Abstract

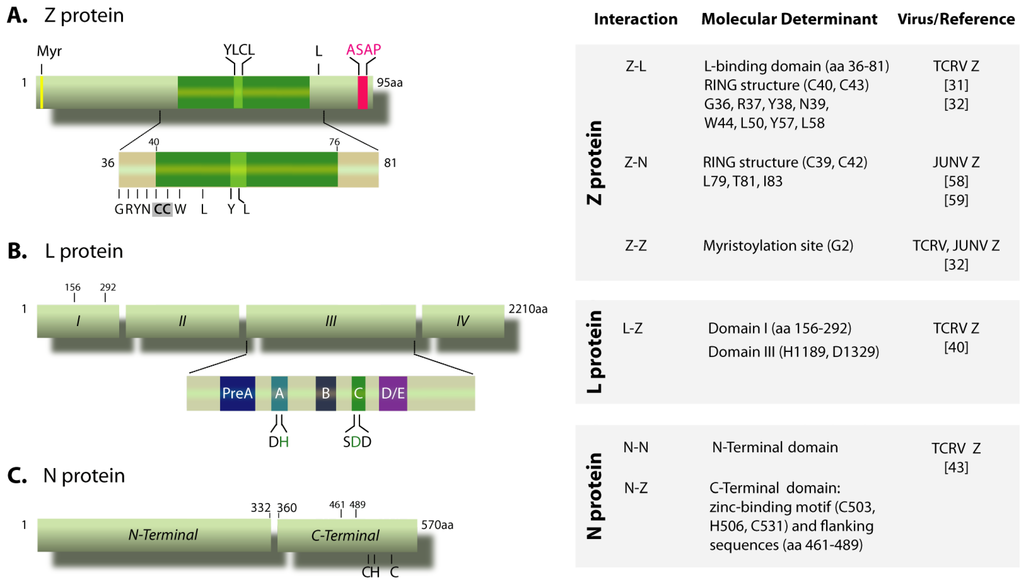

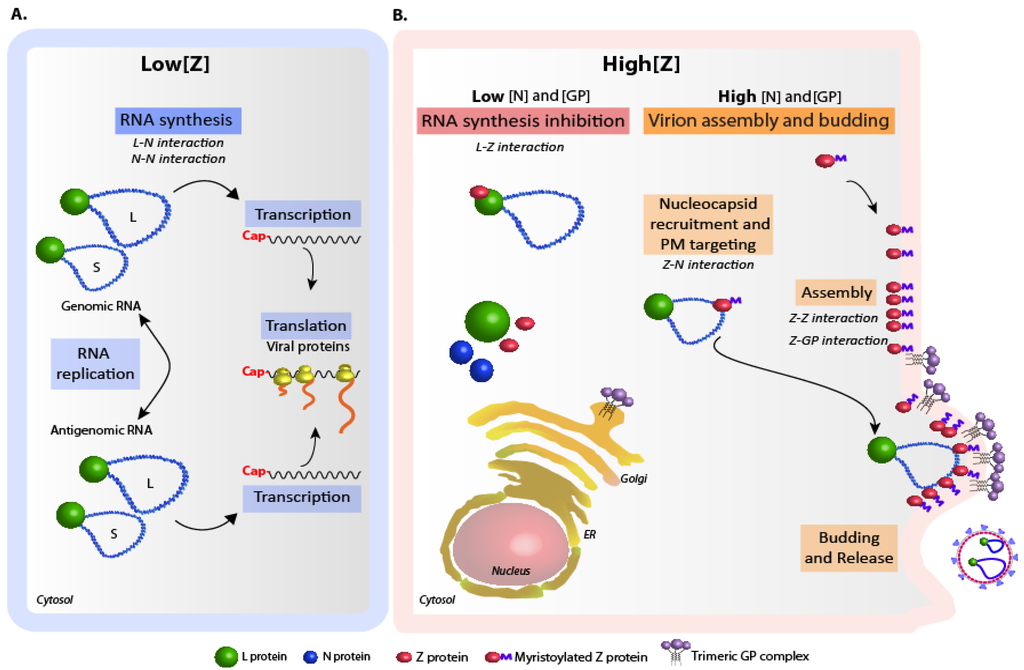

The Arenaviridae family includes widely distributed pathogens that cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans. Replication and packaging of their single-stranded RNA genome involve RNA recognition by viral proteins and a number of key protein-protein interactions. Viral RNA synthesis is directed by the virus-encoded RNA dependent-RNA polymerase (L protein) and requires viral RNA encapsidation by the Nucleoprotein. In addition to the role that the interaction between L and the Nucleoprotein may have in the replication process, polymerase activity appears to be modulated by the association between L and the small multifunctional Z protein. Z is also a structural component of the virions that plays an essential role in viral morphogenesis. Indeed, interaction of the Z protein with the Nucleoprotein is critical for genome packaging. Furthermore, current evidence suggests that binding between Z and the viral envelope glycoprotein complex is required for virion infectivity, and that Z homo-oligomerization is an essential step for particle assembly and budding. Efforts to understand the molecular basis of arenavirus life cycle have revealed important details on these viral protein-protein interactions that will be reviewed in this article.

1. Introduction

Arenaviruses are phylogenetically divided into the Old World (OW) and the New World (NW) groups, both of which include human pathogens associated with hemorrhagic fever, an often fatal disease [1,2]. Representative of the OW group are Lassa fever virus (LASV), which causes a high number of hemorrhagic fever cases in West Africa, and the worldwide-distributed Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV), a causative agent of aseptic meningitis. The NW group is comprised of all known South American pathogens that produce severe hemorrhagic disease: Junin (JUNV), associated with a major health problem in rural areas of Argentina, Machupo (MACV), Chapare, Guanarito, and Sabia viruses. This group also includes the prototypic, non-pathogenic Tacaribe virus (TCRV) [3]. TCRV is genetically and antigenically closely related to JUNV [3,4] and has been largely used as experimental model in our studies on NW arenavirus molecular genetics.

TCRV, like all arenaviruses, is an enveloped virus whose genome consists of two single-stranded, negative-sense RNA segments named S and L. Two genes, arranged in opposite orientation and separated by a non-coding intergenic region, are comprised in each genomic segment. The S RNA encodes the Nucleoprotein (N, 64 kDa) and the glycoprotein precursor (GPC, ca. 70 kDa). The L segment encodes the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L protein, 240 kDa) and a small protein called Z (11 kDa) [5]. The coding sequences are expressed from subgenomic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) transcribed from the 3´ regions of the genomes and antigenomes. These mRNAs are non-encapsidated and non-polyadenylated at their 3’ ends. Their 5’ ends contain short stretches of additional bases that are capped, which suggests that arenaviruses (like influenza viruses and bunyaviruses) may use a “cap-snatching” mechanism to initiate mRNA synthesis [5,6,7]. Mapping of the 3’ ends of TCRV mRNAs within the corresponding RNA intergenic region, along with our studies on the requirements for viral mRNA synthesis indicate that transcription termination is associated with sequence-independent signals located within the intergenic regions. These signals consist of -at least- a stable single hairpin structure that is not required for a correct initiation of transcription or replication [8,9].

In addition to the intergenic region, all arenaviruses genomic segments contain 5’ and 3’ terminal non-coding sequences that display inverted complementarity and are predicted to form panhandle structures, which harbor the promoter signals for viral RNAs synthesis [10,11,12].

3. Viral protein-protein interactions in particle assembly

3.1. Z-N interaction is important for nucleocapsid packaging

Studies on the OW LASV and LCMV first indicated that Z protein, which is a structural component of the virions, is the main force driving the cell surface budding of arenavirus particles [51,52,53]. Both the integrity of Late domains (PTAP and/or PPPY) at the C-terminus of the protein, which mediate the recruitment of specific cellular proteins of the ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport) that assist in budding, and Z protein myristoylation at the conserved glycine residue at position 2 (G2), were shown to be important for Z-mediated budding [52,53,54,55,56]. These findings, along with earlier demonstration that, after chemical crosslinking, Z and N proteins form a complex in purified LCMV particles [51], and that LASV Z and N proteins interact with each other when overexpressed in mammalian cells [57], prompted the idea that Z-N interaction might be implicated in virion assembly.

In order to investigate the contribution of viral protein-protein interactions to NW arenavirus morphogenesis, we developed a reverse genetic system able to drive TCRV-like nucleocapsids packaging along with Z and GP from JUNV into infectious chimeric virus-like particles (VLPs) [58]. As reported for OW arenavirus Zs, our studies indicated that upon solitary expression in mammalian cells, JUNV Z displays the ability to drive assembly and budding of Z-containing VLPs (self-budding activity), and that JUNV Z-mediated VLP production requires both the amino acid G2, and the integrity of the PTAP Late motif. Moreover, by dissecting the VLP system, we showed that JUNV Z is sufficient to recruit TCRV N protein into Z-induced particles that are surrounded by a lipid envelope, supporting the notion that Z-N interaction could facilitate the incorporation of nucleocapsids into budding particles [58].

Functional analysis of JUNV Z mutants in the VLP system led us to demonstrate that an intact RING structure and amino acid L79, which is strictly conserved across arenaviruses, are molecular determinants essential for JUNV Z to direct infectious chimeric VLP formation. These elements are also critical for the recruitment of N into Z-containing VLPs, whereas they are unnecessary for Z self-budding activity. Furthermore, both the L79 residue and the RING structure are required for intracellular Z-N interaction to occur. These results indicated that Z-N interactions are involved in infectious chimeric VLP assembly, strongly supporting that Z-N binding may contribute to the localization of viral nucleocapsids to the sites of budding at the plasma membrane and their subsequent packaging into arenavirus particles [58]. Further mutagenesis studies and VLP assays showed that highly conserved residues located in the vicinity of L79 outside the RING domain of JUNV Z protein (T81 and I83), may also participate in Z-N interaction [59]. In agreement, both amino acid L71 (equivalent to L79 in JUNV Z) and its neighboring residues in the C-terminal domain of LASV Z protein were shown to be critical for VLP infectivity, thus representing potential contacts with the viral nucleocapsid [60].

TCRV Z protein displays bona fide budding activity, despite containing a non-canonical (ASAP) Late domain [61]. The ability of TCRV Z to direct VLP production was reported to be enhanced upon coexpression with TCRV N protein [62], yet the underlying mechanism is unknown and no evidence of this effect has been described for any other arenavirus. As shown for JUNV Z, TCRV Z can also drive the incorporation of TCRV N into VLPs, in the absence of other viral proteins. A highly conserved YLCL motif located within the Z RING domain (Figure 1A), was found to be involved in TCRV N incorporation into TCRV Z-directed VLPs [62]. Similar results were observed for the OW Mopeia virus Z protein, whose YLCL motif was implicated in the interaction with the ESCRT-associated ALIX/AIP1 protein, proposed to link N and Z proteins during assembly [63]. Remarkably, the YLCL motif is also essential for TCRV Z to bind L [32], suggesting that Z-N and Z-L associations may be mutually exclusive.

Efforts to further characterize the N-Z interaction led our group to identify the C-terminal domain of TCRV N protein, spanning residues 360 to 570 (Figure 1C), as being required for the N-Z interaction and the recruitment of N into Z-induced VLPs [43]. Both the integrity of a conserved zinc binding motif and its flanking sequences were essential for this domain to be functional [43]. The involvement of the C-terminal half of N in its interaction with Z has also been reported for LCMV and Mopeia virus [64,65]. In the case of the latter, a region within this domain was also implicated in the interaction with the ALIX/AIP1 protein [63]. The observation that LCMV N and LASV Z cross-interacted, whereas LASV N and LCMV Z did not, suggests that species-specific residues -yet undetermined- within the C-terminal domain of N contribute to Z binding [64]. Overall, these results support the idea that the Z-N interaction -either direct or mediated by cellular protein(s)- plays an important role in viral assembly by promoting the plasma membrane targeting of the viral nucleocapsids.

3.2. GP-Z interaction

The arenavirus GPC is expressed as a single precursor polypeptide that is cleaved by cellular proteases to generate three subunits: the receptor-binding G1 protein, the transmembrane fusion subunit (G2) and a stable signal peptide SSP. Both the peripheral G1 and the SSP remain non-covalently associated with G2 forming the mature glycoprotein complex (GP), which assembles into trimers constituting the spikes on the virion envelope (reviewed in [66]).

Binding to the matrix protein has been implicated in the recruitment of glycoprotein spikes into particles of other enveloped viruses [67,68]. Similarly, current evidence suggests that the incorporation of viral glycoproteins during arenavirus assembly requires interaction (either direct or indirect) with Z. Indeed, experimental data showed intracellular association between the Z and GP proteins from either LCMV or LASV, and that this interaction requires Z protein myristoylation [69], which is known to facilitate Z binding to cellular membranes [55,56]. In addition, pulldown experiments demonstrated that LASV GP and Z proteins interact with each other within VLPs released from GP- and Z-expressing cells [70]. In the case of JUNV proteins, evidence of GP incorporation into Z-induced VLPs has also been documented, further supporting the relevance of Z-GP association for GP assembly into viral particles [62].

Results from our laboratory using the chimeric TCRV/JUNV VLP system showed that coexpression of TCRV N was associated with a significant increment of G1 protein levels detected into VLPs, either in the presence or the absence of TCRV minigenome and L protein [58]. However, no apparent GP increase was observed into Z-directed VLPs when proteins corresponded entirely to JUNV [62]. Altogether, these observations suggest a role of Z-N complexes either in the efficient incorporation of GP or in stabilizing the GP structure on the particle envelope, specific to the chimeric system. Of note, the interaction between the matrix protein and the cytoplasmic domain of GP41 has been implicated in the stability of GP120-GP41 association on the surface of HIV particles [71].

3.3. Z oligomerization

Self-interaction of matrix proteins is thought to be critical for their function in budding of other enveloped viruses, such as Ebola and Rabies [72,73]. In the case of arenaviruses, evidence of self-interaction was initially provided for purified LCMV and LASV Z proteins expressed in bacteria [74]. Further studies of our laboratory to analyze the functional conformation of Z protein, conducted in mammalian cells, indicated that both TCRV and JUNV Z proteins self-associate into a ladder of oligomers, the putative dimer representing the major oligomeric form [32]. Analysis of a panel of Z mutants revealed that neither the integrity of the RING structure nor key residues required for Z-L contacts are involved in Z-Z interaction, indicating that homo-oligomerization is not needed for L recognition. Moreover, we demonstrated that amino acid G2, which is the N-terminal acceptor residue for protein myristoylation and conserved across the Arenaviridae, is required for self-association of TCRV and JUNV Z proteins [32]. The fact that residue G2 is also necessary for association of both Z proteins to the plasma membrane, strongly suggests that Z oligomerization is dependent on protein myristoylation and cell membrane targeting [32]. Whether myristate-promoted membrane association triggers Z homo-oligomerization hence stabilizing membrane binding, or alternatively, association of Z with the plasma membrane enhances Z local concentration facilitating its multimerization, is presently unknown. In any case, experimental data suggest that Z homo-oligomerization, which can be expected to present similar requirements for other arenaviruses, may play a critical role in the interaction between Z and GP and may represent a crucial step for virus assembly and budding.

Interestingly, we observed that upon coexpression in mammalian cells, the oligomerization-defective JUNV Z G2A mutant still displayed intracellular colocalization with N (Levingston, unpublished), suggesting that Z homo-oligomerization and plasma membrane targeting may not be required for its association with the N protein.

5. Concluding remarks

Studies on the interactions between viral proteins have improved our understanding of the mechanism of arenavirus genome expression and regulation, yet our knowledge of the details of these interactions remains limited. N homotypic interactions likely play a major role in RNA encapsidation, and may be required during viral RNA synthesis, when the interaction between N and L is assumed to operate. Further insight into the mechanism underlying these processes will be gained as more information of the structure of arenavirus nucleocapsids becomes available, as well as through additional studies using cell-based and in vitro reconstituted systems recreating viral RNA synthesis.

Current evidence supports the notion that Z protein operates as a key modulator of viral RNA synthesis by directly interacting with the L polymerase. However, little is known about the biological relevance of this Z function in the context of arenaviruses infections. Generation of recombinant viruses through reverse genetics, a methodology that has been developed for a number of arenaviruses [78,79,80,81,82], may provide the means for analyzing the role of this negative regulatory Z function in the context of acute and persistent viral infections. Other important questions, concerning the subcellular location of possible specialized sites of viral nucleocapsids recruitment by Z, how these complexes are eventually transported to the cell membrane, and the role of Z homo-oligomerization in Z-GP interaction, remain to be clarified. Further research on cellular factor(s) that could be involved in trafficking and assembly of the viral nucleocapsids, as well as in the Z-GP interaction is warranted. Future studies on viral protein-protein interactions relevant for viral gene expression, regulation and assembly, including those addressed to fully identify specific residues involved in diverse viral protein-protein complexes interfases, may provide important information on possible targets for the rational design of novel antiviral therapies against pathogenic arenaviruses.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to Maria Teresa Franze-Fernandez, Director of the Arenavirus laboratory at CEVAN until her retirement (2008), for her generous support. We thank the contributions of Rodrigo Jacamo (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA), Maximiliano Wilda (ICT Milstein, CONICET), and Juan Cruz Casabona (Fundación Instituto Leloir, Argentina) to the reviewed studies. We are also grateful to Osvaldo Rey (University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA), for his help in improving the article. MEL, ADA and NL are members of the Argentinean Council of Investigation (CONICET) and supported by grants from CONICET (PIP 0275/2011-13) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT; [PICT-1931/2008]) to NL.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Geisbert, T.W.; Jahrling, P.B. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Sepulveda, C.; Damonte, E.B. Novel therapeutic targets for arenavirus hemorrhagic fevers. Future Virology 2011, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrel, R.N.; de Lamballerie, X.; Emonet, S. Phylogeny of the genus Arenavirus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Peralta, L.A.; Coto, C.E.; Weissenbacher, M.C. The Tacaribe complex: the close relationship between a pathogenic (Junin) anda nonpathogenic (Tacaribe) arenavirus. In The Arenaviridae; Salvato, M.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, N.Y, U.S.A., 1993; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Franze-Fernández, M.T.; Iapalucci, S.; López, N.; Rossi, C. Subgenomic RNAs of Tacaribe virus. In The Arenaviridae; Salvato, M.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, N.Y, U.S.A., 1993; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier, M.J.; de La Torre, J.C.; Peters, C.J. Arenaviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, 5th; Knipe, D.M., Ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A., 2007; Volume 2, pp. 1791–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Kolakofsky, D.; Garcin, D. The unusual mechanism of arenavirus RNA synthesis. In The Arenaviridae; Salvato, M.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, N.Y, U.S.A., 1993; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, N.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. A single stem-loop structure in Tacaribe arenavirus intergenic region is essential for transcription termination but is not required for a correct initiation of transcription and replication. Virus Res. 2007, 124, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iapalucci, S.; Lopez, N.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. The 3' end termini of the Tacaribe arenavirus subgenomic RNAs. Virology 1991, 182, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, M.; Westerkofsky, M.; Muller, S.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Busch, C.; Gunther, S. Mutational analysis of the Lassa virus promoter. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 12414–12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; de la Torre, J.C. Characterization of the genomic promoter of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzusch, P.J.; Schenk, A.D.; Rahmeh, A.A.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Bavari, S.; Walz, T.; Whelan, S.P. Assembly of a functional Machupo virus polymerase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2010, 107, 20069–20074. [Google Scholar]

- Iapalucci, S.; Lopez, N.; Rey, O.; Zakin, M.M.; Cohen, G.N.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. The 5' region of Tacaribe virus L RNA encodes a protein with a potential metal binding domain. Virology 1989, 173, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, M.S.; Shimomaye, E.M. The completed sequence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus reveals a unique RNA structure and a gene for a zinc finger protein. Virology 1989, 173, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, K.L. RING domains: master builders of molecular scaffolds? J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 295, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell Dwyer, E.J.; Lai, H.; MacDonald, R.C.; Salvato, M.S.; Borden, K.L. The lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus RING protein Z associates with eukaryotic initiation factor 4E and selectively represses translation in a RING-dependent manner. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3293–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentsis, A.; Dwyer, E.C.; Perez, J.M.; Sharma, M.; Chen, A.; Pan, Z.Q.; Borden, K.L. The RING domains of the promyelocytic leukemia protein PML and the arenaviral protein Z repress translation by directly inhibiting translation initiation factor eIF4E. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 312, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpon, L.; Osborne, M.J.; Capul, A.A.; de la Torre, J.C.; Borden, K.L. Structural characterization of the Z RING-eIF4E complex reveals a distinct mode of control for eIF4E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2010, 107, 5441–5446. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, K.L.; Campbell Dwyer, E.J.; Salvato, M.S. An arenavirus RING (zinc-binding) protein binds the oncoprotein promyelocyte leukemia protein (PML) and relocates PML nuclear bodies to the cytoplasm. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 758–766. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, K.L.; Campbell Dwyer, E.J.; Carlile, G.W.; Djavani, M.; Salvato, M.S. Two RING finger proteins, the oncoprotein PML and the arenavirus Z protein, colocalize with the nuclear fraction of the ribosomal P proteins. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3819–3826. [Google Scholar]

- Topcu, Z.; Mack, D.L.; Hromas, R.A.; Borden, K.L. The promyelocytic leukemia protein PML interacts with the proline-rich homeodomain protein PRH: a RING may link hematopoiesis and growth control. Oncogene 1999, 18, 7091–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djavani, M.; Topisirovic, I.; Zapata, J.C.; Sadowska, M.; Yang, Y.; Rodas, J.; Lukashevich, I.S.; Bogue, C.W.; Pauza, C.D.; Borden, K.L.; Salvato, M.S. The proline-rich homeodomain (PRH/HEX) protein is down-regulated in liver during infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I. Z proteins of New World arenaviruses bind RIG-I and interfere with type I interferon induction. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, M.S. Molecular biology of the prototype arenavirus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. In The Arenaviridae; Salvato, M.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, N.Y, U.S.A., 1993; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Iapalucci, S.; Chernavsky, A.; Rossi, C.; Burgin, M.J.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. Tacaribe virus gene expression in cytopathic and non-cytopathic infections. Virology 1994, 200, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, N.; Jacamo, R.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. Transcription and RNA replication of Tacaribe virus genome and antigenome analogs require N and L proteins: Z protein is an inhibitor of these processes. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 12241–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Novella, I.S.; Teng, M.N.; Oldstone, M.B.; de La Torre, J.C. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3470–3477. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, T.I.; de la Torre, J.C. RING finger Z protein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) inhibits transcription and RNA replication of an LCMV S-segment minigenome. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 9415–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, M.; Golnitz, U.; Muller, S.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Gunther, S. Replicon system for Lassa virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13793–13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzusch, P.J.; Whelan, S.P. Arenavirus Z protein controls viral RNA synthesis by locking a polymerase-promoter complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2011, 108, 19743–19748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacamo, R.; Lopez, N.; Wilda, M.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. Tacaribe virus Z protein interacts with the L polymerase protein to inhibit viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10383–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.E.; Wilda, M.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; D'Antuono, A.; Foscaldi, S.; Marino Buslje, C.; Lopez, N. Molecular determinants of arenavirus Z protein homo-oligomerization and L polymerase binding. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12304–12314. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, R.; Poch, O.; Delarue, M.; Bishop, D.H.; Bouloy, M. Rift Valley fever virus L segment: correction of the sequence and possible functional role of newly identified regions conserved in RNA-dependent polymerases. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Orta, C.; Arias, A.; Escarmis, C.; Verdaguer, N. A comparison of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006, 16, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, M.; Lelke, M.; Busch, C.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Gunther, S. Mutational evidence for a structural model of the Lassa virus RNA polymerase domain and identification of two residues, Gly1394 and Asp1395, that are critical for transcription but not replication of the genome. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10207–10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieth, S.; Torda, A.E.; Asper, M.; Schmitz, H.; Gunther, S. Sequence analysis of L RNA of Lassa virus. Virology 2004, 318, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunotte, L.; Lelke, M.; Hass, M.; Kleinsteuber, K.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Gunther, S. Domain structure of Lassa virus L protein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, B.; Coutard, B.; Lelke, M.; Ferron, F.; Kerber, R.; Jamal, S.; Frangeul, A.; Baronti, C.; Charrel, R.; de Lamballerie, X.; Vonrhein, C.; Lescar, J.; Bricogne, G.; Gunther, S.; Canard, B. The N-terminal domain of the arenavirus L protein is an RNA endonuclease essential in mRNA transcription. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001038. [Google Scholar]

- Lelke, M.; Brunotte, L.; Busch, C.; Gunther, S. An N-terminal region of Lassa virus L protein plays a critical role in transcription but not replication of the virus genome. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1934–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilda, M.; Lopez, N.; Casabona, J.C.; Franze-Fernandez, M.T. Mapping of the Tacaribe arenavirus Z-protein binding sites on the L protein identified both amino acids within the putative polymerase domain and a region at the N terminus of L that are critically involved in binding. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11454–11460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.B.; de la Torre, J.C. Genetic and biochemical evidence for an oligomeric structure of the functional L polymerase of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7262–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, R.; Rieger, T.; Busch, C.; Flatz, L.; Pinschewer, D.D.; Kummerer, B.M.; Gunther, S. Cross-species analysis of the replication complex of Old World arenaviruses reveals two Nucleoprotein sites involved in L protein function. J. Virol. 2010, 85, 12518–12528. [Google Scholar]

- Levingston Macleod, J.M.; D'Antuono, A.; Loureiro, M.E.; Casabona, J.C.; Gomez, G.A.; Lopez, N. Identification of two functional domains within the arenavirus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Riaño, E.; Cheng, B.Y.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martinez-Sobrido, L. Self-association of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein is mediated by its N-terminal region and is not required for its anti-interferon function. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3307–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Lan, S.; Wang, W.; Schelde, L.M.; Dong, H.; Wallat, G.D.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 2010, 468, 779–783. [Google Scholar]

- Brunotte, L.; Kerber, R.; Shang, W.; Hauer, F.; Hass, M.; Gabriel, M.; Lelke, M.; Busch, C.; Stark, H.; Svergun, D.I.; Betzel, C.; Perbandt, M.; Günther, S. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein revealed by X-ray crystallography, small-angle X-ray scattering, and electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 38748–38756. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, K.M.; Liu, T.; Li, S.; King, L.B.; Ngo, N.; Zandonatti, M.A.; Woods, V.L., Jr.; de la Torre, J.C.; Saphire, E.O. Crystal structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex reveals a gating mechanism for RNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2011, 108, 19365–19370. [Google Scholar]

- Albertini, A.A.; Schoehn, G.; Weissenhorn, W.; Ruigrok, R.W. Structural aspects of rabies virus replication. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2008, 65, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruigrok, R.W.; Crepin, T.; Kolakofsky, D. Nucleoproteins and nucleocapsids of negative-strand RNA viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 504–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ferron, F.; Li, Z.; Danek, E.I.; Luo, D.; Wong, Y.; Coutard, B.; Lantez, V.; Charrel, R.; Canard, B.; Walz, T.; Lescar, J. The hexamer structure of Rift Valley fever virus nucleoprotein suggests a mechanism for its assembly into ribonucleoprotein complexes. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, M.S.; Schweighofer, K.J.; Burns, J.; Shimomaye, E.M. Biochemical and immunological evidence that the 11 kDa zinc-binding protein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is a structural component of the virus. Virus Res. 1992, 22, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Craven, R.C.; de la Torre, J.C. The small RING finger protein Z drives arenavirus budding: implications for antiviral strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2003, 100, 12978–12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecker, T.; Eichler, R.; Meulen, J.; Weissenhorn, W.; Dieter Klenk, H.; Garten, W.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus Z protein is a matrix protein and sufficient for the release of virus-like particles [corrected]. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10700–10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; Noda, T.; Kawaoka, Y.; Yokosawa, H.; Yasuda, J. Cellular factors required for Lassa virus budding. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4191–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecker, T.; Maisa, A.; Daffis, S.; Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Garten, W. The role of myristoylation in the membrane association of the Lassa virus matrix protein Z. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Greenwald, D.L.; de la Torre, J.C. Myristoylation of the RING finger Z protein is essential for arenavirus budding. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11443–11448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, R.; Strecker, T.; Kolesnikova, L.; ter Meulen, J.; Weissenhorn, W.; Becker, S.; Klenk, H.D.; Garten, W.; Lenz, O. Characterization of the Lassa virus matrix protein Z: electron microscopic study of virus-like particles and interaction with the nucleoprotein (NP). Virus. Res. 2004, 100, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabona, J.C.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; Loureiro, M.E.; Gomez, G.A.; Lopez, N. The RING domain and the L79 residue of Z protein are involved in both the rescue of nucleocapsids and the incorporation of glycoproteins into infectious chimeric arenavirus-like particles. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7029–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levingston Macleod, J.M.; Casabona, J.C.; Gómez, G.; Loureiro, E.; Wilda, M.; López, N. Mapping of interacting domains between the nucleoprotein and Z matrix protein of New World Arenaviruses. In XIV International Conference on Negative Strand Viruses, Brugge, Belgium, June 20-25, 2010; p. 87, Abstract 80.

- Capul, A.A.; de la Torre, J.C.; Buchmeier, M.J. Conserved residues in Lassa fever virus Z protein modulate viral infectivity at the level of the ribonucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3172–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; Yasuda, J.; de la Torre, J.C. The Z protein of the New World arenavirus Tacaribe virus has bona fide budding activity that does not depend on known late domain motifs. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12651–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groseth, A.; Wolff, S.; Strecker, T.; Hoenen, T.; Becker, S. Efficient budding of the Tacaribe virus matrix protein Z requires the nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3603–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtanko, O.; Watanabe, S.; Jasenosky, L.D.; Watanabe, T.; Kawaoka, Y. ALIX/AIP1 is required for NP incorporation into Mopeia virus Z-induced virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3631–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Riaño, E.; Cheng, B.Y.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martinez-Sobrido, L. The C-terminal region of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein contains distinct and segregable functional domains involved in NP-Z interaction and counteraction of the type I interferon response. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 13038–13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtanko, O.; Imai, M.; Goto, H.; Lukashevich, I.S.; Neumann, G.; Watanabe, T.; Kawaoka, Y. A role for the C terminus of Mopeia virus nucleoprotein in its incorporation into Z protein-induced virus-like particles. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 5415–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunberg, J.H.; York, J. The curious case of arenavirus entry, and its inhibition. Viruses 2012, 4, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, E.; Kolesnikova, L.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W.; Becker, S. Role of the transmembrane domain of Marburg virus surface protein GP in assembly of the viral envelope. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3942–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkley, M.A.; Luttge, B.G.; Freed, E.O. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis, trafficking, and incorporation. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 582–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capul, A.A.; Perez, M.; Burke, E.; Kunz, S.; Buchmeier, M.J.; de la Torre, J.C. Arenavirus Z-glycoprotein association requires Z myristoylation but not functional RING or late domains. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9451–9460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlie, K.; Maisa, A.; Freiberg, F.; Groseth, A.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W. Viral protein determinants of Lassa virus entry and release from polarized epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3178–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.R.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, J.; Freed, E.O.; Aiken, C. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein destabilizes the interaction of the envelope protein subunits gp120 and gp41. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 2405–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, A.; Harty, R.N. Rabies virus assembly and budding. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 79, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlieb, B.; Weissenhorn, W. Filovirus assembly and budding. Virology 2006, 344, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentsis, A.; Gordon, R.E.; Borden, K.L. Self-assembly properties of a model RING domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2002, 99, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu, T.I.; Feldmann, H.; de la Torre, J.C. Cells expressing the RING finger Z protein are resistant to arenavirus infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2979–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, G.; Echave, J.; Ghiringhelli, D.; Romanowski, V. Computational characterisation of potential RNA-binding sites in arenavirus nucleocapsid proteins. Virus Genes 1996, 13, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; de la Torre, J.C. Arenavirus budding. Adv. Virol. 2011, 2011, 180326. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, S.; McLay Schelde, L.; Wang, J.; Kumar, N.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. Development of infectious clones for virulent and avirulent Pichinde viruses: a model virus to study arenavirus-induced hemorrhagic fevers. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6357–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albariño, C.G.; Bergeron, E.; Erickson, B.R.; Khristova, M.L.; Rollin, P.E.; Nichol, S.T. Efficient reverse genetics generation of infectious Junin viruses differing in glycoprotein processing. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5606–5614. [Google Scholar]

- Flatz, L.; Bergthaler, A.; de la Torre, J.C.; Pinschewer, D.D. Recovery of an arenavirus entirely from RNA polymerase I/II-driven cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2006, 103, 4663–4668. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.B.; de la Torre, J.C. Rescue of the prototypic Arenavirus LCMV entirely from plasmid. Virology 2006, 350, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emonet, S.F.; Seregin, A.V.; Yun, N.E.; Poussard, A.L.; Walker, A.G.; de la Torre, J.C.; Paessler, S. Rescue from cloned cDNAs and in vivo characterization of recombinant pathogenic Romero and live-attenuated Candid #1 strains of Junin virus, the causative agent of Argentine hemorrhagic fever disease. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).