Abstract

Dopamine (DA), its derivatives, and dopaminergic drugs are compounds widely used in the management of diseases related to the nervous system. However, DA receptors have been identified in nonneuronal tissues, which has been related to their therapeutic potential in pathologies such as sepsis or septic shock, blood pressure, renal failure, diabetes, and obesity, among others. In addition, DA and dopaminergic drugs have shown anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in different kinds of cells. Aim: To compile the mechanism of action of DA and the main dopaminergic drugs and show the findings that support the therapeutic potential of these molecules for the treatment of neurological and non-neurological diseases considering their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. Method: We performed a review article. An exhaustive search for information was carried out in specialized databases such as PubMed, PubChem, ProQuest, EBSCO, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science, Bookshelf, DrugBank, Livertox, and Clinical Trials. Results: We showed that DA and dopaminergic drugs have emerged for the management of neuronal and nonneuronal diseases with important therapeutic potential as anti-inflammatories and antioxidants. Conclusions: DA and DA derivatives can be an attractive treatment strategy and a promising approach to slowing the progression of disorders through repositioning.

1. Introduction

Dopamine (DA) is a monoamine synthesized mainly in neurons of the midbrain cores, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra pars compacta. The synthesis of the neurotransmitter takes place in the dopaminergic nerves [1]. Hydroxylation of the amino acid L-tyrosine is the point of regulation of the synthesis of catecholamines, including DA, in the central nervous system (CNS), and consequently, the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) enzyme is the limiting enzyme of the synthesis of DA, norepinephrine, and adrenaline. Through their receptors, DA has been shown to have physiological functions in the CNS, such as wakefulness, attention, memory formation and consolidation, novelty-induced memory encoding, and reward/addiction [2,3,4,5]. DA is a neuromodulator that has the ability to diffuse away from the site of its release, activating receptors that are far from the terminal; this ability is called transmission volume [2]. In this sense, DA receptors have been identified in nonneuronal tissues, which has been related to their therapeutic potential in pathologies such as sepsis or septic shock, blood pressure, renal failure, diabetes, and obesity, among others [6,7,8]. In addition, it has been reported that DA and dopaminergic drugs such as bromocriptine, cabergoline, pramipexole, and ropinirole have shown anti-inflammatory and antioxidant functions in different kinds of cells, reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, preserving glutathione (GSH) and other antioxidant enzymes, and decreasing lipid peroxidation [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Additionally, some herbal compounds have shown dopaminergic properties; for example, Hepad S1, a Korean medicinal herbal combination, is an important source of dopamine with neuroprotective properties that improve Parkinson’s symptoms; it could modulate adverse cellular events such as inflammation and oxidation in neuronal cells [15]. Curcumine has shown neuroprotective properties and is an important component of dopamine [16], and Hordenine, a natural compound of germinated barley, is an agonist of the dopamine D2 receptor [17]. These and other herbs have been mainly studied in neuronal diseases, with less research in nonneuronal diseases. Then, the scope of this review is to compile the mechanism of action of DA and the main dopaminergic drugs and show the findings that support the therapeutic potential of these molecules for the treatment of neurological and non-neurological diseases considering their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and their efficacy in clinical assays.

2. Methodology

Advanced searches were performed in PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCO, Scopus, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Web of Science, PubChem, NCBI Bookshelf, DrugBank, livertox, and Clinical Trials. We considered the original manuscripts, reviews, minireviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical assays, books, and specialized databases. The search was performed by applying the following keywords alone or in combination: “dopamine”, “dopaminergic drug”, “metabolism”, “chemical compounds”, chemical structure”, “D1, D2 receptors”, “precursors”, “experimental agonists and antagonists”, “receptor blockers”, “antioxidant”, “anti-inflammatory”, “neuronal pathologies” “nonneuronal pathologies”, “physiological functions”, “drug repositioning”, “neuromodulator”, “free radicals”, “reactive oxygen species”, “oxidative stresses”, “antioxidant enzymes”, “efficacy”, and “secondary effects”. A total of 200 references were included.

3. Dopamine Synthesis, Release, Catabolism, and Postsynaptic Action

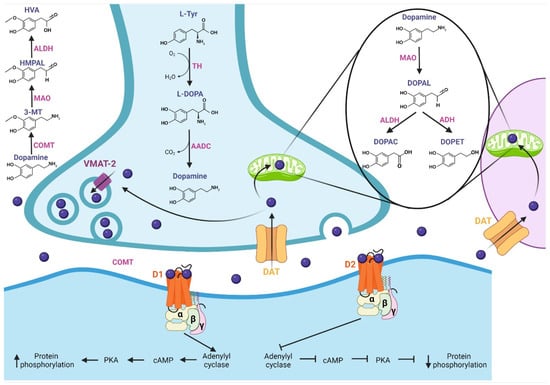

In this section, we describe DA and its pharmacological properties at the molecular level. The synthesis of DA (Figure 1) begins with the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine by the TH enzyme to generate L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA); then, aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC or DOPA decarboxylase) allows the production of cytosolic dopamine [18,19,20]. The DA synthesized in the presynaptic terminal is loaded in synaptic vesicles by vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2); subsequently, DA is released to the synaptic cleft. Next, the Na+-dependent dopamine transporter (DAT), localized in neurons and glial cells, reuptakes the neurotransmitter [18]. DA is recycled into synaptic vesicles or degraded by specialized enzymes [21], where its catabolism takes place. In presynaptic terminal and glial cells, the monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme, localized in mitochondria, breaks down DA through oxidative deamination, producing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL); in turn, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) converts DOPAL to carboxylic acid 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) by oxidation, or alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) reduces DOPAL to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DOPET) [20,22]. The catechol O-methyl-transferase (COMT) enzyme, localized in the synaptic cleft, catalyzes the methylation of dopamine to 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT), which is a MAO substrate that forms 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (HMPAL). Finally, the ALDH enzyme catalyzes HMPAL to generate homovanillic acid (HVA), which is the main end-product of DA degradation [20,22,23]. At the post-synapse, DA binds to D1-like and D2-like receptors, which are G-protein-coupled channels [24]. The D1-like receptor activates the Gαs/olf subunit protein that stimulates the adenylyl cyclase (AC) protein; then, it generates the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) second messenger, which activates protein kinase A (PKA), resulting in target action and increasing protein phosphorylation. On the other hand, the D2-like receptor, by activating the Gαi/o subunit, inhibits the effector protein AC, inhibiting the cAMP second messenger and, thereby, PKA, generating a decrease in protein phosphorylation [18,24,25,26].

Figure 1.

Synthesis, release, catabolism, and postsynaptic action of dopamine. Synthesis: The TH enzyme converts L-tyrosine to L-DOPA; then, the AADC enzyme allows the production of dopamine, which is loaded into synaptic vesicles by VMAT-2. Release and recycling: once released in the synaptic cleft, the DAT transporter reuptakes dopamine, which is recycled into synaptic vesicles. Catabolism: Dopamine is degraded by specialized enzymes; the MAO enzyme breaks down dopamine to DOPAC and DOPET. In the synaptic cleft, the COMT enzyme catalyzes dopamine to HVA, which is the main end-product of dopamine degradation. At the post-synapse, dopamine binds with D1-like and D2-like receptors. The D1-like receptor activates the Gαs/olf subunit, which stimulates adenylyl cyclase protein, increasing protein phosphorylation. D2-like receptor, by activating the Gαi/o subunit, inhibits the protein adenylyl cyclase, generating a decrease in protein phosphorylation. TH: tyrosine hydroxylase, L-DOPA: L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, AADC: L-amino acid decarboxylase, VMAT-2: vesicular monoamine transporter 2, DAT: dopamine transporter, MAO: monoamine oxidase, DOPAL: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, ALDH: aldehyde dehydrogenase, DOPAC: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase, DOPET: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, COMT: catechol O-methyl-transferase, HMPAL: 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, HVA: homovanillic acid.

4. Chemical Compounds and Drugs Related to the Dopaminergic System

There are more than 200 chemical compounds and drugs related to the dopaminergic system [27,28,29], and mentioning each of them is beyond the scope of this work; however, they can be grouped, according to their activity, as precursors [30,31,32,33], agonists and antagonists of receptors [34], DA reuptake inhibitors [35,36] DA releasing agents [36,37], activity enhancers [38,39,40], and enzyme inhibitors [41], among others. Three DA precursors are used in the clinic, L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine, and L-DOPA; tyrosine is a nonessential amino acid that is synthesized from the essential aromatic amino acid phenylalanine, and both amino acids constitute the two initial steps in the biosynthesis of DA [31]. Levodopa (L-DOPA) is a dopamine precursor and is the most effective and commonly used drug for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Levodopa is prescribed in most cases with Carbidopa, which is an inhibitor of L-amino acid decarboxylase, the enzyme that metabolizes levodopa peripherally [42].

DA agonists exert their effects by acting directly on dopamine receptors and mimicking endogenous neurotransmitters. There are two subclasses, ergoline, and nonergoline agonists, with a variable affinity for different DA receptors [43,44]. DA antagonists block the effects of dopamine or its agonists by binding to DA receptors. A variety of DA antagonists are used for the treatment of psychotic disorders; however, their therapeutic effects are mostly due to long-term adjustments rather than acute blockade of DA receptors [29]. Some DA antagonists have been used to treat Tourette’s syndrome or hiccups [45,46], and they have also been used as antiemetics to treat various causes of nausea and vomiting [47]. Table 1 details the mechanisms of action and indications of DA precursors and the most representative dopaminergic agonist and antagonist drugs.

Table 1.

Mechanism of action and indications of dopamine precursors and dopaminergic agonist and antagonist drugs.

On the other hand, DA reuptake inhibitors may be classified as DAT inhibitors and VMAT inhibitors. The former block the action of DAT, and DA reuptake inhibition occurs when extracellular DA, which does not bind to the postsynaptic neuron, is blocked from re-entering the presynaptic neuron, resulting in increased extracellular concentrations of DA and an increase in dopaminergic neurotransmission [80]. DAT inhibitors are indicated for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, and seasonal affective disorder and as an aid to smoking cessation; examples are methylphenidate [27,29]. On the other hand, VMAT inhibitors prevent the reuptake and storage of monoamine neurotransmitters in synaptic vesicles, making them vulnerable to metabolism by cytosolic enzymes. Inhibition of VMAT-2 results in decreased reuptake of monoamines and depletion of their reserves in nerve terminals. They are used to treat chorea due to neurodegenerative diseases or dyskinesias due to neuroleptic medications; examples are tetrabenazine, deutetrabenazine, and valbenazine [27,42,81,82,83].

DA-releasing agents are a type of drug that induces, through various mechanisms, the release of DA from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft, leading to an increase in extracellular concentrations of the neurotransmitter. Examples are amphetamine, lisdexamfetamine (L-lysine-d-amphetamine; vyvanse), methamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and 4-methylaminorex [27,84,85,86,87]. Moreover, (-)1-(benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, (-)BPAP, (-)-1-phenyl-2-propylaminopentane, and (-)PPAP are enhancers of dopamine activity. BPAP and PPAP act as potent stimulants of neurotransmitter release in dopaminergic neurons, leaving MAO activity largely unchanged. BPAP and PPAP controllably increase the quantity of neurotransmitters that are released when a neuron is stimulated by a neighboring neuron, and they are currently in the research phase [39,88,89].

DA enzyme inhibitors can be classified into DA synthesis inhibitors and DA degradation inhibitors. There are three kinds of dopamine synthesis inhibitors: (1) TH inhibitors (for example, 3-iodo-tyrosine and metyrosine), which are able to inhibit TH activity, the rate-limiting enzyme in DA biosynthesis [90]; (2) phenylalanine hydroxylase inhibitors (for example, 3,4-dihydroxystyrene), which inhibit the enzyme that converts phenylalanine to tyrosine [91]; and (3) DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors, which block the biosynthesis of L-DOPA to DA. Examples of these inhibitors are benserazide and carbidopa, commonly used in combination with levodopa. Since they can hardly cross the blood–brain barrier, they prevent the formation of dopamine in extracerebral tissues, minimizing the occurrence of extracerebral side effects [92,93].

Finally, the main DA degradation inhibitors can be classified into MAO and COMT inhibitors. The most prescribed MAO inhibitors are selegiline, isocarboxazid, phenelzine, and tranylcypromine. They have in common the ability to block oxidative deamination of DA and subsequently provoke its elevation in brain levels, enhancing dopaminergic activity [29,94]. Selegiline is close structurally to (-) methamphetamine and is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B). Selegiline is the first catecholaminergic activity-enhancing substance in clinical use that does not continually release catecholamines and is, therefore, free of amphetamine dependence [38,40]. Likewise, the most common COMT inhibitors are entacapone, opicapone, and tolcapone. They inhibit the COMT enzyme and are frequently used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease as an adjunct to levodopa/carbidopa medication [95,96,97]. Many Parkinson’s disease patients treated with levodopa plus carbidopa experience motor complications over time; when COMT inhibitors are administered, plasma levodopa levels are increased and maintained, resulting in more consistent dopaminergic stimulation, leading to further reduction of the manifestations of parkinsonian syndrome [98].

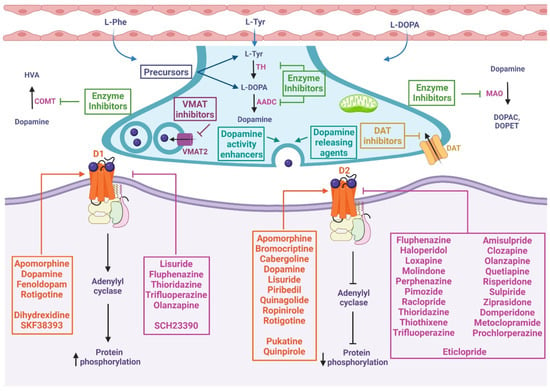

In summary, dopaminergic compounds and drugs act through a variety of mechanisms of action within the process of synthesis, release, catabolism, and postsynaptic action of dopamine, as shown in Figure 2. It should be noted that these main mechanisms are often accompanied by secondary mechanisms (such as antioxidant or anti-inflammatory mechanisms, see below, which are not yet fully understood) that give a wide variety of effects and indications as potential adjuvants in most chronic and degenerative diseases.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of chemical compounds and drugs related to the dopaminergic system. These drugs can inhibit or activate diverse proteins involved in dopamine metabolism, including precursors, enzyme inhibitors, dopamine-releasing agents, dopamine reuptake inhibitors, dopamine activity enhancers, and agonists or antagonists of D1-like and D2-like receptors. At presynapses: The precursors enable the biosynthesis of dopamine. VMAT inhibitors prevent the storage of monoamines in synaptic vesicles, resulting in the depletion of these neurotransmitters. DAT inhibitors keep dopamine in the synaptic cleft longer by inhibiting its reuptake. Dopamine-releasing agents and dopamine activity enhancers increase the release of the activity of dopamine into the synaptic cleft. Dopamine synthesis inhibitors prevent the formation of dopamine as an endpoint. Dopamine degradation inhibitors enhance dopaminergic activity by blocking dopamine catabolism. At postsynapses: The dopamine agonist (orange box) mimics endogenous dopamine function, thus activating or inhibiting adenylyl cyclase depending on whether it binds to D1-like or D2-like receptors, respectively. Dopamine antagonists (pink box) bind to but do not activate dopamine receptors, thereby blocking the actions of dopamine. L-Phe: L-phenylalanine, L-Tyr: L-tyrosine, TH: tyrosine hydroxylase, L-DOPA: L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, AADC: L-amino acid decarboxylase, VMAT2: vesicular monoamine transporter 2, DAT: dopamine transporter, MAO: monoamine oxidase, DOPAC: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, DOPET: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, COMT: catechol O-methyl-transferase, HVA: homovanillic acid, D1: dopamine 1 receptor, D2: dopamine 2 receptor.

5. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Dopamine and Related Drugs

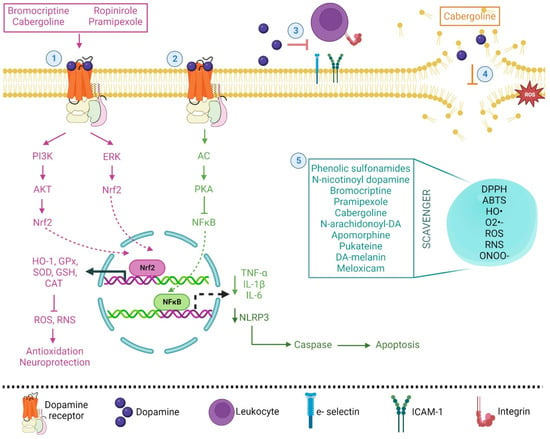

In 1997, it was reported for the first time that DA has a direct antioxidant effect due to the number of hydroxy groups on the phenolic ring of the molecule. In this sense, Yen and Hsieh [99] showed that DA has a protective effect against the oxidation of linoleic acid, has reducing power, and shows scavenger capacity against 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) radicals, superoxide radicals (O2•−) and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) (94.94, 53 and 65.7%, respectively), showing the strongest capacity. The authors conclude that the 1,2 position hydroxy group on the phenolic ring and the side chain is an electron-donating amine group [99]. Later, it was shown that DA and D4 receptors induced nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) activity during ischemia in vivo in astrocyte and meningeal cell cultures, showing its capacity to modulate the antioxidant effect; Nrf2 is a transcription factor that controls inducible expression of multiple antioxidant/detoxification genes [100,101] and induces the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) by human endothelial cells in vitro [102]. The anti-inflammatory effect of DA has also been demonstrated in alcoholic hemorrhagic pancreatitis in cats [103]. In fact, DA has been proposed as an immune transmitter, given that dopaminergic signaling is involved in neurological diseases and is associated with the inflammatory response [104]. DA inhibits cytokine production via D1 receptors, decreases oxidative stress [105], and can cause nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), a transcription factor that mediates the control of ROS and inhibition in acute kidney injury [106]. Catecholamines, including DA, can inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and may enhance interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) production through D2, D3, or D1/D5 receptors [107,108,109]. In fact, DA has been proposed to be a putative anti-inflammatory cytokine by itself attenuating the chemoattractant effect of interleukin-8 (IL-8), integrins CD11b and CD18, and the adhesion molecules E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) [110]. DA and its D1 receptor also inhibit the activation of the protein complex named NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in bone marrow-derived macrophages [111,112]. On the other hand, it has been shown that catechol moieties protect cells against oxidative damage and downregulate the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukine-1beta (IL-1β) in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [113]. Catecholamines identified in two medicinal plants (Santolina chamaecyparissus and Launaea mucronate) have also shown antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in carrageenan-induced paw edema in a rat model [114]. DA also inhibited the peroxidation of brain phospholipids and reaction with radicals such as trichloromethyl peroxyl radicals (CCl3O2•), O2•−, peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hydrochlorous acid (HOCl) generated in vitro [115,116,117]. Moreover, the antioxidant effect of DA derivatives of several plant species, such as soybean, avocado, apple, cucumber, and banana, has also been reported, showing an increase in antioxidant enzyme activities (superoxide dismutase, SOD; catalase, CAT; glutathione reductase, GR) and reactive oxygen species (hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, nitric oxide, NO•, and O2•−) scavenging capacity [118,119,120,121,122,123]. In another work, it was shown that other derivatives of DA-related compounds or DA agonists showed antioxidant activity. It has been shown that phenolic sulfonamides showed scavenger capacity in vitro against DPPH, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS), and O2•− [124]. N-Nicotinoyl dopamine also showed antioxidant properties with DPPH scavenging activity and protected against ROS accumulation induced by UVB irradiation in HaCat cells [125]. Bromocriptine, a DA agonist, scavenged O2•−, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide hydroxide, and DPPH radicals generated through in vitro systems [9]. This compound also activates NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) via Nrf2-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling in H2O2-treated PC12 cells, protecting against oxidative damage [126]. In in vivo experimental work, it was shown that a non-ergot DA agonist named ropinirole showed a neuroprotective effect, increased GSH, CAT, and SOD antioxidant activities in the striatum, protected striatal dopaminergic neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) in mice [14] and was an activator of the GHS system in the mouse striatum [127]. Pramipexole, a DA agonist, protects the DAergic cell line MES 23.5 against 6-OHDA and H2O2, increasing cellular levels of GSH, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and CAT activities [11,12] and scavenging HO• induced by 6-OHDA in rats [13]. In an in vivo model using [3H] pramipexole, it has been shown that the drug enters and accumulates in cells and mitochondria. Pramipexole also prolongs survival time in SOD-1-G93A mice, a model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [128]. Cabergoline, an ergot derivative DA agonist, has the ability to activate GSH, CAT, and SOD against the neurotoxicity of 6-OHDA in mice, reducing lipid peroxidation [10] and showing antioxidant activity against oxidation in phosphatidylcholine liposomes [129]. D-390, a novel D2/D3 receptor agonist, also showed potent iron chelation [130], and a new tris (DA) derivative also showed Fe(III), Mg(II), Zn(II), and Fe(II) chelation and antioxidant activity in neuron-like rat pheochromocytoma cells [131]. Other DA derivatives, such as N-arachidonoyl-DA and apomorphine, and DA-related compounds, such as pukateine [(R)-11-hydroxy-1,2-methylenedioxyaporphine], have also shown antioxidant properties [60,132,133,134]. It has been shown that caffeic acid anilides and caffeic acid dopamine amide showed DPPH scavenging capacity and microsomal lipid peroxidation-inhibiting activity [135]. Recently, the water-soluble caffeic acid-DA hydrochloride complex has been proposed as a bactericidal, antibiofilm, and antitumoral agent in the physiological pH range (5.5–7.5) due to its antioxidant properties [136].

Recent clinical research findings indicate that melatonin may modulate dopaminergic pathways involved in movement disorders in humans. It has been proposed that the interaction of melatonin with the dopaminergic system may play a significant role in the nonphotic and photic entrainment of the biological clock as well as in the fine-tuning of motor coordination in the striatum principally because these interactions, by its antioxidant nature can be beneficial in humans [137,138,139]. Additionally, its anti-inflammatory properties have been proposed for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis [140,141]. In relation to pathologies not related to the central nervous system, the use of DA-melanin nanoparticles has been proposed as a novel scavenger of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). These nanoparticles showed low cytotoxicity and a strong ability to scavenge ROS and RNS: O2•−, HO• radicals, and ONOO− were proposed as potent anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective agents due to their average diameter of 112.5 nm. Nanoparticles can be intra-articularly injected into an affected joint and retained at the injection site, as was shown in an osteoarthritis rodent model and in chondrocyte cultures. These nanoparticles also diminished IL-1β and reduced proteoglycan loss, probably stimulating autophagy for chondrocyte protection. IL-1β caused an increase in the gene expression of autophagy markers: protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3-11), autophagy-related 7 (ATG7), and beclin-1 [142]. The use of N-acyl dopamine derivates has also been proposed as a potential alternative for implementation in transplantation medicine due to its immunomodulatory, cytoprotective, and anti-inflammatory properties [143]. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of DA and some related drugs are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simplified and integrated mechanisms of dopamine and its agonist, as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory molecules, in various physiological processes. (1) The binding of dopamine and some agonist drugs with its receptor activates the PI3K/AKT or ERK signaling pathway, resulting in Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus, inducing the expression of HO-1 and antioxidant genes (pink pathway). (2) The activation of AC/PKA inhibits NF-κB, generating a decrease in proinflammatory cytokine expression and the protein complex NLRP3 inflammasome, thus diminishing the apoptotic process (green pathway). (3) Dopamine attenuates the chemoattractant effect of integrins and adhesion molecules. (4) Cabergoline and dopamine inhibited the peroxidation of brain phospholipids and reacted with free radicals. (5) Some drugs showed scavenger capacity and protection against ROS accumulation (cyan box).

Finally, it is important to mention that in cancer, DA agonists inhibit T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity, probably through activation of the D1 receptor, which promotes an increase in intracellular cAMP, contributing to immune regulation [144]. Additionally, these agonists have an important role due to their beneficial antiangiogenic effects. Hoeppner et al., 2015 [145] showed that D2 receptor agonists inhibit NADPH oxidase activity, reducing the production of ROS involved in angiogenesis [145]. Leng et al., 2017 [146] found in GH3 cells that D5 receptor agonists could inhibit the activity and expression of SOD-1 and increase ROS, promoting autophagy and cell death by inhibiting the AKT-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [146].

6. Clinical Trials in Nonneuronal Pathologies

DA, agonists, or derivatives are being tested as possible drugs or adjuvants in other non-CNS pathologies, possibly due to their antioxidant or anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory properties. In this sense, DA, serotonin, prostaglandin E2, substance P, and lipoperoxidation levels are decreased, whereas SOD levels are increased after pain treatment with warm acupuncture and meloxicam in patients with knee osteoarthritis, showing the involvement of these biochemical markers as anti-inflammatory mediators [147]. DA treatment (15 μg/kg/min) is also effective in increasing blood pressure in neonates with hypothermia treatment for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [148], and the use of the DA synthetic analog dopexamine in doses of 0.5 and 2.0 μg/kg/min significantly protected the upper gastrointestinal mucosa in the of patients with abdominal surgery, reducing the incidence of acute inflammation and decreasing myeloperoxidase activity and inducible nitric oxide synthase in biopsies [149]. The effects of DA (2.5 to 10 μg/kg/min) have also been observed in patients with sepsis, where its administration was associated with a fall in lactate and no effect on arterial pH [150]. DA (10 to 25 µg/kg/min) is effective in the treatment of patients with hyperdynamic septic shock, where it successfully improved the systemic vascular resistance index, cardiac index, oxygen delivery and uptake [151]. It has been shown that DA (infused at 2 and 4 µg/kg/min) increases renal oxygenation with no increase in tubular sodium reabsorption or renal oxygen consumption in glomerular filtration rate in postcardiac surgery patients [152]. Bromocriptine has also been proposed as an adjuvant in immunosuppression after renal transplantation, but its effectiveness has not yet been widely shown [153,154]. Additionally, bromocriptine (2.5 mg twice daily) prevented ulcer relapse for six months in patients with duodenal ulcers [155]. The use of pramipexole (from 0.25 to 0.75 mg) has shown efficacy in the treatment of restless legs syndrome in patients [156,157]. The use of cabergoline (0.5 mg for eight days) and bromocriptine (2.5 mg for 16 days) are efficient in the prevention of moderate and early-onset ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in patients [158]. The role of DA in crucial social role decision-making was shown using pramipexole in women, allowing them to become less generous in general, modulate smoking behavior or produce subjective effects of cocaine, improve sleep behavior disorder and tinnitus, and help against pain, fatigue, function, and global status in patients with fibromyalgia [159,160,161,162,163,164,165]. Finally, Table 2 summarizes diverse clinical trials in progress.

Table 2.

Clinical trials where the effects of DA and DA agonists or derivatives are being studied in non-CNS diseases as possible drugs or adjuvants.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This is an important work in which the applications of DA and its derivatives are reviewed, offering physicians and healthcare personnel information that may be valuable to make therapeutic decisions considering the advances in the field of knowledge of the use of drugs (of natural or synthetic origin) and/or their action targets. In the present work, we showed that DA and dopaminergic drugs have emerged for the management of diseases, mainly at the neuronal level; however, they have been proposed for the treatment of pathologies that are not directly related to the nervous system, possibly due to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Cabergoline, fenoldopam, bromocriptine, domperidone, pramipexole, rotigotine, and quinagolide, among others, are being tested for sepsis or septic shock, renal failure, gastric diseases, cancer, brain trauma injury, blood pressure, and fibromyalgia. DA receptor agonists or antagonists can function through classical G protein signaling regulating AKT/NF-κB, rat sarcoma virus (Ras)/PI3K/AKT, cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)/NF-κB or signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) pathways inhibiting or activating nuclear transcription or downstream related factors such as NRLP3 inflammasome expression, mTOR, Nrf2 or a tool-like receptor (TLR). Additionally, they can function through other nonreceptor-dependent pathways as L-type Ca2+ channels. However, DA and related drugs should be further studied to more precisely understand the molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying the large number of therapeutic effects considered in this review. Moreover, because DA receptors have multiple physiological roles in neurological and systemic diseases, more preclinical studies are necessary to elucidate the specific functions of DA receptor subtypes.

On the other hand, considering that many systemic and neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the presence of inflammation, related in turn to oxidative stress, DA and DA derivatives can be an attractive option as a strategy of treatment and a promising approach to slowing the progression of disorders through the repositioning of DA. In this sense, our review is important since we mention the possible mechanisms by which DA and its derivatives act as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds in in-vitro studies, animal models, and clinical trials where their therapeutic application is being tested.

Furthermore, it is necessary to study natural products containing DA. In this review, some products, such as fruits, vegetables, and plants with dopaminergic content, have shown antioxidant or anti-inflammatory properties. In the literature, active metabolites such as stepholidine (in Chinese herb), pukatein (natural aporphine derivative), salsolinol (in bananas), hordenine (a constituent of barley and beer), goitrin (in brassicaceous weeds), bromophenols curcumin or cannabinoids that showed dopaminergic properties due to the interaction with DA receptors modulating its signaling are also being considered as possible therapeutic agents. In relation to products of natural origin, first, experimental studies are necessary to understand the dynamic behavior of DA receptors and their interaction modes with active metabolites to understand the relevant structural and functional characteristics of these receptors for interaction with metabolites that function as agonists, antagonists or blockers. Second, more experimental and clinical studies are needed to establish which products of natural origin can be used for the treatment of non-neurological diseases related to DA metabolism.

Due to the above, one of the limitations of this work is the lack of knowledge in a deeper and more precise way of the signal transduction mechanisms of DA, related drugs, and natural compounds, considering the physiopathology of the different diseases where they have been applied. In addition, understanding these mechanisms could generate new applications for DA and its derivatives in other diseases and even be considered adjuvants for combined therapies for different types of neuronal and nonneuronal pathologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., N.C.-R. and E.L.-P.; methodology, C.B. and N.C.-R.; formal analysis, E.L.-P.; investigation, T.R.C.-H., J.G.M.-T. and J.C.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.C.-H., J.G.M.-T., I.J.C.-G., I.I.-M., V.M.-L., A.A.-R. and M.A.V.-H.; writing—review and editing, C.B., N.C.-R. and E.L.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Research System (SNI) from CONACYT in México. C.B., N.C.R., J.G.M.T. and I.J.C.G. are members of SNI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

Dopamine (DA); Central Nervous System (CNS); Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH); reactive oxygen species (ROS); glutathione (GSH); L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA); L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC or DOPA decarboxylase); vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT); Na+-dependent dopamine transporter (DAT); monoamine oxidase (MAO); 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL); aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH); 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC); alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH); 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DOPET); catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT); 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT); 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (HMPAL); homovanillic acid (HVA); adenylyl cyclase (AC); cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP); protein kinase A (PKA); methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA); 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH); superoxide radicals (O2•-); hydroxyl radicals (HO•); nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2 Nrf2; heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1); nuclear factor kappa B NF-kB; tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); interleukine-6 (IL-6); interleukine-10 (IL-10); interleukine-8 (IL-8); intercellular adhesion molecule 1 ICAM-1; NOD-, LRR-and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3); interleukine-1beta (IL-1β); trichloromethyl peroxyl radicals (CC13O2•); peroxynitrite (ONOO-); hydrochlorous acid (HOCl); superoxide dismutase (SOD); catalase (CAT); glutathione reductase (GR); hydrogen peroxide (H2O2); nitric oxide (NO•); 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS); NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase1 (NQO1); phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT); 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA); glutathione peroxidase (GPx); reactive nitrogen species (RNS); autophagy related 7 (ATG7); mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR); rat sarcoma virus (Ras); cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB); signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT); Tool-like receptor (TLR).

References

- Poulin, J.F.; Caronia, G.; Hofer, C.; Cui, Q.; Helm, B.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Chan, C.S.; Dombeck, D.A.; Deisseroth, K.; Awatramani, R. Mapping Projections of Molecularly Defined Dopamine Neuron Subtypes Using Intersectional Genetic Approaches. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar-Slamloo, Y.; Fazlali, Z. Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Brain; Overlapping or Dissociate Functions? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eban-Rothschild, A.; Rothschild, G.; Giardino, W.J.; Jones, J.R.; Lecea, L. de VTA Dopaminergic Neurons Regulate Ethologically Relevant Sleep-Wake Behaviors. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, M.; Takeuchi, T. Locus Coeruleus and Dopamine-Dependent Memory Consolidation. Neural Plast. 2017, 2017, 8602690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Witten, I.B. Striatal Circuits for Reward Learning and Decision-Making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Ezrokhi, M.; Cominos, N.; Tsai, T.H.; Stoelzel, C.R.; Trubitsyna, Y.; Cincotta, A.H. Experimental Dopaminergic Neuron Lesion at the Area of the Biological Clock Pacemaker, Suprachiasmatic Nuclei (SCN) Induces Metabolic Syndrome in Rats. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Donato, A.; Buonincontri, V.; Borriello, G.; Martinelli, G.; Mone, P. The Dopamine System: Insights between Kidney and Brain. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2022, 47, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissimov, S.; Joye, S.; Kharrat, A.; Zhu, F.; Ripstein, G.; Baczynski, M.; Choudhury, J.; Jasani, B.; Deshpande, P.; Ye, X.Y.; et al. Dopamine or Norepinephrine for Sepsis-Related Hypotension in Preterm Infants: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Minamiyama, Y.; Naito, Y.; Kondo, M. Antioxidant Properties of Bromocriptine, a Dopamine Agonist. J. Neurochem. 1994, 62, 1034–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, I.; Fujita, N.; Higashi, Y.; Asanuma, M.; Ogawa, N. The Dopamine Agonist Cabergoline Provides Neuroprotection by Activation of the Glutathione System and Scavenging Free Radicals. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 43, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, W.D.; Jankovic, J.; Xie, W.; Appel, S.H. Antioxidant Property of Pramipexole Independent of Dopamine Receptor Activation in Neuroprotection. J. Neural Transm. 2000, 107, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jr, J.P.B.; Piercey, M.F. Pramipexole—A New Dopamine Agonist for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 163, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ferger, B.; Teismann, P.; Mierau, J. The Dopamine Agonist Pramipexole Scavenges Hydroxyl Free Radicals Induced by Striatal Application of 6-Hydroxydopamine in Rats: An in Vivo Microdialysis Study. Brain Res. 2000, 883, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, M.; Miyazaki, I.; Tanaka, K.; Kabuto, H.; Iwata-Ichikawa, E.; Ogawa, N. Dopamine D2 Receptor-Mediated Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Ropinirole, a Dopamine Agonist. Brain Res. 1999, 838, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Choi, J.J.; Park, B.-J. Herbal Medicine (Hepad) Prevents Dopaminergic Neuronal Death in the Rat MPTP Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Integr. Med. Res. 2019, 8, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, H.; El Kurdi, R.; Patra, D. Curcumin-PLGA Based Nanocapsule for the Fluorescence Spectroscopic Detection of Dopamine. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28245–28253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, T.; Göen, T.; Budnik, N.; Pischetsrieder, M. Absorption, Biokinetics, and Metabolism of the Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonist Hordenine (N,N-Dimethyltyramine) after Beer Consumption in Humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1998–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hall, W.; Lamantia, A.S.; McNamara, J.O.; Williams, S.M. Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors. In Neuroscience; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J.A.; Nijhout, H.F.; Reed, M.C. Homeostatic Mechanisms in Dopamine Synthesis and Release: A Mathematical Model. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2009, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiser, J.; Weindl, D.; Hiller, K. Complexity of Dopamine Metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.M.; Xie, Z.; Stout, K.A.; Zampese, E.; Burbulla, L.F.; Shih, J.C.; Kondapalli, J.; Patriarchi, T.; Tian, L.; Brichta, L.; et al. Dopamine Metabolism by a Monoamine Oxidase Mitochondrial Shuttle Activates the Electron Transport Chain. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Lappin, S.L. Biochemistry, Catecholamine Degradation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545235/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Muñoz, P.; Huenchuguala, S.; Paris, I.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Dopamine Oxidation and Autophagy. Park. Dis. 2012, 2012, 920953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasbi, A.; O’Dowd, B.F.; George, S.R. Dopamine D1-D2 Receptor Heteromer Signaling Pathway in the Brain: Emerging Physiological Relevance. Mol. Brain 2011, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledonne, A.; Mercuri, N.B. Current Concepts on the Physiopathological Relevance of Dopaminergic Receptors. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, K.N.; Mailman, R.B. Dopamine Receptor Signaling and Current and Future Antipsychotic Drugs. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 212, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/#query= (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. STATPEARLS. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430685/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- DRUGBANK Online. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Gandhi, K.R.; Saadabadi, A. Levodopa (L-Dopa). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482140/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Daubner, S.C.; Le, T.; Wang, S. Tyrosine Hydroxylase and Regulation of Dopamine Synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 508, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfaldoni, S.; Tchernev, G.; Lotti, J.; Wollina, U.; Satolli, F.; Rovesti, M.; França, K.; Lotti, T. Unconventional Treatments for Vitiligo: Are They (Un) Satisfactory? Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabsi, A.; Khoudary, A.C.; Abdelwahed, W. The Antidepressant Effect of L-Tyrosine-Loaded Nanoparticles: Behavioral Aspects. Ann. Neurosci. 2016, 23, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Gainetdinov, R.R. The Physiology, Signaling, and Pharmacology of Dopamine Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 182–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.L.; Baladi, M.G.; McFadden, L.M.; Hanson, G.R.; Fleckenstein, A.E. Regulation of the Dopamine and Vesicular Monoamine Transporters: Pharmacological Targets and Implications for Disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Q.D.; Morris, S.E.; Arrant, A.E.; Nagel, J.M.; Parylak, S.; Zhou, G.; Caster, J.M.; Kuhn, C.M. Dopamine Uptake Inhibitors but Not Dopamine Releasers Induce Greater Increases in Motor Behavior and Extracellular Dopamine in Adolescent Rats than in Adult Male Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 335, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, J.A.; Marcy, V.R.; Lin, Y.G.; Bozyczko-Coyne, D.; Marino, M.J.; Gasior, M. The Roles of Dopamine Transport Inhibition and Dopamine Release Facilitation in Wake Enhancement and Rebound Hypersomnolence Induced by Dopaminergic Agents. Sleep 2009, 32, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll, J. (-)Deprenyl (Selegiline), a Catecholaminergic Activity Enhancer (CAE) Substance Acting in the Brain. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998, 82, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsing, L.G.; Knoll, J.; Miklya, I. Enhancer Regulation of Dopaminergic Neurochemical Transmission in the Striatum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll, J. (-) Deprenyl (Selegiline): Past, Present and Future. Neurobiology (Bp. Hung.) 2000, 8, 179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Finberg, J.P.M. Inhibitors of MAO-B and COMT: Their Effects on Brain Dopamine Levels and Uses in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neural. Transm. 2019, 126, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Disease Agents. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Parkinson Disease Agents. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548855/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Reichmann, H.; Bilsing, A.; Ehret, R.; Greulich, W.; Schulz, J.B.; Schwartz, A.; Rascol, O. Ergoline and Non-Ergoline Derivatives in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. 2006, 253 (Suppl. 4), iv36–iv38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Horner, K.A. Dopamine Agonists. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551686/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Rahman, S.; Marwaha, R. Haloperidol. StatPearls [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560892/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Mann, S.K.; Marwaha, R. Chlorpromazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553079/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Athavale, A.; Athavale, T.; Roberts, D.M. Antiemetic Drugs: What to Prescribe and When. Aust. Prescr. 2020, 43, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Djamshidian, A.; Seppi, K.; Poewe, W. Apomorphine for Parkinson’s Disease: Efficacy and Safety of Current and New Formulations. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, A.; Lombardi, G.; Annunziato, L. Cabergoline. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2000, 1, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.P.; Perry, C.M. Cabergoline: A Review of Its Use in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Drugs 2004, 64, 2125–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonne, J.; Goyal, A.; Lopez-Ojeda, W. Dopamine. [Updated 4 July 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535451/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Szymanski, M.W.; Richards, J.R. Fenoldopam. [Updated 27 September 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526058/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Peihua, L.; Jianqin, W. Clinical Effects of Piribedil in Adjuvant Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Open Med. 2018, 13, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M.; Liang, Z. Efficacy of Pramipexole on Quality of Life in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Parmar, M. Pramipexole. [Updated 12 July 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557539/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Rewane, A.; Nagalli, S. Ropinirole. [Updated 15 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554532/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Shill, H.A.; Stacy, M. Update on Ropinirole in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 5, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, P.; Isacson, R.; Kull, B. Dihydrexidine—The First Full Dopamine D1 Receptor Agonist. CNS Drug Rev. 2004, 10, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailman, R.B.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X. D1, Not D2, Dopamine Receptor Activation Dramatically Improves MPTP-Induced Parkinsonism Unresponsive to Levodopa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 892, 173760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajas-Bailador, F.A.; Asencio, M.; Bonilla, C.; Scorza, M.C.; Echeverry, C.; Reyes-Parada, M.; Silveira, R.; Protais, P.; Russell, G.; Cassels, B.K.; et al. Dopaminergic Pharmacology and Antioxidant Properties of Pukateine, a Natural Product Lead for the Design of Agents Increasing Dopamine Neurotransmission. Gen. Pharmacol. 1999, 32, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalefield, R. Veterinary Toxicology for Australia and New Zealand; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boulougouris, V.; Castañé, A.; Robbins, T.W. Dopamine D2/D3 Receptor Agonist Quinpirole Impairs Spatial Reversal Learning in Rats: Investigation of D3 Receptor Involvement in Persistent Behavior. Psychopharmacology 2009, 202, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Reij, R.R.I.; Salmans, M.M.A.; Eijkenboom, I.; van den Hoogen, N.J.; Joosten, E.A.J.; Vanoevelen, J.M. Dopamine-Neurotransmission and Nociception in Zebrafish: An Anti-Nociceptive Role of Dopamine Receptor Drd2a. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 912, 174517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, G.; Reis, R.A.; Sardi, N.F.; Lazzarim, M.K.; Tomim, D.H.; Lima, M.M.S.; Fischer, L. Dopaminergic Mechanisms in Periaqueductal Gray-Mediated Antinociception. Behavioral. Pharmacol. 2018, 29, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. History of the Dopamine Hypothesis of Antipsychotic Action. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, S.; Bistas, K.G.; Saadabadi, A. Fluphenazine. [Updated 8 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459194/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Popovic, D.; Nuss, P.; Vieta, E. Revisiting Loxapine: A Systematic Review. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2015, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, S.M.; Fariba, K.A.; Saadabadi, A. Thioridazine. [Updated 2 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459140/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Haidary, H.A.; Padhy, R.K. Clozapine. [Updated 6 December 2021]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535399/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Thomas, K.; Saadabadi, A. Olanzapine. [Updated 8 September 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532903/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Maan, J.S.; Ershadi, M.; Khan, I.; Saadabadi, A. Quetiapine. [Updated 2 September 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459145/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- McNeil, S.E.; Gibbons, J.R.; Cogburn, M. Risperidone. [Updated 17 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459313/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Bouchette, D.; Fariba, K.A.; Marwaha, R. Ziprasidone. [Updated 8 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448157/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Reddymasu, S.C.; Soykan, I.; McCallum, R.W. Domperidone: Review of Pharmacology and Clinical Applications in Gastroenterology. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 2036–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, S.; Hussain, A.; Dua, A.; Singh, K.; Adams, N. Metoclopramide. [Updated 9 November 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519517/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Din, L.; Preuss, C.V. Prochlorperazine. [Updated 21 September 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537083/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Chakroborty, D.; Goswami, S.; Basu, S.; Sarkar, C. Catecholamines in the Regulation of Angiogenesis in Cutaneous Wound Healing. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 14093–14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papenberg, G.; Jonasson, L.; Karalija, N.; Johansson, J.; Köhncke, Y.; Salami, A.; Andersson, M.; Axelsson, J.; Wåhlin, A.; Riklund, K.; et al. Mapping the Landscape of Human Dopamine D2/3 Receptors with [11C]Raclopride. Brain Struct. Funct. 2019, 224, 2871–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, J.A. SCH 23390: The First Selective Dopamine D1-like Receptor Antagonist. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, X.; Bi, G.H.; Gardner, E.L.; Xi, Z.X. Increased Vulnerability to Cocaine in Mice Lacking Dopamine D3 Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17675–17680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kumar, P.; Jamwal, S.; Deshmukh, R.; Gauttam, V. Tetrabenazine: Spotlight on Drug Review. Ann. Neurosci. 2016, 23, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Sung, V.W. Review of Deutetrabenazine: A Novel Treatment for Chorea Associated with Huntington’s Disease. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018, 12, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Moity, A.R.; Jumonville, A.; Kaufman, S.; Edinoff, A.N.; Kaye, A.D. Valbenazine for the Treatment of Adults with Tardive Dyskinesia. Health Psychol. Res. 2021, 9, 38–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Le, J.K. Amphetamine. [Updated 1 August 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556103/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Sessa, B.; Higbed, L.; Nutt, D. A Review of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, E.; Kunert, O.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Schmid, M.G. Characterization of Three Novel 4-Methylaminorex Derivatives Applied as Designer Drugs. Molecules 2022, 27, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasaei, R.; Saadabadi, A. Methamphetamine. [Updated 8 May 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535356/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Knoll, J.; Yoneda, F.; Knoll, B.; Ohde, H.; Miklya, I. (-)1-(Benzofuran-2-Yl)-2-Propylaminopentane, [(-)BPAP], a Selective Enhancer of the Impulse Propagation Mediated Release of Catecholamines and Serotonin in the Brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 128, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J. Antiaging Compounds: (-)Deprenyl (Selegeline) and (-)1-(Benzofuran-2-Yl)-2-Propylaminopentane, [(-)BPAP], a Selective Highly Potent Enhancer of the Impulse Propagation Mediated Release of Catecholamine and Serotonin in the Brain. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, L.M.; Jasim, S.; Ducharme-Smith, A.; Weingarten, T.; Young, W.F.; Bancos, I. The Role for Metyrosine in the Treatment of Patients With Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, E2393–E2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Matsushima, Y.; Nagatsu, T.; Iinuma, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Umezawa, H. 3,4-Dihydroxystyrene, a Novel Microbial Inhibitor for Phenylalanine Hydroxylase and Other Pteridine-Dependent Monooxygenases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1984, 789, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkers, N.; Sarre, S.; Ebinger, G.; Michotte, Y. Benserazide Decreases Central AADC Activity, Extracellular Dopamine Levels and Levodopa Decarboxylation in Striatum of the Rat. J. Neural. Transm. 2001, 108, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montioli, R.; Voltattorni, C.B.; Bertoldi, M. Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Updates in the Identification of Human Dopa Decarboxylase Inhibitors. Curr. Drug Metab. 2016, 17, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sub Laban, T.; Saadabadi, A. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOI) [Updated 19 July 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539848/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Chong, B.S.; Mersfelder, T.L. Entacapone. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000, 34, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.A.; Winnick, A.; Izygon, J.; Jacob, B.M.; Kaye, J.S.; Kaye, R.J.; Neuchat, E.E.; Kaye, A.M.; Alpaugh, E.S.; Cornett, E.M.; et al. Opicapone, a Novel Catechol-O-Methyl Transferase Inhibitor, for Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease “Off” Episodes. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 36074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, D.D. Tolcapone: Review of Its Pharmacology and Use as Adjunctive Therapy in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 2009, 4, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, J.; Barclay, C.L.; Suchowersky, O. COMT Inhibitors in Parkinson’s Disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 26 (Suppl. 2), S34–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, G.C.; Hsieh, C.L. Antioxidant Effects of Dopamine and Related Compounds. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 1646–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, A.Y.; Erb, H.; Murphy, T.H. Dopamine Activates Nrf2-Regulated Neuroprotective Pathways in Astrocytes and Meningeal Cells. J. Neurochem. 2007, 101, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, M.S.; Trivedi, M.S.; Deth, R.C. Redox-Related Epigenetic Mechanisms in Glioblastoma: Nuclear Factor (Erythroid-Derived 2)-Like 2, Cobalamin, and Dopamine Receptor Subtype 4. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.P.; Hunger, M.; Yard, B.A.; Schnuelle, P.; Woude, F.J. van der Dopamine Induces the Expression of Heme Oxygenase-1 by Human Endothelial Cells in Vitro. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 2314–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanjia, N.D.; Widdison, A.L.; Lutrin, F.J.; Chang, Y.B.; Reber, H.A. The Antiinflammatory Effect of Dopamine in Alcoholic Hemorrhagic Pancreatitis in Cats. Studies on the Receptors and Mechanisms of Action. Gastroenterology 1991, 101, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, S.T.; Louangaphay, K.; Keay, K.; Leggio, G.; Musumeci, G.; Castorina, A. Dopamine: An Immune Transmitter. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rosas, R.; Yehia, G.; Peña, G.; Mishra, P.; Thompson-Bonilla, M.D.R.; Moreno-Eutimio, M.A.; Arriaga-Pizano, L.A.; Isibasi, A.; Ulloa, L. Dopamine Mediates Vagal Modulation of the Immune System by Electroacupuncture. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagogiorgas, C.; Wedel, J.; Hottenrott, M.; Schneider, M.O.; Binzen, U.; Greffrath, W.; Treede, R.D.; Theisinger, B.; Theisinger, S.; Waldherr, R.; et al. N-Octanoyl-Dopamine Is an Agonist at the Capsaicin Receptor TRPV1 and Mitigates Ischemia-Induced [Corrected] Acute Kidney Injury in Rat. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusaro, A.; Russell, J.A. Could Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Catecholamines Explain the Possible Beneficial Effects of Supranormal Oxygen Delivery in Critically Ill Surgical Patients? Intensive Care Med. 2000, 26, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, K.C.L.; Antonelli, L.R.V.; Souza, A.L.S.; Teixeira, M.M.; Dutra, W.O.; Gollob, K.J. Norepinephrine, Dopamine and Dexamethasone Modulate Discrete Leukocyte Subpopulations and Cytokine Profiles from Human PBMC. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 166, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besser, M.J.; Ganor, Y.; Levite, M. Dopamine by Itself Activates Either D2, D3 or D1/D5 Dopaminergic Receptors in Normal Human T Cells and Triggers the Selective Secretion of Either IL-10, TNFα or Both. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 169, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sookhai, S.; Wang, J.H.; Winter, D.; Power, C.; Kirwan, W.; Redmond, H.P. Dopamine Attenuates the Chemoattractant Effect of Interleukin-8: A Novel Role in the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. Shock 2000, 14, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Ding, C.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, R. Dopamine Controls Systemic Inflammation through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cell 2015, 160, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.A.; Reeb, K.L.; Rong, Y.; Matt, S.M.; Johnson, H.S.; Runner, K.; Gaskill, P.J. Dopamine Activates NF-ΚB and Primes the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Primary Human Macrophages. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Bartolomé, M.; Benito-Garzon, L.; Fung, S.; Kohn, J.; Vázquez-Lasa, B.; Román, J.S. Bioadhesive Functional Hydrogels: Controlled Release of Catechol Species with Antioxidant and Antiinflammatory Behavior. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 105, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, E.; Alshathely, M.; Jaleel, G.A. Role of Catecholamine’s Compounds in Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant of Two Plants Santolina Chamaecyparissus and Launaea Mucronata. Pak. J. Nutr. 2015, 14, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P.E.; Jenner, A.; Butler, J.; Aruoma, O.I.; Dexter, D.T.; Jenner, P.; Halliwell, B. Evaluation of the Pro-Oxidant and Antioxidant Actions of L-DOPA and Dopamine in Vitro: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. Free Radic. Res. 1996, 24, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodko-Piórecka, K.; Litwinienko, G. Antioxidant Activity of Dopamine and L-DOPA in Lipid Micelles and Their Cooperation with an Analog of α-Tocopherol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, N.; Rice-Evans, C. Inhibition of Peroxynitrite-mediated Oxidation of Dopamine by Flavonoid and Phenolic Antioxidants and Their Structural Relationships. J. Neurochem. 1999, 73, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.R.; de Cássia Siqueira-Soares, R.; dos Santos, W.D.; Marchiosi, R.; Soares, A.R.; Ferrarese-Filho, O. The Effects of Dopamine on Antioxidant Enzymes Activities and Reactive Oxygen Species Levels in Soybean Roots. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 9, e977704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, K.; Sakakibara, H. High Content of Dopamine, a Strong Antioxidant, in Cavendish Banana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, T.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, K.; Ma, F.; Li, C. Functions of Dopamine in Plants: A Review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1827782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, G.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. Effects of Dopamine on Antioxidation, Mineral Nutrients, and Fruit Quality in Cucumber under Nitrate Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Yin, B.; Zhou, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Han, R.; Shi, C.; Liang, B.; Xu, J. Melatonin and Dopamine Mediate the Regulation of Nitrogen Uptake and Metabolism at Low Ammonium Levels in Malus Hupehensis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 171, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, X.; Chang, C.; Jia, D.; Wei, Z.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Dopamine Alleviates Salt-induced Stress in Malus Hupehensis. Physiol. Plant 2015, 153, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçer, H.; Akıncıoğlu, A.; Öztaşkın, N.; Göksu, S.; Gülçin, İ. Synthesis, Antioxidant, and Antiacetylcholinesterase Activities of Sulfonamide Derivatives of Dopamine-R Elated Compounds. Arch. Pharm. 2013, 346, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.D.; Choi, K. N-Nicotinoyl Dopamine, a Novel Niacinamide Derivative, Retains High Antioxidant Activity and Inhibits Skin Pigmentation. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, S.W.; Hwang, O.; Choi, H.J. Bromocriptine Activates NQO1 via Nrf2-PI3K/Akt Signaling: Novel Cytoprotective Mechanism against Oxidative Damage. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 57, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, I.; Fujita, N.; Haque, M.E.; Asanuma, M.; Ogawa, N. Molecular Mechanism in Activation of Glutathione System by Ropinirole, a Selective Dopamine D2 Agonist. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzeisen, R.; Schwalenstoecker, B.; Gillardon, F.; Buerger, E.; Krzykalla, V.; Klinder, K.; Schild, L.; Hengerer, B.; Ludolph, A.C.; Dorner-Ciossek, C. Targeted Antioxidative and Neuroprotective Properties of the Dopamine Agonist Pramipexole and Its Nondopaminergic Enantiomer SND919CL2x [(+) 2-Amino-4, 5, 6,7-Tetrahydro-6-Lpropylamino-Benzathiazole Dihydrochloride]. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohmiya, M.; Tanaka, M.; Okamoto, K.; Fujisawa, A.; Yamamoto, Y. Synergistic Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation by Vitamin E and a Dopamine Agonist, Cabergoline. Neurol. Res. 2004, 26, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, S.; Antonio, T.; Rajagopalan, S.; Reith, M.; Andersen, J.; Dutta, A.K. Dopamine D2/D3 Agonists with Potent Iron Chelation, Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Properties: Potential Implication in Symptomatic and Neuroprotective Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jin, B.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Lei, S.; Tang, X.; Liang, H.; Liu, Q.; Gong, M.; Peng, R. New Tris (Dopamine) Derivative as an Iron Chelator. Synthesis, Solution Thermodynamic Stability, and Antioxidant Research. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 171, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhanova, I.A.; Sebentsova, E.A.; Khukhareva, D.D.; Vysokikh, M.Y.; Bezuglov, V.V.; Bobrov, M.Y.; Levitskaya, N.G. Early-Life N-Arachidonoyl-Dopamine Exposure Increases Antioxidant Capacity of the Brain Tissues and Reduces Functional Deficits after Neonatal Hypoxia in Rats. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2019, 78, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassen, M.; Gross, A.; Youdim, M.B. Apomorphine, a Dopamine Receptor Agonist with Remarkable Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Properties. Adv. Neurol. 1999, 80, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hara, H.; Ohta, M.; Adachi, T. Apomorphine Protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced Neuronal Cell Death through Activation of the Nrf2-ARE Pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006, 84, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cos, P.; Rajan, P.; Vedernikova, I.; Calomme, M.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Augustyns, K.; Haemers, A.; Berghe, D. vanden In Vitro Antioxidant Profile of Phenolic Acid Derivatives. Free Radic. Res. 2002, 36, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mude, H.; Maroju, P.A.; Balapure, A.; Ganesan, R.; Dutta, J.R. Water-Soluble Caffeic Acid-Dopamine Acid-Base Complex Exhibits Enhanced Bactericidal, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Properties. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Jankovic, J. Dystonia and Dyskinesia. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 20, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisapel, N. Melatonin–Dopamine Interactions: From Basic Neurochemistry to a Clinical Setting. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2001, 21, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamir, E.; Barak, Y.; Shalman, I.; Laudon, M.; Zisapel, N.; Tarrasch, R.; Elizur, A.; Weizman, R. Melatonin Treatment for Tardive Dyskinesia: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Lu, Y. Immunomodulatory Effects of Dopamine in Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 663102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capellino, S. Dopaminergic Agents in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Kumar, A.; Long, H.; Xie, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, J. Dopamine-Melanin Nanoparticles Scavenge Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species and Activate Autophagy for Osteoarthritis Therapy. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11605–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedel, J.; Pallavi, P.; Stamellou, E.; Yard, B.A. N-Acyl Dopamine Derivates as Lead Compound for Implementation in Transplantation Medicine. Transplant. Rev. 2015, 29, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Ji, M.; Lai, D. Chronic Stress Effects on Tumor: Pathway and Mechanism. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 738252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeppner, L.H.; Wang, Y.; Sharma, A.; Javeed, N.; van Keulen, V.P.; Wang, E.; Yang, P.; Roden, A.C.; Peikert, T.; Molina, J.R.; et al. Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonists Inhibit Lung Cancer Progression by Reducing Angiogenesis and Tumor Infiltrating Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.G.; Lin, S.J.; Wu, Z.R.; Guo, Y.H.; Cai, L.; Shang, H.B.; Tang, H.; Xue, Y.J.; Lou, M.Q.; Zhao, W.; et al. Activation of DRD5 (Dopamine Receptor D5) Inhibits Tumor Growth by Autophagic Cell Death. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1404–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Qu, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, F.; Li, X. Effects of Warm Acupuncture Combined with Meloxicam and Comprehensive Nursing on Pain Improvement and Joint Function in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9167956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakmar, E.; Meder, U.; Szakacs, L.; Cseko, A.; Vatai, B.; Szabo, A.J.; McNamara, P.J.; Szabo, M.; Jermendy, A. A Randomized Controlled Study of Low-Dose Hydrocortisone Versus Placebo in Dopamine-Treated Hypotensive Neonates Undergoing Hypothermia Treatment for Hypoxic− Ischemic Encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2019, 211, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, R.J.; Eddleston, J.M.; Pearson, R.C.; Bigley, G.; McMahon, R.F.T. Dopexamine Reduces the Incidence of Acute Inflammation in the Gut Mucosa after Abdominal Surgery in High-Risk Patients. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 27, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, N.P.J.; Phu, N.H.; Bethell, D.P.; Mai, N.T.H.; Chau, T.T.H.; Hien, T.T.; White, N.J. The Effects of Dopamine and Adrenaline Infusions on Acid-Base Balance and Systemic Hemodynamics in Severe Infection. Lancet 1996, 348, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Papazian, L.; Perrin, G.; Saux, P.; Gouin, F. Norepinephrine or Dopamine for the Treatment of Hyperdynamic Septic Shock? Chest 1993, 103, 1826–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfors, B.; Bragadottir, G.; Sellgren, J.; Swärd, K.; RICKSTEN, S. Dopamine Increases Renal Oxygenation: A Clinical Study in Post-cardiac Surgery Patients. Acta Anesthesiol. Scand. 2010, 54, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yongjin, J.; ZiLin, F.; Zhenmei, B. Bromocriptine as an Adjuvant to Cyclosporine Immunosuppression after Renal Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 1997, 1, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, M.; Wild, J.; Pelletier, L.C.; Copeland, J.G. Bromocriptine as an Adjuvant to Cyclosporine Immunosuppression after Heart Transplantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1990, 49, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikiric, P.; Rotkvic, I.; Mise, S.; Petek, M.; Rucman, R.; Seiwerth, S.; Zjacic-Rotkvic, V.; Duvnjak, M.; Jagic, V.; Suchanek, E. Dopamine Agonists Prevent Duodenal Ulcer Relapse: A Comparative Study with Famotidine and Cimetidine. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1991, 36, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Chu, T.; Yang, Z. Pramipexole for Chinese People with Primary Restless Legs Syndrome: A 12-Week Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Lee, S.D.; Kang, S.; Park, H.Y.; Yoon, I. Comparison of the Efficacies of Oral Iron and Pramipexole for the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome Patients with Low Serum Ferritin. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014, 21, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasum, M.; Vrčić, H.; Stanić, P.; Ježek, D.; Orešković, S.; Beketić-Orešković, L.; Pekez, M. Dopamine Agonists in Prevention of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2014, 30, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigas, S.O.; Liu, L.; Strang, S.; Burrasch, C.; Hermsteiner, A.; Münte, T.F.; Park, S.Q. Enhancement in Dopamine Reduces Generous Behavior in Women. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226893. [Google Scholar]

- Lawn, W.; Freeman, T.P.; East, K.; Gaule, A.; Aston, E.R.; Bloomfield, M.A.P.; Das, R.K.; Morgan, C.J.A.; Curran, H.V. The Acute Effects of a Dopamine D3 Receptor Preferring Agonist on Motivation for Cigarettes in Dependent and Occasional Cigarette Smokers. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2018, 20, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, T.F.; Haile, C.N.; Mahoney, J.J., III; Shah, R.; Verrico, C.D.; De La Garza, R., II; Kosten, T.R. Dopamine D3 Receptor-Preferring Agonist Enhances the Subjective Effects of Cocaine in Humans. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, T.P.; Morgan, C.J.A.; Brandner, B.; Almahdi, B.; Curran, H.V. Dopaminergic Involvement in Effort-Based but Not Impulsive Reward Processing in Smokers. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2013, 130, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, T.; Inoue, Y.; Matsuura, M. Effectiveness of Pramipexole, a Dopamine Agonist, on Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2012, 226, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sziklai, I.; Szilvássy, J.; Szilvássy, Z. Tinnitus Control by Dopamine Agonist Pramipexole in Presbycusis Patients: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind Study. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, A.J.; Myers, R.R. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pramipexole, a Dopamine Agonist, in Patients with Fibromyalgia Receiving Concomitant Medications. Arthritis Rheum 2005, 52, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov. Dopamine Versus Norepinephrine for the Treatment of Vasopressor Dependent Septic Shock. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00604019?term=NCT00604019&draw=2&rank=1&view=results (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Dopamine vs. Norepinephrine for Hypotension in Very Preterm Infants with Late-Onset Sepsis. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05347238?term=NCT05347238&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Management of Shock in Children With SAM or Severe Underweight and Diarrhea. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04750070?term=NCT04750070&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Intra-Renal Therapy of Diuretic Unresponsive Acute Kidney Injury (IR-FTA). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01073189?term=NCT01073189&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Enhancing Renal Graft Function During Donor Anesthesia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03778944?term=NCT03778944&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. DIalysis Symptom Control-Restless Legs Syndrome Trial (DISCO-RLS). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03806530?term=NCT03806530&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Fenoldopam to Prevent Renal Dysfunction in Indomethacin Treated Preterm Infants (Fenaki). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02620761?term=NCT02620761&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Fenoldopam and Ketanserin for Acute Kidney Failure Prevention After Cardiac Surgery. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00557219?term=NCT00557219&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Fenoldopam in Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00982527?term=NCT00982527&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Fenoldopam and Acute Renal Failure (FENO HSR). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00621790?term=NCT00621790&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Treatment Use of Domperidone for Gastroparesis. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02227927?term=NCT02227927&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Domperidone for Relief of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00761254 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome and Cabergoline. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01569256?term=NCT01569256&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Tolerability of Quinagolide in a Dose-Titration Regimen in Oocyte Donors at Risk of Developing Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00665041?term=NCT00665041&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Study of Cabergoline in Treatment of Corticotroph Pituitary Tumor. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00889525?term=NCT00889525&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Bromocriptine Quick Release (BCQR) as Adjunct Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02544321?term=NCT02544321&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Bromocriptine-QR Therapy on Sympathetic Tone and Vascular Biology in Type 2 Diabetes Subjects. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02682901?term=NCT02682901&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Cabergoline Effect on Blood Sugar in Type 2 Diabetics. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01459601?term=NCT01459601&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Clinical Tryals.gov. Effect of Cycloset on Glycemic Control When Added to Glucagon-like Peptide 1 (GLP-1) Analog Therapy. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02299050?term=NCT02299050&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).