The Role of Posttranslational Modifications During Ebola Virus Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

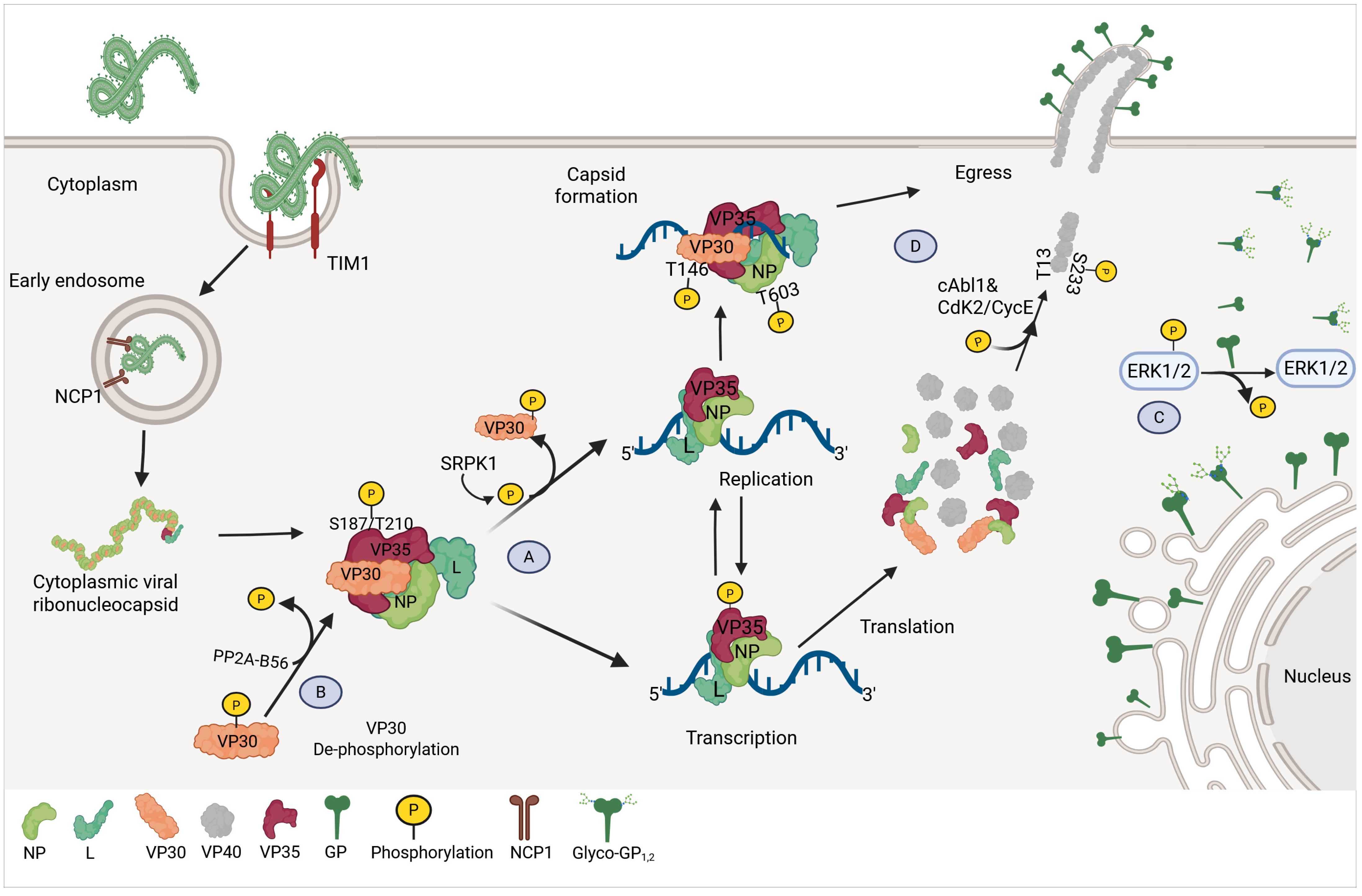

1.1. OEV Structure and Life Cycle

1.2. Innate Immunity to OEV

2. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) During Virus Infection

2.1. Phosphorylation

2.1.1. Phosphorylation During OEV Replication

VP30 Phosphorylation

VP35 Phosphorylation

NP Phosphorylation

GP Phosphorylation

VP40 Phosphorylation

2.2. Ubiquitination

2.2.1. Ubiquitination During OEV Infection

NP Ubiquitination

VP35 Ubiquitination

GP Ubiquitination

VP40 Ubiquitination

2.2.2. SUMOylation

SUMOylation of IRF7

SUMOylation and Ubiquitination Interplay in EBOV VP24

SUMOylation and EBOV VP40

2.3. Glycosylation

Glycosylation of GP

2.4. Protein Acetylation

2.4.1. Acetylation in OEV

NEDD4 Acetylation by P300

2.5. Acylation

OEV Protein Acylation

3. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBOV | Ebola virus |

| EVD | Ebolavirus Disease |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| ROC | Republic of Congo |

| SUDV | Sudan virus |

| BDBV | Bundibugyo virus |

| TAFV | Taï Forest virus |

| BOMV | Bombali virus |

| RESTV | Reston virus |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| Ub | Ubiquitination |

| dsRNA | double-stranded RNA |

| NPC1 | Niemann-Pick C1 protein |

| IFN-I | Type-I Interferon |

| GP | Glycoprotein |

| sGP | Soluble GP |

| ssGP | Small soluble GP |

| NP | Nucleoprotein |

| PRRs | Pattern Recognition Receptors |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| ISG | Interferon Stimulated-Genes |

| MDA5 | Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 |

| IRF3 | IFN-regulation factor 3 |

| IRF7 | IFN-regulation factor 7 |

| MDL | Mucin-like domain |

| PP1 | Protein Phosphatase 1 |

| SRPK1 | Serine-arginine protein kinase 1 |

| LC-MS/MS | High-resolution liquid chromatography-linked tandem mass spectrometry |

| VLPs | Virus-like particles |

| WT | Wild-Type |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| USP5 | Deubiquitinase Isopeptidase T |

| SUMO | Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier |

| SIM | SUMO-interacting motif |

| SENPs | SUMO-specific proteases |

| ERAD | Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation |

| UBD | Ubiquitin-binding domains |

| trVLPs | Transcription and replication competent virus-like particles |

| pDCs | Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells |

| IDD | IFN-inhibiting domain |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ppGalNAcT | N-acetylgalactosaminetransferases |

| BSL4 | Biosafety level 4 facilities |

References

- Kuhn, J.H.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Basler, C.F.; Bavari, S.; Bukreyev, A.; Chandran, K.; Crozier, I.; Dolnik, O.; Dye, J.M.; Formenty, P.B.H.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Filoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 911–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T.W.; Johnson, K.M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Lipkin, W.I.; Negredo, A.I.; Netesov, S.V.; Nichol, S.T.; et al. Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 2083–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Guenno, B.; Formenty, P.; Wyers, M.; Gounon, P.; Walker, F.; Boesch, C. Isolation and partial characterisation of a new strain of Ebola virus. Lancet 1995, 345, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, D.; Hamlet, A.; Michaelis, M.; Wass, M.N.; Rossman, J.S. Risks Posed by Reston, the Forgotten Ebolavirus. mSphere 2016, 1, e00322-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of an International Commission. Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976. Bull. World Health Organ. 1978, 56, 271–293.

- Jacob, S.T.; Crozier, I.; Fischer, W.A.; Hewlett, A.; Kraft, C.S.; Vega, M.-A.d.L.; Soka, M.J.; Wahl, V.; Griffiths, A.; Bollinger, L.; et al. Ebola virus disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letafati, A.; Salahi Ardekani, O.; Karami, H.; Soleimani, M. Ebola virus disease: A narrative review. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 181, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News; Sudan Virus Disease in Uganda. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON566 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Ebola Outbreak in the DRC: Current Situation. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ebola/situation-summary/index.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Shuaib, F.; Gunnala, R.; Musa, E.O.; Mahoney, F.J.; Oguntimehin, O.; Nguku, P.M.; Nyanti, S.B.; Knight, N.; Gwarzo, N.S.; Idigbe, O.; et al. Ebola virus disease outbreak—Nigeria, July-September 2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Judson, S.D.; Munster, V.J. The Multiple Origins of Ebola Disease Outbreaks. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, S465–S473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlberger, E. Filovirus Replication and Transcription. Future Virol. 2007, 2, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbert, T.W.; Young, H.A.; Jahrling, P.B.; Davis, K.J.; Larsen, T.; Kagan, E.; Hensley, L.E. Pathogenesis of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever in Primate Models: Evidence that Hemorrhage Is Not a Direct Effect of Virus-Induced Cytolysis of Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 2371–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, P.; Santos, R.I.; Ramanathan, P.; Iampietro, M.; Nishida, A.; Dutta, M.; Ammosova, T.; Meyer, M.; Katze, M.G.; Popov, V.L.; et al. Ebola virus-mediated T-lymphocyte depletion is the result of an abortive infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1008068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet 2011, 377, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuyama, W.; Marzi, A. Ebola Virus: Pathogenesis and Countermeasure Development. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.F.; Kolokoltsov, A.A.; Albrecht, T.; Davey, R.A. Cellular Entry of Ebola Virus Involves Uptake by a Macropinocytosis-Like Mechanism and Subsequent Trafficking through Early and Late Endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrowicz, P.; Marzi, A.; Biedenkopf, N.; Beimforde, N.; Becker, S.; Hoenen, T.; Feldmann, H.; Schnittler, H.-J. Ebola Virus Enters Host Cells by Macropinocytosis and Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, S957–S967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanbo, A.; Imai, M.; Watanabe, S.; Noda, T.; Takahashi, K.; Neumann, G.; Halfmann, P.; Kawaoka, Y. Ebolavirus Is Internalized into Host Cells via Macropinocytosis in a Viral Glycoprotein-Dependent Manner. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, B.; Rogers, K.; Phillips, E.K.; Brouillette, R.B.; Bouls, R.; Butler, N.S.; Maury, W. TIM-1 serves as a receptor for Ebola virus in vivo, enhancing viremia and pathogenesis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0006983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Song, J.; Qi, J.; Lu, G.; Yan, J.; Gao, G.F. Ebola Viral Glycoprotein Bound to Its Endosomal Receptor Niemann-Pick C1. Cell 2016, 164, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller-Tank, S.; Maury, W. Ebola Virus Entry: A Curious and Complex Series of Events. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, J.; Scianimanico, S.; Schoehn, G.; Weissenhorn, W. Vesicular Release of Ebola Virus Matrix Protein VP40. Virology 2001, 283, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Abelson, D.M.; Li, S.; Wood, M.R.; Saphire, E.O. Assembly of the Ebola Virus Nucleoprotein from a Chaperoned VP35 Complex. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlberger, E.; Weik, M.; Volchkov, V.E.; Klenk, H.-D.; Becker, S. Comparison of the Transcription and Replication Strategies of Marburg Virus and Ebola Virus by Using Artificial Replication Systems. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedenkopf, N.; Schlereth, J.; Grünweller, A.; Becker, S.; Hartmann, R.K. RNA Binding of Ebola Virus VP30 Is Essential for Activating Viral Transcription. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 7481–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenen, T.; Shabman, R.S.; Groseth, A.; Herwig, A.; Weber, M.; Schudt, G.; Dolnik, O.; Basler, C.F.; Becker, S.; Feldmann, H. Inclusion Bodies Are a Site of Ebolavirus Replication. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11779–11788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.B.; Hayward, J.A.; Marsh, G.A.; Baker, M.L.; Tachedjian, G. Host and Viral Proteins Modulating Ebola and Marburg Virus Egress. Viruses 2019, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meylan, E.; Tschopp, J.; Karin, M. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature 2006, 442, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisse, M.; Ly, H. Comparative Structure and Function Analysis of the RIG-I-Like Receptors: RIG-I and MDA5. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, A.M.; Gale, M. RIG-I in RNA virus recognition. Virology 2015, 479–480, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häcker, H.; Karin, M. Regulation and Function of IKK and IKK-Related Kinases. Sci. STKE 2006, 2006, re13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; McWhirter, S.M.; Faia, K.L.; Rowe, D.C.; Latz, E.; Golenbock, D.T.; Coyle, A.J.; Liao, S.-M.; Maniatis, T. IKKε and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chathuranga, K.; Weerawardhana, A.; Dodantenna, N.; Lee, J.-S. Regulation of antiviral innate immune signaling and viral evasion following viral genome sensing. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1647–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; Rice, C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 2011, 472, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platanias, L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, W.B.; Loo, Y.-M.; Gale, M.; Hartman, A.L.; Kimberlin, C.R.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Saphire, E.O.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus VP35 Protein Binds Double-Stranded RNA and Inhibits Alpha/Beta Interferon Production Induced by RIG-I Signaling. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5168–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qian, C.; Cao, X. Post-Translational Modification Control of Innate Immunity. Immunity 2016, 45, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deribe, Y.L.; Pawson, T.; Dikic, I. Post-translational modifications in signal integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venne, A.S.; Kollipara, L.; Zahedi, R.P. The next level of complexity: Crosstalk of posttranslational modifications. Proteomics 2014, 14, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammarén, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qi, D.; Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, W. Unconventional posttranslational modification in innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamontin, C.; Bossis, G.; Nisole, S.; Arhel, N.J.; Maarifi, G. Regulation of Viral Restriction by Post-Translational Modifications. Viruses 2021, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, H.; Xing, Y. Role of protein Post-translational modifications in enterovirus infection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1341599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez-Brochero, M.; Behera, P.; Afreen, K.S.; Odle, A.; Rajsbaum, R. Chapter One—Ubiquitination in viral entry and replication: Mechanisms and implications. In Advances in Virus Research; MacDiarmid, R., Lee, B., Beer, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 119, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol, S.; Hage, A.; Giraldo, M.I.; Bharaj, P.; Rajsbaum, R. The TRIMendous Role of TRIMs in Virus–Host Interactions. Vaccines 2017, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, A.; Bharaj, P.; van Tol, S.; Giraldo, M.I.; Gonzalez-Orozco, M.; Valerdi, K.M.; Warren, A.N.; Aguilera-Aguirre, L.; Xie, X.; Widen, S.G.; et al. The RNA helicase DHX16 recognizes specific viral RNA to trigger RIG-I-dependent innate antiviral immunity. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, A.K.; Mühlberger, E.; Muñoz-Fontela, C. Immune barriers of Ebola virus infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018, 28, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, C.F. Innate immune evasion by filoviruses. Virology 2015, 479–480, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejnik, J.; Hume, A.J.; Leung, D.W.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Basler, C.F.; Mühlberger, E. Filovirus Strategies to Escape Antiviral Responses. In Marburg- and Ebolaviruses: From Ecosystems to Molecules; Mühlberger, E., Hensley, L.L., Towner, J.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ardito, F.; Giuliani, M.; Perrone, D.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.B.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The Protein Kinase Complement of the Human Genome. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bononi, A.; Agnoletto, C.; De Marchi, E.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Bonora, M.; Giorgi, C.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; Rimessi, A.; et al. Protein kinases and phosphatases in the control of cell fate. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 329098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zha, X.; Tan, Y.; Hornbeck, P.V.; Mastrangelo, A.J.; Alessi, D.R.; Polakiewicz, R.D.; Comb, M.J. Phosphoprotein Analysis Using Antibodies Broadly Reactive against Phosphorylated Motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 39379–39387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, H.; Shaytan, A.; Panchenko, A.R. Physicochemical mechanisms of protein regulation by phosphorylation. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chance, M.R. Integrating phosphoproteomics in systems biology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 10, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Joshi, R.; Feller, S.M.; Li, S.S.C. Phosphotyrosine recognition domains: The typical, the atypical and the versatile. Cell Commun. Signal. 2012, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinti, M.; Kiemer, L.; Costa, S.; Miller, M.L.; Sacco, F.; Olsen, J.V.; Carducci, M.; Paoluzi, S.; Langone, F.; Workman, C.T.; et al. The SH2 Domain Interaction Landscape. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dai, T.; Sun, W.; Wei, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, F. Protein N-myristoylation: Functions and mechanisms in control of innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modrof, J.; Mu¨hlberger, E.; Klenk, H.-D.; Becker, S. Phosphorylation of VP30 Impairs Ebola Virus Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 33099–33104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenkopf, N.; Hartlieb, B.; Hoenen, T.; Becker, S. Phosphorylation of Ebola Virus VP30 Influences the Composition of the Viral Nucleocapsid Complex: IMPACT ON VIRAL TRANSCRIPTION AND REPLICATION. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11165–11174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, Y.; Krähling, V.; Kolesnikova, L.; Halwe, S.; Lier, C.; Baumeister, S.; Noda, T.; Biedenkopf, N.; Becker, S. Serine-Arginine Protein Kinase 1 Regulates Ebola Virus Transcription. mBio 2020, 11, e02565-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilinykh, P.A.; Tigabu, B.; Ivanov, A.; Ammosova, T.; Obukhov, Y.; Garron, T.; Kumari, N.; Kovalskyy, D.; Platonov, M.O.; Naumchik, V.S.; et al. Role of Protein Phosphatase 1 in Dephosphorylation of Ebola Virus VP30 Protein and Its Targeting for the Inhibition of Viral Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 22723–22738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Biedenkopf, N.; Hertz, E.P.T.; Dietzel, E.; Stalmann, G.; López-Méndez, B.; Davey, N.E.; Nilsson, J.; Becker, S. The Ebola Virus Nucleoprotein Recruits the Host PP2A-B56 Phosphatase to Activate Transcriptional Support Activity of VP30. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 136–145.e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Ramanathan, P.; Parry, C.; Ilinykh, P.A.; Lin, X.; Petukhov, M.; Obukhov, Y.; Ammosova, T.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Bukreyev, A.; et al. Global phosphoproteomic analysis of Ebola virions reveals a novel role for VP35 phosphorylation-dependent regulation of genome transcription. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2579–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, K.C.; Cárdenas, W.B.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus Protein VP35 Impairs the Function of Interferon Regulatory Factor-Activating Kinases IKKε and TBK-1. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Jin, J.; Wang, T.; Hu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gao, T.; Dong, Q.; Jin, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; et al. Ebola virus sequesters IRF3 in viral inclusion bodies to evade host antiviral immunity. eLife 2024, 12, RP88122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.S.; Fitzgerald, K.A. The cGAS-STING Pathway for DNA Sensing. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Gao, T.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, P.; Xu, K.; Zou, G.; et al. Ebola virus replication is regulated by the phosphorylation of viral protein VP35. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Moyer, C.L.; Abelson, D.M.; Saphire, E.O. The Ebola Virus VP30-NP Interaction Is a Regulator of Viral RNA Synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötfering, B.; Mühlberger, E.; Tamura, T.; Klenk, H.-D.; Becker, S. The Nucleoprotein of Marburg Virus Is Target for Multiple Cellular Kinases. Virology 1999, 255, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Huppertz, S.; Klenk, H.-D.; Feldmann, H. The nucleoprotein of Marburg virus is phosphorylated. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrol, J.; Thizon, C.; Gaillard, J.-C.; Marchetti, C.; Armengaud, J.; Rollin-Genetet, F. Multiple phosphorylable sites in the Zaire Ebolavirus nucleoprotein evidenced by high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J. Virol. Methods 2013, 187, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämper, L.; Kuhl, I.; Vallbracht, M.; Hoenen, T.; Linne, U.; Weber, A.; Chlanda, P.; Kracht, M.; Biedenkopf, N. To be or not to be phosphorylated: Understanding the role of Ebola virus nucleoprotein in the dynamic interplay with the transcriptional activator VP30 and the host phosphatase PP2A-B56. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2447612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Tigabu, B.; Ivanov, A.; Jerebtsova, M.; Ammosova, T.; Ramanathan, P.; Kumari, N.; Brantner, C.A.; Pietzsch, C.A.; Simhadri, J.; et al. Ebola virus nucleoprotein interaction with host protein phosphatase-1 regulates its dimerization and capsid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, C.A.; Fortin, J.-F.; Nolan, G.P.; Nabel, G.J. The ERK Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway Contributes to Ebola Virus Glycoprotein-Induced Cytotoxicity. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cocka, L.; Okumura, A.; Zhang, Y.-A.; Sunyer, J.O.; Harty, R.N. Conserved Motifs within Ebola and Marburg Virus VP40 Proteins Are Important for Stability, Localization, and Subsequent Budding of Virus-Like Particles. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.; Cooper, A.; Shi, W.; Bornmann, W.; Carrion, R.; Kalman, D.; Nabel, G.J. Productive Replication of Ebola Virus Is Regulated by the c-Abl1 Tyrosine Kinase. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 123ra124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleet, M.L.; Mathiesen, A.; DeMarino, C.; Akpamagbo, Y.A.; Barclay, R.A.; Schwab, A.; Iordanskiy, S.; Sampey, G.C.; Lepene, B.; Ilinykh, P.A.; et al. Ebola VP40 in Exosomes Can Cause Immune Cell Dysfunction. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikova, L.; Mittler, E.; Schudt, G.; Shams-Eldin, H.; Becker, S. Phosphorylation of Marburg virus matrix protein VP40 triggers assembly of nucleocapsids with the viral envelope at the plasma membrane. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The Ubiquitin Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, R.B. The ubiquitin system: From cell signalling to disease biology and new therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, B.A.; Harper, J.W. Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: The apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.D.; Ritterhoff, T.; Klevit, R.E.; Brzovic, P.S. E2 enzymes: More than just middle men. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y. E3 ubiquitin ligases: Styles, structures and functions. Mol. Biomed. 2021, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, X. Current methodologies in protein ubiquitination characterization: From ubiquitinated protein to ubiquitin chain architecture. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracz, M.; Bialek, W. Beyond K48 and K63: Non-canonical protein ubiquitination. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2021, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kinch, L.N.; Brautigam, C.A.; Chen, X.; Du, F.; Grishin, N.V.; Chen, Z.J. Ubiquitin-Induced Oligomerization of the RNA Sensors RIG-I and MDA5 Activates Antiviral Innate Immune Response. Immunity 2012, 36, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajsbaum, R.; Versteeg, G.A.; Schmid, S.; Maestre, A.M.; Belicha-Villanueva, A.; Martinez-Romero, C.; Patel, J.R.; Morrison, J.; Pisanelli, G.; Miorin, L.; et al. Unanchored K48-linked polyubiquitin synthesized by the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6 stimulates the interferon-IKKepsilon kinase-mediated antiviral response. Immunity 2014, 40, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.-P.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Pineda, G.; Jiang, X.; Adhikari, A.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Z.J. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature 2009, 461, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Salazar, C.A.; van Tol, S.; Mailhot, O.; Gonzalez-Orozco, M.; Galdino, G.T.; Warren, A.N.; Teruel, N.; Behera, P.; Afreen, K.S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Ebola virus VP35 interacts non-covalently with ubiquitin chains to promote viral replication. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.S.; Schmitt, P.T.; Pei, Z.; Schmitt, A.P. Role of Ubiquitin in Parainfluenza Virus 5 Particle Formation. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3474–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, A.; Chau, V.; Wills, J.W. Ubiquitin is part of the retrovirus budding machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13069–13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putterman, D.; Pepinsky, R.B.; Vogt, V.M. Ubiquitin in avian leukosis virus particles. Virology 1990, 176, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galao, R.P.; Wilson, H.; Schierhorn, K.L.; Debeljak, F.; Bodmer, B.S.; Goldhill, D.; Hoenen, T.; Wilson, S.J.; Swanson, C.M.; Neil, S.J.D. TRIM25 and ZAP target the Ebola virus ribonucleoprotein complex to mediate interferon-induced restriction. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gack, M.U.; Shin, Y.C.; Joo, C.-H.; Urano, T.; Liang, C.; Sun, L.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S.; Chen, Z.; Inoue, S.; et al. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature 2007, 446, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayman, T.J.; Hsu, A.C.; Kolesnik, T.B.; Dagley, L.F.; Willemsen, J.; Tate, M.D.; Baker, P.J.; Kershaw, N.J.; Kedzierski, L.; Webb, A.I.; et al. RIPLET, and not TRIM25, is required for endogenous RIG-I-dependent antiviral responses. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2019, 97, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharaj, P.; Atkins, C.; Luthra, P.; Giraldo, M.I.; Dawes, B.E.; Miorin, L.; Johnson, J.R.; Krogan, N.J.; Basler, C.F.; Freiberg, A.N.; et al. The Host E3-Ubiquitin Ligase TRIM6 Ubiquitinates the Ebola Virus VP35 Protein and Promotes Virus Replication. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00833-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tol, S.; Kalveram, B.; Ilinykh, P.A.; Ronk, A.; Huang, K.; Aguilera-Aguirre, L.; Bharaj, P.; Hage, A.; Atkins, C.; Giraldo, M.I.; et al. Ubiquitination of Ebola virus VP35 at lysine 309 regulates viral transcription and assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwase, G.; Luthra, P.; Vogel, O.A.; Batra, J.; La Rosa, B.A.; Sheehan, K.C.F.; Khatavkar, O.; Payton, J.E.; Davey, R.A.; Krogan, N.J.; et al. Ebola virus VP35 NNLNS motif modulates viral RNA synthesis and MIB2-mediated signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2411961122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.K.; Jude, K.M.; Banerjee, A.L.; Haldar, M.; Manokaran, S.; Kooren, J.; Mallik, S.; Christianson, D.W. Structural Analysis of Charge Discrimination in the Binding of Inhibitors to Human Carbonic Anhydrases I and II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5528–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachino, J.-i.; Jin, W.; Kimura, K.; Kurosaki, H.; Sato, A.; Arakawa, Y. Sulfamoyl Heteroarylcarboxylic Acids as Promising Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitors for Controlling Bacterial Carbapenem Resistance. mBio 2020, 11, e03144-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francica, J.R.; Matukonis, M.K.; Bates, P. Requirements for cell rounding and surface protein down-regulation by Ebola virus glycoprotein. Virology 2009, 383, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volchkov, V.E.; Volchkova, V.A.; Mühlberger, E.; Kolesnikova, L.V.; Weik, M.; Dolnik, O.; Klenk, H.-D. Recovery of Infectious Ebola Virus from Complementary DNA: RNA Editing of the GP Gene and Viral Cytotoxicity. Science 2001, 291, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuyama, W.; Shifflett, K.; Feldmann, H.; Marzi, A. The Ebola virus soluble glycoprotein contributes to viral pathogenesis by activating the MAP kinase signaling pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Gao, X.; Peng, C.; Shan, C.; Johnson, S.F.; Schwartz, R.C.; Zheng, Y.H. RNF185 regulates proteostasis in Ebolavirus infection by crosstalk between the calnexin cycle, ERAD, and reticulophagy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Khan, I.; Ahmad, I.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.H. MARCH8 Inhibits Ebola Virus Glycoprotein, Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Envelope Glycoprotein, and Avian Influenza Virus H5N1 Hemagglutinin Maturation. mBio 2020, 11, e01882-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Bai, Y.; Tan, W.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhai, J.; Xue, M.; Tang, Y.-D.; Zheng, C.; et al. Human MARCH1, 2, and 8 block Ebola virus envelope glycoprotein cleavage via targeting furin P domain. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartlieb, B.; Weissenhorn, W. Filovirus assembly and budding. Virology 2006, 344, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harty, R.N.; Brown, M.E.; Wang, G.; Huibregtse, J.; Hayes, F.P. A PPxY motif within the VP40 protein of Ebola virus interacts physically and functionally with a ubiquitin ligase: Implications for filovirus budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13871–13876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Sagum, C.A.; Takizawa, F.; Ruthel, G.; Berry, C.T.; Kong, J.; Sunyer, J.O.; Freedman, B.D.; Bedford, M.T.; Sidhu, S.S.; et al. Ubiquitin Ligase WWP1 Interacts with Ebola Virus VP40 To Regulate Egress. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00812-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Sagum, C.A.; Bedford, M.T.; Sidhu, S.S.; Sudol, M.; Harty, R.N. ITCH E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Interacts with Ebola Virus VP40 To Regulate Budding. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9163–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepley-McTaggart, A.; Schwoerer, M.P.; Sagum, C.A.; Bedford, M.T.; Jaladanki, C.K.; Fan, H.; Cassel, J.; Harty, R.N. Ubiquitin Ligase SMURF2 Interacts with Filovirus VP40 and Promotes Egress of VP40 VLPs. Viruses 2021, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Yang, T.T.; Lin, K.I. Mechanisms and functions of SUMOylation in health and disease: A review focusing on immune cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zong, Z.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. SUMOylation in Viral Replication and Antiviral Defense. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Yang, X. SUMO E3 ligase activity of TRIM proteins. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeev, T.K.; Joshi, G.; Arya, P.; Mahajan, V.; Chaturvedi, A.; Mishra, R.K. SUMO and SUMOylation Pathway at the Forefront of Host Immune Response. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 681057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.P.; Leung, L.W.; Hartman, A.L.; Martinez, O.; Shaw, M.L.; Carbonnelle, C.; Volchkov, V.E.; Nichol, S.T.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus VP24 Binds Karyopherin α1 and Blocks STAT1 Nuclear Accumulation. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5156–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, S.; Motiam, A.E.; Seoane, R.; Preitakaite, V.; Bouzaher, Y.H.; Gómez-Medina, S.; Martín, C.S.; Rodríguez, D.; Rejas, M.T.; Baz-Martínez, M.; et al. Regulation of the Ebola Virus VP24 Protein by SUMO. J. Virol. 2019, 94, e01687-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baz-Martínez, M.; El Motiam, A.; Ruibal, P.; Condezo, G.N.; de la Cruz-Herrera, C.F.; Lang, V.; Collado, M.; San Martín, C.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Muñoz-Fontela, C.; et al. Regulation of Ebola virus VP40 matrix protein by SUMO. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiro, R.G. Protein glycosylation: Nature, distribution, enzymatic formation, and disease implications of glycopeptide bonds. Glycobiology 2002, 12, 43R–56R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, K.J.; Varki, A.; Haltiwanger, R.S.; Kinoshita, T. Cellular Organization of Glycosylation. In Essentials of Glycobiology, 4th ed.; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Mohnen, D., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., et al., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Pan, W.; Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Dai, J. Glycosylation of viral proteins: Implication in virus–host interaction and virulence. Virulence 2022, 13, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, G.; Dong, W. The Importance of Glycans of Viral and Host Proteins in Enveloped Virus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 638573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, A.L.; Clarke, E.C.; Anaya, E.; Merrill, D.; Yarborough, S.; Anthony, S.M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Merle, C.; Theisen, M.; Bradfute, S.B. Comparison of N- and O-linked glycosylation patterns of ebolavirus glycoproteins. Virology 2017, 502, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, E.J.; Linstedt, A.D. Site-specific glycosylation of Ebola virus glycoprotein by human polypeptide GalNAc-transferase 1 induces cell adhesion defects. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 19866–19873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennemann, N.J.; Walkner, M.; Berkebile, A.R.; Patel, N.; Maury, W. The Role of Conserved N-Linked Glycans on Ebola Virus Glycoprotein 2. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, S204–S209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Frabutt, D.A.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, S.; Xiang, S.-H.; et al. Mechanistic understanding of N-glycosylation in Ebola virus glycoprotein maturation and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5860–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schornberg, K.; Matsuyama, S.; Kabsch, K.; Delos, S.; Bouton, A.; White, J. Role of Endosomal Cathepsins in Entry Mediated by the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4174–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Liu, J.; Hua, F. Protein acylation: Mechanisms, biological functions and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Hou, D.; Zheng, C. Investigation of Protein Lysine Acetylation in Antiviral Innate Immunity. In Antiviral Innate Immunity; Zheng, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama, D.; Ohmi, N.; Saitoh, A.; Makiyama, K.; Morioka, M.; Okazaki, H.; Kuzuhara, T. Acetylation of lysine residues in the recombinant nucleoprotein and VP40 matrix protein of Zaire Ebolavirus by eukaryotic histone acetyltransferases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 504, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.; Chen, M.; Yan, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Jin, D.; Yin, L.; Chen, M.; Qin, Y. P300-mediated NEDD4 acetylation drives ebolavirus VP40 egress by enhancing NEDD4 ligase activity. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wei, Z.; Shang, P.; Hu, S.; Chen, L.; Niu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gan, M.; Shen, L.; Zhu, L.; et al. The function and mechanism of protein acylation in the regulation of viral infection. Virulence 2025, 16, 2530171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, A.; Xu, J. Protein Palmitoylation Modification During Viral Infection and Detection Methods of Palmitoylated Proteins. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 821596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funke, C.; Becker, S.; Dartsch, H.; Klenk, H.D.; Muhlberger, E. Acylation of the Marburg virus glycoprotein. Virology 1995, 208, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Watanabe, S.; Takada, A.; Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus glycoprotein: Proteolytic processing, acylation, cell tropism, and detection of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, M.I.; Xia, H.; Aguilera-Aguirre, L.; Hage, A.; van Tol, S.; Shan, C.; Xie, X.; Sturdevant, G.L.; Robertson, S.J.; McNally, K.L.; et al. Envelope protein ubiquitination drives entry and pathogenesis of Zika virus. Nature 2020, 585, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus | Period (Year) | Country | Human Confirmed Cases | Case Fatality Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUDV | 1976 | South Sudan | 284 | 53% |

| EBOV | 1976 | DRC | 318 | 88% |

| EBOV | 1977 | DRC | 1 | 100% |

| SUDV | 1979 | South Sudan | 34 | 64% |

| EBOV | 1994 | Gabon | 52 | 52% |

| TAFV | 1994 | Cote d’Ivoire | 1 | 0% |

| EBOV | 1995 | DRC | 315 | 81% |

| EBOV | 1996 | Gabon | 31 | 67% |

| EBOV | 1996 | Gabon | 60 | 75% |

| SUDV | 2000–2001 | Uganda | 425 | 53% |

| EBOV | 2001–2002 | Gabon | 65 | 80% |

| EBOV | 2001 | ROC | 59 | 75% |

| EBOV | 2003 | ROC | 143 | 90% |

| EBOV | 2003 | ROC | 35 | 83% |

| SUDV | 2004 | South Sudan | 17 | 41% |

| EBOV | 2005 | ROC | 12 | 83% |

| EBOV | 2007 | DRC | 264 | 71% |

| BDBV | 2007 | Uganda | 149 | 25% |

| EBOV | 2008–2009 | DRC | 32 | 47% |

| SUDV | 2011 | Uganda | 1 | 100% |

| BDBV | 2012 | DRC | 62 | 55% |

| SUDV | 2012 | Uganda | 24 | 71% |

| SUDV | 2012 | Uganda | 7 | 57% |

| EBOV | 2013–2016 | Guinea | 28,656 | 40% |

| EBOV | 2014 | DRC | 69 | 71% |

| EBOV | 2017 | DRC | 8 | 50% |

| EBOV | 2018 | DRC | 54 | 61% |

| EBOV | 2018–2020 | DRC | 3470 | 66% |

| EBOV | 2020 | DRC | 130 | 42% |

| EBOV | 2021 | DRC | 12 | 50% |

| EBOV | 2021 | Guinea | 23 | 52% |

| EBOV | 2021 | DRC | 11 | 55% |

| EBOV | 2022 | DRC | 5 | 100% |

| EBOV | 2022 | DRC | 1 | 100% |

| SUDV | 2022 | Uganda | 164 | 47% |

| SUDV | 2025 | Uganda | 12 | 40% |

| EBOV | 2025 | DRC | 42 * | 65% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno-Contreras, J.; Peñaflor-Tellez, Y.; Rajsbaum, R. The Role of Posttranslational Modifications During Ebola Virus Infection. Viruses 2025, 17, 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121640

Moreno-Contreras J, Peñaflor-Tellez Y, Rajsbaum R. The Role of Posttranslational Modifications During Ebola Virus Infection. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121640

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Contreras, Joaquin, Yoatzin Peñaflor-Tellez, and Ricardo Rajsbaum. 2025. "The Role of Posttranslational Modifications During Ebola Virus Infection" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121640

APA StyleMoreno-Contreras, J., Peñaflor-Tellez, Y., & Rajsbaum, R. (2025). The Role of Posttranslational Modifications During Ebola Virus Infection. Viruses, 17(12), 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121640