Abstract

Reliable data availability and transparent governance are fundamental requirements for distributed edge-to-cloud systems that must operate across multiple administrative domains. Conventional cloud-centric architectures centralize control and storage, creating bottlenecks and limiting autonomous collaboration at the network edge. This paper introduces a decentralized governance and service-management framework that leverages Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) and Decentralized Applications (DApps) to to govern and orchestrate verifiable, tamper-resistant, and continuously accessible data exchange between heterogeneous edge and cloud components. By embedding blockchain-based smart contracts within swarm-enabled edge infrastructures, the approach enables automated decision-making, auditable coordination, and fault-tolerant data sharing without relying on trusted intermediaries. The proposed OASEES framework demonstrates how DAO-driven orchestration can enhance data availability and accountability in real-world scenarios, including energy grid balancing, structural safety monitoring, and predictive maintenance of wind turbines. Results highlight that decentralized governance mechanisms enhance transparency, resilience, and trust, offering a scalable foundation for next-generation edge-to-cloud data ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Data availability is critical for stakeholders who rely on accurate, real-time data to make their decisions and maintain trust in the system. This timely, reliable access to data is essential for operational efficiency and for ensuring participant transparency and accountability. Moreover, information sharing is crucial for maintaining and executing various use cases, particularly when multiple stakeholders collaborate to achieve business or daily objectives. One challenging aspect of large-scale stakeholder collaboration is the decision-making process that governs processes and events. In addition, long-term collaboration requires trust and transparency in all decisions made by the communities managing such processes.

Data availability depends heavily on the software system architecture, data governance, and sharing aspects. Many information computing systems process data within a single computer system with extensive architectural capacities in memory, processors, and storage. Decisions regarding protection levels and authorized access typically fall within the system administrator’s responsibility [1,2]. Currently, the most powerful data processing is centralized, primarily situated in the cloud [3]. This approach can bring significant benefits. It enables on-demand scaling and efficient resource allocation. Further, it reduces costs by eliminating the need for additional hardware, improves data security, and ensures that data and programs on each information system remain independent, thereby increasing security and trust [4]. At the same time, cloud hosting ensures the accessibility of applications and websites using dedicated cloud resources [5].

However, despite their widespread use, centralized processing and cloud-based infrastructures fundamentally limit how services and applications operate, as they depend on large single entities for authentication, storage, processing, and connectivity, and often enforce vendor-locked development and orchestration environments [6,7,8,9,10,11]. This substantially reduces users’ ability to govern their own data, limits their visibility into who holds access rights, and hinders the implementation of controls needed to prevent inappropriate or risky access [12,13].

An alternative approach to addressing data availability and collaborative decision-making challenges involves using blockchain and smart contracts. They offer a new way of managing decentralized services and ensure that data remains accessible, secure, and verifiable across the network [12,13]. Integrating decentralized governance and decentralized applications via Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) enables tamper-proof services and process management. Furthermore, the combination of on-chain and off-chain data enabled by oracles ensures comprehensive data availability for decision-making. This ensures that external or real-world data can be securely integrated into the decentralized system, thereby improving the reliability and performance of decentralized services [12,14].

This article investigates the potential of DAO-governed smart contracts and oracle-based data acquisition to support reliable data flows and availability. The proposed governance paradigm formalizes the policies, processes, standards, metrics, and stakeholder roles necessary for effective data utilization and for achieving organizational objectives [12].

It establishes responsibilities and processes that ensure the quality and security of the data used. We will focus on swarm-based use cases, which are good examples of collaborative systems that exchange data and make collective decisions. These use cases include a swarm of drones synchronized for mast inspection (5G antennas), a swarm of sensors to monitor the structural safety of infrastructures and buildings, and a swarm of sensors to support windmill maintenance.

While earlier OASEES publications introduced the project vision and individual enabling technologies, this work goes beyond them by formalizing DAO-driven governance as an operational service layer and by validating its impact on data availability and decision-making across multiple real-world edge-swarm use cases.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the key concepts of edge computing and swarm-based coordination. Section 3 defines the problem of information unavailability in edge and swarm environments. Section 4 reviews related work in decentralized systems, data availability, and swarm intelligence. Section 5 presents the OASEES concept as a DAO-as-a-service framework and outlines its high-level architecture. Section 6 details how DAOs and DApps support secure data sharing across three use cases and reports experimental results, including smart contract performance. Section 7 describes the OASEES implementation, SDK stack, and deployment across core and edge resources. Section 8 offers a cross-cutting evaluation of the DAO–DApp swarm architecture. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper and highlights future research directions.

2. Background: Edge-Swarm Computing and the Information Sharing

This section provides an overview of the evolution from centralized cloud infrastructure to distributed and cooperative paradigms, such as edge and swarm computing. It outlines how the convergence of these models supports intelligent, scalable, and adaptive information processing across heterogeneous environments.

2.1. From Cloud to Edge-Swarm Computing

Cloud Computing presents a computing paradigm that consists of a set of resources and services offered through the Internet [15]. The Cloud Computing model enables ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) [16].

Edge Computing is a new distributed computing paradigm enabling computation and data storage closer to the data sources, i.e., near happening, such as for IoT devices or local edge servers. The core advantages of edge computing are exploiting such proximity to reduce latency, conserve bandwidth, and enhance real-time data processing capabilities. Such technological characteristics offer many advantages, including enhanced security. Exploiting local processing capabilities enables risk mitigation when transmitting sensitive data over networks [17,18]. Swarm Computing is a distributed computing model inspired by the collective behavior of natural swarms, such as bees, ants, or birds. In such a model, many agents work together in a decentralized, autonomous way to achieve a common goal. This is achieved by sharing information and making collective decisions, resulting in emergent intelligence that exceeds the sum of individual capabilities [19]. Swarm Computing is characterized by: (i) decentralization, where the decisions are made collectively rather than via single-point of control; (ii) self-organization, allowing agents to organize themselves based on the local and timely environment; (iii) adaptability, allowing agents (and systems) to responds dynamic changes in the environment; (iv) scalability that allows adding new agents following system needs, and (v) robustness where swarm-based system allows failure of certain number of agent and still perform the common task [19,20].

Swarm intelligence powers computing systems by providing various concepts that are further computerized. Such concepts are related to data processing and aggregation by many agents simultaneously. Further, via the decision-making, the intelligence process is performed by agents who share observations and converge on optimal solutions through consensus. Additionally, swarm intelligence is implemented, i.e., computerized via learning processes, where agents exploit feedback loops to enable the system to improve and adapt over time [19,20,21].

In summary, the evolution from cloud to edge and swarm computing marks a shift from centralized resource provisioning toward decentralized, intelligent collaboration among distributed entities. This transition not only enhances computational efficiency and scalability but also enables new paradigms of information sharing. Data and intelligence are processed more closely to their sources. The following section explores components of the distributed architectures that facilitate secure and adaptive information exchange across interconnected systems.

2.2. Decentralized Technology Components for Enhancing Information Sharing and Security

Blockchain maintains a distributed, decentralized shared ledger that enables secure transaction exchange. The network of BC nodes follows a peer-to-peer communication protocol, and the involved nodes maintain an exact copy of the ledger. The transaction data is governed by a consensus protocol that ensures user trust in the system’s reliability. Transactions are stored in blocks, which are subsequently chained. Chaining is a fundamental characteristic of blockchain, which supports the properties of immutability and integrity of data stored on the blockchain, as well as non-repudiation of the act of storing the data by any party [22].

Smart contracts are code that runs on the blockchain. All nodes contributing to the blockchain can prove that the outcome of an innovative contract execution is correct because all data and events used to execute the smart contract code are transparent to all nodes.

A Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) represents the concepts of an organization that operates on a blockchain. A DAO is completely controlled or governed by smart contracts. It is designed to be autonomous and decentralized, with decision-making processes and operations carried out through consensus mechanisms among its participants [23].

A Decentralized Application (DApp) is a type of software that operates on a blockchain in a peer-to-peer manner. Unlike traditional applications that rely on a single central server, the back-end of a DApp runs across multiple blockchain nodes, enhancing transparency, security, and censorship resistance [24].

Decentralized Storage refers to storing data across multiple nodes in a distributed network rather than relying on a single central server. This approach enhances data availability, resilience, and security, as no single point of failure can compromise the system. One widely adopted protocol for decentralized storage is the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS; https://ipfs.tech/ (accessed on 4 January 2026)), which allows files to be stored and retrieved using a content-addressed system. In IPFS, each file is assigned a unique cryptographic hash, ensuring immutability and verifiable integrity, while the network enables efficient peer-to-peer data sharing.

4. Related Works Studies, and Scientific Contributions

This section covers related studies on swarm computing and decentralized technologies in the context of varying data availability for swarm-edge systems. Furthermore, we present a scientific contribution that serves as a synthesis of progress beyond the state of the art.

4.1. Related Studies

Data availability is a critical requirement for ensuring the proper functioning and execution of intended operations within a system. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and blockchain systems are no exception, as they also rely on data availability to maintain functionality. This ensures that all transactional data within associated systems remains accessible to relevant participants, thereby supporting consistent system performance and facilitating data verification.

In swarm-edge computing, where distributed nodes must autonomously coordinate, data availability and decentralized decision-making are particularly vital, as they enable real-time responsiveness, fault tolerance, and scalable collaboration among edge devices [35]. Swarm computing leverages the collective intelligence of distributed nodes to allow scalable, resilient operations. Recent studies have increasingly focused on integrating blockchain and distributed ledger technologies to enhance trust, traceability, and auditability within such systems.

For instance, Strobel et al. [36] demonstrate how blockchain-based consensus protocols can secure robot swarms against Byzantine behavior, ensuring transparent, tamper-resistant coordination. Their work establishes that even in adversarial conditions where up to 33% of agents may be compromised, blockchain-anchored voting mechanisms maintain swarm integrity. Similarly, Pacheco et al. [37] employ smart contracts for real-time swarm coordination, demonstrating how decentralized ledgers can automate decision-making and improve system robustness through experimental validation of foraging tasks. Tran et al. [38] introduce SwarmDAG, a partition-tolerant distributed ledger protocol designed for swarm networks that effectively addresses the limitations of traditional blockchains under intermittent connectivity. By employing a directed acyclic graph structure rather than linear chains, SwarmDAG achieves higher throughput and lower latency in network-partitioned environments, a critical requirement for mobile swarm robotics. Extending to other domains, Ibrahim et al. [39] apply blockchain mechanisms to nanosatellite swarms, achieving higher reliability and data integrity across distributed systems operating in resource-constrained space environments.

From a scalability perspective, Bulgakov et al. [40] and Wu et al. [41] evaluate sharding-based mechanisms that partition blockchain data to reduce latency and improve throughput, which are essential for large-scale swarm-edge infrastructures. Bulgakov’s analysis demonstrates that horizontal sharding can increase transaction throughput by up to 64x in controlled environments, though at the cost of increased cross-shard communication complexity. Wu’s protocol introduces dynamic shard reconfiguration based on transaction patterns, showing particular promise for heterogeneous swarm systems with uneven workload distribution. Complementary approaches also leverage token economies and distributed trust models to neutralize malicious entities and maintain system integrity [42]. Strobel et al. demonstrate that economic incentive mechanisms can effectively discourage Byzantine behavior by making attacks financially non-viable, even without perfect knowledge of agent identities. These advances illustrate how decentralized coordination can mitigate the issues of central dependency, limited transparency, and probabilistic synchronization observed in conventional, centralized, or agenda-based coordination schemes.

The integration of blockchain with edge intelligence has gained attention for enabling secure distributed learning. Li et al. [43] propose blockchain-based frameworks for federated learning that address privacy preservation and model poisoning attacks through cryptographic verification of model updates. Their approach demonstrates that distributed trust mechanisms can reduce attack success rates by over 80% while maintaining acceptable training convergence, a critical consideration for swarm systems that must learn and adapt collectively. Building on this, Nguyen et al. [44] investigate hybrid storage architectures for edge-cloud systems, proposing tiered models where frequently accessed data is cached at edge nodes, intermediate data is stored in IPFS with blockchain anchoring, and archival data resides in incentivized storage networks. Their evaluation shows that such architectures can reduce data retrieval latency by 73% compared to pure blockchain storage while maintaining cryptographic verification, directly addressing the data availability challenges inherent in swarm-edge computing.

The governance dimension of decentralized systems has been examined through DAO frameworks. Wang et al. [23] provide a comprehensive taxonomy that distinguishes among token-weighted, reputation-based, and hybrid governance models, suggesting that reputation-based mechanisms may offer advantages for swarm systems that require rapid adaptation. Beck et al. [45] extend this analysis by examining hybrid human-machine voting protocols and find that human oversight in critical decision paths can increase system reliability by 34% without significantly impacting response times. However, applying DAO principles to cyber-physical systems spanning multiple domains, such as energy management, structural monitoring, and predictive maintenance, remains relatively underexplored in the literature. More recent research has further examined decentralized autonomous organizations as governance mechanisms for complex socio-technical and cyber-physical systems. Lustenberger [46] provides an up-to-date synthesis of DAO research trends, identifying key challenges related to governance scalability, participation incentives, and integration with real-world systems. Complementing this perspective, Bonnet [47] presents a systematic literature review of DAO research, highlighting governance automation, accountability, and coordination as dominant themes, and notes the limited number of studies addressing operational cyber-physical deployments.

Beyond purely digital ecosystems, Ly and Shojaei [48] investigate the application of DAOs in built and infrastructure environments, demonstrating the potential of decentralized governance for managing physical assets while emphasizing unresolved challenges related to latency, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder heterogeneity. In parallel, broader surveys on blockchain-enabled decentralized intelligence [49] highlight the convergence of governance mechanisms, edge intelligence, and autonomous system coordination, reinforcing the relevance of DAO-based approaches for next-generation cyber-physical and swarm-edge systems. However, these works generally focus on single-domain scenarios or conceptual governance models and do not explicitly address cross-domain data availability, SSI-based access control, or integrated DAO–DApp orchestration as proposed in OASEES.

Security considerations in blockchain-enabled swarms present unique challenges. Ferrag et al. [50] conduct a comprehensive survey identifying oracle manipulation, smart contract vulnerabilities, and consensus attacks as primary threat vectors in IoT and edge environments. They propose multilayered defense strategies combining formal verification, secure oracle protocols, and edge-layer anomaly detection. In the context of swarm robotics specifically, Dorigo et al. [51] examine trade-offs between decentralization and security, demonstrating that purely distributed consensus without trusted components may be vulnerable to eclipse attacks in sparse network topologies. These findings underscore the need for hybrid architectures that balance trustlessness with practical security requirements.

Data storage solutions for decentralized systems have evolved beyond simple blockchain anchoring. Benet [52] introduces IPFS as a content-addressed, peer-to-peer protocol that has become foundational for decentralized storage. However, IPFS alone does not guarantee persistence, leading to complementary solutions such as Filecoin [53], which adds economic incentives for long-term data availability. For real-time swarm applications, these storage paradigms must be adapted to support both the immutability requirements of governance decisions and the ephemeral nature of sensor streams.

At a broader architectural level, recent surveys highlight the convergence of blockchain, edge computing, and AI for building trustworthy, low-latency, and autonomous distributed systems [54,55,56]. Collectively, these works reinforce the paradigm shift toward secure, transparent, and adaptive swarm-edge infrastructures, where decentralized ledgers not only record transactions but also facilitate coordination, governance, and fault resilience across heterogeneous and dynamic environments.

Recent work has explored blockchain-enabled security and scalability mechanisms in edge-cloud and cyber–physical environments. Khodjamov et al. [57] propose a blockchain-based trusted clustering framework for multi-tier Social IoT systems, focusing on secure inter-cluster communication and trust establishment across edge and cloud layers. While effective for hierarchical IoT security, their approach remains protocol-centric and does not address decentralized governance, identity sovereignty, or multi-stakeholder coordination.

Similarly, Li et al. [58] introduce AssociateChain, a scalable blockchain architecture for cloud–edge systems based on associative sharding, primarily targeting throughput and data consistency in large-scale deployments. However, this work focuses on infrastructure-level scalability rather than governance-as-a-service, policy-driven access control, or Human-in-the-Loop decision-making, which are central to OASEES.

4.2. Comparative Analysis and Research Positioning

Existing blockchain-based swarm and edge computing approaches share common goals with OASEES, including decentralization, trust establishment, and fault tolerance. However, most prior work focuses on coordination or consensus among agents (e.g., blockchain- secured voting or task allocation), treating governance, data availability, and access control as secondary concerns. In contrast, OASEES explicitly elevates governance to a first-class service through DAO-as-a-Service, integrating identity (SSI), data access policies, and execution logic within a unified framework.

Moreover, while several studies validate their approaches in simulations or single-domain scenarios, OASEES demonstrates cross-domain applicability through multiple real-world use cases, highlighting both strengths (auditability, stakeholder accountability, flexible onboarding) and limitations (latency overheads and reliance on permissioned participation). This positioning allows OASEES to address practical governance and data-availability challenges that are insufficiently covered by existing swarm-edge solutions. Table 1, highlighting similarities, differences, advantages, and limitations of the proposed approach with respect to representative related works.

Table 1.

Comparison with Representative Related Works.

Despite these advances, several critical gaps remain (summarized in Table 1). In contrast to previous OASEES-related studies that primarily focused on architectural concepts or isolated blockchain components, this paper provides an integrated DAO–DApp–SSI framework and a cross-domain empirical evaluation, thereby extending the state of the art from conceptual design to operational governance in edge-swarm systems.

First, while existing work demonstrates blockchain-based coordination for small-to-medium swarms (typically fewer than 100 agents), governance mechanisms for large-scale deployments exceeding 1000 agents remain underexplored, particularly with respect to voting efficiency, proposal management, and spam prevention. Second, most blockchain-enabled swarm studies focus on scenarios where sub-second response times are not critical. In contrast, applications such as structural safety monitoring or energy grid balancing require near-instantaneous coordination, creating inherent tension between blockchain consensus latency and operational requirements. Third, the seamless integration of human decision-makers into DAO-governed swarms while preserving decentralization properties has received limited attention—existing Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) approaches often reintroduce central control points or operational bottlenecks. Fourth, most studies focus on homogeneous swarms rather than heterogeneous, multi-stakeholder environments with fundamentally different governance, incentive, and data-sharing requirements. Finally, real-world validations of DAO-based swarm governance across multiple application domains remain scarce, with most existing work limited to simulations or single-domain pilots.

By addressing these gaps, this work advances the state-of-the-art through: (1) demonstrating DAO-governed coordination across heterogeneous, multi-domain swarm-edge systems spanning energy, infrastructure, and industrial applications; (2) integrating SSI-based access control with blockchain governance to enable trustless authentication without central authorities; (3) providing empirical insights into scalability and performance trade-offs through parallel validation across multiple real-world use cases and (4) establishing a replicable architectural framework for decentralized edge-cloud data ecosystems that balances the immutability requirements of governance with the real-time demands of swarm coordination.

5. OASEES: The DAO as a Service for Decentralized Edge-Cloud Use Cases

In this section, we discuss the OASEES project and how its framework addresses the problems and challenges presented in Section 3. We present project use cases built on that framework.

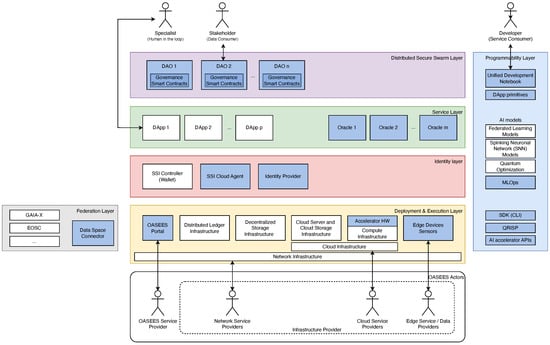

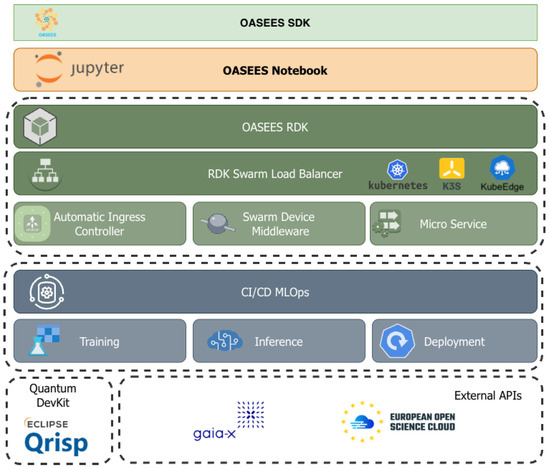

The OASEES project (OASEES: Open autonomous programmable cloud apps & smart sensors; https://oasees-project.eu/ (accessed on 4 January 2026)) introduces a decentralized and swarm intelligence-based computing framework built on Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) (see Figure 1 on the following page) [12,14]. The foundational elements of DLT enable trustworthy data exchange and collaboration, fostering transparency and trust by creating an auditable trail. This system ensures that every participant within the swarm agrees on the state of the data in the ledger, leading to consensus.

Figure 1.

OASEES high-level architecture.

OASEES deploys Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) to inherent trust within swarms, where an OASEES swarm organizes its operations and intelligence via a DAO. Each device within the swarm can participate in the DAO, voting automatically on decision-making based on different parameters and conditions. This self-governance model, in conjunction with the cloud-native approach of OASEES, forms a flexible, agile framework for swarm architectures.

Swarm collaboration within OASEES is a robust process that brings together a collective of edge devices and human experts. It leverages decentralized technology for involvement, synchronization, and oversight. A significant aspect of this process is the execution of collaboration within the Gaia-X (Gaia-X: Federated Secure Data Infrastructure; https://gaia-x.eu/ (accessed on 4 January 2026)) data federation, which enhances data sharing, interoperability, and sovereign data services. It enables federated learning by coupling DAO with Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) mechanisms across disparate edge devices.

These technological components offer several benefits: Participants can interact with the DAO through digital wallets, which allow them to stake tokens, vote on proposals, and receive rewards. The DAO paradigm’s underlying automation works in harmony with human intelligence, driving toward the fulfillment of intricate objectives and the resolution of complex challenges.

In line with its decentralized architecture, data will remain distributed across multiple databases while providing a unified view of data access. Data federation enables data integration across different data sources or edge devices without requiring physical data consolidation. The data will remain under the control of the respective source, maintaining data ownership and security. It will improve scalability, as new data sources can be added/removed in real time, minimizing data movement and reducing latency. In this context, OASEES serves as a “First-Level Data Space” because it operates very close to where the data is generated. Here, the data can be correlated, stored, and integrated.

5.1. OASEES High-Level Architecture

The OASEES high-level architecture involves various actors and components that interact across different layers. Figure 1 highlights these components and their positions inside one of the following layers. The blue boxes represent the OASEES core components.

The entire framework is built on top of a Deployment and Execution Layer. This layer includes different types of infrastructure with related management elements, such as network and cloud infrastructure, distributed ledger and decentralized storage infrastructures, and cloud server and cloud storage infrastructures. The data from the physical edge devices, including their sensors, might be processed in the compute infrastructure, which may use accelerator hardware to offload CPU-intensive calculations. Finally, it includes the OASEES portal, which serves as the central access point for provisioning swarm services.

The (Data) Federation Layer in OASEES enables seamless operation in multi-instance configurations within federation frameworks for cloud services and data spaces. OASEES aligns with Gaia-X concepts to connect infrastructure and data ecosystems, promoting compliance, federation, and data exchange. It acts as both an infrastructure service provider and a data provider, leveraging innovative edge-aware brokerage to facilitate collaboration and resource sharing. By registering its resources and services in the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) (EOCS: European Open Science Cloud; https://open-science-cloud.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 4 January 2026)) ecosystem, OASEES becomes a provider within EOSC, thus offering various services and adding value through monitoring and helpdesk support.

The Identity Layer integrates Self Sovereign Identity technology, enabling the creation of portable digital identities based on Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs). DIDs provide control over digital identity without relying on centralized intermediaries, while VCs offer tamper-evident credentials with enhanced trustworthiness. This layer consists of the SSI controller, which enables secure authentication to the OASEES portal; the SSI cloud agent, which stores and fetches certificates and DIDs in the distributed ledger; and the identity provider, which enables secure interactions and the identification of DAO participants.

The Service Layer provides the components for building and deploying Decentralized Applications (DApps). DApps are composed of micro-services and smart contracts. The former are based on (traditional) cloud and edge infrastructure and associated services, the latter are based on smart contracts registered in a decentralized ledger. To bridge the gap between these two worlds, the service layer also involves oracles to enable interaction between smart contracts and the external world.

The Distributed Secure Swarm Layer focuses on the key OASEES concept of the DAO as a framework for regulating interactions among multiple parties, including humans and/or swarms of devices. The DAO is implemented as a set of smart contracts and includes Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) mechanisms that facilitate resource management, incentives, and decision-making for swarm collaboration. It includes Governance Smart Contracts that handle all smart contract logic for managing, collecting, and following up on proposal generation and voting. Users interact with the DAO through digital wallets, token staking, voting on proposals, and receiving incentives.

The Programmability Layer of the OASEES architecture provides the necessary tools and interfaces for developing, deploying, and managing decentralized applications (DApps) and DAOs on the Cloud-Edge continuum. It encompasses the OASEES SDK, which includes the CLI and DApp primitives for developing and deploying decentralized applications across the Cloud-Edge continuum. The unified development notebook serves as the central focal point for developing DAOs, smart contracts, and DApps. MLOps is a set of practices and tools designed to streamline the deployment, monitoring, and continuous improvement of machine learning models in production environments, and it supports several AI models, as well as external APIs. Additionally, the Eclipse QRISP quantum development kit is envisaged for deployment within DApps accessible through the OASEES portal.

5.2. Actors

Multiple stakeholders have roles in the OASEES paradigm. Each stakeholder plays a crucial role in the operation and management of OASEES services, ranging from infrastructure (cloud) management to service design, consumption, and provision.

An Infrastructure Provider provides devices and associated control/orchestration framework managing the devices to be used by OASEES to build services on top of them. We distinguish between Cloud Service Providers, Edge Service Providers (or, more general, Data Providers) and Network Service Providers.

Cloud Service Providers are responsible for managing and maintaining the cloud infrastructure, such as the cloud servers, cloud storage, and cloud networking equipment. They are responsible for ensuring that the cloud infrastructure is secure, reliable and performant, and they provide the tools and APIs that developers need to build and deploy applications on the cloud. Cloud Service Providers may also provide additional compute infrastructure, such as data processing, and machine learning, including accelerator hardware, that developers can use to build more advanced applications.

Sensors or data-generating devices (e.g., drones), such as those used to monitor wind turbines, may be owned by various parties, referred to as Edge Service Providers or Data Providers, depending on the context and application. In some cases, the equipment manufacturers may provide sensors as part of their products or offer them as optional additional features.

Network Service Providers provide the underlying network infrastructure to which Cloud Service Providers and Edge Services Providers connect. They are responsible for ensuring that the network is secure, reliable, and performant, managing the underlying network infrastructure, including the edge computing devices, routers, and switches. Network Service Providers also provide the necessary Distributed Ledger and the Decentralized Storage Infrastructure (e.g., IPFS).

Specialists (e.g., doctors) might act upon data as produced by the OASEES services or interact with OASEES DApps to make decisions as part of or interacting with a smart contract. This enables Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) interaction as envisioned in the project framework.

Developers act as Service Consumers and develop OASEES services and/or DApps. The former refers to the design of pure data processing (e.g., AI models for vision based on generated data) functionality; the latter refers to the design of smart contracts in the context of DApps deployed for a DAO. OASEES developers are individuals or groups who design and deploy DApps on top of the DAO platform and components provided by Cloud Service Providers, Edge Service Providers, equipment vendors, and governmental agencies.

Data Consumers or OASEES users are Stakeholders who use the outputs of OASEES services or DApps. Users can be patients who interact with a service providing them assistance.

Last, but not least, the OASEES Service Provider, also referred as the OASEES Swarm Operator, manages the OASEES portal, interacting with the infrastructure of different providers to provide OASEES DApps on top of DAOs to the Data Consumers.

6. Leveraging DAOs and DApp for Secure Data Sharing and Availability

The integration of DAOs and DApps within the OASEES architecture aims to fundamentally transform secure data sharing and availability in edge-swarm systems by replacing centralized control with cryptographically enforced governance protocols. Unlike conventional approaches that rely on a trusted intermediary, OASEES introduces decentralized decision-making, automated policy execution, and blockchain-based auditability. This ensures that multiple stakeholders with potentially competing interests can collaborate without depending on mutual trust, while maintaining resilience against manipulation or unilateral control. Furthermore, relying on well-defined, transparent rules enables broader business opportunities for data consumers seeking to train AI/ML models.

Building on the architectural foundations presented in Section 5, this section examines how real-life use cases demonstrate practical implementations of DAO-governed data sharing. The proposed design shows how DAO governance enforces access control and trust mechanisms, while DApps serve as the functional layer that operationalizes business logic by invoking smart contracts and linking governance proposals to real-world activities.

OASESS has executed this exercise on six use cases (UC):

- UC Energy Grid: Support of optimal operation of the electricity grid via coordinated recharging of fleets of electric vehicles

- UC Structural Safety: Structural safety assessment of buildings and critical infrastructure

- UC Windmill Maintenance: Predictive maintenance of windmills

- UC Antenna Inspection: Drone-based hight mast inspection of 5G antennas

- UC Smart Manufacturing: Collaborative robotic powered smart manufacturing

- UC Parkinson: Analysis of voice, articulation, and fluency disorders in Parkinson’s Disease

In this way, OASEES provides an integrated framework that can be coordinated through swarm intelligence mechanisms. Furthermore, by combining blockchain anchoring, distributed storage solutions such as IPFS, and DAO-based access governance, OASEES ensures that swarm-collected data remains verifiable, queryable, and resilient to both technical failures and organizational biases. This architecture directly addresses the fundamental challenge of data unavailability in edge-swarm computing, replacing centralized bottlenecks with decentralized, auditable, and adaptive governance.

The following subsections present detailed use-case demonstrations that illustrate how DAO and DApp coordination enforce secure data availability while supporting swarm intelligence across diverse domains. We focus only on the use cases Energy Grid, Structural Safety, and Windmill Inspection, because they are generic enough to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed architecture.

6.1. UC Energy Grid: Support of Optimal Operation of Electricity Grid via Coordinated Recharging of Fleets of Electric Vehicles

With the increasing number of distributed intermittent renewable power plants, i.e., photovoltaic systems, and a rising demand for energy due to the transition to electric mobility, significant congestion is occurring in some energy grids worldwide. This happens because the demand for energy to charge cars, which is high at night, is not synchronized with the photovoltaic systems’ production during the daytime, particularly at noon. In some cases, this results in a surplus of power that the typical energy customers and households do not consume. This produces Reverse Power Flows (PRFs) through the substations of the low-voltage distribution network, for which many electricity grids are not designed. This might lead to significant problems, such as voltage rise, frequency imbalance, and equipment tripping. Leveraging energy flexibility services would help stabilize the network and limit the effort required to modernize the power grid.

The use case aims to integrate photovoltaic power generation and electric-vehicle energy consumption during periods of power surplus by incentivizing vehicle owners to charge their vehicles at specific times.

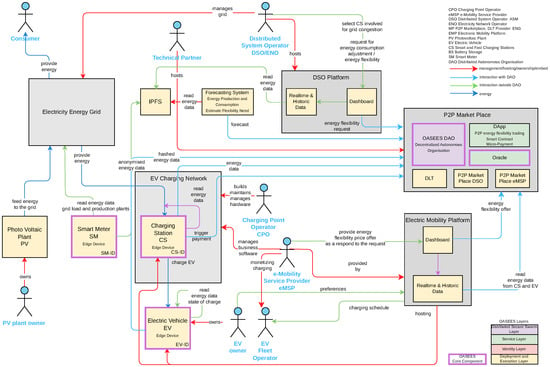

The overview diagram in Figure 2 shows several participants and their relationships. Table 2 on the following page lists the main actors, the involved systems, and new platforms or systems developed based on OASEES, as well as the essential data structures.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the energy grid-electric vehicles use case.

Table 2.

Main actors, systems and components of the energy-grid use case.

At the center of the use case is the P2P Marketplace, which facilitates energy trading between producers and consumers. This marketplace builds on DAOs and DApp to align charging availability with requests from energy providers for flexibility. The other relevant platforms are the Distributed System Operator Platform of energy providers, the Electric Mobility Platform for Charging Point Operators, and the Electric Vehicle Owners Platform. Both platforms hide the P2P Marketplace from the users.

6.1.1. DAO Activities and Proposals

In this use case the DAO acts as a swarm intelligence mechanism, coordinating distributed decision-making across heterogeneous actors, such as Distributed System Operator (DSO), Electricity Network Operator (ENO), Charging Point Operator (CPO), e-Mobility Service Provider (eMSP), and Electronic Vehicles (EV) owners or fleet operators, through a transparent proposal and voting process. It also manages complex multi-party interactions among stakeholders through programmable governance rules for energy grid optimization. By encapsulating operational decisions into DAO proposals and binding their execution to smart contracts and decentralized applications (DApps), the Energy Grid UC ensures adaptive, self-organized, and trustless governance of critical energy and mobility functions. Further, it calculates optimal pricing via embedded auction mechanisms and executes energy-trading smart contracts without manual intervention. In the Energy Grid use case, each governance proposal references a predefined smart contract function. After reaching quorum and majority approval, the DAO automatically executes the corresponding contract, which updates on-chain governance state (e.g., access control lists or device registries) and emits execution events. These events are consumed by DApps and oracle services, which enforce the decision at the application and data layers, such as enabling or revoking access to IPFS-hosted datasets or activating device-specific data feeds. This design ensures that approved access rules are enforced consistently without manual intervention.

The DAO manages complex coordination activities within the UC through the submission of proposals. In the following, we present the Energy Grid UC activities:

- Market and pricing regulation:

- –

- Proposals to set or update electricity prices offered by the DSO.

- –

- Proposals to determine the CPO selling prices, including specification of payment timing and conditional settlement rules.

- –

- Proposals to automatically adopt the lowest available selling price for efficiency and fairness.

- Infrastructure management:

- –

- Onboarding of new edge devices (e.g., Smart Meters, Charging Station (CS) units), validated by the relevant authority.

- –

- Removal of malfunctioning or compromised edge devices.

- –

- Addition or removal of organizations participating in the network.

- Incentive and economic models:

- –

- Proposals to define or update incentive mechanisms for participating members, executed through a treasury smart contract.

- –

- Proposals to initiate micro-payments between stakeholders to support dynamic energy exchanges.

- Data governance and access control:

- –

- Proposals for data-sharing rules, specifying update, removal, or addition of data governance policies.

- –

- Proposals for access control and data management, including specification of which datasets (e.g., smart meter readings, Electric Vehicle (EV) telemetry, charging schedules) can be accessed by which actor.

Voting on onboarding and configuration proposals is limited to relevant stakeholders (e.g., DSO, CPO, and eMSP) whose operational or economic outcomes are directly affected by such decisions. Participation is therefore incentivized by the need to preserve grid stability, prevent the inclusion of misconfigured or malicious devices, and ensure correct revenue allocation, rather than by speculative token rewards. For routine operational decisions, voting may be delegated or automated based on predefined compliance and validation rules, whereas critical actions may trigger a Human-in-the-Loop review.

6.1.2. Interaction Schema

The interaction of the DAO with the broader smart contract stack and system components. The process begins with identification, during which DSO, CPO, eMSP, CS, and users are authenticated via the OASEES Identity Layer using decentralized identifiers (DIDs), as shown in Figure 2. Similarly, edge devices such as Smart Meters are uniquely identified and associated with Verifiable Credentials (VCs).

Key elements of the interaction include:

- Data collection and storage: Smart Meters and CS units provide real-time consumption and pricing data, transmitted via ORACLE services and stored in the decentralized storage (IPFS). EVs also contribute usage and charging demand data, which are hashed on-chain for auditability.

- Data sharing and notifications:

- –

- eMSPs notify the DSO of business activity changes.

- –

- The DSO provides and requests data from the CPO, stored in IPFS for later use in scheduling and forecasting.

- –

- The EV drivers are informed of updated charging options and schedules.

- Forecasting and decision-making: The DSO feeds forecasted production and consumption data into the DAO, which becomes accessible to DApps for demand–supply balancing. Proposals for new pricing models are triggered, disseminated to stakeholders, and voted upon.

- Voting and consensus: DAO members vote on submitted proposals (e.g., pricing, onboarding devices, data access rules). Once consensus is achieved, the proposal is executed through its associated smart contract.

- Execution and settlement: Actions such as micro-payments are performed automatically via the treasury smart contract, ensuring immediate settlement of economic transactions according to DAO-approved rules.

6.1.3. HITL Interaction and Incentives

In the Energy Grid use case, actors interact with DAO-governed smart contracts via authenticated dashboards and digital wallets, enabling them to review proposals, cast votes, and approve exceptional actions. HITL intervention is required at predefined governance points, such as resolving conflicts between grid stability and cost optimization, validating reconfiguration proposals triggered by anomalous grid conditions, or adjusting incentive and pricing parameters.

Participation is incentivized by direct operational responsibility for grid stability, regulatory compliance, and revenue allocation rather than by speculative token rewards. Once quorum and approval thresholds are met, smart contracts deterministically enforce the approved decisions, ensuring that human actions remain transparent, auditable, and bound by the same governance rules as automated agents.

6.1.4. Swarm Intelligence Perspective

The DAO-driven interaction model in the Energy Grid UC reflects swarm intelligence principles by enabling emergent, adaptive coordination without requiring centralized oversight. Similar to biological swarms, local interactions, such as electricity price proposals from a Distribution System Operator (DSO), the onboarding of new smart meters or charging stations, or updates to data-sharing policies, propagate through stigmergic processes. In these processes, published proposals guide the ecosystem’s collective decision-making. This ensures self-organization, as proposals emerge dynamically from the needs of individual actors (e.g., a CPO defining selling prices or an organization suggesting new data-access rules) and are collectively refined through the voting process. Distributed control replaces unilateral authority, since no single stakeholder dictates outcomes; instead, decisions gain legitimacy through decentralized consensus. At the same time, the system fosters resilience and adaptability, as participants, whether edge devices, organizations, or governance rules, can be flexibly added or removed without disrupting global operations. Finally, transparency and trust are guaranteed by smart contracts that immutably log DAO, approved actions, ensuring that governance remains auditable, tamper-resistant, and non-repudiable.

6.2. UC Structural Safety: Structural Safety Assessment of Buildings and Critical Infrastructure

To monitor the structural conditions of buildings and infrastructure before, during, and after severe events such as earthquakes, sensors and decision support systems are employed in this use case. Currently, sensor data collection occurs on the customer’s premises and at local sensors, primarily accelerometers and laser deformation sensors. These data require verification, filtering, correction, and interpretation. Only after that, some conclusions can be withdrawn regarding the safety of the structures in question. To do so, the data is currently transferred to a remote decision support system (DSS) for post-processing and decision-making, which is inefficient and causes several practical problems, including data privacy concerns and, most importantly, increased response time. There are also several cases where, due to a lack of electricity, an electricity circuit jump, or a problem with the communication lines, the crucial data is not even transferred fully to the central computing unit, although it is possible to retrieve it.

One issue with the centralized approach in use is data latency. Such data needs to be recorded at least 200 Hz at multiple channels. This is a demanding data streaming and processing task, especially when numerous sensors are involved, which is why some sensors may delay submitting data to this external software.

Therefore, it is highly beneficial to migrate the central DSS to a distributed architecture with components at both the edge and in the central cloud. Decentralized computing capabilities within OASEES not only improve the robustness of the DSS in use but also enable swarm technology to combine geographically distributed sensors around an earthquake epicenter.

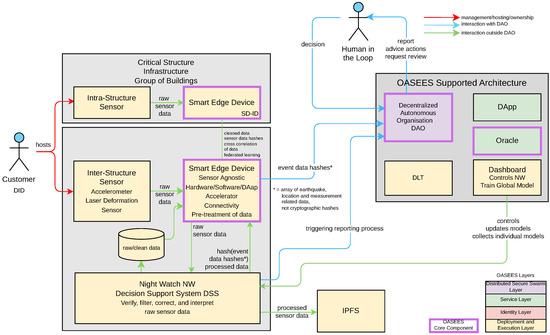

Table 3 on the next page and Figure 3 show the relevant actors, systems components and data structures, and their relationship.

Table 3.

Main actors, systems, components, and data structures of the structural safety use case.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the structural safety use case.

At the center of that use case is the OASEES-supported architecture that receives information about a potential earthquake event (location, measurements, related data), which is presented to the human-in-the-loop for review and to request advice and actions.

Sensor data from buildings and infrastructure are monitored by the Night Watch (NW) Decision Support System (DSS) before, during, and after seismic events. The challenge arises from the high volume of data generated during earthquakes, which often leads to delays in detection and reporting when processed centrally. To address this, the Structural Safety UC shifts the logic to edge devices by embedding NW-DSS within them. Once an event is detected by the NW or reported by an external agency, the NW-DSS triggers the DAO to initiate a reporting process, switching edge devices into swarm mode. Edge devices pre-process, filter, and cross-correlate the data locally, storing hashes on the blockchain (DAO) for integrity, while uploading processed data to IPFS. A Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) validates and classifies the event (e.g., an aftershock vs. a new earthquake) through DAO proposals that may adapt or terminate swarm activities.

This approach aims to minimize latency, improve decision-making, and ensure critical stakeholders (e.g., airports, tunnels, emergency teams) receive reliable safety assessments within the first minutes after an earthquake, as a significant improvement over centralized systems that deliver delayed responses.

6.2.1. DAO Activities and Proposals

DAO-based governance in the Structural Safety UC supports the following categories of proposals:

- HITL Proposals:

- –

- Register or update decision algorithms for safety measurement (NW configuration).

- –

- Verify or approve changes to NW-DSS algorithms.

- –

- Onboard or remove swarm edge devices.

- DApp/Smart Contract Proposals:

- –

- Request access to data streams or stored features.

- –

- Enable DApp activities such as event-triggered reporting and notifications.

- –

- Communicate with edge devices to trigger specific swarm activities.

6.2.2. Interaction Schema

The interaction stack for the Structural Safety UC involves smart edge devices, DAO governance, IPFS storage, HITL decision-making, and external agencies:

- –

- Smart Edge Devices authenticate sensors, filter and cross-correlate raw data, store processed data in IPFS, and commit hashes to the DAO.

- –

- The DAO manages proposals for algorithm updates, device onboarding, and reporting triggers.

- –

- The HITL evaluates DAO-generated reports, validates classifications, and proposes reconfigurations.

- –

- External Agencies access DAO/DApp outputs for emergency interventions and reporting.

6.2.3. HITL Interaction and Incentives

In the Structural Safety use case, HITL actors interact with the system via DAO-linked dashboards that present aggregated event reports, confidence indicators, and provenance information derived from swarm-processed sensor data. Human input is required to validate or classify detected events (e.g., distinguishing aftershocks from new seismic events), approve changes to decision-support algorithms, and determine escalation or termination of swarm activities.

Incentives for participation are primarily safety- and responsibility-driven: timely human validation directly affects public safety, liability exposure, and regulatory compliance. All human decisions are submitted as DAO proposals, ensuring traceability, accountability, and non-arbitrary intervention in safety-critical workflows.

6.2.4. Swarm Intelligence Perspective

The DAO-driven coordination model within the Structural Safety UC embodies principles of swarm intelligence, enabling adaptive, resilient collective behavior in disaster-response scenarios. Under stress conditions, such as earthquakes, local edge devices perform rapid sensor analysis and fault detection, thereby ensuring self-organization through immediate responses that do not rely on centralized commands. These local assessments propagate upward through DAO proposals and consensus mechanisms, creating stigmergic reinforcement whereby consistent signals across multiple devices strengthen the credibility of detected structural anomalies. In this way, distributed control is maintained, as no single authority dictates outcomes; instead, collective agreement among devices, edge nodes, and stakeholders ensures robustness in decision-making. The integration of HITL governance further enhances resilience and adaptability, as human expertise is combined with swarm-driven consensus to refine responses without undermining decentralization. Finally, transparency and trust are ensured by DAO-approved smart contracts that immutably record all anomaly detections, maintenance decisions, and response actions, guaranteeing auditability and accountability even in emergency conditions.

6.3. UC Windmill Maintenance: Predictive Maintenance of Windmills

Wind turbines are complex industrial systems that use various materials, and their components are complicated to recycle, especially the blades, which are made of layered composite materials. Extending the useful life of wind farms is an important goal to reduce the environmental and economic costs of demolishing them. Current techniques to extend the useful life of wind turbines rely on predictive maintenance. This type of maintenance involves continuous monitoring of data obtained from system elements. By analyzing this data, the state of the system can be characterized and used to improve the detection and prediction of failures through mathematical models, machine learning techniques, parameter estimation, and other methods.

Wind farm monitoring is primarily deployed internally in each wind turbine and measures acceleration, temperature, pressure, rotation speed, and current intensity. The techniques for monitoring wind turbine blades are commonly based on visual inspection, which can be performed by a human hand with a camera or by unmanned aerial vehicles. Other techniques use different sensors along the blade, which are intrusive and inconvenient. The objective is to deploy a portable, non-intrusive monitoring system based on acoustic signal analysis, which is independent of the wind turbine.

This manual assessment or the use of a centralized monitoring platform introduces latency, high operational costs, and limited scalability. The Windmill Maintenance UC, instead, integrates the OASEES architecture (DLT, SSI, DAO, and DApp) with IoT swarms, edge devices, and cloud computing to provide a decentralized, transparent maintenance solution. The DAO facilitates collective decision-making for critical processes, including dataset access, model governance, and protocol updates, while smart contracts automate the distribution of verified maintenance instructions.

Different factors can cause failures in a wind turbine blade. One of the most common causes is lightning striking the blade, which can cause internal damage. Other problems include delamination, erosion, cracks, and de-bonding caused by wind-blade interaction. As the aerodynamic noise generated by the blades depends on their aerodynamic performance, these failures should affect the acoustics measurable with a microphone.

The objective of this use case is to enable real-time fault detection and classification of anomalies in wind turbine blades through a Blade Acoustic Monitoring System (BAMS) that collects audio recording, wind speed and direction information, temperature, and humidity. This system uses a swarm of IoT devices to capture acoustic signals generated by wind interacting with turbine blades. By analyzing these signals, potential faults, such as cracks, delamination, and other structural weaknesses, can be detected early. Based on federated learning, the failure-prediction algorithm will be consolidated, aggregated, and distributed to IoT devices.

The outcomes of the Windmill Maintenance UC are reflected in enhanced reliability and operational safety, achieved by minimizing downtime, streamlining inspection workflows, and reinforcing stakeholder trust through transparent, on-chain governance. By decentralizing fault detection, anomaly classification, and maintenance decision-making, the Windmill Maintenance UC fosters a more resilient, efficient, and trustworthy wind turbine infrastructure.

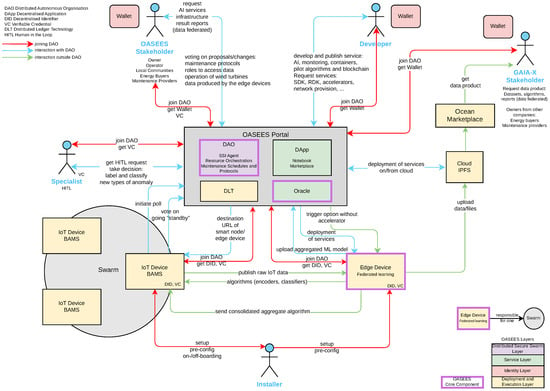

Table 4 on the next page and Figure 4 illustrate the relevant actors, system components, and data structures, along with their relationships.

Table 4.

Main actors, systems, components and data structures of the predictive maintenance use case.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the predictive windmill maintenance use case.

At the center of the use case is the OASEES-based portal, which monitors blade structures, orchestrates swarm resources, and generates test reports. It also manages polls from the swarm on whether it is agreed to go to standby.

Edge devices will use the raw data from the Blade Acoustic Monitoring Systems in the swarm to perform federated learning and distribute consolidated, aggregated encoder and classifier algorithms to the swarm.

As a side effect, the collected data can be sold as a data product via a marketplace to Gaia-X stakeholders.

6.3.1. DAO Activities and Proposals

The objective of the Windmill Maintenance UC is to support objective inspections of wind turbine blades through a BAMS. This system enables real-time fault detection and anomaly classification using acoustic signals collected by a swarm of IoT devices interacting with turbine blades. The DAO governs the orchestration of maintenance, device management, and model evolution through the following proposals:

- DAO joining members: Proposal for allowing new stakeholders (e.g., maintenance operators, specialists) to join the DAO.

- New maintenance protocol: Proposal for collective definition and approval of maintenance procedures based on acoustic fault detection.

- DAO data-access voting: Proposal for granting or denying developer and researcher access to datasets generated by IoT and edge devices.

- New model voting: Proposal for evaluating and adopting new anomaly-detection algorithms for wind turbine monitoring.

- Proposal: Standby of idle assets: Temporarily disabling devices such as turbines not detected by the monitoring system.

The Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) integration, as demonstrated in the Windmill Maintenance UC’s predictive maintenance scenario, shows how DAOs balance automation with expert oversight. When the federated learning system detects anomalous acoustic signatures from wind turbine blades, the DAO triggers a governance proposal requesting specialist review. Specialists access data via verifiable credentials managed by the SSI framework, ensuring that sensitive operational data remains protected while enabling the necessary human expertise.

6.3.2. Interaction Scheme

The interaction schema for the Windmill Maintenance UC includes the OASEES Portal (DLT, SSI, DApp, DAO), swarm IoT devices, edge devices, and cloud services:

- Authentication: All stakeholders and devices are authenticated through the OASEES DID-based identity layer. IoT and edge devices must be verified, configured, and installed prior to operation.

- IoT Devices: Acoustic sensors continuously sense data from turbine blades, transmitting signals to edge devices.

- Edge Devices: Edge devices identify datasets, perform preliminary fault analysis, and store data hashes on the blockchain. Anomalies or predicted failures trigger notifications to DAO and maintenance operators.

- DAO and HITL Specialists: HITL specialists initiate DAO membership proposals, propose maintenance protocols, and oversee the validation of new models. DAO members vote on maintenance protocols, data access, and algorithmic updates.

- Data Governance: Developers requesting access to datasets are subject to DAO voting. Notifications are distributed to HITL specialists for oversight.

- Model Governance: Developers and HITL specialists propose new models for acoustic fault detection. Approved models are disseminated through the DApp to maintenance operators for integration into workflows.

- Smart Contracts/DApp: These ensure secure data hashing, record DAO decisions, and automate the distribution of maintenance protocols, algorithmic instructions, and off-chain guidance.

- Maintenance Operators: Receive protocol updates or model adoption instructions, enabling real-time adjustment of inspection and maintenance activities.

6.3.3. HITL Interaction and Incentives

In the Windmill Maintenance use case, HITL actors interact with DAO-governed smart contracts through maintenance dashboards that expose anomaly reports, model outputs, and historical asset data anchored on-chain. Human intervention is required to validate predicted faults, approve maintenance actions, and prioritize repair schedules when trade-offs arise between cost, availability, and risk.

Participation is incentivized by reduced downtime, optimized maintenance costs, and improved asset lifespan rather than by open-token governance. Approved decisions are enforced through smart contracts that trigger maintenance workflows and update asset states, ensuring that human expertise complements automated swarm analytics without reintroducing centralized control.

6.3.4. Swarm Intelligence Perspective

In the Windmill Maintenance UC, swarm intelligence principles are reflected in the distributed monitoring and maintenance of wind turbines through acoustic sensing. Local IoT devices embedded in the BAMS continuously capture and analyze sound patterns, thereby enabling self-organization through autonomous anomaly detection without relying on a central controller. These local interactions are reinforced through stigmergic processes, in which anomaly reports and fault indicators serve as digital traces that collectively enhance the reliability of global fault-detection outcomes. Distributed control is ensured through DAO governance, where maintenance protocols, data access requests, and new model proposals are validated via consensus rather than imposed hierarchically. This enables adaptive decision-making that scales across multiple turbines and stakeholders. The system further demonstrates resilience and adaptability, as devices, operators, and algorithms can be dynamically integrated or replaced while maintaining uninterrupted operation. Finally, transparency and trust are anchored on-chain, with smart contracts recording sensor data hashes, maintenance votes, and protocol updates, ensuring auditability and reinforcing stakeholder confidence in the reliability and safety of turbine operations.

6.4. Mapping Scientific Contributions to Results

To support the scientific contributions stated in Section 3.2, we explicitly map each contribution to the corresponding architectural design, implementation, and validation elements presented in this paper (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mapping of Scientific Contributions of Section 3.2 to Evidence Presented in the Paper.

7. OASEES Platform Implementation

This section presents details of the OASEES Stack Prototype, which is publicly accessible in [59]. The OASEES stack prototype demonstrates a comprehensive Web3.0, cloud-native swarm computing platform that integrates blockchain technology, decentralized storage, and autonomous device management. This proof of concept (PoC) validates the technical feasibility and architectural soundness of a DAO framework for managing edge computing resources and algorithm marketplaces.

The OASEES platform (Figure 5) is built on top of the SDK that provisions edge clusters, wires CI/CD for multi-arch images, deploys workloads through the Kubernetes API, and maintains runtime awareness across core and edge. The SDK exposes two developer-facing interfaces: a CLI and a Jupyter Notebook v.8.6.3, enabling the same code to be built, packaged, and deployed with minimal refactoring. This dual interface is the core of the architecture, comprising Notebook, RDK, CI/CD, Quantum DevKit, and external APIs, with Python v3.10.18 and Kubernetes variants as the baseline runtime. The runtime is split into a core site and multiple edge nodes. The core site runs the K3s master, aggregates resource-intensive tasks, and schedules workloads, while edge nodes are lightweight workers near sensors that join the cluster for low-latency processing. This separation aligns the control plane with the need for locality on constrained devices.

Figure 5.

OASEES Platform architectural overview.

Architecture and developer surface. The SDK groups functions into modules that cover interactive work in notebooks, scripted operations via the CLI, and CI automation glue. The CLI is installable as a Python entry point and prints an indexed list of supported operations (cluster init, joining workers, registering nodes, workload actions) so developers can script repeatable tasks or run them ad hoc.

The onboarding sequence that abstracts away infrastructure specifics and registers resources in the OASEES marketplace and DAO is as follows: the master initializes K3s, is registered, and each edge device joins and registers with it. After that, the cluster is listed and ready for workloads. The flow is exposed as CLI and internal functions.

- –

- Init-cluster (CLI) on the master installs all K3s components.

- –

- Register-cluster (internal) records the K3s master in the OASEES marketplace/DAO.

- –

- Join-cluster (CLI) on each edge device installs K3s and joins the cluster.

- –

- Register-new-nodes (CLI and internal) detects unregistered workers and registers them.

- –

- After all workers register, the cluster is DAO-registered and visible in the Portal.

When the cluster is ready, the Kubernetes API starts receiving workload requests. The typical workflow begins when a user acquires a containerized algorithm from the OASEES marketplace; the image is stored on IPFS and retrieved in a decentralized manner. The platform chooses a suitable worker by matching GPU/TPU needs using Kubernetes labels provided by the OASEES Agent. The SDK then deploys a Kubernetes Deployment, creates a Service to provide a stable endpoint, and configures an Ingress to expose the API securely. The pipeline is CI/CD-driven and avoids a central monorepo.

The SDK uses a Kubernetes-native build path to produce multi-architecture images on the same cluster. A BuildKit Pod and an Image-Build Job integrate BuildKit with nerdctl/containerd to accelerate builds through caching and parallel layer processing and to reduce required privileges. The Job triggers the Pod, manages the lifecycle, and creates images for both amd64 and arm to support heterogeneous edge hardware. This design keeps the build surface close to where workloads run and enables pipelines to create portable artifacts without requiring special builders.

The Agent runs as a DaemonSet on every node. It is responsible for device-side blockchain interactions with the DAO and for discovering accelerators. It assigns labels to nodes so the scheduler can correctly place GPU/TPU workloads, keeping placement simple and enabling heterogeneous acceleration without manual host tuning. The SDK standardizes on Python, Kubernetes, and K3s, with optional KubeEdge compatibility depending on use-case needs. GitHub Actions is used to automate repeatable validations across platforms and to measure command responsiveness.

External API integration targets EOSC (and GAIA-X in the same section), with a focus on exposing data and services beyond a single pilot. D3.1 lists concrete steps: standard data formats and metadata models; service registration and discovery via the EOSC API; and AAI federation for sign-on. These steps ensure that OASEES assets remain discoverable and securely consumable within European data spaces.

7.1. Security Analysis and Threat Mitigation

The OASEES framework is designed to minimize trust assumptions and enhance tamper resistance in edge-swarm environments; however, it operates under a clearly defined threat model. This subsection summarizes the primary security threats and the corresponding mitigation mechanisms.

Oracle and data feed manipulation. OASEES mitigates oracle-level attacks by combining multiple design principles: (i) the use of authenticated data sources bound to decentralized identifiers (DIDs) and verifiable credentials (VCs); (ii) cryptographic anchoring of data hashes on-chain, enabling integrity verification of off-chain data stored in IPFS; and (iii) governance-controlled oracle registration and revocation via DAO proposals. While these mechanisms do not eliminate the risk of faulty or compromised sensors, they enable rapid detection, traceability, and coordinated response through DAO-governed actions.

Smart contract vulnerabilities. Smart contracts in OASEES are limited to governance, access control, and coordination logic, while computationally intensive and latency-critical functions are executed off-chain. This separation reduces the attack surface of on-chain code. Contract upgrades, parameter changes, and emergency interventions are performed exclusively through DAO-approved proposals, enabling collective oversight and auditability. Standard best practices, such as modular contract design, restricted privilege scopes, and pre-deployment testing, are applied; nevertheless, formal verification and automated vulnerability analysis are identified as important directions for future work.

Malicious or misbehaving swarm nodes. In swarm-based scenarios, OASEES relies on identity-bound participation and governance-driven lifecycle management. Edge devices and services are onboarded using SSI-based credentials and can be suspended or expelled via DAO decisions if misbehavior is detected (e.g., inconsistent data reporting or protocol violations). This approach does not assume fully honest participants but enables collective detection, accountability, and recovery, rather than relying on unilateral trust in any single node.

Overall, OASEES prioritizes transparency, auditability, and coordinated mitigation over absolute prevention, acknowledging that entirely eliminating adversarial behavior in open, distributed environments remains an open research challenge.

7.2. Experimental Evaluation of Smart Contract Performance

To quantify the operational feasibility of the proposed DAO- and DApp-based mechanisms, we conduct an experimental evaluation of smart contract performance, focusing on gas consumption, execution latency, and block confirmation dynamics.

7.2.1. Evaluation of Gas Cost, Block Number and Time

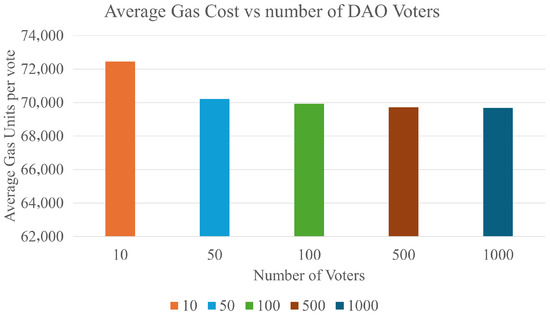

For the needs of assessment of the performance and scalability of the developed platform a set of experimental measurements in terms of gas costs, blocks needed, time per proposal and transaction processing latency were performed on the OASEES platform for different DAO sizes. For the performance assessment, an EVM Hardhat localnet was deployed to simulate a Layer-1 blockchain network and integrated into the framework. This setup operates as a standard Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) running on the “shanghai” upgrade. Such constraints are within the bounds of established high-performance networks. For the first test, the average gas cost was calculated for DAO voter counts of 10, 50, 100, 500, and 1000. As can be depicted from the average cost graph (Figure 6):

Figure 6.

Average Gas Cost for different numbers of DAO voters.

It is essential to underscore the declining average gas cost as the number of DAO voters increases, which also plateaus at approximately 100 voters and remains similar at 1000 voters. This can be justified by the fact that, as the number of DAO voters increases, more transactions run per scenario, and the additional transactions tend to use already initialized storage slots rather than creating new ones. In EVM terms, the workload shifts from expensive first writes (zero→non-zero ‘SSTORE’) to much cheaper updates (non-zero→non-zero). As a result, the fixed initialization costs are preferred over more activity, and the dominant operations-mapping lookups and counter increments remain effectively O(1) with respect to voter size. This explains why the mean gas quickly approaches a steady state by 100 voters and then changes only marginally up to 1000 voters. Additionally, this outcome is most evident when deployment/setup transactions are excluded or when each scenario runs in a fresh state to avoid counting one-time initialization multiple times.

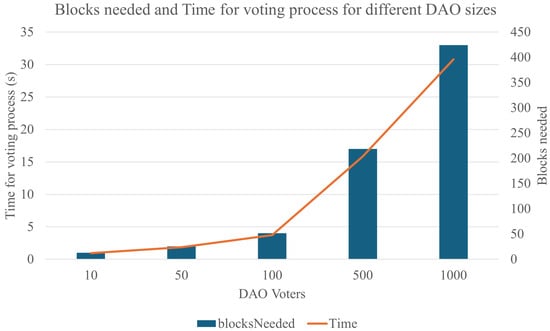

Regarding the required blocks and the time per proposal for different DAO voters, the tests conducted showed the expected behavior of the deployed DAO: both the number of blocks required and the time expected for a proposal to be executed follow a linear, incremental pattern as the number of DAO voters increases. This is shown in the relevant graph (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Blocks needed and Time (s) per proposal for different number of DAO voters.

7.2.2. Evaluation of Latency and System Response Time

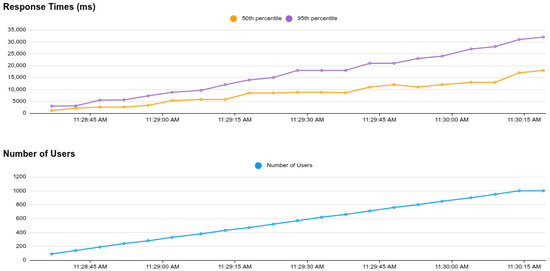

To evaluate system response time and performance scalability, a dedicated stress-testing evaluation was performed in the OASEES simulated blockchain environment using Locust to assess the DAO system’s behavior under varying load conditions. The test environment consisted of a Hardhat localnet configured with a 30,000,000 gas-units block limit and 3 s mining intervals, designed to simulate realistic blockchain constraints for governance-heavy DApps. Tests were performed with 100, 300, 500, and 1000 concurrent simulated users, as well as a scenario that starts with 100 and ramps up to 1000 with 50 simulated users/second. Each simulated user executes three primary operations: casting votes (55.6% of traffic), creating proposals (16.7%), and retrieving stored values via read-only calls (27.7%). All tests maintained zero failures, as the implementation includes client-side validation to prevent unnecessary transactions. For each test, 5 initial proposals were created prior to execution, enabling simulated users could start voting immediately. The resulting response times for increasing numbers of concurrent DAO users are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Response time evaluation for an increasing number of DAO users.

The primary performance bottleneck manifests as transaction queueing at the blockchain layer rather than JSON-RPC endpoint saturation. At 100 users, median response times stabilized at approximately 2.5 s with 95th percentile values around 2.9 s, indicating transactions are typically mined within a single block. Under 300 concurrent users, median latency increased to 5.6 s (roughly two blocks), while 95th percentile responses reached 11 s. At 500 users, median latency climbed to 8.8 s with 95th percentile at 18 s. The 1000-user scenario exhibited the most severe congestion, with median response times of 15 s and 95th percentile reaching 33 s.