The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19

Abstract

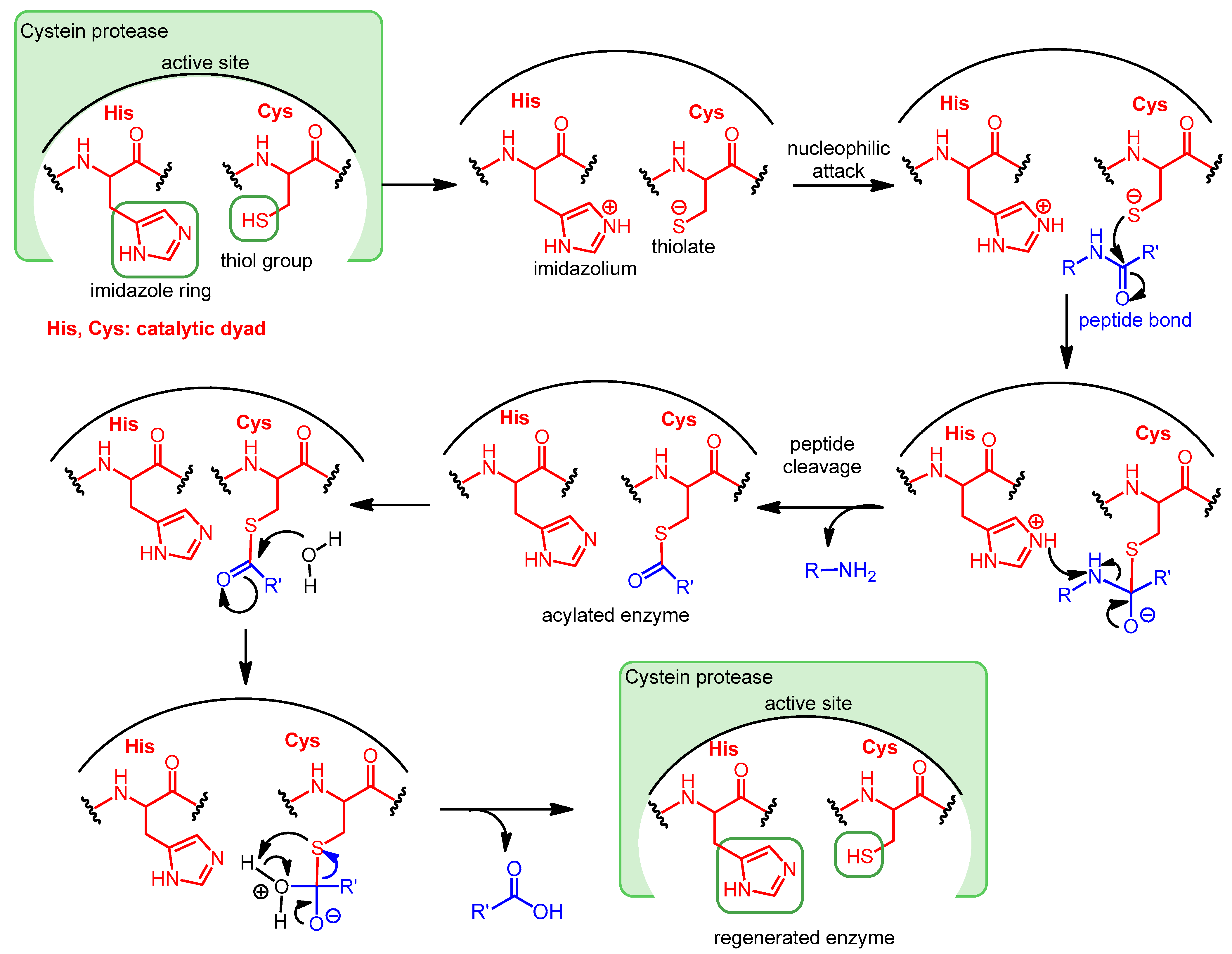

1. Introduction—Viral Proteases as Drug Targets

2. Protease Inhibitors as Antivirals

2.1. Protease Inhibitor Drugs for the Treatment of HCV and HIV Infections

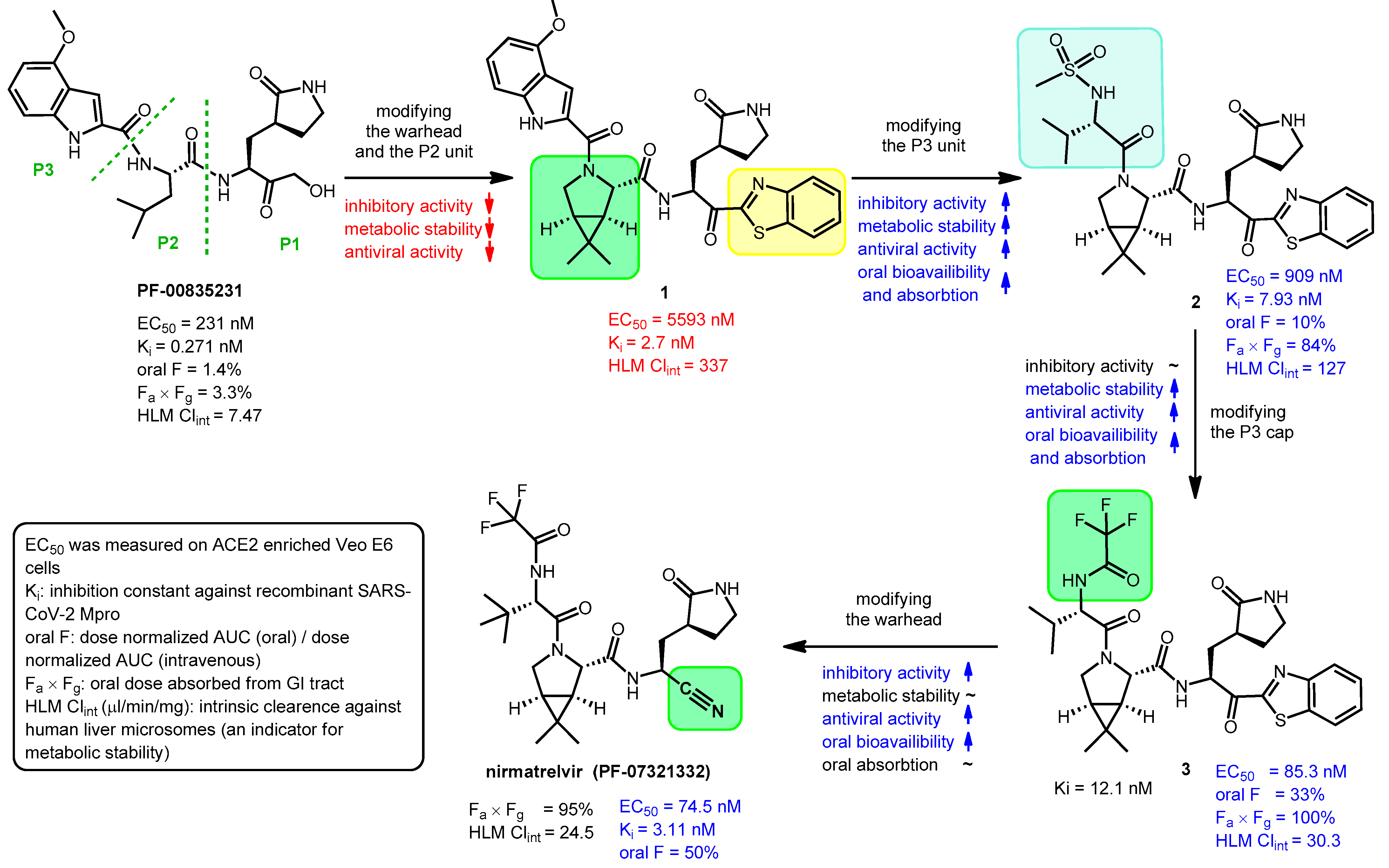

2.2. Development and Mechanism of Action of Nirmatrelvir

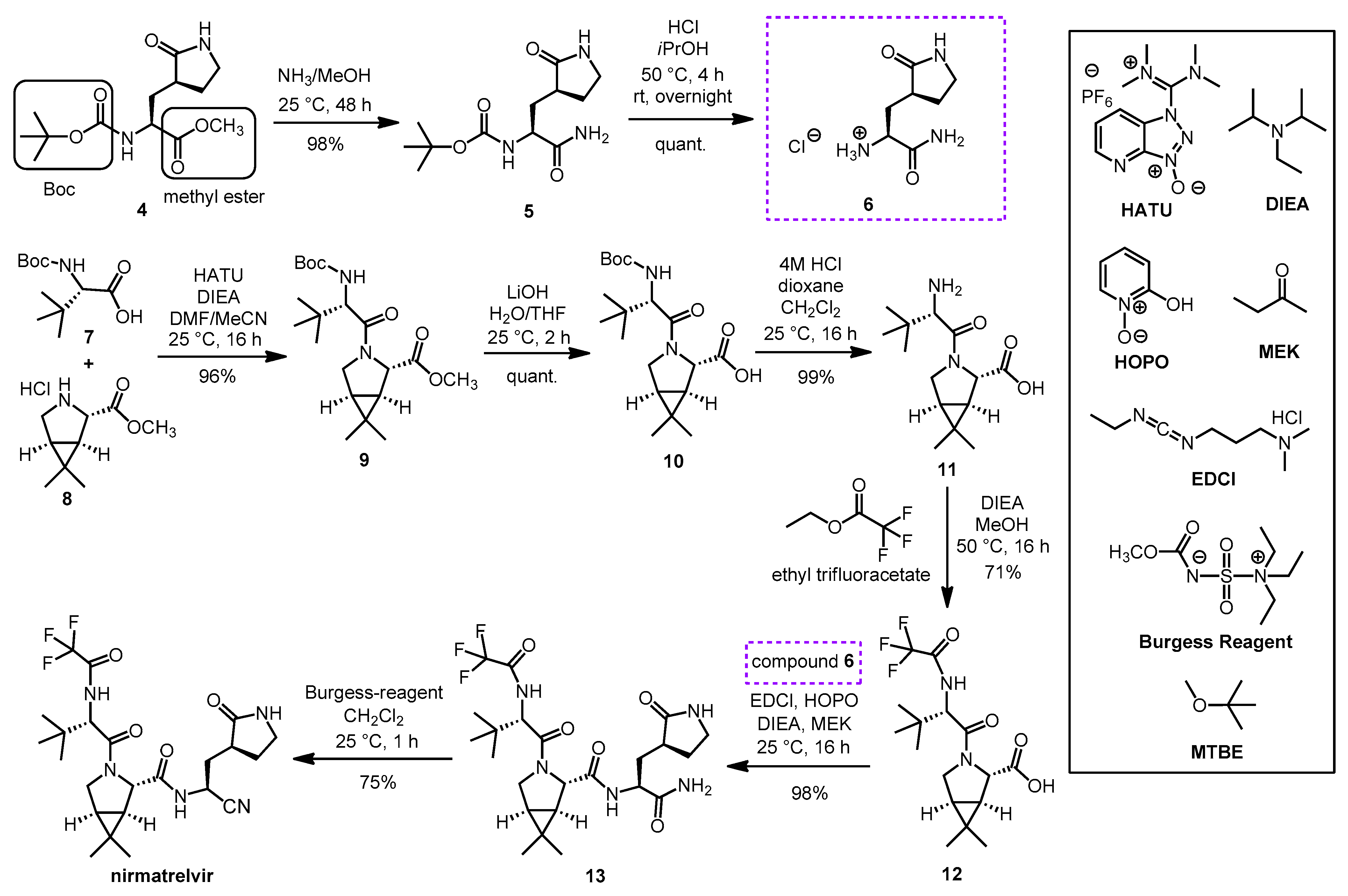

2.3. Synthesis of Nirmatrelvir

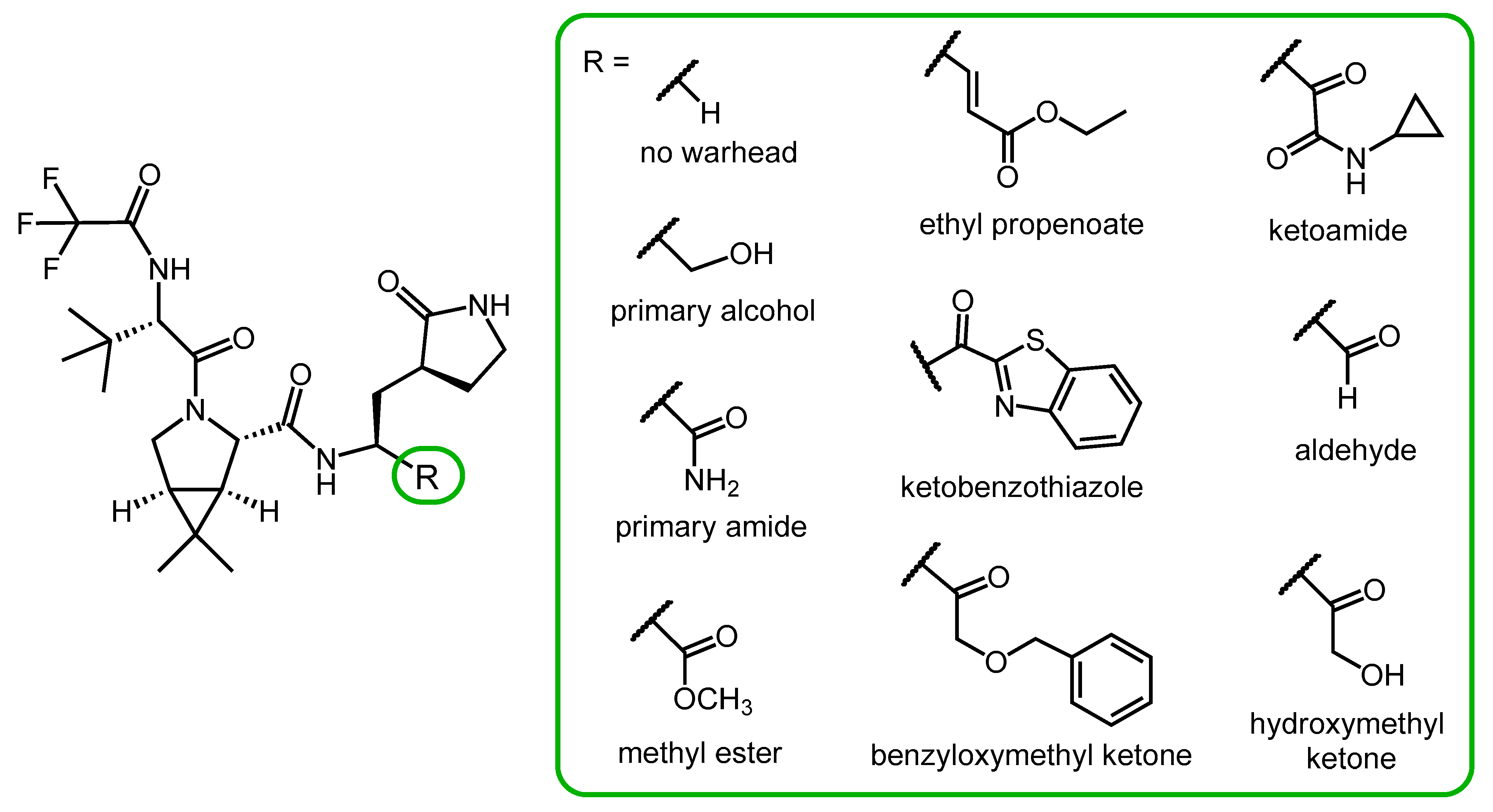

2.4. Synthesis and SAR Study of Nirmatrelvir Analogs

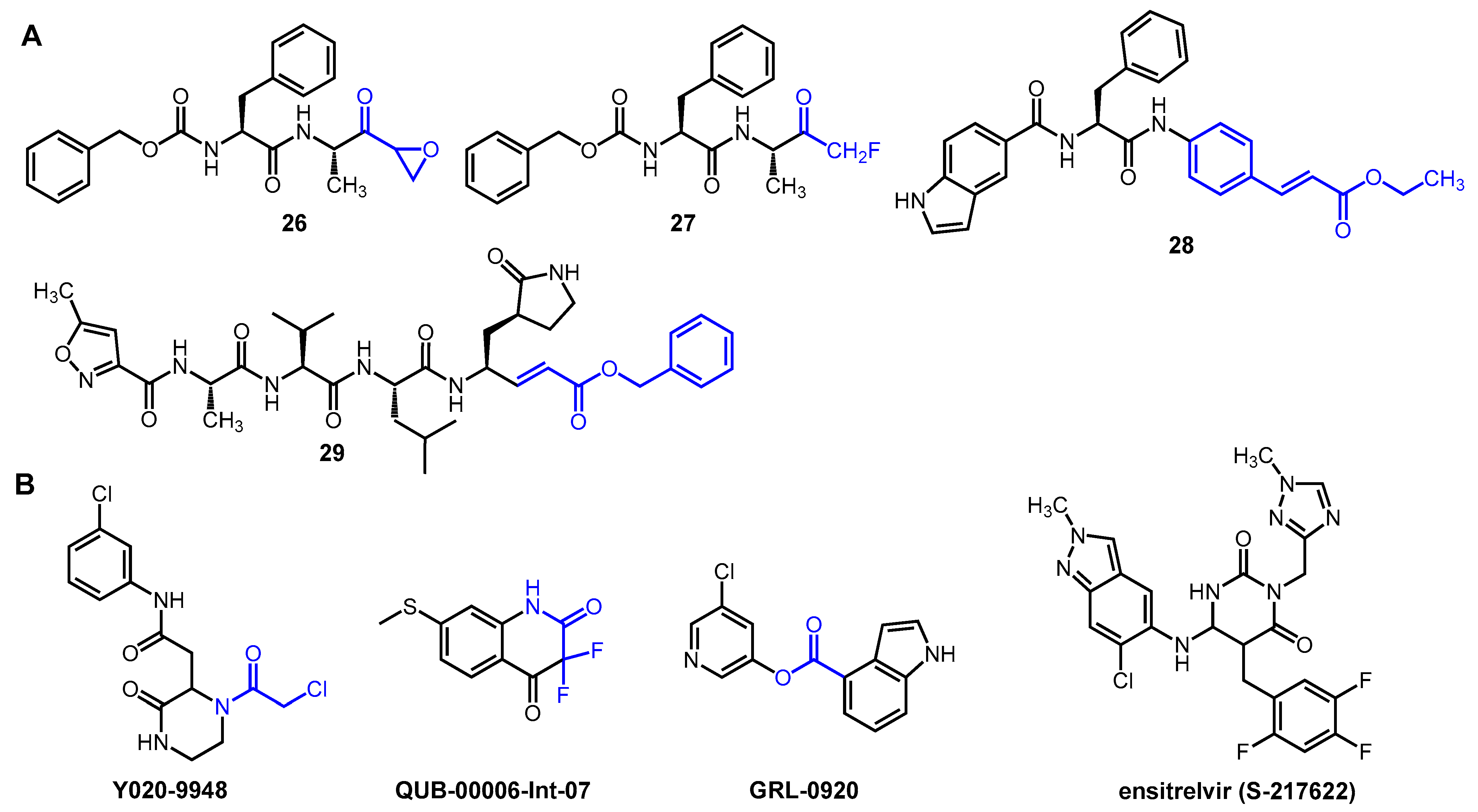

2.5. Novel Covalent and Non-Covalent Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

3. Ritonavir as a Pharmacokinetic Enhancer

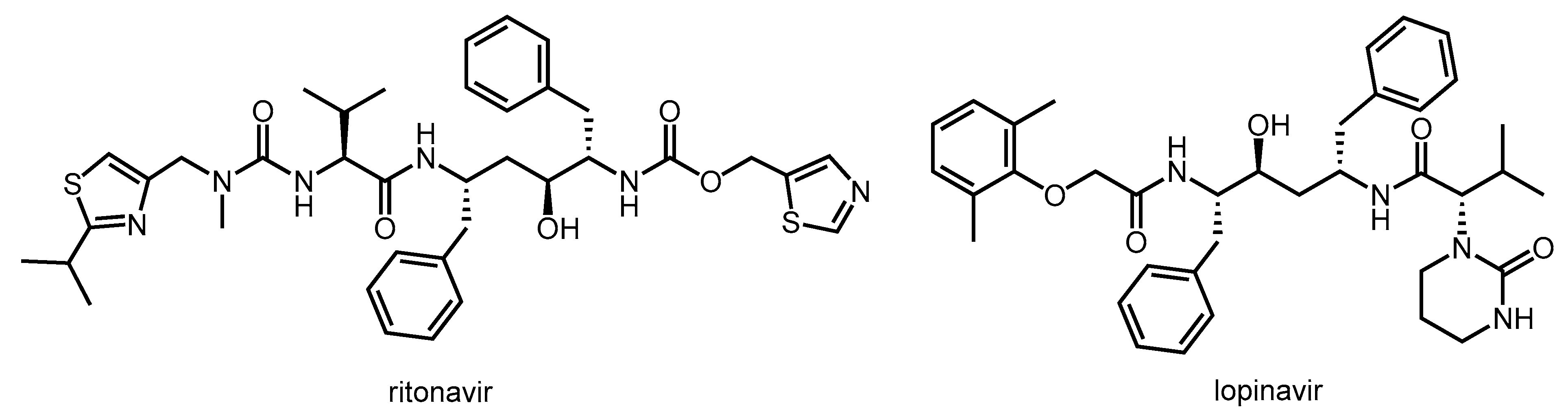

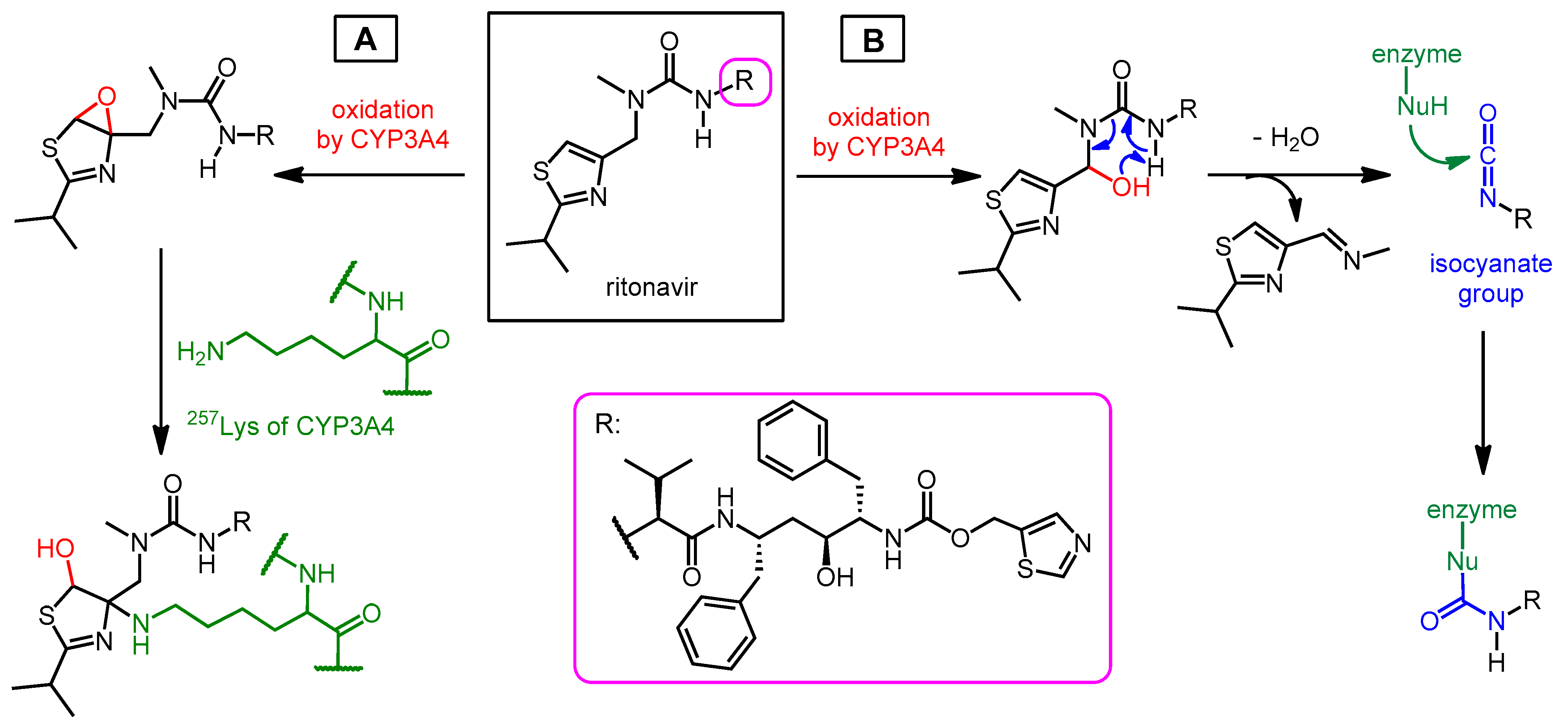

3.1. Structure, Enzyme Inhibitory Activity and Drug–Drug Interactions of Ritonavir

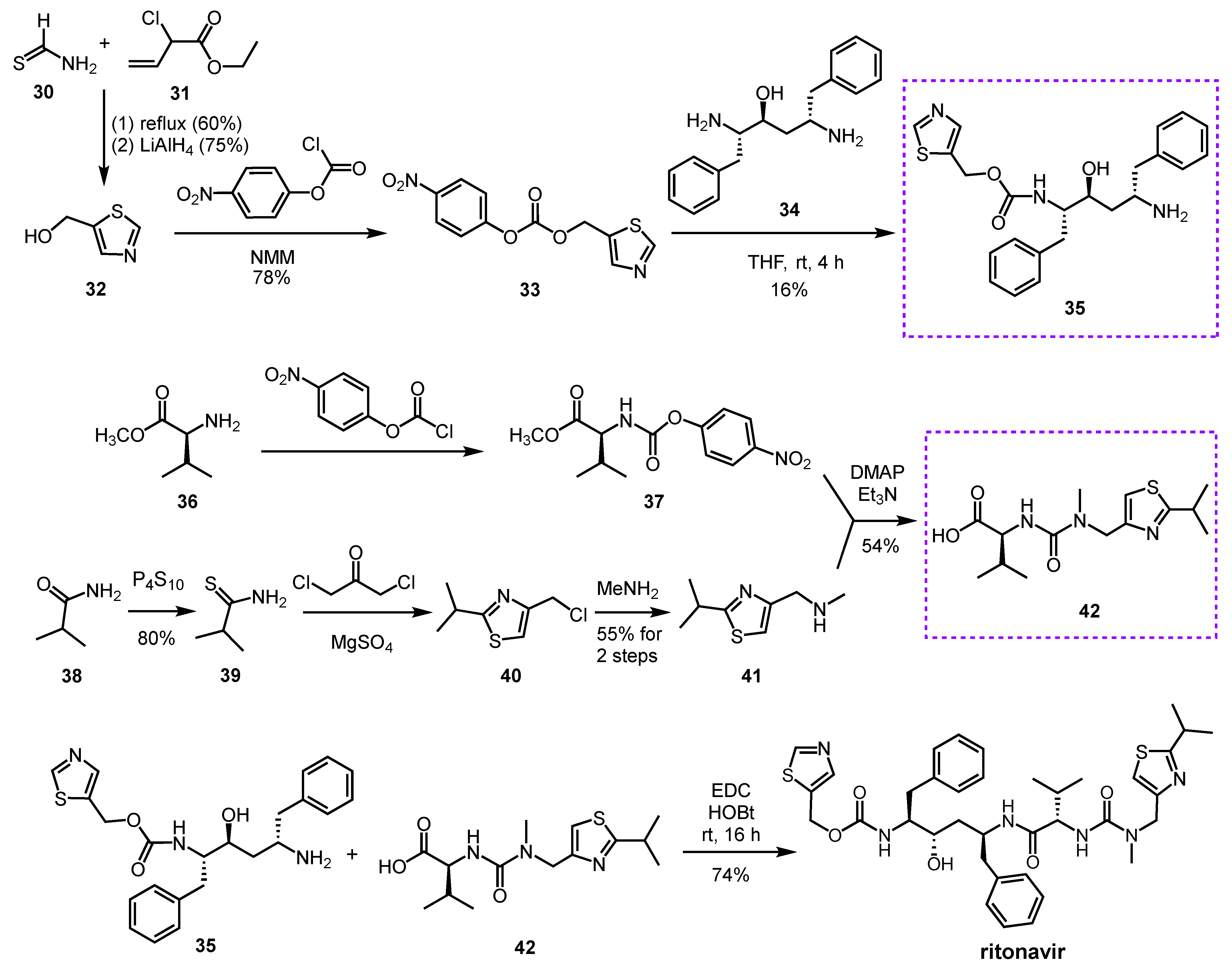

3.2. Synthesis of Ritonavir

4. Paxlovid—Application and Activity against Mutant Variants

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, S.P. Fundamentals of Viruses and Their Proteases. In Viral Proteases and Their Inhibitors; Gupta, S.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-12-809712-0. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, B.; Mayer, J.M. Hydrolysis in Drug and Prodrug Metabolism Chemistry Biochemistry and Enzymology; Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta and WILEY-VCH GmbH et Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; ISBN 3-906390-25-X. [Google Scholar]

- Majerová, T.; Konvalinka, J. Viral proteases as therapeutic targets. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 88, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.R.; Allerton, C.M.N.; Anderson, A.S.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Avery, M.; Berritt, S.; Boras, B.; Cardin, R.D.; Carlo, A.; Coffmann, K.J.; et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science 2021, 374, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengist, H.M.; Dilnessa, T.; Jin, T. Structural Basis of Potential Inhibitors Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 622898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citarella, A.; Dimasi, A.; Moi, D.; Passarella, D.; Scala, A.; Piperno, A.; Micale, N. Recent Advances in SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors: From Nirmatrelvir to Future Perspectives. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Chen, C.; Tang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Z.; et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesko, B.; Deng, A.; Chan, J.D.; Neme, S.; Dhanireddy, S.; Jain, R. Safety, and tolerability of paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) in high risk patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 2049–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, B.; Amani, B. Efficacy and safety of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) for COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltra, S.; Conrad, T. Effectiveness of Paxlovid—A review. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-T.; Yin, J.-Y.; Chen, X.-H.; Liu, M.; Yang, S.-G. Appraisal of evidence reliability and applicability of Paxlovid as treatment for SARS-COV-2 infection: A systematic review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, J.; Cox, D.S.; Singh, R.S.P.; Chan, P.L.S.; Rao, R.; Allen, R.; Shi, H.; Masters, J.C.; Damle, B. A Comprehensive Review of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Drug Interactions of Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2024, 63, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leuw, P.; Stephan, C. Protease inhibitor therapy for hepatitis C virus-infection. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfon, P.; Locarnini, S. Hepatitis C virus resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechter, I.; Berger, A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967, 27, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Chu, Y.; Wang, Y. HIV protease inhibitors: A review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV/AIDS (Auckl.) 2015, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Osswald, H.L.; Prato, G. Recent Progress in the Development of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV/AIDS. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5172–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.L.; Kania, R.S.; Brothers, M.A.; Davies, J.F.; Ferre, R.A.; Gajiwala, K.S.; He, M.; Hogan, R.J.; Kozminski, K.; Li, L.Y.; et al. Discovery of ketone-based covalent inhibitors of coronavirus 3CL proteases for the potential therapeutic treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12725–12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Hui, D.; Wu, A.; Chan, P.; Cameron, P.; Joynt, G.M.; Ahuja, A.; Yung, M.Y.; Leung, C.B.; To, K.F.; et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1986–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.C. Approaches to the Potential Therapy of COVID-19: A General Overview from the Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. Molecules 2022, 27, 658–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, C.S.B. Novel Nitrile Peptidomimetics for Treating COVID-19. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, R.P.; Hu, V.W.; Wang, J. The history, mechanism, and perspectives of nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332): An orally bioavailable main protease inhibitor used in combination with ritonavir to reduce COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, F.; Zheng, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Fan, X.; McCormick, P.J.; et al. Structural Basis of the Main Proteases of Coronavirus Bound to Drug Candidate PF-07321332. Virol. J. 2022, 96, e0201321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, S.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Tung, N.T.; Mai, B.K. Insights into the binding and covalent inhibition mechanism of PF-07321332 to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3729–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzi, M.; Vakil, M.K.; Bahmanyar, M.; Zarenezhad, E. Paxlovid: Mechanism of Action, Synthesis, and In Silico Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 7341493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallam, S.R.; Eda, V.R.; Sen, S.; Datrika, R.; Rapolu, R.K.; Khobare, S.; Gajare, V.; Banda, M.; Khan, R.A.R.; Singh, M.; et al. A diastereoselective synthesis of boceprevir’s gem-dimethyl bicyclic [3.1.0] proline intermediate from an insecticide ingredient cis-cypermethric acid. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 4285–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhao, J.; et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with protease inhibitor PF-07321332. Protein Cell 2022, 13, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preschel, H.D.; Otte, R.T.; Zhuo, Y.; Ruscoe, R.E.; Burke, A.J.; Kellerhals, R.; Horst, B.; Hennig, S.; Janssen, E.; Green, A.P.; et al. Multicomponent Synthesis of the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitor Nirmatrelvir. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 12565–12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, V.; Bailey, K.R.; Znabet, A.; Raftery, J.; Helliwell, M.; Turner, N.J. Enantioselective Biocatalytic Oxidative Desymmetrization of Substituted Pyrrolidines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2182–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Reyes, J.C.; Islas-Jácome, A.; González-Zamora, E. The Ugi three-component reaction and its variants. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 5460–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liang, J.; Ambrogelly, A.; Brennan, T.; Gloor, G.; Huisman, G.; Lalonde, J.; Lekhal, A.; Mijts, B.; Muley, S.; et al. Efficient, Chemo-enzymatic Process for Manufacture of the Boceprevir Bicyclic [3.1.0] Proline Intermediate Based on Amine Oxidase-Catalyzed Desymmetrization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6467–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankadara, S.; Dawson, M.D.; Fong, J.Y.; Oh, Q.Y.; Ang, Q.A.; Liu, B.; Chang, H.Y.; Koh, J.; Koh, X.; Tan, Q.W.; et al. A Warhead Substitution Study on the Coronavirus Main Protease Inhibitor Nirmatrelvir. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citarella, A.; Moi, D.; Pedrini, M.; Pérez-Peña, H.; Pieraccini, S.; Dimasi, A.; Stagno, C.; Micale, N.; Schirmeister, T.; Sibille, G.; et al. Synthesis of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors bearing a cinnamic ester warhead with in vitro activity against human coronaviruses. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3811–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf-Uz-Zaman, M.; Chua, T.K.; Li, X.; Yao, Y.; Moku, B.K.; Mishra, C.B.; Avadhanula, V.; Piedra, P.A.; Song, Y. Design, Synthesis, X-ray Crystallography, and Biological Activities of Covalent, Non-Peptidic Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, S.; Convertino, I.; Cappello, E.; Valdiserra, G.; Bonasoa, M.; Tuccori, M. Lessons learnt from the preclinical discovery and development of ensitrelvir as a COVID-19 therapeutic option. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2024, 19, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.L.; van Heeswijk, R.P.G.; Gallicano, K.; Cameron, D.W. A Review of Low-Dose Ritonavir in Protease Inhibitor Combination Therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetkovic, R.S.; Goa, K.L. Lopinavir/Ritonavir A Review of its Use in the Management of HIV Infection. Drugs 2003, 63, 769–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Zanger, U.M. Pharmacogenomics of cytochrome P450 3A4: Recent progress toward the “missing heritability” problem. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.K.; Patel, P.B.; Barvaliya, M.; Saurabh, M.K.; Bhalla, H.L.; Khosla, P.P. Efficacy and safety of lopinavir-ritonavir in COVID-19: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzolini, C.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Marra, F.; Boyle, A.; Gibbons, S.; Flexner, C.; Pozniak, A.; Boffito, M.; Waters, L.; Burger, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Management of Drug-Drug Interactions Between the COVID-19 Antiviral Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (Paxlovid) and Comedications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, N.H.C.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. The Mechanism-Based Inactivation of CYP3A4 by Ritonavir: What Mechanism? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9866–9890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, B.M.; Hengel, S.M.; Rock, D.A.; Wienkers, L.C.; Kunze, K.L. Characterization of ritonavir-mediated inactivation of cytochrome P450 3A4. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 86, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, D.J.; Sham, H.L.; Marsh, K.C.; Flentge, C.A.; Betebenner, D.; Green, B.E.; McDonald, E.; Vasavanonda, S.; Saldivar, A.; Wideburg, N.E.; et al. Discovery of ritonavir, a potent inhibitor of HIV protease with high oral bioavailability and clinical efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Bilcer, G.; Schiltz, G. Syntheses of FDA Approved HIV Protease Inhibitors. Synthesis 2001, 2001, 2203–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempf, D.J.; Marsh, K.C.; Fino, L.C.; Bryant, P.; Craig-Kennard, A.; Sham, H.L.; Zhao, C.; Vasavanonda, S.; Kohlbrenner, W.E.; Wideburg, N.E.; et al. Design of Orally Bioavailable, Symmetry-Based Inhibitors of HIV Protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1994, 2, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; McKee, S.P.; Thompson, W.J.; Darke, P.L.; Zugay, J.C. Potent HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors: Stereoselective Synthesis of a Dipeptide Mimic. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Y.N. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.L.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simón-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N. Eng. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Lewandowski, E.M.; Tan, H.; Zhang, X.; Morgan, R.T.; Zhang, X.; Jacobs, L.M.C.; Butler, S.G.; Gongora, M.V.; Choy, J.; et al. Naturally occurring mutations of SARS-CoV-2 main protease confer drug resistance to nirmatrelvir. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mótyán, J.A.; Mohamed Mahdi, M.; Hoffka, G.Y.; Tőzsér, J. Potential Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) against Protease Inhibitors: Lessons Learned from HIV-1 Protease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, J.D.; Chu, A.W.; Chan, W.; Leung, R.C.; Abdullah, S.M.U.; Sun, Y.; To, K.K. Global prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease mutations associated with nirmatrelvir or ensitrelvir resistance. eBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacharya, M.; Dhama, K.; Lee, S.; Chakraborty, C. Resistance to nirmatrelvir due to mutations in the Mpro in the subvariants of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron: Another concern? Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 13, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epling, B.P.; Rocco, J.M.; Boswell, K.L.; Laidlaw, E.; Galindo, F.; Kellogg, A.; Das, S.; Roder, A.; Ghedin, E.; Kreitman, A.; et al. COVID-19 redux: Clinical, virologic, and immunologic evaluation of clinical rebound after nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, G.; Focosi, D.; Turriziani, O.; Tuccori, M.; Brandi, R.; Fillo, S.; Ajassa, C.; Lista, F.; Mastroianni, C.M. Virological and clinical rebounds of COVID-19 soon after nirmatrelvir/ritonavir discontinuation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1657–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; McConnell, S.; Shoham, S.; Casadevall, A.; Maggi, F.; Antonelli, G. Nirmatrelvir and COVID-19: Development, pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy, resistance, relapse, and pharmacoeconomics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 61, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Quaglio, D.; Calcaterra, A.; Ghirga, F.; Sorrentino, L.; Cammarone, S.; Fracella, M.; D’Auria, A.; Frasca, F.; Criscuolo, E.; et al. Natural Flavonoid Derivatives Have Pan-Coronavirus Antiviral Activity. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, A.; Tang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Qu, J.; Lei, W.; Liu, W.J.; et al. A pan-coronavirus peptide inhibitor prevents SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice by intranasal delivery. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Q.; Wang, L.; Jiao, F.; Lu, L.; Xia, S.; Jiang, S. Pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitors to combat COVID-19 and other emerging coronavirus infectious diseases. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bege, M.; Borbás, A. The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16020217

Bege M, Borbás A. The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19. Pharmaceutics. 2024; 16(2):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16020217

Chicago/Turabian StyleBege, Miklós, and Anikó Borbás. 2024. "The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19" Pharmaceutics 16, no. 2: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16020217

APA StyleBege, M., & Borbás, A. (2024). The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19. Pharmaceutics, 16(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16020217