Abstract

This study examines the role of different factors in supporting the sustainable use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies in higher education, particularly in the context of student interactions with intelligent and human-centered learning tools. Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) within the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the research provides a detailed look at how trust influences students’ attitudes and behaviors toward AI-based learning platforms. Data were gathered from 200 students at Occidental Mindoro State College to analyze the effects of social influence, self-efficacy, perceived ease of use, perceived risk, attitude toward use, behavioral intention, acceptance, and actual use. Results from SEM indicate that perceived risk and ease of use have a stronger impact on AI adoption than perceived usefulness and trust. The ANN analysis further shows that acceptance is the most important factor influencing actual AI use, reflecting the complex, non-linear relationships between trust, risk, and adoption. These findings highlight the need for AI systems that are adaptive, transparent, and designed with the user experience in mind. By building interfaces that are more intuitive and reliable, educators and designers can strengthen human–AI interaction and promote responsible and lasting integration of AI in education.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been increasingly prevalent in a variety of sectors related to teaching and learning in recent times. Regardless of the type of technology or its alleged benefits, researchers and practitioners are nonetheless very interested in the topic of technology adoption and use by education stakeholders [1]. The general student population’s adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in education can be influenced by their acceptance or rejection of other artificial intelligence (AI) tools, since students are important stakeholders and trustworthy information sources [2]. AI systems are improving their capacity to learn, reason, self-correct, and, in some domains, emulate human decision-making because of human intelligence [3]. In higher education, students may struggle to obtain timely and interactive assistance due to low teacher-to-student ratios [2]. AI is poised to significantly influence higher education, particularly in the realms of curricula and student admissions [3]. Several universities have begun to introduce AI programs, catering not just to computer science majors but also to business students, aiming to equip future business leaders [2]. Artificial intelligence (AI) has become more common in many parts of people’s lives, like medicine, law, finance, and entertainment. Researchers are working on making AI smarter by teaching it to understand language, recognize things in pictures, move around like robots, and even make decisions on its own. This makes us wonder how AI will change our society and the people in it as it becomes better at doing things that only humans could do, as well as the impact of trust of higher education students on accepting AI technologies [4].

Understanding and analyzing users’ trust in AI-enhanced technology is becoming more important as these technologies proliferate across a range of industries. Because AI is developing at a rapid pace, trusting the technology requires an equally comprehensive knowledge [5]. Work and services are being revolutionized by artificial intelligence (AI), with solutions that alter productivity and make forecasts more accurate. Sector-wide investment in AI is increasing; however, concerns have been raised regarding the unfair, discriminatory, and illegal use of AI, casting doubt on its reliability. For AI to continue being accepted and utilized in society, public confidence in its development and application must be maintained, allowing us to reap the benefits and return on investment [6]. It has been established that trust is crucial for technology adoption, and its significance is likely to increase as technologies become increasingly advanced [7]. Online research has examined the idea of trust comprehensively [8].

The application of ANN models provides a dynamic framework for analyzing and forecasting students’ opinions about AI technology in higher education. These models can identify patterns and correlations between various elements that influence students’ acceptance. The ANN model is a type of computing model that draws inspiration from the human brain. The science of artificial intelligence has achieved many recent advances, including image and speech recognition as well as robotics applications [9].

According to the government’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) preparedness index rankings, the United States leads globally with a score of 84.8, indicating a strong national readiness to integrate AI into public services such as healthcare, education, and transportation. Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Finland also rank highly, followed by China at sixteenth place. Although China ranks lower in readiness, its accelerated efforts to embed AI capabilities into public services demonstrate rapid national progress relative to countries with higher preparedness scores [10]. While these global indicators highlight the expanding capabilities and integration of AI at the institutional and governmental levels, they also underscore the growing need to understand how AI is perceived and trusted in specific contexts—particularly in education. Trust in AI within higher education can differ significantly from general trust in governmental or industry AI systems, as students and educators rely on AI tools for learning, assessment, and academic decision-making. This makes it essential to examine how users evaluate the reliability, usefulness, and ease of use of AI within educational technologies. Building on existing research in trust and educational technology, the present study extends this conversation by using both SEM and ANN to investigate how students form attitudes and adoption decisions toward AI tools in higher education.

According to [11], in the Philippines, 49% of Filipinos are aware of AI, showing a high level of national participation; Gen Z leads with 52%. Remarkably, 73% of respondents think favorably about AI, indicating that opinions vary widely between generations. Although Gen X and Baby Boomers are not far behind at 71% and 68%, respectively, younger demographics are most in favor of this viewpoint (76% in Gen Z and 71% in Millennials), despite this there is a 63% negative perception of AI tools, with 12% of people seeing them favorably, the study finds that Gen Z and Millennials have higher favorable net perceptions than Gen X and Baby Boomers [12]. According to the compiled data, the highest search volume for generative AI tools was seen in the Philippines (5288), followed by Singapore (3036) and Canada (2213) [13].

The effectiveness of AI in higher education has, however, not been extensively studied empirically, and even fewer studies have addressed the possible downsides and difficulties of these tools [4]. Certain studies did not assess students’ AI knowledge, which could have affected their perceptions. Additionally, it is important to take into account that student satisfaction, whether measured or not, is likely to have an effect in any country where students have a choice in the higher education institutions (HEI) they attend. Therefore, it is useful to study how students respond to artificial intelligence (AI). Future studies might examine the perspectives of students as well [14]. Therefore, this research attempts to fill this gap, applying Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze the complex relationship between various factors and effective machine learning model for determining the relationship between input and output variables is the artificial neural network (ANN) affecting the trust on acceptance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies among higher students in Occidental Mindoro State College (OMSC). In addition, this study provides educators and higher education institutions with a set of recommendations for encouraging students to use artificial intelligence (AI) for both advantageous and disadvantageous purposes.

1.1. Theoretical Framework and Variables

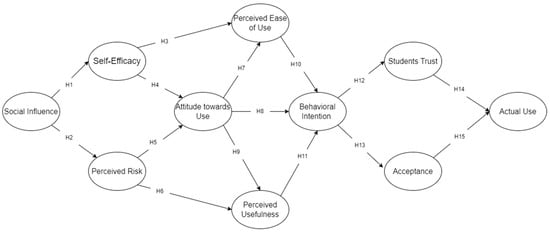

Figure 1 presents the framework that examines how social, cognitive, and perceptual factors shape students’ adoption of AI technologies. This approach is based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), as detailed in the work of reference [15], which is focused on understanding user adoption of emerging technologies. The study investigates a set of variables, namely Social Influence (SI), Self-Efficacy (SE), Perceived Risk (PR), Perceived Ease of Use (PE), Attitude towards Use (AT), Perceived Usefulness (PU), Behavioral Intention (BI), Students’ Trust (ST), Acceptance (AC), and Actual Use (AU), to assess their roles in the relationship between these factors and students’ acceptance of AI technologies.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

1.2. Relationship Between Variables

This portion aims to investigate the study’s hypothesis and analyze the relationships among different components. It will examine the framework that guides the research and examine how various factors interact.

H1.

There is a significant relationship between Social Influence on Self-Efficacy.

The study by [16] examines how task difficulty influences vulnerability to social influence, taking into account individual variations in task self-efficacy. It suggests that individuals with lower task self-efficacy may be more susceptible to social influence when faced with challenging tasks compared to those with higher task self-efficacy levels.

H2.

There is a significant relationship between Social Influence and Perceived Risk.

Although prior studies on risk perception have often emphasized individual cognitive assessments, growing evidence suggests that perceptions of technological risk are also shaped by social context. Individuals frequently rely on the reactions, experiences, and judgments of peers, instructors, and community members when evaluating whether a technology is safe or potentially harmful. This aligns with the “risk–benefit acceptability” model, which highlights that risk evaluations are influenced not only by personal beliefs but also by how risks and benefits are framed and communicated within one’s social environment [17]. When trusted others express confidence in a technology or demonstrate positive experiences with it, users tend to perceive lower levels of risk. Conversely, negative opinions or caution from one’s social circle can amplify perceived risks. Because social influence plays a central role in shaping attitudes toward new or unfamiliar technologies, it is reasonable to expect that students’ perceived risks associated with AI tools will be affected by the norms, endorsements, and behaviors of those around them.

H3.

There is a significant relationship between Self-Efficacy and Perceived Ease of Use.

Self-efficacy (SE) refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to successfully perform tasks associated with using a particular technology. Although prior studies have examined SE primarily in the context of university educators, the underlying theoretical mechanism applies equally to students, as both groups rely on confidence in their own abilities when interacting with digital tools. Research consistently shows that higher self-efficacy is associated with more favorable perceptions of how easy a technology is to learn and use, because individuals who feel competent experience fewer psychological barriers and require less external support when engaging with technology [18]. In the context of AI tools in higher education, students with stronger self-efficacy are therefore more likely to perceive AI systems as intuitive, manageable, and less effortful to operate, suggesting a positive association between SE and Perceived Ease of Use (PEU).

H4.

There is a significant relationship between Self-Efficacy to Attitude towards Use.

Hayat [19] proposed that self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in influencing an individual’s selection of learning activities, level of exertion, and perseverance. Moreover, students’ self-efficacy can significantly impact their motivation, stemming from their self-assessment of their capabilities to accomplish assigned tasks, which in turn influences their perceived learning outcomes. Previous research has also highlighted the correlation between self-efficacy and students’ perceptions. Conversely, Ref. [20] emphasized the significance of students’ attitudes as a crucial determinant of self-efficacy. The interplay between self-efficacy and students’ attitudes has been corroborated by several earlier studies.

H5.

There is a significant relationship between perceived risk and attitude towards use.

Perceived risk (PR) refers to the extent to which individuals believe that using a technology may lead to negative outcomes such as privacy loss, misinformation, diminished academic integrity, or unintended consequences. While [21] discusses general societal concerns surrounding AI, such as privacy infringement, job displacement, and harmful misuse, these risk perceptions are also highly relevant to students in higher education, who increasingly interact with AI tools in academic contexts. Students may be concerned about the accuracy of AI-generated information, potential violations of academic policies, or the security of personal data when using AI systems. Such risk perceptions can influence whether students form favorable or unfavorable attitudes toward using AI for learning. In line with technology acceptance research, higher perceived risks typically lead to more cautious or negative attitudes toward technology adoption. Thus, applying the insights from [22] to the student context provides a theoretical basis for expecting that increases in perceived risk will negatively shape students’ attitudes toward AI use in higher education.

H6.

There is a significant relationship between perceived risk and perceived usefulness.

Studies have highlighted that perceived risk can influence how individuals assess the usefulness of new technologies, particularly when the technology is used to obtain or verify information online. Users who perceive fewer risks, such as concerns about accuracy, privacy, or reliability, are more likely to view AI tools as beneficial and supportive of their goals [23]. This mechanism is also relevant for students, who often rely on AI tools for academic tasks such as information retrieval, content summarization, or generating explanations. When students believe that using AI poses minimal risks, they may be more inclined to view these tools as useful, trustworthy, and capable of enhancing their academic performance. Conversely, heightened risk perceptions may lead students to question the reliability and educational value of AI tools. Therefore, the relationship between perceived risk and perceived usefulness is expected to be particularly meaningful in the context of AI use in higher education.

H7.

There is a significant relationship between perceived ease of use and attitude towards use.

Research consistently shows that when a technology is perceived as easy to use, individuals are more likely to form favorable attitudes toward adopting it. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) reduces the cognitive effort required to learn or operate a system, thereby increasing users’ overall satisfaction and willingness to engage with the technology. According to [24], user-friendly system design contributes positively to users’ perceptions of technology, enhancing their inclination to view it as beneficial and manageable. In the context of higher education, students who find AI tools intuitive and straightforward are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward using them for academic tasks. Thus, PEOU is expected to exert a significant influence on Attitude Toward Use, as easier interactions with AI systems lead to more positive evaluations of their usefulness and appropriateness in learning environments.

H8.

There is a significant relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions.

Numerous research findings indicate that the simplicity and user-friendliness of AI technology play a crucial role in shaping people’s willingness to adopt it. This concept of perceived ease of use is essentially how effortless and uncomplicated users find the process of utilizing AI technology [24].

H9.

There is a positive relationship between attitude towards use and behavioral intention of students in using AI.

The choice of managers to implement artificial intelligence (AI) in organizational decision-making processes is shaped by their recognition of its advantages and potential drawbacks. Ref. [25] supports the idea that managers’ predispositions towards AI predict their willingness to utilize it. The suggested Integrated AI Acceptance-Avoidance Model (IAAAM) accounts for 62% of the difference in the readiness to adopt AI, indicating its effectiveness in forecasting and comprehending managers’ acceptance behaviors.

H10.

There is a positive relationship between Perceived Usefulness to attitude towards the use of AI.

Several studies, including those by [24], have demonstrated a strong correlation between individuals’ perceived usefulness of e-learning systems and their overall attitude towards using them. Ref. [26] took this further, applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explore how various factors influence the adoption of e-government learning. They found that both perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, along with their underlying influences, significantly impact a user’s intention to engage with the system and ultimately their actual usage. Interestingly, the study also revealed a two-way relationship, where the user’s overall attitude towards the system can influence their perception of both ease of use and usefulness (r = 0.56, 0.35, p = 0.000, 0.006).

H11.

There is a positive relationship between perceived usefulness and the behavioral intention of students in using AI.

The factor of perceived usefulness has a significant impact on user satisfaction and their intent to engage with Moodle. The model put forward successfully accounted for 71.4% of the variation in user satisfaction, 61.7% in ease of use, 55.3% in the behavioral intention to use Moodle, and 30.4% in perceived usefulness. Ref. [27] delved into the utilization of e-government learning, employing the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to investigate the effect of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, along with their precursors, on the intention and actual use of a system.

H12.

There is a significant relationship between behavioral intention and student trust.

Although [26] examines technology adoption in the financial technology context rather than educational AI, its findings remain theoretically relevant because both contexts draw from similar principles of technology acceptance. Specifically, Ref. [28] demonstrates that trust plays a significant role in shaping behavioral intentions toward using new digital systems, showing a positive coefficient of 0.586 in predicting intention. While the domain differs, the underlying mechanism—where users’ intentions to adopt a technology are linked to their perceptions of its reliability and trustworthiness—can also be observed in educational environments. For students, stronger behavioral intentions to use AI tools may enhance their familiarity and comfort with these systems, which in turn can influence the degree of trust they place in them over time. Thus, although the cited study originates from a different context, the generalizable behavioral mechanism it describes supports the expectation of a meaningful relationship between Behavioral Intention and Student Trust in AI within higher education [29]

H13.

There is a significant relationship between behavioral intention and acceptance.

Understanding users’ acceptance and utilization of a system, along with their capability to embrace and apply it, is possible by examining behavioral intention and usage behavior [30]. The connection between an individual’s behavioral intention (BI) and their actual use of a system (SU) has been extensively studied within the field of technology acceptance. Here, behavioral intention refers to a person’s intention to engage in a specific behavior, while system use reflects the extent to which a person actually employs information technology [31].

H14.

There is a significant relationship between students’ trust and actual use.

Students who are willing to adapt to the use of mobile learning and are aware of its advantages and disadvantages are said to have perceived trust. Perceived trust in behavioral intentions is influenced by several factors, including integrity, personal space, and data privacy. These factors ultimately affect how mobile learning is used. Students’ dependence on a tool, apparatus, process, framework, or mindset when utilizing the approach in its whole can be understood as perceived trust. Technology trust is determined by the student’s experience with it and is impacted by the factors that influence it [32].

H15.

There is a significant relationship between acceptance and actual use.

Numerous frameworks and theoretical approaches have been established based on existing literature to explore the adoption and intent of using new technologies among users. Different scholars have taken these established models and theoretical approaches, adapted them, and tested them to gain a deeper insight into how users accept and utilize technology, and how these patterns can be predicted. It was discovered that, in comparison to other similar frameworks and theories related to the adoption of information systems and information technology (IS/IT), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) stands out as the most explanatory. The UTAUT emerges as a leading model for understanding technology acceptance, emphasizing the technological factors crucial for the successful deployment of information systems [33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study employed a descriptive–correlational design and utilized both online and paper-based survey administration to maximize student participation. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling. For the online survey, a Messenger link was distributed to student groups and class group chats with permission from course instructors and student leaders. Printed questionnaires were also distributed in selected classrooms to reach students who had limited access to the internet. The survey was open for a total of two weeks, during which multiple reminders were sent to encourage participation.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be currently enrolled students at Occidental Mindoro State College (OMSC). No additional exclusion criteria were applied, as the study aimed to capture a broad representation of student experiences with AI tools. Both adult and minor students were eligible to participate. For participants below 18 years old, parental/guardian consent and minor assent were obtained prior to data collection, in accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines. Out of the total number of students invited, approximately 230 accessed or received the survey, and 200 complete and usable responses were obtained, yielding an estimated response rate of around 87%. Slovin’s formula was applied to determine the minimum sample size needed to represent the student population of Occidental Mindoro State College (N = 5842 students enrolled during the academic year of data collection). Using a margin of error of 7% (e = 0.07), the required sample size was calculated to be 197. The final dataset included 200 complete responses, which meets and slightly exceeds the minimum requirement. Therefore, the achieved sample size is adequate for the study’s descriptive–correlational design and the structural equation modeling procedures used.

The final dataset consisted of responses to a 60-item questionnaire measuring the constructs included in the study.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of 200 individuals surveyed at Occidental Mindoro State College. The predominant age group among the respondents is 18 and below, which is 86% of the total surveyed participants. In terms of gender distribution, males constitute the majority, making up 59% of the participants. These respondents are primarily affiliated with three academic departments: the College of Business and Management (CBAM), the College of Arts, Science, and Technology (CAST), and the College of Teacher Education (CTE). Regarding financial background, a significant portion of the respondents (59.5%) reported having a monthly income of below PHP 15,000.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the respondents (N = 200).

2.2. Questionnaires

The study employed a survey designed to assess factors based on the Technology Acceptance Model, incorporating components from various related research. The survey was structured in three segments: an introduction explaining the purpose of the study, a demographic section to collect participant information, and a core set of questions. These questions focused on evaluating 10 principal factors: Social Influence, Self-Efficacy, Perceived Risk, Perceived Ease of Use, Attitude towards Use, Perceived Usefulness, Behavioral Intention, Students’ Trust, Acceptance, and Actual Use. Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a Likert Scale from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement), aiming to assess the role of trust in the acceptance of AI technologies in higher education, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The construct and measurement items.

2.3. Statistical Analysis: Structural Equation Modeling and ANN

The researchers adopted a hybrid approach, combining Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), diverging from the traditional reliance solely on SEM that has characterized much of prior research. They initiated their study with a two-step process, where SEM was utilized first, offering numerous advantages over traditional data analysis methods by providing a comprehensive statistical framework for the investigation of both observed and latent variables. Furthermore, ANNs were employed as an effective tool for evaluating performance in scenarios where the relationship between inputs and outputs is complex and non-linear [47]. To validate the robustness and reliability of these methods, the analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS AMOS software, version 22. This innovative approach facilitated the exploration of how trust influences the acceptance of AI technologies among higher education students.

In evaluating the suitability of a structural equation model, goodness-of-fit indices play a crucial role in gauging the model’s effectiveness in capturing the interactions among variables. This process involves a continuous refinement to pinpoint the model that exhibits the best fit. Among the indices commonly employed for this purpose are CMIN/DF, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). A table, referred to as Table 3, was compiled to showcase both the ideal and acceptable values for these indices. The GFI, which is influenced by the size of the sample and operates on a scale from 0 to 1, considers values above 0.80 to be acceptable due to its reliance on residual values. Meanwhile, an RMSEA value at or below 0.08 is indicative of a good model fit, with values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08 representing an adequate fit. Additionally, a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value below 0.08 is also considered acceptable. Although some incremental fit indices such as CFI, GFI, and NFI fall below the more conservative thresholds typically cited in SEM literature, recent methodological guidance [48] emphasizes that absolute fit indices (RMSEA and SRMR) are more robust indicators of model adequacy, particularly in complex models with many latent variables and numerous items. The final model demonstrates acceptable values for RMSEA (0.075), SRMR (0.072), and CMIN/DF (2.129), indicating reasonable model fit despite the lower performance of incremental indices. Lower GFI, NFI, and CFI values are expected in models with large item counts and moderate sample sizes, and do not invalidate model adequacy when primary indices fall within recommended limits.

Table 3.

Model fit values.

2.4. Ethics Consideration

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [54]. The research involved minimal risk and focused solely on collecting non-identifiable survey data from participants. Prior to data collection, all participants were informed about the study’s objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents in compliance with Republic Act No. 10173, also known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012. For participants below 18 years old, a parental or guardian consent form, along with minor assent, was required before participation. Only students who submitted the duly signed consent and assent forms were allowed to take part in the study.

To ensure confidentiality, no personal identifiers were collected, and all responses were used exclusively for academic and research purposes. Data were stored securely and accessed only by the author.

3. Results

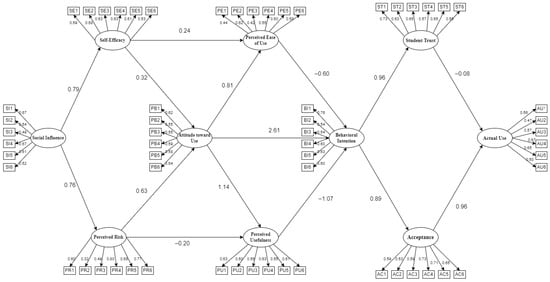

In Figure 2, the initial structural equation modeling (SEM) is presented, which explores the impact of trust in shaping higher education students’ acceptance of AI technologies. As per the research conducted by [55], a factor loading of 0.70 demonstrates a strong correlation between an item and its underlying concept, whereas a range of 0.50 is also acceptable, as it indicates a correlation.

Figure 2.

Initial SEM results.

To assess construct reliability and validity, multiple reliability indices were examined, including Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and Composite Reliability (CR). As shown in Table 4, all constructs demonstrated Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.708 to 0.804 and rho_A values between 0.716 and 0.813, exceeding the commonly recommended threshold of 0.70 [48]. Composite Reliability values ranged from 0.804 to 0.859, also surpassing the minimum acceptable criterion of 0.70, thereby confirming internal consistency reliability for all latent constructs.

Table 4.

Construct reliability and validity.

Convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). All constructs achieved AVE values of 0.50 or higher (AVE range: 0.500–0.598), indicating that each construct explains at least 50% of the variance in its indicators [56]. This meets the recommended threshold for convergent validity in reflective measurement models. Together, these results demonstrate that the reflective constructs used in the study exhibit adequate construct reliability and convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was assessed using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion in Table 5 and the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) in Table 6. Following the recommendations of refs. [48,57], HTMT was employed as the primary diagnostic tool because it provides a more robust evaluation of construct distinctiveness, particularly in models involving conceptually related variables such as those in technology acceptance research. After refining the measurement model and removing overlapping or low-loading items, all HTMT values were found to be below the conservative threshold of 0.90, indicating that the latent constructs are empirically distinct from one another. This remained true even for theoretically proximal constructs, such as Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use or Attitude and Behavioral Intention, confirming adequate discriminant validity. Complementary assessment using the Fornell–Larcker criterion showed that, although several constructs exhibited correlations approaching the square root of their AVE values, such patterns are expected in behavioral studies where constructs naturally share conceptual similarities. Moreover, prior methodological work suggests that the Fornell–Larcker criterion may be overly conservative and can signal false positives for discriminant validity issues even when HTMT values are acceptable. Given that the HTMT analysis provided strong evidence of construct distinctiveness and the AVE values remained within acceptable limits, the Fornell–Larcker results were deemed satisfactory. Overall, the combined evidence from HTMT and Fornell–Larcker confirms that the measurement model demonstrates adequate discriminant validity, allowing the structural model evaluation to proceed confidently.

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Table 6.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

Table 7 presents the results of the structural model analysis, including standardized path coefficients (β), p-values, effect sizes, and 95% confidence intervals for each hypothesized relationship. A hypothesis was considered supported and significant when the p-value was ≤0.05 and the confidence interval did not include zero. The results reveal several statistically significant pathways, as well as notable non-significant relationships that help explain the underlying behavioral mechanisms driving AI adoption among higher education students.

Table 7.

Summary and results.

During the measurement-model evaluation, several originally included Perceived Risk items (e.g., those referring to trust in developers, security assurances, or regulatory oversight) demonstrated conceptual overlap with trust-based constructs. Consistent with recommendations for construct purity in SEM, these items were removed. Only items that reflected students’ subjective assessment of potential negative outcomes or uncertainty associated with AI use were retained in the final Perceived Risk construct. Items PR1, PR2, and PR5 were excluded during scale refinement because their content reflected trust or confidence rather than perceived risk. Their removal improved convergent and discriminant validity. The item PE3 (‘I find AI tools untrustworthy because they give a lot of non-existent answers’) was originally reverse-coded to align with the Perceived Ease of Use construct. However, reverse-worded items are known to generate method effects and reduce reliability. PE3 displayed low factor loading and cross-loading behavior; therefore, the item was removed from the final measurement model. Only positively worded ease-of-use items were retained.

The analysis shows that Social Influence significantly and positively predicts both Self-Efficacy (H1: β = 0.593, p = 0.006) and Perceived Risk (H2: β = 0.579, p = 0.023), underscoring the strong role of social factors in shaping students’ psychological readiness to use AI. This aligns with prior SEM research showing that social influence constructs, such as perceived peer behavior, direct social pressure, and group norms, are powerful predictors of intention and behavior. For example, in studies on adolescent smoking, perceived behavioral pressure and social norms remained strong predictors of both current and future smoking behavior, even after attitude and self-efficacy were included in the model [58]. Such findings help contextualize why social influence strongly contributes to students’ confidence and perceptions of risk when adopting new technologies such as AI.

The significant effect of Social Influence on Perceived Risk also reflects broader behavioral patterns observed in digital environments. Research on privacy behaviors across social media platforms shows that users’ risk-benefit analyses, trust in the platform, and fear of missing out influence the extent to which they disclose personal information—particularly in environments with varying degrees of user control over privacy settings [59]. This perspective helps explain why students exposed to strong social cues may develop heightened or reduced perceived risks depending on the social environment surrounding AI use.

Self-Efficacy, however, did not significantly predict Perceived Ease of Use (H3: p = 0.195) or Attitude toward Use (H4: p = 0.242). This suggests that personal confidence in one’s technological abilities does not automatically translate into positive evaluations of AI systems. This pattern is consistent with prior research, which shows that while self-efficacy is a core socio-cognitive belief, attitudes are shaped by affective judgments and contextual experiences, rather than ability alone. For instance, studies on teacher burnout have documented that high burnout is associated with less favorable attitudes toward inclusive education, revealing a disconnect between self-belief and evaluative judgment [60]. Similarly, additional evidence suggests that self-efficacy may influence learning-related perceptions indirectly: although higher self-efficacy increased curiosity and perceived feedback value during formative assessments, overall learning progression remained unchanged, indicating subtle mediated rather than direct effects [61].

Perceived Risk demonstrated a strong and significant direct effect on Attitude toward Use (H5: β = 0.471, p = 0.005). Prior research supports this pattern: in studies involving database management systems, perceived risk significantly influenced attitudes toward adoption readiness, although gender did not moderate this effect [62]. This reinforces the notion that lower perceived risks are associated with more favorable attitudes toward AI technologies. Perceived Risk also significantly predicted Perceived Usefulness (H6: β = 0.299, p = 0.014), suggesting that students who feel safer and more secure in using AI are more likely to consider it beneficial for academic tasks.

The results reveal several meaningful relationships involving Attitude toward Use. Attitude significantly influenced both Perceived Ease of Use (H7: β = 0.495, p = 0.003) and Perceived Usefulness (H9: β = 0.370, p = 0.001). This aligns with recent findings in AI-assisted medical consultation research, where emotional perceptions of AI—such as mistrust or doubts about effectiveness—mediate how health literacy shapes attitudes toward AI technologies [63]. These findings highlight how emotional and cognitive responses jointly shape perceptions of usefulness and ease of use.

In contrast, Attitude toward Use did not significantly predict Behavioral Intention (H8: p = 0.795), echoing longstanding behavioral research documenting the inconsistent relationship between attitudes and actual behavioral tendencies. This inconsistency can often be attributed to discrepancies between in-the-moment decisions and later reflections, indicating that retrospective attitudes may not always mirror real-time motivations [64].

The significant relationship between Attitude toward Use and Perceived Usefulness is also supported by existing literature, suggesting that users tend to view functional AI as more useful than social AI, and that perceived usefulness mediates how users assess the realism and value of different AI types [65]. These insights enhance our understanding of how students evaluate AI technologies’ academic relevance.

Perceived Ease of Use significantly predicted Behavioral Intention (H10: β = 0.288, p = 0.009), indicating that the easier AI technologies are to use, the more likely students are to adopt them. This is consistent with previous findings in technology-enhanced learning contexts, where usability and emotional responses mediate the relationship between perceived ease and intention—highlighting the need for intuitive, inclusive, and emotionally supportive digital learning environments [66].

Finally, Behavioral Intention strongly predicted both Student Trust (H12: β = 0.763, p = 0.001) and Acceptance (H13: β = 0.711, p = 0.012), and Acceptance significantly predicted Actual Use (H15: β = 0.561, p = 0.011), emphasizing the centrality of intention and acceptance in shaping actual behavior. However, Student Trust did not predict Actual Use (H14: p = 0.731), indicating that trust alone is insufficient to drive adoption unless accompanied by acceptance or intention.

Overall, the structural model reveals a multifaceted interplay among social, cognitive, emotional, and perceptual factors that together shape students’ AI adoption patterns. The significant and non-significant relationships highlight both direct and indirect mechanisms influencing behavioral outcomes, providing a comprehensive understanding of how AI use develops within higher education contexts.

To enhance the reliability and validity of the measurement model, items with factor loadings below the recommended threshold of 0.50 were removed, consistent with the guidelines of [48]. Although prior research [52] suggests that items with slightly lower loadings may still be retained when they exhibit statistical significance (p < 0.05) and strong theoretical justification, retaining these items in our model negatively affected convergent validity and reduced the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Their inclusion also contributed minimal shared variance with their respective constructs, thereby weakening measurement precision and conceptual clarity. Removing the low-loading items improved the AVE and Composite Reliability (CR) values, strengthened the interpretability of the constructs, and resulted in a more parsimonious and theoretically coherent model. Following these refinements, the final SEM demonstrated acceptable reliability, validity, and overall model fit.

A series of refinements was undertaken to improve the reliability and validity of the measurement model. During the initial assessment, several indicators demonstrated low outer loadings (below 0.50) and cross-loadings on unintended constructs, which compromised convergent and discriminant validity as shown in Table 8. As a result, selected items from Perceived Risk (PR) and Perceived Ease of Use (PE) were removed to enhance the psychometric quality of the final model. Additionally, two constructs, Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Students’ Trust (ST), were excluded after repeated violations of discriminant validity thresholds. Both constructs consistently produced HTMT ratios exceeding 0.90 and failed to meet the Fornell–Larcker criterion, indicating substantial conceptual overlap with related constructs such as Attitude and Perceived Ease of Use. Their removal strengthened the distinctiveness of the remaining constructs and reduced multicollinearity within the model.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 9 presents the reliability metrics of the scales through Cronbach’s alpha values, which vary between 0.678 and 0.804. These values fall within the acceptable range as outlined in the study by [67]. Typically, a Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.7 is considered an indicator of reliability, suggesting that the survey questions consistently measure the same concept. Conversely, lower values suggest inconsistency among the questions, potentially pointing to the measurement of disparate constructs.

Table 9.

Construct validity model.

Table 10 presents the model fit indices based on current SEM reporting standards. In accordance with recommendations by [48] the evaluation focuses on the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with its confidence interval, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), as these indices are considered the most reliable and widely accepted indicators of global model fit. The results show that the model achieves acceptable fit across these criteria: the CFI exceeds the recommended threshold of 0.70, SRMR falls below the 0.08 cut-off, and the RMSEA value, as well as its 90% confidence interval, falls within the range indicative of reasonable approximation error (typically ≤0.06–0.08). Together, these indices confirm that the model appropriately reproduces the observed data without signs of overfitting or underfitting.

Table 10.

Model fit.

Although additional indices such as GFI, NFI, and IFI are reported in Table 10 for completeness, these measures are considered less robust in contemporary SEM practice and should be interpreted with caution. Their inclusion provides supplementary information, but the primary evaluation relies on CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Overall, the set of recommended fit indices supports the adequacy of the structural model for analyzing factors influencing AI use in higher education.

Table 11 illustrates the causal linkage between variables, specifying the nature of their impact as either direct or indirect. A direct effect is observed when a variable directly influences the outcome while holding other variables constant. Conversely, an indirect effect occurs when a variable influences the outcome through one or more intervening variables. The total effect, which amalgamates both direct and indirect impacts, offers a holistic view of the variable interactions. The table further reveals that the overall effect of all variables is statistically significant, evidenced by a p-value of less than 0.05, indicating that the direct impacts are meaningful and the intermediaries are relevant to the study.

Table 11.

Direct, indirect and total effects.

The structural model results also revealed instances where a non-significant direct effect corresponded to a significant total effect. This pattern is expected in models involving mediation. A direct path may appear insignificant when its influence is transmitted primarily through one or more mediators. However, when the indirect pathways are summed, the overall (total) effect becomes significant. To address this and prevent misinterpretation, the manuscript reports bootstrapped confidence intervals for all direct, indirect, and total effects, allowing a clear understanding of how mediated relationships contribute to the final outcomes. This clarification ensures that apparent inconsistencies across tables are appropriately contextualized within the framework of mediation analysis.

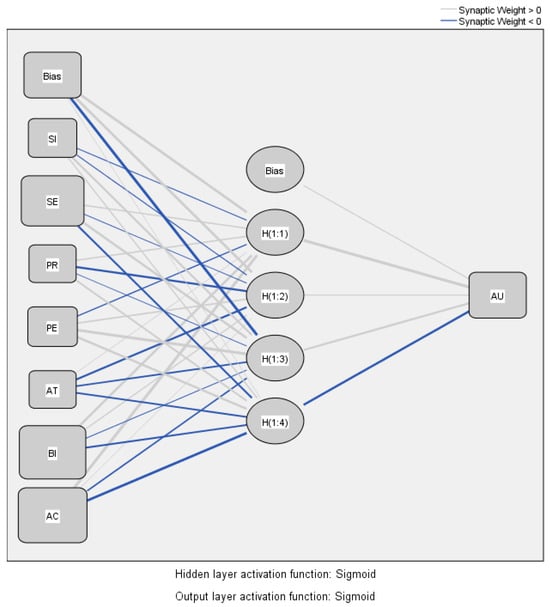

The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) analysis was conducted using an MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) approach in SPSS Neural Network Module, as shown in Figure 3, to complement the SEM results by providing predictive, nonlinear insights into Actual Use (AU). The ANN model utilized the SEM-supported predictors—Social Influence (SI), Self-Efficacy (SE), Perceived Risk (PR), Attitude toward Use (AT), Perceived Ease of Use (PE), Behavioral Intention (BI), and Acceptance (AC)—as input neurons, with a single output neuron representing Actual Use (AU). Prior to model training, all continuous variables were normalized on a variable-wise basis using min–max scaling to the range [0, 1], ensuring numerical stability and preventing scale-dependent bias during weight optimization.

Figure 3.

Final SEM results.

The MLP architecture consisted of one hidden layer containing four neurons, determined through iterative testing to balance model complexity and performance. The sigmoid activation function was applied to both the hidden and output layers due to its suitability for normalized continuous outputs. The model was trained using the default SPSS optimizer (scaled conjugate gradient), with the learning rate automatically adjusted by the software. Regularization was implicitly handled through weight decay, and early stopping was enabled based on the validation performance to prevent overfitting. A fixed random seed (set to 123) ensured reproducibility as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Model of neural network. Origin: created by the authors using data processed through SPSS Statistics.

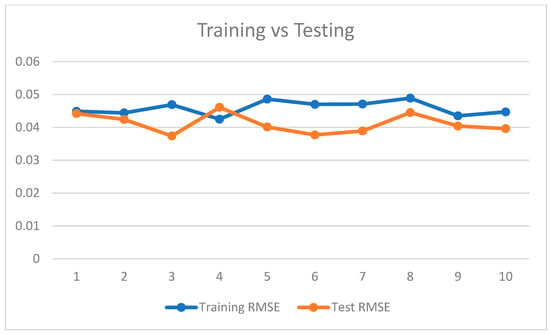

For model validation, the study employed a 10-iteration repeated 80/20 holdout validation scheme, consistent with the procedure implemented by SPSS Neural Network. In each iteration, the dataset was randomly partitioned, with 80% of the observations used for training and the remaining 20% used for testing. This approach differs from standard k-fold cross-validation, in which training occurs on k folds, and testing is performed on the remaining fold. Because the outcome variable (AU) is continuous, no stratification was required during the partitioning process. Repeating the holdout process ten times with different random splits improved the stability of the performance estimates, and the final model performance was based on the average validation error across all iterations.

The precision of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model’s forecasts was assessed by calculating the root mean square error (RMSE) across ten iterations, applying this metric to both the training (comprising 80% of the data) and testing (covering 20% of the data) datasets since the ANN was used for regression and not classification. RMSE was computed as per Equation (1) [68], where it is derived from the sum of squared errors (SSE) and divided by the number of data points (n).

Table 12 illustrates that the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model demonstrates a high degree of precision in mapping the relationships between the input variables and the outcome, as evidenced by the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for both the training and testing datasets. The lower the RMSE values, the higher the model’s predictive accuracy and the better its fit to the data, indicating a superior performance [69]. RMSE values represent the average prediction error between the model’s estimated output and the actual observed values. In regression-based neural network models, lower RMSE values indicate better predictive performance and model generalization. The RMSE values obtained in this study (Training: M = 0.0459; Testing: M = 0.0411) fall well within the range considered highly accurate for normalized continuous outcomes. The similarity between training and testing RMSE further suggests that the ANN model did not overfit and maintained stable predictive performance across independent data subsets as further emphasized in Figure 5.

Table 12.

RMSE values for the ANN model.

Figure 5.

RMSE trend of training vs. testing.

Table 13 provides a detailed overview of the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) configuration used in this study. The model employed a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) architecture designed to complement the SEM analysis by capturing nonlinear interactions among the predictors. Seven input variables, Social Influence (SI), Self-Efficacy (SE), Perceived Risk (PR), Attitude Toward Use (AT), Perceived Ease of Use (PE), Behavioral Intention (BI), and Acceptance (AC), were used to predict the output variable Actual Use (AU).

Table 13.

ANN Table Summary.

The network consisted of a single hidden layer with four neurons, activated using the sigmoid function, which was also applied at the output layer to accommodate normalized continuous outcomes. Training was performed using the Scaled Conjugate Gradient optimizer, and early stopping based on validation loss was applied to prevent overfitting. To ensure reproducibility, the random seed was fixed at 123.

Model validation was conducted using a 10-iteration repeated 80/20 holdout procedure, which produced stable estimates of predictive performance. As shown in Table 13, the ANN achieved low error values across both RMSE metrics, with closely aligned training and testing results, indicating strong generalization capability. These metrics confirm that the ANN effectively modeled the nonlinear relationships among the predictors and provided reliable estimates of students’ actual AI use. RMSE was selected as the primary evaluation metric because the dependent variable was normalized between 0 and 1, allowing RMSE to be interpreted directly on the original scale of the model output. Since RMSE reflects the average magnitude of prediction errors in normalized units, it provides a clear and interpretable measure of predictive accuracy. Therefore, RMSE was sufficient for assessing the ANN model performance in this study.

Table 14 and Figure 6 reveal the significance of seven independent variables across ten different neural networks. The data, normalized for variable importance, highlights that acceptance stands out as the most influential factor in predicting actual usage. This is closely followed by self-efficacy, suggesting that an individual’s belief in their ability to use the system plays a nearly equally vital role. On the other hand, the attitude towards use appears to have a less significant effect on actual usage, with perceived risk having an even lower impact. This analysis underscores the complexity of factors influencing the adoption and effective use of technology, suggesting that while some factors are paramount, others play a comparatively minor role.

Table 14.

Normalized variable relative importance.

Figure 6.

Normalized importance.

Normalized variable importance in Table 14 reflects the scaled contribution of each predictor to the ANN model’s prediction of Actual Use. The importance scores were computed by SPSS through rescaling raw connection weights using the Garson algorithm, resulting in normalized percentages where the most influential predictor is set to 100%. In this model, Acceptance (AC) emerged as the dominant predictor of Actual Use, followed by Self-Efficacy (SE) and Behavioral Intention (BI). Lower importance values for variables such as Perceived Risk (PR) indicate a more limited contribution to the ANN’s predictive accuracy. While ANN cannot infer causality, these rankings provide insight into the relative strength of nonlinear predictive relationships among variables.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight a multifactorial set of determinants shaping students’ acceptance and use of AI technologies in higher education. Although prior studies emphasize the role of trust in technology adoption [4,5], the SEM results in this study indicate that trust did not significantly predict actual use. Instead, the adoption process was primarily driven by social influence, perceived risk, attitude toward use, perceived ease of use, acceptance, and behavioral intention, demonstrating that students’ decisions to use AI tools are shaped more by social and experiential factors than by trust perceptions alone. The significant effects of social influence and perceived risk on attitudes toward AI use align with existing research showing that peer behaviors, institutional cues, and perceived safety strongly shape attitudes toward emerging technologies [6,18]. The influence of social factors on self-efficacy underscores the importance of supportive environments in helping students feel more competent and confident when engaging with AI tools.

The results from the ANN analysis further reinforce the importance of a broader set of predictors by identifying acceptance and self-efficacy as among the strongest contributors to actual AI use. This highlights that students’ perceived capability and willingness to integrate AI technologies into their academic routines play a central role in shaping real behavior. The limited or non-significant relationship between self-efficacy and perceived ease of use suggests that usability perceptions may depend more on contextual conditions, such as institutional support, interface design, or accessibility, than on students’ personal confidence alone [8]. Together, these findings point to an adoption process driven not by trust, but by a combination of social cues, perceived usability, perceived risk, and acceptance, underscoring the need for a more nuanced and ecosystem-oriented understanding of student engagement with AI.

From a sustainability and policy perspective, the results suggest that higher education institutions should prioritize improving usability, strengthening support mechanisms, reducing perceived risks, and fostering positive social environments rather than focusing solely on building trust. Strategies such as transparent communication, inclusive system design, peer-led demonstrations, and institutional guidance can enhance perceived ease of use and acceptance while addressing risk-related concerns [10]. By acknowledging the interplay of these empirically supported factors, educators and policymakers can develop more effective interventions that promote meaningful and sustained adoption of AI technologies in higher education.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the factors influencing the adoption and actual use of AI technologies among higher-education students by integrating Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). The SEM results provide clear empirical evidence that social influence plays a significant role in shaping students’ self-efficacy and perceived risk, both of which contribute to their attitudes and subsequent adoption-related outcomes. Attitude toward AI use demonstrated significant associations with perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, highlighting the importance of students’ evaluations of AI tools in shaping their behavioral responses. Furthermore, behavioral intention was found to have a strong and significant effect on both trust-related perceptions and acceptance, which ultimately predicted students’ self-reported actual use of AI technologies.

The ANN analysis complemented these findings by identifying the predictors that most strongly influence actual use, providing a nonlinear perspective on variable importance. While ANN does not offer causal interpretation, its predictive ranking reinforced the contribution of key SEM-supported variables—including social influence, perceived ease of use, and behavioral intention—by demonstrating their relative importance in forecasting actual use of AI tools. This confirms that integrating ANN with SEM can strengthen the predictive component of technology-adoption research when sample size permits, although the SEM results remain the primary basis for inference.

Some relationships, however, did not emerge as significant. Self-efficacy did not significantly predict attitudes or perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness did not significantly influence behavioral intention. These findings highlight that AI adoption among students is not solely driven by individual confidence or perceived utility, but instead is shaped more prominently by social and experiential factors. This underscores the complexity of the adoption process and the need to consider contextual and interpersonal influences.

Overall, the study provides empirical support for the central role of social influence, perceived ease of use, perceived risk, and behavioral intention in shaping students’ acceptance and actual use of AI technologies. The combination of SEM and ANN offers a more comprehensive understanding of adoption patterns by aligning theory-driven causal testing with data-driven prediction. However, conclusions remain grounded in the statistical evidence provided by the SEM paths and ANN variable-importance results.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The findings of this study offer several actionable implications for educators, administrators, and policymakers seeking to enhance the adoption and effective use of AI technologies in higher education. First, the strong influence of social factors on self-efficacy, perceived risk, and adoption-related outcomes suggests that peer interactions, faculty modeling, and collaborative learning environments play a crucial role in shaping students’ engagement with AI tools. Institutions may therefore consider leveraging peer mentoring, student-led demonstrations, and community-based learning activities to strengthen positive social influence and reduce apprehensions surrounding AI use.

Second, the significant relationships among attitude, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness highlight the importance of designing AI-supported academic systems that are intuitive and supportive of student learning. Training programs and workshops should focus not only on technical skills but also on fostering positive experiences with AI tools to build favorable attitudes. Providing guided tutorials, example-based learning modules, and opportunities for hands-on exploration can help students become more comfortable and confident in using AI for academic purposes.

Third, the strong effect of behavioral intention on acceptance and actual use underscores the need for institutional strategies that cultivate sustained interest and motivation to engage with AI technologies. Policies that encourage responsible and effective AI use—such as clear guidelines, transparency in AI-supported assessments, and integration of AI literacy into the curriculum—can strengthen students’ intentions and support broader adoption. Additionally, the predictive insights from the ANN analysis reinforce the importance of focusing on variables such as social influence and ease of use when designing interventions aimed at improving actual usage rates.

Together, these implications indicate that successful integration of AI in higher education requires not only technological readiness but also targeted efforts to influence attitudes, reduce perceived risks, and strengthen the social and instructional environment in which AI tools are introduced.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Through the use of artificial neural networks (ANN) and structural equation modeling (SEM), the impact of different factors on the adoption of AI technology by higher education students is explored. Several limitations and directions for further research are identified.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, the sample was obtained through convenience sampling and was limited to higher-education students within a single regional context. As a result, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other academic environments, institutional cultures, or demographic groups. In addition, the use of both online surveys and printed questionnaires may have introduced potential response biases. Online participation may have attracted students who were more technologically inclined or more interested in AI, leading to self-selection bias. In contrast, printed questionnaires may have resulted in lower engagement and possible non-response bias. Future research would benefit from employing stratified or multi-institution sampling strategies and more controlled data collection procedures to enhance external validity and reduce potential biases arising from the mode of survey administration.

Second, all variables, including Actual Use (AU), were measured using self-reported survey data. Although participants responded anonymously, self-report measures are inherently susceptible to recall bias, social desirability bias, and perceptual inaccuracies. The study did not have access to objective usage records or digital analytics from AI platforms; therefore, Actual Use reflects perceived use rather than verified behavioral data. Future studies should consider triangulating self-reports with system logs or institutional usage metrics to improve measurement validity.

Third, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer causality among the variables examined. Longitudinal or experimental designs would allow researchers to test whether changes in predictors (e.g., Attitude, Behavioral Intention, Perceived Ease of Use) lead to actual changes in AI adoption over time.

Fourth, although the measurement model was refined to improve reliability and discriminant validity, the removal of several indicators and two constructs may affect the completeness of the theoretical model. This highlights the need for further development and validation of context-specific measurement instruments for AI acceptance in higher education.

Fifth, while the ANN component provided valuable predictive insights, the sample size limits the robustness of more complex neural network architectures. ANN results should therefore be interpreted as exploratory and complementary to SEM rather than definitive. Larger datasets would enable more rigorous hyperparameter tuning, external validation, and more advanced machine learning approaches.

Finally, the rapid evolution of AI technologies means that students’ perceptions, risks, and usage behaviors may change quickly. The findings represent attitudes and behaviors at a specific point in time and may not fully capture emerging patterns as new AI tools and policies are introduced. Future research should incorporate repeated measures or adaptive research designs to monitor the evolution of user perceptions.

To overcome this limitation and more accurately reflect the student body, future research could include a wider and more diverse set of participants across multiple institutions. Additionally, employing alternative analytical techniques or mixed-method approaches could provide contrasting perspectives, even though SEM and ANN already offer valuable insights into the relationships influencing AI acceptance. Exploring different methodologies, such as longitudinal designs, qualitative interviews, or experimental interventions, may further illuminate the complex processes that shape students’ perceptions and behaviors toward AI technologies in higher education. As no platform-level usage logs or system analytics were available in the present study, objective triangulation was not possible; however, this remains an important avenue for future research. Integrating digital traces, system-generated logs, or institutional usage records would improve measurement accuracy, validate self-reported behaviors, and reduce potential common-method bias.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with Philippine national regulations and institutional guidelines, as the research involved minimal risk and the collection of non-identifiable survey data only. Specifically, under the Philippine National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research (2017) issued by the Philippine Health Research Ethics Board (PHREB), studies involving anonymous survey questionnaires with no collection of personal identifiers and no foreseeable risk to participants are considered exempt from ethics review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. No personal identifiers were collected, and all data were used exclusively for academic and research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire, anonymized dataset, data dictionary, and analysis syntax used in this study have been deposited in a DOI-registered repository to ensure traceability and citability. Due to confidentiality and ethical restrictions, the dataset is available under controlled access. Interested researchers may request access through the repository platform, where materials will be provided for academic and non-commercial use subject to approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Koohang, A.; Raghavan, V.; Ahuja, M.; et al. Opinion paper: “so what if chatgpt wrote it?” multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of Generative Conversational AI for Research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu-Ampong, K.; Acheampong, B.; Kevor, M.; Sarfo, F. Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT) in Education: Trust, Innovativeness and Psychological Need of Students. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. The Rhetoric and Reality of Anthropomorphism in Artificial Intelligence. Minds Mach. 2019, 29, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jensen, S.; Albert, L.J.; Gupta, S.; Lee, T. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Student Assistants in the Classroom: Designing Chatbots to Support Student Success. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 25, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, H.; David, P.; Ross, A. Trust in AI and Its Role in the Acceptance of AI Technologies. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 39, 1727–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.; Lockey, S.; Curtis, C.; Pool, J.; Ali, A. Trust in Artificial Intelligence: A Global Study; The University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia; KPMG Australia: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuen, L.; Westmattelmann, D.; Bruckes, M.; Schewe, G. Who earns trust in online environments? A meta-analysis of trust in technology and trust in provider for technology acceptance. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Peterson, R.A. A Meta-analysis of Online Trust Relationships in E-commerce. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, N.N.; Atawneh, S.; Khan, W.A.; Almejalli, K.A.; Alhomoud, A. Using artificial intelligence to predict students’ academic performance in blended learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarab, A.; El Marzouki, A.; Boubker, O.; El Moutaqi, B. Integrating AI in public governance: A systematic review. Digital 2025, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, O.-I.; Corboș, R.-A.; Mișu, S.I.; Triculescu, M.; Trifu, A. The next-generation shopper: A study of generation-Z perceptions of AI in online shopping. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2605–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Lee, K.K. The Ai Generation Gap: Are Gen Z students more interested in adopting generative ai such as chatgpt in teaching and learning than their gen X and millennial generation teachers? Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodway, P.; Schepman, A. The impact of adopting AI educational technologies on projected course satisfaction in university students. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Tu, Y.-F. Factors Affecting the Adoption of AI-Based Applications in Higher Education: An Analysis of Teachers’ Perspectives Using Structural Equation Modeling. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2021, 24, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, T.; Alexander, S.; Firestone, I.J.; Baltes, B.B. Self-efficacy and independence from social influence: Discovery of an efficacy–difficulty effect. Soc. Influ. 2006, 1, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.; Schweiger, E.; Schubert, I. Social influence, risk and benefit perceptions, and the acceptability of risky energy technologies: An explanatory model of nuclear power versus shale gas. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X. Technology acceptance, technological self-efficacy, and attitude toward technology-based self-directed learning: Learning motivation as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 564294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, A.A.; Shateri, K.; Amini, M.; Shokrpour, N. Relationships between academic self-efficacy, learning-related emotions, and metacognitive learning strategies with academic performance in medical students: A structural equation model. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. Perceptions and Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence: A Multi-Dimensional Study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safrida; Yusrita. The influence of trust usability perceived ease of use of financial technology on student behavior intention of economic faculty Uisu Medan. Br. Int. Humanit. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikhart, M.; Al-Obaydi, L.H. Reporting the potential risk of using AI in higher education: Subjective perspectives of educators. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 18, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otermans, P.C.J.; Roberts, C.; Baines, S. Unveiling AI perceptions: How student attitudes towards AI shape AI awareness, usage, and conceptions. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 2025, 8, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Understanding managers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions towards using artificial intelligence for organizational decision-making. Technovation 2021, 106, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-R.; Tseng, H.-F. Factors that influence acceptance of web-based e-learning systems for the in-service education of junior high school teachers in Taiwan. Eval. Program Plan. 2012, 35, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabawy, A.Y.; Cater-Steel, A.; Soar, J. Determinants of perceived usefulness of e-learning systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, V.; Sugiyanto, L.B. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment on behavioral intention to use through trust. Indones. J. Multidiscip. Sci. 2023, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, H.; Tarigan, Z.J.H.; Basana, S.R.; Basuki, R. The effect of perceived security, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness on consumer behavioral intention through trust in digital payment platforms. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendy, F.; Hurriyati, R.; Hendrayati, H. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and Social Influence: Intention to Use e-Wallet. In Proceedings of the 5th Global Conference on Business, Management and Entrepreneurship (GCBME 2020), Bandung, Indonesia, 8 August 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masudin, I.; Restuputri, D.P.; Syahputra, D.B. Analysis of Financial Technology User Acceptance Using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Method. Procedia Computer Science. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 227, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A. Rethinking the intention to behavior link in information technology use: Critical review and research directions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, M.N.A.; Ali, A.S.; Haron, N.H.; Salleh, N. The factors influencing the actual use of mobile learning among students in malaysian university. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2023, 8, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Alamri, M.M.; Al-Rahmi, W. Applying the UTAUT Model to Explain the Students’ Acceptance of Mobile Learning System in Higher Education. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 174673–174686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X. The impact of Public Environmental Concern on environmental pollution: The moderating effect of Government Environmental Regulation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.; Wang, C.; Sadaf, A. Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Internet High. Educ. 2018, 37, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Dodson, S.; Harandi, N.M.; Roberson, N.; Fels, S.; Roll, I. Active learning with online video: The impact of learning context on engagement. Comput. Educ. 2021, 165, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Phang, C.W. Role of instructors’ forum interactions with students in promoting MOOC continuance. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2018, 26, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, M.; Dodson, S.; Harandi, N.M.; Seo, K.; Yoon, D.; Roll, I.; Fels, S. Instructors desire student activity, literacy, and video quality analytics to improve video-based blended courses. In Proceedings of the Sixth (2019) ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, Chicago, IL, USA, 24–25 June 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jou, M.; Lin, Y.T.; Wu, D.W. Effect of a blended learning environment on student critical thinking and knowledge transformation. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.J.; Xie, H.; Wah, B.W.; Gašević, D. Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Im, T. Factors of learner–instructor interaction which predict perceived learning outcomes in online learning environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.K.; Polepeddi, L. Jill Watson: A Virtual Teaching Assistant for Online Education; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme, A. AI and education: The importance of teacher and student relations. AI Soc. 2019, 34, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Tang, J.; Roll, I.; Fels, S.; Yoon, D. The impact of artificial intelligence on learner–instructor interaction in online learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, C.V. The role of the teacher and AI in education. In International Perspectives on the Role of Technology in Humanizing Higher Education; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FLiébana-Cabanillas, V.; Marinkovic, I.R.; de Luna, Z. Kalinic Predicting the determinants of mobile payment acceptance: A hybrid SEM-neural network approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 129, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, M.; Stenlund, H.; Lindahl, B.; Anderson, C.; Weinehall, L.; Hallmans, G.; Eriksson, J.W. Components of metabolic syndrome pre-dicting diabetes: No role of inflammation or dyslipidemia. Obesity 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.Y.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Arditi, D.; Wang, Z. Factors that affect transaction costs in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algi, S.; Abdul Rahman, M.A. The relationship between personal mastery and teachers’ competencies at schools in Indonesia. J. Educ. Learn. 2014, 8, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]