Abstract

The Hepadnaviridae family of small, enveloped DNA viruses are characterized by a strict host range and hepatocyte tropism. The prototype hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major human pathogen and constitutes a public health problem, especially in high-incidence areas. Reporter-expressing recombinant viruses are powerful tools in both studies of basic virology and development of antiviral therapeutics. In addition, the highly restricted tropism of HBV for human hepatocytes makes it an ideal tool for hepatocyte-targeting in vivo applications such as liver-specific gene delivery. However, compact genome organization and complex replication mechanisms of hepadnaviruses have made it difficult to engineer replication-competent recombinant viruses that express biologically-relevant cargo genes. This review analyzes difficulties associated with recombinant hepadnavirus vector development, summarizes and compares the progress made in this field both historically and recently, and discusses future perspectives regarding both vector design and application.

1. Introduction

Hepadnaviridae is a family of small, enveloped DNA viruses with notable hepatic tropism, especially in mammals, and transmission is achieved predominantly through parenteral routes [1,2]. The viral genome consists of partially double-stranded, relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) that is produced through a process involving a reverse transcription step similar to retroviruses [2,3]. These features led to the classification of hepadnaviruses under group VII (dsDNA(RT) or pararetrovirus) in the Baltimore system, along with certain similar DNA viruses infecting plants.

Hepadnaviruses usually have highly-restricted host ranges and have traditionally been classified into two genera based on host specificity [4,5]. Orthohepadnaviruses infect mammals, with members including the prototype hepatitis B virus (HBV) of humans, woolly monkey hepatitis B virus (WMHBV), woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV), and ground squirrel hepatitis virus (GSHV), etc. Avihepadnaviruses infect various domesticated and wild birds, with members including the prototype duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV), as well as heron hepatitis B virus (HHBV), etc. In recent years, the advent and advances of next-generation sequencing and other metagenomics technologies have enabled the discovery of new HBV-like viruses that infect hosts previously not known to be affected by hepadnaviruses, such as bats [6] and fish [7]. In addition, analyses of whole genome sequencing data have also led to the discovery of endogenous hepadnaviral sequences in genomes of avian [8,9,10] and reptilian [11] species, suggesting a family history spanning millions of years. In light of these recent discoveries, hepadnaviruses, including extant and now extinct ones, are obviously far more diverse than previously understood and the taxonomy may well be expanded and modified in the future.

Among extant hepadnaviruses, orthohepadnaviruses productively infect only hepatocytes of the liver, whereas DHBV has been shown to additionally infect certain other cell types of the liver and non-liver organs [3]. Hepato-tropism has been considered the result of tissue-specific distribution of both receptor(s) required for viral entry and transcription factors required for viral expression [12,13]. Accordingly, liver pathologies including hepatitis are major manifestations of symptomatic hepadnaviral infections in both human and animals [1,3]. However, as hepadnavirus infection is neither cytopathic nor cytolytic, hepatitis is generally considered a consequence of the activated host immune response against infected hepatocytes.

HBV is a major human pathogen and constitutes a severe public health problem in high-incidence areas [5,14]. HBV infection of adults is usually asymptomatic or manifests as self-resolving acute hepatitis, while a small percentage of patients fail to clear the virus and become infected for life. Vertical transmission of HBV from infected mothers to neonates typically results in asymptomatic chronic infection accompanied by immunotolerance towards HBV, which would be broken in later life leading to active hepatitis. Chronic HBV infection is associated with higher risks of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. Although extensive adoption of preventive HBV vaccine has drastically reduced incidence of new infections, the World Health Organization estimated that HBV chronically infects ~240 million people worldwide and causes about 600,000 related deaths annually [14].

Duck/DHBV and woodchuck/WHV have been used as model systems of HBV infections for decades, and have helped significantly in understanding hepadnavirus virology and developing anti-HBV therapeutics [15]. However, chronic DHBV infection is not associated with liver cirrhosis or HCC in ducks, while WHV-related HCC is mechanistically much more homogenous than HBV-associated human HCC [3], underlining the fact that HBV and human or humanized animal systems are required for studying various important aspects of HBV pathogenesis.

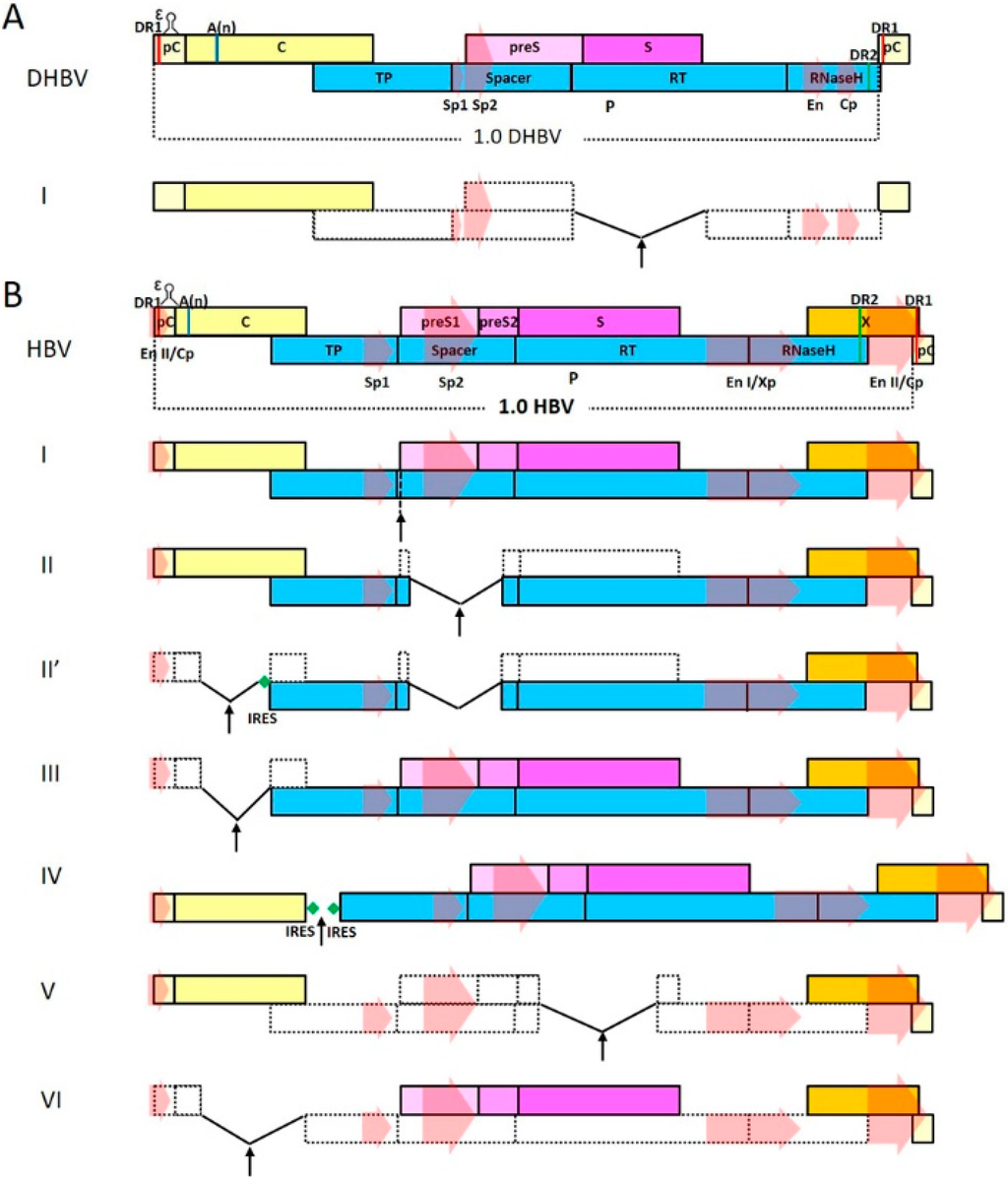

Reverse genetic systems were established for HBV as well as DHBV decades ago and have become standard tools in studies of viral functions as well as virus-host interactions. In contrast, owing to certain characteristics in genome organization and life cycle (see next section), development of reporter-expressing virus systems based on hepadnaviruses has met with far less successes than many other virus families. Nevertheless, recombinant hepadnavirus vector systems could serve as powerful tools for both studying fundamental questions in hepadnavirus virology and evaluating clinical interventions for chronic HBV infection, as have been demonstrated by other recombinant virus systems. In addition, the highly restricted host range and hepato-tropism of HBV makes it a uniquely ideal tool for hepatocyte-targeting applications, such as liver-specific therapeutic gene delivery. This review attempts to summarize difficulties associated with recombinant hepadnavirus vector development and progress made historically and recently, and discuss future perspectives in this field regarding both vector design and application.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Project for Infectious Diseases of China (2012ZX10002-006, 2012ZX10004-503, 2012ZX10002012-003), National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB519002), National High-Tech Program of China (2012AA02A407), Natural Science Foundation of China (31071143, 31170148), Shanghai Municipal R&D Program (11DZ2291900, GWDTR201216), and MingDao Project of Fudan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liang, T.J. Hepatitis B: The virus and disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, C.; Mason, W.S. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, C.; Mason, W.S. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology 2015, 479, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlejohn, M.; Locarnini, S.; Yuen, L. Origins and evolution of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLachlan, J.H.; Cowie, B.C. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, J.F.; Geipel, A.; Konig, A.; Corman, V.M.; van Riel, D.; Leijten, L.M.; Bremer, C.M.; Rasche, A.; Cottontail, V.M.; Maganga, G.D.; et al. Bats carry pathogenic hepadnaviruses antigenically related to hepatitis B virus and capable of infecting human hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16151–16156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, C.M.; Iwanowicz, L.R.; Cornman, R.S.; Conway, C.M.; Winton, J.R.; Blazer, V.S. Characterization of a novel hepadnavirus in the White Sucker (Catostomus commersonii) from the Great Lakes Region of the United States. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11801–11811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, A.; Brosius, J.; Schmitz, J.; Kriegs, J.O. The genome of a Mesozoic paleovirus reveals the evolution of hepatitis B viruses. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Pan, S.; Yang, H.; Bai, W.; Shen, Z.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y. The first full-length endogenous hepadnaviruses: Identification and analysis. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9510–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, C.; Feschotte, C. Genomic fossils calibrate the long-term evolution of hepadnaviruses. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, C.; Meik, J.M.; Dashevsky, D.; Card, D.C.; Castoe, T.A.; Schaack, S. Endogenous hepadnaviruses, bornaviruses and circoviruses in snakes. Proc. R. Soc. London B Bio. Sci. 2014, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watashi, K.; Wakita, T. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus entry, species specificity, and tissue tropism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winer, B.Y.; Ploss, A. Determinants of hepatitis B and delta virus host tropism. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 13, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Hepatitis B. World Health Organization Fact Sheet 204 (Revised July 2013). Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ (accessed on 10 December 2013).

- Mason, W.S. Animal models and the molecular biology of hepadnavirus infection. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.M.; Seeger, C. Hepadnavirus genome replication and persistence. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protzer, U.; Nassal, M.; Chiang, P.W.; Kirschfink, M.; Schaller, H. Interferon gene transfer by a hepatitis B virus vector efficiently suppresses wild-type virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10818–10823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.C.; Jeng, K.S.; Hu, C.P.; Chang, C. Effects of genomic length on translocation of hepatitis B virus polymerase-linked oligomer. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 9010–9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartenschlager, R.; Schaller, H. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3413–3420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feitelson, M.A.; Bonamassa, B.; Arzumanyan, A. The roles of hepatitis B virus-encoded X protein in virus replication and the pathogenesis of chronic liver disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2014, 18, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belloni, L.; Pollicino, T.; de Nicola, F.; Guerrieri, F.; Raffa, G.; Fanciulli, M.; Raimondo, G.; Levrero, M. Nuclear HBx binds the HBV minichromosome and modifies the epigenetic regulation of cccDNA function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19975–19979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucifora, J.; Arzberger, S.; Durantel, D.; Belloni, L.; Strubin, M.; Levrero, M.; Zoulim, F.; Hantz, O.; Protzer, U. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential to initiate and maintain virus replication after infection. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuge, M.; Hiraga, N.; Akiyama, R.; Tanaka, S.; Matsushita, M.; Mitsui, F.; Abe, H.; Kitamura, S.; Hatakeyama, T.; Kimura, T.; et al. HBx protein is indispensable for development of viraemia in human hepatocyte chimeric mice. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1854–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thung, S.N.; Gerber, M.A.; Purcell, R.H.; London, W.T.; Mihalik, K.B.; Popper, H. Animal model of human disease. Chimpanzee carriers of hepatitis B virus. Chimpanzee hepatitis B carriers. Am. J. Pathol. 1981, 105, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dandri, M.; Burda, M.R.; Zuckerman, D.M.; Wursthorn, K.; Matschl, U.; Pollok, J.M.; Rogiers, X.; Gocht, A.; Kock, J.; Blum, H.E.; et al. Chronic infection with hepatitis B viruses and antiviral drug evaluation in uPA mice after liver repopulation with tupaia hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 2005, 42, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandri, M.; Burda, M.R.; Torok, E.; Pollok, J.M.; Iwanska, A.; Sommer, G.; Rogiers, X.; Rogler, C.E.; Gupta, S.; Will, H.; et al. Repopulation of mouse liver with human hepatocytes and in vivo infection with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 2001, 33, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, J.; Nassal, M.; MacNelly, S.; Baumert, T.F.; Blum, H.E.; von Weizsacker, F. Efficient infection of primary tupaia hepatocytes with purified human and woolly monkey hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 5084–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gripon, P.; Rumin, S.; Urban, S.; le Seyec, J.; Glaise, D.; Cannie, I.; Guyomard, C.; Lucas, J.; Trepo, C.; Guguen-Guillouzo, C. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15655–15660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Zhong, G.; Xu, G.; He, W.; Jing, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. eLife 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.J.; Hirsch, R.C.; Ganem, D.; Varmus, H.E. Effects of insertional and point mutations on the functions of the duck hepatitis B virus polymerase. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 5553–5558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaisomchit, S.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Chang, L.J. Development of replicative and nonreplicative hepatitis B virus vectors. Gene Ther. 1997, 4, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Kaneko, S.; Honda, M.; Kobayashi, K. Approach to establishing a liver targeting gene therapeutic vector using naturally occurring defective hepatitis B viruses devoid of immunogenic T cell epitope. Virus Res. 2002, 85, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Rho, J.; Lee, D.; Shin, S.; Jung, G. Hepatitis B virus vector carries a foreign gene into liver cells in vitro. Virus Genes 2002, 24, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Mancini-Bourgine, M.; Zhang, X.; Cumont, M.C.; Zhu, R.; Lone, Y.C.; Michel, M.L. Hepatitis B virus as a gene delivery vector activating foreign antigenic T cell response that abrogates viral expression in mouse models. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, K.; Bai, W.; Jia, B.; Hu, H.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Y.; Bourgine, M.M.; et al. Adenoviral delivery of recombinant hepatitis B virus expressing foreign antigenic epitopes for immunotherapy of persistent viral infection. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3004–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Cheng, X.; Liu, S.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Kang, F.; Wang, J.; Xia, H.; Ping, C.; et al. Replication-competent infectious hepatitis B virus vectors carrying substantially sized transgenes by redesigned viral polymerase translation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, R.; Bai, W.; Zhai, J.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Zhao, X.; Ye, X.; Deng, Q.; et al. Novel recombinant hepatitis B virus vectors efficiently deliver protein and RNA encoding genes into primary hepatocytes. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6615–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untergasser, A.; Protzer, U. Hepatitis B virus-based vectors allow the elimination of viral gene expression and the insertion of foreign promoters. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004, 15, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Kang, F.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Cao, Z.; Nassal, M.; et al. Truncated active human matrix metalloproteinase-8 delivered by a chimeric adenovirus-hepatitis B virus vector ameliorates rat liver cirrhosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishitsuji, H.; Ujino, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Harada, K.; Zhang, J.; Sugiyama, M.; Mizokami, M.; Shimotohno, K. Novel reporter system to monitor early stages of the hepatitis B virus life cycle. Cancer Sci. 2015, 106, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Kao, Y.F.; Brown, C.M. Translation of the first upstream ORF in the hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA modulates translation at the core and polymerase initiation codons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).