Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a para-retrovirus or retroid virus that contains a double-stranded DNA genome and replicates this DNA via reverse transcription of a RNA pregenome. Viral reverse transcription takes place within a capsid upon packaging of the RNA and the viral reverse transcriptase. A major characteristic of HBV replication is the selection of capsids containing the double-stranded DNA, but not those containing the RNA or the single-stranded DNA replication intermediate, for envelopment during virion secretion. The complete HBV virion particles thus contain an outer envelope, studded with viral envelope proteins, that encloses the capsid, which, in turn, encapsidates the double-stranded DNA genome. Furthermore, HBV morphogenesis is characterized by the release of subviral particles that are several orders of magnitude more abundant than the complete virions. One class of subviral particles are the classical surface antigen particles (Australian antigen) that contain only the viral envelope proteins, whereas the more recently discovered genome-free (empty) virions contain both the envelope and capsid but no genome. In addition, recent evidence suggests that low levels of RNA-containing particles may be released, after all. We will summarize what is currently known about how the complete and incomplete HBV particles are assembled. We will discuss briefly the functions of the subviral particles, which remain largely unknown. Finally, we will explore the utility of the subviral particles, particularly, the potential of empty virions and putative RNA virions as diagnostic markers and the potential of empty virons as a vaccine candidate.

Keywords:

hepatitis B virus; virion; empty virion; Australian antigen; HBsAg; HBcAg; subviral particles; CCC DNA; diagnosis; vaccine 1. Introduction

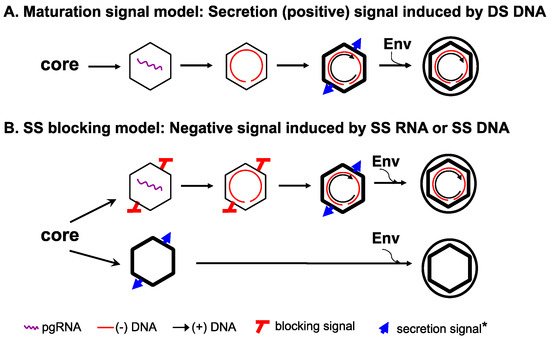

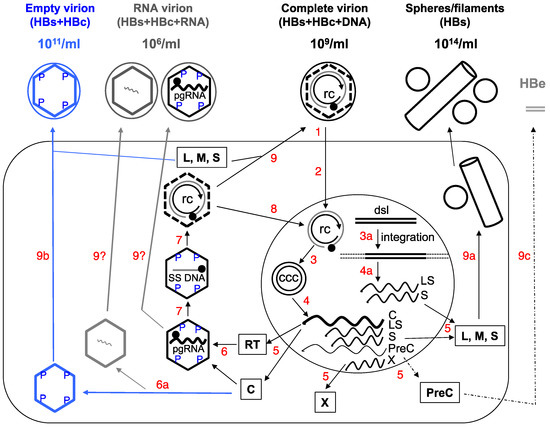

A major characteristic of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the secretion of large amounts of complete and incomplete viral particles. Assembly of the complete HBV virions, which are spheres 42 nm in diameter and routinely found in the blood of infected patients at 109/mL, begins with the packaging of the viral pregenomic RNA (pgRNA), as a complex with the viral reverse transcriptase (RT) protein, into an icosahedral capsid, 30 nm in diameter and composed of 240 copies of the viral capsid or core protein (HBc; also called HBV core antigen or HBcAg) (Figure 1). Within the capsid, RT first converts pgRNA to a single-stranded (SS) (minus-sense) DNA, and subsequently to a partially double-stranded (DS), relaxed circular DNA or RC DNA [1]. Somewhat used as a jargon, the capsid together with its interior RNA or DNA content is called a nucleocapsid or NC. NCs with pgRNA and SS DNA are considered immature as they are incompetent for envelopment and secretion as virions. In contrast, RC DNA-containing NCs are considered mature and are selected for envelopment by the viral envelope or surface proteins (also called HBV surface antigen or HBsAg) and secreted extracellularly as complete virions [2,3,4,5,6]. As a result, a complete HBV virion contains an outer envelope enclosing an inner capsid, which in turn encloses the RC DNA genome (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication cycle. 1. Virus binding and entry into the host cell (large rectangle). 2. Intracellular trafficking and delivery of relaxed circular (RC) DNA to the nucleus (large circle). 3. Conversion of RC DNA to CCC DNA, or integration of the double-stranded linear (DSL) DNA into host DNA (3a). 4. and 4a. Transcription to synthesize viral RNAs (wavy lines), including the C mRNA for both the core and RT proteins; LS mRNA for the L envelope protein; S mRNA for the M and S envelope proteins; X mRNA for the X protein; and PreC mRNA for the PreCore protein. The C mRNA is also the pgRNA. 5. Translation to synthesize viral proteins. 6. Assembly of the pgRNA- (and RT-) containing NC, or alternatively, empty capsids (6a). 7. Reverse transcription of pgRNA to synthesize the (−) strand SS DNA and then RC DNA. 8. Nuclear recycling of progeny RC DNA to form more CCC DNA (intracellular CCC DNA amplification). 9. Envelopment of the RC DNA-containing NC and secretion of complete virions, or alternatively, secretion of empty virions (9b) or HBsAg spheres and filaments (9a). Processing of the PreCore protein and secretion of HBeAg are depicted in 9c. The secretion of putative RNA virions is not yet resolved (9?). The different viral particles outside the cell are depicted schematically with their approximate concentrations in the blood of infected persons indicated: the complete, empty, or RNA virions as large circles (outer envelope) with an inner diamond shell (capsid), with or without RC DNA (unclosed, double concentric circle) or RNA (wavy line) inside the capsid respectively; HBsAg spheres and filament as small circles and a cylinder. It is important to point out that the concentrations of all these particles can vary widely between different patients and over time in the same patient. Intracellular capsids are depicted as diamonds, with either viral pgRNA, SS [(−) strand] DNA (straight line), RC DNA, or empty. The letters “P” denote phosphorylated residues on the immature NCs (containing SS DNA or pgRNA) or empty capsid. The dashed lines of the diamond in the RC DNA-containing mature NCs signify the destabilization of the mature NC, which is dephosphorylated. The empty capsids, like mature NCs, are also less stable compared to immature NCs but unlike mature NCs, are phosphorylated. The soluble, dimeric HBeAg is depicted as grey double bars. The thin dashed line and arrow denote the fact that HBeAg is frequently decreased or lost late in infection. Boxed letters denote the viral proteins translated from the mRNAs. The filled circle on RC DNA denotes the RT protein attached to the 5’ end of the (−) strand (outer circle) of RC DNA and the arrow denotes the 3’ end of the (+) strand (inner circle) of RC DNA. ccc, CCC DNA; rc, RC DNA. For simplicity, synthesis of the minor DSL form of the genomic DNA in the mature NC, its secretion in virions, and infection of DSL DNA-containing virions are not depicted here, as are the functions of X. See text for details. Modified from [2].

In contrast, incomplete or subviral particles of HBV, of which there are two known major types, are either missing both the genome and capsid or missing just the genome (Figure 1). The first type is the classical HBsAg spheres and filaments of 20 nm in diameter (HBsAg particles), historically also called Australian or Au antigen owing to its initial identification in an Australian aborigine. These subviral particles are composed of only the viral surface proteins and found in the blood of infected individuals at up to 100,000-fold in excess over the complete virions (at 1014/mL) [7]. The second class is the recently discovered empty (genome-free) virions, which contain the surface proteins enclosing the viral capsid but no genome and are typically found at 100-fold higher levels over complete virions in the blood of infected individuals (1011/mL) [8,9]. In addition, putative particles containing HBV RNA, at much lower levels than the other particles (100- to 1000-fold lower than complete virions) have also been reported recently (Figure 1) [10,11,12,13].

HBV-infected cells also secrete a soluble, dimeric protein antigen called hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) (Figure 1) [14]. HBeAg is processed from the so-called PreCore (PreC) protein and shares most of its amino acid residues with HBcAg but has an N-terminal extension of 10 amino acid residues (unique to the PreC region) and a C-terminal truncation of ca. 34 amino acid residues, relative to HBcAg. Independent of capsid assembly or viral replication, HBeAg is released through the host cell secretary pathway and may exert immunoregulatory effects [15]. Historically, serum HBeAg has been widely used to monitor viral infection and treatment response as it is usually associated with high levels of viral replication [15]. In line with the focus on HBV particles here, we will not discuss this soluble viral antigen anymore.

Secretion of all HBV particles and proteins, as well as viral replication, are ultimately directed by a viral episome, the covalently closed circular DNA (CCC DNA). CCC DNA is synthesized from RC DNA, which is released either from complete virions infecting from outside the cell or from intracellular mature NCs (via the so-called intracellular CCC DNA amplification pathway), in the nuclei of infected hepatocytes and serves as the sole viral transcriptional template able to direct the expression of all viral gene products and sustain viral replication (Figure 1) [1,16,17,18]. Ongoing efforts to develop a cure for chronic HBV infection ultimately are aimed at the elimination of CCC DNA (or stable silencing of its transcriptional activity). It is thought that CCC DNA is very stable and may persist in the absence of viral replication for as long as the infected cell survives [19,20,21]. Alternatively or additionally, new CCC DNA is likely being continuously produced in the infected liver, even during apparently effective antiviral therapy, from residual replicative viral DNA via the afore-mentioned intracellular amplification pathway whereby the end product of reverse transcription, RC DNA, is directed to the host cell nucleus to form more CCC DNA (instead of being secreted in virions), and perhaps also via de novo infection by residual complete virions. This is possible because inhibition of RC DNA synthesis is incomplete with current antiviral therapy, which targets only the DNA synthesis activity of RT [22,23]. Nevertheless, current treatment can lead to significant reduction or loss of CCC DNA in a minority of patients via a mechanism(s) that is yet to be elucidated but likely involves a combination of reduced CCC DNA formation (due to the depletion of RC DNA), loss of infected cells, and perhaps degradation of preexisting CCC DNA.

It has proven challenging to monitor intrahepatic CCC DNA level or its transcriptional activity either directly using infected liver tissues, or indirectly by measuring surrogate markers in the periphery (blood or serum) [2,24,25]. Detection of CCC DNA in liver biopsies may be the most direct way for this purpose. However, it is impractical to perform this invasive and risky procedure on a routine basis due to safety concerns. Also, as infection of the liver is likely to become increasingly heterogeneous during long-term infection and antiviral treatment due to loss or decrease of CCC DNA in some but not all infected hepatocytes, it is unclear whether liver biopsies, which can obtain only very small amounts of tissues, can faithfully reflect the infection status throughout the liver. Additionally, it remains technically challenging to specifically and accurately detect CCC DNA in clinical samples, which are usually contaminated with a large excess of RC DNA that is structurally related to CCC DNA (Figure 1) and difficult to discriminate from CCC DNA in PCR-based methods that are needed to detect the small amounts of CCC DNA [18]. As will be detailed later in this article, the various HBV particles released into the blood stream of infected patients have attracted increasing attention in recent years as convenient and accessible surrogate markers to monitor intrahepatic CCC DNA level and transcriptional activity.

Below, we will first summarize current understanding of the molecular processes that lead to the release of HBV virions and subviral particles. The potential role of these particles in viral replication and pathogenesis will also be briefly discussed. The emphasis will be on the recently discovered empty virions and potential RNA virions. We will then focus on the possible application of the various viral particles as convenient peripheral biomarkers to monitor viral activity in the infected liver, and the potential of empty virions as a candidate for a new generation of HBV vaccine.

4. Potential Applications of HBV Particles in Clinical Management

Historically, the abundance of subviral particles has proven very useful in both the diagnosis and management of HBV infections. As mentioned above, the classical Au antigen (i.e., HBsAg) heralded the identification of the virus itself [7]. Furthermore, since its discovery, the HBsAg particles have been used extensively as a convenient marker to monitor HBV infection, screening of blood supplies, and gauge response to antiviral treatment (see more below). Similarly, the Au antigen particles, harvested directly from pooled plasma of infected patients, formed the basis of the 1st generation of HBV vaccine, which has proven to be very safe and highly effective [7]. As will be discussed below, empty virions, and possibly RNA virions, may also prove to be valuable as diagnostic markers and perhaps, as a new vaccine candidate.

4.1. Diagnostics

The long-standing and wide-spread use of complete virions (clinically measured as viremia or viral DNA load in the blood) and HBsAg particles for diagnostic purposes have been reviewed recently [24,25,67,68], and will not be discussed in detail here. It is important to emphasize, however, that recent efforts to use quantitative measurements of serum HBsAg, and the soluble HBeAg, as surrogate markers to monitor the intrahepatic CCC DNA, the basis of HBV infection and persistence, have revealed each of these has major limitations. In the case of HBsAg, it is well known that it can be expressed from integrated HBV DNA (Figure 1), which accumulates over time (by at least 10- to 100-fold) [68,69,70,71,72] and could be the predominant source of serum HBsAg (instead of CCC DNA). Integrated HBV DNA is derived predominantly from the minor form of viral DNA, DSL (Figure 1) [69,73] in which the PreCore/Core gene is disrupted but the HBsAg gene is maintained [74,75]. This likely explains the loss of correlation between serum HBsAg levels and hepatic CCC DNA, especially in the late stage of HBV infection [76,77,78]. Another issue that can affect the accuracy of HBsAg quantification is the frequent mutations in the envelope gene, some of which are induced by current antiviral treatment targeted at the RT protein whose coding sequences overlap with the envelope gene (Figure 1) [68,79]. On the other hand, expression of HBeAg (like that of HBcAg) is unlikely to be directed from integrated HBV DNA, due to the disruption of the PreCore/core gene, and could, in principle, be a good surrogate for hepatic CCC DNA (Figure 1). However, HBeAg can be decreased or lost entirely due to frequent mutations in the core promoter or the PreC region, as discussed recently [2,9]. In addition, viremia (HBV DNA or complete virions in the blood) is routinely suppressed to very low or undetectable levels (despite the persistence of CCC DNA in the liver) following current antiviral therapy, rendering complete virions useless as a marker to monitor CCC DNA persistence in this situation. Thus, there is increasing realization that better markers are needed to monitor HBV infection, particularly the hepatic CCC DNA. As discussed below, empty virions, and perhaps RNA virions, have the potential to serve as better surrogate markers for hepatic CCC DNA.

4.1.1. Serum Empty Virions (HBcAg) as a Marker for Hepatic CCC DNA

Since the production of empty virions is uncoupled from viral DNA replication but requires the expression of both HBcAg and HBsAg, they can in principle serve as an effective biomarker for transcriptionally active CCC DNA during current antiviral therapy with RT inhibitors, which, as mentioned above, can reduce serum HBV DNA (i.e., complete virions) to undetectable levels but has no direct effect on CCC DNA level or its transcriptional activity [78,80]. As mentioned above, a minority of the treated patients do experience significant decreases in hepatic CCC DNA with current antiviral therapy, presumably due to host-mediated elimination of infected cells or CCC DNA and the therapy-induced elimination of the CCC DNA precursor (i.e., RC DNA) and consequently, diminished replenishment of the CCC DNA pool [78,81,82,83]. In a pilot study to evaluate the potential of serum empty virions as a surrogate biomarker for hepatic CCC DNA, we determined serum levels of empty virions, using a relatively insensitive western blot assay (with a detection limit of ca. 50 ng/mL), together with viral DNA (complete virions) and HBsAg levels, in a small group of patients who underwent treatment with the RT inhibitor tenofovir [9]. Levels of serum empty virions can be monitored conveniently by measuring serum HBcAg levels, as the amount of HBcAg in complete virions contributes to less than 1% of the total serum HBcAg (i.e., from both complete and empty virions).

Before tenofovir treatment, serum empty virions were present at levels up to 1011/mL and at more than 50- to 100,000-fold excess compared to RC DNA-containing virions [9], consistent with our earlier observations in HBV-infected chimpanzees and in the supernatants of HBV-replicating hepatoma cells [8]. Following the antiviral therapy, the secretion of complete virions decreased dramatically (by ca. 107/mL or more) in virtually all patients, as expected. However, secretion of empty virions was not decreased in most cases even after years of potent HBV DNA suppression. This is, of course, exactly as predicted given that DNA synthesis is required for secretion of complete virions, but completely dispensable for empty virion secretion, which would continue unabated unless the hepatic CCC DNA is eliminated or stably silenced. Significant reductions in, and possibly complete loss of, serum empty virions were in fact observed in a minority of treated patients, including those who achieved HBsAg loss. The results suggest that these patients might indeed have experienced significant reductions or loss in hepatic CCC DNA levels (or CCC DNA transcriptional activity) after the therapy, although the unavailability of the corresponding liver tissues unfortunately precluded a direct measurement of hepatic CCC DNA in these patients. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more sensitive HBcAg assay format, together with direct measurements of corresponding hepatic CCC DNA levels, will be needed to further assess the usefulness of serum empty virions as a surrogate marker for hepatic CCC DNA and to determine the potential diagnostic and prognostic significance of serum empty virions. As the HBc sequence is known to be more variable in some regions than in the others [84], epitopes will have to be carefully considered for antibody-based assays to detect serum HBcAg (i.e., empty virions).

Interestingly, attempts were made over two-decade ago to measure serum HBc, before the realization of empty virion secretion. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was developed to measure serum HBcAg, using an antibody specific for the HBc CTD, which indeed showed a good correlation between serum HBc and HBV DNA in untreated patients, and furthermore, the decrease of serum HBc was much less than that of serum HBV DNA during treatment with an RT inhibitor (lamivudine in this case) in the single patient who was monitored [85]. These results led the authors to speculate the secretion of DNA-free virions although they didn't provide any other supporting evidence. In the meantime, a different ELISA kit was developed to measure the so-called HBcrAg in serum samples, which has been used in a number of clinical studies as a putative surrogate in attempt to monitor hepatic CCC DNA.

It is important to point out that some confusions exist in the literature as to what “HBcrAg” is exactly. Initially, in 2002, an ELISA kit was reported for the detection of both the soluble HBeAg and HBcAg that was released from virions in serum samples, using antibodies targeted to the sequences shared by both HBc and HBe [86]. A few years later, an aberrant HBeAg and HBcAg related protein, the so-called p22cr (with an even longer N-terminal extension than HBe and missing the CTD of HBc; see above), was claimed to be present in DNA-free HBV virions in serum samples from HBV infected individuals. This aberrant protein was also named HBcrAg. In the literature, the term “HBcrAg” has been used to describe a combination of HBc and HBe [13,86,87,88]; the supposedly aberrant p22cr [47]; and a combination of all three entities, HBc, HBe, and p22cr [89,90,91]. As discussed above, the so-called p22cr probably does not really exist and the current HBcrAg ELISA kit most likely detects a combination of HBcAg (released from virions) and HBeAg. Thus, with HBeAg present, the HBcrAg kit detects both serum empty virions and HBeAg but in the absence of HBeAg, it essentially detects empty virions (again with the contribution of serum HBcAg from complete virions being negligible).

Not surprisingly, serum HBcrAg levels were found to correlate relatively well with serum HBV DNA and HBsAg levels, to decrease in HBeAg (−) phase, and to decrease much slower than serum HBV DNA and remains detectable in serum HBV DNA (−) patients upon nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) treatment [13,88,90], as we observed for serum empty virions [9]. Furthermore, serum HBcrAg levels were correlated with CCC DNA levels and frequency of HBcAg (+) hepatocytes in the liver and with liver disease activity [87,89,92,93]. It was also found to predict liver cancer development and recurrence in HBV-infected patients, and was an even better predictor than serum HBV DNA [92,94]. Serum HBcrAg was also found to associate with reactivation of occult hepatitis B following immunosuppressive therapy [91].

As discussed above, serum HBeAg levels may not strictly correlate with hepatic CCC DNA levels or its transcriptional activity, due to the frequent mutations in the PreC region and core promoter. Therefore, measurement of both serum HBeAg and HBcAg, by using the HBcrAg assay, may not entirely reflect functional CCC DNA in the liver, since CCC DNA defective in HBeAg expression can nevertheless still express HBcAg and the other viral proteins and sustain HBV persistence. Given the aberrant “p22cr” or “HBcrAg” is most likely an artifact, as discussed above, it will be advantageous to measure exclusively serum HBcAg (i.e., empty virions), without the variable contribution of HBeAg. Moreover, as mentioned above, the ratio of empty vs. complete virions in different patients varies widely. Among other factors, this ratio may reflect the efficiency of intrahepatic assembly of empty vs. pgRNA-containing capsids, which, together with the efficiency of reverse transcription and virion assembly and secretion, ultimately determine the ratio of empty vs. complete virions in the blood (Figure 1). Thus, measurement of both complete and empty virions in the blood can also help monitor these events in the liver, which could reflect the changing viral activities, host physiology, and virus-host interactions.

4.1.2. Serum HBV RNA

As mentioned earlier, there has been a lot of interest recently to use serum HBV RNA as a surrogate to monitor hepatic HBV CCC DNA. In principle, release of RNA-containing virions would be independent of viral DNA synthesis and could reflect expression of pgRNA, its packaging into immature NCs and subsequent envelopment and secretion. Due to the ease and sensitivity in RNA detection and quantification, as compared to HBcAg (empty virions), serum HBV RNA could thus be a convenient marker to monitor intrahepatic CCC DNA, when viral DNA synthesis is effectively suppressed with antiviral therapy [12]. Consistent with this expectation, various reports have shown that serum HBV RNA levels decreased much less and slower than serum HBV DNA during therapy with RT inhibitors [11,13,59,60]. A quick RNA decrease early during therapy with RT inhibition may predict viral clearance [60], and conversely, the persistence of serum HBV RNA after RT inhibition was associated with a risk of viral rebound after discontinuation of treatment [10]. It was also reported that interferon treatment could induce a more significant decrease in serum HBV RNA than RT inhibitors [57,59], presumably due to the inhibitory effect of interferon, but not RT inhibitors, on the levels of HBV RNA in the hepatocytes.

As discussed above, it is important to more clearly define both the nature of the viral RNA as well as the particles/vesicles that harbor the RNA in the blood, in order to more reliably and accurately interpret the meaning of serum HBV RNA levels in terms of viral gene expression and replication, and response to therapy. If the serum HBV RNA indeed represents immature virions (i.e., enveloped immature NCs containing pgRNA (and RT)), it could reflect hepatic CCC DNA levels. However, the reported detection of truncated HBV RNAs in the serum samples, which was likely transcribed from integrated HBV DNA and might be released to the blood in the absence of any other viral markers, may instead reflect release of non-functional viral RNAs in some sort of vesicles in the absence of either capsid or virion assembly. If this turns out to be true, serum HBV RNA levels obviously would not reflect hepatic CCC DNA level or its transcriptional activity. In addition, therapeutics designed to block pgRNA packaging into NCs [66], currently under active development, would lead to a loss of serum HBV RNA-containing virions despite CCC DNA persistence in the liver. In this case, measurement of serum empty virions (HBcAg), not the putative RNA virions, would help monitor hepatic CCC DNA levels.

In summary, quantitative and sensitive measurement of serum HBcAg (empty virions), and possibly, HBV RNA, in combination with the classical serum viral markers (HBV DNA, HBsAg, HBeAg), have the potential to provide a more accurate view of hepatic CCC DNA level and its transcriptional activity, and thus help monitor viral persistence and response to antiviral treatment. In particular, the decision of when to stop antiviral therapy remains an important issue in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B [22,95]. It was recently estimated that it may require life-long treatment (average 52 years) with current antiviral therapy, even in the absence of drug resistance, to clear HBsAg [96], the current “gold standard” for a cure of chronic HBV infection. However, this may be an overly pessimistic view, and indeed the use of HBsAg loss may be an overly stringent criterion for a cure - at least for direct acting antivirals, if the remaining serum HBsAg is produced exclusively from integrated HBV DNA following the loss of hepatic CCC DNA and does not have a major pathological consequence. In such a scenario, a significant decline and loss of serum HBcAg may signify CCC DNA clearance (or stable silencing) in the liver, which could help guide the safe discontinuation of therapy. For these individuals, continued treatment to block viral replication or induce CCC DNA loss is unlikely to be beneficial. If a complete loss of HBsAg is still desired in this situation [97], alternative treatment strategies targeted at the integrated HBV DNA would be required.

4.2. Empty Virions as a Candidate for a New Generation of HBV Vaccine?

The empty virions may also form the basis for a new generation of HBV vaccine. As mentioned above, the 1st generation of HBV vaccine was derived directly from plasma of infected patients and would have contained HBsAg particles, empty virions, and complete virions (inactivated). Due to theoretic safety concerns with the use of human plasma, this highly effective vaccine was replaced by the current recombinant (2nd generation) HBV vaccine that contains only one of the HBV envelope protein, S, and no capsid protein. Though it has proven to be safe and effective in most cases, the recombinant S vaccine fails to induce a sufficient response in some vaccinees [98]. Also, as the recombinant vaccine elicits predominantly an antibody response targeted at a single common epitope, the so-called “a” determinant in S, HBV can evolve mutations in this epitope to escape the vaccine-induced antibodies [98,99,100]. To potentially exacerbate the vaccine escape problem further, RT inhibitors, the most widely used treatment for chronic HBV infection, have been shown to select vaccine escape mutants as well as drug-resistant mutants. As alluded to above, due to the overlap of the RT and envelope genes, certain drug resistant mutations in the RT gene also encode vaccine-escape S proteins in the overlapping S gene [79,101,102]. A potential 3rd generation HBV vaccine could be based on empty virions, which would contain all of the viral structural proteins but no genome. In principle, such a vaccine should be as safe as the current generation of vaccine but may help overcome the limitations of the current vaccine by providing additional antigenic determinants (and possibly better mimics of complete virions) for both humoral and cellular immune responses, the latter of which target dominantly the internal capsid protein [98]. Thus, an empty virion-based vaccine may prove to be effective for therapeutic as well as prophylactic purposes.

5. Summary

The discovery of the classical Au antigen (HBsAg spheres and filaments) half a century ago proved instrumental in the identification of HBV that predated the discovery of both the complete, infectious virions as well as the viral genetic material. These incomplete, non-infectious, subviral particles also formed the basis for the subsequent development of highly efficacious measures (vaccines and biomarkers) to prevent and manage this deadly viral infection. The more recent identification and characterization of the genome-free (empty) HBV virions, and of potentially RNA-containing HBV virions, challenge long-standing dogmas in the field regarding HBV assembly and present interesting questions about the biological functions of these particles. Further studies on the incomplete HBV particles, as well as the complete virions, should not only deepen our understanding of HBV replication and morphogenesis and but will also likely bring about useful and timely tools (novel markers and vaccine candidates) to facilitate current efforts to develop a cure for HBV infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank all colleagues for their work that is referenced here and apologize to those whose work cannot be cited due to space constraint. Work in the authors’ laboratory has been supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants to J.H. (AI043453, AI074982, and AI077532) from the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions

J.H. and K.L. conceived and designed the experiments described in this review; K.L. performed the experiments described in this review; J.H. and K.L. analyzed the data; J.H and K.L. wrote this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hu, J.; Seeger, C. Hepadnavirus genome replication and persistence. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a021386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J. Hepatitis B virus virology and replication. In Hepatitis B Virus in Human Diseases; Liaw, Y.-F., Zoulim, F., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gerelsaikhan, T.; Tavis, J.E.; Bruss, V. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid envelopment does not occur without genomic DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4269–4274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.; Mason, W.S. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B--like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell 1982, 29, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D.; Hu, J. Duck hepatitis B virus virion secretion requires a double-stranded DNA genome. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, C.; Hu, J. Why are hepadnaviruses DNA and not RNA viruses? Trends Microbiol. 1997, 5, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, B.S. Australia antigen and the biology of hepatitis B. Science 1977, 197, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Nguyen, D.; Mentzer, L.; Adams, C.; Lee, H.; Ashley, R.; Hafenstein, S.; Hu, J. Secretion of genome-free hepatitis B virus--single strand blocking model for virion morphogenesis of para-retrovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckenbaugh, L.; Kitrinos, K.M.; Delaney, W.E.T.; Hu, J. Genome-free hepatitis B virion levels in patient sera as a potential marker to monitor response to antiviral therapy. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 22, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shen, T.; Huang, X.; Kumar, G.R.; Chen, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Chen, R.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; et al. Serum hepatitis B virus RNA is encapsidated pregenome RNA that may be associated with persistence of viral infection and rebound. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bommel, F.; Bartens, A.; Mysickova, A.; Hofmann, J.; Kruger, D.H.; Berg, T.; Edelmann, A. Serum hepatitis B virus RNA levels as an early predictor of hepatitis B envelope antigen seroconversion during treatment with polymerase inhibitors. Hepatology 2015, 61, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.W.; Chayama, K.; Kao, J.H.; Yang, S.S. Detectability and clinical significance of serum hepatitis B virus ribonucleic acid. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2015, 4, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rokuhara, A.; Matsumoto, A.; Tanaka, E.; Umemura, T.; Yoshizawa, K.; Kimura, T.; Maki, N.; Kiyosawa, K. Hepatitis B virus RNA is measurable in serum and can be a new marker for monitoring lamivudine therapy. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 41, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMattia, M.A.; Watts, N.R.; Stahl, S.J.; Grimes, J.M.; Steven, A.C.; Stuart, D.I.; Wingfield, P.T. Antigenic switching of hepatitis B virus by alternative dimerization of the capsid protein. Structure 2013, 21, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milich, D.; Liang, T.J. Exploring the biological basis of hepatitis B e antigen in hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 2003, 38, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttleman, J.S.; Pourcel, C.; Summers, J. Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell 1986, 47, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Hu, J. Formation of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA: Removal of genome-linked protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 6164–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassal, M. Hbv cccdna: Viral persistence reservoir and key obstacle for a cure of chronic hepatitis B. Gut 2015, 64, 1972–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokosuka, O.; Omata, M.; Imazeki, F.; Okuda, K. Active and inactive replication of hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid in chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology 1985, 89, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaiche, G.Y.; Le Mire, M.F.; Mason, W.S.; Jilbert, A.R. The persistence in the liver of residual duck hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA is not dependent upon new viral DNA synthesis. Virology 2010, 406, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, C.; Litwin, S.; Mason, W.S. Hepatitis B virus: Persistence and clearance. In Hepatitis B Virus Virology and Replication; Liaw, Y.-F., Zoulim, F., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Revill, P.; Locarnini, S. The basis for antiviral therapy: Drug targets, cross-resistance, and novel small molecule inhibitors. In Hepatitis B Virus in Human Diseases; Liaw, Y.-F., Zoulim, F., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016; pp. 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.N.; Hu, J. Hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase–target of current antiviral therapy and future drug development. Antivir. Res. 2015, 123, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu Siederdissen, C.H.; Cornberg, M.; Manns, M.P. Clinical virology: Diagnosis and virological monitoring. In Hepatitis B Virus in Human Diseases; Liaw, Y.-F., Zoulim, F., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.C.; Kao, J.H. Looking into the crystal ball: Biomarkers for outcomes of HBV infection. Hepatol. Int. 2016, 10, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heermann, K.H.; Goldmann, U.; Schwartz, W.; Seyffarth, T.; Baumgarten, H.; Gerlich, W.H. Large surface proteins of hepatitis B virus containing the pre-s sequence. J. Virol. 1984, 52, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Sorensen, E.M.; Naito, A.; Schott, M.; Kim, S.; Ahlquist, P. Involvement of host cellular multivesicular body functions in hepatitis B virus budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10205–10210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Himmelsbach, K.; Ren, H.; Boller, K.; Hildt, E. Subviral hepatitis B virus filaments, like infectious viral particles, are released via multivesicular bodies. J. Virol. 2015, 90, 3330–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Tavis, J.E.; Ganem, D. Relationship between viral DNA synthesis and virion envelopment in hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 6455–6458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lambert, C.; Doring, T.; Prange, R. Hepatitis B virus maturation is sensitive to functional inhibition of ESCRT-III, Vps4, and gamma 2-adaptin. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9050–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruss, V.; Ganem, D. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruss, V.; Thomssen, R. Mapping a region of the large envelope protein required for hepatitis B virion maturation. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruss, V. A short linear sequence in the pre-S domain of the large hepatitis B virus envelope protein required for virion formation. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 9350–9357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.H.; Tran, C.T.; Robinson, W.S. Hepatitis B virus particles of plasma and liver contain viral DNA-RNA hybrid molecules. Virology 1984, 139, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schormann, W.; Kraft, A.; Ponsel, D.; Bruss, V. Hepatitis B virus particle formation in the absence of pregenomic RNA and reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4187–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, D.H.; Berg, E.A.; O'Connor, P.B.; Costello, C.E.; Hu, J. Reverse transcription-associated dephosphorylation of hepadnavirus nucleocapsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9020–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseman, A.M.; Berriman, J.A.; Wynne, S.A.; Butler, P.J.; Crowther, R.A. A structural model for maturation of the hepatitis B virus core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15821–15826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschel, M.; Oed, D.; Gerelsaikhan, T.; Thomssen, R.; Bruss, V. Hepatitis B virus core gene mutations which block nucleocapsid envelopment. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pairan, A.; Bruss, V. Functional surfaces of the hepatitis B virus capsid. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 11616–11623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsel, D.; Bruss, V. Mapping of amino acid side chains on the surface of hepatitis B virus capsids required for envelopment and virion formation. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Ludgate, L.; Ning, X.; Hu, J. Maturation-associated destabilization of hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 11494–11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basagoudanavar, S.H.; Perlman, D.H.; Hu, J. Regulation of hepadnavirus reverse transcription by dynamic nucleocapsid phosphorylation. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, X.; Basagoudanavar, S.H.; Liu, K.; Luckenbaugh, L.; Wei, D.; Wang, C.; Wei, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, T.; Delaney, W.; et al. Capsid phosphorylation state and hepadnavirus virion secretion. J. Virol. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerin, J.L.; Ford, E.C.; Purcell, R.H. Biochemical characterization of australia antigen. Evidence for defective particles of hepatitis B virus. Am. J. Pathol. 1975, 81, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, P.M.; Ford, E.C.; Purcell, R.H.; Gerin, J.L. Demonstration of subpopulations of dane particles. J. Virol. 1976, 17, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Yamada, G.; Mizuno, M.; Nishihara, T.; Kinoyama, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nagashima, H. Full and empty particles of hepatitis B virus in hepatocytes from patients with HBsAG-positive chronic active hepatitis. Lab Investig. 1983, 48, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Ohno, N.; Terada, N.; Rokuhara, A.; Matsumoto, A.; Yagi, S.; Tanaka, E.; Kiyosawa, K.; Ohno, S.; Maki, N. Hepatitis B virus DNA-negative dane particles lack core protein but contain a 22-kDa precore protein without C-terminal arginine-rich domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 21713–21719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Gummuluru, S.; Hu, J. Deamination-independent inhibition of hepatitis B virus reverse transcription by APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4465–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludgate, L.; Liu, K.; Luckenbaugh, L.; Streck, N.; Eng, S.; Voitenleitner, C.; Delaney, W.E.T.; Hu, J. Cell-free hepatitis B virus capsid assembly dependent on the core protein C-terminal domain and regulated by phosphorylation. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5830–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilditch, C.M.; Rogers, L.J.; Bishop, D.H. Physicochemical analysis of the hepatitis B virus core antigen produced by a baculovirus expression vector. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 2755–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanford, R.E.; Notvall, L. Expression of hepatitis B virus core and precore antigens in insect cells and characterization of a core-associated kinase activity. Virology 1990, 176, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, M.A.; Pillot, J. HBc and HBe antigenicity and DNA-binding activity of major core protein p22 in hepatitis b virus core particles isolated from the cytoplasm of human liver cells. J. Virol. 1985, 53, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gallina, A.; Bonelli, F.; Zentilin, L.; Rindi, G.; Muttini, M.; Milanesi, G. A recombinant hepatitis B core antigen polypeptide with the protamine-like domain deleted self assembles into capsid particles but fails to bind nucleic acids. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4645–4652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, P.; Stahl, S.; Williams, R.; Steven, A. Hepatitis core antigen produced in Escherichia coli: Subunit composition, conformational analysis, and in vitro capsid assembly. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4919–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatton, T.; Zhou, S.; Standring, D. Rna- and DNA-binding activities in hepatitis B virus capsid protein: A model for their role in viral replication. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 5232–5241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Machida, A.; Tsuda, O.; Yoshikawa, A.; Hoshi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kishimoto, S.; Akahane, Y.; Miyakawa, Y.; Mayumi, M. Phosphorylation in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the capsid protein of hepatitis B virus: Evaluation with a monoclonal antibody. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 6024–6030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jansen, L.; Kootstra, N.A.; van Dort, K.A.; Takkenberg, R.B.; Reesink, H.W.; Zaaijer, H.L. Hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA is present in virions in plasma and is associated with a response to pegylated interferon Alfa-2a and nucleos(t)ide analogues. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Wang, S.F.; Chang, T.E.; Breitkreutz, R.; Hennig, H.; Takegoshi, K.; Edler, L.; Schroder, C.H. Circulating hepatitis B virus nucleic acids in chronic infection: Representation of differently polyadenylated viral transcripts during progression to nonreplicative stages. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.W.; Chayama, K.; Tsuge, M.; Takahashi, S.; Hatakeyama, T.; Abe, H.; Hu, J.T.; Liu, C.J.; Lai, M.Y.; Chen, D.S.; et al. Differential effects of interferon and lamivudine on serum HBV RNA inhibition in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Ther. 2010, 15, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.W.; Takahashi, S.; Tsuge, M.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, T.C.; Abe, H.; Hu, J.T.; Chen, D.S.; Yang, S.S.; Chayama, K.; et al. On-treatment low serum HBV RNA level predicts initial virological response in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving nucleoside analogue therapy. Antivir. Ther. 2015, 20, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, T.T.; Sahu, G.K.; Whitehead, W.E.; Greenberg, R.; Shih, C. The mechanism of an immature secretion phenotype of a highly frequent naturally occurring missense mutation at codon 97 of human hepatitis B virus core antigen. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 5731–5740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.F.; Netter, H.J.; Bruns, M.; Schneider, R.; Frolich, K.; Will, H. A new avian hepadnavirus infecting snow geese (Anser caerulescens) produces a significant fraction of virions containing single-stranded DNA. Virology 1999, 262, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, N.; Hayes, M.H.; Loeb, D.D. Snow goose hepatitis B virus (SGHBV) envelope and capsid proteins independently contribute to the ability of SGHBV to package capsids containing single-stranded DNA in virions. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10705–10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tencza, M.G.; Newbold, J.E. Heterogeneous response for a mammalian hepadnavirus infection to acyclovir: Drug-arrested intermediates of minus-strand viral DNA synthesis are enveloped and secreted from infected cells as virion-like particles. J. Med. Virol. 1997, 51, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, M.K.; Gehring, A.J. The role of innate immunity in the immunopathology and treatment of HBV infection. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, S60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, A.; Venkatakrishnan, B.; Tan, Z.; Lewellyn, E.; Turner, W.; Francis, S. Core protein: A pleiotropic keystone in the HBV lifecycle. Antivir. Res. 2015, 121, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allain, J.P.; Opare-Sem, O. Screening and diagnosis of HBV in low-income and middle-income countries. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornberg, M.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Locarnini, S.; Brunetto, M.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Chan, H.L.-Y. The role of quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen revisited. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Summers, J. Integration of hepadnavirus DNA in infected liver: Evidence for a linear precursor. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 9710–9717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.; Mason, W.S. Residual integrated viral DNA after hepadnavirus clearance by nucleoside analog therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Nguyen, D. Therapy for chronic hepatitis B: The earlier, the better? Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, W.S.; Gill, U.S.; Litwin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Peri, S.; Pop, O.; Hong, M.L.; Naik, S.; Quaglia, A.; Bertoletti, A.; et al. HBV DNA integration and clonal hepatocyte expansion in chronic hepatitis B patients considered immune tolerant. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 986–998.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staprans, S.; Loeb, D.D.; Ganem, D. Mutations affecting hepadnavirus plus-strand DNA synthesis dissociate primer cleavage from translocation and reveal the origin of linear viral DNA. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacNab, G.M.; Alexander, J.J.; Lecatsas, G.; Bey, E.M.; Urbanowicz, J.M. Hepatitis B surface antigen produced by a human hepatoma cell line. Br. J. Cancer 1976, 34, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, B.B.; Howe, C.C.; Aden, D.P. Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines secrete the major plasma proteins and hepatitis B surface antigen. Science 1980, 209, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Nguyen, T.; Iser, D.; Ayres, A.; Jackson, K.; Littlejohn, M.; Slavin, J.; Bowden, S.; Gane, E.J.; Abbott, W.; et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers: Disease phase influences correlation with viral load and intrahepatic hepatitis B virus markers. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1933–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.C.; Kao, J.H. Clinical utility of quantitative HBsAG in natural history and nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment of chronic hepatitis B: New trick of old dog. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoulim, F.; Testoni, B.; Lebosse, F. Kinetics of intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA and serum hepatitis B surface antigen during antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B: Lessons from experimental and clinical studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 1011–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torresi, J. The virological and clinical significance of mutations in the overlapping envelope and polymerase genes of hepatitis B virus. J. Clin. Virol. 2002, 25, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.T.; Pryce, M.; Wang, X.; Barrasa, M.I.; Hu, J.; Seeger, C. Conditional replication of duck hepatitis B virus in hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonno, R.J.; Genovesi, E.V.; Medina, I.; Lamb, L.; Durham, S.K.; Huang, M.L.; Corey, L.; Littlejohn, M.; Locarnini, S.; Tennant, B.C.; et al. Long-term entecavir treatment results in sustained antiviral efficacy and prolonged life span in the woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 184, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Cullen, J.; Saputelli, J.; Aldrich, C.E.; Miller, D.S.; Litwin, S.; Furman, P.A.; Jilbert, A.R.; Mason, W.S. Kinetics of hepadnavirus loss from the liver during inhibition of viral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werle-Lapostolle, B.; Bowden, S.; Locarnini, S.; Wursthorn, K.; Petersen, J.; Lau, G.; Trepo, C.; Marcellin, P.; Goodman, Z.; Delaney, W.E.T.; et al. Persistence of CCCDNA during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and decline during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chain, B.M.; Myers, R. Variability and conservation in hepatitis B virus core protein. BMC Microbiol. 2005, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Rokuhara, A.; Matsumoto, A.; Yagi, S.; Tanaka, E.; Kiyosawa, K.; Maki, N. New enzyme immunoassay for detection of hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBcAG) and relation between levels of HBcAG and HBV DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Rokuhara, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Yagi, S.; Tanaka, E.; Kiyosawa, K.; Maki, N. Sensitive enzyme immunoassay for hepatitis B virus core-related antigens and their correlation to virus load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.K.; Tanaka, Y.; Lai, C.L.; Mizokami, M.; Fung, J.; Yuen, M.F. Hepatitis B virus core-related antigens as markers for monitoring chronic hepatitis B infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 3942–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, E.; Matsumoto, A.; Yoshizawa, K.; Maki, N. Hepatitis B core-related antigen assay is useful for monitoring the antiviral effects of nucleoside analogue therapy. Intervirology 2008, 51, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, F.; Miyakoshi, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumada, H. Correlation between serum hepatitis B virus core-related antigen and intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA in chronic hepatitis B patients. J. Med. Virol. 2009, 81, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maasoumy, B.; Wiegand, S.B.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Bremer, B.; Lehmann, P.; Deterding, K.; Taranta, A.; Manns, M.P.; Wedemeyer, H.; Glebe, D.; et al. Hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAG) levels in the natural history of hepatitis B virus infection in a large european cohort predominantly infected with genotypes A and D. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 606.e1–606.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seto, W.K.; Wong, D.H.; Chan, T.Y.; Hwang, Y.Y.; Fung, J.; Liu, K.S.; Gill, H.; Lam, Y.F.; Cheung, K.S.; Lie, A.K.; et al. Association of hepatitis B core-related antigen with hepatitis B virus reactivation in occult viral carriers undergoing high-risk immunosuppressive therapy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 1788–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosaka, T.; Suzuki, F.; Kobayashi, M.; Hirakawa, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Yatsuji, H.; Sezaki, H.; Akuta, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Saitoh, S.; et al. HbcrAG is a predictor of post-treatment recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma during antiviral therapy. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, T.; Tatsuki, I.; Otani, M.; Akiyama, M.; Ozawa, E.; Miuma, S.; Miyaaki, H.; Taura, N.; Hayashi, T.; Okudaira, S.; et al. Significance of hepatitis B virus core-related antigen and covalently closed circular DNA levels as markers of hepatitis B virus re-infection after liver transplantation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, T.; Kumada, T.; Toyoda, H.; Kiriyama, S.; Tanikawa, M.; Hisanaga, Y.; Kanamori, A.; Kitabatake, S.; Yama, T.; Tanaka, J. HBcrAG predicts hepatocellular carcinoma development: An analysis using time-dependent receiver operating characteristics. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, S.J.; Lok, A.S. Effectiveness of hepatitis B treatment in clinical practice. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1360–1368.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevaliez, S.; Hezode, C.; Bahrami, S.; Grare, M.; Pawlotsky, J.M. Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAG) kinetics during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy: Finite treatment duration unlikely. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.C.; Liu, C.J.; Yang, H.C.; Su, T.H.; Wang, C.C.; Chen, C.L.; Kuo, S.F.; Liu, C.H.; Chen, P.J.; Chen, D.S.; et al. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low hbv load. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1140–1149.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoletti, A.; Ferrari, C. Adaptive immunity in HBV infection. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, S71–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carman, W.F.; Zanetti, A.R.; Karayiannis, P.; Waters, J.; Manzillo, G.; Tanzi, E.; Zuckerman, A.J.; Thomas, H.C. Vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. Lancet 1990, 336, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.W.; Lin, T.Y.; Tsao, K.C.; Huang, C.G.; Hsiao, M.J.; Liang, K.H.; Yeh, C.T. Increased seroprevalence of HBV DNA with mutations in the S gene among individuals greater than 18 years old after complete vaccination. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamili, S.; Sozzi, V.; Thompson, G.; Campbell, K.; Walker, C.M.; Locarnini, S.; Krawczynski, K. Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine against antiviral drug-resistant hepatitis B virus mutants in the chimpanzee model. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacombe, K.; Boyd, A.; Lavocat, F.; Pichoud, C.; Gozlan, J.; Miailhes, P.; Lascoux-Combe, C.; Vernet, G.; Girard, P.M.; Zoulim, F. High incidence of treatment-induced and vaccine-escape hepatitis B virus mutants among human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B-infected patients. Hepatology 2013, 58, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).