Abstract

Concurrency bugs originate from complex and improper synchronization of shared resources, presenting a significant challenge for detection. Traditional static analysis relies heavily on expert knowledge and frequently fails when code is non-compilable. Conversely, large language models struggle with semantic sparsity, inadequate comprehension of concurrent semantics, and the tendency to hallucinate. To address the limitations of static analysis in capturing complex concurrency semantics and the hallucination risks associated with large language models, this study proposes ConSynergy. This novel framework integrates the structural rigor of static analysis with the semantic reasoning capabilities of large language models. The core design employs a robust task decomposition strategy that decomposes concurrency bug detection into a four-stage pipeline: shared resource identification, concurrency-aware slicing, data-flow reasoning, and formal verification. This approach fundamentally mitigates hallucinations from large language models caused by insufficient program context. First, the framework identifies shared resources and applies a concurrency-aware program slicing technique to precisely extract concurrency-related structural features, thereby alleviating semantic sparsity. Second, to enhance the large language model’s comprehension of concurrent semantics, we design a concurrency data-flow analysis based on Chain-of-Thought prompting. Third, the framework incorporates a Satisfiability Modulo Theories solver to ensure the reliability of detection results, alongside an iterative repair mechanism based on large language models that dramatically reduces dependency on code compilability. Extensive experiments on three mainstream concurrency bug datasets, including DataRaceBench, the concurrency subset of Juliet, and DeepRace, demonstrate that ConSynergy achieves an average precision and recall of 80.0% and 87.1%, respectively. ConSynergy outperforms state-of-the-art baselines by 10.9% to 68.2% in average F1 score, demonstrating significant potential for practical application.

1. Introduction

Driven by the rapid evolution of multi-core processors and distributed systems, concurrent programming has become ubiquitous in modern software development. Developers employ synchronization mechanisms, such as threads, locks, and condition variables to achieve task parallelism. However, the inherent non-determinism in thread scheduling renders software prone to various concurrency bugs, including data races, deadlocks, and atomicity violations [1], which pose serious threats to the stability and security of software systems.

Traditional methods for detecting concurrency bugs are primarily divided into static analysis and dynamic analysis. Dynamic analysis is inherently limited by task execution path coverage. Static analysis, which identifies potential issues without program execution, offers broad coverage but remains challenged by three key issues. First, comprehensive analysis must rely heavily on expert-driven, manually designed rules and complex intermediate representations, limiting their extensibility to multi-language or multi-platform scenarios. Second, the practical applicability of static analysis is constrained by the strict dependency on code compilability and limited customizability. Third, static analysis is further hampered by a high false-positive rate resulting from overly conservative judgments.

Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) have achieved impressive performance in code tasks, including bug detection [2], code generation [3], code completion [4] and code translation [5]. However, LLM-based concurrency bug detection still faces a semantic gap that hinders high-precision results. LLMs struggle with precise localization because models often treat concurrent programs as plain text, failing to capture essential concurrency semantics (synchronization structures and inter-thread timing). Such a semantic deficiency makes LLMs highly susceptible to hallucination. Consequently, the existing literature reveals a critical research gap centered on the inherent limitations of current methodologies. Traditional static analysis offers structural rigor but is hampered by its reliance on manual rules and strict code compilability, while Large Language Models, despite their semantic flexibility, lack the necessary structural awareness and formal verification required for reliable concurrent program analysis. The core unmet challenge is the robust synthesis of these two approaches to achieve both scalability and verifiable efficacy in the detection of complex concurrency bugs.

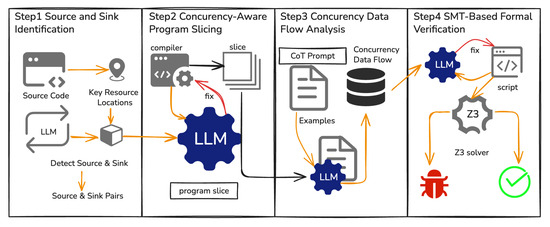

To overcome the aforementioned challenges, this paper introduces ConSynergy, a novel collaborative framework that synergistically integrates the precision of static analysis with the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. ConSynergy systematically addresses the semantic gap and reliability concerns through a four-stage pipeline: (1) shared resource identification, (2) concurrency-aware program slicing, (3) cross-thread data flow analysis, and (4) Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT)-based formal verification.

The detailed workflow begins with concurrency-aware program slicing (Phases 1 & 2). This technique first identifies key concurrency semantic anchors, such as thread creation points and synchronization primitives (e.g., locks, mutexes), using a few-shot prompting method. ConSynergy then compresses lengthy code sequences into minimal, interactive core fragments. These fragments precisely retain the complete concurrency semantics necessary for analysis, effectively alleviating semantic sparsity and focusing the LLM’s attention. Following the slicing, concurrency-aware data flow analysis (Phase 3) is introduced to explicitly model inter-thread interactions. To constrain the LLM’s reasoning and enhance its modeling capabilities, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting is employed. The prompting strategy guides the LLM to meticulously extract concurrent data streams and trace state changes across different threads. Finally, this analysis is complemented by an SMT solver (Phase 4), which formally verifies the sensitive paths and constraints identified during the data flow analysis. The multi-stage verification mechanism acts as a critical filter, formally validating the LLM’s findings to significantly mitigate its hallucination problem and reduce false positives.

To summarize, the core contributions of this paper are threefold:

- A novel LLM-based iterative repair mechanism is introduced, eliminating the dependency on code compilability and thereby enabling effective analysis of incomplete programs during the software development lifecycle.

- The framework incorporates an LLM-based strategy for automated concurrency defect rule generation, addressing the limitation of manual expert involvement and significantly enhancing the method’s universality and transferability across different synchronization models.

- A comprehensive task decomposition and multi-stage verification framework (slicing, annotation, SMT verification) is developed, transforming the exponential path-search problem inherent in traditional static analysis into an efficient constraint-solving problem. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy.

This paper presents a rigorous evaluation of ConSynergy on three representative datasets: DataRaceBench [6], the concurrency subset of Juliet [7], and DeepRace [8]. The experimental results underscore the efficacy of our approach in modeling concurrency semantics and its capability for cross-thread context awareness, achieving substantial improvements over state-of-the-art (SOTA) tools. Furthermore, experiments on real-world open-source concurrency bugs confirm its practical utility and cross-language applicability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Following Section 1, Section 2 surveys the background literature and establishes the research context. Section 3 then details the architecture and mechanisms of the ConSynergy framework. Section 4 presents the setup, results, and comprehensive analysis. Section 5 explores the implications and limitations of our findings, and finally, Section 6 summarizes the key contributions and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Detecting bugs in concurrent programs remains a critical and complex area within program analysis. Researchers have continually proposed diverse methodologies aimed at improving the discovery of concurrency bugs across various dimensions.

2.1. Static Analysis and Dynamic Analysis for Concurrency Bug Detection

Static and dynamic analysis represent the traditional dichotomy for concurrency bug detection. Static analysis methods, such as RacerX [9], identify bugs such as data races and deadlocks by constructing program representations (e.g., Control Flow Graphs (CFG) and lock set analysis) without program execution. More rigorous approaches employ formal methods, primarily model checking, for the verification of concurrent programs [10,11,12,13]. While these static analysis techniques offer superior path coverage, they suffer from a high false-positive rate and the state-space explosion problem due to the inherent complexity of concurrency semantics.

In contrast, dynamic analysis observes and analyzes actual execution paths using techniques such as runtime instrumentation and trace recording. Tools such as ThreadSanitizer [14] and Helgrind [15] accurately locate bugs exposed during operation, resulting in a low false-alarm rate. However, dynamic analysis is inherently limited by task execution path coverage, making it difficult to fully uncover deep-seated concurrency bugs. To address this path coverage insufficiency, recent work has explored advanced techniques. For instance, Zhao et al. [16] proposed a concurrency fuzzing framework (TSAFL) that effectively improves the exploration of thread interleaved spaces through combined inter-thread coverage measurement, periodic scheduling, and multi-objective optimization. Furthermore, machine learning methods have been integrated into dynamic analysis. Suvam Mukherjee et al. [17] introduced a Q-Learning (QL) framework, a learning-based controlled concurrent testing method that adaptively explores scheduling paths through policy learning. These learning-based approaches demonstrate greater potential than fixed heuristics for managing complex concurrent behaviors and improving analysis efficiency. While traditional dynamic analysis relies on execution, its efficiency is often enhanced by optimization techniques. Specifically, a systematic review on nature-inspired metaheuristic methods [18] shows their widespread use in optimizing dynamic analysis workflows, particularly for tasks such as efficient test case generation, test set prioritization, and improving structural coverage.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Bug Detection

General deep learning (DL) methods have made significant advances in security bug detection. Researchers represent source code as token sequences, Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) paths, or program graphs, enabling pattern learning via Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Graph Neural Networks (GNN), and attention mechanisms. Tools such as SySeVR [19], Devign [20], and LineVul [21] show strong performance in common security tasks (e.g., buffer overflows). However, these data-driven approaches typically rely heavily on large-scale, high-quality labeled data and focus primarily on frequent memory bugs. They provide limited support for concurrency bugs, which are both sparse and involve complex semantic dependencies, and often lack interpretability with respect to their root causes.

Efforts to apply DL specifically to concurrency problems, such as data race detection, remain scarce. Zhang Yang et al. [22] combined a CNN-LSTM network with training samples generated by static analysis tools, but this approach inherits a prohibitive overhead due to its dependency on manually annotated static analysis data. Similarly, DeepRace [8], proposed by Tehrani Jamsaz et al., utilizes a CNN to directly model source code. However, its simple structure lacks the capacity to model inter-thread interaction semantics, which results in insufficient interpretability. Overall, existing DL-based methods for concurrency bug detection are constrained by reliance on specific sample construction, limited semantic modeling capability, and poor scalability.

To enhance the semantic modeling of concurrent program, researchers have integrated program analysis techniques. VulDeePecker [23] and SySeVR [19] used static program slicing to extract bug-related feature fragments for neural network classification. While these methods improve semantic focus, they still rely on explicit syntactic patterns and consequently limit generalization. More recently, NS-Slicer [24] combined static program slicing with a pre-trained language model to perform semantic slicing on incomplete code, improving defect localization. Furthermore, DeepDFA [25] demonstrated the benefit of integrating traditional data flow analysis with LLMs to simulate data flow computation via subtask decomposition. This trend confirms that using program slicing and data flow analysis to structure semantic input is an effective strategy for enhancing bug detection performance and interpretability. Beyond mere feature extraction, the integration of optimization algorithms is a critical development in deep learning-based defect prediction. For instance, a two-tier deep and machine learning approach optimized by the Adaptive Multi-Population Firefly Algorithm (AMPFA) [26] demonstrates how metaheuristic techniques can intelligently tune model parameters, achieving significant improvements in prediction accuracy. This trend underscores the importance of algorithmic rigor in enhancing the performance of semantic learning models.

2.3. LLM-Based Bug Detection

Bug detection based on LLMs, including models such as CodeBERT [27], CodeLlama [28], and GPT [29], has garnered significant attention. LLMs leverage pre-trained code data to synthesize and reason about code syntax and semantics, thus demonstrating strong performance in complex tasks. Research has applied them to detection and repair, such as VulBERTa [30], which builds classifiers based on learned code representations, and studies incorporating CoT prompting to significantly enhance bug identification in real-world scenarios [31].

However, LLMs exhibit critical deficiencies when handling complex program structures. Due to their inherent blindness to the underlying control flow, LLMs perform poorly in scenarios involving cross-function calls and multi-threaded interaction. This weakness is particularly pronounced in concurrent programming, where accurately grasping synchronization mechanisms and data dependency relationships remains challenging. For instance, the LLM-based data race detection method proposed by Chen et al. [32], while validating feasibility, proves inferior to specialized static analysis tools in fine-grained variable tracking and defect localization.

To mitigate the aforementioned shortcomings, recent research has focused on integrating static analysis and LLMs by leveraging structured semantic information such as program slicing, dependency paths, and symbolic execution trajectories to augment the contextual input provided to LLMs. The primary aim of this strategy is to improve the models’ perception of program behavior and reasoning accuracy. While methods utilizing program slicing or control flow pruning reduce contextual redundancy, and others convert data flow paths into natural language to guide interpretable reasoning, the field remains in an exploratory phase regarding robust multi-threaded semantic modeling and the explanation of causal chains for concurrency bugs.

Current research combining static analysis and LLMs is primarily categorized into two directions:

- LLM Assisting Static Analysis (SA-Augmentation): Here, the LLM is used to enhance the accuracy and practicality of traditional tools, often by filtering false positives or automating manual steps. Examples include Li et al. [33], who use LLM to interactively filter false positives, and Wang et al. [34], who achieve a compilation-free, customizable analysis process. ABSINT-AI [35] further demonstrated reduced false positives through abstract interpretation enhanced by LLMs.

- Static Analysis Assisting LLM (LLM-Augmentation): This approach uses structural information (e.g., rules or path details) extracted by static analysis to improve the LLM’s understanding and reasoning. DeepVulGuard [36] serves as a key example. It leverages path information from static analysis within an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) environment to assist LLMs. Specifically, it aids in bug localization and the generation of remediation suggestions, showcasing the practical value of this collaboration.

ConSynergy distinguishes itself by adopting the LLM-Augmentation paradigm, but critically extends the approach by providing a concurrency-specific task decomposition strategy that integrates program slicing, CoT reasoning, and formal SMT verification, explicitly targeting the unique challenges of concurrency semantics that prior methods have failed to address systematically.

3. Methodology

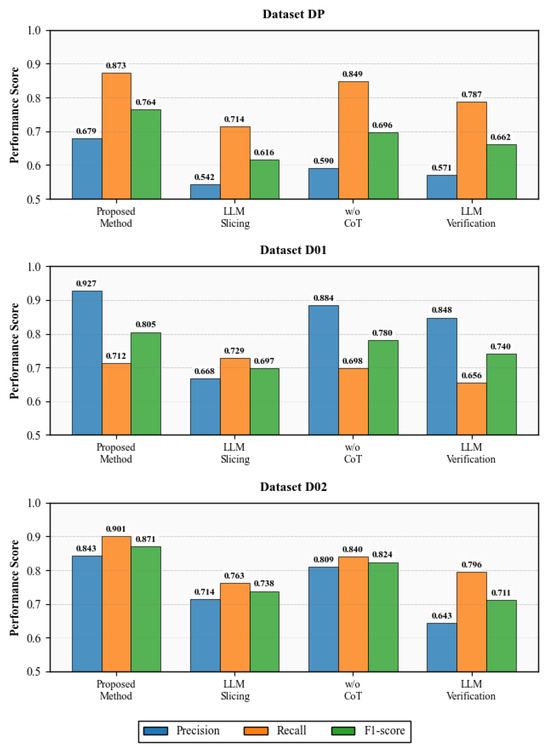

This paper proposes ConSynergy, a novel concurrency bug detection framework that synergistically integrates static analysis with LLM reasoning capabilities. The framework systematically addresses the semantic complexity and non-determinism inherent in concurrent code through a meticulously structured four-stage pipeline, designed to guide LLM comprehension and ensure verification rigor. The complete architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The workflow of ConSynergy.

- (1)

- Source and Sink Identification:This foundational step defines the analytical boundaries for the downstream data flow analysis. This paper formally establishes shared resource accesses as the Source of potential data flows and non-atomic operations (which may lead to data races or deadlocks) as the Sink.

- (2)

- Concurrency-Aware Program Slicing: This paper introduces an iterative slicing technique that leverages traditional static analysis coupled with LLM-driven refinement for enhanced precision. The technique constructs minimal program slices that filter out irrelevant contextual noise while preserving complete concurrency semantic integrity, ensuring the LLM focuses only on critical code segments.

- (3)

- Concurrency Data Flow Analysis: This paper proposes an LLM-based, concurrency-aware approach to explicitly model inter-thread interactions. Within a defined concurrency context, prompts are systematically constructed to guide the LLM, utilizing Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning, to accurately generate inter-thread data flow sets and suspicious paths.

- (4)

- SMT-based Formal Verification: To guarantee the reliability of detection, this phase employs a collaborative verification framework integrating the LLM with formal methods. The suspicious paths identified during data flow analysis are automatically converted into SMT constraint expressions within Python scripts. The constraints are then efficiently solved using the Z3 SMT solver to formally determine the existence of a concurrency bug in the source code.

3.1. Source and Sink Identification

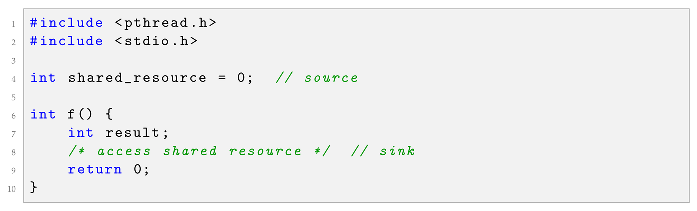

Accurately identifying shared variables, synchronization primitives, and thread entry points constitutes a prerequisite for both data flow analysis and effective concurrency bug detection. We formally define this essential task as Source and Sink Identification, which establishes the analytical boundaries for the subsequent stages. Listing 1 presents a simplified example illustrating the identification of a shared resource (Source) and its access point (Sink).

| Listing 1. Example of shared resource identification. |

|

While the LLMDFA [37] framework focused on sequential data flow analysis, ConSynergy extends this extraction logic to a concurrent context. Our extractor is specifically configured via few-shot prompting to recognize and categorize the following critical concurrency elements:

- Access to Shared Variables (the Source): Identifying potential shared memory locations by analyzing variable read and write operations across different thread contexts.

- Non-Atomic Operations (the Sink): Identifying critical sections where non-atomic modifications to shared resources can cause data races or deadlocks.

- Synchronization Primitives: Recognizing common operations such as explicit lock/unlock statements and inter-thread coordination mechanisms (e.g., wait()/notify()).

- Thread Creation Points: Extracting code structures (e.g., new Thread() and Thread.start()) that define thread creation and entry functions.

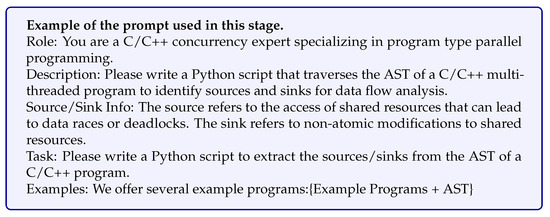

To enhance the LLM’s generalization capability and mitigate initial false positives, this study utilizes a few-shot prompting template that includes example programs with corresponding AST information. This study clearly labels the Source (shared data trigger) and the Sink (concurrent access point) derived directly from the AST nodes.

The process of refining the LLM-based extractor, , employs an iterative self-correction loop to achieve high precision and recall. This iterative refinement procedure is detailed as follows:

- (a)

- Initial Extraction: Given a concurrent program P and a context descriptor D, the process begins by generating an initial extractor, . This extractor leverages example specification assembly code (provided in the prompt) to identify concurrent interaction points from P:where represents the extracted concurrent interaction points, and represents the conditional probability distribution of extracting the interaction points given the program, context, and specification examples.

- (b)

- Iterative Refinement: The extraction algorithm is progressively refined over t iterations. In each subsequent iteration i, the extractor leverages its own output from the preceding round, , as an implicit feedback mechanism to enhance extraction accuracy:This self-correction loop guides the LLM to focus and correct its initial semantic recognition mistakes.

- (c)

- Verification and Convergence: The framework continuously validates the extraction results against the expected specification to assess the accuracy of the identified points:A convergence check is used to determine if the iteration i has reached the convergence state t. A value of signifies that the extractor has achieved the desired precision and recall in identifying concurrent interaction points.

- (d)

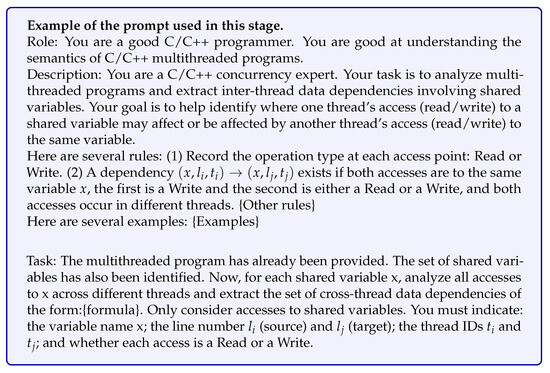

- Final Extractor Generation: After convergence is achieved, the final extractor, , is used to precisely identify all concurrent interaction points from the concurrent program slice S:The set provides the foundational structure—comprising shared variable access, synchronization primitives, and thread context—necessary for the downstream data flow analysis and concurrency modeling. Furthermore, an example of the few-shot prompt used to initialize this extractor is shown in Figure A1.

3.2. Concurrency Program Slicing

To address the issue of semantic sparsity via contextual redundancy reduction, this study proposes a Concurrency-Aware Program Slicing Algorithm (Algorithm 1). The technique identifies and extracts a minimal set of statements semantically critical to concurrent behavior, thereby preserving program structural integrity while reducing contextual noise for LLM processing. A statement is classified as concurrency-critical if it satisfies any of the following criteria:

- It invokes concurrency-related APIs (e.g., thread creation, mutex operations, condition variables, or atomic operations).

- It declares or references variables with concurrency semantics (e.g., pthread_mutex_t, std::atomic).

- It exhibits control or data dependencies (including inter-thread dependencies) with other concurrency-critical statements.

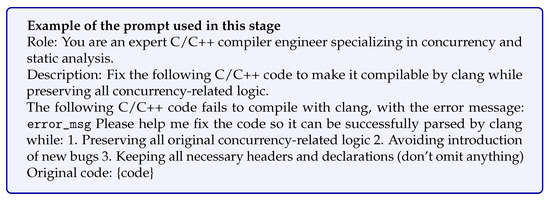

The primary goal of the algorithm is to construct a slice set that captures the complete concurrency and dependency constraints for downstream data flow analysis and LLM inference. The algorithm utilizes Clang’s AST interface for the initial extraction of function calls, variable declarations, and concurrency-related control structures. Crucially, it incorporates an iterative LLM-based repair mechanism to handle uncompilable code, a major limitation of traditional static slicers.

To achieve robust slicing and mitigate compilation errors in concurrent programs, this study employs an LLM-based iterative repair mechanism (Lines 16 in Algorithm 1). This mechanism acts as a compiler front-end, integrating semantic analysis of the concurrency slice with error repair strategies. The process guides the LLM to autonomously correct syntax and structure errors based on the compiler’s error message, E, ensuring that the core concurrency logic is preserved. This iterative correction process is formally described by:

where represents the corrected code after the i-th iteration, is the compilation error message from the previous iteration, and denotes the concurrency-specific semantic constraints provided as part of the prompt to guide the LLM in generating accurate corrections. The prompt template used in this stage to elicit the repair behavior is shown in Figure A2.

| Algorithm 1. LLM-based Concurrency Program Slicing Algorithm |

|

3.3. Concurrency-Aware Data Flow Analysis

Traditional data flow analysis is fundamentally limited in concurrent programming. While intra-procedural analysis tracks data flow within a single thread, and inter-procedural analysis extends the analysis across procedure calls, neither can accurately model the non-deterministic data interactions and state propagation across threads. This limitation stems from the intrinsic difficulty of reasoning about the uncertain control flow introduced by concurrency primitives and thread scheduling.

To overcome this limitation, an LLM-based, thread-aware data flow modeling method is proposed, which explicitly incorporates thread context to support precise concurrency bug detection. Inter-thread data flow () is formally defined as the propagation of a shared variable x defined at program location within thread to a usage location in a different thread . This is formalized as , where . The complete set of inter-thread data flows in a program is represented by:

This study employs the LLM with CoT prompting to model the conditional probability of the existence of an inter-thread data flow. This approach leverages the LLM’s reasoning capabilities to simulate thread interleaving and data propagation, outputting a reasoning result r:

where is the specific context descriptor guiding the cross-thread data flow analysis, provides few-shot examples illustrating valid and invalid data flow paths, and P is the concurrent program slice being analyzed. The output r is the structured reasoning result that determines the existence of a data flow path between the specified access points. The prompt template used to elicit CoT reasoning in this phase is shown in Figure A3.

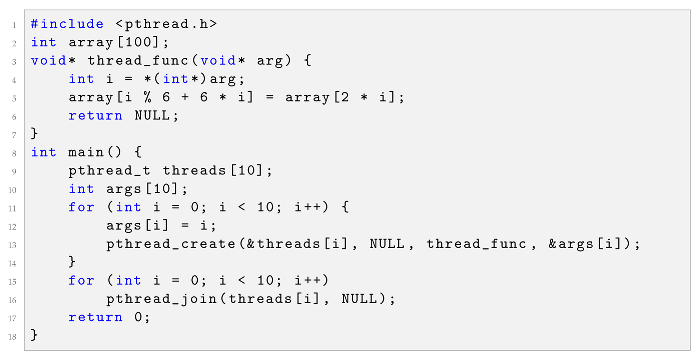

To support bug detection involving complex array accesses (a frequent source of data races), this study extends our thread-aware data flow model by incorporating symbolic index representation. This enables the downstream SMT verification phase to check for index overlap. A write operation by thread to the array a at program location , where is the symbolic index expression, is modeled as a write event :

Similarly, a read operation by thread at with symbolic index is modeled as a read event :

Given the set of all threads T, the array data flow set, , captures potential inter-thread read-write or write-write dependencies:

This set identifies pairs of accesses to the array a across different threads. The crucial distinction here is that and are retained as symbolic expressions, which subsequently serve as constraints for the formal verification step (Phase 4).

As illustrated in Listing 2 (adapted from [38]), multiple threads concurrently access the global array array. In the function thread_func, a thread writes to index and reads from index . Since i is determined by the thread argument, i can range from 0 to 9 across the threads. Due to the absence of synchronization, a potential data race exists when the index written by one thread () overlaps with the index read or written by another thread ( or ). For instance, a data race occurs if (from ) and (from ) are accessed simultaneously. This example demonstrates the necessity of retaining symbolic indices for formal constraint solving in the final verification phase.

| Listing 2. Example of potential data race involving array element access. |

|

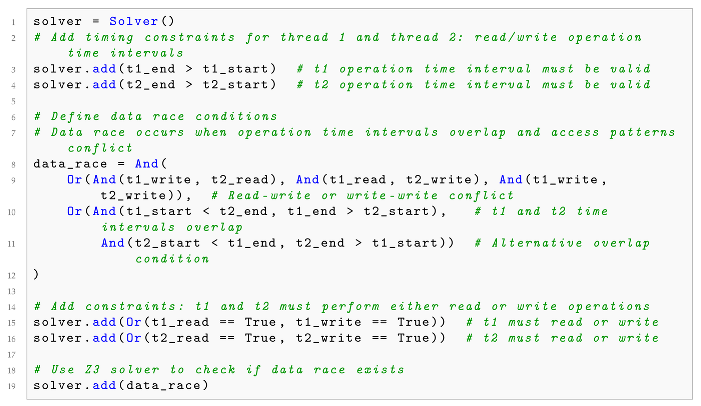

3.4. SMT-Based Formal Verification

Following the construction of thread-aware data flow models, a set of inter-thread data flows is obtained, each potentially corresponding to a feasible concurrent execution path. However, the mere existence of such data flows is insufficient to confirm the presence of concurrency bugs. A true bug arises only when these paths are both feasible under the program’s scheduling and synchronization constraints and violate expected semantic guarantees, such as through data races or unsynchronized shared access.

This study introduces an SMT solver to formally verify the path feasibility and, critically, to control the LLM’s hallucination rate by converting the soft probabilistic predictions into a hard, decidable verification problem. Given a inter-thread data flow path , the SMT verification determines whether an inter-thread schedule exists that allows the definition of x at in to propagate to in for reading or use, without being overwritten or masked by another access. Studies [39,40] have demonstrated the capability of LLMs to automatically generate high-quality SMT formulas. This capability is leveraged to systematically construct complex constraints and uncover deep logical errors.

The following three primary types of SMT constraints are constructed:

- Happens-Before () Constraints: Logical timing variables are introduced for program events. For a write event and a read event , variables and are defined as elements of , representing their execution order. The data flow constraint requires temporal ordering: . Crucially, if the two events are deemed concurrent (a potential data race), the constraints must satisfy: , meaning neither event precedes the other in the partial order.

- Synchronization Constraints: If explicit synchronization primitives (such as locks, unlocks, or barriers) are present, corresponding constraints are established to model mutual exclusion and ordering. For example, if a critical section is protected by lock L, any event attempting to acquire L in thread must be temporally sequenced after the release of L in thread , ensuring .

- Data Race Condition Modeling: A data race is modeled as a logical predicate requiring unsequenced, unsynchronized accesses to the same memory location where at least one access is a write. For array accesses, this involves checking for index overlap across distinct threads. Let be write indices and be read indices for threads and . The array conflict conditions are formalized as:

- Write-Write conflict:

- Write-Read conflict:

- Read-Write conflict:

If any of these index conflicts are satisfied, and the Happens-Before relation is absent (i.e., ), a data race exists.

For the specific array access example generated by the data flow analysis in Phase 3 (Listing 2), the scheduling order and array index conditions are encoded as an SMT satisfiability problem. The verification process involves two key SMT constraints: (1) , and (2) Thread nondeterministic scheduling constraint: . Listing 3 presents the Z3 Python script generated to verify the feasibility of data flow paths.

For a concurrent program that accesses arrays, let the scheduling time for each thread event be a variable . The following SMT constraints are established: (1) Array index conflict constraint:. (2) Thread nondeterministic scheduling constraints:.

| Listing 3. Z3 solver script for concurrent path feasibility verification. |

|

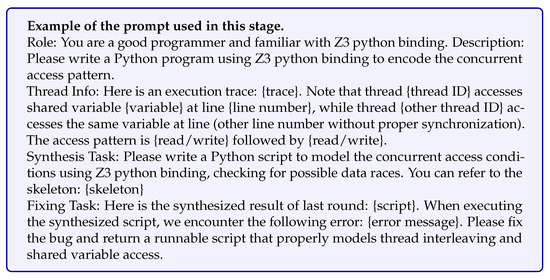

The prompt template guiding the LLM to automatically synthesize the Z3 Python (version 4.15.0.0) script is detailed in Figure A4. The dual-task structure of the prompt (Synthesis Task and Fixing Task) is designed to maximize the reliability of the generated SMT script by encouraging self-correction and enhancing robustness, thereby mitigating potential LLM hallucinations that could lead to erroneous constraints. If the Z3 script execution fails, the LLM is provided with the error message and tasked with refining the constraint logic.

4. Experiments and Results Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

The ConSynergy framework was evaluated against widely-used concurrency bug benchmarks, including DataRaceBench [6], a subset of concurrent bugs from Juliet [7], and the DeepRace dataset [8]. DataRaceBench provides both C and Fortran language data. The C language subset is used for the experiments, which comprises a total of 204 records. The DeepRace dataset comprises three distinct subsets (pthread, OpenMP Private, and OpenMP Critical), collectively ensuring a balanced ratio of positive and negative samples.

The bug detection task is formally modeled as a binary classification task. Performance quantification relies on standard metrics derived from ground truth annotations [41]: True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN). Overall performance is evaluated using Accuracy (Acc), Precision (P), Recall (R), and the F1 score (F1).

The experimental environment utilized a server running Anolis OS 8.6, configured with dual Intel® Xeon® Max 9468 CPUs (96 logical cores), 512 GB of RAM, and a single NVIDIA A800 80 GB GPU. The experiments are structured to investigate the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: Evaluation of LLM Variability: Assessing the detection performance of ConSynergy across different foundational LLMs on the target datasets.

- RQ2: Comparison with SOTA Baselines: Comparative analysis of ConSynergy’s effectiveness against contemporary static and dynamic concurrency bug detection tools.

- RQ3: Ablation Study: Investigating the contribution of the three core architectural components: (a) Concurrency-Aware Program Slicing, (b) Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Data Flow Modeling, and (c) SMT-based Formal Verification.

- RQ4: Real-World Application and Tool Comparison: Evaluating ConSynergy’s capability in detecting bugs within complex, real-world projects compared to established static analysis tools.

4.2. RQ1: Performance in Concurrency Bug Detection

To address RQ1, the multi-stage performance of ConSynergy is evaluated across concurrent subsets of the DataRaceBench and the Juliet Test Suite, employing three distinct SOTA LLMs (GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and Gemini 2.5 Pro). Performance metrics (P, R, ) are quantified at four key stages of the pipeline: extraction and slicing, data flow analysis, SMT constraint generation, and final detection. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of ConSynergy with Different LLMs on Concurrency Bug Datasets.

The initial Extraction and Slicing phase achieved perfect scores (P, R, F1 = 1.0) across all LLMs and datasets. This confirms the efficacy of the LLM-assisted, iterative correction mechanism (Phase 2) in accurately identifying concurrency-critical statements and ensuring the syntactic and semantic integrity of the minimal program slice for downstream analysis.

The initial decline in performance is observed at the Data Flow Analysis stage (Phase 3). On the DataRaceBench dataset, Gemini 2.5 Pro achieved the highest F1 score (), demonstrating high effectiveness in modeling inter-thread data propagation. The high precision scores across all models (e.g., for GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet on Juliet) indicate that the CoT prompting effectively mitigates false positives by meticulously reasoning about data dependencies.

Performance degradation is most noticeable in the downstream SMT Constraint Generation stage (Phase 4), which is directly dependent on the accuracy of the preceding data flow phase. The significant decline in F1 score (e.g., GPT-4o on DataRaceBench dropped from to ) suggests that errors in identifying subtle inter-thread data flows lead to the synthesis of inaccurate or incomplete Z3 constraints. This confirms the cascading dependency of the pipeline, where LLM hallucination during data flow modeling directly impacts the formal correctness required for verification.

In the final Detection phase, the combined error accumulation results in the final metric values. Overall, GPT-4o demonstrates the most robust performance across all phases and datasets, achieving an F1 score of on Juliet and on DataRaceBench. While Claude 3.5 Sonnet exhibits high initial precision in some stages, its lower recall in the final detection stage (e.g., on DataRaceBench) suggests that it failed to identify a larger number of True Positive paths compared to GPT-4o.

In summary, these results validate the overall effectiveness of the LLM-guided pipeline. They also underscore a critical finding: accuracy in multi-stage concurrency detection exhibits strong inter-phase dependency. Robust performance requires maintaining high accuracy in both the probabilistic modeling (Phase 3) and the formal constraint synthesis (Phase 4), as errors accumulate and reduce the final verification precision.

4.3. RQ2: Compared with Baselines

To benchmark the performance of ConSynergy, several representative concurrency bug detection methods were selected, including pre-trained models requiring fine-tuning (CodeBERT [27], GraphCodeBERT [42], and CodeT5 [43]), and two GNN-based approaches (Devign [20] and ReGVD [44]). Additionally, a Zero-Shot LLM baseline was included, where GPT-4o was directly prompted for bug analysis. The dataset was randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test sets at a 7:1.5:1.5 ratio for all trainable models. All comparative experiments were conducted on the same test set. In the DeepRace dataset, DP denotes the pthread subset, while DO1 and DO2 represent the first and second OpenMP subsets, respectively. Experimental parameters for the fine-tuned models were set consistently with prior work [45]. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative experimental results with baseline models.

The proposed ConSynergy method significantly outperforms all baseline approaches in terms of both average Precision () and average F1 score () across the four test datasets. This superior performance confirms that the constrained, multi-stage LLM approach effectively balances sensitivity (Recall) and specificity (Precision) in concurrency bug detection.

Fine-tuned pre-trained models (CodeBERT, GraphCodeBERT, CodeT5) exhibit generally high average Recall (0.877 for CodeT5), a result characteristic of a predictive bias toward the positive (vulnerable) class. This conservative strategy minimizes False Negatives but simultaneously generates an excessive number of False Positives, ultimately compromising the F1 score (CodeT5 average F1 : ).

Graph learning methods (Devign, ReGVD) demonstrate a more balanced performance profile than the fine-tuned LLMs, yet their overall efficacy (ReGVD average F1: ) remains inferior to ConSynergy. This limitation stems from their inherent reliance on the completeness and fidelity of upstream static analysis tools used for graph construction, which often struggle to capture the complex, context-sensitive inter-thread dependencies essential for accurate concurrency modeling.

The Zero-Shot baseline yielded a remarkably high average Recall (0.983), confirming the LLM’s inherent capability to identify potential bug patterns. However, its low average Precision (0.507), driven by an excessive False Positive rate, highlights the risk of unconstrained LLM misclassification. Without the formalized structural and semantic constraints provided by our slicing and SMT verification pipeline, the model tends to over-generalize, resulting in poor practical utility.

A critical practical advantage of ConSynergy is its significantly reduced computational overhead (Table 3). Methods requiring fine-tuning (CodeBERT, GraphCodeBERT, CodeT5) incur substantial training overhead, with CodeT5 requiring over 42 min due to its extensive parameter size. Similarly, the hybrid architecture of ReGVD results in a lengthy training duration (33 min 35 s total).

Table 3.

Time overhead comparison of various methods.

In contrast, ConSynergy requires zero training time, relying exclusively on LLM inference coupled with efficient static analysis. The total inference overhead for ConSynergy is only 15 s, representing an approximately 168-fold reduction compared to the most computationally expensive baseline (CodeT5). This superior efficiency underscores the practicality of integrating ConSynergy into rapid, large-scale concurrent code analysis workflows.

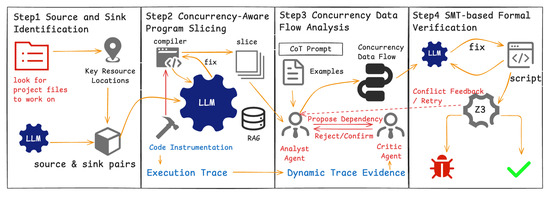

4.4. RQ3: Ablation Study

To rigorously ascertain the contribution of each core component to ConSynergy’s overall efficacy, three critical ablation experiments were conducted. These variants specifically isolate the impact of the framework’s unique hybrid elements:

- LLM Slicing: Replacing our static analysis-assisted program slicing with direct, unconstrained slice generation by the LLM.

- No Chain-of-Thought: Eliminating the structured, step-by-step reasoning prompt during the data flow analysis phase.

- LLM Verification: Substituting the SMT-based formal verification of path feasibility with direct LLM judgment.

Figure 2 illustrates the performance impact of these ablations, using GPT-4o across the three subsets of the DeepRace dataset (DP, DO1, and DO2).

Figure 2.

Ablation experiment results on three subsets of the DeepRace dataset using GPT-4o.

The complete ConSynergy framework exhibits optimal performance, achieving an average Precision (), Recall (), and score () across the test subsets. This superior balance confirms the merit of our hybrid design.

The most severe degradation in performance was observed in the LLM Slicing configuration (average F1 score: ). This sharp decline underscores a fundamental limitation of LLM-only approaches: LLMs struggle to precisely identify and preserve the minimal, yet necessary, program slice required for accurate concurrency analysis. Relying solely on LLM output for slicing leads to the unintentional omission of crucial control flow and data dependency statements pertaining to shared variables, resulting in the loss of critical context irrecoverable in downstream phases.

Replacing the SMT solver with Direct LLM Verification also resulted in a significant performance drop (average F1 score: ). While marginally better than the LLM Slicing variant, this result strongly indicates that LLMs, even when provided with accurately generated data flow paths, lack the formal rigor required for sound verification. Formal constraint satisfaction via SMT is indispensable for guaranteeing the feasibility of the interleaving path, a function that simple LLM probabilistic reasoning cannot reliably perform. The elimination of the structured reasoning prompt, No Chain-of-Thought, resulted in a smaller, yet measurable, performance reduction. This confirms that the explicit CoT guidance enhances the LLM’s internal consistency and improves the fidelity of cross-thread data stream modeling. While CoT is less critical than the slicing or verification mechanisms, its absence diminishes the model’s ability to accurately identify subtle data dependencies, thereby propagating minor errors downstream.

4.5. RQ4: Concurrency Bug Detection in Real Software

Performance was evaluated against real-world Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs). The experimental scope was significantly expanded beyond the initial ConVul dataset [46] to include 16 documented concurrency bugs, incorporating high-profile bugs from 2023 and 2024 in the Linux Kernel.

ConSynergy was benchmarked against four distinct baselines representing different technical paradigms: two industry-standard static analysis tools (Facebook’s Infer [47] and MathWorks’ Polyspace [48]) and two SOTA LLM-based agents (GitHub Copilot [49] and the LangGraph-based ai-code-inspector [50]).

The evaluation results, summarized in Table 4, demonstrate a significant advantage in detection effectiveness for ConSynergy. Our method successfully identified 14 out of 16 bugs (87.5% detection rate), substantially surpassing both traditional static tools and LLM-based agents.

Table 4.

Detection results on real-world vulnerabilities: Comparison with Static Tools and LLM Agents.

In the comparison between LLM-based approaches, GitHub Copilot demonstrated respectable performance, correctly identifying 12 out of 16 bugs, outperforming the autonomous ai-code-inspector agent (8 detected). While the agentic workflow employs iterative critique loops intended to improve reasoning, our experiments suggest that in the specific domain of concurrency, this complexity often leads to “over-reasoning” or hallucinated safety guarantees, resulting in a lower detection rate compared to the direct inference of Copilot. Nevertheless, both pure LLM methods struggled with deep causal chains in the Linux kernel (e.g., CVE-2024-44903) compared to ConSynergy’s neuro-symbolic verification.

Regarding analysis time, traditional static analysis tools proved to be the most computationally efficient. Infer showed the lowest overhead (<1 s), followed by Polyspace (averaging ≈ 11 s). However, this speed came at the cost of accuracy and stability: Infer suffered from a high False Negative rate, while Polyspace frequently failed to complete analysis due to environment dependency issues (marked as “failed”).

Among the LLM-based baselines, ConSynergy proved to be the most efficient, with an average analysis time of 21 s. In contrast, GitHub Copilot incurred a significantly higher latency (averaging ≈ 60 s) due to unconstrained token generation. The ai-code-inspector agent was the most computationally expensive (≈92 s), primarily due to the latency inherent in local model inference (via Ollama) required to execute its iterative generation and reflection workflow. ConSynergy thus represents an optimal trade-off: it provides the detection depth of formal verification while remaining nearly 3× faster than Copilot and 4× faster than autonomous agents.

The handling of recent complex bugs highlights ConSynergy’s adaptability. For instance, in CVE-2024-42111, the race condition involved a subtle use-after-free protected by a complex lock hierarchy. While static tools timed out due to state-space explosion and GitHub Copilot missed the lock release timing, ConSynergy’s sliced SMT constraints correctly identified the feasibility of the race. However, limitations remain: the False Negative in CVE-2017-6346 persists because the static slicing component lacks support for specific C language constructs used in this driver, pointing to future work in enhancing the parser’s language compatibility.

To verify broad applicability, 200 C programs were tested from the SV-COMP ConcurrencySafety benchmark, as shown in Table 5. This allowed comparison not only with Infer and Polyspace but also with direct, unconstrained LLM baselines (GPT, Claude, Gemini).

Table 5.

Performance comparison on SV-COMP ConcurrencySafety benchmark.

On the SV-COMP suite, ConSynergy achieved the highest overall performance metrics (Accuracy , F1 score ).

Static Analysis Comparison: Infer exhibited a substantial False Negative count (FN = 18), as seen in cases like gcd-2.c and per-thread-array-join-counter-race-4.c, where its lightweight nature fails to capture subtle, implicit inter-thread data races. Polyspace, conversely, was characterized by a high False Positive rate (FP = 34), notably in per-thread-array-join-counter.c and thread-local-value-cond.c. In these examples, Polyspace incorrectly flags protected resources, demonstrating a failure to fully resolve the complex semantics of condition variables and mutex release conditions.

LLM Comparison: The unconstrained LLM baselines (GPT, Claude, Gemini) achieved high Recall (average ≈ 0.85) but were severely penalized by high False Positives (average ≈ 55), confirming the illusion problem previously discussed. ConSynergy effectively addresses this trade-off: by employing formal SMT verification, it reduces the False Positive count dramatically (FP = 15) while maintaining high Recall (0.880), thus achieving a superior balance in practical concurrency bug detection.

To further verify the cross-language adaptability of the proposed method and enhance the coverage of test cases, testing was also performed on a Go language concurrent program. The tool presented here can easily support other languages with minimal customization. Currently, Infer and Polyspace do not support Go. This study selected non-blocking samples from GoBench [57] for testing, divided into two subsets: GOREAL and GOKER. The results are shown in Table 6. Since GoBench does not include TN samples, only TP, FP, and FN were used to measure the tool’s performance. The experimental results on GoBench demonstrate that the tool’s performance is comparable to that in C/C++, indicating its capability to detect concurrency bugs in cross-language environments.

Table 6.

Experimental results on GoBench dataset.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The ConSynergy framework represents a significant step forward in neuro-symbolic concurrency bug detection. However, our experimental analysis revealed inherent limitations in the linear pipeline approach, particularly regarding chain dependence, error propagation, and practical scalability. To address these challenges, this section first introduces our enhanced architecture designs, specifically ConSynergy+ and slicing based on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), followed by a rigorous quantitative analysis of the framework’s robustness and scalability limits.

5.1. Enhanced Architecture: ConSynergy+ and Multi-Agent Negotiation

To mitigate the “Chain Dependence” inherent in a linear pipeline, we designed an enhanced architecture, ConSynergy+. As illustrated in Figure 3, this design introduces Multi-Agent Negotiation and an SMT-based Feedback Loop to enable self-correction.

Figure 3.

The architecture of ConSynergy+. While our main experimental results are based on the linear pipeline, this enhanced design incorporates Multi-Agent Negotiation and SMT Feedback Loops to address chain dependence. A preliminary evaluation of this enhanced design is presented in Section 5.1.

Preliminary Evaluation (Case Study): To validate these enhancements, we conducted a targeted case study on 12 samples from SV-COMP ConcurrencySafety benchmark that were incorrectly classified (False Negatives) by the baseline pipeline. We simulated the enhanced workflow by (1) feeding SMT UNSAT cores back to the LLM for re-reasoning, and (2) employing a secondary Critic Agent to validate data flow graphs using execution traces. As shown in Table 7, the enhanced mechanisms successfully recovered 9 out of the 12 (75%) previously missed bugs. This demonstrates that converting the linear pipeline into a closed-loop system significantly mitigates error propagation.

Table 7.

Effectiveness of ConSynergy+ mechanisms on 15 hard failure cases.

5.2. Addressing Slicing Limitations via RAG-Based Rule Injection

A critical failure mode identified in the baseline is “Missing Slicing,” particularly when programs employ ad-hoc synchronization (e.g., using global boolean flags instead of standard condition variables). Static slicers often fail to recognize the implicit cross-thread control dependencies created by these flags. To address this, a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) approach was explored.

A Synchronization Knowledge Base was constructed to map code patterns to their semantic constraints. When potential custom synchronization is detected, relevant rules are retrieved and injected into the slicing prompt. In a feasibility experiment on sample SV-COMP/queue.c, the program uses enqueue_flag and dequeue_flag to coordinate producer (t1) and consumer (t2) threads. The baseline slicer correctly extracted the mutex operations in t2 but failed to capture the logic in t1 that sets dequeue_flag = TRUE. Consequently, the consumer’s critical section appeared unreachable in the slice.

However, with the injected rule “Global flags checked inside critical sections function as synchronization signals; their writers in other threads must be included”), the RAG-augmented slicer successfully identified the dependency between t1 and t2, preserving the complete producer-consumer logic (Table 8). These results confirm that RAG is effective not only for standard APIs but also for capturing subtle, non-standard synchronization semantics.

Table 8.

Comparison of Baseline vs. RAG-Augmented Slicing on Sample SV-COMP/queue.c.

5.3. Quantitative Analysis of Limitations: Chain Dependence and Error Propagation

Despite the promise of enhanced designs, the baseline linear pipeline exhibits quantifiable risks of error propagation. We traced the decision flow across both synthetic benchmarks (DataRaceBench) and industrial projects (SQLite) to quantify this “Recall Decay”. On synthetic benchmarks using GPT-4o, we observed a significant performance decline as data moved through the pipeline stages. Specifically, the F1-score dropped from 0.971 in the data flow phase to 0.786 in the final detection results. This trajectory indicates that approximately 19% of the valid semantic information extracted in the early stages is eventually lost due to the cumulative strictness of the verification chain. Similarly, evaluation on the SQLite codebase revealed that 8.5% of the suspicious paths identified by the LLM were ultimately rejected by the SMT solver as unsatisfiable. Qualitative analysis reveals that this decay stems from the intrinsic rigidity of formal logic. While the SMT stage effectively filters false positives to improve precision, it inevitably rejects valid bugs if the upstream LLM produces imprecise constraints or if the static slice omits subtle macro definitions (e.g., SQLite’s SQLITE_MUTEX_STATIC). Without the feedback loop proposed in ConSynergy+, these near-misses result in irrecoverable false negatives.

5.4. Scalability and Resource Profiling

To evaluate practical scalability beyond synthetic benchmarks, ConSynergy was profiled on SQLite (Version 3.45). A Component-based Analysis strategy was adopted, focusing on the system’s most complex concurrency modules: btree.c (11,587 LOC) and pager.c (7834 LOC). These modules feature deeply nested synchronization logic and extensive macro usage, serving as a comprehensive stress test for the proposed AST slicer compared to the baseline benchmarks (typically 100–300 LOC).

5.4.1. Time and Memory Profiling

Table 9 presents the resource consumption. The baseline metrics are contrasted against the SQLite core modules to demonstrate performance scaling.

Table 9.

Resource Profiling: Benchmarks vs. SQLite Core Modules (Avg. per Slice).

The profiling results demonstrate high efficiency. The increase in slicing time (from 3.2 s to 14.2 s) reflects the computational overhead of parsing significantly larger translation units and resolving SQLite’s complex macro system. Notably, the memory footprint exhibits excellent scalability: while the source code size increases by approximately 50×, the peak memory usage only increases by ∼3× (reaching 320 MB). This low memory footprint implies that ConSynergy is suitable for high-concurrency deployment, allowing multiple analysis instances to run in parallel even on resource-constrained CI/CD runners.

Crucially, the context reduction capability of the slicer is highlighted here. Although the source files are massive, the final slice sent to the LLM only grows moderately (averaging ∼450–600 lines of valid context). This effective filtering ensures that LLM inference time remains manageable (21.5 s), scaling with the complexity of the bug rather than the raw size of the file.

Beyond resource consumption, the generation stability was evaluated. Empirical analysis indicates that approximately 12% of the initial SMT scripts generated by the LLM contain minor syntax errors, such as incorrect Z3 API usage. The fixing task mechanism effectively mitigates this by feeding the interpreter error back to the LLM. This self-correction process incurs a marginal cost, typically involving one additional LLM inference call per failed generation, but successfully recovers script executability in over 90% of cases.

5.4.2. Project-Level Scalability Strategy

A critical concern regarding industrial application is the scalability to 100K+ LOC codebases. ConSynergy addresses this through Translation Unit (TU) Parallelism. Since the analysis operates on independent TUs (or modules), the computational cost grows linearly () with the number of modules rather than exponentially with the total project size. For a 100K+ LOC codebase, independent modules can be analyzed in parallel across distributed workers. Given the low memory footprint (∼320 MB per module), a standard 32 GB server could theoretically process nearly 100 modules concurrently, making industrial-scale analysis highly feasible.

5.5. Future Work

Building on the findings of this study, future research will transcend the limitations of textual slicing by integrating graph-based representations with hybrid neuro-symbolic reasoning. Specifically, static analysis platforms such as Joern [58] or CodeQL [59] will be utilized to construct Code Property Graphs (CPG), extending them with explicit concurrency semantics such as virtual edges representing thread creation, lock dependencies, and shared memory access. This enriched graph structure is intended to serve as a structured context for In-Context Learning, enabling the Large Language Model to reason about concurrency bugs based on topological dependencies and control flow reachability rather than relying solely on linear code fragments.

Furthermore, to compensate for the inherent uncertainty of purely static reasoning, executive trace-based evidence will be integrated into the verification loop. Lightweight dynamic instrumentation will be employed to generate runtime execution profiles, which act as ground-truth anchors to validate the feasibility of thread interleavings inferred by the model. This dynamic evidence will be cross-referenced with the synthesized SMT constraints and graph traversal queries to form a multi-modal triangulation mechanism. By comparing the probabilistic reasoning of the LLM, the logical satisfiability from the SMT solver, and the factual execution paths from dynamic traces, this approach aims to rigorously filter false positives caused by dead code or unreachable concurrency states. Ultimately, by leveraging these graph-enhanced contexts and hybrid verification layers, the framework is expected to evolve into a fully autonomous debugging agent, automating the negotiation loop between semantic reasoning and verification to achieve robust, self-correcting detection.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents ConSynergy, a novel framework for detecting concurrency bugs that integrates the reasoning capabilities of LLMs with the structural precision of static analysis. By combining concurrency-aware static slicing, CoT data flow analysis, and SMT-based formal verification, the hybrid pipeline effectively addresses the limitations inherent in traditional static analysis, such as rule rigidity, and purely LLM-based approaches, notably hallucination and the lack of verifiability.

Extensive evaluations across academic datasets, including DataRaceBench, DeepRace, and Juliet, as well as real-world projects like ConVul and SV-COMP, confirm the superior performance of the framework. ConSynergy achieves an F1 score of 0.867 on the SV-COMP benchmark, demonstrating a robust balance between detection accuracy and the suppression of false positives compared to unconstrained LLM baselines. Crucially, in a comparative study involving complex Linux Kernel bugs, ConSynergy outperforms SOTA generative agents, such as GitHub Copilot and ai-code-inspector, in both accuracy and efficiency. This result validates the necessity of a static neuro-symbolic paradigm over dynamic code interpretation for handling non-deterministic concurrency bugs.

Furthermore, the practical scalability of the framework is corroborated through resource profiling on the SQLite codebase. The results indicate that the component-based slicing strategy maintains a manageable memory footprint even when analyzing industrial-scale modules, with the computational cost scaling linearly regarding project size. Finally, a rigorous analysis of error propagation paves the way for the next-generation architecture, ConSynergy+. By identifying the recall decay characteristic of linear pipelines, this study outlines a clear roadmap for future research, which includes integrating multi-agent negotiation, SMT-based feedback loops, and RAG-augmented slicing to achieve fully autonomous and self-correcting concurrency analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F. and G.L.; methodology, Z.F.; software, Z.F., Y.C. and K.Z.; validation, Y.C. and X.L.; formal analysis, Z.F.; investigation, Z.F.; resources, G.L.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., X.L. and G.L.; visualization, Z.F.; supervision, G.L.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 92582104).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the corresponding repository at: https://github.com/czffzc/ConSynergy.git (accessed on 11 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Prompt Templates

Figure A1.

Source and sink identification prompt template.

Figure A2.

LLM-assisted slicing hint prompt template.

Figure A3.

Data flow analysis prompt template.

Figure A4.

Concurrent path conflict verification prompt template.

References

- Hong, S.; Kim, M. A survey of race bug detection techniques for multithreaded programmes. Softw. Test. 2015, 25, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hao, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Qian, Z. Enhancing Static Analysis for Practical Bug Detection: An LLM-Integrated Approach. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2024, 8, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Dong, Y.; Tao, Y.; Liu, H.; Jin, Z.; Li, G. ROCODE: Integrating Backtracking Mechanism and Program Analysis in Large Language Models for Code Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 47th International Conference on Software Engineering, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 27 April–3 May 2025; pp. 334–346. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Huang, K.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Peng, X. LLMs Meet Library Evolution: Evaluating Deprecated API Usage in LLM-Based Code Completion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 47th International Conference on Software Engineering, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 27 April–3 May 2025; pp. 885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; David, C.; Wang, M.; Paulsen, B.; Kroening, D. Scalable, Validated Code Translation of Entire Projects using Large Language Models. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2025, 9, 1616–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Lin, P.H.; Asplund, J.; Schordan, M.; Karlin, I. DataRaceBench: A Benchmark Suite for Systematic Evaluation of Data Race Detection Tools. In Proceedings of the SC17: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, Denver, CO, USA, 12–17 November 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, T.; Black, P.E. Juliet 1.1 C/C++ and Java Test Suite. Computer 2012, 45, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TehraniJamsaz, A.; Khaleel, M.; Akbari, R.; Jannesari, A. DeepRace: A learning-based data race detector. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Virtual, 12–16 April 2021; pp. 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, D.R.; Ashcraft, K. RacerX: Effective, static detection of race conditions and deadlocks. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, New York, NY, USA, 19–22 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Petri Nets: Theoretical Models and Analysis Methods for Concurrent Systems; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, G. Automatically Transform Rust Source to Petri Nets for Checking Deadlocks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.02754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, S.; Madhusudan, P.; Parlato, G. Model-checking parameterized concurrent programs using linear interfaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, Edinburgh, UK, 15–19 July 2020; pp. 629–644. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Dahlweid, M.; Hillebrand, M.A.; Leinenbach, D.; Moskal, M.; Santen, T.; Schulte, W.; Tobies, S. VCC: A Practical System for Verifying Concurrent C. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Theorem Proving in Higher Order Logics, Munich, Germany, 17–20 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Serebryany, K.; Iskhodzhanov, T. ThreadSanitizer: Data race detection in practice. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Binary Instrumentation and Applications (WBIA ’09), New York, NY, USA, 12 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valgrind-Project. Helgrind: A Data-Race Detector. 2007. Available online: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/cmt-40/Nice/RuleRefinement/bin/valgrind-3.2.0/docs/html/hg-manual.html (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Zhao, J.; Fu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dong, J.; Hong, R. Thread-sensitive fuzzing for concurrency bug detection. Comput. Secur. 2024, 148, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Deligiannis, P.; Biswas, A.; Lal, A. Learning-based controlled concurrency testing. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2020, 4, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshniat, N.; Jamarani, A.; Ahmadzadeh, A.; Kashani, M.H.; Mahdipour, E. Nature-inspired metaheuristic methods in software testing. Soft Comput. 2023, 28, 1503–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, D.; Xu, S.; Jin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. SySeVR: A Framework for Using Deep Learning to Detect Software Vulnerabilities. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2018, 19, 2244–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Siow, J.; Du, X.; Liu, Y. Devign: Effective vulnerability identification by learning comprehensive program semantics via graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, NeurIPS 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 10197–10207. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Tantithamthavorn, C.K. LineVul: A Transformer-based Line-Level Vulnerability Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/ACM 19th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 23–24 May 2022; pp. 608–620. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiao, L.; Dong, C.; Gao, H. Data Race Detection Method Based on Deep Learning. J. Comput. Res. Dev. 2022, 59, 1914–1928. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zou, D.; Xu, S.; Ou, X.; Jin, H.; Wang, S.; Deng, Z.; Zhong, Y. VulDeePecker: A Deep Learning-Based System for Vulnerability Detection. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, 18–21 February 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadavally, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Nguyen, T.N. A Learning-Based Approach to Static Program Slicing. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2024, 8, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhoek, B.; Le, W.; Gao, H. Dataflow Analysis-Inspired Deep Learning for Efficient Vulnerability Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2022; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Villoth, J.P.; Zivkovic, M.; Zivkovic, T.; Abdel-salam, M.; Hammad, M.; Jovanovic, L.; Simic, V.; Bacanin, N. Two-tier deep and machine learning approach optimized by adaptive multi-population firefly algorithm for software defects prediction. Neurocomputing 2025, 630, 129695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Guo, D.; Tang, D.; Duan, N.; Feng, X.; Gong, M.; Shou, L.; Qin, B.; Liu, T.; Jiang, D.; et al. CodeBERT: A Pre-Trained Model for Programming and Natural Languages. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.08155. [Google Scholar]

- Rozière, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.; Adi, Y.; Liu, J.; Remez, T.; Rapin, J.; et al. Code Llama: Open Foundation Models for Code. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12950. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, O.A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A.; et al. GPT-4o System Card. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, H.; Maffeis, S. VulBERTa: Simplified Source Code Pre-Training for Vulnerability Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padova, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ceka, I.; Qiao, F.; Dey, A.; Valechia, A.; Kaiser, G.E.; Ray, B. Can LLM Prompting Serve as a Proxy for Static Analysis in Vulnerability Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ding, X.; Emani, M.K.; Vanderbruggen, T.; Lin, P.H.; Liao, C. Data Race Detection Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the SC ’23 Workshops of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Network, Storage, and Analysis, Denver, CO, USA, 12–17 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Hao, Y.; Qian, Z. Assisting Static Analysis with Large Language Models: A ChatGPT Experiment. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, X. LLMSA: A Compositional Neuro-Symbolic Approach to Compilation-free and Customizable Static Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.14399. [Google Scholar]

- Gumilar, K.E.; Wardhana, M.P.; Akbar, M.I.A.; Putra, A.S.; Banjarnahor, D.P.; Mulyana, R.S.; Fatati, I.; Yu, Z.Y.; Hsu, Y.C.; Dachlan, E.G.; et al. Artificial intelligence-large language models (AI-LLMs) for reliable and accurate cardiotocography (CTG) interpretation in obstetric practice. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 27, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhoek, B.; Sivaraman, K.; Gonzalez, R.S.; Mohylevskyy, Y.; Moghaddam, R.Z.; Le, W. Closing the Gap: A User Study on the Real-World Usefulness of AI-Powered Vulnerability Detection & Repair in the IDE. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 47th International Conference on Software Engineering, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26 April–6 May 2025; pp. 2650–2662. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Su, Z.; Xu, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, X. LLMDFA: Analyzing dataflow in code with large language models. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS ’24), Red Hook, NY, USA, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.; Mahmud, Q.I.; Jannesari, A. Data Race Satisfiability on Array Elements. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on OpenMP, Charlotte, NC, USA, 1–3 October 2025; pp. 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Meng, R.; Duck, G.J. Large Language Model Powered Symbolic Execution. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2025, 9, 3148–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, K.; Chen, A.R.; Li, G.; Jin, Z.; Huang, G.; Ma, L. Python Symbolic Execution with LLM-powered Code Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.09271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ye, G.; Tang, Z.; Tan, S.H.; Huang, S.; Fang, D.; Feng, Y.; Bian, L.; Wang, Z. Combining Graph-Based Learning with Automated Data Collection for Code Vulnerability Detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 1943–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, S.; Feng, Z.; Tang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Duan, N.; Yin, J.; Jiang, D.; et al. GraphCodeBERT: Pre-training Code Representations with Data Flow. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Joty, S.R.; Hoi, S.C.H. CodeT5: Identifier-aware Unified Pre-trained Encoder-Decoder Models for Code Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the EMNLP. Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 8696–8708. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.A.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Nguyen, V.; Le, T.; Tran, Q.H.; Phung, D. ReGVD: Revisiting graph neural networks for vulnerability detection. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 44th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings (ICSE ’22), New York, NY, USA, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wu, L.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Liu, M. Investigating Large Language Models for Code Vulnerability Detection: An Experimental Study. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhu, B.; Meng, R.; Yun, H.; He, L.; Su, P.; Liang, B. Detecting concurrency memory corruption vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the 2019 27th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2019), New York, NY, USA, 26–30 August 2019; pp. 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta Platforms, Inc. Infer Static Analyzer. [EB/OL]. 2025. Available online: https://fbinfer.com/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- MathWorks. Polyspace Static Analysis Tool. In Polyspace Products Provide Static Analysis and Code Verification for C, C++, and Ada Code; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub; OpenAI; Microsoft. GitHub Copilot: Your AI Pair Programmer. AI-Powered Code Completion and Chat Assistant with Agent Mode. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/features/copilot (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Nehru. AI Code Inspector. Automated Code Debug Tool with LangGraph and Ollama. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/nehru/ai-code-inspector (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2023-31083. 2023. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2023-31083 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2024-42111. 2024. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-42111 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2024-44941. 2024. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-44941 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2024-49903. 2024. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-49903 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2024-50125. 2024. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-50125 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NVD. CVE-2024-57900. 2024. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-57900 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yuan, T.; Li, G.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Xue, J. GoBench: A benchmark suite of real-world go concurrency bugs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO ’21), Virtual, 27 February–3 March 2021; pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, F.; Golde, N.; Arp, D.; Rieck, K. Modeling and Discovering Vulnerabilities with Code Property Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Jose, CA, USA, 18–21 May 2014; pp. 590–604. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub. CodeQL Documentation. Available online: https://codeql.github.com/docs/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).