Abstract

The present review describes the various roles of cyclodextrins (CDs) in vaccines against viruses and in antiviral therapeutics. The first section describes the most commonly studied application of cyclodextrins—solubilisation and stabilisation of antiviral drugs; some examples also refer to their beneficial taste-masking activity. The second part of the review describes the role of cyclodextrins in antiviral vaccine development and stabilisation, where they are employed as adjuvants and cryopreserving agents. In addition, cyclodextrin-based polymers as delivery systems for mRNA are currently under development. Lastly, the use of cyclodextrins as pharmaceutical active ingredients for the treatment of viral infections is explored. This new field of application is still taking its first steps. Nevertheless, promising results from the use of cyclodextrins as agents to treat other pathologies are encouraging. We present potential applications of the results reported in the literature and highlight the products that are already available on the market.

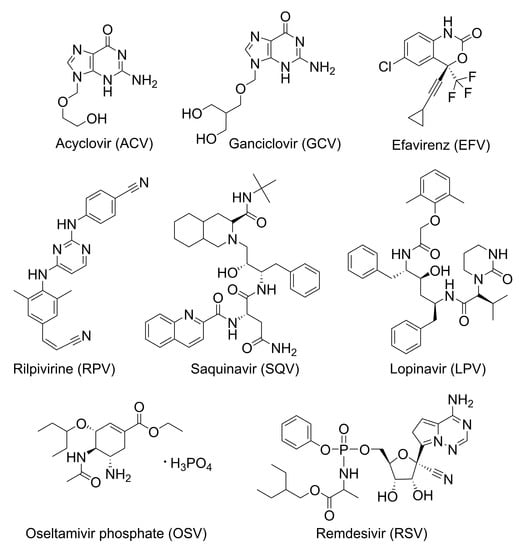

1. Introduction

Viral infections pose strong risks to human health and survival [1]. In 2017, diseases caused by virus agents were responsible for more than 2% of the global death count of 56 million, with infection from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causing more than 954,000 casualties (c.a. 1.7%), and hepatitis (A, B, and C) and influenza infections accounting each roughly 125,000 deaths (c.a. 0.2%) [2]. Recent outbreaks of viral infections further contribute to demonstrate that, in spite of the efforts made by health care organisations around the globe to reduce and control the impact of these pathogens on human health, threats may arise without warning and can easily spread. Examples include the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus (CoV) designated SARS-CoV that broke out in China from 2002 to 2003 [3], the pandemic influenza caused by a swine H1N1 influenza A virus in 2009 [4], the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012 caused by a new virus called MERS-CoV [5], the Ebola outbreak in West Africa between 2014 and 2016 [6], and the currently ongoing outbreak of a coronavirus infectious disease (COVID-19) that started in the last months of 2019 and is attributed to a new virus, SARS-CoV2. The complex evolution of the current pandemic has been pushing its resolution to an increasingly distant horizon. Three new and more infective variants emerged at the end of 2020, some of them potentially more virulent. Vaccination, the eagerly anticipated solution, is still taking its first steps and progressing slowly, with much yet to be learned about efficacy towards new variants and the actual length of immunisation [7].

In the future, more outbreaks can be expected as the increased pressure on once untouched ecosystems will put mankind in close contact with unknown mammal viruses, estimated to exist in high numbers as much as 320,000, and to have a strong possibility of transmission to humans [8]. Tackling these emerging viral infections requires strong research efforts with a multidisciplinary scope that integrates simple approaches, such as repurposing drugs [9], and in-depth, long-term studies to develop new active chemical entities [10], medicinal biomolecules [11], and vaccines [10]. Moreover, actives often require the support of adequate inert materials to ensure stabilisation, solubilisation [12], and bioavailability [13,14].

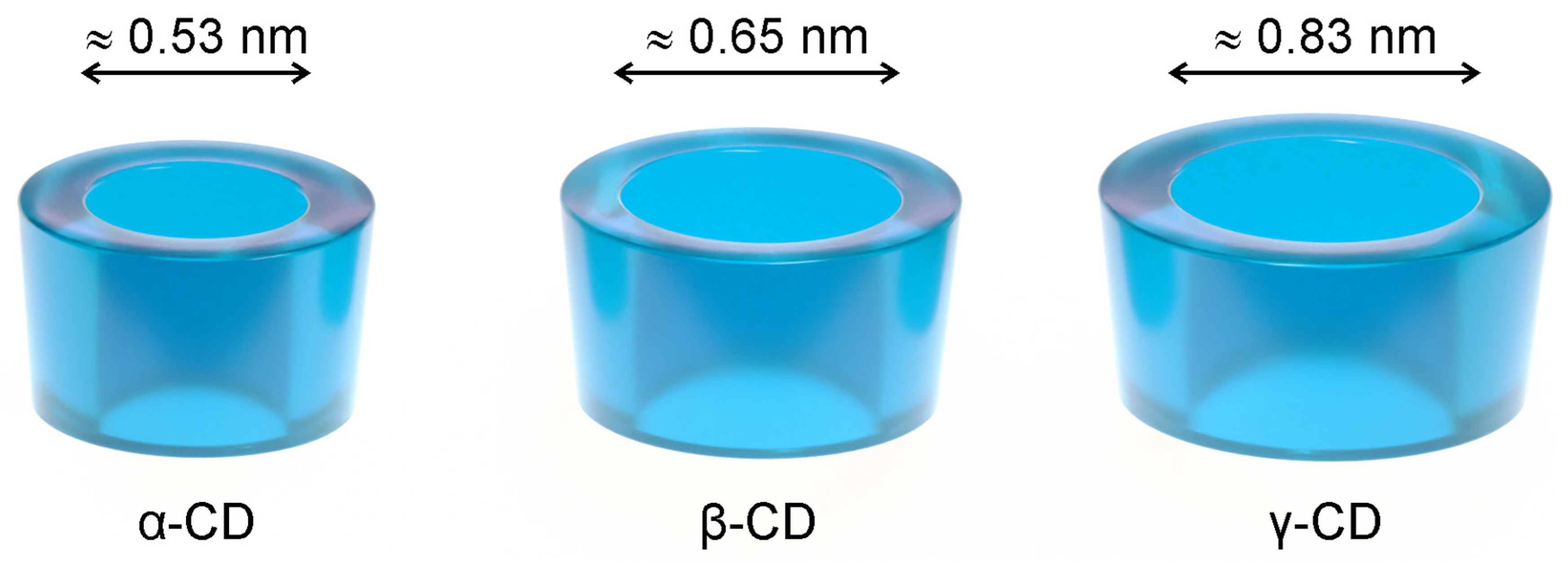

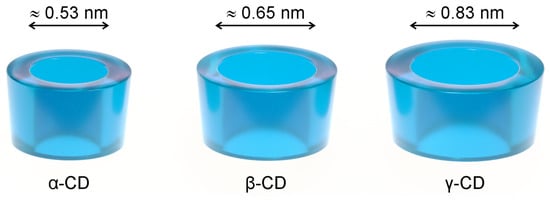

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are used as solubilisers, taste-masking, and stabilising agents in various drug formulations, from solid oral dosage forms to injectables [15,16], also appearing as ingredients in cosmetics [17,18] and food products. Native cyclodextrins are naturally occurring cyclic oligosaccharides composed of six to eight α-1,4-linked D-glucose units (α-, β- and γ-CD). They have the shape of a truncated cone (Figure 1), with the secondary hydroxyl groups facing the wider rim and the primary ones facing the narrower rim. This unique geometry allows them to dissolve fairly well in water while keeping a hydrophobic cavity that accommodates molecules with a size and geometry adequate to each cyclodextrin. While the solubilising effect is the most obvious consequence of the geometry of cyclodextrins, these hosts are able to mask the unpleasant taste of included guest molecules and protect them against oxidation and the damaging action of heat or UV radiation [19,20,21].

Figure 1.

The three most abundant native cyclodextrins (CDs), α-CD, β-CD, and γ-CD, schematically drawn as truncated cones. An estimate of the inner cavity diameter is presented for each [20].

Native cyclodextrins are quite safe for ingestion because they are practically not absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In Japan, they are even considered natural products and their use in foods is very widespread. In the rest of the world, they are GRAS products, i.e., they are ‘generally regarded as safe’ to ingest from foods [22,23,24] and oral pharmaceutical dosage forms [16,25,26,27]. Two of the native cyclodextrins (α-CD and β-CD) should not, however, be administered directly into the bloodstream, because they have renal toxicity [16]. Moreover, native cyclodextrins are haemolytical, (observed in vitro at concentrations of 6, 3, and 16 mM for α-, β- and γ-CDs, respectively) [28] as a result of their ability to extract phospholipids and cholesterol from the erythrocyte membrane [29].

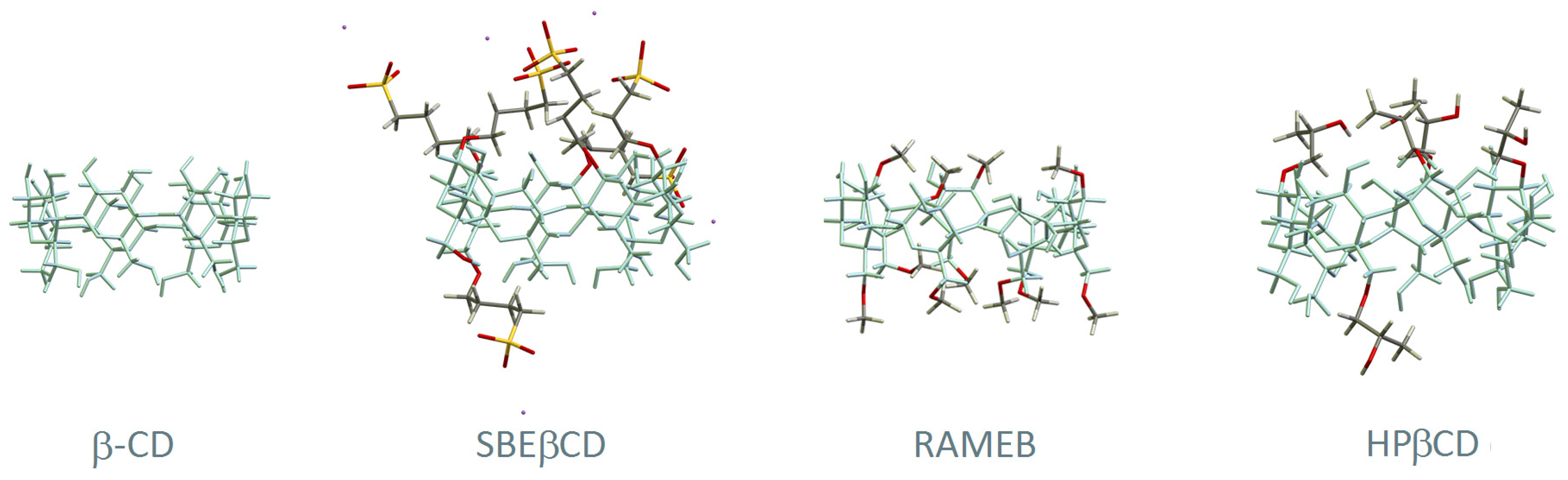

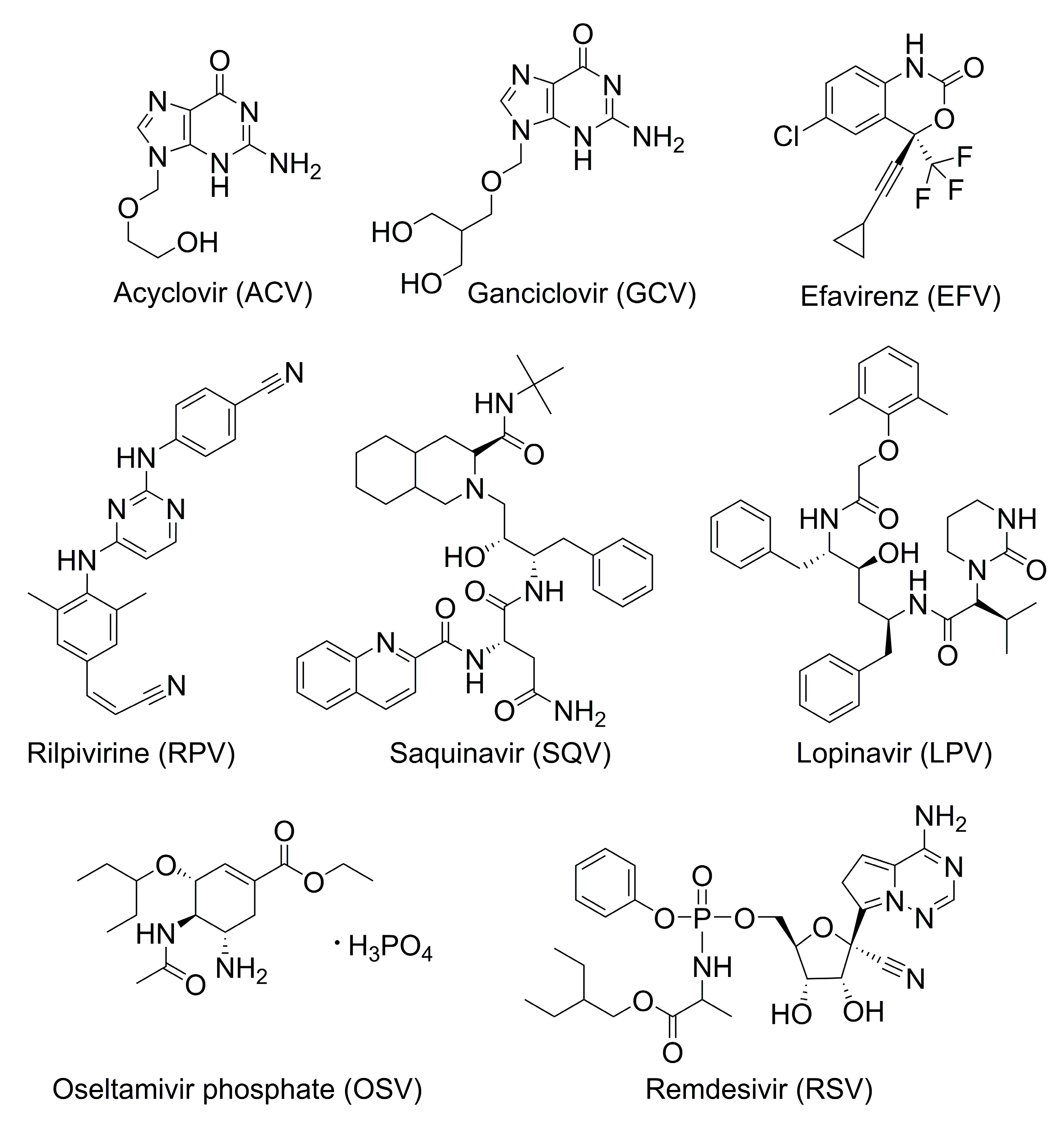

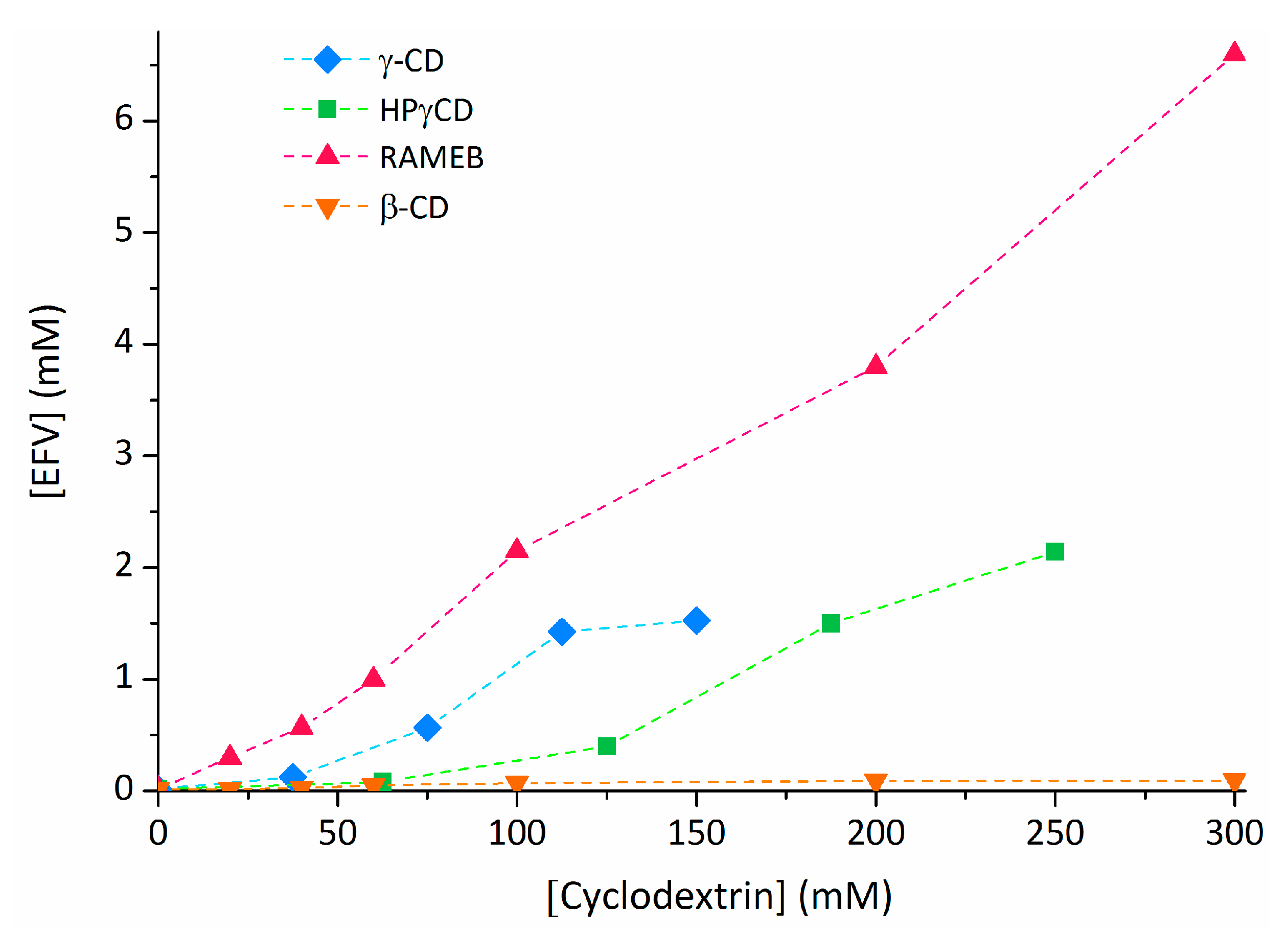

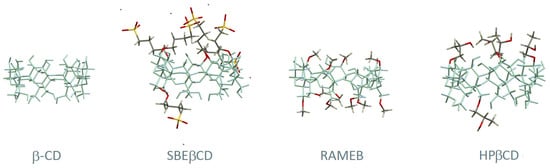

Chemically modified cyclodextrins are obtained from the native ones through functionalisation of their hydroxyl groups with a myriad of substituents and combinations thereof. A report of 2012 mentioned more than 1500 known cyclodextrin derivatives [30], with the current number expected to be much higher. The most used ones in the field of pharmaceutics are represented in Figure 2. 2-hydroxypropylated (HP) derivatives are among the ones with the most widespread use, in particular HPβCD for its high safety and tolerability. HPγCD is restricted to topical use at a maximum concentration of 1.5% (w/v). Methylated derivatives are also employed in a few pharmaceuticals, particularly in RAMEB and DIMEB. DIMEB, or heptakis-2,6-di-O-methyl-β-CD, is a per-functionalised derivative at the hydroxyl groups 2 and 6. It has moderate hepatic toxicity, with doses of 300 mg/kg in mice causing increased levels of two biomarkers of hepatic injury: glutamate–pyruvate transaminase and glutamate–oxaloacetate transaminase [31]. Nevertheless, trace amounts of DIMEB are found in three injectable bacterial vaccines [32], in which DIMEB was used as a culture medium modifier for growing the bacteria. RAMEB is a randomly methylated beta-cyclodextrin averaging 1.8 methoxyl groups per glucose unit. It can only be used in topical formulations because of its high affinity to cholesterol which results in strong haemolytic activity [33,34] and renal toxicity superior to that of the parent β-CD. Another biocompatible CD is sulfobutyl ether β-CD (SBEβCD), developed to be non-nephrotoxic and present in several FDA-approved pharmaceuticals for both oral and intravenous administration [35]. Table 1 presents a summary of pharmaceutical uses of cyclodextrins, along with their toxicity and restrictions to use, compiled from data of European Medicines Agency (EMA) [16], the United States Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) [25,26,27,32,35], and the joint WHO/FAO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) [22,23,24].

Figure 2.

Structural representation of β-CD and three of its derivatives: (2-hydroxy)propyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), randomly methylated beta-cyclodextrin (RAMEB), and sulfobutyl ether β-CD (SBEβCD). The main skeleton of β-CD is represented in blue and the substituent groups are highlighted with different colours (carbon in grey, oxygen in red, hydrogen in white, sulphur in yellow and sodium in purple).

Table 1.

Summary of pharmaceutical products containing native and chemically modified cyclodextrins, their allowed daily intake from oral intake (ADI), restrictions to use (maximal dose), and main toxicity issues.

Information in this table was compiled from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [16], the United States Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) [25,26,27,32,35], and the joint WHO/FAO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) for the oral intake [22,23,24].

3. Cyclodextrins in Vaccines

3.1. Cyclodextrins as Vaccine Cryopreservatives: The Example of ad26.cov2.s

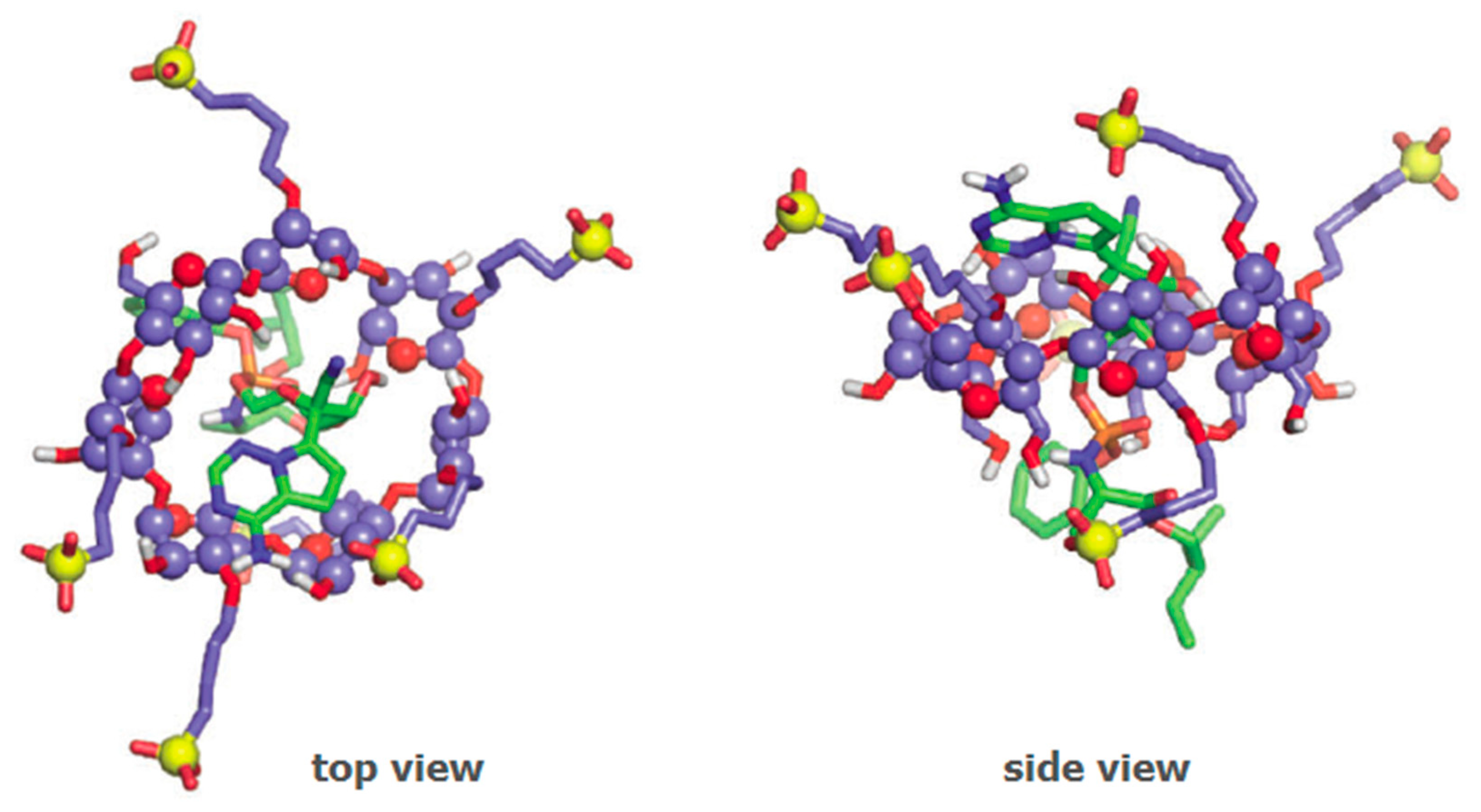

Several vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 are either under clinical development or already available under emergency use authorisation. The active ingredient in these vaccines is a nucleotidic chain to encode the immunogenic viral spike protein, with variations in the nature of the nucleic acids therein employed (mRNA or DNA) and in the kind of vector used to load the active component. The vaccine developed by Janssen with the name ad26.cov2.s has received emergency use authorisation of the FDA [87] and the EMA [88] in early March 2021. The vaccine, developed for the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, is based on viral DNA carried by a synthetic adenovirus vector and containing HPβCD as a cryopreservative (Figure 6) [89]. It is formulated as a re-suspendable powder for intramuscular administration, which implies that it requires a freeze-drying step during the preparation process. Low temperatures associated with the freeze-drying step are susceptible to causing damage to the surface of viruses. For this reason, HPβCD is included in the formulation as a cryopreservative, that is, to avoid cold-induced damage to the surface of the viral particles [90]. The process underlying the cryopreservative action of HPβCD with adenovirus particles is not elucidated. In semen cryopreservation, the preserving action was attributed to the interaction of HPβCD with cholesterol molecules on the membrane of these eukaryotic cells [91]. Adenoviruses, however, are not enveloped viruses, having only a protein capsid. The absence of the lipid envelope excludes the possibility of interaction with cholesterol or any other lipids.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the interactions between adenovirus particles (orange) and HPβCD molecules (blue) in the ad26.cov2.s vaccine. Cyclodextrin molecules are used in large excess and claimed to act as cryopreservatives, helping to stabilise the surface of the virus during the freeze-drying step of the vaccine preparation.

3.2. Cyclodextrins as Vaccine Adjuvants

Cyclodextrins can help stimulate immune cell response, being thus suitable for usage as vaccine adjuvants. The first known cyclodextrin-adjuvanted commercial vaccine is a veterinary product with sulfolipo-β-cyclodextrin (SL-β-CD), a new derivative that was developed purposely to this end [92]. With an average substitution of 1.19 sulphate groups and 8.19 lipid residues per each cyclodextrin, SL-β-CD is an amphiphilic molecule that can be incorporated into oil/water emulsions. Squalene/water emulsions containing SL-β-CD were established as a new adjuvant medium for their toxicological safety and the ability to induce antibody response [92] and high lymphocyte proliferation in animal models [93]. We must note, however, that SL-β-CD is only approved for veterinary use.

In human vaccines, HPβCD is the best choice for adjuvanticity because it is already approved by the regulating entities and it has an excellent safety profile. Moreover, HPβCD is able to induce lymphocyte proliferation, especially the T-helper type 2 (Th2) cells. These cells, also known as CD4+ cells, are an important part of the immunisation effect of vaccines, contributing to maintaining a longer immune response. HPβCD is more advantageous than aluminium salts, which are currently the most commonly employed adjuvants. Unlike aluminium, HPβCD induces little immunoglobulin E (IgE) production, thus reducing the allergenic risk of the vaccine.

3.2.1. Porcine Circovirus Vaccine

In 2013, the company Zoetis launched ‘Suvacyn PCV’, an inactivated recombinant porcine circovirus type 1 vaccine based on one of the viral proteins, which contained also the adjuvants squalene (32 mg/mL) and SL-β-CD (2 mg/mL) [94]. SL-β-CD was reported to induce a rapid onset of immunity and generate a better immune response as compared to Carbopol® (polyacrylic acid), used in previous formulations of the vaccine.

3.2.2. Human Influenza Vaccine

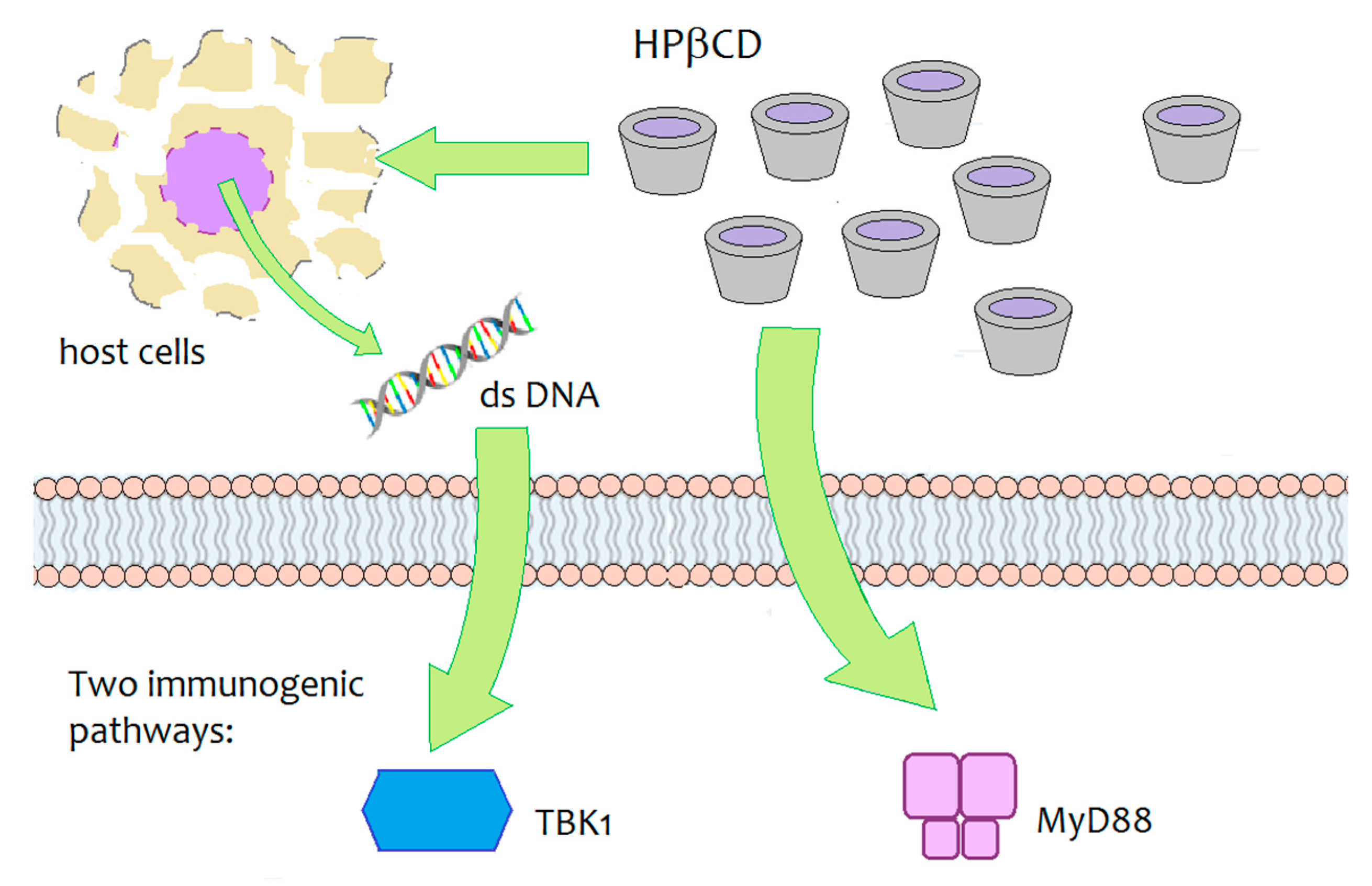

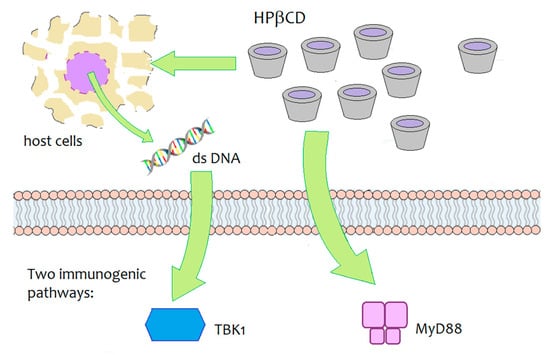

Daiichi Sankyo, a Japanese pharmaceutical company, is developing an innovative vaccine for influenza that contains HPβCD as an innovative adjuvant agent. During the development studies of the vaccine with various animal models, HPβCD was shown to induce a synergic immune response by interacting with immunoglobulins, increasing antibody production by 30% and inducing the production of Th2 cells, responsible for long-term immune ‘memory’, as well as the generation of follicular B helper T cells (Thf) that in turn stimulate B cells (responsible for the long-term immune ‘memory’) [95,96]. The immunogenic activity of HPβCD, when co-administered with an antigen (ovalbumin), was investigated in mouse models. The underlying biomolecular mechanism was not fully elucidated, but results have demonstrated that two signalling pathways are involved— the MyD88-dependent pathway and the TBK1-dependent pathway (Figure 7) [95]. The TBK1-dependent signalling pathway was shown to be triggered by the release of dsDNA around the site of injection and it resulted in an enhanced Th2-type immune response. At the same time, HPβCD induced a MyD88-dependent response, which may help modulate the response upregulated by the dsDNA/TBK1 axis. The authors stated the need for further studies to identify the critical upstream/downstream pathways of MyD88 and TBK1 induced by local administration of HPβCD.

Figure 7.

Schematic depiction of the biomolecular targets of HPβCD-mediated immunogenicity in mice [95].

The positive results in animal studies encouraged the development of the human vaccine. The vaccine is designed for administration by the nasal route, reducing the discomfort of the yearly injections needed for the vaccination of elderly patients and those in risk groups. Currently, it is still under phase I trials [97]. Some results have already been published, showing that, in spite of the local administration at the nasal mucosa, the vaccine is able to generate a systemic immune response that occurs not only at the nasal mucosa but spreads to the entire organism to promote immunisation [98]. Approval of the first cyclodextrin-adjuvanted human vaccine will open the way for a new class of vaccines with higher safety profiles. The presence of aluminium salts in vaccines is a strong cause of concern and vaccination refusal for many patients. Replacing it with a safe adjuvant is expected to help regain the trust of patients and to contribute to widespread vaccination acceptance.

3.3. Cyclodextrins in mRNA Vaccines—A Future Trend?

Vaccines based on mRNA have set a new milestone in scientific development and in the control of the presently ongoing SARS-CoV2 pandemic. The development of these vaccines holds a new record for the shortest lab-to-market transition. This occurred because of the emergency use authorisation of regulated entities, which speeded the regulatory process. It also benefited from the strong advantages of the mRNA technology itself. Using nucleic acids as the active ingredient eliminates the time-consuming process of growing and inactivating viruses, which allowed the vaccines to be developed and tested as soon as the SARS-CoV2 viral genome was known. mRNA vaccines use the cells of the patient to produce the encoded viral proteins, generating immunostimulating particles inside the body. For this to happen, mRNA needs to be delivered to the cells while ensuring it does not suffer from the lytic action of the ribonucleases of the patient. The vector must also ensure that mRNA does enter the cytoplasm of the cells, where it will be free to exert its action. In the first two approved SARS-CoV2 mRNA vaccines, lipid nanoparticles were chosen as the vector owing to their good biocompatibility, facile preparation via microfluidics, and surface tuneability, which allows targeting specific cells [99]. These vaccines require, however, refrigeration at very low temperatures (one at −20 and the other at −70 °C), which may limit their widespread use [100].

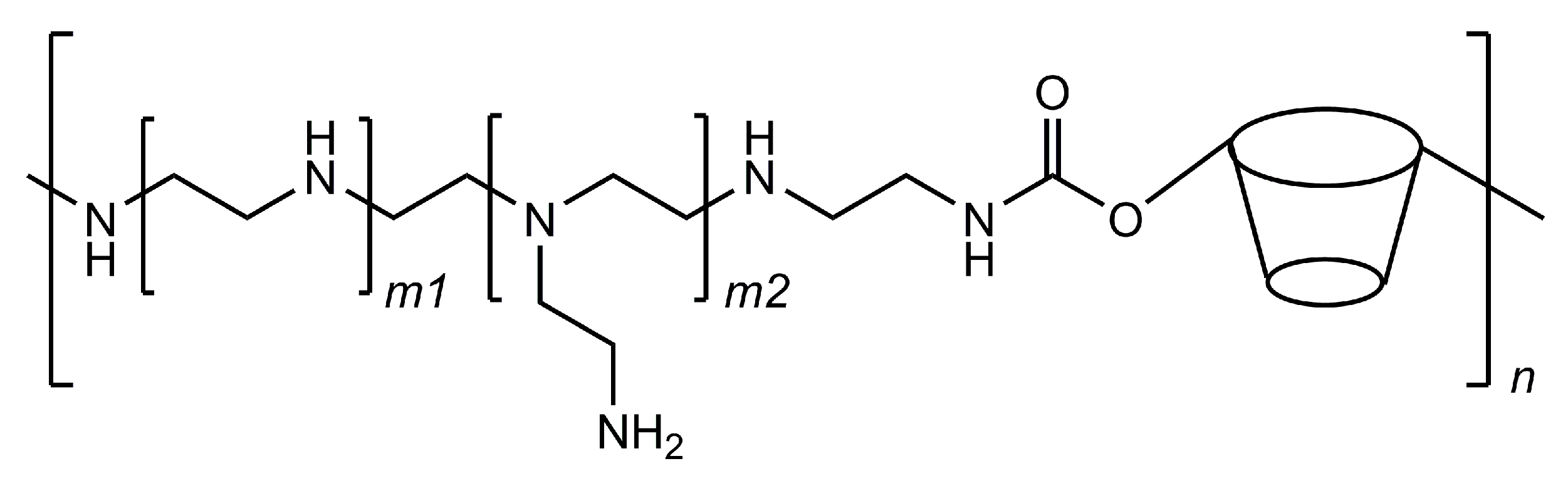

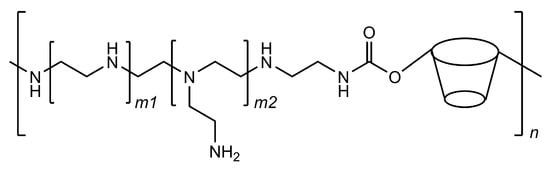

Following the release of the first two vaccines based on mRNA technology, researchers are seeking to further develop this technology by producing new vehicles for the nucleic acid chains. One of these strategies is based on cyclodextrin polymers that are designed to have polycationic charges so that they can interact with negatively charged molecules, such as DNA and RNA. Cyclodextrins help to stabilise the interactions, possibly by the inclusion of a few nucleobase residues and avoid the premature precipitation of the formed polycomplexes. More importantly, cyclodextrins help in making these systems more effective in the cell transfection phase because they are able to interfere with cellular membranes and increase their permeability. [101] These carriers are typically cyclodextrin–polyethyleneimine conjugated polymers (CD–PEI) that can be adapted to deliver different kinds of nucleic acid chains by customising the polyethyleneimine fragments (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Structural representation of the cyclodextrin–polyethyleneimine conjugated polymer; the ratio of cyclodextrin residues in the polymer can be tuned by varying the length at the m1 and m2 subunits.

A CD–PEI designed for mRNA vectorisation was recently reported [102]. CD–PEI and mRNA interacted to form adducts coined as nanocomplexes, which were shown to help mRNA reach the cytoplasm and transfect mouse dendritic cells (DC2.4 line) with high efficiency and to induce the expression of encoded proteins at high levels. The administration of the nanocomplexes was tested by different routes. Intramuscular injection-induced both IgG1 and IgG2a, with an IgG1 to IgG2a ratio of 1.34; intradermal administration primarily induced IgG2a antibodies and yielded an IgG1 to IgG2a ratio of 0.65. The authors noted that ratios between 0.5 and 2 indicate a mixed response of these two antibody classes.

While CD–PEIs remain as investigational compounds by lack of clinical studies to provide information on their biocompatibility, a similar class of cationic polymers (also based on iminium-β-CD units) was successfully used to deliver small interfering RNA to human cancer patients in a clinical trial [103]. These results may open the way for a range of future applications of CD-imine polymers in nucleic acid delivery.

5. Conclusions

This review presents a compilation of the different roles of cyclodextrins in the prevention and therapeutics of viral infections. While a large number of reports continue to study their classical role as solubilisers for hydrophobic drugs, this area is not very dynamic in terms of translation into the clinic. One likely reason is the high amount of cyclodextrins used in oral solid formulations, which increases the cost of the medicine. The golden exception is VekluryTM (remdesivir), a recently approved drug for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection which contains SBEβCD as the solubilising agent.

In our perspective, the field of vaccines is the one in which cyclodextrins have the strongest potential for development. The recently approved Janssen vaccine against SARS-CoV2 infection (ad26.cov2.s) sets a milestone for cyclodextrins in this field. Its global usage and the observation data resulting from monitoring the reports on any adverse effects from billions of patients will serve as a large-scale test to the safety of HPβCD, which it contains under the label of cryopreservative. If it passes this test, HPβCD will definitively consolidate its role as a compound of immense interest in biopharmaceuticals.

The main setback to a broader expansion of the usage of cyclodextrins in medicines and vaccines is the lack of information on their biological properties and, most importantly, on their safety. These studies are unavailable for the vast majority of chemically functionalised cyclodextrins. For the ones which have already been evaluated and approved for human use, such as HPβCD, reports continue to reveal more data on properties that were little explored, such as the effect on the immune system. It is currently known that HPβCD can act as an immunostimulant, with prolonged exposures (rats taking 0.4 g/kg/day for three months) causing increased monocyte (+150%) and overall white blood cells counts (15%) [127], and a single co-administration with an antigen (albumin) increasing proliferation of Th2 and Thf lymphocytes [95]. The molecular mechanisms of the immunostimulating action of HPβCD warrant, however, a more in-depth investigation. These studies should help understand the action of HPβCD in healthy individuals, immunocompromised patients, and those with autoimmune conditions, contributing to finding new therapeutic indications and possible counter-indications.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge University of Aveiro and FCT/MCTES (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Ministério da Ciência, da Tecnologia e do Ensino Superior) for financial support to LAQV-REQUIMTE (Ref. UIDB/50006/2020) and CICECO—Aveiro Institute of Materials (UIDB/50011/2020 and UIDP/50011/2020). We also thank FCT for the Ph.D. grant No. PD/BD/135104/2017 to J.S.B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACV | acyclovir |

| API | active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| BCS | biopharmaceutical classification system |

| CD | cyclodextrin |

| CHMP | committee for medicinal products for human use |

| DIMEB | heptakis-2,6-di-O-methyl-β-CD |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| FDA | US Food and Drugs Administration |

| EFV | efavirenz |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EMEM | Eagle’s minimum essential medium |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| GCV | ganciclovir |

| HCMV | human cytomegalovirus |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| HPβCD | (2-hydroxyl)propyl-β-CD |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HSV | herpex simplex virus |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| LPV | lopinavir |

| MERS | Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome |

| MLK | montelukast sodium |

| m.o.i. | multiplicity of infection |

| MV | measles virus |

| MyD88 | myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 |

| NS-1 | non-structural protein 1 |

| OSV | oseltamivir phosphate (TamifluTM) |

| PAA | poly(amidoamine) |

| PBS | phosphate buffer saline |

| PEG | polyethyleneglycol |

| PEI | polyethyleneimine |

| RBV | ribavirin |

| RAMEB | randomly methylated β-CD |

| RPV | rilpivirine |

| RSV | remdesivir |

| RTV | ritonavir |

| SARS | severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SBEβCD | sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (Captisol®) |

| SD | spray-dried |

| SL-β-CD | sulfolipo-β-CD |

| SLS | sodium lauryl sulphate |

| SQV | saquinavir |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 Th2, type 2 T-helper |

| TRIMEB | heptakis-2,3,6-tris-O-methyl β-CD |

| VZV | varicella-zoster virus |

References

- Luo, G.; Gao, S.-J. Global health concerns stirred by emerging viral infections. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouchier, R.A.M.; Kuiken, T.; Schutten, M.; van Amerongen, G.; van Doornum, G.J.J.; van den Hoogen, B.G.; Peiris, M.; Lim, W.; Stöhr, K.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature 2003, 423, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijaykrishna, D.; Poon, L.L.M.; Zhu, H.C.; Ma, S.K.; Li, O.T.W.; Cheung, C.L.; Smith, G.J.D.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Guan, Y. Reassortment of pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza A virus in swine. Science 2010, 328, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Hui, D.S.; Perlman, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseler, L.; Chertow, D.S.; Johnson, K.M.; Feldmann, H.; Morens, D.M. The pathogenesis of Ebola virus disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2017, 12, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, M.D.; Graham, B.S.; Lane, H.C.; Fauci, A.S. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Much accomplished, much to learn. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, S.J.; Epstein, J.H.; Murray, K.A.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M.; Solovyov, A.; Ojeda-Flores, R.; Arrigo, N.C.; Islam, A.; Khan, S.A.; et al. A strategy to estimate unknown viral diversity in mammals. mBio 2013, 4, e00598–e00613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serradilla, M.; Risco, C.; Pacheco, B. Drug repurposing for new, efficient, broad spectrum antivirals. Virus Res. 2019, 264, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.I.; Ianevski, A.; Lysvand, H.; Vitkauskiene, A.; Oksenych, V.; Bjørås, M.; Telling, K.; Lutsar, I.; Dumpis, U.; Irie, Y.; et al. Discovery and development of safe-in-man broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Qian, K.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Fu, W.; Ding, M.; Hu, S. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M.K.; Ray, A.S.; Mackman, R.L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H.C.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Li, Y.; Reed, B.; Shen, X.; Sun, D.; Zhou, S. Cyclodextrin affects distinct tissue drug disposition as a novel drug delivery vehicle. Ann. Med. Med. Res. 2019, 2, 1021. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, R.L.; Miller, L.A.; Ahmed, I. The utility of cyclodextrins for enhancing oral bioavailability. J. Control. Release 2007, 123, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenyvesi, É. Approved pharmaceutical products containing cyclodextrins. Cyclodext. News 2013, 26, 1–4. Available online: https://cyclolab.hu/userfiles/cdn_2013_feb.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- European Medicines Agency. Background Review for Cyclodextrins Used as Excipients; EMA: London, UK, 2014; Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2014/12/WC500177936.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Buschmann, H.-J.; Schollmeyer, E. Applications of cyclodextrins in cosmetic products: A review. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2002, 53, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, S.S.; Pais, J. Getting under the skin: Cyclodextrin inclusion for the controlled delivery of active substances to the dermis. In Design of Nanostructures for Versatile Therapeutic Applications, 1st ed.; Grumezescu, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Chapter 10; pp. 407–449. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, J.S.; Almeida Paz, F.A.; Braga, S.S. Montelukast medicines of today and tomorrow: From molecular pharmaceutics to technological formulations. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 3257–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, E.M. Cyclodextrins and their uses: A review. Process. Biochem. 2004, 39, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Gupta, V. Cyclodextrins—A Review on pharmaceutical application for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. Front. Res. 2012, 2, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kroes, R.; Verger, P.; Larsen, J.C. Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives (α-Cyclodextrin-Addendum); WHO Food Additives Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 54, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pollit, F.D. Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives (β-Cyclodextrin); WHO Food Additives Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996; Volume 35, pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, P.J. JEFCA 55th Meeting: Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants (γ-Cyclodextrin); WHO Food Additives Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Volume 44, p. 969. [Google Scholar]

- Agency Response Letter Gras Notice GRN No. 155; Office of Food Additive Safety, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004.

- Agency Response Letter Gras Notice GRN No. 74; Office of Food Additive Safety, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001.

- Agency Response Letter Gras Notice GRN No. 46; Office of Food Additive Safety, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000.

- Irie, T.; Otagiri, M.; Sunada, M.; Uekama, K.; Ohtani, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Sugiyama, Y. Cyclodextrin-induced hemolysis and shape changes of human erythrocytes in vitro. J. Pharm. Dyn. 1982, 5, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, Y.; Irie, T.; Uekama, K.; Fukunaga, K.; Pitha, J. Differential effects of α-, β- and γ-cyclodextrins on human erythrocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989, 186, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitalikar, M.M.; Sakarkar, D.M.; Jain, P.V. The cyclodextrins: A review. J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 2012, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Uekama, K.; Hirayama, F.; Irie, T. Pharmaceutical uses of Cyclodextrin Derivatives. In High Performance Biomaterials, A Comprehensive Guide to Medical and Pharmaceutical Applications, 1st ed.; Szycher, M., Ed.; Technomic: Lancaster, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 789–806. [Google Scholar]

- Excipients in Vaccines per 0.5 mL Dose. Available online: https://www.vaccinesafety.edu/components-Excipients.htm (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Szente, L.; Singhal, A.; Domokos, A.; Song, B. Cyclodextrins: Assessing the impact of cavity size, occupancy, and substitutions on cytotoxicity and cholesterol homeostasis. Molecules 2018, 23, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Fenyvesi, F.; Bácskay, I.; Váradi, J.; Fenyvesi, É.; Iványi, R.; Szente, L.; Tósaki, Á.; Vecsernyé, M. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of β-cyclodextrin derivatives: Evidence for the role of cholesterol extraction. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 40, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captisol. Available online: https://www.captisol.com/technology/history (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Lin, P.; Torres, G.; Tyring, S.K. Changing paradigms in dermatology: Antivirals in dermatology. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 21, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruance, S.L.; Nett, R.; Marbury, T.; Wolff, R.; Johnson, J.; Spaulding, T.; The Acyclovir Cream Study Group. Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: Results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, J.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, I.; Bermejo, M.; Amidon, G.L.; Juninger, H.E.; Kopp, S.; Midha, K.K.; Shah, V.P.; Stavchansky, S.; Dressman, J.B.; et al. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Aciclovir. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 5061–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpe, M.; Mali, N.; Kadam, V. Formulation development and evaluation of acyclovir orally disintegrating tablets. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rossel, C.P.; Carreño, J.S.; Rodríguez-Baeza, M.; Alderete, J.B. Inclusion complex of the antiviral drug acyclovir with cyclodextrin in aqueous solution and in solid phase. Quím. Nova 2000, 23, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, P.B.; Dandagi, P.; Udupa, N.; Gopal, S.V.; Jain, S.S.; Vasanth, S.G. Controlled release polymeric ocular delivery of acyclovir. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2010, 15, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, V.; Garud, N.; Kannojia, P.; Garud, A.; Jain, N.; Singh, N. Enhancement of solubility of acyclovir by solid dispersion and inclusion complexation methods. Pharm. Lett. 2010, 2, 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, J.; Aránguiz, T.; Sepúlveda, J.; Hernández, L.; von Plessing, C. Preliminary pharmacokinetic study of different preparations of acyclovir with β-cyclodextrin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 91, 2593–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.B.; Attimarad, M.; Al-Dhubiab, B.E.; Wadhwa, J.; Harsha, S.; Ahmed, M. Enhanced oral bioavailability of acyclovir by inclusion complex using hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 21, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencini, M.; Ranucci, E.; Ferruti, P.; Trotta, F.; Donalisio, M.; Cornaglia, M.; Lembo, D.; Cavalli, R. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of the antiviral activity of the Acyclovir complex of a β-cyclodextrin/poly(amidoamine) copolymer. J. Control. Release 2008, 126, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, A.; Zagami, R.; Cordaro, A.; Pennisi, R.; Musarra-Pizzo, M.; Scala, A.; Sciortino, M.T.; Mazzaglia, A. Exploring the entrapment of antiviral agents in hyaluronic acid-cyclodextrin conjugates. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. 2019, 93, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytovene. Available online: https://www.rxlist.com/cytovene-drug.htm (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Benjamin, E.J.; Firestone, B.A.; Bergstrom, R.; Fass, M.; Massey, I.; Tsina, I.; Lin, Y.Y.T. Selection of a derivative of the antiviral agent 9-[1,3(dihydroxy)-2-(propoxy)-methyl]guanine (DHPG) with improved oral absorption. Pharm. Res. 1987, 4, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganciclovir Sodium. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/salts/DBSALT000309 (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Janoly-Dumenil, A.; Rouvet, I.; Bleyzac, N.; Morfin, F.; Zabot, M.T.; Tode, M.A. Pharmacodynamic model of ganciclovir antiviral effect and toxicity for lymphoblastoid cells suggests a new dosing regimen to treat cytomegalovirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3732–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolazzi, C.; Abdou, S.; Collomb, J.; Marsura, A.; Finance, C. Effect of the complexation with cyclodextrins on the in vitro antiviral activity of ganciclovir against human cytomegalovirus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001, 9, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolazzi, C.; Venard, V.; Le Faou, A.; Finance, C. In vitro antiviral efficacy of the ganciclovir complexed with β-cyclodextrin on human cytomegalovirus clinical strains. Antivir. Res. 2002, 54, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirucherai, G.S.; Mitra, A.K. Effect of hydroxypropyl beta cyclodextrin complexation on aqueous solubility, stability, and corneal permeation of acyl ester prodrugs of ganciclovir. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2003, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.S.; Lysenko, K.; El-Saleh, F.; Almeida Paz, F.A. Cyclodextrin-efavirenz complexes investigated by solid state and solubility studies. Proceedings 2021, 78, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofoletti, R.; Nair, A.; Abrahamsson, B.; Groot, D.W.; Koop, S.; Langguth, P.; Polli, J.E.; Shah, V.P.; Dressman, J. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Efavirenz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 102, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathigari, S.; Chadha, G.; Lee, Y.H.P.; Wright, N.; Parsons, D.L.; Rangari, V.K.; Fasina, O.; Babu, R.J. Physicochemical characterization of efavirenz-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2009, 10, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shown, I.; Banerjee, S.; Ramchandran, A.V.; Geckeler, K.E.; Murthy, C.N. Synthesis of cyclodextrin and sugar-based oligomers for the efavirenz drug delivery. Macromol. Symp. 2010, 287, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.S.; El-Saleh, F.; Lysenko, K.; Paz, F.A.A. Inclusion compound of efavirenz and γ-cyclodextrin: Solid state studies and effect on solubility. Molecules 2021, 26, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A.C.C.; Ferreira Fontes, D.A.; Chaves, L.L.; Alves, L.D.S.; de Freitas Neto, J.L.; de la Roca Soares, M.F.; Soares-Sobrinho, J.L.; Rolim, L.A.; Rolim-Neto, P.J. Multicomponent systems with cyclodextrins and hydrophilic polymers for the delivery of efavirenz. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 130, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, K.P.R.; Naresh, A. Formulation development of efavirenz tablets employing β cyclodextrin-PVP K30-SLS: A factorial study. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.R.P.; Chaudhari, J.; Trotta, F.; Caldera, F. Investigation of cyclodextrin-based nanosponges for solubility and bioavailability enhancement of rilpivirine. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2018, 19, 2358–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Public Assessment Report for Rilpivirine. Available online: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-rilpivirine-120327.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Srivani, S.; Kumar, Y.A.; Rao, N.G.R. Enhancement of solubility of rilpivirine by inclusion complexation with cyclodextrins. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Drug Res. 2018, 10, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, R.; Zaheer, Z.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Momin, M. Enhancement of oral bioavailability of anti-HIV drug rilpivirine HCl through nanosponge formulation. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2017, 43, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Khoo, S.H.; Back, D.J. The intracellular pharmacology of antiretroviral protease inhibitors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, C.M.; Buchanan, N.L.; Edgar, K.J.; Little, J.L.; Ramsey, M.G.; Ruble, K.M.; Wacher, V.J.; Wempe, M.F. Pharmacokinetics of saquinavir after intravenous and oral dosing of saquinavir: Hydroxybutenyl-β-cyclodextrin formulations. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.M.; Musmade, P.; Dengle, S.; Karthik, A.; Bhat, K.; Udupa, N. Enhanced oral absorption of saquinavir with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin—Preparation and in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 41, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branham, M.L.; Moyo, T.; Govender, T. Preparation and solid-state characterization of ball milled saquinavir mesylate for solubility enhancement. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 80, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudad, H.; Legrand, P.; Lebas, G.; Cheron, M.; Duchêne, D.; Ponchel, G. Combined hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and poly(alkylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles intended for oral administration of saquinavir. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 218, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, H.S.; Pingale, M.H.; Agrawal, K.M. Solubility and dissolution enhancement of saquinavir mesylate by inclusion complexation technique. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2013, 76, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérard, A.; Romani, S.; Fresse, A.; Viard, D.; Parassol, N.; Granvuillemin, A.; Chouchana, L.; Rocher, F.; Drici, M.D. French Network of Pharmacovigilance Centers. “Off-label” use of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, lopinavir-ritonavir and chloroquine in COVID-19: A survey of cardiac adverse drug reactions by the French Network of Pharmacovigilance Centers. Therapies 2020, 75, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, G.; Vavia, P.R. Complexation approach for fixed dose tablet formulation of lopinavir and ritonavir: An anomalous relationship between stability constant, dissolution rate and saturation solubility. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2012, 73, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Ishizuka, N.; Mohri, K.; Fukushima, M.; Ohba, C.; Kawakami, K. Enhanced boosting of oral absorption of lopinavir through electrospray coencapsulation with ritonavir. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 2977–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Domingo, P.; Galindo, M.J.; Milinkovic, A.; Arroyo, J.A.; Baldoví, F.; Larrousse, M.; León, A.; de Lazzari, E.; Gatell, J.M. Risk of metabolic abnormalities in patients infected with HIV receiving antiretroviral therapy that contains Lopinavir-Ritonavir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, O.; Conceição, J.; Serra, P.A.; da Silva, A.B.; Duarte, N.; Guedes, R.C.; Corvo, M.C.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A.; Jicsinszky, L.; Casimiro, T.; et al. Cyclodextrin solubilization and complexation of antiretroviral drug lopinavir: In silico prediction; Effects of derivatization, molar ratio and preparation method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 227, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oo, C.; Snell, P.; Barret, J.; Dorr, A.; Liu, B.; Wilding, I. Pharmacokinetics and delivery of the anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir to the small intestine and colon using site-specific delivery capsules. Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 257, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molecule of the Week: Oseltamivir Phosphate. Americal Chemical Society. 12 February 2018. Available online: https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/molecule-of-the-week/archive/o/oseltamivir-phosphate.html (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Sevukarajan, M.; Bachala, T.; Nair, R. Novel inclusion complexs of oseltamivir phosphate-with β cyclodextrin: Physico-chemical characterization. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Improved Oseltamivir Phosphate Medicinal Composition. Chinese Patent CN102068425A, 25 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grein, J.; Ohmagari, N.; Shin, D.; Diaz, G.; Asperges, E.; Castagna, A.; Feldt, T.; Green, G.; Green, M.L.; Lescure, F.-X.; et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—Final Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Summary on Compassionate Use—Remdesivir Gilead. Procedure No. EMEA/H/K/005622/CU. 3 April 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/summary-compassionate-use-remdesivir-gilead_en.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Emergency Use Authorization for Potential COVID-19 Treatment. FDA News; 1 May 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-issues-emergency-use-authorization-potential-covid-19-treatment (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Food and Drug Administration. Remdesivir Prescribing Information. Drugsdata at FDA; October 2020. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/214787Orig1s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Pipkin, J.; Antle, V.; García-Fondiño, R. Application of Captisol® Technology to Enable the Formulation of Remdesivir in Treating COVID-19. Drug Dev. Deliv. 2020, 20, 42–50. Available online: https://drug-dev.com/formulation-forum-application-of-captisol-technology-to-enable-the-formulation-of-remdesivir-in-treating-covid-19/ (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/janssen-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- EMA Recommends COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen for Authorisation in the EU. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-covid-19-vaccine-janssen-authorisation-eu (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Label: JANSSEN COVID-19 VACCINE—ad26.cov2.s Injection, Suspension. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=14a822ff-f353-49f9-a7f2-21424b201e3b (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Adriaansen, J.; Hesselink, R.W. Methods for Preventing Surface-Induced Degradation of Viruses Using Cyclodextrins. Canadian Patent CA3001050A1, 13 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, S.S. Cyclodextrins: Emerging medicines of the new millennium. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgers, L.A.T.; Lejeune, G.; Nicolas, I.; Fochesato, M.; Boon, B. Sulfolipo-cyclodextrin in squalane-in-water as a novel and safe vaccine adjuvant. Vaccine 1999, 17, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, S.A.; Hilgers, L.A.T.; Puntel, M.; Zamorano, P.I.; Alcon, V.L.; Santos, M.J.; Viera, J.B.; Borca, M.V.; Sadir, A.M. Adjuvant effects of sulfolipo-cyclodextrin in a squalane-in-water and water-in-mineral oil emulsions for BHV-1 vaccines in cattle. Vaccine 2001, 19, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Suvaxyn PCV Product Information. EMEA/V/C/000149-R/0028. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/veterinary/EPAR/suvaxyn-pcv#product-information-section (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Onishi, M.; Ozasa, K.; Kobiyama, K.; Ohata, K.; Kitano, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Homma, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Sato, A.; Katakai, Y.; et al. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin spikes local inflammation that induces Th2 cell and T follicular helper cell responses to the coadministered antigen. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Yun, C.H.; Han, S.H. Induction of dendritic cell maturation and activation by a potential adjuvant, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase 1 Study of Hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin(HP-beta-CyD)-Adjuvanted Influenza Split Vaccine. Available online: https://rctportal.niph.go.jp/en/detail?trial_id=UMIN000028530 (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Kusakabe, T.; Ozasa, K.; Kobari, S.; Momota, M.; Kishishita, N.; Kobiyama, K.; Kuroda, E.; Ishii, K.J. Intranasal hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin-adjuvanted influenza vaccine protects against sub-heterologous virus infection. Vaccine 2016, 34, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmuth, A.M.; Oberli, M.A.; Jaklenec, A.; Langer, R.; Blankschtein, D. mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Ther. Deliv. 2016, 7, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, J. Temperature concerns could slow the rollout of new coronavirus vaccines. Science 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/11/temperature-concerns-could-slow-rollout-new-coronavirus-vaccines (accessed on 12 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Haley, R.M.; Gottardi, R.; Langer, R.; Mitchell, M.J. Cyclodextrins in drug delivery: Applications in gene and combination therapy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zheng, T.; Li, M.; Zhong, X.; Tang, Y.; Qin, M.; Sun, X. Optimization of an mRNA vaccine assisted with cyclodextrin-polyethyleneimine conjugates. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.E.; Zuckerman, J.E.; Choi, C.H.J.; Seligson, D.; Tolcher, A.; Alabi, C.A.; Yen, Y.; Heidel, J.D.; Ribas, A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature 2010, 464, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanet, Orphan Designation—USA. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Drugs_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=88421&search=Drugs_Search_Simple&data_type=Status&Typ=Sub (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Orphan Designation EU/3/13/1124. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/orphan-designations/eu3131124 (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Zimmer, S.; Grebe, A.; Bakke, S.S.; Bode, N.; Halvorsen, B.; Ulas, T.; Skjelland, M.; De Nardo, D.; Labzin, L.I.; Kerksiek, A.; et al. Cyclodextrin promotes atherosclerosis regression via macrophage reprogramming. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 333ra50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, S.S.; Aune, M.H.; Niyonzima, N.; Pilely, K.; Ryan, L.; Skjelland, M.; Garred, P.; Aukrust, P.; Halvorsen, B.; Latz, E.; et al. Cyclodextrin reduces cholesterol crystal–induced inflammation by modulating complement activation. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 2910–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagne, D.; Fillet, M.; Delattre, L.; Evrard, B.; Nusgens, B.; Piel, B. Study of the cholesterol extraction capacity of β-cyclodextrin and its derivatives, relationships with their effects on endothelial cell viability and on membrane models. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2009, 63, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Nayak, D.P. Lipid raft disruption by cholesterol depletion enhances influenza A virus budding from MDCK cells. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12169–12178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Whittaker, G.R. Role for influenza virus envelope cholesterol in virus entry and infection. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12543–12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Gupta, D.; Lal, S.K. Host lipid rafts play a major role in binding and endocytosis of Influenza A virus. Viruses 2018, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Si, L.; Tian, Z.; Jiao, P.; Fan, Z.; Meng, K.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Han, X.; et al. Pentacyclic triterpenes grafted on CD cores to interfere with influenza virus entry: A dramatic multivalent effect. Biomaterials 2016, 78, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Si, L.; Meng, K.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Xiao, S. Inhibition of influenza virus infection by multivalent pentacyclic triterpene-functionalized per-O-methylated cyclodextrin conjugates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 134, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Lin, H.R.; Liao, C.L.; Lin, Y.L. Cholesterol effectively blocks entry of flavivirus. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6470–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta-Guardo, H.; Mosso, C.; Medina, F.; Liprandi, F.; Ludert, J.E.; del Angel, R.M. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection in U937 cells requires cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro, A.C.; Damonte, E.B. Requirement of cholesterol in the viral envelope for dengue virus infection. Virus Res. 2013, 174, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, A.C.; Hernández-Bravo, R.; Medina, F.; Coll, D.S.; Zambrano, J.L.; del Angel, R.M.; Ludert, J.E. The dengue virus non-structural protein 1 (NS1) is secreted from infected mosquito cells via a non-classical caveolin-1-dependent pathway. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2088–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.B.; Zou, Z.Y.; Hu, Z.H.; Fan, Q.S.; Xiong, J. Hepatitis C virus entry into macrophages/monocytes mainly depends on the phagocytosis of macrophages. Digest. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1226–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Saravanabalaji, D.; Yi, M. Detergent-resistant membrane association of NS2 and E2 during hepatitis C virus replication. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4562–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, Q.; Yu, F.; Peng, Y.Y.; Yang, M.; Sollogoub, M.; Sinaÿ, P.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, L.H.; Zhou, D.M. Conjugation of cyclodextrin with fullerene as a new class of HCV entry inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5616–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Graham, D.R.; Hildreth, J.E. Lipid rafts and HIV pathogenesis: Virion-associated cholesterol is required for fusion and infection of susceptible cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2003, 19, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.R.M.; Chertova, E.; Hilburn, J.M.; Arthur, L.O.; Hildreth, J.E.K. Cholesterol depletion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus with β-cyclodextrin inactivates and permeabilizes the virions: Evidence for virion-associated lipid rafts. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 8237–8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, K.V.; Whaley, K.J.; Zeitlin, L.; Moench, T.R.; Mehrazar, K.; Cone, R.A.; Liao, Z.; Hildreth, J.E.; Hoen, T.E.; Shultz, L.; et al. Vaginal transmission of cell-associated HIV-1 in the mouse is blocked by a topical, membrane-modifying agent. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, Z.; Compton, L.; Michael Piatak, M., Jr.; Lu, D.; Alvord, W.G.; Lubomirski, M.S.; Hildreth, J.E.K.; Lifson, J.D.; Miller, C.J.; KewalRamani, V.N. Incomplete protection against simian immunodeficiency virus vaginal transmission in rhesus macaques by a topical antiviral agent revealed by repeat challenges. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6591–6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senti, G.; Iannaccone, R.; Graf, N.; Felder, M.; Tay, F.; Kündig, T. A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to test the efficacy of topical 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin in the prophylaxis of recurrent herpes labialis. Dermatology 2013, 226, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.T.; Cagno, V.; Janeček, M.; Ortiz, D.; Gasilova, N.; Piret, J.; Gasbarri, M.; Constant, D.A.; Han, Y.; Vuković, L.; et al. Modified cyclodextrins as broad-spectrum antivirals. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacology Review 20-966. Sporanox (Itraconazole) Injection. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/20-966_SPORANOX%20INJECTION%2010MG%20PER%20ML_PHARMR.PDF (accessed on 12 February 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).