Abstract

Genomic surveillance has emerged as a crucial tool in monitoring and understanding the dynamics of viral variants during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Midwest region of Brazil, Mato Grosso do Sul has faced a significant burden from the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, with a total of 613,000 confirmed cases as of June 2023. In collaboration with the Central Public Health Laboratory in the capital city of Campo Grande, we conducted a portable whole-genome sequencing and phylodynamic analysis to investigate the circulation of the Omicron variant in the region. The study aimed to uncover the genomic landscape and provide valuable insights into the prevalence and transmission patterns of this highly transmissible variant. Our findings revealed an increase in the number of cases within the region during 2022, followed by a gradual decline as a result of the successful impact of the vaccination program together with the capacity of this unpredictable and very transmissible variant to quickly affect the proportion of susceptible population. Genomic data indicated multiple introduction events, suggesting that human mobility played a differential role in the variant’s dispersion dynamics throughout the state. These findings emphasize the significance of implementing public health interventions to mitigate further spread and highlight the powerful role of genomic monitoring in promptly tracking and uncovering the circulation of viral strains. Together those results underscore the importance of proactive surveillance, rapid genomic sequencing, and data sharing to facilitate timely public health responses.

1. Introduction

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious coronavirus that emerged in late 2019, causing a global pandemic of acute respiratory illness known as ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ (COVID-19) and posing a significant threat to human health. The disease was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, with the World Health Organization declaring it a global public health emergency on 30 January 2020 [1,2]. Brazil confirmed its first case on 26 February 2020, followed by community transmission nationwide on 20 March 2020 [1,3]. Mato Grosso do Sul, situated in the Midwest region of Brazil, has experienced a substantial burden from the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, with a total of 613,000 confirmed cases as of June 2023. As a crucial corridor for wildlife movement between different biomes, the state plays a pivotal role in maintaining biodiversity. Thus, implementing genomic surveillance can aid in identifying genetic interactions and gene flow between species, supporting conservation efforts, and preserving genetic integrity also considering that the Pantanal, one of the world’s largest tropical wetland areas, flourishes in Mato Grosso do Sul. In the context of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, the state has responded quickly by implementing various measures, such as social distancing, mask-use promotion, and localized lockdowns. Increased testing capacity and improved contact tracing efforts have also been essential [4]. Different variants, including variants of concern (VOCs), variants of interest (VOIs), and variants under monitoring (VUMs), have been identified in the state throughout the epidemic progression, [5]. However, the genomic diversity and the evolution dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron wave in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul remain largely unknown. To address this gap, we conducted a collaborative study with the Central Public Health Laboratory in the capital city of Campo Grande. Our study involved portable whole-genome sequencing and phylodynamic analysis to investigate the spread and transmission patterns of the Omicron variant in the region. This research has provided insights into the expansion of this lineage in the state, revealing a complex transmission dynamic characterized by the co-circulation of different sublineages. In addition to shedding light on the Omicron variant, our study serves as a proof-of-concept for the value of portable sequencing technologies in local capacity building and public health efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Molecular Diagnostic Assays

Convenience clinical samples were collected between January and February 2022 from individuals suspected of SARS-CoV-2 infection and were included in our genomic surveillance framework for real-time monitoring of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants in the region [5]. Nasopharyngeal swabs were utilized to extract viral RNA, which was subsequently subjected to analysis using the Charité SARS-CoV2 (E/RP) assay provided by Bio-Manguinhos. This assay specifically targeted the E gene and was made available by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (BrMoH) and the Pan-American Health Organization. The samples were collected for both diagnostic purposes and whole genome sequencing analysis.

2.2. cDNA Synthesis and Whole-Genome Sequencing

Samples were chosen for sequencing based on a Ct value (≤30) and the availability of epidemiological metadata, including the date of sample collection, sex, age, and municipality of residence. The SARS-CoV-2 genomic libraries were prepared using nanopore sequencing. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using the SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The generated cDNA underwent multiplex PCR sequencing using the Q5 High-Fidelity Hot-Start DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and a set of specific primers designed by the ARTIC Network for sequencing the complete SARS-CoV-2 genome (Artic Network version 3) (Quick, J, 2020). PCR conditions have been previously reported [3]. All experiments were conducted within a biosafety level 2 cabinet. Amplicons were purified using 1× AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA, USA) and quantified with a Qubit 3.0 fluorimeter (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (ThermoFisher). DNA library preparation was carried out using the ligation sequencing kit LSK109 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) and the native barcoding kit (NBD104 and NBD114, Oxford Nanopore Technologies). The prepared sequencing libraries were loaded onto an R9.4 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). In each sequencing run, negative controls were included to prevent and detect possible contamination, with a mean coverage of less than 2%.

2.3. Generation of Consensus Sequences

The raw files from Oxford Nanopore sequencing were basecalled using Guppy v3.4.5, and barcode demultiplexing was conducted using qcat. Consensus sequences were then generated through de novo assembly using Genome Detective [6].

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

Lineage assignment was conducted using the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages tool (PANGOLIN) [7]. The newly generated sequences from this study were compared to a diverse pool of 2986 genome sequences collected worldwide up until 2 June 2023. Due to the extensive amount of available data and the uneven distribution of strains from different regions, countries, and continents, we utilized the Subsampler tool, available at https://github.com/andersonbrito/subsampler (accessed on 10 July 2023), which enabled us to perform random subsampling of sequences per country based on case counts over the study period. By doing so, we ensured that our samples were geographically, temporally, and epidemiologically representative. Furthermore, the subsampling within this scheme was conducted using a baseline function, which allowed us to determine the proportion of cases we aimed to sample. This process was carefully designed to maintain the overall characteristics and diversity of the data while minimizing potential biases. All sequences were aligned using the ViralMSA tool [8] and the maximum likelihood approach was employed for phylogenetic analysis using IQ-TREE 2 [9]. To obtain a dated tree, TreeTime [10] was employed, employing a constant mean rate of 8.0 × 10−4 nucleotide substitutions per site per year, after removing outlier sequences.

2.5. Epidamiological Data Assesment

Data from weekly notified cases of infection, deaths, and hospitalization by SARS-CoV-2 in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul were supplied by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, as made available by the COVIDA network at https://github.com/wcota/COVID19br (accessed on 10 July 2023).

3. Results

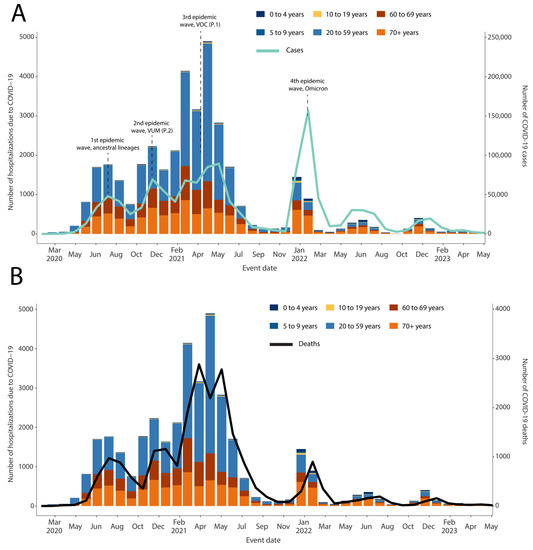

The SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul consisted of four distinct main waves (Figure 1), resulting in over 613,000 thousand cases and 11 thousand deaths as of June 2023. The initial wave spanned from May 2020 to September 2020 and exhibited the circulation of various ancestral lineages (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [3].

Figure 1.

Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. (A) Number of daily COVID-19 cases and the number of hospitalization rates in time; (B) number of daily COVID-19 deaths and the number of hospitalization rates in time.

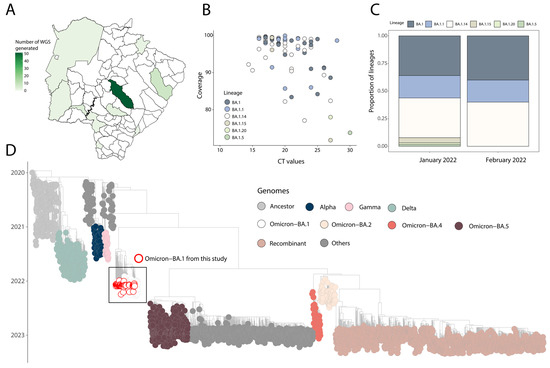

Figure 2.

Genomics and epidemiological reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages circulating in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. (A) Spatial distribution of SARS-CoV-2 genomes obtained in this study; (B) SARS-CoV-2 sequencing statistics: percentage of SARS-CoV-2 genomes sequenced plotted against RT-qPCR Ct value for each sample (n = 69). Each circle represents a sequence recovered from an infected individual in Mato Grosso do Sul. Colored circles correspond to lineage assignment; (C) progressive distribution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 sublineages in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul over time; (D) time-resolved maximum-likelihood tree of SARS-CoV-2, including a representative worldwide subsample of genomes (n = 2986) collected up to 2 June 2023. The genomes are color-coded according to lineages (VOC and ancestral lineages) as indicated in the legend on the top right. The genome generated in this study is highlighted in the tree with a white fill and a red circle.

The second wave, which occurred from October 2020 to December 2020, was driven by the emergence and rapid spread of the P.2 (Zeta) variant under monitoring (VUM). In contrast, the third wave (December 2020 to May 2021) was primarily caused by the introduction of the Gamma (P.1) variant of concern (VOC), resulting in a significant increase in the number of reported cases and deaths in the country [11]. However, as the Delta VOC was introduced in late April 2021, the number of cases and deaths started to decline (Figure 1) [12]. Following these waves, the fourth major wave occurred in late November 2021 with the emergence of the Omicron variant as the newest VOC. Our data suggest that the Omicron wave experienced a rapid peak followed by a swift decline, possibly indicating the successful impact of the vaccination program [13]. Additionally, the highly transmissible nature of the Omicron variant played a significant role in swiftly affecting a large portion of the susceptible population.

Furthermore, our analysis of the total number of cases, deaths, and COVID-19-related hospitalizations revealed that the age group between 20 and 59 years bore the highest disease burden from February to May 2021. This spike in cases coincided with the circulation of the Gamma variant, which overwhelmed healthcare facilities at both the national and regional levels, primarily impacting the susceptible population.

In order to retrospectively reconstruct the transmission dynamic of the Omicron variant in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, a total of 69 near-full genome sequences were obtained from SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR positive samples as part of this study. The sequencing spanned from January to February 2022, and samples were collected from 10 distinct cities across the state (Figure 2A).

These samples comprised 41 females and 28 males (Table 1), with a median age of 41.0 years (range: 11 to 91 years).

Table 1.

Epidemiological data the 69 SARS-CoV-2 samples sequenced as part of this study.

All tested samples contained sufficient viral genetic material (≥2 ng/µL) for library preparation. The average PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value for positive samples was 20.75 (range: 10 to 30). Sequences had a median genome coverage of 94% (range: 72 to 99.99), with samples that had lower Ct values generally exhibiting higher average genome coverage (Figure 2B). Detailed epidemiological information and sequencing statistics of the generated sequences can be found in Table 1. Based on the proposed dynamic nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 lineages, the sequences were assigned to six different Omicron BA.1 PANGO-lineages (Figure 2C and Table 1). Novel genome sequences have been submitted to GISAID following the WHO guidelines (Table 1) (version 4.2). Phylogenetic inference, combining our novel isolates with a representative dataset available on GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/) up to 2 June 2023, revealed that the newly obtained genomes belong to different SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 sublineages (Figure 2D), which were interspersed with those introduced from several countries (Figure 2D). This pattern indicates multiple introduction events highlighting how critical integrating genome sequence with human mobility data will be to promptly reconstruct and track the transmission dynamics of those emerging strains. (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Genomic surveillance is of pivotal importance in monitoring SARS-CoV-2 variants and informing public health responses. Variants of concern (VOCs) have had a significant impact on the severity of COVID-19, therapeutic approaches, and vaccination efforts [3,14,15,16,17]. These variants are characterized by increased transmissibility and the potential to affect disease severity. Specific mutations, such as N501Y and E484K, have been identified as contributing to enhanced transmissibility and immune evasion. Therefore, continuous monitoring and regular updates in therapeutic strategies are essential to effectively address these evolving variants.

To assess the impact of the Omicron variant in Mato Grosso do Sul, a state located in the Midwest region of Brazil, we conducted on-site training in genomic surveillance in collaboration with the state’s Public Health Laboratory. Through this collaboration, we were able to generate 69 newly SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequences. Our analysis revealed four waves of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the state, with each wave characterized by the circulation and replacement of different viral strains [11,17]. Consistent with previous findings, the Gamma variant was associated with a significant increase in reported cases and deaths in the state, particularly among individuals aged 20–59 (Figure 1).

Our data demonstrated that the emergence of the Omicron variant coincided with the fourth major wave, exhibiting a distinct pattern of a rapid peak followed by a swift decline (Figure 1). This trend can be attributed to several factors. The vaccination program played a crucial role in reducing illness severity and transmission, as a significant portion of the population had received vaccination doses by the time the Omicron variant emerged. The highly transmissible nature of the Omicron variant contributed to exponential growth in cases, but the number of susceptible individuals decreased due to vaccination or prior infection [18].

Genomic monitoring in our study additionally identified distinct Omicron sublineages (Table 1 and Figure 2), indicating complex transmission dynamics influenced by the co-circulation of multiple viral strains. Human mobility played a significant role in the dissemination of these sublineages, facilitated by Mato Grosso do Sul’s geographical location as a border region and active trade and travel routes [19]. Understanding the impact of human mobility on variant introduction and dissemination is crucial for effective public health interventions.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the significance of genomic monitoring in comprehending the transmission dynamics of emerging variants. Further advancement in the field of genomic surveillance necessitates investigation in several areas and should focus on long-term genomic monitoring to track the evolutionary trajectory and potential changes in viral genetic characteristics. Comparative genomic analyses across different regions and countries will also be crucial to identify geographic-specific patterns and inform targeted public health interventions. Exploring the role of host genetic factors and their interplay with viral evolution will further enhance our understanding of susceptibility, disease severity, and vaccine response. Lastly, expanding genomic surveillance to include animal hosts and environmental samples in a One Health approach can facilitate early detection and response to zoonotic transmission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G., L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; methodology: L.d.M.A.M., M.G., V.F., M.C.S.U.Z., G.G.d.C.L., G.R.d.R.R., L.D.C., V.C.E., K.F.B., D.G.M.T., J.X., H.F., M.L., C.d.O., E.V.S., D.F.R.F., D.H.T., R.F.d.C.S., A.R., L.H.D., L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; validation: M.G. and V.F.; formal analysis: L.d.M.A.M., M.G. and V.F.; investigation: L.d.M.A.M., M.G., V.F., M.C.S.U.Z., G.G.d.C.L., G.R.d.R.R., L.D.C., V.C.E., K.F.B., S.K., J.C., D.G.M.T., J.X., H.F., M.L., C.d.O., E.V.S., D.F.R.F., D.H.T., R.F.d.C.S., A.R., L.H.D., L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; resources: L.C.J.A.; data curation: M.G. and V.F.; writing—original draft preparation: L.d.M.A.M., M.G., L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; writing—review and editing, L.d.M.A.M., M.G., V.F., M.C.S.U.Z., G.G.d.C.L., G.R.d.R.R., L.D.C., V.C.E., K.F.B., S.K., D.G.M.T., J.C., J.X., H.F., M.L., C.d.O., E.V.S., D.F.R.F., D.H.T., R.F.d.C.S., A.R., L.H.D., L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; visualization: M.G. and V.F.; supervision: L.C.J.A. and C.C.M.G.; funding acquisition: L.C.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health USA grant U01 AI151698 for the United World Arbovirus Research Network (UWARN) and in part by the CRP- ICGEB RESEARCH GRANT 2020 Project CRP/BRA20-03, Contract CRP/20/03.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research received ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHOERC.0344.01) and the Federal University of Minas Gerais (CEP/CAAE: 32912820.6.1001.5149).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Newly generated SARS-CoV2-sequences have been deposited in GISAID under accession numbers EPI_ISL_17885390 and EPI_ISL_17885458. All inputs and codes used in this study were made available in main text and on the project GitHub repository: https://github.com/genomicsurveillance/omicron_mato_grosso_do_sul/tree/main (accessed on 10 July 2023).

Acknowledgments

M.G. is funded by PON “Ricerca e Innovazione” 2014–2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Kok, K.H.; To, K.K.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Yip, C.C.; Poon, R.W.; et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020, 395, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croda, J.H.R.; Garcia, L.P. Immediate Health Surveillance Response to COVID-19 Epidemic. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2020, 29, e2020002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanetti, M.; Slavov, S.N.; Fonseca, V.; Wilkinson, E.; Tegally, H.; PatanÉ, J.S.L.; Viala, V.L.; San, E.J.; Rodrigues, E.S.; Santos, E.V.; et al. Genomic epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Brazil. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaria de Estado de Saúde de Mato Grosso do Sul. Epidemiological Report from the State of Mato Grosso do Sul. SES MS. 2020. Available online: https://www.saude.ms.gov.br/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Tosta, S.; Moreno, K.; Schuab, G.; Fonseca, V.; Segovia, F.M.C.; Kashima, S.; Elias, M.C.; Sampaio, S.C.; Ciccozzi, M.; Alcantara, L.C.J.; et al. Global SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance: What we have learned (so far). Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 108, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilsker, M.; Moosa, Y.; Nooij, S.; Fonseca, V.; Ghysens, Y.; Dumon, K.; Pauwels, R.; Alcantara, L.C.; Vanden Eynden, E.; Vandamme, A.-M.; et al. Genome Detective: An automated system for virus identification from high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; O’Toole, Á.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Ruis, C.; du Plessis, L.; Pybus, O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534, Erratum in Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagulenko, P.; Puller, V.; Neher, R.A. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vex042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.D.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Sales, F.C.S.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T.; et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanetti, M.; Cella, E.; Benedetti, F.; Magalis, B.R.; Fonseca, V.; Fabris, S.; Campisi, G.; Ciccozzi, A.; Angeletti, S.; Borsetti, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 shifting transmission dynamics and hidden reservoirs potentially limit efficacy of public health interventions in Italy. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitiello, A.; Ferrara, F.; Troiano, V.; La Porta, R. COVID-19 vaccines and decreased transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; Sasi, S.; Pillai, S.G.; Nag, A.; Shukla, D.; Singhal, R.; Phalke, S.; Velu, G.S.K. SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Their Impact on Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Vaccines. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 815389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khateeb, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and potential intervention approaches. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resende, P.C.; Gräf, T.; Paixão, A.C.D.; Appolinario, L.; Lopes, R.S.; Mendonça, A.C.d.F.; da Rocha, A.S.B.; Motta, F.C.; Neto, L.G.L.; Khouri, R.; et al. A Potential SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Interest (VOI) Harboring Mutation E484K in the Spike Protein Was Identified within Lineage B.1.1.33 Circulating in Brazil. Viruses 2021, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveca, F.G.; Nascimento, V.; de Souza, V.C.; Corado, A.d.L.; Nascimento, F.; Silva, G.; Costa, Á.; Duarte, D.; Pessoa, K.; Mejía, M.; et al. COVID-19 in Amazonas, Brazil, was driven by the persistence of endemic lineages and P.1 emergence. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Rickeard, T.; Gallagher, E.; Gower, C.; Kall, M.; Groves, N.; O’Connell, A.-M.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva, G.D.C.; Dos Reis, D.S.; Filho, R.D.O. Estrutura urbana e mobilidade populacional: Implicações para o distanciamento social e disseminação da COVID-19. Rev. Bras. Estud. Popul. 2020, 37, e0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).