SNECI Group. Morocco: A Rising Star in the Electric Car Industry. SNECI Group. 2023. Available online: https://www.sneci.com/en/morocco-a-rising-star-in-the-electric-car-industry/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Herve. Morocco Passes the 10,000 Electric Vehicle Mark. CAPMAD. 2025. Available online: https://www.capmad.com/others-en/morocco-passes-the-10000-electric-vehicle-mark/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- MAP. COBCO Company Inaugurates 1st Manufacturing Unit for Lithiurmion Battery Materials with 40,000 Tons Capacity in Jorf Lasfar. MAP. 2025. Available online: https://www.mapnews.ma/en/actualites/economy/cobco-company-inaugurates-1st-manufacturing-unit-lithiurm-ion-battery-materials (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- LG. LG Chem Teams Up with Huayou Group to Build LFP Cathode Plant in Morocco; LG: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CDG. Signature d’un Mémorandum d’Entente Entre le Groupe CDG et la société Gotion High-Tech Pour L’accompagnement du Projet de Gigafactory de Batteries au Maroc; CDG: Rabat, Morocco, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OCP Group. OCP Group Launches a $13 Billion Green Investment Strategy. OCP Group. 2022. Available online: https://www.ocpgroup.ma/news-article/ocp-group-launches-its-new-green-investment-program-2023-2027 (accessed on 21 September 2025).