Abstract

Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), responsible for chickenpox and herpes zoster, has emerged as a significant contributor to cerebrovascular disease. Mounting evidence indicates that VZV reactivation may precipitate ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke through mechanisms of viral vasculopathy, immune evasion, and vascular inflammation. While antiviral therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment, several adjunctive regimens exhibit encouraging results in controlling endothelial inflammatory response. This targeted review synthesized findings from 31 studies, including clinical cohorts, in vitro models, and pathological analyses, to evaluate the relationship between VZV and stroke, with emphasis on treatment management beyond antivirals. Evidence demonstrates that VZV antigens are frequently detected within cerebral arteries, where they induce transmural inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and thrombosis, thereby increasing stroke risk, particularly in the weeks following herpes zoster. Adjunctive therapies such as corticosteroids, statins, and resveratrol show promise in mitigating vascular inflammation, though clinical validation is limited. Preventive measures, especially zoster vaccination, significantly reduce herpes zoster incidence and may lower subsequent stroke risk, yet global uptake remains insufficient. Collectively, the data underscore the need for improved diagnostic tools, combination treatment strategies, and expanded vaccination programs to address the substantial public health burden of VZV-associated stroke.

1. Introduction

Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), a highly contagious human herpesvirus, is nearly ubiquitous worldwide, with over 90% of adults showing serologic evidence of prior infection, particularly in temperate regions [1]. VZV manifests primarily as chickenpox in children prior to adolescence, while herpes zoster (shingles), caused by viral reactivation, disproportionately impacts older and immunocompromised populations. Global estimates suggest that herpes zoster is now increasing due to aging populations and immune suppression despite access to antivirals, with lifetime risk of herpes zoster at approximately 30%, making it one of the most common viral reactivations worldwide [2,3]. Despite estimated direct medical costs reaching $2.4 billion annually in the United States, with comparable cost levels in Europe and Asia, only 18% of countries worldwide have implemented universal VZV vaccination programs, with shingles vaccine uptake remaining low in regions with high disease prevalence [3]. However, accumulating evidence highlights a potentially broader disease spectrum that may include serious vascular and neurological complications, such as ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, even in the absence of rash [4,5].

VZV’s neurotropism and potential vasculotropic interactions implicate it in a growing number of stroke syndromes, especially among vulnerable populations [5,6]. Meta-analyses report the first couple of weeks post-zoster as the period of increased occurrence, which remains marginally elevated one year post-infection [7]. Ophthalmic zoster, in particular, carries a higher cerebrovascular risk, with a relative stroke risk often exceeding twice that of more distant infections due to anatomical proximity to cerebral vessels [8,9]. Pediatric populations are also at higher risk of focal cerebral arteriopathy, frequently involving the middle cerebral artery, following primary varicella infection [10,11]. Given the high global prevalence of latent VZV infection and the public health burden of stroke, elucidating this relationship is critical [6].

Both experimental and pathological studies provide mechanistic insights into VZV vasculopathy. Analyses on preclinical models showed that the transport of alphaherpesviruses, such as pseudorabies virus, from ganglia to vasculature, depends on axonal kinesin motors and specific viral proteins such as gE, gI, and US9 [12]. Findings from human studies support this trajectory, with post-mortem analyses and blood vessel biopsies frequently revealing the presence of VZV DNA, RNA, or protein antigens within affected arteries [13,14,15]. Vascular damage resulting from VZV infection has been found to involve transmural inflammation, intimal hyperplasia, endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis, and arterial remodeling [16,17,18]. These pathological features result in a wide range of vascular events such as large artery atherosclerotic stroke and small vessel disease strokes, aneurysms, and intracerebral hemorrhages [16,17,18]. Studies using black-blood MRI have further enhanced diagnostic accuracy by revealing inflammatory changes within blood vessel walls [9,19]. Despite the availability of novel and more advanced diagnostic tools, confirmation of a causative relationship between VZV and stroke remains elusive in many cases. The absence of classic symptoms, such as rashes, CSF pleocytosis, or detectable viral DNA, further complicates accurate diagnosis. Anti-VZV antibodies within the CSF are the most accurate and reliable marker of ongoing infection and should be prioritized in suspected cases of VZV vasculopathy [20]. Other promising biomarkers include thrombotic markers such as D-dimer and β-thromboglobulin, which may help guide adjunctive therapies but do not confirm VZV presence or interaction [14]. Systemic inflammation-related biomarkers are also relevant, as elevations in IL-6, TNF-α, and other proinflammatory cytokines after VZV reactivation align with the recognized prothrombotic state that accompanies herpes zoster [15].

While intravenous acyclovir, often accompanied by corticosteroids to mitigate inflammation, remains a central piece of the arsenal used to combat VZV infection and recurrence, a growing body of research has explored alternative and adjunctive treatments to manage VZV infection and its complications [21,22,23]. Both live-attenuated and recombinant subunit zoster vaccines significantly reduce the incidence and severity of herpes zoster and its long-term complication, postherpetic neuralgia [23,24]. For exposed immunocompromised patients, passive immunization with varicella zoster immune globulin has been shown to offer temporary protection and can prevent severe disease progression [24,25]. Anti-inflammatory therapies, such as corticosteroids, have been used as adjuncts to reduce acute neuritis and may help mitigate the vascular inflammation linked to VZV-associated stroke, although their use remains controversial due to immunosuppressive risks [18,26]. Compounds such as resveratrol have been proposed as potential neuroprotective agents against VZV-induced vasculopathy, though clinical validation of resveratrol is still pending [27,28,29]. Management of postherpetic neuralgia also includes neuromodulatory treatments such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants, which can be more effective than antivirals alone for long-term pain control [30,31]. Additionally, emerging genetic approaches such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and locked nucleic acid antisense therapies are being investigated to directly inhibit VZV gene expression and viral replication, offering promising future avenues beyond pharmacologic suppression [32,33]. Together, these therapies represent an evolving landscape of multi-modal strategies for managing VZV infection beyond traditional antivirals [34,35].

The clinical, pathological, and mechanistic evidence for a causal relationship between VZV and stroke is growing; however, diagnostic challenges and treatment resistance persist. We performed a targeted literature review to examine the relationship between VZV and stroke, with emphasis on epidemiology, pathophysiological mechanisms, experimental and clinical models, and therapeutic strategies, especially among non-antivirals. We also considered non-antiviral management approaches, including agents with anti-inflammatory or vasoprotective effects.

2. Materials and Methods

Literature research was conducted using PubMed, Embase, and Scopus up to November 2025, using the keywords “Varicella Zoster Virus” AND “stroke” AND “vasculopathy” OR “anti-virals”.

The inclusion criteria focused on studies that (a) reported clinical, experimental, or imaging evidence linking VZV to stroke or cerebrovascular disease; (b) investigated therapeutic strategies, including antivirals, non-antiviral agents (e.g., corticosteroids, immunomodulators), or vaccines; (c) examined experimental models (in vitro, in vivo, or clinical) addressing VZV replication, vascular inflammation, or neurological outcomes; and (d) explored mechanistic pathways such as immune suppression, endothelial dysfunction, vascular remodeling, and inflammatory responses. Eligible studies included original research on human subjects, animal models, and cell-based assays, provided they were published in English and in peer-reviewed journals. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on dermatologic manifestations, lacked relevance to vascular or neurological outcomes, involved non-VZV viruses without comparison to VZV, or were unavailable in full text. Only English studies were included, while duplicates were eliminated. Three independent reviewers screened articles and resolved disagreements through discussion and consensus. The final analysis aimed to synthesize multidisciplinary evidence to inform future research and clinical management of VZV-related stroke.

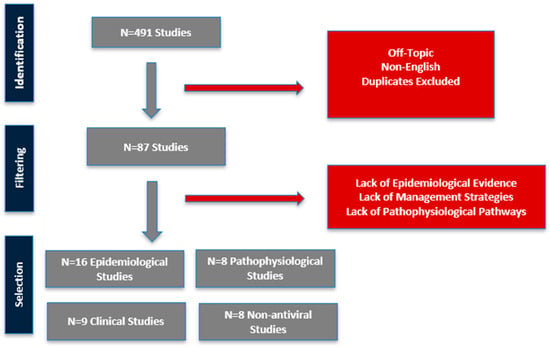

The initial database search returned 491 results, from which 404 were excluded based on titles and abstracts for being off-topic, duplicative, or non-original. Full-text review of 87 articles led to the final inclusion of 41 studies that directly addressed one or more of the four research domains: (1) epidemiological studies, (2) pathophysiological pathways linking VZV to stroke, (3) clinical models of infection and (4) non-antiviral strategies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow for filtering included studies.

3. Results

The initial database search returned 491 records, which were systematically filtered through title, abstract, and full-text review. This process culminated in the inclusion of 41 studies that directly addressed the objectives concerning the VZV–stroke relationship, its underlying mechanisms, and potential management strategies. The findings from these studies are synthesized and organized into four distinct tables for detailed analysis.

Table 1 consolidates evidence from 16 epidemiological studies conducted across North America, Europe, and Asia, providing robust, population-level data on the association between VZV infection and cerebrovascular events [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Table 1.

Epidemiological Studies Linking VZV–Stroke.

The most consistent finding across these studies is a time-dependent escalation in stroke risk following an episode of HZ. A seminal systematic review and meta-analysis [36], encompassing 27 individual studies, quantified this risk with precision, demonstrating a peak relative risk of 1.80 within the first 14 days post-HZ [36]. This risk remained significantly elevated over time. This acute risk phase was corroborated by large-scale national cohort studies. For instance, a Danish cohort of 4.6 million adults reported a 126% increase in stroke risk within the first two weeks, while a US study of veterans found 93% higher risk of stroke within 30 days of a zoster diagnosis [37,40].

Beyond the immediate period, several studies indicate that the risk may persist long-term. A prospective cohort of over 200,000 US health professionals reported elevated risk of cardiac pathology post-infection, peaking at 5–8 years post-infection and remaining elevated for up to 12 years [44]. The epidemiological data also reveal important high-risk subgroups. Immunocompromised populations, particularly those with HIV, face a substantially heightened risk, i.e., evidence of CNS VZV reactivation in 37% of HIV−positive stroke patients in South Africa [38]. Furthermore, contrary to the assumption that age is the primary risk factor, several studies indicate that younger individuals experience a disproportionately higher relative risk. Sundström et al. reported an incidence rate ratio in patients aged 0–39 years vastly higher than that observed in older cohorts [52]. This trend was echoed in a Korean study in patients under 40 [47]. The risk extends to pediatric populations following primary varicella infection, reporting elevated incidence rate during the first half of the year following chickenpox [43].

Recent studies provide more granular insights into whether VZV infection or reactivation confers different risks for ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke. A landmark retrospective cohort analysis from the UK reported that ischemic stroke was more commonly reported (33%) compared to hemorrhagic stroke (6%) [50]. Similarly, other studies found that the majority of cerebrovascular events occurring after infection were ischemic in nature [4,41]. Temporal patterns also diverge as the incidence of ischemic stroke peaks within the first month after zoster and gradually declines thereafter, while hemorrhagic stroke tends to appear later [4,48].

Table 2 synthesizes findings from 8 clinicopathologic studies that move beyond association to delineate the precise mechanisms by which VZV induces cerebrovascular disease [53,54,55,56,57,58].

Table 2.

Pathophysiological Studies Linking VZV–Stroke.

A cornerstone of the causal argument is the repeated direct detection of the virus within affected cerebral arteries. The foundational work by Gilden et al. provided the first clear evidence, identifying VZV DNA and antigens in the cerebral arteries without the presence of a skin rash [53]. Subsequent research has consistently replicated this finding [14]. The proposed pathogenic trajectory involves the reactivated virus traveling transaxonally from cranial nerve ganglia (particularly the trigeminal ganglion) to the adventitia (outer layer) of cerebral arteries [54,56]. From this initial site of infection, the virus instigates a transmural inflammatory cascade, spreading inward and causing a characteristic vasculopathy. The histopathological hallmarks of this process, confirmed in post-mortem analyses, include intimal hyperplasia, medial smooth muscle loss, and granulomatous inflammation, often with multinucleated giant cells.

These structural changes have direct clinical consequences, leading to arterial stenosis, thrombosis, aneurysm formation, and ultimately, vessel rupture or occlusion, manifesting as ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Advanced imaging techniques, particularly high-resolution vessel wall MRI, have allowed for the in vivo visualization of these inflammatory changes, providing a radiological correlate to the pathological findings [19,58].

A critical and sophisticated aspect of VZV vasculopathy is the virus’s ability to evade host immune surveillance. Experimental work reported that post-infection upregulation of human cerebral vascular adventitial fibroblasts leads to the downregulation of key immune molecules, including Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) and Major Histocompatibility Complex class I (MHC-I) [55]. This impairment of immune clearance mechanisms allows for viral persistence within the arterial wall, fostering a state of chronic inflammation and vascular remodeling.

Table 3 compiles data from 9 clinical studies and reviews that evaluate the effectiveness of various interventions on stroke-related outcomes, revealing a nuanced and sometimes contradictory picture [40,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

Table 3.

Clinical Studies Linking VZV-Related Stroke and Antiviral Treatments.

The efficacy of antiviral therapy in preventing stroke post-HZ is a subject of ongoing debate. While in vitro data and clinical practice support their use for treating active infection, their role in mitigating long-term vascular complications is less clear. A meta-analysis of 12 observational studies concluded that antiviral treatment did not confer a significant protective effect against stroke [63]. This contrasts with findings from Kawai et al., who analyzed a national database of millions and found that antiviral prescription within 7 days of HZ onset was associated with an approximately 21% reduction in stroke risk, indicating that timing may be a critical factor [61]. In pediatric populations, the evidence is also mixed; Lewandowski et al. found no clear evidence that antiviral treatment altered the disease course in immunocompetent children with CNS VZV disease [66].

In contrast to the ambiguous data on antivirals, the protective effect of vaccination is far more consistent and compelling. The same meta-analysis by Jia et al. found that zoster vaccination led to a 22% lower probability of stroke risk [63]. This positions vaccination as the most effective primary prevention strategy for VZV-associated stroke, a conclusion strongly supported by additional studies [64].

For patients who have already developed VZV vasculopathy, combination therapy appears to be key. Promising evidence for the adjunctive use of corticosteroids comes from case series that documented three young men with VZV vasculitis and intracranial stenoses [62]. All three patients showed significant or near-complete resolution of arterial stenoses after a prolonged course of valacyclovir combined with a slow taper of oral prednisolone, with no recurrent strokes. However, the limitations of this approach are highlighted by other case reports, which detailed a fatal outcome despite combined antiviral and high-dose steroid therapy, underscoring the potential for poor prognosis in severe cases, particularly in immunocompromised hosts [65].

Table 4 includes 8 studies investigating compounds that operate outside the traditional antiviral mechanism, highlighting a diverse and evolving research frontier [28,67,68,69,70,71].

Table 4.

Studies on VZV-related Stroke and Non-Antiviral Compounds.

The most clinically established non-antiviral approach is the use of immunomodulatory agents, specifically corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, methylprednisolone) [28,62,69,70]. These are widely used as adjuncts to antivirals in severe VZV vasculopathy to suppress the damaging inflammatory response within the vessel wall, although their use is tempered by concerns of immunosuppression.

Beyond repurposed drugs, significant research is focused on novel agents. Several natural compounds, including Myricetin, Apigenin-4′-glucoside, and Abyssinone V, have been identified through in silico modeling as potential inhibitors of VZV thymidine kinase, a key viral enzyme [67]. However, these remain in the preclinical investigation stage. Another promising avenue is host-directed therapy. The natural polyphenol Resveratrol [71], with its known vasodilatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, has been proposed as a potential neuroprotective agent in VZV-induced vasculopathy, though clinical validation is pending.

4. Discussion

A growing body of research underscores an intricate relationship between VZV infection/reactivation and stroke. Epidemiological studies consistently show that individuals who experience herpes zoster have a significantly elevated risk of cerebrovascular events, especially in the early period following the infection [38]. Available epidemiological datasets regularly demonstrate that the association between VZV and stroke is driven primarily by ischemic events, whereas hemorrhagic strokes occur far less frequently [4]. Meta-analyses report that stroke incidence is higher in the first two weeks after a zoster episode, with the excess risk gradually attenuating over subsequent months [38]. This temporal pattern strongly suggests a causal trigger: VZV reactivation acts as a stroke precipitant, particularly in the short term. Clinical observations mirror these findings. Case series have documented strokes occurring within days to weeks of shingles, including instances where patients developed vasculitic stroke in the absence of dermatological signs [72]. Such reports highlight that VZV’s impact on the vasculature can manifest covertly, complicating straightforward clinical recognition. Taken together, epidemiological and clinical evidence converge to identify VZV as a non-traditional yet important risk factor for stroke. Notably, this association spans diverse patient populations: older adults with shingles comprise the largest at-risk group, but pediatric strokes are also well documented [38].

Mechanistic studies provide a biological framework explaining how VZV induces cerebrovascular damage. VZV is neurotropic and vasculotropic: after reactivation in cranial nerve ganglia, the virus can spread transaxonally to infect cerebral arteries, particularly those innervated by branches of the trigeminal nerve [72]. Pathological analyses confirm direct viral invasion of arterial walls—VZV DNA, proteins, and even viral inclusion bodies have been found in intracranial arteries from stroke patients with prior zoster [72]. Within the vessel, VZV triggers a vasculitis characterized by transmural inflammation and profound structural remodeling. These changes lead to marked intimal thickening and luminal narrowing, predisposing to thrombosis and ischemia [72]. VZV reactivation provokes a systemic inflammatory response with elevated cytokines and can generate prothrombotic autoantibodies and immune complexes [72]. These factors may promote a hypercoagulable state and endothelial dysfunction, compounding the risk of stroke.

Human dorsal root ganglion neurons and in vivo models have shown that VZV reactivation in sensory ganglia leads to anterograde transport of virus along axons toward peripheral and cerebral arteries [73,74,75]. The viral glycoprotein complex gE–gI plays a critical role in sorting virions into neuronal processes and enabling efficient cell-to-cell spread [73,74,75]. Although axonal transport mechanisms are well characterized in other alphaherpesviruses such as HSV-1 and pseudorabies virus—where US9, gE/gI, and kinesin motors mediate anterograde trafficking—the precise molecular machinery used by VZV remains less fully defined [73,74,75]. Once VZV reaches perivascular nerve terminals, studies in human brain vascular tissue demonstrate that the virus infects adventitial fibroblasts, which subsequently activate endothelial cells, release inflammatory mediators, and promote transmural spread, providing a mechanistic basis for VZV vasculopathy [73,74,75]. Jones et al. demonstrated that VZV infection of human brain vascular adventitial fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and lung fibroblasts leads to a marked reduction in PD-L1 and MHC-I surface expression within 72 h [76]. Importantly, this suppression occurs post-transcriptionally, as PD-L1 mRNA levels remain unchanged, implicating virally induced protein destabilization or altered trafficking [76]. This reduction in MHC-I disrupts CD8+ T-cell recognition of infected vascular cells, enabling viral persistence in the arterial wall [76]. In contrast, the loss of PD-L1 removes a key inhibitory checkpoint that normally limits T-cell activation, resulting in heightened local cytokine release (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α) and sustained vascular inflammation [76]. Hence, VZV causes a paradoxical state of simultaneous immune evasion and unrestrained inflammation, which supports chronic vasculopathy.

From a management standpoint, identifying VZV involvement is crucial because it directs specific therapy. The mainstay treatment for VZV vasculopathy is antiviral therapy. High-dose intravenous acyclovir is recommended to suppress VZV replication [64]. This is often initiated empirically in suspected cases, given the disease’s severity and the time sensitivity of stroke management. Adjunctive corticosteroids are commonly co-administered with antivirals, aiming to reduce vessel wall inflammation and swelling [64]. The adjunctive use of corticosteroids in VZV vasculopathy presents a critical risk-benefit dilemma centered on the balance between suppressing harmful arterial inflammation and risking immunosuppression-related complications. The anti-inflammatory benefit, demonstrating resolution of intracranial stenoses with combined antiviral and steroid therapy, must be weighed against the significant hazard of impaired viral clearance and opportunistic infections [62]. This risk is not uniform, as it is considered acceptable in immunocompetent patients with severe, progressive large-vessel disease, where the threat of infarction is imminent, but is unacceptably high in immunocompromised hosts, where steroid use may precipitate fatal outcomes [65]. Consequently, a pragmatic approach is to reserve corticosteroid therapy for immunocompetent adults, initiating treatment with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone alongside antivirals. Its use in immunocompromised patients or in mild or pediatric cases should be avoided or undertaken with extreme caution under close monitoring, acknowledging that current studies are based on low-level evidence. Finally, it is important to note that standard anticoagulant therapy alone does nothing to eradicate the underlying virus; thus, without antivirals, ongoing arterial injury may continue. This is illustrated by the observation that patients who do not receive antiviral treatment for zoster have higher rates of stroke than those who are treated, all else being equal [61]. Early antiviral therapy during a zoster episode led to a lower probability of stroke, supporting the practice of prompt antiviral initiation not just to hasten rash resolution but also as a stroke-preventive measure [61].

The long-term prognosis of VZV-associated stroke is variable. Studies show that stroke risk remains elevated for several months after zoster, with the highest recurrence risk occurring within the first 4–12 weeks [7,36]. Nevertheless, meaningful neurological recovery is feasible, and even patients with prolonged, multifocal VZV vasculopathy have demonstrated cognitive and gait improvement after timely antiviral therapy, including cases treated successfully after more than two years of ongoing infarcts [28]. Persistent sequelae—such as visual loss, cognitive impairment, and focal deficits—may occur but can be mitigated through antiviral treatment, risk-factor control, and standard post-stroke rehabilitation [77]. Early recognition and antiviral therapy remain the strongest determinants of long-term outcome in VZV-associated stroke.

Preventive measures, particularly vaccination, are at the forefront of reducing this VZV–stroke burden. A large Veterans Affairs study found that patients who had received zoster vaccines had significantly lower stroke rates following VZV infection [37]. In that study, prior vaccination was associated with over 40% lower risk of stroke after administering the recombinant vaccine and about a 23% reduction for the live vaccine [37]. Considering such insights, health policy should emphasize improving zoster vaccine uptake. Overall, preventive approaches—via vaccination and secondary prevention via early antiviral treatment—form a twin strategy to diminish the impact of VZV-related strokes on society.

To date, no dedicated randomized controlled trials have been conducted to determine the optimal treatment regimen for VZV-related stroke. Questions remain about the ideal duration of antiviral therapy, the role of combination therapy, and the management of steroid-responsive inflammation. Future studies should explore whether prolonged antiviral courses or suppressive antiviral prophylaxis could prevent recurrent strokes in high-risk patients. The potential benefit of anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory adjuncts, including aspirin, statins, and calcineurin inhibitors, also needs clearer evidence and proper integration into therapeutic protocols. Exploratory approaches such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and antisense technologies aimed at VZV could one day enable eradication of latent VZV or suppression of viral gene expression [32,33]. Additionally, drugs like resveratrol that exhibit both antiviral activity and neurovascular protective effects are being investigated as potential adjuncts or prophylactics against VZV-induced stroke [71].

This work has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the inherent heterogeneity of the included studies—encompassing in vitro models, systematic reviews, and human case reports—precludes a formal meta-analysis, thus limiting the ability to quantify the overall strength of the evidence. The heavy reliance on in vitro data and the scarcity of robust, representative human studies for VZV vasculopathy create a significant translational gap and mean that the promising mechanistic findings and novel therapeutic candidates remain largely theoretical. Furthermore, clinical evidence is often derived from reports and small cohort studies, which are susceptible to publication bias and lack the controlled rigor of randomized trials; consequently, the efficacy of adjunctive therapies like corticosteroids and statins is suggested by anecdotal evidence rather than proven by high-quality data. Finally, while we underscore the paramount importance of immunization, the global inequity in vaccine access means the findings may not be generalizable to all populations.

5. Conclusions

Varicella Zoster Virus is a potent and direct trigger of cerebrovascular disease through a mechanism of direct viral invasion and inflammation of cerebral arteries. We consolidate the multi-faceted evidence, from epidemiology and pathology to in vitro models, that establishes this intricate relationship.

The clinical implications are profound. A high index of suspicion for VZV vasculopathy is warranted in cases of cryptogenic stroke, especially in the elderly and immunocompromised, and even in children, even in the absence of a characteristic rash. Diagnosis should prioritize CSF serology for VZV-specific antibodies, supplemented by advanced vascular imaging like high-resolution vessel wall MRI. Treatment must evolve beyond monotherapy with antivirals to consider combination strategies that address the concomitant inflammatory cascade, though more clinical trials are needed to define optimal protocols.

Ultimately, prevention remains the most effective and sustainable strategy. The recombinant zoster vaccine, with its high efficacy and favorable safety profile, offers a powerful tool to mitigate a significant portion of the burden of VZV-related stroke. Future research should focus on validating novel non-antiviral adjuncts in clinical trials and further elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms of VZV-induced vascular injury to identify new therapeutic targets. By integrating vaccination, improved diagnostics, and multi-modal treatment, the medical community can effectively confront the significant and often preventable cerebrovascular complications of VZV infection.

Author Contributions

K.A. and A.L. conceived the idea; A.L., L.E.S., K.A., G.N. and C.G. performed the literature search; A.L. and L.E.S. wrote the manuscript and drew the figures; K.A., G.N. and C.G. critically corrected the manuscript; K.A. oversaw the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; Deng, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Global, regional, and national burden of varicella-zoster infections in adults aged 70 years and older from 1997 to 2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, A.M. Varicella-zoster virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 9, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streng, A.; Liese, J.G. Fifteen years of routine childhood varicella vaccination in the United States—Strong decrease in the burden of varicella disease and no negative effects on the population level thus far. Transl. Pediatr. 2014, 3, 268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, F.; Yang, B.; Duan, R. Herpes zoster and the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.A.; Gilden, D. The relationship between herpes zoster and stroke. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2015, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, R.A.B.; Chandiraseharan, V.K.; Jasper, A.; Sebastian, T.; Gujjarlamudi, C.; Sathyendra, S.; Zachariah, A.; Abraham, A.M.; Sudarsanam, T.D. Varicella Zoster Virus Infection of the Central Nervous System—10 Year Experience from a Tertiary Hospital in South India. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2017, 20, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; Ruckenstein, J.; Richardson, K. A meta-analysis of stroke risk following herpes zoster infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antia, C.; Persad, L.; Alikhan, A. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with associated vasculopathy causing stroke. Dermatol. Online J. 2017, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Poonawala, H.; Keay, S.K.; Serulle, Y.; Steven, A.; Gandhi, D.; Cole, J.W. Varicella-zoster virus vasculopathy: A case report demonstrating vasculitis using black-blood MRI. J. Neurol. Neurophysiol. 2015, 6, 1000342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, L.; Gentilomo, C.; Sartori, S.; Calderone, M.; Simioni, P.; Laverda, A.M. Varicella and stroke in children: Good outcome without steroids. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. 2011, 17, E127–E130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, H.; Rodriguez, W. Role of varicella-zoster virus in stroke syndromes. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000, 19, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, C.; Shaban, A.; Fullerton, H.J. Common features between stroke following varicella in children and stroke following herpes zoster in adults: Varicella-zoster virus in trigeminal ganglion. In Varicella-Zoster Virus: Genetics, Pathogenesis and Immunity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- González-Suárez, I.; Fuentes-Gimeno, B.; Ruiz-Ares, G.; Martínez-Sánchez, P.; Diez-Tejedor, E. Varicella-zoster virus vasculopathy. A review description of a new case with multifocal brain hemorrhage. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 338, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T.; Toi, S.; Toda, K.; Uchiyama, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Iijima, M.; Shimizu, Y.; Kitagawa, K. Ischemic stroke due to virologically-confirmed varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: A case series. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmon, A.M.; Como, C.N.; Bubak, A.N.; Mescher, T.; Jones, D.; Nagel, M.A. Varicella Zoster Virus Alters Expression of Cell Adhesion Proteins in Human Perineurial Cells via Interleukin 6. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstrand, R.; Portela, R.; Juneau, R.; Okafor, C.; Watts, R. Hemorrhagic Stroke Due to Varicella Zoster Virus Vasculopathy. Cureus 2023, 15, e36604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Tiwari, A.; Qavi, A. Recurrent stroke in varicella zoster associated vasculopathy. Nepal J. Neurosci. 2021, 18, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell II, D.R.; Patel, S.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Lopez, F.A. Varicella-zoster virus vasculopathy: The growing association between herpes zoster and strokes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 350, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Lachanis, S.; Magoufis, G.; Safouris, A.; Kargiotis, O.; Stamboulis, E. High-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging in varicella-zoster virus vasculitis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, e74–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, M.A.; Bubak, A.N. Varicella Zoster Virus Vasculopathy. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218 (Suppl. 2), S107–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, A.; Studahl, M. Varicella-zoster virus infections of the central nervous system–Prognosis, diagnostics and treatment. J. Infect. 2015, 71, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Kawano, H.; Amano, T.; Hirano, T. Acute stroke caused by progressive intracranial artery stenosis due to varicella zoster virus vasculopathy after chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma. Intern. Med. 2021, 60, 1769–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Kim, D. Long COVID Syndrome: Clinical Presentation, Pathophysiology, Management. Keimyung Med. J. 2023, 42, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, J.M. Varicella-zoster virus. In Clinical Infectious Disease, 2nd ed.; Schlossberg, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 1226–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, T. Herpes virus infections in immunosuppressed patients. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus: Prevention and therapy. Fortschritte Med. 1989, 107, 537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Balfour, H.H., Jr. Varicella-zoster virus infections in the immunocompromised host. Natural History and Treatment. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 1991, 80, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hakami, M.A.; Khan, F.R.; Abdulaziz, O.; Alshaghdali, K.; Hazazi, A.; Aleissi, A.F.; Abalkhail, A.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Alhazmi, A.Y.M.; Kukreti, N.; et al. Varicella-zoster virus-related neurological complications: From infection to immunomodulatory therapies. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, B.; Nagel, M.A.; Mahalingam, R.; Cohrs, R.; Schmid, D.S.; Gilden, D. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: A treatable form of rapidly progressive multi-infarct dementia after 2 years’ duration. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 323, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Song, F.; Zuo, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, L.; Ta, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, J. Resveratrol: A potential medication for the prevention and treatment of varicella zoster virus-induced ischemic stroke. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Current scenario and future applicability of antivirals against herpes zoster. Korean J. Pain 2023, 36, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Khan, F.; Ramirez-Fort, M.K.; Downing, C.; Tyring, S.K. Varicella zoster: An update on current treatment options and future perspectives. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Bisht, P.; Kinchington, P.R.; Goldstein, R.S. Locked-nucleotide antagonists to varicella zoster virus small non-coding RNA block viral growth and have potential as an anti-viral therapy. Antivir. Res. 2021, 193, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W.; Yee, M.B.; Goldstein, R.S.; Kinchington, P.R. Antiviral targeting of varicella zoster virus replication and neuronal reactivation using CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage of the duplicated open reading frames 62/71. Viruses 2022, 14, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.A. Varicella Zoster Virus and Stroke. In Primer on Cerebrovascular Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 567–570. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon, A.A.; Breuer, J.; Cohen, J.I.; Cohrs, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; Gilden, D.; Grose, C.; Hambleton, S.; Kennedy, P.G.E.; Oxman, M.N. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Cui, L.; Zhang, X. Stroke risk after varicella-zoster virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. NeuroVirol. 2023, 29, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameswaran, G.I.; Wattengeil, B.A.; Chua, H.C.; Swiderek, J.; Fuchs, T.; Carter, M.T.; Goode, L.; Doyle, K.; Mergenhagen, K.A. Increased stroke risk following herpes zoster infection and protection with zoster vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e1335–e1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, G.; Naidoo, M.; McMullen, K.; Stanley, A.; Bryer, A.; van der Westhuizen, D.; Bateman, K.; Hardie, D.R. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation is frequently detected in HIV-infected individuals presenting with stroke. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 2675–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, Z.F.; Hamad, B.J. Demographic study of varicella zoster virus in cerebrospinal fluid of stroke patients in Thi-Qar Province. Univ. Thi-Qar J. Sci. 2024, 11, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, N.; Basit, S.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Pasternak, B.; Munch, T.N.; Nielsen, L.P.; Melbye, M. The short- and long-term risk of stroke after herpes zoster: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M.; Minassian, C.; Smeeth, L.; Thomas, S.L. Risk of stroke following herpes zoster: A self-controlled case-series study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Ho, J.D.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, H.C. Increased risk of stroke after a herpes zoster attack: A population-based follow-up study. Stroke 2009, 40, 3443–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.L.; Minassian, C.; Ganesan, V.; Langan, S.M.; Smeeth, L. Chickenpox and risk of stroke: A self-controlled case series analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 58, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curhan, S.G.; Kawai, K.; Yawn, B.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Curhan, G.C. Herpes zoster and long-term risk of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e027451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Wollan, P.; Nagel, M.A.; Gilden, D. The risk for stroke and myocardial infarction after herpes zoster in older adults in a US community population. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.M.; Choi, H.C.; Choi, D.P.; Park, S.H.; Kim, H.C. Severe herpes zoster infection is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases: A population-based case–control study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207624. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.C.; Yun, S.C.; Lee, H.B.; Park, J.K.; Lee, H.J.; Park, Y.S. Herpes zoster is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events: A population-based cohort study with propensity score matching. Korean Circ. J. 2017, 47, 685–693. [Google Scholar]

- Hosamirudsari, S.; Pakfetrat, M.; Foroughipour, M.; Parizadeh, S.A.; Mazaheri, M. Herpes zoster is a risk factor for stroke: A case–control study in an Iranian population. Iran. J. Neurol. 2018, 17, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Schink, T.; Behr, S.; Thöne, K.; Bricout, H.; Garbe, E.; Fink, K. Risk of stroke after herpes zoster: A self-controlled case-series study in Germany. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, C.; Thomas, S.L.; Smeeth, L.; Douglas, I.; Brauer, R.; Langan, S.M.; Whitaker, H.J. Acute cardiovascular events after herpes zoster: A self-controlled case series analysis in US Medicare population. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.U.; Yun, S.C.; Kim, M.C.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.O.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Woo, J.H.; Kim, S.H. Risk of stroke and transient ischaemic attack after herpes zoster: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström, K.; Weibull, C.E.; Söderberg-Löfdal, K.; Bergström, T.; Sparén, P.; Arnheim-Dahlström, L. Incidence of herpes zoster and associated events including stroke: A population-based cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilden, D.H.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Wellish, M.; Hedley-Whyte, E.T.; Rentier, B.; Mahalingam, R. Varicella-zoster virus, a cause of waxing and waning vasculitis: The New England Journal of Medicine. Neurology 1996, 47, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.A. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: Clinical features and pathogenesis. J. NeuroVirol. 2014, 20, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Reichelt, M.; Gilden, D.; Nagel, M.A.; Wellish, M.; Grose, C. Varicella-zoster virus infection of human brain vascular adventitial fibroblasts and perineurial cells downregulates PD-L1 and MHC class I. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakradze, E.; Kirchoff, K.F.; Antoniello, D.; Springer, M.V.; Mabie, P.C.; Esenwa, C.C.; Labovitz, D.L.; Liberman, A.L. Varicella zoster virus vasculitis and adult cerebrovascular disease. Neurohospitalist 2019, 9, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Wollan, P.C.; Nagel, M.A.; Gilden, D. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy and its role in stroke and cardiovascular disease. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106427. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Hou, X.; Bi, X. A case of ischemic stroke secondary to varicella-zoster virus meningoencephalitis. J. NeuroVirol. 2022, 28, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düzgöl, M.; Ören, H.; Demircioğlu, F.; Gülhan, B.; Kutluk, T. Varicella-Zoster Virus infections in pediatric malignancy patients: A seven-year analysis. Turk. J. Hematol. 2016, 33, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Zhang, X.; Brown, C.; Choi, H.; Qian, S.X. Herpes zoster and risk of stroke: A self-controlled case series study in US Medicare beneficiaries. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa168. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, K.; Yawn, B.P.; Wollan, P.; Harpaz, R.; Toyama, N. Antiviral treatment for herpes zoster and risk of stroke: A nationwide cohort study in Japan. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, M.; Berlit, S.; Berlit, P.; Ploner, C.J. Varicella zoster virus vasculitis: Prolonged antiviral treatment with valaciclovir and steroids may improve outcome. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2022, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Meng, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X. Effects of herpes zoster vaccination and antiviral treatment on the risk of stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1176920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Gilden, D.H. Vaccination and antiviral treatment in preventing stroke after herpes zoster: Current evidence and future directions. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1086. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T.; Fujimoto, T.; Takahashi, K.; Shindo, H.; Morita, H. Cerebral varicella zoster virus vasculopathy causing multiple infarctions despite antiviral and steroid therapy: An autopsy case report. Intern. Med. 2025, 64, 2774–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, D.; Toczyłowski, K.; Kowalska, M.; Krasnodębska, M.; Krupienko, I.; Nartowicz, K.; Sulik, M.; Sulik, A. Varicella-Zoster Disease of the Central Nervous System in Immunocompetent Children: Case Series and a Scoping Review. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwofie, S.K.; Annan, D.G.; Adinortey, C.A.; Boison, D.; Kwarko, G.B.; Abban, R.A.; Adinortey, M.B. Identification of novel potential inhibitors of varicella-zoster virus thymidine kinase from ethnopharmacologic relevant plants through an in-silico approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 12932–12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, C.S.; Frietze, S.; Coughlan, C.; Lewis, S.W.R.; Bustos Lopez, S.; Saviola, A.J.; Hansen, K.C.; Medina, E.M.; Hassell, J.E., Jr.; Kogut, S.; et al. Suppression of the host antiviral response by non-infectious varicella zoster virus extracellular vesicles. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0084824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, M.A.; Gilden, D. Developments in Varicella Zoster Virus Vasculopathy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, P.G. Issues in the Treatment of Neurological Conditions Caused by Reactivation of Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV). Neurotherapeutics 2016, 13, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, Y. Resveratrol may be an effective prophylactic agent for ischemic stroke. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2011, 110, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, P.-H.; Chuang, Y.-S.; Lin, Y.-T. Does Herpes Zoster Increase the Risk of Stroke and Myocardial Infarction? A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, W.; Li, X. Vesicle trafficking and viral infection: Mechanisms of host–virus interaction. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1682139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Sguigna, P.; Rupareliya, C.; Subramanian, S.; Salahuddin, H.; Husari, K.S.; Moore, W.; Johnson, M.; Magadan, A.; Grose, C.; et al. Detection of Varicella Zoster Virus Reactivation in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriou, D.; Moraitis, E.; Hong, Y.; Turmaine, M.; Venturini, C.; Ganesan, V.; Breuer, J.; Klein, N.; Brogan, P. Microparticle-mediated VZV propagation and endothelial activation: Mechanism of VZV vasculopathy. Neurology 2020, 94, e474–e480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.; Blackmon, A.; Neff, C.P.; Palmer, B.E.; Gilden, D.; Badani, H.; Nagel, M.A. Varicella-zoster virus downregulates programmed death ligand 1 and major histocompatibility complex class I in human brain vascular adventitial fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and lung fibroblasts. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10527–10534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Ibhiedu, J.O.; Egbunu, E.O.; Ndam, A.R.; Ogala, F.; Ologunde, T.; Peterson, J.C.; Boluwatife, A.I.; et al. Stroke and cognitive impairment: Understanding the connection and managing symptoms. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 6057–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).