Abstract

While numerous studies have investigated the factors associated with autonomous delivery vehicles (ADVs), there remains a paucity of research concerning consumers’ intentions to utilize these technologies. Prior research has predominantly concentrated on the effects of individual variables on outcomes, often neglecting the synergistic influence of various factors on consumer intention. This study seeks to examine the collective impact of pro-environmental motives (including awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility), normative motives (such as subjective norms and personal norms), risk factors (COVID-19 risk and delivery risk), and individual characteristics (including trust in technology and innovation) on consumers’ intentions to adopt ADVs. Employing a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), this research analyzed data from 561 Chinese consumers collected via an online platform. The results yielded six distinct solutions, indicating that multiple combinations of antecedent factors could lead to a higher intention to adopt compared to any singular factor. These findings offer significant theoretical and practical implications for the effective implementation of ADVs in the last-mile delivery sector.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Significant advancements have been observed in the logistics and express delivery sectors, largely attributed to the rapid growth of e-commerce in recent years [1,2,3]. Data from the World Economic Forum indicates that the demand for urban last-mile delivery, propelled by e-commerce, is projected to increase by 78% by 2030 [4]. Additional statistics reveal that the total volume of postal express deliveries is anticipated to reach 28.52 billion by 2022, reflecting a year-on-year growth of 5%. The resurgence of the pandemic in 2021 resulted in a 29.9% increase in the business volume of express delivery service providers in China [5]. Furthermore, a recent report indicates that by the end of June 2022, China’s express delivery volume surpassed 51.22 billion shipments, marking a 3.7% increase compared to the previous year [6]. In light of the substantial express delivery volume, particularly influenced by the pandemic, consumer demand for last-mile delivery services has surged, presenting both significant opportunities and challenges for e-commerce and express delivery enterprises [1,3,7].

ADVs, or drones, are garnering increasing interest due to their non-contact, energy-efficient, and environmentally sustainable characteristics [8,9]. ADVs amalgamate advanced deep learning computational capabilities, robust general-purpose computing power, and customizable interface functionalities to meet intricate user requirements. This integration facilitates the provision of computational resources and interface support essential for the perception, decision-making, and control processes involved in autonomous driving [7,8]. Users are afforded the convenience of scheduling their preferred delivery time and location through mobile applications. Upon the arrival of the ADVs, consumers receive notifications via their mobile devices to finalize the delivery, which can be completed by entering a designated pick-up code. The implementation of ADVs enhances the efficiency and punctuality of delivery services, significantly minimizing human error during the delivery process, thereby allowing customers to benefit from multiple deliveries within a condensed timeframe. It is anticipated that 80% of parcel deliveries will be automated for pickup within the next decade [10,11]. A report co-authored by the China Electric Vehicle Association and Meituan suggests that the market for autonomous delivery could reach CNY 750 billion when considering a comprehensive view of the stock market. With the continued expansion of the food and beverage takeaway, new retail, and terminal delivery markets, the autonomous delivery sector is projected to attain a trillion-dollar valuation by 2030 [12]. On 20 June 2022, the Joint Innovation Center for Autonomous Delivery was established, with its members collaborating to advance solutions for autonomous delivery scenarios, including testing standards, access certification systems, and transportation management systems, thereby fostering the standardized and sustainable development of the autonomous delivery industry [13]. On 27 December 2021, China’s inaugural driverless logistics vehicle, named “Pioneer,” underwent testing at ZTO Express’s internal site, demonstrating capabilities such as stage parking, crosswalk parking, and obstacle avoidance. This vehicle is notable for being completely autonomous, devoid of passengers or safety personnel, and is equipped with Huawei’s MDC intelligent driving computing platform, designed to operate at speeds exceeding 70 km/h [14]. Concurrently, various government entities in China have extended substantial support and subsidies for infrastructure development to facilitate the integration of autonomous delivery within urban communities [4,15,16]. Moreover, as a manifestation of technological innovation within the logistics sector, autonomous delivery has played a crucial role in combating the pandemic, establishing a foundational framework for future commercialization [2,7,17,18]. In the post-pandemic context, the integration of autonomous delivery with urban logistics systems has the potential to unlock greater industrial value by streamlining the upstream and downstream processes of logistics delivery.

As a sophisticated innovation within the transportation industry, autonomous delivery has attracted considerable attention. Certain regions have implemented incentives and subsidies to promote technological development and testing. Nevertheless, autonomous delivery currently encounters challenges related to technology, business models, regulatory standards, and infrastructure development [7]. These challenges have resulted in a general lack of awareness among users regarding ADVs, leading to a cautious approach toward their adoption. Despite the substantial potential of ADVs within the autonomous delivery market, the realization of their benefits is contingent upon consumer perceptions and acceptance [8]. Consequently, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the factors that influence consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs.

1.2. Motivations

A variety of factors impact consumer adoption behavior concerning ADVs, especially among logistics service providers who are actively pursuing effective strategies to meet the personalized demands of consumers, particularly in the context of increasing manual delivery expenses [1]. Trust in this technology, as an inherent psychological state, significantly impacts consumer decision-making and adoption behavior [7]. Furthermore, ref. [16] posits that trust plays a critical role in public acceptance of shared ADVs. Consumer innovativeness can also substantially affect decision-making behavior, particularly among individuals within high-tech demographics who are more inclined to experiment with new technologies or services upon learning about them [1]. Research conducted by [7] indicates that consumer innovations positively influence the adoption behavior of ADVs.

In the context of emerging technologies, certain individuals are particularly susceptible to the influence of reference groups—such as family, friends, and colleagues—who advocate for the use of ADVs as a means of effectively navigating their environments. Consequently, normative factors, especially subjective norms, exert a significant influence on consumer adoption behavior [7]. Given that ADVs are characterized as low-emission products, their adoption can be viewed as a manifestation of environmentally conscious consumer behavior. Environmentally aware individuals may fulfill their ecological commitments by purchasing green products or engaging in environmentally friendly practices. The pre-environmental variables of awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility, as discussed in this study, can drive the adoption of ADVs by shaping consumers’ personal norms, which in turn significantly influence their behavioral intentions to adopt such vehicles [19].

Moreover, the autonomous operation of ADVs raises concerns regarding potential accidents or injuries to pedestrians due to malfunctions, as well as the risk of lost or damaged packages resulting from collisions with human-driven vehicles. These factors heighten the perceived delivery risks among consumers. Additionally, concerns regarding personal privacy and information security are recognized as critical determinants of consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these concerns, leading many consumers to prefer contactless delivery services following online orders [2,18,20]. Thus, both consumer-perceived delivery risks and COVID-19-related risks significantly influence consumer attitudes toward and the acceptance of ADVs. While each of these factors independently affects the intention to use ADVs, further investigation is warranted to understand how their interplay influences consumers’ willingness to adopt these vehicles. Consequently, this study seeks to address the following question: How does the combination of these factors affect consumers’ intention to use ADVs?

Currently, much of the existing research primarily examines autonomous vehicles from a passenger transport perspective [10,21,22,23,24,25]. However, there is a notable scarcity of studies focusing on the willingness to utilize ADVs for goods transportation [11,20,26,27,28]. Although various quantitative methodologies, such as the technology acceptance model, the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology [7,8,28], and task technology fit [29], have been employed to analyze the effects of different antecedents on consumers’ intentions to use ADVs, these studies predominantly highlight the impact of individual factors without elucidating the configurational effects on consumers’ intentions. Furthermore, most prior research on ADVs has been conducted in developed countries, such as the United States [11,20], Germany [7], and Spain [30], with limited exploration of ADVs adoption in developing countries, particularly regarding Chinese consumers’ intentions to use ADVs. This study aims to investigate the combined effects of pro-environmental motives (awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility), normative motives (subjective norm and personal norm), risk factors (COVID-19 risk and delivery risk), and individual characteristics (trust in technology and innovation) on consumers’ intentions to use ADVs for delivery services, specifically from the perspective of goods recipients in China.

The structure of the study is as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review and the proposed hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, while Section 4 details the data analysis and fsQCA results. Section 5 summarizes the conclusions, and Section 6 discusses the theoretical contributions and practical implications. Finally, Section 7 addresses the limitations of the study and suggests directions for future research.

2. Related Literature

2.1. Previous Studies on the Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles

Autonomous vehicles represent a significant disruptive force within the transportation sector. Numerous researchers have engaged in studies and analyses pertaining to this domain [21,22,23,25,31,32,33,34]. For instance, ref. [34] assessed the efficacy of advanced driving assistance systems, while [35] explored user intentions regarding the adoption of automated road transport systems. In several Chinese cities, including Suzhou, Shenzhen, and Zibo, ADVs developed by Unity-Drive Innovation (UDI) have successfully completed over 2500 independent food deliveries to communities experiencing supply disruptions [31]. In the United States, Nuro has responded to the shortage of drivers and the demand for contactless delivery services by creating two autonomous vehicles designed for the delivery of goods to local retail partners [36]. Furthermore, ref. [27] conducted an analysis comparing the performance of three categories of autonomous vehicles—drones, sidewalk autonomous delivery robots (SADRs), and road autonomous delivery robots (RADRs)—with respect to vehicle miles traveled, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions. According to [37], autonomous delivery robots (ADRs) are capable of moving at pedestrian speeds to reach consumer-designated locations for last-mile deliveries. Additionally, ref. [8] indicated that ADVs have transformed the last-mile delivery paradigm into a more sustainable and customer-oriented approach. In summary, ADVs facilitate quicker and more environmentally sustainable deliveries compared to traditional delivery vehicles, such as vans or trucks, thereby addressing challenges related to delivery time constraints and efficiency, ultimately enhancing customer satisfaction.

2.2. Potential Factors Influencing Consumers’ Adoption Behaviors of ADVs

The present study primarily examines the configurational impact of pro-environmental motives (specifically, awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility), normative motives (including subjective norm and personal norm), risk-related motives (COVID-19 and delivery risks), and individual characteristics (such as trust in technology and innovation) on consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs. The constructs utilized in this research are derived from the existing literature, as detailed in Table 1.

2.2.1. Pre-Environmental Motives

The normative activation model (NAM) posits that individuals who engage in pro-environmental behaviors tend to possess a heightened awareness of the outcomes of their actions and attribute responsibility for these outcomes to themselves [38,39]. Research conducted by [19] indicates that personal norms can be activated to promote pro-environmental behaviors only within specific contexts, which are primarily driven by awareness of consequences (AC) and ascription of responsibility (AR). AC refers to an individual’s recognition that their failure to engage in certain behaviors results in negative consequences for others or the environment [19]. Furthermore, the findings of [40] suggest that consumers can effectively fulfill their environmental commitments and project a green image through the adoption of electric vehicles. The authors of [41] contend that the integration of electric vehicles can lead to a reduction in CO2 emissions associated with personal transportation, and that consumers who adopt such vehicles are perceived as environmentally conscious, thereby enhancing their self-image and encouraging others to adopt similar behaviors.

The implementation of ADVs is anticipated to yield substantial environmental and economic advantages, including decreased energy consumption, reduced carbon dioxide emissions, and enhanced space utilization [26,27,28,42,43]. Consequently, this study characterizes ADVs as pro-environmental products. Consumers exhibit a greater willingness to accept the risks associated with operating a self-driving vehicle that offers environmental benefits [42]. Research by [27] indicates that driverless vehicles have the potential to lower energy consumption and CO2 emissions in comparison to traditional trucking methods. According to [44], drone deliveries offer enhanced environmental advantages compared to traditional truck deliveries, particularly when the delivery locations are situated near a warehouse or when the number of delivery points is restricted. Moreover, ref. [20] demonstrates that tech-savvy consumers residing in urban environments are inclined to pay for autonomous delivery services.

The theory of symbolic interaction suggests that consumers’ self-perceptions influence their behaviors, and that an individual’s perception of others’ reactions is, to some extent, reflective of those reactions [45]. One of the motivations for the market introduction of ADVs is to mitigate the carbon emissions and energy challenges associated with traditional fuel-powered delivery vehicles. Companies that promote an environmental ethos are likely to take their commitment to the ecosystem seriously and manifest their green image through action, thereby embracing and adopting the delivery services offered by ADVs. As articulated by [46], pro-environmental motives (AC and AR) significantly affect users’ adoption of green technologies. Therefore, this study posits that pro-environmental motives (AC and AR) play a crucial role in shaping consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs.

2.2.2. Normative Motives

The adoption of energy-efficient ADVs can be viewed as an ethical imperative, as it is incumbent upon consumers to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions associated with transportation [25]. Prior research has indicated that various normative motives, including internal moral compasses, personal values, and social norms, facilitate the acceptance of environmentally sustainable products and services among consumers [25]. According to [46], individuals often contemplate their social identity and status prior to making purchasing decisions, striving to engage in behaviors that are deemed socially acceptable. In the context of ADV usage, consumer decisions are significantly shaped by the perspectives of family members, friends, colleagues, and other social circles; the actions of early adopters can further influence those in their vicinity to adopt similar behaviors [7]. Furthermore, numerous studies have established that personal norms serve as one of the most direct and potent predictors of consumers’ intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [19,38,39,47,48]. The activation of normative motives encourages individuals with a heightened sense of personal and social responsibility to engage in behaviors that are socially desirable [40]. Consequently, normative factors, encompassing both subjective and personal norms, play a crucial role in shaping consumers’ willingness to utilize ADVs.

2.2.3. Risk Motives

Perceived risk is a critical determinant affecting consumers’ readiness to embrace emerging technologies [28]. During the delivery process, ADVs may pose risks to pedestrians or nearby structures if their automation level is insufficient. Moreover, the novelty of autonomous delivery technology may lead consumers to harbor concerns regarding performance risks and to express skepticism towards self-driving vehicles, particularly regarding potential privacy infringements by third-party entities for commercial gain. Delivery risk, as a facet of perceived risk, significantly influences consumers’ decision-making processes regarding the adoption of ADVs. Extensive research underscores the relevance of perceived risk in the context of information technology adoption [8,49]. For instance, ref. [49] demonstrated that perceived risk substantially affected consumers’ attitudes and willingness to utilize drones. Additional studies have indicated that perceived risk considerably impacts consumers’ readiness to adopt emerging technologies, such as mobile payment systems. Specifically, ref. [8] found that perceived risk adversely influenced the behavioral intention to use ADVs, with the term “perceived risk” in this context referring to the potential hazards associated with employing ADVs for delivery purposes. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the focus on contactless delivery services, as this approach minimizes interactions between consumers and delivery personnel, thereby enhancing safety for both parties and significantly reducing exposure risks [2,18]. The authors of [18] also observed that pandemic-related risks could affect consumers’ behavioral intentions. Consequently, this study identifies delivery risk and COVID-19 risk as primary factors influencing consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs.

2.2.4. Individual Characteristics

Individual characteristics can significantly impact consumer decision-making processes, including levels of trust and [50] consumer innovativeness regarding emerging technologies [7]. Trust in technology posits that the actions of technology providers align with consumers’ psychological expectations [21,51]. Various factors have been identified in the literature concerning the adoption behaviors associated with autonomous vehicles [11,16,22,23]. The research of [52] has demonstrated that trust influences consumer satisfaction and the ongoing willingness to utilize such technologies. Furthermore, it has been established that trust in technology plays a crucial role in online shoppers’ readiness to engage with self-delivery vehicles [7]. ADVs are equipped with advanced information collection and intelligent navigation systems that enable them to autonomously perceive their environment, thereby ensuring the safety of both vehicles and pedestrians [7,10]. Additionally, ADVs are recognized for their energy efficiency and reduced environmental impact compared to traditional, energy-intensive transportation methods. These attributes contribute to heightened consumer trust and subsequently shape consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward the use of ADVs [8,11,42].

Innovation has been identified as a significant determinant influencing consumers’ intentions to adopt emerging technologies, such as mobile commerce services [53], mobile payments [54,55], smartwatches [56], and smartphone diet applications [57]. The diffusion of innovation theory posits that individuals with innovative ideas are more inclined to seek out and embrace novel concepts and adopt innovative behaviors at an earlier stage than their peers [1,23]. Previous research has also indicated that innovation exerts a direct influence on perceived usefulness [55] and the intention to utilize these technologies [53]. Furthermore, ref. [7] demonstrated that innovation positively affected consumers’ willingness to adopt ADVs. Consequently, our study posits that trust in technology and innovation significantly impact consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs.

2.3. The Combination of Different Motives for Consumers’ Intention to Use ADVs

A substantial body of research indicates that various motivational factors can be synthesized to enhance consumers’ intentions to adopt new technologies [58]. The NAM posits that individuals with pre-environmental motives, such as awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility, are likely to cultivate positive personal norms and behavioral intentions [19,38,39]. This suggests that pre-environmental motives can influence normative motives, thereby collectively encouraging consumers to engage in environmentally sustainable behaviors. Furthermore, in response to contemporary policy imperatives regarding carbon neutrality and peak carbon emissions, as well as the challenges posed by ongoing public health crises, numerous organizations have initiated green innovation initiatives and developed advanced technological products. Environmentally conscious and innovative consumers are inclined to proactively explore and utilize these products or services as a means of mitigating the perceived risks associated with COVID-19. Concurrently, these consumers often assume the role of opinion leaders, being among the first to share their experiences through social channels, thereby fulfilling societal expectations and enhancing their social standing. In this context, individual characteristics, environmental motives, and risk factors collectively influence normative motives, and the interplay of these four motivational dimensions serves to bolster consumer adoption intentions. Consequently, we propose the following proposition:

Proposition 1.

Diverse motivational factors mutually reinforce one another and collectively impact consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs.

Table 1.

The measurement of all the scales.

Table 1.

The measurement of all the scales.

| Construct | Item | Measurement | Adapted From |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of consequences (AC) | AC1 | Global warming is a social problem. | [45] |

| AC2 | Saving energy helps to reduce global warming. | ||

| AC3 | Energy depletion is a global problem. | ||

| Ascription of responsibility (AR) | AR1 | I feel a shared responsibility for the energy problem. | [45,59] |

| AR2 | I feel a shared responsibility for the depletion of resources. | ||

| AR3 | I feel jointly responsible for global warming. | ||

| Subjective norms (SNs) | SN1 | Most of the people who are important to me think that I should use delivery services provided by ADVs to receive deliveries, rather than other delivery methods. | [60] |

| SN2 | Most of the people who are important to me want me to use delivery services provided by ADVs to receive deliveries, rather than other delivery methods. | ||

| SN3 | Those people whose opinions I value would prefer me to use delivery services provided by ADVs to receive deliveries rather than any other methods | ||

| SN4 | People who influence my behaviors think I should use delivery services provided by ADVs to receive deliveries. | ||

| Personal norms (PNs) | PN1 | I think I should protect resources and the environment to the best of my ability. | [61] |

| PN2 | To reduce energy waste, I think it is my responsibility to use ADVs to receive deliveries. | ||

| PN3 | No matter what others do, I would use ADVs in a green way to receive deliveries. | ||

| Trust in technology (TIT) | TIT1 | I think ADVs are generally reliable. | [7] |

| TIT2 | I find it trustworthy to pick up deliveries from ADVs. | ||

| TIT3 | I think it is safe to pick up the deliveries from ADVs. | ||

| TIT4 | The delivery information provided by ADVs is trustworthy. | ||

| Innovation (IN) | IN1 | If I heard about new information technology, I would look for ways to experiment with it. | [7,62] |

| IN2 | Among my peers, I am usually the first to try out new information technologies. | ||

| IN3 | I like to experiment with different features of new products. | ||

| Delivery risk (DR) | DR1 | It is risky to deliver goods using ADVs. | [18,49] |

| DR2 | It is dangerous to deliver goods using ADVs. | ||

| DR3 | As a delivery method, the use of ADVs would expose me to overall risks. | ||

| DR4 | Packages may be damaged when ADVs are used for delivery. | ||

| COVID-19 risk (CR) | CR1 | COVID-19 will threaten my health to a great extent. | [17] |

| CR2 | COVID-19 will greatly threaten my physical and mental health. | ||

| CR3 | I am worried about any long-term financial influence from contracting COVID-19 | ||

| CR4 | I am very worried about becoming infected with COVID-19 disease. | ||

| Intention (IN) | INT1 | I will choose delivery services provided by ADVs to receive packages in the future. | [8,62] |

| INT2 | I would recommend my friends or relatives use delivery services provided by ADVs to complete deliveries | ||

| INT3 | In the near future, I plan to use delivery services provided by ADVs to complete deliveries. |

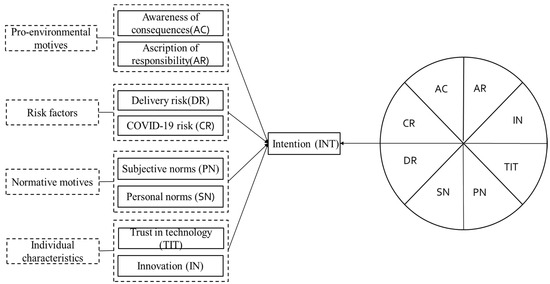

Based on this, the present study utilized the fsQCA methodology, positing that consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs represent a multifaceted behavioral phenomenon influenced by the interaction of pro-environmental motives (AC and AR), normative motives (SNs and PNs), risk motives (CR and DR), and individual characteristics (TIT and IN). The configurational model proposed herein is illustrated in Figure 1. This research aimed to address the inquiry regarding the configurational pathways that lead to the desired outcome—namely, the intention to use ADVs—and to identify which pathway possesses greater explanatory power concerning the mechanisms that induce high or low intentions. Ultimately, the study endeavored to elucidate the underlying logic that drives consumers to adopt ADVs.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework and configurational model.

3. Methodology

3.1. fsQCA

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a methodological approach grounded in set theory, specifically utilizing Boolean algebra and fuzzy set theory. fsQCA, a contemporary variant of QCA, enhances the assessment of consistency by employing set theory, which allows for the incorporation of continuous and interval scale variables in relation to causal conditions and outcomes. A key distinction of fsQCA from traditional regression analysis lies in its assumption of asymmetric relationships, as well as its recognition of equality and causal complexity. Consequently, we utilized fsQCA to elucidate the intricate patterns of causality among pro-environmental motives (AC and AR), normative motives (SNs and PNs), risk motives (CR and DR), and individual characteristics (TIT and IN) in influencing consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs. The specific procedural steps involved in fsQCA are outlined as follows.

Step 1: Data calibration. Data calibration constitutes the initial phase of fsQCA. This process entails the transformation of raw data into fuzzy sets characterized by membership scores ranging from 0 to 1. In this context, membership within fuzzy sets can be distributed continuously across this interval, where a score of 0 signifies complete non-membership and a score of 1 indicates full membership. Scores between these extremes reflect varying degrees of membership, with values approaching 0 denoting partial non-membership and those nearing 1 indicating partial membership. A score of 0.5 represents a maximum fuzzy point, suggesting neither partial membership nor partial non-membership. Given that the data utilized in this study were derived from a seven-point Likert scale, calibration values of 95%, 50%, and 5% were designated for full membership, the crossover point, and non-full membership, respectively. Additionally, the calibration function within the fsQCA3.0 software was employed to calibrate the sample data for both the condition and outcome variables, thereby facilitating the derivation of fuzzy membership values for each construct.

Step 2: Analysis of necessary conditions. Following the data calibration, an analysis of necessary conditions is conducted. This analysis aims to ascertain whether any specific condition is essential for the outcome, implying that the outcome cannot occur in its absence. A consensus score of 0.9, accompanied by adequate coverage, is typically regarded as indicative of necessity. In fsQCA, the evaluation of fit parameters is conducted through two primary metrics: consistency and coverage. Consistency reflects the extent to which causal combinations correlate with the same outcome, thereby indicating the strength of the subset relationship [63]. Conversely, the coverage index quantifies the proportion of variance that is explained. More specifically, original coverage denotes the fraction of the outcome accounted for by the causal combination, while unique coverage delineates the portion of the outcome that is exclusively attributable to the causal combination, excluding contributions from other combinations [64].

Step 3: Analysis of sufficient conditions. The analysis of sufficient conditions within conditional configurations represents a critical step in deriving conclusions. This analysis investigates whether a configuration comprising various antecedent conditions is adequate for the manifestation of the outcome. The analytical procedure is typically executed via a truth table. In conducting the truth table analysis, it is imperative to establish thresholds for case frequency and consistency to streamline the initial truth table. In the fsQCA software, the default setting for the case frequency threshold is 1. However, in practical research scenarios where the number of cases exceeds 100, a higher frequency threshold may be appropriate. Based on the findings of previous research, a consistency threshold of 0.75 was established, leading to the exclusion of cases with consistency values below that threshold. Furthermore, the outcomes of the fsQCA yielded complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions, thereby identifying core and peripheral conditions that contribute to the high adoption of ADAs.

3.2. Measures

The measurement scales for all constructs were derived from the established literature, thereby affirming the initial reliability and validity of these scales. The constructs of awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility were assessed in the studies conducted by [45,59]. The subjective norm was adapted from the work of [61], while the personnel norm scale was modified based on [61]. Trust in technology was measured using the scale developed by [7]. The innovation scale was adapted from both [7,62]. The measurement of delivery risk was informed by the studies of [18,49], and the COVID-19 risk scale was adopted from [17]. Lastly, the behavioral intention scale was derived from the research of [8,62].

All constructs were evaluated using a seven-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and a score of 7 indicated “strongly agree”. To ensure the validity of the questionnaire, five experts in the relevant field and two academics specializing in last-mile delivery were consulted. The questionnaire was initially crafted in English and subsequently translated into Chinese utilizing a back-to-back translation method. Additionally, forty MBA students participated in pre-tests to verify the accuracy and clarity of the scale. Following these evaluations, the factors AC4 and AR4 were excluded due to unsatisfactory results, leading to the development of a refined formal questionnaire.

3.3. Data Collection

For the purpose of this study, data were collected using an online survey platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), which was operated by a reputable survey organization in China. The survey was administered from 15 November to 15 December 2022, with participants incentivized through a bonus for their completion of the survey. Following the elimination of inappropriate responses, a total of 615 responses were obtained, of which 561 were deemed valid, resulting in an effective response rate of 91.22%. To facilitate participants’ understanding of ADVs, a brief introduction that included both textual and graphical elements was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Table 2 delineates the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Among the total sample of participants, 281 individuals identified as male, representing 50.01% of the cohort, while 280 identified as female, accounting for 49.9%. The age distribution indicated that most participants (95%) were aged between 19 and 45 years, with only 2 respondents under the age of 18 (0.36%) and 25 respondents over the age of 46 (4.4%). In terms of educational qualifications, 396 participants (70.59%) held bachelor’s degrees, while 11 individuals (1.96%) had completed high school or lower levels of education, 57 participants (10.16%) had attended junior college, and 97 individuals (17.29%) possessed a master’s degree or higher. Regarding employment status, the largest groups were comprised of employees in private enterprises (24.42%) and students (60.07%), followed by civil servants or public institution employees (10.16%), freelancers (2.5%), and other occupations (1.78%). In terms of personal monthly income, 23.52% of respondents reported earnings below RMB 1000, 36.36% indicated incomes between RMB 1000 and RMB 3000, 15.15% earned between RMB 3001 and RMB 5000, 17.29% reported earnings between RMB 5001 and RMB 10,000, and 7.67% indicated incomes exceeding RMB 10,000.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Assessment of Reliability and Validity

Table 3 indicates that both Cronbach’s α and Composite Reliability (CR) for all causal conditions exceeded the acceptable threshold of 0.7, with values above 0.6 also deemed acceptable. This suggested that the reliability of the scales utilized in our study was satisfactory [65]. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all causal conditions were above the 0.5 threshold, although AC1 was 0.399, which was marginally acceptable. The factor loadings for all constructs were above 0.6, thereby confirming convergent validity. Additionally, as presented in Table 4, the square root of the AVE values along the diagonal was greater than the correlation coefficients with other constructs, which demonstrated robust discriminant validity [65].

Table 3.

Assessment of reliability and validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.2. fsQCA Analysis

From the analysis presented in Table 5, it can be inferred that the maximum consistency value across all conditions was 0.808, which fell short of the 0.9 threshold. This suggested that a singular condition was insufficient to account for the observed outcomes. Consequently, we conducted a further examination of the pathways that integrated the conditional variables and their influence on the outcome variable. To ensure that the configurations of antecedent conditions with sample frequencies meeting or exceeding the established frequency threshold encompassed at least 80% of the samples, we set the sample frequency threshold at 4 and the consistency threshold at 0.8 as default parameters in our analysis. We then performed path normalization analyses to derive complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions.

Table 5.

The necessity tests for conditional variables.

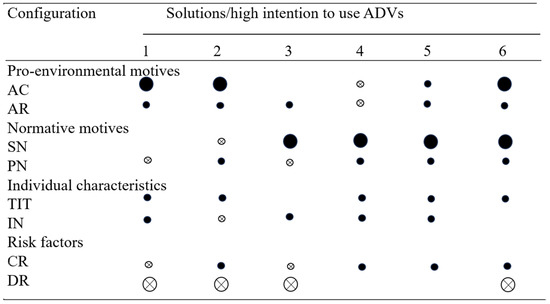

As illustrated in Figure 2, the overall solution consistency for the sample was 0.909, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.8. The overall solution coverage was recorded as 0.511, indicating that the six solutions identified in this study accounted for 51.1% of the total high adoption intention. The findings corroborated the hypothesis posited in our research that various motives could mutually reinforce one another and collectively influence consumers’ intentions to utilize ADVs. In terms of core conditions, both Solution 1 and Solution 2 highlighted that the awareness of consequences and the absence of delivery risk served as fundamental conditions that could foster high adoption intentions. Solution 3 further indicated that the presence of the core condition of subjective norms, along with peripheral conditions such as ascription of responsibility, trust in technology, and consumer innovativeness, could also yield high intentions to use ADVs, even in the absence of the core condition of delivery risk and the peripheral conditions of COVID-19 risk and personal norms. Solution 4 revealed that despite the absence of pro-environmental factors among the peripheral conditions, the presence of subjective norms, personal norms, and COVID-19 risk as core conditions could still result in high adoption intentions. Solution 5, which exhibited the highest raw coverage, suggested that the combined presence of the core condition of subjective norms and peripheral conditions (including pro-environmental motives, consumer characteristics, and risk factors) could lead to elevated intentions. Finally, Solution 6 indicated that the simultaneous presence of core conditions—comprising awareness of consequences, subjective norms, and the absence of delivery risk—alongside peripheral conditions such as ascription of responsibility, personal norms, trust in technology, and COVID-19, also contributed to a high intention to utilize ADVs, irrespective of the presence of consumer innovativeness.

Figure 2.

The fsQCA analysis results. Notes: The black circles (●) and crossed-out circles (⛒) denoted the presence and absence of a condition, respectively. Moreover, the larger circle stands for the core condition, while the small circle refers to the peripheral condition, and the space represents the “do not care” condition.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

This research aimed to elucidate the interplay between various motivational factors—specifically pro-environmental motives (awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility), normative motives (subjective norm and personal norm), risk-related motives (COVID-19 risk and delivery risk), and individual characteristics (trust in technology and innovation)—in fostering a strong intention to utilize ADVs. The findings indicated that no single factor was adequate to elicit the desired outcome, rather, a synergistic combination of these antecedents was necessary to effectively influence consumers’ intentions to adopt ADVs. Our analysis identified six distinct pathways to achieving a heightened intention to use ADVs.

Solution 1 posited that awareness of consequences and low delivery risk served as core conditions, while ascription of responsibility, trust in technology, low personal norms, and COVID-19 risk functioned as edge conditions, collectively facilitating a high adoption rate of ADVs. Solution 2 similarly identified awareness of consequences and low delivery risk as core conditions but incorporated ascription of responsibility, personal norms, trust in technology, COVID-19 risk, low subjective norms, and low innovation as edge conditions to also promote a high adoption behavior. Notably, both solutions shared a commonality in that they suggested environmentally conscious consumers, despite the presence of delivery risks, remained committed to their environmental values, actively engaging in pro-environmental behaviors or opting for eco-friendly products. This supports the findings of earlier researchers, indicating that consumers who are environmentally aware and responsible are likely to seek to honor their environmental obligations by participating in various forms of eco-friendly behaviors or by choosing sustainable products [20,40]. Numerous studies have corroborated the notion that an awareness of the consequences of environmental degradation motivates consumers to adopt pro-environmental behaviors, such as selecting green products or participating in sustainable practices [45,59].

Solution 3 posited that a high adoption behavior could be fostered by establishing subjective norms and low delivery risk as primary conditions, while ascription of responsibility, innovation, low personal norms, and low COVID risk served as secondary conditions. This indicated that consumers were significantly swayed by the opinions of those in their social circles regarding delivery risk, leading to an increased likelihood of adopting ADVs. The existing literature corroborates this notion, suggesting that social influence diminishes consumers’ perceived risks, thereby playing a crucial role in the adoption of ADVs [7,8].

Solution 4 suggested that when subjective norms were treated as the primary condition, and personal norms, trust in technology, innovation, COVID risk, low awareness of consequences, and low ascription of responsibility were considered as secondary conditions, a high adoption behavior could also be achieved. Similarly, Solution 5 indicated that the high adoption of ADVs could occur with subjective norms as the core condition, while awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, personal norms, trust in technology, innovation, and COVID risk functioned as edge conditions. Both solutions emphasized that in addition to social influence as a key determinant of adoption, personal norms, trust in technology, innovation, and COVID risk also significantly impacted consumer adoption decisions. However, it is noteworthy that Solution 5 highlighted the influence of pro-environmental motives on consumer adoption behavior, a factor that Solution 4 did not address.

Solution 6 posited that a high adoption behavior was fostered by core conditions such as awareness of consequences, subjective norms, and low delivery risk, alongside edge conditions including ascription of responsibility, personal norms, trust in technology, and perceived COVID risk. This indicated that in the absence of delivery risk, the interplay between awareness of consequences and subjective norms significantly influenced consumers’ adoption decisions. This finding aligns with the conclusions of other researchers who assert that pro-environmental motives and subjective norms impact consumers’ altruistic behaviors [45,61].

The study’s results revealed that four out of the six proposed solutions underscored the pivotal role of subjective norms, indicating that consumers were susceptible to the influence of peers, friends, or family when determining whether to adopt ADVs. This observation is corroborated by numerous scholars [7,8]. For instance, refs. [7,28] highlighted the substantial impact of social influence on consumer adoption of ADVs. Additionally, three of the six solutions emphasized the significance of awareness of consequences on consumer behavioral intentions, suggesting that certain consumers perceive the adoption of ADVs as an environmentally responsible action. They believe that failing to embrace this emerging technology would hinder their ability to meet their environmental commitments. This conclusion is consistent with the perspectives of various scholars who argue that awareness of consequences influences the ascription of responsibility and personal norms, thereby affecting consumers’ intentions to purchase pro-environmental products [66] or engage in pro-environmental behaviors [61,67]. Furthermore, four of the solutions indicated that the absence of delivery risk served as a core condition that could also foster a high intention to adopt ADVs, which contradicts previous research suggesting that delivery risk diminishes consumers’ willingness to embrace emerging technologies [9]. This may be attributed to advancements in intelligent technology and the increasing sophistication of driverless technology, which lead consumers to be more receptive to innovative solutions and to perceive autonomous delivery technologies as reliable and trustworthy, despite any potential risks.

Moreover, the significance of individual consumer characteristics in the context of IT adoption has been widely acknowledged [7]. The findings of this study revealed that consumer trust in ADV technology remained a critical factor influencing intentions to use ADVs, with the exception of one solution. This is consistent with prior studies that emphasize the role of trust in consumers’ decision-making processes regarding the adoption of emerging technologies [68,69]. Moreover, four out of the six solutions indicated that the level of consumer innovativeness affected intentions to adopt ADVs, a finding that has been corroborated by previous research identifying innovativeness as a key determinant of consumers’ willingness to adopt ADVs [7]. Other scholars have similarly recognized the importance of innovativeness in the consumer decision-making process [54].

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The theoretical contributions of this study are as follows. Firstly, the study offers a better understanding of consumers’ intention to use ADVs by integrating pro-environmental motives (awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility), normative motives (subjective norm and personnel norm), risk motives (COVID-19 risk and delivery risk), and individual characteristics (trust in technology and innovation) into a single model by using the fsQCA method. While prior research has extensively examined the acceptance and adoption of emerging technologies, such as mobile commerce [53], mobile payment [54], e-government [45], and autonomous vehicles [23,70], this study represents a pioneering effort to synthesize the relevant dimensions of the previously mentioned four categories to investigate consumer intentions regarding ADVs.

Secondly, there has been limited research focusing on the acceptance and adoption of ADVs through the fsQCA method, and this study is the first to elucidate the potential mechanisms that influence consumer decisions to utilize ADVs. In recent years, the fsQCA method has garnered increasing attention within the fields of information systems (IS) and information technology (IT) adoption studies [58,71]. The fsQCA method is capable of analyzing various causal combinations and identifying distinct configurations of conditions that impact the desired outcomes, in contrast to previous studies that employed structural equation modeling or regression analysis to explore symmetric relationships among factors [7,8,25,39,61,72]. As illustrated in Figure 2, the complex nature of expected outcomes cannot be attributed to a single factor; rather, it is the result of multiple interacting factors that elucidate the relationship between antecedents and outcomes.

6.2. Practical Implications

Numerous configurations of conditions exist to facilitate the attainment of the desired outcomes, specifically a heightened intention to utilize ADVs. Initially, for consumers who are environmentally conscious, manufacturers and marketing managers of ADVs should prioritize the promotion of the environmental benefits associated with these vehicles, such as energy efficiency and eco-friendliness, alongside their functional advantages, including time savings and operational efficiency. Marketing professionals within logistics and express delivery sectors ought to highlight the low energy consumption and environmental characteristics of ADVs during their promotional activities. This approach is likely to elicit a favorable response from environmentally minded individuals, thereby fostering positive personal norms regarding the adoption of this innovative technology. Additionally, it is imperative to underscore the safety performance of ADVs to potential users. For instance, during the pandemic, ADVs facilitated contactless delivery, significantly alleviating consumers’ perceptions of COVID-19 risk and contributing to the mitigation of the virus’s spread. Furthermore, ADVs employ advanced technologies such as high-definition cameras, lidar, and automated navigation systems to autonomously navigate obstacles, thereby ensuring the safety of both vehicles and pedestrians while minimizing delivery risks in last-mile logistics.

For consumers exhibiting lower levels of environmental awareness, logistics and express delivery companies should endeavor to activate normative influences and foster innovation to bolster trust in ADVs. This could be achieved by encouraging individuals who have previously utilized ADVs to share their experiences, thereby amplifying the dissemination of these narratives through social media platforms. Among the various strategies examined, the subjective norm emerges as a particularly pivotal factor in cultivating a strong intention to adopt ADVs. Consequently, it is essential to organize a range of experiential activities aimed at enhancing consumer trust and mitigating perceived risks associated with this advanced technology.

7. Limitations and the Future Directions

This study presents several theoretical and practical contributions. However, it is not without its limitations. Firstly, the research focused solely on the intention to use ADVs rather than actual usage behavior. While these two constructs are closely related, they exhibit distinct differences. Secondly, the sample population was limited to Chinese consumers, suggesting that future research should aim to assess the generalizability of the findings by including participants from diverse countries or regions. Thirdly, additional individual characteristics, such as the Big Five Personality Traits, as well as technological factors like perceived enjoyment, anthropomorphism, and perceived intelligence, could be incorporated in subsequent studies to further validate the adoption behaviors associated with ADVs. Lastly, the fsQCA method employed in this study has inherent limitations and it primarily examines the influence of the configuration of leading factors on outcomes without providing a ranking of the importance of pre-variables. Furthermore, the fsQCA analysis process demands considerable time and effort for data preparation and calibration. The interpretation of results is also labor-intensive, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of the relationships within the data configurations, which may pose significant challenges for some researchers. Future investigations could benefit from integrating fsQCA with alternative methodologies to enhance the exploration of the consumer adoption of ADVs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, S.W.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, S.W.; resources, L.L.; data curation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, L.L.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the guidelines of Measures of National Health and Wellness Committee on Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving People (Wei Scientific Research Development [2016] No.11).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F.; Wong, Y.D.; Teo, C.C. An innovation diffusion perspective of e-consumers’ initial adoption of self-collection service via automated parcel station. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Ran, L.; Liao, F. Contactless food supply and delivery system in the COVID-19 pandemic: Experience from Raytheon-mountain hospital, China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 3087–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaderi, H.; Tsai, P.W.; Zhang, L.L.; Moayedikia, A. An integrated crowdshipping framework for green last mile delivery. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C. Autonomous Delivery Industry Moving Towards High-Quality Collaborative Development. 2022. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1740303763920223989&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- State Post Bureau. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of the Postal Industry in 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.spb.gov.cn/gjyzj/c100276/202305/d5756a12b51241a9b81dc841ff2122c6.shtml (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- iiMedia Report|China’s Express Logistics Industry Development Status and Typical Case Study Report. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1740283510209891779&wfr=spider&for=pc.2022 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Kapser, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Bernecker, T. Autonomous delivery vehicles to fight the spread of COVID-19—How do men and women differ in their acceptance? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 148, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapser, S.; Abdelrahman, M. Acceptance of autonomous delivery vehicles for last-mile delivery in Germany-Extending UTAUT2 with risk perceptions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 111, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, C.N.; Hudik, M.; Riha, D.; Stros, M.; Ramayah, T. Critical factors characterizing consumers’ intentions to use drones for last-mile delivery: Does delivery risk matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 3, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelias, P.; Elissavet, D.; Vogiatzis, K.; Skabardonis, A.; Zafiropoulou, V. Connected & autonomous vehicles—Environmental impacts—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 712, 135237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Campbell, A.M.; Thomas, B.W. The value of autonomous vehicles for last-mile deliveries in urban environments. Manag. Sci. J. Inst. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VIT. The Report That the Identity and Road Safety of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles. 2022. Available online: https://36kr.com/p/1416518337414022 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- ChinaEV100. The “Autonomous Delivery Joint Innovation Center” Was Officially Established. 2020. Available online: http://www.chebrake.com/news/2020/07/02/21456.html (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Liang, C.Y. China’s First Autonomous Logistics Vehicle “Pioneer” Successfully Tested in the Scene. 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1720289403347448344&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Han, J.Y. Technology and Legal System: Research on the Legal Issues of Autonomous Vehicles. Audit. Vis. 2022, 10, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Wang, N.X.; Yuen, K.F. Can autonomy level and anthropomorphic characteristics affect public acceptance and trust towards shared autonomous vehicles? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Envelope, C.; Envelope, H.; Envelope, E.; Envelope, H. Factors affecting customer intention to use online food delivery services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, W.C.; Tung, S.E.H. The rise of online food delivery culture during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of intention and its associated risk. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Economics. 2021, 8, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Pani, A.; Mishra, S.; Golias, M.; Figliozzi, M. Evaluating Public Acceptance of Autonomous Delivery Robots During COVID-19 Pandemic. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 89, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Bahruddin, M.B.; Ali, M. How trust can drive forward user acceptance of the technology? In-vehicle technology for autonomous vehicle. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, R.; Cugurullo, F. Capturing the behavioral determinants behind the adoption of autonomous vehicles: Conceptual frameworks and measurement models to predict public transport, sharing and ownership trends of self-driving cars. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wong, Y.D.; Ma, F.; Wang, X. The determinants of public acceptance of autonomous vehicles: An innovation diffusion perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klara, L.; Alěs, G. Role played by social factors and privacy concerns in autonomous vehicle adoption. Transp. Policy 2023, 132, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.X.; Yin, J.L.; Huang, Y.L.; Liang, Y. The role of values and ethics in influencing consumers’ intention to use autonomous vehicle hailing services. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, H.B.; Touami, S.; Dablanc, L. Autonomous e-commerce delivery in ordinary and exceptional circumstances. The French case. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100774. [Google Scholar]

- Figliozzi, M.A. Carbon emissions reductions in last mile and grocery deliveries utilizing air and ground autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 85, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKheder, S.; Bash, A.; Al Baghli, Z.; Al Hubaini, R.; Al Kader, A. Customer perception and acceptance of autonomous delivery vehicles in the State of Kuwait during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 191, 122485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.Y.; Yuen, K.F. Consumer adoption of autonomous delivery robots in cities: Implications on urban planning and design policies. Cities 2023, 133, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemardele, C.; Estrada, M.; Pages, L.; Bachofner, M. Potentialities of drones and ground autonomous delivery devices for last-mile logistics. Transp. Res. Part E 2021, 149, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driverless to Help the Deep Fight Against the Epidemic, Yiqing Innovative Unmanned Vehicles Quickly Came to the Aid of Futian Yida Village and Ba Guang Hotel 2022. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1726012185809612850&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Asgari, H.; Gupta, R.; Jin, X. Millennials and automated mobility: Exploring the role of generation and attitudes on AV adoption and willingness-to-pay. Transp. Lett.-Int. J. Transp. Res. 2022, 15, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.W.; Chen, J.T.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wu, Y. How to promote people to use autonomous vehicles? A latent congruence path model. Transp. Lett.-Int. J. Transp. Res. 2023, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Lesch, M.F.; Horrey, W.J.; Strawderman, L. Assessing the utility of TAM, TPB, and UTAUT for advanced driver assistance systems. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 108, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, R.; Louw, T.; Wilbrink, M.; Schieben, A.; Merat, N. What influences the decision to use automated public transport? Using UTAUT to understand public acceptance of Automated Road Transport Systems. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 50, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S. Nuro Driverless Vehicles Approved for Delivery Tests in California. 2020. TheRobotReport. Available online: https://www.therobotreport.com/category/news/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Heimfarth, A.; Ostermeier, M.; Hübner, A. A mixed truck and robot delivery approach for the daily supply of customers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 303, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, J.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Testing VBN theory in Japan: Relationships between values, beliefs, norms, and acceptability and expected effects of a car pricing policy. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 53, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, W.-S.; Liou, G.-B.; Huang, C.-C.; Hsieh, C.-M. Evaluating Determinants of Tourists’ Intentions to Agrotourism in Vietnam using Value- Belief Norm Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkan, K.Y.; Nørbech, T.E.; Nordtømme, M.E. Incentives for promoting battery electric vehicle (BEV) adoption in Norway. Transp. Res. Part D 2016, 43, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ma, Y.; Zuo, Y. Self-driving vehicles: Are people willing to trade risks for environmental benefits? Transp. Res. Part A 2019, 125, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, A.B.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A.; Auld, J.; Stephens, T. A data-driven approach to characterize the impact of connected and autonomous vehicles on traffic flow. Transp. Lett.-Int. J. Transp. Res. 2020, 13, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, A.; Toy, J. Delivery by drone: An evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicle technology in reducing CO2 emissions in the delivery service industry. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 61, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.A.; Gu, Y.A.; Ge, X.A.; Yang, Y.; Cai, H.; Hang, J.; Zhang, J. Exploring the residents’ intention to separate MSV in Beijing and understanding the reasons: An explanation by extended VBN theory. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, Global Edition; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gkargkavouzia, A.; Halkosb, G.; Matsiori, S. Environmental behavior in a private-sphere context: Integrating theories of planned behavior and value belief norm, self-identity and habit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 148, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A.B.; Steg, L.; Granskaya, J. To support or not to support, that is the question”. Testing the VBN theory in predicting support for car use reduction policies in Russia. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 119, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Yu, E.; Jung, J. Drone delivery: Factors affecting the public’s attitude and intention to adopt. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Roy, P.; Arpnikanondt, C.; Thapliyal, H. The effect of trust and its antecedents towards determining users’ behavioral intention with voice-based consumer electronic devices. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. What factors determining customer’ continuingly using food delivery apps during 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic period? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.T.; Li, H.M. Factors influencing mobile services adoption: A brand-equity perspective. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 142–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Piercy, N.C.; Williams, M.D. Modeling Consumers’ Adoption Intentions of Remote Mobile Payments in the United Kingdom: Extending UTAUT with Innovativeness, Risk, and Trust. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebana-Cabanillas, F.; Marinkovic, V.; de Luna, I.R.; Kalinic, Z. Predicting the determinants of mobile payment acceptance: A hybrid SEM-neural network approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawi, N.M.; Hwang, H.J.; Jusoh, A.; Kim, H.K. Examining the Factors That Influence Customers’ Intention to Use Smartwatches in Malaysia Using UTAUT2 Model; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Ali, F.; Bilgihan, A.; Ozturk, A.B. Psychological factors influencing customers’ acceptance of smartphone diet apps when ordering food at restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Yee, D. Unveiling the complexity of consumers’ intention to use service robots: An fsQCA approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 123, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A. The impact of hotel attributes, well-being perception, and attitudes on brand loyalty: Examining the moderating role of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, G.; Sun, P. Determinants and implications of citizens’ environmental complaint in China: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, S.; Wei, J. Consumer’s intention to use self-service parcel delivery service in online retailing: An empirical study. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Anal. 2006, 14, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W. Exploring the influence of severe haze pollution on residents’ intention to purchase energy saving appliances. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, X.; Qu, M. Investigating rural domestic waste sorting intentions based on an integrative framework of planned behavior theory and normative activation models: Evidence from Guanzhong basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, S.; Chau, P.Y.; Cao, Y. Dynamics between the trust transfer process and intention to use mobile payment services: A cross-environment perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M.; Hampton-Sosa, W. The development of initial trust in an online company by new customers. Inform. Manag. 2004, 41, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transp. Res. 2019, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chi, O.H.; Gursoy, D. Antecedents of customers’ acceptance of artificially intelligent robotic device use in hospitality services. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).