Abstract

Despite the great technological and medical advances in fighting viral diseases, new therapies for most of them are still lacking, and existing antivirals suffer from major limitations regarding drug resistance and a limited spectrum of activity. In fact, most approved antivirals are directly acting antiviral (DAA) drugs, which interfere with viral proteins and confer great selectivity towards their viral targets but suffer from resistance and limited spectrum. Nowadays, host-targeted antivirals (HTAs) are on the rise, in the drug discovery and development pipelines, in academia and in the pharmaceutical industry. These drugs target host proteins involved in the virus life cycle and are considered promising alternatives to DAAs due to their broader spectrum and lower potential for resistance. Herein, we discuss an important class of HTAs that modulate signal transduction pathways by targeting host kinases. Kinases are considered key enzymes that control virus-host interactions. We also provide a synopsis of the antiviral drug discovery and development pipeline detailing antiviral kinase targets, drug types, therapeutic classes for repurposed drugs, and top developing organizations. Furthermore, we detail the drug design and repurposing considerations, as well as the limitations and challenges, for kinase-targeted antivirals, including the choice of the binding sites, physicochemical properties, and drug combinations.

1. Introduction

Antiviral drugs could be targeted towards either viral proteins (e.g., polymerases, integrase, proteases, accessory proteins, and viral structural proteins), or host proteins that support the viral life cycle [1,2,3]. In 1963, idoxuridine was the first directly acting antiviral (DAA) drug to be approved, initiating a new era in fighting viral infections using drugs that directly target viral proteins [4]. Such drugs gained great attention due to the discovery and licensing of 80 DAA drugs [1]. These drugs were considered safe for humans since they target viral proteins which have no human homologs, except for viral polymerase, which does share some structural similarities with human polymerases, thus being a major reason for nucleoside-based antiviral toxicity [5].

Despite the initial success and low toxicity outcomes on humans, the DAA drug approach faced many hurdles, including the narrow spectrum of activity and the development of antiviral resistance. In fact, every virus has its own set of highly specialized proteins [5]; some proteins share homology among some viruses, but the majority are unique. As a result, broad-spectrum DAA drug discovery efforts often fail and there are only a few other broad-spectrum antiviral drugs in the market that are approved [5]. Therefore, older antivirals often fail to fight novel emerging viruses which threaten the human population by their ability to cause epidemics and pandemics [6]. Additionally, and despite initial success, DAA drugs usually lose their efficacy due to constant viral mutations.

Resistant viral variants emerge over time with different speeds for RNA versus DNA viruses [7]. RNA viruses have mutational rates reaching 10−4 (i.e., one mutation per 10,000 base replications), in comparison to mutational rates of 10−8 for DNA viruses [8]. Thus, extended exposure to viral infection and continuing viral replication are key factors in the development of antiviral resistance [7]. This led to new legislation for the clinical development of antiviral agents which require testing for viral resistance, mutations, and cross-resistance that persists with treatment [9]. Another hurdle facing the DAA drug approach is the limited number of potential viral proteins that could be targeted with drugs, especially for viruses with small genomes, such as human papillomavirus [7].

Targeting human proteins for antiviral drug discovery may result in the development and approval of broader spectrum antiviral drugs that are inherently less susceptible to viral resistance. Thus, host-targeted antivirals (HTAs) are considered promising therapeutic options for combating emerging novel pathogens; even before their genes and proteins are fully characterized [7,10]. Such drugs could potentially lead to universal antiviral agents. Herein, we provide a comprehensive overview of disease-causing viruses, their classification, their life cycle, and their reliance on host kinases to replicate and produce offspring. We also detail the drug discovery strategies that target host kinases to halt the viral life cycle that could potentially lead to universal antiviral agents.

2. Disease-Causing Viruses

Disease-causing viruses cause viral infections, which include any illness that is caused by a virus. A virion is the infectious form of the virus that is released from host cells after viral replication [11]. It protects the virus genome and facilitates its entry into specific host cells, which have the required receptors or proteins that facilitate its entry [11,12]. The virion contains the genome, and it is surrounded by a capsid, which is made up of proteins, to protect the genome [13]. Some viruses, such as those from the Pleolipoviridae family, do not have capsids [14]. Other viruses have an envelope, which encloses the capsid and is made up of a lipid bilayer embedded with virus-specific glycoproteins, derived from the host’s cell plasma membrane or an intracellular vesicle [13]. Depending on the virus type, other components of virions include mRNAs, proteins and enzymes, and polyamines [13].

2.1. Classification of Viruses

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) system classifies viruses into different taxonomic levels, starting with realms and ending with species [15,16]. Currently, ICTV’s database of taxonomy shows that there are 10,434 species of viruses [17].

There are two different classification systems being adopted for viruses. The classification systems do not correspond to each other, and each is used separately. The first classifies viruses based on their genome; DNA or RNA [13]. They can be viewed in the most recent ICTV Report on Virus Classification and Taxon Nomenclature [18]. The second, which is the Baltimore Classes (BC) system [19,20,21,22], classifies viruses according to the path and process in which the genome is transcribed into an mRNA that is needed for a translation into proteins [13]. The production of mRNA from each type is discussed in the Virus Life Cycle section below. The classification systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Two classification systems for viruses based on the virus genome and Baltimore classes.

2.2. Virus Life Cycle

The life cycle of viruses comprises several basic steps starting with viral entry into the host cell and followed by gene expression, gene replication, and finally ending in assembly and viral egress to release new infectious viral particles [13]. However, there could be many differences in how each virus (or class of viruses) achieves these steps. To design effective treatments or preventive therapeutics for viral diseases, especially those targeting host proteins, we need to understand the similarities and differences in the life cycles of viruses [23].

2.2.1. Virus Entry and Uncoating

The entry of viruses into the host cell comprises two stages: attachment and penetration. Entry is later followed by uncoating. These stages would differ between enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. As for enveloped viruses, their membrane would initially fuse with the host cell membrane via the binding of specific viral envelope glycoproteins (also called fusion proteins) to host cell receptors [24]. Consequently, a pore opening (fusion pore) [24,25,26], which might be either enlarged or not [25,27,28,29], allows the passage of the virus core into the host cell cytoplasm [26]. A different mechanism involves the uptake of the virus into an endocytic vesicle followed by the fusion of the viral envelope with the vesicle membrane and releasing the capsid [13]. The fusion mechanisms are either pH-dependent or pH-independent [26].

Non-enveloped viruses attach themselves to host cells via either a single protein or multiple protein structures [30,31]. Then, the virus is internalized into the cell by an endocytic vesicle formed via receptor-mediated uptake, followed by the release of the virus and genome into the host cell cytoplasm [13]. Other viruses can inject their genome directly into the host cell cytoplasm across the host cell membrane [13].

Viral attachment to host cells is followed by uncoating, which is the process of releasing the viral genome either into the cytoplasm or directly into the host cell nucleus via the nuclear pores after breaking down viral capsids [13,32]. This step is essential for starting the virus life cycle and permitting the virus to replicate its genetic material.

2.2.2. Gene Expression and Replication

Viral gene expression involves mRNA synthesis (transcription) followed by protein synthesis (translation) inside host cells. Transcription is accomplished via the host and/or viral enzymes, while translation is accomplished via host ribosomes. All viral genomes, irrespective of their type, would be transcribed into mRNA. Gene expression differences do exist between viruses based on the viral genome type. Gene replication, in which a new viral genome is produced to be incorporated into new virions, occurs inside host cells as well. Some viruses undergo replication processes of the genetic material before their genome is eventually transcribed, such as BCII, BCVI, and BCVII viruses [13,22]. On the other hand, BCI, BCIII, and BCV viruses would be transcribed directly, while BCIV viruses are directly translated [13,22].

BCI double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and BCII single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses, except for poxviruses, have their genome-containing capsids or nucleoprotein complexes moved to the nuclear pores, which permit viral genome entry into the nucleus where gene expression and replication occur [13]. The gene expression of BCIV ((+) ssRNA) viruses starts directly after viral uncoating in the cytoplasm, where viral genomes associate with host ribosomes to start the translation process of viral proteins [13]. However, the genomes of BCIII (dsRNA) and BCV ((−) ssRNA) viruses are associated with the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [13]. Reverse transcribing viruses, BCVI ((+) ssRNA) viruses and BCVII (dsDNA) viruses, associate with the viral reverse transcriptase enzyme (RTz) [13]. A summary of the mechanisms involved in the gene expression and replication of several classes of viruses is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

A stepwise summary of gene expression and gene replication mechanisms among different classes of viruses [13,22,33,34,35,36].

2.2.3. Assembly and Egress

The assembly of virions usually takes place at the site of genome replication [13]. Most RNA virions are assembled in the cytoplasm, while most DNA viruses at least start their assembly inside the nucleus. The egress (release) of new virions depends on their type in terms of non-enveloped or enveloped virions [13]. Non-enveloped virions are released after the lysis of the host cell, whereas enveloped virions are released via budding from the host cell and acquiring an envelope from a particular cellular membrane. The envelope could be acquired from the plasma membrane in the final step or could be from the nuclear membrane, Golgi, or other organelle membranes. The new virion is transported via vesicle to the plasma membrane, in which the vesicle fuses with the plasma membrane and release the virion.

6. Kinases as Validated Biomarkers for Viral Infections

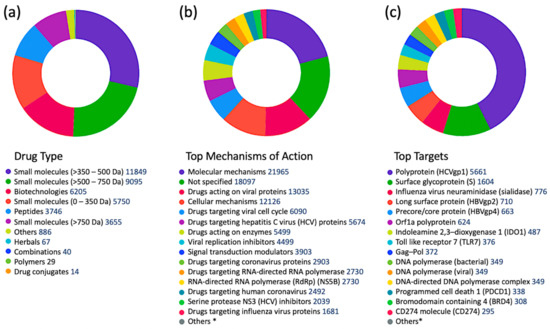

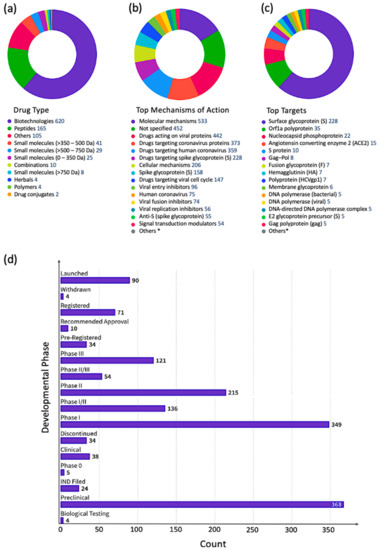

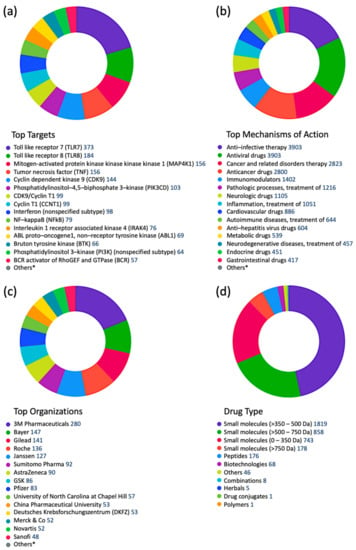

To get a better idea about which kinases have any potential for antiviral drug discovery, we mined all drugs and biologics in the CDDI database using the following search criteria: “condition = viral infection” and “mechanism = kinase”. These search criteria allow the retrieval of all drugs and biologics that have been linked to antiviral activity and can also modulate a kinase. Our search resulted in 1251 drugs and biologics, of which 1204 drugs are still in the biological testing phase and have not progressed in the drug development pipeline yet. In fact, 1224 drugs and biologics were coming from patents and could progress in the drug development pipeline soon. The top 10 kinase targets that have drugs “under active development” status for viral infections is protein kinase C (PKC), AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL), Casein kinase II (CK2), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAP2K; MAPKK; MEK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), MAPK p38, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 1 (CDK1), TEK receptor tyrosine kinase, and protein kinase B (PKB; Akt).

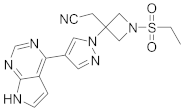

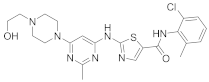

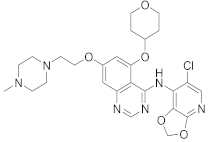

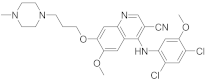

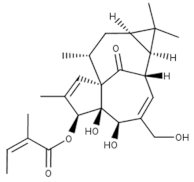

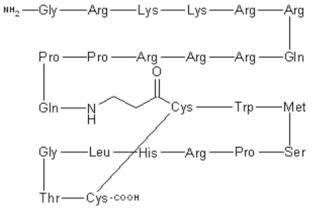

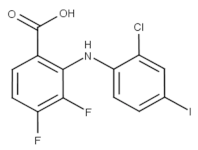

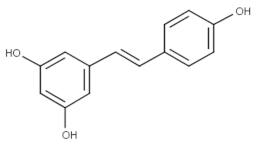

A more targeted search of the CDDI database was performed using the developmental status condition as follows: “development status condition = infection, viral” and “mechanism of action = drugs targeting kinases”. Imposing these filtering criteria ensure that the retrieved drugs and biologics have antiviral effects and are being developed precisely to combat viral infections by targeting kinases. This search resulted in seven drugs and biologics (Table 3). The drug targets of these drugs include casein kinase 2 (CK2), MAP2K, MAPK, MAPK p38, and CDK1. Five of the drugs have the “under active development (UAD)” label, indicating that products are actively moving through the drug research and development (R&D) pipeline from preclinical stages through registration. The launched drug 3-Angeloylingenol is not being investigated for new conditions, and therefore it is not considered UAD. In 2020, this drug was withdrawn from the market in Canada, the European Union, and the United Kingdom.

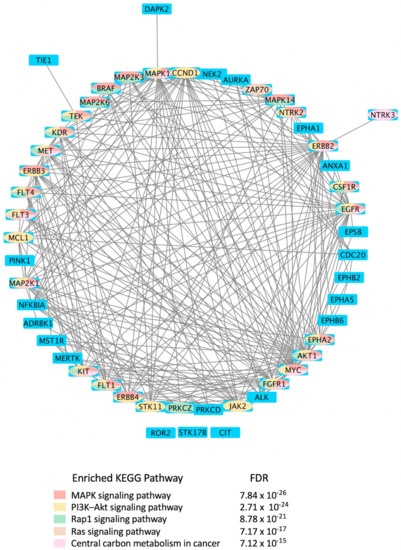

Mining CDDI for diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers aimed at viral infections resulted in 2994 biomarker records as hits. Among these, 1021 genomic and proteomic biomarkers have reached high validity levels (i.e., were either approved, recommended, or in clinical studies) according to the CDDI database [37]. Kinases make up 4.9% of these 1021 biomarkers, which highlights key roles in the pathogenesis of viral diseases. To get a better idea about the kinase biomarkers for viral infections, we generated a direct protein-protein interactions network using 51 kinases (resulting from the above data-mining effort in CDDI) as nodes (Figure 4). Network edges represented relationships between nodes based on validated experimental protein-protein interaction data extracted from the STRING [54] database. Network generation and visualization were performed in Cytoscape version 3.9.1 [55]. Network generation was followed by a functional enrichment analysis which highlighted the following pathways as top enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways: (1) MAPK signaling pathway; (2) phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K)-Akt signaling pathway; (3) Ras-associated protein 1 (Rap1) signaling pathway; (4) RAS signaling pathway; and central carbon metabolism in cancer. The complete enrichment results are provided in Supporting Information (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 4.

Protein-protein interactions network of kinases explored as diagnostic biomarkers for viral infections. Network nodes are human kinases that are viral disease biomarkers, according to the Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence databases [37]. The network was generated using Cytoscape version 3.9.1. Network nodes were colored based on the top five enriched KEGG pathways [73] shown in the color key beneath the network. Blue nodes indicate that the gene/gene product is not part of the top five enriched KEGG pathways shown underneath the network. The pathway prediction false discovery rate (FDR) is reported for each pathway. CDDI [37] was on https://www.cortellis.com/drugdiscovery/, accessed on 26 December 2022, ©2022 Clarivate. All rights reserved.

Notably, the top enriched pathways are directly linked to the virus life cycle and the biological processes that allow the virus to replicate and produce infectious progeny. For example, the MAPK signaling pathway can be activated by a diverse group of viruses [56], and it is involved in the replication of their genetic material. The information in the MAPK pathway is transmitted from one protein to another by phosphorylating serine and threonine residues in a diverse group of proteins leading to a multitude of cellular responses. Furthermore, ERK/MAPK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling responses play a critical role in the pathogenesis of many viral diseases. In fact, viruses such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) inhibit these pathways [56], among others.

Rap1 signaling regulates T-cell and antigen-presenting cell (APC) interactions and modulates T-cell responses to pathogens, such as viruses [57]. In fact, the activation state of Rap1 determines T-cell responses to antigens. Rap1 is also a target for the TLRs, which are key regulators of the immune response to viral infections [58]. Ras signaling was found important for the life cycle of some viruses, including the reovirus. Evidence showed that Ras-transformation affects viral uncoating and disassembly, PKR-induced translational inhibition, generation of viral progeny, the release of progeny, and viral spread [59].

It is also known that viruses hijack host metabolic resources and induce a plethora of metabolic alterations in host-cell including host central carbon metabolism. In fact, viral replication relies on extracellular carbon sources, such as glucose and glutamine [60]. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR and HIF-1 signaling pathways regulate glycolysis. Thus, targeting them with inhibitors, such as MK2206 (an Akt inhibitor) or 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG, glycolysis inhibitor), can lower the viral burden in the cells in vitro [61,62,63,64].

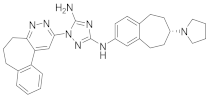

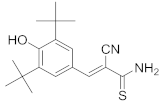

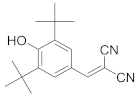

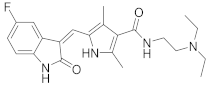

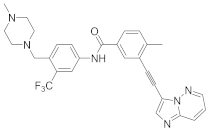

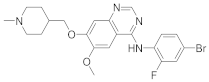

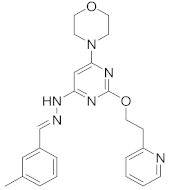

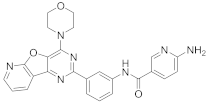

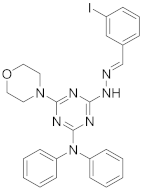

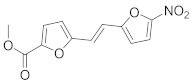

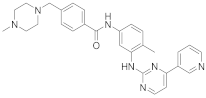

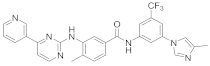

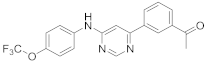

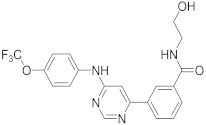

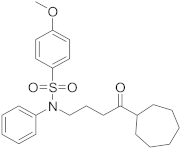

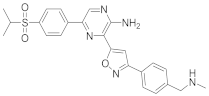

Table 3.

Antiviral drugs targeting human kinases in advanced stages of clinical development.

Table 3.

Antiviral drugs targeting human kinases in advanced stages of clinical development.

| Compound (Route of Administration) | Highest Phase (Condition) | * UAD | Target | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

3-Angeloylingenol (Topical) | Launched (Actinic Keratosis) | No | PKC | Local skin reactions at the application site, headache, periorbital edema, nasopharyngitis [1,65]. In 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended the suspension of the product in the EU and EEA as a precautionary measure. Later this year, the marketing authorization was withdrawn by the EMA as the product may increase the risk of skin cancer and the risks outweigh its benefits [37]. |

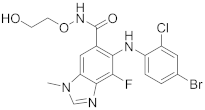

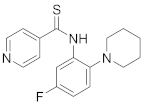

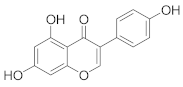

CIGB-300 P15-Tat (Topical) | Phase II (Genital warts) | Yes | CK2 | Local adverse events at the injection site including pain, bleeding, hematoma and erythema. Systemic adverse events include: rash, facial edema, itching, hot flashes, and localized cramps [66,67]. |

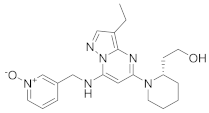

Zapnometinib (Oral) | Phase II/Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) | Yes | MEK | Adverse event profile is still unknown. Studies are ongoing [68]. Other MEK inhibitors caused cardiac and ophthalmologic side effects, rash, diarrhea, peripheral edema, fatigue, and dermatitis acneiform [68]. |

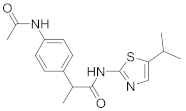

Trans-resveratrol (Topical) | Phase II (Herpes labialis) | Yes | MAPK | Headache, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal problems, urinary tract infections, falls and dizziness [69]. |

Terameprocol | Phase I (Prevention of HIV transmission) | Yes | CDK1 | Ileus, constitutional symptoms, interstitial nephritis, dyspnea and hypoxia, constipation, anorexia [70,71]. |

| POLB-001 | Phase I (Influenza) | Yes | MAPK p38 | Available clinical data indicated that the drug was tolerated at all tested drug doses with no serious adverse events or trial volunteer withdrawals [10]. It did not elicit liver or cardiac toxicities which could result from the polypharmacological effects of some p38 MAPK inhibitors due to modulating other kinases [72]. |

* UAD: under active development indicates, indicating that products are actively moving through the drug research and development (R&D) pipeline from preclinical stages through registration.

12. Conclusions

HTAs have vast potential to treat or prevent viral infections in addition to combating emerging novel viruses. They are conceivable to develop universal antivirals with an increased antiviral spectrum and reduced resistance. Certainly, viruses exploit host proteins to enter host cells, replicate their genomes, synthesize their own viral proteins, and produce a progeny of infectious viral particles. This review provided a summary of host proteins involved in the life cycle of viruses and provided an important update on the antiviral drug development pipeline with a special focus on kinase-targeting antivirals detailing their role in signal transduction pathways and providing drug discovery intelligence on drugs at different developmental stages. We also discussed repurposing approved kinase inhibitors, which have been clinically used for the treatment of cancers and inflammation, to combat viral diseases. However, more progress is needed to ensure that R&D efforts continue to identify novel kinase ligands or repurpose already existing kinase-targeting drugs to treat or prevent existing and emerging viral diseases. Indeed, the potential for developing novel antiviral kinase inhibitors is massive and will continue to be a major growth area for modulating infectious and auto-immune diseases in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v15020568/s1, Table S1: Enrichment results using 51 higher validity CDDI kinase biomarkers for viral diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H.; software, R.H.; formal analysis, R.H.; investigation, R.H., D.A.S., O.H.A. and S.B.; resources, R.H., D.A.S., O.H.A. and S.B.; biomarker data curation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H., D.A.S., O.H.A., R.K. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, R.H., D.A.S., O.H.A. and S.B.; visualization, R.H.; supervision, R.H.; project administration, R.H.; funding acquisition, R.H. and D.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

R.H. and D.A.S. acknowledge support from the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan (Grant number 2020-2019/17/03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results can be requested by contacting the corresponding author directly.

Acknowledgments

R.H. and D.A.S. acknowledge funding from the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan (Grant number 2020-2019/17/03).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| (+) | positive-sense |

| (−) | negative-sense |

| APC | Antigen-presenting cell |

| BC | Baltimore Class |

| CDDI | Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence |

| CDKis | CDK inhibitors |

| CDKs | Cyclin-dependent kinases |

| GAK | Cyclin G associated kinase (GAK) |

| DAA | Direct acting antiviral |

| ds | double-stranded |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| HAND | HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders |

| HTA | Host targeted antiviral |

| ICTV | International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MLKL | Mixed lineage kinase-like protein |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PKR | Protein kinase RNA-activated |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptors |

| R&D | Research and development |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| RIG-1 | Retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 |

| RIPK | Receptor interacting protein kinase |

| RLR | Retinoic acid-inducible gene 1(RIG-I)-like receptor |

| RT | reverse transcribing |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| RTz | Reverse transcriptase enzyme |

| ss | single-stranded |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| UAD | Under active development |

References

- Li, G.; De Clercq, E. Overview of Antiviral Drug Discovery and Development: ViralVersusHost Targets. In Antiviral Discovery for Highly Pathogenic Emerging Viruses; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah, D.A.; Hajjo, R.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Zhong, H.A. An Updated Review on SARS-CoV-2 Main Proteinase (M(Pro)): Protein Structure and Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.S.; Jarrar, Y.B. Targeting the intestinal TMPRSS2 protease to prevent SARS-CoV-2 entry into enterocytes-prospects and challenges. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4667–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasfeld, L.; Chou, S. Antiviral drug resistance: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 24, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, Z. Medicinal chemistry strategies toward host targeting antiviral agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1519–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhmais, B.; Hammad, A.M.; Al-Qerem, W.; Abusara, O.H.; Ling, J. Conducting COVID-19-Related Research in Jordan: Are We Ready? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schang, L.M.; St Vincent, M.R.; Lacasse, J.J. Five years of progress on cyclin-dependent kinases and other cellular proteins as potential targets for antiviral drugs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2006, 17, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, D.D.; Nathanson, N. Antiviral Therapy. In Viral Pathogenesis; Elsevier: Amesterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, D.D. Antiviral drug resistance. Antiviral Res. 2006, 71, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, D.A.; Hajjo, R.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Zhong, H.A. An Updated Review on Betacoronavirus Viral Entry Inhibitors: Learning from Past Discoveries to Advance COVID-19 Drug Discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.V.; Schmid, M.F. Principles of virus structural organization. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 726, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirfan, F.; Jarrar, Y.; Al-Qirim, T.; Goh, K.W.; Jarrar, Q.; Ardianto, C.; Awad, M.; Al-Ameer, H.J.; Al-Awaida, W.; Moshawih, S.; et al. Analgesics Induce Alterations in the Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Entry and Arachidonic-Acid-Metabolizing Genes in the Mouse Lungs. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, P.E.; Mitra, S.; Holland, T.C. Basics of virology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 123, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dyall-Smith, M.; Oksanen, H.M. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Pleolipoviridae 2022. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.M.; Lefkowitz, E.; Adams, M.J.; Carstens, E.B. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- ICTV. About Virus Taxonomic Classification. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy/about (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- ICTV. Current ICTV Taxonomy Release. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- ICTV. ICTV Report Chapters by Genome. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/genome (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Baltimore, D. Expression of animal virus genomes. Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. Viral genetic systems. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1971, 33, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. The strategy of RNA viruses. Harvey Lect. 1974, 70, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Koonin, E.V.; Krupovic, M.; Agol, V.I. The Baltimore Classification of Viruses 50 Years Later: How Does It Stand in the Light of Virus Evolution? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e0005321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardaweel, S.K.; Hajjo, R.; Sabbah, D.A. Sitagliptin: A potential drug for the treatment of COVID-19? Acta Pharm. 2021, 71, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plemper, R.K. Cell entry of enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikyan, G.B.; Barnard, R.J.; Abrahamyan, L.G.; Mothes, W.; Young, J.A. Imaging individual retroviral fusion events: From hemifusion to pore formation and growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8728–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosset, F.L.; Lavillette, D. Cell entry of enveloped viruses. Adv. Genet. 2011, 73, 121–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markosyan, R.M.; Cohen, F.S.; Melikyan, G.B. The lipid-anchored ectodomain of influenza virus hemagglutinin (GPI-HA) is capable of inducing nonenlarging fusion pores. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomordik, L.V.; Frolov, V.A.; Leikina, E.; Bronk, P.; Zimmerberg, J. The pathway of membrane fusion catalyzed by influenza hemagglutinin: Restriction of lipids, hemifusion, and lipidic fusion pore formation. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 140, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Diaz, E.; Peeples, M.E.; Markosyan, R.M.; Melikyan, G.B.; Cohen, F.S. Completion of trimeric hairpin formation of influenza virus hemagglutinin promotes fusion pore opening and enlargement. Virology 2003, 316, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.L.; Nemerow, G.R. Viral weapons of membrane destruction: Variable modes of membrane penetration by non-enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, M.; Greber, U.F. Uncoating of non-enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcher, S.; Mercer, J. DNA virus uncoating. Virology 2015, 479–480, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galibert, F.; Chen, T.N.; Mandart, E. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned woodchuck hepatitis virus genome: Comparison with the hepatitis B virus sequence. J. Virol. 1982, 41, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A.; Zoulim, F. Hepatitis B virus genetic variability and evolution. Virus Res. 2007, 127, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampersad, S.; Tennant, P. Replication and Expression Strategies of Viruses. Viruses 2018, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Dolja, V.V. Virus world as an evolutionary network of viruses and capsidless selfish elements. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014, 78, 278–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Narayanan, S.; Yang, D.-H. Chapter 9—CDK Inhibitors as Sensitizing Agents for Cancer Chemotherapy. In Protein Kinase Inhibitors as Sensitizing Agents for Chemotherapy; Chen, Z.-S., Yang, D.-H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjo, R.; Sabbah, D.A.; Bardaweel, S.K. Chemocentric Informatics Analysis: Dexamethasone Versus Combination Therapy for COVID-19. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29765–29779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjo, R.; Sabbah, D.A.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Tropsha, A. Shedding the Light on Post-Vaccine Myocarditis and Pericarditis in COVID-19 and Non-COVID-19 Vaccine Recipients. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.A.; Murray, B.W. Protein kinase biochemistry and drug discovery. Bioorg. Chem. 2011, 39, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cárceles, J.; Caballero, E.; Gil, C.; Martínez, A. Kinase Inhibitors as Underexplored Antiviral Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. Protein kinases--the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.B.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, J.D.; Corona, C.R.; Wilkinson, J.; Zimprich, C.A.; Hartnett, J.R.; Ingold, M.R.; Zimmerman, K.; Machleidt, T.; Kirkland, T.A.; Huwiler, K.G. Quantitative, wide-spectrum kinase profiling in live cells for assessing the effect of cellular ATP on target engagement. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 206–214.e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiry, P.; Torkamani, A.; Schork, N.J.; Hegele, R.A. Kinase mutations in human disease: Interpreting genotype-phenotype relationships. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, H.; He, W.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Z.; Ashraf, U.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fu, Z.F.; et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis identifies the critical role of JNK1 in neuroinflammation induced by Japanese encephalitis virus. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yángüez, E.; Hunziker, A.; Dobay, M.P.; Yildiz, S.; Schading, S.; Elshina, E.; Karakus, U.; Gehrig, P.; Grossmann, J.; Dijkman, R.; et al. Phosphoproteomic-based kinase profiling early in influenza virus infection identifies GRK2 as antiviral drug target. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schang, L.M. The cell cycle, cyclin-dependent kinases, and viral infections: New horizons and unexpected connections. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 2003, 5, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bagga, S.; Bouchard, M.J. Cell cycle regulation during viral infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1170, 165–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Chamorro, L.; Felip, E.; Ezeonwumelu, I.J.; Margelí, M.; Ballana, E. Cyclin-dependent Kinases as Emerging Targets for Developing Novel Antiviral Therapeutics. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.R. Signal integration via PKR. Sci. STKE 2001, 2001, re2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindel, A.; Sadler, A. The role of protein kinase R in the interferon response. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Romano, P.R.; Nagamura-Inoue, T.; Tian, B.; Dever, T.E.; Mathews, M.B.; Ozato, K.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Binding of double-stranded RNA to protein kinase PKR is required for dimerization and promotes critical autophosphorylation events in the activation loop. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 24946–24958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, L.; Labeau, A.; Dejarnac, O.; Cipriani, S.; Sinigaglia, L.; Bonnet-Madin, L.; Le Charpentier, T.; Hafirassou, M.L.; Zamborlini, A.; Cao-Lormeau, V.M.; et al. Axl Mediates ZIKA Virus Entry in Human Glial Cells and Modulates Innate Immune Responses. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Xie, W.; Liu, Y.; Sui, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Tan, Y.; Tong, X.; Fu, Z.F.; Yin, P.; et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors block proliferation of TGEV mainly through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Antivir. Res. 2020, 173, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Khandelwal, N.; Thachamvally, R.; Tripathi, B.N.; Barua, S.; Kashyap, S.K.; Maherchandani, S.; Kumar, N. Role of MAPK/MNK1 signaling in virus replication. Virus Res. 2018, 253, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, K.; Hattori, M.; Minato, N.; Kinashi, T. Rap1 functions as a key regulator of T-cell and antigen-presenting cell interactions and modulates T-cell responses. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 22, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaśkiewicz, A.; Pająk, B.; Orzechowski, A. The Many Faces of Rap1 GTPase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Mita, M.M. Activated ras signaling pathways and reovirus oncolysis: An update on the mechanism of preferential reovirus replication in cancer cells. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinehr, J.; Wilden, J.J.; Boergeling, Y.; Ludwig, S.; Hrincius, E.R. Metabolic Modifications by Common Respiratory Viruses and Their Potential as New Antiviral Targets. Viruses 2021, 13, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelberg, S.; Gupta, S.; Svensson Akusjärvi, S.; Ambikan, A.T.; Mikaeloff, F.; Saccon, E.; Végvári, Á.; Benfeitas, R.; Sperk, M.; Ståhlberg, M.; et al. Dysregulation in Akt/mTOR/HIF-1 signaling identified by proteo-transcriptomics of SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1748–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, D.A.; Hajjo, R.; Sweidan, K. Review on Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Structure, Signaling Pathways, Interactions, and Recent Updates of EGFR Inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, D.A.; Hajjo, R.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Zhong, H.A. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors: A recent update on inhibitor design and clinical trials (2016–2020). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Zibert, J. Ingenol mebutate gel, 0.015% repeat use for Multiple Actinic Keratoses on face and scalp: A review of the phase 3 clinical study rationale and design. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2013, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Solares, A.M.; Santana, A.; Baladrón, I.; Valenzuela, C.; González, C.A.; Díaz, A.; Castillo, D.; Ramos, T.; Gómez, R.; Alonso, D.F. Safety and preliminary efficacy data of a novel casein kinase 2 (CK2) peptide inhibitor administered intralesionally at four dose levels in patients with cervical malignancies. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-García, J.; López-Díaz, A.; Solares-Asteasuainzarra, M.; Baladrón-Castrillo, I.; Batista-Albuerne, N.; García-García, I.; González-Méndez, L.; Perera-Negrín, Y.; Valenzuela-Silva, C.; Pedro, A. Pharmacological and safety evaluation of CIGB-300, a casein kinase 2 inhibitor peptide, administered intralesionally to patients with cervical cancer stage IB2/II. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2013, 1, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chu, J.C.-H.-C. Management of Toxicities of Targeted Therapies. In IASLC Thoracic Oncology, 2nd ed.; Pass, H.I., Ball, D., Scagliotti, G.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 490–500.e493. [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT04480957. Ascending Dose Study of Investigational SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine ARCT-021 in Healthy Adult Subjects. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04480957 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Khanna, N.; Dalby, R.; Tan, M.; Arnold, S.; Stern, J.; Frazer, N. Phase I/II clinical safety studies of terameprocol vaginal ointment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 107, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tenchov, R.; Smoot, J.; Liu, C.; Watkins, S.; Zhou, Q. A comprehensive review of the global efforts on COVID-19 vaccine development. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 512–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambach, D.M. Potential adverse effects associated with inhibition of p38α/β MAP kinases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favalli, E.G.; Biggioggero, M.; Maioli, G.; Caporali, R. Baricitinib for COVID-19: A suitable treatment? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1012–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavletich, N.P. Mechanisms of cyclin-dependent kinase regulation: Structures of Cdks, their cyclin activators, and Cip and INK4 inhibitors. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 287, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, P.D.; Tong, L.; Pavletich, N.P. Structural basis of inhibition of CDK-cyclin complexes by INK4 inhibitors. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 3115–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sanyal, S.; Bruzzone, R. Breaking Bad: How Viruses Subvert the Cell Cycle. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. To cycle or not to cycle: A critical decision in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, U.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Turner, N.C.; Knudsen, E.S. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyressatre, M.; Prével, C.; Pellerano, M.; Morris, M.C. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: From small molecules to Peptide inhibitors. Cancers 2015, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendel, I.; Agbottah, E.T.; Kehn-Hall, K.; Kashanchi, F. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 by cdk inhibitors. AIDS Res. Ther. 2010, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Lee, E.M.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, W.-K.; Qian, X.; Tcw, J.; Kouznetsova, J.; Ogden, S.C.; Hammack, C.; et al. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of Zika virus infection and induced neural cell death via a drug repurposing screen. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwitasari, O.; Yan, X.; O’Donnell, J.; Johnson, S.; Tripp, R.A. Repurposing Kinase Inhibitors as Antiviral Agents to Control Influenza A Virus Replication. Assay. Drug Dev. Technol. 2015, 13, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okuyama-Dobashi, K.; Murakami, S.; Chen, W.; Okamoto, T.; Ueda, K.; Hosoya, T.; Matsuura, Y.; Ryo, A.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Inhibitory effect of CDK9 inhibitor FIT-039 on hepatitis B virus propagation. Antiviral Res. 2016, 133, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Ko, M.; Lee, J.; Choi, I.; Byun, S.Y.; Park, S.; Shum, D.; Kim, S. Identification of Antiviral Drug Candidates against SARS-CoV-2 from FDA-Approved Drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00819-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Zhou, H.X. Profiling SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (M(PRO)) Binding to Repurposed Drugs Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Classical and Neural Network-Trained Force Fields. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, S.M.; Eby, H.; Henkel, N.D.; Creeden, J.; Imami, A.; Asah, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Alnafisah, R.; Taylor, R.T.; et al. Identification of new drug treatments to combat COVID19: A signature-based approach using iLINCS. Res. Sq. 2020, rs.3, rs-25643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, B.M.; Price, D.H. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Garber, M.E.; Fang, S.-M.; Fischer, W.H.; Jones, K.A. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 1998, 92, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, S.; Gatignol, A. HIV-1 TAR RNA: The target of molecular interactions between the virus and its host. Curr. HIV Res. 2005, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.H. P-TEFb, a cyclin-dependent kinase controlling elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 2629–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjo, R.; Sabbah, D.A.; Tropsha, A. Analyzing the Systems Biology Effects of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines to Assess Their Safety and Putative Side Effects. Pathogens 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, T.G.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Gregory, J.S.; Slaughter, C.; Moomaw, C.; Hsu, J.; Cobb, M.H. An insulin-stimulated protein kinase similar to yeast kinases involved in cell cycle control. Science 1990, 249, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, M.; Chen, W.; Cobb, M.H. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3100–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, B.A.; Force, T.; Wang, Y. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the heart: Angels versus demons in a heart-breaking tale. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1507–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, C.; Gibson, S.; Jarpe, M.B.; Johnson, G.L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: Conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Olvera, I.; Chávez-Salinas, S.; Medina, F.; Ludert, J.E.; del Angel, R.M. JNK phosphorylation, induced during dengue virus infection, is important for viral infection and requires the presence of cholesterol. Virology 2010, 396, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hou, X.; Li, X.; Peng, H.; Shi, M.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, X.; Ji, Y.; Yao, Y.; He, C.; et al. Differential gene expressions of the MAPK signaling pathway in enterovirus 71-infected rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, P.P.; Blenis, J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: A family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 320–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, Y.D.; Seger, R. The MEK/ERK cascade: From signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1773, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, P.; Munjhal, A.; Lal, S.K. Influenza virus and cell signaling pathways. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, Ra148–Ra154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.; Pleschka, S.; Planz, O.; Wolff, T. Ringing the alarm bells: Signalling and apoptosis in influenza virus infected cells. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.E.; Brunetti, J.E.; Wachsman, M.B.; Scolaro, L.A.; Castilla, V. Raf/MEK/ERK pathway activation is required for Junín virus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.A.; Silva, P.N.; Pereira, A.C.; De Sousa, L.P.; Ferreira, P.C.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Kroon, E.G.; Ropert, C.; Bonjardim, C.A. The vaccinia virus-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is required for virus multiplication. Biochem. J. 2004, 381, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00404248. Tetra-O-Methyl Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid in Treating Patients with Recurrent High-Grade Glioma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00404248 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Le Sommer, C.; Barrows, N.J.; Bradrick, S.S.; Pearson, J.L.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 promotes flaviviridae entry and replication. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemonnot, B.; Cartier, C.; Gay, B.; Rebuffat, S.; Bardy, M.; Devaux, C.; Boyer, V.; Briant, L. The host cell MAP kinase ERK-2 regulates viral assembly and release by phosphorylating the p6gag protein of HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32426–32434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.J.; Yang, P.L. c-Src protein kinase inhibitors block assembly and maturation of dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3520–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.J.; Medigeshi, G.R.; Meyers, H.L.; DeFilippis, V.; Früh, K.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I.; Nelson, J.A. The Src family kinase c-Yes is required for maturation of West Nile virus particles. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 11943–11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Liang, Y.; Parslow, T.G.; Liang, Y. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors block multiple steps of influenza a virus replication. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2818–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Bradel-Tretheway, B.; Sumagin, S.; Bidlack, J.M.; Dewhurst, S. The human herpesvirus 6 G protein-coupled receptor homolog U51 positively regulates virus replication and enhances cell-cell fusion in vitro. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 11914–11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcaru, O.S.; Artene, S.A.; Barcan, E.; Silosi, C.A.; Stanciu, I.; Danoiu, S.; Tudorache, S.; Tataranu, L.G.; Dricu, A. The Interference between SARS-CoV-2 and Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Signaling in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeneCards-The Human Gene Database. KRR1 Gene—KRR1 Small Subunit Processome Component Homolog. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=KRR1 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- National Library of Medicine—National Center for Biotechnology Information. KRR1 Small Subunit Processome Component Homolog [Homo Sapiens (Human)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/11103 (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Battiste, J.L.; Mao, H.; Rao, N.S.; Tan, R.; Muhandiram, D.R.; Kay, L.E.; Frankel, A.D.; Williamson, J.R. Alpha helix-RNA major groove recognition in an HIV-1 rev peptide-RRE RNA complex. Science 1996, 273, 1547–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Chen, L.; Buettner, J.A.; Hudson, D.; Frankel, A.D. RNA recognition by an isolated alpha helix. Cell 1993, 73, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malim, M.H.; Hauber, J.; Le, S.Y.; Maizel, J.V.; Cullen, B.R. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature 1989, 338, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaphy, S.; Dingwall, C.; Ernberg, I.; Gait, M.J.; Green, S.M.; Karn, J.; Lowe, A.D.; Singh, M.; Skinner, M.A. HIV-1 regulator of virion expression (Rev) protein binds to an RNA stem-loop structure located within the Rev response element region. Cell 1990, 60, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daelemans, D.; Costes, S.V.; Cho, E.H.; Erwin-Cohen, R.A.; Lockett, S.; Pavlakis, G.N. In vivo HIV-1 Rev multimerization in the nucleolus and cytoplasm identified by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 50167–50175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Byrn, R.; Groopman, J.; Baltimore, D. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence for differential gene expression. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 3708–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotman, M.E.; Kim, S.; Buchbinder, A.; DeRossi, A.; Baltimore, D.; Wong-Staal, F. Kinetics of expression of multiply spliced RNA in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of lymphocytes and monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 5011–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizala, J.A.C.; Takahashi, M.; Burnett, J.C.; Ouellet, D.L.; Li, H.; Rossi, J.J. Nucleolar Localization of HIV-1 Rev Is Required, Yet Insufficient for Production of Infectious Viral Particles. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2018, 34, 961–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Bian, Z.; Cai, R.; Chu, P.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yang, D.; Li, C. RIPK3-Dependent Necroptosis Limits PRV Replication in PK-15 Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 664353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Su, L.; Rizo, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.F.; Wang, F.S.; Wang, X. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nailwal, H.; Chan, F.K. Necroptosis in anti-viral inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, N.; Zaru, R.; Micheau, O.; Thome, M.; Attinger, A.; Valitutti, S.; Bodmer, J.L.; Schneider, P.; Seed, B.; Tschopp, J. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.N.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, X.K.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Shao, J.; Han, J. Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3 hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Chen, S.; Liao, D.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, W.; Lei, X.; et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012, 148, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, W.J.; Upton, J.W.; Mocarski, E.S. Viral modulation of programmed necrosis. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.J.; Ingram, J.P.; Ragan, K.B.; Nogusa, S.; Boyd, D.F.; Benitez, A.A.; Sridharan, H.; Kosoff, R.; Shubina, M.; Landsteiner, V.J.; et al. DAI Senses Influenza A Virus Genomic RNA and Activates RIPK3-Dependent Cell Death. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schock, S.N.; Chandra, N.V.; Sun, Y.; Irie, T.; Kitagawa, Y.; Gotoh, B.; Coscoy, L.; Winoto, A. Induction of necroptotic cell death by viral activation of the RIG-I or STING pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.W.; Kaiser, W.J.; Mocarski, E.S. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Omoto, S.; Harris, P.A.; Finger, J.N.; Bertin, J.; Gough, P.J.; Kaiser, W.J.; Mocarski, E.S. Herpes simplex virus suppresses necroptosis in human cells. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Challa, S.; Moquin, D.; Genga, R.; Ray, T.D.; Guildford, M.; Chan, F.K. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 2009, 137, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Schlessinger, J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell 1990, 61, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Jensen, P.; Hunter, T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature 2001, 411, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Lim, J.G.; Hellström, I.; Gentry, L.E. Characterization of vaccinia virus growth factor biosynthetic pathway with an antipeptide antiserum. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.S.; Cooper, J.A.; Moss, B.; Twardzik, D.R. Vaccinia virus growth factor stimulates tyrosine protein kinase activity of A431 cell epidermal growth factor receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 1986, 6, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardzik, D.R.; Brown, J.P.; Ranchalis, J.E.; Todaro, G.J.; Moss, B. Vaccinia virus-infected cells release a novel polypeptide functionally related to transforming and epidermal growth factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 5300–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroobant, P.; Rice, A.P.; Gullick, W.J.; Cheng, D.J.; Kerr, I.M.; Waterfield, M.D. Purification and characterization of vaccinia virus growth factor. Cell 1985, 42, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, C.M.; Way, M.; Smith, G.L. Virus-induced cell motility. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, C.; Yakimovich, A.; Kilcher, S.; Reynoso, G.V.; Fläschner, G.; Müller, D.J.; Hickman, H.D.; Mercer, J. Vaccinia virus hijacks EGFR signalling to enhance virus spread through rapid and directed infected cell motility. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, S.; Koban, R.; Yue, C.; Ellerbrok, H. Inhibition of poxvirus spreading by the anti-tumor drug Gefitinib (Iressa). Antiviral Res. 2011, 89, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhong, G.; Xu, G.; He, W.; Jing, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. elife 2012, 1, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, M.; Saso, W.; Sugiyama, R.; Ishii, K.; Ohki, M.; Nagamori, S.; Suzuki, R.; Aizaki, H.; Ryo, A.; Yun, J.H.; et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a host-entry cofactor triggering hepatitis B virus internalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8487–8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, I.F.; Min-Oo, G.; Kalinowski, A.; Ballon-Landa, E.; Lanier, L.L.; Nadel, J.A.; Koff, J.L. Respiratory virus–induced EGFR activation suppresses IRF1-dependent interferon λ and antiviral defense in airway epithelium. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, C.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, G.; Shan, X.; Tai, W.; Yu, G. Inhibition of Influenza A Virus Infection by Fucoidan Targeting Viral Neuraminidase and Cellular EGFR Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, M.G.; Lee, S.; Stobart, C.C.; Hotard, A.L.; Villenave, R.; Meng, J.; Pretto, C.D.; Shields, M.D.; Nguyen, M.T.; Todd, S.O.; et al. EGFR Interacts with the Fusion Protein of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Strain 2-20 and Mediates Infection and Mucin Expression. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, A.; Mercer, J. Viral apoptotic mimicry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.A.; Ngo, J.A.; Situ, K.; Morizono, K. Roles of phosphatidylserine exposed on the viral envelope and cell membrane in HIV-1 replication. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, G.J.; Casasnovas, J.M.; Umetsu, D.T.; DeKruyff, R.H. TIM genes: A family of cell surface phosphatidylserine receptors that regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 235, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Richard, A.S.; Jackson, C.B.; Ojha, A.; Choe, H. Phosphatidylethanolamine and Phosphatidylserine Synergize To Enhance GAS6/AXL-Mediated Virus Infection and Efferocytosis. J. Virol. 2020, 95, e02079-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoros, A.; Platanitis, E.; Kernbauer-Hölzl, E.; Rosebrock, F.; Müller, M.; Decker, T. Canonical and non-canonical aspects of JAK–STAT signaling: Lessons from interferons for cytokine responses. Front. immunol. 2017, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Pillai, P.S. Innate immunity to influenza virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.; Kershaw, N.J.; Babon, J.J. The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 1984–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, J.F. Shared architecture of hormone binding domains in type I and II interferon receptors. Cell 1990, 61, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babon, J.J.; Lucet, I.S.; Murphy, J.M.; Nicola, N.A.; Varghese, L.N. The molecular regulation of Janus kinase (JAK) activation. Biochem. J. 2014, 462, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, J.; Laurent-Rolle, M.; Shi, P.-Y.; García-Sastre, A. NS5 of dengue virus mediates STAT2 binding and degradation. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5408–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.R.; Moseley, G.W. The dynamic interface of viruses with STATs. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00856-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.V.; Tran, J.T.; Sanchez, D.J. HIV blocks Type I IFN signaling through disruption of STAT1 phosphorylation. Innate Immun. 2018, 24, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, V.C.; Ramanan, A.V.; de Bono, S.; Kartman, C.E.; Krishnan, V.; Liao, R.; Piruzeli, M.L.B.; Goldman, J.D.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.; de Cassia Pellegrini, R. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib for the treatment of hospitalised adults with COVID-19 (COV-BARRIER): A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Armas, L.R.; Gavegnano, C.; Pallikkuth, S.; Rinaldi, S.; Pan, L.; Battivelli, E.; Verdin, E.; Younis, R.T.; Pahwa, R.; Williams, S.L. The Effect of JAK1/2 Inhibitors on HIV Reservoir Using Primary Lymphoid Cell Model of HIV Latency. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 720697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Zagórska, A.; Lew, E.D.; Shrestha, B.; Rothlin, C.V.; Naughton, J.; Diamond, M.S.; Lemke, G.; Young, J.A. Enveloped viruses disable innate immune responses in dendritic cells by direct activation of TAM receptors. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.; Tabib, Y.; Capucha, T.; Mizraji, G.; Nir, T.; Pevsner-Fischer, M.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Heyman, O.; Nussbaum, G.; Bercovier, H. GAS6 is a key homeostatic immunological regulator of host–commensal interactions in the oral mucosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E337–E346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomati, T.; Cham, L.B.; Hamdan, T.A.; Bhat, H.; Duhan, V.; Li, F.; Ali, M.; Lang, E.; Huang, A.; Naser, E. Dead cells induce innate anergy via mertk after acute viral infection. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 3671–3681.e3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Li, L.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Yu, S.; Zhou, M.; Luo, Y.; Sun, Y. MERTK is a host factor that promotes classical swine fever virus entry and antagonizes innate immune response in PK-15 cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, S.D.; Schmid, S.L. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 2003, 422, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, G.; Barouch-Bentov, R.; Ziv-Av, A.; Gerber, D.; Jacob, Y.; Einav, S. Identification and targeting of an interaction between a tyrosine motif within hepatitis C virus core protein and AP2M1 essential for viral assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovackova, S.; Chang, L.; Bekerman, E.; Neveu, G.; Barouch-Bentov, R.; Chaikuad, A.; Heroven, C.; Šála, M.; De Jonghe, S.; Knapp, S.; et al. Selective Inhibitors of Cyclin G Associated Kinase (GAK) as Anti-Hepatitis C Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3393–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Schelhaas, M.; Helenius, A. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 803–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, P.; Marzi, A.; Biedenkopf, N.; Beimforde, N.; Becker, S.; Hoenen, T.; Feldmann, H.; Schnittler, H.J. Ebola virus enters host cells by macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204 (Suppl. 3), S957–S967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, V.; Chattu, V.K.; Popli, R.K.; Galwankar, S.C.; Kelkar, D.; Sawicki, S.G.; Stawicki, S.P.; Papadimos, T.J. The Emergence of Zika Virus as a Global Health Security Threat: A Review and a Consensus Statement of the INDUSEM Joint working Group (JWG). J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, R.D.; Kuhl, B.D.; Mesplède, T.; Münch, J.; Donahue, D.A.; Wainberg, M.A. Productive entry of HIV-1 during cell-to-cell transmission via dynamin-dependent endocytosis. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8110–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, R.; Pu, S.Y.; Froeyen, M.; Lescrinier, E.; Einav, S.; Herdewijn, P.; De Jonghe, S. Cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) affinity and antiviral activity studies of a series of 3-C-substituted isothiazolo [4,3-b]pyridines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 163, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.Y.; Wouters, R.; Schor, S.; Rozenski, J.; Barouch-Bentov, R.; Prugar, L.I.; O’Brien, C.M.; Brannan, J.M.; Dye, J.M.; Herdewijn, P.; et al. Optimization of Isothiazolo [4,3-b]pyridine-Based Inhibitors of Cyclin G Associated Kinase (GAK) with Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 6178–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gualda, B.; Pu, S.Y.; Froeyen, M.; Herdewijn, P.; Einav, S.; De Jonghe, S. Structure-activity relationship study of the pyridine moiety of isothiazolo [4,3-b]pyridines as antiviral agents targeting cyclin G-associated kinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kovackova, S.; Pu, S.; Rozenski, J.; De Jonghe, S.; Einav, S.; Herdewijn, P. Isothiazolo [4,3-b]pyridines as inhibitors of cyclin G associated kinase: Synthesis, structure-activity relationship studies and antiviral activity. Medchemcomm 2015, 6, 1666–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melrose, H.; Lincoln, S.; Tyndall, G.; Dickson, D.; Farrer, M. Anatomical localization of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 in mouse brain. Neuroscience 2006, 139, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, W. Biochemical and molecular features of LRRK2 and its pathophysiological roles in Parkinson’s disease. BMB Rep. 2010, 43, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, P.N.; Chen, S.G.; Wilson-Delfosse, A.L. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2): A key player in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009, 87, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, R.K.; Clifford, D.B.; Franklin, D.R., Jr.; Woods, S.P.; Ake, C.; Vaida, F.; Ellis, R.J.; Letendre, S.L.; Marcotte, T.D.; Atkinson, J.H.; et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 2010, 75, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, H.M.; Combrinck, M.I.; Joska, J.A. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: Antiretroviral regimen, central nervous system penetration effectiveness, and cognitive outcomes. S. Afr. Med. J. 2013, 103, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopcroft, L.; Bester, L.; Clement, D.; Quigley, A.; Sachdeva, M.; Rourke, S.B.; Nixon, S.A. “My body’s a 50 year-old but my brain is definitely an 85 year-old”: Exploring the experiences of men ageing with HIV-associated neurocognitive challenges. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kure, K.; Lyman, W.D.; Weidenheim, K.M.; Dickson, D.W. Cellular localization of an HIV-1 antigen in subacute AIDS encephalitis using an improved double-labeling immunohistochemical method. Am. J. Pathol. 1990, 136, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Zink, W.; Xiong, H.; Gendelman, H.E. HIV-1-associated dementia: A metabolic encephalopathy perpetrated by virus-infected and immune-competent mononuclear phagocytes. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002, 31 (Suppl. 2), S43–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccini, J.M.; Marker, D.F.; Fitzgerald, T.; Barbieri, J.; Kim, C.S.; Miller-Rhodes, P.; Lu, S.M.; Dewhurst, S.; Gelbard, H.A. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 modulates neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity in models of human immunodeficiency virus 1-associated neurocognitive disorders. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 5271–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Dzamko, N.; Prescott, A.; Davies, P.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Q.; Lee, J.D.; Patricelli, M.P.; Nomanbhoy, T.K.; Alessi, D.R.; et al. Characterization of a selective inhibitor of the Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, D.F.; Puccini, J.M.; Mockus, T.E.; Barbieri, J.; Lu, S.M.; Gelbard, H.A. LRRK2 kinase inhibition prevents pathological microglial phagocytosis in response to HIV-1 Tat protein. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardo, D. Toll-like receptors: Activation, signalling and transcriptional modulation. Cytokine 2015, 74, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshwene, P.G.; Moncrieffe, M.C.; Grossmann, J.G.; Kao, C.; Ayaluru, M.; Sandercock, A.M.; Robinson, C.V.; Latz, E.; Gay, N.J. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll-like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 25404–25411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Lo, Y.-C.; Wu, H. Helical assembly in the MyD88–IRAK4–IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature 2010, 465, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, Q.; Ferrao, R.; Shen, C.; Hatcher, J.M.; Buhrlage, S.J.; Gray, N.S.; Wu, H. Crystal structure of human IRAK1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13507–13512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagoe, T.; Sato, S.; Matsushita, K.; Kato, H.; Matsui, K.; Kumagai, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Kawai, T.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Sequential control of Toll-like receptor–dependent responses by IRAK1 and IRAK2. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrao, R.; Zhou, H.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Shaw, D.E.; Li, X.; Wu, H. IRAK4 dimerization and trans-autophosphorylation are induced by Myddosome assembly. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Arron, J.R.; Lamothe, B.; Cirilli, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Shevde, N.K.; Segal, D.; Dzivenu, O.K.; Vologodskaia, M.; Yim, M. Distinct molecular mechanism for initiating TRAF6 signalling. Nature 2002, 418, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Commane, M.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Matsumoto, K.; Li, X. IRAK-mediated translocation of TRAF6 and TAB2 in the interleukin-1-induced activation of NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 41661–41667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhurst, R.J. TGFβ signaling in health and disease. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 790–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Massagué, J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, A.; Sjöblom, T.; Fedorova, L.; Imreh, S.; Beug, H.; Moustakas, A. Sustained TGFβ exposure suppresses Smad and non-Smad signalling in mammary epithelial cells, leading to EMT and inhibition of growth arrest and apoptosis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, R.; White, D.; Muller, W. The phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase signaling network: Implications for human breast cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datto, M.B.; Li, Y.; Panus, J.F.; Howe, D.J.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.-F. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 5545–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.M.; Shu, W.; Cardiff, R.D.; Muller, W.J.; Massagué, J. Transforming growth factor β signaling impairs Neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis while promoting pulmonary metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8430–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, B.; Campbell, N.; Ratner, L. Role of Abl kinase and the Wave2 signaling complex in HIV-1 entry at a post-hemifusion step. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, M.; López-Huertas, M.R.; García-Pérez, J.; Climent, N.; Descours, B.; Ambrosioni, J.; Mateos, E.; Rodríguez-Mora, S.; Rus-Bercial, L.; Benkirane, M. Dasatinib inhibits HIV-1 replication through the interference of SAMHD1 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 106, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.N.; Alt, F.W.; Gerstein, R.M.; Malynn, B.A.; Larsson, I.; Rathbun, G.; Davidson, L.; Müller, S.; Kantor, A.B.; Herzenberg, L.A. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity 1995, 3, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Zhou, C.; Guo, H.; Zheng, M. Effects of BTK signalling in pathogenic microorganism infections. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6522–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, T.H.; Urbaniak, A.M.; Santo, A.I.E.; Danks, L.; Smallie, T.; Williams, L.M.; Horwood, N.J. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase regulates TLR7/8-induced TNF transcription via nuclear factor-κB recruitment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 499, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droebner, K.; Pleschka, S.; Ludwig, S.; Planz, O. Antiviral activity of the MEK-inhibitor U0126 against pandemic H1N1v and highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2011, 92, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battcock, S.M.; Collier, T.W.; Zu, D.; Hirasawa, K. Negative regulation of the alpha interferon-induced antiviral response by the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 4422–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.; Wolff, T.; Ehrhardt, C.; Wurzer, W.J.; Reinhardt, J.; Planz, O.; Pleschka, S. MEK inhibition impairs influenza B virus propagation without emergence of resistant variants. FEBS Lett. 2004, 561, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, L.A.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Suppression of astrovirus replication by an ERK1/2 inhibitor. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 7475–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M.; Pashapour, S. SARS-CoV-2 and the possible role of Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in viral survival: Is this a potential therapeutic strategy for COVID-19? Pharmacology 2021, 106, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, G.; Hu, Y. Protective effects of SP600125 on mice infected with H1N1 influenza A virus. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.C.; Soares-Martins, J.A.; Leite, F.G.; Da Cruz, A.F.; Torres, A.A.; Souto-Padrón, T.; Kroon, E.G.; Ferreira, P.C.; Bonjardim, C.A. SP600125 inhibits Orthopoxviruses replication in a JNK1/2 -independent manner: Implication as a potential antipoxviral. Antiviral Res. 2012, 93, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, G.P.; Chuncharunee, A.; Cheunsuchon, B.; Noisakran, S.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T.; Limjindaporn, T. JNK1/2 inhibitor reduces dengue virus-induced liver injury. Antiviral Res. 2017, 141, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, X.; Fu, M.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, S.J. Inhibition of fowl adenovirus serotype 4 replication in Leghorn male hepatoma cells by SP600125 via blocking JNK MAPK pathway. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 228, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wong, C.; Li, P.; Xie, Y. The role of SARS-CoV protein, ORF-6, in the induction of host cell death. Hong Kong Med. J. 2010, 16, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Hristovski, D.; Schutte, D.; Kastrin, A.; Fiszman, M.; Kilicoglu, H. Drug repurposing for COVID-19 via knowledge graph completion. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 115, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Fukushi, S.; Saijo, M.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and its downstream targets in SARS coronavirus-infected cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, H.J.; de Aguiar, M.; Costa, M.A.; Mendonça, D.C.; Reis, E.V.; Arias, N.E.C.; Drumond, B.P.; Bonjardim, C.A. Evaluation of kinase inhibitors as potential therapeutics for flavivirus infections. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasbach, E.; Hartmayer, C.; Planz, O. Combination of MEK inhibitors and oseltamivir leads to synergistic antiviral effects after influenza A virus infection in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2013, 98, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schräder, T.; Dudek, S.E.; Schreiber, A.; Ehrhardt, C.; Planz, O.; Ludwig, S. The clinically approved MEK inhibitor Trametinib efficiently blocks influenza A virus propagation and cytokine expression. Antiviral Res. 2018, 157, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huntington, K.; Zhang, S.; Carlsen, L.; So, E.Y.; Parker, C.; Sahin, I.; Safran, H.; Kamle, S.; Lee, C.M.; et al. MEK inhibitors reduce cellular expression of ACE2, pERK, pRb while stimulating NK-mediated cytotoxicity and attenuating inflammatory cytokines relevant to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 4201–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, S.M.; Imami, A.; Eby, H.; Henkel, N.D.; Creeden, J.F.; Asah, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Alnafisah, R.; Taylor, R.T.; et al. Identification of candidate repurposable drugs to combat COVID-19 using a signature-based approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendama, W. L1000 connectivity map interrogation identifies candidate drugs for repurposing as SARS-CoV-2 antiviral therapies. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3947–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Halberg, A.; Fong, J.Y.; Guo, J.; Song, G.; Louie, B.; Luedtke, G.R.; Visuthikraisee, V.; Protter, A.A.; Koh, X.; et al. Elucidating host cell response pathways and repurposing therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Leser, G.P.; Lamb, R.A. Repurposing Papaverine as an Antiviral Agent against Influenza Viruses and Paramyxoviruses. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, B.L.; de Oliveira, N.C.; Ritter, M.R.; Tonin, F.S.; Melo, E.B.; Sanches, A.C.C.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Petruco, M.V.; de Mello, J.C.P.; Chierrito, D.; et al. The naturally-derived alkaloids as a potential treatment for COVID-19: A scoping review. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 2686–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, B.; Bojkova, D.; Zaliani, A.; Cinatl, J.; Claussen, C.; Westhaus, S.; Keminer, O.; Reinshagen, J.; Kuzikov, M.; Wolf, M.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 cytopathicity dataset generated by high-content screening of a large drug repurposing collection. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Irannejad, H.; Emami, S. Papaverine, a promising therapeutic agent for the treatment of COVID-19 patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Drug Dev. Res. 2022, 83, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laure, M.; Hamza, H.; Koch-Heier, J.; Quernheim, M.; Müller, C.; Schreiber, A.; Müller, G.; Pleschka, S.; Ludwig, S.; Planz, O. Antiviral efficacy against influenza virus and pharmacokinetic analysis of a novel MEK-inhibitor, ATR-002, in cell culture and in the mouse model. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, A.; Ambrosy, B.; Planz, O.; Schloer, S.; Rescher, U.; Ludwig, S. The MEK1/2 Inhibitor ATR-002 (Zapnometinib) Synergistically Potentiates the Antiviral Effect of Direct-Acting Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, A.; Viemann, D.; Schöning, J.; Schloer, S.; Mecate Zambrano, A.; Brunotte, L.; Faist, A.; Schöfbänker, M.; Hrincius, E.; Hoffmann, H.; et al. The MEK1/2-inhibitor ATR-002 efficiently blocks SARS-CoV-2 propagation and alleviates pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine responses. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, H.; Shehata, M.M.; Mostafa, A.; Pleschka, S.; Planz, O. Improved in vitro Efficacy of Baloxavir Marboxil Against Influenza A Virus Infection by Combination Treatment With the MEK Inhibitor ATR-002. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruchhagen, C.; Jarick, M.; Mewis, C.; Hertlein, T.; Niemann, S.; Ohlsen, K.; Peters, G.; Planz, O.; Ludwig, S.; Ehrhardt, C. Metabolic conversion of CI-1040 turns a cellular MEK-inhibitor into an antibacterial compound. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C.; Ro, J.; André, F.; Loi, S.; Verma, S.; Iwata, H.; Harbeck, N.; Loibl, S.; Huang Bartlett, C.; Zhang, K.; et al. Palbociclib in Hormone-Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]