Abstract

Several strategies have been developed to fight viral infections, not only in humans but also in animals and plants. Some of them are based on the development of efficient vaccines, to target the virus by developed antibodies, others focus on finding antiviral compounds with activities that inhibit selected virus replication steps. Currently, there is an increasing number of antiviral drugs on the market; however, some have unpleasant side effects, are toxic to cells, or the viruses quickly develop resistance to them. As the current situation shows, the combination of multiple antiviral strategies or the combination of the use of various compounds within one strategy is very important. The most desirable are combinations of drugs that inhibit different steps in the virus life cycle. This is an important issue especially for RNA viruses, which replicate their genomes using error-prone RNA polymerases and rapidly develop mutants resistant to applied antiviral compounds. Here, we focus on compounds targeting viral structural capsid proteins, thereby inhibiting virus assembly or disassembly, virus binding to cellular receptors, or acting by inhibiting other virus replication mechanisms. This review is an update of existing papers on a similar topic, by focusing on the most recent advances in the rapidly evolving research of compounds targeting capsid proteins of RNA viruses.

1. Introduction

The recent coronavirus pandemic has shown that emerging viruses pose a constant threat that should keep scientists and pharmacists alert. In addition, the search for new antivirals even against currently well-controlled viruses is justified by the risk of the emergence of drug-resistant mutants that occur either spontaneously or are selected in the presence of drugs applied during long-term infections. For the latter reason, new drugs that inhibit viral processes other than the most often targeted replication of the viral genome and virus maturation, are particularly desirable. This applies especially to viruses such as HIV-1, which still cannot be eliminated from infected individuals. The patients are dependent on a lifelong treatment with a combination of drugs preferentially targeting different steps of the virus life cycle. This approach has significantly extended their life expectancy and quality. Despite this undeniable advantage, combination therapy reducing the risk of disease progression is associated with adverse side effects and is very expensive. Moreover, the sword of Damocles still hangs over our heads, i.e., the threat of the emergence of new mutants that may be resistant to currently effective drug combinations. One of the essential steps in the life cycle of any viral replication is the formation of new viral particles mediated by the interaction of viral capsid proteins. Inhibition of this process blocks the virus assembly, thereby inhibiting the virus replication. Alternatively, compounds with the ability to strongly stabilize assembled viral particles can be used as inhibitors of its disassembly, thus inhibiting the steps following the entry of virus particles into the host cell. Viral capsid proteins interact with various host cell factors or cellular receptors, thus the compounds targeting and binding capsid proteins can be used also for the inhibition of interactions essential for the virus life cycle. In this review, we summarize the most current knowledge about compounds that target and interact with viral capsid proteins or assembled viral capsids, thus inhibiting the virus at various stages of its life cycle. We focus on RNA viruses, with one exception, the hepatitis B virus, where replication depends on the error-prone formation of an RNA intermediate, which stimulates the search for new inhibitors capable of alleviating the problem of new mutants resistant to inhibitors.

Since RNA viruses use various low fidelity RNA polymerases, they exhibit a high mutation rate for their replication, leading to high variability of their genome [1]. The presence of these mutations allows the rapid generation of new variants of the virus, resulting not only in the virus being able to evade the immune system but also in the development of their drug resistance [2]. In addition to the lack of proofreading activity of the polymerase, a high mutation rate is associated with the magnitude of the virus replication. Another factor is the size of the virus population. The larger the number of viruses, the greater the possibility of drug-resistant forms of the virus. An important factor is also the virus fitness, i.e., the ability of a given genetic variant to reproduce among other variants. Although mutations causing resistance to a particular drug mainly do not affect the pathogenicity of the virus, they represent a major problem in the treatment of virus infections and justify the search for alternative drugs, preferably with new targets for combination therapy.

4. Hepatitis B Virus Assembly Inhibitors

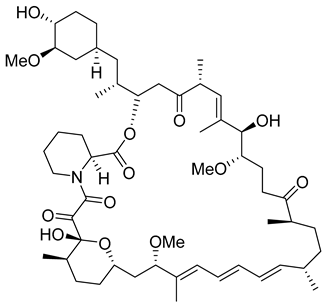

Despite available well-functioning vaccines and inhibitors targeting various steps of the virus life cycle (recently reviewed in [95]), hepatitis B-virus (HBV), an enveloped DNA virus, remains a major health problem [96]. HBV replication depends on a step catalyzed by error-prone reverse transcriptase, and has therefore been included among RNA viruses with low fidelity polymerases in this review. HBV is a causative agent of chronic liver diseases, which may ultimately lead to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. The WHO fact sheet says that: “in 2016, 27 million people (10.5% of all people estimated to be living with hepatitis B) were aware of their infection”. The life cycle of HBV has recently been reviewed [97]. HBV is an enveloped DNA virus that assembles from core protein molecules present in homodimeric subunits into icosahedral T = 4 HBV capsid consisting of 180–240 copies of the core proteins (HBc or named Cp) [98]. The HBc protein is the capsid-forming protein that primarily dimerizes with some structural plasticity [99] manifested by different inter-dimer interfaces of the HBc homodimers named AB, CD, or EF dimers [100]. Most of the published compounds bind to such hydrophobic interfaces and interfere with the assembly of virus particles [101]. Besides these so-called Dane infectious spherical particles of 42 nm in diameter [102], also smaller spherical and filamentous structures with a diameter of 22 nm may be found in the sera of infected individuals. In contrast to the Dane particles, the smaller forms do not contain viral RNA and are thus non-infectious. The multiple roles of the core protein including possible ways of intervention that block the HBV core protein dimerization, capsid assembly, or disassembly have been nicely reviewed [103,104,105].

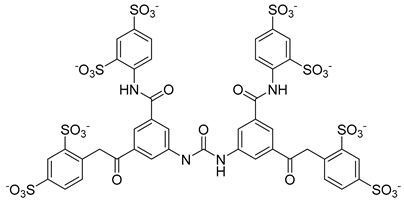

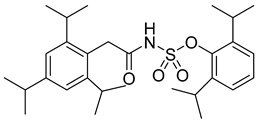

In the last two decades, numerous inhibitors targeting the HBV core protein have been designed. Three structural groups of core protein allosteric modulators are represented primarily by three groups of compounds phenylpropenamides, heteroaryldihydropyrimidines, and sulfamoyl benzamides [106,107,108,109,110,111] (Table 2). According to the mechanism of action, allosteric modulators have been divided into two groups. In type I, some compounds cause misassembly of capsids, resulting in the formation of either aberrant non-infectious particles or protein aggregates. In contrast, type II modulators result in the assembly of virus-like particles with normal morphology but without genomic RNA [112]. Representatives of both groups are currently in clinical trials (for review see [103]).

Importantly, some of these inhibitors block the propagation of HBV mutants resistant to nucleoside analogues [113]. This is a desirable benefit of inhibitors with another mode of action than the frequently used efficient inhibitors of virus genome replication represented mostly by modified nucleosides. Interestingly, acceleration of the assembly by phenylpropenamides may have a similar phenotypic effect in terms of blocking the virus propagation as the heteroaryldihydropyrimidines that induce the assembly of aberrant non-capsid aggregates [114].

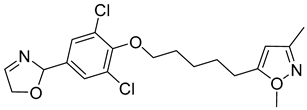

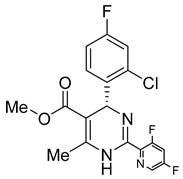

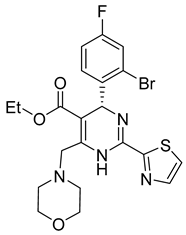

There exists a series of non-nucleoside substituted propenamide derivatives that interfere with the packaging of the viral pregenomic RNA and assembly of immature HBV core particles [114,115]. HAP_R01 (Table 2) which is the member of heteroaryldihydropyrimidine core protein allosteric modulators directly triggers misassembly of HBV [114]. Interestingly, this propenamide derivative binds to the same pocket as the SBA_R01 inhibitor (also titled NVR 3-778) (Table 2) that is representative of the sulfamoylbenzamide group of inhibitors [116]. The structural analysis identified that besides the main binding pocket, there is a unique hydrophobic subpocket in the dimer–dimer interface of HBV core protein hexamer, where fits the thiazole group of HAP_R01, but it is unperturbed by SBA_R01 [116]. The authors concluded that such different mechanisms of inhibitors acting at the same site may help to design suitable molecules to counter the potential resistance of HBV. SBA_R01 is currently in clinical development [117,118]. Moreover, the efficacy of this inhibitor was enhanced by its co-administration with pegylated interferon α [117].

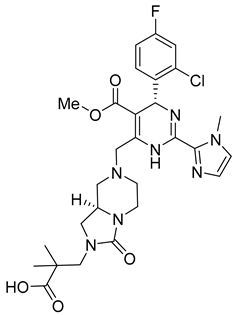

Another orally administered inhibitor is an allosteric modulator of HBV core protein, titled RO7049389 (RG7907) (Table 2), which causes defective capsid assembly [119]. This inhibitor, developed by Roche, showed favorable safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics profile and has been classified as suitable for further clinical development [120]. This compound was also further successfully modified by installing functional moieties to increase the inhibitory activity of SBA_R01 as proved for sulfamoylbenzamide-based compound KR-26556 [121] (Table 2). Especially modifications of positions 4 and 6 with fluorine and methoxy group, respectively, resulted in significant improvement of the inhibitor potency.

The KR-26556 was subjected to further optimization. It was found that the 3,4-difluoro compound is more efficient than the monofluorinated one and changes the conformations of the AB dimer of the HBc protein and the degree of its α-helix flexibility [122]. The transmission electron-microscopic analysis showed that this change induces the formation of aberrant tubular particles. In contrast, the use of some sulfamoylbenzamides, developed in the Schinazi group, led to the formation of aberrant spherical particles that readily aggregated [123]. Another molecule, GLP-26 (Table 2) a glyoxamide derivative, showed high inhibitory potential against HBV capsid assembly [124]. This compound significantly reduced viral replication in an HBV nude mouse model bearing HBV transfected AD38 xenografts [125]. Very promising is the combination therapy using GLP-26 and entecavir. GLP-26 is currently being offered as an HBV capsid assembly modulator by MedChemExpress.

The structure hopping and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies combined with the high throughput screening (HTS) resulted in the identification of a 2-aminothiazole based inhibitor that exhibited anti-HBV replication activity in vitro [126]. Structure modification and SAR led to improved inhibitory efficacy of the sulfamoylbenzamide class compound SBA_R01 (NVR 3-778) (Table 2), which is in phase II clinical trial for the treatment of HBV infection [127]. Similar approaches were used to optimize other compounds; e.g., tetrahydropyrrolopyrimidines based on Bay41_4109 and GLS4 [128], N-phenyl-3-sulfamoyl-benzamide derivative inhibiting HBV capsid assembly in vitro [129] (Table 2), or to explain the enhanced binding of heteroaryldihydropyrimidine inhibitor to the Y132A mutant compared to the wild type of the core protein [130]. 4-oxotetrahydropyrimidine-derived phenyl urea, compound 27 (58031) (Table 2), and some analogues were shown to inhibit HBV by mistargeting the HBc protein to assemble empty capsids devoid of viral pregenomic RNA in human hepatocytes [131]. Jia et al. [132] used molecular modeling based on scaffold hopping and bioisosterism for rational modification of previously published lead compounds isothiafludine (NZ-4) [133] and AT-130 [134] (Table 2). The in silico screening revealed several pyrimidotriazine derivatives, which inhibited HBV assembly both in HepG2.2.15.7 cells and in the in vitro system using TnT® Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) [135].

Using SAR, a new group of HBV assembly modulators based on pyrazolo piperidine scaffold was identified by Kuduk et al. [136]. They found that the attachment of a 6-Me group (S-configuration) increased both the efficiency and metabolic stability of the compound.

Recent clinical studies indicate that core protein (Cp) allosteric modulators may inhibit Cp dimer–dimer interactions not only by interfering with the nucleocapsid assembly and viral DNA replication but also by inducing the disassembly of double-stranded DNA-containing nucleocapsids to prevent the synthesis of cccDNA. Another docking-based virtual screening led to the discovery of 2-aryl-4-quinolyl amide derivate (II-2-9) (Table 2), which blocks the HBV capsid interactions [137].

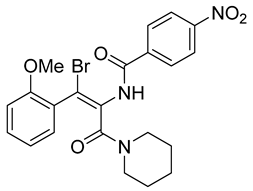

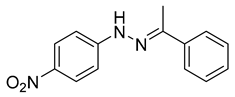

Recently, by screening an in-house compound library, a new molecular motif; N-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylethanone hydrazone (Table 2) was identified as the inhibitor targeting HBV replication by targeting its capsid assembly [138]. This compound accelerates the assembly and induces the formation of empty viral particles lacking genomic RNA.

Table 2.

List of hepatitis B virus assembly inhibitors.

Table 2.

List of hepatitis B virus assembly inhibitors.

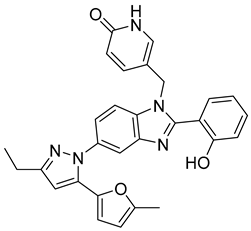

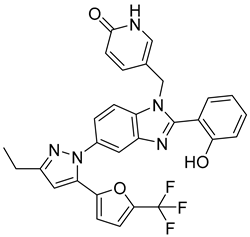

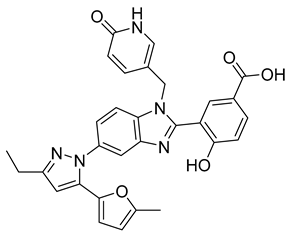

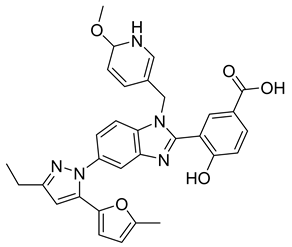

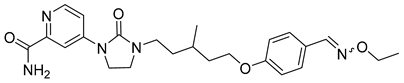

| Compound | Structure | Inhibition Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

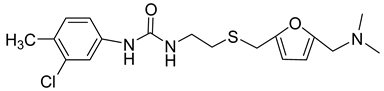

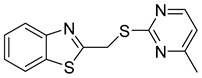

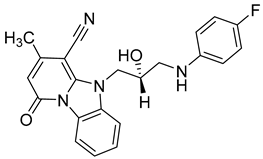

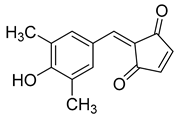

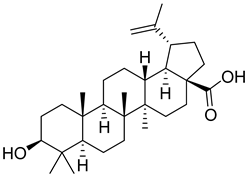

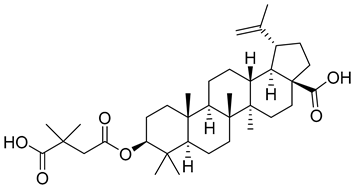

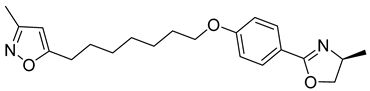

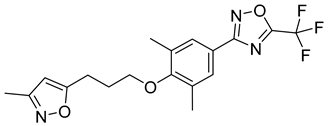

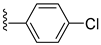

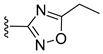

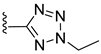

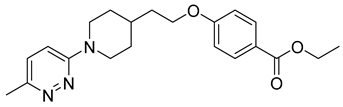

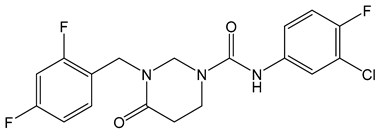

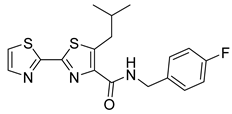

| Bay 41-4109 |  | EC50 0.12 ± 0.026 µM | [139] |

| GLS4 |  | EC50 15 ± 5.3 nM | [139] |

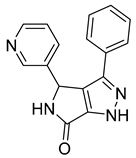

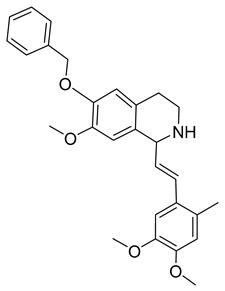

| HAP_R01 |  | EC50 1.12 µM | [114] |

| AT-130 |  | EC50 0.13 µM | [140] |

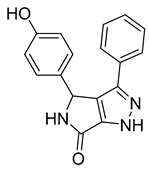

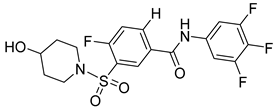

| SBA_R01 (or NVR 3-778) |  | EC50 0.36 ± 0.015 µM | [121] |

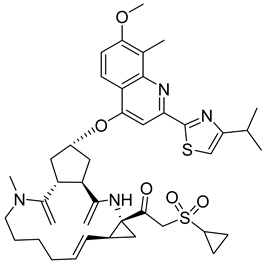

| KR-26556 |  | EC50 40 nM | [121] |

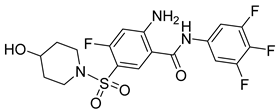

| RO7049389 (RG7907) |  | EC50 6.1 ± 9 nM | [119] |

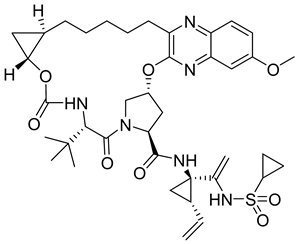

| GLP-26 |  | EC50 3 nM | [141] |

| Compound 27 (58031) |  | EC50 0.52 µM | [141] |

| NZ-4 |  | EC50 1.33 µM | [141] |

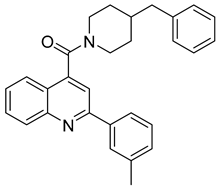

| II-2-9 |  | EC50 1.8 µM | [141] |

| N-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenylethanone hydrazone |  | N.D. |

5. Flavivirus Assembly Inhibitors

5.1. Hepatitis C Virus Assembly Inhibitors

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), a member of flaviviruses, is an enveloped RNA virus encoding one polyprotein precursor of ten proteins of mature virus that are released by the action of both cellular and viral proteases [142]. The assembly of HCV remains only partially understood. It occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum and yields a heterogeneous population of pleomorphic mostly non-infectious particles [143]. It is triggered by the interaction of NS5A protein with mature 21 kDa core protein, which consists of three domains. The N-terminal, basic domain binds viral RNA, the second domain is hydrophobic and less basic, which is optimal for binding to lipid droplets and the last domain contains the signal sequence for the ER membrane translocation. The mechanisms of specific incorporation of viral genomic RNA and regulation of recruitment of subpopulation of lipoproteins and apolipoproteins and heterodimers of HCV E1 and E2 envelope glycoproteins is still poorly explained.

The HCV infection may cause similar chronic liver diseases as mentioned above for HBV, although some HCV infections are either asymptomatic or manifested as acute hepatitis which does not represent a life-threatening disease. However, approximately two-thirds of infected individuals develop chronic HCV infection with a 20% risk of developing cirrhosis within 20 years of infection, which remains a global public health problem [144].

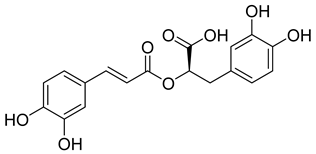

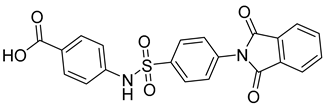

The combination of ribavirin with pegylated interferon α was the preferred anti-HCV therapy, however, its high cost, rather low efficacy together with serious side effects in some patients limit its use [145,146]. Current anti HCV therapy is based on nucleo(s)tides inhibitors (e.g., sofosbuvir) targeting mostly NS5B protein which is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase or NS5A protein, which is an essential component of NS5B and modulates viral replication and other processes [147,148,149]. A major concern connected with the use of these direct-acting antivirals is rapid emergence of drug-resistant variants of HCV due to a poor fidelity of the RNA dependent RNA polymerase [146]. Other efforts are focused on NS3 serine protease and its associated helicase activity [150]. It is known that HCV employs lipid remodeling to increase its replication efficiency [151]. Avasimibe (Table 3), a lipid-lowering drug that inhibits acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase specifically inhibited assembly of HCV by downregulating microsomal triglyceride transfer protein responsible for the formation of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and chylomicrons which are important for the HCV assembly [152,153]. Another HCV assembly inhibitor acting through modulation of lipid metabolism is glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibitor [154]. The human heat shock cognate protein 70 (Hsc70) appears to be also a host cell protein whose inhibition specifically blocks the HCV assembly [155,156,157].

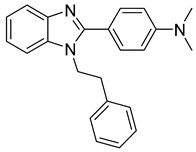

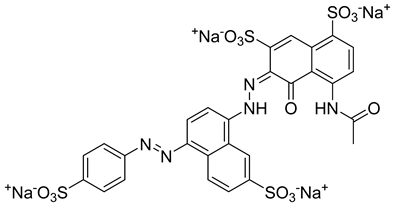

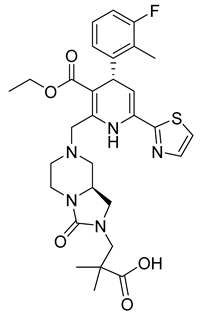

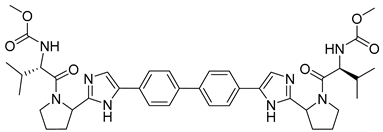

Extensive screening has identified several promising inhibitors that bind to the core protein and potentially inhibit the assembly of HCV particles. Successful drug, daclatasvir (methyl N-[(2S)-1-[(2S)-2-[5-[4-[4-[2-[(2S)-1-[(2S)-2-(methoxycarbonylamino)-3-methylbutanoyl]pyrrolidin-2-yl]-1H-imidazol-5-yl]phenyl]phenyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl]pyrrolidin-1-yl]-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl]carbamate) (Table 3) was approved in 2014 by the European Medicine Agency and in 2016 by the FDA, under the brand name Daklinza. It is usually co-administered with sofosbuvir [158]. It was proposed that daclatasvir blocks the transport of viral RNAs to the assembly sites and thus inhibits viral particle assembly [159].

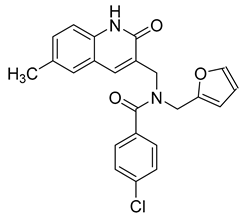

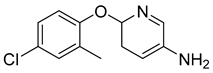

High throughput screening of about 350,000 compounds in a human hepatoma-derived cell line, Huh7.5.1, a suitable infection system for hepatitis C virus, yielded 158 molecules with anti-HCV activity [160]. Later focus on their mechanism of action resulted in the identification of 6-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)pyridin-3-amine (Table 3), which inhibited the viral morphogenesis [161]. Indirect inhibition of assembly was achieved by inhibition of AAK1 and GAK, serine/threonine kinases stimulating binding of clathrin adaptor protein complex 2 to cargo, and are essential for HCV assembly [162]. Fluoxazolevir, an aryloxazole-based compound (Table 3) was shown to inhibit entry of hepatitis C virus by binding to HCV envelope protein 1 and preventing fusion [163].

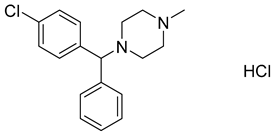

Repurposing already approved drugs seems to be a promising approach also in the treatment of HCV infection. The FDA-approved antihistamine drug chlorcyclizine hydrochloride (Table 3) was found to inhibit some of the late steps of the HCV life cycle, but not likely the assembly [164]. Its efficacy was proved in chimeric mice engrafted with primary human hepatocytes infected with HCV [165].

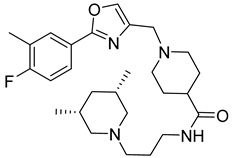

The same laboratory has recently published 4-aminopiperidine-based compounds that inhibit HCV assembly [166]. Moreover, the effect was synergistic with some FDA-approved drugs as broad spectrum antivirals; cyclosporin A and ribavirin or telaprevir and daclatasvir [166].

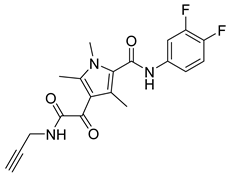

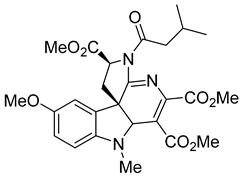

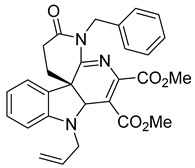

Kota et al. [167] developed the assay for monitoring the dimerization of the HCV core capsid protein, a process that is essential for the formation of virus particles. By the use of capsid protein-derived peptides, they identified two 18-residue peptides that bound to core protein and thus efficiently inhibited its dimerization. These two peptides were also tested on HCV-infected cells but did not show activity to block virus replication, they affected only the virus release. Later, these authors used HTS-TR-FRET for screening of two large libraries, LOPAC, consisting of 1280 molecules, and Boston University library with 2240 compounds to inhibit HCV capsid protein dimerization. Of the 28 positive hits selected, a molecule named SL201 (Table 3) was also tested on the Huh-7.5 cell line infected with HCV 2a J6/JFH-1 strain and found to be effective at micromolar concentration [168]. Thus this molecule was used for its further elaboration together with another three hits from another library screening (molecules were labelled 1–4 [169]). By further modification and dimerization of the most active molecule 2, two indoline alkaloid–type promising inhibitors with IC50 in the nanomolar range (Table 3), were successfully synthesized. In another study, molecules 1 and 2 were biotinylated and tested for their efficient entry into HCV-infected cells where they associated with HCV core [170].

5.2. Dengue Virus Inhibitors

Dengue viruses (DENV) belong to the Flaviviridae family. With almost 400 million infections worldwide they represent one of the main global health burdens. The precise global incidence of dengue fever is uncertain and regional outbreaks occasionally occur. In 2013, it was published that about one third of the human population is at risk of dengue virus infection, with approximately 390 million cases reported per year [171]. This situation is becoming even more serious due to the recently reported large number of dengue-positive animal species and thus a risk of enzootic cycle. The WHO reported 5.2 million cases in 2019, of which about 3.1 million cases were in the American region [172].

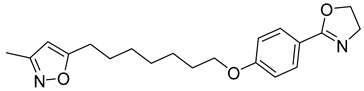

Since DENV exist in four distinct serotypes, the development of an efficient vaccine has been very challenging and quite recently, the first vaccine, CYD-TDV (sold under the brand name Dengvaxia®) was approved by the FDA. Although several effective molecules targeting various steps of DENV replication machinery have been identified (reviewed in [173]), there are still no available potent antiviral therapeutics on the market. The need to find new DENV antivirals is therefore very important. A potent antiviral molecule named ST-148 that targets the capsid protein of DENV was discovered by the HTS of approximately 200,000 chemically diverse compounds by Byrd et al. [174] (Table 3). It inhibits all four serotypes of DENV by binding to its capsid core C protein. ST-148 has a potent in vitro and in vivo activity in low micromolar concentrations (ranging from 0.016 to 2.832 μM) and acts in various cell types. Importantly, it is not cytotoxic. Its exact mode of action on DENV capsid protein was further studied by a combination of several biochemical, virological and imaging-based techniques by Scaturro et al. [175]. The authors found that binding of ST-148 to capsid protein enhances capsid–capsid interactions, stabilizing virus nucleocapsid and thus affecting both the assembly and disassembly of this virus.

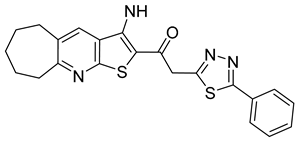

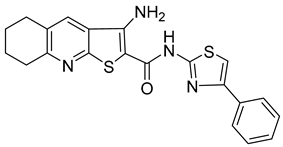

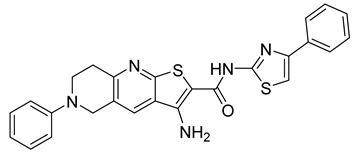

A new compound, 3-amino-6-phenyl-N-(4-phenyl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-b]quinoline-2-carbox-amide (named VGTI-A3) (Table 3) was discovered by HTS of more than 5600 molecules for their effect on DENV-infected cells [176]. Despite its high antiviral activity, it exhibited low solubility and thus a series of its analogues were synthesized. By testing their activities, the compound named VGTI-A3-03 was selected [177] (Table 3). It exhibited a strong antiviral effect not only against all DENV serotypes but also against West Nile virus. Due to its similar structure to the previously found molecule ST-148 (see the text above), it was predicted to have the same or similar mode of action, by binding the capsid protein of DENV. Unfortunately, VGTI-A3-A3 resistant mutants appeared after only a few passages of the DENV infected cells treated with this inhibitor. The resistance-causing mutation was found to be located in the region of DENV capsid protein [177].

Table 3.

List of flavivirus assembly inhibitors.

Table 3.

List of flavivirus assembly inhibitors.

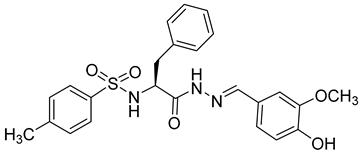

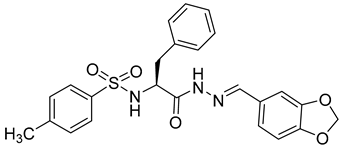

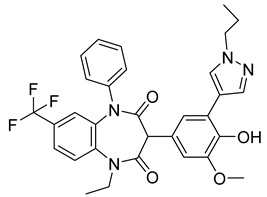

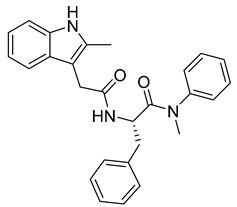

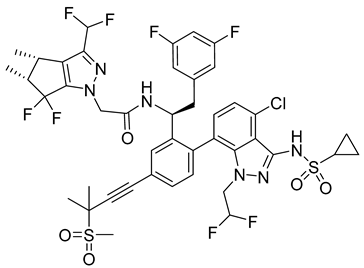

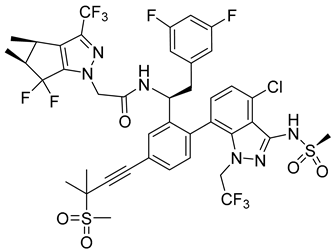

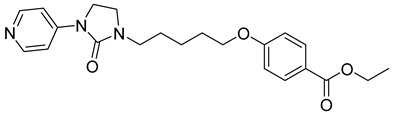

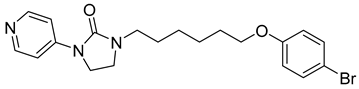

| Compound | Structure | Inhibition Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

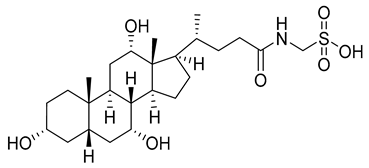

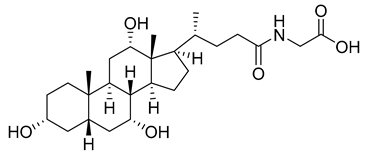

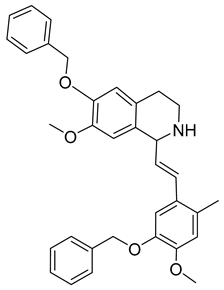

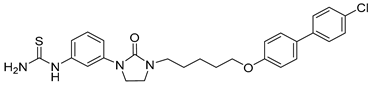

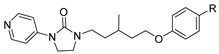

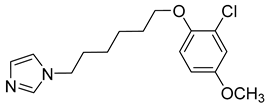

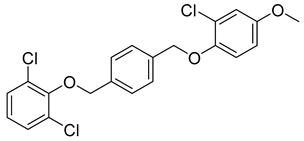

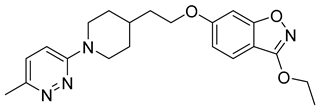

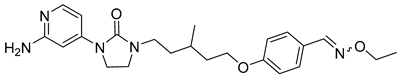

| Hepatitis C virus | |||

| Avasimibe |  | EC50 296 pg/µL | [152] |

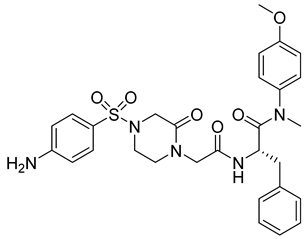

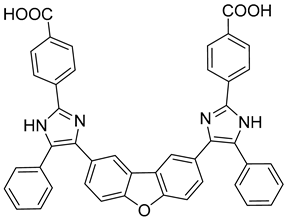

| Daclatasvir |  | EC50 9−146 pM | [158] |

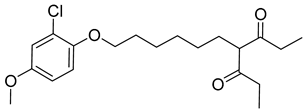

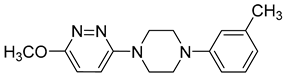

| 6-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)pyridin-3-amine |  | EC50 80 nM | [161] |

| Fluoxazolevir |  | EC50 1.19 µM | [163] |

| Chlorcyclizine hydrochloride |  | EC50 44 ± 11 nM | [164] |

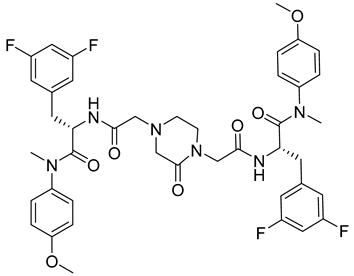

| SL201 |  | EC50 8.1−8.8 µM | [178] |

| Molecule 2 |  | EC50 2.3−3.2 µM | [169] |

| Dengue virus | |||

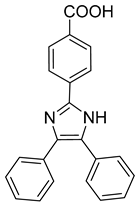

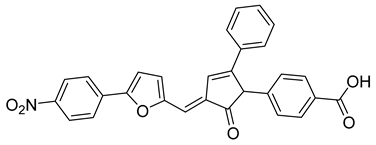

| ST-148 |  | EC50 12−73 nM | [174] |

| VGTI-A3 |  | IC50 0.11 µM | [177] |

| VGTI-A3-03 |  | IC50 25 nM | [177] |

8. Conclusions

Many various antivirals that are currently available on the market exhibit unpleasant or even harmful side effects. In addition, many antivirals, when used for prolonged periods, cause viruses become resistant. Therefore, it is very important to constantly search for new inhibitors that target different steps in the viral life cycle. Here, we have summarized current information about the most relevant compounds that target capsid proteins or viral capsids of clinically relevant virus genera with RNA genomes or using RNA intermediate in their life cycle.

The search for effective antivirals targeting either the viral capsid protein or the assembled capsid was driven by the efforts to obtain inhibitors with a different mechanism of action than commonly used viral enzyme inhibitors and to avoid the risk of resistant mutants through combination therapy, or to have an alternative therapeutic molecule in case of already developed resistance. These compounds can be divided into several groups: inhibitors of the virus capsid assembly, or disassembly, inhibitors preventing the binding of the virus capsid to the host cell receptor, or inhibitors that via their interaction with the capsid protein block packaging of the viral genome. Besides routine applications of the inhibitors, some new strategies have been developed to specifically target the inhibitor to the virus. These involve the fusion of capsid proteins with antiviral molecules that are co-assembled into a virus particle. Antibodies to viral capsid proteins can also be used as potent antivirals. Numerous approaches, including high-throughput screening of available libraries of chemical compounds, targeted drug design, in silico modelling, chemical modifications of currently known compounds, or by the repurposing of already approved drugs have led to the discovery of new inhibitors either of biological or synthetic origin. Their structures range from small organic compounds binding to hydrophobic or interprotomer pockets of the viral capsid, through selected or randomly combined peptides or their fragments that bind to capsid protein interaction interfaces, to compounds binding to capsid protein domains important for their interactions with other viral proteins, genomic nucleic acids, host proteins, or factors necessary for the virus life cycle. The search for inhibitors has helped to elucidate the capsid protein-driven steps of the virus life cycle. Despite some remaining challenges, significant progress has been recently made in the development of effective capsid-targeted inhibitors which, due to their interaction with the essential and thus conservative domains of capsid proteins, represent a very promising alternative to drugs in combination or single-compound therapies.

Author Contributions

L.H. and B.V. contributed equally to this article. Literature review, writing of article L.H., B.V., T.R., and P.U.; Tables, chemical structures B.V. and L.H.; conception of the manuscript, writing and editing of the manuscript, T.R. and P.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the grant LTAUSA17061 provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Drake, J.W.; Holland, J.J. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13910–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.; Arnold, J.J.; Cameron, C.E. Incorporation fidelity of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: A kinetic, thermodynamic and structural perspective. Virus Res. 2005, 107, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.F.; Tolliday, N. Cell-based assays for high-throughput screening. Mol. Biotechnol. 2010, 45, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumlová, M.; Ruml, T. In vitro methods for testing antiviral drugs. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleicher, K.H.; Böhm, H.J.; Müller, K.; Alanine, A.I. Hit and lead generation: Beyond high-throughput screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, G.R.; Nash, H.M.; Jindal, S. Chemical ligands, genomics and drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2000, 5, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharat, T.A.; Davey, N.E.; Ulbrich, P.; Riches, J.D.; de Marco, A.; Rumlova, M.; Sachse, C.; Ruml, T.; Briggs, J.A. Structure of the immature retroviral capsid at 8 Å resolution by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature 2012, 487, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schur, F.K.; Hagen, W.J.; Rumlova, M.; Ruml, T.; Muller, B.; Krausslich, H.G.; Briggs, J.A. Structure of the immature HIV-1 capsid in intact virus particles at 8.8 A resolution. Nature 2015, 517, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, E.O. HIV-1 assembly, release and maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadravová, R.; Rumlová, M.; Ruml, T. FAITH—Fast assembly inhibitor test for HIV. Virology 2015, 486, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostálková, A.; Hadravová, R.; Kaufman, F.; Křížová, I.; Škach, K.; Flegel, M.; Hrabal, R.; Ruml, T.; Rumlová, M. A simple, high-throughput stabilization assay to test HIV-1 uncoating inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, R.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Cheng, A. Capsid-targeted viral inactivation: A novel tactic for inhibiting replication in viral infections. Viruses 2016, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsoulis, G.; Seshaiah, P.; Federspiel, M.J.; Rein, A.; Hughes, S.H.; Boeke, J.D. Targeting of a nuclease to murine leukemia virus capsids inhibits viral multiplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beterams, G.; Nassal, M. Significant interference with Hepatitis B virus replication by a Core-nuclease fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 8875–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.F.; Qin, E.D. Capsid-targeted viral inactivation can destroy dengue 2 virus from within in vitro. Arch. Virol. 2006, 151, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okui, N.; Sakuma, R.; Kobayashi, N.; Yoshikura, H.; Kitamura, T.; Chiba, J.; Kitamura, Y. Packageable antiviral therapeutics against human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Virion-targeted virus inactivation by incorporation of a single-chain antibody against viral integrase into progeny virions. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000, 11, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobinger, G.P.; Borsetti, A.; Nie, Z.; Mercier, J.; Daniel, N.; Göttlinger, H.G.; Cohen, A. Virion-targeted viral inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by using Vpr fusion proteins. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 5441–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, G.; Qin, L.; Rein, A.; Natsoulis, G.; Boeke, J.D. Therapeutic effect of Gag-nuclease fusion protein on retrovirus-infected cell cultures. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4329–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsoulis, G.; Boeke, J.D. New antiviral strategy using capsid-nuclease fusion proteins. Nature 1991, 352, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, G.; Cannon, K.; Ma, W.P.; Crouch, R.J.; Boeke, J.D. Antiretroviral effect of a gag-RNase HI fusion gene. Gene Ther. 1997, 4, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukachevitch, L.V.; Egli, M. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of Escherichia coli RNase HI-dsRNA complexes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2007, 63 Pt 2, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanBrocklin, M.; Ferris, A.L.; Hughes, S.H.; Federspiel, M.J. Expression of a murine leukemia virus Gag-Escherichia coli RNase HI fusion polyprotein significantly inhibits virus spread. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 3312–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, J.; Choi, J.; Oh, C.; Kim, S.; Seo, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Seo, D.; Kim, J.; White, T.E.; Brandariz-Nuñez, A.; et al. The ribonuclease activity of SAMHD1 is required for HIV-1 restriction. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, T.R.; Dhamdhere, G.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Goudy, L.; Zeng, L.; Chemparathy, A.; Chmura, S.; Heaton, N.S.; Debs, R.; et al. Development of CRISPR as an antiviral strategy to combat SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza. Cell 2020, 181, 865–876.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Lei, J.; Li, S.; Xue, C. Adenoviral-vector mediated transfer of HBV-targeted ribonuclease can inhibit HBV replication in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.; Cheng, L.; Chen, J.; Jiang, X.; Zou, S. Construction of transgenic P0 grass carp by capsid-targeted viral inactivation of reovirus. J. Fisher China 2014, 38, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Nangola, S.; Urvoas, A.; Valerio-Lepiniec, M.; Khamaikawin, W.; Sakkhachornphop, S.; Hong, S.S.; Boulanger, P.; Minard, P.; Tayapiwatana, C. Antiviral activity of recombinant ankyrin targeted to the capsid domain of HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Retrovirology 2012, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praditwongwan, W.; Chuankhayan, P.; Saoin, S.; Wisitponchai, T.; Lee, V.S.; Nangola, S.; Hong, S.S.; Minard, P.; Boulanger, P.; Chen, C.-J.; et al. Crystal structure of an antiviral ankyrin targeting the HIV-1 capsid and molecular modeling of the ankyrin-capsid complex. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2014, 28, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sticht, J.; Humbert, M.; Findlow, S.; Bodem, J.; Müller, B.; Dietrich, U.; Werner, J.; Kräusslich, H.G. A peptide inhibitor of HIV-1 assembly in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ternois, F.; Sticht, J.; Duquerroy, S.; Kräusslich, H.G.; Rey, F.A. The HIV-1 capsid protein C-terminal domain in complex with a virus assembly inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozisek, M.; Durcak, J.; Konvalinka, J. Thermodynamic characterization of the peptide assembly inhibitor binding to HIV-1 capsid protein. Retrovirology 2013, 10, P108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Bhattacharya, S.; Waheed, A.A.; Tong, X.; Hong, A.; Heck, S.; Curreli, F.; Goger, M.; Cowburn, D.; et al. A cell-penetrating helical peptide as a potential HIV-1 inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 378, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Zhang, H.; Debnath, A.K.; Cowburn, D. Solution structure of a hydrocarbon stapled peptide inhibitor in complex with monomeric C-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16274–16278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Curreli, F.; Waheed, A.A.; Mercredi, P.Y.; Mehta, M.; Bhargava, P.; Scacalossi, D.; Tong, X.; Lee, S.; Cooper, A.; et al. Dual-acting stapled peptides target both HIV-1 entry and assembly. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzón, M.T.; Lidón-Moya, M.C.; Barrera, F.N.; Prieto, A.; Gómez, J.; Mateu, M.G.; Neira, J.L. The dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein binds a capsid protein-derived peptide: A biophysical characterization. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocanegra, R.; Nevot, M.; Doménech, R.; López, I.; Abián, O.; Rodríguez-Huete, A.; Cavasotto, C.N.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Gómez, J.; Martínez, M.; et al. Rationally designed interfacial peptides are efficient in vitro inhibitors of HIV-1 capsid assembly with antiviral activity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornillos, O.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Kelly, B.N.; Hua, Y.; Whitby, F.G.; Stout, C.D.; Sundquist, W.I.; Hill, C.P.; Yeager, M. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 2009, 137, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Curreli, F.; Zhang, X.; Bhattacharya, S.; Waheed, A.A.; Cooper, A.; Cowburn, D.; Freed, E.O.; Debnath, A.K. Antiviral activity of α-helical stapled peptides designed from the HIV-1 capsid dimerization domain. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Loeliger, E.; Kinde, I.; Kyere, S.; Mayo, K.; Barklis, E.; Sun, Y.; Huang, M.; Summers, M.F. Antiviral inhibition of the HIV-1 capsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 327, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.N.; Kyere, S.; Kinde, I.; Tang, C.; Howard, B.R.; Robinson, H.; Sundquist, W.I.; Summers, M.F.; Hill, C.P. Structure of the antiviral assembly inhibitor CAP-1 complex with the HIV-1 CA protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 373, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevelige, P. Small molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 capsid assembly. U.S. Patent Application No. 12/090,361, 9 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.; He, M.; Tang, S.; Hewlett, I.; Tan, Z.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.; Yang, M. Synthesis and antiviral activities of novel acylhydrazone derivatives targeting HIV-1 capsid protein. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2162–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, J.; Shah, V.B.; Aiken, C.; Whitby, K. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by virus capsid destabilization. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundquist, W.I.; Hill, C.P. How to assemble a capsid. Cell 2007, 131, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lemke, C.T.; Titolo, S.; von Schwedler, U.; Goudreau, N.; Mercier, J.F.; Wardrop, E.; Faucher, A.M.; Coulombe, R.; Banik, S.S.; Fader, L.; et al. Distinct effects of two HIV-1 capsid assembly inhibitor families that bind the same site within the N-terminal domain of the viral CA protein. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6643–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

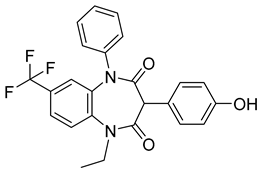

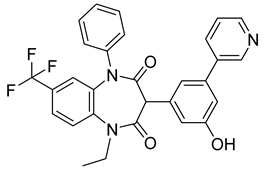

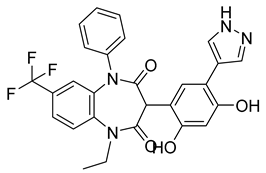

- Fader, L.D.; Bethell, R.; Bonneau, P.; Bös, M.; Bousquet, Y.; Cordingley, M.G.; Coulombe, R.; Deroy, P.; Faucher, A.M.; Gagnon, A.; et al. Discovery of a 1,5-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]diazepine-2,4-dione series of inhibitors of HIV-1 capsid assembly. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

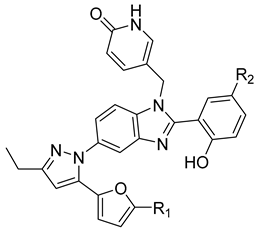

- Goudreau, N.; Lemke, C.T.; Faucher, A.M.; Grand-Maître, C.; Goulet, S.; Lacoste, J.E.; Rancourt, J.; Malenfant, E.; Mercier, J.F.; Titolo, S.; et al. Novel inhibitor binding site discovery on HIV-1 capsid N-terminal domain by NMR and X-ray crystallography. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, E.; Kuramochi, N.; Ichikawa, R.; Murayama, S.Y.; Miyauchi, K.; Tomoda, H.; Takebe, Y.; Nermut, M.; Komano, J.; Morikawa, Y. Novel postentry inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication screened by yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4251–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamo, M.; Tateishi, H.; Koga, R.; Okamoto, Y.; Otsuka, M.; Fujita, M. Synthesis of the biotinylated anti-HIV compound BMMP and the target identification study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, W.S.; Pickford, C.; Irving, S.L.; Brown, D.G.; Anderson, M.; Bazin, R.; Cao, J.; Ciaramella, G.; Isaacson, J.; Jackson, L.; et al. HIV capsid is a tractable target for small molecule therapeutic intervention. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, T.; Brandariz-Nuñez, A.; Wang, X.; Smith, A.B., 3rd; Diaz-Griffero, F. Human cytosolic extracts stabilize the HIV-1 core. J Virol 2013, 87, 10587–10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Alam, S.L.; Fricke, T.; Zadrozny, K.; Sedzicki, J.; Taylor, A.B.; Demeler, B.; Pornillos, O.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Diaz-Griffero, F.; et al. Structural basis of HIV-1 capsid recognition by PF74 and CPSF6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 18625–18630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Ferhadian, D.; Sowd, G.A.; Serrao, E.; Shi, J.; Halambage, U.D.; Teng, S.; Soto, J.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Engelman, A.N.; et al. Roles of capsid-interacting host factors in multimodal inhibition of HIV-1 by PF74. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5808–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yant, S.R.; Mulato, A.; Hansen, D.; Tse, W.C.; Niedziela-Majka, A.; Zhang, J.R.; Stepan, G.J.; Jin, D.; Wong, M.H.; Perreira, J.M.; et al. A highly potent long-acting small-molecule HIV-1 capsid inhibitor with efficacy in a humanized mouse model. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Gallazzi, F.; Hill, K.J.; Burke, D.H.; Lange, M.J.; Quinn, T.P.; Neogi, U.; Sönnerborg, A. GS-CA compounds: First-in-class HIV-1 capsid inhibitors covering multiple grounds. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, L.S.; Agresta, B.E.; Carter, C.A. Assembly of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein in vitro. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 4874–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; von Schwedler, U.K.; Stray, K.M.; Aiken, C.; Sundquist, W.I. Assembly properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, W.C.; Link, J.O.; Mulato, A.; Niedziela-Majka, A.; Rowe, W.; Somoza, J.R.; Villasenor, A.G.; Yant, S.R.; Zhang, J.R.; Zheng, J. Discovery of Novel Potent HIV Capsid Inhibitors with Long-Acting Potential. In Proceedings of the CROI, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–16 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Yant, S.R.; Ahmadyar, S.; Chan, T.Y.; Chiu, A.; Cihlar, T.; Link, J.O.; Lu, B.; Mwangi, J.; Rowe, W.; et al. 539. GS-CA2: A novel, potent, and selective first-in-class inhibitor of HIV-1 capsid function displays nonclinical pharmacokinetics supporting long-acting potential in humans. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 5, pp. S199–S200. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer, E.; Sager, R.B.; Martin, R.; Steve, K.W.; John, L.; Scott, D.S.; Winston, C.T.; Anita, M. Safety and PK of subcutaneous GS-6207, a novel HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. In Proceedings of the CROI, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–7 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Daar, E.S.; McDonald, C.; Crofoot, G.; Ruane, P.; Sinclair, G.; Patel, H.; Begley, R.; Liu, Y.P.; Brainard, D.M.; Hyland, R.H.; et al. Single doses of long-acting capsid inhibitor GS-6207 administered by subcutaneous injection are safe and efficacious in people living with HIV. In Proceedings of the 17th European AIDS Conference, Basel, Switzerland, 6–9 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Link, J.O.; Rhee, M.S.; Tse, W.C.; Zheng, J.; Somoza, J.R.; Rowe, W.; Begley, R.; Chiu, A.; Mulato, A.; Hansen, D.; et al. Clinical targeting of HIV capsid protein with a long-acting small molecule. Nature 2020, 584, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zila, V.; Margiotta, E.; Turoňová, B.; Müller, T.G.; Zimmerli, C.E.; Mattei, S.; Allegretti, M.; Börner, K.; Rada, J.; Müller, B.; et al. Cone-shaped HIV-1 capsids are transported through intact nuclear pores. Cell 2021, 184, 1032–1046.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamorte, L.; Titolo, S.; Lemke, C.T.; Goudreau, N.; Mercier, J.F.; Wardrop, E.; Shah, V.B.; von Schwedler, U.K.; Langelier, C.; Banik, S.S.; et al. Discovery of novel small-molecule HIV-1 replication inhibitors that stabilize capsid complexes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4622–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, T.; Buffone, C.; Opp, S.; Valle-Casuso, J.; Diaz-Griffero, F. BI-2 destabilizes HIV-1 cores during infection and prevents binding of CPSF6 to the HIV-1 capsid. Retrovirology 2014, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganser, B.K.; Li, S.; Klishko, V.Y.; Finch, J.T.; Sundquist, W.I. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 1999, 283, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, J.A.; Kräusslich, H.G. The molecular architecture of HIV. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.J.; Fletcher, A.J.; Schaller, T.; Elliott, T.; Lee, K.; KewalRamani, V.N.; Chin, J.W.; Towers, G.J.; James, L.C. CPSF6 defines a conserved capsid interface that modulates HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Dick, A.; Meuser, M.E.; Huang, T.; Zalloum, W.A.; Chen, C.-H.; Cherukupalli, S.; Xu, S.; Ding, X.; Gao, P.; et al. Design, synthesis, and mechanism study of benzenesulfonamide-containing phenylalanine derivatives as novel HIV-1 capsid inhibitors with improved antiviral activities. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 4790–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Meuser, M.E.; Zalloum, W.A.; Xu, S.; Huang, T.; Cherukupalli, S.; Jiang, X.; Ding, X.; Tao, Y.; et al. Design, synthesis, and mechanism study of dimerized phenylalanine derivatives as novel HIV-1 capsid inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortagere, S.; Welsh, W.J. Development and application of hybrid structure based method for efficient screening of ligands binding to G-protein coupled receptors. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2006, 20, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortagere, S.; Madani, N.; Mankowski, M.K.; Schön, A.; Zentner, I.; Swaminathan, G.; Princiotto, A.; Anthony, K.; Oza, A.; Sierra, L.J.; et al. Inhibiting early-stage events in HIV-1 replication by small-molecule targeting of the HIV-1 capsid. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8472–8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Cantrelle, F.X.; Robert, X.; Boll, E.; Sierra, N.; Gouet, P.; Hanoulle, X.; Alvarez, G.I.; Guillon, C. Identification of a potential inhibitor of the FIV p24 capsid protein and characterization of its binding site. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1896–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Shoichet, B.K. ZINC—A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2005, 45, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curreli, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Pyatkin, I.; Victor, Z.; Altieri, A.; Debnath, A.K. Virtual screening based identification of novel small-molecule inhibitors targeted to the HIV-1 capsid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

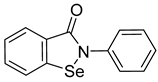

- Thenin-Houssier, S.; de Vera, I.M.; Pedro-Rosa, L.; Brady, A.; Richard, A.; Konnick, B.; Opp, S.; Buffone, C.; Fuhrmann, J.; Kota, S.; et al. Ebselen, a small-molecule capsid inhibitor of HIV-1 replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, T.; Kanayama, M.; Shibata, T.; Itoh, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Uchida, K. Ebselen, a seleno-organic antioxidant, as an electrophile. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampel, A.; Bram, Y.; Ezer, A.; Shaltiel-Kario, R.; Saad, J.S.; Bacharach, E.; Gazit, E. Targeting the early step of building block organization in viral capsid assembly. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.W.; Luo, R.H.; Xu, L.; Yang, L.M.; Xu, X.S.; Bedwell, G.J.; Engelman, A.N.; Zheng, Y.T.; Chang, S. A HTRF based competitive binding assay for screening specific inhibitors of HIV-1 capsid assembly targeting the C-terminal domain of capsid. Antivir. Res. 2019, 169, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujioka, T.; Kashiwada, Y.; Kilkuskie, R.E.; Cosentino, L.M.; Ballas, L.M.; Jiang, J.B.; Janzen, W.P.; Chen, I.S.; Lee, K.H. Anti-AIDS agents, 11. Betulinic acid and platanic acid as anti-HIV principles from Syzigium claviflorum, and the anti-HIV activity of structurally related triterpenoids. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, P.W.; Adamson, C.S.; Heymann, J.B.; Freed, E.O.; Steven, A.C. HIV-1 maturation inhibitor bevirimat stabilizes the immature Gag lattice. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Feasley, C.L.; Jackson, K.W.; Nitz, T.J.; Salzwedel, K.; Air, G.M.; Sakalian, M. The prototype HIV-1 maturation inhibitor, bevirimat, binds to the CA-SP1 cleavage site in immature Gag particles. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Goila-Gaur, R.; Salzwedel, K.; Kilgore, N.R.; Reddick, M.; Matallana, C.; Castillo, A.; Zoumplis, D.; Martin, D.E.; Orenstein, J.M.; et al. PA-457: A potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13555–13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, P.; Larsen, D.; Press, R.; Wehrman, T.; Martin, D.E. The absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of bevirimat in rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2008, 29, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.F.; Ogundele, A.; Forrest, A.; Wilton, J.; Salzwedel, K.; Doto, J.; Allaway, G.P.; Martin, D.E. Phase I and II study of the safety, virologic effect, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of single-dose 3-o-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid (bevirimat) against human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3574–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Baelen, K.; Salzwedel, K.; Rondelez, E.; Van Eygen, V.; De Vos, S.; Verheyen, A.; Steegen, K.; Verlinden, Y.; Allaway, G.P.; Stuyver, L.J. Susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the maturation inhibitor bevirimat is modulated by baseline polymorphisms in Gag spacer peptide 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2185–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margot, N.A.; Gibbs, C.S.; Miller, M.D. Phenotypic susceptibility to bevirimat in isolates from HIV-1-infected patients without prior exposure to bevirimat. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Knapp, D.J.; Harrigan, P.R.; Poon, A.F.; Brumme, Z.L.; Brockman, M.; Cheung, P.K. In vitro selection of clinically relevant bevirimat resistance mutations revealed by “deep” sequencing of serially passaged, quasispecies-containing recombinant HIV-1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Reed, J.C.; Solas, D.; Kitaygorodskyy, A.; Freeman, B.; Ressler, D.T.B.; Phuong, D.J.; Swain, J.V.; Matlack, K.; Hurt, C.R.; Lingappa, V.R.; et al. Identification of an antiretroviral small molecule that appears to be a host-targeting inhibitor of HIV-1 assembly. J. Virol. 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, S.Y.; Mualif, S.A.; Omar, T.C.; Wei, C.Y.; Yusoff, N.M.; Ali, S.A. Production and purification of polymerization-competent HIV-1 capsid protein p24 (CA) in NiCo21(DE3) Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A.; Teow, S.Y.; Omar, T.C.; Khoo, A.S.; Choon, T.S.; Yusoff, N.M. A cell internalizing antibody targeting capsid protein (p24) inhibits the replication of HIV-1 in T cells lines and PBMCs: A proof of concept study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munyendo, W.L.; Lv, H.; Benza-Ingoula, H.; Baraza, L.D.; Zhou, J. Cell penetrating peptides in the delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Biomolecules 2012, 2, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lou, D.; Burkett, J.; Kohler, H. Chemical engineering of cell penetrating antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 2001, 254, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, F.; Kashiwada, Y.; Cosentino, L.M.; Chen, C.H.; Garrett, P.E.; Lee, K.H. Anti-AIDS agents—XXVII. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of betulinic acid and dihydrobetulinic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1997, 5, 2133–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, G.M.; Moianos, D.; Giannakopoulou, E.; Pardali, V.; Tavis, J.E.; Zoidis, G. Recent advances in hepatitis B treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsounis, E.P.; Tourkochristou, E.; Mouzaki, A.; Triantos, C. Toward a new era of hepatitis B virus therapeutics: The pursuit of a functional cure. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2727–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukuda, S.; Watashi, K. Hepatitis B virus biology and life cycle. Antivir. Res. 2020, 182, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.F.; Cheng, N.; Zlotnick, A.; Wingfield, P.T.; Stahl, S.J.; Steven, A.C. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature 1997, 386, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packianathan, C.; Katen, S.P.; Dann, C.E., 3rd; Zlotnick, A. Conformational changes in the hepatitis B virus core protein are consistent with a role for allostery in virus assembly. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, G.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.S.; Yin, C.C. Allosteric conformational changes of human HBV core protein transform its assembly. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijampatnam, B.; Liotta, D.C. Recent advances in the development of HBV capsid assembly modulators. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 50, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dane, D.S.; Cameron, C.H.; Briggs, M. Virus-like particles in serum of patients with Australia-antigen associated hepatitis. Lancet 1970, 295, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, U.; Mani, N.; Hu, Z.; Ban, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Chang, J.; Guo, J.T. Targeting the multifunctional HBV core protein as a potential cure for chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Res. 2020, 182, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, F.; Tong, X.; Hoffmann, D.; Zuo, J.; Lu, M. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection using small molecule modulators of nucleocapsid assembly: Recent advances and perspectives. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassit, L.; Ono, S.K.; Schinazi, R.F. Moving fast toward hepatitis B virus elimination. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1322, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Stray, S.J.; Zlotnick, A. BAY 41-4109 has multiple effects on hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. J. Mol. Recognit. 2006, 19, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deres, K.; Schröder, C.H.; Paessens, A.; Goldmann, S.; Hacker, H.J.; Weber, O.; Krämer, T.; Niewöhner, U.; Pleiss, U.; Stoltefuss, J.; et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug-induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science 2003, 299, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stray, S.J.; Bourne, C.R.; Punna, S.; Lewis, W.G.; Finn, M.G.; Zlotnick, A. A heteroaryldihydropyrimidine activates and can misdirect hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8138–8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, A.G. Modulators of HBV capsid assembly as an approach to treating hepatitis B virus infection. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 30, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, M.R.; Liu, F.; Mao, R.; Mills, C.; Cai, D.; Guo, F.; Zhao, X.; Ye, H.; Cuconati, A.; Guo, H.; et al. Sulfamoylbenzamide derivatives inhibit the assembly of hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6931–6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, M.; Guo, L.; Kocer, B.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Shi, H.; et al. Discovery and pre-clinical characterization of third-generation 4-H heteroaryldihydropyrimidine (HAP) analogues as hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsid inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3352–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; Ma, J.; Hu, Z.; Wu, S.; Hwang, N.; Kulp, J.; Du, Y.; Guo, J.-T.; Chang, J. Discovery of novel hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid assembly inhibitors. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioud, G.; Pichoud, C.; Puerstinger, G.; Neyts, J.; Zoulim, F. The main hepatitis B virus (HBV) mutants resistant to nucleoside analogs are susceptible in vitro to non-nucleoside inhibitors of HBV replication. Antivir. Res. 2011, 92, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wu, D.; Hu, H.; Zeng, J.; Yu, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, X.; Yang, G.; Young, J.A.T.; et al. Direct inhibition of hepatitis B e antigen by core protein allosteric modulator. Hepatology 2019, 70, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, J.J.; Colledge, D.; Sozzi, V.; Edwards, R.; Littlejohn, M.; Locarnini, S.A. The phenylpropenamide derivative AT-130 blocks HBV replication at the level of viral RNA packaging. Antivir. Res. 2007, 76, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Hu, T.; Zhou, X.; Wildum, S.; Garcia-Alcalde, F.; Xu, B.; Wu, D.; Mao, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Heteroaryldihydropyrimidine (HAP) and sulfamoylbenzamide (SBA) inhibit hepatitis B virus replication by different molecular mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, K.; Shimada, T.; Allweiss, L.; Volz, T.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Hartman, G.; Flores, O.A.; Lam, A.M.; Dandri, M. Efficacy of NVR 3-778, alone and in combination with pegylated interferon, vs. Entecavir in uPA/SCID mice with humanized livers and HBV infection. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 652–662.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktoudianakis, E.R.C.; Canales, E.; Currie, K.S.; Kato, D.; Li, J.; Link, J.O.; Metobo, S.E.; Saito, R.D.; Schroeder, S.D.; Shapiro, N.; et al. Compounds for the Treatment of Hepatitis B Virus Infections. U.S. Patent Application No. 20180251460, 2 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gane, E.; Liu, A.; Yuen, M.F.; Schwabe, C.; Bo, Q.; Das, S.; Gao, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Coakley, E.; et al. LBO-003-RO7049389, a core protein allosteric modulator, demonstrates robust anti-HBV activity in chronic hepatitis B patients and is safe and well tolerated. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Gane, E.; Schwabe, C.; Zhu, M.; Triyatni, M.; Zhou, J.; Bo, Q.; Jin, Y. A five-in-one first-in-human study to assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of RO7049389, an inhibitor of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly, after single and multiple ascending doses in healthy participants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, H.G.; Imran, A.; Kim, K.; Han, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, M.-J.; Yun, C.-S.; Jung, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Han, S.B. Discovery of a new sulfonamide hepatitis B capsid assembly modulator. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Cha, H.-M.; Hwang, J.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Vishakantegowda, A.G.; Imran, A.; Lee, J.-Y.; Yi, Y.-S.; Jun, S.; Kim, G.H.; et al. Sulfamoylbenzamide-based capsid assembly modulators for selective inhibition of hepatitis B viral replication. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, O.; Boucle, S.; Cox, B.D.; Ozturk, T.; Russell, O.O.; Bassit, L.; Amblard, F.; Schinazi, R.F. Synthesis of sulfamoylbenzamide derivatives as HBV capsid assembly effector. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, S.J.; McBrearty, N.; Arzumanyan, A.; Bichenkov, E.; Tao, S.; Bassit, L.; Chen, Z.; Kohler, J.J.; Amblard, F.; Feitelson, M.A.; et al. Studies on the efficacy, potential cardiotoxicity and monkey pharmacokinetics of GLP-26 as a potent hepatitis B virus capsid assembly modulator. Viruses 2021, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblard, F.; Boucle, S.; Bassit, L.; Cox, B.; Sari, O.; Tao, S.; Chen, Z.; Ozturk, T.; Verma, K.; Russell, O.; et al. Novel hepatitis B virus capsid assembly modulator induces potent antiviral responses in vitro and in humanized mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01701-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Ding, Y.; Wu, L.; Liang, L.; He, X.; Li, Q.; Bai, C.; Zhang, H. Design and synthesis of aminothiazole based hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsid inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Wu, S.; Li, W.; Geng, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q.; Liu, M. Design, synthesis and anti-HBV activity of NVR3-778 derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.T.; Liu, R.R.; Zhai, H.L.; Meng, Y.J.; Zhu, M. Molecular mechanisms of tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-c]pyrimidines as HBV capsid assembly inhibitors. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 663, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandyck, K.; Rombouts, G.; Stoops, B.; Tahri, A.; Vos, A.; Verschueren, W.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Hou, F.; Huang, B.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of N-phenyl-3-sulfamoyl-benzamide derivatives as capsid assembly modulators inhibiting hepatitis B virus (HBV). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 6247–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Li, J.J.; Shan, Z.J.; Zhai, H.L. Exploring the binding mechanism of heteroaryldihydropyrimidines and hepatitis B virus capsid combined 3D-QSAR and molecular dynamics. Antivir. Res. 2017, 137, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, N.; Ban, H.; Chen, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, H.; Lam, P.; Kulp, J.; Menne, S.; Chang, J.; Guo, J.T.; et al. Synthesis of 4-oxotetrahydropyrimidine-1(2H)-carboxamides derivatives as capsid assembly modulators of hepatitis B virus. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Yu, J.; Du, X.; Cherukupalli, S.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Design, diversity-oriented synthesis and biological evaluation of novel heterocycle derivatives as non-nucleoside HBV capsid protein inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 202, 112495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Shi, L.; Chen, H.; Tong, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, C.; He, P.; Zhu, F.; et al. Isothiafludine, a novel non-nucleoside compound, inhibits hepatitis B virus replication through blocking pregenomic RNA encapsidation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jia, H.; Bai, F.; Liu, N.; Liang, X.; Zhan, P.; Ma, C.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X. Design, synthesis and evaluation of pyrazole derivatives as non-nucleoside hepatitis B virus inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 123, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama, M.; Sakakibara, N.; Takeda, M.; Okamoto, M.; Watashi, K.; Wakita, T.; Sugiyama, M.; Mizokami, M.; Ikeda, M.; Baba, M. Pyrimidotriazine derivatives as selective inhibitors of HBV capsid assembly. Virus Res. 2019, 271, 197677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuduk, S.D.; Stoops, B.; Alexander, R.; Lam, A.M.; Espiritu, C.; Vogel, R.; Lau, V.; Klumpp, K.; Flores, O.A.; Hartman, G.D. Identification of a new class of HBV capsid assembly modulator. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 39, 127848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, R.; Sheng, R.; Hou, T. Discovery of novel HBV capsid assembly modulators by structure-based virtual screening and bioassays. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 116096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, M.; Matsuda, N.; Matoba, K.; Kondo, S.; Kanegae, Y.; Saito, I.; Nomoto, A. Acetophenone 4-nitrophenylhydrazone inhibits Hepatitis B virus replication by modulating capsid assembly. Virus Res. 2021, 306, 198565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, K.; Lam, A.M.; Lukacs, C.; Vogel, R.; Ren, S.; Espiritu, C.; Baydo, R.; Atkins, K.; Abendroth, J.; Liao, G.; et al. High-resolution crystal structure of a hepatitis B virus replication inhibitor bound to the viral core protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney William, E.; Edwards, R.; Colledge, D.; Shaw, T.; Furman, P.; Painter, G.; Locarnini, S. Phenylpropenamide derivatives AT-61 and AT-130 inhibit replication of wild-type and Lamivudine-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3057–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Ko, C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, M. Current progress in the development of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly modulators: Chemical structure, mode-of-action and efficacy. Molecules 2021, 26, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, V. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 369, 167–198. [Google Scholar]

- Morozov, V.A.; Lagaye, S. Hepatitis C virus: Morphogenesis, infection and therapy. World J. Hepatol. 2018, 10, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.E.; Balistreri, W.F. Cascade of care for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manns, M.P.; McHutchison, J.G.; Gordon, S.C.; Rustgi, V.K.; Shiffman, M.; Reindollar, R.; Goodman, Z.D.; Koury, K.; Ling, M.; Albrecht, J.K. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A randomised trial. Lancet 2001, 358, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Li, L.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, S. Direct-acting antiviral in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: Bonuses and challenges. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawitz, E.; Jacobson, I.M.; Nelson, D.R.; Zeuzem, S.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Esteban, R.; Brainard, D.; McNally, J.; Symonds, W.T.; McHutchison, J.G.; et al. Development of sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1358, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, Y.; Luo, H.; Qin, W.; Kaneko, S.; Yamashita, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Murakami, S. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A binds RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) NS5B and modulates RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11149–11155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.M.; Jacobson, I.M.; Rice, C.M.; Zeuzem, S. Emerging therapies for the treatment of hepatitis C. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Hanson, A.M.; Shadrick, W.R.; Ndjomou, J.; Sweeney, N.L.; Hernandez, J.J.; Bartczak, D.; Li, K.; Frankowski, K.J.; Heck, J.A.; et al. Identification and analysis of hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase inhibitors using nucleic acid binding assays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 8607–8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Krajewski, M.; Scherer, C.; Scholz, V.; Mordhorst, V.; Truschow, P.; Schöbel, A.; Reimer, R.; Schwudke, D.; Herker, E. Complex lipid metabolic remodeling is required for efficient hepatitis C virus replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Li, J.; Cai, H.; Yao, W.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y.-P.; Qiu, X.; Xia, H.; Peng, T. Avasimibe: A novel hepatitis C virus inhibitor that targets the assembly of infectious viral particles. Antivir. Res. 2017, 148, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- André, P.; Perlemuter, G.; Budkowska, A.; Bréchot, C.; Lotteau, V. Hepatitis C virus particles and lipoprotein metabolism. Semin. Liver Dis. 2005, 25, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, M.A.; Abdel-Hakeem, M.S.; Mason, A.L.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Houghton, M. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibitors prevent hepatitis C virus release/assembly through perturbation of lipid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatoorian, R.; Riahi, R.; Ganapathy, E.; Shao, H.; Wheatley, N.M.; Sundberg, C.; Jung, C.L.; Ruchala, P.; Dasgupta, A.; Arumugaswami, V.; et al. Allosteric heat shock protein 70 inhibitors block hepatitis C virus assembly. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 47, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, R.; Qu, X.; Petit, M.A.; Beretta, L. The heat shock cognate protein 70 is associated with hepatitis C virus particles and modulates virus infectivity. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J. Mechanism and complex roles of HSC70 in viral infections. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanwell, N.A.; Belema, M. The discovery and development of daclatasvir: An inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS5A replication complex. HCV J. Discov. Cure 2018, 32, 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Boson, B.; Denolly, S.; Turlure, F.; Chamot, C.; Dreux, M.; Cosset, F.L. Daclatasvir prevents hepatitis C virus infectivity by blocking transfer of the viral genome to assembly sites. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 895–907.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Hu, X.; He, S.; Yim, H.J.; Xiao, J.; Swaroop, M.; Tanega, C.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Yi, G.; Kao, C.C.; et al. Identification of novel anti-hepatitis C virus agents by a quantitative high throughput screen in a cell-based infection assay. Antivir. Res. 2015, 124, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.B.; Boyer, A.; Hu, Z.; Le, D.; Liang, T.J. Discovery and characterization of a novel HCV inhibitor targeting the late stage of HCV life cycle. Antivir. Ther. 2019, 24, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, G.; Barouch-Bentov, R.; Ziv-Av, A.; Gerber, D.; Jacob, Y.; Einav, S. Identification and targeting of an interaction between a tyrosine motif within hepatitis C virus core protein and AP2M1 essential for viral assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.D.; Imamura, M.; Talley, D.C.; Rolt, A.; Xu, X.; Wang, A.Q.; Le, D.; Uchida, T.; Osawa, M.; Teraoka, Y.; et al. Fluoxazolevir inhibits hepatitis C virus infection in humanized chimeric mice by blocking viral membrane fusion. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Lin, B.; Chu, V.; Hu, Z.; Hu, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, A.Q.; Schweitzer, C.J.; Li, Q.; Imamura, M.; et al. Repurposing of the antihistamine chlorcyclizine and related compounds for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 282ra49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolt, A.; Le, D.; Hu, Z.; Wang, A.Q.; Shah, P.; Singleton, M.; Hughes, E.; Dulcey, A.E.; He, S.; Imamura, M.; et al. Preclinical pharmacological development of chlorcyclizine derivatives for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolt, A.; Talley, D.C.; Park, S.B.; Hu, Z.; Dulcey, A.; Ma, C.; Irvin, P.; Leek, M.; Wang, A.Q.; Stachulski, A.V.; et al. Discovery and optimization of a 4-aminopiperidine scaffold for inhibition of hepatitis C virus assembly. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 9431–9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, S.; Coito, C.; Mousseau, G.; Lavergne, J.P.; Strosberg, A.D. Peptide inhibitors of hepatitis C virus core oligomerization and virus production. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90 Pt 6, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kota, S.; Scampavia, L.; Spicer, T.; Beeler, A.B.; Takahashi, V.; Snyder, J.K.; Porco, J.A.; Hodder, P.; Strosberg, A.D. A time-resolved fluorescence–resonance energy transfer assay for identifying inhibitors of hepatitis C virus core dimerization. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2009, 8, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, F.; Kota, S.; Takahashi, V.; Strosberg, A.D.; Snyder, J.K. Potent inhibitors of hepatitis C core dimerization as new leads for anti-hepatitis C agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 2198–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, S.; Takahashi, V.; Ni, F.; Snyder, J.K.; Strosberg, A.D. Direct binding of a hepatitis C virus inhibitor to the viral capsid protein. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O.; et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwee, S.X.W.; St John, A.L.; Gray, G.C.; Pang, J. Animals as potential reservoirs for dengue transmission: A systematic review. One Health 2021, 12, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.S.; Zhou, Y.; Takagi, T.; Kameoka, M.; Kawashita, N. Dengue virus and its inhibitors: A brief review. Chem. Pharm. Bull 2018, 66, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, C.M.; Dai, D.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Berhanu, A.; Jones, K.F.; Cardwell, K.B.; Schneider, C.; Wineinger, K.A.; Page, J.M.; Harver, C.; et al. A novel inhibitor of dengue virus replication that targets the capsid protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaturro, P.; Trist, I.M.L.; Paul, D.; Kumar, A.; Acosta, E.G.; Byrd, C.M.; Jordan, R.; Brancale, A.; Bartenschlager, R.; Diamond, M.S. Characterization of the mode of action of a potent dengue virus capsid inhibitor. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11540–11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, D.; Smith, J.L.; Hirsch, A.J.; Bhinder, B.; Radu, C.; Stein, D.A.; Nelson, J.A.; Früh, K.; Djaballah, H. High-content assay to identify inhibitors of dengue virus infection. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2010, 8, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Sheridan, K.; Parkins, C.J.; Frueh, L.; Jemison, A.L.; Strode, K.; Dow, G.; Nilsen, A.; Hirsch, A.J. Characterization and structure-activity relationship analysis of a class of antiviral compounds that directly bind dengue virus capsid protein and are incorporated into virions. Antivir. Res. 2018, 155, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousseau, G.; Kota, S.; Takahashi, V.; Frick, D.N.; Strosberg, A.D. Dimerization-driven interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with NS3 helicase. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, B.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Das, A.; Prashar, V.; Gupta, G.D.; Panicker, L.; Kumar, M. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahtarin, R.; Islam, S.; Islam, M.J.; Ullah, M.O.; Ali, M.A.; Halim, M.A. Structure and dynamics of membrane protein in SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Du, N.; Lei, Y.; Dorje, S.; Qi, J.; Luo, T.; Gao, G.F.; Song, H. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinzula, L.; Basquin, J.; Bohn, S.; Beck, F.; Klumpe, S.; Pfeifer, G.; Nagy, I.; Bracher, A.; Hartl, F.U.; Baumeister, W. High-resolution structure and biophysical characterization of the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein dimerization domain from the Covid-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 538, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, S.M.; Lambertz, R.; Fürtig, B.; Hengesbach, M.; Löhr, F.; Richter, C.; Schwalbe, H.; Weigand, J.E.; Wöhnert, J.; Schlundt, A. (1)H, (13)C, and (15)N backbone chemical shift assignments of the C-terminal dimerization domain of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Biomol. NMR Assign 2021, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, V.S.; McKay, M.J.; Shcherbakov, A.A.; Dregni, A.J.; Kolocouris, A.; Hong, M. Structure and drug binding of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein transmembrane domain in lipid bilayers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Nandi, R.; Jagadeesan, R.; Kumar, N.; Prakash, A.; Kumar, D. Identification of potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 by targeting proteins responsible for envelope formation and virion assembly using docking based virtual screening, and pharmacokinetics approaches. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 84, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamad, S.; Gupta, D.; Kumar, V. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid oligomerization: Insights from molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patocka, J.; Kuca, K.; Oleksak, P.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Novotny, M.; Klimova, B. Rapamycin: Drug repurposing in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Byrareddy, S.N. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 331, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peele, K.A.; Kumar, V.; Parate, S.; Srirama, K.; Lee, K.W.; Venkateswarulu, T.C. Insilico drug repurposing using FDA approved drugs against Membrane protein of SARS-CoV-2. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 2346–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, F.; Zheng, H.; Yu, R. The study of antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike proteins through large-scale compound repurposing. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, H.S.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Lai, H.M.; He, X.; Khan, K.S.; Kaur, S.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Chan, A.K.N.; Cheung, H.H.Y.; et al. Simeprevir potently suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication and synergizes with remdesivir. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammeltoft, K.A.; Zhou, Y.; Hernandez, C.R.D.; Galli, A.; Offersgaard, A.; Costa, R.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Feng, S.; Scheel, T.K.H.; et al. Hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors show differential efficacy and interactions with remdesivir for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02680-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Xu, M.; Chen, C.Z.; Guo, H.; Shen, M.; Hu, X.; Shinn, P.; Klumpp-Thomas, C.; Michael, S.G.; Zheng, W. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors by a quantitative high-throughput screening. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnick, J.L. Portraits of viruses: The picornaviruses. Intervirology 1983, 20, 61–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anasir, M.I.; Zarif, F.; Poh, C.L. Antivirals blocking entry of enteroviruses and therapeutic potential. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichhardt, H.; Otto, M.J.; McKinlay, M.A.; Willingmann, P.; Habermehl, K.O. Inhibition of poliovirus uncoating by disoxaril (WIN 51711). Virology 1987, 160, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]