Abstract

Current and potential electric vehicle (EV) owners express concerns about the charging infrastructure, mentioning non-functional chargers, prolonged charging times, inconvenient charger locations, long wait times, and high costs as major barriers. Addressing these issues often requires analyzing actual vehicle charging data, which is typically proprietary and inconsistent due to diverse standards and protocols. To understand and improve the EV charging experience, customer reviews are typically used to identify common customer pain points (CPPs). However, there is not a comprehensive method to map customer reviews to a standardized set of CPPs. In collaboration with the National Charging Experience (ChargeX) Consortium, this study bridges these gaps by proposing a Systematic Categorization and Analysis of Large-scale EV-charging Reviews (SCALER) framework. SCALER is an integrated, deep learning framework that segments, actively labels, analyzes, and classifies EV charging customer reviews into six CPP categories. To test its effectiveness, we used SCALER to analyze over 72,000 reviews from customers charging various EV models on different networks across the United States. SCALER achieves a classification accuracy of 92.5%, with an F1 score exceeding 85.7%. By demonstrating real-world applications of SCALER, we enhance the industry’s ability to understand and address CPPs to improve the EV charging experience.

1. Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a pivotal element in the global shift to decarbonize transportation in recent years. Their rise in popularity can be attributed to their numerous advantages over fossil-fueled cars, such as lower operating costs and the potential for at-home refueling [1,2]. A surge in demand has propelled the growth of the EV market, driven by advancements in technology, growing acceptance among consumers, and lower costs of popular EV models [3]. Notably, the declining cost of lithium-ion battery packs has contributed to the improved affordability of EVs [4,5]. Owing to some of these advancements, analysts anticipate that EV prices will achieve parity with traditional gasoline cars in the near future [6] and parity, considering the total cost of ownership has already been seen in the market today [7]. In terms of market share, EVs accounted for 18% of all cars sold globally in 2023, up from 14% in 2022 [8]. The momentum towards electric mobility is further bolstered by state legislative efforts. As many as 15 U.S. states, led by California, aim to reach 67% EV sales by 2030 [9].

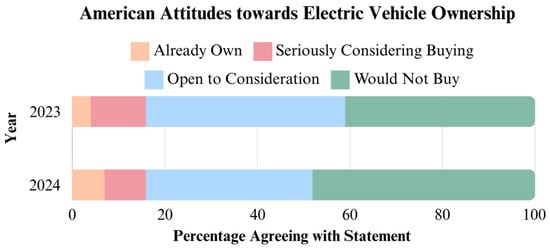

However, notwithstanding the generally favorable perception of EVs among a considerable segment of consumers [10], EV ownership in the United States is growing only modestly. Many prospective buyers, often categorized as “EV curious consumers,” exhibit reluctance to transition to EV ownership [11,12]. Multiple factors contribute to these hesitations, such as limitations in battery range, financial considerations, doubts regarding convenience and performance, and a general lack of confidence in the availability and reliability of EV charging infrastructure [13,14]. Concerningly, Figure 1 suggests that these challenges are causing a growing number of Americans to shy away from considering EV adoption.

Figure 1.

American attitudes towards EV ownership—a summarized breakdown of customers who own, would like to own, and who would not like to own an EV based on available literature [10]. The figure illustrates an increase in the percentage of Americans who would not consider purchasing an electric vehicle between 2023 and 2024.

One source of these customer concerns is the reliability of the public EV charging network. It is widely recognized that issues with public fast charging networks are prevalent, prompting extensive research efforts from academia, national labs, and industry stakeholders [15,16,17,18]. A significant breakthrough in this domain has been the development and widespread adoption of the North American Charging Standard (NACS) connector [19]. Recently, the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) formalized the Tesla-developed NACS connector design into the SAE J3400 standard [20], marking a significant milestone for enhancing the public fast charging experience. Concurrently, this momentum has been mirrored by the federal government’s commitment, demonstrated through the establishment of the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (Joint Office) and the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) standards and requirements, applicable to federally funded charging infrastructure, as codified in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. As part of its work, the Joint Office also sponsored the creation of the National Charging Experience Consortium (ChargeX Consortium) to improve charging reliability by collaborating with over 85 stakeholders in the EV charging ecosystem, guided by the motto of “any driver, any EV, any charger, the first time, every time.”

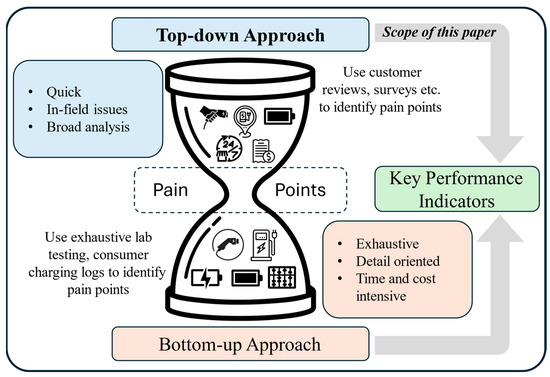

The perception of unreliable public chargers has garnered significant attention in both automotive circles and mainstream media outlets [20]. Consequently, as shown in Figure 2, EV charging stakeholders have adopted a two-pronged approach to address this problem. Method 1 involves a bottom-up approach, where extensive lab testing is undertaken and actual EV charging logs are analyzed to identify the root causes of problems [21,22]. While this method is systematic and approach-driven, it is often time-consuming due to the sheer volume of logs and various challenges, such as data privacy issues, amongst other interoperability concerns. On the other hand, Method 2 employs a data-driven top-down approach, leveraging customer reviews to obtain quick, first-hand information about in-field problems [23,24,25,26]. While this approach may oversimplify the issues at hand, it facilitates a rapid assessment of the current issues and the overall state of the EV customer experience. Such customer reviews have been extensively cited in media articles, exemplified by accounts like those described by Malarkey et al. [16]. Reports from reputable sources like Motor Trend further illuminate staff members’ experiences with EV charging during winter road trips, exposing frustrations with inadequate and unreliable charging infrastructure [27,28]. Additionally, recent efforts by well-established entities, such as JD Power, focus on assessing the general EV customer experience, finding that these frustrations are common across the EV landscape [29].

Figure 2.

The two-pronged approach, which is followed by EV charging stakeholders to improve the EV charging infrastructure. Our paper follows the top-down approach, utilizing customer-focused data to deliver rapid insights into the state of the EV charging experience.

A wealth of EV charging customer reviews and comments are readily available on various public online platforms (e.g., Google, Reddit, X, PlugShare, ChargeHub). These customer testimonials serve as invaluable resources, offering deep insights into the operational challenges of EV charging infrastructure, especially those issues that are difficult to observe through operational data alone. This approach has gained significant traction among industry and researchers, leading to numerous studies aimed at understanding and improving the EV charging experience. Liu et al. [23] employed Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to analyze reviews from EV drivers, evaluating the reliability of charging infrastructure across various languages. Gong et al. [24] conducted sentiment analysis on EV online reviews using the SMAA-2 method and interval type-2 fuzzy sets, providing valuable insights into consumer perceptions and satisfaction levels regarding charging infrastructure. More recently, Ha et al. [25] used a transformer-based deep learning model to analyze comments on EV charging infrastructure, providing a detailed understanding of topical distribution in customer feedback. Additionally, Marchetto et al. [26] introduced a deep learning approach to extract data on customer behavior at charging stations, providing insights for infrastructure planning and management.

However, these studies lack a scalable, standardized framework for categorizing reviews into actionable customer pain points, leaving a pressing research challenge. Our work aims to fill gaps in current research in identifying customer-facing EV charging challenges through three key objectives. First, we standardize customer pain points (CPPs) into distinct categories that define the charging experience, drawing on the expertise of over 85 stakeholders within the North American EV community. This collaborative effort serves as a foundation for establishing common benchmarks across the entire North American EV charging ecosystem. Second, we apply an active-learning framework to label customer reviews, enabling a scalable data-driven approach by reducing the training burdens required by modern deep learning methods. Although we build upon existing methods for sentiment analysis, our focus remains on adapting existing large language models (LLMs) to the unique context of EV charging infrastructure. Third, we harness LLMs to extract and categorize CPPs from customer reviews. As shown in Figure 2, the ChargeX Consortium’s ultimate goal is to create key performance indicators (KPIs) that quantitatively assess the EV charging experience. This work leverages the top-down approach to build a standardized framework for analyzing CPPs, forming the basis for future KPI development

2. Materials and Methods

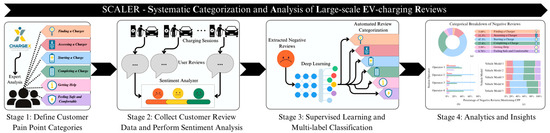

In this work, we propose a comprehensive four-stage process to tackle the aforementioned challenges, titled SCALER (Systematic Categorization and Analysis of Large-scale EV-charging Reviews). SCALER is illustrated in Figure 3. The first stage of SCALER focuses on defining the charging experience and categorizing common issues into distinct CPP categories, leveraging insights from over 85 stakeholders in the ChargeX Consortium. This establishes a foundational framework for categorizing the diverse issues customers face during EV charging. The second stage involves the systematic collection and filtering of customer reviews from various public platforms. During this stage, we employ sentiment analysis to filter out reviews, focusing particularly on those that are negative, which are more likely to contain valuable information about problems with the EV charging infrastructure. In the third stage, the filtered reviews are then classified into the predefined CPP categories using a supervised learning algorithm. This ensures that each review is accurately categorized, allowing for a structured analysis of the issues identified by EV customers. The final stage involves an in-depth analysis of the categorized review data. By examining the binned data, we can extract valuable insights into the state of EV charging infrastructure and highlight the most pressing pain points and areas needing improvement. More details on each stage of SCALER are provided in the following sections.

Figure 3.

The proposed SCALER approach showing the four stages of the framework. We begin by defining CPP categories, then collect raw, publicly available customer review data from online sources. These reviews are classified as positive, neutral, or negative using sentiment analysis, and a supervised learning framework is utilized to classify the CPPs present in the negative reviews. With these findings, we can derive insights into the state of the charging experience by correlating CPPs with review metadata. The findings previewed in Stage 4 are discussed in detail in Figure 6.

2.1. Defining Customer Pain Point Categories

As mentioned in the previous section, existing literature and research on EV charging infrastructure fell short of providing industry-agreed-upon, precise definitions for commonly encountered CPPs. This gap primarily arose from the lack of consensus among EV charging stakeholders, which included manufacturers, policymakers, and customers. This was further complicated by niche jargon and the lack of structured data in customer reviews. These challenges make it a daunting task to manually categorize and understand the underlying problems that EV charging customers are describing. In their work, Ha et al. attempted to address this issue by defining eight main topics and 32 subtopics. However, these topics did not provide an organized method to assess the charging experience that can easily be tied to quantitative KPIs, which would provide charging station operators (CSOs) with actionable insights and ideally prioritize problems to best improve the customer charging experience. For example, their topic of functionality broadly covered aspects such as chargers, screens, card readers, error messages, power levels, and customer service. Consequently, the categories and models proposed by Ha et al. [25] required large expert-annotated datasets. This could be avoided with more specific CPP categories. Moreover, we foresaw that the topics proposed by Ha et al. [25] were not suitable to build KPIs that sufficiently assess station performance when paired with the work by Quinn et al. [14] and the ChargeX Consortium.

To overcome these challenges, our work began by defining the ideal EV charging customer experience as “achieving session success every time EV drivers plug in.” Guided by this principle, we identified individual CPPs by reviewing thousands of user-generated, publicly available customer reviews, which contain rich information about customers’ experiences and challenges with EV infrastructure. After lengthy discussions, the experts in the ChargeX Consortium organized these CPPs into six individual categories that are broad, yet distinct enough to accommodate all CPPs and capture the major elements of the charging experience. These six CPP categories are presented in Table 1, along with their definitions and examples of individual CPPs experienced within each category. More details on the binning methodology used, the motivation, common issues identified, and their prioritization are provided in Quinn et al. [14] and Malarkey et al. [16]. In summary, a systematic approach under SCALER ensured a structured and comprehensive understanding of the most critical pain points and helped set the stage for targeted interventions and improvements in the EV charging experience. It is worth noting that the broad yet standardized definitions of the six CPP categories under SCALER allow for new CPPs that are either not listed in Table 1 or that may emerge in the future to be effectively linked back and binned under one of these six categories.

Table 1.

Customer pain point categories, definitions, and examples.

In the following section, we provide details on sentiment analysis, which is the next stage within SCALER.

2.2. Sentiment Analysis

To analyze CPPs, data relating to negative experiences can be extracted from customer reviews. However, in practice, EV charging customer reviews often contain a mixture of comments that may have a positive, neutral, or negative sentiment. To effectively extract data about CPPs from these reviews, it is essential to isolate reviews with negative sentiment for further analysis. This process is complicated by the fact that reviews frequently exhibit mixed sentiments, wherein customers might criticize one aspect of the charging experience while praising another or report a negative charging experience but a positive interaction with a nearby establishment. To overcome this, we incorporated advanced filtering mechanisms within SCALER that help us pinpoint negative customer experiences and therefore the negative charging experiences within each customer review. This approach represents a significant extension of EV charging review analytics beyond the state of the art described in existing literature. While sentiment analysis is used as a preprocessing step for SCALER, it does more than just isolate reviews with negative sentiments; it also provides a comprehensive snapshot of overall customer satisfaction. This, on its own, provides useful insights into the EV charging industry.

Performing sentiment analysis for EV charging customer reviews involved other challenges. First, classifying neutral sentiment proved difficult, as echoed by other studies, due to its often-ambiguous nature. Second, customer reviews often included emojis to express sentiments. To capture these complex expressions accurately, we replaced emojis with verbal sentiments that closely matched their meanings. For example, an enraged face emoji was replaced with the phrase, “I am enraged.” Emojis that could not be clearly identified with a specific sentiment were removed from the reviews. This approach enhanced the clarity of sentiment-unambiguous emojis while mitigating the unintended effects of sentiment-ambiguous ones, such as a crying emoji. Note that we did not consider reviews with fewer than two words, due to a lack of context, even if they had more emojis. Additionally, we did not remove stop words (e.g., if, but, he/she/they) as they may provide context necessary for identifying and classifying negative reviews.

In the following section, we used the definitions for the six CPP categories in Table 1 and the processed negative comments identified through the sentiment analysis detailed above to actively label, train, and test classification models within SCALER. Additional examples of the sentiment classification of reviews can be found in Table A2 within Appendix C.

2.3. Supervised Learning and Multi-Label Classification

Following the sentiment analysis stage, we extracted and processed the negatively labeled comments and classified them according to the six CPP categories given in Table 1. Unlike traditional, single-label classification approaches, we utilized a multi-label classification system, as proposed by Ha et al. [25]. The multi-label approach is required because customer reviews frequently address multiple CPP categories within a single comment. Therefore, enforcing the model to assign a single category to a complex multi-category review would limit its predictive capabilities. Table 2 provides a few examples illustrating this complexity, and additional examples can be found in Table A3 in Appendix C.

Table 2.

Example customer reviews and their CPP categories.

Next, recognizing the complexity and time-consuming nature of manual labeling, we used a multi-label, active-learning approach in SCALER. To this end, we employ an extended version of the Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement (BALD) algorithm [30] for the multi-label classification problem. In our multi-label classification setting, is a binary vector, where each entry corresponds to the presence or absence of a particular label. For each label , the entropy is then calculated using the predicted probability using the sigmoid function. Given model parameters, , the BALD score for each instance is the sum of the individual entropies across all labels. Thus, the modified BALD acquisition function is given according to Equation (1):

where is the labeled training set used to train a model. Such a modification allows us to extend the BALD algorithm to handle multiple labels by employing a sigmoid function for each label , where is used to denote each sample from the approximate posterior distribution during the Monte Carlo sampling process. This allows the algorithm to estimate uncertainty independently for each potential label, effectively identifying the most informative customer reviews for labeling across multiple categories. More details about the modified BALD algorithm are given in Appendix A.

By extending BALD to a multi-label classification problem, we strategically selected reviews that maximize the information gain for each CPP category, thus improving the efficiency and accuracy of our labeling process. This adaptation ensures that our models learn from the most valuable data points, reducing the overall workload and enhancing the capability to capture the nuanced and multifaceted nature of customer feedback in the EV charging domain.

2.4. Analytics and Insights

With CPPs extracted from customer reviews and then classified, the SCALER framework can then be used for multifaceted analysis. First, the frequency of CPP occurrence within and across each category can be analyzed to discern the most pressing problems and to identify areas that require immediate action, effectively prioritizing the response to customer-reported issues. Second, SCALER can support detailed analysis and benchmarking across different EV charging stakeholders. By comparing performance across different CSOs and monitoring CPPs, customer satisfaction can be tracked, thereby creating a competitive environment. Third, with some metadata, SCALER can be leveraged to identify problematic interactions between EVs and chargers, referred to as interoperability issues. By analyzing customer feedback related to interoperability, SCALER sheds light on high-level hardware or software incompatibilities that may hinder the charging process. Addressing these interoperability challenges is crucial for ensuring a seamless and user-friendly charging experience, thereby supporting broader EV adoption. Finally, SCALER can also be used to provide insights into customer mentality by analyzing how customers express problems and describe the charging experience (often in very different terms than those used by industry practitioners). These insights are valuable for understanding the accessibility of EV technology to the average customer, guiding the development of more intuitive user interfaces, and creating clearer instructional content. By understanding how customers articulate their experiences and frustrations, stakeholders can tailor communications and support services to be more effective and customer-friendly. Together, these capabilities provide EV charging stakeholders with powerful insights for improving the EV charging customer experience. The following section demonstrates the use of SCALER for the abovementioned purpose of using actual customer reviews.

3. Results

3.1. Data

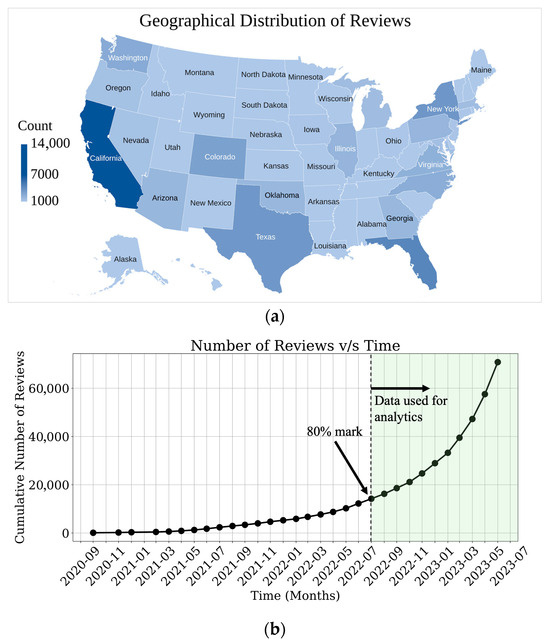

To demonstrate the capabilities of SCALER, we conducted a case study using a dataset of 72,314 customer reviews obtained from online platforms, representing 3161 public charging stations rated above 70 kW across the United States. All data was collected from publicly available online sources and required no institutional board approval. The distribution of customer reviews by the state in which they originated is shown in Figure 4a. Each review in the dataset was accompanied by some generic metadata, including (i) station ID (ii) station location, (iii) the vehicle details of the customer who left the review, (iv) station operator, and (v) the date it was posted. This metadata allowed for a detailed analysis and contextual understanding of the feedback. Although the reviews we used were collected between 2013 and 2023, more than 80% of these reviews were concentrated in the two years prior to our study (i.e., July 2022 to May 2023). Figure 4b shows the distribution of the collected customer reviews in our dataset across time. Therefore, although we used the entire dataset to train and test our model, we only used the latest 80% of the data, collected from July 2022 to May 2023, for analytics to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach. Due to the rapid pace of improvements being made, any data before this cutoff date was deemed too old to draw insights about the current state of the EV charging experience in the United States.

Figure 4.

Distribution of customer reviews by (a) U.S. state and (b) date it was recorded. Plot (a) demonstrates the comprehensive nature of our dataset, containing reviews from nearly all high-voltage charging stations in the U.S. at the time of collection. Significant portions of our reviews are concentrated in certain areas where EVs are especially prevalent, namely California, which is reflective of the current landscape of EV ownership. Plot (b) shows how 80% of our collected reviews were written after July 2022, a metric that is used to justify our analytical data cutoff.

Our temporal segmentation strategy requires explicit justification, given the dataset’s decade-long span. The July 2022 cutoff for analytics coincides with transformative infrastructure developments: the Federal Highway Administration’s NEVI standards implementation and the formalization of NACS as SAE J3400 [19]. These regulatory and technical standardization efforts fundamentally altered the charging landscape. Analysis of our dataset confirms this shift, with negative review rates declining from 31 percent in 2020–2021 to 24 percent in 2022–2023, and the nature of complaints evolving from infrastructure availability concerns to operational reliability issues. Training our classification models on the complete historical dataset (2013–2023) ensures exposure to diverse linguistic patterns and edge cases accumulated across the full EV adoption curve. However, limiting our analytical insights and recommendations to post-July 2022 data ensures relevance to current infrastructure conditions rather than obsolete early-adoption challenges. This mirrors established practice in technology domains where historical data breadth supports model robustness while recent data ensures actionable insights [23,25].

3.2. Experiments with Sentiment Analysis

In our work, to evaluate the effectiveness of sentiment analysis using SCALER, we randomly sampled 4000 reviews from our dataset and manually labeled them as negative, neutral, or positive. Two independent, expert annotators performed this labeling process, which resulted in a Fleiss kappa of 0.718. The proportion of negative, neutral, and positive reviews in this dataset is shown in Table 3. These were then used to finetune two different LLMs: the Robustly Optimized Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) Approach (RoBERTa) [31] and eXtreme Language understanding NETwork (XLNet) [32]. These models were specifically chosen for their ease of use in future benchmarks using the HuggingFace “https://huggingface.co/ (accessed on 1 October 2023)” library and their widespread use in text classifications [33,34,35] and EV charging reviews [25,26]. For RoBERTa and XLNet, we use the tokenizers corresponding to each model, which split text into sub-word tokens and map them to vocabulary indices. These token sequences are then processed through the models’ embedding layers to produce the numerical representations used for classification. Detailed justification regarding hyperparameters and their choices is given in Appendix B.3.

Table 3.

Sentiment Analysis Dataset.

To adapt the LLMs for identifying domain-relevant sentiments we finetuned both models using the train–test split (80–20%) described in Table 3. While the RoBERTa model was finetuned with a learning rate of and L2 regularization, with a weight decay parameter of 0.01, the final layer of XLNet was modified and then finetuned with a learning rate of and L2 regularization, with a weight decay parameter of 0.1. Model performance is summarized in Table 4. Note that the original XLNet model could only identify positive and negative sentiment. Therefore, for a fair comparison, while we report results for untrained RoBERTa, we do not report results for untrained XLNet in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Sentiment Analysis Model Performance.

By finetuning RoBERTa, as shown in Table 4, the model was able to adapt and learn domain-specific sentiment and performance by about 5% on the F1 score and about 7% on accuracy. A review of the incorrectly classified reviews from the untrained model indicated that “ICEing,” or the blocking of chargers by internal combustion engine vehicles, was often misclassified as neutral sentiment. This was improved upon in the finetuned model. In summary, considering the results, we conclude that while finetuning improves performance, even an off-the-shelf LLM, such as RoBERTa, performs relatively well. Nevertheless, we recommend that some level of finetuning be performed to adapt these models to the task.

3.3. Comparison of Sampling Strategies

In our study, we implemented and assessed two Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed active-learning strategy using the modified BALD algorithm. We specifically chose an LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) network and a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) because of their successes in the work by Hal et al. [25]. Although several architectures were tried, we only provide details for the best-performing architectures. The first model is a Deep Neural Network (DNN) with three fully connected layers, each consisting of 64, 32, and 16 neurons using the hyperbolic tangent activation function at every layer and a dropout rate of 20%. The second model is a 1D-CNN, which includes a 1D convolutional layer with 64 filters, a subsequent max pooling layer, followed by a fully connected layer with 16 neurons and a dropout rate of 20%. Both neural networks use the same output layer with six neurons using a sigmoid activation function, appropriate for our multi-label classification problem. We trained both models using binary cross-entropy as our loss function and used an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of and a batch size of 32 to facilitate the training process for 100 epochs. Both models use the same embedding layer with 64 outputs. Note that we followed a similar training strategy to what was suggested by Gal et al. [30] and reset the network’s weights after every iteration to the same initial weights to avoid confusing improvements using additional samples and training for additional epochs. In our work, we sample times from the approximate posterior distribution to calculate the BALD score by setting in Equation (1).

We used a finetuned version of RoBERTa for sentiment analysis on a dataset comprising 72,314 reviews to train classification models effectively. This initial analysis identified 17,125 reviews as having negative sentiments, highlighting significant customer dissatisfaction. From this subset, we manually labeled 4665 reviews across the six CPP categories, with each review often tagged with multiple CPP labels. This meticulous labeling was conducted by two independent, expert reviewers, who achieved a Fleiss kappa of 0.623, which indicates a substantial agreement among the reviewers regarding the categorization of content.

To structure our machine learning training and testing, we randomly sampled these reviews to create a balanced dataset, resulting in a test set comprising 393 reviews and a training set with 407 reviews. Note that we use the same tokenizer as for RoBERTa unless specified otherwise in this section. Care was taken to ensure each CPP category was equally represented in these sets, with around 100 labels each in and . (The numbers do not total 600 due to the overlap of CPP labels in some reviews.) The remaining 3865 reviews constituted our pool set . allowed us to continually augment our training set by adding the most informative reviews identified by the model in each iteration of the learning process, following the methodology outlined by Gal et al. [30]. This strategic approach to sampling and iterative enhancement significantly enriched the learning models’ exposure to diverse customer feedback, enhancing the robustness and accuracy of our classification system. Table 5 provides a detailed breakdown of the distribution of reviews in our train, test, and pool sets, illustrating the comprehensive framework we adopted for this analysis.

Table 5.

Processed Classification Dataset.

In our experiments, we initially trained both models—the DNN and the 1D-CNN—using with 407 reviews for 100 epochs and then iteratively sampled 200 reviews from using either the modified BALD acquisition function or random sampling during each iteration. The sampled reviews were then added to , and the models were retrained for 100 more epochs using the augmented trainset. This procedure was followed until no reviews were left in Figure 5 presents the training progression and comparison of the two models under different sampling strategies within the active-learning scheme in SCALER. All reported model performance metrics throughout this paper represent averages across three independent training runs with different random seeds to ensure robustness to initialization unless specified otherwise.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the two BNNs over the test set when trained with and without the modified BALD active learning function, averaged across three runs. BALD initially provides significant gains in F1 score over random sampling, though these advantages diminish after roughly 2200 reviews are used for training.

Note that the F1 score was calculated using after every iteration, sufficient care was taken so that the model was never exposed to it during training. From the onset of initial training, both models exhibited a rapid improvement in F1 score as the number of training reviews increased, with significant gains visible up to approximately 1800 reviews. This phase highlights the models’ ability to quickly learn from highly informative reviews extracted through the active-learning process. Interestingly, the DNN consistently outperformed the 1D-CNN by reaching a max F1 score of 0.788, underscoring the DNN’s ability to more effectively capture and utilize local feature dependencies in textual data. This is crucial in understanding nuanced customer feedback in EV charging scenarios. However, it is worthwhile to note that both models plateaued beyond about 1807 reviews, suggesting diminishing returns from additional training data under the strategies employed. Interestingly, the performance of both models under the proposed active-learning strategy closely aligned with their performance under random sampling by about 2207 reviews, indicating that the initial advantage of strategic sampling diminished as the models became sufficiently trained.

These results, which align with the findings provided by Kirsch et al. [36], highlight that while active learning significantly boosts model training initially, the choice of strategy becomes less critical as the model’s exposure to diverse data increases. Despite this, based on the systematic framework of SCALER, we recommend continuing with an active-learning strategy to minimize the overhead of labeling excessive samples without iterative feedback from the model.

In the following section, we evaluate five different models, including state-of-the-art LLMs using the data that is actively sampled by our best-performing model (the DNN) under the proposed active-learning strategy, shown in Figure 5.

3.4. Comparison of Models

With the advent of LLMs, the landscape of text classification has witnessed transformative advancements [23]. To harness these innovations that are evident in our sentiment analysis, we extended our experimentation to include not only traditional models like the DNN and the 1D-CNN but also advanced LLMs specifically finetuned for our application. However, we did not use an active-learning strategy to train the LLMs in this section due to the overwhelming computational burdens and per-token cost. Instead, we trained the state-of-the-art LLMs, the DNN and the 1D-CNN, using the same training set that was sampled by the DNN after the first seven iterations of the active-learning strategy we proposed in the previous section. This is highlighted in Figure 5. At this point, now had 1807 reviews (initial 407 and an additional 1400 sampled by the DNN), and the test set remained unchanged, as specified in Table 5. This approach allowed us to use the DNN as a surrogate model, thereby avoiding the excessive per-token costs incurred during the training of these LLMs. In our evaluations, we finetuned some of OpenAI’s models using our dataset. Note that these models have their own tokenizers. As is expected, the oldest model, babbage-002, performed slightly worse than davinci-002. The performance disparity between the finetuned babbage-002 and davinci-002 models was primarily attributed to differences in their architectures and capabilities. The davinci-002 is part of OpenAI’s more advanced and larger GPT-3 series, typically characterized by a substantially higher number of parameters. This extensive capacity enabled davinci-002 to better generalize from training data, allowing it to capture more complex patterns and subtleties within the text. In contrast, babbage-002, though still effective, had fewer parameters, which might limit its ability to learn from diverse or nuanced data similarly. Interestingly, the performance of these models was similar to that shown by the simpler models, such as the DNN and the 1D-CNN. This similarity suggested that while the advanced capabilities of LLMs offer distinct advantages, the fundamental ability to process and analyze text data effectively may still be achieved with less complex models due to the specific requirements and constraints of the task at hand. This observation highlights the importance of carefully considering model selection based on the specific characteristics of the dataset and the computational resources available.

As shown in Table 6, apart from GPT-3.5-turbo-0125, all models failed to efficiently learn and interpret the context that may help with text classification and never exceeded an F1 score of 0.8. This may be due to the fact that EV charging reviews were often extremely complex and full of niche jargon. Further, reviews often imply the problem at hand rather than state it explicitly, requiring the reader to infer details about what occurred. In our opinion, this is the same reason that expert-annotated datasets achieved high accuracies in the work by Hal et al. [25] in comparison to crowd-annotated datasets. Such complexities require a model that can grasp the nuanced interplay of factors that describe issues within EV charging. The finetuned GPT-3.5-turbo-0125, with its advanced architecture and extensive training on a diverse corpus, was better equipped to handle such complexities, parsing through layers of context and extracting meaningful patterns crucial for accurate classification with an F1 score of 0.857. In contrast, other models, despite being effective to a certain extent, often overfit and struggled to fully capture and interpret the intricate expressions and technical specifics presented in customer reviews of EV charging, leading to less precise or less contextually aware outcomes. This complexity highlighted the significance of choosing a model that aligns well with the specific linguistic and contextual challenges posed by the domain-specific text, ensuring that the nuances of user-generated content are accurately understood and used. In summary, we demonstrated through this study the effectiveness of employing advanced LLMs for the analysis of complex, domain-specific text, such as EV charging reviews. We discuss the practical deployment aspects of the SCALER framework in Appendix B.

Table 6.

Summary of Results for Trained Classification Models.

In the following section, we demonstrate the usefulness of SCALER for any associated EV charging stakeholder.

3.5. Use Cases and Observations

To demonstrate the effectiveness and value of SCALER, we employed the finetuned GPT-3.5-turbo-0125 model to categorize all remaining unlabeled reviews in our dataset after July 2022. We grouped results by CSO and EV make/model to demonstrate how SCALER could be used by EV charging stakeholders to assess the EV charging customer experience for different products and services and identify specific areas of needed improvement. However, we anonymized names and reported only the top four CSOs and the top five EV models represented in our dataset, replacing them with generic labels to prevent any potential bias or discrimination. This methodology not only highlights SCALER’s utility in parsing and understanding complex datasets but also maintains the integrity and neutrality essential for such analyses.

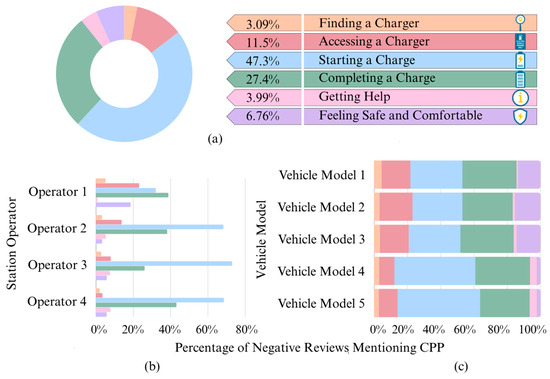

As shown in Figure 6a, the prevalence of CPPs by category among negative reviews varied significantly. Most issues were reported in the Starting a Charge category, meaning that customers most commonly encountered and reported problems initiating their charging sessions. The next most common CPP category was Completing a Charge, with Accessing a station to attempt a charge coming in third. Fewer customers reported problems with finding charging stations, feeling safe and comfortable, and contacting support staff for help, although this could be influenced by customers prioritizing reporting issues related to starting, finding, or accessing a charger. Notably, nearly half of all negative reviews came from customers who either had difficulty initiating a charge or were unable to charge their EV altogether.

Figure 6.

Insights into the distribution of CPPs in our dataset by (a) category, (b) station operator, and (c) vehicle model. “Starting a Charge” dominates across the overall dataset, with nearly half of all negative reviews mentioning this CPP. From plots (b,c), notable variance in CPP distribution can be observed from different station operators and vehicles.

We observed that some operators showed a widely different distribution of negative reviews across the six CPP categories when compared to their competitors, as seen in Figure 6b. For example, customers of Operator 1 reported far fewer issues with starting charging sessions than customers at other CSOs, leading to a higher percentage of issues relating to accessing chargers and feeling comfortable during their visits. Additionally, customers of Operator 1 reported almost no issues with contacting support staff, suggesting an effective customer support system. Operator 3 saw a lower percentage of customers struggling to complete their charge than the other operators, and customers of Operator 4 reported the fewest issues finding and accessing a charger. These insights serve to demonstrate how CSOs can leverage SCALER to pinpoint and address the most prevalent issues affecting their customers and compare their stations’ performance with their competitors. As shown in Figure 6c, drivers of different vehicle models encountered CPPs at disproportionate rates. Understanding these patterns could enable vehicle manufacturers to identify the specific issues that their models tend to encounter. Further implementation of SCALER on a larger dataset tagged with more metadata could also provide EV manufacturers with a comprehensive, unbiased comparison of vehicle performance to assist with root-cause analysis for increased reliability.

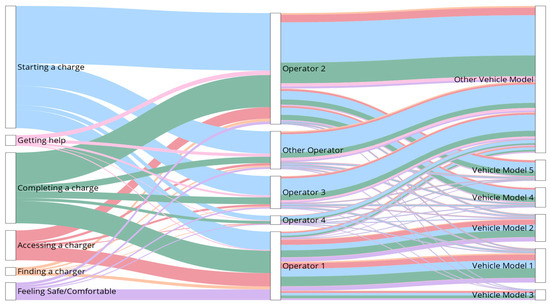

To investigate connections and interoperability between each CPP and individual CSOs and vehicle models, we also plotted a Sankey diagram (Figure 7). In Figure 7, the first, second, and third stages represent the number of reviews for each CPP category, CSO, and vehicle model, respectively. The thickness of each element represents the number of reviews for it. Although we only show the data for the four most prominent CSOs and five most prominent vehicle models, reviews related to all other CSOs and vehicle models are grouped under the Other Operator and Other Vehicle Model bins. Relations between these reviews could be investigated more rigorously in an analytics-focused study. The connections between CPPs, CSOs, and vehicle models could provide useful insights for a wide range of industry stakeholders and customers.

Figure 7.

Sankey diagram showing the relationship between each CPP category (leftmost stage) to individual station operators (center stage) and vehicle models (rightmost stage). The size of each bar represents the number of reviews belonging to the relevant classifier. Operators 1 and 2 make up most of the dataset, with roughly two-thirds of reviews being left at stations owned by these CSOs. The distribution of vehicle models is more diverse, though the five most popular EVs accounted for nearly half of all reviews.

The unique CPP distribution of each station operator demonstrates the potential value of using SCALER to analyze data from a single CSO, as every individual operator could extract tailored information that would help them improve the charging experience they provide to their customers. For example, Operator 1 could note how drivers of Vehicle Models 1 and 2 contributed to a large share of the CPPs reported at their stations, highlighting the importance of understanding and addressing problematic interactions with these specific vehicle models. Additionally, the manufacturer of Vehicle Model 5 could observe how most of their customers used stations owned by Operator 2, emphasizing the importance of working with this CSO to achieve better interoperability. From the customer perspective, if a prospective EV buyer lived in an area dominated by stations owned by Operator 3, they could investigate what vehicle models had drivers reporting the fewest issues at these stations to inform their purchase decision. Ultimately, if SCALER were used to analyze a nationwide dataset, it could paint a highly detailed picture of the EV customer experience in the United States, benefitting the EV industry as a whole.

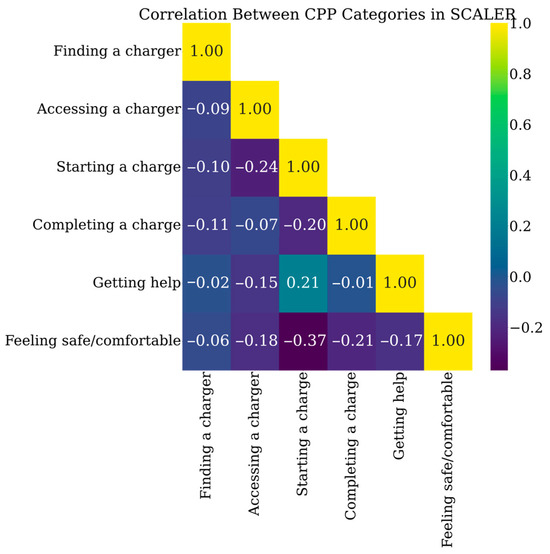

Figure 8 illustrates the correlations between various CPP categories, revealing some intriguing relationships. One notable observation is the weak negative correlation between the categories Starting a Charge and Feeling Safe/Comfortable. This pattern suggests that when customers encounter difficulties initiating a charge, their concerns about feeling safe and comfortable diminish, likely because their focus shifts away from environmental factors and towards resolving the immediate charging issue. Additionally, there is a weak positive correlation between Starting a Charge and Getting Help. This relationship is logical; customers facing challenges starting a charge were more inclined to seek assistance, potentially leading to increased reports of related issues, such as long wait times or connection problems. Finally, there is a weak negative correlation between Starting a Charge and Accessing a Charger. This could indicate that scenarios in which customers initially struggled to access a charger, but then did not face significant issues once charging began, were common. These insights enhance our understanding of the interplay between different CPPs and underscore the complexities of the EV charging customer experience.

Figure 8.

Correlation between CPP categories in our dataset. A positive correlation indicates that two CPPs are often mentioned together in a single review, while a negative correlation suggests that such coupling is unlikely. The only positive correlation is between “Starting a Charge” and “Getting Help”, and there are notable negative correlations between “Starting a Charge” and “Feeling Safe/Comfortable”, as well as between “Accessing a Charger” and “Starting a Charge”.

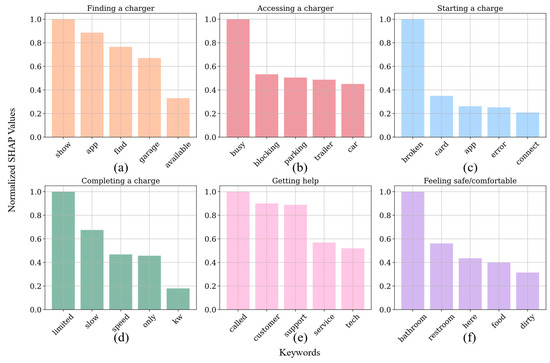

Figure 9 provides a SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis detailing the top five keywords for each CPP category, offering insights into customer mentality and the specific challenges EV charging customers encounter [37]. For the category of Finding a Charger, keywords, such as ‘show,’ ‘app,’ ‘find,’ ‘garage,’ and ‘available’ indicate prevalent issues with finding a charger that may be in garages, along with misleading availabilities. For Accessing a Charger, terms such as ‘busy’ and ‘blocking’ indicated issues with charger availability, and terms such as ‘parking’ and ‘trailer’ hint at issues with charger access and inability to charge with trailers, suggesting a need for better charging station layout and management. A keyword that dominated over others in reviews within the category Starting a Charge was the word ‘broken’. This indicates that customers may have attributed the inability to start a charge to broken hardware. The presence of keywords ‘app,’ and ‘connect’ also indicates frequent issues with problematic physical or communications connections and smartphone applications that were required to start a charge. In Completing a Charge, the keywords ‘limited,’ ‘slow,’ ‘speed,’ and ‘kw’ reflected issues with power delivery and slower-than-expected charging progress. Getting Help was characterized by the keywords, ‘called’, ‘customer,’ ‘support,’ ‘service,’ and ‘tech,’ indicating frustrations with customer service that could benefit from more efficient support processes. The Feeling Safe/Comfortable category featured words, such as ‘bathroom,’ ‘restroom,’ ‘food,’ and ‘dirty’ pointing to dissatisfaction with local facilities and services. These insights highlight specific areas where EV charging stakeholders can target improvements to enhance customer satisfaction.

Figure 9.

Analysis of the top 5 most influential words in each CPP category in our dataset: Finding a Charger (a), Accessing a Charger (b), Starting a Charge (c), Completing a Charge (d), Getting Help (e), and Feeling Safe/Comfortable (f). These are the words that most confidently allow SCALER to assign the relevant CPP classification to a review, and they demonstrate the common ways that consumers articulate the issues they encounter when charging their vehicles.

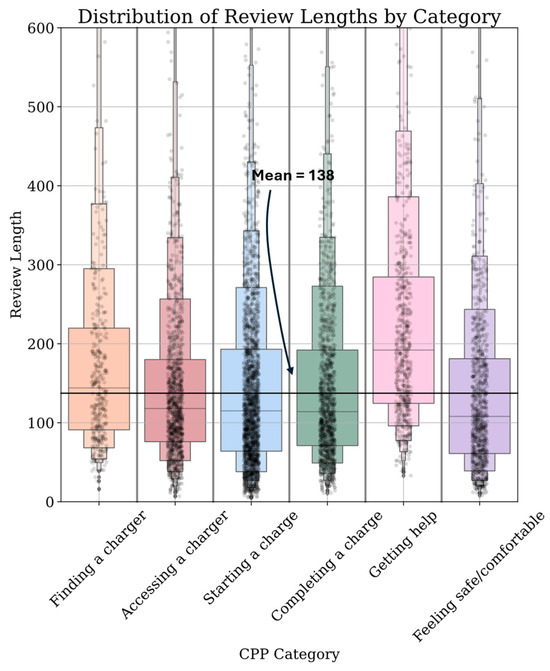

Finally, to delve deeper into the thought processes of customers, we examined the relationship between the lengths of reviews and CPP categories. This analysis, summarized in Table 7 and depicted in Figure 10, provides insights into the verbosity with which customers discuss issues related to EV charging. From the data presented, it is evident that review lengths vary significantly across different CPP categories. Notably, Getting Help records the longest average comment length at 230 words, with a correlation coefficient of 0.316, indicating that customers tended to provide more detailed descriptions when they encountered customer-service-related challenges. Conversely, reviews in the Feeling Safe/Comfortable category are typically shorter, averaging 139 words, meaning that safety and comfort concerns were usually expressed more succinctly. The other categories exhibit similar lengths, reflecting a moderate level of detail in customer feedback. Although these metrics may be valuable to understand how customers prioritize and articulate different types of pain points, due to the absence of strong correlations, more research is needed to truly understand the relationship between review lengths and CPPs.

Table 7.

CPP Categories and correlation with review length.

Figure 10.

Correlations between review lengths and CPP categories. The length of each review is denoted by a black dot in its relevant CPP category’s column. Reviews relating to “Getting Help” tended to be the longest by a noticeable margin, with an average comment length nearly 67% above the overall mean.

4. Discussion

Although previous studies have highlighted the benefits of analyzing customer reviews to understand and enhance the EV owner’s experience, there remains a significant gap in the standardized analysis of EV charging customer reviews. Our work introduces a substantial advancement in this area through the development of the SCALER framework, which systematically enhances the processing and understanding of a large quantity of EV charging customer reviews.

SCALER operationalizes this analysis through four distinct stages, starting with the standardization of CPPs into six clearly defined categories. This process, developed in collaboration with over 85 stakeholders in the ChargeX Consortium, establishes a foundational benchmark for categorizing and addressing customer feedback across the industry. SCALER then implements an innovative, active-learning style review labeling framework that significantly reduces the training burdens associated with modern deep learning methods, facilitating a scalable, data-driven approach to analyzing EV charging customer reviews. Furthermore, our approach lays a path that helps adapt state-of-the-art LLMs to the unique context of EV charging infrastructure, enabling meticulous analysis and categorization of a vast array of customer reviews to identify and understand the most prevalent issues encountered by EV charging customers.

In a case study, we analyzed and classified over 72,000 customer reviews using finetuned LLMs, achieving an F1 score of over 85%. This verified the effectiveness of SCALER as a practical solution to the challenges of analyzing unstructured customer review data. By doing so, we enhance the industry’s ability to understand and address CPPs to improve the EV charging experience, which will ultimately boost consumer confidence and support increased EV adoption. Looking ahead, we plan to extend this framework to calculate the ChargeX KPIs [14] that analyze station performance by connecting the outputs of SCALER and its CPP category classifications to actual EV charging data obtained via the Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP). While our validation encompasses comprehensive U.S. geographic coverage, future work may extend SCALER to international markets and non-English review platforms as global EV infrastructure expands.

Limitations

It is important to note that although the results presented by SCALER are motivating, our dataset of EV charging reviews may exhibit selection bias, as customers with negative experiences are more motivated to post feedback than those with routine sessions. Further, our analysis focuses exclusively on the U.S. market, and both our CPP taxonomy and findings reflect North American infrastructure and consumer expectations. International markets may require adapted categories, and our English-language models need retraining for non-English contexts. In our work, we adopt established hyperparameter values rather than exhaustive optimization, and deployment requires initial annotation of approximately 1800 reviews. Our classification framework necessarily simplifies complex individual narratives to enable quantitative analysis at scale. Despite these constraints, SCALER provides substantial value for North American charging infrastructure assessment with flexibility to adapt through retraining on new datasets.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, J.C., M.S. and P.R.; writing—review and editing, J.C., M.S., C.Q., B.V. and J.S.; graphic design, J.C. and M.S.; validation, J.C., M.S. and P.R.; software, J.C., M.S. and P.R.; methodology, J.C., M.S. and P.R.; conceptualization, J.C., M.S., C.Q. and B.V.; supervision, C.Q. and J.S.; resources, C.Q.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation of the U.S. Department of Energy and U.S. Department of Transportation. This research made use of the resources of the High Performance Computing Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under Contract No. DE-AC07-05ID14517.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available. Requests to access the datasets can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of members of the ChargeX Consortium’s Working Group 1: Defining the Charging Experience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

To improve the time-consuming process of manual labeling, in this work, we proposed the use of active learning. To represent the uncertainty implicit in this method, we utilized Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) [38,39]. BNNs are DNNs that incorporate prior probability distributions over a set of model parameters, denoted as ,

where can be a standard Gaussian prior. We define the likelihood model as follows:

for multi-label classification, where is the model output parameterized by . Here represents the sigmoid activation function and is a vector of length equal to CPP categories (). To perform approximate inference in the Bayesian DNN model, we used dropouts [32,33]. As demonstrated by Gal, Islam, and Ghahramani [30], dropout and other stochastic regularization techniques can be used for practical approximate inference in DNNs. Inference is conducted by training a model with dropout and maintaining dropout during inference to enable sampling from the approximate posterior. This approach is similar to that proposed by Gal, Islam, and Ghahramani [30] and employs approximate variational inference; the goal is to find within a tractable family that minimizes the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence to given a training set . Dropout can be interpreted as a variational Bayesian approximation, where the approximating distribution is a mixture of two Gaussians with small variances, and the mean of one of the Gaussians is fixed at zero. The uncertainty in the weights introduces prediction uncertainty by marginalizing over the approximate posterior using Monte Carlo integration:

with , where ) is the dropout distribution. Bayesian DNNs work well with small amounts of data and possess uncertainty information that can be used with existing acquisition functions. Such acquisition functions for the case of classification are available in the literature [38,39,40]. Given a model , a pool of labeled data , and inputs , an acquisition function is utilized by the active-learning system to determine the next query point,

There are various acquisition functions available, but for our specific task, we use the BALD acquisition function due to its several advantages, such as lower complexity, speed, and previous successes [40,41,42,43]. The BALD acquisition function is defined as

In this work, we use the extended version of the BALD algorithm [30] for multi-label classification. In our multi-label classification setting, is a binary vector for which each entry corresponds to the presence or absence of a particular label. For each label , the entropy is calculated using the predicted probability from the sigmoid function. The BALD score for each instance is then the sum of the individual entropies across all labels. Thus, this modified BALD acquisition function can be given by

where

and

Our approach uses the modified version of the BALD algorithm to manage multi-label contexts by incorporating a sigmoid function for each label , where represents each sample from the approximate posterior distribution during the Monte Carlo sampling. This modification enables the algorithm to independently assess uncertainty for each possible label, thereby pinpointing the most informative reviews for labeling across various categories. By adapting BALD for multi-label classification, we strategically select reviews that enhance information gain for each CPP category, thereby boosting the efficiency and precision of our labeling process. This enhancement ensures that our model focuses on the most valuable data points, reducing the overall effort required and increasing its ability to discern the complex and varied nature of customer feedback within the EV charging sector.

To facilitate practical implementation, we provide algorithmic pseudocode for our multi-label BALD acquisition function. The core modification from standard single-label BALD is the summation across all C equals six CPP category labels, with each label’s uncertainty calculated independently via sigmoid activation rather than through a shared softmax layer.

| Algorithm A1: Multi-Label BALD Sample Selection in SCALER. | ||||

| Input: | ||||

| Output: | with highest information value for labeling | |||

| For : | ||||

| //Sample from approximate posterior via dropout | ||||

| For : | ||||

| //Enable dropout during forward pass | ||||

| labels | ||||

| //Calculate BALD contribution from each label independently | ||||

| For : | ||||

| For : | ||||

| //Mutual information for this label | ||||

| Return | ||||

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Model Selection

We selected five model architectures to balance classification performance, computational efficiency, and reproducibility. For baselines, we implemented a DNN and 1D-CNN following Ha et al. [25] to assess whether transformer complexity yields meaningful performance gains. Among transformers, we chose RoBERTa and XLNet for their complementary pretraining approaches, demonstrated effectiveness on domain-specific text classification [33,34,35], and open-source availability through HuggingFace. RoBERTa optimizes BERT through dynamic masking [31], while XLNet uses permutation-based language modeling to capture bidirectional context [32]. We included GPT-3.5-turbo (gpt-3.5-turbo-0125) as a commercial state-of-the-art comparison to assess whether recent LLM advances justify API costs versus open-source alternatives. Our results show GPT-3.5-turbo achieves the highest performance (F1: 0.857), while RoBERTa provides competitive accuracy (sentiment: 0.892, classification F1: 0.768) at zero recurring cost, offering organizations viable options based on their resource constraints.

Appendix B.2. Practical Considerations

Practical deployment of SCALER requires consideration of computational costs and reproducibility constraints. Finetuning GPT-3.5-turbo-0125 through OpenAI’s API costs approximately $22, based on the model’s pricing of $0.50 per million input tokens and $1.50 per million output tokens as of December 2023. Subsequent inference on the remaining reviews from our analytics period (post-July 2022) cost approximately $34, yielding a total project cost of $56, or roughly $0.005 per review analyzed. For comparison, manual expert annotation and analysis at a conservative rate of 30 reviews per hour would require approximately 374 labor hours for the same 11,218 reviews, costing $5610 at a minimum wage of $15 per hour for the human labeler. Organizations prioritizing cost minimization or requiring full reproducibility can employ the finetuned RoBERTa model, which, as shown in Table 4, achieves 89.2 percent accuracy using only open-source tools and moderate computational resources. The RoBERTa model requires approximately 0.6 h of finetuning time on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU with zero inference costs. This analysis confirms that SCALER offers both high-performance and economically accessible implementation pathways, with the active learning framework dramatically reducing the data labeling burden that typically constrains deep learning approaches. All model specifications, including version identifiers, hyperparameters, and hardware requirements, are documented in Table A1 to ensure full reproducibility.

Table A1.

Model implementation specifications for reproducibility.

Table A1.

Model implementation specifications for reproducibility.

| Model | Version/Source | Hardware | Hyperparameters | Training Duration | Inference Cost | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RoBERTa | HuggingFace: roberta-base | Single NVIDIA A100 GPU (40 GB) | , Weight decay: 0.01, Batch size: 16, Epochs: 10, Dropout: 0.1 | 0.6 h | Null | Yes |

| XLNet | HuggingFace: xlnet-base-cased | Single NVIDIA A100 GPU (40 GB) | , Weight decay: 0.1, Batch size: 16, Epochs: 10, Dropout: 0.1 | 0.8 h | Null | Yes |

| GPT-3.5-turbo | OpenAI: gpt-3.5-turbo-0125 | Temperature: 0.3, Max tokens: 8, Finetuning epochs: 3 | OpenAI API | 1.2 h (API processing) | $0.002/review ($0.50/1M input + $1.50/1M output tokens) | No (API access required) |

Appendix B.3. Hyperparameter Configurations

Our hyperparameter choices follow established recommendations from the original model papers, representing well-validated configurations that reduce the need for extensive task-specific optimization while ensuring robust performance.

For RoBERTa models, we used a learning rate of (the standard BERT finetuning recommendation), weight decay of 0.01 for L2 regularization, batch size of 16 to maximize GPU memory utilization on our NVIDIA A100 hardware (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and trained for 10 epochs until convergence. XLNet followed the same configuration except for increased weight decay of 0.1, as its authors recommend stronger regularization for this architecture.

For DNN and 1D-CNN baselines trained from scratch, we used a higher learning rate of with Adam optimizer (appropriate for networks without pre-trained representations), 20 percent dropout, and 100 epochs to reach performance ceiling. GPT-3.5-turbo finetuning followed OpenAI’s recommended practices: three epochs (reflecting its massive pretraining scale requiring minimal adaptation) and a temperature of 0.3 during inference.

While we did not perform exhaustive hyperparameter searches due to computational constraints, our configurations represent well-validated choices from the literature. Future implementations may benefit from task-specific optimization, though gains are expected to be modest given our choices already follow established best practices.

Appendix C

Examples of sentiment analysis (Table A2) and review classification (Table A3) in inference mode using SCALER are presented below.

Table A2.

Example customer reviews and their sentiment given by SCALER.

Table A2.

Example customer reviews and their sentiment given by SCALER.

| Review Example | Output Sentiment |

|---|---|

| “196 mph. Nice attendant. No idea how much I’m about to pay to park for a few hours and charge, but convenient.” | Positive |

| “Stopped here on my drive from Boise to Salt Lake. Got a solid 150 kW the whole session, and there’s a Starbucks across the street. Wish more sites were like this one” | Positive |

| “It was like 20F this morn and my car still hit full charge rate after a few mins warmup. Pretty solid charger tbh” | Positive |

| “205 Wawa is great. Tricky turns for entry.” | Positive |

| “Charged ok, but rate was kinda slow (around 60 kw?). Not bad tho, got what I needed.” | Neutral |

| “Had to retry once, maybe bad cable contact. Once started it was stable. meh overall.” | Neutral |

| “App froze once but restarted fine. Took ~35 min to go 40→90%. okayish.” | Neutral |

| “136 kw on 2A. No one else here. Much faster than last year when I had to keep trying every stall to get it to work.” | Negative |

| “1A also broken, no pins” | Negative |

| “2 & 3 down. Stinky. Charging well on 4” | Negative |

| “2 slots ICEd out by big truck and van. But could not get close enough anyway on the other two slots, snow not cleared enough and slots very tight. The spots are angled with another row of angled parking across. This requires you to turn around and back in between other angled vehilces all around all of which are trucks and vans making it difficult to get in there. They are on the network and appear to be free.app reports 8 chargers but I only saw 4.” | Negative |

Table A3.

Example customer reviews and their CPP categories given by SCALER.

Table A3.

Example customer reviews and their CPP categories given by SCALER.

| Review Example | CPP Categories Mentioned |

|---|---|

| “The charger was too slow, and the payment process failed multiple times. Very frustrating!” | Starting a Charge, Completing a Charge |

| “The 2 chargers on the right phong and luzena would not charge called support but support could not fix” | Starting a Charger, Getting Help |

| “Brand new station had trouble starting the charge but after some wait customer service quickly rectified the problem” | Starting a Charger, Getting Help |

| “Neither of 2 chargers worked with the combo charger continually said car wasnt plugged in or would start charge then stop called help line as suggested by the app they did a soft reboot but no help the cords are so short that they seem to crimp even when pulled up to nearly touching the charger considering that i paid 2 to park here while i charged having these machines not work is pretty frustrating” | Accessing a Charger, Starting a Charger, Getting Help |

| “Charger 1 is completely offline, black screen. Charger 3 CCS is down, chademo only. Charger 2 is in limp mode. Maxed out at 30–40 kw. Contacted support and they are not aware.” | Starting a Charger, Completing a Charge, Getting Help |

| “App said 10 min wait, but no other cars here” | Finding a Charger |

| “Hard to find from west alabama st enter small narrow entrance for thegalleria parking go down to ll2 green” | Finding a Charger |

| “Fast tight garage and you have to travel to the top floor open air so can be very cold no wifi and no facilities you have to leave the garage for that” | Finding a Charger, Accessing a Charger, Feeling Safe and Comfortable |

| “one lexus blocking a charger but others are open” | Accessing a Charger |

| “Charger 4 limited to 40 kw” | Completing a Charge |

| “Charger 3 failed, charger 2 worked even though the app said it was unavailable, but was doing the variable all over the place charging and overall slow. Moved to #1 which seemed to work as it should” | Finding a Charger, Starting a Charge, Completing a Charge |

References

- Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Shi, H.; Geng, Y. Hidden benefits of electric vehicles for addressing climate change. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, M.; Alexander, M.; Arent, D.; Bazilian, M.; Cazzola, P.; Dede, E.M.; Farrell, J.; Gearhart, C.; Greene, D.; Jenn, A.; et al. The rise of electric vehicles—2020 status and future expectations. Prog. Energy 2021, 3, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguesa, J.A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F.J.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. A review on electric vehicles: Technologies and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Trancik, J. Re-examining rates of lithium-ion battery technology improvement and cost decline. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1635–1651. Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2021/ee/d0ee02681f (accessed on 10 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shuang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Tang, S.; Wu, X.-L.; Bai, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J. Recent Progress in Sodium-Ion Batteries: Advanced Materials, Reaction Mechanisms and Energy Applications. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzel, N.; Hasanuzzaman, M. An empirical analysis of electric vehicle cost trends: A case study in Germany. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T. Long-Range EVs Now Cost Less Than the Average New Car in the US. Bloomberg, 7 June 2024. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-07/long-range-evs-now-cost-less-than-the-average-us-new-car (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- IEA. Trends in Electric Cars—Global EV Outlook 2024—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars. (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Woody, M.; Keoleian, G.A.; Vaishnav, P. Decarbonization potential of electrifying 50% of U.S. light-duty vehicle sales by 2030. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A.; Ross, S.; Tyson, A. How Americans View Electric Vehicles; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/07/13/how-americans-view-electric-vehicles/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Hu, X.; Zhou, R.; Wang, S.; Gao, L.; Zhu, Z. Consumers’ value perception and intention to purchase electric vehicles: A benefit-risk analysis. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 49, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Z.A.; Ko, J.; Jang, J. Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles: Influences of User Attitude and Perception. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Yang, M. Changes in consumer satisfaction with electric vehicle charging infrastructure: Evidence from two cross-sectional surveys in 2019 and 2023. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.W.; Cardinali, S.; Clifford, J.; Houck, K.; Moriarty, K.; Savargaonkar, M.; Smart, J.G.; Smith, D.E.; Varghese, B.J. Customer-Focused Key Performance Indicators for Electric Vehicle Charging; INL/RPT--24-77388-Rev000, 2377347; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2024.

- Savargaonkar, M.; Varghese, B.; Houck, K. Recommendations for Minimum Required Error Codes for Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure; INL/RPT--23-74154-Rev000, 2369573; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023.

- Malarkey, D.; Singh, R.; MacKenzie, D. Customer Experience at Public Charging Stations and Its Effects on the Purchase and Use of Electric Vehicles; INL/RPT--23-74951-Rev000, 2293486; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023.

- Brown, A.; Cappellucci, J.; Heinrich, A.; Cost, E. Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Trends from the Alternative Fueling Station Locator: Third Quarter 2023; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024.

- Savargaonkar, M.; Varghese, B.J.; Houck, K. Implementation Guide for Minimum Required Error Codes in Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure; INL/RPT--23-74833-Rev000, 2369572; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023.

- ConsumerAffairs®. How Many EV Charging Stations Are in the U.S.? 2024. 20 February 2024. Available online: https://www.consumeraffairs.com/automotive/how-many-ev-charging-stations-are-in-the-us.html (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Karanam, V.C.; Tal, G. How Disruptive are Unreliable Electric Vehicle Chargers? In Proceedings of the Empirically Evaluating the Impact of Charger Reliability on Driver Experience, Rochester, NY, USA, 8 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, D.; Cullen, C.; Bryan, M.M.; Cezar, G.V. Reliability of open public electric vehicle direct current fast chargers. Hum. Factors 2023, 66, 2528–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Jang, H. Building an interoperability test system for electric vehicle chargers based on ISO/IEC 15118 and IEC 61850 standards. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Francis, A.; Hollauer, C.; Lawson, M.C.; Shaikh, O.; Cotsman, A.; Bhardwaj, K.; Banboukian, A.; Li, M.; Webb, A.; et al. Reliability of electric vehicle charging infrastructure: A cross-lingual deep learning approach. Commun. Transp. Res. 2023, 3, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Chang, C.-T.; Liu, Z. Sentiment analysis of online reviews for electric vehicles using the SMAA-2 method and interval type-2 fuzzy sets. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 147, 110745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Marchetto, D.J.; Dharur, S.; Asensio, O.I. Topic classification of electric vehicle consumer experiences with transformer-based deep learning. Patterns 2021, 2, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetto, D.J.; Ha, S.; Dharur, S.; Asensio, O.I. Extracting User Behavior at Electric Vehicle Charging Stations with Transformer Deep Learning Models. In Proceedings of the CARMA 2020—3rd International Conference on Advanced Research Methods and Analytics, Virtual, 8–9 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MotorTrend. Lessons Learned While Road Tripping an EV. 12 July 2022. Available online: https://www.motortrend.com/features/lessons-learned-road-tripping-ev/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- MotorTrend. Road Trips in Our Long-Term EVs Have Been … Interesting. 27 January 2023. Available online: https://www.motortrend.com/reviews/road-tripping-in-our-long-term-electric-test-cars/ (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- J.D. Power. Electric Vehicle Experience (EVX) Public Charging Study. Available online: https://www.jdpower.com/business/electric-vehicle-experience-evx-public-charging-study (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Gal, Y.; Islam, R.; Ghahramani, Z. Deep bayesian active learning with image data. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 11–15 August 2017; pp. 1183–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:190711692. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.R.; Le, Q.V. Xlnet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08237. [Google Scholar]

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large Language Models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26839–26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.U.; Qureshi, R.; Shah, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J.; Mirjalili, S. A survey on large language models: Applications, challenges, limitations, and practical usage. TechRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Lee, C.P.; Anbananthen, K.S.M.; Lim, K.M. RoBERTa-LSTM: A hybrid model for sentiment analysis with transformer and recurrent neural network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21517–21525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, A.; Van Amersfoort, J.; Gal, Y. Batchbald: Efficient and diverse batch acquisition for deep bayesian active learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, E.; Škrlj, B.; Lavrač, N.; Pollak, S.; Robnik-Šikonja, M. BERT meets shapley: Extending SHAP explanations to transformer-based classifiers. In Proceedings of the EACL Hackashop on News Media Content Analysis and Automated Report Generation, Virtual, 19 April 2021; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Gal, Y. Dropout inference in bayesian neural networks with alpha-divergences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 15 August 2017; pp. 2052–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Savargaonkar, M. Custom AI Architectures for Predictive Analytics Using Bayesian Statistics and Deep Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Bayesian convolutional neural networks with Bernoulli approximate variational inference. arXiv 2015, arXiv:150602158. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneke, S. Theory of disagreement-based active learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2014, 7, 131–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]