Abstract

Polymeric micelles have become a versatile and clinically significant class of nanocarriers for cancer therapy. They effectively solubilize poorly water-soluble anticancer drugs, extend their circulation in the bloodstream, and promote accumulation in tumors. Early studies focused on conventional PEG-based polymeric micelles that utilize passive targeting based on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, with several of these advancing to clinical trials. Active targeting strategies using modified polymer micelles with various targeting ligands have been introduced to enhance cellular uptake and improve tumor specificity. Recently, the field has shifted toward smart polymer micelles that can respond to both internal (endogenous) and external (exogenous) stimuli. These stimuli-responsive systems enable controlled drug release, enhance delivery inside cells, and improve therapeutic effectiveness, all while reducing systemic toxicity. This review summarizes recent advancements in polymer design, drug-loading techniques, preparation methods, and targeting strategies for polymeric micelles, highlighting both preclinical progress and systems that have reached clinical stages. The transition from conventional to smart polymer micelles is a significant advancement toward achieving more precise, effective, and personalized cancer nanomedicine.

1. Introduction

Cancer continues to be one of the leading causes of illness and death worldwide, despite significant progress in diagnosis and treatment. According to the latest global estimates from the American Association for Cancer Research and the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), approximately 20 million new cancer cases were diagnosed worldwide in 2022 [1,2]. This number is expected to remain similar or increase slightly by 2025 as global populations continue to age and grow. Each year, over 10 million people die from cancer, making it a major cause of death globally [2]. Current cancer treatments include surgical intervention, radiation, and chemotherapeutic drugs. Among them, conventional chemotherapy continues to play a central role in cancer treatment; however, its clinical effectiveness is often limited by the poor aqueous solubility of many anticancer drugs, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, nonspecific biodistribution, and severe systemic toxicities [3]. In particular, widely used classes of chemotherapeutic agents, such as taxanes, antracyclines, platinum-based drugs, and camptothecin derivatives, face formulation challenges and dose-limiting side effects, highlighting the urgent need for improved drug delivery strategies [4].

Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems have emerged as a powerful approach to overcome the major limitations of conventional chemotherapy, such as poor solubility, rapid systemic clearance, nonspecific biodistribution, and dose-limiting toxicity. Various nanoscale carriers, including polymeric micelles [5,6], liposomes [7,8], polymeric nanoparticles [9], dendrimers [10], and inorganic nanocarriers [11], have been extensively investigated to improve drug solubility, enhance tumor accumulation via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and enable controlled or stimuli-responsive drug release. Among these systems, polymeric micelles formed from amphiphilic block copolymers are particularly attractive due to their small size, core–shell architecture, high drug-loading capacity for hydrophobic drugs, and ease of surface functionalization for active targeting. The hydrophobic core serves as a reservoir for poorly water-soluble anticancer agents, while the hydrophilic corona, often composed of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), provides steric stabilization, prolongs systemic circulation, and reduces recognition by the reticuloendothelial system [12]. Early generations of polymeric micelles primarily relied on passive targeting mechanisms, exploiting the EPR effect to preferentially accumulate in tumor tissues [13]. A number of micellar formulations based on passive targeting demonstrated improved pharmacokinetics, enhanced tumor accumulation, and reduced formulation-related toxicities compared to conventional solvent-based drugs, validating the clinical potential of polymeric micelles [14]. Despite these advancements, conventional polymeric micelles still encounter significant challenges, including premature drug leakage, limited tumor penetration, heterogeneous EPR effects among patients, and insufficient intracellular drug release [15]. One effective way to address these limitations is to design nanocarriers that can actively bind to specific cells after they have exited the bloodstream. This binding can be accomplished by attaching targeting agents, such as ligand molecules that specifically bind to receptors on the cell surface through ligand–receptor interactions and internalize into the cells, allowing the drug to be released inside the cell [11]. “Smart” polymer micellar systems with stimuli-responsive properties that allow for controlled drug release are the next-generation drug delivery systems. The drug release can be triggered by endogenous factors, which are intrinsic stimuli from the body’s unique pathways, or the characteristics of malignancies, as well as exogenous factors, which are external stimuli that enhance release [16]. Recent advances have further expanded the scope of polymeric micelles through multifunctional designs, including dual-ligand targeting, co-delivery of multiple drugs, and a combination of passive and active targeting strategies [17,18]. These developments represent a paradigm shift from simple drug solubilization platforms to intelligent nanocarriers capable of overcoming biological barriers and addressing tumor heterogeneity.

This review highlights recent progress in using polymeric micelles for cancer therapy, focusing on the transition from conventional PEG-based systems by passive and active targeting of cancer cells to novel, smart micelles that respond to stimuli and have specific targets depending on the applied stimuli. This review discusses key design principles of polymeric micelles, drug-loading strategies, and the main stimulus-responsive mechanisms, and summarizes representative preclinical and clinical studies.

2. Principles of Self-Assembly

The ability of a given molecule to self-organize and form aggregates with complex architecture depends on its amphiphilicity, which is determined by the presence of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments in its structure. The hydrophilic part can be anionically, cationically, or zwitterionically charged, or it may lack ionic functional groups altogether. In this way, the corresponding ionogenic or non-ionogenic amphiphilic molecules are formed [19]. Typical amphiphiles include various surfactants, as well as natural phospholipids and peptides [20,21]. In an aqueous environment, amphiphilic molecules can form particles that range in size from a nanometer to several micrometers, influenced by weak non-covalent interactions [22]. The thermodynamic driving force behind supramolecular organization primarily involves desolvation processes, conformational flexibility, and the intra- and intermolecular interactions between the hydrophobic segments of these molecules. Additionally, interaction forces from polar groups and hydrogen bonding can also affect the size and morphology of the resulting amphiphilic aggregates. Factors such as temperature, pH, and the ionic strength of the solvent have been shown to influence the characteristics of this supramolecular assembly [23]. Overall, the self-organization process is dynamic and can be controlled by modifying any of these parameters [24].

2.1. Self-Assembly of Amphiphilic Block Copolymers

Amphiphilic block copolymers that form micelles in aqueous systems have gained increasing attention in recent decades as drug delivery systems. They are designed to maximize the therapeutic effectiveness of drugs while minimizing their negative side effects. These copolymers consist of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks that are covalently bonded together, functioning similarly to surfactants. Several methods are available for synthesizing amphiphilic block copolymers, including free radical polymerization (FRP) [25], ring-opening polymerization (ROP) [26,27,28], “living” anionic polymerization (LAP) [29], and controlled radical polymerization (CRP) [30]. Among these, controlled radical polymerizations are the most commonly used techniques, and include atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization (NMP), and reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerization (RAFT) [30]. These approaches enable the synthesis of block copolymers with well-defined compositions, molecular weights, and complex architectures, which are able to self-assemble to a wide variety of well-defined structures in different morphologies [31,32,33,34].

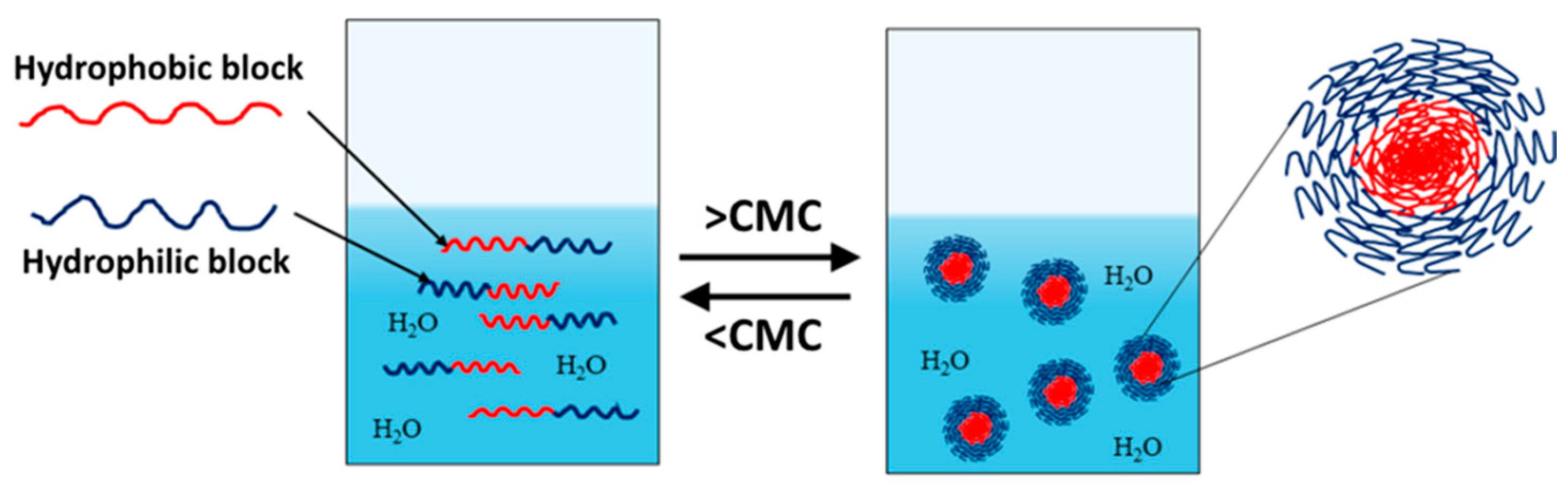

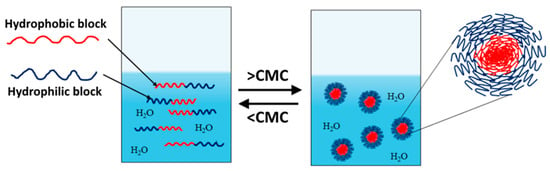

Amphiphilic block copolymers dissolved in water as a selective solvent are the most commonly studied systems. Self-assembly is driven by the polymer chains’ need to minimize energetically unfavorable hydrophobic interactions. Therefore, micellization occurs as a result of two forces: the attractive forces between the hydrophobic blocks, which lead to the aggregation of the hydrophobic parts and the formation of the micelle core, and the repulsive forces between the hydrophilic segments, which form the micelle shell. The repulsive forces prevent unlimited micelle growth, while the interactions between the hydrophilic chains and the solvent further stabilize the micelles [32,33,34]. The micellization process of amphiphilic copolymers begins with the formation of a true solution, in which macromolecules exist in an unassociated state (unimers). Upon increasing the concentration and reaching the so-called critical micelle concentration (CMC), polymer micelles are formed in the system (Figure 1). At constant temperature, the resulting polymer particles exist in thermodynamic equilibrium with the unimers. This process is analogous to that of low-molecular-weight surfactants, with the difference being that amphiphilic block copolymers have much lower CMC values, making them stable and robust nanoscale systems [35].

Figure 1.

Unimer–micelle equilibrium of linear block copolymers in an aqueous environment.

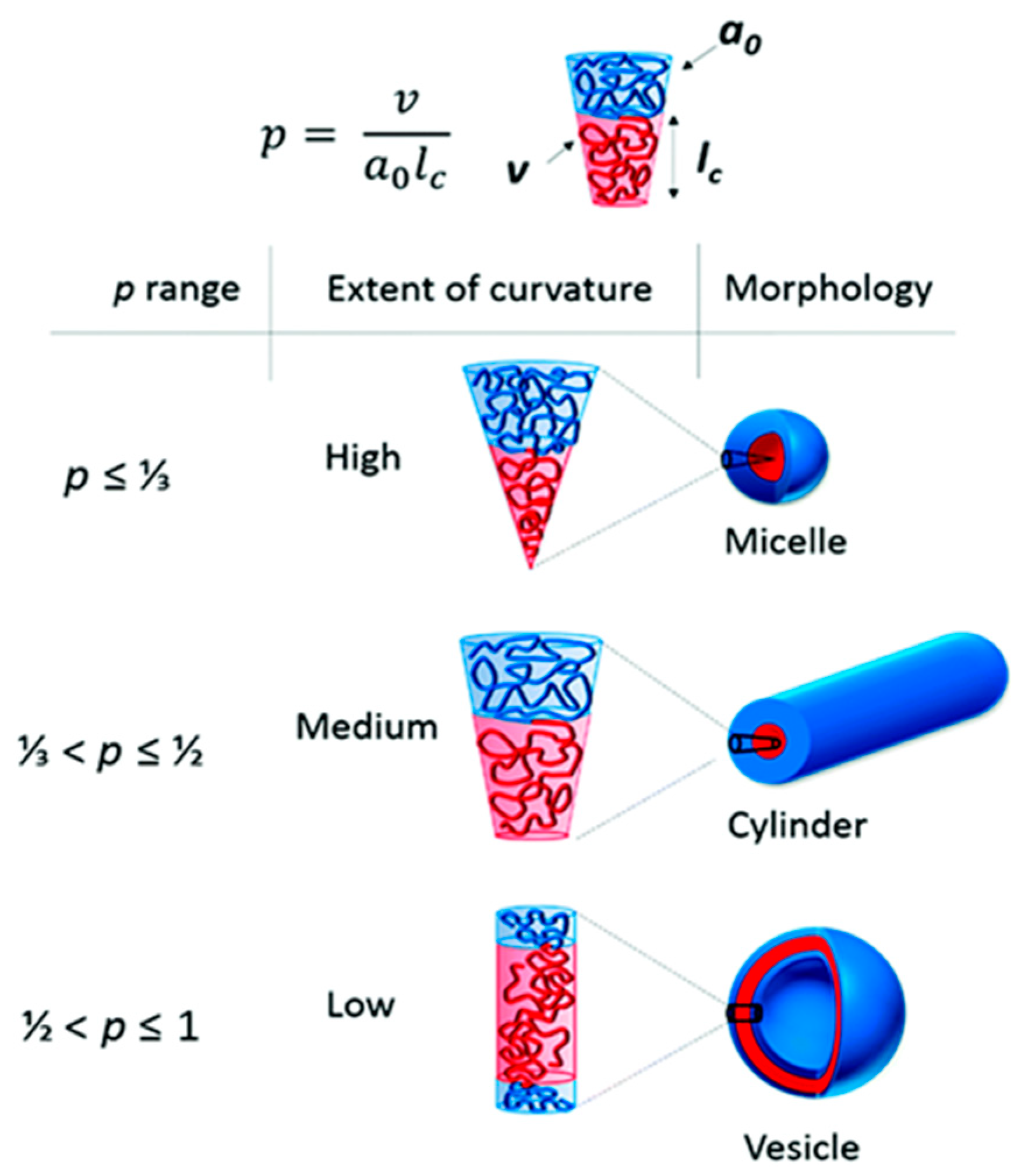

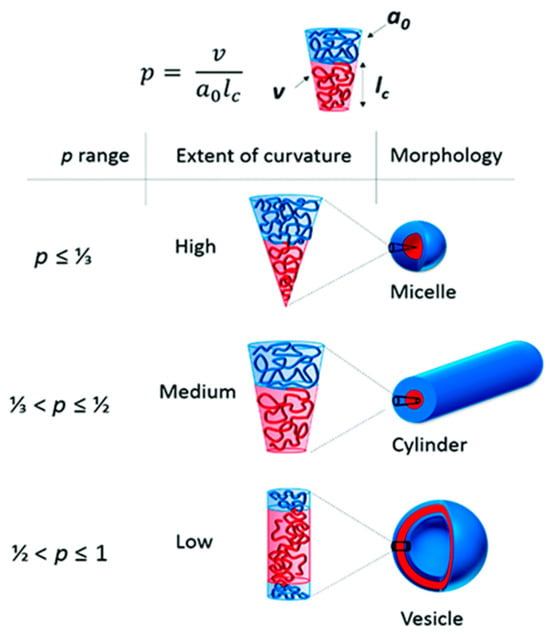

Amphiphilic block copolymers, including diblock copolymers (AB type), triblock copolymers (ABA or ABC type), and multiblock copolymers, as well as double-hydrophilic copolymers, can self-assemble in an aqueous environment. This self-assembly leads to the formation of various nanostructures, such as spherical, “flower-like,” “worm-like,” and vesicular shapes. Several factors influence the self-assembling behavior of these polymers, including temperature, pH, salt concentration, polymer concentration, the type of solvent used, and the structure and length of the polymer blocks [31]. The formation of polymer micelles with different morphologies can be predicted based on the so-called packing parameter p = ν/(a0.lc). This parameter is a key characteristic of amphiphilic polymers and is determined by their composition, where v is the volume of the hydrophobic chain, a0 is the optimal area of the head group, and lc is the length of the hydrophobic tail (Figure 2). As a rule, spherical micelles are favored when p ≤ 1/3, cylindrical micelles are favored when 1/3 ≤ p ≤ 1/2, and enclosed membrane structures (vesicles, also known as polymersomes) are favored when 1/2 ≤ p ≤ 1 [36].

Figure 2.

The different morphologies obtained depending on the packing parameters, p [36] (this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License).

2.2. Methods for the Preparation of Polymer Micelles for Drug Delivery

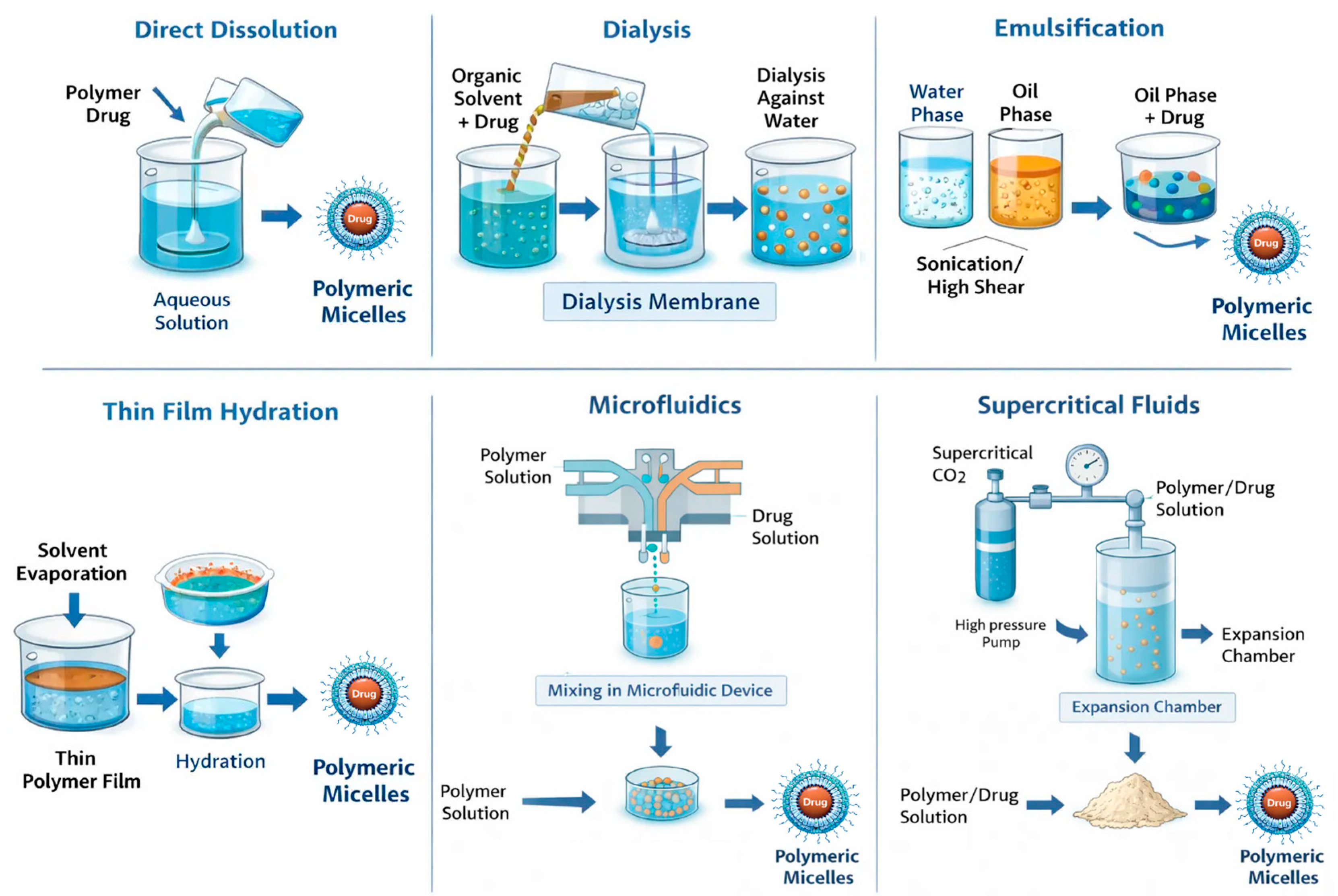

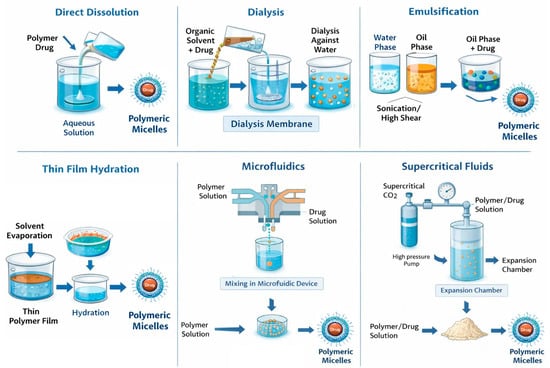

The method used to prepare polymer micelles is based on the physicochemical properties of the selected block copolymers. Importantly, this method significantly impacts the physicochemical parameters and drug encapsulation efficiency (Figure 3). Additionally, factors such as the order of addition, the ratio of aqueous to organic phases, and the concentration of copolymers affect the size, polydispersity index, and stability of the resulting micelles [37,38,39]. The preparation of polymer micelles for drug delivery is primarily carried out using two main methods [32,38]. The first method is a direct dissolution that involves a step of dissolving the block copolymer and drug in a suitable solvent. The micelle formation process occurs after thermal and/or ultrasonic treatment. This approach is mainly applicable to copolymers with low molecular weight and relatively short insoluble blocks. Depending on the type of block copolymer, equilibrium may not always be reached in the system, especially when the block forming the core has a high glass transition temperature. In such cases, so-called “frozen” micelles are formed, meaning that no exchange occurs between the micelles and the unimers [32]. The second method for preparing polymer micelles is a solvent exchange and involves processes that alter the solubility of the amphiphilic block copolymer. To achieve this, the block copolymer and the drug are first dissolved in a “good” solvent for both blocks (forming a real, true solution), and then the solvent composition is altered by gradually adding a second, “poor” solvent. The added second solvent is suitable for only one of the blocks. Gradual replacement of the common solvent with a selective one can also be achieved through evaporation of the initial solvent or by dialysis. In this way, micellar systems in aqueous environments are most commonly obtained, as it prevents the formation of large aggregates and allows the self-assembly of asymmetric block copolymers with longer hydrophobic blocks. However, this method does not always prevent the formation of “frozen” micelles, due to the glass transition of the core at a certain temperature and/or in the presence of a given solvent [32]. Other conventional methods used for the preparation of drug-loaded micelles include the solution-casting method, emulsification, and the solvent evaporation method, as well as freeze-drying (lyophilization). In the solution-casting method, also known as the thin-film hydration method [40], the polymer and drug are dissolved in a volatile organic solvent, which is then evaporated, yielding the formation of a thin polymeric film, where polymer–drug interactions are favored. The subsequent hydration of the film with an aqueous solution led to the formation of micelles. The emulsification and solvent evaporation method [41] consists of physical entrapment of a hydrophobic drug using an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion process, which involves dissolving the copolymer and drug in a non-water-miscible organic solvent (dichloromethane, ethyl acetate) followed by emulsification into an aqueous phase through sonication or high-shear homogenization. Solvent evaporation under reduced pressure then induces micelle formation through polymer precipitation. Lyophilization is often used as a post-processing step for stabilizing micelles and, in certain cases, as a direct preparation method using aqueous co-solvent systems (for example, tert-butanol/water). This technique enables prolonged storage of micelles and helps prevent drug degradation during storage. When rehydrated, micelles can reform if their structure is maintained during the drying process [38,42]. In recent years, advanced techniques for preparing polymer micelles for drug delivery have been developed. For example, microfluidic mixing enables the highly controlled assembly of nanocarriers by manipulating laminar flow and solvent mixing kinetics within microscale channels [43]. Additionally, supercritical fluid (SCF) processing has emerged as a promising approach. SCF utilizes the unique physicochemical properties of supercritical fluids, particularly carbon dioxide (scCO2) and trifluoromethane. These fluids exhibit liquid-like solvation and gas-like diffusivity above their critical temperature and pressure. These advancements contribute to the development of micellar systems that are more suitable for clinical application and pharmaceutical manufacturing [43].

Figure 3.

Polymer micelle preparation strategies.

2.3. Methods for Characterizing Polymer Micelles

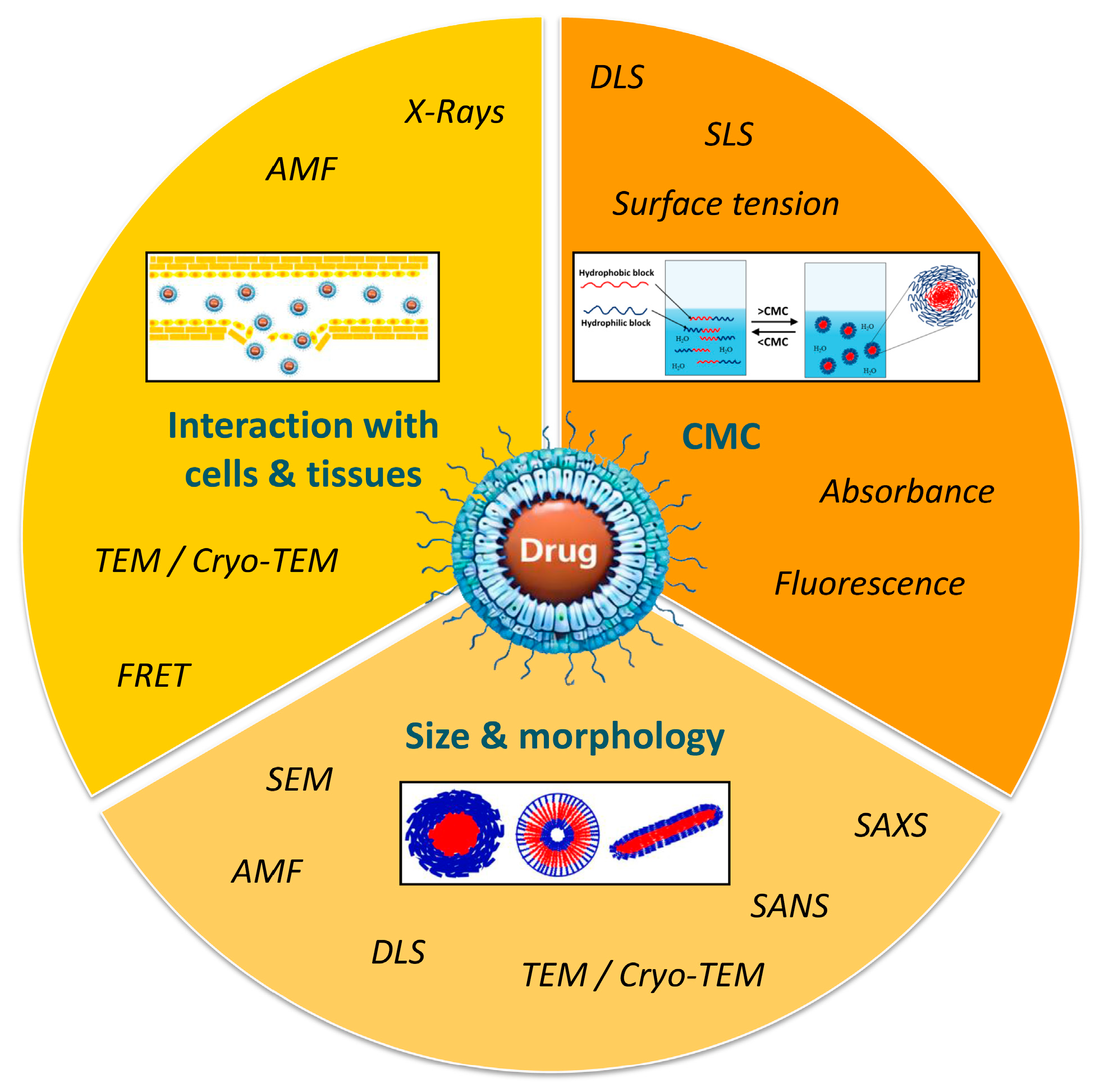

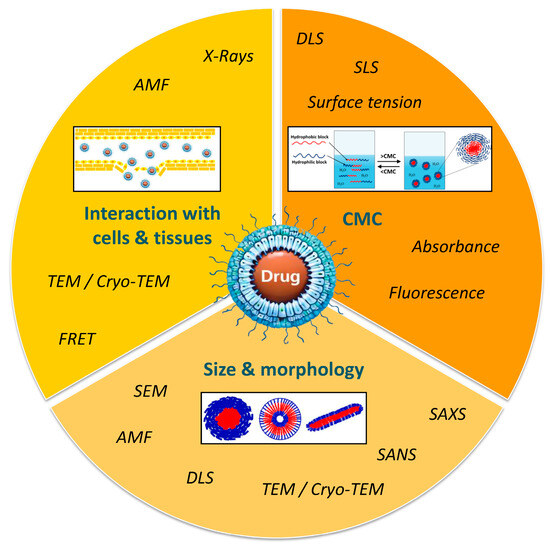

Micelle characterization is of critical importance and often requires the combination of different approaches and techniques in order to define and predict their behavior in a biological environment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methods for characterization of polymer micelles.

2.3.1. Critical Micelle Concentration Determination (CMC)

CMC determination is an important aspect of polymer micelle characterization and represents the hydrophobic and hydrophilic balance in block copolymers. A low CMC indicates enhanced micelle stability, making them ideal for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs. Various methods are used to measure CMC, including light scattering, surface tension, and electrical conductivity based on macroscopic parameters, as well as photometric and fluorometric techniques that utilize suitable optical probes [44]. The determination of CMC by surface tension can be performed by the Wilhelmy plate method [45]. When the concentration of amphiphiles increases, the surface tension decreases until the CMC comes to a constant value. Surface tension is almost constant at a concentration of the polymer above the CMC value. However, this technique requires more time and a large number of samples [46]. Some of the most widely used methods are those based on light scattering. In the dynamic or quasi-elastic light scattering (DLS) method, the scattered light is influenced by the size and molecular mass of particles in micellar solutions. The intensity of light scattering remains relatively constant below the CMC, but increases significantly when the concentration reaches the CMC. This method also enables the determination of the hydrodynamic radius (RH) of polymer micelles based on their diffusion coefficient [47]. The fluorescence or absorbance technique is one of the most commonly used methods for determining the CMC by measuring the signal exhibited by dyes, such as pyrene or 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene, within micelles formed by amphiphilic polymers. At certain polymer concentrations, a shift in excitation wavelength occurs due to the entrapment of dyes within the hydrophobic cores of polymer micelles [48,49].

2.3.2. Morphological and Structural Characterization

The morphology and size of polymer micelles can be determined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM). The primary difference between the two methods lies in their sample preparation for imaging. TEM requires complete dehydration of samples to ensure a high vacuum within the microscope column. In contrast, cryo-TEM involves rapidly freezing the samples at temperatures of at least −170 °C using liquid nitrogen, liquid propane, or liquid helium. This technique allows for the observation of specimens in their native state, preserving their solution structure and reducing artifacts that can occur during the removal of water [50,51,52,53]. Although cryo-TEM is recognized as a more suitable tool for imaging micelles compared to standard TEM, it is also time-consuming and expensive. As a whole, most TEM imaging of micelles relies on traditional TEM, as the differences in observations between the two methods are often not significant [54,55]. Another advanced technique for investigating the morphology of micelles is atomic force microscopy (AFM). This technique involves depositing the sample as a thin layer on a support and scanning it with a very sharp probe tip mounted on a cantilever. The tip deflects in response to the sample’s topography [56]. The tapping mode of AFM is especially favored for micelles, as it minimizes distortion of the micellar structure during analysis [57]. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) methods are two powerful tools used for the structural analysis of micelles. They allow determination of the micelle core size and hydrodynamic shell of polymer micelles in solution, and SANS also provides information for their cross-section [39,58]. To examine the interaction between micelles and biological environments, which is crucial for understanding their therapeutic efficacy, fluorescence-based techniques and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) are commonly used. These methods allow for the investigation of how both physiological and pathological conditions affect micelle integrity, target site accumulation, biodistribution, and drug release kinetics [59].

3. Types of Polymer Micelles

Polymer micelles used in drug delivery technology can be categorized based on their responsiveness to environmental conditions. There are two main types: conventional or “non-responsive” micelles, which provide stable and long-term drug delivery mainly through passive diffusion, and “smart” or stimuli-responsive micelles, which enable targeted and controlled drug release in response to specific environmental triggers. These triggers can include physical, chemical, or biological stimuli.

3.1. Conventional (Non-Responsive) PEG-Based Polymer Micelles for Drug Delivery

These micelles are formed from amphiphilic block copolymers, typically diblock copolymers that do not have specific sensitivity to external stimuli. The most used hydrophilic block for the preparation of amphiphilic diblock copolymers for drug delivery is polyethylene glycol (PEG). PEG is favored due to its biocompatibility, excellent anti-fouling properties, and “stealth” functionality that helps minimize detection by the immune system, reducing immunogenicity [60]. The most commonly used polymers, as the hydrophobic blocks of the micelles, are typically polylactide (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly (amino acids), or lipids. These hydrophobic polymers form the inner core of the micelle and can serve as a depot for small drugs with poor water solubility [61]. The PEG-b-PLA, PEG-b-PCL, and PEG-b-PLGA block copolymers, which demonstrated excellent bio-degradability and biocompatibility, can be conveniently synthesized through the ring-opening polymerization of lactide, glycolide, or ε-caprolactone monomers, utilizing PEG as an initiator along with an appropriate catalyst [60,61]. Thus, the hydrophilic PEG shell of the micelles enhances micelle circulation time and reduces immune recognition, while the hydrophobic core effectively encapsulates hydrophobic drugs.

3.1.1. Passive Targeting of Conventional Drug-Loaded Polymer Micelles

The passive targeting of drug-loaded micelles is a remarkable advancement in cancer therapy, driven by specific characteristics of tumor blood vessels, like their inherent leaky nature and poor lymphatic drainage. Among the various methods explored, the encapsulation of drugs within polymer micelles stands out as one of the most researched strategies for effective passive drug targeting. This approach exploits the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, allowing these nanosized micelles, which are less than 100 nm in diameter, to accumulate effectively in solid tumors. The disorganized structure of tumor blood vessels facilitates this accumulation, while the long circulation half-life of micelles ensures sustained presence at the site of action [62]. Extensive research has demonstrated that PEG-containing amphiphilic block copolymers significantly enhance the stability of these nanoparticles in systemic circulation and promote their selective accumulation in tumor tissues, all without the requirement of surface ligands or targeting moieties. Moreover, the ability of PEG to avoid recognition by the cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES) allows for improved drug availability at the target site. Consequently, this mechanism not only maximizes the therapeutic potential of anticancer drugs but also enhances the probability of effectively reaching and treating the targeted tumors [63]. Various classes of anticancer chemotherapeutic drugs have been investigated as passive targeting polymer drug delivery systems, including taxanes, anthracyclines, platinum drugs, and natural compounds.

- Taxane-Class Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Taxanes are among the most widely used drugs in chemotherapy, for the treatment of various types of cancer, including breast, lung, esophageal, prostate, bladder, head, and neck cancers [64]. They inhibit mitosis, disrupt microtubule function, and obstruct depolymerization, which stops the cell division process [64]. Paclitaxel (Taxol®) and Docetaxel (Taxotere®) are among the most effective chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of a wide range of solid tumors. However, their clinical application is limited by extremely poor aqueous solubility, the requirement for toxic solubilizing agents (e.g., Cremophor EL or polysorbate 80), dose-limiting hypersensitivity reactions, and severe systemic toxicities such as neurotoxicity [65]. To address these challenges, polymeric micellar formulations have emerged as an effective strategy by solubilizing taxanes within a hydrophobic core while forming a hydrophilic corona that prolongs systemic circulation and promotes tumor accumulation through the (EPR) effect. Several taxane-loaded micellar systems have advanced to clinical evaluation. The most prominent example is Genexol-PM® (developed by Samyang Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea), which represents a lyophilized micellar formulation based on biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(D, L-lactide) (PEG-b-PDLL) block copolymers and paclitaxel (PTX). This nanosized formulation (with a diameter of 20–50 nm) shows great promise in terms of water solubility and in vivo stability. The recommended phase II dosage for Genexol-PM® was determined to be 300 mg/m2, as compared to 170 mg/m2 for Taxol®, thus achieving a higher paclitaxel dose without additional toxicity [66,67,68]. Docetaxel (DTX) has also been successfully encapsulated in methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(D,L-lactide) polymer micelles, known as Nanoxel-PM™, which range in size from 20 to 50 nm. A preclinical study showed that Nanoxel-PM™ had fewer side effects, including hypersensitivity reactions and fluid retention, while demonstrating pharmacokinetic profiles and antitumor activity comparable to those of Taxotere® [69]. Amphiphilic block copolymers composed of PEG and modified poly(aspartate), in which approximately half of the carboxyl groups were esterified with 4-phenyl-1-butanol to increase their hydrophobicity, were developed for efficient PTX encapsulation. Through self-assembly, PTX was physically entrapped within the hydrophobic micellar core via strong hydrophobic interactions, while the PEG corona imparted stealth properties. This PTX micellar formulation, known as NK105 (NanoCarrier™), is nonimmunogenic and suitable for intravenous administration without Cremophor EL or ethanol. In HT-29 human colorectal cancer xenograft models, NK105 exhibited significantly enhanced antitumor efficacy compared with free PTX, attributed to improved tumor accumulation and sustained drug release from the micelles. Moreover, NK105 demonstrated markedly reduced neurotoxicity relative to conventional paclitaxel formulations [70,71,72].

In addition, polyethylene glycol-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-b-PCL) block copolymers (FDA-approved) have been extensively explored as polymeric nanocarriers for passive drug delivery. These amphiphilic copolymers exhibit high biocompatibility, controlled biodegradability, and self-assembly into micelles in aqueous media [12]. The low glass transition temperature of PCL further facilitates micelle formation and stable encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs [73]. The hydrophobic PCL core enables high loading of poorly soluble anticancer agents such as PTX and DTX, while the PEG corona provides steric stabilization and prolonged circulation [74]. A number of studies demonstrated the successful incorporation of paclitaxel or docetaxel into PEG-b-PCL micelles and their application in cancer therapy against breast [75], ovarian [76], and prostate [77] cancers, all of them demonstrating improved solubility, sustained release, enhanced antitumor efficacy, and reduced systemic toxicity in preclinical models compared to the free drug formulations.

- Anthracycline-Class Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Anthracyclines, a family of antitumor antibiotics, are another widely used class of chemotherapeutic agents, which are the most active cytotoxic agents for the treatment of a wide variety of solid tumors and hematological malignancies [78]. Despite their proven efficacy, their use is limited due to the toxicity to normal tissues and treatment resistance. The major side effect of anthracyclines is cardiotoxicity due to cumulative doses [79]. Among them, Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) plays an important role as a powerful anthracycline chemotherapeutic agent, which is widely used in oncology due to its ability to intercalate DNA and inhibit topoisomerase II, leading to the disruption of DNA replication and induction of apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells [80,81]. Clinically, doxorubicin is employed against a broad spectrum of hematopoietic malignancies (lymphoma, leukemia) and solid tumors such as breast and ovarian cancers [82]. Despite its broad antineoplastic activity, the clinical use of doxorubicin (DOX) is often limited by poor aqueous solubility, rapid systemic clearance, and dose-dependent cardiotoxicity. To overcome these limitations, polymeric micelles based on amphiphilic PEG-containing block copolymers have been extensively investigated as passive nanocarriers for doxorubicin delivery. For example, PEG-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL) micelles with encapsulated DOX (size of 36 nm) were prepared successfully by the solvent evaporation method. Thus, prepared micelles were tested against both drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant models, including adriamycin-resistant K562 leukemia cells. After the initial burst release of the drug, a phase of significantly sustained drug release over a long period was observed. In comparison, doxorubicin solution was released completely only within 2 h. The results showed increased intracellular drug accumulation and enhanced cytotoxicity in both drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant models, including adriamycin-resistant K562 leukemia cells, compared to the doxorubicin solution [83]. This indicates their ability to reverse multidrug resistance. Similarly, PEG-PCL-PEG triblock micelles have shown prolonged circulation and effective tumor suppression against drug-sensitive (MCF-7) breast cancer cell lines [84]. In addition, core cross-linked PCL-PEG-PCL micelles loaded with DOX have been tested on colon carcinoma cell models (C26 cell line in vitro), and results demonstrated that the encapsulated DOX in the micelles enhanced the cytotoxicity of DOX on the C26 cell line. Moreover, in vitro release profiles demonstrated a significant difference between the rapid release of free DOX and the much slower and sustained release of DOX-loaded core cross-linked micelles [85].

- Platinum-Class Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Platinum-based chemotherapeutics such as cisplatin and oxaliplatin are also widely used in oncology to treat various types of solid tumors, including ovarian, testicular, bladder, lung, and colorectal cancers. The mechanism of action involves covalent binding to purine DNA bases and the formation of cross-links that prevent DNA replication and transcription, thus leading to cellular apoptosis [86]. However, their clinical utility is limited by severe side effects (e.g., nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity) and the development of resistance. Cisplatin is highly active and widely used for the treatment of a variety of cancers; however, its use in practice is limited due to cumulative dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) and a lack of improvement in efficacy despite longer treatment [87]. While highly effective, the use of cisplatin is associated with irreversible ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity [88]. To improve their therapeutic index and exploit passive targeting via the EPR effect, platinum drugs have been incorporated into PEG-based polymeric micelles that prolong circulation and facilitate tumor accumulation. Kataoka and coworkers designed a series of PEG-b-poly(amino acid)-based micelles loaded with cisplatin for passive drug targeting into tumors. The carboxylic groups in the poly(amino acid) can form a complex with cisplatin, oxaliplatin, or other organometallic compounds via coordination [89,90]. The optimization of cisplatin-loaded PEG-poly(glutamic acid) micelles results in the development of Nanoplatin™ (NC-6004), a polymeric micelle where cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) is complexed with the carboxylate groups of PEG-poly(glutamic acid), leading to enhanced stability in aqueous solutions and improved drug release characteristics. The free drug is regenerated in the presence of chloride ions. Compared with free cisplatin, NC 6004 delivers higher amounts of cisplatin to solid tumors, while also being taken up by the liver and spleen. Preclinical studies demonstrated comparable antitumor activity with reduced nephrotoxicity. Clinically, NC 6004 exhibits prolonged circulation, enhanced tumor accumulation, and disease stabilization in patients with solid tumors, including advanced colorectal cancer, while minimizing typical cisplatin-associated toxicities [91,92,93].

In addition, the active oxaliplatin analog, (1,2-diaminocyclohexane)platinum(II) (DACHPt), has been incorporated into PEG-b-PGlu block copolymer micelles, which vary in PGlu length. In vivo distribution and antitumor activity experiments conducted on CDF1 mice bearing murine colon adenocarcinoma (C-26) showed that these micelles accumulate at the tumor site at levels 20 times greater than oxaliplatin, achieving significantly higher antitumor efficacy. The strong antitumor activity of DACHPt-loaded micelles was demonstrated, exhibiting very effective results against multiple metastases generated from injected bioluminescent HeLa (HeLa-Luc) cells [94,95]. The similar DACHPt-micelles were demonstrated to have efficient penetration and accumulation in an orthotopic scirrhous gastric cancer model, leading to the inhibition of the tumor growth. Moreover, the elevated localization of systemically injected DACHPt-micelles in metastatic lymph nodes can inhibit the growth of metastatic tumors [94,95,96].

Recent studies have investigated PEG-b-PCL and related micellar systems for the delivery of cisplatin, showing enhanced antitumor efficacy both in vitro and in vivo. These systems demonstrated improved biodistribution and reduced systemic toxicity compared to free cisplatin [97]. The biodistribution, antitumor efficacy, and toxicity of cisplatin-loaded core cross-linked micelles based on poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(methacrylic acid) (PEG-b-PMA) were also evaluated using a mouse model of ovarian cancer. The cisplatin-loaded micelles showed prolonged blood circulation, increased accumulation in tumors, and reduced exposure to the kidneys. Compared to the free drug, the micelles exhibited an improved antitumor response in this mouse model [98].

- Natural compound Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Camptothecin (CPT), a natural alkaloid with significant antiproliferative activity, and its derivatives, such as SN 38 and irinotecan, are potent topoisomerase I inhibitors—an essential enzyme for DNA replication, transcription, and repair processes [99] with broad anticancer activity, including colorectal, lung, breast, and other solid tumors [100]. The clinical application of camptothecin has been limited due to its systemic toxicity, poor aqueous solubility, and the instability of the lactone ring under physiological conditions. These factors significantly reduce its efficacy. To improve pharmacokinetics and take advantage of passive targeting through the EPR effect, various PEG-based polymer micelles have been developed to encapsulate camptothecin compounds. For example, one study involved the physical entrapment of camptothecin in a block copolymer based on mPEG-p(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PEG-PBLA). The formulation’s efficacy and size were optimized by adjusting the drug-to-polymer ratio. Additionally, the stability of the formulation in vivo was affected by the length of the mPEG block and the amount of benzyl ester, resulting in an extended circulation time [101]. Such PEG poly(benzyl aspartate) micelles have successfully delivered parent CPT in murine colon cancer (C26) xenografts, increasing plasma and tumor drug levels by approximately 150 and five-fold, respectively, compared with free CPT, leading to significantly higher tumor growth inhibition [102]. Further development has focused on creating ideal nanoparticles that protect camptothecin and prevent the hydrolysis of its lactone form. A copolymer of PEG-PCL was chosen to prepare polymeric micelles through a solvent evaporation method, resulting in optimal size and effective encapsulation of camptothecin. The nanoparticles were subsequently coated with a red blood cell (RBC) membrane, which provides “stealth” properties, enhancing circulation time and protecting camptothecin from the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and hydrolysis. When evaluating the hydrolysis rate of the nanomicelles—both with and without the RBC coating—results showed a slower rate of hydrolysis. After 1 h, only 25% of the drug had undergone hydrolysis, while after 6 h, 64% of the active lactone form of camptothecin remained intact [103]. In addition to parent CPT, the highly potent derivative SN 38 has been formulated in mixed PEG-based micellar systems by combining PEG b PCL with other amphiphiles such as Pluronic F-108 to increase the solubility of SN-38. A clear and stable micellar system with enhanced drug loading was prepared, and high antitumor efficacy against MCF-7 breast cells was demonstrated [104].

Curcumin (CUR) is a natural hydrophobic polyphenol with demonstrated anticancer activity against various solid tumors, including colon carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Its clinical application is limited by poor aqueous solubility and rapid metabolism. To address these issues, methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone) (mPEG-b-PCL) micelles have been used to encapsulate curcumin in the hydrophobic core, improving solubility, pharmacokinetics, and sustained release. These micelles significantly inhibited CT26 colon carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo and enhanced anti-angiogenic effects compared with free CUR [105]. Similarly, mPEG-b-PLA micelles loaded with curcumin increased cellular uptake and cytotoxicity in A549 NSCLC cells as well as murine melanoma (B16F10) and human breast cancer (MDA MB 231) cells, induced apoptosis, and suppressed migration and invasion more effectively than free CUR [106,107]. Beyond single-agent systems, co-delivery of curcumin with other drugs such as doxorubicin in PEG-based micelles has been shown to reverse multidrug resistance and enhance antitumor efficacy in models of drug-resistant breast cancer, although those systems combine active agents rather than solely demonstrating passive delivery of CUR [108].

3.1.2. Active Targeting of Conventional Drug-Loaded PEG-Based Polymer Micelles

Passive targeting strategies have shown several limitations, including heterogeneous tumor vasculature, variable EPR effect among tumor types, and nonspecific distribution in healthy tissues. Therefore, considerable effort is being directed toward maximizing nanoparticle accumulation and therapeutic efficacy through active targeting strategies. Site-specific delivery and cellular internalization can be achieved by functionalizing nanoparticles with ligands that recognize overexpressed receptors on tumor cell membranes, or by exploiting phagocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis mechanisms, thereby improving selective uptake and minimizing off-target effects [109]. PEG-based polymer micelles are widely employed for targeted drug delivery due to their excellent biocompatibility, prolonged circulation time, and ease of surface functionalization. The hydrophilic PEG corona provides steric stabilization and reduces nonspecific protein adsorption, while terminal functional groups on PEG chains enable conjugation of targeting ligands. Commonly used ligands include folic acid, RGD peptides, transferrin, antibodies or antibody fragments, and aptamers, which recognize receptors overexpressed on cancer cells or tumor vasculature [11,13]. Ligand-functionalized PEG micelles promote receptor-mediated endocytosis, leading to enhanced cellular uptake, increased tumor accumulation, and improved therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity compared to non-targeted micelles.

Folic acid (FA) is widely used due to its favorable properties, including its small size, nonimmunogenicity, low toxicity, and ease of conjugation. FA-functionalized micelles can efficiently deliver various anticancer agents into target tumor cells, thereby reducing nonspecific interactions with healthy tissues and enhancing site-specific drug action [110,111]. The folic receptors (FR) have been known to overexpress in several human tumors, including ovarian and breast cancers, while they are highly restricted in normal tissues [4]. Several studies have demonstrated that folate-conjugated polymer micelles exhibit enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake in folate receptor FR-positive cancer cells compared to non-folate-functionalized micelles. For instance, Park et al. developed folate-conjugated MPEG-b-PCL micelles loaded with paclitaxel (PTX), with particle sizes ranging from 50 to 130 nm depending on the molecular weight of the block copolymers. The in vitro release profile of paclitaxel from these micelles showed sustained drug release without an initial burst, indicating controlled delivery. Furthermore, paclitaxel-loaded folate-conjugated MPEG-b-PCL micelles exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity against FR-positive cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 and HeLa cells, compared to micelles lacking folate, highlighting the effectiveness of ligand-mediated targeting in enhancing therapeutic outcomes [112]. Folate-decorated diblock copolymers based on poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) loaded with doxorubicin (DOX) and free DOX mixed micelles have also been developed for targeted drug delivery. In vivo studies using a nude mouse xenograft model implanted with a human epidermal carcinoma xenograft cell line, KB cells, demonstrated that the systemic administration of these micelles led to significant tumor regression against KB cells (folate receptor positive), indicating effective tumor-targeted delivery and enhanced therapeutic efficacy [113]. Using a similar PLGA-PEG-FOL system, Zhao et al. further evaluated the selectivity and cytotoxicity of DOX-loaded micelles across cancer cell lines with varying folate receptor levels (KB, MATB III, and C6) and normal fibroblasts (CCL-110). The study showed that cytotoxicity was substantially higher in cancer cells than in normal fibroblasts, and cell cycle analysis confirmed a lower percentage of apoptotic normal cells, demonstrating the ability of folate-conjugated micelles to selectively target tumor cells while minimizing toxicity to healthy tissues [114]. Folic acid-modified PEG-PLGA (FA-PEG-PLGA)-based micelles were also developed for the co-delivery of cisplatin (CDDP) and paclitaxel (PTX), which were encapsulated in the hydrophobic core and chelated to the middle shell, respectively, while PEG formed the outer corona for prolonged circulation. In vitro, the dual-drug-loaded nanomicelles showed a highly synergistic inhibition of both FA receptor-negative A549 and FA receptor-positive M109 lung cancer cells. In vivo, CDDP+PTX nanoparticles achieved tumor suppression rates of 89.96% for A549 xenografts and 95.03% for M109 xenografts, which are significantly higher than those of free chemotherapy drug combinations or nanoparticles with a single drug. These results indicate that FA-PEG-PLGA-based co-delivery of CDDP and PTX offers an effective and safe strategy for targeted cancer chemotherapy, particularly for FA receptor-expressing tumors [115]. In addition, folate-targeted mixed micelles were also prepared by folate-poly(ethylene glycol)-distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (FA-PEG-DSPE) and methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol)-distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (MPEG-DSPE) to encapsulate the anticancer agent 9-nitro-camptothecin (9-NC). These micelles were evaluated against three tumor cell lines (HeLa, SGC7901, and BXPC3). The optimal molar ratio of FA-PEG-DSPE to MPEG-DSPE was determined to be 1:100, which allowed for efficient solubilization of 9-NC, reduced uptake by macrophages in vitro, and exhibited higher antitumor activity to the tumor cells (pancreatic cancer cell line, human uterine cervix cancer cell line, and human gastric cancer cell line) with overexpressed folate receptors on cell surface in comparison with folate-free micelles or free anticancer agents [116].

RGD-containing peptides are also widely used as tumor-targeting ligands, which were first developed by Kessler et al. [117] to target the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin receptors [118]. Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of alpha (α) and beta (β) subunits that mediate cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell–cell adhesion. They serve as physical and functional links between the ECM and cytoskeletal control pathways, transducing bidirectional signals across the plasma membrane [119]. These receptors are overexpressed in angiogenic tumor endothelial cells, as well as in a wide variety of solid tumors [120]. Poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(ethylene glycol) (PCL-b-PEG) block copolymer micelles loaded with doxorubicin (DOX) and surface-conjugated with the cyclic pen-tapeptide c (Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Lys) (cRGD) were developed for the selective delivery of DOX to angiogenic tumor endothelial cells overexpressing αvβ3 integrins. This targeting strategy exploits the high binding affinity and selectivity of cRGD toward the αvβ3 integrin. Remarkable increase in the uptake of micelles in the SLK cells upon attachment of cRGD molecules to the micelle surface was observed, and maximum ~30-fold enhancement in cellular uptake was achieved with 76% cRGD-functionalized DOX-loaded micelles compared with non-functionalized DOX-loaded micelles, demonstrating the strong potential of cRGD-mediated targeting for angiogenesis-directed cancer therapy [121]. Zhan et al. evaluated cRGD-conjugated PEG-b-PLA micelles as drug carriers for paclitaxel to treat integrin αvβ3 overexpressed glioblastoma. It was shown that while the drug-loaded PEG-PLA micelles and Taxol® arrested tumor growth in mice bearing U87MG s.c. xenografts, cRGD-conjugated paclitaxel micelles exhibited the most potent tumor growth inhibition [122]. The treatment with cRGD-conjugated paclitaxel micelles resulted in the longest survival time in intracranial U87MG tumor-bearing mice. Similarly, RGD-functionalized PEG-b-PLA micelles loaded with curcumin (Cur-RPP) were prepared using the thin-film hydration method. The cellular uptake of Cur-RPP was significantly higher than that of non-RGD-modified micelles, due to the specific binding between the αvβ3 integrin and RGD ligands in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and mouse melanoma B16 cell lines. In B16 tumor-bearing mice, Cur-RPP exhibited a stronger tumor growth inhibition compared with non-RGD-modified micelles, highlighting the effectiveness of RGD-mediated targeting in enhancing therapeutic efficacy [123].

Transferrin (Tf) is another ligand used for active drug delivery systems. It is a cell membrane-associated glycoprotein involved in the cellular uptake of iron and in the regulation of cell growth. Iron uptake occurs via internalization of iron-loaded transferrin mediated by the transferrin receptor (TfR). As a targeting moiety, transferrin triggers receptor-mediated endocytosis in cells that highly express TfR, which include many cancer types [124]. For example, transferrin (Tf) was conjugated onto the surface of appropriately modified PEG-b-PLA block copolymer micelles with loaded paclitaxel (PTX) to enable active tumor targeting. The antitumor efficacy of these Tf-functionalized micelles was evaluated in gastric carcinoma models overexpressing the transferrin receptor (TfR). Analysis of tumor volume progression, together with histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor sections, demonstrated that Tf-modified PTX-loaded micelles exhibited the strongest antitumor activity compared with the control groups, including saline, free PTX, and non-targeted PTX-loaded micelles [125]. More recently, a glioma-targeted drug delivery system was developed using PTX-loaded PEG-PLA polymeric micelles decorated with the transferrin receptor-targeting peptide TfR-T12, enabling efficient transport across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and specific recognition of glioma cells. In vitro cellular uptake and cytotoxicity studies demonstrated significantly enhanced internalization of TfR-T12/PEG-PLA micelles in U87MG glioma cells, accompanied by superior anticancer activity compared with non-targeted micelles. This enhanced performance was attributed to the presence of the TfR-T12 ligand on the micelle surface, which selectively binds to the overexpressed transferrin receptors (TfRs) on U87MG cells. In vivo biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy studies in tumor-bearing mice further confirmed the advantages of this targeting strategy. Following intravenous administration, TfR-T12/PEG-PLA-PTX micelles exhibited improved tumor accumulation and significantly enhanced antitumor activity, as evidenced by reduced tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, along with increased apoptosis, compared with non-targeted PEG-PLA-PTX micelles [126].

Antibodies offer the greatest versatility due to their broad target range and high binding specificity. Antibody-targeted micelles, or immunomicelles, can be prepared by chemically attaching antibodies or antibody fragments to the activated, water-exposed ends of the hydrophilic block of the micelle-forming polymer. This functionalization enables the micelles to selectively bind antigens or receptors overexpressed on tumor cells, enhancing targeted drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy [5,127]. It was shown that certain non-pathogenic monoclonal antinuclear autoantibodies with nucleosome-restricted specificity, such as monoclonal antibody 2C5 (mAb 2C5), selectively recognize the surface of a wide range of tumor cells, but not normal cells, via tumor cell surface-bound nucleosomes. Due to their ability to bind diverse cancer cells, these antibodies can serve as specific ligands for the targeted delivery of drugs and nanocarriers into tumors, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. By adapting the coupling technique, PEG-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-based immunomicelles modified with mAb 2C5 with nucleosome-restricted specificity reactive toward a variety of different cancer cells were developed [128]. The intravenous administration of tumor-specific 2C5 immunomicelles based on PTX-loaded PEG-PE into experimental mice bearing murine Lewis lung carcinoma resulted in an increased accumulation of PTX in the tumor compared with free drugs or drugs in non-targeted micelles and in an enhanced tumor growth inhibition in vivo [129]. In another more recent example, doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded polymeric immunomicelles made from poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-PEG (DOX–PLGA-PEG) and targeted with the bivalent fragment HAb18 F(ab′)2 against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were developed. The therapeutic action of micelles improved owing to specific molecular targeting and a higher uptake by the HCC cell lines HepG2 and Huh7 in vitro. The targeted micelles also suppressed in vivo tumor growth significantly (63.9%) when compared to free DOX (39.8%) or DOX-PLGA-PEG (50.2%) in HepG2 xenograft-bearing nude mice [130].

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a cell-surface receptor for the members of the epidermal growth factor family (EGF-family) and is overexpressed on the surface of a number of different human cancer cells, including colorectal, breast, and lung cancer cells [131]. Recently, the possibility of using an EGF-conjugated polymer micelle as a vehicle for targeting hydrophobic drugs to EGFR-overexpressing cancers has been investigated. For example, Zeng et al. [132] reported an EGF-conjugated PEG-b-poly (d-valerolactone) (PGG-b-PVL) micelle system that targets the EGF receptors overexpressed by breast cancer cells. These micelles were shown to localize in the nucleus of the MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells and the perinuclear region. Thus, EGF conjugates are useful for nuclear targeting, which is critical for the delivery of anticancer drugs whose site of action is located in the nucleus. In another system, anti-EGFR antibodies were conjugated to PEG-b-PCL block copolymer micelles for active targeting of EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells. Doxorubicin (DOX) was encapsulated in the micelle core (DOX-micelle), and RKO colorectal cancer cells were treated with free DOX, DOX-micelles, or DOX-anti-EGFR-micelles. Free DOX is primarily localized to the nuclei, whereas DOX-micelles accumulate in the cytoplasm. Notably, DOX-anti-EGFR-micelles induced significantly higher apoptosis than free DOX or non-targeted DOX-micelles, demonstrating that antibody-functionalized micelles are an effective strategy for targeted delivery of cytotoxic drugs to EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells [133].

Aptamers (Apts) offer several distinct advantages, including nonimmunogenicity, small molecular size, ease of chemical synthesis and modification, and high batch-to-batch reproducibility compared to antibodies. They are DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold into well-defined three-dimensional structures through intramolecular interactions, enabling them to bind target molecules with high affinity and specificity in a manner analogous to antibodies [134]. Since their discovery through in vitro selection techniques, aptamers have attracted significant attention as targeting ligands in drug delivery systems, since they exhibit remarkable physicochemical stability, retaining their binding activity over a broad range of pH values (≈4–9), temperatures, and even in the presence of organic solvents. These favorable properties make aptamers particularly attractive as targeting moieties for nanoparticle and polymer micelle-based drug delivery applications [135]. For example, docetaxel (Dtxl)-loaded PLGA-b-PEG polymeric micelles functionalized with A10 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA aptamers targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) were developed for prostate cancer therapy. The aptamer-decorated micelles exhibited significantly enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity compared with non-targeted nanoparticles. Following a single intratumoral administration in LNCaP xenograft nude mice, the targeted formulation achieved complete tumor regression in five out of seven animals and 100% survival over 109 days, markedly outperforming non-targeted micelles and free Dtxl. In contrast, saline and drug-free nanoparticles showed no therapeutic efficacy [136]. Similarly, Pt(IV) compound (hydrophobic Pt(IV) prodrug with axial alkyl chains) was successfully loaded into PEG-b-PLGA micelles functionalized with the A10 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA aptamer targeting PSMA. Following cellular uptake, intracellular reduction in the Pt(IV) prodrug resulted in the controlled release of active cisplatin. In vitro cytotoxicity assays performed in PSMA-positive LNCaP and PSMA-negative PC3 cells demonstrated that PSMA aptamer-targeted Pt(IV)-encapsulated PLGA-b-PEG micelles exhibited significantly enhanced anticancer activity. Notably, in PSMA-positive LNCaP cells, the targeted nanoparticles were approximately 80-fold more cytotoxic than free cisplatin, while showing significantly lower toxicity toward PSMA-negative PC3 cells [137].

3.2. Conventional PVP-Based Polymer Micelles for Drug Delivery

3.2.1. Passive Targeting of PVP-Based Polymer Micelles for Drug Delivery

Although PEG-based micelles are among the most widely investigated drug delivery systems for cancer therapy, a recent study demonstrated that the multiple use of PEGylated drugs can lead to the development of anti-PEG antibodies (APAs), thereby accelerating drug clearance, decreasing therapeutic efficacy, and increasing the risk of adverse reactions, such as hypersensitivity. Pre-existing APAs have also been found in people without previous exposure to PEGylated drugs, which raises additional clinical concerns [138]. An alternative to PEG is poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP), which can be effectively utilized as an appropriate hydrophilic polymer in drug delivery systems. PVP is known for its excellent biological and physicochemical properties, such as high water solubility, low toxicity, biocompatibility, complexation capability, cryo-protectivity, lypoprotectivity, and anti-biofouling properties [139]. However, very few reports on the synthesis and characterization of PVP-based copolymers as drug delivery micellar systems for cancer therapy are available in the literature. More research is needed to better understand their potential and to demonstrate their importance in modern nanomedicine.

- Taxane-Class Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-block-poly(D,L-lactide) (PVP-b-PDLLA) copolymer was successfully used as a nano-micellar drug carrier for taxanes such as paclitaxel (PTX) and docetaxel (DCTX). PTX-loaded micelles were chosen as a model and evaluated in vitro on three different cancer cell lines: mammary carcinoma tumor EMT-6 cells, murine colon adenocarcinoma tumor C26, and human OVCAR-3 cells. The cytotoxicity experiments showed that each cell line exhibited different sensitivities to the drug, as the OVCAR-3 cells were the most sensitive to PTX, in contrast to C26 cells, which were relatively resistant to this drug. The antitumor activity of the PTX-loaded micelles against solid tumors tested in vivo on mice bearing murine C26 colon adenocarcinoma cells demonstrated that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached, even at 100 mg/kg, in comparison to the MTD of Taxol®, where the established value was 20 mg/kg. At a 60 mg/kg dosage, PM-PTX demonstrated greater in vivo antitumor activity than Taxol® injected at its MTD [140]. Next, triblock PVP-PDLL-PVP copolymers and star-(PDLLA-b-PVP)4 copolymers were evaluated as drug micellar carriers of PTX. It was determined that the self-assembling behavior and loading efficiency of PTX depend on their composition [141]. Similarly, paclitaxel (PTX) was loaded into poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PVP-b-PCL) micelles via a modified nano-precipitation method. The antitumor effect of PTX-loaded micelles was evaluated in vitro on three different cancer cell lines, including human gastric carcinoma cell line BGC 823, human oral epidermoid carcinoma cell line KB, and murine hepatic carcinoma cell line H22. The observed differences in the cytotoxicity among the tested cell lines are likely due to their genetic backgrounds and biological behaviors. The in vivo examinations tested on a hepatic H22 tumor-bearing mice model (i.v.) exhibit a significantly superior antitumor effect than the commercially available Taxol® formulation [142].

- Anthracycline-Class Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

A well-defined poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PVP-b-PCL) copolymer was synthesized by ROP of CL and controlled metal-free xanthate-mediated RAFT polymerization of NVPA. This copolymer was used to encapsulate doxorubicin (DOX) via the dialysis method, resulting in the formation of DOX-loaded micelles. The micelles showed enhanced growth inhibition and cytotoxicity against both parental and DOX-resistant human (K-562, JE6.1, Raji) as well as mice lymphoma cells (DL) (Dalton’s lymphoma, DL). They demonstrated a higher tumoricidal effect against DOX-resistant tumor cells compared to free DOX. It was found that additional treatment with DOX-loaded micelles did not affect the viability of normal blood cells, such as monocytes, dendritic cells, or lymphocytes (93.26%), whereas free DOX reduces their viability to 60.87% [139].

Additionally, mixed polymer micelles based on poly(vinyl pyrrolidone-b-polycaprolactone) (PVP-b-PCL) and poly(vinyl pyrrolidone-b-poly(dioxanone-co-methyl dioxanone)) (PVP-b-P(DX-co-MeDX)) copolymers were also prepared. These micelles were successfully loaded with various anticancer drugs from different classes, including gemcitabine (GEM) doxorubicine.HCl (DOX.HCl), doxorubicin. NH2 (DOX), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and paclitaxel (PTX). Hydrophobic drugs demonstrated a higher loading percentage efficiency compared to hydrophilic drugs, with the following trend: PTX > DOX > 5-FU > GEM > DOX.HCl. However, the drug release pattern followed the opposite trend due to a decrease in polymer–drug interaction. The physically mixed GEM and DOX.HCl-loaded micelles were selected as a model and tested against PANC-1 and BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer cell lines. The results demonstrated greater toxicity against PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines compared to mixed free drugs and single-loaded micelles. This observation is probably due to their similar size and release kinetics profiles, which enhance the synergistic or additive drug effect of the drugs [143].

- Natural compound Drugs’ Micellar Formulations

Tetrandrine (Tet) is a bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloid isolated from the root of hang-fang-chi (Stephania tetrandra S Moore). It was identified as a promising anticancer drug due to its antitumor effectiveness against a wide range of cancers, including lung, breast, colon, liver, prostate, gastric, ovarian, pancreatic, cervical, bladder, and glioma cancers [144]. In this respect, poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-block-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PVP-b-PCL)-based micelles with high loading efficiency of Tet were prepared via the nanoprecipitation method. The cellular uptake test conducted on human non-small cell lung cancer cell line A549 showed that the uptake of Tet-NPs is mainly mediated by the endocytosis of the micelles and causes their apoptosis by inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins. These results confirm the potential of Tet-loaded micelles in lung cancer treatment and represent an effective strategy for improving its anticancer efficacy [145].

Recently, amphiphilic derivatives of poly-N-vinylpyrrolidone, with terminal hydrophobic long-chain n-alkyl fragments of different lengths, have gained attention due to their ability to self-assemble in aqueous media. These amphiphiles can form core–shell type polymeric nanoparticles, which are effective to entrap various hydrophobic biologically active agents in their inner core [146].

In this respect, poly-N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone with thiooctadecyl end-group (PVP-OD) was synthesized and used as a nanocarrier for curcumin. Emulsification and ultrasonic dispersion methods were applied for the formation of curcumin-loaded nanocarriers and tested on two cell lines: U87 glioblastoma and CRL 2429 fibroblast cells as model systems. It was found that this delivery system exhibits two distinct mechanisms of cell penetration, depending on the preparation methods, by endocytosis mechanisms or by diffusion through the cell membrane via non-endocytic mechanisms. As a result, by precisely tailoring the size of polymeric carriers, they can effectively deliver hydrophobic drugs to all cell compartments, including the nucleus [147].

3.2.2. Active Targeting of Drug-Loaded PVP-Based Micelles

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a type II transmembrane protein and a member of the TNF family. It induces apoptosis in transformed or tumor cells, making it a promising selective anticancer agent [148]. Therefore, amphiphilic poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) nanoparticles consisting of unmodified and maleimide-modified polymeric chains (1:1) were covalently conjugated with antitumor DR5-specific TRAIL variant DR5-B to overcome the receptor-dependent TRAIL-resistance of tumor cells. The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was studied in 2D and 3D in vitro models, including human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells, human colorectal carcinoma HCT116, and colorectal adenocarcinoma HT29 cells. These formulations were found to enhance cytotoxicity effects compared to the free DR5-B in both 2D (monolayer culture) and 3D (tumor spheroids) in vitro models. Importantly, the conjugation of DR5-B with Amph-PVP nanoparticles increased the sensitivity of resistant multicellular tumor spheroids derived from MCF-7 and HT29 cells. However, further improvement is necessary to create a versatile system for targeted drug delivery using click chemistry [149]. More recently, amphiphilic PVP nanoparticles were loaded with bortezomib (BTZ)—a proteasome inhibitor—and further decorated with the TRAIL variant DR5-B (PVP-BTZ-DR5-B). The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was studied in vitro on 2D and 3D cultures of human glioblastoma cell lines U87MG and T98G. The results demonstrated that PVP-BTZ-DR5-B nanoparticles were internalized and accumulated in the cells more efficiently, demonstrating significantly enhanced cytotoxicity compared to free DR5-B or PVP-BTZ nanoparticles. Additionally, they penetrated the blood–brain barrier more effectively than DR5-B. The enhanced antitumor effect of PVP-BTZ-DR5-B was also demonstrated in a xenograft model of U87MG glioblastoma cells using zebrafish embryos in vivo. Therefore, the present system is a promising approach to enhance the antitumor efficacy of free drugs and overcome glioblastoma resistance [150]. In another example, amphiphilic N-vinylpyrrolidone nanoparticles with bortezomib (BTZ) were modified either with DR5-selective TRAIL cytokine (DR5-B) or its fusion with the iRGD peptide (DR5-B-iRGD), resulting in AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B and AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD formulations. The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was tested on pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines PANC-1, BxPC-3, and MIA PaCa-2. Both types of nanoparticles were found to inhibit the growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines to a great extent. Additionally, they promoted a more rapid internalization of the DR5 receptor in MIA PaCa-2 cells compared to unmodified particles and free forms of DR5-B or DR5-B-iRGD. Notably, AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD demonstrated a more pronounced rate of DR5 internalization and a stronger cytotoxic effect than AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B, which can be attributed to the inclusion of a fusion protein containing the internalizing iRGD peptide. High cytotoxicity against pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells without significant cytotoxicity on healthy cells makes them promising candidates for pancreatic cancer therapy [151].

4. Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Micelles

Stimuli-responsive micelles are formed using intelligent polymers, commonly known as “smart” or stimuli-responsive polymers. What makes these polymers unique is their ability to undergo significant changes in characteristics with only slight variations in external factors, such as temperature, pH levels, or the presence of enzymes or biomolecules. The primary focus in this review is on pH-sensitive and temperature-sensitive PEG-based micelles derived from their respective stimuli-responsive polymers.

4.1. pH-Sensitive PEG-Based Polymer Micelles

The extracellular pH of normal tissues and blood is 7.4, which tends to be lower in tumor tissues. The pH of most extracellular tumors has values between pH 6.5 and 7.2. However, the pH can even be down at the intracellular level. The reported values range from 5.0 to 6.0 in endosomes and 4.0 to 5.0 in lysosomes. For this reason, the acidity in the extracellular and intracellular compartments constitutes an essential signal for targeting [152].

pH-sensitive polymer micelles are obtained from amphiphilic block copolymers whose polymer chains contain functional groups capable of accepting or donating protons upon changes in the pH of the environment. They are part of the so-called “smart” polymer systems, which can respond to changes in the external pH. Depending on the nature and location of the pH-responsive groups in the polymer, pH-sensitive polymers are classified into two main groups: (i) Polymers that contain ionizable groups in the side chain of the polymer, which are further divided into cationic and anionic polymers [153], and (ii) polymers that contain acid/base-labile linkages in the polymer chain. These are generally stable at pH 7.4 but hydrolyze under mild acidic conditions. The most commonly used acid-labile linkages include hydrazones, acetals/ketals, oximes, orthoesters, and cis-aconityl [154,155].

4.1.1. Polymeric Nanomicelles for Tumor pH Targeting by a Destabilization Mechanism

Polymer micelles from polymers with ionizable groups can provide drug release because of a change in the pH of the environment. The pH values at which the polymer micelle breaks down and the release occurs depend on the copolymer composition. The advantage of pH-sensitive polymer micelles is that they are stable at certain pH values, but at other values, the hydrophilicity or conformation of the chains changes, causing the micelles to break down and release the substance encapsulated in them. The number of micelles that disintegrate or destabilize, and therefore the release profile, depends on the intensity of the stimulus (the degree of pH change). Once the stimulus stops, the micelles reform, and the release is interrupted [153].

Poly(L-histidine) is the most commonly used pH-sensitive component in micelle-based pH-triggered release systems since this polymer contains an imidazole ring, which has a lone pair of electrons on its unsaturated nitrogen, allowing it to act as both a base (by protonation) and an acid (when already protonated). This makes the polymer amphoteric, switching its nature between hydrophobic (at neutral pH 7.4) and hydrophilic (in acidic environments) [156]. Polymeric micelles based on poly (L-histidine) that undergo destabilization in response to the acidic tumor extracellular pH were first systematically developed by Bae and co-workers [157,158,159]. These pH-responsive micelles consisting of poly(L-histidine)-b-poly(ethylene glycol) diblock copolymers (polyHis-PEG) with loaded doxorubicin (DOX) were prepared at pH 8.0 using the dialysis method and aim to exploit the protonation behavior of imidazole groups within the poly(histidine) segment [158]. In this system, the PEG block remains hydrophilic at all pH ranges, thus providing steric stabilization and prolonged circulation, while the poly(L-histidine) block exhibits pH-dependent amphiphilicity. At pH values above the pKb of poly(histidine) (≈6.5), deprotonation of the imidazole rings renders the polyHis block hydrophobic, driving the self-assembly of the copolymer into stable micelles with diameters of approximately 110 nm. When exposed to mildly acidic conditions (pH < 7.4), protonation of the imidazole groups increases the hydrophilicity of the polyHis block, leading to micelle destabilization and swelling. The destabilization induced by pH changes enables the triggered release of doxorubicin (DOX) from the micellar core. However, the release of DOX begins at pH levels slightly above the typical extracellular pH found in tumors, which indicates a significant limitation and necessitates the optimization of pH-responsive micellar systems. To enhance pH sensitivity, a mixed micelle system was developed using polyHistidine-polyethylene glycol (polyHis-PEG) block copolymers (75 wt%) and poly(L-lactic acid)-polyethylene glycol (PLLA-PEG) block copolymers (25 wt%). The micelles have an average diameter of 70 nm at pH 9.0 and are destabilized below pH 7.0. Drug release profiles showed that 32 wt%, 70 wt%, and 82 wt% of DOX were released at pH 7.0, 6.8, and 5.0, respectively, within the first 24 h. Cytotoxicity studies demonstrated that blank micelles did not exhibit significant toxicity in MCF-7 cells at concentrations up to 100 mg/mL. In contrast, DOX-loaded pH-responsive mixed micelles (PHSM) effectively killed tumor cells at pH 6.8. In vivo studies using an MCF-7 xenografted mouse model revealed that DOX-loaded PHSM (10 mg/kg) significantly inhibited tumor growth, while mice treated with free DOX experienced more weight loss compared to those treated with the PHSM formulations [160]. To facilitate the micelle formation process and to adjust the pH sensitivity, a biodegradable PLA-b-PEG-b-polyHis block copolymer was synthesized, and DOX-loaded flower-like polymer micelles were prepared. An in vitro cell cytotoxicity test conducted with the DOX-loaded PLA-b-PEG-b-polyHis micelles against MCF-7 cells demonstrated that they effectively killed the tumor cells at lower pH levels due to an increased amount of released DOX. The viability of MCF-7 cells treated with the DOX-loaded PLA-b-PEG-b-polyHis micelles was found to be 87% at pH 7.4, 40% at pH 6.8, 30% at pH 6.4, and 26% at pH 6.0 [161]. Furthermore, active targeting pH-sensitive polymer micelles were prepared by Bae et al., who developed pH-sensitive mixed micelles composed of folate-linked PEG-b-poly(L-lactide) (folate-PEG-PLLA) and PEG-b-poly(L-histidine) (PEG-polyHis) block copolymers [162]. The cytotoxicity test performed in 4T1 s.c. xenograft-bearing mice showed that DOX-loaded PEG-polyHis/folate-PEG-PLLA mixed micelles possessed significant anticancer efficacy in terms of tumor growth inhibition, improved survival, and reduced metastasis, compared to the free drug, the drug-loaded PEG-polyHis micelles, and the PEG-PLLA micelles. Additionally, the authors evaluated a second generation of pH-sensitive micelles (PHSM) composed of PEG-b-poly(L-histidine-co-L-phenylalanine) (PEG-poly(His-co-Phe)) and folate-PEG-PLLA for the delivery of doxorubicin [163]. They found that PHSM formulation resulted in a 4-fold and 10-fold increase in doxorubicin level in the tumor over PHIM and the free drug, respectively. In mice bearing multidrug-resistant ovarian A2780/DOXR s.c. xenografts, doxorubicin-loaded PHSM almost completely arrested tumor growth, whereas only modest inhibition was observed with the PHIM formulation (Figure 5). These studies strongly suggest that the combined mechanism of folate targeting and pH sensitivity of the mixed micelles contributes to enhanced drug delivery and efficacy in the tumor.

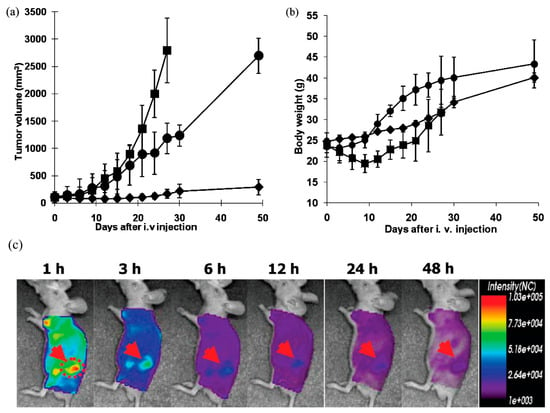

Figure 5.

In vivo tumor growth inhibition test and body weight change in s.c. ovarian A2780/DOXR xenografted BALB/c nude mice (n = 7). A total of 10 mg/kg of DOX equivalent dose was injected as several formulations, including free DOX in PBS (■), DOX-loaded pH-insensitive micelles (DOX/PHIM-f) (●), and DOX-loaded pH-sensitive micelles (DOX/m-PHSM(20%)-f) (♦). Three IV injections on days 0, 3, and 6 were made. Values are the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). (a) Tumor volume change; (b) body weight changes; (c) In vivo optical fluorescence imaging of KB tumor xenografted BALB/c nude mice after DOX encapsulated and Cy 5.5 fluorescent dye labeled pH-sensitive micelles. Arrows indicate the location of the tumor (reproduced with the permission of ACS) [163].

Tsai et al. reported a mixed micelle system composed of folate-PEG-PLA and poly(2-HEMA-co-histidine)-g-PLA as a pH-sensitive carrier for doxorubicin [164]. Results from the NIR imaging study indicated that the mixed micelles accumulated in the tumor to a greater extent, even though they were more rapidly eliminated from the circulation than the non-targeted micelles. In cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa s.c. xenograft-bearing mice, doxorubicin-loaded folate micelles displayed more potent tumor growth inhibition than free doxorubicin and the non-targeted micelles.