Abstract

The fast-paced utilization of innovative Internet of Things (IoT) applications emphasizes the critical role that routing protocols play in designing an efficient communication system between network nodes. In this context, the lack of adaptive routing mechanisms in the standard Routing Protocol for Low-power and Lossy Networks (RPL), such as load balancing and congestion mechanisms, especially under heavy load scenarios, causes significant degradation of network performance. In this regard, integrating innovative and effective learning abilities, such as Reinforcement Learning, into an efficient routing policy has demonstrated promising solutions for future networks. Hence, this paper introduces Aris-RPL, an adaptive routing policy for the RPL protocol. Aris-RPL utilizes a multi-objective Q-learning algorithm to learn optimal paths. Each node translates neighboring node information into a Q-value representing a composite multi-objective metric, including Buffer Utilization, Energy Level, Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), Overflow Ratio, and Child Count. Furthermore, Aris-RPL operates effectively during the exploitation and exploration phases and continuously monitors the network overflow ratio during exploitation to respond to sudden changes and maintain performance. The extensive Contiki OS 3.0/COOJA simulator experiments have verified Aris-RPL efficiency. It enhanced Control Overhead, Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), End-to-End Delay (E2E Delay), and Energy Consumption results compared to other counterparts for all scenarios on average by 39%, 25%, 7%, and 38%, respectively.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT), as a rapidly expanding communication ecosystem, has found widespread applications in many domains: industrial automation [1], sustainable cities [2], healthcare monitoring [3], digital transformation, etc. Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) are the cornerstone element in the IoT paradigm by playing the crucial role of sensing, gathering, and sending data for analysis using Internet-based technologies.

A WSN consists of numerous embedded devices known as sensor nodes that are limited in energy, storage resources, and computing capabilities. Moreover, the nature of these networks, characterized by frequent changes regarding node conditions (energy consumption, buffer utilization, etc.), network congestion, and link quality and traffic demands, makes establishing a communication system challenging. Among various communication mechanisms, routing protocols are crucial and necessary, given the expansion of IoT applications [4] and the network dynamics [5]. As a result, enhancing routing in modern IoT networks is vital and needs to become a multi-objective optimization problem, including packet delivery ratio (PDR), power usage, and control overhead ratio [6]. However, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the international organization for developing Internet standards, including the core protocols that comprise the TCP/IP Internet protocol suite, has proposed a low-power and lossy network routing protocol called RPL to provide a routing solution for resource-constrained IoT nodes [7].

While the standard RPL performs adequately under low-traffic conditions, it experiences a significant deterioration in performance regarding reliability, load balancing, and energy consumption in denser network environments [8]. Specifically, neither the standard RPL nor the inefficient proposed approaches could address issues related to load balancing and energy consumption [9]. Additionally, the diversity of IoT applications, from simple temperature measurements to more complex media data transfer, makes the traffic patterns varied, leading to congestion, packet loss, and eventually node failure [10]. As a result, optimizing RPL performance in such scenarios has gained significant research interest. This led to the development of various rule-based (fixed-based) routing policies to design more effective approaches for RPL networks [11]. Many approaches have been proposed to introduce enhanced solutions for RPL, considering quality of service (QoS) standards and the physical constraints of wireless sensor networks (WSNs) [12,13]. While rule-based solutions may perform well in specific conditions, several factors limit their effectiveness in network scenarios that are more complex, such as varied traffic patterns or unbalanced loads.

Therefore, enabling sustainable intelligent communication in a resource-constrained environment is one of the network design’s essential concerns [9]. Therefore, applying learning methods to RPL as a part of an efficient communication mechanism is critical to powerful intelligent IoT applications. In this context, Reinforcement Learning demonstrated promising solutions for networking in general and routing in particular [14]. For instance, wireless networking uses Reinforcement Learning to optimize networking functions by adapting to environmental changes and making intelligent long-term decisions [15]. Recently, Reinforcement Learning has been employed to enhance the RPL routing policy to address sequential and uncertain decision-making challenges [16]. Among Reinforcement Learning techniques, the Q-learning algorithm has confirmed its applicability for packet forwarding processes [17].

Consequently, this study introduces an optimization approach for RPL called Aris-RPL, providing intelligent routing decision-making for future resource-limited IoT networks. Specifically, unlike traditional approaches that face challenges to adapt to network changes adequately or existing RL-based protocols that often lack addressing load balancing explicitly or have higher overhead in larger networks, Aris-RPL distinguishes itself by introducing a novel hybrid three-phase framework with well-selected routing metrics. That is, Aris-RPL transitions to an exploitation phase probabilistically, suppresses DIO control packets to conserve energy, and during this suppression introduces a dedicated topology monitoring phase that continuously observes the Overflow Ratio. This allows the network to reactively trigger updates only when immediate congestion is detected. To achieve this, Aris-RPL leverages the dynamic decision-making capabilities of the Q-learning algorithm. Overall, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Introducing a Q-learning-based approach with a novel three-phase adaptive routing framework, including exploration, exploitation, and monitoring to effectively improve RPL data forwarding performance.

- Utilizing well-selected routing metrics, including Buffer Utilization, Energy Level, Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), Overflow Ratio, and Child Count, to provide nodes with the ability to observe the neighborhood.

- Applying a hybrid topology monitoring mechanism that suppresses DIOs during stability and monitors overflow ratio to reactively trigger updates, balancing overhead and responsiveness.

2. Preliminaries

This section highlights the fundamental concepts of the RPL routing protocol, machine learning in general, and the Q-learning algorithm in particular.

2.1. RPL Protocol Overview

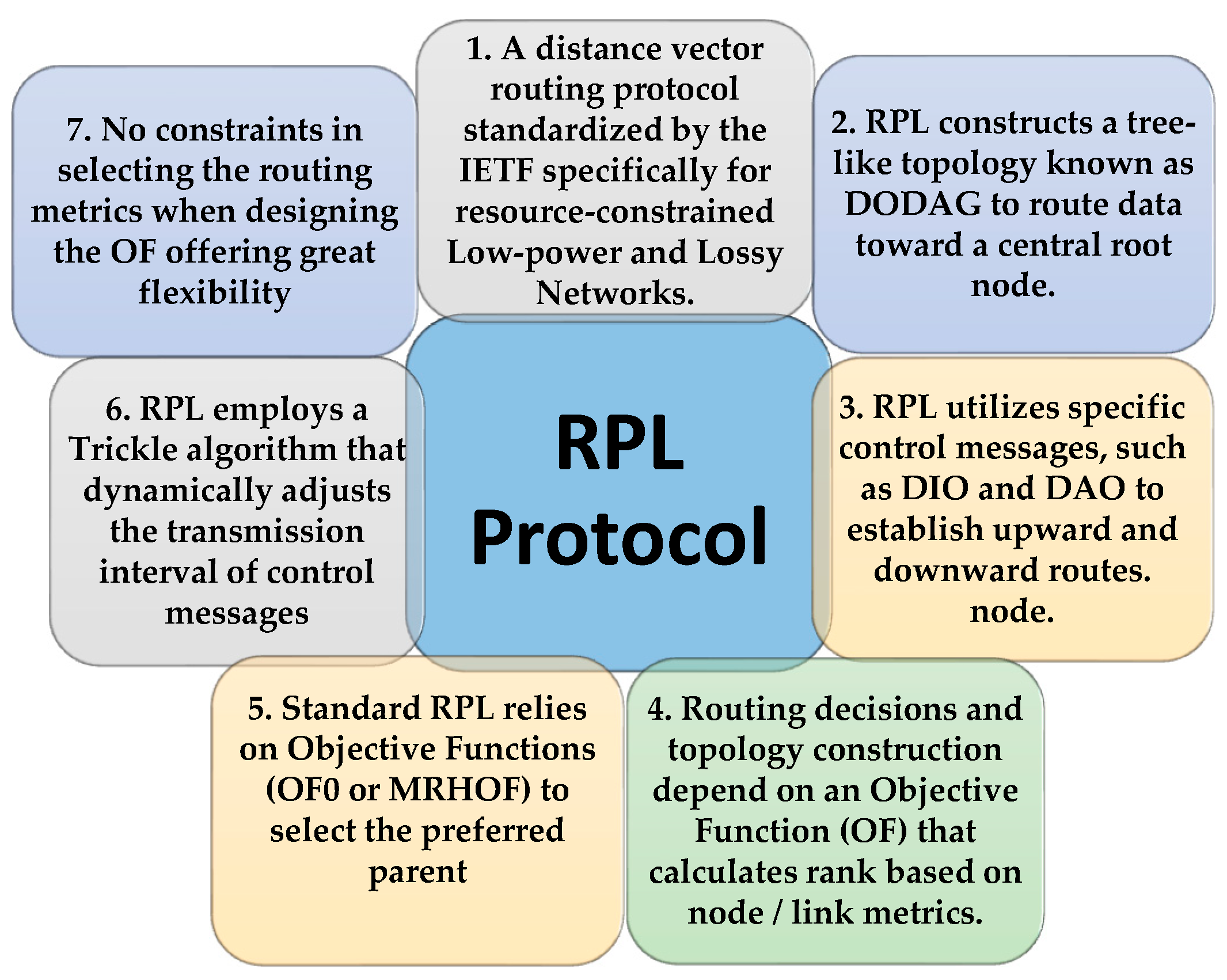

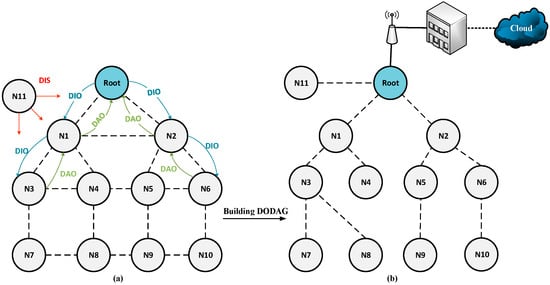

IETF introduced RPL to standardize routing in the resource-restricted Low-power and Lossy Networks. RPL is a distance vector routing protocol. It works on top of IEEE 802.15.4 PHY and MAC layers in collection-based environments, allowing network nodes to regularly transmit environmental data to a central collection point [18]. RPL builds the tree-like Destination-Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph (DODAG). It is a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) with a singular node called the border router or the root node that provides a gateway to the Internet. The nodes have to specify routes inside DODAD to deliver data to the root in a one-hop or multi-hop manner.

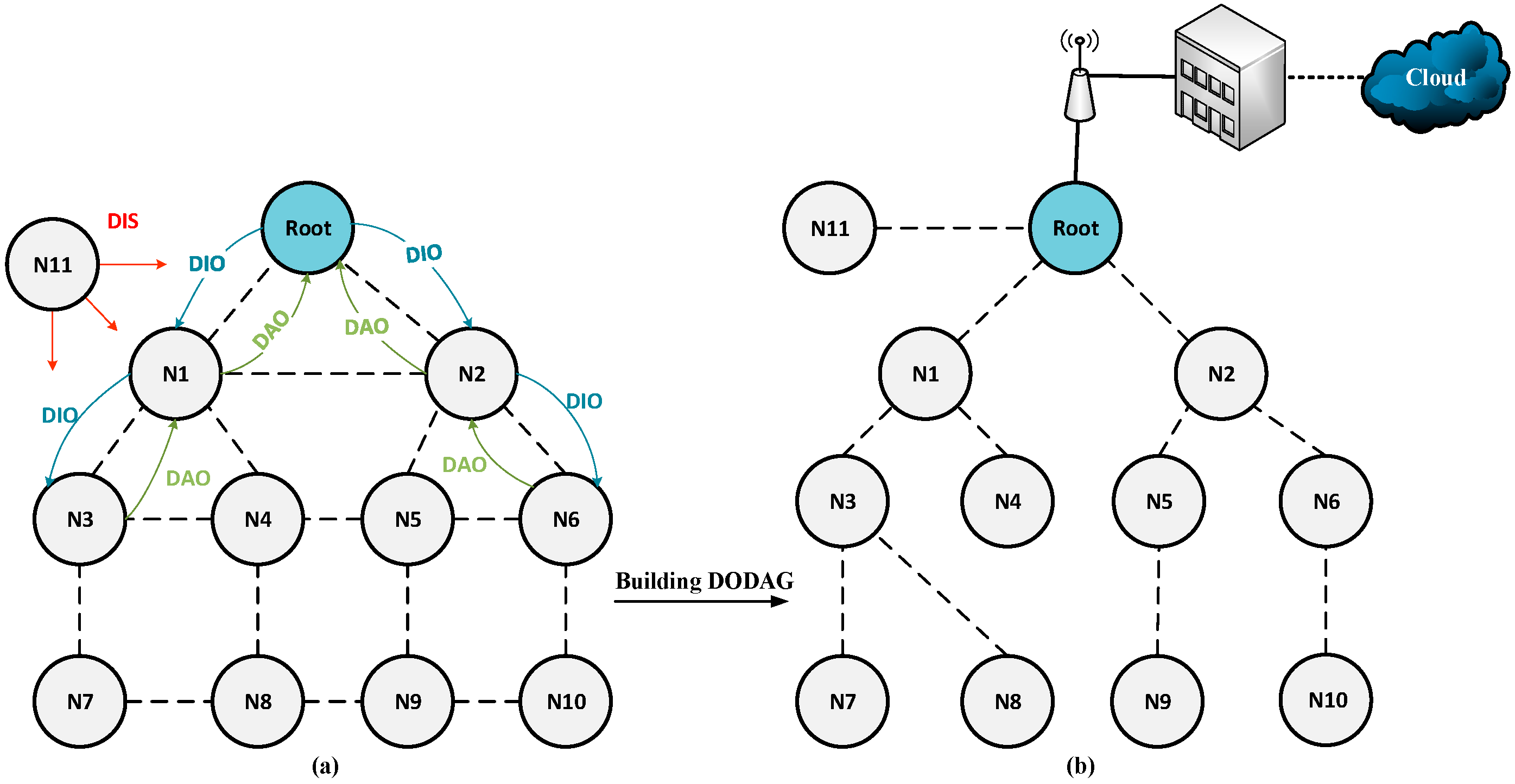

According to Figure 1, RPL uses the control messages to build DODAG, including DODAG Information Object (DIO), DODAG Information Solicitation (DIS), Destination Advertisement Object (DAO), and DAO Acknowledgment (DAO-ACK) [18]. DIO is responsible for transmitting network information between IoT nodes. Network nodes utilize DIO and DIS messages to establish upward traffic routes, while DAO and DAO-Ack messages are used to support downward traffic routes.

Figure 1.

Network Graph: (a) Before Using RPL; (b) After Using RPL.

The DODAG topology highly depends on the RPL objective function (OF). It is responsible for rank calculation based on routing metrics such as link quality, delay, and energy consumption, besides defining routing optimization objectives and constraints. In fact, OF controls the metrics’ conversion criteria into ranks to select and optimize routes within a DODAG [19]. Two standardized objective functions exist in the original version of RPL. Objective Function Zero (OF0) [20] and Minimum Rank with Hysteresis Objective Function (MRHOF) [21]. Depending on the employed node/link metric(s) carried in the metric container of the DODAG information object (DIO) and the objective function, every node running RPL selects its next forwarder (preferred parent).

To regulate the rate at which nodes generate control messages (especially DIOs), RPL uses a trickle algorithm, which adjusts the dissemination rate of these messages following the stability of the topology [22]. According to this timing mechanism, nodes transmit fewer control messages if the network is stable. The transmission interval is doubled each time stability is maintained, up to a maximum period. However, if instability conditions occur (e.g., link failure), the timer resets to the least value to promptly disseminate DODAG information updates. Figure 2 provides an overview of the RPL protocol.

Figure 2.

RPL Description Summary.

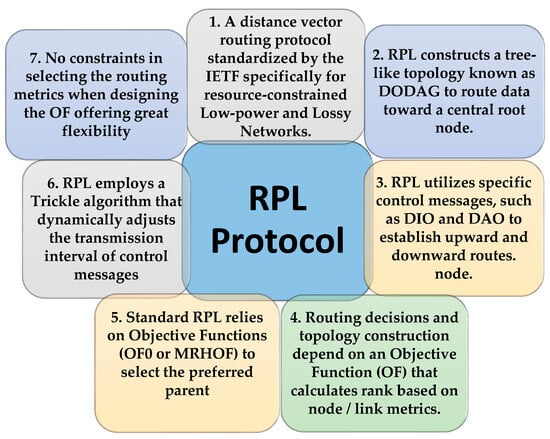

2.2. Reinforcement Learning Overview

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence science that includes methods to detect patterns and relations in data sets and provide a prediction model to predict future data [23]. Reinforcement Learning is a machine learning technique that mimics human behavior based on trial and error and learning from interactions with the environment without requiring prior knowledge [24].

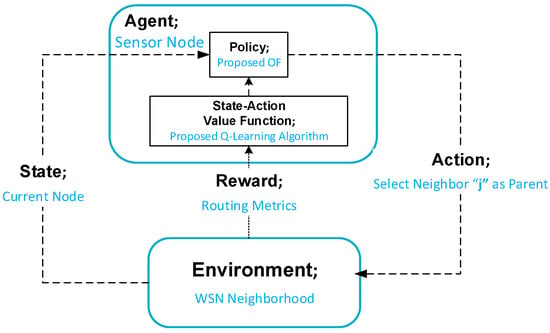

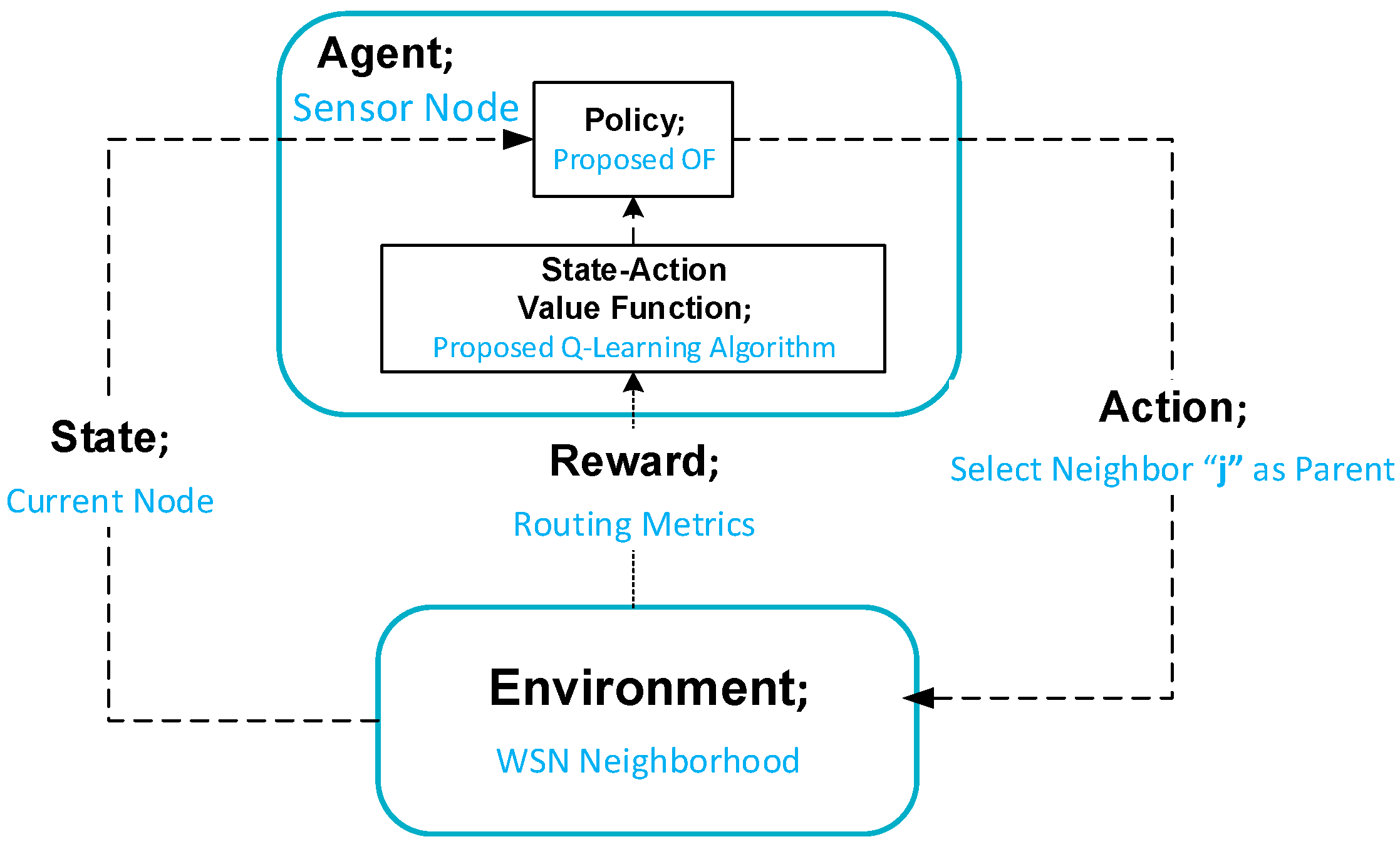

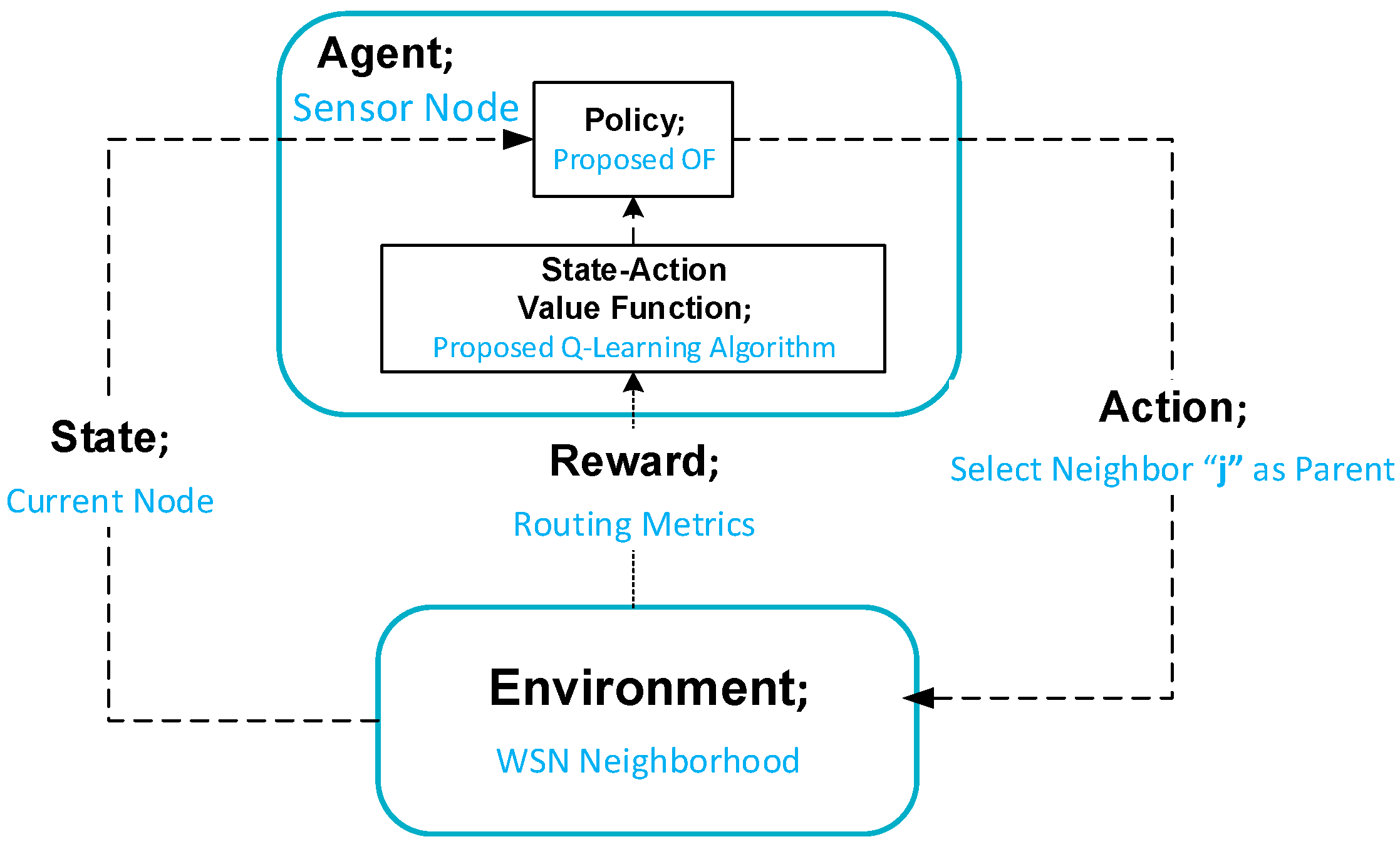

Figure 3 depicts the principle of a Reinforcement Learning operation [25] where the agent at time step t is in some state, observes the environment, takes action, and receives a reward. Then, it moves to a new state. In the case of the routing process of sensor networks, the sensor node represents an agent that acquires knowledge about the unknown environment to make decisions. Q-learning is a widely recognized off-policy reinforcement learning algorithm. Q-learning depends on the Q-table, which stores Q-values representing the expected benefit of taking a specific action in a particular state.

These Q-values are estimated and updated according to the state-action value function in Equation (1) [14].

where is the previous value of Q-value, is the learning factor, and is the reward for selecting an action in state . State indicates the next state, and is the discount factor.

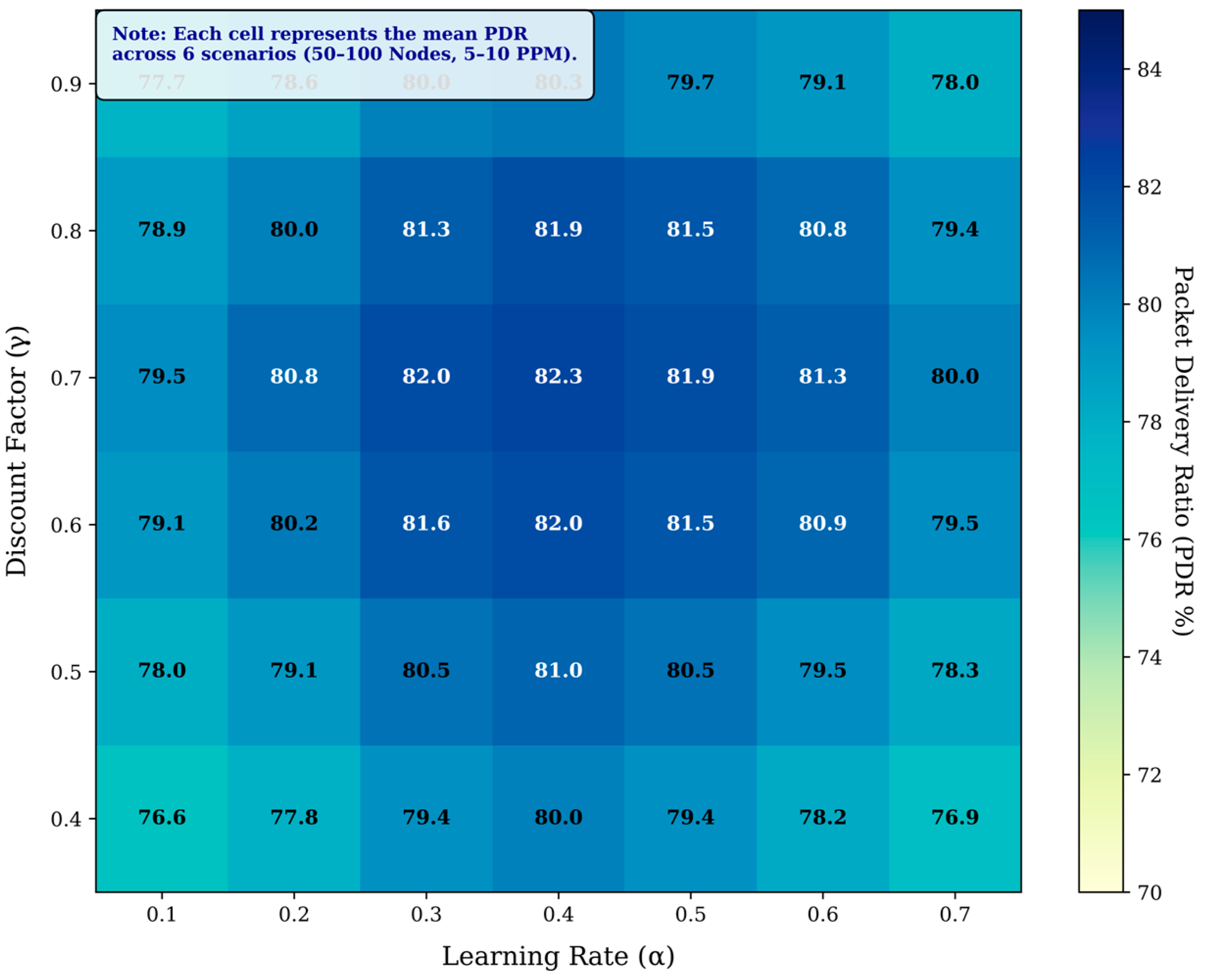

One of the fundamental aspects of Reinforcement Learning is understanding the algorithm’s hyperparameters and the exploitation-exploration trade-off. However, the discount factor and the learning rate in Equation (1) are essential in optimizing the learning process. The learning rate controls the influence of new information on existing knowledge. On the other hand, represents the discount factor (0 ≤ ≤ 1). It determines how much future rewards are valued [26].

In addition, the exploitation-exploration trade-off is an essential consideration in Reinforcement Learning. The agent must balance exploiting cumulative experience to make the best decisions based on available data and exploring new actions to acquire additional data. More exploration can lead to negative rewards, while too much exploitation can result in suboptimal long-term rewards by falling into local optima [14]. Various algorithms, such as the epsilon-greedy and SoftMax techniques, effectively manage this exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Figure 3.

Reinforcement Learning Basic Principle.

Figure 3.

Reinforcement Learning Basic Principle.

3. Related Work

Much research has been conducted by the scientific community to address the inherent limitations of the standard RPL protocol in dynamic IoT environments. Based on the literature review, these approaches can be categorized into three main methodologies: rule-based optimization, fuzzy logic-based optimization, and reinforcement learning-based optimization.

In the context of rule-based approaches, several studies have focused on designing advanced objective functions (OFs) to enhance routing performance in RPL-based networks. For instance, authors in [27] proposed the Queue Utilization-based RPL (QU-RPL). It used the Queue Utilization (QU) routing metric to indicate a node’s congestion level. Furthermore, QU-RPL integrates QU with Hop Count (HC) and Expected Transmission Count (ETX) to design an objective function to reduce congestion and balance the load across the network. However, not considering other metrics like energy consumption restricted its applicability to dynamic network changes. Similarly, reference [28] introduces a new metric named CER to develop the objective function, taking into account various routing metrics such as ETX, Queue Utilization (QU), node lifetime, latency, packet latency, and bottleneck node number routing, but it was limited by not handling dynamics in larger networks. The authors in [29] introduced an objective function named Brad-OF, which incorporates a group of routing metrics, including ETX, remaining energy, and delay. Additionally, the research efforts here introduced a traffic intensity metric to evaluate node buffer congestion, aiming at congestion detection and avoidance, but did not adequately address scalability in large networks. Authors in [30] proposed a method named L2RMR to improve QoS and balance the graph and load. The proposed objective function evaluated a composite metric based on the parent conditions, number of children, and parent rank. Nodes then selected parents with the support of congestion control and load balancing, yet it could not handle network dynamics effectively. The elaborated cross-layer objective function to achieve energy efficiency (ELITE) [31] aims to enhance energy efficiency to co-optimize the MAC and the RPL network layers, but its performance was constrained under high traffic loads with high end-to-end delay. The WRF-RPL protocol [32] was introduced as an enhancement to RPL, specifically targeting performance improvements in congested scenarios. WRF-RPLs objective function evaluated node conditions based on metrics carried by DIO messages. These metrics are congestion rates, hop count, and remaining energy. Then, it determined node priorities and eventually selected the preferred nodes. However, it lacked metrics for link quality. The L-RPL protocol [33] was proposed to enhance communication and routing quality within RPL-based networks. The main mechanism of the L-RPLs objective function is to consider ETX and link estimation in path selection. L-RPL enhanced packet delivery ratio and energy management. However, it did not incorporate congestion-related metrics and experienced high overhead. ELBRP [34] modified the standard RPLs objective function to improve the quality of service, load-balancing, and power usage between nodes. ELBRP made routing decisions based on data traffic distribution. It prioritizes routing quality under low traffic conditions and uses multi-metric parent selections to maintain load balance under heavy traffic. However, it suffered from challenges regarding high overhead and handling dynamic node conditions.

Fuzzy logic methods have been applied to balance different metrics in RPL routing. A notable method named the Fuzzy Logic-based objective function (OF-FL) [35] incorporated link quality, E2E delay, Hop Count (HC), link quality, and energy consumption to design an effective objective function using fuzzy rules. However, its reliance on predefined rules limited its adaptability to changing network conditions. The authors in [36] proposed an opportunistic fuzzy logic-based objective function named OPP-FL. Here, authors measured parent load based on its child count and optimized reliability by integrating the neighbor load metric, the ETX, and the Hop Count (HC) with fuzzy logic, but it struggled with scalability in dense network environments and handling network dynamics.

With the emergence of machine learning techniques, recent literature in the field of LLNs has shifted from traditional rule-based routing frameworks toward more adaptive and intelligent frameworks. In this regard, there is a growing interest in applying reinforcement learning (RL) methods to enhance network performance in wireless environments [37,38,39]. For example, authors in [40] proposed an objective function that employs the learning automata algorithm, which is an RL method, to evaluate the quality of candidate parents based on metrics such as ETX and packet loss ratio. However, it did not address load balancing explicitly. Authors in [9] applied a multi-armed bandit algorithm, which is an RL method, in low-power and lossy IoT devices. The authors claimed that the multi-armed bandit (MAB) algorithm is more suitable than the Q-learning algorithm. The study proposed a network metric, EEX, that represents a new definition of the ETX metric regarding energy, for constructing a DODAG to enhance the network performance. Network scenarios with variable traffic rates were designed to evaluate the approach. Simulation results show that the RPL improves PDR and the control overhead ratio. The Q-Learning-based intelligent Collision Probability Learning Algorithm (iCPLA) [26] used a cross-layer optimization approach by allowing the RPL protocol in the network layer to access information from other layers, such as MAC contention metrics (collision probability), to enhance the RPL process. However, it experienced increased computational complexity as the network grew. Moreover, the work presented in [41] introduced a Reinforcement Learning-based routing approach with a modified Trickle timer strategy designed to enhance RPL network performance by alleviating congestion. This approach used the Q-Learning algorithm to build the Q-table using a value function incorporating metrics such as buffer utilization, Hop Count (HC), and ETX to update Q-values. Simulation results demonstrated improved packet delivery, control overhead, and average delay. However, the approach primarily focused on congestion control without integrating a broader range of network conditions, like energy consumption. The study presented in [42] introduced RI-RPL, a multi-stage and Q-learning-based extension of the RPL protocol aimed at enhancing adaptivity to network conditions and improving RPL performance. The Q-Learning algorithm built the Q-table using a reward function incorporating Transmission Success Probability, Residual energy, buffer utilization, Hop Count (HC), and ETX metrics. Simulation results demonstrated improved PDR, end-to-end delay, energy consumption, and network throughput. However, RI-RPL showed high overhead in dense network scenarios and did not consider load-balancing situations.

Besides the previous reinforcement learning, an emerging research direction has started applying advanced Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) techniques to address complex IoT routing challenges and showing potential future solutions to improve Aris-RPL to better handle network dynamics and cooperation between network nodes. For instance, the work in [43] proposed a hybrid architecture combining DRL with Graph Neural Networks (GNN) to better adapt to dynamic network topologies and enhance DRL decision-making. This work can be used in edge- or cloud-based scenarios because of the high computational cost. Most recently, Authors in [44] presented a Federated Double Deep Q-Learning (DDQN) approach, enabling sensors to collaboratively train routing models for latency and energy optimization without sharing raw data and with increased synchronization overhead. Recent works such as [45] demonstrate the efficacy of reinforcement learning in handling distributed resource management challenges found in WSNs. The authors proposed a distributed deep reinforcement learning framework that models the interaction between Wireless Devices and Roadside Units in Cooperative Intelligent Transportation Systems (C-ITS) as a Stackelberg game to address limited battery energy and computing power, validating their approach through numerical simulations. However, their work focused on resource allocation and offloading layers rather than the network layer of LLNs. Additionally, the research work in [46] proposed a distributed routing algorithm for multi-hop LoRa networks based on Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) learning. The approach achieved a reduction in energy consumption and an improvement in PDR. While effective in its domain, it mainly focused on message-based LoRa communication, which fundamentally differs from the IEEE 802.15.4 standard framework utilized by Aris-RPL. Moreover, the researchers in [47] proposed a Multi-Armed Bandit Bayesian-based algorithm for WSN environmental. The protocol achieved throughput, scalability, and control overhead enhancements.. However, it relied on a centralized SDN-based controller for managing routing tables and calculating rewards, which contrasts with the fully distributed architecture utilized by our proposed solution.

Building upon these existing approaches, our proposed Aris-RPL integrates multiple key metrics into a Q-Learning framework, offering a more efficient solution in dynamic and larger IoT networks. Specifically, Aris-RPL uses a novel composite metric that uniquely combines a proactive congestion metric (buffer utilization) with a reactive one (overflow ratio), effectively and explicitly managing load balancing (child count). This combination is not found, for example, in references [41,42]. Second, and most critically, it introduces a unique three-phase framework (explore, exploit, monitor). In this regard, our method during the monitoring phase actively suppresses DIO control packets during exploitation to reduce overhead, while simultaneously monitoring the overflow ratio (OFR) to trigger updates only when congestion is detected reactively. This hybrid strategy for balancing overhead and responsiveness is the primary novelty of our work. Table 1 provides a comparative summary of these related works, highlighting their methodologies, metrics, contributions, and limitations.

Table 1.

Summary of Related Works.

4. Methodology of the Proposed Routing Mechanism

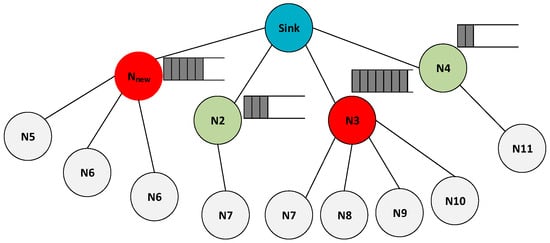

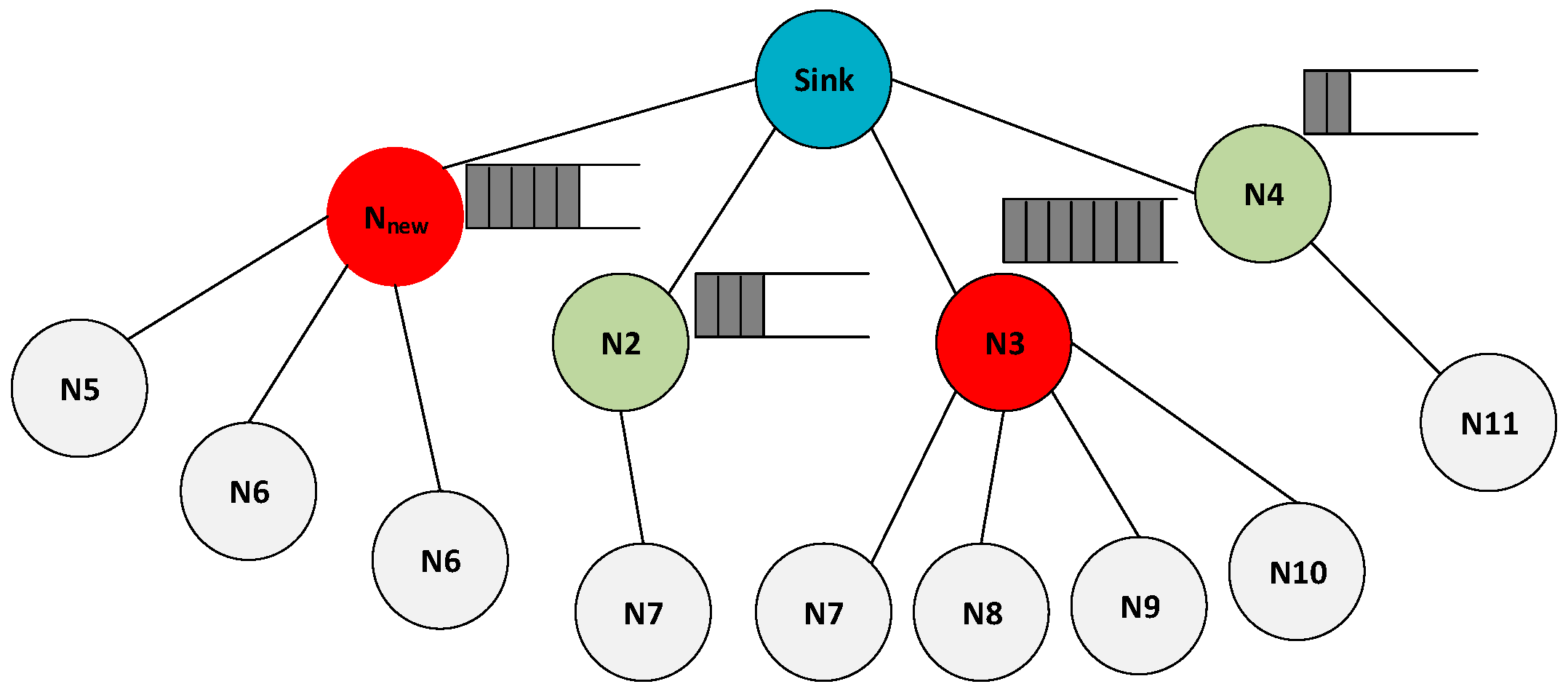

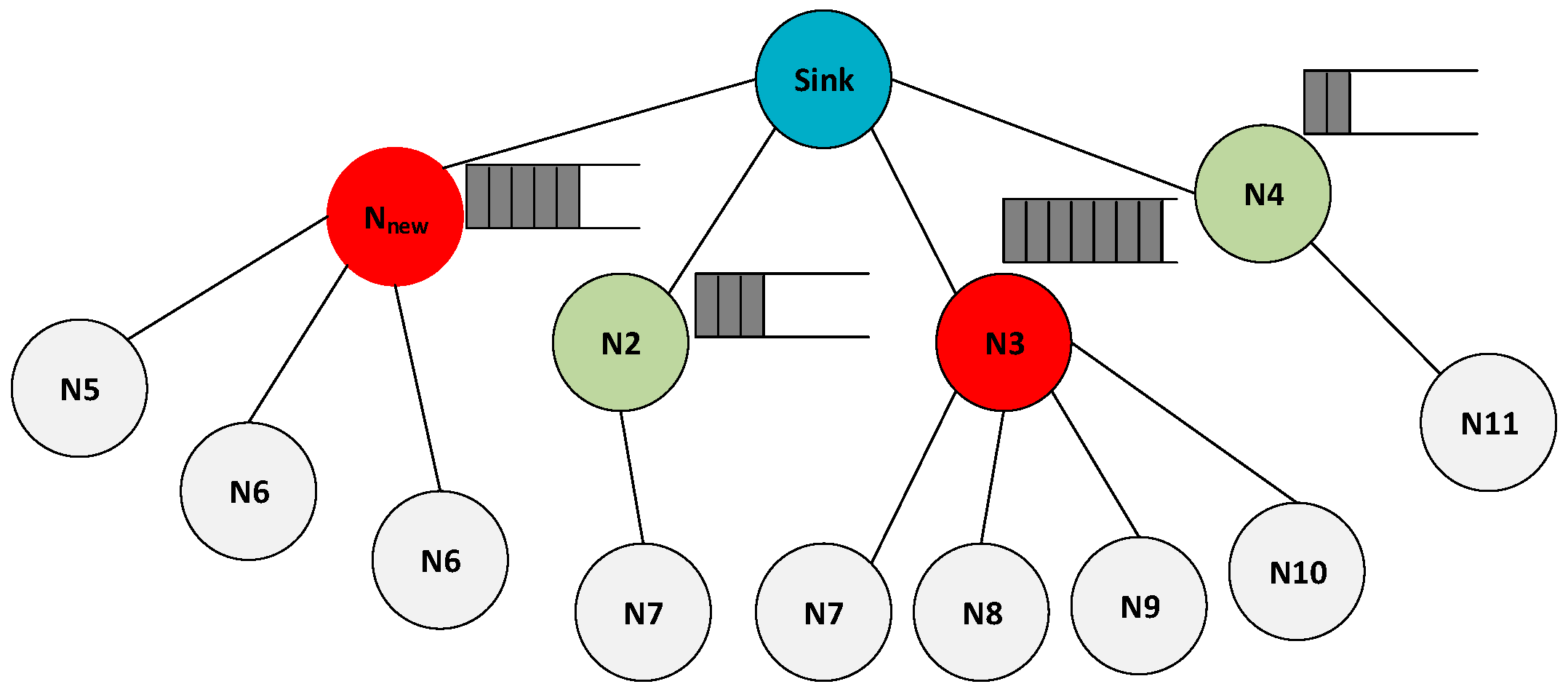

Relying on a single routing metric or inappropriate composite metrics in designing routing criteria for IoT wireless sensor networks is insufficient. As shown in Figure 4, when multiple sensor nodes transmit packets to a single intermediate node (N3), the incoming packet rate increases, and due to the MAC layer contention, processing time, and resource limitations, this leads to overflow and packet loss. The problem is worsened by varying traffic patterns. Even if the incoming and outgoing node traffic rates are equal, the limited buffer size of WSN nodes, typically 4 to 10 packets [41], significantly impacts the packet loss rate. In addition, when a parent node has multiple child nodes, it can become overloaded and more prone to failure [10].

Therefore, these factors tremendously affect the overall packet delivery ratio, especially in dense networks. As a result, the protocol design must take into consideration routing metrics that reflect the actual load condition between nodes as a decision metric to solve the load-balancing problem in uneven traffic load patterns. The original RPL versions (OF0 and MRHOF) do not consider these aspects. In that case, parent switches occur frequently. According to RFC 6550 [18,48], a parent switch is regarded as an inconsistency (or instability) in the network. This is why the RPL resets the trickle algorithm timer to transmit the control packets frequently in the DODAG and recover stability. Authors in [49] showed how selecting an unsuitable next-hop forwarder affects the frequency of parent switches in the network. The study concluded that a higher frequency of inappropriate parent selection leads to more frequent parent switches. Consequently, this increases the energy usage and control overhead in the nodes. Reinforcement learning techniques can better adjust RPL in such conditions by considering effective load-balancing and congestion-aware routing metrics to integrate a self-learning and self-adaptive routing model into the RPL routing protocol.

Figure 4.

Example of Load Balancing Problem in Sensor Networks.

Figure 4.

Example of Load Balancing Problem in Sensor Networks.

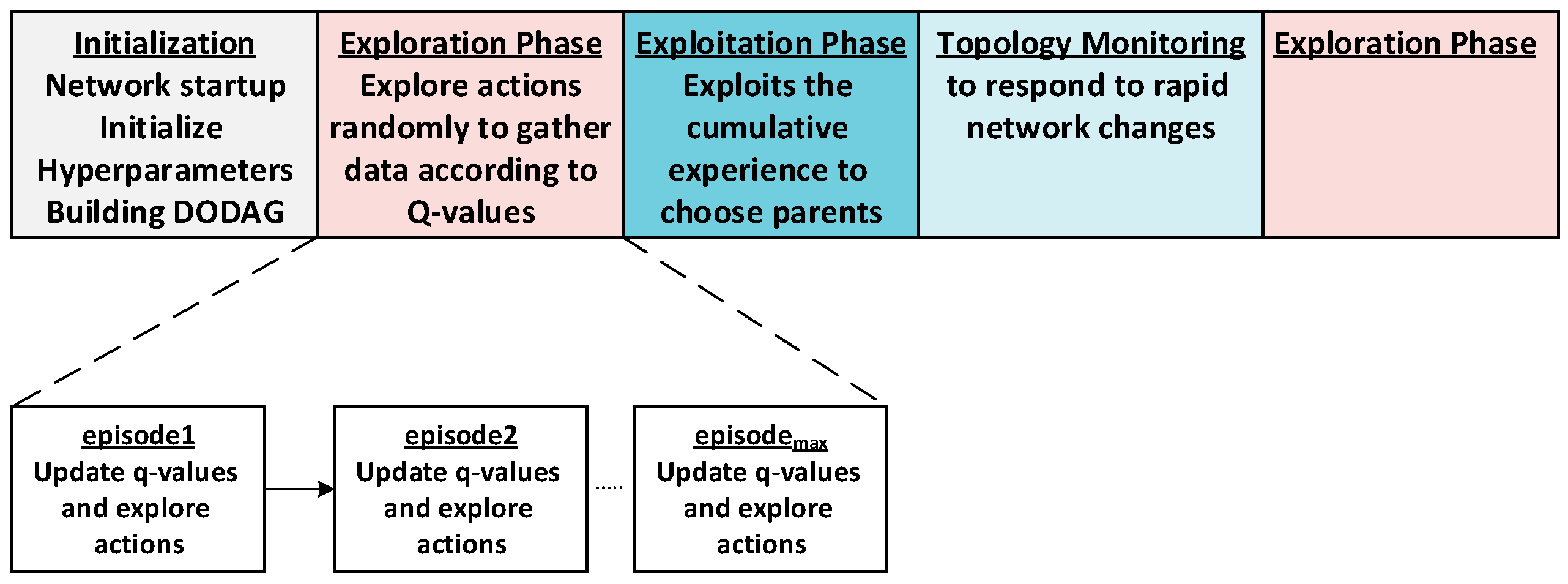

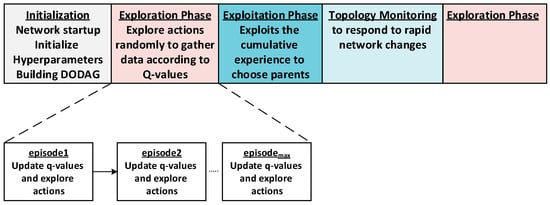

Accordingly, this paper introduces a load-balanced, energy-efficient, and congestion-aware routing mechanism called Aris-RPL for RPL-based IoT networks, leveraging Q-learning to enhance routing. The proposed approach operates in three main phases: (1) After network initialization, the exploration phase explores potential actions for network status. (2) The exploitation phase exploits the cumulative experience to make optimal routing decisions. (3) The network topology monitoring and management phase monitors network topology to respond to rapid network changes, ensuring performance and stability. Figure 5 shows the sequence of the approach’s three phases. The following sections will present further details.

Figure 5.

Proposed General Execution Sequence.

4.1. System Model and Assumptions

Aris-RPL models the routing optimization problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which provides a general framework for defining states, actions, and rewards. The MDP is characterized by the tuple (E, S, A, R), and its solution in this study is approached using the Q-Learning algorithm by finding the optimal routing policy. Here is a detailed description of the MDP components and how they integrate with the Q-Learning algorithm:

- State Space : is a set of finite states in the Environment that represents the WSN network. Every node is defined as a current state in which the agent takes an action. Here, Q-Learning uses the current state to identify potential actions and evaluate their expected rewards. The next node becomes the new state. The state space is defined as .

- Action Space : when the agent resides in the state , it observes the environment, takes an action , and then the current state moves to the next state . An agent (the node) selects one of its neighbors as the next forwarder. Therefore, the current node’s neighbor set represents the action set as where represents the node’s neighbor number. Q-Learning leverages this action space to update Q-values for each possible action in the current state and refine its decision-making process.

- Reward is calculated by the agent upon receiving a signal from a state in the environment based on the employed node/link metrics. According to (1), the Q-learning agent will learn all available actions in each state and update the required Q-values using the reward signals. Finally, it can choose the best action with the maximum cumulative reward. More details about the reward will be in the reward function section.

It is worth noting that Aris-RPL employs Q-learning, which is a model-free reinforcement learning algorithm, meaning that there is no need for an explicit, predefined model of the environment’s state transition probabilities or reward distribution. More specifically, the agent learns the optimal policy directly by iteratively interacting with and sampling the complex and dynamic WSN environment, updating its Q-values based on observed rewards.

The proposed design considers the following assumptions in network design:

- Distributed Network: The network is decentralized, without any central controller.

- Adherence to RPL Standards: Aris-RPL follows the RPL standards. All nodes (excluding the root node) are homogeneous regarding resource constraints such as power and radio range specifications.

- Symmetrical and Bidirectional Interactions: Communication between nodes is bidirectional and symmetrical. Network connectivity is dynamic according to network and node condition changes.

- Single/Multi-Hop Communication: The sink receives data packets from network nodes via single or multi-hop paths, depending on the nodes’ position.

4.2. Routing Metrics Used in Aris-RPL

Aris-RPL uses five routing metrics reflecting the status of the links and neighbors in the network. These metrics are Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), Buffer Utilization, Overflow Ratio, Child Count, and Reminder Energy.

4.2.1. Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI)

The first metric is RSSI. This metric determines the strength of the received signal on the receiving side. Wireless signal measurements, such as indoor localization systems, use this metric widely. However, RSSI appears as an excellent candidate to ensure high Packet Reception Rate (PRR) results due to the high dependency between RSSI and PRR [50,51]. RSSI values are typically measured in -dBm, where a more negative value indicates a weaker signal. The node reception unit repeatedly calculates the neighbor’s RSSI value.

4.2.2. Buffer Utilization (BU)

It measures how much of the buffer’s capacity is currently being used. This metric helps monitor the buffer status and predict potential congestion. Therefore, it helps to make adjustments to prevent overflow as much as possible. The following equation calculates the free space of the node’s buffer:

where is the number of packets currently in node i’s buffer, is the total buffer size of node i. As a result, the buffer utilization typically ranges from 0 (entirely free capacity) to 1 (occupied capacity).

4.2.3. Overflow Ratio (OFR)

In our proposed approach, the overflow ratio (OFR) [16] assesses the congestion status of a node’s buffer by measuring the ratio of lost packets to the total number of packets handled by the node under heavy traffic. It represents a reactive measure to mitigate network congestion by identifying nodes that are dropping packets already and adjusting the load accordingly. To effectively calculate the OFR metric and capture the dynamic nature of network congestion, we need to measure it within specific time intervals. This interval will be set to the initial assignment of the trickle algorithm’s transmission interval t. To provide a balanced view of the node’s OFR, it is smoothed by the exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) filter as follows:

where , , and represent the number of nodes i’s overflowed packets (lost), the number of child packets received by node i, and the number of nodes i’s generated packets, respectively. The parameter σ represents the smoothing factor, where σ ∈ [0, 1], and its value is 0.7. Using OFR and BU metrics together for managing congestion and load-balancing situations offers a beneficial approach. When used integrally, they enable an effective assessment of the network’s congestion state, enabling proactive and reactive measures. This perspective ensures more effective load balancing and congestion management.

4.2.4. Reminder Energy (RE)

It expresses the nodes’ reminder energy and is calculated as follows:

Here and represent the residual energy and the initial energy of node i, respectively.

4.2.5. Child Count

Here, the child count metric contributes to the parent selection process. It is a constraint metric utilized with other conditions to calculate the final reward used to find the related Q-value of the neighbors. The value of this metric is assigned empirically and depends on the type of application (more details in the reward function section).

4.3. The Q-Learning Algorithm

The Q-table is organized into rows and columns, where each row corresponds to a state (i.e., a node), and each column represents the possible actions (i.e., selecting other nodes as the next state). Consequently, the Q-table size is the number of nodes multiplied by the number of actions. However, since nodes in WSNs are resource-constrained, storing the entire Q-table is impractical, especially in dense networks. Therefore, Aris-RPL utilizes only a single row of the Q-table per node. Instead of maintaining the complete Q-table, each node stores a one-dimensional array sized according to its neighbors.

4.3.1. The Reward Function

Integrating the routing metrics mentioned above into the reward function requires specific preliminary steps. The proposed approach aims to provide an adaptive load-balancing and congestion solution while maintaining network resources. Consequently, routing metrics such as node buffer utilization and overflow ratio significantly affect the reward value and the neighbor Q-value. Therefore, high buffer utilization and overflow ratio levels will negatively impact the reward calculation. Thus, the following equations calculate these metrics:

where are design parameters. They represent the thresholds after which the parent node is considered to experience high Overflow Ratio (OFR) and Buffer Utilization (BU) levels, respectively. Additionally, the RSSI metric must be normalized by adjusting its value to a standard scale so it can be combined linearly with the rest of the metrics. The proposed approach uses min-max normalization for this purpose. Consequently, to address the multi-objective nature of the routing requirement, neighboring nodes are rewarded based on their link/node conditions according to

where is the obtained reward when a node selects node as a preferred parent. Here, the reward function is designed intentionally to have a linear combination in Equation (8) for computational simplicity and low overhead, which is essential for resource-constrained nodes. Moreover, using a logarithmic scaling in Equations (6) and (7) serves as a critical safety constraint that only activates when a node approaches a failure state. This is an intended design choice to prioritize network reliability, congestion, and load balancing management. Specifically, even with the equal weighting in Equation (8), the weighting principles are applied implicitly through the interplay between linear Equation (8) and non-linear logarithmic penalties in Equations (6) and (7), allowing the protocol to prioritize link quality under normal conditions while automatically penalizing when a node approaches the predefined thresholds. For example, as the buffer ratio approaches its maximum value (e.g., BU to 1), the penalizes aggressively, providing a powerful, non-linear negative reward that discourages the selection of nodes nearing congestion. Moreover, using EWMA smoothing in Equation (4) ensures that while the system is highly sensitive to sustained congestion, it remains resilient to momentary spikes, which is a vital component of the approach’s implicit weighting strategy.

Now, depending on the status of the neighboring nodes in the network, additional rewards and penalties are assigned, which will be explained in detail. Aris-RPL considers , , and values to handle various situations. This dynamism is essential to achieving the proposed approach’s goals. Specifically, will equal the if the next step node is the root. The is applied if the next node is one hop from the root to encourage data packet forwarding toward the root. is used to avoid routing loops, sending data downward, and nodes that exceed the child counter threshold . The threshold value is determined based on the application and network conditions. A smaller value results in a more balanced DODAG graph. However, if the value is too small, it can negatively affect parent selection and QoS, as nodes might not be able to find an appropriate parent. In our simulation, we set the CC threshold to 5. This mechanism helps address the thundering herd problem by balancing the load, even when a new node with better conditions joins the network. Next, the calculated rank from Equation (8) is applied otherwise. Consequently, Equation (9) calculates the final reward. Then, according to Equation (1), the q-value is calculated. Furthermore, the maximum neighbor nodes’ q-value is appended to the DIO metric container to be sent and used by other nodes.

Finally, the node’s best parent is determined to be the neighboring node with the highest q-value.

4.3.2. Q-Learning Value Function

As mentioned earlier, the routing policy of the proposed approach works in three phases. This function builds the Q-table, and as explained in Section 2, the entry values in the Q-table, known as Q-values, are calculated and updated based on Equation (1). These Q-values reflect the penalties and benefits of taking a particular candidate parent node based on reinforcement signals received from neighboring nodes. In the proposed approach, DIO messages contain these signals, which are disseminated periodically according to the Trickle algorithm. The information needed to update the Q-values, including the maximum Q-value of the neighbor and the routing metrics, is appended in the DIO message. Therefore, the modified body of the DIO message includes RE, OFR, BU, and the maximum Q-value of the neighbor. Consequently, when receiving a DIO message, the node updates its Q-table according to appended information. It is worth noting that by propagating and using the maximum Q-value in Equation (1) with a discount factor of 0.7, Aris-RPL considers aggregated rewards beyond the one-hop neighborhood indirectly. Additionally, at the beginning of the network start-up, all nodes initialize the new entries of the Q-table for the first time, receiving DIO messages with:

where represents the hop count of node . As DIO messages are exchanged and time progresses, the q-values converge to their desired values. Algorithm 1 explains the Q-learning algorithm function. Upon receiving a DIO message from a neighbor node, the node first sets the learning rate, discount factor, and approach hyperparameters such as thresholds and normalization values, etc. (lines 1–3). The node extracts the routing metrics from the DIO message (line 4). Then, the algorithm normalizes the calculated RSSI and calculates OFR and BU according to (6, 7) (lines 7–9). Eventually, it calculates the reward based on the normalized metrics (line 10). Then, to update the Q-table, the node considers two conditions. When an unknown node sends a DIO message, this new neighbor is initialized and added to both tables of Q-values and the parent set, with a value assigned to it (lines 11–15). If the neighbor node is known, its Q-value is updated based on the current node and network status (lines 16–29). Finally, the node updates its routing metrics and identifies the highest Q-value among neighbors. This information is then embedded in the DIO message. DIO contains all the needed information about network conditions (lines 30–31). Network nodes execute the Q-function whenever they receive a DIO message. Consequently, nodes can select one of their neighbors as the next forwarder based on the selection function of the approach’s next phase.

| Algorithm 1 The Q-learning Algorithm | |||

| Input: Incoming DIO message from Neighboring j | |||

| Output: Outgoing DIO message with Updated metrics, Update the Q-Table | |||

| 1 | Define: D_Factor , L_Rate , Buffer Utilization threshold , | ||

| 2 | Overflow ratio Utilization threshold RSSImax, RSSImin, | ||

| 3 | Max Child Count (CC), Extra, Penalty, Rmax; | ||

| 4 | Define: Routing Metrics (BU, OFR, RE, CC); | ||

| 5 | Neighboring_Node Nj, Receiving_Node Ni | ||

| 6 | Begin: | ||

| 7 | RSSIj ← Calculate RSSIj; | ||

| 8 | Calculate OFR, BU according to (6) and (7); | ||

| 9 | Normalize RSSIj; | ||

| 10 | Rewardj ← Calculate Reward (Routing Metrics); | ||

| 11 | if Nj is new then | ||

| 12 | Parent-Set[j].ParentID ← DIOj.NodeID; | ||

| 13 | Q-Table[j].ParentID ← Parent-Set[j].ParentID; | ||

| 14 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue ← QValueInitial; | ||

| 15 | end | ||

| 16 | if Nj is not new then | ||

| 17 | if Nj is the Netwotk_root then | ||

| 18 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue is updated with (Rmax); | ||

| 19 | end | ||

| 20 | else if Nj is a root’s child then | ||

| 21 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue is updated with Rewardj + Extra; | ||

| 22 | end | ||

| 23 | else if Nj.Rank >Ni.Rank or CC is maximum then | ||

| 24 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue is updated with Penalty; | ||

| 25 | end | ||

| 26 | else | ||

| 27 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue is updated with Rewardj; | ||

| 28 | end | ||

| 29 | end | ||

| 30 31 | /Outgoing DIO message contains Updated routing metrics, and the max neighboring Q-value; | ||

| 32 | exit: | ||

4.4. Selection Algorithm

The first and second phases of the proposed approach are executed by this function, which represents the vital component of the new RPL protocol’s objective function. This function is invoked whenever a routing decision needs to be made. As previously discussed, a key consideration in reinforcement learning algorithms is balancing the exploitation and exploration phases.

A practical action selection strategy must be adopted to avoid falling into a locally optimal solution. During the exploration phase, the agent will explore all possible actions over several episodes and choose actions randomly. Aris-RPL uses the SoftMax selection strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. The SoftMax method offers a probabilistic approach that selects the actions based on their relative Q-values. It means that the value of the parent reward affects the probability of choosing the parent. The selection probability for an action is given by:

where is the probability of selecting a node by node as a parent. is the Q-value of neighbor node j. is an exploration parameter. represents the node i’s neighbor set. In the SoftMax selection strategy, when is large the action selection probabilities become more uniform, encouraging exploration. Conversely, when is small, the probabilities become more biased towards actions with higher Q-values, favoring exploitation. A common approach is to start with a higher to promote exploration and gradually decrease it over time to shift toward exploitation. This can be achieved using a decay schedule according to Equation (12). In our proposed approach, exploration is performed according to the number of time steps or episodes, where ≤ . During exploration, Aris-RPL initiates with a large value to make selection probabilities more uniform. Then, is calculated according to Equation (12). Next, Equation (11) calculates the selection probability of nodes regarding their Q-values. Over time, decreases with the increase of parameter t:

where represents the initial value, is the decay rate, and is the time step according to the variable value (for example, when episode = 3, then t = 3). The algorithm transitions to the exploitation phase when the variable reaches where represents the initial value, is the decay rate, and is the time step according to the variable value (for example, when episode = 3, then t = 3). The algorithm transitions to the exploitation phase when the variable reaches the maximum value . At this point, the algorithm chooses a parent based on the highest Q-value of all candidates.

Algorithm 2 outlines the selection algorithm used in the approach. Firstly, the algorithm defines the parameters (the initial value , decay rate , and ) (line 1). If the parent set is empty, the node explores its vicinity and broadcasts a DIS message to solicit DIO and avoid disconnection from DODAG (lines 3 to 5). Next, the exploration phase begins. During this phase, the exploration value is calculated according to (12) (line 7). The preferred parent is then selected probabilistically (line 8). After each iteration, the episode count is incremented by 1 (line 9). When the episode count reaches its maximum value, , the algorithm transitions to the exploitation phase, where a parent with the highest Q-value is selected (lines 11–13). Afterward, the proposed approach is ready to execute the third phase.

| Algorithm 2 Subsequent Node Selection Algorithm | ||||

| Input: Data Packet from a child node | ||||

| Parent-set and Q-table of the current node | ||||

| Output: Preferred next hop node (Parent) | ||||

| 1 | Define: Init value , episodeMax, | |||

| 2 | Begin: | |||

| 3 | if (Parent-set is Empty) then | |||

| 4 | broadcast a DIS message; | |||

| 5 | end | |||

| 6 | if episode ≤ episodeMax then //Exploration | |||

| 7 | according to (12); | |||

| 8 | Preferred-Parrent ← Select from parent-set according to PRi(j) in (11); | |||

| 9 | episode++; | |||

| 10 | end | |||

| 11 | if episod > episodMax then//Exploitation | |||

| 12 | Pmax ← Find QvalueMax(Parent-set, Q-Table); | |||

| 13 | return Pmax; | |||

| 14 | end | |||

| 15 | exit: Selected preferred parent | |||

4.5. Network Topology Monitoring Management Function

The third phase is executed during the exploitation after choosing the preferred parent to respond to potential and rapid network changes. As explained earlier, our reinforcement learning approach updates network information through DIO messages in the exploration phase and utilizes this information in the exploitation phase. Aris-RPL halts DIO transmission in the exploitation phase by resetting the Trickle timer period. This significantly reduces overhead without affecting performance. In standard RPL, the Trickle timer’s long intervals between consecutive DIO transmissions can result in inaccurate and outdated congestion information about the node’s vicinity. Aris-RPL ensures timely and accurate network updates, addressing frequent network changes effectively as follows: During the exploitation phase, each node starts a timer to monitor the OFR metric. If the OFR value exceeds the congestion threshold during timer T, the node will send a DIO message to inform its child nodes of the new update, resulting in an update to its Q-value according to Algorithm 1 and returning to exploration. If OFR does not exceed , reset timer T and repeat the process. This observation timer T is numerically defined as the initial Trickle transmission interval (Imin = 4 s) in our experiments, ensuring the monitoring phase captures congestion with the same granularity as the protocol’s most responsive state. Noteworthy, based on the previous algorithms, the node only breaks the silence in the exploitation phase when a physical buffer accumulation is accompanied by a mathematically confirmed reliability crisis, initiating either a global or local repair, meaning resetting the Trickle timer to send DIO messages and disseminate the new information repeatedly. Resetting the timer also resets the episode parameter, activating the exploration phase.

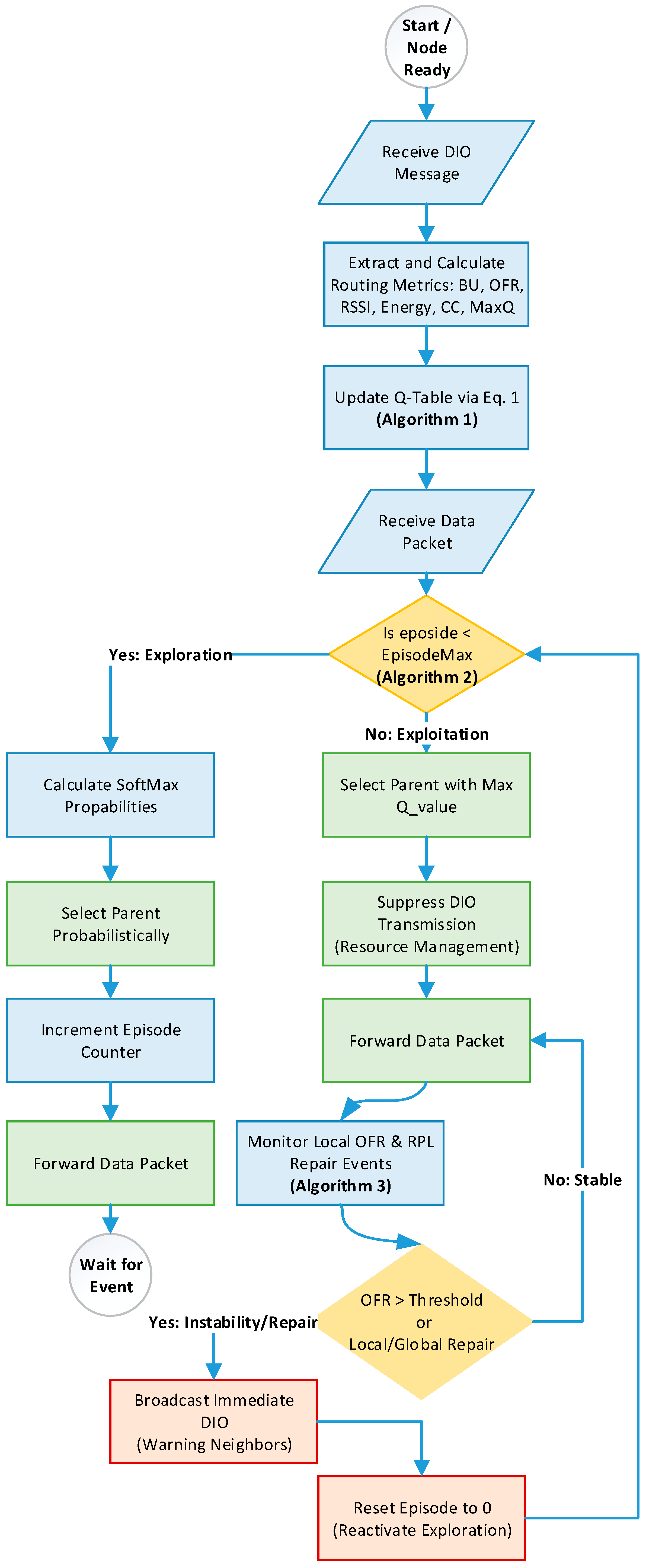

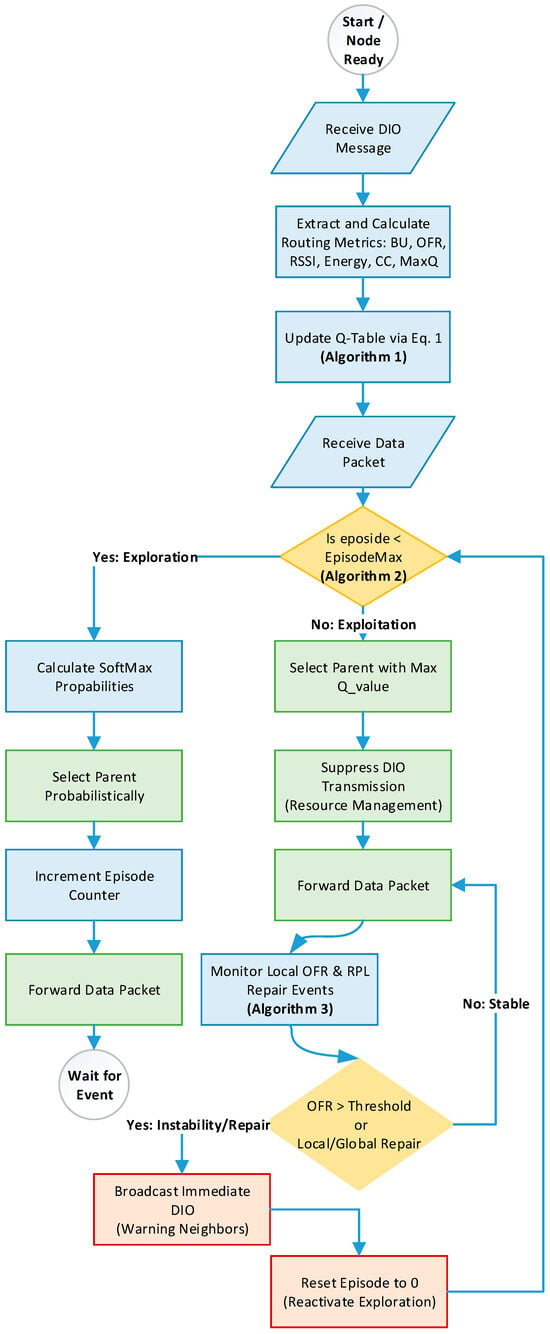

Algorithm 3 explains the related function. Firstly, the algorithm defines the parameters (the Timer T and the congestion threshold ) (line 1). While the node is in the exploitation phase, it starts a timer T and calculates the OFR and other metrics every T (lines 3–5). If the OFR value exceeds the congestion threshold , the node broadcasts a DIO message to inform child nodes of the new update (lines 6–8). Finally, if a local or global repair happens, reset the Trickle timer t and episode counter (lines 10–13). It is worth mentioning that the initialization time is set to 180 s, meaning this is the required time to startup network, to transit from uniform exploration to biased exploitation, and before starting to collect environmental data. Moreover, since there is an interaction between the topology monitoring phase and the Trickle algorithm, we have defined the upper bound on recovery delay when Aris-RPL triggers an immediate DIO broadcast upon detecting congestion as UBD as the summation of T (the monitoring timer) and Imin (the minimum Trickle interval). As a result, the maximum recovery delay for disseminating a topology update is 8 s. Figure 6 illustrates the complete workflow of the proposed framework. It demonstrates the interdependencies between the different phases: (1) Building and updating the Q-table utilizing Algorithms 1 and 2, Exploration and Exploitation phases utilizing Algorithms 2 and 3, and the Topology Monitoring phase utilizing Algorithm 3. This comprehensive workflow demonstrates how the Q-learning agent builds a Q-table, transitions from exploration to optimal parent selection, and maintains network stability through reactive monitoring.

| Algorithm 3 Topology Monitoring and Management | ||||

| Input: Data Packet from a child node, | ||||

| Q-table of the current node | ||||

| Output: DIO message, possible exploration activating | ||||

| 1 | Define: Timer , congestion threshold | |||

| 2 | Begin: | |||

| 3 | while Exploitation do | |||

| 4 | Start TIMER T; | |||

| 5 | Calculate OFR, and other metrics every T; | |||

| 6 | if OFR ≥ then | |||

| 7 | broadcast a DIO message with the last node metrics; | |||

| 8 | end exit; | |||

| 9 | end | |||

| 10 | if local or global repair then | |||

| 11 | Reset the Trickle timer t; | |||

| 12 | Reset episode counter; | |||

| 13 | end | |||

| 14 | exit: | |||

Figure 6.

The Complete Workflow of Aris-RPL.

5. System Setup and Results

Aris-RPL has been evaluated using the InstantContiki OS 3.0 64-bit with the GUI Cooja simulator environment [52] running on a physical workstation with an Intel Core i7 9th CPU, a 16-bit operating system, an NVidia GeForce GTX 1650 GPU, and 16 GB of RAM. This environment is widely accepted in many IoT studies [13]. One of its strengths is the integration of the MSPSim instruction-level emulator, which provides realistic simulations with accurate timing, especially for the famous Texas Instruments MSP430 microprocessor-based hardware platforms [53], besides using CSMA (Carrier Sense Multiple Access) methods in its Medium Access Control (MAC) layer [54] that mitigates interference through mechanisms such as collision avoidance. In addition, Cooja supports various sensor networking platforms, such as the Zolertia One (Z1) and Tmote Sky.

The Z1 platform was chosen in simulation scenarios due to its accurately emulated model in Cooja, which ensures more realistic IoT scenarios and precise results. The major specifications of the Z1 platform are shown in Table 2 [55]. It is worth noting that the Z1 platform contains the CC2420 module, an IEEE 802.15.4-compliant RF transceiver developed by Texas Instruments. This module is designed for low-power and low-voltage wireless applications and is widely used in real-world implementations [56]. The study introduced in this paper has considered various topology scenarios for extensive evaluations. These scenarios were designed to reflect critical aspects the approach needs to address: density, traffic rates, and path diversity.

Evaluating these aspects is essential to demonstrating the strength of the Aris-RPL for selecting more load-balanced network paths. Accordingly, we evaluated three scenarios with different node densities: 50, 75, and 100 nodes. The network area in each scenario is 100 × 100 m2 with randomly located nodes. Each scenario was evaluated with two different traffic rates: 5 packets per minute and 10 packets per minute, in which all nodes create the traffic. Moreover, each scenario was executed for 5 independent iterations, with a simulation duration of 3600 s (1 h) per run, different random setups, and 95% Confidence Intervals. Additionally, for random topology, nodes were placed using a random distribution in each of the 5 iterations, creating different layouts with bottleneck points for every run. The complete simulation settings and the list of parameter meanings of Aris-RPL are detailed in Table 3, respectively. Additionally, to demonstrate its effectiveness, the following approaches are implemented and used in evaluation scenarios:

- RPL- MRHOF represents the original version of RPL. Its objective function uses the ETX link quality metric as the selection criterion of the preferred parents [21]. The comparative analysis and performance evaluation with RPL-MRHOF allow us to highlight the improvements achieved by Aris-RPL over traditional RPL.

- A Learning-Based Resource Management for Low Power and Lossy IoT Networks [9], which is referred to as MAB in later sections. It is a machine learning approach that operates on distributed nodes within the Contiki/RPL framework like Aris-RPL, and utilizes the multiarmed bandit (MAB) technique to optimize performance in dynamic IoT networks. According to the MABs authors, it has demonstrated superior results against load-balancing and congestion-aware RPL enhancements such as [26,27]. Algorithms 4 and 5 explain the MAB approach used in this study, and the related simulation settings are detailed in Table 4.

- A congestion-aware routing algorithm in Dynamic IoT Networks [41], which is referred to as CRD in later sections. It is a Q-learning approach for dynamic IoT networks under heavy-load traffic scenarios. CRD aligns closely with the reinforcement learning principles used in Aris-RPL. It adopts the Q-learning algorithm at each node to learn an optimal parent selection policy to tackle the load-balancing challenges in RPL networks. Algorithms 6 and 7 explain the MAB approach used in this study, and the related simulation settings are detailed in Table 5.

| Algorithm 4 Multi-armed Bandit-learning-based algorithm MAB | |||

| Input: Neighbor set N(x) for each node x that contains n neighbors. | |||

| Output: Update the Q-Table | |||

| 1 | Define: L_Rate , r+, r−, Neighbor j; | ||

| 2 | re_limitsmax = 3 | ||

| 3 | ba-off_stagesmax = 5 | ||

| 4 | Define: CWmin = 0, CWmax = 31 | ||

| 5 | c_reward = 0, Qn(a) = 0, Qn+1(a) = 0 | ||

| 6 | Begin: | ||

| 7 | ETXj ← Calculate ETX using neighbor_link_callback (); | ||

| 8 | EEXj ← Calculate EEX from ETX; | ||

| 9 | Evaluate reward; | ||

| 10 | if C_EEX ≤ Pr_EEX then reward = r+ | ||

| 11 | else reward = r− | ||

| 12 | For Action (a) update r_table; | ||

| 13 | Using the following update the Q-values table | ||

| 14 | |||

| 15 | end if | ||

| 16 | End | ||

| 17 | exit: | ||

| Algorithm 5 MAB Selection algorithm | |||

| Input: Data Packet from a child node | |||

| Output: Preferred next hop node (Parent) | |||

| 1 | Define: I = Imin, counter c = 0, Root = R, Node = n, Parent = p; | ||

| 2 | Begin: | ||

| 3 | set I = I × 2 | ||

| 4 | if Imax ≤ I then I = Imax | ||

| 5 | end if | ||

| 6 | if exploitation then | ||

| 7 | Select parent y with minimum Q-value ∀ y ∈ N(x) | ||

| 8 | Suppress DIO transmissions | ||

| 9 | end if | ||

| 10 | if exploration then | ||

| 11 | if n = R then R rank = 1 | ||

| 12 | end if | ||

| 13 | if p = null then rank = pathankmax | ||

| 14 | end if | ||

| 15 | if p != null then rank = h + Rank(pi) + r_increase | ||

| 16 | r_increase = EEX | ||

| 17 | end if | ||

| 18 | return MIN (Baserank + r_increase) | ||

| 19 | embed r_increase in DIO | ||

| 20 | ttimer = random [I/2, I] | ||

| 21 | if (network is stable) then counter ++ | ||

| 22 | else | ||

| 23 | I = Imin | ||

| 24 | if (ttimer expires) then broadcast DIO | ||

| 25 | end if | ||

| 26 | end if | ||

| 27 | end | ||

| 28 | exit: Selected preferred parent | ||

| Algorithm 6 Congestion-Aware Routing using Q-Learning (CRD) | |||

| Input: Incoming DIO message from Neighboring j | |||

| Output: Outgoing DIO message with Updated metrics, Update the Q-Table | |||

| 1 | Define: BFth, L_Rate , η; | ||

| 2 | Define: Routing Metrics (BFj, HCj); | ||

| 3 | Neighboring_Node Nj, Receiving_Node Ni | ||

| 4 | Begin: | ||

| 5 | ETXj ← Calculate ETXj; | ||

| 6 | Decode BFj and HCj from the received DIO message; | ||

| 7 | max (BFj/BFth, 1 − BFj/BFth) | ||

| 8 | Rj ← BFj + ETXj + HCj | ||

| 9 | if Nj is new then | ||

| 10 | Parent-Set[j].ParentID ← DIOj.NodeID; | ||

| 11 | Q-Table[j].ParentID ← Parent-Set[j].ParentID; | ||

| 12 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue ← QValueInitial; | ||

| 13 | end | ||

| 14 | if Nj is not new then | ||

| 15 | Q-Table[j].Parentqvalue Qold(j) + [Rj − Qold(j)]; | ||

| 16 | end | ||

| 17 | BFi | ← Calculate BFi | |

| 18 | HCi | ← Calculate HCi | |

| 19 | Encode BFi and HCi in the Outgoing DIO message | ||

| 20 | /Outgoing DIO message contains updated routing metrics; | ||

| 21 | exit: | ||

| Algorithm 7 CRD Selection Algorithm | |

| Input: Data Packet from a child node | |

| Parent-set and Q-table of the current node | |

| Output: Preferred next hop node (Parent) | |

| 1 | Define: exploration factor , Consecutive q_losses ,, Timer X, Imin |

| 2 | Begin: |

| 3 | if (Parent-set is Empty) then |

| 4 | broadcast a DIS message; end |

| 5 | Compute selection probabilities using: |

| 6 | Select the preferred parent y with the highest probability Px(y) |

| 7 | Reset Trickle Timer: |

| 8 | Reset the Trickle timer to Imin if the node detects consecutive queue losses |

| 9 | Increase by after each reset to limit overhead |

| 10 | Reinitialize timer values if no losses occur within interval X |

| 11 | exit: Selected preferred parent |

Table 2.

Z1 Sensor Node Specifications [55].

Table 2.

Z1 Sensor Node Specifications [55].

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Micro-Controller Unit (MCU) | 2nd MSP430 generation |

| Architecture | 16-bit RISC (Upgraded to 20 bits) |

| Radio Module | CC2420 |

| Operating MCU Voltage Range | 1.8 V < V < 3.6 V |

| CC2420 Voltage Range | 2.1 V < V < 3.6 V |

| Operating Temperature | −40 °C < θ < +85 °C |

| Off Mode Current | 0.1 µA |

| Radio Transmitting Mode @ 0 dBm | 17.4 mA |

| Radio Receiving Mode Current | 18.8 mA |

| Radio IDLE Mode Current | 426 µA |

Table 3.

Simulation Settings.

Table 3.

Simulation Settings.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Area | 100 × 100 m2 |

| Nodes’ Number | 50, 75, 100 |

| Sink Number | 1 |

| Radio Channel Model | UDGM Distance Loss |

| Com./Interference Range | 30 m/40 m |

| Traffic Rate | 5 ppm, 10 ppm |

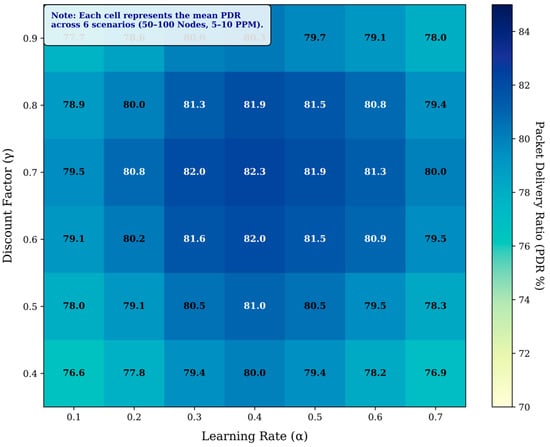

| α, γ | 0.4, 0.7 |

| 0.3, 0.7 | |

| Penalty | −3.0 |

| RMax, Rextra | 100, 5.0 |

| Max Child Count CC | 5 |

| , , | 2.0, 0.2, 0.3 |

| Episodemax | 10 |

| Initialization time | 180 s |

| Simulation Duration | 3600 s |

| Simulation Speed | No speed limit |

| Simulation Iteration Number | 5 times |

Table 4.

MAB Main Simulation Parameters.

Table 4.

MAB Main Simulation Parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| PHY and MAC protocol | IEEE 802.15.4 with CSMA/CA |

| Radio model Unit disk graph medium (UDGM) | UDGM—Radio model Unit disk graph medium |

| Buffer size | 4 packets |

| UIP payload size | 140 bytes |

| Imin | 10 |

| Imax | 8 doubling |

| Initial reward = 0 | 0 |

| Initial Q1(a) = 0 | 0 |

| Learning Rate (α) | 0.6 |

| Reward Function | +1 (improved EEX), −1 (worsened EEX) |

| Maximum retry limit | 3 |

| Maximum Backoff stage | 5 |

| Number of stored reward values for action a | 5 |

Table 5.

CRD Main Simulation Parameters.

Table 5.

CRD Main Simulation Parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| PHY and MAC protocol | IEEE 802.15.4 with CSMA/CA |

| Radio model | UDGM |

| Learning rate (α) | 0.3 |

| Congestion threshold (BFth) | 0.5 |

| η the positive integer to enable decoding correctly | 100 |

| Exploration factor (θ) | 2 |

| defines the number of consecutive queue losses of a node | 2 |

| Timer X | 100 ms |

| Imin | 3 s |

It is important to emphasize that for all the protocols, the Trickle Timer Settings are the same. All protocols were tested under strictly identical physical and network conditions using the same random topology seeds, and they operated over the same 6LoWPAN/IPv6 and CSMA MAC layers. Finally, the following performance metrics have been considered in the experiments: (1) Packet Delivery Ratio, (2) Control Traffic Overhead, (3) Energy Consumption, and (4) End-to-End Delay. The details of the evaluation results are discussed in the following:

5.1. Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)

PDR reflects the routing policy reliability, especially in dense network scenarios, and represents the percentage of successfully received packets during the network lifetime. This performance metric is calculated based on the following equation.

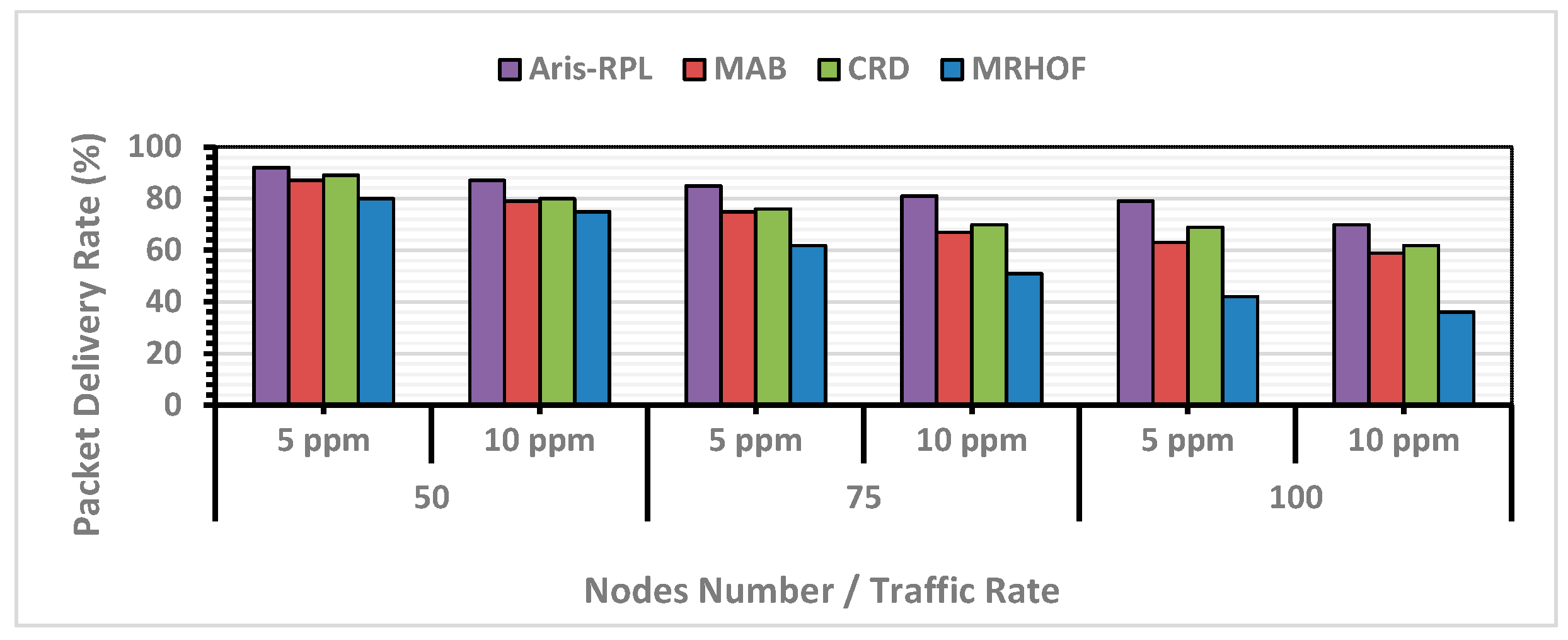

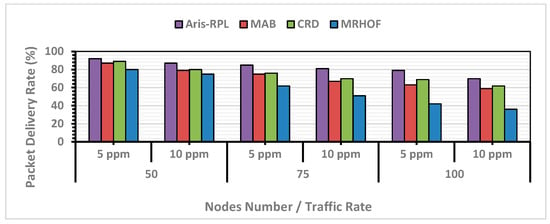

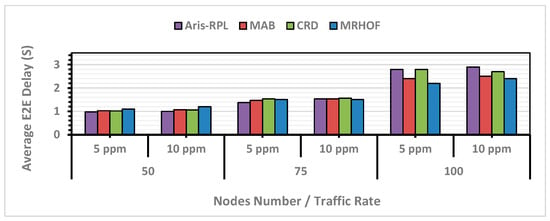

where is the total number of packets successfully delivered to the root, and is the total number of packets transmitted during the simulation by the IoT nodes. Figure 7 demonstrates that the proposed approach outperforms its counterparts concerning PDR. For instance, in the first scenario with 50 nodes and a traffic rate of 5 ppm, the proposed approach achieved the highest PDR at 92%. Here, compared to MRHOF, MAB, and CRD, PDR was improved by 15%, 5%, and 4%, respectively.

Figure 7.

PDR Results in Different Network Scenarios.

On the other hand, as network size and traffic rate increase, the PDR for all approaches declines due to rising congestion and overflow levels. However, our proposed approach consistently performed well across all scenarios compared to other methods. MRHOF, despite using a probing mechanism to measure link quality, exhibited the lowest PDR in all scenarios. This is because the original objective functions in the RPL protocol lack a mechanism to deal with load imbalance and uneven traffic loads. Both CRD and MAB showed almost similar results for all scenarios, benefiting from intelligent routing policies, with CRD having a slight distinction due to an effective learning load-balancing process. Actually, all terms (the linear terms (RSSI, Energy) and logarithmic congestion penalties (OFR and BU)) in the linear design of the reward function work together as a constrained optimization. The linear terms determine the optimal path, subject to the constraints imposed by the logarithmic penalties. This is an intentional design choice to prioritize network reliability, congestion, and load balancing management. In this case, a path is only considered optimal if it is both high-quality and safe. Moreover, reducing the number of control packets during the exploitation phase significantly lowers channel contention and the probability of collisions. According to Figure 7, the proposed method, on average, enhanced PDR for all scenarios compared to MRHOF, MAB, and CRD by 51%, 15%, and 11%, respectively.

5.2. Control Traffic Overhead

RPL protocol uses, as explained in Section 2, ICMPv6 control messages during the network lifetime to construct and maintain the network DODAG, which involves exchanging DIO, DAO, and DIS messages according to the Trickle timer mechanism. These messages are essential for maintaining network stability and responding to network dynamics and node/link metrics changes. Furthermore, the number of these messages directly impacts energy consumption, and it is a crucial metric indicating the protocol’s ability to handle network conditions such as congestion, load balancing, and unstable radio links. Equation (14) calculates the control overhead metric. Where and are the numbers of all DIO, DAO, and DIS messages, respectively:

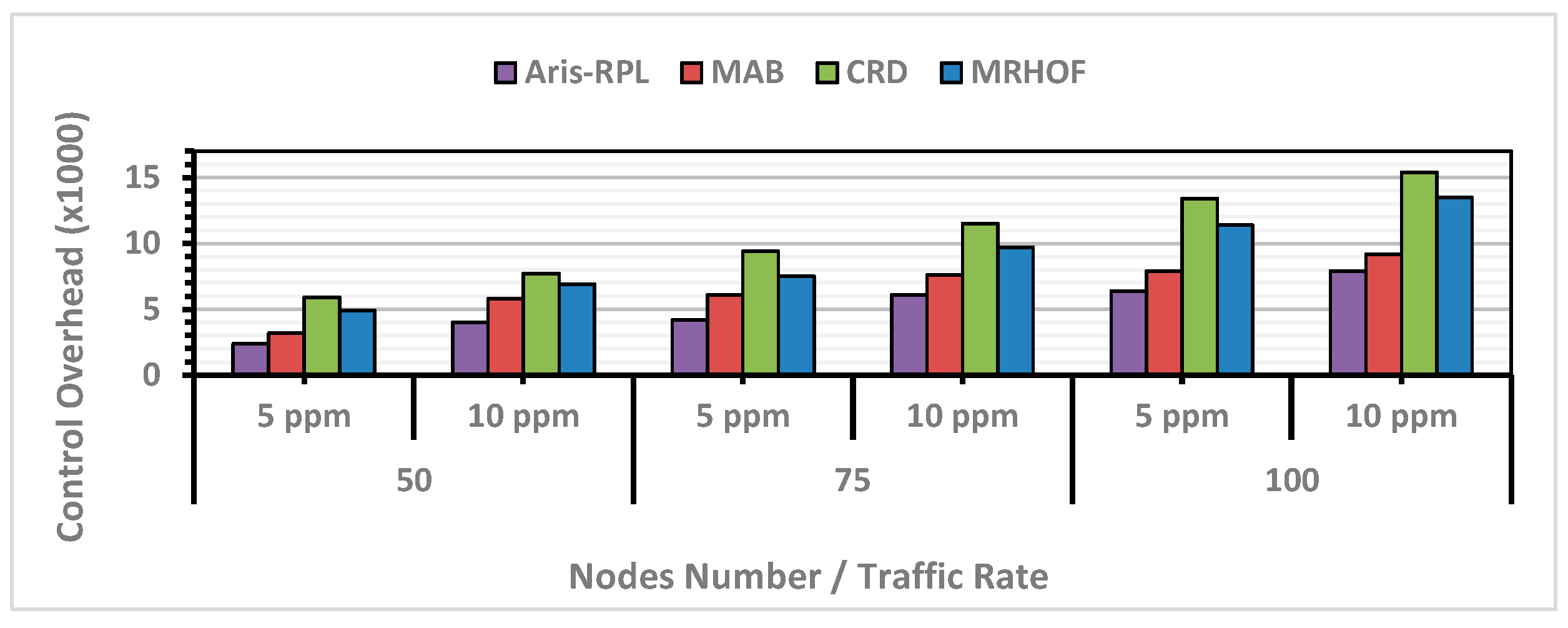

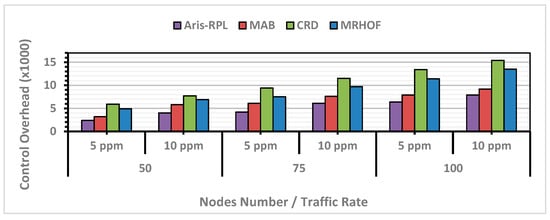

According to the results in Figure 8, all approaches have shown an increasing trend in control overhead numbers as the number of nodes rises, which is expected. MRHOF has a higher overhead percentage than other approaches.

Figure 8.

Control Overhead Results in Different Network Scenarios.

It is worth mentioning that despite the high number of control overheads, MRHOF did not achieve a significant increase in PDR, indicating that much network traffic is wasted on transmitting and receiving control overheads without effectively responding to network dynamics. The primary reason is that MRHOF cannot address load-balancing and congestion issues, leading to a highly unstable network. Surprisingly, CRD showed the highest control overhead among all approaches, especially under heavy load, as illustrated in the third scenario. CRD, based on its methodology, resets the Trickle timer more frequently to respond to sudden network changes, resulting in more overhead exchanges. However, this increased overhead led to an improvement in PDR results. On the other hand, MAB managed to reduce control overhead compared to MRHOF and CRD without degrading performance due to DIO suppression during the exploitation phase. However, the MAB routing policy did not introduce a mechanism to quickly respond to rapid network changes during the exploitation phase, affecting its PDR results in more complex scenarios. In contrast, Aris-RPL demonstrated moderate control overhead with high PDR outcomes due to the precise selection of link/node metrics considering congestion and load-balancing status, applying the DIO suppression during the topology monitoring and management phase. According to Figure 8, the proposed method, on average, enhanced the control overhead for all scenarios compared to MRHOF, MAB, and CRD by 43%, 23%, and 51%, respectively.

5.3. Energy Consumption

According to [57], the node consumes most of the energy resources in communication activities during packet transmission. Consequently, the nodes far from their parents need to utilize more energy. The transmission energy is the required energy to transmit k-bit data to a node at a distance . It is calculated as follows:

where is the required energy to run transmitter circuits, is the required energy to transmit amplifiers, and is the path loss index. The typical values of these parameters are and respectively [9]. In our proposed approach, according to [58], the total energy consumption in every node consists of four communication modes: (1) CPU mode, (2) Transmission mode, (3) Receiving mode, and (4) Low Power mode. Contiki OS uses the module to estimate a node’s power consumption by providing the accumulated time the sensor node spends in various communication modes. The following formulas are used to measure the energy consumption in each state [9]:

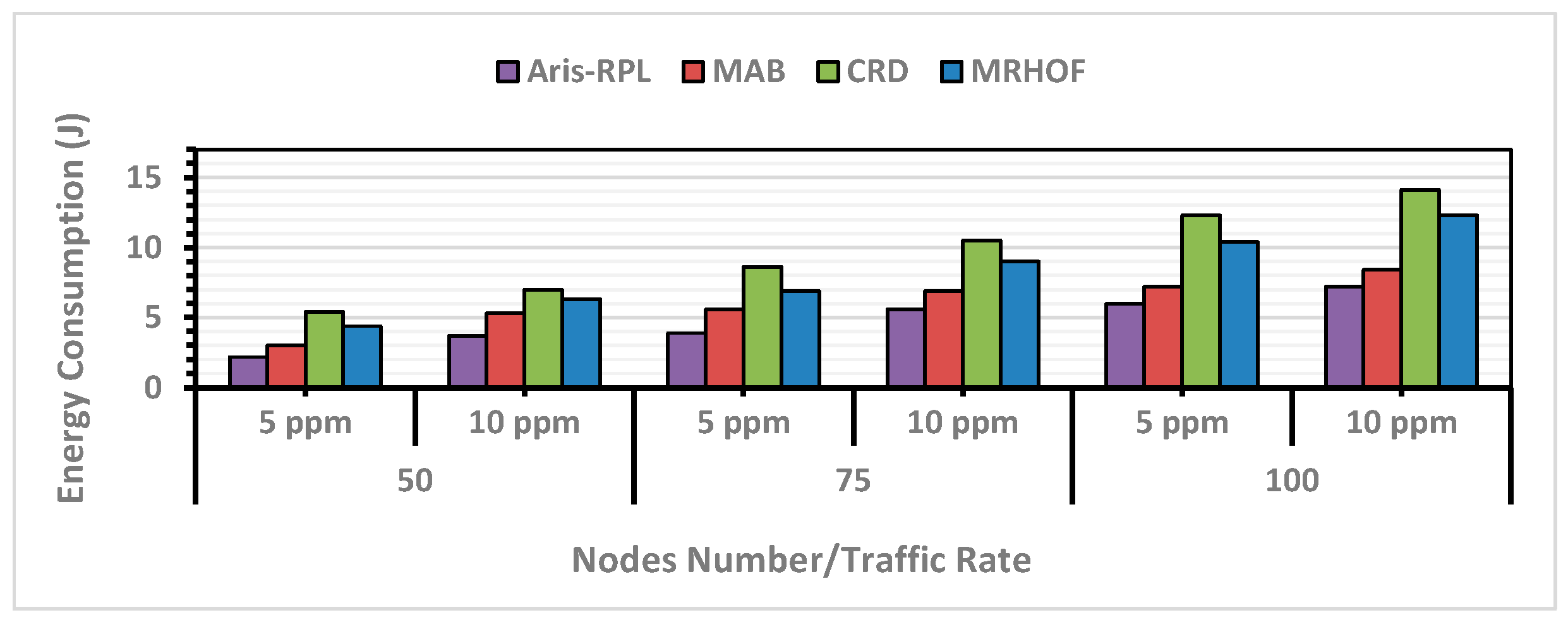

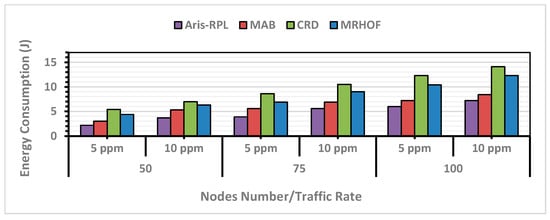

The model in Contiki OS has the function that provides the value of , , , and variables in (16), respectively. The numbers in these equations are according to the Z1 mote standard specifications [59]. For instance, 17.4 mA is the current consumption required to run the transmission unit in the CC2420 module of Zolertia 1 mote, which consumes 3 V, and 32,768 is the tick-per-second value of the Z1 mote. The total energy consumption for each node is calculated by summing the energy consumed according to (16) during the simulation. To analyze the results shown in Figure 9, we observe that the control overhead and PDR results directly impact the nodes’ total energy consumption, as communication is the primary energy-consuming activity.

Figure 9.

Total Energy Consumption Results in Different Network Scenarios.

Generally, energy consumption increases with the number of successfully delivered data packets and the transmitted control overhead. For instance, when the network becomes denser and congested, leading to load-balancing issues and instability, resulting in more overhead transmissions. Therefore, effectively handling these concerns is necessary.

In all scenarios, MRHOF and CRD consumed the highest amount of energy. MRHOFs high energy consumption is due to its probing mechanism and inability to address congestion and load balancing. CRDs high energy consumption results from frequent Trickle timer resets and PDR results. In comparison, MAB reduced the total energy consumption but was not as effective as the Aris-RPL because MAB relies on the ETX metric in its routing criteria, which consumes energy while probing.

Aris-RPL not only intelligently integrates well-selected link/node metrics (including energy metrics) to select the subsequent forwarder nodes but also quickly responds to network changes without resetting the Trickle timer. This is important since in low-power wireless protocols, energy consumption is dominated by the radio’s startup, which occurs regardless of packet size. As a result, reducing the frequency of control overhead during the exploitation phase and not utilizing the ETX metric leads to a higher Packet delivery ratio and lower control overhead, meaning that most energy consumption is used during data packet transmissions. According to Figure 9, the proposed method, on average, enhanced energy consumption for all scenarios compared to MRHOF, MAB, and CRD by 42%, 22%, and 50%, respectively.

5.4. E2E Delay

End-to-end delay represents the time a packet takes from the source to reach the final destination (the root) [16]. The total delay is the summation of differences between the sending and receiving times for all data packets being successfully delivered. The average delay is obtained by dividing the total delay by the total number of received packets. The following equations calculate the delay:

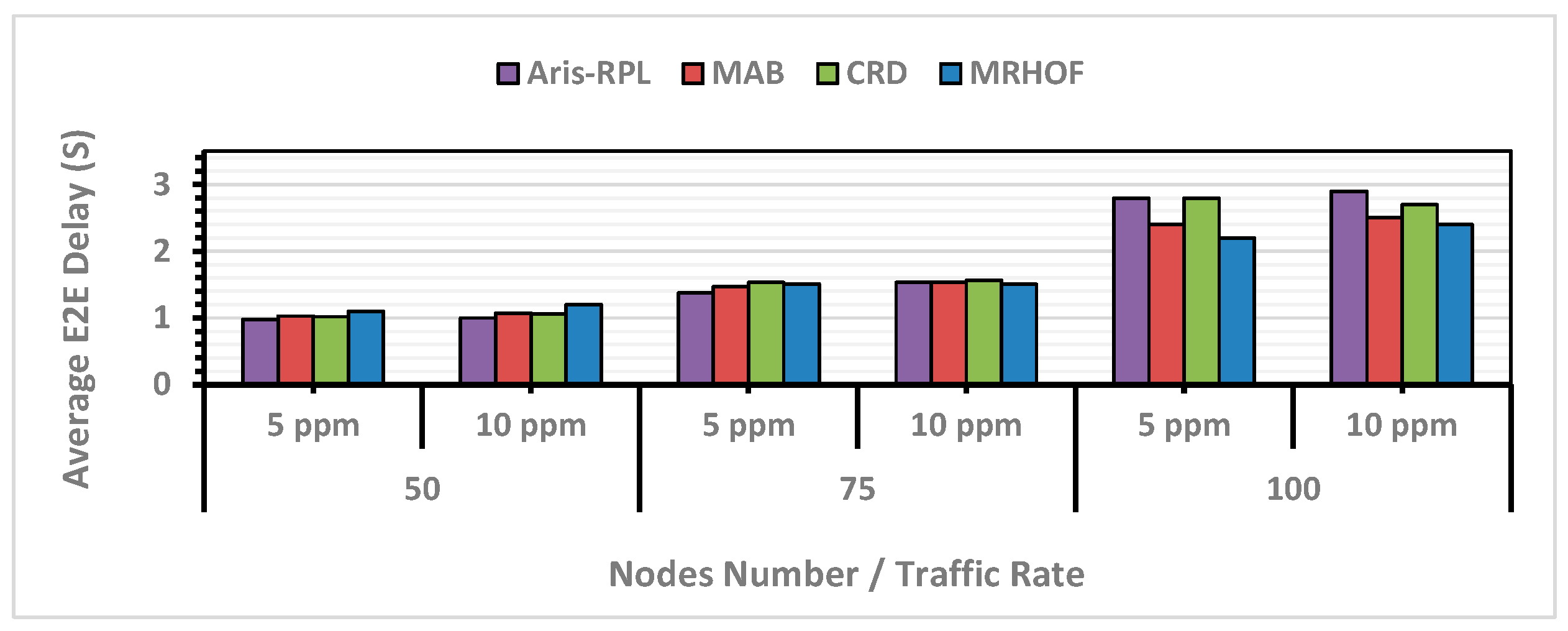

According to Figure 10, as network density and traffic load increase, the average delay for all approaches rises due to increased packet buffering and queuing time. In the first scenario, MRHOF showed a higher delay due to its continuous probing mechanism for good links and improper congestion and load balancing mechanisms. In contrast, MAB could decrease MRHOF’s delay through the intelligent learning method. However, the Aris-RPL and CRD showed similar end-to-end (E2E) delays, with the proposed method having a slightly lower delay. This trend continues in the second scenario, where the proposed method consistently demonstrates the lowest average E2E delay compared to the other approaches, and according to the second scenario results in Figure 10, the proposed method, on average, enhanced the delay compared to MRHOF, MAB, and CRD by 4%, 6%, and 6%, respectively.

Figure 10.

E2E Delay Results in Different Network Scenarios.

However, the proposed method started showing a higher E2E delay in the second scenario (75 nodes with 10 ppm) and continued in the third scenario. As previously explained, Aris-RPL is functionally designed to prioritize network reliability, congestion management, and load balancing. As a result, this is an intentional architectural trade-off designed to maximize the reliability in high-traffic scenarios. More specifically, by penalizing congested parents, the selection algorithm chooses nodes with additional hops, providing more stable routes at the expense of a marginal increase in delay. This observation aligns with the PDR results of the proposed method, as the total delay is directly related to the number of received packets. The exact observation for the CRD delay results, except for the PDR result, is less than that of the proposed method. More specifically, this design trade-off ensures that Aris-RPLs focus is primarily on congestion-aware and load-balancing routing, prioritizing PDR and load balancing over latency by actively avoiding congested nodes and selecting more stable paths in congested scenarios based on its metrics in the learning-based objective function.

5.5. Computational Complexity Analysis

Aris-RPL utilizes a single-row Q-table per node instead of a complete table. Each row corresponds to the node’s neighbors, minimizing memory requirements significantly for resource-constrained devices like the Z1 mote, which has 92 KB of flash memory ROM and 8 KB of RAM, even in dense networks. This approach ensures that nodes handle only the subset of neighbors relevant to routing decisions. However, the number of neighboring nodes directly affects the computational complexity of the proposed routing mechanism during the next-hop parent selection process. Each node updates its Q-values based on received DIO messages, evaluates neighboring nodes (as per Algorithms 1 and 2), and periodically monitors node conditions (as per Algorithm 3). The overall complexity of the proposed framework is O(n), where represents the number of neighbors. More specifically, when a node receives a DIO from a neighboring node, it updates the Q-value for that neighbor based on specific routing metrics. This is a local decision-making action performed at that moment. Moreover, if a node has n neighbors, each evaluation and Q-value update involves n operations, reflecting a linear scaling of computational cost relative to the node’s local environment size, rather than the overall network size. Moreover, Algorithm 3 monitors the node’s internal congestion metrics (buffer utilization and overflow ratio) with O(1) complexity.

Consequently, the overall complexity is O(n) because upon detecting congestion, the node must interact with its n neighbors by either broadcasting updates or re-evaluating the parent set to find a more stable path.

Therefore, this O(n) complexity ensures that the Z1 mote’s performance remains efficient, even in large networks (>100 nodes), without affecting the decision-making process, given that the number of immediate neighbors remains physically limited by radio range and the well-designed distribution of nodes inside the network layout. More specifically, the primary challenge in such scenarios is network control overhead, which our three-phase mechanism is designed to mitigate. However, assessing Aris-RPL performance in such large networks as future work is worth noting.

Considering RAM usage, as shown in Table 6, Aris-RPL introduces a 2.3% increase in ROM size. This is justified by the implementation of the Reinforcement Learning logic, the multi-objective reward function, and the non-linear penalty calculations. Even with this addition, the total firmware size (52 KB) is well below the 92 KB limit of the Z1. Also, Aris-RPL introduces a 0.5% increase in RAM size. The reason for Aris-RPLs low RAM overhead is that Aris-RPL maintains only a single row corresponding to the immediate neighbors, and when a DIO is received, the node processes the metrics immediately to calculate, update, and store the scalar Q-value for that neighbor.

Table 6.

ROM and RAM usage of all the Protocols.

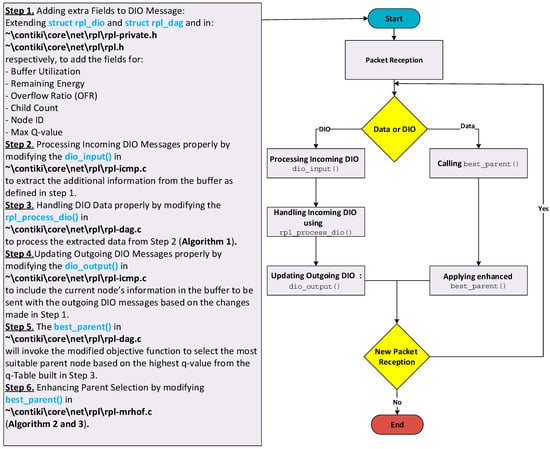

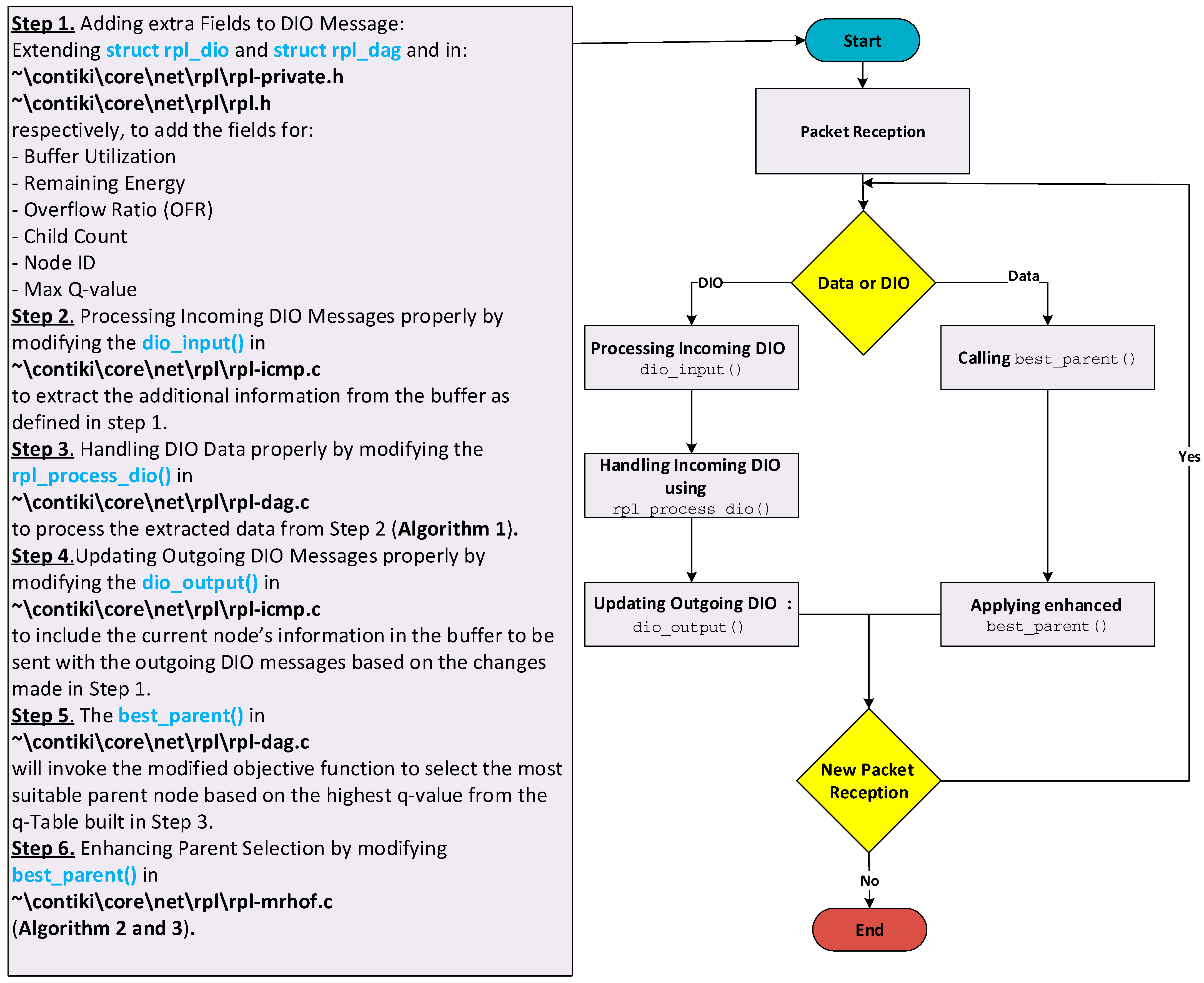

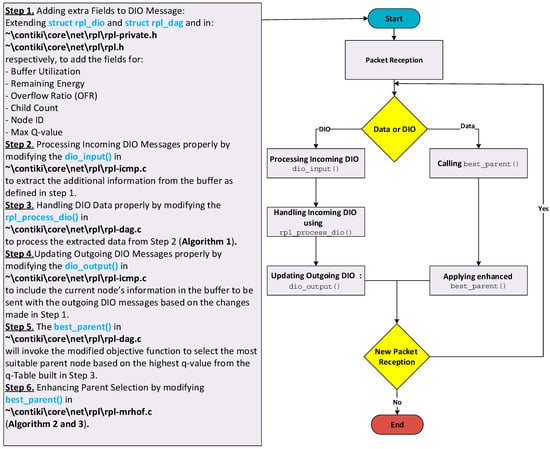

5.6. Protocol Implementation of Aris-RPL

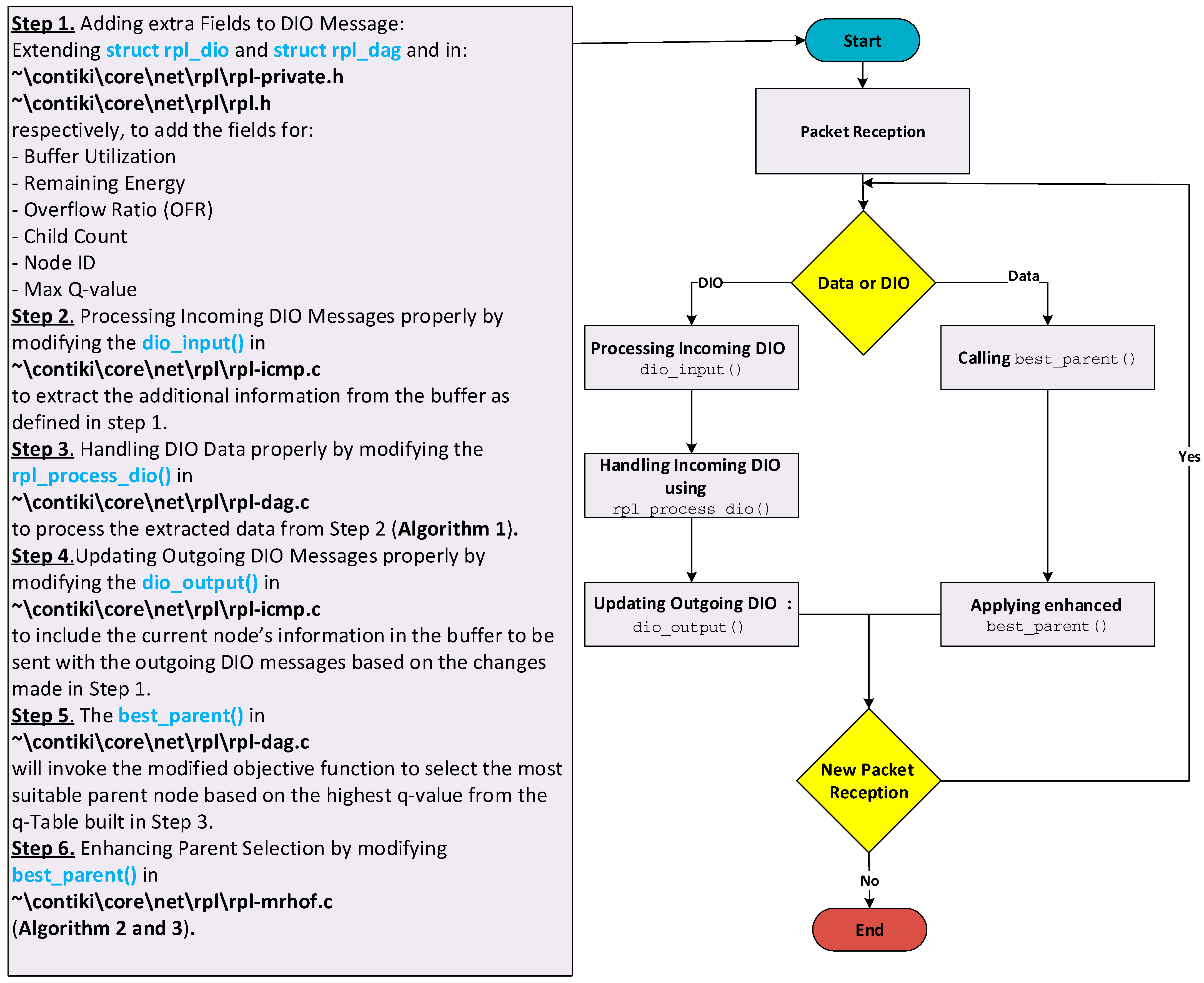

The implementation of Aris-RPL builds upon modifications to the ContikiRPL implementation in the Contiki OS. The proposed protocol integrates a Q-Learning-based framework, introducing an adaptive routing mechanism. To achieve this, the implementation involves key steps:

First, Aris-RPL extends the DIO message structure to include the additional metrics essential for routing decisions, including Buffer Utilization, Overflow Ratio, Child Count, Energy level, and Max Q-value. Aris-RPL adds a total of 8 bytes to the DIO payload to support its multi-objective learning, adhering properly to the 127-byte IEEE 802.15.4 MTU limit with no need for packet fragmentation. More specifically, the total length of the DIO message, considering the standard DIO compressed packet [18,60,61], is 49 bytes containing (17 bytes for header compression information, checksum fields, and ICMP type, 24 bytes related to RPL information including instance, rank, DODAG configuration, and route information, 8 bytes for the Aris-RPLs metrics). Second, upon reception of a DIO message, a modification needs to be made to extract and parse these additional metrics from the buffer. Third, the DIO process functions in ContikiRPL processes this information according to Algorithm 1.

Afterward, to continue disseminating node metrics throughout the network, a modification needs to be made to include the additional fields in outgoing DIO messages. This ensures that neighboring nodes receive real-time information about the network state, supporting dynamic decision-making. Following this, in routing decisions, RPL invokes the objective function that was modified according to Algorithms 2 and 3 to evaluate candidate parents based on the Q-values computed using Algorithm 1. Each node maintains a Q-table related to its neighboring nodes, which is updated iteratively based on rewards derived from received network metrics in the incoming DIOs. This enables nodes to refine their routing decisions over time, ensuring that routing decisions adapt to dynamic changes in traffic patterns and network topology.

The same coding logic was employed in both CRD and MAB implementations, each utilizing different metric compositions, reward functions, Q-value update functions, and additional optimization techniques to enhance performance further. For instance, the CRD approach uses Buffer Utilization, link quality, and hop distance metrics to calculate the reward and update the q-values, while MAB combines ETX with energy consumption in one metric called the EEX Metric to calculate the reward and update q-values. compared to the other methods used for comparison. Figure 11 outlines the required and detailed modification steps to the ContikiRPL implementation inside the InstantContiki 3.0 environment. These steps offer a clear pathway to reproduce the mechanism described in the paper.

5.7. Comparative Study

In this section, we provide a structured comparison between Aris-RPL and established baseline routing approaches. The comparison is based on the performance metrics obtained during our large-scale simulations (75–100 nodes) and is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

A comparative discussion of the key characteristics associated with the methods used for comparison.

Table 7.

A comparative discussion of the key characteristics associated with the methods used for comparison.

| Characteristic | RPL-MRHOF | CRD | MAB | Aris-RPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Function Criteria | The standardized RPL objective function with a focus on minimizing ETX | Multi-metric Q-learning-based optimal parent selection to address congestion and load-balancing in dynamic networks | Multi-armed bandit-based adaptive parent selection in dynamic networks with a focus on energy efficiency | Three-phase Q-learning framework with an effective hybrid monitoring mechanism. Using a composite reward metric. |