The AI-Powered Healthcare Ecosystem: Bridging the Chasm Between Technical Validation and Systemic Integration—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

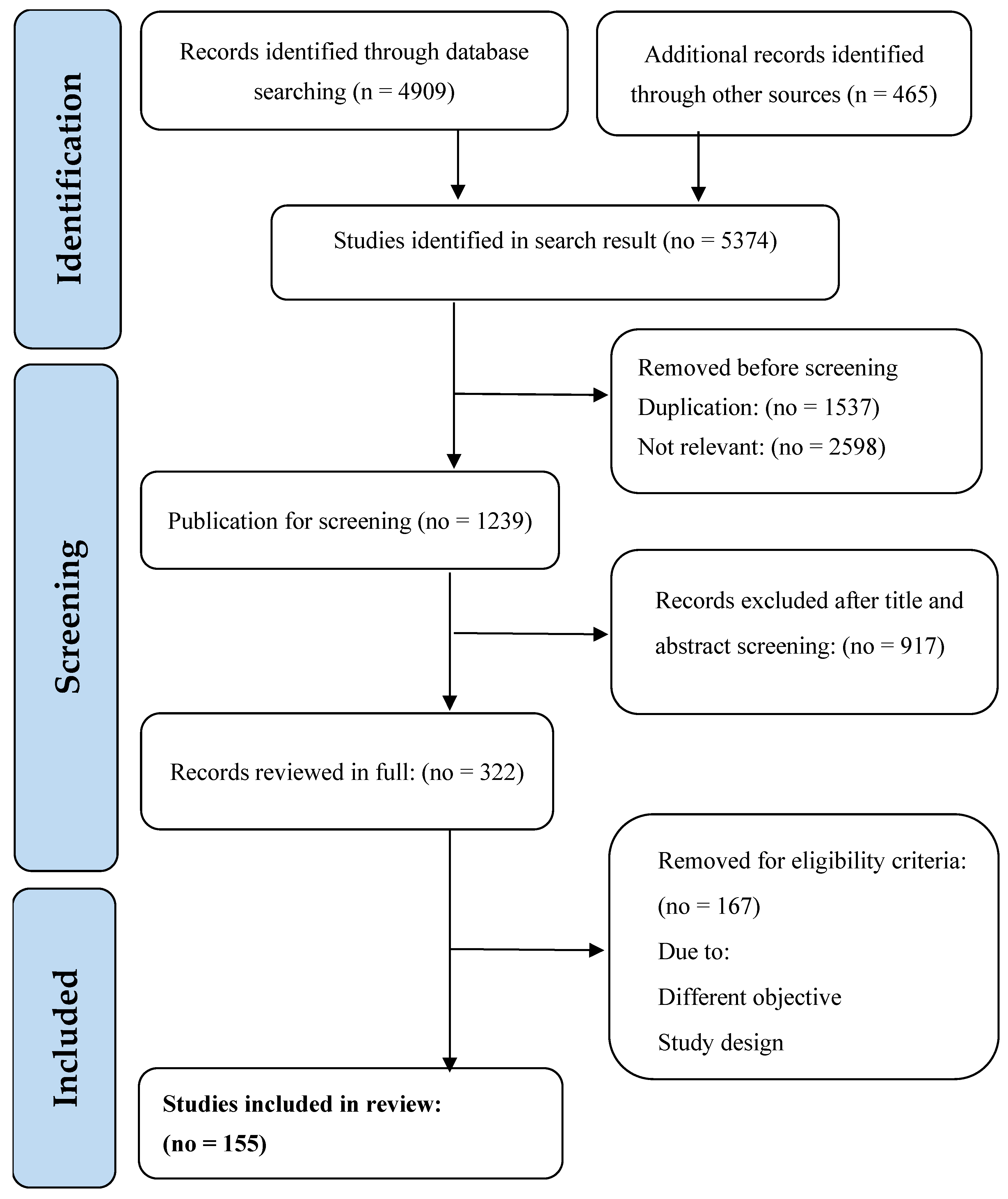

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

2.9. Limitations

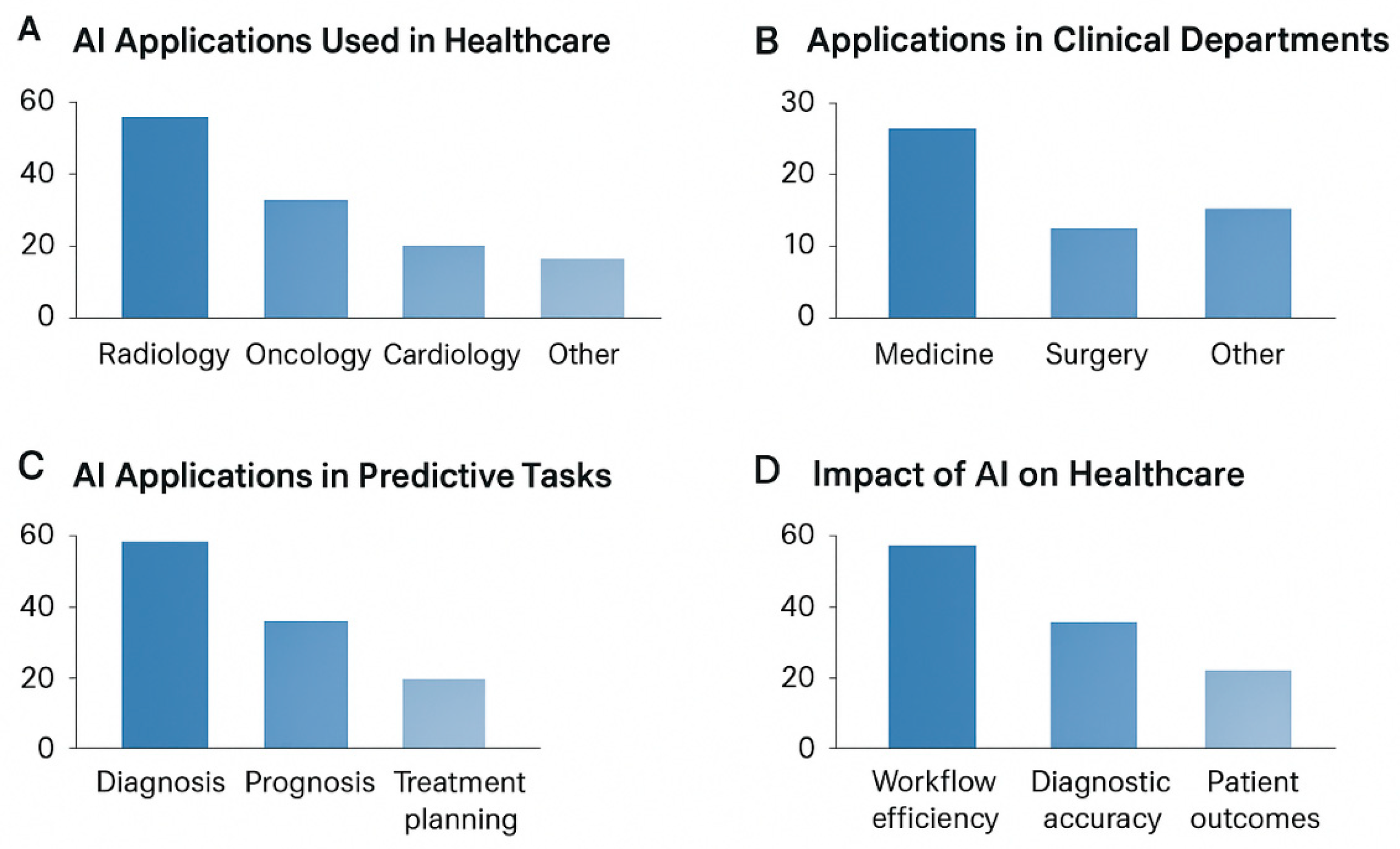

3. Results

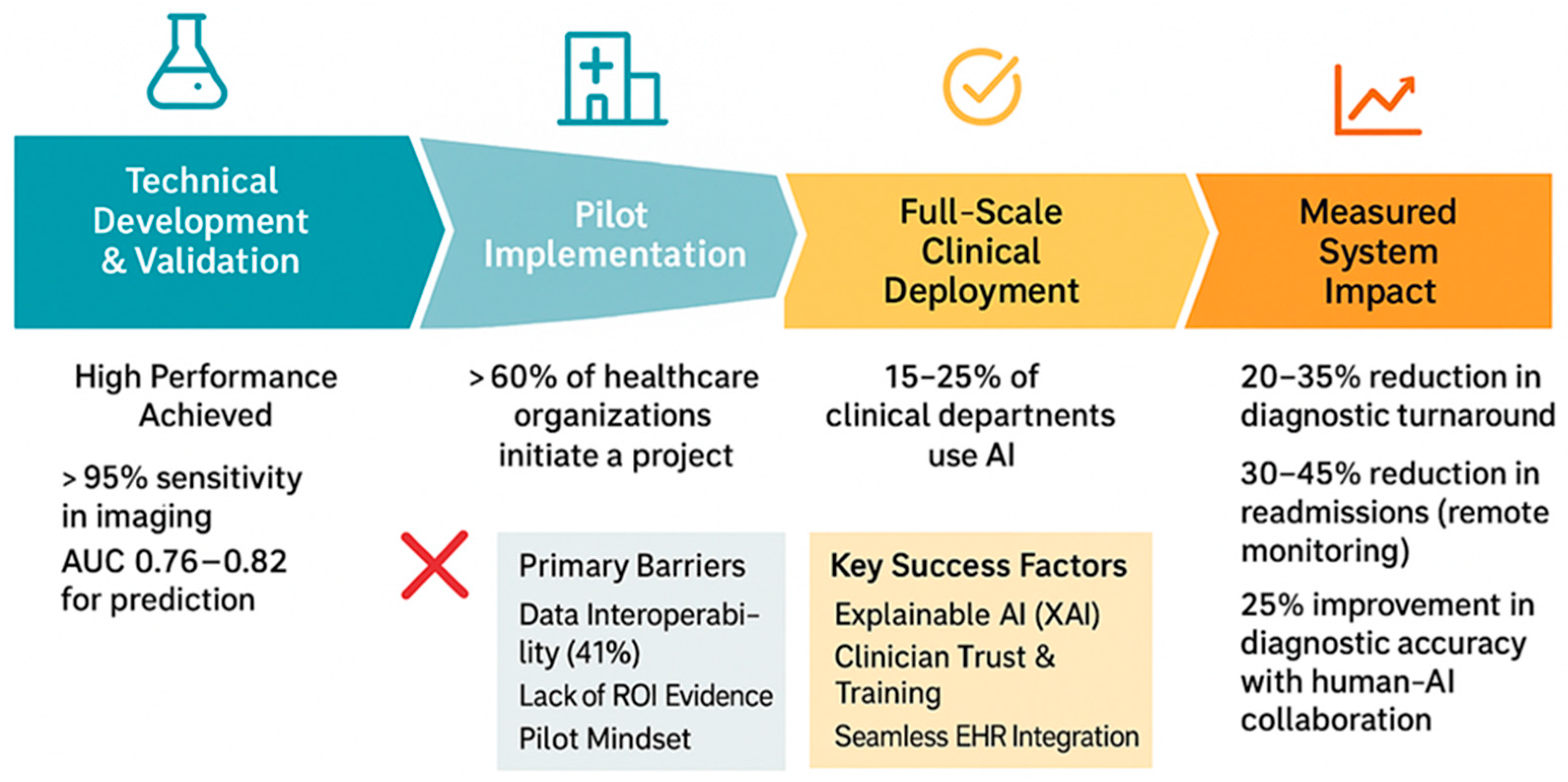

3.1. Technical Performance and Clinical Validation

3.2. Implementation Outcomes and Healthcare System Impact

3.3. Human–AI Interaction and Workforce Integration

3.4. In-Depth Case Studies and Technical Analyses

- Success Factors: Workflow integration that reduces diagnostic turnaround time by 20–35% without disrupting clinical routine is a consistent theme in successful implementations [14,41]. The “triage assistant” model, where AI flags cases but leaves final diagnosis to clinicians, aligns with the observed preference for “human near the loop” approaches [44].

- Context: A multi-hospital US health system invested in a machine learning platform to predict patient readmission risk.

- AI Solution: A complex ensemble model using EHR data.

- Root cause of failure:

- Interoperability challenges: The finding that over 50% of implementations face interoperability issues [46] manifests in failures where models require structured data fields that are inconsistently populated across different EHR systems.

- Outcome: The project was decommissioned after a 12-month pilot, representing a significant financial and operational loss. Numerical values originate from institutional reports and peer-reviewed implementation studies, as annotated in Table 1.

3.5. Regulatory Compliance and Quality Assurance

3.6. Ethical Considerations and Patient Perspectives

3.7. Emerging Applications and Future Directions

3.8. Methods and Technological Approaches

3.9. Applications Across Clinical Domains

3.10. Challenges in AI Adoption

3.11. Legal and Governance Dimensions

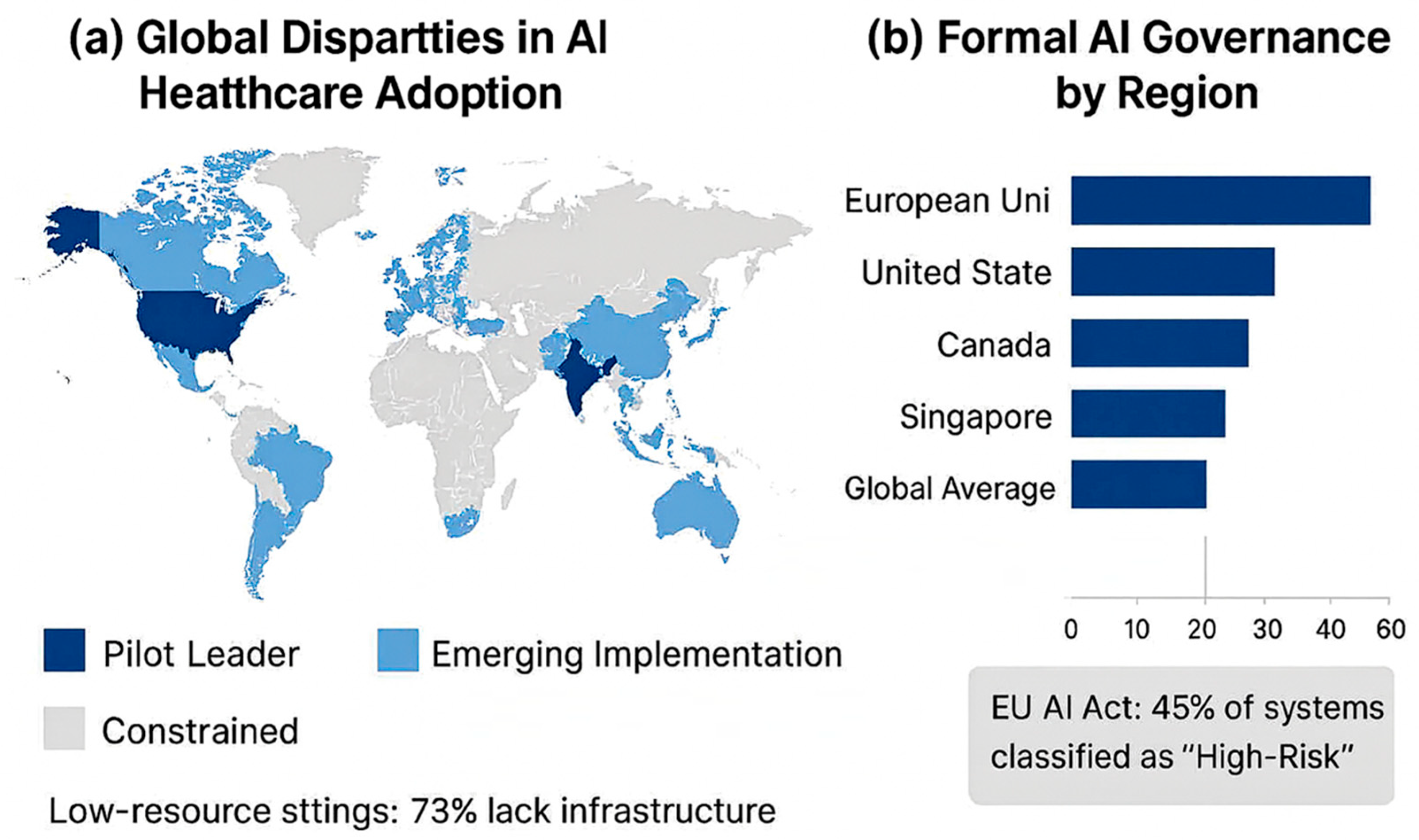

3.12. Regional and System-Specific Insights

3.13. Stakeholder Perceptions, Adoption, and Operational Impacts

3.14. Evaluation, Validation, and Limitations

| Domain | Metric/Outcome | Numerical Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical imaging | Classification accuracy for dermatology AI | Comparable to board-certified dermatologists | [1] |

| Sensitivity for malignant melanoma detection | >95% | [1] | |

| Radiology diagnostic accuracy | 92–98% | [2,3,4] | |

| Pathology | Interpretation time reduction | 30–50% | [3,5] |

| Diagnostic concordance | >96% | [3,5] | |

| Natural language Processing (NLP) | F1 score for entity recognition | 0.85–0.92 | [2,6] |

| Predictive modeling | Hospital readmission AUC | 0.76–0.82 | [7,8] |

| Genomics | Variant classification accuracy | 85–90% | [9,10] |

| Implementation & workflow | Adoption in clinical departments | 15–25% | [11,12,13] |

| Adoption by specialty: Radiology | 42% | [11,12,13] | |

| Adoption by specialty: Pathology | 38% | [11,12,13] | |

| Adoption by specialty: Cardiology | 31% | [11,12,13] | |

| Diagnostic turnaround time reduction | 20–35% | [14,15,16] | |

| Workflow efficiency improvement | 15–25% | [14,15,16] | |

| Cost savings via AI | 10–20% | [15,19] | |

| Billing error reduction | 25–40% | [20,21] | |

| Claims processing time reduction | 50–60% | [20,21] | |

| Hospital readmission reduction (remote monitoring) | 30–45% | [15,19] | |

| Human–AI interaction | Physician willingness for AI diagnostics | 68% | [24,25,26] |

| Physician trust in AI treatment recommendations | 35% | [24,25,26] | |

| Nursing staff adoption of AI monitoring | 45% | [27,28,29] | |

| Improvement in clinical deterioration detection | 72% | [27,28,29] | |

| AI literacy improvement through training | 40–55% | [30,31] | |

| Diagnostic accuracy improvement with AI support | 25% | [32,33,34] | |

| Regulatory & quality assurance | FDA clearance of AI applications | 23% | [37,38] |

| EU high-risk classification of AI systems | 45% | [39,40] | |

| RCTs meeting complete AI reporting standards | 32% | [41,42] | |

| Algorithm performance drift (12 months) | 15% | [27,43] | |

| Performance disparity across demographics | >10% in 28% of models | [47,48,49] | |

| Patient & ethical perspectives | Patient acceptance of AI | 52–78% | [50,51,52] |

| Patients unwilling to share full history | 45% | [53,54] | |

| Increase in AI-related ethics protocol submissions | 35% | [55,56,57] | |

| Health equity performance gaps | >5% in 40% of AI applications | [58,59,60] | |

| Patient satisfaction improvement via patient-centered design | +28 points | [61,62] | |

| Emerging applications | Generative AI accuracy in documentation | 60% | [66,67,68] |

| Reduction in physician typing time | 40% | [66,67,68] | |

| Large language model concordance with specialists | 75% | [68,69,70] | |

| Drug discovery preclinical time reduction | 30–40% | [71,72] | |

| Drug candidate success rate increase | 25% | [71,72] | |

| Blockchain-AI data security improvement | 50% | [54,73] | |

| Federated learning data transfer reduction | 80–90% | [74,75] | |

| Clinical specialty applications | IVF embryo selection accuracy | 85% | [92,93] |

| Cardiovascular predictive sensitivity | 78–92% | [94] | |

| Diabetes HbA1c reduction | 0.5–1.2% | [95] | |

| Critical care decision-making time reduction | 22→15 min per case | [143] | |

| Machine learning disease progression prediction accuracy | 91.2% | [144] | |

| ChatGPT-based risk stratification alignment | 87% | [146] | |

| Manual chart review reduction via AI | 40–55% | [147] | |

| Administrative delay reduction | 15–20% | [148,149] |

| Domain/Aspect | Metric/Outcome | Numerical Result/Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global adoption | Healthcare organizations initiating ≥1 AI project | >60% | [139] |

| Hospital workflow integration | 20–45% | [136] | |

| AI implementations across 38 countries | 72 projects | [140] | |

| Pilot program concentration in high-income countries | 64% | [86] | |

| Regional adoption | Canada: hospitals initiating AI pilots | 59% | [125,126,127] |

| Canada: hospitals fully scaling AI | <15% | [125,126,127] | |

| Singapore: AI-enabled medical devices | 18 devices | [122] | |

| India: clinicians reporting insufficient AI training | 62% | [128] | |

| Low-resource settings: facilities lacking reliable internet | 73% | [129] | |

| Global North vs Global South publications | 91% vs. 9% | [130,131] | |

| UK doctors expressing ethical concerns about AI reliance | 64% | [132,133] | |

| Workforce & stakeholder perceptions | Clinicians prioritizing interpretability and safety | Majority | [134] |

| UK clinicians supporting AI for diagnostics | 71% | [132] | |

| UK clinicians endorsing unsupervised AI decision-making | <30% | [132] | |

| Implementations maintaining “human near the loop” | 82% | [44] | |

| Workforce priorities: training, infrastructure, ethical clarity | 61%, 55%, 48% | [104] | |

| Governance & regulatory | Countries with formal AI governance structures | 27% | [113] |

| Regulatory uncertainty pausing AI projects | 42% | [152] | |

| Governance challenges unresolved globally | 72% | [123,124] | |

| Legal gaps identified in the US (privacy, liability, malpractice) | 13 gaps | [114] | |

| EU GDPR compliance issues identified | 21 issues | [115] | |

| Hospitals implementing structured frameworks with transparency, accountability, fairness, human oversight | Reported 30% higher stakeholder trust | [151] | |

| Ethical & implementation challenges | Institutions lacking formal AI bioethics policies | 68% | [150] |

| AI projects affected by ethical concerns, algorithmic biases, interpretability | 62% | [150] | |

| Clinicians concerned about reliability and interpretability | 34% | [154] | |

| Scalability challenges in low-resource or legacy systems | >50% of projects | [139,152] | |

| Reproducibility across external datasets | <35% of AI models | [100] | |

| Workforce fear of job displacement | 43% | [102] | |

| Workforce viewing AI as supportive | 58% | [102] | |

| Digital literacy training prioritized | 61% | [104] | |

| Ethical dilemmas: informed consent gaps, accountability disputes, liability ambiguity | 36% informed consent gaps | [106,107,108,109] | |

| Open datasets available for independent validation | <10% | [111] |

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| EU | European Union |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| [tiab] | Title/abstract |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

Appendix A

| Search Component | Keywords/MeSH Terms | Field Tags | Boolean/Logic | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population/Setting | “Health”, “Healthcare”, “Medical”, “Clinical”, “Patient”, “Clinician”, “Hospital”, “Primary care” | [tiab], [Mesh] | OR combined | Captures all relevant healthcare populations and clinical settings where AI may be applied. |

| Intervention/Exposure | “Artificial Intelligence”, “Machine Learning”, “Deep Learning”, “Natural Language Processing”, AI, ML, “neural network”, “predictive analytics”, “Decision support” | [tiab], [Mesh] | OR combined | Includes all AI-related technologies and applications relevant to healthcare. |

| Comparison/Intervention context | “Intervention”, “Application”, “Implementation”, “Tool”, “System” | [tiab] | OR combined | Identifies studies describing practical AI applications or interventions in healthcare. |

| Outcomes | “Outcome”, “Effectiveness”, “Accuracy”, “Performance”, “Quality of care”, “Efficiency” | [tiab] | OR combined | Captures studies reporting measurable AI outcomes relevant to clinical or health system performance. |

| Date restriction | 2000–2025 | [Date–Publication] | – | Focuses on contemporary evidence reflecting modern AI applications. |

| Combined search | Population AND Intervention AND Comparison AND Outcomes AND Date | – | AND between main components | Ensures retrieval of studies that meet all PICO elements while maintaining sensitivity. |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Author(s) & Year | Study Design | Population/ Setting | AI Intervention/Focus | Comparison | Outcome(s) Assessed | Quality Assessment Tool | Risk of Bias/Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hodges, 2025 [27] | Review | Global health workforce | Skill distortion due to AI | Non-AI workforce models | Workforce displacement, task shifting | CASP | Moderate–High |

| Starr et al., 2023 [29] | Cross-sectional workforce study | Nursing workforce across multiple countries | Workforce readiness for AI adoption in nursing | None (descriptive) | Skills gaps, readiness levels, barriers | STROBE | Moderate |

| Areshtanab et al., 2025 [30] | Systematic review | Global nursing settings | Readiness of nurses for AI integration | Traditional care workflows | Knowledge, barriers, readiness | AMSTAR-2 | Moderate |

| Shinners et al., 2023 [42] | Scoping review | High-, middle-, and low-income countries | AI in nursing practice | Manual decision processes | Role evolution, access disparity | JBI Scoping Review Checklist | Low |

| Shinners et al., 2020 [43] | Multi-country survey | Nurses in 11 countries | AI adoption in nursing | None | Utilization, perceptions, disparities | STROBE | Low–Moderate |

| Brault & Saxena, 2021 [47] | Conceptual analysis | Global populations | Algorithmic bias & governance | Standard ethical models | Bias sources, fairness challenges | CASP Qualitative | High |

| Rashid et al., 2024 [48] | Systematic review | Global health systems | Ethical concerns in medical AI | Traditional ethics models | Bias, autonomy, transparency | AMSTAR-2 | Moderate |

| Kritharidou et al., 2024 [49] | Comparative review | Clinical AI across multiple regions | Equity in AI clinical implementation | Non-AI clinical pathways | Disparities in performance | CASP | Low–Moderate |

| Esin et al., 2024 [50] | Cross-sectional | General population, Turkey | Public attitudes toward AI | None | Trust, acceptance, perceived risk | STROBE | Low |

| Witkowski et al., 2024 [51] | National survey | Poland | Public trust in AI systems | Non-AI technologies | Security perception, trust levels | STROBE | Low–Moderate |

| Syed et al., 2024 [52] | Survey | Saudi Arabia | Awareness of AI among adults | None | Knowledge score, usage likelihood | STROBE | Moderate |

| Khalid et al., 2023 [53] | Systematic review | Global healthcare | Blockchain-enabled privacy protection for AI | Conventional security methods | Privacy capability, decentralization outcomes | AMSTAR-2 | Moderate |

| Ratti et al., 2025 [57] | Policy review | International | Global governance of health AI | Existing governance models | Risks, oversight, inequity | CASP | High |

| Agarwal & Gao, 2024 [58] | Empirical analysis | Multinational | Global inequity in AI development | None | Innovation disparities, economic inequality | STROBE | Moderate |

| Thomasian et al., 2021 [59] | Review | LMICs | AI deployment barriers in low-resource regions | HIC AI development models | Infrastructure gaps, scalability | CASP | Moderate |

| Olawade et al., 2025 [60] | Narrative scoping review | LMICs | Use of telemedicine & AI tools | High-income country adoption | Health disparities, system capacity | JBI Checklist | Moderate |

References

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Past, present and future. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, K.H.; Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, J.; Bali, O. Artificial intelligence in ophthalmology and healthcare: An updated review of the techniques in use. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waldman, C.E.; Hermel, M.; Hermel, J.A.; Allinson, F.; Pintea, M.N.; Bransky, N.; Udoh, E.; Nicholson, L.; Robinson, A.; Gonzalez, J.; et al. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A primer for medical education in radiomics. Pers. Med. 2022, 19, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickam, P.; Mariappan, S.A.; Murugesan, S.M.; Hansda, S.; Kaushik, A.; Shinde, R.; Thipperudraswamy, S.P. Artificial Intelligence [AI] and Internet of Medical Things [IoMT] Assisted Biomedical Systems for Intelligent Healthcare. Biosensors 2022, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reddy, S.; Fox, J.; Purohit, M.P. Artificial intelligence-enabled healthcare delivery. J. R. Soc. Med. 2019, 112, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, N.S.; Kumar, P. Perspective of artificial intelligence in healthcare data management: A journey towards precision medicine. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 162, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.; Pandit, A.; Shukla, S. Transforming healthcare with big data analytics and artificial intelligence: A systematic mapping study. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 100, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Brenner, S.E.; Chen, J.H.; Crawford, D.C.; Kidziński, Ł.; Ouyang, D.; Daneshjou, R. Session Introduction: Precision Medicine: Using Artificial Intelligence to Improve Diagnostics and Healthcare. In Proceedings of the Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 2023, Kohala Coast, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2023; pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Wei, M.-Y.; Li, G.-Y. Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ball, H.C. Improving Healthcare Cost, Quality, and Access Through Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 66, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, E.G.; Lemak, C.H.; Rojas, J.C.; Guptill, J.; Classen, D. Adoption of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Survey of health system priorities, successes, and challenges. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kassam, A.; Kassam, N. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A Canadian context. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Kushniruk, A.; Borycki, E. Barriers to and Facilitators of Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Hum. Factors 2024, 11, e48633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asan, O.; Bayrak, A.E.; Choudhury, A. Artificial Intelligence and Human Trust in Healthcare: Focus on Clinicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wubineh, B.Z.; Deriba, F.G.; Woldeyohannis, M.M. Exploring the opportunities and challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare: A systematic literature review. Urol Oncol. 2024, 42, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Arab, R.A.; Al Moosa, O.A.; Sagbakken, M. Economic, ethical, and regulatory dimensions of artificial intelligence in healthcare: An integrative review. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1617138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hennrich, J.; Ritz, E.; Hofmann, P.; Urbach, N. Capturing artificial intelligence applications’ value proposition in healthcare—A qualitative research study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Househ, M. Artificial Intelligence Solutions to Detect Fraud in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 295, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbodio, M.L.; López, V.; Hoang, T.L.; Brisimi, T.; Picco, G.; Vejsbjerg, I.; Rho, V.; Mac Aonghusa, P.; Kristiansen, M.; Segrave-Daly, J. Collaborative artificial intelligence system for investigation of healthcare claims compliance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Albert, D. The future of artificial intelligence-based remote monitoring devices and how they will transform the healthcare industry. Future Cardiol. 2022, 18, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilan, Y. Improving Global Healthcare and Reducing Costs Using Second-Generation Artificial Intelligence-Based Digital Pills: A Market Disruptor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loh, H.W.; Ooi, C.P.; Seoni, S.; Barua, P.D.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, U.R. Application of explainable artificial intelligence for healthcare: A systematic review of the last decade [2011–2022]. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 226, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, J. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: The Need for More Interpretable Artificial Intelligence. Acta Med. Port. 2024, 37, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Jolly, L.; Dakua, S.P. Advancing explainable AI in healthcare: Necessity, progress, and future directions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2025, 119, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo, L.; Fenton, A.; Davis, G. Artificial intelligence [AI] applications in healthcare and considerations for nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2024, 80, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, B.D. Education and the Adoption of AI in Healthcare: “What Is Happening?”. Healthc. Pap. 2025, 22, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalthoff, D.; Prien, M.; Götz, N.A. “ai4health”—Development and Conception of a Learning Programme in Higher and Continuing Education on the Fundamentals, Applications and Perspectives of AI in Healthcare. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 294, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, B.; Dickman, E.; Watson, J.L. Artificial Intelligence: Basics, Impact, and How Nurses Can Contribute. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 27, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areshtanab, H.N.; Rahmani, F.; Vahidi, M.; Saadati, S.Z.; Pourmahmood, A. Nurses perceptions and use of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aquino, Y.S.J.; Rogers, W.A.; Braunack-Mayer, A.; Frazer, H.; Win, K.T.; Houssami, N.; Degeling, C.; Semsarian, C.; Carter, S.M. Utopia versus dystopia: Professional perspectives on the impact of healthcare artificial intelligence on clinical roles and skills. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 169, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.J.; Jayasena, R.; Khanna, S.; Arnott, L.; Lane, P.; Bain, C. Challenges for implementing generative artificial intelligence [GenAI] into clinical healthcare. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warraich, H.J.; Tazbaz, T.; Califf, R.M. FDA Perspective on the Regulation of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care and Biomedicine. JAMA 2025, 333, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, M.M.; Guha, N. Understanding Liability Risk from Using Health Care Artificial Intelligence Tools. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, I.G.; Evgeniou, T.; Gerke, S.; Minssen, T. The European artificial intelligence strategy: Implications and challenges for digital health. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e376–e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kolfschooten, H.; van Oirschot, J. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act [2024]: Implications for healthcare. Health Policy 2024, 149, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, R.; Ayub, B.; Siddiqui, M.A.R. Quality of reporting of randomised controlled trials of artificial intelligence in healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shelmerdine, S.C.; Arthurs, O.J.; Denniston, A.; Sebire, N.J. Review of study reporting guidelines for clinical studies using artificial intelligence in healthcare. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021, 28, e100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teo, Z.L.; Kwee, A.; Lim, J.C.; Lam, C.S.; Ho, D.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Su, Y.; Chesterman, S.; Chen, T.; Tan, C.C.; et al. Artificial intelligence innovation in healthcare: Relevance of reporting guidelines for clinical translation from bench to bedside. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2023, 52, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Decary, M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: An essential guide for health leaders. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2020, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, J.; Sharma, R.; Dutta, P.; Bhunia, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A mastery. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2024, 40, 1659–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinners, L.; Aggar, C.; Stephens, A.; Grace, S. Healthcare professionals’ experiences and perceptions of artificial intelligence in regional and rural health districts in Australia. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2023, 31, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinners, L.; Aggar, C.; Grace, S.; Smith, S. Exploring healthcare professionals’ understanding and experiences of artificial intelligence technology use in the delivery of healthcare: An integrative review. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.M.; Pinto, M.D. Human Near the Loop: Implications for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2024, 33, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, A.F.; Kors, J.A.; Rijnbeek, P.R. The role of explainability in creating trustworthy artificial intelligence for health care: A comprehensive survey of the terminology, design choices, and evaluation strategies. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 113, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Saeed, H.; Pringle, C.; Eleftheriou, I.; Bromiley, P.A.; Brass, A. Artificial intelligence projects in healthcare: 10 practical tips for success in a clinical environment. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021, 28, e100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brault, N.; Saxena, M. For a critical appraisal of artificial intelligence in healthcare: The problem of bias in mHealth. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, D.; Hirani, R.; Khessib, S.; Ali, N.; Etienne, M. Unveiling biases of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Navigating the promise and pitfalls. Injury 2024, 55, 111358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritharidou, M.; Chrysogonidis, G.; Ventouris, T.; Tsarapastsanis, V.; Aristeridou, D.; Karatzia, A.; Calambur, V.; Huda, A.; Hsueh, S. Ethicara for Responsible AI in Healthcare: A System for Bias Detection and AI Risk Management. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2024, 2023, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esin, H.; Karaali, C.; Teker, K.; Mergen, H.; Demir, O.; Aydogan, S.; Keskin, M.Z.; Emiroglu, M. Patients’ perspectives on the use of artificial intelligence and robots in healthcare. Bratisl. Lekárske Listy 2024, 125, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, K.; Dougherty, R.B.; Neely, S.R.; Okhai, R. Public perceptions of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Ethical concerns and opportunities for patient-centered care. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Syed, W.; Babelghaith, S.D.; Al-Arifi, M.N. Assessment of Saudi Public Perceptions and Opinions towards Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. Medicina 2024, 60, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalid, N.; Qayyum, A.; Bilal, M.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Qadir, J. Privacy-preserving artificial intelligence in healthcare: Techniques and applications. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 158, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsteen, A.; Farkash, A.; Moffie, M.; Shmelkin, R. Applying Artificial Intelligence Privacy Technology in the Healthcare Domain. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 294, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Jingwa, K.A.; Okoye, O.K.; John Okah, M.; Ladele, J.A.; Farah, A.H.; Alimi, H.A. Ethical implications of AI and robotics in healthcare: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e36671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ning, Y.; Teixayavong, S.; Shang, Y.; Savulescu, J.; Nagaraj, V.; Miao, D.; Mertens, M.; Ting, D.S.W.; Ong, J.C.L.; Liu, M.; et al. Generative artificial intelligence and ethical considerations in health care: A scoping review and ethics checklist. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e848–e856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, E.; Morrison, M.; Jakab, I. Ethical and social considerations of applying artificial intelligence in healthcare—A two-pronged scoping review. BMC Med. Ethics 2025, 26, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agarwal, R.; Gao, G. Toward an “Equitable” Assimilation of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning into Our Health Care System. North Carol. Med. J. 2024, 85, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomasian, N.M.; Eickhoff, C.; Adashi, E.Y. Advancing health equity with artificial intelligence. J. Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olawade, D.B.; Bolarinwa, O.A.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Shongwe, S. The role of artificial intelligence in enhancing healthcare for people with disabilities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 364, 117560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumah, E. Artificial intelligence in healthcare and its implications for patient centered care. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, T.; Prencipe, G.; Malizia, A.; Filogna, S.; Latrofa, F.; Sgandurra, G. Pathways to democratized healthcare: Envisioning human-centered AI-as-a-service for customized diagnosis and rehabilitation. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 151, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuhair, V.; Babar, A.; Ali, R.; Oduoye, M.O.; Noor, Z.; Chris, K.; Okon, I.I.; Rehman, L.U. Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Global Health and Enhancing Healthcare in Developing Nations. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241245847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dehnavieh, R.; Inayatullah, S.; Yousefi, F.; Nadali, M. Artificial Intelligence [AI] and the future of Iran’s Primary Health Care [PHC] system. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goirand, M.; Austin, E.; Clay-Williams, R. Implementing Ethics in Healthcare AI-Based Applications: A Scoping Review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2021, 27, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S. Generative AI in healthcare: An implementation science informed translational path on application, integration and governance. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moulaei, K.; Yadegari, A.; Baharestani, M.; Farzanbakhsh, S.; Sabet, B.; Afrash, M.R. Generative artificial intelligence in healthcare: A scoping review on benefits, challenges and applications. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 188, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.S.; Patrinely, J.R., Jr.; Osterman, T.; Wheless, L.; Johnson, D.B. On the cusp: Considering the impact of artificial intelligence language models in healthcare. Med 2023, 4, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, J.A.; Lungren, M.P.; Shah, N.H. Ensuring useful adoption of generative artificial intelligence in healthcare. J. Am. Med Inform. Assoc. 2024, 31, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhuyan, S.S.; Sateesh, V.; Mukul, N.; Galvankar, A.; Mahmood, A.; Nauman, M.; Rai, A.; Bordoloi, K.; Basu, U.; Samuel, J. Generative Artificial Intelligence Use in Healthcare: Opportunities for Clinical Excellence and Administrative Efficiency. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diaz-Flores, E.; Meyer, T.; Giorkallos, A. Evolution of Artificial Intelligence-Powered Technologies in Biomedical Research and Healthcare. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 182, 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, G.S.; Kolusu, A.S.; Prasad, K.; Samudrala, P.K.; Nemmani, K.V. Advancing health care via artificial intelligence: From concept to clinic. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 934, 175320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H. Synergizing blockchain and artificial intelligence to enhance healthcare. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos, J.; Raposo, G.; Antunez, L. Data Federation in Healthcare for Artificial Intelligence Solutions. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 295, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, D.; Makridis, C.A.; Alterovitz, G.; Ramoni, R.; Clancy, C. Developing and Implementing Predictive Models in a Learning Healthcare System: Traditional and Artificial Intelligence Approaches in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, K.; Gabarron, E. How Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare Look Like in the Future? Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2021, 281, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicek, V.; Bagci, U. Position of artificial intelligence in healthcare and future perspective. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 167, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmatizadeh, S.; Dabbagh, A.; Shabani, F. Foundations of Artificial Intelligence: Transforming Health Care Now and in the Future. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2025, 43, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Peng, G.; VoPham, T. An overview of GeoAI applications in health and healthcare. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2019, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Secinaro, S.; Calandra, D.; Secinaro, A.; Muthurangu, V.; Biancone, P. The role of artificial intelligence in healthcare: A structured literature review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gehlot, V.; King, D.; Schaffer, J.; Sloane, E.B.; Wickramasinghe, N. Healthcare Optimization and Augmented Intelligence by Coupling Simulation & Modeling: An Ideal AI/ML Partnership for a Better Clinical Informatics. AMIA Annu. Symp Proc. 2023, 2022, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tingle, J. Pressing issues in healthcare digital technologies and AI. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiera, E.; Liu, S. Evidence synthesis, digital scribes, and translational challenges for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noorbakhsh-Sabet, N.; Zand, R.; Zhang, Y.; Abedi, V. Artificial Intelligence Transforms the Future of Health Care. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aslani, A.; Pournik, O.; Abbasi, S.F.; Arvanitis, T.N. Transforming Healthcare: The Role of Artificial Intelligence. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 327, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panch, T.; Szolovits, P.; Atun, R. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and health systems. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 020303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lorkowski, J.; Grzegorowska, O.; Pokorski, M. Artificial Intelligence in the Healthcare System: An Overview. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1335, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Singh, G.; Jain, S.; Mittal, P. Beyond boundaries: Charting the frontier of healthcare with big data and ai advancements in pharmacovigilance. Health Sci. Rev. 2025, 14, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchiarelli, A. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Opportunities and Risks. Psychiatr. Danub. 2023, 35 (Suppl. 3), 90–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sunarti, S.; Rahman, F.F.; Naufal, M.; Risky, M.; Febriyanto, K.; Masnina, R. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Opportunities and risk for future. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35 (Suppl. 1), S67–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, F.Y.; Krebs, V.L.J.; Carvalho, W.B. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in pediatrics and neonatology healthcare. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2022, 68, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miloski, B. Opportunities for artificial intelligence in healthcare and in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, V.S.; Pavlovic, Z.J.; Hariton, E. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 50, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, A. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Cardiovascular Health Care. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 109, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, A.D.; Devi, M. Artificial intelligence in diabetes management: Transformative potential, challenges, and opportunities in healthcare. Hormones 2025, 24, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K.W.; Li, Q.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, G. Artificial intelligence in mental healthcare: An overview and future perspectives. Br. J. Radiol. 2023, 96, 20230213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laacke, S.; Mueller, R.; Schomerus, G.; Salloch, S. Artificial Intelligence, Social Media and Depression. A New Concept of Health-Related Digital Autonomy. Am. J. Bioeth. 2021, 21, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaranayake, L. IDJ Pioneers Efforts to Reframe Dental Health Care Through Artificial Intelligence [AI]. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rowe, J.P.; Lester, J.C. Artificial Intelligence for Personalized Preventive Adolescent Healthcare. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, S52–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeilzadeh, P. Challenges and strategies for wide-scale artificial intelligence [AI] deployment in healthcare practices: A perspective for healthcare organizations. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 151, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinger, L.; Gazendam, A.; Ekhtiari, S.; Bhandari, M. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in research and healthcare. Injury 2023, 54 (Suppl. 3), S69–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, I. Artificial intelligence: Opportunities and implications for the health workforce. Int. Health 2020, 12, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harrison, S.; Despotou, G.; Arvanitis, T.N. Hazards for the Implementation and Use of Artificial Intelligence Enabled Digital Health Interventions, a UK Perspective. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 289, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriharan, A.; Kuhlmann, E.; Correia, T.; Tahzib, F.; Czabanowska, K.; Ungureanu, M.; Kumar, B.N. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Balancing Technological Innovation With Health and Care Workforce Priorities. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2025, 40, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Byrne, M.D. Reducing Bias in Healthcare Artificial Intelligence. J Perianesth. Nurs. 2021, 36, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lhotská, L. Artificial intelligence in medicine and healthcare: Opportunity and/or threat. Cas. Lek. Cesk. 2024, 162, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kluge, E.-H.W. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Ethical considerations. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluge, E.-H. The ethics of artificial intelligence in healthcare: From hands-on care to policy-making. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2024, 37, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karbasi, Z.; Niko, M.M.; Zahmatkeshan, M. Enhancing healthcare with ethical considerations in artificial intelligence. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molbæk-Steensig, H.; Scheinin, M. Human Rights and Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare-Related Settings: A Grammar of Human Rights Approach. Eur. J. Health Law 2025, 32, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, A.; Siddiqui, T.; Taseen, S.; Mughal, S. Revolutionising Impacts of Artificial Intelligence on Health Care System and Its Related Medical In-Transparencies. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 1546–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Allan, S.; Coghlan, S.; Cooper, P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hassan, M.; Borycki, E.M.; Kushniruk, A.W. Artificial intelligence governance framework for healthcare. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2025, 38, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romagnoli, A.; Ferrara, F.; Langella, R.; Zovi, A. Healthcare Systems and Artificial Intelligence: Focus on Challenges and the International Regulatory Framework. Pharm. Res. 2024, 41, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardic, N.; Dinc, R. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Current Regulatory Landscape and Future Directions. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2025, 86, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, A.; Pizzolla, E.; Palmieri, S.; Briganti, G. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare and Regulation Challenges: A Mini Guide for [Mental] Health Professionals. Psychiatr. Danub. 2024, 36 (Suppl. 2), 348–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Howell, M.D.; Corrado, G.S.; DeSalvo, K.B. Three Epochs of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. JAMA 2024, 331, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paton, C.; Kobayashi, S. An Open Science Approach to Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2019, 28, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cecchi, R.; Haja, T.M.; Calabrò, F.; Fasterholdt, I.; Rasmussen, B.S.B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Why not apply the medico-legal method starting with the Collingridge dilemma? Int. J. Leg. Med. 2024, 138, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, D.; Romao, M.; Morré, S.A.; Kalra, D. Artificial Intelligence: Power for Civilisation—And for Better Healthcare. Public Health Genom. 2019, 22, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.C. How might the rapid development of artificial intelligence affect the delivery of UK Defence healthcare? BMJ Mil. Health 2025, 171, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Goh, W.W.; Tan, C.H.; Tan, C.; Prahl, A.; Lwin, M.O.; Sung, J. Regulating, implementing and evaluating AI in Singapore healthcare: AI governance roundtable’s view. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2025, 54, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare and Medicine: Promises, Ethical Challenges and Governance. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2019, 34, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, B. Towards Accountable, Legitimate and Trustworthy AI in Healthcare: Enhancing AI Ethics with Effective Data Stewardship. New Bioeth. 2024, 30, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueper, J.K.; Pandit, J. Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare in Canada: Contrasting Advances and Challenges. Healthc. Pap. 2025, 22, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuei, S.H. How Are Canadians Regulating Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare? A Brief Analysis of the Current Legal Directions, Challenges and Deficiencies. Healthc. Pap. 2025, 22, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueper, J.K.; Pandit, J.A. Artificial Intelligence in the Canadian Healthcare System: Scaling From Novelty to Utility. Healthc. Pap. 2025, 22, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy, A.; Gowda, N.R.; Vikas, H.; Prabhu, M.; Sharma, D.; Gowda, P.R.; Mohan, D.; Kumar, A. It’s the data, stupid: Inflection point for Artificial Intelligence in Indian healthcare. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 128, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangi, R.R.; Sharma, A.; Vageriya, V. Transforming Healthcare in Low-Resource Settings With Artificial Intelligence: Recent Developments and Outcomes. Public Health Nurs. 2025, 42, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.Q. Adopting Artificial Intelligence in Public Healthcare: The Effect of Social Power and Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strika, Z.; Petkovic, K.; Likic, R.; Batenburg, R. Bridging healthcare gaps: A scoping review on the role of artificial intelligence, deep learning, and large language models in alleviating problems in medical deserts. Postgrad. Med. J. 2024, 101, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrington, D.J.; Holm, S. Healthcare ethics and artificial intelligence: A UK doctor survey. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e089090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, S. A Clinician’s Guide to Artificial Intelligence [AI]: Why and How Primary Care Should Lead the Health Care AI Revolution. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2022, 35, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laï, M.-C.; Brian, M.; Mamzer, M.-F. Perceptions of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Findings from a qualitative survey study among actors in France. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crowe, B.; Shah, S.; Teng, D.; Ma, S.P.; DeCamp, M.; Rosenberg, E.I.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Collins, B.X.; Huber, K.; Karches, K.; et al. Recommendations for Clinicians, Technologists, and Healthcare Organizations on the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: A Position Statement from the Society of General Internal Medicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, 40, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ognjanovic, I. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2020, 274, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheny, M.E.; Goldsack, J.C.; Saria, S.; Shah, N.H.; Gerhart, J.; Cohen, I.G.; Price, W.N.; Patel, B.; Payne, P.R.O.; Embí, P.J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence In Health And Health Care: Priorities For Action. Health Aff. 2025, 44, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheny, M.E.; Whicher, D.; Thadaney Israni, S. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: A Report From the National Academy of Medicine. JAMA 2020, 323, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polevikov, S. Advancing AI in healthcare: A comprehensive review of best practices. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 117519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizna, S.; Arora, S.; Saluja, P.; Das, G.; Alanesi, W.A. An analytic research and review of the literature on practice of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aung, Y.Y.M.; Wong, D.C.S.; Ting, D.S.W. The promise of artificial intelligence: A review of the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 139, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whicher, D.; Rapp, T. The Value of Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare Decision Making—Lessons Learned. Value Health 2022, 25, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, A.; Ngai, J.I. Robot: Healthcare Decisions Made With Artificial Intelligence. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 1852–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Z.; Mohamed, K.; Zeeshan, S.; Dong, X. Artificial intelligence with multi-functional machine learning platform development for better healthcare and precision medicine. Database 2020, 2020, baaa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marin, H.F. Artificial intelligence in healthcare and IJMI scope. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 177, 105150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Aslam, A.; Tahir, Z.; Ashraf, B.; Tanweer, A. Advancements of AI in healthcare: A comprehensive review of ChatGPT’s applications and challenges. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2025, 75, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanfill, M.H.; Marc, D.T. Health Information Management: Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare Data and Information Management. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2019, 28, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koski, E.; Murphy, J. AI in Healthcare. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2021, 284, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Väänänen, A.; Haataja, K.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Toivanen, P. Proposal of a novel Artificial Intelligence Distribution Service platform for healthcare. F1000Research 2021, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bali, J.; Garg, R.; Bali, R.T. Artificial intelligence [AI] in healthcare and biomedical research: Why a strong computational/AI bioethics framework is required? Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siala, H.; Wang, Y. SHIFTing artificial intelligence to be responsible in healthcare: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 296, 114782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudgal, S.K.; Agarwal, R.; Chaturvedi, J.; Gaur, R.; Ranjan, N. Real-world application, challenges and implication of artificial intelligence in healthcare: An essay. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A.; Athanasiou, T. A novel modification of the Turing test for artificial intelligence and robotics in healthcare. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2015, 11, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Is it beneficial? J. Vasc. Nurs. 2019, 37, 159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, G.; Hu, J. Section Editors for the IMIA Yearbook Section on Artificial Intelligence in Health Artificial Intelligence in Health in 2018: New Opportunities, Challenges, and Practical Implications. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2019, 28, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahamtalla, B.M.; Medani, I.E.; Abdelhag, M.E.; Eltigani, S.A.; Rajan, S.K.; Falgy, E.; Hassan, N.M.; Fadailu, M.E.; Khudhayr, H.A.; Abdalla, A. The AI-Powered Healthcare Ecosystem: Bridging the Chasm Between Technical Validation and Systemic Integration—A Systematic Review. Future Internet 2025, 17, 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120550

Rahamtalla BM, Medani IE, Abdelhag ME, Eltigani SA, Rajan SK, Falgy E, Hassan NM, Fadailu ME, Khudhayr HA, Abdalla A. The AI-Powered Healthcare Ecosystem: Bridging the Chasm Between Technical Validation and Systemic Integration—A Systematic Review. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):550. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120550

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahamtalla, Babiker Mohamed, Isameldin Elamin Medani, Mohammed Eltahir Abdelhag, Sara Ahmed Eltigani, Sudha K. Rajan, Essam Falgy, Nazik Mubarak Hassan, Marwa Elfatih Fadailu, Hayat Ahmad Khudhayr, and Abuzar Abdalla. 2025. "The AI-Powered Healthcare Ecosystem: Bridging the Chasm Between Technical Validation and Systemic Integration—A Systematic Review" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120550

APA StyleRahamtalla, B. M., Medani, I. E., Abdelhag, M. E., Eltigani, S. A., Rajan, S. K., Falgy, E., Hassan, N. M., Fadailu, M. E., Khudhayr, H. A., & Abdalla, A. (2025). The AI-Powered Healthcare Ecosystem: Bridging the Chasm Between Technical Validation and Systemic Integration—A Systematic Review. Future Internet, 17(12), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120550