Abstract

(1) Introduction: There is an increasing literature describing neonates born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-N) and infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 who presented with a severe disease (MIS-C). (2) Methods: To investigate clinical features of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates and infants under six months of age, we used a systematic search to retrieve all relevant publications in the field. We screened in PubMed, EMBASE and Scopus for data published until 10 October 2021. (3) Results: Forty-eight articles were considered, including 29 case reports, six case series and 13 cohort studies. Regarding clinical features, only 18.2% of MIS-N neonates presented with fever; differently from older children with MIS-C, in which gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common manifestation, we displayed that cardiovascular dysfunction and respiratory distress are the prevalent findings both in neonates with MIS-N and in neonates/infants with MIS-C. (4) Conclusions: We suggest that all infants with suspected inflammatory disease should undergo echocardiography, due to the possibility of myocardial dysfunction and damage to the coronary arteries observed both in neonates with MIS-N and in neonates/infants with MIS-C. Moreover, we also summarize how they were treated and provide a therapeutic algorithm to suggest best management of these fragile infants.

Keywords:

neonate; SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; infant; children; infection; autoantibodies; heart; respiratory distress 1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) can infect all age groups. To date, children seem to have a more favourable clinical course of the related disease COVID-19, as observed during the last two years of pandemic [1]. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections seem less frequent even now [2], probably due to the lower expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry receptors in nasal epithelium in both term and preterm neonates, compared with adults [3]. Neonatal cases are mostly linked to horizontal transmission due to familial clusters [4], although the rare possibility of a maternal fetal transmission has been demonstrated by Vivanti et al. [5].

However, there is an increasing literature describing SARS-CoV-2 infected children who become critically sick [6] because of the onset of a multisystem inflammatory syndrome named MIS-C. MIS-C has emerged as a significant COVID-19 related consequence, apparently not sparing neonates and infants, who can even require hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) support to survive [7,8]. This seems temporally associated with a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

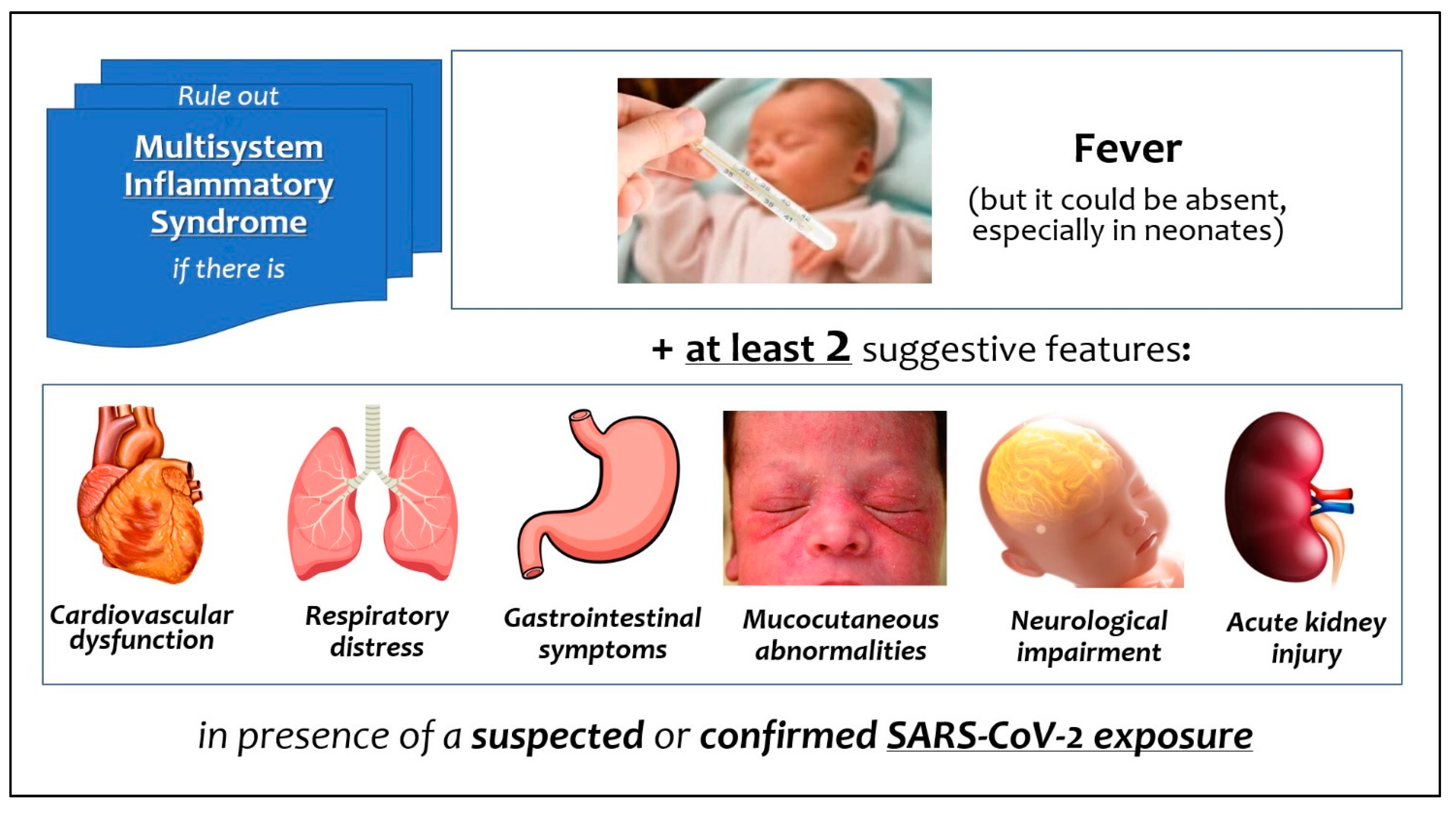

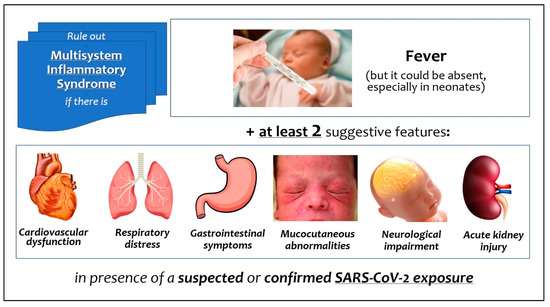

The most frequent mode of onset is fever and multi-organ involvement (Figure 1), associated with a rise in inflammatory biomarkers [9]. A similar multisystem inflammatory syndrome has been documented in adults (MIS-A) [10]. Patients with MIS-C are mostly children older than 7 years [7], but Pawar et al. [11] were the first to distinguish the early neonatal inflammatory syndrome (with onset within one week of life) in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 contracted in pregnancy (MIS-N), from that complicating the neonatal infection contracted after birth [11].

Figure 1.

Signs and symptoms of multisystem inflammatory syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 in neonates and infants.

In this review we conducted a thorough analysis and synthesis of previously described cases of MIS-N and MIS-C in neonates and infants, aiming to describe clinical features of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in these delicate patients. Moreover, we also summarize how these infants were treated, in order to provide preliminary suggestions for management in this new clinical scenario.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed this systematic review following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines throughout the whole project. Prior to commencing the search, a detailed protocol was agreed to determine search modalities, eligibility criteria, and all methodological details. We searched for cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies, as well as case series or case reports published as articles or letters to the editors describing neonates with multisystem inflammatory syndrome following maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-N) or neonates and infants within first six months of life infected with SARS-CoV-2 and with MIS-C features.

We conducted an extensive search of the following databases (accessed on 10 October 2021): PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic) and Embase (https://www.embase.com/?phase=continueToApp#search). We used the following terms: ((“pediatric” AND “multisystem” AND “inflammatory” AND “syndrome”) OR (“multisystem” AND “inflammatory” AND “syndrome” AND “in” AND “children”)) AND “SARS-CoV-2”. Additional studies were identified by authors based on their knowledge in the field, if not already included by literature search. We excluded (1) all retrieved articles written in non-English language; (2) articles which did not clearly report the number of infants under six months of age.

Articles were assessed by independent researchers (DUDR, FP, MC, SR, SC, CM, LM and AS). Investigators evaluated abstracts and (where necessary) the full text of each article, excluding those not meeting the eligibility criteria, and removing duplicates. The CARE (Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline Development) recommendations, specifically dedicated to case reports and series, were followed during the evaluation process. If an article was eligible but reported data on neonates and infants mixed with those on older children, eligible data were directly extracted. If there were uncertainties, they were resolved by discussion between the independent researchers and, if no agreement was reached, with the senior researcher (CA). We developed a dedicated online data extraction sheet (Excel 16: Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Data from included records were independently extracted by each investigator using this data extraction sheet and then cross-verified.

Since we expected the majority of analyzed articles to be case reports or case series, we used the Mayo Evidence-Based Practice Centre tool that is specifically dedicated to the evaluation of case report/series quality [12]. Two investigators (DUDR and CA) independently summarized the results of this evaluation by aggregating the eight binary responses into a 0–8 score. Evaluation results were also qualitatively summarized (Low-Intermediate-Good), as recommended by the tool creators. If discrepancies or uncertainties persisted, they were resolved by discussion between the two researchers (DUDR and CA). We performed calculations and statistics with Excel 16 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), reporting continuous data as median (interquartile range, IQR), and categorical data as numbers and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Workflow of Review and Synthesis

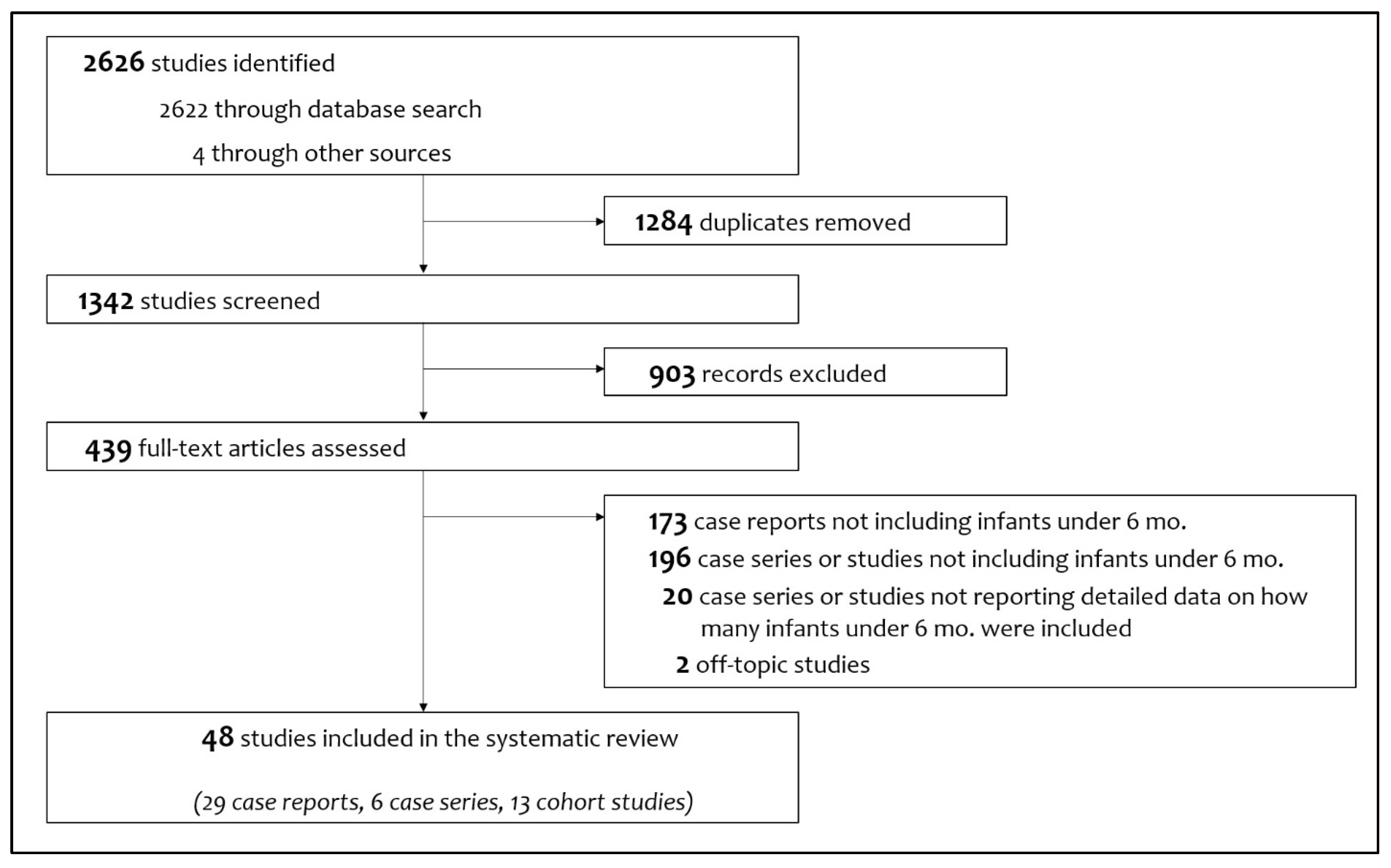

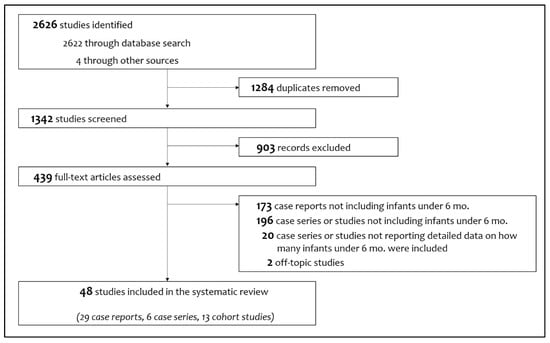

Figure 2 shows the study flow chart with included and excluded items (and the reasons for their exclusions). Finally, 48 articles were considered, consisting of 29 case reports [5,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], six case series [11,41,42,43,44,45] and 13 cohort studies [34,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Figure 2.

Flowchart of study selection process.

We describe in Table 1 the characteristics of the included papers: we assessed as intermediate (median score 5 (5,6)) the methodological quality of case reports, case series and cohort studies which provided supplemental data with case descriptions. Ninety cases of neonates and infants under 6 months of age with multisystem inflammatory syndrome were described in the literature at the time of the search.

Table 1.

Characteristics of articles included in the systematic review. Methodological quality of case description was assessed only for case report and case series, or cohort studies which provided supplemental data with case descriptions.

3.2. Neonates with MIS-N

Thirteen included papers [5,11,14,15,19,20,25,26,29,30,33,38,39] fully described 33 cases of neonates with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in the first week after birth, born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 2). Twenty-four (72.7%) of these neonates, were born preterm, with a median gestational age of 34 [33,34,35,36] weeks and a median birthweight of 2020 [1890–2620] grams. The diagnosis was obtained with a median age of 2 (0–3) days. All infants were admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and 17 (51.5%) of them required mechanical ventilation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of neonates with MIS-N with fully described cases.

Prior maternal SARS-CoV-2 exposure occurred in all infants. Neonatal RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 resulted positive only in four neonates (12.1%), whereas a positive serology yielded a maternal perinatal SARS-CoV-2 infection in 25 cases (75.8%).

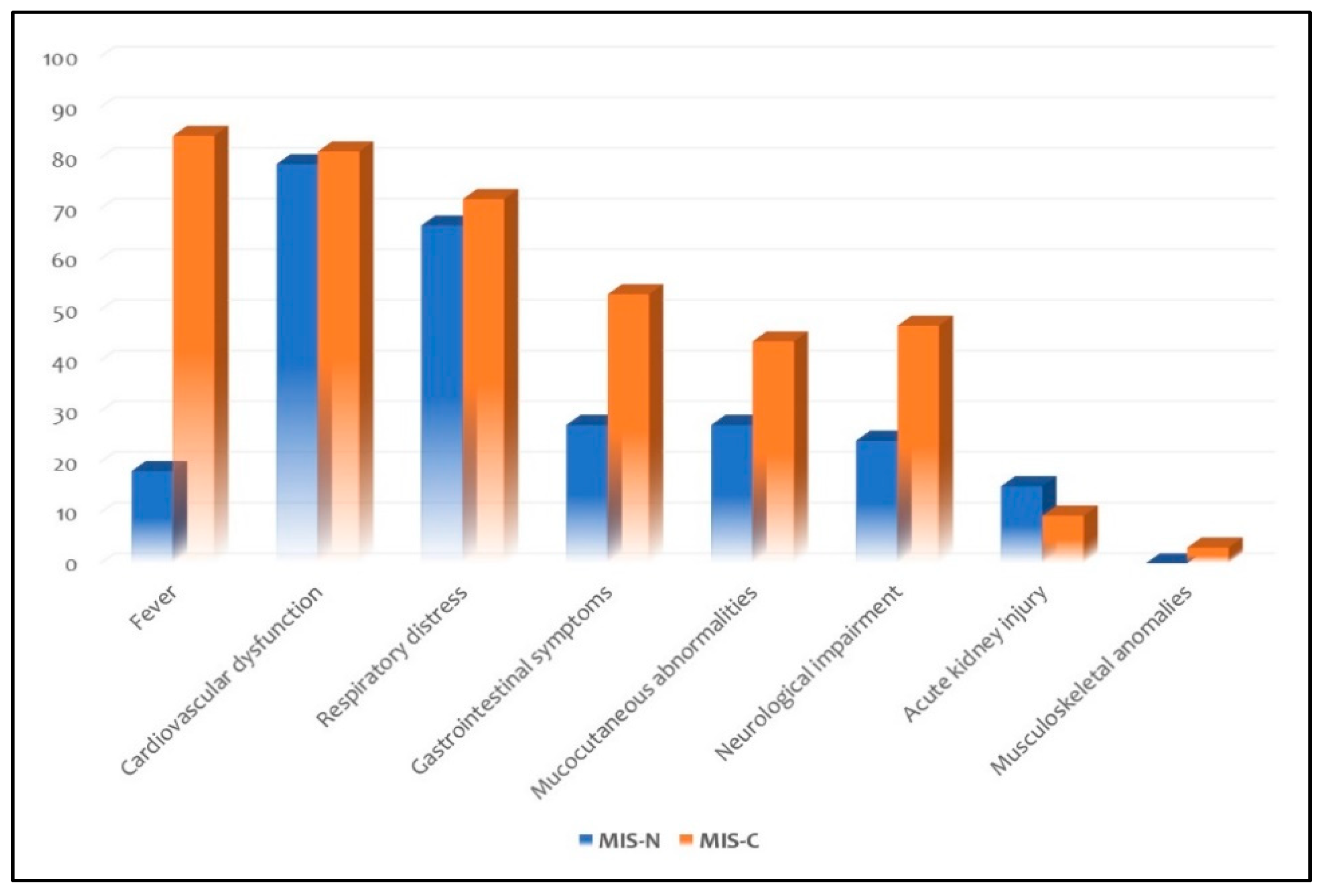

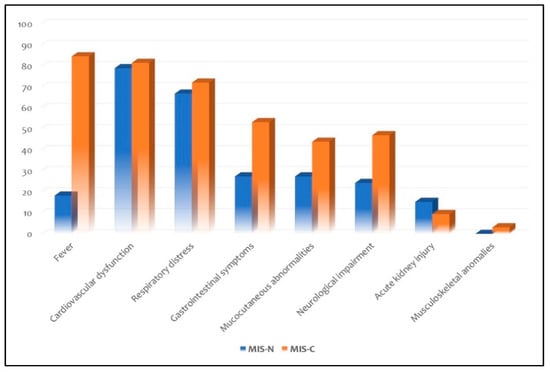

Fever was observed only in six neonates (18.2%). Organ system involvement included cardiovascular dysfunction in 26 neonates (78.8%), respiratory distress in 22 (66.7%), gastrointestinal symptoms in nine (27.3%), mucocutaneous abnormalities in nine (27.3%), neurological impairment in eight (24.2%) and acute kidney injury in five (15.2%). None presented with musculoskeletal anomalies.

Laboratory tests showed mostly an increase in C-reactive protein (60.6%) and procalcitonin (27.3%), raised brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP, 51.5%) and troponin (24.2%), increased D-dimer (84.4%) and interleukin-6 (18.2%), thrombocytopenia (18.2%), metabolic acidosis (15.1%), prolonged prothrombin time (6.1%), and hypoalbuminemia (9.1%).

Chest X-ray or chest CT discovered a pulmonary involvement in 12 neonates (36.4%), whereas echocardiography showed depressed ventricular functions and coronary anomalies in 17 (51.5%).

Twenty-seven neonates (81.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG: a total of 2 g/kg splitted in two infusions of 1 g/kg/day, without a further dose) and intravenous steroids (mostly methylprednisolone). Eighteen neonates (54.5%) needed inotropic support. None was treated with biologic medications or antivirals. The use of large-spectrum antibiotics was described in 10/13 cases (76.9%). Acetylsalicylic acid was given to 6 neonates (18.2%) while thromboprophylaxis was used in 13 cases (39.4%).

The median length of stay was 16 [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] days. The outcome was favourable in 30 neonates (90.9%); of these, a full-term male without comorbidities survived but required amputation of the right leg (because of an acute thrombosis of abdominal aorta) and a late preterm survived after peritoneal dialysis. Only two neonates died (the first on day 8 due to a multi-organ dysfunction and the second on day 11 because of necrotizing enterocolitis).

3.3. Neonates and Infants with MIS-C

Twenty-five included papers [13,16,17,18,21,22,23,24,27,28,31,32,34,35,36,37,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,52,53] describe 32 neonates and infants under the age of six months with multisystem inflammatory syndrome after the acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 3). Only six (18,8%) of these infants, had comorbidities. Thirteen infants (40.6%) required ICU admission, of whom 9/13 (69.2%) undergoing mechanical ventilation. Twenty-one infants (65.6%) had a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2, whereas in 12 (37.5%) previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed by a positive serology. In most cases, MIS-C was related to the positivity for SARS-CoV-2 of a family member in previous days or weeks (where reported): only one infant, hospitalized twice because of a late-onset sepsis, might have contracted the virus as a nosocomial infection.

Table 3.

Characteristics of neonates and infants under six months of age with MIS-C with fully described cases.

Twenty-seven infants (84.4%) presented with fever. Organ system involvement included cardiovascular dysfunctions in 26 infants (81.3%), respiratory distress in 23 (71.9%), gastrointestinal symptoms in 17 (53.1%), neurological impairment in 15 (46.9%), mucocutaneous abnormalities in 14 (43.8%) and acute kidney injury in three (9.4%). Only one (3.1%) presented with fatigue as musculoskeletal anomaly. Laboratory tests showed increase in C-reactive protein (68.8%) more than in procalcitonin (18.8%), elevated ferritin (56.2%), raised brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP, 40.6%) and troponin (34.3%), increased D-dimer (46.9%) and interleukin-6 (21.8%), hypoalbuminemia (34.3%), and thrombocytopenia (15.7%).

Eight infants (25%) presented pulmonary involvement by chest X-ray and/or CT scan, whereas depressed ventricular function and coronaries anomalies were detected by echocardiography in 21 (65.6%).

Twenty-two infants (68.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG: a total of 2 g/kg splitted in two infusions of 1 g/kg/day, without a further dose) and fifteen (46.9%) intravenous steroids (mostly methylprednisolone). Five infants (15.6%) needed inotropic neonatal support. Nine infants (28.1%) received biologic medications (five anakinra, one anakinra and then infliximab, one infliximab, one tocilizumab, one inhaled interferon α-1b). Three infants (9.4%) were treated with remdesivir as antiviral.

The use of large-spectrum antibiotics was described in 17 cases (53.1%). Acetylsalicylic acid was given to 14 infants (43.8%); thromboprophylaxis was used in 14 cases (43.8%) and warfarin was given to one infant (3.1%).

The median length of stay was 15 (10–24) days. The outcome was favourable in 29 infants (90.6%), whereas four infants (12.5%) died: two neonate females within one month of life without comorbidities, a 2-months-old male with a familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to Griscelli syndrome type 2, and a 3-months-old baby with isolated coronary artery disease.

Analyzing data of neonates separately, among infants with MIS-C, only five (15.6%) had less than a month or before reaching term age if preterm born [18,22,37,39,46]. Three of five (60%) had fever. All had a cardiovascular and respiratory involvement, whereas two (40%) had gastrointestinal symptoms. Three (60%) received IVIG and four (80%) steroids. All required ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. Only two neonates (40%) died.

3.4. Differences between Neonates with MIS-N and Neonates with MIS-C

When SARS-CoV-2 infection was acquired postnatally, fever was a frequent feature (60%). rather than in neonates with MIS-N (18.2%). All neonates had a severe course, requiring NICU admission. Organ system involvement was similar for both neonate groups, with prevalent cardiovascular and respiratory signs and symptoms. We found no significant differences between the two groups for laboratory tests and treatments.

Two neonates died in both groups, with a slightly higher incidence in the MIS-C group although not significantly (2/33 MIS-N neonates versus 2/5 MIS-C neonates, p = 0.07).

3.5. Incidence of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome within Six Months of Age

Twelve cohort studies [44,46,47,48,49,50,51,54,55,56,57,58], described 1063 children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome, included 31 infants within six months of age (Table 4). These data allow calculation that 2.9% of reported cases are related to infants younger than six months of age: of these, 10 were neonates (32.3%) and 21 were infants (67.7%).

Table 4.

Characteristics of infants with MIS-N and MIS-C belonging to cohort studies and not fully described.

4. Discussion

This systematic review is the first to synthesize the current data regarding MIS-N in neonates and MIS-C in neonates and infants younger than six months of age. The literature relating to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in these patients is mainly centred on case reports or small case series: we summarized the most frequent clinical features to describe this syndrome in neonates and provide some therapeutic suggestions.

Regarding clinical features, fever is a milestone in older children with MIS-C (99.3%) [59]: we confirmed this trend in young infants with MIS-C (84.4%). Conversely, only the 18.2% of neonates with MIS-N presented with fever, but temperature changes are not a constant finding in the onset of infectious and even in the inflammatory febrile pathologies in preterm and term neonates [60,61]. Therefore, differences in age of MIS-N and MIS-C infants could explain this disparity in fever incidence. Differently from older children with MIS-C, in which gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common manifestation (87.3%) [62], we demonstrated that cardiovascular dysfunction and respiratory distress are the prevalent findings both in neonates with MIS-N and in neonates/infants with MIS-C (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of clinical features in the subgroups of MIS-N and MIS-C.

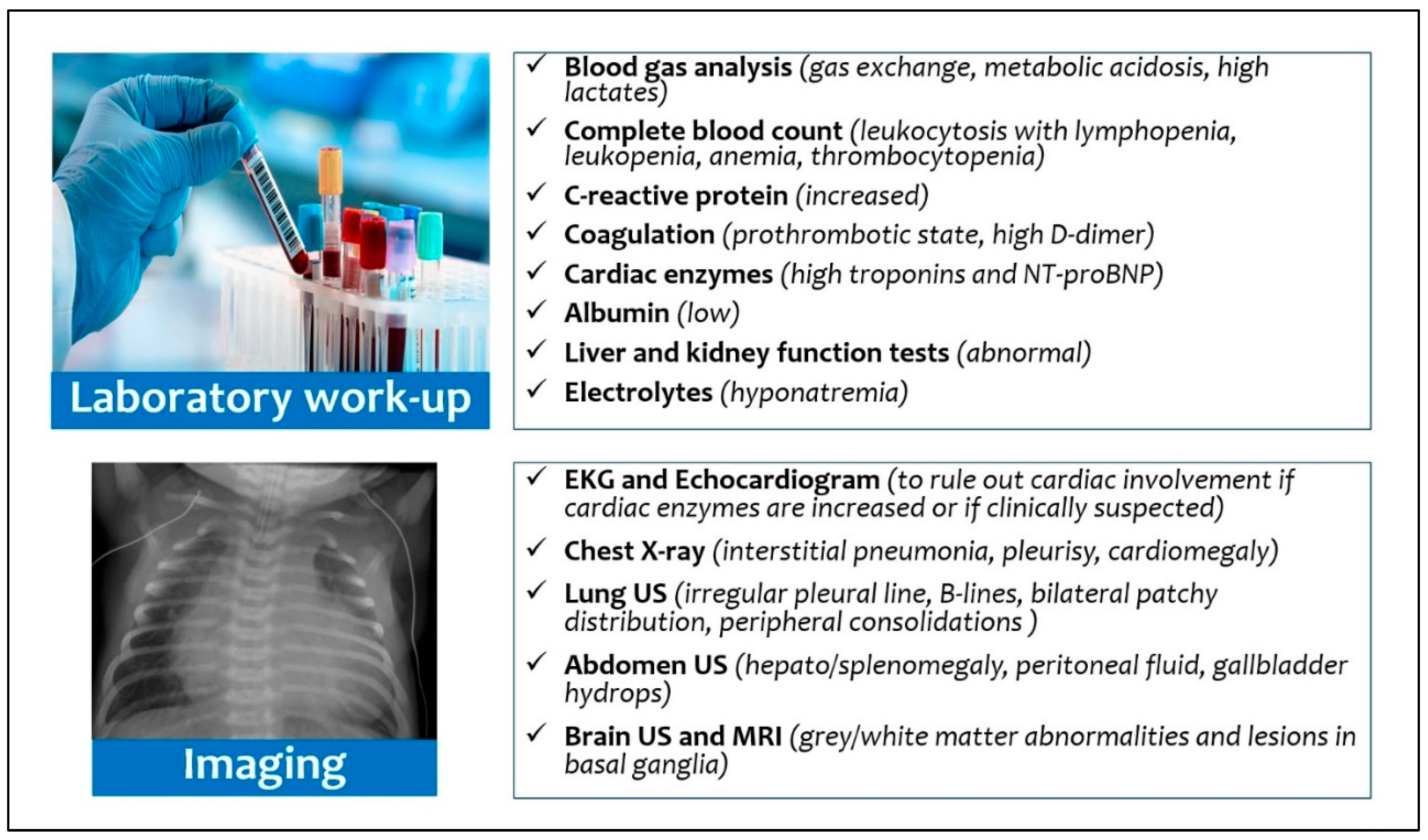

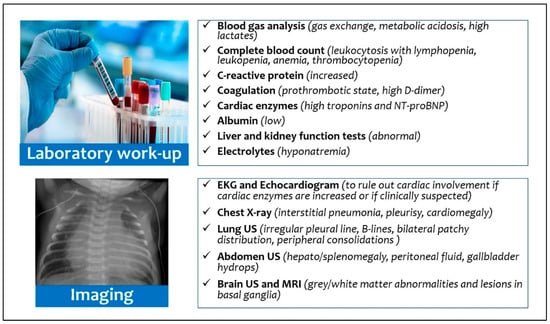

From the diagnostic point of view (Figure 4), although the current diagnostic reference standard for neonatal respiratory distress includes chest X-ray [63], only a third of patients with MIS-N or MIS-C showed pathologic chest X-ray. Recently, Musolino et al. suggested performing lung ultrasound (LUS) in patients with clinical suspicion of MIS-C, or without a certain diagnosis: the finding of many B-lines and pleural effusion would support the diagnosis of a systemic inflammatory disease [64]. Moreover, LUS can also reduce X-ray exposure, but its efficacy as diagnostic tool has been described only in a 6-months-old infant with MIS-C: the authors found an irregular pleural line, B-lines, with bilateral patchy distribution, and small peripheral consolidations [38].

Figure 4.

Diagnostic work-up for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates and infants.

All infants with suspected inflammatory disease should undergo echocardiography, due to the possibility of myocardial dysfunction and damage to the coronary arteries observed both in neonates with MIS-N [11,19,25,26,29,33,38,39] and in neonates/infants with MIS-C [13,18,22,24,28,32,35,36,37,40,41,42,43,45,47,52,53]. Indeed, functional echocardiography can provide a direct bed-side assessment of cardiovascular anomalies and hemodynamics [65]. We suggest performing echocardiography in neonates with MIS-N after 24–48 h of life (or previously in case of symptoms), considering hemodynamic changes that physiologically occur during transition from fetal to neonatal life, while in MIS-C infants echocardiography should be carried on admission. Furthermore, neonates with MIS-N had a higher need of inotropic support (54.5%) than infants with MIS-C (15.6%); targeted echocardiography also offers the advantage of longitudinally assessing infants and their response to therapeutic intervention [66]. The increase in cardiac enzymes (troponin) and cardiac function-related proteins (NT-proBNP) must induce a strong suspicion of myocardial involvement and requires careful monitoring [67]. Additionally, the presence of microvascular dysfunction has recently been characterized in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia [68].

Inflammatory markers could be also raised, but we identified that neonates with MIS-N had lower levels than neonates/infants with MIS-C. Similarly, Zhao et al. assessed that younger children with MIS-C had lower levels of inflammatory markers when compared to middle-age children and adolescents with MIS-C [69].

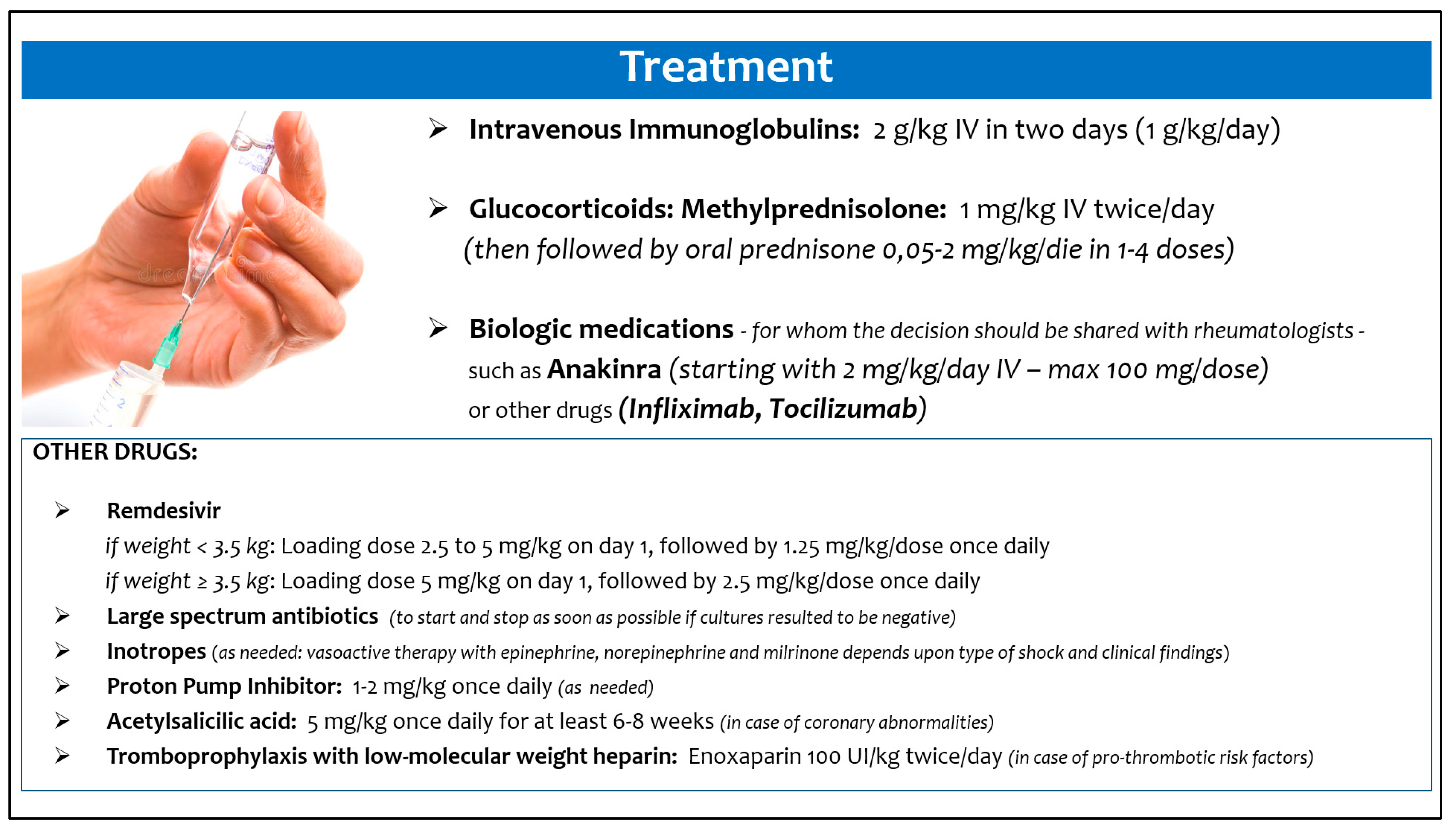

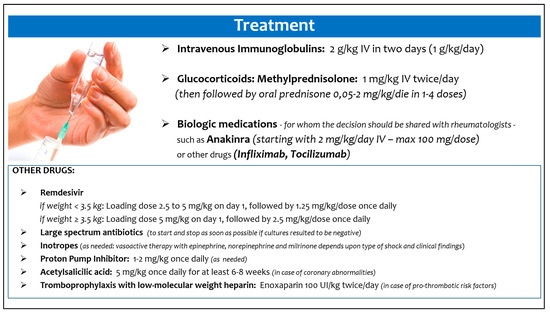

Moreover, we also tried to summarize how these infants were treated, in order to provide preliminary suggestions in management of this new clinical scenario (Figure 5), although data did not come from randomized studies [70]. The best treatment approach and the appropriate timing should be defined on an individual basis, as suggested by Cattalini et al. [71].

Figure 5.

Suggested treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates and infants.

MIS-C and MIS-N seem to originate from immune-mediated mechanisms, in the setting of a suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection: however, in MIS-N the primary source is the maternal infection in pregnancy, with transplacental passage of maternal antibodies [62], whereas in MIS-C the infant contracts a postnatal infection and mounts an antibody response with intact neutralization capability [72]. The efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) in MIS-C, a common approach to activating inhibitory Fc-receptors and preventing membrane-attack complexes by complement factors, thereby mitigating autoantibody-mediated pathology [73], lends support to the hypothesis that autoantibodies contribute to MIS-C pathogenesis [74].

The majority of infants described in the literature received IVIG [11,13,14,19,20,24,25,27,28,34,35,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,47,52,53] and steroids (mostly methylprednisolone) [11,14,15,18,22,25,26,28,31,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,45,52]. According to results of a French study, the treatment with IVIG and methylprednisolone vs IVIG alone was associated with a more favourable course among children with MIS-C [18,22,45]. However, data interpretation is limited by the observational design of the study [75].

Contrarily, antivirals (such as remdesivir) were poorly used (in none of the neonates with MIS-N and only 9.4% of infants with MIS-C) [18,22,45]. Similarly, biologic medications were not given to neonates with MIS-N, whereas about a third of infants with MIS-C required treatment with anakinra, infliximab, tocilizumab, and inhaled interferon α-1b [16,34,36,40,44,45,47].

Most neonates and infants were also treated with large-spectrum antibiotics, given the overlapping clinical signs and symptoms with those of sepsis. Recently, Yock-Corrales and colleagues set the alarm regarding the high rate of antibiotic prescriptions (24.5%) in children with COVID-19 (in particular in those with more severe forms) [76]. Considering the high need for ICU admission in neonates with MIS-N (100%) and infants with MIS-C (40.6%) described in the included studies of this review, and given that an antibiotic treatment is often guaranteed in younger infants, the length of antibiotic therapy should be carefully evaluated: reducing patient exposure to large-spectrum antibiotics can result in avoiding the spread of multi-drug resistant organisms [77]. The time to positivity of blood cultures performed on admission could guide decisions on antibiotics administration in neonates, because most bacterial pathogens grow within 48 h [78,79].

Although the outcome was favourable in the majority of cases, the observed mortality was 9.2% in neonates with MIS-N and infants younger than under six months with MIS-C. Conversely, the reported mortality rate was 1.9% when all pediatric MIS-C cases reported in the literature were considered [59]. This is an expected finding, considering the higher cardiovascular and respiratory involvement in younger infants.

This study had several limitations. First, the available studies were mostly case reports or case series, with possible selection biases. Second, data on some variables were not accessible in all papers or were not uniformly reported. Third, there is no consensus about diagnostic criteria in MIS-C, whereas recently Pawar et al. proposed modified criteria for MIS-N [11]. Fourth, most of these data have been obtained in the “pre-Omicron” period. Indeed, since late November 2021, with the emergence of the new SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.529 (named Omicron), the number of COVID-19 cases increased substantially. Although the symptoms of the new cases are reported to be mild to moderate [80], we do not know what the actual impact will be in younger infants, for whom a vaccine is not yet available.

5. Conclusions

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome, named MIS-N or MIS-C, related to SARS-CoV-2 exposure can occur in a high percentage of neonates and infants. In affected neonates common findings are cardiac dysfunction and the coronary artery dilation or aneurysms; thus, a complete echocardiography is strongly recommended in the diagnostic approach.

The studies that we have consulted reported an overall good prognosis, despite the frequent need of NICU and ICU admissions.

Further epidemiological, clinical, immunological, and neurodevelopmental studies are needed to better clarify short- and long-term outcomes of neonates and infants with this inflammatory condition related to SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.U.D.R. and C.A.; Methodology, D.U.D.R. and C.A.; Formal analysis, D.U.D.R., F.P., M.C., S.R., S.C., C.M., L.M. and A.S.; Data curation, D.U.D.R., F.P., M.C., S.R., S.C., C.M., L.M. and A.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, D.U.D.R., F.P. and C.M.; Writing—review and editing, A.D. and C.A.; Supervision, C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the included articles. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Viner, R.M.; Mytton, O.T.; Bonell, C.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Ward, J.; Hudson, L.; Waddington, C.; Thomas, J.; Russell, S.; van der Klis, F.; et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection among Children and Adolescents Compared with Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auriti, C.; De Rose, D.U.; Mondì, V.; Stolfi, I.; Tzialla, C. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Practical Tips. Pathogens 2021, 10, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, S.; Helve, O.; Andersson, S.; Janér, C.; Süvari, L.; Kaskinen, A. Nasal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry receptors in newborns. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 2022, 107, F95–F97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivini, N.; Calò Carducci, F.I.; Santilli, V.; De Ioris, M.A.; Scarselli, A.; Alario, D.; Geremia, C.; Lombardi, M.H.; Marabotto, C.; Mariani, R.; et al. A neonatal cluster of novel coronavirus disease 2019: Clinical management and considerations. Ital. J. Ped. 2020, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivanti, A.J.; Vauloup-Fellous, C.; Prevot, S.; Zupan, V.; Suffee, C.; Do Cao, J.; Benachi, A.; De Luca, D. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.; Radia, T.; Harman, K.; Agrawal, P.; Cook, J.; Gupta, A. COVID-19 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: A systematic review of critically unwell children and the association with underlying comorbidities. Eur. J. Ped. 2021, 180, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Tang, K.; Levin, M.; Irfan, O.; Morris, S.K.; Wilson, K.; Klein, J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e276–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, V.L.; Shust, G.F.; Ratner, A.J. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Curr. Opin. Ped. 2021, 33, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Principi, N. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Related to SARS CoV 2. Pediatr. Drugs. 2021, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.B.; Schwartz, N.G.; Patel, P.; Abbo, L.; Beauchamps, L.; Balan, S.; Lee, E.H.; Paneth-Pollak, R.; Geevarughese, A.; Lash, M.K.; et al. Case Series of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection—United Kingdom and United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.; Gavade, V.; Patil, N.; Mali, V.; Girwalkar, A.; Tarkasband, V.; Loya, S.; Chavan, A.; Nanivadekar, N.; Shinde, R.; et al. Neonatal multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-N) associated with prenatal maternal SARS-CoV-2: A case series. Children 2021, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, M.H.; Sultan, S.; Haffar, S.; Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Acharyya, B.C.; Acharyya, S.; Das, D. Novel Coronavirus Mimicking Kawasaki Disease in an Infant. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, G.; Wazir, S.; Arora, A.; Sethi, S.K. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a neonate masquerading as surgical abdomen. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e246579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonkar, P.S.; Gavhane, J.B.; Kharche, S.N.; Kadam, S.S.; Bhusare, D.B. Aortic thrombosis in a neonate with COVID-19-related fetal inflammatory response syndrome requiring amputation of the leg: A case report. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2021, 41, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Tian, M.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, K.; et al. A 55-day-old female infant infected with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: Presenting with pneumonia, liver injury, and heart damage. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barba, P.; Canarutto, D.; Sala, E.; Frontino, G.; Guarneri, M.P.; Camesasca, C.; Baldoli, C.; Esposito, A.; Barera, G. COVID-19 cardiac involvement in a 38-day old infant. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 1879–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggikar, S.; Nanjegowda, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Kulkarni, S.; Venkatagiri, P. Neonatal Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divekar, A.A.; Patamasucon, P.; Benjamin, J.S. Presumptive Neonatal Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Am. J. Perinatol. 2021, 38, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwakar, K.; Gupta, B.K.; Uddin, M.W.; Sharma, A.; Jhajra, S. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome with persistent neutropenia in neonate exposed to SARS-CoV-2 virus: A case report and review of literature. J. Neonatal. Perinatal. Med. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugue, R.; Cay-Martínez, K.C.; Thakur, K.T.; Garcia, J.A.; Chauhan, L.V.; Williams, S.H.; Briese, T.; Jain, K.; Foca, M.; McBrian, D.K.; et al. Neurologic manifestations in an infant with COVID-19. Neurology 2020, 94, 1100–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frauenfelder, C.; Brierley, J.; Whittaker, E.; Perucca, G.; Bamford, A. Infant with SARS-CoV-2 infection causing severe lung disease treated with remdesivir. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Howard, M.; Herranz-Aguirre, M.; Moreno-Galarraga, L.; Urretavizcaya-Martínez, M.; Alegría-Echauri, J.; Gorría-Redondo, N.; Planas-Serra, L.; Schlüter, A.; Gut, M.; Pujol, A.; et al. Case Report: Benign Infantile Seizures Temporally Associated With COVID-19. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomet, V.; Manfredini, V.A.; Meraviglia, G.; Peri, C.F.; Sala, A.; Longoni, E.; Gasperetti, A.; Stracuzzi, M.; Mannarino, S.; Zuccotti, G.V. Acute inflammation and elevated cardiac markers in a two-month-old infant with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection presenting with cardiac symptoms. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, e149–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappanayil, M.; Balan, S.; Alawani, S.; Mohanty, S.; Leeladharan, S.P.; Gangadharan, S.; Jayashankar, J.P.; Jagadeesan, S.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.; et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a neonate, temporally associated with prenatal exposure to SARS-CoV-2: A case report. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaund Borkotoky, R.; Banerjee Barua, P.; Paul, S.P.; Heaton, P.A. COVID-19-Related Potential Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Childhood in a Neonate Presenting as Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e162–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, V.G.; Mills, M.; Suarez, D.; Hogan, C.A.; Yeh, D.; Segal, J.B.; Nguyen, E.L.; Barsh, G.R.; Maskatia, S.; Mathew, R. COVID-19 and Kawasaki Disease: Novel Virus and Novel Case. Hosp. Pediatr. 2020, 10, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, S.S.; Suryawanshi, P.B.; Jadhav, P.; Kait, S.P.; Lad, P.; Mujawar, J.; Khetre, R.; Kataria, P.; Balte, P.; Neela, A.; et al. Fresh Per Rectal Bleeding in Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally Associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS). Indian J. Pediatr. 2021, 88, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.; Cardoso, C.C.; Bentim, P.; Voloch, C.M.; Rossi, Á.D.; da Costa, R.; da Paz, J.; Agostinho, R.F.; Figueiredo, V.; Júnior, J.; et al. Maternal SARS-CoV-2 Infection Associated to Systemic Inflammatory Response and Pericardial Effusion in the Newborn: A Case Report. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, N.; Treptow, A.; Schmidt, S.; Hofmann, R.; Raumer-Engler, M.; Heubner, G.; Gröber, K. Neonatal Early-Onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a newborn presenting with encephalitic symptoms. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna Santiago, L.; Aguilar-Martinez, N.; Cabanas-Espinosa, B.; Ramirez-Machuca, X. SARS-CoV-2-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in familial refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 22, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, R.; Liu, H. Severe transient pancytopenia with dyserythropoiesis and dysmegakaryopoiesis in COVID-19–associated MIS-C. Blood 2020, 136, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, K.L.; Tucker, M.; Lee, G.; Pandey, V. Fetal inflammatory response syndrome associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020010132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlanski-Meyer, E.; Yogev, D.; Auerbach, A.; Megged, O.; Glikman, D.; Hashkes, P.J.; Bar-Meir, M. Multisystem Inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2 in an 8-week old infant. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 9, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.; Roychowdhoury, S.; Bhakta, S.; Sarkar, M.; Nandi, M. Incomplete Kawasaki Disease as Presentation of COVID-19 Infection in an Infant: A Case Report. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, M.; Rodríguez-Campoy, P.; Sánchez-Códez, M.; Gutiérrez-Rosa, I.; Castellano-Martinez, A.; Rodríguez-Benítez, A. New onset severe right ventricular failure associated with COVID-19 in a young infant without previous heart disease. Cardiol. Young. 2020, 30, 1346–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Pal, P.; Mukherjee, D. Neonatal MIS-C: Managing the Cytokine Storm. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020042093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, S.; Snijder, P.; Verdijk, R.M.; Kuiken, T.; Kamphuis, S.; Koopman, L.P.; Krasemann, T.B.; Rousian, M.; Broekhuizen, M.; Steegers, E.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 placental infection and inflammation leading to fetal distress and neonatal multi-organ failure in an asymptomatic woman. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaiba, L.A.; Hadid, A.; Altirkawi, K.A.; Bakheet, H.M.; Alherz, A.M.; Hussain, S.A.; Sobaih, B.H.; Alnemri, A.M.; Almaghrabi, R.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Case Report: Neonatal Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Exposure in Two Cases from Saudi Arabia. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 6, 652857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.L.; Jain, A.; Evans, J.; Uzun, O. Giant coronary artery aneurysm as a feature of coronavirus-related inflammatory syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, L.; Bastard, P.; Martin-Nalda, A.; Carpenter, T.; Bush, D.; Patel, R.; Colobran, R.; Soler-Palacin, P.; Casanova, J.L.; Gans, M.; et al. Atypical Inflammatory Syndrome Triggered by SARS-CoV-2 in Infants with Down Syndrome. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, A.; Varisco, T.; Quattrocchi, G.; Amoroso, A.; Beltrami, D.; Venturiello, S.; Ripamonti, A.; Villa, A.; Andreotti, M.; Ciuffreda, M.; et al. Children with Kawasaki disease or Kawasaki-like syndrome (MIS-C/PIMS) at the time of COVID-19: Are they all the same? Case series and literature review. Reumatismo 2021, 73, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, S.; Sobh, A.; Hager, A.H.; Hafez, M.; Alsawah, G.A.; Abuelkheir, M.M.; Zeid, M.S.; Nahas, M.; Elmarsafawy, H. Cardiac Implications of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated with COVID-19 in Children under the age of Five Years. Cardiol. Young. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaiba, L.A.; Altirkawi, K.; Hadid, A.; Alsubaie, S.; Alharbi, O.; Alkhalaf, H.; Alharbi, M.; Alruqaie, N.; Alzomor, O.; Almughaileth, F.; et al. COVID-19 Disease in Infants Less Than 90 Days: Case Series. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacis-Nunez, D.S.; Hashemi, S.; Nelson, M.C.; Flanagan, E.; Thakral, A.; Rodriguez, F., 3rd; Jaggi, P.; Oster, M.E.; Prahalad, S.; Rouster-Stevens, K.A. Giant Coronary Aneurysms in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JACC Case Rep. 2021, 3, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Haq, N.; Asmar, B.I.; Deza Leon, M.P.; McGrath, E.J.; Arora, H.S.; Cashen, K.; Tilford, B.; Charaf Eddine, A.; Sethuraman, U.; Ang, J.Y. SARS-CoV-2-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: Clinical manifestations and the role of infliximab treatment. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.; Kazzaz, Y.M.; Hameed, T.; Alqanatish, J.; Alkhalaf, H.; Alsadoon, A.; Alayed, M.; Hussien, S.A.; Shaalan, M.A.; Al Johani, S.M. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, clinical characteristics, diagnostic findings and therapeutic interventions at a tertiary care center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antúnez-Montes, O.Y.; Escamilla, M.I.; Figueroa-Uribe, A.F.; Arteaga-Menchaca, E.; Lavariega-Saráchaga, M.; Salcedo-Lozada, P.; Melchior, P.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Tirado Caballero, J.C.; Redondo, H.P.; et al. COVID-19 and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Latin American Children: A Multinational Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 40, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Domínguez, P.; Navallas, M.; Riaza-Martin, L.; Ghadimi Mahani, M.; Ugas Charcape, C.F.; Valverde, I.; D’Arco, F.; Toso, S.; Shelmerdine, S.C.; van Schuppen, J.; et al. Imaging findings of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19. Pediatr. Radiol. 2021, 51, 1608–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, J.; James, E.J.; Verghese, V.P.; Kumar, T.S.; Sundaravalli, E.; Vyasam, S. Clinical Spectrum of Children with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufort, E.M.; Koumans, E.H.; Chow, E.J.; Rosenthal, E.M.; Muse, A.; Rowlands, J.; Barranco, M.A.; Maxted, A.M.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Easton, D.; et al. New York State and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Investigation Team. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children in New York State. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteve-Sole, A.; Anton, J.; Pino-Ramirez, R.M.; Sanchez-Manubens, J.; Fumadó, V.; Fortuny, C.; Rios-Barnes, M.; Sanchez-de-Toledo, J.; Girona-Alarcón, M.; Mosquera, J.M.; et al. Similarities and differences between the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19-related pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome and Kawasaki disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e144554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah, N.U.; Hashmi, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Jaan, A.; Akhtar, A.; Khalid, F.; Farooque, U.; Shera, M.T.; Ali, S.; Javed, A. Kawasaki Disease-Like Features in 10 Pediatric COVID-19 Cases: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2020, 12, e11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfred-Cato, S.; Tsang, C.A.; Giovanni, J.; Abrams, J.; Oster, M.E.; Lee, E.H.; Lash, M.K.; Le Marchand, C.; Liu, C.Y.; Newhouse, C.N.; et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Infants <12 months of Age, United States, May 2020–January 2021. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, M.K.; Gregory, M.J.; Jain, A.; Mohammad, D.; Cashen, K.; Ang, J.Y.; Thomas, R.L.; Valentini, R.P. Acute Kidney Injury in Pediatric Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C): Is There a Difference? Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 692256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güllü, U.U.; Güngör, Ş.; İpek, S.; Yurttutan, S.; Dilber, C. Predictive value of cardiac markers in the prognosis of COVID-19 in children. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 48, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, B.; Pandey, M.; Gupta, D.; Oberoi, T.; Jerath, N.; Sharma, R.; Lal, N.; Singha, C.; Malhotra, B.; Manocha, V.; et al. COVID-19 associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A multicentric retrospective cohort study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Niño-Taravilla, C.; Otaola-Arca, H.; Lara-Aguilera, N.; Zuleta-Morales, Y.; Ortiz-Fritz, P. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, Chile, May-August 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhara, J.; Watanabe, K.; Takagi, H.; Sumitomo, N.; Kuno, T. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Coppola, M.; Gallini, F.; Maggio, L.; Vento, G.; Rigante, D. Overview of the rarest causes of fever in newborns: Handy hints for the neonatologist. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, N.; Müller, W.; Resch, B. Neonates presenting with temperature symptoms: Role in the diagnosis of early onset sepsis. Pediatr. Int. 2012, 54, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminrusimha, S.; Hudak, M.L.; Dimitriades, V.R.; Higgins, R.D. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Neonates following Maternal SARS-CoV-2 COVID-19 Infection. Am. J. Perinatol. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiles, M.; Culpan, A.M.; Watts, C.; Munyombwe, T.; Wolstenhulme, S. Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: Chest X-ray or lung ultrasound? A systematic review. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Musolino, A.M.; Boccuzzi, E.; Buonsenso, D.; Supino, M.C.; Mesturino, M.A.; Pitaro, E.; Ferro, V.; Nacca, R.; Sinibaldi, S.; Palma, P.; et al. The Role of Lung Ultrasound in Diagnosing COVID-19-Related Multisystemic Inflammatory Disease: A Preliminary Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissot, C.; Singh, Y. Neonatal functional echocardiography. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesinger, R.E.; McNamara, P.J. Hemodynamic instability in the critically ill neonate: An approach to cardiovascular support based on disease pathophysiology. Semin. Perinatol. 2016, 40, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi Aski, B.; Manafi Anari, A.; Abolhasan Choobdar, F.; Zareh Mahmoudabadi, R.; Sakhaei, M. Cardiac abnormalities due to multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2021, 33, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, G.; Damiani, E.; Confalone, V.; Scorcella, C.; Casarotta, E.; Gandolfo, C.; Stoppa, F.; Cecchetti, C.; Donati, A. Microvascular dysfunction in pediatric patients with SARS-COV-2 pneumonia: Report of three severe cases. Microvasc. Res. 2022, 141, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yin, L.; Patel, J.; Tang, L.; Huang, Y. The inflammatory markers of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and adolescents associated with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4358–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, A.J.; Vito, O.; Patel, H.; Seaby, E.G.; Shah, P.; Wilson, C.; Broderick, C.; Nijman, R.; Tremoulet, A.H.; Munblit, D.; et al. BATS Consortium. Treatment of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattalini, M.; Taddio, A.; Bracaglia, C.; Cimaz, R.; Paolera, S.D.; Filocamo, G.; La Torre, F.; Lattanzi, B.; Marchesi, A.; Simonini, G.; et al. Rheumatology Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatrics. Childhood multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 (MIS-C): A diagnostic and treatment guidance from the Rheumatology Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatrics. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, C.N.; Patel, R.S.; Trachtman, R.; Lepow, L.; Amanat, F.; Krammer, F.; Wilson, K.M.; Onel, K.; Geanon, D.; Tuballes, K.; et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell 2020, 183, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazatchkine, M.D.; Kaveri, S.V. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with Intravenous Immune Globulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, C.R.; Cotugno, N.; Sardh, F.; Pou, C.; Amodio, D.; Rodriguez, L.; Tan, Z.; Zicari, S.; Ruggiero, A.; Pascucci, G.R.; et al. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183, 968–981.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldali, N.; Toubiana, J.; Antona, D.; Javouhey, E.; Madhi, F.; Lorrot, M.; Léger, P.L.; Galeotti, C.; Claude, C.; Wiedemann, A.; et al. French COVID-19 Paediatric Inflammation Consortium. Association of Intravenous Immunoglobulins Plus Methylprednisolone vs Immunoglobulins Alone with course of fever in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. JAMA 2021, 325, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yock-Corrales, A.; Lenzi, J.; Ulloa-Gutiérrez, R.; Gómez-Vargas, J.; Antúnez-Montes, O.Y.; Rios Aida, J.A.; Del Aguila, O.; Arteaga-Menchaca, E.; Campos, F.; Uribe, F.; et al. High rates of antibiotic prescriptions in children with COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome: A multinational experience in 990 cases from Latin America. Acta. Paediatr. 2021, 110, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branstetter, J.W.; Barker, L.; Yarbrough, A.; Ross, S.; Stultz, J.S. Challenges of antibiotic stewardship in the pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Perri, A.; Auriti, C.; Gallini, F.; Maggio, L.; Fiori, B.; D’Inzeo, T.; Spans, T.; Vento, G. Time to positivity of blood cultures could inform decisions on antibiotics administration in neonatal early-onset sepsis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzniewicz, M.W.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Li, S.; Walsh, E.M.; Puopolo, K.M. Time to Positivity of Neonatal Blood Cultures for Early-onset Sepsis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.; Rezaei, N. Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant: Development, dissemination, and dominance. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1787–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).