1. Introduction

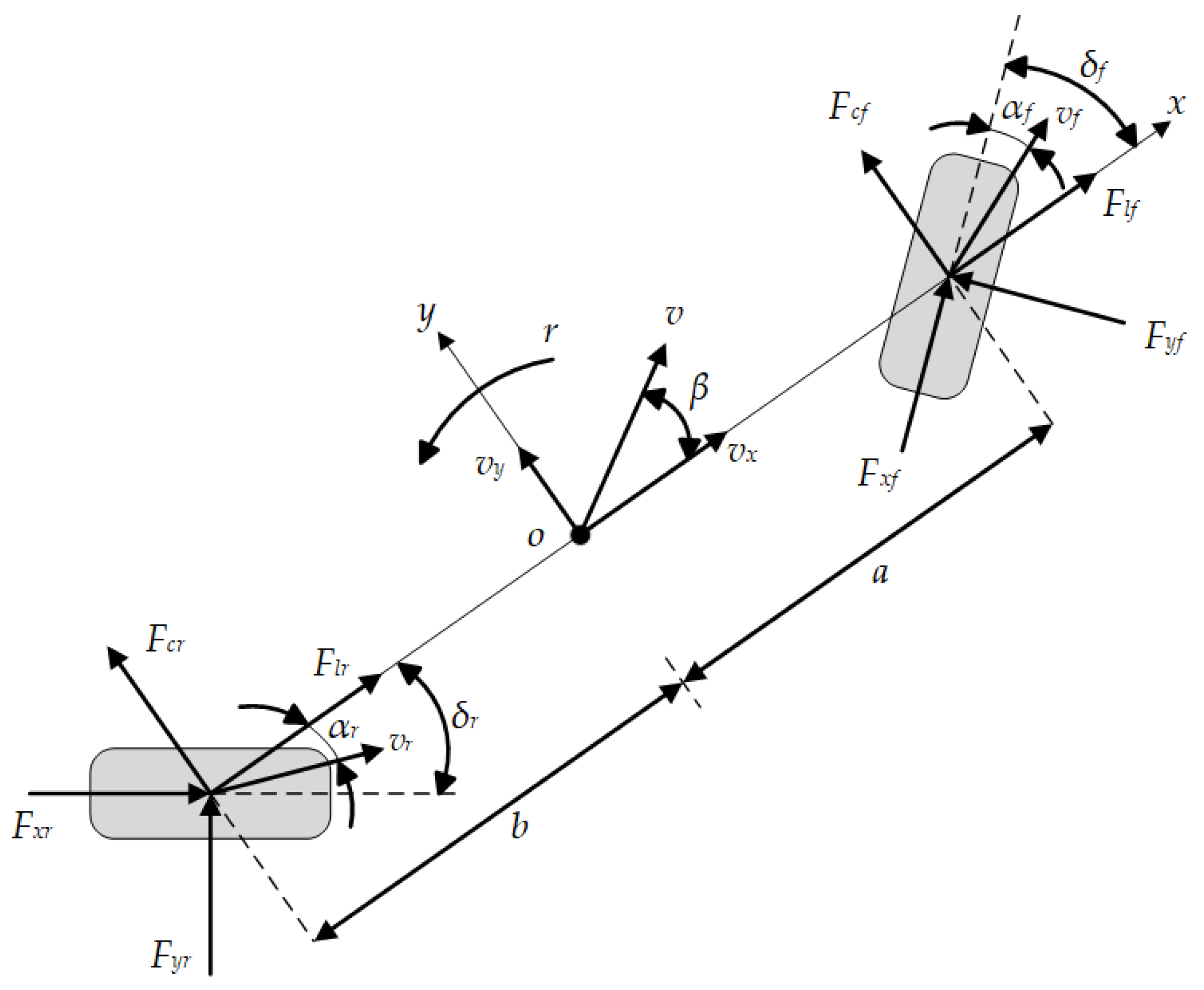

With the rapid advancement of intelligent vehicle technologies, modern chassis control systems are evolving toward integration, electrification, and intelligence. In recent years, integrated chassis control has emerged as a critical research focus in the dynamics of distributed drive electric vehicles (DDEVs) [

1,

2]. DDEVs, characterized by precise handling, short transmission chains, low energy losses, and compact structures, provide an optimal hardware platform for vehicle stability control via direct yaw moment control (DYC) [

3,

4,

5]. As a critical safety control method, four-wheel steering (4WS) technology actively intervenes in vehicle steering to approximate ideal response characteristics, thereby significantly enhancing handling stability [

6,

7]. Currently, numerous researchers are conducting extensive investigations into the integrated control of 4WS and distributed drive systems.

Zuo et al. [

8] proposed a hierarchical control strategy. The upper-layer controller employed sliding mode control to coordinate the rear-wheel steering angle and direct yaw moment, while the lower-layer controller optimized torque distribution based on the tire load rate to enhance vehicle stability. Chen et al. [

9] developed a hierarchical coordinated controller integrating active front steering (AFS) and DYC using extension coordination control theory, with wheel torque allocation optimized through quadratic programming. Zakaria et al. [

10] implemented fuzzy logic-based DYC for an eight-wheel independently driven vehicle. Jin et al. [

11] combined fuzzy control with a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) for 4WS implementation, activating additional yaw moment when exceeding predefined thresholds. While these approaches effectively improve vehicle stability, they generally neglect longitudinal dynamics analysis.

Lin et al. [

12] implemented independent control of longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motions using a backstepping sliding mode approach, significantly enhancing vehicle lateral stability. Ni et al. [

13] developed separate longitudinal and robust lateral controllers for autonomous racing vehicles, demonstrating the practical applicability of the algorithm. While these decentralized control architectures feature relatively simple algorithms and modest hardware requirements, they insufficiently address the inherent coupling between vehicle longitudinal and lateral dynamics.

This oversight presents two major challenges: First, both speed control and stability control in DDEVs are achieved through wheel torque regulation, creating strong subsystem coupling due to conflicting control objectives. Second, tire force variations during steering operations further intensify longitudinal–lateral coupling, significantly complicating precise vehicle dynamics control. Given the strongly coupled and nonlinear nature of vehicle dynamics systems, researchers have extensively investigated various decoupling methodologies.

Yu et al. [

14] developed a feedback–feedforward neural network decoupling strategy that achieved long-range decoupled tracking and improved tracking accuracy under emergency longitudinal-lateral coupled conditions. Zhang et al. [

15] implemented an extreme learning machine (ELM)-based neural network inverse dynamics system, successfully decoupling the longitudinal, lateral, yaw, and roll motions in chassis-integrated control. This algorithm demonstrated excellent path-tracking performance when applied to autonomous vehicles. Chang et al. [

16] introduced a novel CNN-LSTM inverse system design methodology that effectively decoupled lateral and yaw dynamics while enhancing both tracking capability and stability. Liang et al. [

17] employed neural networks to establish a pseudo-linear system and applied internal model control theory to coordinate longitudinal and lateral motion control, obtaining satisfactory control performance. Although these neural network-based inverse system approaches exhibit favorable decoupling performance and accuracy, their heavy dependence on extensive offline training data results in compromised real-time processing capability and limited emergency handling performance.

Differential geometry and differential flatness theory represent prevalent mathematical approaches for addressing nonlinear control problems, offering significant computational complexity reduction. Wang et al. [

18] successfully decoupled vehicle roll and planar dynamics using differential geometry methods, incorporating a load transfer ratio-based control trigger that effectively regulated roll angle and yaw rate independently. Wu et al. [

19] conducted comprehensive analysis of chassis system coupling relationships, establishing a pseudo-linear system through inverse system serialization to achieve decoupled control of lateral, yaw, and roll motions. However, these approaches uniformly neglected the influence of longitudinal motion on lateral dynamics. Wang et al. [

20] demonstrated the differential flatness property in three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) vehicle models and implemented a backstepping controller for longitudinal-lateral decoupled control. Nevertheless, the experimental validation omitted external disturbance testing, leaving the disturbance rejection capability of the system unverified. Gao et al. [

21] applied differential geometry theory to decouple longitudinal-lateral vehicle dynamics, developing a virtual control law with tire cornering stiffness estimation that enhanced intelligent vehicle path-tracking. However, this method exhibited insufficient precision in yaw rate control.

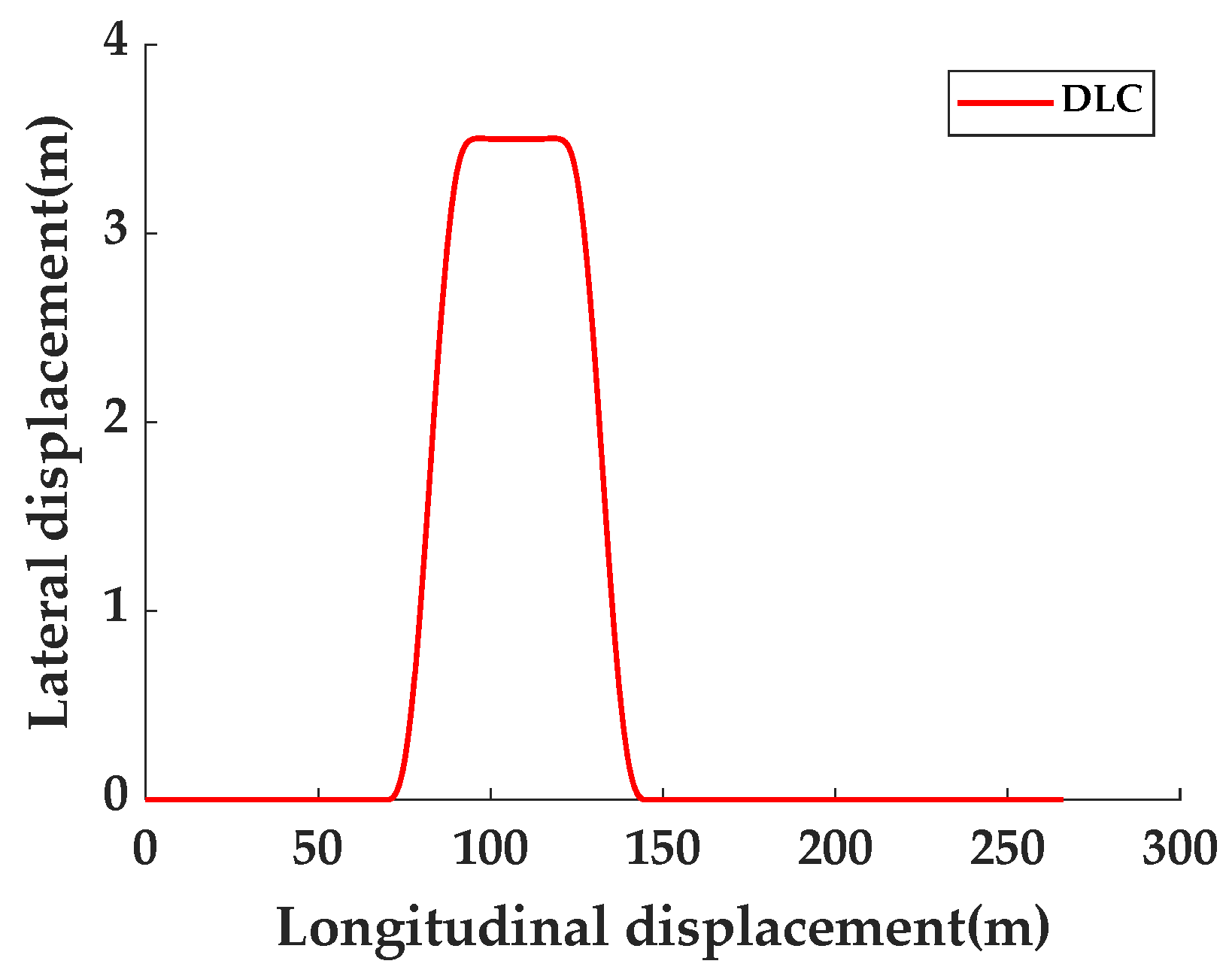

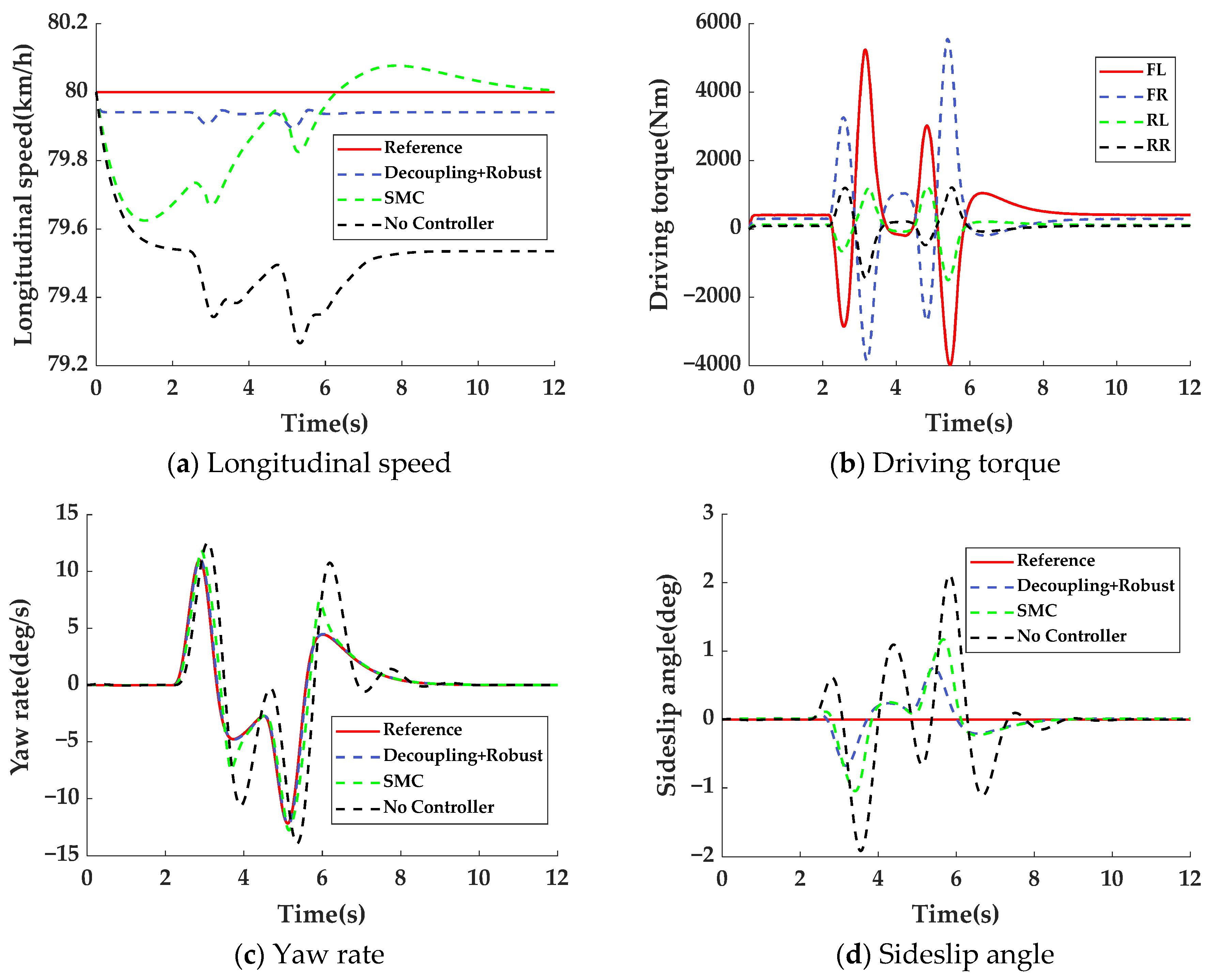

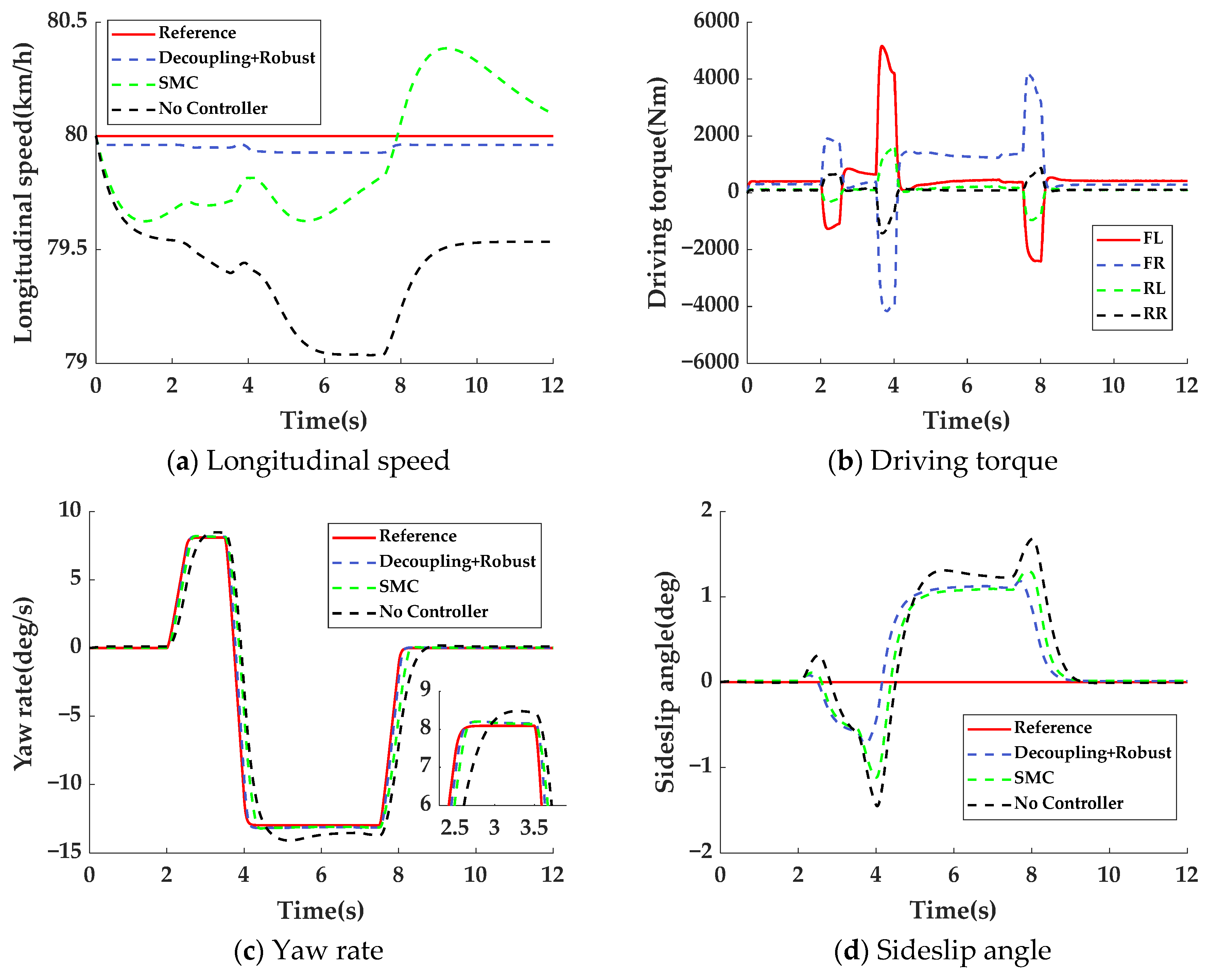

While the aforementioned studies have all employed differential geometric methods, they primarily focus on front-wheel-steering electric vehicles, rather than distributed drive electric vehicles capable of four-wheel steering. Based on this, this paper proposes a hierarchical controller that integrates differential geometric decoupling control with robust control. The controller decouples the three-input-three-output nonlinear vehicle system into three independent subsystems, enabling separate control of longitudinal, yaw, and lateral motions while enhancing disturbance rejection capabilities. Validation was conducted through TruckSim-MATLAB/Simulink co-simulation under various operating conditions. Compared to sliding mode control (SMC) and uncontrolled scenarios, the proposed method demonstrates superior performance, maintaining precise longitudinal velocity tracking while significantly improving yaw stability.

3. Control System Design

To achieve accurate tracking of reference values and improve crosswind disturbance rejection capability, a hierarchical controller combining a decoupling controller and robust controller was designed. The control system was implemented through co-simulation between TruckSim and MATLAB/Simulink, with the controller structure shown in

Figure 3.

The ideal reference model takes vehicle speed and front-wheel steering angle from the TruckSim driver model as inputs to calculate the desired yaw rate and center-of-mass sideslip angle. The upper-layer robust controller receives deviations between actual vehicle states (speed, sideslip angle, and yaw rate) and their reference values, then computes longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motion control laws through the controller. The middle layer performs differential geometry-based decoupling control, using the control laws from the robust controller as virtual inputs to resolve the 3-DOF nonlinear system into total driver demand torque, rear-wheel steering angle, and additional yaw moment. For torque distribution, the lower layer applies a constrained optimal allocation method to calculate wheel torques based on additional yaw moment and total demand torque. Finally, the rear-wheel steering angle and four-wheel torques are fed back to the TruckSim vehicle model, enabling the three state variables to track the reference model states and achieving stability control.

3.1. Differential Geometry Decoupling Controller Design

Rewrite Equation (6) into the structure of an affine nonlinear system and its specific form is as follows:

In the formula,

;

;

;

;

; and

.

Considering the dynamic characteristics of the disturbance terms, the disturbance terms are ignored during the decoupling process, which facilitates the selection of the subsequent state feedback control law.

Lemma 1 ([

23])

. For Equation (10), it has a relative degree at point , that is, the decoupling matrix is non-singular at point . Then the input-output decoupling problem of the system can be solved by static state feedback near point . The solution is the feedback defined by the following matrix:In the formula, is the new virtual control input. Assume that the controller is not enabled when the longitudinal velocity is zero, that is,

, and it can be used in the denominator for calculation. Differentiate the system outputs

,

, and

, respectively until the system input

is explicitly contained, and then stop differentiating. The first-order Lie derivative of

is as follows:

In the formula,

;

;

;

; and

.

At this time,

, that is, the first-order Lie derivative of

explicitly contains the system input

, so stop differentiating. The relative degree of the system

. The first-order Lie derivative of

is as follows:

In the formula,

;

;

;

; and

.

At this time,

, that is, the first-order Lie derivative of

explicitly contains the system input

, so stop differentiating. The relative degree of the system

. The first-order Lie derivative of

is as follows:

In the formula,

;

;

;

; and

.

At this time, , that is, the first-order Lie derivative of explicitly contains the system input , so stop differentiating. The relative degree of the system .

According to Lemma 1, when

, the relative degree of the system

exists, and the decoupling matrix

(Equation (19)) is non-singular. Therefore, the system can achieve full-state feedback linearization. Select the state variables as shown in Equation (20).

The decoupling control law of the system, Equation (21), is obtained.

Substituting Equations (19) and (21) into Equation (10), the decoupled linearized system can be obtained as follows:

Thus, the coupled nonlinear 3-DOF vehicle system has been decoupled into three independent linear subsystems. The three subsystems, respectively, use the new virtual inputs , , and of the system to independently control the system outputs of longitudinal velocity, yaw rate, and sideslip angle of the center of mass. Each output is not affected by other virtual inputs.

3.2. Robust Controller Design

In order to eliminate the influence of external interference in the modeling process, it is necessary to design an appropriate robust controller to enhance the anti-interference ability of the system. Define the system reference value

and the deviation

, then the system deviation state space can be described as:

In the formula,

;

; and

.

Definition 1 [

24]

. Suppose there is a transfer function that can be expressed as , then the following two conditions are equivalent:The system is asymptotically stable, and

There exists a positive definite symmetric matrix such that:

Lemma 2 ([

24])

. For system (23), there exists a state-feedback controller if and only if there exists a symmetric positive-definite matrix and a matrix such that the following Linear Matrix Inequality (LMI) (25) holds. Then the robust controller of the system can be expressed as .

Among them,

represents the supremum of the

norm of the closed-loop system. The smaller the supremum, the better the control effect of the designed robust controller. However, when the supremum is too small, it may lead to no solution for the controller [

25]. Therefore, when designing the robust controller, the following constraints are imposed on the supremum:

So far, for the decoupled linear system, a robust controller based on LMI has been designed. Its essence is to find the optimal solution of the LMI system. The mincx function in MATLAB can be used to solve Equations (25) and (26).

3.3. Torque Distribution Controller Design

Distributed drive vehicles control the power output of each tire by coordinating the torque among the wheels to ensure the stable driving of the vehicle. The controller uses an optimal distribution algorithm of quadratic programming. Under multiple introduced constraints, it gives full play to the role of each tire.

The distribution of the four-wheel torque first needs to meet the requirements of the additional yaw moment and the total demand torque. Therefore, minimizing the torque distribution error is set as the control objective, and the corresponding objective function expression is obtained as follows:

In the formula,

is the control demand weight matrix;

is the demand matrix;

is the control efficiency matrix; and

is the control input matrix.

- 2.

Objective function based on tire load rate

The ratio of the tire force to the maximum adhesion force that the road surface can provide is called the tire load rate. The greater the tire load rate, the more road adhesion force is consumed by the tire force, resulting in less remaining available adhesion force, making the tire closer to the saturation state and thus reducing the stability margin of the vehicle. Based on this, in this paper, the minimum sum of the squares of the four-wheel tire load rates is taken as the objective of torque optimization distribution. The expression of the objective function is:

It is relatively difficult to directly control the lateral tire force, and the longitudinal tire force can be directly adjusted by controlling the motor. Therefore, considering the actual working conditions and calculation efficiency comprehensively, the objective function can be simplified as:

In the formula,

represents the Hessian matrix.

Thus, for the purpose of achieving optimal torque distribution, the following objective function is formulated:

In torque distribution, in addition to the optimization objective, two constraint conditions need to be set: the tire adhesion limit and the torque limit of the in-wheel motor, to meet the safety requirements of tire adhesion and the driving and braking capabilities of the in-wheel motor, respectively.

The longitudinal and lateral forces of each tire satisfy the constraints of the adhesion ellipse. The constraint conditions are:

Equivalent to it is the torque expression:

Let the peak torque of the motor be

, then the torque of each wheel needs to satisfy:

5. Conclusions

This study presents a control strategy combining differential geometry decoupling with robust control to solve the coupling issues between steering and drive systems in four-wheel steering distributed drive electric vehicles. The proposed method decouples the three-input-three-output integrated chassis system into three independent subsystems, achieving precise control of longitudinal velocity, yaw rate, and sideslip angle. Taking into account crosswind disturbances during actual driving conditions, robust controllers are designed for the decoupled subsystems to form a hierarchical control architecture.

Co-simulation results using TruckSim and MATLAB/Simulink show that compared to SMC and No Controller cases, the proposed decoupling robust control strategy demonstrates superior performance. In standard DLC and fishhook maneuvers, it maintains a longitudinal speed tracking error within 0.14% while improving the yaw rate by at least 39% and reducing the sideslip angle by 9%. When subjected to crosswind conditions, this method reduces lateral displacement by 42.21% compared to SMC while keeping longitudinal speed deviation at 0.15%, decreasing the yaw rate by 67.82% and lowering the sideslip angle by 2.88%. The strategy effectively enhances vehicle driving stability and safety.

Although the control strategy proposed in this study has been initially verified in offline simulations, future work will focus on real-vehicle testing to obtain more valuable real-world data, thereby making the research more closely aligned with engineering practice.